Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

The following is a scenario of a patient who experienced ruptured esophageal varices. The patient, Nora Allen, a 55-year-old female presented to the emergency department (ER) on May 5, 2017 just after 10:00 a.m., with complaints of two episodes of melena that morning.

Upon further assessment, her husband expressed concern that his wife had been drinking again because her behavior had seemed “strange”. He had these concerns because his wife had a 20-year history of alcohol abuse and was “under a lot of stress” due to the recent loss of her job. Nora has a history of alcoholism, cirrhosis of the liver, coronary artery disease (CAD) and anemia.

Upon assessment in the ER, her vital signs were 110/76, 85bpm, 95% on room air, 98.2ºF, 22 breaths/min. Neurologically, she was oriented to person, time and situation, but was confused as to where she was. Her pupils were 2mm and sluggish to light. She appeared anxious, was slurring her speech and had visible hand tremors. She reported nausea and melena, and had obvious ascites with a distended firm abdomen. An occult stool was positive and her skin was cool and clammy with poor skin turgor and weak pedal pulses. The remainder of her body systems were within normal limits.

While in the ER, 1 L normal saline (NS) bolus was administered, labs were drawn, a foley catheter was inserted. A blood glucose (finger stick) was taken. She was kept NPO for a scheduled endoscopy later that day.

At 1300, the patient began vomiting and was given an emesis bag. At 1310, Nora’s husband quickly informed the nurse that his wife was violently vomiting bright red blood. On reassessment, the patient’s BP was 94/63 and the HR was 98bpm. The patient was started on octreotide 50mcg bolus. She was intubated for airway protection and to prevent aspiration. She was administered 1 unit of packed red blood cells (PRBCs) and was taken immediately to the gastrointestinal lab for a STAT endoscopy for possible esophageal banding therapy.

The patient was diagnosed with ruptured esophageal varices and sent to the ICU for close observation and monitoring after successful placement of 12 esophageal bands. Overnight, the patient was administered another (1) unit of PRBC, to maintain a hemoglobin greater than 8 g/dL. The following morning at 10:45 a.m. Mrs. Allen was extubated after a successful sedation vacation and spontaneous breathing trial.

When the patient was stable, she was transferred to the medical-surgical floor for observation and case management. On the floor, the patient was educated regarding the reason for the ruptured esophageal varices and taught about her new prescription, propranolol, which, if taken correctly, should decrease the chance of a re-bleed. Lastly, although the patient was resistant to the cessation of alcohol consumption, she met with case management and was educated on alcohol cessation programs and support groups, such as alcoholics anonymous.

Discussion Questions

- If you were the case manager who was educating this unwilling patient about the various rehabilitation facilities, how would you have approached the situation?

- In this scenario, the patient’s vomiting caused the varix to rupture. What type of interventions or nursing assessment tools could have been utilized to prevent vomiting and subsequent rupture of the varix?

- During this scenario, the patient began to vomit large amounts of blood. How would you deal with family members who are in the room who may be shocked about this sudden change in the patient’s condition while also taking care of your patient?

Nursing Case Studies by and for Student Nurses Copyright © by jaimehannans is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Patient Education Reference Center - Case Scenario #1 - Esophageal Varices

Nov 13, 2018 • knowledge, information.

Clinical Case Scenario #1

Health Education for a Male Inpatient with Esophageal Varices

Clinical Scenario

Forty five year old G.K. is admitted to the hospital’s Emergency Department. He is vomiting large amounts of blood. He is mildly intoxicated but alert. His pulse is fast and thready. An IV of normal saline 0.9% is started; he is given oxygen by mask, and is prepared to receive multiple units of packed red blood cells as needed (blood transfusions). He is transferred to the endoscopy lab for an immediate procedure to investigate the source of the bleeding.

In the Endoscopy lab it will be determined that he has bleeding esophageal varices, and a procedure will be performed to stop the bleeding. He will then be admitted to the hospital for observation.

Nursing goals include explanation of all procedures he is to undergo, given his level of comprehension, and written handouts for review later when fully conscious.

Searching in Patient Education Reference Center (PERC)

Esophageal varices: The nurse uses PERC to gather the handout she will need for Mr. K. From the Home page, she searches for esophageal varices She chooses the Conditions source type She reads #1: Esophageal varices and checks the paper to glean meaningful information to share with Mr. K. She prints the hospital-customized handout.

Blood transfusion: The nurse searches Procedures & Lab Tests and finds Blood Transfusion for Mr. K.

Endoscopy The nurse returns to the results list and chooses the Procedure source type. She prints Upper GI Endoscopy and shares the paper with Mr. K before he is sedated, answering his questions and providing reassurance.

The gastroenterologist performs the endoscopy and locates the bleeding site. He uses Endoscopic Band Ligation to stop the bleeding. M. K. recovers quickly and is returned to his room.

Mr. K. is visited by the hospital’s social worker to discuss the potentiality of alcoholism and is referred to a community services program for follow up. The Social worker uses PERC to search for alcoholism. She prints Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse and reviews the paper with Mr. K.

Following his hospital stay, Mr. K is discharged home with Social Services support. The nurse chooses the Discharge Instructions source type and prints both Discharge Instructions for Upper GI endoscopy and Discharge Instructions for Endoscopic Band Ligation . She discusses his instructions which include important follow up instructions such as seeing his doctor within 2 days and avoiding alcohol.

Following Mr. K.’s discharge, the nurse adds all patient education papers to folders and their related subfolders in PERC, to make available to the other members of the multidisciplinary team.

Handouts for Acute Care Folders in PERC

Blood and Blood Products Blood transfusion GI : esophageal varices GI : Procedures Upper GI Endoscopy, Upper Band Ligation GI : Discharge info Discharge Instructions for Upper GI endoscopy, Discharge Instructions for Endoscopic Band Ligation. Psychosocial : Alcoholism

NurseStudy.Net

Nursing Education Site

Esophageal Varices Nursing Diagnosis and Care Plan

Last updated on February 20th, 2023 at 09:15 am

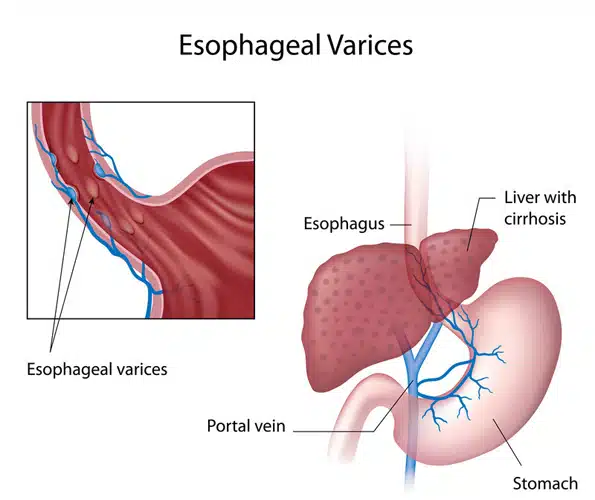

Esophageal varices are veins that are abnormally enlarged and are usually found on the lower two-thirds of the esophagus.

They arise from the blockage of the portal vein of the liver. Instead of flowing through the portal vein, the blood flows through the smaller blood vessels, which eventually causes venous enlargement, leakage, or even rupture.

The treatment plan for esophageal varices is mainly focused on the prevention or stoppage of their rupture and bleeding.

Signs and Symptoms of Esophageal Varices

Unless they are bleeding, esophageal varices may not present any signs or symptoms. A patient with bleeding esophageal varices may show:

- Hematemesis or vomiting large amounts of blood

- Black, tarry or bloody stools

- Lightheadedness

- Loss of consciousness due to severe bleeding

Esophageal varices related to liver disease may have the following symptoms:

- Jaundice or yellow coloration of eyes and skin

- Ascites or abdominal fluid buildup

- Getting easily bruised

Causes and Risk Factors of Esophageal Varices

Liver disease cause scarring of the liver tissue known as cirrhosis of the liver. The liver scar tissues facilitate the backing up of the blood flow, thus increasing the pressure in the liver’s portal vein.

This condition is known as portal hypertension. To compensation for the increased pressure, the blood is forced to flow in smaller veins, including those veins that are found in the esophagus’ lowest part.

Their small size means that they cannot accommodate a large volume of blood. The veins may balloon, rupture, and bleed in time.

Aside from liver cirrhosis, thrombosis or the formation of blood clot in the portal vein or splenic vein may cause esophageal varices.

Parasitic infection of the liver, such as schistosomiasis found in Asia, Africa, Caribbean countries, and South America, can cause liver damage and lead to the formation of esophageal varices.

Alcohol abuse may lead to the rupture and bleeding of esophageal varices.

Complications of Esophageal Varices

Bleeding is the most life-threatening complication of esophageal varices. Internal bleeding may result to shock due to loss of a significant amount of blood, and this is fatal.

Another complication of esophageal varices is the increased risk for another rupture and bleeding episode of other varices.

Diagnosis of Esophageal Varices

- Physical examination and history taking – to check for any hematemesis, black tarry or blood stools, as well as to explore any alcohol abuse or history of liver disease

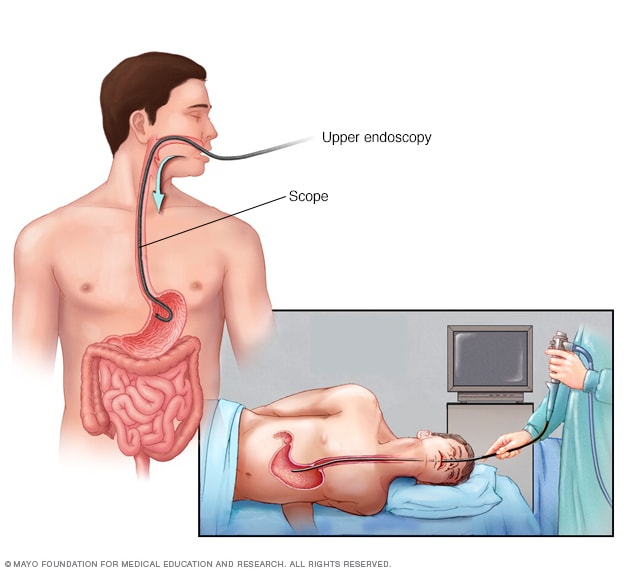

- Endoscopy – to visualize the gastrointestinal system, looking for any dilation of veins and any presence of red spots or red streaks which may indicate a very high risk of rupture and bleeding. Treatment of bleeding esophageal varices can also be done during this exam.

- Capsule endoscopy – to perform endoscopy but with the use of a capsule that has a camera in it. The patient swallows this like a pill, and the camera takes images of the GI tract as it goes down. This is more expensive than the usual endoscopy, but can be helpful for those who cannot tolerate the endoscope tube

- Imaging – CT scan and ultrasound Doppler of the portal and splenic veins

Treatment of Esophageal Varices

- Portal vein drugs. Beta blockers such as propanolol and nadolol can help treat portal hypertension by lowering the blood pressure in the portal vein. These reduce the risk for esophageal varices rupture and bleeding. After a bleeding episode, drugs like vasopressin and octreotide can be prescribed for up to 5 days to reduce the blood flow in the portal vein.

- Endoscopic band ligation. This procedure can be done while the patient is undergoing endoscopic exam and the doctor finds out that there are esophageal varices that are bleeding, or at high risk of rupture and bleed in the future. The doctor uses an elastic band to tie off the veins that are bleeding.

- Balloon tamponade. To stop the bleeding, this procedure involves inflating a balloon temporarily (for up to 24 hours) in order to place pressure on the esophageal varices.

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS). This procedure is used to create a diversion of the blood flow away from the portal vein by means of making a shunt or an opening between the hepatic vein and the portal vein.

Esophageal Varices Nursing Diagnosis

Nursing care plan for esophageal varices 1.

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Bleeding secondary to esophageal varices

Desired Outcome : The patient will be able to avoid having any frank or occult bleeding and will remain hemodynamically stable.

Nursing Care Plan for Esophageal Varices 2

Nursing Diagnosis: Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements related to digestive tract bleeding secondary to esophageal varices, as evidenced by hematemesis, weight loss, nausea and vomiting, loss of appetite and dizziness/ lightheadedness

Desired Outcome : The patient will be able to achieve a weight within his/her normal BMI range, demonstrating healthy eating patterns and choices.

Nursing Care Plan for Esophageal Varices 3

Risk for Decreased Cardiac Output

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Decreased Cardiac Output related to bleeding secondary to esophageal varices .

Desired Outcomes:

- The patient will exhibit adequate cardiac output after the bleeding is controlled as evidenced by stable vital signs, normal peripheral perfusion, adequate intake and output, warm and dry skin, absence of breathing difficulties, and normal level of consciousness.

- The patient will be able to demonstrate self-care activities to improve gastrointestinal and cardiac health.

Nursing Care Plan for Esophageal Varices 4

Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume related to nausea and hematemesis secondary to esophageal varices.

- The patient will verbalize a decrease in the severity of nausea and vomiting.

- The patient will maintain adequate fluid volume while waiting for treatment as evidenced by stable vital signs, adequate skin perfusion, strong peripheral pulses, alert mental state, and urine output greater than 30ml per hour.

Nursing Care Plan for Esophageal Varices 5

Risk for Injury

Nursing Diagnosis: Risk for Injury related to lightheadedness secondary to bleeding esophageal varices.

- The patient will be able to prevent injury by doing activities within the parameters of limitation and modifying the environment to adapt to the patient’s capacity.

- The patient will be able to perform activities of daily living with minimal supervision and maintain a treatment regimen to regain balance and increase compliance.

More Esophageal Varices Nursing Diagnosis

- Risk for Shock

- Disturbed Body Image

- Deficient Knowledge

Nursing References

Ackley, B. J., Ladwig, G. B., Makic, M. B., Martinez-Kratz, M. R., & Zanotti, M. (2020). Nursing diagnoses handbook: An evidence-based guide to planning care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Gulanick, M., & Myers, J. L. (2022). Nursing care plans: Diagnoses, interventions, & outcomes . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Ignatavicius, D. D., Workman, M. L., Rebar, C. R., & Heimgartner, N. M. (2020). Medical-surgical nursing: Concepts for interprofessional collaborative care . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Silvestri, L. A. (2020). Saunders comprehensive review for the NCLEX-RN examination . St. Louis, MO: Elsevier. Buy on Amazon

Disclaimer:

Please follow your facilities guidelines and policies and procedures. The medical information on this site is provided as an information resource only and is not to be used or relied on for any diagnostic or treatment purposes. This information is not intended to be nursing education and should not be used as a substitute for professional diagnosis and treatment.

Anna Curran. RN, BSN, PHN

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

The Royal Children's Hospital Melbourne

- My RCH Portal

- Health Professionals

- Patients and Families

- Departments and Services

- Health Professionals

- Departments and Services

- Patients and Families

- Research

Nursing guidelines

- About nursing guidelines

- Nursing guidelines index

- Developing and revising nursing guidelines

- Other useful clinical resources

- Nursing guideline disclaimer

- Contact nursing guidelines

In this section

Acute management of an oesophageal variceal bleed

Introduction

Oesophageal varices (and indeed any varices) are a rare but serious complication of portal hypertension. Portal hypertension is defined by an increase in pressure within the portal circulatory system and is caused by an increase in vascular resistance in blood flow through the liver. In RCH’s patient population, portal hypertension is frequently a result of biliary atresia, but it can also be a manifestation of post-hepatic, pre-hepatic (e.g. portal vein obstruction), or other intra-hepatic problems such as cystic fibrosis, congenital hepatic fibrosis or other cirrhosis. With increased resistance in the portal vascular system, blood begins to shunt through collateral systemic vessels to return to the vena cava. Prolonged elevation in portal vein pressure causes dilatation of the collateral vessels, which can form internal varices in the rectum and varices in the gastro-oesophageal veins. Oesophageal variceal bleeds occur when the variceal wall tension exceeds the wall strength and subsequently rupture. Children with liver disease also have liver dysfunction, which results in clotting cascade problems and a deficit in Vitamin K-dependent factors. This increases the risk of significant haemorrhage in this patient group.

In several large studies of children with portal hypertension, approximately two thirds presented with haematemesis (vomiting blood) or melaena (blood in stool/dark stools caused by upper GI bleeds), usually from rupture of an oesophageal varix. Twenty to thirty percent of children with biliary atresia have variceal bleeds and tend to develop varices early, with an estimated risk of bleeding of fifteen percent before the age of two. Mortality rates associated with large bleeds range from zero to fifteen percent.

The aim of this guideline is to assist nurses and other health professionals in the management of infants and children with oesophageal varices to minimise risk of variceal bleeding. This guideline will also outline the management of an acute oesophageal variceal bleed.

Definition of Terms

- GI - gastrointestinal

- NGT – Nasogastric tube

- PPIs – Proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole, pantoprazole)

Assessment of Patients with Known or Suspected Varices

- Complete primary assessment as per Clinical Guidelines (Nursing) : Nursing assessment

- Routine observations as per Clinical Guidelines (Nursing): Observation and Continuous Monitoring

- Monitor for signs of hypovolaemia: e.g. tachycardia, hypotension.

- Investigations: FBE, UEC, VBG, Coagulation Screen, Group & hold, blood cultures, BGL, ammonia, see specimen collection .

- Monitor for upper GI bleeding (e.g. haematemesis or coffee ground vomit)

- Monitor for melaena or fresh blood in stools.

- Capture clinical images of melaena & haematemesis to guide volumes of blood loss.

- Monitor for abdominal distension or protruding umbilical veins, especially when seen in combination with other listed symptoms.

- Assess coagulation screen for risk of bleeding.

- Maintain strict fluid balance including measurement or estimation of losses, including urine output.

- Monitor for neurological changes.

Management of Children with Known or Suspected Varices

- Stylet should be removed.

- Insertion should be carried out by senior staff members or medical personnel in high-risk patients. Eg those who have had previous GI bleeds, those with significant coagulopathies, those with high grades varices as identified by treating team.

- NGT should not have a gastric aspirate taken from the tube. Instead, position should be confirmed by x-ray.

- Ensure patient has valid blood product consent on file (see Consent- Informed Procedure )

- Family should be provided with education on varices and at home emergency management plan by Liver & Intestinal Transplant Clinical Nurses Consultants or Gastroenterology team members.

- Patients should have routine surveillance gastroscopies to monitor status and progression of varices. Banding or sclerotherapy can be undertaken as required. Frequency of gastroscopies is dictated by treating gastroenterologist.

- Patients should have the following investigations prior to gastroscopies: FBE, UEC, coagulation screen, group & hold.

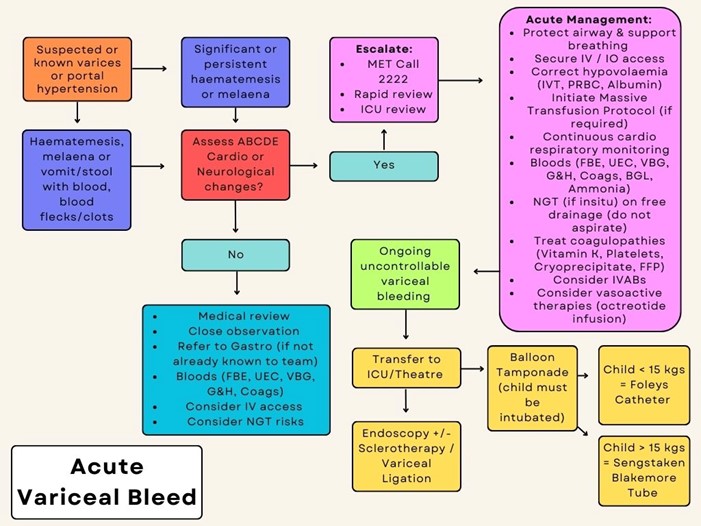

Acute Management of Variceal Bleed (refer to algorithm overleaf)

- Seek urgent medical/ ICU review/ MET (ext. 2222).

- Protect airway, support breathing as required (see Resuscitation guidelines ). Give oxygen to patients with significant circulatory impairment or shock.

- Secure large bore IV access.

- Consider need to activate Massive Haemorrhage and Critical Bleeding Procedure .

- No more than 20mL/kg NaCl bolus. Albumin should also be given if further fluid administration is required.

- RBCs if Hb <70g/L.

- Maintain strict fluid balance.

- Octreotide, IV bolus followed by IV infusion. Refer to Medication Guideline: Octreotide for dosing

- Always discuss with a gastroenterology fellow or consultant before commencing vasoactive therapy.

- Once bleeding controlled, slow wean of octreotide as per Octreotide Medication Guideline

- Monitor BGL 6 hourly whilst on octreotide infusion due to risk of hypoglycaemia and/or hyperglycaemia – escalate any abnormal results to treating team

- Continuous cardiorespiratory monitoring (see Clinical Guidelines (Nursing): Observation and Continuous Monitoring ).

- If NGT in situ, place on free drainage. Do NOT aspirate NGT . NGT should only be inserted under endoscopic guidance or with gastroenterologist consent.

- Consider treating coagulopathies (vitamin K, platelets, cryoprecipitate and FFP).

- If bleeding is ongoing and uncontrollable, patient will require Balloon Tamponade (Foleys Catheter if child <15kg or Sengstaken Blakemore tube if child>15kg). This will ideally be performed in the ICU or theatre environment.

- Transfer to ICU or theatre for management as clinically appropriate

- Consider prophylactic intravenous antibiotics.

- Patient should be kept nil by mouth (NBM) until bleeding controlled and medically cleared for oral intake.

- Whilst NBM, all regular medications should be given IV.

- Consider use of PPI: IV whilst NBM followed by oral once cleared for oral intake.

Management of Patients with Recent Variceal Bleeding/Banding

- Patients should remain nil by mouth (NBM) post variceal bleeding or banding and grade up diet as directed by treating gastroenterologist.

- Ensure patient has a valid group and hold in case requires transfusion.

- Maintain IV access.

- Ensure foley catheter is at bedside in case of re-bleed. If leaving the ward, patient must take catheter with them.

Special considerations

- For CVAD management (see Central Venous Access Device )

- Blood transfusion safety adherence (see Blood Transfusion Procedure ).

- Massive Transfusion Protocol (see Massive Haemorrhage and Critical Bleeding Procedure ).

- If body fluid splash (see Procedure Needlestick Injuries and Blood-Body Fluid Exposures ).

Algorithm for Management of Acute Variceal Bleed

- PICU Guidelines: Liver Protocols

- RCH Liver Transplant Protocol

- RCH Enteral Feeding and Medication Administration CPG

Clinician websites

- American College of Gastroenterology Practice Guideline

- British Society of Gastroenterology Guidelines

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Clinical Guideline

- World Gastroenterology Guideline

- NICE Guideline: Stent Insertion for Bleeding Oesophageal Varices

Information for parents

- Children’s Liver Disease Foundation

- Starship Parent Guide to Portal Hypertension

- Starship Parent Guide to Liver Transplant

*Please remember to read the disclaimer .

The development of this nursing guideline was coordinated by Rachel Horn, CNC, Gastroenterology, and Laura Davies, CNS, Cockatoo, approved by the Nursing Clinical Effectiveness Committee. Updated December 2023.

Evidence table

- Editorial Board

- Special Issues

- Submit Manuscript

- Articles in Press

- Current Issue

- Author Guidelines

- Indexing Completed

Esophageal varices incidences are increasing by nearly 5% every year. Esophageal varices are the causes of bleeding in approximately 18% of hospital admissions for upper GI bleeding.

Objective: The purpose of this study is to understand the cause, clinical manifestations and treatment course for esophageal varices.

Material and methods: Detailed clinical history and physical examination was done. All the pertinent investigations were studied thoroughly of the selected case.

Results: The esophageal varices is confirmed with the help of upper gastrointestinal gastroscopy and repaired by banding.

Conclusion: Esophageal varices usually go undiagnosed due to early common symptoms. Hematemesis is one of the suggestive of esophageal varices and OGD is only the confirmative diagnosis for it. The prognosis depends usually better if treatment received on time.

INTRODUCTION

Esophageal varices are abnormal, enlarged veins in the tube that connects the throat and stomach. Variceal rupture is governed by Laplace's law. Increased wall tension is the end result of increased intravariceal pressure, increased diameter of the varices and reduced wall thickness. The variceal wall thickness can be evaluated visually by the presence of red wale markings. These markings reflect areas where the wall is especially thin [1]. Variceal rupture often occurs at the level of the gastroesophageal junction, where the varices are very superficial and thus have thinner walls. Esophageal varices are the major complication of portal hypertension [2].

RISK FACTORS

· Large esophageal varices

· Red marks on the esophageal varices as seen on a lighted stomach scope (endoscopy)

· Portal hypertension

· Severe cirrhosis

· A bacterial infection

· Excessive alcohol use

· Excessive vomiting

· Constipation

· Severe coughing bouts

DIAGNOSTIC INVESTIGATIONS

· Blood tests

· Endoscopy

· Imaging tests, such as CT and MRI scans

ESOPHAGEAL VARICES SYMPTOMS

· Hematemesis

· Stomach pain

· Light-headedness or loss of consciousness

· Melena (black stools)

· Bloody stools (in severe cases)

· Shock (excessively low blood pressure due to blood loss that can lead to multiple organ damage)

Therapeutic approaches are variceal ligation (banding) and sclerotherapy. Banding is a medical procedure which uses elastic bands for constriction. Banding may be used to tie off blood vessels in order to stop bleeding, as in the treatment of bleeding esophageal varices. The band restricts blood flow to the ligated tissue, so that it eventually dies and sloughs away from the supporting tissue.

Sclerotherapy is a form of treatment where a doctor injects medicine into blood vessels or lymph vessels that causes them to shrink. It is commonly used to treat varicose veins or so-called spider veins. The procedure is non-surgical, requiring only an injection.

An 85 year old patient with known case of diabetes mellitus, hypertension since last 20 years and status post percutaneous transluminal coronary (2002, 2011 and 2015). Patient had no history of any bad habits like cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption or any other drug substance. Patient was found semiconscious at home at night suddenly and when aroused by relatives, patient had hematemesis of around 500 ml at home. Patient was brought to hospital. The patient had complaints of malena and acidity since one week. Patient was investigated in the form of alkaline phosphatase, alpha fetoprotein, serum glutamic pyruvic transaminase, SGOT, bilirubin, glucose, IgG, CBC, USG KUB, ABG, Electrocardiogram, APTT, ESR, USG whole abdomen.

CBC shows Hb less than 7 g/dl. USG whole abdomen was suggestive of reduced size of liver with diffusely altered echo texture and surface irregularity, suggestive of chronic liver parenchymal disease. Few small tortuous mesenteric venous collaterals, could be suggestive of portal hypertension.

Upper gastrointestinal gastroscopy was suggestive of esophageal varices. One band applied endoscopically and further, patient was managed with anti-diabetics, antacid, analgesic, antibiotic, beta blocker, statin and other supportive care.

Esophageal varices usually go undiagnosed until hematemesis occur. Hematemesis is a medical emergency and always occur due to upper GI tract bleeding. The color is usually bright red in color. The hematemesis is treated with somatostatin analogue (e.g. Octreotide) or vasopressin (e.g. Terlipressin); it helps to reduce splanchnic blood flow. The Glasgow-Blatch Ford Bleeding scoring system score is used to determine the risk. This scale is purely based on clinical and biochemical parameters. The warning signs of esophageal varices is dizziness even when awake, weight loss, low Hb level, complaints of acidity, heartburn, hematemesis and malena.

Patients with hypertension and diabetes have poor prognosis as medicines have adverse effects on liver which can lead to liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension as well. At advanced age, the banding is done for symptomatic treatment only as no other option is available at this age.

1. Hilzenrat N, Sherker AH (2012) Esophageal varices: Pathophysiology, approach and clinical dilemmas. Int J Hepatol 2012: 35-40.

2. Maruyama H, Yokosuka O (2012) Pathophysiology of portal hypertension and esophageal varices. Int J Hepatol 2012: 38-42.

QUICK LINKS

- SUBMIT MANUSCRIPT

- RECOMMEND THE JOURNAL

- SUBSCRIBE FOR ALERTS

RELATED JOURNALS

- Advance Research on Endocrinology and Metabolism (ISSN: 2689-8209)

- Journal of Otolaryngology and Neurotology Research(ISSN:2641-6956)

- Journal of Infectious Diseases and Research (ISSN: 2688-6537)

- Journal of Blood Transfusions and Diseases (ISSN:2641-4023)

- Journal of Rheumatology Research (ISSN:2641-6999)

- Journal of Pathology and Toxicology Research

- Advance Research on Alzheimers and Parkinsons Disease

Newsletter signup

- Open Access

- A-Z Journals

- Editor in Chiefs

Journal Groups

- Engineering

- Life Sciences

- Pre-Nursing

- Nursing School

- After Graduation

Esophageal Varices: Patho, Manifestations, & Diagnostics

Jump to Sections

- What is a Varice?

Esophageal Varices Causes

Signs and symptoms of esophageal varices, esophageal varices assessment & diagnostics, esophageal varices nclex question.

Esophageal varices are complications due to liver diseases or dysfunctions. It’s important to identify and treat the underlying cause of them to prevent complications such as bleeding and improve patient outcomes.

You can think of esophageal varices as the result of having a plumbing backup.

What is a Varice? (The Septic Tank Analogy)

Associating esophageal varices with having a backup of septic tank content is helpful since you can compare the liver to the body’s septic tank. If the septic tank becomes clogged or has hardened, there will be an immediate backup from the system.

Toilets and sinks will have a backflow of waste products – water will not drain properly from the shower.

The Liver: The Body’s Septic Tank

As food is chewed inside the mouth, it goes down the esophagus, then into the stomach to be broken down by gastric juices. Digested food now goes inside the duodenum, the first part of the small intestine.

After the duodenum , the contents are sucked into the portal vein that goes through the pancreas. This process is referred to as the first-pass phenomenon concerning medications.

Hardening of the Liver

When the liver hardens due to some type of scarring, for instance:

- Cirrhosis that’s basically the production of scar tissue in the liver

Whatever the condition is, the backing up of blood into the portal vein is the main cause of esophageal varices.

Esophageal varices are primarily caused by increased pressure in the portal vein system, which can result from various underlying medical conditions. Some common causes of esophageal varices include:

- Cirrhosis : Cirrhosis scarring can obstruct blood flow through the liver, leading to increased pressure in the portal vein system.

- Hepatitis : Chronic hepatitis, a viral infection that causes inflammation and scarring of the liver, can also lead to esophageal varices.

- Congenital disorders : Rare genetic disorders, such as Budd-Chiari syndrome or portal vein thrombosis, can obstruct the portal vein and lead to increased pressure in the portal vein system.

- Thrombosis : Blood clots in the portal vein or its branches can cause portal hypertension and lead to the development of esophageal varices.

- Schistosomiasis : A parasitic infection common in parts of Africa and South America, schistosomiasis can cause liver damage and develop esophageal varices.

Since there is the backing up of blood or fluid inside the esophagus, the following manifestations will occur:

- Esophageal bleeding

- Vomiting with blood

- Bloody stools

- Decreased blood pressure (due to decreased volume caused by bleeding)

- A skyrocketing heart rate. Due to the decreased hemoglobin, the heart will compensate by pumping faster to distribute oxygen to the body’s different systems.

- Tachycardia

One of the main diagnostic procedures for patients with esophageal varices is esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) . With EGD, a tube with a camera is inserted to visualize the inside of the esophagus.

Liver function tests are also done to check the status of the liver through abnormalities with alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

The hemoglobin and hematocrit levels are also tested because if there is bleeding anywhere in the body, the lab results for H&H will be low.

When a patient comes in with perfused bleeding from his mouth, should you do an EGD?

Answer: No . The airway is the priority in any situation. In this case, if the patient is vomiting blood, stopping the bleeding is paramount.

The first thing to do is to relieve the patient of the blood by suctioning its mouth, and once the bleeding ceases, that’s when an EGD is done.

Aside from suctioning, there are other procedures done to stop the bleeding, namely:

- Medications

- Inserting a balloon catheter into the esophagus

Study More in Less Time

Using a study tool can help you keep engaged and at a steady pace when studying conditions like esophageal varices.

SimpleNursing is trusted by nursing students to retain more nursing school material while cutting down on study hours. We have adaptive exams to tailor the learning experience to each individual learner’s needs, interests, and abilities.

Get a better understanding of your nursing material .

Want to ace Nursing School Exams & the NCLEX?

Make topics click with easy-to-understand videos & more. We've helped over 1,000,000 students & we can help you too.

Share this post

Nursing students trust simplenursing.

SimpleNursing Student Testimonial

Most recent posts.

How to Remove a PICC Line

Does the idea of removing a PICC line make you feel uneasy? You’re not alone.…

What to Do If You’re Retaking the NCLEX

Jump to Sections Is the NCLEX harder the second time? What Repeat NCLEX Test Takers…

The NCLEX-RN Test Plan for 2024

Embarking on a nursing career requires not only dedication and passion in school, but also…

How to Calculate Heart Rate on an ECG with the 6 Second Method

If you’ve ever watched a medical drama (any “Grey’s Anatomy” fans here?), you’ve probably seen…

Find what you are interested in

- Patient Care & Health Information

- Diseases & Conditions

- Esophageal varices

- Upper endoscopy

During an upper endoscopy, a healthcare professional inserts a thin, flexible tube equipped with a light and camera down the throat and into the esophagus. The tiny camera provides a view of the esophagus, stomach and the beginning of the small intestine, called the duodenum.

If you have cirrhosis, your health care provider typically screens you for esophageal varices when you're diagnosed. How often you'll have screening tests depends on your condition. Main tests used to diagnose esophageal varices are:

Endoscopic exam. A procedure called upper gastrointestinal endoscopy is the preferred method of screening for esophageal varices. An endoscopy involves inserting a flexible, lighted tube called an endoscope down the throat and into the esophagus. A tiny camera on the end of the endoscope lets your doctor examine your esophagus, stomach and the beginning of your small intestine, called the duodenum.

The provider looks for dilated veins. If found, the enlarged veins are measured and checked for red streaks and red spots, which usually indicate a significant risk of bleeding. Treatment can be performed during the exam.

- Imaging tests. Both abdominal CT scans and Doppler ultrasounds of the splenic and portal veins can suggest the presence of esophageal varices. An ultrasound test called transient elastography may be used to measure scarring in the liver. This can help your provider determine if you have portal hypertension, which may lead to esophageal varices.

More Information

- Capsule endoscopy

The primary aim in treating esophageal varices is to prevent bleeding. Bleeding esophageal varices are life-threatening. If bleeding occurs, treatments are available to try to stop the bleeding.

Treatment to prevent bleeding

Treatments to lower blood pressure in the portal vein may reduce the risk of bleeding esophageal varices. Treatments may include:

- Medicines to reduce pressure in the portal vein. A type of blood pressure drug called a beta blocker may help reduce blood pressure in your portal vein. This can decrease the likelihood of bleeding. Beta blocker medicines include propranolol (Inderal, Innopran XL) and nadolol (Corgard).

Using elastic bands to tie off bleeding veins. If your esophageal varices appear to have a high risk of bleeding, or if you've had bleeding from varices before, your health care provider might recommend a procedure called endoscopic band ligation.

Using an endoscope, the provider uses suction to pull the varices into a chamber at the end of the scope and wraps them with an elastic band. This essentially "strangles" the veins so that they can't bleed. Endoscopic band ligation carries a small risk of complications, such as bleeding and scarring of the esophagus.

Treatment if you're bleeding

Bleeding esophageal varices are life-threatening, and immediate treatment is essential. Treatments used to stop bleeding and reverse the effects of blood loss include:

- Using elastic bands to tie off bleeding veins. Your provider may wrap elastic bands around the esophageal varices during an endoscopy.

- Taking medicines to slow blood flow into the portal vein. Medicines such as octreotide (Sandostatin) and vasopressin (Vasostrict) slow the flow of blood to the portal vein. Medicine is usually continued for up to five days after a bleeding episode.

Diverting blood flow away from the portal vein. If medicine and endoscopy treatments don't stop the bleeding, your provider might recommend a procedure called transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS).

The shunt is an opening that is created between the portal vein and the hepatic vein, which carries blood from your liver to your heart. The shunt reduces pressure in the portal vein and often stops bleeding from esophageal varices.

But TIPS can cause serious complications, including liver failure and mental confusion. These symptoms can develop when toxins that the liver normally would filter are passed through the shunt directly into the bloodstream.

TIPS is mainly used when all other treatments have failed or as a temporary measure in people awaiting a liver transplant.

Placing pressure on varices to stop bleeding. If medicine and endoscopy treatments don't work, your provider may try to stop bleeding by applying pressure to the esophageal varices. One way to temporarily stop bleeding is by inflating a balloon to put pressure on the varices for up to 24 hours, a procedure called balloon tamponade. Balloon tamponade is a temporary measure before other treatments can be performed, such as TIPS .

This procedure carries a high risk of bleeding recurrence after the balloon is deflated. Balloon tamponade also may cause serious complications, including a rupture in the esophagus, which can lead to death.

- Restoring blood volume. You might be given a transfusion to replace lost blood and a clotting factor to stop bleeding.

- Preventing infection. There is an increased risk of infection with bleeding, so you'll likely be given an antibiotic to prevent infection.

- Replacing the diseased liver with a healthy one. Liver transplant is an option for people with severe liver disease or those who experience recurrent bleeding of esophageal varices. Although liver transplantation is often successful, the number of people awaiting transplants far outnumbers the available organs.

Re-bleeding

There is a high risk that bleeding might recur in people who've had bleeding from esophageal varices. Beta blockers and endoscopic band ligation are the recommended treatments to help prevent re-bleeding.

After initial banding treatment, your provider typically repeats your upper endoscopy at regular intervals. If necessary, more banding may be done until the esophageal varices are gone or are small enough to reduce the risk of further bleeding.

Potential future treatment

Researchers are exploring an experimental emergency therapy to stop bleeding from esophageal varices that involves spraying an adhesive powder. The hemostatic powder is given through a catheter during an endoscopy. When sprayed on the esophagus, hemostatic powder sticks to the varices and may stop bleeding.

Another potential way to stop bleeding when all other measures fail is to use self-expanding metal stents (SEMS). SEMS can be placed during an endoscopy and stop bleeding by placing pressure on the bleeding esophageal varices.

However, SEMS could damage tissue and can migrate after being placed. The stent is typically removed within seven days and bleeding could recur. This option is experimental and isn't yet widely available.

- Blood transfusion

- Liver transplant

Preparing for your appointment

You might start by seeing your primary health care provider. Or you may be referred immediately to a provider who specializes in digestive disorders, called a gastroenterologist. If you're having symptoms of internal bleeding, call 911 or your local emergency number to be taken to the hospital for urgent care.

Here's some information to help you get ready for an appointment.

What you can do

When you make the appointment, ask if there's anything you need to do in advance, such as fasting before a specific test. Make a list of:

- Your symptoms, including any that seem unrelated to the reason for your appointment.

- Key personal information, including major stresses, recent life changes or recent travels, family and personal medical history, and your alcohol use.

- All medications, vitamins or other supplements you take, including doses.

- Questions to ask your doctor.

Take a family member or friend along, if possible, to help you remember information you're given.

For esophageal varices, questions to ask include:

- What's likely causing my symptoms?

- What other possible causes are there?

- What tests do I need?

- What's the best course of action?

- What are the side effects of the treatments?

- Are my symptoms likely to recur, and what can I do to prevent that?

- I have other health conditions. How can I best manage them together?

- Are there restrictions that I need to follow?

- Should I see a specialist?

- Are there brochures or other printed materials I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your provider is likely to ask you questions, such as:

- When did your symptoms begin?

- Have your symptoms stayed the same or gotten worse?

- How severe are your symptoms?

- Have you had signs of bleeding, such as blood in your stools or vomit?

- Have you had hepatitis or yellowing of your eyes or skin (jaundice)?

- Have you traveled recently? Where?

- If you drink alcohol, when did you start and how much do you drink?

What you can do in the meantime

If you develop bloody vomit or stools while you're waiting for your appointment, call 911 or your local emergency number or go to an emergency room immediately.

- Sanyal AJ. Overview of the management of patients with variceal bleeding. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Jan. 11, 2023.

- Varices. Merck Manual Professional Version. https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gastrointestinal-disorders/gastrointestinal-bleeding/varices/?autoredirectid=1083. Accessed Jan. 11, 2023.

- Ferri FF. Esophageal varices. In: Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2023. Elsevier; 2023. https://www.clinicalkey.com. Accessed Jan. 17, 2023.

- Rockey DC. Causes of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in adults. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Jan. 11, 2023.

- Sanyal AJ, et al. Prediction of variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Jan. 11, 2023.

- 13 ways to a healthy liver. American Liver Foundation. https://liverfoundation.org/resource-center/blog/13-ways-to-a-healthy-liver/. Accessed Jan. 17, 2023.

- AskMayoExpert. Esophageal and gastric varices. Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Zuckerman MJ, et al. Endoscopic treatment of esophageal varices. Clinical Liver Disease. 2022; doi:10.1016/j.cld.2021.08.003.

Associated Procedures

Products & services.

- A Book: Mayo Clinic on Digestive Health

- Symptoms & causes

- Diagnosis & treatment

- Doctors & departments

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

- About Journal

Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research

2349-2996 (Online) 2231-1149 (Print)

Nursing Care in Esophageal Varices

Author(s): Ajaya Ghosh Ru , Athuldev T , Sarika M L

Email(s): [email protected] , [email protected] , [email protected]

Address: Ajaya Ghosh Ru1, Athuldev T2, Sarika M L3 1Nursing Officer, Dept of Nursing, AIIMS Bhubaneswar, Bhubaneswar, Odisha 2Lecturer, Dept of Medical Surgical Nursing, MIMS College of Nursing, Calicut, Kerala 3Medical Surgical Nursing, JIPMER College of Nursing, Puducherry *Corresponding Author

Published In: Volume - 9 , Issue - 2 , Year - 2019

ABSTRACT: Objectives To identify and understand Nursing care in patients with esophageal varices.; Methods to adopt while managing acute variceal bleeding.; Nurses role in prevention of secondary bleeding. Design: used for this article is to review method. Data sources are different types of Medical and Gastroenterology text books, Medical Journals and Medical Surgical Nursing Text Books. The results that can be found; esophageal varices and paraesophageal varices are swollen veins in the lining of the lower esophagus. In most of the cases esophageal varices occur in people who have portal hypertension with variety of etiology. The veins don't enlarge in a uniform fashion. Esophageal varices usually have enlarged, irregularly shaped bulbous regions (varicosities) that are interrupted by narrower regions. These abnormal dilated veins rupture easily and can bleed profusely because, The pressure inside the varices is higher than the pressure inside normal veins; The walls of the varices are thin. About 50% of people who have bleeding from esophageal varices will have the problem return during the first one to two years. It is very much common among severe liver disease and ongoing alcohol consumption. Screening is done by an Upper GI Endoscopy.The preventive method used in patients is to give beta blockers. Bleeding from esophageal varices is an emergency that requires immediate treatment which includes variceal ligation and trans-jugular intra hepatic portosystemic shunt. Vasopressin and somatostatin analogue are main two drugs used to treat active bleeding. Conclusion: this article deals with management of esophageal varices which include both medical and nursing management. With effective and prompt nursing care for varices, the life of patients can be extended.

- Esophageal varices

- variceal ligation and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)

Cite this article: Ajaya Ghosh Ru, Athuldev T, Sarika M L. Nursing Care in Esophageal Varices. Asian J. Nursing Education and Research. 2019; 9(2):273-277. doi: 10.5958/2349-2996.2019.00059.4 Cite(Electronic): Ajaya Ghosh Ru, Athuldev T, Sarika M L. Nursing Care in Esophageal Varices. Asian J. Nursing Education and Research. 2019; 9(2):273-277. doi: 10.5958/2349-2996.2019.00059.4 Available on: https://ajner.com/AbstractView.aspx?PID=2019-9-2-27

Recomonded Articles:

Asian Journal of Nursing Education and Research (AJNER) is an international, peer-reviewed journal devoted to nursing sciences....... Read more >>>

Quick Links

- Submit Article

- Author's Guidelines

- Paper Template

- Copyright Form

- Cert. of Conflict of Intrest

- Processing Charges

- Indexing Information

Latest Issues

Popular articles, recent articles.

- Background/Objectives:

- technologically

- Nursing"[Mesh])

- "Australia"[Mesh]

- Undergraduate

- SARS-CoV-2.

- Cross-sectional

- Stress Resilience

- Nursing students.

- national-level

- facility-based

- cross-sectional

- Multicollinearity

- Neonatal Mortality

- administration

- schoolchildren

- television/mass

- First aid and safety measures

- school children

- computer assisted Teaching.

- undergraduates

- Research anxiety

- Research methods

- Research usefulness.

- considerations

- transformative

- administrative

- Artificial intelligence

- Clinical Decision Support Systems

- Natural Language Processing

- Workflow Optimization and Resource Management.

- under-nutrition

- non-experimental

- non-probability

- Malnutrition

- School going children.

- pre-experimental

- identification

- Effective Planned Teaching Programme

- Breast Cancer

- Prevention.

- End of life care

- Attitude. Frommelt Attitude Towards Care of Dying (FATCOD).

- evidence-based

- socio-economic

- Pediatric Obesity

- Childhood Obesity

- Nursing Strategies

- Pediatric Wellness.

- Pre-experimental

- Effectiveness of Structured Teaching Program

- Organ Donation

- transportation

- Nurse Practitioner

- Role of Nurse.

- physical/biological

- responsibility

- Premenstrual Syndrome

- Nursing officers

- Coping measures

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder

- PMS and work performance

- PMS and relationship with patients/co-workers.

- differentiation

- Care giver satisfaction

- Nursing care services

- Care givers.

- self-administered

- confidentiality

- hospitalization

- Individuals

- Prevention strategies.

- Cardiovascular

- disease-causing

- cardiovascular

- community-based

- cardio-vascular

- socio-demographic

- Younger Adults

- Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram

- District Early Intervention Centre

- Menstrual Cup

- Nursing Students.

- revolutionized

- AI based technology

- Nursing Education

- Nursing Practice.

Esophageal Varices Nursing Management

- Bleeding esophageal varices are hemorrhagic processes involving dialted, tortuous veins in the submucosa of the lower esophagus. .

Risk Factors

- Portal hypertension resulting from obstructed portal venous circulation

Pathophysiology

- In portal hypertension, collateral circulation develops in the lower esophagus as venous blood, which is diverted from the GI tract and spleen because of portal obstruction, seeks an outlet.

- Because of excessive intraluminal pressure, these collateral veins become tortuous, dilated, and fragile. They are particularly prone to ulceration and hemorrhage. Rupture of esophageal varices is the most common cause of death of clients with hepatic cirrhosis.

image by : hepatitisc.uw.edu

Assessment/Clinical Manifestations/Signs And Symptoms

- Hematemesis and melena, if ulcerated massive hemorrhage occurs

- Signs of hepatic encephalopathy

- Dilated abdominal veins

Laboratory and diagnostic study findings

- Endoscopy identifies the cause and site of bleeding

- Ultrasound and computed tomography assist in identifying the site of bleeding

Medical Management

Non-surgical treatment is preferred because of the high mortality associated with emergency surgery to control bleeding from esophageal varices and because of the poor physical condition of most of these patients.

Nonsurgical measures include:

- Pharmacologic therapy: somatostatin, vasopressin, beta-blocker and nitrates

- Balloon tamponade, saline lavage, endoscopic sclerotherapy

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunting (TIPS)

- Esophageal banding therapy, variceal band ligation

If necessary, surgery may involve:

- Bypass procedures (e.g. portacaval shunts, splenorenal shunt, mesocaval shunt)

- Devascularization and transaction

Aggressive medical care includes evaluation of extent of bleeding and continuous monitoring of vital signs when hematemesis and melena are present.

Signs of potential hypovolemia are noted; blood volume is monitored with a central venous pressure or arterial catheter.

Oxygen is administered to prevent hypoxia and maintain adequate blood oxygenation, and intravenous fluids and volume expanders are administered to restore fluid volume and replace electrolytes.

Need for blood transfusion is assessed, and intake and output (insert indwelling catheter) are monitored.

Nursing Diagnosis

- Risk for bleeding

- Imbalanced nutrition: less than body requirements

Nursing Management

Provide ongoing assessment.

- Assess for ecchymosis, epistaxis, petechiae, and bleeding gums

- Monitor level of consciousness, vital signs, and urinary output to evaluate fluid balance.

- Monitor the client during blood transfusion administration if prescribed.

Institute measure to address bleeding.

- Use small-gauge needles, and apply pressure or cold for bleeding.

Provide nursing care for the client undergoing a prescribed balloon tamponade to control bleeding.

- Explain the procedure to the client to reduce fear and enhance cooperation with insertion and maintenance of the esophageal tamponade tube.

- Monitor the client closely to prevent accidental removal or displacement of the tube with resultant airway obstruction.

Provide nursing intervention for the client undergoing a prescribed iced saline lavage.

- Ensure nasogastric tube patency to prevent aspiration

- Observe gastric aspirate for evidence of bleeding.

- Protect the client from chilling.

After injection sclerotherapy, assess for:

- Esophageal perforation

- Continued bleeding

After portal-systemic surgical intervention, monitor for complications.

- Development of systemic encephalopathy

- Liver failure

Administer prescribed medications, which may include vasopressin and vitamin K.

Related posts, endocarditis nursing management, magnetic resonance imaging, bone marrow aspiration and biopsy.

Hepatic Cirrhosis

- Hepatic cirrhosis is a chronic hepatic disease characterized by diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells.

Table of Contents

- What is Hepatic Cirrhosis?

Classification

Pathophysiology, statistics and incidences, clinical manifestations, complications, assessment and diagnostic findings, pharmacologic therapy, surgical management, nursing assessment, nursing diagnosis, nursing care planning & goals, nursing interventions, discharge and home care guidelines, documentation guidelines, what is hepatic cirrhosis.

The end-stage of liver disease is called cirrhosis.

- As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, this disease alters liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency.

- The prognosis is better in noncirrhotic forms of hepatic fibrosis, which cause minimal hepatic dysfunction and don’t destroy liver cells.

These clinical types of cirrhosis reflect its diverse etiology:

- Laennec’s cirrhosis. The most common type, this occurs in 30% to 50% of cirrhotic patients, up to 90% of whom have a history of alcoholism.

- Biliary cirrhosis. Biliary cirrhosis results in injury or prolonged obstruction.

- Postnecrotic cirrhosis. Postnecrotic cirrhosis stems from various types of hepatitis .

- Pigment cirrhosis. Pigment cirrhosis may result from disorders such as hemochromatosis.

- Cardiac cirrhosis. Cardiac cirrhosis refers to cirrhosis caused by right-sided heart failure .

- Idiopathic cirrhosis. Idiopathic cirrhosis has no known cause.

Although several factors have been implicated in the etiology of cirrhosis, alcohol consumption is considered the major causative factor.

- Necrosis. Cirrhosis is characterized by episodes of necrosis involving the liver cells.

- Scar tissue. The destroyed liver cells are gradually replaced with a scar tissue.

- Fibrosis. There is diffuse destruction and fibrotic regeneration of hepatic cells.

- Alteration. As necrotic tissue yields to fibrosis, the disease alters the liver structure and normal vasculature, impairs blood and lymph flow, and ultimately causes hepatic insufficiency.

Various types of cirrhosis may occur in different types of individuals.

- The most common, Laennec’s cirrhosis, occurs in 30% to 50% of cirrhotic patients.

- Biliary cirrhosis occurs in 15% to 20% of patients.

- Postnecrotic cirrhosis occurs in 10% to 30% of patients.

- Pigment cirrhosis occurs in 5% to 10% of patients.

- Idiopathic cirrhosis occurs in about 10% of patients.

Different types of cirrhosis have different causes.

- Excessive alcohol consumption. Too much alcohol intake is the most common cause of cirrhosis as liver damage is associated with chronic alcohol consumption.

- Injury. Injury or prolonged obstruction causes biliary cirrhosis.

- Hepatitis . The different types of hepatitis can cause postnecrotic cirrhosis.

- Other diseases. Diseases such as hemochromatosis causes pigment cirrhosis.

- Right-sided heart failure. Cardiac cirrhosis, a rare kind of cirrhosis, is caused by right-sided heart failure.

Clinical manifestations of the different types of cirrhosis are similar, regardless of the cause.

- GI system. Early indicators usually involve gastrointestinal signs and symptoms such as anorexia , indigestion, nausea , vomiting constipation , or diarrhea .

- Respiratory system . Respiratory symptoms occur late as a result of hepatic insufficiency and portal hypertension , such as pleural effusion and limited thoracic expansion due to abdominal ascites, interfering with efficient gas exchange leading to hypoxia.

- Central nervous system . Signs of hepatic encephalopathy also occur as a late sign, and these are lethargy , mental changes, slurred speech, asterixis (flapping tremor), peripheral neuritis, paranoia, hallucinations , extreme obtundation, and ultimately, coma.

- Hematologic. The patient experiences bleeding tendencies and anemia .

- Endocrine. The male patient experiences testicular atrophies, while the female patient may have menstrual irregularities, and gynecomastia and loss of chest and axillary hair .

- Skin. There is severe pruritus, extreme dryness, poor tissue turgor, abnormal pigmentation, spider angiomas, palmar erythema, and possibly jaundice .

- Hepatic. Cirrhosis causes jaundice, ascites, hepatomegaly, edema of the legs, hepatic encephalopathy, and hepatic renal syndrome.

The complications of hepatic cirrhosis include the following:

- Portal hypertension . Portal hypertension is the elevation of pressure in the portal vein that occurs when blood flow meets increased resistance.

- Esophageal varices. Esophageal varices are dilated tortuous veins in submucosa of the lower esophagus .

- Hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatic encephalopathy may manifest as deteriorating mental status and dementia or as physical signs such as abnormal involuntary and voluntary movements.

- Fluid volume excess . Fluid volume excess occurs due to an increased cardiac output and decreased peripheral vascular resistance.

Laboratory findings and imaging studies that are characteristic of cirrhosis include:

- Liver scan. Liver scan shows abnormal thickening and a liver mass.

- Liver biopsy . Liver biopsy is the definitive test for cirrhosis as it detects destruction and fibrosis of the hepatic tissue.

- Liver imaging. Computed tomography scan , ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging may confirm the diagnosis of cirrhosis through visualization of masses, abnormal growths, metastases, ans venous malformations.

- Cholecystography and cholangiography. These two visualize the gallbladder and the biliary duct system.

- Splenoportal venography. Splenoportal venography visualizes the portal venous system.

- Percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography. This test differentiates intrahepatic from extrahepatic obstructive jaundice and discloses hepatic pathology and the presence of gallstones .

- Complete blood count . There is decreased white blood cell count, hemoglobin level and hematocrit, albumin, or platelets .

Medical Management

Treatment is designed to remove or alleviate the underlying cause of cirrhosis.

- Diet . The patient may benefit from a high-calorie and a medium to high protein diet , as developing hepatic encephalopathy mandates restricted protein intake.

- Sodium restriction. is usually restricted to 2g/day .

- Fluid restriction. Fluids are restricted to 1 to 1.5 liters/day .

- Activity. Rest and moderate exercise is essential.

- Paracentesis. Paracentesis may help alleviate ascites.

- Sengstaken-Blakemore or Minnesota tube. The Sengstaken-Blakemore or Minnesota tube may also help control hemorrhage by applying pressure on the bleeding site.

Drug therapy requires special caution because the cirrhotic liver cannot detoxify harmful agents effectively.

- Octreotide . If required, octreotide may be prescribed for esophageal varices.

- Diuretics . Diuretics may be given for edema , however, they require careful monitoring because fluid and electrolyte imbalance may precipitate hepatic encephalopathy.

- Lactulose. Encephalopathy is treated with lactulose.

- Antibiotics . Antibiotics are used to decrease intestinal bacteria and reduce ammonia production, one of the causes of encephalopathy.

Surgical procedures for management of hepatic cirrhosis include:

- Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) procedure. The TIPS procedure is used for the treatment of varices by upper endoscopy with banding to relieve portal hypertension .

Nursing Management

Nursing management for the patient with cirrhosis of the liver should focus on promoting rest, improving nutritional status , providing skin care , reducing risk of injury , and monitoring and managing complications.

Assessment of the patient with cirrhosis should include assessing for:

- Bleeding. Check the patient’s skin, gums, stools, and vomitus for bleeding.

- Fluid retention. To assess for fluid retention, weigh the patient and measure abdominal girth at least once daily.

- Mentation. Assess the patient’s level of consciousness often and observe closely for changes in behavior or personality.

Based on the assessment data, the major nursing diagnosis for the patient are:

- Activity intolerance related to fatigue , lethargy , and malaise.

- Imbalanced nutrition : less than body requirements related to abdominal distention and discomfort and anorexia.

- Impaired skin integrity related to pruritus from jaundice and edema .

- High risk for injury related to altered clotting mechanisms and altered level of consciousness.

- Disturbed body image related to changes in appearance, sexual dysfunction , and role function.

- Chronic pain and discomfort related to enlarged liver and ascites.

- Fluid volume excess related ascites and edema formation.

- Disturbed thought processes and potential for mental deterioration related to abnormal liver function and increased serum ammonia level.

- Ineffective breathing pattern related to ascites and restriction of thoracic excursion secondary to ascites, abdominal distention, and fluid in the thoracic cavity.

Main Article: 8 Liver Cirrhosis Nursing Care Plans

The major goals for a patient with cirrhosis are:

- Report decrease in fatigue and increased ability to participate in activities.

- Maintain a positive nitrogen balance, no further loss of muscle mass, and meet nutritional requirements.

- Decrease potential for pressure ulcer development and breaks in skin integrity .

- Reduce the risk of injury.

- Verbalize feelings consistent with improvement of body image and self-esteem .

- Increase level of comfort .

- Restore normal fluid volume.

- Improve mental status, maintain safety, and ability to cope with cognitive and behavioral changes.

- Improve respiratory status.

The patient with cirrhosis needs close observation, first-class supportive care, and sound nutrition counseling.

Promoting Rest

- Position bed for maximal respiratory efficiency; provide oxygen if needed.

- Initiate efforts to prevent respiratory, circulatory, and vascular disturbances.

- Encourage patient to increase activity gradually and plan rest with activity and mild exercise.

Improving Nutritional Status

- Provide a nutritious, high-protein diet supplemented by B-complex vitamins and others, including A, C, and K.

- Encourage patient to eat: Provide small, frequent meals, consider patient preferences, and provide protein supplements, if indicated.

- Provide nutrients by feeding tube or total PN if needed.

- Provide patients who have fatty stools (steatorrhea) with water-soluble forms of fat-soluble vitamins A, D, and E, and give folic acid and iron to prevent anemia .

- Provide a low-protein diet temporarily if patient shows signs of impending or advancing coma; restrict sodium if needed.

Providing Skin Care

- Change patient’s position frequently.

- Avoid using irritating soaps and adhesive tape.

- Provide lotion to soothe irritated skin; take measures to prevent patient from scratching the skin.

Reducing Risk of Injury

- Use padded side rails if patient becomes agitated or restless.

- Orient to time, place, and procedures to minimize agitation.

- Instruct patient to ask for assistance to get out of bed.

- Carefully evaluate any injury because of the possibility of internal bleeding.

- Provide safety measures to prevent injury or cuts (electric razor, soft toothbrush).

- Apply pressure to venipuncture sites to minimize bleeding.

Monitoring and Managing Complications

- Monitor for bleeding and hemorrhage .

- Monitor the patient’s mental status closely and report changes so that treatment of encephalopathy can be initiated promptly.

- Carefully monitor serum electrolyte levels are and correct if abnormal.

- Administer oxygen if oxygen desaturation occurs; monitor for fever or abdominal pain , which may signal the onset of bacterial peritonitis or other infection .

- Assess cardiovascular and respiratory status; administer diuretics, implement fluid restrictions, and enhance patient positioning , if needed.

- Monitor intake and output , daily weight changes, changes in abdominal girth, and edema formation.

- Monitor for nocturia and, later, for oliguria, because these states indicate increasing severity of liver dysfunction.

Home Management

- Prepare for discharge by providing dietary instruction, including exclusion of alcohol.

- Refer to Alcoholics Anonymous , psychiatric care, counseling, or spiritual advisor if indicated.

- Continue sodium restriction; stress avoidance of raw shellfish.

- Provide written instructions, teaching, support, and reinforcement to patient and family.

- Encourage rest and probably a change in lifestyle (adequate,well-balanced diet and elimination of alcohol).

- Instruct family about symptoms of impending encephalopathy and possibility of bleeding tendencies and infection.

- Offer support and encouragement to the patient and provide positive feedback when the patient experiences successes.

- Refer patient to home care nurse , and assist in transition from hospital to home.

Expected patient outcomes include:

- Reported decrease in fatigue and increased ability to participate in activities.

- Maintained a positive nitrogen balance, no further loss of muscle mass, and meet nutritional requirements.

- Decreased potential for pressure ulcer development and breaks in skin integrity .

- Reduced the risk of injury.

- Verbalized feelings consistent with improvement of body image and self-esteem .

- Increased level of comfort .

- Restored normal fluid volume.

- Improved mental status, maintain safety, and ability to cope with cognitive and behavioral changes.

- Improved respiratory status.

The focus of discharge education is dietary instructions.

- Alcohol restriction. Of greatest importance is the exclusion of alcohol from the diet, so the patient may need referral to Alcoholics Anonymous, psychiatric care, or counseling.

- Sodium restriction. Sodium restriction will continue for considerable time, if not permanently.

- Complication education. The nurse also instructs the patient and family about symptoms of impending encephalopathy, possible bleeding tendencies, and susceptibility to infection.

The focus of documentation may include:

- Level of activity.

- Causative or precipitating factors.

- Vital signs before, during, and following activity.

- Plan of care.

- Response to interventions, teaching, and actions performed.

- Teaching plan.

- Changes to plan of care.

- Attainment or progress toward desired outcome.

- Caloric intake.

- Individual cultural or religious restrictions, personal preferences.

- Availability and use of resources.

- Duration of the problem.

- Perceptio of pain , effects on lifestyle, and expectations of therapeutic regimen .

- Results of laboratory tests, diagnostic studies, and mental status and cognitive evaluation .

Other posts from the site you may like:

- 8 Liver Cirrhosis Nursing Care Plans

- 7 Hepatitis Nursing Care Plans

- Bile Duct Stones (Choledocholithiasis)

1 thought on “Hepatic Cirrhosis”

Good effective management of cirrhosis that will help nurse student to manage patients: well done health team🙏

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Let’s check in on Mr. Abrams

By now Mrs. Abrams has arrived and is able to provide information about the patient’s home medications, which she has brought with her. You inspect the pill bottles and note Mr. Abrams takes metoprolol, hydralazine, levothyroxine, metformin, furosemide, naproxen, and atorvastatin.

Why does he take metoprolol?

Hypertension

Why does he take hydralazine?

Why does he take levothyroxine?

Hypothyroidism

Why does he take metformin?

Type 2 diabetes

Why does he take furosemide?

To reduce edema and ascites associated with chronic liver disease

Now that we know he takes furosemide, what labs will we double check?

Creatinine and potassium…remember, furosemide is a loop diuretic that causes potassium losses! It also can cause creatinine to increase.

Why does he take naproxen?

Osteoarthritis

Why does he take atorvastatin?

Hyperlipidemia

Which medication is a red flag?

The naproxen is a red flag because of its association with GI bleeding. Not only can it cause peptic ulcers to form and bleed, studies show it can also contribute to the bleeding of esophageal varices. Since esophageal varices develop in patients with liver disease due to portal hypertension, and Mr. Abrams has low platelets and an elevated prothrombin time, we are very concerned about his use of this medication.

What do we want to ask his wife about in regards to this medication?

We want to ask his wife how much naproxen he takes. She tells you he takes it multiple times daily, so now we are now really, really, really concerned!

Physical assessment

You perform a full head-to-toe assessment on Mr. Abrams. Significant findings reveal that he is lethargic, and disoriented to time and situation. You reorient the patient, but repeat assessment shows continued confusion. Heart sounds are normal, pulse is weak and fast in the mid 120’s, capillary refill is 3 seconds. Pt is tachypneic, complaining of shortness of breath, and speaking in three to four word sentences. Accessory muscle use is present and lung sounds are normal. Abdomen is moderately distended, with caput medusae present. Pt shows 2+ edema in bilateral lower extremities. Skin signs reveal jaundice and pallor.

Why is Mr. Abrams lethargic?

Anemia secondary to GI bleed.

Why is Mr. Abrams disoriented?

One reason for confusion or disorientation is that he lost consciousness at home and woke up in the ambulance. This would be disorienting to anyone! However, hypoxia causes confusion, which is definitely a concern for this patient.

Why is his pulse weak?

Low circulating blood volume reduces preload, which reduces cardiac stretch. Reduced cardiac stretch leads to reduced cardiac output and a weak pulse.

Are we concerned about his capillary refill?

This is right at the edge of delayed capillary refill. Any further blood loss is going to affect this even more, so yes, we are concerned.

Why is the patient tachypneic, short of breath, and using accessory muscles?

Low hemoglobin means less oxygen is being delivered to the tissues, so Mr. Abrams is hypoxic. As a compensatory mechanism, his respiratory rate and work of breathing has increased. This also causes him to feel shortness of breath.

Why is Mr. Abrams’ abdomen distended?

Patients with chronic liver disease have increased portal hypertension and low circulating plasma proteins, so fluid is easily lost into the abdomen due to third-spacing (a condition called ascites). Increased vascular pressure can also cause an enlarged spleen, and the liver is likely enlarged as well. Both of these enlarged organs can contribute to abdominal enlargement. Note that when ascites is significant, it also causes shortness of breath, so we want to watch Mr. Abrams closely for increased abdominal distention and associated respiratory compromise.

What is caput medusae?

Caput medusae is associated with portal hypertension and is due to the shunting of blood through umbilical veins, which become engorged and visible on the surface.

Why does the patient have 2+ pitting edema in the BLE?

Mr. Abrams has low serum albumin and therefore, low circulating plasma proteins. This means oncotic pressure is decreased and fluid is able to leak into the interstitial space (third-spacing).

How do we assess for jaundice in Mr. Abrams and what does it indicate?

In individuals with dark or yellow-toned skin, the best place to observe for jaundice is the sclera. Note that if a patient with darker skin has callouses on the palms or soles of their feet, these can appear yellow without jaundice being present. You can also observe for a yellow discoloration of the oral mucosa by looking at the hard palate. Jaundice indicates there is a buildup of bilirubin in the blood.

How do we assess for pallor in Mr. Abrams?

Assessing for pallor in individuals with darker skin tones can be difficult. The mucus membranes of very dark skinned individuals tend to appear ashen or gray while the color is more yellowish-brown in those with brown skin tones. You can also observe the palmar surface which may appear paler than usual. Note that fluorescent lighting can give the skin a bluish tint, so use a halogen lamp or natural light.

Now, back to Mr. Abrams