1.12. Street Crime, Corporate Crime, and White-Collar Crime

Shanell Sanchez

As previously demonstrated, crime can be broadly defined, but the two most common types of crime discussed are, street crime and corporate or white-collar crime. Most people are familiar with street crime since it is the most commonly discussed amongst politicians, media outlets, and members of society. Every year the Justice Department puts out an annual report titled “Crime in the United States” which means street crime but has yet to publish an annual Corporate Crime in the United States report. Most Americans will find little to nothing on price-fixing, corporate fraud, pollution, or public corruption.

Street Crime

Street crime is often broken up into different types and can include acts that occur in both public and private spaces, as well as interpersonal violence and property crime. According to the Bureau of Justice (BJS), street crime can include violent crimes such as homicide, rape, assault, robbery, and arson. Street crime also includes property crimes such as larceny, arson, breaking-and-entering, burglary, and motor vehicle theft. The BJS also collects data on drug crime, hate crimes, and human trafficking, which often fall under the larger umbrella of street crime. [1]

Fear of street crime is real in American society; however, street crime may not be as rampant as many think. In a 2017 report, the BJS found that the rate of robbery victimization increased from 1.7 per 1,000 persons in 2016 to 2.3 in 2017. Overall, robbery happens to a small percentage of Americans, which also seems to be a similar trend when looking at the portion of persons age 12 or older who were victims of violent crime. The BJS noted an increase from 0.98% in 2015 to 1.14% in 2017, but note the small percentage overall. Further from 2015 to 2017, the percentage of persons who were victims of violent crime increased among males, whites, those ages 25 to 34, those aged 50 and over, and those who had never married. There are clear risk factors that can be taken into account when attempting to develop policy, which is discussed in subsequent chapters of the book. There were also areas where the BJS noted a downward trend in crime, such as the decline in the rate of overall property crime from 118.6 victimizations per 1,000 households to 108.4, while the burglary rate fell from 23.7 to 20.6. [2]

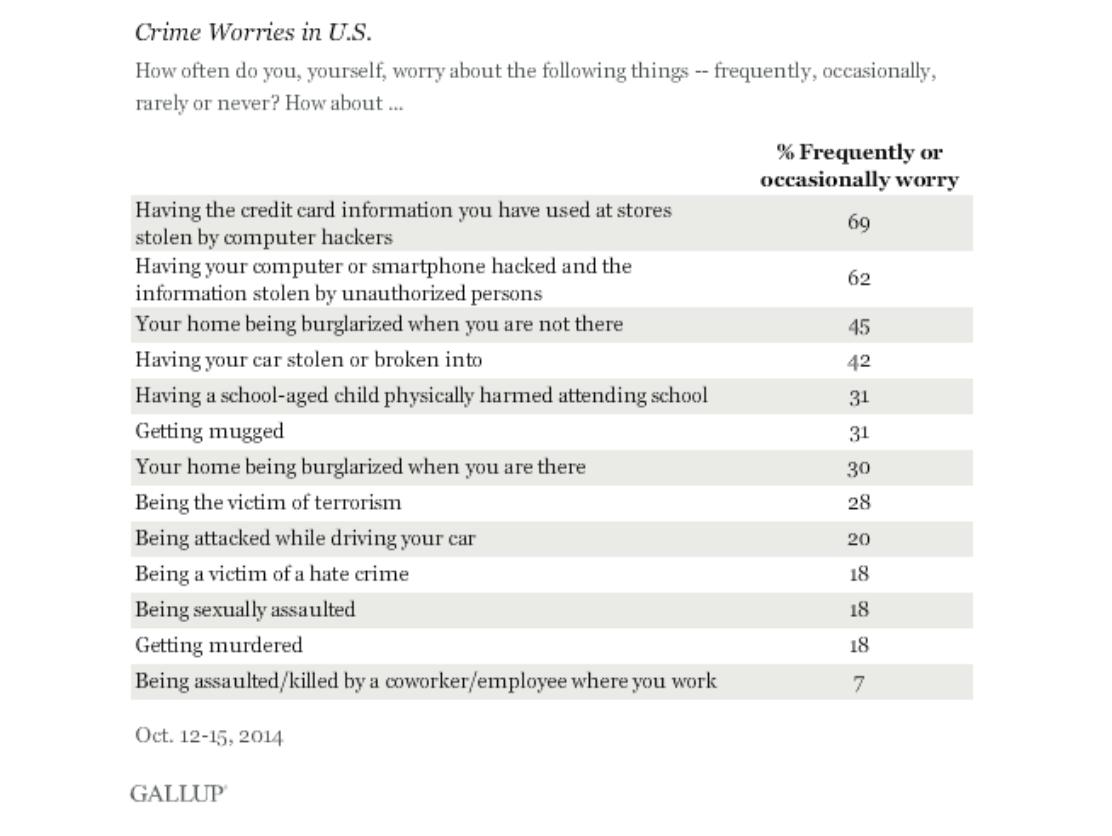

Polls have consistently found that people are worried about crime in the United States, specifically street crime. Riffkin (2014) found that people worry about various crimes such as homes getting burglarized when they were home, the victim of terrorism, being attacked while driving their car, murdered, the victim of a hate crime, and being sexually assaulted https://news.gallup.com/poll/178856/hacking-tops-list-crimes-americans-worry.aspx . Most people in society, people can go about their daily lives without the fear of being a victim of street crime. Street crime is important to take seriously, but it is reassuring to note that it is unlikely to happen to most people. The conversation should happen around why fears are high, especially amongst those less likely to be a victim. For example, elderly citizens have the greatest fear of street crime, yet they are the group least likely to experience it. Whereas younger people, especially young men, are less likely to fear crime and are the most likely to experience it. [3]

Because Americans are often fearful of street crime, for various reasons, resources are devoted to prevention and protecting the public. The United States spends roughly $265.2 billion dollars a year and employs more than one million police officers, almost 750,000 correctional officers, and more than 490,000 judicial and legal personnel on street crime. [4] The Uniform Crime Reports (UCR) estimated in 2015 that financial losses from property crime at $14.3 billion in 2014 (FBI, 2015a), but keep that number in mind for a minute. [5] Although it is crucial to recognize that street crime does occur, and it impacts certain groups disproportionately more than others, it is also important to recognize other types of crimes commonly talked discussed. In fact, the BJS does not have a link that directs people to the next two types of crime discussed when on their main page of crime types.

Corporate Crime

When most people think of crime, they think of acts of interpersonal violence or property crime. The typical image of a criminal is not someone who is considered a ‘pillar’ in society, especially one who may have an excellent career, donate to charity, devote time to the community, and engage in ‘normal’ behavior. [6] Corporate crime is an offense committed by a corporation’s officers who pursue illegal activity (various kinds) in the name of the corporation. The goal is to make money for the business and run a profitable business, and the representatives of the business. Corporate crime may also include environmental crime if a corporation damages the environment to earn a profit. [7] As C. Wright Mills (1952) once stated, “corporate crime creates higher immorality” in U.S. society. [8] Corporate crime inflicts far more damage on society than all street crime combined, by death, injury, or dollars lost.

Credit Suisse pled guilty to helping thousands of Americans file false income tax returns, and the company got fined $2.6 billion. Last year, BNP Paribas pled guilty to violating trade sanctions and was forced to pay $8.9 billion, which exceeds the yearly pocket yearly costs of all the burglaries and robberies in the United States ($4.5 billion in 2014 according to the FBI). Another example is health care fraud. The estimates suggest this costs Americans $100 billion to $400 billion a year. [9]

In 2001, the energy company Enron committed accounting and corporate fraud, where shareholders lost $74 billion in the four years leading to its bankruptcy, thousands of employees lost jobs, and billions of dollars got lost in pension plans. [10]

In addition to financial loss, corporate crime can be violent. In 2016, the FBI estimated the number of murders in the nation to be 17,250. [11] Compare 54,000 Americans who die every year on the job or from occupational diseases such as black lung and asbestosis and the additional tens of thousands of other Americans who fall victim every year to the silent violence of pollution, contaminated foods, hazardous consumer products, and hospital malpractice. [12] A vast majority of these deaths are often the result of criminal recklessness. Americans are rarely made aware of them, and they rarely make their way through the criminal justice system.

The last major homicide prosecution brought against a major American corporation was in 1980. A Republican Indiana prosecutor charged Ford Motor Co. with homicide for the deaths of three teenage girls who died when their Ford Pinto caught on fire after being rear-ended in northern Indiana. The prosecutor alleged that Ford knew that it was marketing a defective product, with a gas tank that crushed when rear-ended, spilling fuel, where the girls incinerated to death. Ford hired a criminal defense lawyer who in turn hired the best friend of the judge as local counsel, and who, as a result, secured a not guilty verdict after persuading the judge to keep key evidence out of the jury room. [13] https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/fatal-ford-pinto-crash-in-indiana .

Sometimes the terms corporate and white-collar crime are used interchangeably, but there are important distinctions between the two terms. [14]

White-Collar Crime

In contrast to corporate crime, white-collar crime usually involves employees harming the individual corporation. Sometimes corporate and white-collar crime goes hand in hand, but not always. An example of white-collar crime would be the financial offenses of Bernard Madoff, who defrauded his investors of approximately $20 billion. Instead of trading stocks with his client’s money, Madoff had for years been operating an enormous Ponzi scheme, paying off old investors with money he got from new ones.

By late 2008, with the economy in free fall, Madoff could no longer attract new money, and the scheme collapsed, which resulted in hundreds of investors, including numerous charities, being wiped out. As of today, a court-appointed trustee has managed to recover about $13 billion, which is most of the money Madoff’s investors put into his funds. The trustee sold off Madoff family’s assets, including their homes in the Hamptons, Manhattan, and France and a 55-foot yacht named Bull. [15]

Dr. Sanchez’s Professor in Graduate School

In 2008, many people were negatively impacted by Madoff, one of which was a former professor for Dr. Sanchez. He lost his retirement, which required him to keep teaching well into his 80s, as well as lost his home. The impact of Madoff was far-reaching and although most may call it a purely economic crime, people committed suicide and lost everything in this scandal.

No official program measures corporate and white-collar crime like there is with street crime occurring in the United States. Therefore, we estimate costs to society, and who the victims are. Additionally, unlike street crime where the crime can often be discovered instantly and investigated quickly, corporate and white-collar crime can take years to investigate and even longer to prosecute. Remember, Madoff was involved in fraud most of his working life but was not caught until he was nearing the end at the age of 71. [16]

- https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=316 ↵

- Morgan, R., & Truman, J., (December 2018). NCJ 252472 ↵

- Doerner, W. G., & Lab, S.P. (2008). Victimology (5th ed.). Cincinnati, Ohio: Lexis-Nexis. ↵

- Kyckelhahn, T. (2012). Justice expenditure and employment extracts. Bureau of Justice Statistics ↵

- FBI. (2015b), September 28). The latest crime stats were released. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice. ↵

- Fuller, J.R. (2019). Introduction to criminal justice. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press. ↵

- Horowitz, I. (Ed.) (2008), Power, politics, and people. Wright Mills, C. (1952). A diagnosis of moral uneasiness (pp.330-339). New York: Ballantine. ↵

- (2000). License To Steal: How Fraud Bleeds America's Health Care System. Westview Press. ↵

- Folger, J. (November 2011). The Enron collapse: A look back. Investopedia. Retrieved from https://www.investopedia.com/updates/enron-scandal-summary/ ↵

- FBI: UCR. 2016. FBI Murder. https://ucr.fbi.gov/crime-in-the-u.s/2016/crime-in-the-u.s.-2016/topic-pages/murder ↵

- Mokhiber, R. Corporate crime & violence: Big business power and the abuse of the public trust. Random House, Inc. ↵

- Steinzor, R. (Dec. 2014). It’s called 'Why Not Jail?': Industrial catastrophes, corporate malfeasance, and government inaction. Cambridge University Press. ↵

- Kleck, G. (1982). On the use of self-report data to determine the class distribution of criminal and delinquent behavior." American Sociological Review, 427-433. ↵

- Zarroli, J. (2018). For Madoff victims, scars remain 10 years later, National Public Radio, https://www.npr.org/2018/12/23/678238031/for-madoff-victims-scars-remain-10-years-later ↵

- Fuller, J.R. (2019). Introduction to Criminal Justice. New York: Oxford, Oxford University Press. ↵

1.12. Street Crime, Corporate Crime, and White-Collar Crime Copyright © 2019 by Shanell Sanchez is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Street Gangs, Organized Crime Groups, and Terrorists: Differentiating Criminal Organizations

2013, www.InvestigativeSciencesJournal.org

Individually street gangs, organized crime (OC) groups, and terrorists all present serious problems for national and international law enforcement agencies. Imagine though if these three were connected or linked in substantive ways. Whether we want to accept this or not, the lines between these structures are often blurred and ill-defined. Each of these groups often takes on the characteristics of the other group, if not in motive then in technique. Additionally, these groups sometimes form alliances with one another further complicating law enforcement efforts to combat their criminal activity. Distinguishing these groups from one another, as well as outlining areas in which they overlap will help direct law enforcement toward a more successful pursuit of these groups.

Related Papers

Small Wars Journal

Carter F Smith

Military-trained gang members (MTGMs) have received military training such as tactics, weapons, explosives, or equipment, and the use of distinctive military skills. Gangs with military-trained members often pose an ongoing and persistent military and political threat. At least one-tenth of one percent of the U.S. population is an MTGM, and there are between 150,000 and 500,000 MTGMs. That number demonstrates an alarming domestic and national security threat that includes a number of potentially significant implications for government leaders in the U.S., and in other countries where third generation (3GEN) Gangs or Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) are prevalent. The intersection of MTGMs and criminal insurgencies threatens national security and communities, undermining the economic and political foundations of local and state government. These criminal organizations often behave like insurgents, engaging in governance to support the illicit marketplace or acting in police or social roles in the community. Counterinsurgency strategies, including cultural awareness should be implemented alongside traditional anti-gang measures.

MTGMs, whether from Street Gangs, Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs (OMGs), or Domestic Terrorist Extremist (DTE) groups, have endangered U.S. communities since before the birth of the country. Early gang leaders acquired military training before and during the Revolutionary War, and continued their criminal activity as the population transitioned westward. The earliest MTGMs included river pirates, stealing cargo and attacking passengers along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, and later the street gangsters who controlled much of the criminal street business in New York, New York and some of the police and politicians of that time. Members of one DTE group started as a New York street gang, received military training and experience in Mexico during the Mexican-American War, and were released from active duty in the newly-named city of San Francisco, just before the Gold Rush of 1848. The issues of MTGMs today tend to mirror those in history, indicating that a solution to the problem is elusive, perhaps even unattainable.Survey results regarding the perception of MTGM presence in the Western United States are included, as are the results of the most recent Gang and Domestic Extremist Activity Threat Assessment (GDEATA) by the U.S. Army and the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) National Gang Intelligence Center (NGIC). The connection of street gangs, OMGs, and DTEs to the military was examined, as were possible remedies for limiting the dangerousness of those criminals in the community. The note is intended to promote the awareness of the MTGM situation and encourage scholars and practitioners to conduct research concerning this issue in other locations in the United States and foreign nations towards identifying strategies to control the problem or mitigate the effects. The confluence of gangs and the military presents significant social and security challenges with significant national and global security potentials.

This research note reviews the state of military-trained gang members (MTGMs) in the Eastern United States. In each wartime era since the Revolutionary War, there have been MTGMs who engaged in criminal activities in civilian communities. The earliest MTGMs in the United States received their training in the colonial militia. One group started as a New York City street gang, received military training and experience in Mexico during the Mexican-American War, and were released from active duty in San Francisco, just before the Gold Rush of 1848. An individual MTGM started as a well-known crime boss in New York and joined the military to fight in World War I. Contemporary MTGMs challenge military discipline and threaten community security.

In an early exploration of the evolution of group violence in its most common form, John Sullivan found the beginning indicators of Third Generation (3GEN) Gangs, which pose a significant threat to the safety, security, and future of our communities. 3GEN gangs are highly sophisticated, with goals of political power or financial acquisition. First generation gangs are those considered primarily turf gangs. Some turf gangs evolve into drug gangs or entrepreneurial organizations with a market-orientation, thus filling the second generation. Gangs in the third generation include those with a mix of political and mercenary elements who operate or are at least capable of operating in the global community. Military-trained gang members (MTGMs) have been identified in every wartime period for the United States, and active duty MTGMs threaten the cohesiveness of military units and undermine the authority of military leadership, using the military to further their criminal organization’s goals. They are a clear threat to military discipline, bringing corrupt influences, an increase in criminal activity, and a threat to military family members on military installations.

Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice

Matthew Valasik

Purpose - The purpose of this paper is to use nearly a century’s worth of gang research to inform us about modern terrorist groups, specifically the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Design/methodology/approach - A case study approach is employed, comparing and contrasting the competing theoretical frameworks of gangs and terrorist organisations to understand group structure, demographics, patterns of behaviour (e.g., territoriality, strategic and instrumental violence), goals, and membership patterns of ISIS. Findings - The qualitative differences of ISIS make them more comparable to street gangs than other terrorist groups. Practical implications - ISIS while being qualitatively different from other terrorist groups actually has many similarities with street gangs allowing for the adaptation of effective gang prevention, intervention, and suppression strategies. This paper highlights how the expansive literature on street gangs is able to inform practical interventions to directly target ISIS and deradicalise potential recruits. By introducing a gang-terror nexus on the crime-terror continuum this paper provides a useful perspective on the decentralised but dynamic nature of modern era insurgencies. This paper urges similar case studies of terrorist organizations to determine the extent to which they conform to street gang characteristics. Originality/value - Terrorist groups are often compared to street gangs, yet it has not been until the last few years that gang researchers (Curry, 2011; Decker and Pyrooz, 2011; 2015) have begun to compare and contrast these two deviant group archetypes. The goal of this paper is to use nearly a hundred years of gang research to better equip scholars and practitioners with a broader understanding of terrorism and insurgency in the era of globalisation by presenting a case study of ISIS using a street gang perspective.

Joshua Harms , Carter F Smith

Communities everywhere have experienced the negative effects of street gangs, domestic terrorists, and outlaw motorcycle gangs. The presence of these criminals increases the threat of violence to the community. When they have military training, the threat increases significantly. The problem addressed in this study was the growing presence of military-trained gang members in civilian communities. The purpose of the study was to determine the perceived presence of military-trained gang members in jails and community corrections and to examine whether there was a relationship between the perceptions of sheriff’s deputies regarding that presence and a number of variables.

Travis Linnemann

This paper engages the cultural politics of criminal classifications by aiming at one of the state’s most powerful, yet ambiguous markers—the ‘gang.’ Focusing on the unique cases of ‘crews’ and collectives within the ‘straight edge’ and ‘Juggalo’ subcultures, this paper considers what leads members of the media and police to construct—or fail to construct—these street collectives as gangs in a seemingly haphazard and disparate fashion. Juxtaposing media, cultural, and police representations of straight edge ‘crews’ and Juggalo collectives with the FBI’s Gang Threat Assessment, we detail how cultural politics and ideology underpin the social reality of gangs and thus the application of the police power. This paper, furthermore, considers critical conceptualizations of the relationship between police and criminal gangs.

Krista Ochs

John P. Sullivan

This paper discusses the dynamics of the gang-crime-terrorism continuum and its relationship to ”generations of warfare” within the contemporary spectrum of conflict. The focus is to explore the potential for gang-terrorist interaction in the current and emerging conflict environment. The concepts of third generation street gangs (3G2), netwar, and fourth generation warfare (4GW) are applied to investigate the typologies and relationships of third generation street gangs and terrorist groups.

John P. Sullivan , Robert J. Bunker

Drug Trafficking Organizations (DTOs) – commonly called drug cartels – are challenging states and their institutions in increasingly brutal and profound ways. This is seen dramatically in Mexico's drug wars and the expanding reach of Mexican organized criminal enterprises throughout Latin America and other parts of the world. This essay updates a 1998 paper ‘Cartel Evolution: Potentials and Consequences’ and examines current cartel and gang interactions. The paper links discussion of cartel phases to gang generations; updates and applies the discussion of third phase cartel potentials to Mexico; and assesses four alternative futures for Mexico, as well as their cross-border implications for the United States.

RELATED PAPERS

Mabel González Bustelo

Global Crime

Journal of Gang Research, 20(2), pp.41-52

Yalí Noriega

Networks and Netwars The Future of Terror, Crime, and …

Small Wars and Insurgencies

John P. Sullivan , Robert J Bunker

Journal of Gang Research

Air & Space Power Journal

Crime Law and Social Change

Michael Stohl

francesca zampagni , Nils Duquet , Francesco Strazzari

Convergence: Illicit Networks and National Security in the Age of Globalization

Richard Davies

Nils Duquet

Amanzy Amanzy

Carter F Smith , Tae Choo

Robert J Bunker

Rachael M. Rudolph

Vincenzo Ruggiero

Michael Burgoyne

Behsat Ekici, Ph.D. , Ayhan Akbulut , Phil Williams

Amir Rostami , Hernan Mondani

Low Intensity Conflict & Law Enforcement

Journal of Money Laundering Control

Frank S . Perri JD, CPA, CFE

Contemporary Security Policy, 36 (2)

Moritz Schuberth

Studies in Conflict & Terrorism

Nathan P . Jones

Robert Ledger

guevara castillo

Garabet K Moumdjian, Ph.D.

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

What Is Crime?

Cite this chapter.

- Michael J. Lynch ,

- Paul B. Stretesky &

- Michael A. Long

1084 Accesses

M ost criminologists would probably argue that the definition of crime is defined by the state and is not something that they can do much, if anything, to change or influence. Crime is, in this view, what the law states. Using this legal definition, criminologists simply study the causes of crime to determine why some individuals violate the law— perhaps suggesting how various state agencies may do a better job reducing crime and apprehending offenders. We assert that this is a rather unscientific position on the study of crime that lacks both scientific rigor and academic purpose. In this chapter, we emphasize the point that criminologists cannot estimate the extent to which their empirical results reveal something about the causes of crime and that this situation has something to do with the definition of crime. Moreover, we suggest that what criminology really studies is mostly reflective of politics.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Copyright information

© 2015 Michael J. Lynch, Paul B. Stretesky, and Michael A. Long

About this chapter

Lynch, M.J., Stretesky, P.B., Long, M.A. (2015). What Is Crime?. In: Defining Crime. Palgrave Macmillan, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137479358_3

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137479358_3

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Print ISBN : 978-1-349-69368-9

Online ISBN : 978-1-137-47935-8

eBook Packages : Palgrave Social Sciences Collection Social Sciences (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

19 Street Culture and Crime

Mark T. Berg is Assistant Professor of Criminal Justice at Indiana University.

Eric A. Stewart is Associate Professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at Florida State University.

- Published: 28 December 2012

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

Many studies on criminology emphasize the role of cultural mechanisms—the symbolic, relational aspect of social organization—in the uneven representation of crime in society. While dimensions of social structure are also important in this literature, it differs from other criminological research because of the explanatory power granted to culture to account for the origin and scope of socially disapproved behaviors. Cultural explanations still permeate research on criminal behavior in the urban metropolis, but recent questions about the etiology of violence within this environment appear to have revived the cultural perspective, raising the possibility that behavior is shaped by culture. This article reviews criminological research that ascribes criminal behavior to the interaction between individuals and street culture. It examines the propositions derived from urban sociology and recent cognitive-based accounts, focusing on the theoretical and empirical research involving serious crime, particularly violent behavior among individuals living in urban areas.

An extensive inventory of criminological research places emphasis on cultural mechanisms—the symbolic, relational aspect of social organization—to account for the uneven representation of crime within society. While dimensions of social structure are also critically important in this literature, what distinguishes it from other criminological research is the explanatory power granted to culture to explain the genesis and scope of socially disapproved behaviors.

Yet despite their scientific potential, cultural explanations have been the subject of sharp criticism both within and outside academia. Part of this treatment is related to the fact that culture itself is a highly abstract conceptual notion, making the assumptions of existing research especially vulnerable to misinterpretation. At minimum, a profitable theory is one that is testable, falsifiable, and simple. Many theories that specify culture as an organizing principle often articulate a disparate mélange of assumptions, and they do not approximate a sufficient theoretical perspective. These matters have diminished the appeal of cultural explanations, causing some analysts to reject them outright (e.g., Kornhauser 1978 ). As a consequence, for many years criminological research neglected any serious attempts to explain criminal behavior as a product of cultural mechanisms. Now the discipline appears to again be open to the potential for treating nonconventional culture as an influential variable in the explanation of criminal behavior.

Because it is a ubiquitous property of social life, culture has been invoked to account for differences in criminal behavior across multiple units of analyses (e.g., nations, states, neighborhoods, and individuals). Likewise, theories in this domain often vary in their analytical objectives; for example, some specify cultural variables to explain the spatial or temporal distribution of crime rates, while others model such differentiation among individuals or small groups. Criminological research that applies a cultural explanation to individual-level behaviors often explicitly or implicitly integrates a consideration of contextual processes. In fact, neighborhood context has long been salient to research on the normative dimension of criminal behavior because it is a social setting where network-based norms are inhered and enacted. As Matza ( 1964 , p. 25) has remarked, “the ideas and practices that are transmitted within groups and neighborhoods occupy a strategic position in the sociological view” of crime and delinquency. Any scholarly discussion of culture and criminal behavior must consider the social context in which individuals are embedded in order to fully explain the nature of these effects.

The current chapter concentrates on criminological research that specifies criminal behavior as a product of the interaction between individuals and a local cultural context. Specifically, we organize our discussion of existing material within a multilevel interpretation and delineate the linkage between individual and ecologically situated processes. Attention is paid to the theoretical and empirical research involving serious crime, particularly violent behavior among individuals who inhabit urban environments. Just as in the mid-20th century, cultural explanations still permeate studies of criminal behavior in the urban metropolis. More recently, however, questions about the etiology of violence within this environment have sparked an apparent revival of the cultural perspective, suggesting novel ideas about how culture operates to affect behavior. Taken together, these efforts prompt the following conclusions:

Neglected by researchers and overshadowed by alternative theoretical frameworks, cultural explanations are again reentering theoretical discussions about the etiology of crime. But unlike earlier intellectual trends, contemporary research commonly applies cultural principles mainly to explain violent behavior in urban contexts. Empirical studies have largely supported hypotheses derived from this work.

The contributions of Anderson ( 1999 ) and Wilson ( 1987 , 1996 ) set in motion current efforts of researchers to understand the interplay between neighborhood socioeconomic conditions, race, cultural organization, and patterns of socially disproved behavior, including violence and illicit marketplace activities.

When culture is invoked by contemporary scholars to explain urban violence, discussions often focus on the behavioral consequences of “social isolation” (Wilson 1996 ); however, alternative formulations derived from a cognitive interpretation of culture challenge the formal logic of this perspective.

In section I , we discuss assumptions contained in several early theoretical treatments of culture and criminal behavior, and we discuss the reasons that interest in cultural theories waned for a period of several years. Section II evaluates developments in the study of culture and criminal behavior; we focus specifically on the propositions derived from urban sociology and recent cognitive-based accounts. The chapter’s conclusions are reemphasized in section III .

I. Cultural Processes and Crime: Early Perspectives

A. shaw and mckay and neighborhood context.

Social scientists have long sought to explain patterns of unconventional behavior using the related conceptual devices of norms and values. Scholars in the Chicago School operated from this position while investigating the behavioral consequences of normative change among people undergoing the social transition from traditional settings to modern urban life (e.g., Park 1925 ; Thrasher 1927 ; Wirth 1938 ). Working in this intellectual climate, Shaw and McKay fashioned a pioneering model centered on the concept of “social disorganization” that implicated both the cultural and network-related aspects of neighborhoods as sources of delinquency. It is important to begin with the foundational work developed by these Chicago School scholars in order to make sense of the differences and similarities between traditional and contemporary explanations. By and large, scholarly treatments of Shaw and McKay gloss over the micro-level cultural component of their work; however, their ideas are critically important to understanding subsequent research in this domain, and continue to be of relevance to contemporary thinking.

Shaw and McKay’s ( 1942 , 1969 ) model conceived of the local neighborhood as an important context for delinquency because it represents a place where personal and primary group relations are formed; these ensuing relations are integral to mechanisms of social control (i.e., social regulation) and socialization (i.e., culture). As for the latter aspect of their model pertaining to the nature of cultural processes, Shaw and McKay ( 1942 ) theorized that the normative rationale for criminal behavior is transmitted through face-to-face interactions, eventually becoming embedded as a delinquent tradition within certain neighborhoods. Oral history or biographical data revealed that “these traditions of delinquency [were] preserved and transmitted” not only by peer contacts but also through the family network (Shaw and McKay 1971 , p. 260). Furthermore, Shaw and McKay formulated two key assumptions relating to the content of culture in poor, high-crime neighborhoods (see Kobrin 1971 ). First, they argued that delinquent norms coexist with mainstream norms. Stated in their words, the typical delinquent community is “often distinguished by a confusion and wide diversification of its norms or standards,” ranging from orientations that are strictly conventional to those that are delinquent in character rather than to a relative consistent and conventional pattern (Shaw, McKay, and MacDonald 1938 , p. 101). Second, Shaw and McKay stressed that the “dominant cultural tradition in every community is conventional, even in those having the highest rates of delinquents” (1969, p. 320). Put differently, they believed that while delinquent conduct norms are salient within high-delinquency neighborhoods, they are a numerical minority relative to mainstream norms (see Whyte 1943 ). Taken together, Shaw and McKay understood the culture of impoverished neighborhoods to be characteristically (1) heterogeneous or conflicting, (2) while largely conventional in nature.

Shaw and McKay’s ( 1969 ) explanation had a dual explanatory focus, one that emphasized the macro-social or community distribution of crime, and the other that elaborated the micro-social processes, particularly those occurring in primary groups, which facilitated the transmission of criminal traditions in high-crime areas. Shaw and McKay’s emphasis on neighborhood-based social networks as carriers of cultural resources effectively merged these macro and micro explanations. Social change or urban growth dynamics became a less salient premise for their model as it developed. Indeed, analytical and theoretical focus shifted from the linkage between urban growth dynamics and crime to that of social status and crime. Shaw and McKay ( 1942 ) slowly recast their explanatory framework to account for the link between neighborhood inequality and stratification and patterns of criminal behavior. As a result, their model attributed theoretical power not only to intergroup processes but also to the role of structural position in shaping criminal conduct norms in poor urban neighborhoods.

Subsequent theoretical treatments of cultural processes integrated conceptual developments from Shaw and McKay’s earlier model (see Short 1971 ). Kobrin ( 1951 ), for instance, theorized that a duality of conduct norms, rather than hegemony of either criminal or conventional norms, was “the fundamental sociological fact in the culture” of high-crime communities (p. 656). Also within the theoretical vein of social process, Sutherland’s ( 1947 ) model identifies a dynamic, ongoing course of interaction among individuals and groups that produces criminal acts (Matsueda 1988 ). His model assumes that differential social organization—or the relative exposure of groups and actors to ratios favorable and unfavorable to crime—is a feature of collectivities, including communities. Certain groups, such as youths from poor urban areas, theoretically are at risk for involvement in crime because their “social organizational context” exposes them to an excess of definitions favoring crime (Matsueda 1988 , p. 282). Also, Cloward and Ohlin’s ( 1960 ) strain-based theory modified the cultural aspects of Shaw and McKay’s thesis to suggest that the alignment between conventional and criminal networks was necessary to explain neighborhood variation in the nature of criminal activity.

B. Socioeconomic Position and Subcultural Models

As noted, characteristics of social structure, including inequality and stratification, became particularly salient in later variants of Shaw and McKay’s model in order to account for the relative stability of high-crime rates in impoverished areas. To be sure, Sutherland and others did not explicitly theorize the relevance of these characteristics for cultural processes or crime. Nonetheless, the linkage between social status and involvement in delinquency permeated subsequent developments in cultural theorizing. For example, Cohen ( 1955 ) developed a theory from these earlier theoretical strands—in addition to Mertonian strain theory—in which aspects of social status and cultural mechanisms were logically united. His perspective maintains that “structural deficits” experienced by working-class youths translate into “cultural deficits” when viewed against middle-class standards. Groups of working-class youths collectively reject middle-class values and devise an oppositional status system where respect is conferred to those who excel at criminal behaviors. Members of the so-called delinquent subculture develop dependence on their system for identity, which gives it a strong degree of salience. To account for the distribution of delinquency (including violence), Cohen’s ( 1955 ) theory grants causal power to group-based subcultural processes; moreover, it stipulates that these processes are disproportionately located among working-class youths.

Further evidence of a social status-culture link is evident in Miller’s ( 1958 ) perspective; he delineates the unique cultural conditions motivating lower-class adolescents to engage in delinquency. Miller posits that the lower-class cultural system is distinctive in its symbolic content, or what is referred to as “focal concerns.” Personal rank is earned by exhibiting behavioral hallmarks sanctioned by the lower-class cultural system; for example, displaying physical prowess in the face of a rival incurs a reputation for toughness—a core focal concern. Wolfgang ( 1958 , pp. 329–30) also tethered class and culture together to account for the social origins of serious offending. He reasoned that a “subculture of violence” exists among a portion of the lower class “where toleration—if not encouragement—of violence is part of the normative structure.” Building on these assumptions, Wolfgang and Ferracuti ( 1967 , p. 153) later proposed that among groups who display the highest rates of homicide “we should find in the most intense degree a subculture of violence.”

Combined, the foregoing authors set the foundation for a theoretical perspective invoking an oppositional culture to explain the distribution of violent behavior within the population, and it construes socioeconomic factors—namely class, sex, and race—as correlates of violent conduct norms (Luckenbill and Doyle 1989 ). These models assume that oppositional norms are endogenous to structural position and vary closely with the commission of violent behaviors (see Hirschi 1969 ). Providing support for these expectations, Heimer’s ( 1997 ) research revealed that “lower SES youths are more likely … to engage in violent delinquency because they have learned definitions favorable to violence through interactions with parents and peers” (p. 820). Likewise, Markowitz and Felson ( 1998 ) demonstrated that lower-class respondents in their study were more likely to emphasize retribution and courage, and these attitudes mediated status differences in violent conduct. Recall that some theorists claim that race differences in violence are attributable to differences in adherence to subcultural values. A study of prison misconduct found that African American inmates had higher rates of violence but lower rates of alcohol and drug offenses; these patterns mirror those observed in free society and support notions from subcultural theory about the role of subculture in explaining racial variation in offending (Harer and Steffensmeier 1996 ). Still, empirical studies have found that race differences in cultural beliefs are partially a product of differences in neighborhood contextual conditions. For example, multilevel research by Sampson and Bartusch ( 1998 , p. 800) discovered an “an ecological structuring to normative orientations” whereby alternative orientations are inhered in neighborhood context and not necessarily common to low-status individuals. These findings demonstrate the salience of neighborhood context, as opposed to only individual-level characteristics (e.g., race), in shaping demographic variation in normative orientations.

Moreover, Short and Strodtbeck’s ( 1965 ) multimethod study of gang youths found that middle-class youths, relative to their lower-class counterparts, were more adamantly opposed to negotiating compromises with conventional standards, while lower-class youths placed greater value on displaying a “tough-guy” reputation and displaying skills at fighting. Furthermore, Horowitz’s ( 1983 ) study of a poor Chicago community identified a distinctive set of values organized around a code of honor that conflicted with conventional standards of interpersonal conduct. She found that the behavioral imperatives of the code sanctioned violence as a means of achieving an honorable reputation in the face of challenges to self, especially those that occurred in view of an audience. Similarly, Schwartz’s ( 1987 ) ethnographic investigation detected community-level differences in the degree to which alternative conduct norms motivated youths to engage in criminal activity. His data showed that youths from the poorest urban neighborhood, who exhibited a relatively extensive involvement in delinquency, were exposed to a cultural milieu where violence was sanctioned, unlike those from the other less impoverished communities.

C. Criticism and Controversy

By the late 1970s, a wave of criticism upended the intellectual merit of theoretical perspectives that granted power to cultural mechanisms. For example, Suttles ( 1968 ) argued that residents of slum neighborhoods do not necessarily reject conventional norms but suspend them to negotiate a practical, rather than ideal, “personalistic order” because the standards of wider society are inapplicable within their environment (pp. 3, 6). Later, Kornhauser ( 1978 , pp. 76–79) argued in that culture is “attenuated” or “disused” in poor neighborhoods, and she challenged the importance of unconventional values for explaining criminal conduct (see Warner 2003 ). Furthermore, she reasoned that “slum life”—her reference to a distinctive culture among residents of lower-class neighborhoods—“lacks complete definition and manifests considerable in-authenticity” (p. 134). Kornhauser thus interpreted Shaw and McKay’s ( 1969 ) theory as a pure control model while accusing Sutherland ( 1947 ) of assuming a theoretical position of “boundless cultural relativism” and envisioning a society “without a center” (Kornhauser 1978 , p. 192). From Kornhauser’s perspective, Sutherland’s theory “contains a hidden but simple variety of structural determinism” (p. 190); moreover, it denies humans a distinct nature and assumes that all behavior is valued.

In a similar line of analysis, Kornhauser accused Miller ( 1958 ) of theorizing cultural processes that exist “only in his imagination” (p. 208). As for Wolfgang and Ferracuti ( 1967 ), their model is allegedly “restricted to the empty search for a subculture to account for the roots of violence” (Kornhauser 1978 , p. 188). More broadly, Kornhauser questioned whether a modern society could sustain a culture that genuinely sanctions predatory behavior, for it would have no value in societies whose existence depends on lawful interactions. Despite her critique, there was not a uniform scholarly opinion about the impotence of nonconventional culture as a causal mechanism. For example, an empirical study by Hindelang ( 1974 ) challenged prevailing notions about value consensus, suggesting that youths do not universally subscribe to a common value system irrespective of their delinquent involvement (e.g., Sykes and Matza 1957 ).

As time has revealed, the devastating consequences of Kornhauser’s critique for the theoretical vitality of cultural perspectives cannot be ignored (see Matsueda 1988 , 2007 ). But beyond this, the politically charged controversy involving the “culture of poverty” thesis further marginalized any discussion of culture in social science research. For these reasons, subsequent developments in criminological theory placed very little emphasis on cultural variation as an explanation of crime. Instead they held a consensus view of the social order and thereby sought to explain law violation only as a product of a breakdown in regulation (e.g., Bursik and Grasmick 1993 ).

II. Cultural Processes and Crime: Recent Developments

For many years, the controversy surrounding cultural models dissuaded young scholars from making a strong effort to examine unlawful or deviant conduct through a cultural lens (see Small, Harding, and LaMont 2010 ). Wilson’s ( 1987 ) research on the implications of urban poverty reignited scholarly interest in cultural explanations of unconventional behavior particularly within predominantly African American neighborhoods. According to his thesis, large-scale processes of deindustrialization—a loss of manufacturing jobs coupled with a decline in real wages among low-skilled workers—engendered an outmigration of middle-class residents and increased the proportion of impoverished families, all of which fueled an erosion of neighborhood social institutions. Wilson believed these transformations deprived residents of not only important institutional resources but also conventional role models who engage in legitimate adult behaviors. According to Wilson ( 1996 ), even though poor neighborhoods exhibit high levels of social integration, they are socially isolated from elements representative of mainstream society. Their social interactions are often “confined to those whose skills, styles, orientations and habits are not as conducive to promoting positive social outcomes” (Wilson 1996 , p. 64). Wilson believed that such social isolation contributes to the formation of “ghetto-related” cultural models. While these models may prove useful in the local milieu, they are inadequate to the attainment of success in wider society.

Expanding on these ideas, Sampson and Wilson ( 1995 ) proposed that the concentration of socioeconomic deprivation, together with social isolation, fosters cultural diversity and gives rise to “cognitive landscapes” or “ecologically structured norms” that are less apt to assign negative sanctions to violent and illegal conduct. Moreover, the sheer visibility of ghetto-related behaviors in public spaces, brought about by residents’ collective inability to contain them, gives the appearance to residents that these behaviors are acceptable. Sampson and Wilson ( 1995 ) suggest that residents of poor communities often behave in ways consistent with ghetto-related norms for two reasons: as an adaptation to structural constraints and because they are modeling conduct that is common in their neighborhood milieu—this conduct proves to be useful in local social interactions. Moreover, the authors imply that residents do not internalize or espouse ghetto-related norms, despite their behaviors (see Sampson and Bean 2006 , p. 16). Hence, deviant or illicit behaviors are not genuinely reflective of their actual normative orientation toward nonconventional models. Combined, Wilson, and Sampson and Wilson invoke culture to account for the disproportionate concentration of serious violence among residents of poor neighborhoods. Early theoretical models of culture and crime tended to exaggerate group-based differences in violent conduct norms by suggesting a strong and ubiquitous status-culture linkage, which seemed to invite sharp criticism. Sampson and Wilson’s framework implicitly adopts a notion of cultural effects conceived as practical devices —rather than oppositional values—that coexist alongside mainstream models and emerge as an adaptation to socioeconomic exigencies. Stated differently, residents of impoverished urban environments engage in illicit conduct because it theoretically serves various symbolic (e.g., status) or material (i.e., financial) needs in their local milieu. Nowhere do these models explicitly assume that members of these communities often act in accordance with internalized oppositional norms. By Sampson and Wilson’s account, most ghetto residents harbor mainstream beliefs; structural constraints cause a disjuncture between these beliefs and the nature of their actual behaviors. Neighborhood context is therefore granted a strong causal role in the genesis of illicit behavior.

Explanations derived from urban sociology do not specify a distinctive oppositional culture as did earlier theoretical statements in which culture is an organizing principle (e.g., Cohen 1955 ). By contrast, Anderson’s work (1999) recasts discussions of cultural processes in a way that appears to assign a unique cultural orientation to some residents of poor urban neighborhoods. More specifically, Anderson ( 1999 ) describes the existence of a “street code” embedded in the social fabric of an impoverished Philadelphia area. The street code he observes is a collection of informal rules that direct interpersonal public behavior, which provides a rationale “allowing those who are inclined to aggression to precipitate violent encounters in an approved way” (Anderson 1999 , p. 33).

At the heart of the street code is an emphasis on respect. Residents of poor neighborhoods, particularly young males, develop a social identity that is consistent with the street culture in order to manage the demands of a social context maintained by violence. In fact, Anderson ( 1999 , p. 131) observed adolescents who precipitated altercations with the primary focus of building respect on the streets; some appeared to crave respect to the point that they would engender their physical well-being. Within this context, it is imperative for an individual not to yield to challengers because doing so conveys weakness, which ultimately enhances the probability of future victimization.

Moreover, Anderson argues that beyond factors such as structural adversity and a history of racial oppression, a prevailing climate of legal hostility sustains the code of honor, making residents reluctant to ask the state to intervene in conflicts (see Cooney 1998 ). Many come to perceive the criminal justice system as unfair, unresponsive, and discriminatory against minorities. As a result, residents are unlikely to turn to the police or courts to resolve interpersonal disputes, making violence a more probable mode of conflict management.

Anderson ( 1999 , p. 82) also describes the urban landscape he observes as occupied by two coexisting groups of people: those who hold a “decent” orientation and those whose lives conform more closely to standards of the code—a group he refers to as “street.” All residents have a strong incentive to be familiar with the behavioral imperatives of the street code, regardless of whether they adhere more closely to the normative expectations of a conventional or oppositional orientation. Such knowledge is necessary for operating in public (Anderson 1999 , p. 33). Those cognizant of the street code recognize how to properly comport themselves, how to circumvent serious confrontations without losing respect, and the appropriate strategies to manage interpersonal conflicts, including incidents in which they were victimized. Residents who are ignorant of the rules of the code may inadvertently act in a manner that jeopardizes their own safety.

As Matsueda and colleagues ( 2006 , p. 339) note, the honor culture is an institutional feature of street life and it produces a “strong incentive to acquire knowledge of its expectations.” In this way, the street code represents an ecologically situated property that governs interpersonal action, independent of actors’ own cultural inclinations. As more people in a neighborhood engage in ways that conform to the street culture, the level of violence escalates and the number of people who rely on violence for defensive purposes increases.