Home Blog Presentation Ideas How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

How to Create and Deliver a Research Presentation

Every research endeavor ends up with the communication of its findings. Graduate-level research culminates in a thesis defense , while many academic and scientific disciplines are published in peer-reviewed journals. In a business context, PowerPoint research presentation is the default format for reporting the findings to stakeholders.

Condensing months of work into a few slides can prove to be challenging. It requires particular skills to create and deliver a research presentation that promotes informed decisions and drives long-term projects forward.

Table of Contents

What is a Research Presentation

Key slides for creating a research presentation, tips when delivering a research presentation, how to present sources in a research presentation, recommended templates to create a research presentation.

A research presentation is the communication of research findings, typically delivered to an audience of peers, colleagues, students, or professionals. In the academe, it is meant to showcase the importance of the research paper , state the findings and the analysis of those findings, and seek feedback that could further the research.

The presentation of research becomes even more critical in the business world as the insights derived from it are the basis of strategic decisions of organizations. Information from this type of report can aid companies in maximizing the sales and profit of their business. Major projects such as research and development (R&D) in a new field, the launch of a new product or service, or even corporate social responsibility (CSR) initiatives will require the presentation of research findings to prove their feasibility.

Market research and technical research are examples of business-type research presentations you will commonly encounter.

In this article, we’ve compiled all the essential tips, including some examples and templates, to get you started with creating and delivering a stellar research presentation tailored specifically for the business context.

Various research suggests that the average attention span of adults during presentations is around 20 minutes, with a notable drop in an engagement at the 10-minute mark . Beyond that, you might see your audience doing other things.

How can you avoid such a mistake? The answer lies in the adage “keep it simple, stupid” or KISS. We don’t mean dumbing down your content but rather presenting it in a way that is easily digestible and accessible to your audience. One way you can do this is by organizing your research presentation using a clear structure.

Here are the slides you should prioritize when creating your research presentation PowerPoint.

1. Title Page

The title page is the first thing your audience will see during your presentation, so put extra effort into it to make an impression. Of course, writing presentation titles and title pages will vary depending on the type of presentation you are to deliver. In the case of a research presentation, you want a formal and academic-sounding one. It should include:

- The full title of the report

- The date of the report

- The name of the researchers or department in charge of the report

- The name of the organization for which the presentation is intended

When writing the title of your research presentation, it should reflect the topic and objective of the report. Focus only on the subject and avoid adding redundant phrases like “A research on” or “A study on.” However, you may use phrases like “Market Analysis” or “Feasibility Study” because they help identify the purpose of the presentation. Doing so also serves a long-term purpose for the filing and later retrieving of the document.

Here’s a sample title page for a hypothetical market research presentation from Gillette .

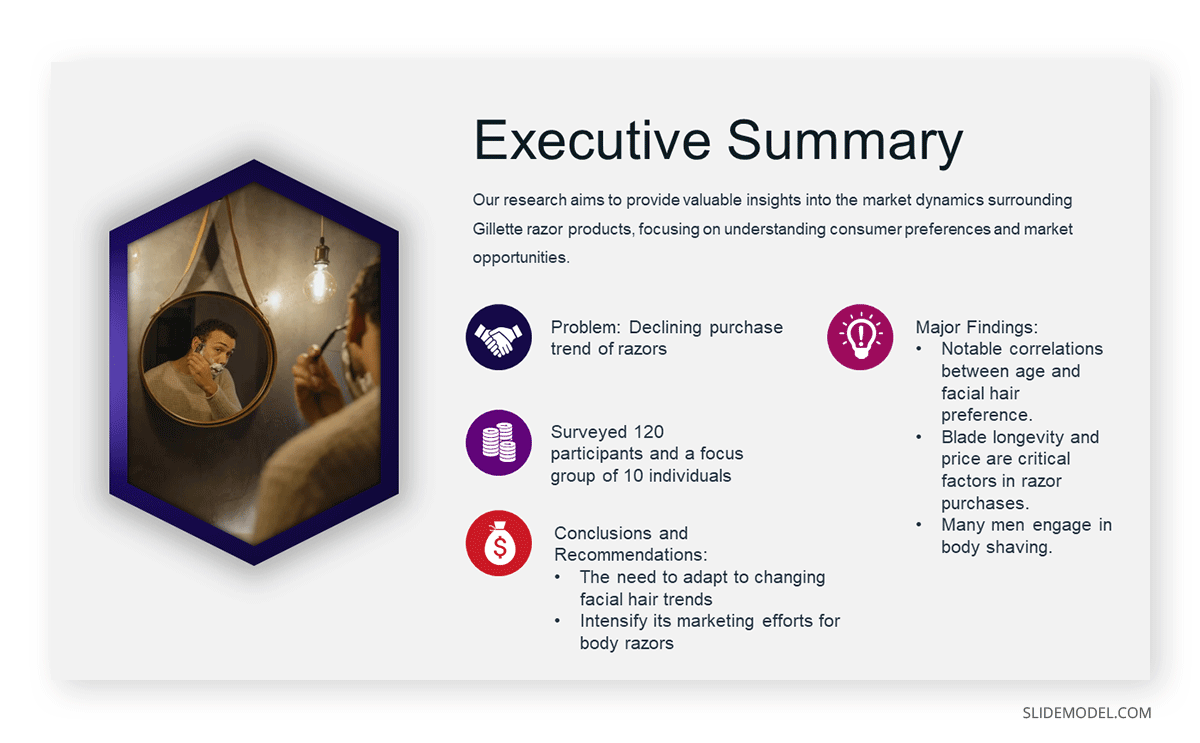

2. Executive Summary Slide

The executive summary marks the beginning of the body of the presentation, briefly summarizing the key discussion points of the research. Specifically, the summary may state the following:

- The purpose of the investigation and its significance within the organization’s goals

- The methods used for the investigation

- The major findings of the investigation

- The conclusions and recommendations after the investigation

Although the executive summary encompasses the entry of the research presentation, it should not dive into all the details of the work on which the findings, conclusions, and recommendations were based. Creating the executive summary requires a focus on clarity and brevity, especially when translating it to a PowerPoint document where space is limited.

Each point should be presented in a clear and visually engaging manner to capture the audience’s attention and set the stage for the rest of the presentation. Use visuals, bullet points, and minimal text to convey information efficiently.

3. Introduction/ Project Description Slides

In this section, your goal is to provide your audience with the information that will help them understand the details of the presentation. Provide a detailed description of the project, including its goals, objectives, scope, and methods for gathering and analyzing data.

You want to answer these fundamental questions:

- What specific questions are you trying to answer, problems you aim to solve, or opportunities you seek to explore?

- Why is this project important, and what prompted it?

- What are the boundaries of your research or initiative?

- How were the data gathered?

Important: The introduction should exclude specific findings, conclusions, and recommendations.

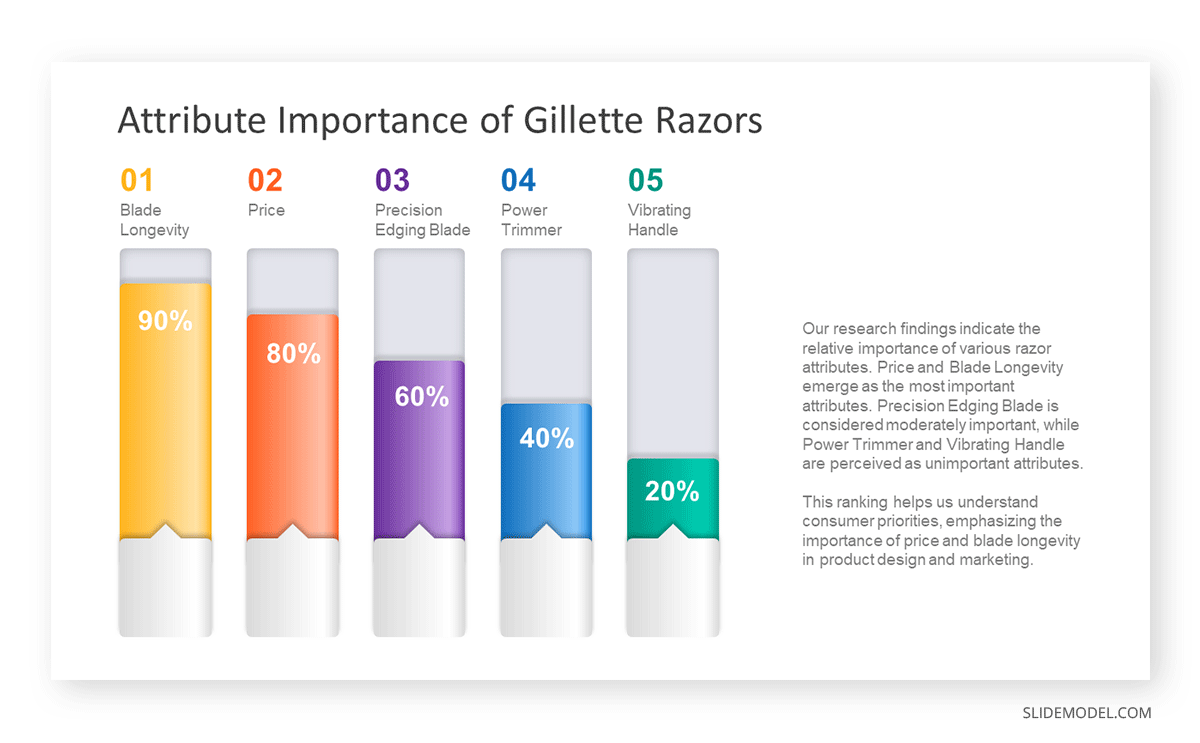

4. Data Presentation and Analyses Slides

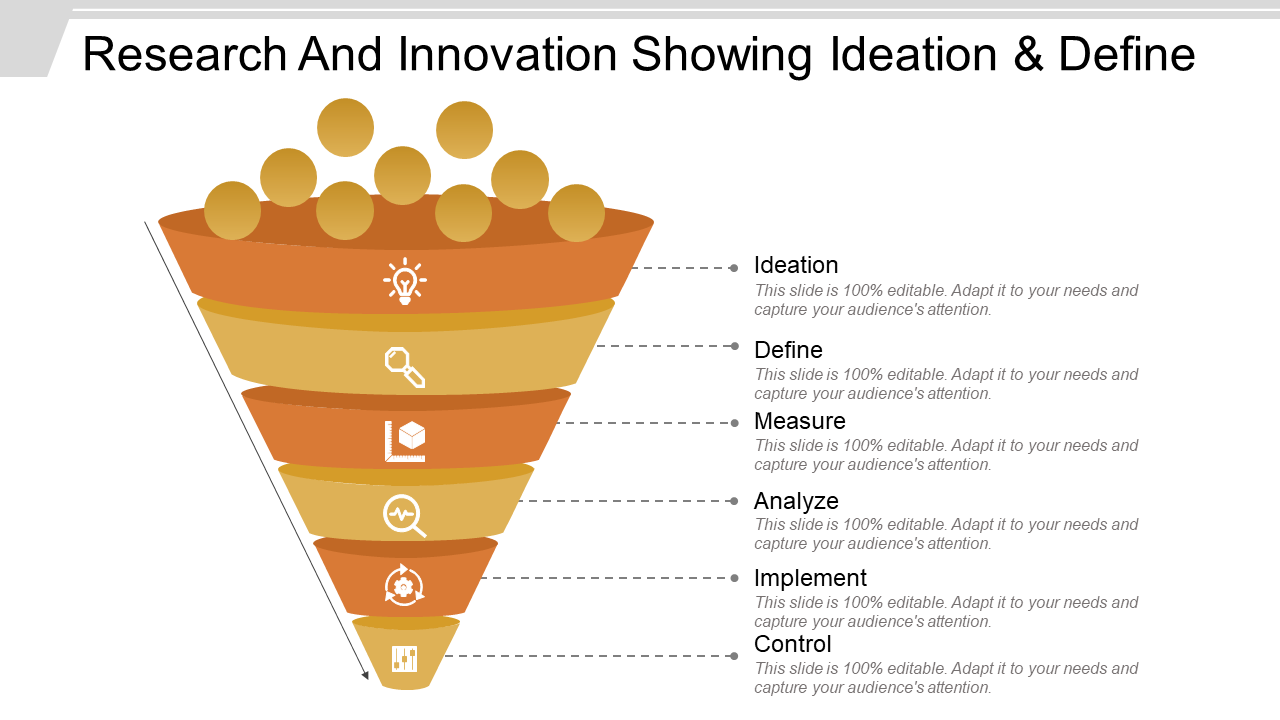

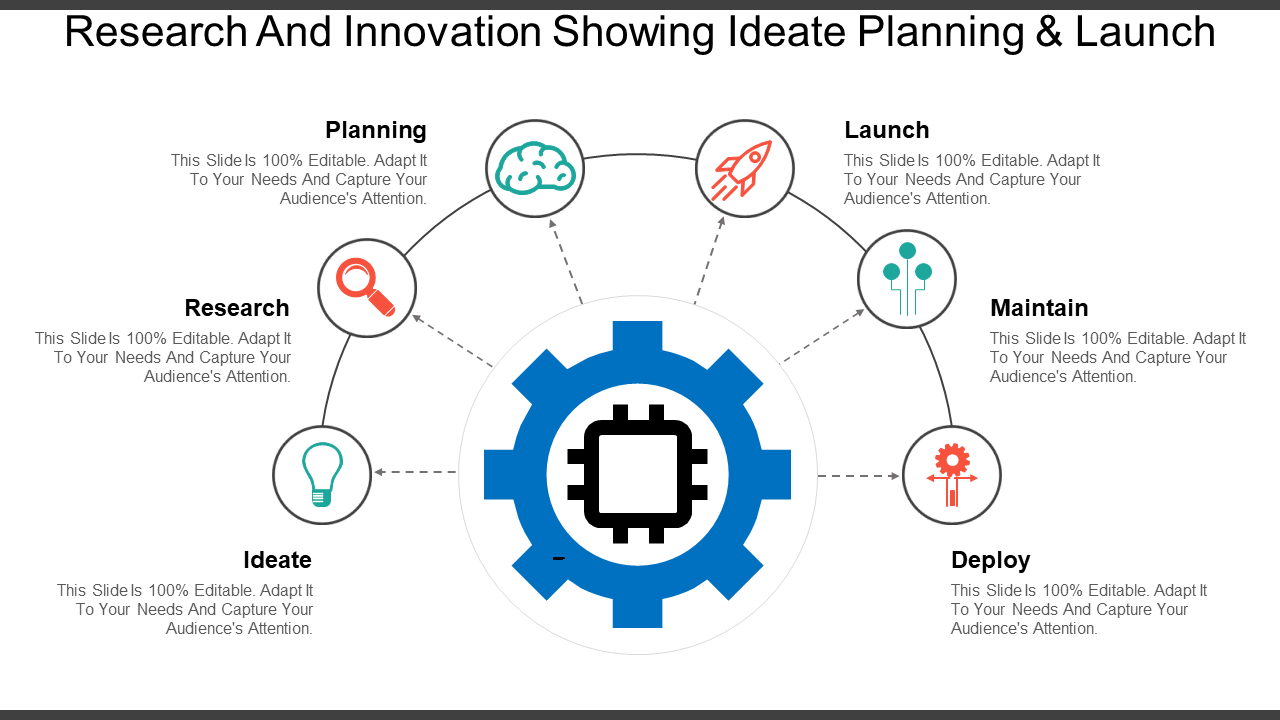

This is the longest section of a research presentation, as you’ll present the data you’ve gathered and provide a thorough analysis of that data to draw meaningful conclusions. The format and components of this section can vary widely, tailored to the specific nature of your research.

For example, if you are doing market research, you may include the market potential estimate, competitor analysis, and pricing analysis. These elements will help your organization determine the actual viability of a market opportunity.

Visual aids like charts, graphs, tables, and diagrams are potent tools to convey your key findings effectively. These materials may be numbered and sequenced (Figure 1, Figure 2, and so forth), accompanied by text to make sense of the insights.

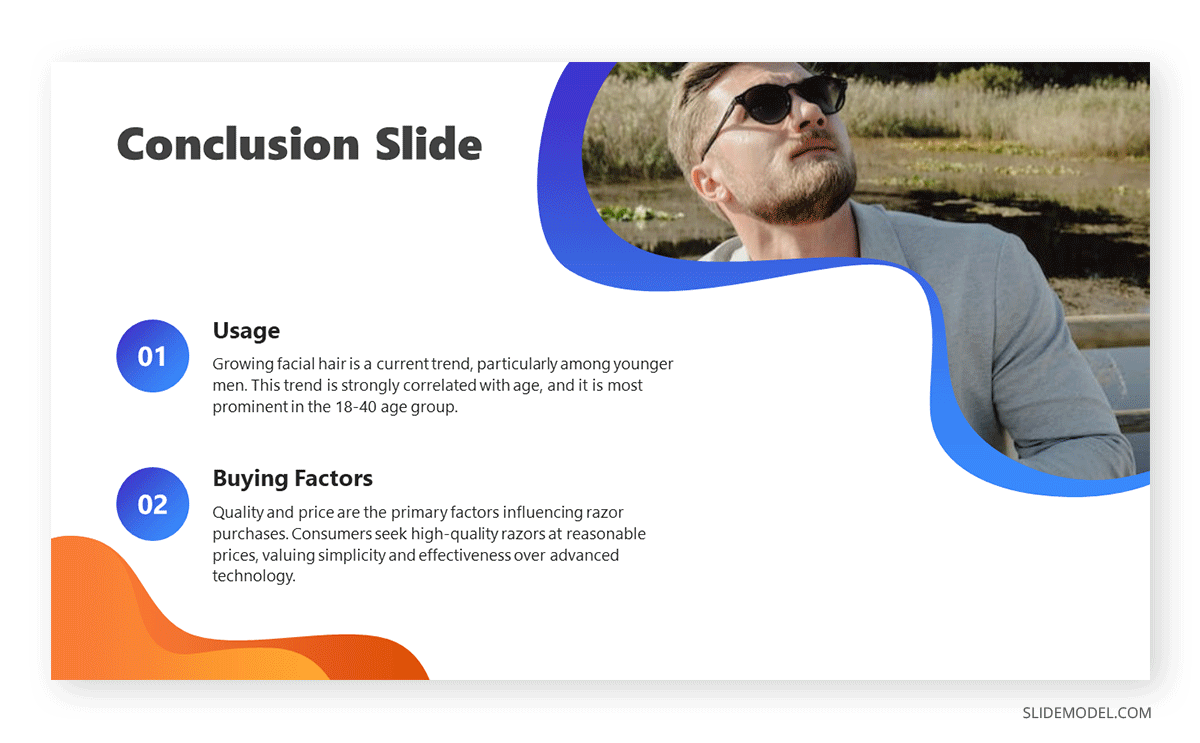

5. Conclusions

The conclusion of a research presentation is where you pull together the ideas derived from your data presentation and analyses in light of the purpose of the research. For example, if the objective is to assess the market of a new product, the conclusion should determine the requirements of the market in question and tell whether there is a product-market fit.

Designing your conclusion slide should be straightforward and focused on conveying the key takeaways from your research. Keep the text concise and to the point. Present it in bullet points or numbered lists to make the content easily scannable.

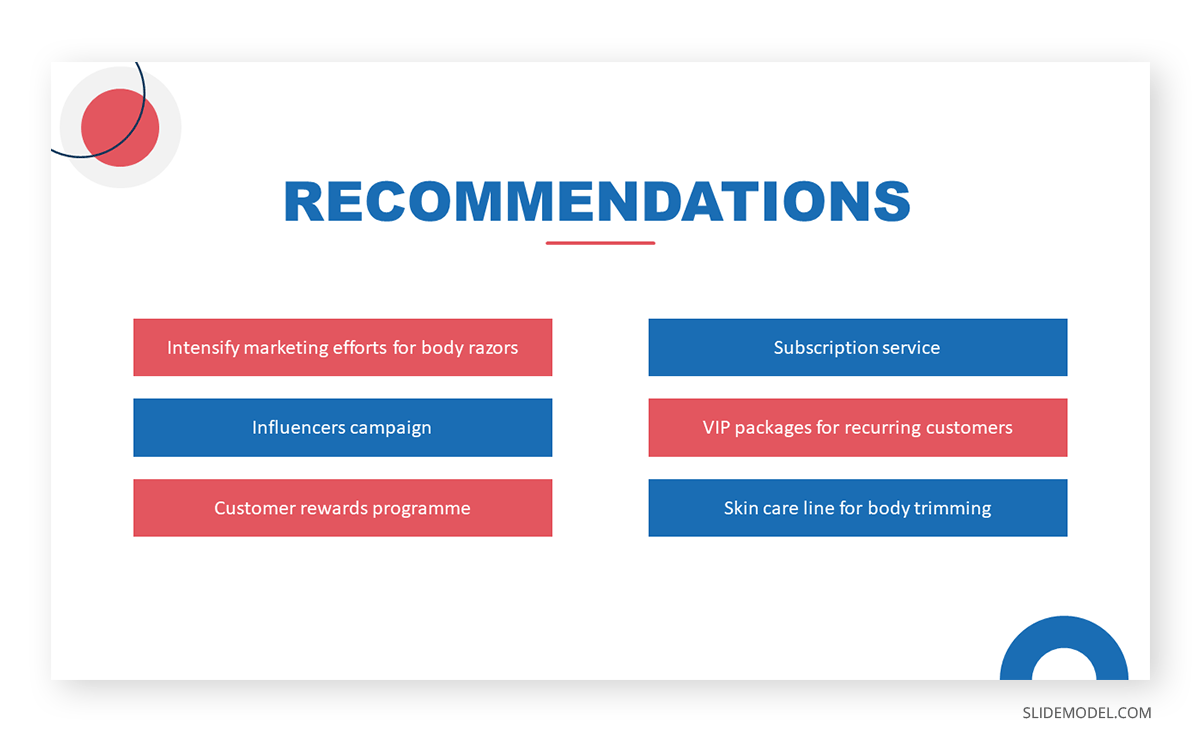

6. Recommendations

The findings of your research might reveal elements that may not align with your initial vision or expectations. These deviations are addressed in the recommendations section of your presentation, which outlines the best course of action based on the result of the research.

What emerging markets should we target next? Do we need to rethink our pricing strategies? Which professionals should we hire for this special project? — these are some of the questions that may arise when coming up with this part of the research.

Recommendations may be combined with the conclusion, but presenting them separately to reinforce their urgency. In the end, the decision-makers in the organization or your clients will make the final call on whether to accept or decline the recommendations.

7. Questions Slide

Members of your audience are not involved in carrying out your research activity, which means there’s a lot they don’t know about its details. By offering an opportunity for questions, you can invite them to bridge that gap, seek clarification, and engage in a dialogue that enhances their understanding.

If your research is more business-oriented, facilitating a question and answer after your presentation becomes imperative as it’s your final appeal to encourage buy-in for your recommendations.

A simple “Ask us anything” slide can indicate that you are ready to accept questions.

1. Focus on the Most Important Findings

The truth about presenting research findings is that your audience doesn’t need to know everything. Instead, they should receive a distilled, clear, and meaningful overview that focuses on the most critical aspects.

You will likely have to squeeze in the oral presentation of your research into a 10 to 20-minute presentation, so you have to make the most out of the time given to you. In the presentation, don’t soak in the less important elements like historical backgrounds. Decision-makers might even ask you to skip these portions and focus on sharing the findings.

2. Do Not Read Word-per-word

Reading word-for-word from your presentation slides intensifies the danger of losing your audience’s interest. Its effect can be detrimental, especially if the purpose of your research presentation is to gain approval from the audience. So, how can you avoid this mistake?

- Make a conscious design decision to keep the text on your slides minimal. Your slides should serve as visual cues to guide your presentation.

- Structure your presentation as a narrative or story. Stories are more engaging and memorable than dry, factual information.

- Prepare speaker notes with the key points of your research. Glance at it when needed.

- Engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and asking rhetorical questions.

3. Don’t Go Without Handouts

Handouts are paper copies of your presentation slides that you distribute to your audience. They typically contain the summary of your key points, but they may also provide supplementary information supporting data presented through tables and graphs.

The purpose of distributing presentation handouts is to easily retain the key points you presented as they become good references in the future. Distributing handouts in advance allows your audience to review the material and come prepared with questions or points for discussion during the presentation.

4. Actively Listen

An equally important skill that a presenter must possess aside from speaking is the ability to listen. We are not just talking about listening to what the audience is saying but also considering their reactions and nonverbal cues. If you sense disinterest or confusion, you can adapt your approach on the fly to re-engage them.

For example, if some members of your audience are exchanging glances, they may be skeptical of the research findings you are presenting. This is the best time to reassure them of the validity of your data and provide a concise overview of how it came to be. You may also encourage them to seek clarification.

5. Be Confident

Anxiety can strike before a presentation – it’s a common reaction whenever someone has to speak in front of others. If you can’t eliminate your stress, try to manage it.

People hate public speaking not because they simply hate it. Most of the time, it arises from one’s belief in themselves. You don’t have to take our word for it. Take Maslow’s theory that says a threat to one’s self-esteem is a source of distress among an individual.

Now, how can you master this feeling? You’ve spent a lot of time on your research, so there is no question about your topic knowledge. Perhaps you just need to rehearse your research presentation. If you know what you will say and how to say it, you will gain confidence in presenting your work.

All sources you use in creating your research presentation should be given proper credit. The APA Style is the most widely used citation style in formal research.

In-text citation

Add references within the text of your presentation slide by giving the author’s last name, year of publication, and page number (if applicable) in parentheses after direct quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

The alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (Smith, 2020, p. 27).

If the author’s name and year of publication are mentioned in the text, add only the page number in parentheses after the quotations or paraphrased materials. As in:

According to Smith (2020), the alarming rate at which global temperatures rise directly impacts biodiversity (p. 27).

Image citation

All images from the web, including photos, graphs, and tables, used in your slides should be credited using the format below.

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Image.” Website Name, Day Mo. Year, URL. Accessed Day Mo. Year.

Work cited page

A work cited page or reference list should follow after the last slide of your presentation. The list should be alphabetized by the author’s last name and initials followed by the year of publication, the title of the book or article, the place of publication, and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. New York, NY: ABC Publications.

When citing a document from a website, add the source URL after the title of the book or article instead of the place of publication and the publisher. As in:

Smith, J. A. (2020). Climate Change and Biodiversity: A Comprehensive Study. Retrieved from https://www.smith.com/climate-change-and-biodiversity.

1. Research Project Presentation PowerPoint Template

A slide deck containing 18 different slides intended to take off the weight of how to make a research presentation. With tons of visual aids, presenters can reference existing research on similar projects to this one – or link another research presentation example – provide an accurate data analysis, disclose the methodology used, and much more.

Use This Template

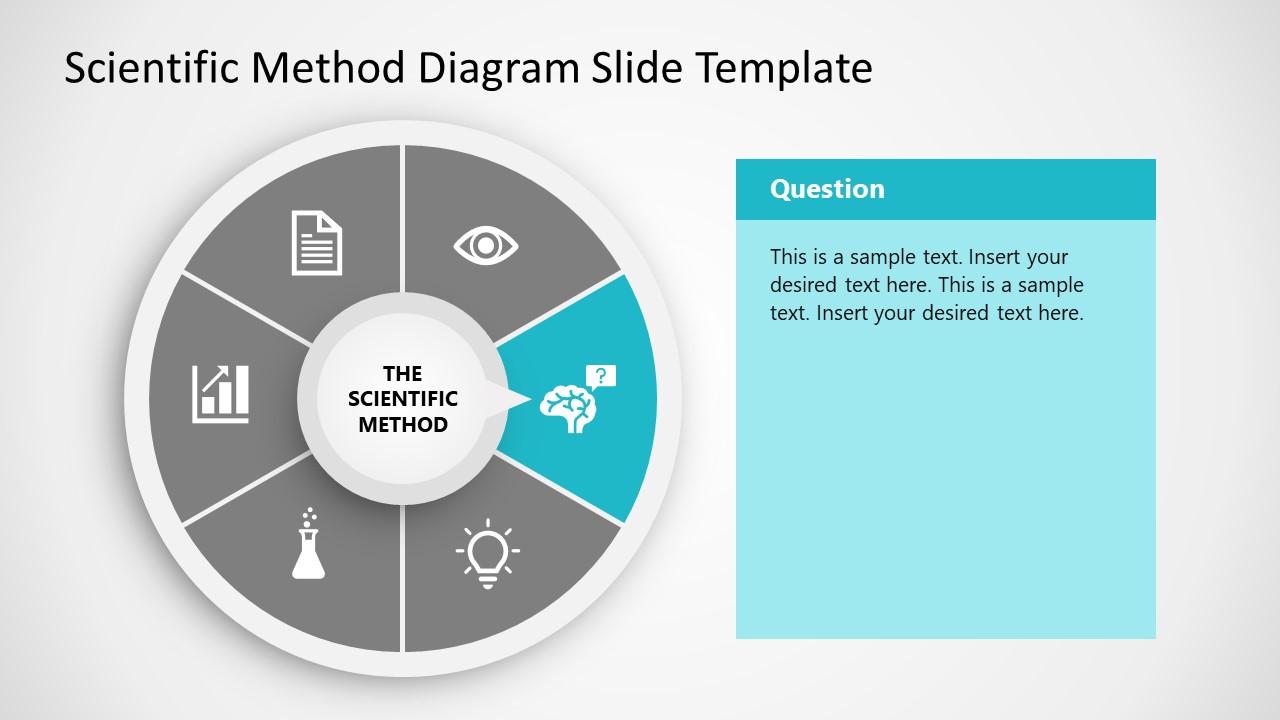

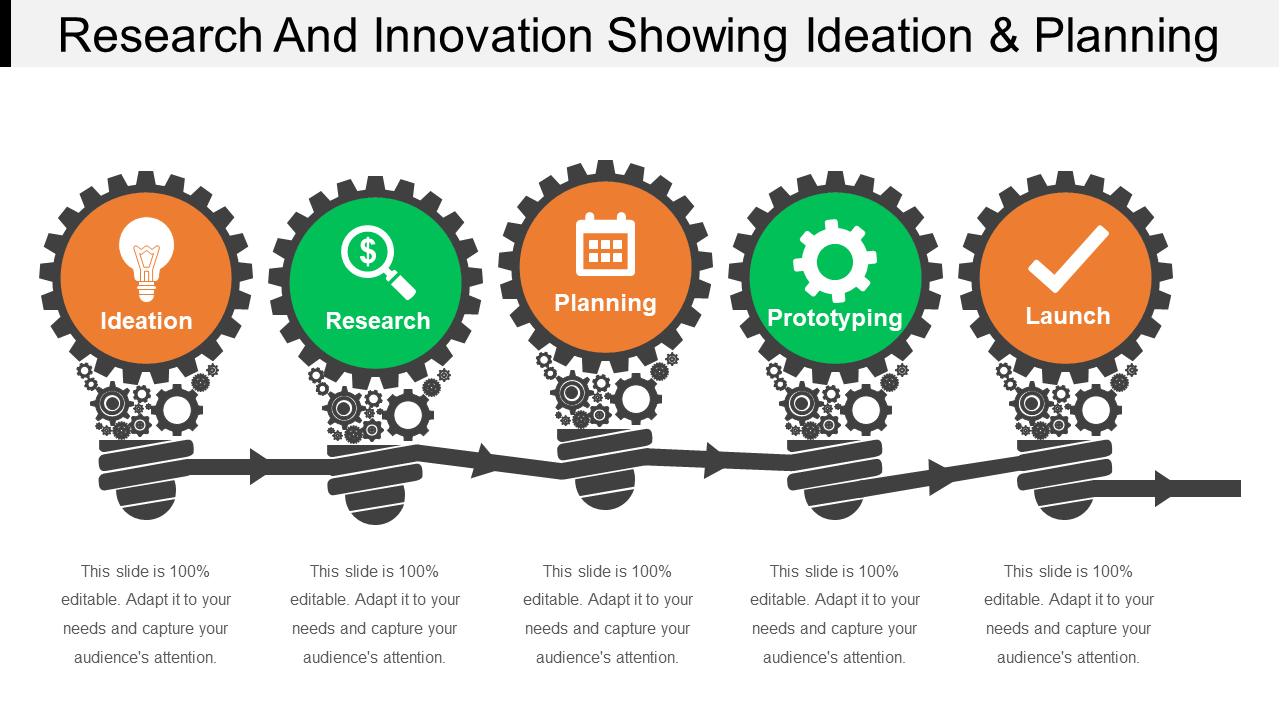

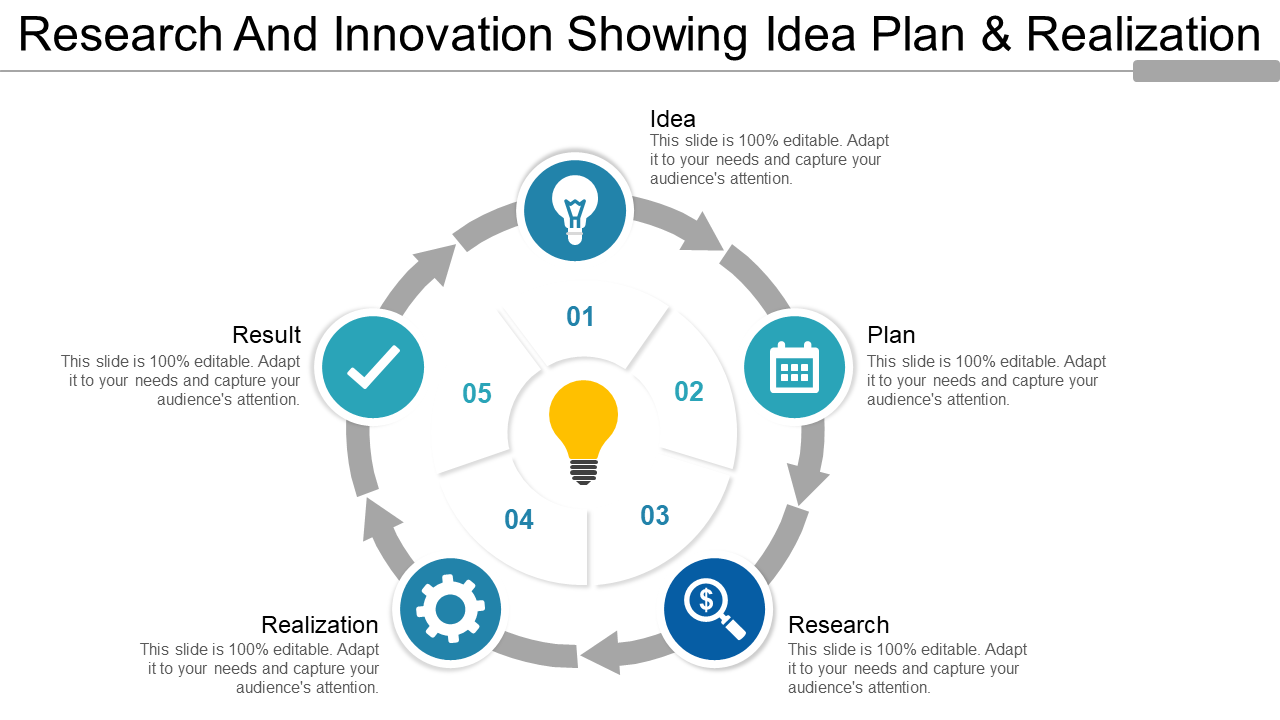

2. Research Presentation Scientific Method Diagram PowerPoint Template

Whenever you intend to raise questions, expose the methodology you used for your research, or even suggest a scientific method approach for future analysis, this circular wheel diagram is a perfect fit for any presentation study.

Customize all of its elements to suit the demands of your presentation in just minutes.

3. Thesis Research Presentation PowerPoint Template

If your research presentation project belongs to academia, then this is the slide deck to pair that presentation. With a formal aesthetic and minimalistic style, this research presentation template focuses only on exposing your information as clearly as possible.

Use its included bar charts and graphs to introduce data, change the background of each slide to suit the topic of your presentation, and customize each of its elements to meet the requirements of your project with ease.

4. Animated Research Cards PowerPoint Template

Visualize ideas and their connection points with the help of this research card template for PowerPoint. This slide deck, for example, can help speakers talk about alternative concepts to what they are currently managing and its possible outcomes, among different other usages this versatile PPT template has. Zoom Animation effects make a smooth transition between cards (or ideas).

5. Research Presentation Slide Deck for PowerPoint

With a distinctive professional style, this research presentation PPT template helps business professionals and academics alike to introduce the findings of their work to team members or investors.

By accessing this template, you get the following slides:

- Introduction

- Problem Statement

- Research Questions

- Conceptual Research Framework (Concepts, Theories, Actors, & Constructs)

- Study design and methods

- Population & Sampling

- Data Collection

- Data Analysis

Check it out today and craft a powerful research presentation out of it!

A successful research presentation in business is not just about presenting data; it’s about persuasion to take meaningful action. It’s the bridge that connects your research efforts to the strategic initiatives of your organization. To embark on this journey successfully, planning your presentation thoroughly is paramount, from designing your PowerPoint to the delivery.

Take a look and get inspiration from the sample research presentation slides above, put our tips to heart, and transform your research findings into a compelling call to action.

Like this article? Please share

Academics, Presentation Approaches, Research & Development Filed under Presentation Ideas

Related Articles

Filed under Design • May 22nd, 2024

Exploring the 12 Different Types of Slides in PowerPoint

Become a better presenter by harnessing the power of the 12 different types of slides in presentation design.

Filed under Design • March 27th, 2024

How to Make a Presentation Graph

Detailed step-by-step instructions to master the art of how to make a presentation graph in PowerPoint and Google Slides. Check it out!

Filed under Presentation Ideas • February 29th, 2024

How to Make a Fundraising Presentation (with Thermometer Templates & Slides)

Meet a new framework to design fundraising presentations by harnessing the power of fundraising thermometer templates. Detailed guide with examples.

Leave a Reply

Princeton Correspondents on Undergraduate Research

How to Make a Successful Research Presentation

Turning a research paper into a visual presentation is difficult; there are pitfalls, and navigating the path to a brief, informative presentation takes time and practice. As a TA for GEO/WRI 201: Methods in Data Analysis & Scientific Writing this past fall, I saw how this process works from an instructor’s standpoint. I’ve presented my own research before, but helping others present theirs taught me a bit more about the process. Here are some tips I learned that may help you with your next research presentation:

More is more

In general, your presentation will always benefit from more practice, more feedback, and more revision. By practicing in front of friends, you can get comfortable with presenting your work while receiving feedback. It is hard to know how to revise your presentation if you never practice. If you are presenting to a general audience, getting feedback from someone outside of your discipline is crucial. Terms and ideas that seem intuitive to you may be completely foreign to someone else, and your well-crafted presentation could fall flat.

Less is more

Limit the scope of your presentation, the number of slides, and the text on each slide. In my experience, text works well for organizing slides, orienting the audience to key terms, and annotating important figures–not for explaining complex ideas. Having fewer slides is usually better as well. In general, about one slide per minute of presentation is an appropriate budget. Too many slides is usually a sign that your topic is too broad.

Limit the scope of your presentation

Don’t present your paper. Presentations are usually around 10 min long. You will not have time to explain all of the research you did in a semester (or a year!) in such a short span of time. Instead, focus on the highlight(s). Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

You will not have time to explain all of the research you did. Instead, focus on the highlights. Identify a single compelling research question which your work addressed, and craft a succinct but complete narrative around it.

Craft a compelling research narrative

After identifying the focused research question, walk your audience through your research as if it were a story. Presentations with strong narrative arcs are clear, captivating, and compelling.

- Introduction (exposition — rising action)

Orient the audience and draw them in by demonstrating the relevance and importance of your research story with strong global motive. Provide them with the necessary vocabulary and background knowledge to understand the plot of your story. Introduce the key studies (characters) relevant in your story and build tension and conflict with scholarly and data motive. By the end of your introduction, your audience should clearly understand your research question and be dying to know how you resolve the tension built through motive.

- Methods (rising action)

The methods section should transition smoothly and logically from the introduction. Beware of presenting your methods in a boring, arc-killing, ‘this is what I did.’ Focus on the details that set your story apart from the stories other people have already told. Keep the audience interested by clearly motivating your decisions based on your original research question or the tension built in your introduction.

- Results (climax)

Less is usually more here. Only present results which are clearly related to the focused research question you are presenting. Make sure you explain the results clearly so that your audience understands what your research found. This is the peak of tension in your narrative arc, so don’t undercut it by quickly clicking through to your discussion.

- Discussion (falling action)

By now your audience should be dying for a satisfying resolution. Here is where you contextualize your results and begin resolving the tension between past research. Be thorough. If you have too many conflicts left unresolved, or you don’t have enough time to present all of the resolutions, you probably need to further narrow the scope of your presentation.

- Conclusion (denouement)

Return back to your initial research question and motive, resolving any final conflicts and tying up loose ends. Leave the audience with a clear resolution of your focus research question, and use unresolved tension to set up potential sequels (i.e. further research).

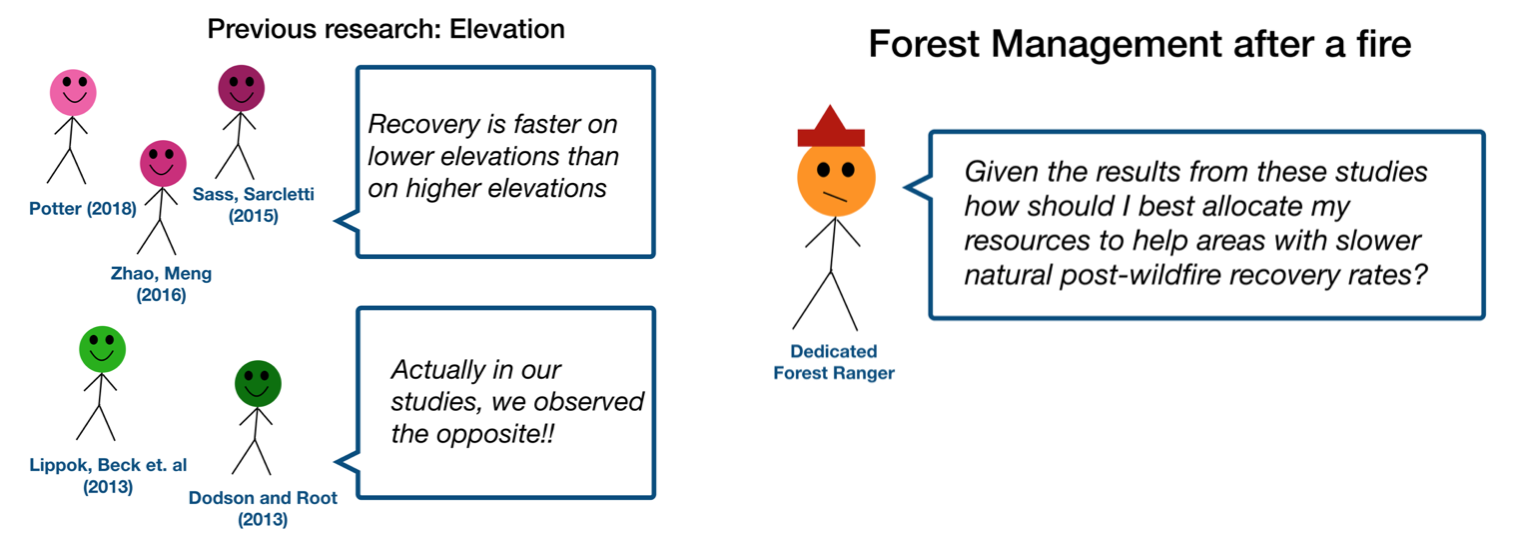

Use your medium to enhance the narrative

Visual presentations should be dominated by clear, intentional graphics. Subtle animation in key moments (usually during the results or discussion) can add drama to the narrative arc and make conflict resolutions more satisfying. You are narrating a story written in images, videos, cartoons, and graphs. While your paper is mostly text, with graphics to highlight crucial points, your slides should be the opposite. Adapting to the new medium may require you to create or acquire far more graphics than you included in your paper, but it is necessary to create an engaging presentation.

The most important thing you can do for your presentation is to practice and revise. Bother your friends, your roommates, TAs–anybody who will sit down and listen to your work. Beyond that, think about presentations you have found compelling and try to incorporate some of those elements into your own. Remember you want your work to be comprehensible; you aren’t creating experts in 10 minutes. Above all, try to stay passionate about what you did and why. You put the time in, so show your audience that it’s worth it.

For more insight into research presentations, check out these past PCUR posts written by Emma and Ellie .

— Alec Getraer, Natural Sciences Correspondent

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Chapter 20. Presentations

Introduction.

If a tree falls in a forest, and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound? If a qualitative study is conducted, but it is not presented (in words or text), did it really happen? Perhaps not. Findings from qualitative research are inextricably tied up with the way those findings are presented. These presentations do not always need to be in writing, but they need to happen. Think of ethnographies, for example, and their thick descriptions of a particular culture. Witnessing a culture, taking fieldnotes, talking to people—none of those things in and of themselves convey the culture. Or think about an interview-based phenomenological study. Boxes of interview transcripts might be interesting to read through, but they are not a completed study without the intervention of hours of analysis and careful selection of exemplary quotes to illustrate key themes and final arguments and theories. And unlike much quantitative research in the social sciences, where the final write-up neatly reports the results of analyses, the way the “write-up” happens is an integral part of the analysis in qualitative research. Once again, we come back to the messiness and stubborn unlinearity of qualitative research. From the very beginning, when designing the study, imagining the form of its ultimate presentation is helpful.

Because qualitative researchers are motivated by understanding and conveying meaning, effective communication is not only an essential skill but a fundamental facet of the entire research project. Ethnographers must be able to convey a certain sense of verisimilitude, the appearance of true reality. Those employing interviews must faithfully depict the key meanings of the people they interviewed in a way that rings true to those people, even if the end result surprises them. And all researchers must strive for clarity in their publications so that various audiences can understand what was found and why it is important. This chapter will address how to organize various kinds of presentations for different audiences so that your results can be appreciated and understood.

In the world of academic science, social or otherwise, the primary audience for a study’s results is usually the academic community, and the primary venue for communicating to this audience is the academic journal. Journal articles are typically fifteen to thirty pages in length (8,000 to 12,000 words). Although qualitative researchers often write and publish journal articles—indeed, there are several journals dedicated entirely to qualitative research [1] —the best writing by qualitative researchers often shows up in books. This is because books, running from 80,000 to 150,000 words in length, allow the researcher to develop the material fully. You have probably read some of these in various courses you have taken, not realizing what they are. I have used examples of such books throughout this text, beginning with the three profiles in the introductory chapter. In some instances, the chapters in these books began as articles in academic journals (another indication that the journal article format somewhat limits what can be said about the study overall).

While the article and the book are “final” products of qualitative research, there are actually a few other presentation formats that are used along the way. At the very beginning of a research study, it is often important to have a written research proposal not just to clarify to yourself what you will be doing and when but also to justify your research to an outside agency, such as an institutional review board (IRB; see chapter 12), or to a potential funder, which might be your home institution, a government funder (such as the National Science Foundation, or NSF), or a private foundation (such as the Gates Foundation). As you get your research underway, opportunities will arise to present preliminary findings to audiences, usually through presentations at academic conferences. These presentations can provide important feedback as you complete your analyses. Finally, if you are completing a degree and looking to find an academic job, you will be asked to provide a “job talk,” usually about your research. These job talks are similar to conference presentations but can run significantly longer.

All the presentations mentioned so far are (mostly) for academic audiences. But qualitative research is also unique in that many of its practitioners don’t want to confine their presentation only to other academics. Qualitative researchers who study particular contexts or cultures might want to report back to the people and places they observed. Those working in the critical tradition might want to raise awareness of a particular issue to as large an audience as possible. Many others simply want everyday, nonacademic people to read their work, because they think it is interesting and important. To reach a wide audience, the final product can look like almost anything—it can be a poem, a blog, a podcast, even a science fiction short story. And if you are very lucky, it can even be a national or international bestseller.

In this chapter, we are going to stick with the more basic quotidian presentations—the academic paper / research proposal, the conference slideshow presentation / job talk, and the conference poster. We’ll also spend a bit of time on incorporating universal design into your presentations and how to create some especially attractive and impactful visual displays.

Researcher Note

What is the best piece of advice you’ve ever been given about conducting qualitative research?

The best advice I’ve received came from my adviser, Alford Young Jr. He told me to find the “Jessi Streib” answer to my research question, not the “Pierre Bourdieu” answer to my research question. In other words, don’t just say how a famous theorist would answer your question; say something original, something coming from you.

—Jessi Streib, author of The Power of the Past and Privilege Lost

Writing about Your Research

The journal article and the research proposal.

Although the research proposal is written before you have actually done your research and the article is written after all data collection and analysis is complete, there are actually many similarities between the two in terms of organization and purpose. The final article will (probably—depends on how much the research question and focus have shifted during the research itself) incorporate a great deal of what was included in a preliminary research proposal. The average lengths of both a proposal and an article are quite similar, with the “front sections” of the article abbreviated to make space for the findings, discussion of findings, and conclusion.

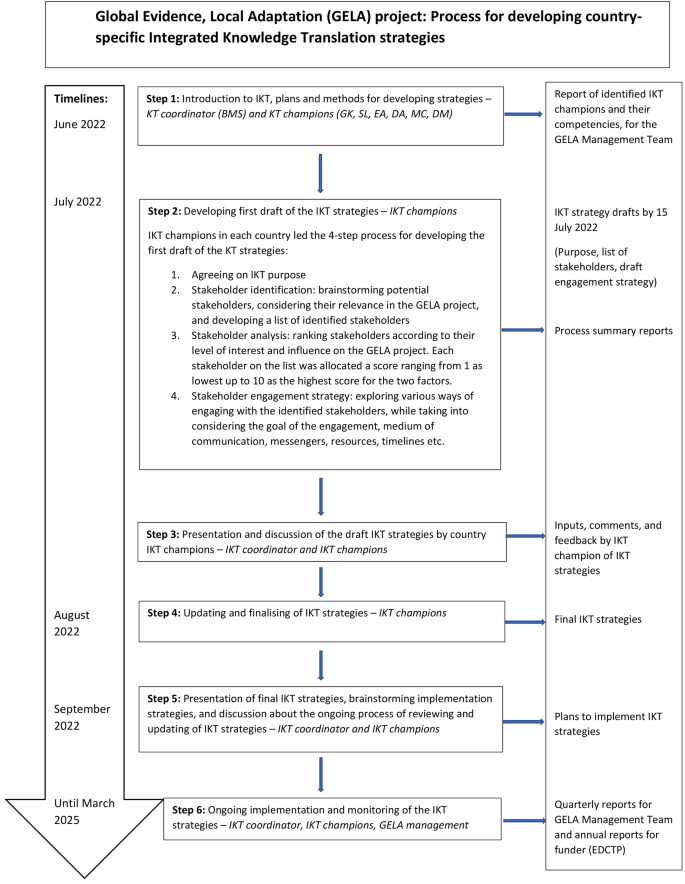

Figure 20.1 shows one model for what to include in an article or research proposal, comparing the elements of each with a default word count for each section. Please note that you will want to follow whatever specific guidelines you have been provided by the venue you are submitting the article/proposal to: the IRB, the NSF, the Journal of Qualitative Research . In fact, I encourage you to adapt the default model as needed by swapping out expected word counts for each section and adding or varying the sections to match expectations for your particular publication venue. [2]

You will notice a few things about the default model guidelines. First, while half of the proposal is spent discussing the research design, this section is shortened (but still included) for the article. There are a few elements that only show up in the proposal (e.g., the limitations section is in the introductory section here—it will be more fully developed in the conclusory section in the article). Obviously, you don’t have findings in the proposal, so this is an entirely new section for the article. Note that the article does not include a data management plan or a timeline—two aspects that most proposals require.

It might be helpful to find and maintain examples of successfully written sections that you can use as models for your own writing. I have included a few of these throughout the textbook and have included a few more at the end of this chapter.

Make an Argument

Some qualitative researchers, particularly those engaged in deep ethnographic research, focus their attention primarily if not exclusively on describing the data. They might even eschew the notion that they should make an “argument” about the data, preferring instead to use thick descriptions to convey interpretations. Bracketing the contrast between interpretation and argument for the moment, most readers will expect you to provide an argument about your data, and this argument will be in answer to whatever research question you eventually articulate (remember, research questions are allowed to shift as you get further into data collection and analysis). It can be frustrating to read a well-developed study with clear and elegant descriptions and no argument. The argument is the point of the research, and if you do not have one, 99 percent of the time, you are not finished with your analysis. Calarco ( 2020 ) suggests you imagine a pyramid, with all of your data forming the basis and all of your findings forming the middle section; the top/point of the pyramid is your argument, “what the patterns in your data tell us about how the world works or ought to work” ( 181 ).

The academic community to which you belong will be looking for an argument that relates to or develops theory. This is the theoretical generalizability promise of qualitative research. An academic audience will want to know how your findings relate to previous findings, theories, and concepts (the literature review; see chapter 9). It is thus vitally important that you go back to your literature review (or develop a new one) and draw those connections in your discussion and/or conclusion. When writing to other audiences, you will still want an argument, although it may not be written as a theoretical one. What do I mean by that? Even if you are not referring to previous literature or developing new theories or adapting older ones, a simple description of your findings is like dumping a lot of leaves in the lap of your audience. They still deserve to know about the shape of the forest. Maybe provide them a road map through it. Do this by telling a clear and cogent story about the data. What is the primary theme, and why is it important? What is the point of your research? [3]

A beautifully written piece of research based on participant observation [and/or] interviews brings people to life, and helps the reader understand the challenges people face. You are trying to use vivid, detailed and compelling words to help the reader really understand the lives of the people you studied. And you are trying to connect the lived experiences of these people to a broader conceptual point—so that the reader can understand why it matters. ( Lareau 2021:259 )

Do not hide your argument. Make it the focal point of your introductory section, and repeat it as often as needed to ensure the reader remembers it. I am always impressed when I see researchers do this well (see, e.g., Zelizer 1996 ).

Here are a few other suggestions for writing your article: Be brief. Do not overwhelm the reader with too many words; make every word count. Academics are particularly prone to “overwriting” as a way of demonstrating proficiency. Don’t. When writing your methods section, think about it as a “recipe for your work” that allows other researchers to replicate if they so wish ( Calarco 2020:186 ). Convey all the necessary information clearly, succinctly, and accurately. No more, no less. [4] Do not try to write from “beginning to end” in that order. Certain sections, like the introductory section, may be the last ones you write. I find the methods section the easiest, so I often begin there. Calarco ( 2020 ) begins with an outline of the analysis and results section and then works backward from there to outline the contribution she is making, then the full introduction that serves as a road map for the writing of all sections. She leaves the abstract for the very end. Find what order best works for you.

Presenting at Conferences and Job Talks

Students and faculty are primarily called upon to publicly present their research in two distinct contexts—the academic conference and the “job talk.” By convention, conference presentations usually run about fifteen minutes and, at least in sociology and other social sciences, rely primarily on the use of a slideshow (PowerPoint Presentation or PPT) presentation. You are usually one of three or four presenters scheduled on the same “panel,” so it is an important point of etiquette to ensure that your presentation falls within the allotted time and does not crowd into that of the other presenters. Job talks, on the other hand, conventionally require a forty- to forty-five-minute presentation with a fifteen- to twenty-minute question and answer (Q&A) session following it. You are the only person presenting, so if you run over your allotted time, it means less time for the Q&A, which can disturb some audience members who have been waiting for a chance to ask you something. It is sometimes possible to incorporate questions during your presentation, which allows you to take the entire hour, but you might end up shorting your presentation this way if the questions are numerous. It’s best for beginners to stick to the “ask me at the end” format (unless there is a simple clarifying question that can easily be addressed and makes the presentation run more smoothly, as in the case where you simply forgot to include information on the number of interviews you conducted).

For slideshows, you should allot two or even three minutes for each slide, never less than one minute. And those slides should be clear, concise, and limited. Most of what you say should not be on those slides at all. The slides are simply the main points or a clear image of what you are speaking about. Include bulleted points (words, short phrases), not full sentences. The exception is illustrative quotations from transcripts or fieldnotes. In those cases, keep to one illustrative quote per slide, and if it is long, bold or otherwise, highlight the words or passages that are most important for the audience to notice. [5]

Figure 20.2 provides a possible model for sections to include in either a conference presentation or a job talk, with approximate times and approximate numbers of slides. Note the importance (in amount of time spent) of both the research design and the findings/results sections, both of which have been helpfully starred for you. Although you don’t want to short any of the sections, these two sections are the heart of your presentation.

Fig 20.2. Suggested Slideshow Times and Number of Slides

Should you write out your script to read along with your presentation? I have seen this work well, as it prevents presenters from straying off topic and keeps them to the time allotted. On the other hand, these presentations can seem stiff and wooden. Personally, although I have a general script in advance, I like to speak a little more informally and engagingly with each slide, sometimes making connections with previous panelists if I am at a conference. This means I have to pay attention to the time, and I sometimes end up breezing through one section more quickly than I would like. Whatever approach you take, practice in advance. Many times. With an audience. Ask for feedback, and pay attention to any presentation issues that arise (e.g., Do you speak too fast? Are you hard to hear? Do you stumble over a particular word or name?).

Even though there are rules and guidelines for what to include, you will still want to make your presentation as engaging as possible in the little amount of time you have. Calarco ( 2020:274 ) recommends trying one of three story structures to frame your presentation: (1) the uncertain explanation , where you introduce a phenomenon that has not yet been fully explained and then describe how your research is tackling this; (2) the uncertain outcome , where you introduce a phenomenon where the consequences have been unclear and then you reveal those consequences with your research; and (3) the evocative example , where you start with some interesting example from your research (a quote from the interview transcripts, for example) or the real world and then explain how that example illustrates the larger patterns you found in your research. Notice that each of these is a framing story. Framing stories are essential regardless of format!

A Word on Universal Design

Please consider accessibility issues during your presentation, and incorporate elements of universal design into your slideshow. The basic idea behind universal design in presentations is that to the greatest extent possible, all people should be able to view, hear, or otherwise take in your presentation without needing special individual adaptations. If you can make your presentation accessible to people with visual impairment or hearing loss, why not do so? For example, one in twelve men is color-blind, unable to differentiate between certain colors, red/green being the most common problem. So if you design a graphic that relies on red and green bars, some of your audience members may not be able to properly identify which bar means what. Simple contrasts of black and white are much more likely to be visible to all members of your audience. There are many other elements of good universal design, but the basic foundation of all of them is that you consider how to make your presentation as accessible as possible at the outset. For example, include captions whenever possible, both as descriptions on slides and as images on slides and for any audio or video clips you are including; keep font sizes large enough to read from the back of the room; and face the audience when you are.

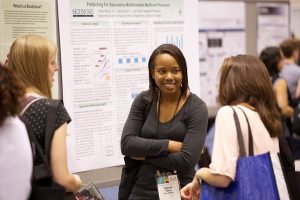

Poster Design

Undergraduate students who present at conferences are often encouraged to present at “poster sessions.” This usually means setting up a poster version of your research in a large hall or convention space at a set period of time—ninety minutes is common. Your poster will be one of dozens, and conference-goers will wander through the space, stopping intermittently at posters that attract them. Those who stop by might ask you questions about your research, and you are expected to be able to talk intelligently for two or three minutes. It’s a fairly easy way to practice presenting at conferences, which is why so many organizations hold these special poster sessions.

A good poster design will be immediately attractive to passersby and clearly and succinctly describe your research methods, findings, and conclusions. Some students have simply shrunk down their research papers to manageable sizes and then pasted them on a poster, all twelve to fifteen pages of them. Don’t do that! Here are some better suggestions: State the main conclusion of your research in large bold print at the top of your poster, on brightly colored (contrasting) paper, and paste in a QR code that links to your full paper online ( Calarco 2020:280 ). Use the rest of the poster board to provide a couple of highlights and details of the study. For an interview-based study, for example, you will want to put in some details about your sample (including number of interviews) and setting and then perhaps one or two key quotes, also distinguished by contrasting color background.

Incorporating Visual Design in Your Presentations

In addition to ensuring that your presentation is accessible to as large an audience as possible, you also want to think about how to display your data in general, particularly how to use charts and graphs and figures. [6] The first piece of advice is, use them! As the saying goes, a picture is worth a thousand words. If you can cut to the chase with a visually stunning display, do so. But there are visual displays that are stunning, and then there are the tired, hard-to-see visual displays that predominate at conferences. You can do better than most presenters by simply paying attention here and committing yourself to a good design. As with model section passages, keep a file of visual displays that work as models for your own presentations. Find a good guidebook to presenting data effectively (Evergreen 2018 , 2019 ; Schwabisch 2021) , and refer to it often.

Let me make a few suggestions here to get you started. First, test every visual display on a friend or colleague to find out how quickly they can understand the point you are trying to convey. As with reading passages aloud to ensure that your writing works, showing someone your display is the quickest way to find out if it works. Second, put the point in the title of the display! When writing for an academic journal, there will be specific conventions of what to include in the title (full description including methods of analysis, sample, dates), but in a public presentation, there are no limiting rules. So you are free to write as your title “Working-Class College Students Are Three Times as Likely as Their Peers to Drop Out of College,” if that is the point of the graphic display. It certainly helps the communicative aspect. Third, use the themes available to you in Excel for creating graphic displays, but alter them to better fit your needs . Consider adding dark borders to bars and columns, for example, so that they appear crisper for your audience. Include data callouts and labels, and enlarge them so they are clearly visible. When duplicative or otherwise unnecessary, drop distracting gridlines and labels on the y-axis (the vertical one). Don’t go crazy adding different fonts, however—keep things simple and clear. Sans serif fonts (those without the little hooks on the ends of letters) read better from a distance. Try to use the same color scheme throughout, even if this means manually changing the colors of bars and columns. For example, when reporting on working-class college students, I use blue bars, while I reserve green bars for wealthy students and yellow bars for students in the middle. I repeat these colors throughout my presentations and incorporate different colors when talking about other items or factors. You can also try using simple grayscale throughout, with pops of color to indicate a bar or column or line that is of the most interest. These are just some suggestions. The point is to take presentation seriously and to pay attention to visual displays you are using to ensure they effectively communicate what you want them to communicate. I’ve included a data visualization checklist from Evergreen ( 2018 ) here.

Ethics of Presentation and Reliability

Until now, all the data you have collected have been yours alone. Once you present the data, however, you are sharing sometimes very intimate information about people with a broader public. You will find yourself balancing between protecting the privacy of those you’ve interviewed and observed and needing to demonstrate the reliability of the study. The more information you provide to your audience, the more they can understand and appreciate what you have found, but this also may pose risks to your participants. There is no one correct way to go about finding the right balance. As always, you have a duty to consider what you are doing and must make some hard decisions.

The most obvious place we see this paradox emerge is when you mask your data to protect the privacy of your participants. It is standard practice to provide pseudonyms, for example. It is such standard practice that you should always assume you are being given a pseudonym when reading a book or article based on qualitative research. When I was a graduate student, I tried to find information on how best to construct pseudonyms but found little guidance. There are some ethical issues here, I think. [7] Do you create a name that has the same kind of resonance as the original name? If the person goes by a nickname, should you use a nickname as a pseudonym? What about names that are ethnically marked (as in, almost all of them)? Is there something unethical about reracializing a person? (Yes!) In her study of adolescent subcultures, Wilkins ( 2008 ) noted, “Because many of the goths used creative, alternative names rather than their given names, I did my best to reproduce the spirit of their chosen names” ( 24 ).

Your reader or audience will want to know all the details about your participants so that they can gauge both your credibility and the reliability of your findings. But how many details are too many? What if you change the name but otherwise retain all the personal pieces of information about where they grew up, and how old they were when they got married, and how many children they have, and whether they made a splash in the news cycle that time they were stalked by their ex-boyfriend? At some point, those details are going to tip over into the zone of potential unmasking. When you are doing research at one particular field site that may be easily ascertained (as when you interview college students, probably at the institution at which you are a student yourself), it is even more important to be wary of providing too many details. You also need to think that your participants might read what you have written, know things about the site or the population from which you drew your interviews, and figure out whom you are talking about. This can all get very messy if you don’t do more than simply pseudonymize the people you interviewed or observed.

There are some ways to do this. One, you can design a study with all of these risks in mind. That might mean choosing to conduct interviews or observations at multiple sites so that no one person can be easily identified. Another is to alter some basic details about your participants to protect their identity or to refuse to provide all the information when selecting quotes . Let’s say you have an interviewee named “Anna” (a pseudonym), and she is a twenty-four-year-old Latina studying to be an engineer. You want to use a quote from Anna about racial discrimination in her graduate program. Instead of attributing the quote to Anna (whom your reader knows, because you’ve already told them, is a twenty-four-year-old Latina studying engineering), you might simply attribute the quote to “Latina student in STEM.” Taking this a step further, you might leave the quote unattributed, providing a list of quotes about racial discrimination by “various students.”

The problem with masking all the identifiers, of course, is that you lose some of the analytical heft of those attributes. If it mattered that Anna was twenty-four (not thirty-four) and that she was a Latina and that she was studying engineering, taking out any of those aspects of her identity might weaken your analysis. This is one of those “hard choices” you will be called on to make! A rather radical and controversial solution to this dilemma is to create composite characters , characters based on the reality of the interviews but fully masked because they are not identifiable with any one person. My students are often very queasy about this when I explain it to them. The more positivistic your approach and the more you see individuals rather than social relationships/structure as the “object” of your study, the more employing composites will seem like a really bad idea. But composites “allow researchers to present complex, situated accounts from individuals” without disclosing personal identities ( Willis 2019 ), and they can be effective ways of presenting theory narratively ( Hurst 2019 ). Ironically, composites permit you more latitude when including “dirty laundry” or stories that could harm individuals if their identities became known. Rather than squeezing out details that could identify a participant, the identities are permanently removed from the details. Great difficulty remains, however, in clearly explaining the theoretical use of composites to your audience and providing sufficient information on the reliability of the underlying data.

There are a host of other ethical issues that emerge as you write and present your data. This is where being reflective throughout the process will help. How and what you share of what you have learned will depend on the social relationships you have built, the audiences you are writing or speaking to, and the underlying animating goals of your study. Be conscious about all of your decisions, and then be able to explain them fully, both to yourself and to those who ask.

Our research is often close to us. As a Black woman who is a first-generation college student and a professional with a poverty/working-class origin, each of these pieces of my identity creates nuances in how I engage in my research, including how I share it out. Because of this, it’s important for us to have people in our lives who we trust who can help us, particularly, when we are trying to share our findings. As researchers, we have been steeped in our work, so we know all the details and nuances. Sometimes we take this for granted, and we might not have shared those nuances in conversation or writing or taken some of this information for granted. As I share my research with trusted friends and colleagues, I pay attention to the questions they ask me or the feedback they give when we talk or when they read drafts.

—Kim McAloney, PhD, College Student Services Administration Ecampus coordinator and instructor

Final Comments: Preparing for Being Challenged

Once you put your work out there, you must be ready to be challenged. Science is a collective enterprise and depends on a healthy give and take among researchers. This can be both novel and difficult as you get started, but the more you understand the importance of these challenges, the easier it will be to develop the kind of thick skin necessary for success in academia. Scientists’ authority rests on both the inherent strength of their findings and their ability to convince other scientists of the reliability and validity and value of those findings. So be prepared to be challenged, and recognize this as simply another important aspect of conducting research!

Considering what challenges might be made as you design and conduct your study will help you when you get to the writing and presentation stage. Address probable challenges in your final article, and have a planned response to probable questions in a conference presentation or job talk. The following is a list of common challenges of qualitative research and how you might best address them:

- Questions about generalizability . Although qualitative research is not statistically generalizable (and be prepared to explain why), qualitative research is theoretically generalizable. Discuss why your findings here might tell us something about related phenomena or contexts.

- Questions about reliability . You probably took steps to ensure the reliability of your findings. Discuss them! This includes explaining the use and value of multiple data sources and defending your sampling and case selections. It also means being transparent about your own position as researcher and explaining steps you took to ensure that what you were seeing was really there.

- Questions about replicability. Although qualitative research cannot strictly be replicated because the circumstances and contexts will necessarily be different (if only because the point in time is different), you should be able to provide as much detail as possible about how the study was conducted so that another researcher could attempt to confirm or disconfirm your findings. Also, be very clear about the limitations of your study, as this allows other researchers insight into what future research might be warranted.

None of this is easy, of course. Writing beautifully and presenting clearly and cogently require skill and practice. If you take anything from this chapter, it is to remember that presentation is an important and essential part of the research process and to allocate time for this as you plan your research.

Data Visualization Checklist for Slideshow (PPT) Presentations

Adapted from Evergreen ( 2018 )

Text checklist

- Short catchy, descriptive titles (e.g., “Working-class students are three times as likely to drop out of college”) summarize the point of the visual display

- Subtitled and annotations provide additional information (e.g., “note: male students also more likely to drop out”)

- Text size is hierarchical and readable (titles are largest; axes labels smallest, which should be at least 20points)

- Text is horizontal. Audience members cannot read vertical text!

- All data labeled directly and clearly: get rid of those “legends” and embed the data in your graphic display

- Labels are used sparingly; avoid redundancy (e.g., do not include both a number axis and a number label)

Arrangement checklist

- Proportions are accurate; bar charts should always start at zero; don’t mislead the audience!

- Data are intentionally ordered (e.g., by frequency counts). Do not leave ragged alphabetized bar graphs!

- Axis intervals are equidistant: spaces between axis intervals should be the same unit

- Graph is two-dimensional. Three-dimensional and “bevelled” displays are confusing

- There is no unwanted decoration (especially the kind that comes automatically through the PPT “theme”). This wastes your space and confuses.

Color checklist

- There is an intentional color scheme (do not use default theme)

- Color is used to identify key patterns (e.g., highlight one bar in red against six others in greyscale if this is the bar you want the audience to notice)

- Color is still legible when printed in black and white

- Color is legible for people with color blindness (do not use red/green or yellow/blue combinations)

- There is sufficient contrast between text and background (black text on white background works best; be careful of white on dark!)

Lines checklist

- Be wary of using gridlines; if you do, mute them (grey, not black)

- Allow graph to bleed into surroundings (don’t use border lines)

- Remove axis lines unless absolutely necessary (better to label directly)

Overall design checklist

- The display highlights a significant finding or conclusion that your audience can ‘”see” relatively quickly

- The type of graph (e.g., bar chart, pie chart, line graph) is appropriate for the data. Avoid pie charts with more than three slices!

- Graph has appropriate level of precision; if you don’t need decimal places

- All the chart elements work together to reinforce the main message

Universal Design Checklist for Slideshow (PPT) Presentations

- Include both verbal and written descriptions (e.g., captions on slides); consider providing a hand-out to accompany the presentation

- Microphone available (ask audience in back if they can clearly hear)

- Face audience; allow people to read your lips

- Turn on captions when presenting audio or video clips

- Adjust light settings for visibility

- Speak slowly and clearly; practice articulation; don’t mutter or speak under your breath (even if you have something humorous to say – say it loud!)

- Use Black/White contrasts for easy visibility; or use color contrasts that are real contrasts (do not rely on people being able to differentiate red from green, for example)

- Use easy to read font styles and avoid too small font sizes: think about what an audience member in the back row will be able to see and read.

- Keep your slides simple: do not overclutter them; if you are including quotes from your interviews, take short evocative snippets only, and bold key words and passages. You should also read aloud each passage, preferably with feeling!

Supplement: Models of Written Sections for Future Reference

Data collection section example.

Interviews were semi structured, lasted between one and three hours, and took place at a location chosen by the interviewee. Discussions centered on four general topics: (1) knowledge of their parent’s immigration experiences; (2) relationship with their parents; (3) understanding of family labor, including language-brokering experiences; and (4) experiences with school and peers, including any future life plans. While conducting interviews, I paid close attention to respondents’ nonverbal cues, as well as their use of metaphors and jokes. I conducted interviews until I reached a point of saturation, as indicated by encountering repeated themes in new interviews (Glaser and Strauss 1967). Interviews were audio recorded, transcribed with each interviewee’s permission, and conducted in accordance with IRB protocols. Minors received permission from their parents before participation in the interview. ( Kwon 2022:1832 )

Justification of Case Selection / Sample Description Section Example

Looking at one profession within one organization and in one geographic area does impose limitations on the generalizability of our findings. However, it also has advantages. We eliminate the problem of interorganizational heterogeneity. If multiple organizations are studied simultaneously, it can make it difficult to discern the mechanisms that contribute to racial inequalities. Even with a single occupation there is considerable heterogeneity, which may make understanding how organizational structure impacts worker outcomes difficult. By using the case of one group of professionals in one religious denomination in one geographic region of the United States, we clarify how individuals’ perceptions and experiences of occupational inequality unfold in relation to a variety of observed and unobserved occupational and contextual factors that might be obscured in a larger-scale study. Focusing on a specific group of professionals allows us to explore and identify ways that formal organizational rules combine with informal processes to contribute to the persistence of racial inequality. ( Eagle and Mueller 2022:1510–1511 )

Ethics Section Example

I asked everyone who was willing to sit for a formal interview to speak only for themselves and offered each of them a prepaid Visa Card worth $25–40. I also offered everyone the opportunity to keep the card and erase the tape completely at any time they were dissatisfied with the interview in any way. No one asked for the tape to be erased; rather, people remarked on the interview being a really good experience because they felt heard. Each interview was professionally transcribed and for the most part the excerpts are literal transcriptions. In a few places, the excerpts have been edited to reduce colloquial features of speech (e.g., you know, like, um) and some recursive elements common to spoken language. A few excerpts were placed into standard English for clarity. I made this choice for the benefit of readers who might otherwise find the insights and ideas harder to parse in the original. However, I have to acknowledge this as an act of class-based violence. I tried to keep the original phrasing whenever possible. ( Pascale 2021:235 )

Further Readings

Calarco, Jessica McCrory. 2020. A Field Guide to Grad School: Uncovering the Hidden Curriculum . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Don’t let the unassuming title mislead you—there is a wealth of helpful information on writing and presenting data included here in a highly accessible manner. Every graduate student should have a copy of this book.

Edwards, Mark. 2012. Writing in Sociology . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. An excellent guide to writing and presenting sociological research by an Oregon State University professor. Geared toward undergraduates and useful for writing about either quantitative or qualitative research or both.

Evergreen, Stephanie D. H. 2018. Presenting Data Effectively: Communicating Your Findings for Maximum Impact . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is one of my very favorite books, and I recommend it highly for everyone who wants their presentations and publications to communicate more effectively than the boring black-and-white, ragged-edge tables and figures academics are used to seeing.

Evergreen, Stephanie D. H. 2019. Effective Data Visualization 2 . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE. This is an advanced primer for presenting clean and clear data using graphs, tables, color, font, and so on. Start with Evergreen (2018), and if you graduate from that text, move on to this one.

Schwabisch, Jonathan. 2021. Better Data Visualizations: A Guide for Scholars, Researchers, and Wonks . New York: Columbia University Press. Where Evergreen’s (2018, 2019) focus is on how to make the best visual displays possible for effective communication, this book is specifically geared toward visual displays of academic data, both quantitative and qualitative. If you want to know when it is appropriate to use a pie chart instead of a stacked bar chart, this is the reference to use.

- Some examples: Qualitative Inquiry , Qualitative Research , American Journal of Qualitative Research , Ethnography , Journal of Ethnographic and Qualitative Research , Qualitative Report , Qualitative Sociology , and Qualitative Studies . ↵

- This is something I do with every article I write: using Excel, I write each element of the expected article in a separate row, with one column for “expected word count” and another column for “actual word count.” I fill in the actual word count as I write. I add a third column for “comments to myself”—how things are progressing, what I still need to do, and so on. I then use the “sum” function below each of the first two columns to keep a running count of my progress relative to the final word count. ↵

- And this is true, I would argue, even when your primary goal is to leave space for the voices of those who don’t usually get a chance to be part of the conversation. You will still want to put those voices in some kind of choir, with a clear direction (song) to be sung. The worst thing you can do is overwhelm your audience with random quotes or long passages with no key to understanding them. Yes, a lot of metaphors—qualitative researchers love metaphors! ↵

- To take Calarco’s recipe analogy further, do not write like those food bloggers who spend more time discussing the color of their kitchen or the experiences they had at the market than they do the actual cooking; similarly, do not write recipes that omit crucial details like the amount of flour or the size of the baking pan used or the temperature of the oven. ↵

- The exception is the “compare and contrast” of two or more quotes, but use caution here. None of the quotes should be very long at all (a sentence or two each). ↵

- Although this section is geared toward presentations, many of the suggestions could also be useful when writing about your data. Don’t be afraid to use charts and graphs and figures when writing your proposal, article, thesis, or dissertation. At the very least, you should incorporate a tabular display of the participants, sites, or documents used. ↵

- I was so puzzled by these kinds of questions that I wrote one of my very first articles on it ( Hurst 2008 ). ↵

The visual presentation of data or information through graphics such as charts, graphs, plots, infographics, maps, and animation. Recall the best documentary you ever viewed, and there were probably excellent examples of good data visualization there (for me, this was An Inconvenient Truth , Al Gore’s film about climate change). Good data visualization allows more effective communication of findings of research, particularly in public presentations (e.g., slideshows).

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Research Voyage

Research Tips and Infromation

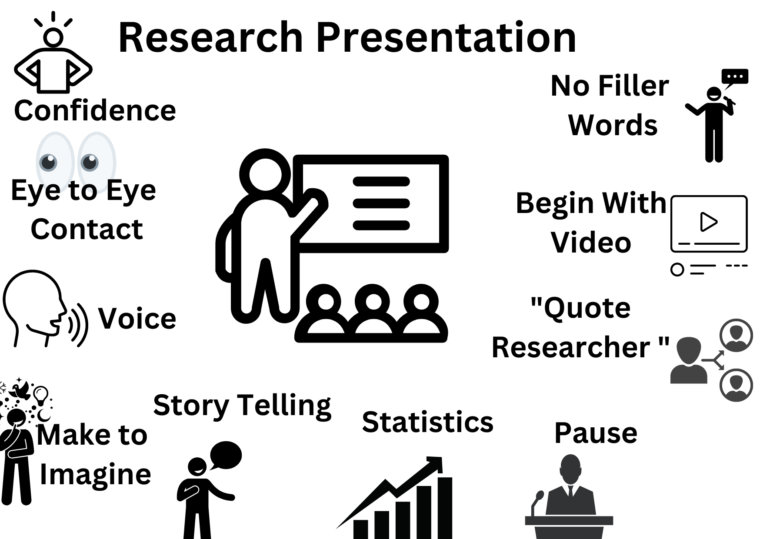

12 Proven Tips to Make an Effective Research Presentation as an Invited Speaker

Guidance from an Experienced Mentor

The evolution of my presentation skills, what is there in this post for you, research presentation tip #1: start confidently, research presentation tip #2: eye to eye contact with the audience, research presentation tip #3: welcome your audience, research presentation tip #4: adjust your voice.

- Research Presentation Tip #5: Memorize your Opening Line

- Research Presentation Tip #6: Use the words “ 'Think for while', 'Imagine', 'Think of', 'Close Your Eyes' ”

Research Presentation Tip #7: Story Telling

Research presentation tip #8: facts and statistics.

- Research Presentation Tip #9: Power of "Pause"

Research Presentation Tip #10: Quote a Great Researcher

Research presentation tip #11: begin with a video, research presentation tip #12: avoid using filler words, side benefits of giving great research presentations, how should i dress for my invited talk at a research conference, can i share my conference presentation slides after my talk with the audience, shall i entertain questions in between my presentation as an invited speaker to a research conference, can you give some tips for a successful q&a session:.

- How to handle questions where I don't know the answers in my presentation?

Introduction

In this blog post, I’ll be sharing with you some invaluable tips for delivering an effective research presentation, drawn from my own journey through academia. These tips are not just theoretical; they’re the result of my own experiences and the guidance I received along the way.

When I first embarked on my PhD journey, the prospect of presenting my research to an audience filled me with a mixture of excitement and apprehension. Like many researchers, I was eager to share my findings and insights, but I lacked the confidence and experience to do so effectively.

It wasn’t until I had been immersed in my research for nearly a year, clarifying my domain, objectives, and problem statements, that I was presented with an opportunity to speak about my work. However, despite my preparation, I found myself struggling to convey my ideas with clarity and confidence.

Fortunately, I was not alone in this journey. At the event where I was scheduled to present my research, there was another presenter—an experienced professor—who took notice of my nerves and offered his guidance. He generously shared with me a set of tips that would not only improve my presentation that day but also become the foundation for my future presentations.

As I incorporated these tips into my presentations, I noticed a remarkable improvement in my ability to engage and inform my audience. Each tip—from starting confidently to utilizing storytelling and incorporating facts and statistics—contributed to a more polished and impactful presentation style.

As an invited speaker, delivering an effective research presentation is essential to engage and inform your audience. A well-crafted presentation can help you communicate your research findings, ideas, and insights in a clear, concise, and engaging manner.

However, many presenters face challenges when it comes to delivering a successful presentation. Some of these challenges include nervousness, lack of confidence, and difficulty connecting with the audience.

In this article, we will discuss tips to help you make an effective research presentation as an invited speaker. We will cover strategies to prepare for your presentation, ways to deliver your presentation with confidence and impact, and common mistakes to avoid.

By following these tips, you can improve your presentation skills and create a compelling and engaging talk that resonates with your audience.

Tips to Make an Effective Research Presentation

- Tip 1: Start confidently

- Tip 2: Eye To Eye Contact With the Audience

- Tip 3: Welcome Your Audience

- Tip 4: Adjust your Voice

- Tip 5: Memorize your Opening Line

- Tip 6: Use the words “ ‘Think for while’, ‘Imagine’, ‘Think of’, ‘Close Your Eyes’ ”

- Tip 7: Story Telling

- Tip 8: Facts and Statistics

- Tip 9: Power of “Pause”

- Tip 10: Quote a Great Researcher

- Tip 11: Begin with a Video

- Tip 12: Avoid using Filler Words

Starting your presentation confidently is essential as it sets the tone for the rest of your presentation. It will help you grab your audience’s attention and make them more receptive to your message. Here are a few ways you can start confidently.

- Begin with a self-introduction: Introduce yourself to the audience and establish your credibility. Briefly mention your educational background, your professional experience, and any relevant achievements that make you an authority on the topic. For example, “Good morning everyone, my name is John and I’m a researcher at XYZ University. I have a Ph.D. in molecular biology, and my research has been published in several reputable journals.”

- Introduce the topic: Clearly state the purpose of your presentation and provide a brief overview of what you’ll be discussing. This helps the audience understand the context of your research and what they can expect from your presentation. For example, “Today, I’ll be presenting my research on the role of DNA repair mechanisms in cancer development. I’ll be discussing the current state of knowledge in this field, the methods we used to conduct our research and the novel insights we’ve gained from our findings.”

- Start with a strong opening statement: Once you’ve introduced yourself and the topic, start your presentation confidently with a statement that captures the audience’s attention and makes them curious to hear more. As mentioned earlier, you could use a strong opening statement, a powerful visual aid, or show enthusiasm for your research. For example:

- “Have you ever wondered how artificial intelligence can be used to predict user behaviour? Today, I’ll be sharing my research on the latest AI algorithms and their potential applications in the field of e-commerce.”

- “Imagine a world where cybersecurity threats no longer exist. My research is focused on developing advanced security measures that can protect your data from even the most sophisticated attacks.”

- “Think for a moment about the amount of data we generate every day. My research focuses on how we can use machine learning algorithms to extract meaningful insights from this vast amount of data, and ultimately drive innovation in industries ranging from healthcare to finance.”

By following these steps, you’ll be able to start your research presentation confidently, establish your credibility and expertise, and create interest in your topic.

Speaking confidently as an invited speaker can be a daunting task, but there are ways to prepare and feel more confident. One such way is through practising yoga. Yoga is a great tool for reducing stress and anxiety, which can be major barriers to confident public speaking.

By practising yoga, you can learn to control your breathing, calm your mind, and increase your focus and concentration. All of these skills can help you feel more centred and confident when it’s time to give your presentation.

If you’re interested in learning more about the benefits of yoga, check out our blog post on the subject YOGA: The Ultimate Productivity Hack for Ph.D. Research Scholars and Researchers .

If you’re ready to dive deeper and start your own yoga practice, be sure to download my e-book on :

Unlock Your Research Potential Through Yoga: A Research Scholar’s Companion

A large number of audiences in the presentation hall make you feel jittery and lose your confidence in no time. This happens because you are seeing many of the audience for the first time and you don’t know their background and their knowledge of the subject in which you are presenting.

The best way to overcome this fear is to go and attack the fear itself. That is come at least 10-15 minutes early to the conference room and start interacting with the people over there. This short span of connectivity with a few of the audience will release your tension.

When you occupy the stage for presenting, the first thing you need to do is gaze around the room, establish one-to-one eye contact, and give a confident smile to your audience whom you had just met before the start of the presentation.

Just gazing around the presentation hall will make you feel connected to everyone in the hall. Internally within your mind choose one of the audience and turn towards him/her make eye contact and deliver a few sentences, then proceed to the next audience and repeat the same set of steps.

This will make everyone in the room feel that you are talking directly to them. Make the audience feel that you are engaging with them personally for this topic, which makes them invest fully in your topic.

The third tip for making an effective research presentation is to welcome your audience. This means taking a few minutes to greet your audience, introduce yourself, and set the tone for your presentation. Here are a few ways you can welcome your audience:

- Greet your audience: Start by greeting your audience with a smile and a warm welcome. This will help you establish a connection with your audience and put them at ease.

- Introduce yourself: Introduce yourself to the audience and give a brief background on your expertise and how it relates to your presentation. This will help your audience understand your qualifications and why you’re the right person to be delivering the presentation.

- Explain the purpose of your presentation: Explain to your audience why you’re presenting your research and what they can expect to learn from your presentation. This will help your audience understand the context of your research and what they can expect from your presentation.

- Set the tone: Set the tone for your presentation by giving a brief overview of your presentation structure and what your audience can expect throughout your presentation. This will help your audience understand what to expect and keep them engaged.

Here are a few examples of how you can welcome your audience:

- If you’re presenting to a group of industry professionals, welcome them by acknowledging their expertise and experience. This will show that you value their knowledge and experience.

- If you’re presenting to a group of students or academics, welcome them by acknowledging their interest in your research area. This will help you establish a connection with your audience and show that you’re excited to share your research with them.

- If you’re presenting to a mixed audience, welcome them by acknowledging their diversity and the different perspectives they bring to the presentation. This will help you set an inclusive tone and show that you’re open to different viewpoints.