The Nature of Self Perspectives from Buddhism and cognitive science. A conversation with Anne Klein and Anil Seth

Four human figures hold hands, composed of many cut out circles that blend into more circles, symbolizing the interconnected nature of self. We invite readers to explore your own interpretation. Artist: Sirin Thada

One of the most fundamental ways that we can be changed by contemplative practice relates to our sense of self. Both the Buddhist tradition and modern cognitive science have converged on core ideas suggesting that our everyday sense of existing separately from the world around us, and consistently over time, is mistaken. And realizing the interconnected, dynamic, and context-dependent nature of the self is a key insight to reduce suffering.

Mind & Life’s Science Director, Wendy Hasenkamp, spoke with experts from these two traditions to learn more about how they approach this important concept, and implications for expanding our view of self. Rather than summarize their points, we wanted to share their conversation directly with readers, in the spirit of dialogue across traditions that’s been core to Mind & Life since the beginning. (Note: This conversation has been edited for clarity, with the approval of all participants.)

Wendy Hasenkamp : Let’s start from the Buddhist side. Anne, from your perspective and the lineage that you’ve studied, can you speak to the normal, everyday experience of self, and why we experience it that way? And, as I imagine we’ll also get into, why our everyday sense of self is mistaken?

Anne C. Klein : Sure. And I should say, to start, there’s no such thing as “Buddhism.” It’s Buddhist traditions, plural. I am coming mainly from the Indian and Tibetan traditions, which are closely related. So, what does the self look like from these Buddhist traditions? What it looks like, and what it feels like is something sustained, something continuing.

I think there are actually two things going on. There’s, “I’ll see you tomorrow.” And if we look behind that, there’s a sense that I’m going to be here tomorrow, and it’s going to be the same me and it’s going to be the same you, and the same room, and all of that. So there’s definitely an abundance (an overabundance from the Buddhist perspective) of an idea of continuity and permanence. Certainly, we’re aware of change, but it’s accompanied by a sense that the same self is experiencing different things, which is quite different from the self itself, as it were, being continually renewed, reconstructed, and so forth. So, there are palpitations of permanence, which Buddhism immediately points out as “wrong view.” It’s mistaken. The sense of solidity, and that the self is somehow a unitary thing, is wrong.

And it’s also a pretty stable impression, until one looks into it. The mind that analyzes will pretty quickly discover that it can’t really lay a hand, so to speak, on the self. And that is the perspective that the Buddhist traditions encourage. The kind of analysis that neuroscience is doing—looking very granularly at things, brain activity, et cetera, the various neurological and bodily events that give rise to a sense of self—that’s an explanation that is useful on all sides, east and west. But what Buddhist traditions are interested in is how that sense of self is mistaken.

So we have assumptions, the generally untended, unconscious assumptions that we make about me. “I am.” What the Buddhist traditions are interested in is identifying very carefully what we think and what we feel, because both help us identify the mistake that we’re making. To understand really what we are, we first have to unmask what we think we are. And then we have to look into that more closely to discover what we really are, because what we think we are doesn’t actually serve us. We don’t recognize the totally interdependent nature of ourselves.

To some degree, we can and do realize interdependence, and science certainly does. One thing that strikes me is that science seems to be looking at things and pulling them apart, and noting the constructed nature of experience in a way that’s very much in alignment with Buddhism. But I can’t quite tell—I’ll just put this out there for you, Anil—how much scientists are taking this in the direction of the contemplative. Which is to say, developing techniques so that we can experience the self in the actual, constructed, interdependent way it actually exists.

And why do we think that way about the self? Well, the Buddhists say we think that way because that’s how things look to us. And the senses are actually set up for failure, as far as a direct perception goes, about a lot of things. There is a very important category in the Buddhist traditions of valid perception, correct perception. It does exist, particularly in the sutra systems—inference, inferential cognition based on reasoning, that’s a valid perception. There’s smoke, which means there’s fire, et cetera. It’s a valid perception.

For Buddhists, direct perception is valid because it reflects the precise details of everything that appears to it. Sensory perception is very important. It doesn’t have the mistake of conceptual thought, which is always mistaken—even if it’s right! It’s always mistaken because in the inner world of the thinker, the thing that you’re thinking about, the image you have, at some level seems to be the real thing. You don’t feel that a tree is in your head exactly… you feel like you’re really thinking about a real tree. And for the early Buddhist systems, that’s wrong. Thought is wrong in that respect, direct perception is not.

In the Mahayana, or Great Way traditions, direct perception is mistaken in a way, too. It’s mistaken because it always looks like there’s something “over there.” The here and there problem. The self and other, the in and out, the me and you problem. These are problems that Buddhism is very interested in solving. From the Buddhist perspective, this issue is the root of desire and hatred, which is the root of all suffering—the failure to recognize the wholeness of our experience, which includes the world that seems to be external.

Wendy Hasenkamp : Thank you so much, Anne. Anil, I’m sure you have lots of thoughts from the cognitive science perspective.

Anil Seth : I do. That was a wonderful introduction and summary, and there’s definitely a lot to talk about there. My own disclaimer is I’m not here to represent a single universal consensus view from cognitive science—there’s a lot of disagreement and I am ignorant of a lot of things that are said in these fields about the self. So, I’m only speaking from what I know.

Now, if I’m thinking about this same overall question of what does the self look like, and why do we think about the self this way… From the perspective of cognitive science and neuroscience and a more Western analytic, philosophy of mind perspective, there has been a lot of development.

A good place to start (a bit of a straw man) is of course, with Descartes. “I think, therefore I am.” Implicit in that statement is that the self is associated with a disembodied, rational mind. That was a view that had become very much part of the architecture of how we think about modern cognitive science—the Cartesian divide—where rationality is associated with being human, it’s associated with being conscious. And we’re left with this view of the self as intimately bound up with rationality, with thoughts, with cognitive processes of some sort, with the idea that the self is this thing, this essence, this identity that is the recipient of perceptions, that does the perceiving, that then figures out what to do next. That, in your example of “I’ll see you tomorrow,” is that center of rational mind that is present from one day to the next, that will see you tomorrow. I like the way you put it, that it’s the same self experiencing different things—this idea of continuity, which becomes reified into essence. But fortunately, partly through its interaction with some of the more spiritual Eastern traditions , this view of the self has been challenged, I think in very helpful ways.

Another line in which self has been challenged is in the work of neurologists and psychiatrists, showing that the self cannot be this unitary essence of a person, because it can disintegrate in various ways that are difficult to explain in terms of the Cartesian self or soul. You see people who lose certain aspects of (what seem to be definitional of) self, while others remain. So people can lose their memories of what’s happened to them, they can lose the ability to lay down new memories, yet in many ways seem to be the same person and still have the experiences of being embodied, of volition, of free will, of agency—all these things can be intact. Other people can lose those aspects of self, for instance people with a condition called akinetic mutism, where they lose the ability to make any voluntary actions. Colloquially, one might say they’ve lost their free will, but other aspects of self remain. So, all of these individual cases speak against this unitary essence of self. Oliver Sacks and others have written beautifully about this, collecting and describing a menagerie of examples.

And then there’s just been this general shift, which I’ve been particularly attracted to over the years, from the self as something relatively disembodied and abstract, to something that is fully and fundamentally about the body. This is a shift that we see more generally in cognitive science, too. Cognitive science was dominated, and still is to a considerable degree, by this computational metaphor of the mind—that the way to understand what the mind does, and its relation to the brain and the body, is as a software program relates to the computer that runs it. This, I think, is not a helpful way to think about the relations between self, mind, brain, body, and world.

There’s been this general shift… from the self as something relatively disembodied and abstract, to something that is fully and fundamentally about the body.

And of course, this is not a new insight; it’s been there actually from the very origins of cognitive science in the mid 20th century. People working within a tradition that was then called cybernetics were fully aware that in many ways, the brain is fundamentally a control system. It’s trying to control the body in an environment; it’s not detached from the body or the brain. But as this computational metaphor of mind gained strength (and it did so because it was very productive—people could build computational models, they could get computers to play chess, to solve these tasks that were thought to be foundational to human rationality), there was just less emphasis on the hardware that was underlying these abilities and on what that hardware was doing. And the body became just this vehicle that would move the brain from meeting to meeting. That was its purpose.

More recently, there’s been a fundamental shift, recognizing that the reason we have brains is not to solve abstract problems, to be this disembodied seat of Cartesian rationality. Instead, it is to keep the body alive. And this is true not just for humans; it’s true for all species. Thought of in this way, the experience of self plays out on many different levels for humans. Indeed it plays out at “higher,” more abstract levels. We are capable of stringing memories together over time, having this sense of continuity of identity, this narrative self. We’re also, as I think you, Anne, pointed out beautifully in your podcast interview with Wendy, this intrinsic interdependence. We are made by, partly constituted by, our relations with the world and with others. Our sense of self is refracted through the minds of our social networks.

But then there are all these other aspects of self, too. There’s the sense of seeing the world from a particular perspective, a first-person point of view. That seems to be a fundamental aspect of what the experience of selfhood is like. Then there’s the experience of being the author of our thoughts, the instigator of our actions—an aspect of self we might often call free will.

Then even below that, we have the more deeply embodied aspects of self. And these begin with emotions and moods. Experiences of emotions and moods are fundamental parts of what it is to be a self. And emotions, when you probe them by reflecting on their experiential nature, are deeply embodied. We feel emotion in our bodies. And in fact, it’s when we stop allowing ourselves to feel emotions in our bodies that we can get into trouble, and start ruminating, and our emotions can lead us astray. And it’s by relocating our emotional experience within our bodies that I think we’re able to build emotions more productively into our lives.

Even more fundamentally, beneath moods and emotions, there seems to be this basic, shapeless, formless experience of just being alive. I suggest that the fundamental roots of selfhood lie in this experience of being a living organism, which makes us fundamentally different from computers or robots. In the human body, brain, biological organism, there’s no sharp divide between the mindware and the wetware, as there is between the software and the hardware in a computer.

These days, we talk about enactive cognitive science, embodied cognitive science, extended cognitive science —each emphasizing in different ways how brain, bodies, and environments are intimately coupled. These are very important developments, because they invert how we think about the self. Instead of starting with a disembodied rational mind, we realize that a rational mind is never completely separate from the body. Antonio Damasio pointed this out long ago in Descartes Error—without input from the body, without an appreciation of the bodily context, we make poor decisions.

There’s one other thing that I wanted to comment on that you said, which I thought was really a very rich area of resonance, which is this idea of ‘direct’ or ‘correct’ perception. Again, there are a number of views in cognitive science about this, the extent to which direct perception—this immediate access to the world ‘as it is’, or the body ‘as it is’—happens, or is possible. I tend to favor a more indirect view that everything that we experience is constructed to some extent, but of course, it’s not constructed arbitrarily. I tend to think of ‘useful’ perception rather than correct or incorrect perception. As the saying goes, we perceive the world not as it is, but as we are.

In this podcast episode, Anil further discusses the role of the body in perception, the self as a construction, and more.

So yes—we smell smoke, we see flames, there is a fire there. But the way in which the smell of the smoke and the visual experience of seeing the fire appears in our experience is not actually what’s there. Still, it’s a very useful experience. In my language, it’s a very useful brain-based prediction about the causes of sensory inputs that themselves don’t have any smell or color, but they do reflect what’s happening in the world. There is something objective actually happening in the world, something that has biological relevance, and something that we perceive as such, in our experience of seeing flames and smelling smoke.

There are many ways in which we can consider what it means to say that something really exists. This question gets very deep, and answers will depend on whether you ask a religious scholar, or a theoretical physicist, or a cognitive scientist. I’ve come to think of the self as existing in a somewhat similar way to, let’s say, how the color red exists (or any color). Colors don’t exist objectively in the world as mind-independent properties, but it’s nonetheless extremely useful for our visual systems to construct experiences of color. Colors reveal that an object or surface is the same object or surface, even as lighting conditions change. And this is useful in many ways. You can tell any number of stories about why it’s useful that our visual systems create colors from a continuous colorless electromagnetic spectrum.

The same line of thinking usefully illuminates the way we think about the self. There is no actual objective mind-independent essence of selfhood, but it’s still a very useful aspect of our experience for the brain to construct. And it’s also very useful for it to be constructed as being continuous over time.

Why is this? Why do we experience ourselves as being relatively unchanging over time? Well, to some extent, it is because we are relatively unchanging over time. If I walk from this room to the next room, it’s the same body that goes with me, it’s pretty much the same bodily self, even though the room is no longer the same room. So indeed, there is a continuity to the experienced self that is perhaps stronger than the rest of our experiences. But I think we probably experience the self as even more continuous than the objective continuity of that which underpins these experiences of self warrants. I think that may be because it’s almost as if the self is bringing itself into being through predicting itself to be continuous over time.

To come back to a leitmotif of our conversation, this idea about how things appear to us being how things actually are… A guiding principle for me is to take that as always an open question, and as a challenge. And to assume that how things seem is probably not how they actually are, ever. This does not mean that how things seem is wrong, or has no value. It just means we shouldn’t reify how things seem as how they actually are—whether it’s a particular way of experiencing the self, a way of experiencing color, a way of experiencing free will, or any other thing that appears in the flow of our experience.

Wendy Hasenkamp : I think it’s really interesting, the difference between these perspectives on the role of perception, and the accuracy of direct perception (or not). It sounds like, Anil, from the cognitive science side, you’re suggesting that as the perceptual information comes in, it’s already constructed and filtered through the patterns we’ve developed from our past experience. From the Buddhist side, I have a sense that there’s a distinction between the original raw perception, and then the conceptual layering that comes after. I’m wondering if that might be something that’s going on here between your perspectives.

Anne C. Klein : That’s so interesting. And what a wonderful narrative, Anil. I’ve been trying to track a path to juxtapose analogs or parallel processes that are similar in Buddhism and yet different. And one of them was this concept of prediction that you’ve talked about so elegantly, Anil, and that I think you also were just pointing to, Wendy.

For a Buddhist, it usually gets translated as imputation. We’re imputing, where we see a bunch of dots, let’s say. At first it’s not clear. And then I draw a few more dots [drawing two slanted lines meeting at the top] and maybe it’s a ball rising and falling. And then, as you watch your mind, very slowly, watch what happens. There’s a moment where your perception changes… [drawing a series of dots connecting the other two lines] and all of a sudden, “Oh, it’s the letter A!” So you can ask, what exactly happened? You can feel it, if you’re attuned to it.

Anil Seth : That’s a good example of exactly what I was talking about, when I was talking about prediction.

Anne C. Klein : Right. And what’s similar in Buddhism is the Sanskrit term arthakriya, this idea of the ability to perform a function. What these things that we’re describing do, that are called conventional phenomena, is that they perform functions. It’s true that I make up the idea of a pen far beyond what exists here, but it’s also true that I recognize that this is something I can write with. And I can; I cannot write with a cup. These are conventionally valid distinctions. So I think that’s important and it’s definitely a resonance.

One of the most important distinctions made in Buddhist theories of mind and awareness is between conceptual thought and direct perception—thought is abstract, it will not get to the real experience. Not only is wisdom famously inexpressible, but as we used to say in grad school, the taste of an orange is also inexpressible. You can’t really go there with thought and with words.

So, if I say ‘the ocean’—we’re not looking at the ocean right now, alas. So we all know what the ocean is, but there’s no direct experience of it in this moment… It’s just a mental image and it may not even be a representational mental image, but just something that allows me to know what ‘ocean’ is. It might just be the letters of the word that appear in my mind. But even if I imagine the ocean, it’s an abstraction compared to the real thing. My image is not going to be responsive to granular changes, shifts in light and wind, and all of that, the way direct perception is. And to bring in the body, as you were mentioning—Buddhists have very sensitive understandings of the body, and a lot of similar ideas about emotions being in the body—in thinking about perception, the body is also most easily, in a way that’s different from other things, accessible to direct experience.

Anil Seth : Absolutely. To me, one of the big challenges, but also interesting differences when it comes to perceptions of the body compared to perceptions of the world (whether it’s an ocean or whatever else), may be that there is a sense of enhanced directness for body-related experience, simply because the brain is more directly connected to the body than it is to the outside world. The brain is connected to the interior of the body, through sensory channels. We call these interoceptive channels. There’s the vagus nerve, and many other bundles of nerves, that signal things like how the heart is beating, what the gastric tension is like. And of course, we’ve got a nervous system in our gut as well. And there’s also circulating hormones. There are all sorts of ways in which the brain and body are in more direct contact than the brain and the world beyond the body.

So there are differences between our perceptions of the world and of the body, but I think that there are also similarities. In both cases, the signals that are impinging on the brain from the body (and the brain itself is part of the body), never reveal their causes transparently. The brain always still has to do some work of interpretation. And we notice this in our lived experience, too. Let’s say my heart is racing. What does that mean? Am I afraid or am I excited? That interpretation is not just given by perception of an accelerated heart rate; it depends on the larger contextual interpretation of what the body is doing—as the psychologists William James and Karl Lange pointed out long ago.

And then the idea of this separation between abstract conceptualization and direct perception—this idea certainly has resonances in cognitive science, too. In this context, we talk about the concept of cognitive penetration. To what extent are our perceptual experiences affected by—penetrated by—our cognitive framing?

Classical cognitive science would impose a fairly sharp distinction—here we have perception, and here we have cognition. They interact, but they don’t interpenetrate. From my perspective, this view is now giving way to a more continuous view of how different levels of abstraction interact so that our expectations, our cognitive framing, can indeed influence (in some cases down to low levels of granularity) what our perceptual experience is like.

Recognizing this offers opportunities for change as well, because if we learn to frame things in different ways, then we may be able to change our experiences. This is perhaps getting back to a question you raised, Anne—what is the scientific view of the self delivering, in terms of methods for changing our experience? I think probably not a lot that wasn’t already there in the Buddhist traditions of learning to pay attention to our experiences…

Anne C. Klein : Perhaps. There is also the interesting question of, what is the purpose of this change? Why shift our understanding of self? Francis Bacon said, the purpose of science is to relieve the human condition, and Buddhism says the purpose of practice is to leave the human condition. In Buddhist traditions, the purpose of practice is to deliver us from the samsaric world. So that’s a little different. But what you’re saying is very important; again a kind of analog in the Buddhist traditions is the emphasis on many different practices related with the body.

And earlier as you were offering this wonderful narrative of the development in the west of certain ideas of the self… There is a similar development in Buddhism, with a tremendous emphasis on the body—mindfulness of the breath, mindfulness of the body. From the perspective of wanting to cultivate attention, presence to the body is important because the body is always in the present . Whereas our minds, according to most Buddhist ways of describing this, are actually very rarely in direct experience of the present. We wander the halls of our own minds into the past and future, or in fabrications about the present. We are not anchored in present experience.

From the perspective of wanting to cultivate attention, presence to the body is important because the body is always present.

There may be a moment of a kind of mental direct perception. There’s some debate about this, but in some Buddhist traditions, there’s this idea that it’s only the first moment of cognition that is valid. And it’s an interesting position, because I think humanly, we know that the first moment, first meeting, first impressions… there’s something about a first moment. It’s fresher. You don’t yet have an overarching structure and idea of what you subsequently impute and then take to be real and consistent—“Oh, you’re the same person you were here half an hour ago, still here.”

Then practices that involve changing the body into ‘light’—these are very common, particularly in the Tibetan traditions, and also perhaps more common in the early South Asian traditions than we have recognized until recently. And that is a very interesting kinesthetic experience to feel that ‘light’ is moving through your body. Light, Energy, Prana, it’s lung in Tibetan, translated as wind. Actually, what it is, is movement. And I think there’s no denying there’s movement all around in the body, movement of a sort between cells in the brain, so this idea of energy is not a New Age idea. This is a very well constructed idea in many Asian traditions, medically, cosmologically, that there’s movement in the body. There are flows, that’s undeniable. And these relate to the physiology of the body.

So it’s not all about the mind in meditation. This has been a distortion in the west with mindfulness (although if you do it, you pretty quickly discover that of course it’s not just the mind). The mind looking at the breath, changes the whole feel of the body. And feeling that your body is light or could be imagined as light, it just means that there’s an invitation to experience at a more subtle level the movements in the body, perhaps.

Listen as Anne elaborates on Eastern conceptions of the subtle/energy body, the construction of the self and other, and how the body can help us break out of rigid self concepts.

Wendy Hasenkamp : You’ve both named the body as a key to helping us shift to a more correct understanding of self. And Anne, you’ve shared ideas from a few different contemplative approaches. Anil, you said maybe science doesn’t really reach much farther than what contemplative traditions or practices have already allowed. Did either of you want to say anything more on that?

Anil Seth : Maybe I will—I think I was probably being a little unkind to the science on this. I think there are a lot of implications within the scientific tradition that follow from understanding the constructed nature of experience, and the constructed nature of the experience of self. There are many implications for how we think about mental illness, how we think about fractures within society, all these sorts of things. These are not out of alignment (as far as I understand) with what a Buddhist perspective would offer, but they don’t necessarily rely on that perspective to have some impact. The scientific view of perception as prediction, and of selfhood as a variety—or collection—of perceptions is already becoming helpful in clinical practice and therapeutic contexts. These advances all turn on cultivating an awareness that how things appear in experience need not be reified into how they are. And that applies to the self, too.

The scientific view of perception as prediction, and of selfhood as a variety—or collection—of perceptions is already becoming helpful in clinical practice and therapeutic settings.

Thinking this way can change how certain therapies are done—for example, how cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) might be articulated, perhaps focusing more on experiences as well as thoughts and behaviors. And this view may also shed some light on why CBT is effective—why framing things differently, thinking about things differently, may actually have benefits, for example by actually changing perceptual experience.

More generally, this way of thinking about perception and self is giving a new framework for a lot of practices that already have an evidence base for how they affect people. There’s now a deeper understanding of, for instance, what happens when we pay attention to what’s going on in our body, an understanding that may appeal to specific neural mechanisms. It’s worth saying that these mechanistic explanations need not be overly reductionist—for example by highlighting specific brain regions—but can instead emphasize a process, in this case the process of perceptual prediction and its role in bodily regulation. For my money, this kind of process-based explanation does a much better job of reconnecting the brain, mind, and body in ways that help make sense of therapies like CBT.

Wendy Hasenkamp : So we’ve talked a lot about why our everyday perception of self is wrong, and some ways to help shift that. I’d like to close with the question of, why does it matter that we develop a more correct understanding of self?

Anil Seth : I think that there’s enormous value in cultivating a wider appreciation that the way the world and the self appears to one person, is both dependent on others (we are socially interdependent creatures), but also different from others.

It’s because perceptual experience often has the character of seeming objectively real, that it’s sometimes so difficult to understand another’s perspective. When we experience something as ‘really existing’—be it something in the world, or an aspect of self—it’s incredibly hard to appreciate that someone else may be having a very different experience, even within a shared environment. There’s an important question lurking here: why do we experience things as being objectively real, when they are in fact constructions? A superficial answer is that it would be very inefficient for evolution to design our perceptual systems in a way so that we experienced things as generally being unreal. It makes biological and evolutionary sense that if color is a useful way to interpret a visual scene, then of course we’re going to be designed so that color appears to be really part of the world.

The subjective reality of our perceptual experiences is therefore a feature of our minds and brains, but it’s also a bug when it comes to resolving discrepancies, to understanding each other. And I think there’s broad social value in recognizing that even though the world seems objectively to be a particular way, and even though there is an objective reality (I’m certainly not saying that everything is up for grabs), that objective reality might nonetheless be experienced in a different way by a different person. We need to escape not only from the social media echo chambers of what we happen to believe and what news we listen to, but also from the perceptual echo chambers of how we experience the world around us. Because (again it’s my view) there’s never any actual direct perception, there’s only ‘less indirect’ perception. This potential for social recalibration is one reason why all this is important, and one way in which I think the two perspectives do align, but coming from different angles and bringing different things to the table.

Anne C. Klein : Absolutely. The constructivist nature, or as Buddhists will say, recognizing the dependently arisen nature—the imputed nature, the nominally constructed nature—is crucial to liberation, and from a practical perspective for the social, cultural reasons you name. And just because that’s how it is, and our understanding is clearly enhanced by knowing how things work.

I think what’s really difficult is pulling apart the idea that it’s just imputed from the fact that it still functions. Going back to our example, it’s only when you look at the dots that an A occurs; there is no intrinsic A, but it’s still functional. This is the hard thing to understand in Buddhism and I think it’s hard in terms of science also, and that’s why there’s this pushback. But this is why, for certain important Middle Way Buddhist philosophies, direct perception isn’t 100% correct… What would correct even mean?

Anil Seth : Exactly, exactly. That’s the thing. There’s this implicit idea that if only we saw things accurately, if only our perception was completely accurate… but what does that even mean? It doesn’t really make sense to think that perception could ever be 100% accurate. But it can be useful.

Anne C. Klein : It’s clearly useful. And what is it useful for? This would be a whole other conversation, but maybe just to throw it in, I mentioned that Francis Bacon said the purpose of science is to relieve suffering endemic to the human condition. Buddhism says the purpose of practice is not to relieve, but to leave the human condition and its suffering. Buddhist traditions are therefore keen to investigate the nature of knowing itself. That’s the ultimate challenge in contemplative practice. And it’s an ultimate challenge, as you so elegantly described, for the science of mind.

It’s wonderful to be able to be part of such a conversation. Thank you, Anil, and thanks to Mind & Life.

Anil Seth : Thank you very much too. There is so much that we can agree on.

Have something to share? Email us at [email protected] . Support our work with a gift to Mind & Life.

More Insights

Nurturing a Relational Mindset Compassion for each other is the basis for more authentic human connection—and can be cultivated through meditation. By Paul Condon

Understanding the mind

- Mission and Values

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Dialogues and Conversations

- Summer Research Institute

- Mind & Life Connect

- Inspiring Minds

- Varela Grants

- PEACE Grants

- Contemplative Changemaking Grants

- Mentorship Program

- Insights Essays

- The Mind & Life Digital Library

- Mind & Life Podcast

- Online Courses

- Documentaries

- Open Access Academic Papers

- Ways to Give

- Annual Reports

Patricia Pearce

Helping You Be the Change

Knowing Yourself: The First Step in the Spiritual Life

July 11, 2013 by Patricia Pearce

In this blog I write a lot about the spiritual life, which I see as having three components:

- coming to know yourself

- nurturing a relationship with the Reality beyond yourself

- bringing your way of being in the world into closer and closer alignment with what the first two reveal to you

In this post I’m going to share some of my thoughts on the first aspect: coming to know yourself.

Why Bother Knowing Yourself?

In my view, coming to know yourself is an essential aspect of the spiritual life because the more we know ourselves the more accurate our perceptions will be of everything else. Conversely, the less we know about ourselves, the more distorted our perceptions will be and the less able we will be to live into our fullest potential because we’ll be imprisoned by the scripts and identities that have been given us by others.

Although in this age of psychology and self-help programs we might be inclined to see self-knowledge as a Johnny-come-lately concern, knowing oneself has in fact been a focus of spiritual teachings for thousands of years.

The ancient Chinese text the Tao te Ching says: “Knowing others is intelligence; knowing yourself is true wisdom.” Self-knowledge takes us beyond mere information into that elusive thing called wisdom, wisdom that can never be attained, no matter how intelligent we may be, if we remain ignorant about ourselves.

Jesus was touching on a similar theme when he said, “Why do you see the speck in your neighbor’s eye, but do not notice the log in your own eye?” In other words, only by becoming aware of and dealing with our own shortcomings will we be able to see clearly enough to be helpful to others.

When we become aware of the “log” in our own eye we won’t make the mistake of going around trying to “fix” other people. Rather, we will relate to them with the compassion that comes from having faced our own struggles honestly, the compassion without which healing can never happen.

Knowing ourselves also opens the door to our freedom. When we are ignorant of the belief systems, assumptions and behavioral patterns that are operating within us (and that we often mistake for being us), we remain in captivity to them, unable to make wise decisions for ourselves, unable to overcome the self-limitations that may have been instilled in us, unable to recognize when we are being manipulated by those who may consciously or unconsciously seek to activate our fear and prejudice for their own purposes.

The more we come to know ourselves the more we will be able to invite healing and transformation into our lives, to embody compassion, to face our challenges as opportunities for growth, and to experience life as a meaningful adventure.

How Do You Come to Know Yourself?

So knowing yourself is helpful. Fine. But the obvious question is: How do we do it? How do we cultivate self-knowledge? There are probably as many ways as there are people, and in the end I think each of us has to discover and develop what works best for us. I’ll share with you some of the ways I do it.

I’m sure you can guess the first: meditation . Meditation helps me foster the ability to notice my thoughts and feelings without getting caught up in them, a crucial skill to have if I ever hope to live in the world as a free, non-reactive, peaceful presence.

Another practice I employ is working with my dreams . My dreams never fail to give me ample insights about myself, pointing out inner dynamics that are ready to be recognized and transformed.

A third practice I use is active imagination . This is a practice Carl Jung introduced, and it is a way to enter into intentional dialogue with the many aspects of myself. We each embody multiple facets, interests and desires, and they can sometimes engage in an inner tug-of-war that keeps us paralyzed and confused about our priorities and the life direction we want to take. Active imagination helps us listen to each of those aspects whose voices need to be heard and honored before they will join together as allies rather than adversaries.

Creative expression can also be a portal for self-knowledge. Nearly 20 years ago I happened upon a book which has since become well-known and which changed my life: The Artist’s Way by Julia Cameron. The reasons why it was the right book at the right time for me is a longer story that perhaps I’ll tell at another time. For now, suffice it to say that over these last two decades, as I’ve explored my creativity, I have discovered aspects of myself I would never otherwise have gotten to know.

Journaling is yet another practice which I do daily, and it grew out doing of The Artist’s Way. Through journaling I often uncover inner dynamics, priorities, assumptions and motivations that I was previously unaware of.

Another powerful way to cultivate self-knowledge is closely tied to meditation: non-judgmental witnessing . By non-judgmental witnessing I mean simply noticing the thoughts, feelings and reactions that are arising in me in any given moment and — this is key — witnessing them without judging them as good or bad. Coming to know yourself, in the end, can lead to personal transformation, but in my experience that transformation comes only through acceptance and love, not through self-condemnation or striving.

The Spiritual Life Is Life

I suspect many of us think of our spiritual life as the time that we set apart from our daily activities to focus on our spirituality, the time we spend sitting on the meditation cushion, or in the pew. But I see the spiritual life as a life that is centered in spiritual awareness , and the time on the cushion or in the pew is just the beginning. That is simply the time when we let ourselves be reminded of who we are, where we came from, and why we’re here. Unless we take that awareness into the rest of our lives, it serves little purpose.

Likewise, you can have spiritual teachers by the dozens, but unless you implement the teachings for yourself they won’t do a thing for you. You have to care deeply enough about your own freedom and growth that you’re willing to do what is necessary to water the seeds of your spiritual awareness, the way you would water the flowers in your flowerbed. Nobody can do it for you.

Knowing yourself, of course, is a major theme in Buddhism, and, as the Buddha taught, the more you come to know yourself the more you will realize there is no self. After peeling back the layers of constructed identity, eventually we discover all that’s left is Mystery — a Mystery we are part of.

Like what you read?

Click the circle.

Collage by Patricia Pearce. All rights reserved.

July 19, 2013 at 4:08 PM

Sometimes awakening can be like a heart attack. The initial experience is devastating, frightening and life changing. I found myself living, for most of my life, in a fantasy. It was so much easier to retreat into this fantasy than deal with the conflicts and anxieties and even joys of reality. For me, at least recently, journaling has helped. I like to write by hand, pen to paper. It’s slower and allows for more contemplation. Katie Aikens recently reflected on St. Paul’s comments of the life of the flesh and the life of the spirit. I think that the life of the flesh, which involves thinking that one has unbridled freedom to the point of chaos, involves this selfish fantasy. To know oneself leads to having compassion for others. Then freedom is bounded by that compassion. Knowing oneself leads to genuine humility and acceptance. Isn’t it ironic that compassion, humility and acceptance lead to freedom? The terms seem so opposite.

July 20, 2013 at 6:18 PM

Richard, so many things in what you shared really jumped out at me. The analogy of the heart attack is so insightful. The disorientation that comes can be pretty extreme and it’s helpful (though rare) to have others who can hold space for you as you undergo the transition.

Your comments about the tendency toward fantasy brought to mind something from one of my newest favorite books, Improv Wisdom , where the author, Patricia Ryan Madson, talks about the importance of “facing the facts.” She says, “The most consistent road to unhappiness I know is turning a blind eye to reality.” (p. 78) She maintains that if we want to respond to life creatively we must first honestly face reality.

I also really appreciated what you shared about your journaling practice. I have also found keeping a journal to be so helpful. It’s a way for me to come to clarity about issues that might otherwise just keep spinning around and around in my head, and I learn so much about myself along the way. Like you, I write in my journal by hand even though most of my other writing I do at the keyboard. There is something about setting pen to paper that makes it a different experience for me. More raw. More free-flowing.

What you said about self-knowledge leading to compassion rung so true for me. I, too, find that the more I come to know all the various aspects of myself (some of which I’d rather just go away) the more understanding I am of other people in their struggles. I absolutely loved your insight about how that compassion then serves as a boundary to reckless “freedom”. So beautifully put! Thank you!

I’d love to hear more about the “heart attack” experience(s) if you’re willing to share, either here or by emailing me at ppearce(at)patriciapearce.com.

Peace, Patricia

September 11, 2013 at 12:19 AM

Patricia, you often express in words EXACTLY how I feel. Indeed, the spiritual life IS life. One way that helps me is mindfulness. Of course, the goal is to be mindful all the time, but I find great joy and meaning in taking minutes in my too busy day to, for example, taste all the flavors available in one bite of something, or to feel how utterly luxurious my cat’s fur is. Peace and blessings.

September 11, 2013 at 10:51 AM

Amen! It’s in those moments of mindfulness that life leaps into Technicolor. I find often that if I’m doing a review of my day before going to bed it’s those moments of complete lucidity and presence that were the most precious of the entire day. And they usually happen when I’m fully attentive to simple things. It turns out those “simple” things are packed with awe.

January 14, 2021 at 1:16 AM

My name is kifayat ullah man too and my mothers name is nishata I’m a muslim. When ever I’m closing my eyes I’m seeing all over world on my sight and when I open my eyes I can not see any thing and some time im going dreaming my self what ever have been happing on my sight of eye that is going true on my present day Or too many present months

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

“i” and “me”: the self in the context of consciousness.

- Cognition and Philosophy Lab, Department of Philosophy, Monash University, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

James (1890) distinguished two understandings of the self, the self as “Me” and the self as “I”. This distinction has recently regained popularity in cognitive science, especially in the context of experimental studies on the underpinnings of the phenomenal self. The goal of this paper is to take a step back from cognitive science and attempt to precisely distinguish between “Me” and “I” in the context of consciousness. This distinction was originally based on the idea that the former (“Me”) corresponds to the self as an object of experience (self as object), while the latter (“I”) reflects the self as a subject of experience (self as subject). I will argue that in most of the cases (arguably all) this distinction maps onto the distinction between the phenomenal self (reflecting self-related content of consciousness) and the metaphysical self (representing the problem of subjectivity of all conscious experience), and as such these two issues should be investigated separately using fundamentally different methodologies. Moreover, by referring to Metzinger’s (2018) theory of phenomenal self-models, I will argue that what is usually investigated as the phenomenal-“I” [following understanding of self-as-subject introduced by Wittgenstein (1958) ] can be interpreted as object, rather than subject of experience, and as such can be understood as an element of the hierarchical structure of the phenomenal self-model. This understanding relates to recent predictive coding and free energy theories of the self and bodily self discussed in cognitive neuroscience and philosophy.

Introduction

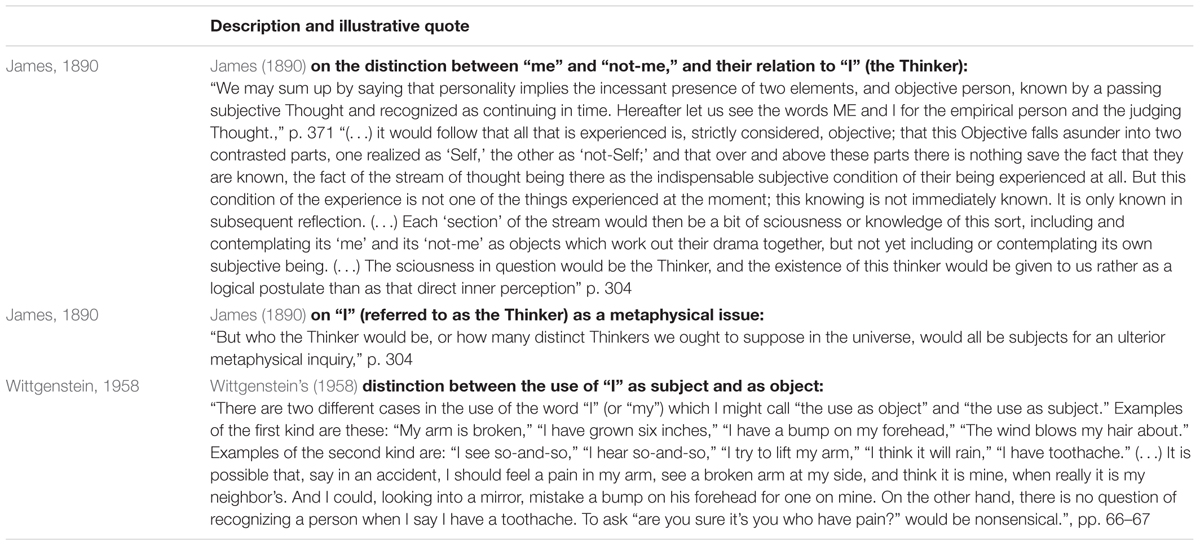

Almost 130 years ago, James (1890) introduced the distinction between “Me” and “I” (see Table 1 for illustrative quotes) to the debate about the self. The former term refers to understanding of the self as an object of experience, while the latter to the self as a subject of experience 1 . This distinction, in different forms, has recently regained popularity in cognitive science (e.g., Christoff et al., 2011 ; Liang, 2014 ; Sui and Gu, 2017 ; Truong and Todd, 2017 ) and provides a useful tool for clarifying what one means when one speaks about the self. However, its exact meaning varies in cognitive science, especially in regard to what one understands as the self as subject, or “I.”

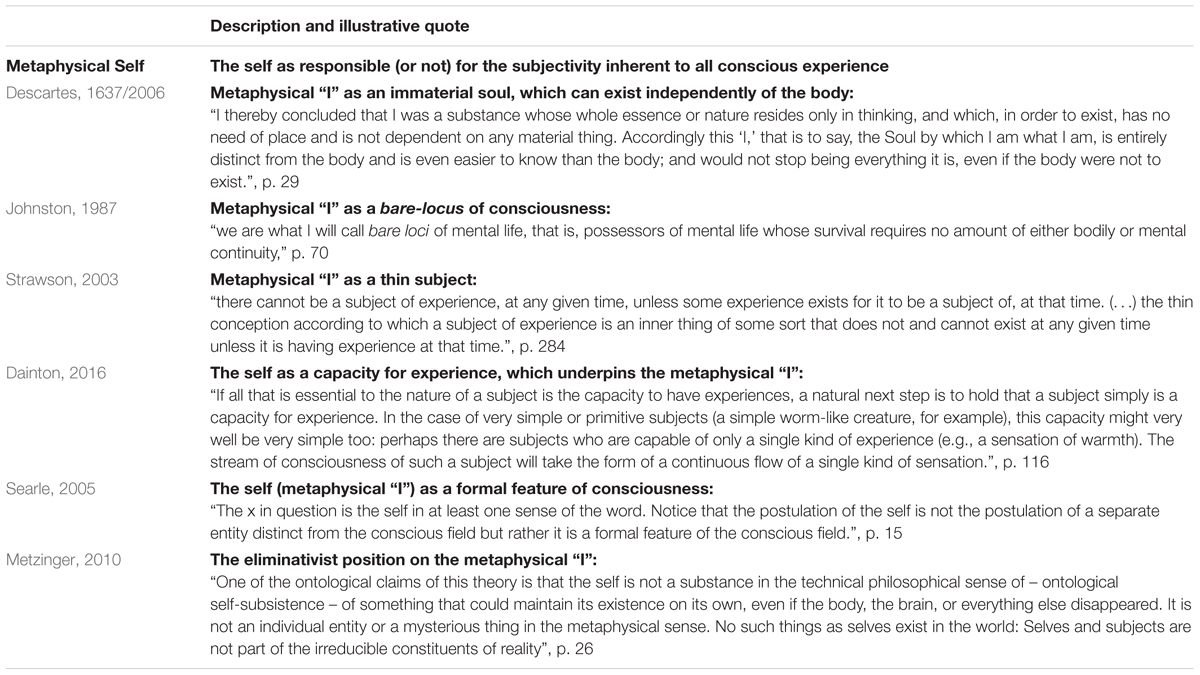

TABLE 1. Quotes from James (1890) illustrating the distinction between self-as-object (“Me”) and self-as-subject (“I”) and a quote from Wittgenstein (1958) illustrating his distinction between the use of “I” as object and as subject.

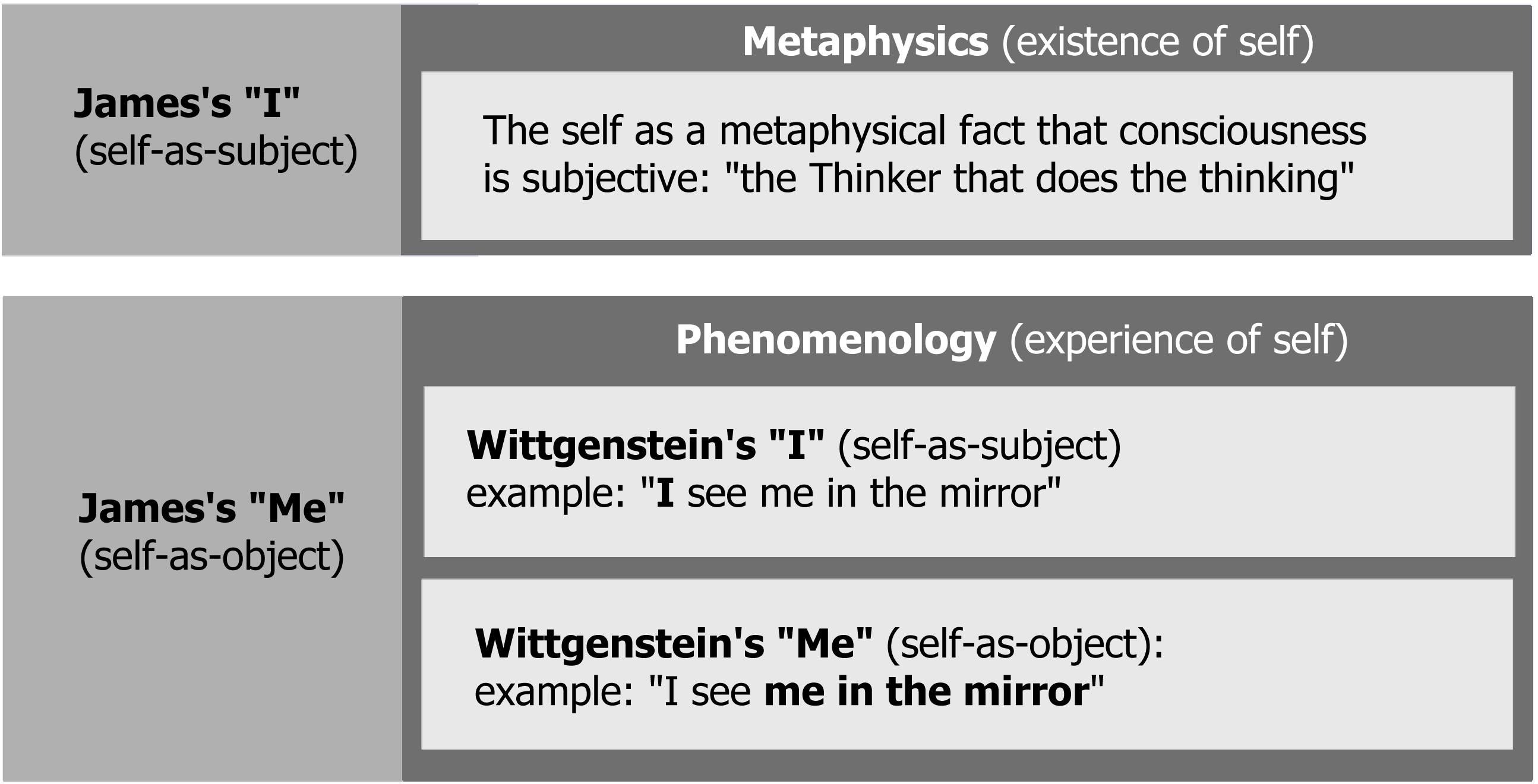

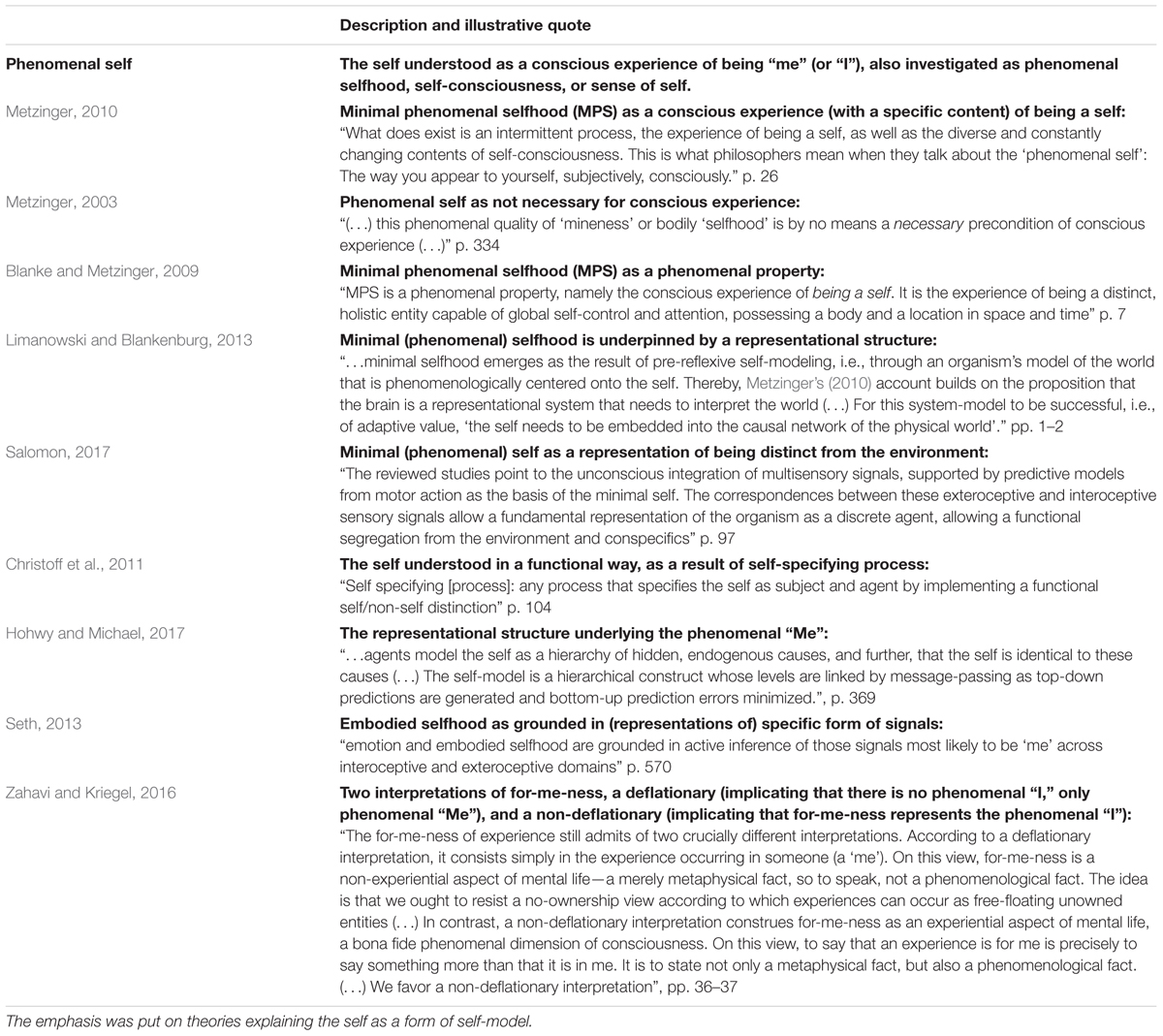

The goal of this paper is to take a step back from cognitive science and take a closer look at the conceptual distinction between “Me” and “I” in the context of consciousness. I will suggest, following James (1890) and in opposition to the tradition started by Wittgenstein (1958) , that in this context “Me” (i.e., the self as object) reflects the phenomenology of selfhood, and corresponds to what is also known as sense of self, self-consciousness, or phenomenal selfhood (e.g., Blanke and Metzinger, 2009 ; Blanke, 2012 ; Dainton, 2016 ). On the other hand, the ultimate meaning of “I” (i.e., the self as subject) is rooted in metaphysics of subjectivity, and refers to the question: why is all conscious experience subjective and who/what is the subject of conscious experience? I will argue that these two theoretical problems, i.e., phenomenology of selfhood and metaphysics of subjectivity, are in principle independent issues and should not be confused. However, cognitive science usually follows the Wittgensteinian tradition 2 by understanding the self-as-subject, or “I,” as a phenomenological, rather than metaphysical problem [Figure 1 illustrates the difference between James (1890) and Wittgenstein’s (1958) approach to the self]. By following Metzinger’s (2003 , 2010 ) framework of phenomenal self-models, and in agreement with a reductionist approach to the phenomenal “I” 3 ( Prinz, 2012 ), I will argue that what is typically investigated in cognitive science as the phenomenal “I” [or the Wittgenstein’s (1958) self-as-subject] can be understood as just a higher-order component of the self-model reflecting the phenomenal “Me.” Table 2 presents some of crucial claims of the theory of self-models, together with concise references to other theories of the self-as-object discussed in this paper.

FIGURE 1. An illustration of James (1890) and Wittgenstein’s (1958) distinctions between self-as-object (“Me”) and self-as-subject (“I”). In the original formulation, James’ (1890) “Me” includes also physical objects and people (material and social “Me”) – they were not included in the picture, because they are not directly related to consciousness.

TABLE 2. Examples of theories of the self-as-object (“Me”) in the context of consciousness, as theories of the phenomenal self, with representative quotes illustrating each position.

“Me” As An Object Of Experience: Phenomenology Of Self-Consciousness

The words ME, then, and SELF, so far as they arouse feeling and connote emotional worth, are OBJECTIVE designations, meaning ALL THE THINGS which have the power to produce in a stream of consciousness excitement of a certain particular sort ( James, 1890 , p. 319, emphasis in original).

James (1890) chose the word “Me” to refer to self-as-object. What does it mean? In James’ (1890) view, it reflects “all the things” which have the power to produce “excitement of a certain particular sort.” This certain kind of excitement is nothing more than some form of experiential quality of me-ness, mine-ness, or similar - understood in a folk-theoretical way (this is an important point, because these terms have recently acquired technical meanings in philosophy, e.g., Zahavi, 2014 ; Guillot, 2017 ). What are “all the things”? The classic formulation suggests that James (1890) meant physical objects and cultural artifacts (material self), human beings (social self), and mental processes and content (spiritual self). These are all valid categories of self-as-object, however, for the purpose of this paper I will limit the scope of further discussion only to “objects” which are relevant when speaking about consciousness. Therefore, rather than speaking about, for example, my car or my body, I will discuss only their conscious representations. This limits the scope of self-as-object to one category of “things” – conscious mental content.

Let us now reformulate James’ (1890) idea in more contemporary terms and define “Me” as the totality of all content of consciousness that is experienced as self-related. Content of consciousness is meant here in a similar way to Chalmers (1996) , who begins “ The conscious mind ” by providing a list of different kinds of conscious content. He delivers an extensive (without claiming that exhaustive) collection of types of experiences, which includes the following 4 : visual; auditory; tactile; olfactory; experiences of hot and cold; pain; taste; other bodily experiences coming from proprioception, vestibular sense, and interoception (e.g., headache, hunger, orgasm); mental imagery; conscious thought; emotions. Chalmers (1996) also includes several other, which, however, reflect states of consciousness and not necessarily content per se , such as dreams, arousal, fatigue, intoxication, and altered states of consciousness induced by psychoactive substances. What is common to all of the types of experience from the first list (conscious contents) is the fact that they are all, speaking in James’ (1890) terms, “objects” in a stream of consciousness: “all these things are objects, properly so called, to the subject that does the thinking” (p. 325).

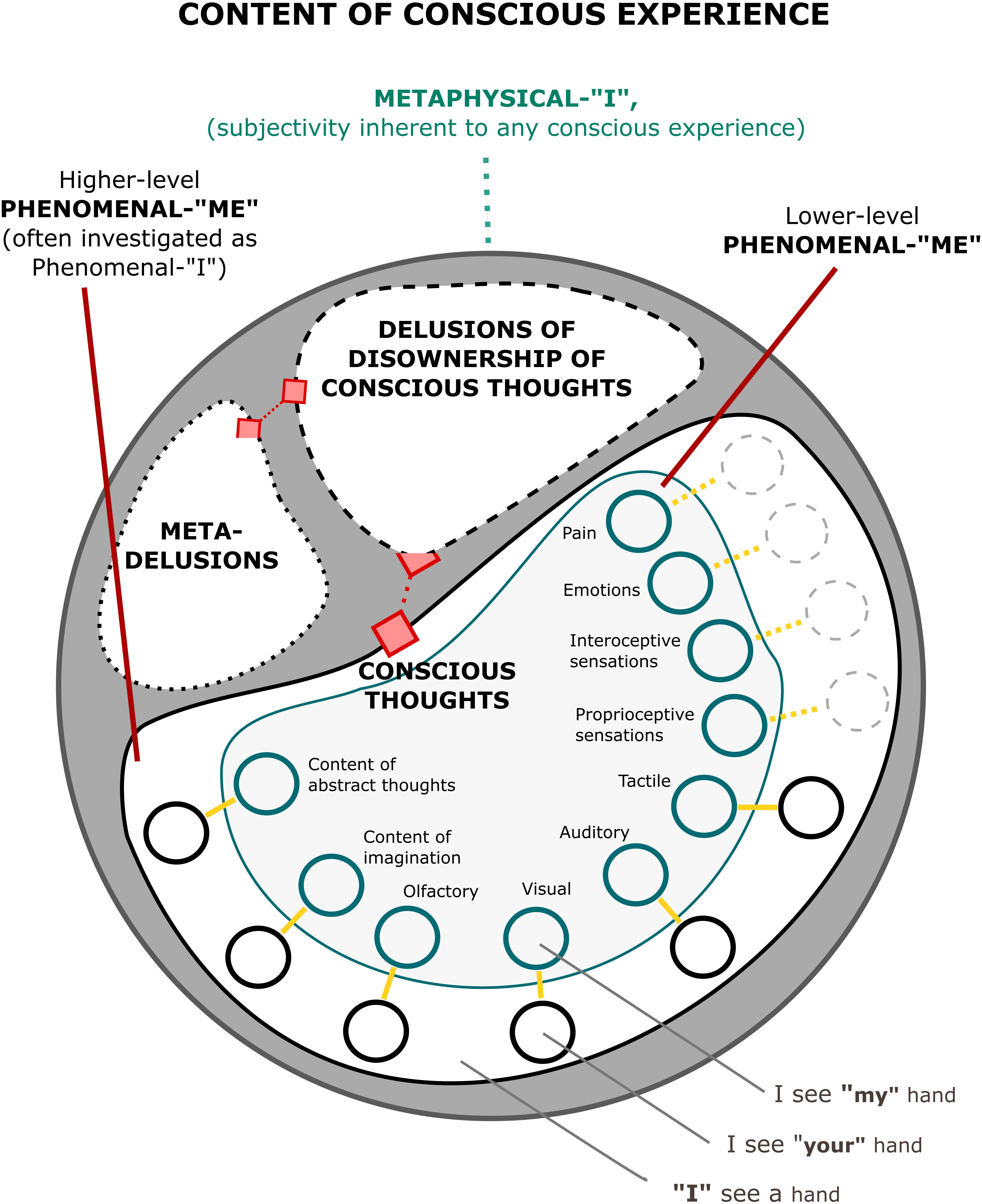

The self understood as “Me” can be understood as a subset of a set of all these possible experiences. This subset is characterized by self-relatedness (Figure 2 ). It can be illustrated with sensory experiences. For example, in the visual domain, I experience an image of my face as different from another person’s face. Hence, while the image of my face belongs to “Me,” the image of someone else does not (although it can be experimentally manipulated, Tsakiris, 2008 ; Payne et al., 2017 ; Woźniak et al., 2018 ). The same can be said about my voice and sounds caused by me (as opposed to voices of other people), and about my smell. We also experience self-touch as different from touching or being touched by a different person ( Weiskrantz et al., 1971 ; Blakemore et al., 1998 ; Schutz-Bosbach et al., 2009 ). There is even evidence that we process our possessions differently ( Kim and Johnson, 2014 ; Constable et al., 2018 ). This was anticipated by James’ (1890) notion of the material “Me,” and is typically regarded as reflecting one’s extended self ( Kim and Johnson, 2014 ). In all of these cases, we can divide sensory experiences into the ones which do relate to the self and the ones which do not. The same can be said about the contents of thoughts and feelings, which can be either about “Me” or about something/someone else.

FIGURE 2. A simplified representation of a structure of phenomenal content including the metaphysical “I,” the phenomenal “Me,” and the phenomenal “I,” which can be understood (see in text) as a higher-level element of the phenomenal “Me.” Each pair of nodes connected with a yellow line represents one type of content of consciousness, with indigo nodes corresponding to self-related content, and black nodes corresponding to non-self-related content. In some cases (e.g., pain, emotions, interoceptive, and proprioceptive sensations), the black nodes are lighter and drawn with a dashed line (the same applies to links), to indicate that in normal circumstances one does not experiences these sensations as representing another person (although it is possible in thought experiments and pathologies). Multisensory/multimodal interactions have been omitted for the sake of clarity. All of the nodes compose the set of conscious thoughts, which can be formulated as “I experience X.” In normal circumstances, one does not deny ownership over these thoughts, however, in thought experiments, and in some cases of psychosis, one may experience that even such thoughts cease to feel as one’s own. This situation is represented by the shape with a dashed outline. Moreover, in special cases one can form meta-delusions, i.e., delusions about delusions – thoughts that my thoughts about other thoughts are not my thoughts (see text for description).

Characterizing self-as-object as a subset of conscious experiences specifies the building blocks of “Me” (which are contents of consciousness) and provides a guiding principle for distinguishing between self and non-self (self-relatedness). However, it is important to note two things. First, the distinction between self and non-self is often a matter of scale rather than a binary classification, and therefore self-relatedness may be better conceptualized as the strength of the relation with the self. It can be illustrated with an example of the “Inclusion of Other in Self” scale ( Aron et al., 1992 ). This scale asks to estimate to what extent another person feels related to one’s self, by choosing among a series of pairs of more-to-less overlapping circles representing the self and another person (e.g., a partner). The degree of overlap between the chosen pair of circles represents the degree of self-relatedness. Treating self-relatedness as a matter of scale adds an additional level of complexity to the analysis, and results in speaking about the extent to which a given content of consciousness represents self, rather than whether it simply does it or not. This does not, however, change the main point of the argument that we can classify all conscious contents according to whether (or to what extent, in that case) they are self-related. For the sake of clarity, I will continue to speak using the language of binary classification, but it should be kept in mind that it is an arbitrary simplification. The second point is that this approach to “Me” allows one to flexibly discuss subcategories of the self by imposing additional constraints on the type of conscious content that is taken into account, as well as the nature of self-relatedness (e.g., whether it is ownership of, agency over, authorship, etc.). For example, by limiting ourselves to discussing conscious content representing one’s body one can speak about the bodily self, and by imposing limits to conscious experience of one’s possessions one can speak about one’s extended self.

Keeping these reservations in mind two objections can be raised to the approach to “Me” introduced here. The first one is as follows:

(1) Speaking about the self/other distinction does not make sense in regard to experiences which are always “mine,” such as prioprioception or interoception. This special status may suggest that these modalities underpin the self as “I,” i.e., the subject of experience.

This idea is present in theoretical proposals postulating that subjectivity emerges based on (representations of) sensorimotor ( Gallagher, 2000 ; Christoff et al., 2011 ; Blanke et al., 2015 ) or interoceptive signals ( Damasio, 1999 ; Craig, 2010 ; Seth et al., 2011 ; Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014 ; Salomon, 2017 ). There are two answers to this objection. First, the fact that this kind of experience (this kind of content of consciousness) is always felt as “my” experience simply means that all proprioceptive, interoceptive, pain experiences, etc., are as a matter of fact parts of “Me.” They are self-related contents of consciousness and hence naturally qualify as self-as-object. Furthermore, there is no principled reason why the fact that we normally do not experience them as belonging to someone else should transform them from objects of experience (content) into a subject of experience. Their special status may cause these experiences to be perceived as more central aspects of the self than experiences in other modalities, but there is no reason to think that it should change them from something that we experience into the self as an experiencer. Second, even the special status of these sensations can be called into question. It is possible to imagine a situation in which one experiences these kinds of sensations from an organ or a body which does not belong to her or him. We can imagine that with enough training one will learn to distinguish between proprioceptive signals coming from one’s body and those coming from another person’s (or artificial) body. If this is possible, then one may develop a phenomenal distinction between “my” versus “other’s” proprioceptive and interoceptive experiences (for example), and in this case the same rules of classification into phenomenal “Me” and phenomenal “not-Me” will apply as to other sensory modalities. This scenario is not realistic at the current point of technological development, but there are clinical examples which indirectly suggest that it may be possible. For example, people who underwent transplantation of an organ sometimes experience rejection of a transplant. Importantly, patients whose organisms reject an organ also more often experience psychological rejection of that transplant ( Látos et al., 2016 ). Moreover, there are rare cases in which patients following a successful surgery report that they perceive transplanted organs as foreign objects in themselves ( Goetzmann et al., 2009 ). In this case, affected people report experiencing a form of disownership of the implanted organ, suggesting that they may experience interoceptive signals coming from that transplant as having a phenomenal quality of being “not-mine,” leading to similar phenomenal quality as the one postulated in the before-mentioned thought experiment. Another example of a situation in which self-relatedness of interoception may be disrupted may be found in conjoint twins. In some variants of this developmental disorder (e.g., parapagus, dicephalus, thoracopagus) brains of two separate twins share some of the internal organs (and limbs), while others are duplicated and possessed by each twin individually ( Spencer, 2000 ; Kaufman, 2004 ). This provides an inverted situation to the one described in our hypothetical scenario – rather than two pieces of the same organ being “wired” to one person, the same organ (e.g., a heart, liver, stomach) is shared by two individuals. As such it may be simultaneously under control of two autonomous nervous systems. This situation raises challenging questions for theories which postulate that the root of self-as-subject lies in interoception. For example, if conjoint twins share the majority of internal organs, but possess mostly independent nervous systems, like dicephalus conjoint twins, then does it mean that they share the neural subjective frame ( Park and Tallon-Baudry, 2014 )? If the answer is yes, then does it mean that they share it numerically (both twins have one and the same subjective frame), or only qualitatively (their subjective frames are similar to the point of being identical, but they are distinct frames)? However, if interoception is just a part of “Me” then the answer becomes simple – the experiences can be only qualitatively identical, because they are experienced by two independent subjects.

All of these examples challenge the assumption that sensori-motor and interoceptive experiences are necessarily self-related and, as a consequence, that they can form the basis of self-as-subject. For this reason, it seems that signals coming from these modalities are more appropriate to underlie the phenomenal “Me,” for example in a form of background self-experience, or “phenomenal background” ( Dainton, 2008 , 2016 ), rather than the phenomenal “I.”

The second possible objection to the view of self-as-object described in this section is the following one:

(2) My thoughts and feelings may have different objects, but they are always my thoughts and feelings. Therefore, their object may be either “me” or “other,” but their subject is always “I.” As a consequence, even though my thoughts and feelings constitute contents of my consciousness, they underlie the phenomenal “I” and not the phenomenal “Me.”

It seems to be conceptually misguided to speak about one’s thoughts and feelings as belonging to someone else. This intuition motivated Wittgenstein (1958) to write: “there is no question of recognizing a person when I say I have toothache. To ask ‘are you sure it is you who have pains?’ “would be nonsensical” ( Wittgenstein, 1958 ). In the Blue Book, he introduced the distinction between the use of “I” as object and as subject (see Table 1 for a full relevant quote) and suggested that while we can be wrong about the former, making a mistake about the latter is not possible. This idea was further developed by Shoemaker (1968) who introduced an arguably conceptual truth that we are immune to error through misidentification relative to the first-person pronoun, or IEM in short. For example, when I say “I see a photo of my face in front of me” I may be mistaken about the fact that it is my face (because, e.g., it is a photo of my identical twin), but I cannot be mistaken that it is me who is looking at it. One way to read IEM is that it postulates that I can be mistaken about self-as-object, but I cannot be mistaken about self-as-subject. If this is correct then there is a radical distinction between these two types of self that provides a strong argument to individuate them. From that point, one may argue that IEM provides a decisive argument to distinguish between phenomenal “I” (self-as-subject) and phenomenal “Me” (self-as-object).

Before endorsing this conclusion, let us take a small step back. It is important to note that in the famous passage from the Blue Book Wittgenstein (1958) did not write about two distinct types of self. Instead, he wrote about two ways of using the word “I” (or “my”). As such, he was more concerned with issues in philosophy of language than philosophy of mind. Therefore, a natural question arises – to what extent does this linguistic distinction map onto a substantial distinction between two different entities (types of self)? On the face of it, it seems that there is an important difference between these two uses of self-referential words, which can be mapped onto the experience of being a self-as-subject and the experience of being a self-as-object (or, for example, the distinction between bodily ownership and thought authorship, as suggested by Liang, 2014 ). However, I will argue that there are reasons to believe that the phenomenal “I,” i.e., the experience of being a self-as-subject may be better conceptualized as a higher-order phenomenal “Me” – a higher-level self-as-object.

Psychiatric practice provides cases of people, typically suffering from schizophrenia, who describe experiences of dispossession of thoughts, known as delusions of thought insertion ( Young, 2008 ; Bortolotti and Broome, 2009 ; Martin and Pacherie, 2013 ). According to the standard account, the phenomenon of thought insertion does not represent a disruption of sense of ownership over one’s thoughts, but only loss of sense of agency over them. However, the standard account has been criticized in recent years by theorists arguing that thought insertion indeed represents loss of sense of ownership ( Metzinger, 2003 ; Billon, 2013 ; Guillot, 2017 ; López-Silva, 2017 ). One of the main arguments against the standard view is that it runs into serious problems when attempting to explain obsessive intrusive thoughts in clinical population and spontaneous thoughts in healthy people. In both cases, subjects report lack of agency over thoughts, although they never claim lack of ownership over them, i.e., that these are not their thoughts. However, if the standard account is correct, obsessive thoughts should be experienced as belonging to someone else. The fact that they are not suggests that something else must be disrupted in delusions of thought insertion, i.e., sense of ownership 5 over them. If one can lose sense of ownership over one’s thoughts then it has important implications, because then one becomes capable of experiencing one’s thoughts “as someone else’s,” or at least “as not-mine.” However, when I experience my thoughts as not-mine I do it because I’ve taken a stance towards my thoughts, which treats them as an object of deliberation. In other words, I must have “objectified” them to experience that they have a quality of “feeling as if they are not mine.” Consequently, if I experience them as objects of experience, then they cannot form part of my self as subject of experience, because these two categories are mutually exclusive. Therefore, what seemed to constitute a phenomenal “I” turns out to be a part of thephenomenal “Me.”

If my thoughts do not constitute the “I” then how do they fit into the structure of “Me”? Previously, I asserted that thoughts with self-related content constitute “Me,” while thoughts with non-self related content do not. However, just now I argued in favor of the claim that all thoughts (including the ones with non-self-related content) that are experienced as “mine” belong to “Me.” How can one resolve this contradiction?

A way to address this reservation can be found in Metzinger’s (2003 ; 2010 ) self-model theory. Metzinger (2003 , 2010 ) argues that the experience of the self can be understood as underpinned by representational self-models. These self-models, however, are embedded in the hierarchical representational structure, as illustrated by an account of ego dissolution by Letheby and Gerrans (2017) :

Savage suggests that on LSD “[changes] in body ego feeling usually precede changes in mental ego feeling and sometimes are the only changes” (1955, 11), (…) This common temporal sequence, from blurring of body boundaries and loss of sense of ownership for body parts through to later loss of sense of ownership for thoughts, speaks further to the hierarchical architecture of the self-model. ( Letheby and Gerrans, 2017 , p. 8)

If self-models underlying the experience of self-as-object (“Me”) are hierarchical, then the apparent contradiction may be easily explained by the fact that when speaking about the content of thoughts and the thoughts themselves we are addressing self-models at two distinct levels. At the lower level we can distinguish between thoughts with self-related content and other-related content, while on the higher level we can distinguish between thoughts that feel “mine” as opposed to thoughts that are not experienced as “mine.” As a result, this thinking phenomenal “I” experienced in feeling of ownership over one’s thoughts may be conceived as just a higher-order level of Jamesian “Me.” As such, one may claim that there is no such thing as a phenomenal “I,” just multilevel phenomenal “Me.” However, an objection can be raised here. One may claim that even though a person with schizophrenic delusions experiences her thoughts as someone else’s (a demon’s or some malicious puppet master’s), she can still claim that:

Yes, “I” experience my thoughts as not mine, but as demon’s.” My thoughts feel as “not-mine,” however, it’s still me (or: “I”) who thinks of them as “not-mine.”

As such, one escapes “objectification” of “I” into “Me” by postulating a higher-level phenomenal-“I.” However, let us keep in mind that the thought written above constitutes a valid thought by itself. As such, this thought is vulnerable to the theoretical possibility that it turns into a delusion itself, once a psychotic person forms a meta-delusion (delusion about delusion). In this case, one may begin to experience that: “I” (I 1 ) experience that the “fake I” (I 2 ), who is a nasty pink demon, experiences my thoughts as not mine but as someone else’s (e.g., as nasty green demon’s). In this case, I may claim that the real phenomenal “I” is I 1 , since it is at the top of the hierarchy. However, one may repeat the operation of forming meta-delusions ad infinitum (as may happen in psychosis or drug-induced psychedelic states) effectively transforming each phenomenal “I” into another “fake-I” (and consequently making it a part of “Me”).

The possibility of meta-delusions illustrates that the phenomenal “I” understood as subjective thoughts is permanently vulnerable to the threat of losing the apparent subjective character and becoming an object of experience. As such it seems to be a poor choice for the locus of subjectivity, since it needs to be constantly “on the run” from becoming treated as an object of experience, not only in people with psychosis, but also in all psychologically healthy individuals if they decide to reflect on their thoughts. Therefore, it seems more likely that the thoughts themselves cannot constitute the subject of experience. However, even in case of meta-delusions there seems to be a stable deeper-level subjectivity, let us call it the deep “I,” which is preserved, at least until one loses consciousness. After all, a person who experiences meta-delusions would be constantly (painfully) aware of the process, and often would even report it afterwards. This deep “I” cannot be a special form of content in the stream of consciousness, because otherwise it would be vulnerable to becoming a part of “Me.” Therefore, it must be something different.

There seem to be two places where one can look for this deep “I”: in the domain of phenomenology or metaphysics. The first approach has been taken by ( Zahavi and Kriegel, 2016 ) who argue that “all conscious states’ phenomenal character involves for-me-ness as an experiential constituent.” It means that even if we rule out everything else (e.g., bodily experiences, conscious thoughts), we are still left with some form of irreducible phenomenal self-experience. This for-me-ness is not a specific content of consciousness, but rather “refers to the distinct manner, or how , of experiencing” ( Zahavi, 2014 ).

This approach, however, may seem inflationary and not satisfying (e.g., Dainton, 2016 ). One reason for this is that it introduces an additional phenomenal dimension, which may lead to uncomfortable consequences. For example, a question arises whether for-me-ness can ever be lost or replaced with the “ how of experiencing” of another person. For example, can I experience my sister’s for-me-ness in my stream of consciousness? If yes, then how is for-me-ness different from any other content of consciousness? And if the answer is no, then how is it possible to distil the phenomenology of for-me-ness from the metaphysical fact that a given stream of consciousness is always experienced by this and not other subject?

An alternative approach to the problem of the deep “I” is to reject that the subject of experience, the “I,” is present in phenomenology (like Hume, 1739/2000 ; Prinz, 2012 ; Dainton, 2016 ), and look for it somewhere else, in the domain of metaphysics. Although James (1890) did not explicitly formulate the distinction between “Me” and “I” as the distinction between the phenomenal and the metaphysical self, he hinted at it at several points, for example when he concluded the Chapter on the self with the following fragment: “(...) a postulate, an assertion that there must be a knower correlative to all this known ; and the problem who that knower is would have become a metaphysical problem” ( James, 1890 , p. 401).

“I” As A Subject Of Experience: Metaphysics Of Subjectivity

Thoughts which we actually know to exist do not fly about loose, but seem each to belong to some one thinker and not to another ( James, 1890 , pp. 330–331).

Let us assume that phenomenal consciousness exists in nature, and that it is a part of the reality we live in. The problem of “I” emerges once we realize that one of the fundamental characteristics of phenomenal consciousness is that it is always subjective, that there always seems to be some subject of experience. It seems mistaken to conceive of consciousness which do “fly about loose,” devoid of subjective character, devoid of being someone’s or something’s consciousness. Moreover, it seems that subjectivity may be one of the fundamental inherent properties of conscious experience (similar notions can be found in: Berkeley, 1713/2012 ; Strawson, 2003 ; Searle, 2005 ; Dainton, 2016 ). It seems highly unlikely, if not self-contradictory, that there exists something like an objective conscious experience of “what it is like to be a bat” ( Nagel, 1974 ), which is not subjective in any way. This leads to the metaphysical problem of the self: why is all conscious experience subjective, and what or who is the subject of this experience? Let us call it the problem of the metaphysical “I,” as contrasted with the problem of the phenomenal “I” (i.e., is there a distinctive experience of being a self as a subject of experience, and if so, then what is this experience?), which we discussed so far.

The existence of the metaphysical “I” does not entail the existence of the phenomenal self. It is possible to imagine a creature that possesses a metaphysical “I,” but does not possess any sense of self. In such a case, the creature would possess consciousness, although it would not experience anything as “me,” nor entertain any thoughts/feelings, etc., as “I.” In other words, it is a possibility that one may not experience self-related content of consciousness, while being a sentient being. One example of such situation may be the experience of a dreamless sleep, which “is characterized by a dissolution of subject-object duality, or (…) by a breakdown of even the most basic form of the self-other distinction” ( Windt, 2015 ). This is a situation which can be regarded as an instance of the state of minimal phenomenal experience – the simplest form of conscious experience possible ( Windt, 2015 ; Metzinger, 2018 ), in which there is no place for even the most rudimentary form of “Me.” Another example may be the phenomenology of systems with grid-like architectures which, according to the integrated information theory (IIT, Tononi et al., 2016 ), possess conscious experience 6 . If IIT is correct, then these systems experience some form of conscious states, which most likely lack any phenomenal distinction between “Me” and “not-Me.” However, because they may possess a stream of conscious experience, and conscious experience is necessarily subjective, there remains a valid question: who or what is the subject of that experience?