- Customer Reviews

- Extended Essays

- IB Internal Assessment

- Theory of Knowledge

- Literature Review

- Dissertations

- Essay Writing

- Research Writing

- Assignment Help

- Capstone Projects

- College Application

- Online Class

How to Select a Research Topic: A Step-by-Step Guide (2021)

by Antony W

September 15, 2021

Learning how to select a research topic can be the difference between failing your assignment and writing a comprehensive research paper. That’s why in this guide we’ll teach you how to select a research topic step-by-step.

You don’t need this guide if your professor has already given you a list of topics to consider for your assignment . You can skip to our guide on how to write a research paper .

If they have left it up to you to choose a topic to investigate, which they must approve before you start working on your research study, we suggest that you read the process shared in this post.

Choosing a topic after finding your research problem is important because:

- The topic guides your research and gives you a mean to not only arrive at other interesting topics but also direct you to discover new knowledge

- The topic you choose will govern what you say and ensures you keep a logical flow of information.

Picking a topic for a research paper can be challenging and sometimes intimidating, but it’s not impossible. In the following section, we show you how to choose the best research topic that your instructor can approve after the first review.

How to Select a Research Topic

Below are four steps to follow to find the most suitable topic for your research paper assignment:

Step 1: Consider a Topic that Interests You

If your professor has asked you to choose a topic for your research paper, it means you can choose just about any subject to focus on in your area of study. A significant first step to take is to consider topics that interest you.

An interesting topic should meet two very important conditions.

First, it should be concise. The topic you choose should not be too broad or two narrow. Rather, it should be something focused on a specific issue. Second, the topic should allow you to find enough sources to cite in the research stage of your assignment.

The best way to determine if the research topic is interesting is to do some free writing for about 10 minutes. As you free write, think about the number of questions that people ask about the topic and try to consider why they’re important. These questions are important because they will make the research stage easier for you.

You’ll probably have a long list of interesting topics to consider for your research assignment. That’s a good first step because it means your options aren’t limited. However, you need to narrow down to only one topic for the assignment, so it’s time to start brainstorming.

Step 2: Brainstorm Your Topics

You aren’t doing research at this stage yet. You are only trying to make considerations to determine which topic will suit your research assignment.

The brainstorming stage isn’t difficult at all. It should take only a couple of hours or a few days depending on how you approach.

We recommend talking to your professor, classmates, and friends about the topics that you’ve picked and ask for their opinion. Expect mixed opinions from this audience and then consider the topics that make the most sense. Note what topics picked their interest the most and put them on top of the list.

You’ll end up removing some topics from your initial list after brainstorming, and that’s completely fine. The goal here is to end up with a topic that interests you as well as your readers.

Step 3: Define Your Topics

Check once again to make sure that your topic is a subject that you can easily define. You want to make sure the topic isn’t too broad or too narrow.

Often, a broad topic presents overwhelming amount of information, which makes it difficult to write a comprehensive research paper. A narrow topic, on the other hand, means you’ll find very little information, and therefore it can be difficult to do your assignment.

The length of the research paper, as stated in the assignment brief, should guide your topic selection.

Narrow down your list to topics that are:

- Broad enough to allows you to find enough scholarly articles and journals for reference

- Narrow enough to fit within the expected word count and the scope of the research

Topics that meet these two conditions should be easy to work on as they easily fit within the constraints of the research assignment.

Step 4: Read Background Information of Selected Topics

You probably have two or three topics by the time you get to this step. Now it’s time to read the background information on the topics to decide which topic to work on.

This step is important because it gives you a clear overview of the topic, enabling you to see how it relates to broader, narrower, and related concepts. Preliminary research also helps you to find keywords commonly used to describe the topic, which may be useful in further research.

It’s important to note how easy or difficult it is to find information on the topic.

Look at different sources of information to be sure you can find enough references for the topic. Such periodic indexes scan journals, newspaper articles, and magazines to find the information you’re looking for. You can even use web search engines. Google and Bing are currently that best options to consider because they make it easy for searchers to find relevant information on scholarly topics.

If you’re having a hard time to find references for a topic that you’ve so far considered for your research paper, skip it and go to the next one. Doing so will go a long way to ensure you have the right topic to work on from start to finish.

Get Research Paper Writing Help

If you’ve found your research topic but you feel so stuck that you can’t proceed with the assignment without some assistance, we are here to help. With our research paper writing service , we can help you handle the assignment within the shortest time possible.

We will research your topic, develop a research question, outline the project, and help you with writing. We also get you involved in the process, allowing you to track the progress of your order until the delivery stage.

About the author

Antony W is a professional writer and coach at Help for Assessment. He spends countless hours every day researching and writing great content filled with expert advice on how to write engaging essays, research papers, and assignments.

Selecting a Research Topic: Overview

- Refine your topic

- Background information & facts

- Writing help

Here are some resources to refer to when selecting a topic and preparing to write a paper:

- MIT Writing and Communication Center "Providing free professional advice about all types of writing and speaking to all members of the MIT community."

- Search Our Collections Find books about writing. Search by subject for: english language grammar; report writing handbooks; technical writing handbooks

- Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation Online version of the book that provides examples and tips on grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and other writing rules.

- Select a topic

Choosing an interesting research topic is your first challenge. Here are some tips:

- Choose a topic that you are interested in! The research process is more relevant if you care about your topic.

- If your topic is too broad, you will find too much information and not be able to focus.

- Background reading can help you choose and limit the scope of your topic.

- Review the guidelines on topic selection outlined in your assignment. Ask your professor or TA for suggestions.

- Refer to lecture notes and required texts to refresh your knowledge of the course and assignment.

- Talk about research ideas with a friend. S/he may be able to help focus your topic by discussing issues that didn't occur to you at first.

- WHY did you choose the topic? What interests you about it? Do you have an opinion about the issues involved?

- WHO are the information providers on this topic? Who might publish information about it? Who is affected by the topic? Do you know of organizations or institutions affiliated with the topic?

- WHAT are the major questions for this topic? Is there a debate about the topic? Are there a range of issues and viewpoints to consider?

- WHERE is your topic important: at the local, national or international level? Are there specific places affected by the topic?

- WHEN is/was your topic important? Is it a current event or an historical issue? Do you want to compare your topic by time periods?

Table of contents

- Broaden your topic

- Information Navigator home

- Sources for facts - general

- Sources for facts - specific subjects

Start here for help

Ask Us Ask a question, make an appointment, give feedback, or visit us.

- Next: Refine your topic >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2021 2:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

How To Choose A Research Topic

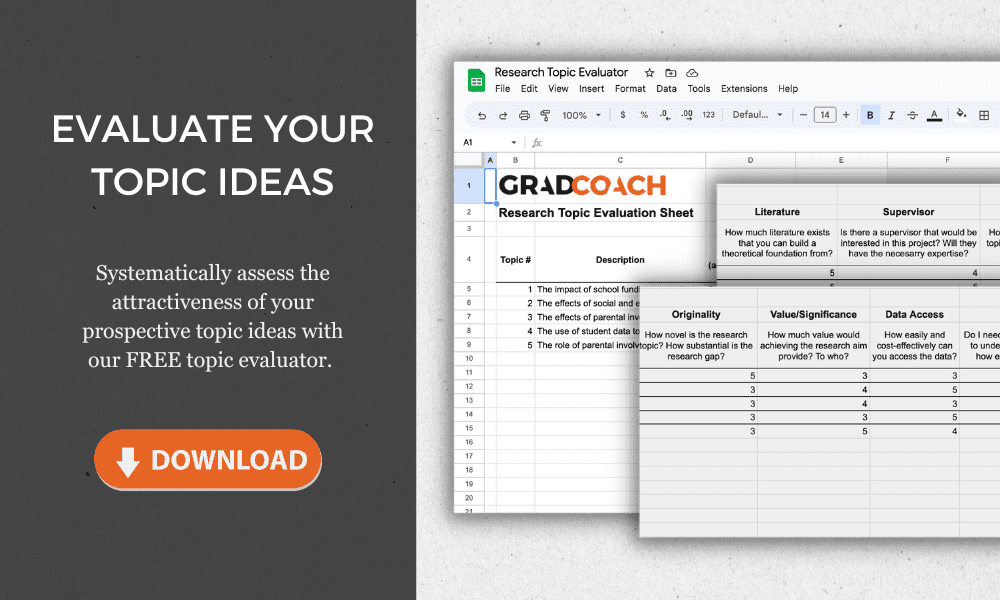

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + Free Topic Evaluator

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | April 2024

Choosing the right research topic is likely the most important decision you’ll make on your dissertation or thesis journey. To make the right choice, you need to take a systematic approach and evaluate each of your candidate ideas across a consistent set of criteria. In this tutorial, we’ll unpack five essential criteria that will help you evaluate your prospective research ideas and choose a winner.

Overview: The “Big 5” Key Criteria

- Topic originality or novelty

- Value and significance

- Access to data and equipment

- Time limitations and implications

- Ethical requirements and constraints

Criterion #1: Originality & Novelty

As we’ve discussed extensively on this blog, originality in a research topic is essential. In other words, you need a clear research gap . The uniqueness of your topic determines its contribution to the field and its potential to stand out in the academic community. So, for each of your prospective topics, ask yourself the following questions:

- What research gap and research problem am I filling?

- Does my topic offer new insights?

- Am I combining existing ideas in a unique way?

- Am I taking a unique methodological approach?

To objectively evaluate the originality of each of your topic candidates, rate them on these aspects. This process will not only help in choosing a topic that stands out, but also one that can capture the interest of your audience and possibly contribute significantly to the field of study – which brings us to our next criterion.

Criterion #2: Value & Significance

Next, you’ll need to assess the value and significance of each prospective topic. To do this, you’ll need to ask some hard questions.

- Why is it important to explore these research questions?

- Who stands to benefit from this study?

- How will they benefit, specifically?

By clearly understanding and outlining the significance of each potential topic, you’ll not only be justifying your final choice – you’ll essentially be laying the groundwork for a persuasive research proposal , which is equally important.

Criterion #3: Access to Data & Equipment

Naturally, access to relevant data and equipment is crucial for the success of your research project. So, for each of your prospective topic ideas, you’ll need to evaluate whether you have the necessary resources to collect data and conduct your study.

Here are some questions to ask for each potential topic:

- Will I be able to access the sample of interest (e.g., people, animals, etc.)?

- Do I have (or can I get) access to the required equipment, at the time that I need it?

- Are there costs associated with any of this? If so, what are they?

Keep in mind that getting access to certain types of data may also require special permissions and legalities, especially if your topic involves vulnerable groups (patients, youths, etc.). You may also need to adhere to specific data protection laws, depending on the country. So, be sure to evaluate these aspects thoroughly for each topic. Overlooking any of these can lead to significant complications down the line.

Criterion #4: Time Requirements & Implications

Naturally, having a realistic timeline for each potential research idea is crucial. So, consider the scope of each potential topic and estimate how long each phase of the research will take — from literature review to data collection and analysis, to writing and revisions. Underestimating the time needed for a research project is extremely common , so it’s important to include buffer time for unforeseen delays.

Remember, efficient time management is not just about the duration but also about the timing . For example, if your research involves fieldwork, there may specific times of the year when this is most doable (or not doable at all). So, be sure to consider both time and timing for each of your prospective topics.

Criterion #5: Ethical Compliance

Failing to adhere to your university’s research ethics policy is a surefire way to get your proposal rejected . So, you’ll need to evaluate each topic for potential ethical issues, especially if your research involves human subjects, sensitive data, or has any potential environmental impact.

Remember that ethical compliance is not just a formality – it’s a responsibility to ensure the integrity and social responsibility of your research. Topics that pose significant ethical challenges are typically the first to be rejected, so you need to take this seriously. It’s also useful to keep in mind that some topics are more “ethically sensitive” than others , which usually means that they’ll require multiple levels of approval. Ideally, you want to avoid this additional admin, so mark down any prospective topics that fall into an ethical “grey zone”.

If you’re unsure about the details of your university’s ethics policy, ask for a copy or speak directly to your course coordinator. Don’t make any assumptions when it comes to research ethics!

Key Takeaways

In this post, we’ve explored how to choose a research topic using a systematic approach. To recap, the “Big 5” assessment criteria include:

- Topic originality and novelty

- Time requirements

- Ethical compliance

Be sure to grab a copy of our free research topic evaluator sheet here to fast-track your topic selection process. If you need hands-on help finding and refining a high-quality research topic for your dissertation or thesis, you can also check out our private coaching service .

Need a helping hand?

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Identify and Develop a Topic: .

How to identify and develop a topic.

It is difficult to define a topic with much specificity before starting your research. But until you define your topic, you won't know where to begin your search for information and you won't know what to look for. With a well-defined topic, you can focus your search strategies to find lots of relevant information without also finding a lot of useless stuff.

Selecting a topic to research is not a one-step task. Identifying and developing your topic is an ongoing process that does not end until you have finished your research project. Start with an idea you are interested in. Find and read some background information to get a better understanding of the topic, then use what you have learned to search for more specific information. Refine (broaden, narrow, refocus, or change) your topic, and try another search.

Find a Topic

If you weren't assigned a specific topic and can't think of one:

- talk with your class instructor (who is, after all, the reason you are doing this project in the first place)

- find something interesting in the course reading assignments

- look at the entries and index of a subject encyclopedia

- ask a librarian to help you figure out a topic

Narrow Your Topic

The initial idea for a research topic is often too broad. If your first searches for resources are so general that you find more information than you can click a mouse at or deal with in a reasonable amount of time (i.e. before the research project is due), focus on one of the following:

- a specific period of time

- a specific geographic location

- specific individuals or groups

- a specific aspect of the subject

- the viewpoint of a specific discipline

Make it a Question

It is often helpful to state your topic in the form of a question. Treat the research project as an attempt to find a specific answer for a specific question.

List Main Concepts

Pull out ideas and key terms that describe your topic. You can get a better idea of these by looking up your topic in an encyclopedia or other appropriate reference work. This will give you a better understanding of your topic, which will help you figure out what sources you will need and where you will need to look to find them.

Analyze Your Topic

Where should you look for information? From what subject or discipline perspective are you looking at this topic? Do you need scholarly or popular sources? Will you need books, articles, sound recordings, primary sources, etc.?

Select Appropriate Tools

Which tools do you need to find the type of information you want, (e.g. the library catalog for books, subject specific indexes for journal articles, etc.) See the library's guide to How to Find and Evaluate Sources for more.

Initial Results

After you do an initial search, you can tell some things just from the number and type of sources you find. If you get a million or so hits, you probably need to narrow your topic. If you get only a few, broaden it. If the hits seem to be irrelevant to your topic, search using different terms. Do another search and see if you get what seems to be an appropriate amount of appropriate sources. Keep refining your search until you are satisfied with your results. Then go read them.

After reading through some of the sources you find, you will get a better understanding of the topic you are researching. With this better understanding, you can revise your initial topic and its corresponding question for which you are so diligently seeking an answer. You can also refine your search strategy: the databases you search in, the keywords or subject terms you search for, etc. Go back and try another search using your revisions. Repeat as necessary until you have done enough research to know what to ask and how to answer it.

- Last Updated: Oct 20, 2020 8:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/topic

Research Process Guide

- Step 1 - Identifying and Developing a Topic

- Step 2 - Narrowing Your Topic

- Step 3 - Developing Research Questions

- Step 4 - Conducting a Literature Review

- Step 5 - Choosing a Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

- Step 6 - Determining Research Methodology

- Step 6a - Determining Research Methodology - Quantitative Research Methods

- Step 6b - Determining Research Methodology - Qualitative Design

- Step 7 - Considering Ethical Issues in Research with Human Subjects - Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Step 8 - Collecting Data

- Step 9 - Analyzing Data

- Step 10 - Interpreting Results

- Step 11 - Writing Up Results

Step 1: Identifying and Developing a Topic

Whatever your field or discipline, the best advice to give on identifying a research topic is to choose something that you find really interesting. You will be spending an enormous amount of time with your topic, you need to be invested. Over the course of your research design, proposal and actually conducting your study, you may feel like you are really tired of your topic, however, your interest and investment in the topic will help you persist through dissertation defense. Identifying a research topic can be challenging. Most of the research that has been completed on the process of conducting research fails to examine the preliminary stages of the interactive and self-reflective process of identifying a research topic (Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). You may choose a topic at the beginning of the process, and through exploring the research that has already been done, one’s own interests that are narrowed or expanded in scope, the topic will change over time (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019). Where do I begin? According to the research, there are generally two paths to exploring your research topic, creative path and the rational path (Saunders et al., 2019). The rational path takes a linear path and deals with questions we need to ask ourselves like: what are some timely topics in my field in the media right now?; what strengths do I bring to the research?; what are the gaps in the research about the area of research interest? (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020).The creative path is less linear in that it may include keeping a notebook of ideas based on discussion in coursework or with your peers in the field. Whichever path you take, you will inevitably have to narrow your more generalized ideas down. A great way to do that is to continue reading the literature about and around your topic looking for gaps that could be explored. Also, try engaging in meaningful discussions with experts in your field to get their take on your research ideas (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). It is important to remember that a research topic should be (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020):

- Interesting to you.

- Realistic in that it can be completed in an appropriate amount of time.

- Relevant to your program or field of study.

- Not widely researched.

Dwarkadas, S., & Lin, M. C. (2019, August 04). Finding a research topic. Computing Research Association for Women, Portland State University. https://cra.org/cra-wp/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/FindingResearchTopic/2019.pdf

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

Wintersberger, D., & Saunders, M. (2020). Formulating and clarifying the research topic: Insights and a guide for the production management research community. Production, 30 . https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.20200059

- Last Updated: Jun 29, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.kean.edu/ResearchProcessGuide

Research Topics: How to Select & Develop: Refining a Research Topic

- Understanding the Assignment

- Choosing a Research Topic

- Refining a Research Topic

- Developing a Research Question

- Deciding What Types of Sources You Will Need

- Research Help

Ask a Librarian

Chat with a Librarian

Lisle: (630) 829-6057 Mesa: (480) 878-7514 Toll Free: (877) 575-6050 Email: [email protected]

Book a Research Consultation Library Hours

Research is a dynamic process. Be prepared to modify or refine your topic. This is usually the sign of thoughtful and well-done research. Usually researchers start out with a broad topic before narrowing it down. These strategies can help with that process.

Brainstorm Concepts

Think of words or concepts that relate to that topic. For example, if your topic is "polar bears," associated words might include: ice, cubs, pollution, hunting, diet, and environmental icon.

Make a Concept Map

Create a visual map your topic that shows different aspects of the topic. Think about questions related to your topic. Consider the who, what, where, when, and why (the 5 W's).

For example, when researching the local food culture, you might consider:

- Why do people buy local?

- What specific food items are people more likely to buy local and why?

- What are the economic aspects of buying local? Is it cheaper?

- Do people in all socio-economic strata have access to local food?

This short video explains how to make a concept map:

Source: Douglas College Library

You can make a concept map by hand or digitally. Below is a link to a free online concept mapping tool:

- Bubbl.us Free tool for building concept maps.

Consider Your Approach or Angle

Your research could, for example, use a historical angle (focusing on a particular time period); a geographical angle (focusing on a particular part of the world); or a sociological angle (focusing on a particular group of people). The angle you choose will depend largely on the nature of your research question and often on the class or the academic discipline in which you are working.

Conduct Background Research

Finding background information on your topic can also help you to refine your topic. Background research serves many purposes.

- If you are unfamiliar with the topic, it provides a good overview of the subject matter.

- It helps you to identify important facts related to your topic: terminology, dates, events, history, and names or organizations.

- It can help you to refine your topic.

- It might lead you to bibliographies that you can use to find additional sources of information on your topic.

Reference sources like the ones listed below can help you find an angle on your topic and identify an interesting research question. If you are focusing on a particular academic discipline, you might do background reading in subject-specific encyclopedias and reference sources. Background information can also be found in:

- dictionaries

- general encyclopedias

- subject-specific encyclopedias

- article databases

These sources are often listed in our Library Research Guides .

Here are some resources you may find helpful in finding a strong topic:

- I-Share Use I-Share to search for library materials at more than 80 libraries in Illinois and place requests.

- Wikipedia Get a quick overview of your topic. (Of course, evaluate these articles carefully, since anyone can change them). An entry's table of contents can help you identify possible research angles; the external links and references can help you locate other relevant sources. Usually you won't use Wikipedia in your final paper, because it's not an authoritative source.

- Gale Virtual Reference Library Reference eBooks on a variety of topics, including business, history, literature, medicine, social science, technology, and many more.

- Oxford Reference Reference eBooks on a handful of topics, including management, history, and religion.

Conduct Exploratory In-Depth Research

Start doing some exploratory, in-depth research. As you look for relevant sources, such as scholarly articles and books, refine your topic based on what you find. While examining sources, consider how others discuss the topic. How might the sources inform or challenge your approach to your research question?

- Choosing and Refining Topics Tutorial A detailed tutorial from Colorado State University

- << Previous: Choosing a Research Topic

- Next: Developing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 9:55 AM

- URL: https://researchguides.ben.edu/topics

Kindlon Hall 5700 College Rd. Lisle, IL 60532 (630) 829-6050

Gillett Hall 225 E. Main St. Mesa, AZ 85201 (480) 878-7514

Research Process: An Overview: Choosing a Topic

- Choosing a Topic

- Refining Your Topic

- Finding Information

- Evaluating Your Sources

- Database Searching

- APA Citation This link opens in a new window

- Topic selection

- Brainstorm Questions

- Tip: Keywords

- Finding Topic Ideas Online

Read Background Information

Tip: keywords.

Keywords are the main terms that describe your research question or topic. Keep track of these words so you can use them when searching for books and articles.

- Identify the main concepts in your research question. Typically there should only be two or three main concepts.

- Look for keywords that best describe these concepts.

- You can look for keywords when reading background information or encyclopedia articles on your topic

- Use a thesaurus, your textbook and subject headings in databases to find different keywords.

Related Research Guides

APA Citation

Click through the tabs to learn the basics, find examples, and watch video tutorials.

English Writing Skills

This guide supports academic and business writing, including a basic review of grammar fundamentals, writing guides, video tutorials on business writing, and resources for the TOEFL, IELTS, and PTE exams.

Getting Started

Topic selection.

Choosing your topic is the first step in the research process. Be aware that selecting a good topic may not be easy. It must be narrow and focused enough to be interesting, yet broad enough to find adequate information.

For help getting started on the writing process go to the GGU Online Writing Lab (Writing tutor) where you can set up and appointment with a writing tutor.

#1 Research ti p: Pick a topic that interests you. You are going to live with this topic for weeks while you research, read, and write your assignment. Choose something that will hold your interest and that you might even be excited about. Your attitude towards your topic will come across in your writing or presentation!

Brainstorming is a technique you can use to help you generate ideas. Below are brainstorming exercises and resources to help you come up with research topic ideas.

Brainstorming Topic Ideas

Ask yourself the following questions to help you generate topic ideas:.

- Do you have a strong opinion on a current social or political controversy?

- Did you read or see a news story recently that has interested you?

- Do you have a personal issue, problem or interest that you would like to know more about?

- Is there an aspect of one of your classes that you would like to learn more about?

Finding Topic Ideas

Topic ideas.

Try the resources below to help you get ideas for possible research topics:

- CQ Researcher This link opens in a new window Coverage of the most important issues and controversies of the day, including pro-con analysis. Help Video

- Google News This site provides national and international news on a variety of subjects gathered from over 4,000 sources.

- Article & News Databases Use the Library's Articles and News databases to browse contents of current magazines and newspapers. If you do not know how to browse current issues ask a librarian for help.

Background Information

Read an encyclopedia article on the top two or three topics you are considering. Reading a broad summary enables you to get an overview of the topic and see how your idea relates to broader, narrower, and related issues. If you cant find an article on your topic, ask a librarian for help.

- Gale eBooks This link opens in a new window The Gale Virtual Reference Library contains several business focused encyclopedias such as The Encyclopedia of Management and The Encyclopedia of Emerging Industries which may provide background information on possible topics.

- Article & News Databases Use the Library's Articles and News databases to search for brief articles on your topic ideas.

- SAGE Knowledge This link opens in a new window Hundreds of encyclopedias and handbooks on key topics in the social and behavioral sciences. User Guide

- SAGE Research Methods This link opens in a new window

Ask A Librarian

Email questions to [email protected] .

Available during normal business hours.

LIBRARY HOURS

- Next: Refining Your Topic >>

- Last Updated: Apr 17, 2024 1:45 PM

- URL: https://ggu.libguides.com/research

Research Process

- Getting Started

- Explore: Choose and Develop a Topic

- Refine: Develop a Scholarly Argument

- Search: Identify and Locate Information (OneSearch box)

- Advanced Search

- Evaluate: Who? What? Where? When? Why?

- Write: Putting Your Research to Paper This link opens in a new window

- Research Process Tutorial and Flow Chart

- Grammarly - your writing assistant

- Brainfuse Online Tutoring

Choose and Develop Your Topic

Need an idea, a great idea can come from many places. here are some suggested places to start:, class discussions, assigned readings, topics in the news, browse journals in the field, personal interests.

- "Choosing a Topic" Resources

- Explore Your Topic

- Refine Your Topic

- Choosing a Good Topic Resources This document has links to help you find a topic, research your topic, and focus your topic

- Britannica's ProCon.org Britannica provides pros and cons on debatable issues, with well-researched information on those issues.

- Points of View Reference Source This link opens in a new window This database contains many core topics, each with an overview (objective background / description), point (argument), and counterpoint (opposing argument).

Before you develop your research topic or question, you'll need to do some background research first.

Some good places to find background information:

- Your textbook or class readings

- Encyclopedias and reference books

- Credible websites

- Library databases

Try the library databases below to explore your topic. When you're ready, move on to refining your topic.

Find Background Information

- Gale EBooks This link opens in a new window Gale EBooks is a database of encyclopedias, almanacs, and specialized reference sources for multidisciplinary research.

- Refining Your Topic Learn strategies for selecting and refining your topic by narrowing or broadening it, and how to control the number of results by adding or removing search terms.

- Is there a specific subset of the topic you can focus on?

- Is there a cause and effect relationship you can explore?

- Is there an unanswered question on the subject?

- Can you focus on a specific time period or group of people?

Describe and develop your topic in some detail. Try filling in the blanks in the following sentence, as much as you can:

I want to research ____ (what/who) ____

and ____ (what/who) ____

in ____ (where) ____

during ____ (when) ____

because ____ (why) ____.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Refine: Develop a Scholarly Argument >>

- Last Updated: Apr 28, 2024 3:11 PM

- URL: https://national.libguides.com/research_process

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Importance of Narrowing the Research Topic

Whether you are assigned a general issue to investigate, must choose a problem to study from a list given to you by your professor, or you have to identify your own topic to investigate, it is important that the scope of the research problem is not too broad, otherwise, it will be difficult to adequately address the topic in the space and time allowed. You could experience a number of problems if your topic is too broad, including:

- You find too many information sources and, as a consequence, it is difficult to decide what to include or exclude or what are the most relevant sources.

- You find information that is too general and, as a consequence, it is difficult to develop a clear framework for examining the research problem.

- A lack of sufficient parameters that clearly define the research problem makes it difficult to identify and apply the proper methods needed to analyze it.

- You find information that covers a wide variety of concepts or ideas that can't be integrated into one paper and, as a consequence, you trail off into unnecessary tangents.

Lloyd-Walker, Beverly and Derek Walker. "Moving from Hunches to a Research Topic: Salient Literature and Research Methods." In Designs, Methods and Practices for Research of Project Management . Beverly Pasian, editor. ( Burlington, VT: Gower Publishing, 2015 ), pp. 119-129.

Strategies for Narrowing the Research Topic

A common challenge when beginning to write a research paper is determining how and in what ways to narrow down your topic . Even if your professor gives you a specific topic to study, it will almost never be so specific that you won’t have to narrow it down at least to some degree [besides, it is very boring to grade fifty papers that are all about the exact same thing!].

A topic is too broad to be manageable when a review of the literature reveals too many different, and oftentimes conflicting or only remotely related, ideas about how to investigate the research problem. Although you will want to start the writing process by considering a variety of different approaches to studying the research problem, you will need to narrow the focus of your investigation at some point early in the writing process. This way, you don't attempt to do too much in one paper.

Here are some strategies to help narrow the thematic focus of your paper :

- Aspect -- choose one lens through which to view the research problem, or look at just one facet of it [e.g., rather than studying the role of food in South Asian religious rituals, study the role of food in Hindu marriage ceremonies, or, the role of one particular type of food among several religions].

- Components -- determine if your initial variable or unit of analysis can be broken into smaller parts, which can then be analyzed more precisely [e.g., a study of tobacco use among adolescents can focus on just chewing tobacco rather than all forms of usage or, rather than adolescents in general, focus on female adolescents in a certain age range who choose to use tobacco].

- Methodology -- the way in which you gather information can reduce the domain of interpretive analysis needed to address the research problem [e.g., a single case study can be designed to generate data that does not require as extensive an explanation as using multiple cases].

- Place -- generally, the smaller the geographic unit of analysis, the more narrow the focus [e.g., rather than study trade relations issues in West Africa, study trade relations between Niger and Cameroon as a case study that helps to explain economic problems in the region].

- Relationship -- ask yourself how do two or more different perspectives or variables relate to one another. Designing a study around the relationships between specific variables can help constrict the scope of analysis [e.g., cause/effect, compare/contrast, contemporary/historical, group/individual, child/adult, opinion/reason, problem/solution].

- Time -- the shorter the time period of the study, the more narrow the focus [e.g., restricting the study of trade relations between Niger and Cameroon to only the period of 2010 - 2020].

- Type -- focus your topic in terms of a specific type or class of people, places, or phenomena [e.g., a study of developing safer traffic patterns near schools can focus on SUVs, or just student drivers, or just the timing of traffic signals in the area].

- Combination -- use two or more of the above strategies to focus your topic more narrowly.

NOTE: Apply one of the above strategies first in designing your study to determine if that gives you a manageable research problem to investigate. You will know if the problem is manageable by reviewing the literature on your more narrowed problem and assessing whether prior research is sufficient to move forward in your study [i.e., not too much, not too little]. Be careful, however, because combining multiple strategies risks creating the opposite problem--your problem becomes too narrowly defined and you can't locate enough research or data to support your study.

Booth, Wayne C. The Craft of Research . Fourth edition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2016; Coming Up With Your Topic. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Narrowing a Topic. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Narrowing Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Strategies for Narrowing a Topic. University Libraries. Information Skills Modules. Virginia Tech University; The Process of Writing a Research Paper. Department of History. Trent University; Ways to Narrow Down a Topic. Contributing Authors. Utah State OpenCourseWare.

- << Previous: Reading Research Effectively

- Next: Broadening a Topic Idea >>

- Last Updated: May 25, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Choosing and Refining Topics

When we are given a choice of topics to write on, or are asked to come up with our own topic ideas, we must always make choices that appeal to our own interests, curiosity, and current knowledge. If you decide to write an essay on same sex marriage, for instance, it is obvious that you should make that decision because you are interested in the issue, know something about it already, and/or would like to know more about it. However, because we rarely write solely for our own satisfaction, we must consider matters other than our own interests as we choose topics.

A Definition of a Topic

A topic is the main organizing principle of a discussion, either verbal or written. Topics offer us an occasion for speaking or writing and a focus which governs what we say. They are the subject matter of our conversations, and the avenues by which we arrive at other subjects of conversations. Consider, for instance, a recent class discussion. Although your instructor determined what topic you discussed initially, some students probably asked questions that led to other topics. As the subjects of our discussions lead to related subjects, so do the topics we write about lead to related topics in our academic studies. However, unlike the verbal conversations we have, each individual piece of writing we produce usually focuses on a single topic. Most effective writers learn that when they present a well-defined, focused, and developed topic, they do a better job of holding their readers' attention and presenting appropriate information than if they had not attempted to place boundaries on the subject of their writing.

Arriving at Topics for Writing Assignments

In academic writing, topics are sometimes dictated by the task at hand. Consider, for example, that you must conduct a lab experiment before you can sit down to write a report. Or perhaps you have to run a statistical program to get your data. In these situations, your topic is determined for you: You will write about the results of the work you have completed. Likewise, your instructor may simply hand you a topic to explore or to research. In these situations, you are delivered from both the responsibility and the rewards of choosing your own topic, and your task is to try to develop an interest in what you have been given to write about.

More often, however, you will have a bit more leeway in choosing topics of your own. Sometimes you will be asked to find a topic of interest to you that is grounded in ideas developed in shared class readings and discussions. Other times, your assignment will be anchored even less, and you will be responsible for finding a topic all on your own. Many students find that the more freedom they are given to pursue their own interests, the more intimidated they are by this freedom, and the less certain they are of what really is interesting to them. But writing assignments with open topic options can be excellent opportunities either to explore and research issues that are already concerns for you (and which may even have been topics of earlier writing) or to examine new interests. A well chosen writing topic can lead to the types of research questions that fuel your academic interests for years to come. At the very least, though, topics can be seen as occasions for making your writing relevant and meaningful to your own personal and academic concerns.

How Purpose and Audience Affect the Choice of Topics

Before choosing and narrowing a topic to write about, consider why you are writing and who will read what you write. Your writing purpose and audience often dictate the types of topics that are available to you.

In the workplace, purpose and audience are often defined for you. For instance, you might have to write a memo to a co-worker explaining why a decision was made or compose a letter to a client arguing why the company cannot replace a product. In either case, your purpose and audience are obvious, and your topic is equally evident. As a student, you may have to work a little harder to determine which topics are appropriate for particular purposes and audiences.

Oftentimes, the wording of your assignment sheet will offer clues as to the reasons why you are writing and the audience you are expected to address. Sometimes, when assignment sheets are unclear or when you misunderstand what is expected of you, you will need either to ask your instructor about purpose and audience or to make your own educated guess. However you arrive at the purpose and the audience of your writing, it is important to take these elements into consideration, since they help you to choose and narrow your topic appropriately.

Interpreting the Assignment

Steve Reid, English Professor It's important to circle an assignment's key words and then ask the instructor to clarify what these words mean. Every teacher has a different vocabulary. My students always ask me what I'm looking for when I give an assignment. As a writer, you need to know what the words mean in your field and what they mean to your instructor.

Many times, an assignment sheet or verbal assignment given by an instructor will reveal exactly what you are being asked to do. The first step in reviewing an assignment sheet is to circle key words or verbs, such as "explain," "describe," or "evaluate." Then, once you've identified these words, make sure you understand what your instructor means by them. For example, suppose your instructor asks you to describe the events leading up to World War II. This could mean explain how the events prior to World War II helped bring about the beginning of the war, or list every possible cause you think led to the war, or describe and analyze the events. Inquiring before you start writing can help you determine your writing purpose and the expectations of your intended audience (usually your instructor).

How Purpose Affects Topics

Your purpose helps you to narrow a topic, since it demands particular approaches to a general subject. For example, if you're writing about how state policy affects foreign language study in grades K-12 in Oregon, you could have several different purposes. You may need to explain how the Oregon law came about; that is, what influenced it and who was responsible. Or perhaps you would need to explain the law's effects, how curriculum will be altered, etc. Another purpose might be to evaluate the law and to propose changes. Whatever purpose you decide to adopt will determine the questions which give direction to your topic, and (in the case of a research paper) will suggest the type of information you will need to gather in order to address those questions.

How Audience Affects Topics

Steve Reid, English Professor You have to be careful so your topic is not too narrow for your audience. You don't want readers to say, " Well, so what? I couldn't care less." One the most important roles a topic plays is impacting an audience. If your topic gets too narrow and too focused, it can become too academic or too pedantic. For example, every year at graduation, I watch people laugh when they hear the title of a thesis or dissertation. The students who wrote these documents were very narrowed and focused, but their audiences were very restricted.

Having a clear idea of the audience to whom you are writing will help you to determine an appropriate topic and how to present it. For example, if you're writing about how state policy affects foreign language study in grades K-12 in Oregon, you could have many different audiences. You could be writing for teachers, administrators at a specific school, students whose educational program will be affected by the law, or even the PTA. All of these audiences care about the topic since they are all affected by it. However, for each of them you may need to provide different information and address slightly different questions about this topic. Teachers would want to know why the policy was created and how it will affect what goes on in their classrooms. Parents will want to know what languages their children will be taught and why. Administrators will want to know how this will change the curriculum and what work will be required of them as a result. Knowing your audience requires you to adapt and limit your topic so that you are presenting information appropriate to a specific group of interested readers.

Choosing Workable Topics

Most writers in the workplace don't have to think about what's workable and what's not when they write. Writing topics make themselves obvious, being the necessary outcome of particular processes. For example, meetings inspire memos and minutes; research produces reports; interactions with customers result in letters. As a student writer, your task is often more difficult than this, since topics do not always "find you" this easily.

Finding and selecting topics are oftentimes arduous tasks for the writer. Sometimes you will find yourself facing the "blank page" or "empty screen" dilemma, lacking topic ideas entirely. Other times you will have difficulties making your ideas fit a particular assignment you have been given. This section on "Choosing a Workable Topic" addresses both of these problems, offering both general strategies for generating topic ideas and strategies for finding topics appropriate to particular types of writing assignments that students frequently encounter.

How to Find a Topic

Don Zimmerman, Journalism and Technical Communication Professor I look at topics from a problem solving perspective and scientific method. Topics emerge from writers working on the job when they're in the profession, following major trends, developments, issues, etc. From the scientific perspective, topics emerge based on solid literature reviews and developing an understanding of the paradigm. From these then come the specific problems/topics/subjects that professionals or scientists address. Writers generate topics from their professional expertise, their understanding of the issues in their respective disciplines, and their understanding the science that has gone before them.

While your first impulse may be to dash off to the library to dig through books and journals once you've received an assignment, you might also consider other information sources available to you.

Related Information: Making Use of Computer Sources

One valuable source of topic ideas is an Internet search. Many sites can provide you with current perspectives on a subject and can lead you to other relevant sites. You can also find and join newsgroups where your general subject or topic is discussed daily. This will allow you to ask questions of experts, as well as to read what issues are important.

Related Information: Making Use of Library Sources

It is always helpful, particularly in the case of writing assignments which demand research, to visit the library and talk to a reference librarian when generating topic ideas. This way, you not only get to discuss your topic ideas with another expert, but you will also have more resources pointed out to you. There is usually a wealth of journals, reference books, and online resources related to your topic area(s) that you may not even know exist.

Related Information: Talking to Others Around You

The people around you are often some of the best sources of information available to you. It is always valuable to talk informally about your assignment and any topic ideas you have with classmates, friends, family, tutors, professionals in the field, or any other interested and/or knowledgeable people. Remember, too, that a topic is not a surprise gift that must be kept from your instructor until you hand in your paper. Instructors are almost always happy to discuss potential topics with a student once he or she has an idea or two, and getting response to your work early in the writing process whenever possible is a good plan. Discussing your topic ideas in these ways may lead you to other ideas, and eventually to a well-defined topic.

Subjects and Topics

Most topic searches start with a subject. For example, you're interested in writing about languages, and even more specifically, foreign languages. This is a general subject. Within a general subject, you'll find millions of topics. Not only about every foreign language ever spoken, but also about hundreds of issues affecting foreign languages. But keep in mind that a subject search is always a good place to start.

Every time you use Yahoo or other Internet search engines, or even SAGE at the CSU library, you conduct a subject search. These search devices allow you to review many topics within a broad subject area. While it's beneficial to conduct subject searches, because you never know what valuable information you'll uncover, a subject always needs to be narrowed to a specific topic. This way, you can avoid writing a lengthy book and focus instead on the short research paper you've been assigned.

Starting With What You Know

Kate Kiefer, English Professor Most often the occasion dictates the topic for the writing done outside academe. But as a writer in school, you do sometimes have to generate topics. If you need help determining a topic, create an authority list of things you have some expertise in or a general list of areas you know something about and are interested in. Then, you can make this list more specific by considering how much you know and care about these ideas and what the target audience is probably interested in reading about.

In looking for writing topics, the logical first step is to consider issues or subjects which have concerned you in the past, either on the basis of life experience or prior writing/research. If you are a journal writer, look to your journal for ideas. If not, think about writing you have done for other writing assignments or for other classes. Though it is obviously not acceptable to recycle old essays you have written before, it is more than acceptable (even advisable) to return to and to extend topics you have written about in the past. Returning to the issues that concern you perennially is ultimately what good scholarship is all about.

Related Information: Choosing Topics You Want to Know More About

Even though your personal experience and prior knowledge are good places to start when looking for writing topics, it is important not to rule out those topics about which you know very little, and would like to know more. A writing assignment can be an excellent opportunity to explore a topic you have been wanting to know more about, even if you don't have a strong base knowledge to begin with. This type of topic would, of course, require more research and investigation initially, but it would also have the benefit of being compelling to you by virtue of its "newness."

Related Information: How to Pull Topics from Your Personal Experience

It is a good idea to think about how elements of your own life experience and environment could serve as topics for writing, even if you have never thought of them in that way. Think about the topics of recent conversations you have had, events in your life that are significant to you, problems in your workplace, family issues, matters having to do with college or campus life, or current events that evoke response from you. Taking a close look at the issues in your immediate environment is a good place to start in writing, even if those issues seem to you at first to be unworthy of your writing focus. Not all writing assignments have a personal dimension, but our interests and concerns are always, at their roots, personal.

General Strategies for Coming Up With Topics

Before attempting to choose or narrow a topic, you need to have some ideas to choose from. This can be a problem if you are suffering from the "blank page or screen" syndrome, and have not even any initial, general ideas for writing topics.

Brainstorming

As writers, some of our best ideas occur to us when we are thinking in a very informal, uninhibited way. Though we often think of brainstorming as a way for groups to come up with ideas, it is a strategy that individual writers can make use of as well. Simply put, brainstorming is the process of listing rough thoughts (in any form they occur to you: words, phrases, or complete sentences) that are connected (even remotely) to the writing assignment you have before you or the subject area you already have in mind. Brainstorming works best when you give yourself a set amount of time (perhaps five or ten minutes), writing down anything that comes to mind within that period of time, and resisting the temptation to criticize or polish your own ideas as they hit the page. There is time for examination and polishing when the five or ten minutes are over.

Freewriting

Freewriting is a technique much like brainstorming, only the ideas generated are written down in paragraph rather than list form. When you freewrite, you allow yourself a set amount of time (perhaps five or ten minutes), and you write down any and every idea that comes to mind as if you are writing a timed essay. However, your freewrite is unlikely to read like an organized essay. In fact, it shouldn't read that way. What is most important about freewriting is that you write continuously, not stopping to check your spelling, to find the right word, or even to think about how your ideas are fitting together. If you are unable to think of something to write, simply jot out, "I can't think of anything to write now," and go on. At the end of your five or ten minutes, reread what you have written, ignore everything that seems unimportant or ridiculous, and give attention to whatever ideas you think are worth pursuing. If you are able to avoid checking yourself while you are writing for that short time, you will probably be surprised at the number of ideas that you already have.

Clustering is a way of visually "mapping" your ideas on paper. It is a technique which works well for people who are able to best understand relationships between ideas by seeing the way they play themselves out spatially. (If you prefer reading maps to reading written directions, clustering may be the strategy for you.) Unlike formal outlining, which tends to be very linear, clustering allows you to explore the way ideas sprawl in different directions. When one thought leads to another, you can place that idea on the "map" in its appropriate place. And if you want to change its position later, and connect it with another idea, you can do so. (It is always a good idea to use a pencil rather than a pen for clustering, for this very reason.)

This is a good strategy not only for generating ideas, but also for determining how much you have to say about a topic (or topics), and how related or scattered your ideas are.

Related Information: Example of Brainstorming

Ideas on a Current Issue:

- multiculturalism

- training of teachers

- teaching strategies

- cultural difference in the classroom

- teaching multicultural texts

- language issues

- English only

- assimilation, checking cultural identity at the door

- home language/dialect as intentionally different from school language

- How many languages can we teach? (How multi-lingual must teachers be?)

- Is standard English really "standard"?

- success in school

- statistics on students who speak "non-English" languages or established dialects

- the difference between a dialect and a language

- Ebonics v. bi-lingual education

Related Information: Example of Freewriting

Problem: Development of Small Towns in the Rocky Mountain Region

When I grew up in Anyoldtown, New Mexico, it was a small town in the smallest sense: no movie theaters, no supermarkets, nothing. We had to go into town for the things we needed. Land sold for $2000 an acre. Now it sells for about $50,000 an acre. Anyoldtown was also primarily hispanic, and the families who lived there had very little. Now the people who live there are mostly white and almost exclusively professionals: doctors, lawyers, stockbrokers, and an endless number of people who have money that seems to have come from nowhere. There are good things to be had there now: good restaurants, good coffee, and all the other things that come along with Yuppie invasion. But those things were had at quite a cost. People who used to live in Anyoldtown when I was a kid can no longer afford to pay property taxes. I can't think of anything else to write now. Oh, yes...these people made a killing off the sale of their land and properties, but they had to give up the places they had lived all their lives. However, by the time they sold, Anyoldtown was no longer the place where they had lived all their lives anyway.

Strategies for Finding Topics Appropriate to Particular Types of Assignments

Sometimes your ways of generating topics will depend on the type of writing assignment you have been given. Here are some ideas of strategies you can use in finding topics for some of the more common types of writing assignments:

Essays Based on Personal Experience

Essays responding to or interpreting texts.

- Essays in Which You Take a Position on an Issue (Argument)

Essays Requiring Research

Essays in which you evaluate, essays in which you propose solutions to problems.

The great challenge of using personal experience in essays is trying to remember the kinds of significant events, places, people, or objects that would prove to be interesting and appropriate topics for writing. Brainstorming, freewriting, or clustering ideas in particular ways can give you a starting point.

Here are a few ways that you might trigger your memory:

Interview people you've known for a long time.Family members, friends, and other significant people in your life can remember important details and events that you haven't thought about for years.

Try to remember events from a particular time in your life. Old yearbooks, journals, and newspapers and magazines can help to trigger some of these memories.

Think about times of particular fulfillment or adversity. These "extremes" in your experience are often easily recalled and productively discussed. When have you had to make difficult choices, for instance? When have you undergone ethical struggles? When have you felt most successful?

Think about the groups you have encountered at various times in your life. When have you felt most like you belonged to or were excluded from groups of people: your family, cliques in school, clubs, "tracked" groups in elementary school, religious groups, or any other community/organization you have had contact with?

Think about the people or events that "changed your life." What are the forces that have most significantly influenced and shaped you? What are the circumstances surrounding academic, career, or relationship choices that you have made? What changes have you dealt with that have been most painful or most satisfying?

Try to remember any "firsts" in your experience.What was your first day of high school like? What was it like to travel far from home for the first time? What was your first hobby or interest as a child? What was the first book you checked out of the library? These "firsts," when you are able to remember them, can prove to have tremendous significance.

One word of caution on writing about personal experience: Keep in mind that any essay you write for a class will most likely be read by others, and will probably be evaluated on criteria other than your topic's importance to you. Never feel like you need to "confess," dredge up painful memories, or tell stories that are uncomfortable to you in academic writing. Save these topics for your own personal journal unless you are certain that you are able to distance yourself from them enough to handle the response that comes from instructors (and sometimes from peers).

Students are often asked to respond to or interpret essays, articles, books, stories, poems, and a variety of other texts. Sometimes your instructor will ask you to respond to one particular reading, other times you will have a choice of class readings, and still other times you will need to choose a reading on your own.

If you are given a choice of texts to respond to or to interpret, it is a good idea to choose one which is complex enough to hold your interest in the process of careful examination. It is not necessarily a problem if you do not completely understand a text on first reading it. What matters is that it challenges, intrigues, and/or evokes response from you in some way.

Related Information: Writing in the Margins of Texts

Many of us were told at some point in our schooling never to write in books. This makes sense in the case of books which don't belong to us (like library books or the dusty, tattered, thirty year-old copies of Hamlet distributed to us in high school). But in the case of books and photocopies which we have made our own, writing in the margins can be one of the most productive ways to begin the writing process.

As you read, it is a good idea to make a habit of annotating , or writing notes in the margins. Your notes could indicate places in the text which remind you of experiences you have had or of other texts you have read. They could point out questions that you have, points of agreement or disagreement, or moments of complete confusion. Annotations begin a dialogue between you and the text you have before you, documenting your first (and later) responses, and they are valuable when you attempt at a later time to write about that text in a particular way.

Essays in Which You Take a Position on an Issue

One of the most common writing assignments given is some variation on the Arguing Essay, in which students are asked to take a position on a controversial issue. There are two challenges involved in finding topics for argument. One challenge is identifying a topic that you are truly interested in and concerned about, enough so that whatever research is required will be engrossing (or at the very least, tolerable), and not a tedious, painful ordeal. In other words, you want to try to avoid arriving at the "So what?" point with your own topic. The other challenge is in making sure that your audience doesn't respond, "So what?" in reading your approach to your topic. You can avoid this by making sure that the questions you are asking and addressing are current and interesting.

Related Information: Examining Social Phenomena and Trends

In The St. Martin's Guide to Writing , Third Edition, Rise B. Axelrod and Charles R. Cooper discuss the importance of looking toward social phenomena and trends for sources of argument topics. A phenomenon , they explain, is "something notable about the human condition or the social order" (314). A few of the examples of phenomena that they list are difficulties with parking on college campuses, negative campaigning in politics, popular artistic or musical styles, and company loyalty. A trend , on the other hand, is "a significant change extending over many months or years" (314). Some trends they list are the decline of Communism, diminishing concern over world hunger, increased practice of home schooling, and increased legitimacy of pop art. Trying to think in terms of incidental, current social phenomena or long-term, gradual social trends is a good way of arriving at workable topics for essays requiring you to take a position.

Related Information: Making Sure Your Approach to Your Topic is Current and Interesting

In choosing a topic for an arguing essay, it is important to get a handle not only on what is currently being debated, but how it is being debated. In other words, it is necessary to learn what questions are currently being asked about certain topics and why. In order to avoid the "so what" dilemma, you want to approach your topic in a way that is not simplistic, tired, outdated, or redundant. For example, if you are looking at the relationship of children to television, you probably would want to avoid a topic like "the effects of t.v. violence on children" (which has been beaten to death over the years) in favor of a topic like "different toy marketing strategies for young male v.s. female viewers of Saturday morning cartoons" (a topic that seems at least a bit more original).

As a student writer, you are usually not asked to break absolutely new ground on a topic during your college career. However, you are expected to try to find ground that is less rather than more trampled when finding and approaching writing topics.

Trying to think in terms of incidental, current social phenomena or long-term, gradual social trends is a good way of arriving at workable topics for essays requiring you to take a position.

Related Information: Sources of Topics

Looking to Your Own Writing

When trying to rediscover the issues which have concerned you in the past, go back to journal entries (if you are a journal writer) or essays that you have written before. As you look through this formal and informal writing, consider whether or not these issues still concern you, and what (specifically) you now have to say about them. Are these matters which would concern readers other than yourself, or are they too specific to your own life to be interesting and controversial to a reading audience? Is there a way to give a "larger" significance to matters of personal concern? For example, if you wrote in your journal that you were unhappy with a particular professor's outdated teaching methods, could you turn that idea into a discussion of the downfalls of the tenure system? If you were frustrated with the way that your anthropology instructor dismissed your comment about the ways that "primitive" women are discussed, could you think of that problem in terms of larger gender issues? Sometimes your frustrations and mental conflicts are simply your own gripes, but more often than not they can be linked with current and widely debated issues.

Looking to Your Other Classes

When given an assignment which asks you to work with a controversial issue, always try to brainstorm points of controversy that you recall from current or past courses. What are people arguing about in the various disciplines? Sometimes these issues will seem irrelevant because they appear only to belong to those other disciplines, but there are oftentimes connections that can be made. For example, perhaps you have been asked in a communications class to write an essay on a language issue. You might remember that in a computer class on information systems, your class debated whether or not Internet news groups are really diverse or not. You might begin to think about the reasons why news groups are (or aren't) diverse, thinking about the way that language is used.

Reading Newspapers and Magazines

If you are not already an avid newspaper and magazine reader, become one for a week. Pore over the different sections: news, editorials, sports, and even cartoons. Look for items that connect with your own life experiences, and pay attention to those which evoke some strong response from you for one reason or another. Even if an issue that you discover in a newspaper or magazine doesn't prove to be a workable topic, it might lead you to other topic ideas.

Interviewing the People Around You

If you are at a loss to find an issue that lights a fire under you, determine what fires up your friends, family members, and classmates. Think back to heated conversations you have had at the dinner table, or conduct interviews in which you ask the people around you what issues impact their lives most directly. Because you share many experiences and contexts with these people, it is likely that at least some of the issues that concern them will also concern you.

Using the Internet

It is useful to browse the Internet for current, controversial issues. Spend some time surfing aimlessly, or wander through news groups to see what is being discussed. Using the Internet can be one of the best ways to determine what is immediately and significantly controversial.

Although some essays that students are asked to write are to be based solely on their own thoughts and experience, oftentimes (particularly in upper level courses) writing assignments require research. When scoping out possible research topics, it is important to remember to choose a topic which will sustain your interest throughout the research and writing process. The best research topics are those which are complex enough that they offer opportunities for various research questions. You want to avoid choosing a topic that could bore you easily, or that is easily researched but not very interesting to you.

As always, it is good to start searching for a topic within your personal interests and previous writing. You might want to choose a research topic that you have pursued before and do additional research, or you might want to select a topic about which you would like to know more. More than anything, writers must remember that research will often carry them in different directions than they intend to go, and that they must be flexible enough to acknowledge that their research questions and topics must sometimes be adjusted or abandoned. To read more on narrowing and adjusting a research topic, see the section in this guide on Research Considerations.

Related Information: Flexibility in Research

As you conduct your research, it is important to keep in mind that the questions you are asking about your topic (and oftentimes, the topic itself) will probably change slightly. Sometimes you are forced to acknowledge that there is too much or too little information available on the topic you have chosen. Other times, you might decide that the approach you were originally taking is not as interesting to you as others you have found. For instance, you might start with a topic like "foreign language studies in grades K-12 in Oregon," and in the process of your reading you might find that you are really more interested in "bilingual education in rural Texas." Still other times, you might find that the claim you were attempting to make about your topic is not arguable, or is just wrong.

Our research can carry us in directions that we don't always foresee, and part of being a good researcher is maintaining the flexibility necessary to explore those directions when they present themselves.

Related Information: How Research Narrows Topics

By necessity, most topics narrow themselves as you read more and more about them. Oftentimes writers come up with topics that they think will be sufficiently narrow and engaging--a topic like "multiculturalism and education," for instance--and discover through their initial reading that there are many different avenues they could take in examining the various aspects of this broad issue. Although such discoveries are often humbling and sometimes intimidating, they are also a necessary part of any effective research process. You can take some comfort in knowing that you do not always need to have your topic narrowed to its final form before you begin researching. The sources you read will help you to do the necessary narrowing and definition of your focus.

Related Information: Research Topics and Writing Assignments

When you are choosing a research topic, it is important to be realistic about the time and space limitations that your assignment dictates. If you are writing a graduate thesis or dissertation, for instance, you might be able to research a topic as vast and as time-honored as "the portrayal of women in the poetry of William Blake." But if your assignment asks you to produce a five-page essay by next Tuesday, you might want to focus on something a bit more accessible, like "the portrayal of women in Blake's `The Visions of the Daughters of Albion.'"

Related Information: Testing Research Topics

Early in your research and writing process, after you have found a somewhat narrow avenue into your topic, put the topic to the test to see if you really want to pursue it further in research. Rise B. Axelrod and Charles R. Cooper, in The St. Martin's Guide to Writing , Third Edition, suggest some questions writers might ask themselves when deciding whether or not a research topic is workable: