Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Return this item for free

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Introducing Communication Research: Paths of Inquiry Fifth Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 1071886630

- ISBN-13 978-1071886632

- Edition Fifth

- Publisher SAGE Publications, Inc

- Publication date May 14, 2024

- Language English

- Dimensions 8 x 0.78 x 10 inches

- Print length 344 pages

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author.

Donald Treadwell earned his master’s degree in communication from Cornell University and his

PhD in communication and rhetoric from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.

He developed and taught communication research classes in classroom and online settings

and also taught courses in organizational communication, public relations, and public relations

writing. He is the coauthor of Public Relations Writing: Principles in Practice (2nd ed., Sage,

He has published and presented research on organizational image, consumer response to

college names, health professionals’ images of AIDS, faculty perceptions of the communication

discipline, and employers’ expectations of newly hired communication graduates. His research

appears in Communication Monographs, Journal of Technical Writing and Communication, Public

Relations Review, Journal of Human Subjectivity, and Criminal Justice Ethics.

He is professor emeritus, Westfield State University, and has international consulting experience

in agricultural extension and health communication.

Product details

- Publisher : SAGE Publications, Inc; Fifth edition (May 14, 2024)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 344 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1071886630

- ISBN-13 : 978-1071886632

- Item Weight : 1.5 pounds

- Dimensions : 8 x 0.78 x 10 inches

About the author

Donald treadwell.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

No customer reviews

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Introducing communication research : paths of inquiry

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station40.cebu on May 25, 2021

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

1.1: What is Communication Research?

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 86039

- Lindsey Jo Hand, Erin Ryan, and Karen Sichler

- Kennesaw State University via GALILEO Open Learning Materials

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

When we consider rhetoric, the study of the art of persuasive speaking, the history of communication research can be traced back to the days of Aristotle. You will learn more about rhetoric in your public speaking and communication theory courses, so we won’t take a deep dive into it here, but the larger point is that humans have been interested in studying communication since 300 B.C. Modern communication research and efforts to define and “model” the process of communication, however, is typically traced back to the early 20th century.

Walter Lippmann’s (1922) book Public Opinion is a seminal piece in the early study of communication. Lippmann’s (1922) focus on communication and democracy might sound familiar to you; his objective was to highlight problems facing democracy by discussing how public opinion consists of “pictures inside people’s heads [that] do not automatically correspond with the world outside” (p. 19). He argued that people’s access to facts are often limited, thus public opinions are often misleading and inaccurate, but yet we still tend to collectively act upon them. John Dewey’s (1927) book The Public and its Problems took a similar view of the communication process, but he had a more optimistic view, “When communication occurs, all natural events are subject to reconsideration and revision; they are re-adapted to meet the requirements of conversation, whether it be public discourse or that preliminary discourse termed thinking” (p. 132). Both Lippmann and Dewey set the stage for future study of communication by highlighting its importance in social life, democracy, and community.

Upon the founding of the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania in 1958, publisher and ambassador Walter Annenberg wrote:

"Every human advancement or reversal can be understood through communication. The right to free communication carries with it responsibility to respect the dignity of others – and this must be recognized as irreversible. Educating students to effectively communicate this message and to be of service to all people is the enduring mission of this school."

The scholars who helped establish the Annenberg School set the stage for the future of teaching and researching communication. Under George Gerbner, the second dean of the school from 1964 until 1989, the school moved communication research beyond either a strict medium (radio, television, speech) or professional training basis to a more theoretical understanding of communication. The mission of the Annenberg School at the University of Pennsylvania is to produce cutting-edge research, sharing the work to help expand the public’s and policy makers’ understanding of communication, educate graduate and undergraduate students to move forward the discipline as well as encourage students to be better consumers of communication.

Fields of Communication

For a comprehensive overview of the fields of communication (and career options for each category) visit https://www.communications-major.com/ . Reading through this list will help you understand the skills required in the communication professions, and you can discover which types of jobs appeal to you the most. Many of these fields overlap. Regardless of what career path you choose, you will need to be a skilled writer and speaker, understand digital technology, and develop the ability to analyze information and think critically. When you determine which path is a good fit for you, choose from one of the four majors in the School of Communication and Media:

Journalism and Emerging Media

( http://chss.kennesaw.edu/socm/programs/bsjem.php )

Whether you are navigating the media-rich culture as a critical thinker, learning to write and produce news and feature stories as a journalist, or are gaining hands-on experience in digital video and audio as a social media expert, Kennesaw State's Journalism and Emerging Media program offers endless possibilities.

Learn the latest industry trends from faculty members who are award-winning professionals, including reporters, editors and international correspondents at the Associated Press, the Atlanta JournalConstitution , CNN, NPR, commercial radio stations and various newspapers. The Journalism and Emerging Media major offers a professionally-focused, marketplace-relevant, and theoretically-rigorous program. It includes courses in news writing, media law, digital media production, sports reporting, investigative reporting, and community-based capstone experience. It encourages students to enroll in a forcredit internship.

Media and Entertainment

( http://chss.kennesaw.edu/socm/programs/bsmes.php )

The Media and Entertainment major invites students to explore the critical ways in which communication and converged media connect with and affect our lives, society, and culture. The program focuses on the forms and effects of media, including radio, film, television, print, and electronic media, and requires that students demonstrate basic digital media production skills. Our students are critically engaged with creative analysis, production, and research into traditional and emerging forms of media. The curriculum emphasizes media history, media institutions, theory and research, production, ethics, policy, management, and technology and their effects on contemporary life.

The program offers both theoretical and applied approaches to the study and production of media. We define “entertainment” as “any media or communication function that is used for entertainment purposes” when considering areas of study. Thus, the field of media and entertainment is very broad and includes everything from film, television, and radio pre-production, production, and post-production; to corporate, government, and non-profit communications and digital media production; to jobs in theater, music, museums, theme parks, sports, travel and tourism, and gaming.

Organizational and Professional Communication

( http://chss.kennesaw.edu/socm/programs/bsopc.php )

Organizational and Professional Communication professionals study the role of communication in increasing corporate productivity and employee satisfaction. KSU is the only Georgia institution offering an undergraduate concentration in Organizational and Professional Communication. Organizational and Professional Communication students learn the skills they need to develop employee training programs, training manuals, and employee handbooks. Students also conduct communication audits at area companies to measure employee satisfaction with company communication practices. Students often intern in corporate human resources or training and development departments.

Public Relations

( http://chss.kennesaw.edu/socm/programs/bspr.php )

The Public Relations major at Kennesaw State University offers a professionally-focused, marketplace-relevant, and theoretically-rigorous academic program for aspiring public relations communicators throughout Metro Atlanta and Northwest Georgia. Kennesaw State is one of only three universities in the state of Georgia to offer a specific major in the ever-evolving discipline of Public Relations. The major offers students a public relations education that includes public relations principles, case study analysis, public relations writing, crisis communication, graphic design for organizational publications, persuasion methods and strategies, and use of social media and other multimedia communication strategies in public relations. Internships and study tours to New York and Atlanta public relations agencies supplement the traditional classroom and online learning settings.

For a list of potential communication-based employers in the state of Georgia, check out this page: https://www.communications-major.com/georgia/

Professional Organizations

In the field of communication research, there are several regional, national, and international professional organizations for educators, students, and communication practitioners. Each organization has a code of ethics, or best practices, for the profession and for training and developing the next generation of researchers and professors. These nonprofit organizations hold conventions/ conferences where communication students and scholars come together to present research, have roundtable discussions, and discuss recent innovations in the field. Typically, these organizations have divisions and interest groups devoted to the various categories of scholarship that fall under the “communication” umbrella. Examples include divisions devoted specifically to journalism, public relations, mass communication and society, communication theory, advertising, health communication, technology, cultural and critical studies, history, law and policy, ethics, gender/women’s studies, entertainment studies, children and media, and communication education.

For a typical yearly conference, the organization puts out a “call for papers” online 3-6 months before the conference, and scholars upload their original research to the website into the division that best fits their research topic. Each paper is then reviewed by peers in that field (typically two or three reviewers) who score the paper on dimensions such as quality of writing, importance of the topic, soundness of methodology, and impact of findings. Papers that gain high scores are then slated for presentation at the conference. Some presentations are done on posters whereas others are orally presented to small groups, typically using a visual aid such as PowerPoint. Presenting at an academic conference is a great way to get feedback from peers in your field before attempting to publish your work in an academic journal. And aside from presenting or attending research sessions, conferences offer an opportunity to connect and network with fellow scholars in your field. Conferences also typically have a “job fair” where representatives from various universities interview prospective new professors for academic positions.

There are several well-known and well-respected professional communication organizations in the United States. The Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC) is one of the largest organizations, holding small regional conferences and one large conference each year. AEJMC has 18 divisions, 10 interest groups, and two commissions (or areas of broad concern that cut across divisional lines): Commission on the Status of Minorities and Commission on the Status of Women. Most divisions and interest groups have their own academic journal (i.e., Journal of Advertising Education , Electronic News , International Communication Research Journal , Mass Communication & Society , etc.,) and AEJMC publishes three scholarly journals: Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly , Journal & Mass Communication Educator , and Journalism & Communication Monographs . More information about AEJMC can be found at www.aejmc.org.

The National Communication Association (NCA) is another large organization, and its annual convention attracts roughly 5,000 attendees. NCA has 48 divisions and six caucuses (Asian/Pacific American; Black; Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer Concerns; Disability; La Raza; and Women’s Caucus). In addition to journalism and mass communication, NCA features research divisions in activism and social justice, argumentation and forensics, ethnography, family communication, group communication, interpersonal communication, nonverbal communication, organizational communication, peace and conflict communication, public address, spiritual communication, and training and development. NCA publishes 11 academic journals: Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies , Communication Education , Communication Monographs , Communication Teacher , Critical Studies in Media Communication , First Amendment Studies , Journal of Applied Communication Research ,Journal of International and Intercultural Communication ,Quarterly Journal of Speech, The Review of Communication ,and Text and Performance Quarterly . More information about NCA can be found at www.natcom.org.

The largest international organization in our field is the International Communication Association (ICA). ICA boasts more than 4,500 members from 80 countries and is officially associated with the United Nations as a non-governmental NGO. They host an annual conference, switching between a US destination and an international destination each year. ICA has 23 divisions and nine interest groups, including divisions in Children, Adolescents and Media; Environmental Communication; Feminist Scholarship; Game Studies; Global Communication and Social Change; Philosophy, Theory and Critique; and Popular Communication in addition to divisions devoted to journalism, PR, and mass communication. ICA publishes six major peer reviewed journals: Journal of Communication, Communication Theory; Human Communication Research; Communication, Culture & Critique; Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication; and The Annals of the International Communication Association (formerly Communication Yearbook). There are also two affiliate journals: Communication & Society (a leading Chinese-language journal in journalism and communication) and Studies in Communication & Media (an open-access journal published by the German Communication Association). More information about ICA can be found at www.icahdq.org.

In addition to national and international professional organizations, there are several regional organizations that hold conferences. In our geographical area, we have the Georgia Communication Association (affiliated with NCA; www.gacomm.org), the Southern States Communication Association which publishes the Southern Communication Journal (also affiliated with NCA; www.ssca.net), and the Eastern Communication Association (ECA) which hosts conferences along the east coast of the US, and publishes Communication Research Reports, Qualitative Research Reports in Communication, and Communication Quarterly (www.ecasite.org). There are also regional meetings of the larger organizations, such as the AEJMC Southeast Colloquium, which is held at a different university in the Southeast each March.

There are also professional organizations associated with specific fields within the communication discipline. The Public Relations Society of America (PRSA; http://prsa.org ) is the largest communication-based professional organization in the US, boasting more than 30,000 members, and has a mission to “make communications professionals smarter, better prepared and more connected through all stages of their career.” They also support the Public Relations Student Society of America (PRSSA; http://prssa.prsa.org ) with university chapters across the US. Kennesaw State’s School of Communication & Media has a PRSSA chapter, so if you’re a PR-Interest student you should check it out: http://www.ksuprssa.org .

Journalists have a professional organization as well: The Society for Professional Journalists (SPJ; www.spj.org). SPJ is the most broad-based journalism organization in the US, dedicated to “encouraging the free practice of journalism and stimulating high standards of ethical behavior.” SPJ was founded in 1909 and currently has roughly 7,500 members. The state of Georgia has an SPJ chapter ( https://spjgeorgia.com/ ) and Kennesaw State has a very active student chapter. You can check them out via their Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/KennesawStateSpj.Interested in journalism and mass communication history? The American Journalism Historians Association (AJHA; https:// ajha.wildapricot.org/) holds a national conference and a Southeast symposium every year and publishes the academic journal American Journalism.

Are you a media production enthusiast? The Broadcast Education Association (BEA; www.beaweb.org) is a great resource. BEA is an international academic media professional organization focused on excellence in media production and career advancement for educators, students, and professionals in the industry. The organization holds a massive annual convention in Las Vegas in April, with over 250 sessions on teaching media courses, collaborative networking events, hands-on technology workshops, and research and creative scholarship, in addition to the Festival of Media Arts. The BEA convention is co-located with the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB) Show, where attendees can learn about (and try!) all of the new media production technology. BEA also publishes the Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, Journal of Radio & Audio Media, Journal of Media Education, and the Electronic Media Research book series.

For scholars interested in film and media studies, The Society for Cinema & Media Studies (SCMS; https://www.cmstudies.org/ ) is dedicated to the scholarly study of film, television, video, and new media. They hold an annual conference where students and teachers of film and media studies present research and attend networking events. SCMS also publishes the peer-reviewed academic publication Cinema Journal, focusing on digital media, sound studies, visual culture, video game studies, fan studies, and avant-garde/experimental film and media practices.

Or perhaps you’re interested in health communication? The American Public Health Association has a Health Communication working group ( https://www.apha.org/apha-communities/ member-sections/public-health-education-and-health-promotion/who-we-are/hcwg) and the National Public Health Information Coalition (NPHIC) partners with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to host a national conference on health communication, media, and marketing ( https://www.cdc.gov/nchcmm/index.html ).

Are you an organizational and professional communication scholar? Try the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM; www.shrm.org). They host an annual conference with nearly 200 sessions in six categories: business & HR strategy, HR compliance, global HR, professional development, talent management, and total rewards. They also host conferences on diversity & inclusion, employment law & legislation, leadership development, and recruitment & talent management. There is a local Atlanta chapter here: https://www.shrmatlanta.org/ default.aspx. Another great resource is the Association for Talent Development (formerly “training & development) or ATD (www.td.org). They host conferences in the US and abroad as well as training workshops called “LearnNow” on topics such as game design for instruction, employee engagement, and getting started with augmented reality and virtual reality.

Dewey, J. (1927). The public and its problems. New York: Holt.

Lippmann, W. (1922). Public opinion . New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company.

"In much of society, research means to investigate something you do not know or understand. ” -Neil Armstrong

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 08 May 2024

Exploring the dynamics of consumer engagement in social media influencer marketing: from the self-determination theory perspective

- Chenyu Gu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6059-0573 1 &

- Qiuting Duan 2

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 11 , Article number: 587 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

340 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Business and management

- Cultural and media studies

Influencer advertising has emerged as an integral part of social media marketing. Within this realm, consumer engagement is a critical indicator for gauging the impact of influencer advertisements, as it encompasses the proactive involvement of consumers in spreading advertisements and creating value. Therefore, investigating the mechanisms behind consumer engagement holds significant relevance for formulating effective influencer advertising strategies. The current study, grounded in self-determination theory and employing a stimulus-organism-response framework, constructs a general model to assess the impact of influencer factors, advertisement information, and social factors on consumer engagement. Analyzing data from 522 samples using structural equation modeling, the findings reveal: (1) Social media influencers are effective at generating initial online traffic but have limited influence on deeper levels of consumer engagement, cautioning advertisers against overestimating their impact; (2) The essence of higher-level engagement lies in the ad information factor, affirming that in the new media era, content remains ‘king’; (3) Interpersonal factors should also be given importance, as influencing the surrounding social groups of consumers is one of the effective ways to enhance the impact of advertising. Theoretically, current research broadens the scope of both social media and advertising effectiveness studies, forming a bridge between influencer marketing and consumer engagement. Practically, the findings offer macro-level strategic insights for influencer marketing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Exploring the effects of audience and strategies used by beauty vloggers on behavioural intention towards endorsed brands

COBRAs and virality: viral campaign values on consumer behaviour

Exploring the impact of beauty vloggers’ credible attributes, parasocial interaction, and trust on consumer purchase intention in influencer marketing

Introduction.

Recent studies have highlighted an escalating aversion among audiences towards traditional online ads, leading to a diminishing effectiveness of traditional online advertising methods (Lou et al., 2019 ). In an effort to overcome these challenges, an increasing number of brands are turning to influencers as their spokespersons for advertising. Utilizing influencers not only capitalizes on their significant influence over their fan base but also allows for the dissemination of advertising messages in a more native and organic manner. Consequently, influencer-endorsed advertising has become a pivotal component and a growing trend in social media advertising (Gräve & Bartsch, 2022 ). Although the topic of influencer-endorsed advertising has garnered increasing attention from scholars, the field is still in its infancy, offering ample opportunities for in-depth research and exploration (Barta et al., 2023 ).

Presently, social media influencers—individuals with substantial follower bases—have emerged as the new vanguard in advertising (Hudders & Lou, 2023 ). Their tweets and videos possess the remarkable potential to sway the purchasing decisions of thousands if not millions. This influence largely hinges on consumer engagement behaviors, implying that the impact of advertising can proliferate throughout a consumer’s entire social network (Abbasi et al., 2023 ). Consequently, exploring ways to enhance consumer engagement is of paramount theoretical and practical significance for advertising effectiveness research (Xiao et al., 2023 ). This necessitates researchers to delve deeper into the exploration of the stimulating factors and psychological mechanisms influencing consumer engagement behaviors (Vander Schee et al., 2020 ), which is the gap this study seeks to address.

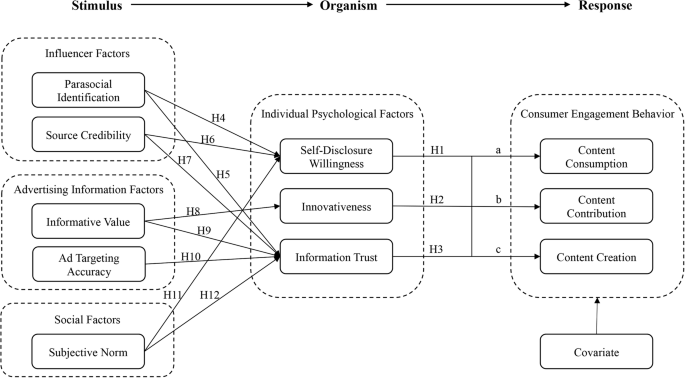

The Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework has been extensively applied in the study of consumer engagement behaviors (Tak & Gupta, 2021 ) and has been shown to integrate effectively with self-determination theory (Yang et al., 2019 ). Therefore, employing the S-O-R framework to investigate consumer engagement behaviors in the context of influencer advertising is considered a rational approach. The current study embarks on an in-depth analysis of the transformation process from three distinct dimensions. In the Stimulus (S) phase, we focus on how influencer factors, advertising message factors, and social influence factors act as external stimuli. This phase scrutinizes the external environment’s role in triggering consumer reactions. During the Organism (O) phase, the research explores the intrinsic psychological motivations affecting individual behavior as posited in self-determination theory. This includes the willingness for self-disclosure, the desire for innovation, and trust in advertising messages. The investigation in this phase aims to understand how these internal motivations shape consumer attitudes and perceptions in the context of influencer marketing. Finally, in the Response (R) phase, the study examines how these psychological factors influence consumer engagement behavior. This part of the research seeks to understand the transition from internal psychological states to actual consumer behavior, particularly how these states drive the consumers’ deep integration and interaction with the influencer content.

Despite the inherent limitations of cross-sectional analysis in capturing the full temporal dynamics of consumer engagement, this study seeks to unveil the dynamic interplay between consumers’ psychological needs—autonomy, competence, and relatedness—and their varying engagement levels in social media influencer marketing, grounded in self-determination theory. Through this lens, by analyzing factors related to influencers, content, and social context, we aim to infer potential dynamic shifts in engagement behaviors as psychological needs evolve. This approach allows us to offer a snapshot of the complex, multi-dimensional nature of consumer engagement dynamics, providing valuable insights for both theoretical exploration and practical application in the constantly evolving domain of social media marketing. Moreover, the current study underscores the significance of adapting to the dynamic digital environment and highlights the evolving nature of consumer engagement in the realm of digital marketing.

Literature review

Stimulus-organism-response (s-o-r) model.

The Stimulus-Response (S-R) model, originating from behaviorist psychology and introduced by psychologist Watson ( 1917 ), posits that individual behaviors are directly induced by external environmental stimuli. However, this model overlooks internal personal factors, complicating the explanation of psychological states. Mehrabian and Russell ( 1974 ) expanded this by incorporating the individual’s cognitive component (organism) into the model, creating the Stimulus-Organism-Response (S-O-R) framework. This model has become a crucial theoretical framework in consumer psychology as it interprets internal psychological cognitions as mediators between stimuli and responses. Integrating with psychological theories, the S-O-R model effectively analyzes and explains the significant impact of internal psychological factors on behavior (Koay et al., 2020 ; Zhang et al., 2021 ), and is extensively applied in investigating user behavior on social media platforms (Hewei & Youngsook, 2022 ). This study combines the S-O-R framework with self-determination theory to examine consumer engagement behaviors in the context of social media influencer advertising, a logic also supported by some studies (Yang et al., 2021 ).

Self-determination theory

Self-determination theory, proposed by Richard and Edward (2000), is a theoretical framework exploring human behavioral motivation and personality. The theory emphasizes motivational processes, positing that individual behaviors are developed based on factors satisfying their psychological needs. It suggests that individual behavioral tendencies are influenced by the needs for competence, relatedness, and autonomy. Furthermore, self-determination theory, along with organic integration theory, indicates that individual behavioral tendencies are also affected by internal psychological motivations and external situational factors.

Self-determination theory has been validated by scholars in the study of online user behaviors. For example, Sweet applied the theory to the investigation of community building in online networks, analyzing knowledge-sharing behaviors among online community members (Sweet et al., 2020 ). Further literature review reveals the applicability of self-determination theory to consumer engagement behaviors, particularly in the context of influencer marketing advertisements. Firstly, self-determination theory is widely applied in studying the psychological motivations behind online behaviors, suggesting that the internal and external motivations outlined within the theory might also apply to exploring consumer behaviors in influencer marketing scenarios (Itani et al., 2022 ). Secondly, although research on consumer engagement in the social media influencer advertising context is still in its early stages, some studies have utilized SDT to explore behaviors such as information sharing and electronic word-of-mouth dissemination (Astuti & Hariyawan, 2021 ). These behaviors, which are part of the content contribution and creation dimensions of consumer engagement, may share similarities in the underlying psychological motivational mechanisms. Thus, this study will build upon these foundations to construct the Organism (O) component of the S-O-R model, integrating insights from SDT to further understand consumer engagement in influencer marketing.

Consumer engagement

Although scholars generally agree at a macro level to define consumer engagement as the creation of additional value by consumers or customers beyond purchasing products, the specific categorization of consumer engagement varies in different studies. For instance, Simon and Tossan interpret consumer engagement as a psychological willingness to interact with influencers (Simon & Tossan, 2018 ). However, such a broad definition lacks precision in describing various levels of engagement. Other scholars directly use tangible metrics on social media platforms, such as likes, saves, comments, and shares, to represent consumer engagement (Lee et al., 2018 ). While this quantitative approach is not flawed and can be highly effective in practical applications, it overlooks the content aspect of engagement, contradicting the “content is king” principle of advertising and marketing. We advocate for combining consumer engagement with the content aspect, as content engagement not only generates more traces of consumer online behavior (Oestreicher-Singer & Zalmanson, 2013 ) but, more importantly, content contribution and creation are central to social media advertising and marketing, going beyond mere content consumption (Qiu & Kumar, 2017 ). Meanwhile, we also need to emphasize that engagement is not a fixed state but a fluctuating process influenced by ongoing interactions between consumers and influencers, mediated by the evolving nature of social media platforms and the shifting sands of consumer preferences (Pradhan et al., 2023 ). Consumer engagement in digital environments undergoes continuous change, reflecting a journey rather than a destination (Viswanathan et al., 2017 ).

The current study adopts a widely accepted definition of consumer engagement from existing research, offering operational feasibility and aligning well with the research objectives of this paper. Consumer engagement behaviors in the context of this study encompass three dimensions: content consumption, content contribution, and content creation (Muntinga et al., 2011 ). These dimensions reflect a spectrum of digital engagement behaviors ranging from low to high levels (Schivinski et al., 2016 ). Specifically, content consumption on social media platforms represents a lower level of engagement, where consumers merely click and read the information but do not actively contribute or create user-generated content. Some studies consider this level of engagement as less significant for in-depth exploration because content consumption, compared to other forms, generates fewer visible traces of consumer behavior (Brodie et al., 2013 ). Even in a study by Qiu and Kumar, it was noted that the conversion rate of content consumption is low, contributing minimally to the success of social media marketing (Qiu & Kumar, 2017 ).

On the other hand, content contribution, especially content creation, is central to social media marketing. When consumers comment on influencer content or share information with their network nodes, it is termed content contribution, representing a medium level of online consumer engagement (Piehler et al., 2019 ). Furthermore, when consumers actively upload and post brand-related content on social media, this higher level of behavior is referred to as content creation. Content creation represents the highest level of consumer engagement (Cheung et al., 2021 ). Although medium and high levels of consumer engagement are more valuable for social media advertising and marketing, this exploratory study still retains the content consumption dimension of consumer engagement behaviors.

Theoretical framework

Internal organism factors: self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust.

In existing research based on self-determination theory that focuses on online behavior, competence, relatedness, and autonomy are commonly considered as internal factors influencing users’ online behaviors. However, this approach sometimes strays from the context of online consumption. Therefore, in studies related to online consumption, scholars often use self-disclosure willingness as an overt representation of autonomy, innovativeness as a representation of competence, and trust as a representation of relatedness (Mahmood et al., 2019 ).

The use of these overt variables can be logically explained as follows: According to self-determination theory, individuals with a higher level of self-determination are more likely to adopt compensatory mechanisms to facilitate behavior compared to those with lower self-determination (Wehmeyer, 1999 ). Self-disclosure, a voluntary act of sharing personal information with others, is considered a key behavior in the development of interpersonal relationships. In social environments, self-disclosure can effectively alleviate stress and build social connections, while also seeking societal validation of personal ideas (Altman & Taylor, 1973 ). Social networks, as para-social entities, possess the interactive attributes of real societies and are likely to exhibit similar mechanisms. In consumer contexts, personal disclosures can include voluntary sharing of product interests, consumption experiences, and future purchase intentions (Robertshaw & Marr, 2006 ). While material incentives can prompt personal information disclosure, many consumers disclose personal information online voluntarily, which can be traced back to an intrinsic need for autonomy (Stutzman et al., 2011 ). Thus, in this study, we consider the self-disclosure willingness as a representation of high autonomy.

Innovativeness refers to an individual’s internal level of seeking novelty and represents their personality and tendency for novelty (Okazaki, 2009 ). Often used in consumer research, innovative consumers are inclined to try new technologies and possess an intrinsic motivation to use new products. Previous studies have shown that consumers with high innovativeness are more likely to search for information on new products and share their experiences and expertise with others, reflecting a recognition of their own competence (Kaushik & Rahman, 2014 ). Therefore, in consumer contexts, innovativeness is often regarded as the competence dimension within the intrinsic factors of self-determination (Wang et al., 2016 ), with external motivations like information novelty enhancing this intrinsic motivation (Lee et al., 2015 ).

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to rely on the opinions of others they believe in. From a social psychological perspective, trust indicates the willingness to assume the risk of being harmed by another party (McAllister, 1995 ). Widely applied in social media contexts for relational marketing, information trust has been proven to positively influence the exchange and dissemination of consumer information, representing a close and advanced relationship between consumers and businesses, brands, or advertising endorsers (Steinhoff et al., 2019 ). Consumers who trust brands or social media influencers are more willing to share information without fear of exploitation (Pop et al., 2022 ), making trust a commonly used representation of the relatedness dimension in self-determination within consumer contexts.

Construction of the path from organism to response: self-determination internal factors and consumer engagement behavior

Following the logic outlined above, the current study represents the internal factors of self-determination theory through three variables: self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust. Next, the study explores the association between these self-determination internal factors and consumer engagement behavior, thereby constructing the link between Organism (O) and Response (R).

Self-disclosure willingness and consumer engagement behavior

In the realm of social sciences, the concept of self-disclosure willingness has been thoroughly examined from diverse disciplinary perspectives, encompassing communication studies, sociology, and psychology. Viewing from the lens of social interaction dynamics, self-disclosure is acknowledged as a fundamental precondition for the initiation and development of online social relationships and interactive engagements (Luo & Hancock, 2020 ). It constitutes an indispensable component within the spectrum of interactive behaviors and the evolution of interpersonal connections. Voluntary self-disclosure is characterized by individuals divulging information about themselves, which typically remains unknown to others and is inaccessible through alternative sources. This concept aligns with the tenets of uncertainty reduction theory, which argues that during interpersonal engagements, individuals seek information about their counterparts as a means to mitigate uncertainties inherent in social interactions (Lee et al., 2008 ). Self-disclosure allows others to gain more personal information, thereby helping to reduce the uncertainty in interpersonal relationships. Such disclosure is voluntary rather than coerced, and this sharing of information can facilitate the development of relationships between individuals (Towner et al., 2022 ). Furthermore, individuals who actively engage in social media interactions (such as liking, sharing, and commenting on others’ content) often exhibit higher levels of self-disclosure (Chu et al., 2023 ); additional research indicates a positive correlation between self-disclosure and online engagement behaviors (Lee et al., 2023 ). Taking the context of the current study, the autonomous self-disclosure willingness can incline social media users to read advertising content more attentively and share information with others, and even create evaluative content. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypothesis:

H1a: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H1b: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H1c: The self-disclosure willingness is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Innovativeness and consumer engagement behavior

Innovativeness represents an individual’s propensity to favor new technologies and the motivation to use new products, associated with the cognitive perception of one’s self-competence. Individuals with a need for self-competence recognition often exhibit higher innovativeness (Kelley & Alden, 2016 ). Existing research indicates that users with higher levels of innovativeness are more inclined to accept new product information and share their experiences and discoveries with others in their social networks (Yusuf & Busalim, 2018 ). Similarly, in the context of this study, individuals, as followers of influencers, signify an endorsement of the influencer. Driven by innovativeness, they may be more eager to actively receive information from influencers. If they find the information valuable, they are likely to share it and even engage in active content re-creation to meet their expectations of self-image. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H2a: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H2b: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H2c: The innovativeness of social media users is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Information trust and consumer engagement

Trust refers to an individual’s willingness to rely on the statements and opinions of a target object (Moorman et al., 1993 ). Extensive research indicates that trust positively impacts information dissemination and content sharing in interpersonal communication environments (Majerczak & Strzelecki, 2022 ); when trust is established, individuals are more willing to share their resources and less suspicious of being exploited. Trust has also been shown to influence consumers’ participation in community building and content sharing on social media, demonstrating cross-cultural universality (Anaya-Sánchez et al., 2020 ).

Trust in influencer advertising information is also a key predictor of consumers’ information exchange online. With many social media users now operating under real-name policies, there is an increased inclination to trust information shared on social media over that posted by corporate accounts or anonymously. Additionally, as users’ social networks partially overlap with their real-life interpersonal networks, extensive research shows that more consumers increasingly rely on information posted and shared on social networks when making purchase decisions (Wang et al., 2016 ). This aligns with the effectiveness goals of influencer marketing advertisements and the characteristics of consumer engagement. Trust in the content posted by influencers is considered a manifestation of a strong relationship between fans and influencers, central to relationship marketing (Kim & Kim, 2021 ). Based on trust in the influencer, which then extends to trust in their content, people are more inclined to browse information posted by influencers, share this information with others, and even create their own content without fear of exploitation or negative consequences. Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H3a: Information trust is positively correlated with content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H3b: Information trust is positively correlated with content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H3c: Information trust is positively correlated with content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Construction of the path from stimulus to organism: influencer factors, advertising information factors, social factors, and self-determination internal factors

Having established the logical connection from Organism (O) to Response (R), we further construct the influence path from Stimulus (S) to Organism (O). Revisiting the definition of influencer advertising in social media, companies, and brands leverage influencers on social media platforms to disseminate advertising content, utilizing the influencers’ relationships and influence over consumers for marketing purposes. In addition to consumer’s internal factors, elements such as companies, brands, influencers, and the advertisements themselves also impact consumer behavior. Although factors like the brand image perception of companies may influence consumer behavior, considering that in influencer marketing, companies and brands do not directly interact with consumers, this study prioritizes the dimensions of influencers and advertisements. Furthermore, the impact of social factors on individual cognition and behavior is significant, thus, the current study integrates influencers, advertisements, and social dimensions as the Stimulus (S) component.

Influencer factors: parasocial identification

Self-determination theory posits that relationships are one of the key motivators influencing individual behavior. In the context of social media research, users anticipate establishing a parasocial relationship with influencers, resembling real-life relationships. Hence, we consider the parasocial identification arising from users’ parasocial interactions with influencers as the relational motivator. Parasocial interaction refers to the one-sided personal relationship that individuals develop with media characters (Donald & Richard, 1956 ). During this process, individuals believe that the media character is directly communicating with them, creating a sense of positive intimacy (Giles, 2002 ). Over time, through repeated unilateral interactions with media characters, individuals develop a parasocial relationship, leading to parasocial identification. However, parasocial identification should not be directly equated with the concept of social identification in social identity theory. Social identification occurs when individuals psychologically de-individualize themselves, perceiving the characteristics of their social group as their own, upon identifying themselves as part of that group. In contrast, parasocial identification refers to the one-sided interactional identification with media characters (such as celebrities or influencers) over time (Chen et al., 2021 ). Particularly when individuals’ needs for interpersonal interaction are not met in their daily lives, they turn to parasocial interactions to fulfill these needs (Shan et al., 2020 ). Especially on social media, which is characterized by its high visibility and interactivity, users can easily develop a strong parasocial identification with the influencers they follow (Wei et al., 2022 ).

Parasocial identification and self-disclosure willingness

Theories like uncertainty reduction, personal construct, and social exchange are often applied to explain the emergence of parasocial identification. Social media, with its convenient and interactive modes of information dissemination, enables consumers to easily follow influencers on media platforms. They can perceive the personality of influencers through their online content, viewing them as familiar individuals or even friends. Once parasocial identification develops, this pleasurable experience can significantly influence consumers’ cognitions and thus their behavioral responses. Research has explored the impact of parasocial identification on consumer behavior. For instance, Bond et al. found that on Twitter, the intensity of users’ parasocial identification with influencers positively correlates with their continuous monitoring of these influencers’ activities (Bond, 2016 ). Analogous to real life, where we tend to pay more attention to our friends in our social networks, a similar phenomenon occurs in the relationship between consumers and brands. This type of parasocial identification not only makes consumers willing to follow brand pages but also more inclined to voluntarily provide personal information (Chen et al., 2021 ). Based on this logic, we speculate that a similar relationship may exist between social media influencers and their fans. Fans develop parasocial identification with influencers through social media interactions, making them more willing to disclose their information, opinions, and views in the comment sections of the influencers they follow, engaging in more frequent social interactions (Chung & Cho, 2017 ), even if the content at times may be brand or company-embedded marketing advertisements. In other words, in the presence of influencers with whom they have established parasocial relationships, they are more inclined to disclose personal information, thereby promoting consumer engagement behavior. Therefore, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H4: Parasocial identification is positively correlated with consumer self-disclosure willingness.

H4a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H4b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H4c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Parasocial identification and information trust

Information Trust refers to consumers’ willingness to trust the information contained in advertisements and to place themselves at risk. These risks include purchasing products inconsistent with the advertised information and the negative social consequences of erroneously spreading this information to others, leading to unpleasant consumption experiences (Minton, 2015 ). In advertising marketing, gaining consumers’ trust in advertising information is crucial. In the context of influencer marketing on social media, companies, and brands leverage the social connection between influencers and their fans. According to cognitive empathy theory, consumers project their trust in influencers onto the products endorsed, explaining the phenomenon of ‘loving the house for the crow on its roof.’ Research indicates that parasocial identification with influencers is a necessary condition for trust development. Consumers engage in parasocial interactions with influencers on social media, leading to parasocial identification (Jin et al., 2021 ). Consumers tend to reduce their cognitive load and simplify their decision-making processes, thus naturally adopting a positive attitude and trust towards advertising information disseminated by influencers with whom they have established parasocial identification. This forms the core logic behind the success of influencer marketing advertisements (Breves et al., 2021 ); furthermore, as mentioned earlier, because consumers trust these advertisements, they are also willing to share this information with friends and family and even engage in content re-creation. Therefore, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H5: Parasocial identification is positively correlated with information trust.

H5a: Information trust mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H5b: Information trust mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H5c: Information trust mediates the impact of parasocial identification on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

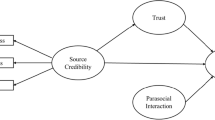

Influencer factors: source credibility

Source credibility refers to the degree of trust consumers place in the influencer as a source, based on the influencer’s reliability and expertise. Numerous studies have validated the effectiveness of the endorsement effect in advertising (Schouten et al., 2021 ). The Source Credibility Model, proposed by the renowned American communication scholar Hovland and the “Yale School,” posits that in the process of information dissemination, the credibility of the source can influence the audience’s decision to accept the information. The credibility of the information is determined by two aspects of the source: reliability and expertise. Reliability refers to the audience’s trust in the “communicator’s objective and honest approach to providing information,” while expertise refers to the audience’s trust in the “communicator being perceived as an effective source of information” (Hovland et al., 1953 ). Hovland’s definitions reveal that the interpretation of source credibility is not about the inherent traits of the source itself but rather the audience’s perception of the source (Jang et al., 2021 ). This differs from trust and serves as a precursor to the development of trust. Specifically, reliability and expertise are based on the audience’s perception; thus, this aligns closely with the audience’s perception of influencers (Kim & Kim, 2021 ). This credibility is a cognitive statement about the source of information.

Source credibility and self-disclosure willingness

Some studies have confirmed the positive impact of an influencer’s self-disclosure on their credibility as a source (Leite & Baptista, 2022 ). However, few have explored the impact of an influencer’s credibility, as a source, on consumers’ self-disclosure willingness. Undoubtedly, an impact exists; self-disclosure is considered a method to attempt to increase intimacy with others (Leite et al., 2022 ). According to social exchange theory, people promote relationships through the exchange of information in interpersonal communication to gain benefits (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005 ). Credibility, deriving from an influencer’s expertise and reliability, means that a highly credible influencer may provide more valuable information to consumers. Therefore, based on the social exchange theory’s logic of reciprocal benefits, consumers might be more willing to disclose their information to trustworthy influencers, potentially even expanding social interactions through further consumer engagement behaviors. Thus, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H6: Source credibility is positively correlated with self-disclosure willingness.

H6a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of Source credibility on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H6b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of Source credibility on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H6c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of Source credibility on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Source credibility and information trust

Based on the Source Credibility Model, the credibility of an endorser as an information source can significantly influence consumers’ acceptance of the information (Shan et al., 2020 ). Existing research has demonstrated the positive impact of source credibility on consumers. Djafarova, in a study based on Instagram, noted through in-depth interviews with 18 users that an influencer’s credibility significantly affects respondents’ trust in the information they post. This credibility is composed of expertise and relevance to consumers, and influencers on social media are considered more trustworthy than traditional celebrities (Djafarova & Rushworth, 2017 ). Subsequently, Bao and colleagues validated in the Chinese consumer context, based on the ELM model and commitment-trust theory, that the credibility of brand pages on Weibo effectively fosters consumer trust in the brand, encouraging participation in marketing activities (Bao & Wang, 2021 ). Moreover, Hsieh et al. found that in e-commerce contexts, the credibility of the source is a significant factor influencing consumers’ trust in advertising information (Hsieh & Li, 2020 ). In summary, existing research has proven that the credibility of the source can promote consumer trust. Influencer credibility is a significant antecedent affecting consumers’ trust in the advertised content they publish. In brand communities, trust can foster consumer engagement behaviors (Habibi et al., 2014 ). Specifically, consumers are more likely to trust the advertising content published by influencers with higher credibility (more expertise and reliability), and as previously mentioned, consumer engagement behavior is more likely to occur. Based on this, the study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H7: Source credibility is positively correlated with information trust.

H7a: Information trust mediates the impact of source credibility on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H7b: Information trust mediates the impact of source credibility on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H7c: Information trust mediates the impact of source credibility on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Advertising information factors: informative value

Advertising value refers to “the relative utility value of advertising information to consumers and is a subjective evaluation by consumers.” In his research, Ducoffe pointed out that in the context of online advertising, the informative value of advertising is a significant component of advertising value (Ducoffe, 1995 ). Subsequent studies have proven that consumers’ perception of advertising value can effectively promote their behavioral response to advertisements (Van-Tien Dao et al., 2014 ). Informative value of advertising refers to “the information about products needed by consumers provided by the advertisement and its ability to enhance consumer purchase satisfaction.” From the perspective of information dissemination, valuable advertising information should help consumers make better purchasing decisions and reduce the effort spent searching for product information. The informational aspect of advertising has been proven to effectively influence consumers’ cognition and, in turn, their behavior (Haida & Rahim, 2015 ).

Informative value and innovativeness

As previously discussed, consumers’ innovativeness refers to their psychological trait of favoring new things. Studies have shown that consumers with high innovativeness prefer novel and valuable product information, as it satisfies their need for newness and information about new products, making it an important factor in social media advertising engagement (Shi, 2018 ). This paper also hypothesizes that advertisements with high informative value can activate consumers’ innovativeness, as the novelty of information is one of the measures of informative value (León et al., 2009 ). Acquiring valuable information can make individuals feel good about themselves and fulfill their perception of a “novel image.” According to social exchange theory, consumers can gain social capital in interpersonal interactions (such as social recognition) by sharing information about these new products they perceive as valuable. Therefore, the current study proposes the following research hypothesis:

H8: Informative value is positively correlated with innovativeness.

H8a: Innovativeness mediates the impact of informative value on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H8b: Innovativeness mediates the impact of informative value on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H8c: Innovativeness mediates the impact of informative value on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Informative value and information trust

Trust is a multi-layered concept explored across various disciplines, including communication, marketing, sociology, and psychology. For the purposes of this paper, a deep analysis of different levels of trust is not undertaken. Here, trust specifically refers to the trust in influencer advertising information within the context of social media marketing, denoting consumers’ belief in and reliance on the advertising information endorsed by influencers. Racherla et al. investigated the factors influencing consumers’ trust in online reviews, suggesting that information quality and value contribute to increasing trust (Racherla et al., 2012 ). Similarly, Luo and Yuan, in a study based on social media marketing, also confirmed that the value of advertising information posted on brand pages can foster consumer trust in the content (Lou & Yuan, 2019 ). Therefore, by analogy, this paper posits that the informative value of influencer-endorsed advertising can also promote consumer trust in that advertising information. The relationship between trust in advertising information and consumer engagement behavior has been discussed earlier. Thus, the current study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H9: Informative value is positively correlated with information trust.

H9a: Information trust mediates the impact of informative value on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H9b: Information trust mediates the impact of informative value on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H9c: Information trust mediates the impact of informative value on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Advertising information factors: ad targeting accuracy

Ad targeting accuracy refers to the degree of match between the substantive information contained in advertising content and consumer needs. Advertisements containing precise information often yield good advertising outcomes. In marketing practice, advertisers frequently use information technology to analyze the characteristics of different consumer groups in the target market and then target their advertisements accordingly to achieve precise dissemination and, consequently, effective advertising results. The utility of ad targeting accuracy has been confirmed by many studies. For instance, in the research by Qiu and Chen, using a modified UTAUT model, it was demonstrated that the accuracy of advertising effectively promotes consumer acceptance of advertisements in WeChat Moments (Qiu & Chen, 2018 ). Although some studies on targeted advertising also indicate that overly precise ads may raise concerns about personal privacy (Zhang et al., 2019 ), overall, the accuracy of advertising information is effective in enhancing advertising outcomes and is a key element in the success of targeted advertising.

Ad targeting accuracy and information trust

In influencer marketing advertisements, due to the special relationship recognition between consumers and influencers, the privacy concerns associated with ad targeting accuracy are alleviated (Vrontis et al., 2021 ). Meanwhile, the informative value brought by targeting accuracy is highlighted. More precise advertising content implies higher informative value and also signifies that the advertising content is more worthy of consumer trust (Della Vigna, Gentzkow, 2010 ). As previously discussed, people are more inclined to read and engage with advertising content they trust and recognize. Therefore, the current study proposes the following research hypotheses:

H10: Ad targeting accuracy is positively correlated with information trust.

H10a: Information trust mediates the impact of ad targeting accuracy on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H10b: Information trust mediates the impact of ad targeting accuracy on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H10c: Information trust mediates the impact of ad targeting accuracy on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Social factors: subjective norm

The Theory of Planned Behavior, proposed by Ajzen ( 1991 ), suggests that individuals’ actions are preceded by conscious choices and are underlain by plans. TPB has been widely used by scholars in studying personal online behaviors, these studies collectively validate the applicability of TPB in the context of social media for researching online behaviors (Huang, 2023 ). Additionally, the self-determination theory, which underpins this chapter’s research, also supports the notion that individuals’ behavioral decisions are based on internal cognitions, aligning with TPB’s assertions. Therefore, this paper intends to select subjective norms from TPB as a factor of social influence. Subjective norm refers to an individual’s perception of the expectations of significant others in their social relationships regarding their behavior. Empirical research in the consumption field has demonstrated the significant impact of subjective norms on individual psychological cognition (Yang & Jolly, 2009 ). A meta-analysis by Hagger, Chatzisarantis ( 2009 ) even highlighted the statistically significant association between subjective norms and self-determination factors. Consequently, this study further explores its application in the context of influencer marketing advertisements on social media.

Subjective norm and self-disclosure willingness

In numerous studies on social media privacy, subjective norms significantly influence an individual’s self-disclosure willingness. Wirth et al. ( 2019 ) based on the privacy calculus theory, surveyed 1,466 participants and found that personal self-disclosure on social media is influenced by the behavioral expectations of other significant reference groups around them. Their research confirmed that subjective norms positively influence self-disclosure of information and highlighted that individuals’ cognitions and behaviors cannot ignore social and environmental factors. Heirman et al. ( 2013 ) in an experiment with Instagram users, also noted that subjective norms could promote positive consumer behavioral responses. Specifically, when important family members and friends highly regard social media influencers as trustworthy, we may also be more inclined to disclose our information to influencers and share this information with our surrounding family and friends without fear of disapproval. In our subjective norms, this is considered a positive and valuable interactive behavior, leading us to exhibit engagement behaviors. Based on this logic, we propose the following research hypotheses:

H11: Subjective norms are positively correlated with self-disclosure willingness.

H11a: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of subjective norms on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H11b: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of subjective norms on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H11c: Self-disclosure willingness mediates the impact of subjective norms on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

Subjective norm and information trust

Numerous studies have indicated that subjective norms significantly influence trust (Roh et al., 2022 ). This can be explained by reference group theory, suggesting people tend to minimize the effort expended in decision-making processes, often looking to the behaviors or attitudes of others as a point of reference; for instance, subjective norms can foster acceptance of technology by enhancing trust (Gupta et al., 2021 ). Analogously, if a consumer’s social network generally holds positive attitudes toward influencer advertising, they are also more likely to trust the endorsed advertisement information, as it conserves the extensive effort required in gathering product information (Chetioui et al., 2020 ). Therefore, this paper proposes the following research hypotheses:

H12: Subjective norms are positively correlated with information trust.

H12a: Information trust mediates the impact of subjective norms on content consumption in consumer engagement behavior.

H12b: Information trust mediates the impact of subjective norms on content contribution in consumer engagement behavior.

H12c: Information trust mediates the impact of subjective norms on content creation in consumer engagement behavior.

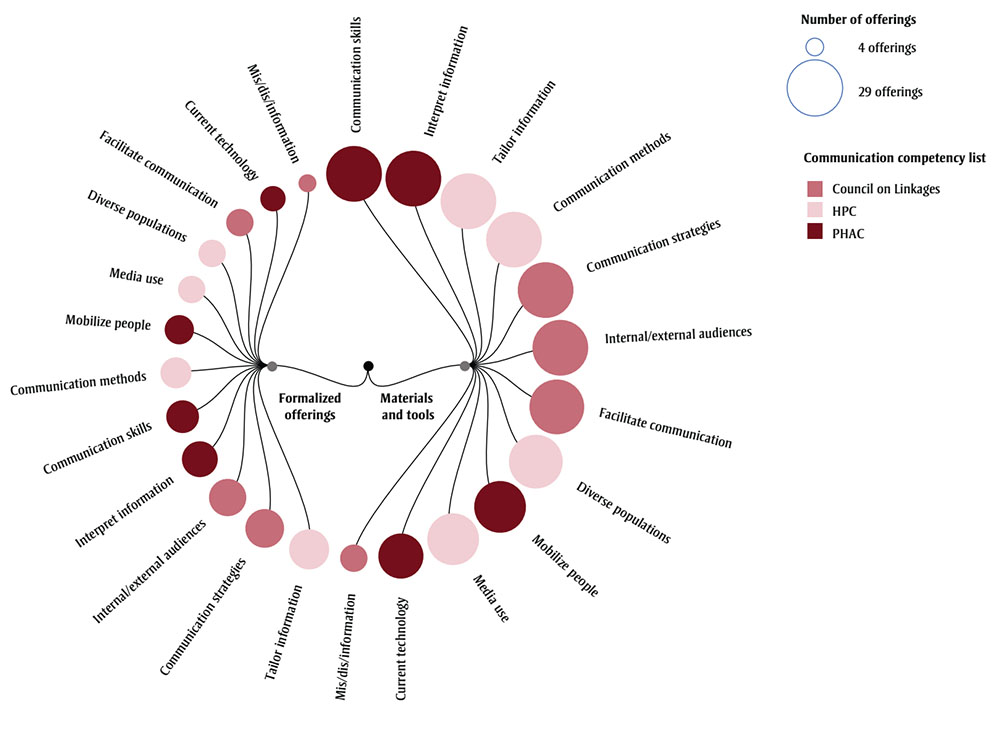

Conceptual model

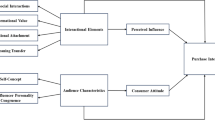

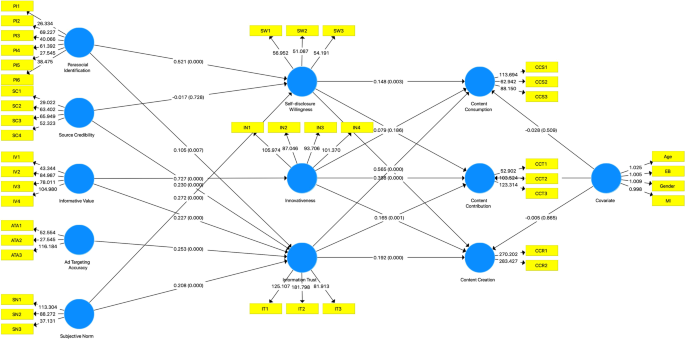

In summary, based on the Stimulus (S)-Organism (O)-Response (R) framework, this study constructs the external stimulus factors (S) from three dimensions: influencer factors (parasocial identification, source credibility), advertising information factors (informative value, Ad targeting accuracy), and social influence factors (subjective norms). This is grounded in social capital theory and the theory of planned behavior. drawing on self-determination theory, the current study constructs the individual psychological factors (O) using self-disclosure willingness, innovativeness, and information trust. Finally, the behavioral response (R) is constructed using consumer engagement, which includes content consumption, content contribution, and content creation, as illustrated in Fig. 1 .

Consumer engagement behavior impact model based on SOR framework.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures.