- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Empirical Research: Definition, Methods, Types and Examples

Content Index

Empirical research: Definition

Empirical research: origin, quantitative research methods, qualitative research methods, steps for conducting empirical research, empirical research methodology cycle, advantages of empirical research, disadvantages of empirical research, why is there a need for empirical research.

Empirical research is defined as any research where conclusions of the study is strictly drawn from concretely empirical evidence, and therefore “verifiable” evidence.

This empirical evidence can be gathered using quantitative market research and qualitative market research methods.

For example: A research is being conducted to find out if listening to happy music in the workplace while working may promote creativity? An experiment is conducted by using a music website survey on a set of audience who are exposed to happy music and another set who are not listening to music at all, and the subjects are then observed. The results derived from such a research will give empirical evidence if it does promote creativity or not.

LEARN ABOUT: Behavioral Research

You must have heard the quote” I will not believe it unless I see it”. This came from the ancient empiricists, a fundamental understanding that powered the emergence of medieval science during the renaissance period and laid the foundation of modern science, as we know it today. The word itself has its roots in greek. It is derived from the greek word empeirikos which means “experienced”.

In today’s world, the word empirical refers to collection of data using evidence that is collected through observation or experience or by using calibrated scientific instruments. All of the above origins have one thing in common which is dependence of observation and experiments to collect data and test them to come up with conclusions.

LEARN ABOUT: Causal Research

Types and methodologies of empirical research

Empirical research can be conducted and analysed using qualitative or quantitative methods.

- Quantitative research : Quantitative research methods are used to gather information through numerical data. It is used to quantify opinions, behaviors or other defined variables . These are predetermined and are in a more structured format. Some of the commonly used methods are survey, longitudinal studies, polls, etc

- Qualitative research: Qualitative research methods are used to gather non numerical data. It is used to find meanings, opinions, or the underlying reasons from its subjects. These methods are unstructured or semi structured. The sample size for such a research is usually small and it is a conversational type of method to provide more insight or in-depth information about the problem Some of the most popular forms of methods are focus groups, experiments, interviews, etc.

Data collected from these will need to be analysed. Empirical evidence can also be analysed either quantitatively and qualitatively. Using this, the researcher can answer empirical questions which have to be clearly defined and answerable with the findings he has got. The type of research design used will vary depending on the field in which it is going to be used. Many of them might choose to do a collective research involving quantitative and qualitative method to better answer questions which cannot be studied in a laboratory setting.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Research Questions and Questionnaires

Quantitative research methods aid in analyzing the empirical evidence gathered. By using these a researcher can find out if his hypothesis is supported or not.

- Survey research: Survey research generally involves a large audience to collect a large amount of data. This is a quantitative method having a predetermined set of closed questions which are pretty easy to answer. Because of the simplicity of such a method, high responses are achieved. It is one of the most commonly used methods for all kinds of research in today’s world.

Previously, surveys were taken face to face only with maybe a recorder. However, with advancement in technology and for ease, new mediums such as emails , or social media have emerged.

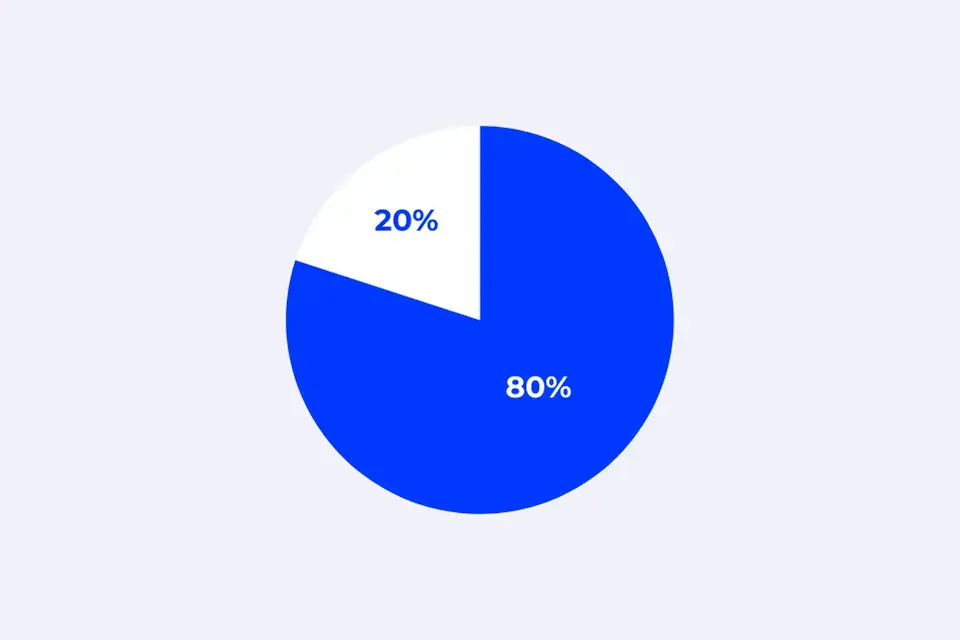

For example: Depletion of energy resources is a growing concern and hence there is a need for awareness about renewable energy. According to recent studies, fossil fuels still account for around 80% of energy consumption in the United States. Even though there is a rise in the use of green energy every year, there are certain parameters because of which the general population is still not opting for green energy. In order to understand why, a survey can be conducted to gather opinions of the general population about green energy and the factors that influence their choice of switching to renewable energy. Such a survey can help institutions or governing bodies to promote appropriate awareness and incentive schemes to push the use of greener energy.

Learn more: Renewable Energy Survey Template Descriptive Research vs Correlational Research

- Experimental research: In experimental research , an experiment is set up and a hypothesis is tested by creating a situation in which one of the variable is manipulated. This is also used to check cause and effect. It is tested to see what happens to the independent variable if the other one is removed or altered. The process for such a method is usually proposing a hypothesis, experimenting on it, analyzing the findings and reporting the findings to understand if it supports the theory or not.

For example: A particular product company is trying to find what is the reason for them to not be able to capture the market. So the organisation makes changes in each one of the processes like manufacturing, marketing, sales and operations. Through the experiment they understand that sales training directly impacts the market coverage for their product. If the person is trained well, then the product will have better coverage.

- Correlational research: Correlational research is used to find relation between two set of variables . Regression analysis is generally used to predict outcomes of such a method. It can be positive, negative or neutral correlation.

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

For example: Higher educated individuals will get higher paying jobs. This means higher education enables the individual to high paying job and less education will lead to lower paying jobs.

- Longitudinal study: Longitudinal study is used to understand the traits or behavior of a subject under observation after repeatedly testing the subject over a period of time. Data collected from such a method can be qualitative or quantitative in nature.

For example: A research to find out benefits of exercise. The target is asked to exercise everyday for a particular period of time and the results show higher endurance, stamina, and muscle growth. This supports the fact that exercise benefits an individual body.

- Cross sectional: Cross sectional study is an observational type of method, in which a set of audience is observed at a given point in time. In this type, the set of people are chosen in a fashion which depicts similarity in all the variables except the one which is being researched. This type does not enable the researcher to establish a cause and effect relationship as it is not observed for a continuous time period. It is majorly used by healthcare sector or the retail industry.

For example: A medical study to find the prevalence of under-nutrition disorders in kids of a given population. This will involve looking at a wide range of parameters like age, ethnicity, location, incomes and social backgrounds. If a significant number of kids coming from poor families show under-nutrition disorders, the researcher can further investigate into it. Usually a cross sectional study is followed by a longitudinal study to find out the exact reason.

- Causal-Comparative research : This method is based on comparison. It is mainly used to find out cause-effect relationship between two variables or even multiple variables.

For example: A researcher measured the productivity of employees in a company which gave breaks to the employees during work and compared that to the employees of the company which did not give breaks at all.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

Some research questions need to be analysed qualitatively, as quantitative methods are not applicable there. In many cases, in-depth information is needed or a researcher may need to observe a target audience behavior, hence the results needed are in a descriptive analysis form. Qualitative research results will be descriptive rather than predictive. It enables the researcher to build or support theories for future potential quantitative research. In such a situation qualitative research methods are used to derive a conclusion to support the theory or hypothesis being studied.

LEARN ABOUT: Qualitative Interview

- Case study: Case study method is used to find more information through carefully analyzing existing cases. It is very often used for business research or to gather empirical evidence for investigation purpose. It is a method to investigate a problem within its real life context through existing cases. The researcher has to carefully analyse making sure the parameter and variables in the existing case are the same as to the case that is being investigated. Using the findings from the case study, conclusions can be drawn regarding the topic that is being studied.

For example: A report mentioning the solution provided by a company to its client. The challenges they faced during initiation and deployment, the findings of the case and solutions they offered for the problems. Such case studies are used by most companies as it forms an empirical evidence for the company to promote in order to get more business.

- Observational method: Observational method is a process to observe and gather data from its target. Since it is a qualitative method it is time consuming and very personal. It can be said that observational research method is a part of ethnographic research which is also used to gather empirical evidence. This is usually a qualitative form of research, however in some cases it can be quantitative as well depending on what is being studied.

For example: setting up a research to observe a particular animal in the rain-forests of amazon. Such a research usually take a lot of time as observation has to be done for a set amount of time to study patterns or behavior of the subject. Another example used widely nowadays is to observe people shopping in a mall to figure out buying behavior of consumers.

- One-on-one interview: Such a method is purely qualitative and one of the most widely used. The reason being it enables a researcher get precise meaningful data if the right questions are asked. It is a conversational method where in-depth data can be gathered depending on where the conversation leads.

For example: A one-on-one interview with the finance minister to gather data on financial policies of the country and its implications on the public.

- Focus groups: Focus groups are used when a researcher wants to find answers to why, what and how questions. A small group is generally chosen for such a method and it is not necessary to interact with the group in person. A moderator is generally needed in case the group is being addressed in person. This is widely used by product companies to collect data about their brands and the product.

For example: A mobile phone manufacturer wanting to have a feedback on the dimensions of one of their models which is yet to be launched. Such studies help the company meet the demand of the customer and position their model appropriately in the market.

- Text analysis: Text analysis method is a little new compared to the other types. Such a method is used to analyse social life by going through images or words used by the individual. In today’s world, with social media playing a major part of everyone’s life, such a method enables the research to follow the pattern that relates to his study.

For example: A lot of companies ask for feedback from the customer in detail mentioning how satisfied are they with their customer support team. Such data enables the researcher to take appropriate decisions to make their support team better.

Sometimes a combination of the methods is also needed for some questions that cannot be answered using only one type of method especially when a researcher needs to gain a complete understanding of complex subject matter.

We recently published a blog that talks about examples of qualitative data in education ; why don’t you check it out for more ideas?

Since empirical research is based on observation and capturing experiences, it is important to plan the steps to conduct the experiment and how to analyse it. This will enable the researcher to resolve problems or obstacles which can occur during the experiment.

Step #1: Define the purpose of the research

This is the step where the researcher has to answer questions like what exactly do I want to find out? What is the problem statement? Are there any issues in terms of the availability of knowledge, data, time or resources. Will this research be more beneficial than what it will cost.

Before going ahead, a researcher has to clearly define his purpose for the research and set up a plan to carry out further tasks.

Step #2 : Supporting theories and relevant literature

The researcher needs to find out if there are theories which can be linked to his research problem . He has to figure out if any theory can help him support his findings. All kind of relevant literature will help the researcher to find if there are others who have researched this before, or what are the problems faced during this research. The researcher will also have to set up assumptions and also find out if there is any history regarding his research problem

Step #3: Creation of Hypothesis and measurement

Before beginning the actual research he needs to provide himself a working hypothesis or guess what will be the probable result. Researcher has to set up variables, decide the environment for the research and find out how can he relate between the variables.

Researcher will also need to define the units of measurements, tolerable degree for errors, and find out if the measurement chosen will be acceptable by others.

Step #4: Methodology, research design and data collection

In this step, the researcher has to define a strategy for conducting his research. He has to set up experiments to collect data which will enable him to propose the hypothesis. The researcher will decide whether he will need experimental or non experimental method for conducting the research. The type of research design will vary depending on the field in which the research is being conducted. Last but not the least, the researcher will have to find out parameters that will affect the validity of the research design. Data collection will need to be done by choosing appropriate samples depending on the research question. To carry out the research, he can use one of the many sampling techniques. Once data collection is complete, researcher will have empirical data which needs to be analysed.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

Step #5: Data Analysis and result

Data analysis can be done in two ways, qualitatively and quantitatively. Researcher will need to find out what qualitative method or quantitative method will be needed or will he need a combination of both. Depending on the unit of analysis of his data, he will know if his hypothesis is supported or rejected. Analyzing this data is the most important part to support his hypothesis.

Step #6: Conclusion

A report will need to be made with the findings of the research. The researcher can give the theories and literature that support his research. He can make suggestions or recommendations for further research on his topic.

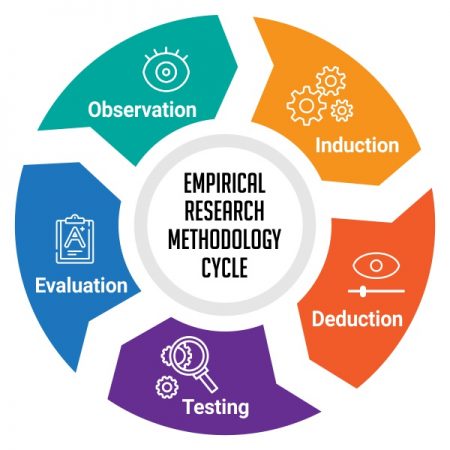

A.D. de Groot, a famous dutch psychologist and a chess expert conducted some of the most notable experiments using chess in the 1940’s. During his study, he came up with a cycle which is consistent and now widely used to conduct empirical research. It consists of 5 phases with each phase being as important as the next one. The empirical cycle captures the process of coming up with hypothesis about how certain subjects work or behave and then testing these hypothesis against empirical data in a systematic and rigorous approach. It can be said that it characterizes the deductive approach to science. Following is the empirical cycle.

- Observation: At this phase an idea is sparked for proposing a hypothesis. During this phase empirical data is gathered using observation. For example: a particular species of flower bloom in a different color only during a specific season.

- Induction: Inductive reasoning is then carried out to form a general conclusion from the data gathered through observation. For example: As stated above it is observed that the species of flower blooms in a different color during a specific season. A researcher may ask a question “does the temperature in the season cause the color change in the flower?” He can assume that is the case, however it is a mere conjecture and hence an experiment needs to be set up to support this hypothesis. So he tags a few set of flowers kept at a different temperature and observes if they still change the color?

- Deduction: This phase helps the researcher to deduce a conclusion out of his experiment. This has to be based on logic and rationality to come up with specific unbiased results.For example: In the experiment, if the tagged flowers in a different temperature environment do not change the color then it can be concluded that temperature plays a role in changing the color of the bloom.

- Testing: This phase involves the researcher to return to empirical methods to put his hypothesis to the test. The researcher now needs to make sense of his data and hence needs to use statistical analysis plans to determine the temperature and bloom color relationship. If the researcher finds out that most flowers bloom a different color when exposed to the certain temperature and the others do not when the temperature is different, he has found support to his hypothesis. Please note this not proof but just a support to his hypothesis.

- Evaluation: This phase is generally forgotten by most but is an important one to keep gaining knowledge. During this phase the researcher puts forth the data he has collected, the support argument and his conclusion. The researcher also states the limitations for the experiment and his hypothesis and suggests tips for others to pick it up and continue a more in-depth research for others in the future. LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

LEARN MORE: Population vs Sample

There is a reason why empirical research is one of the most widely used method. There are a few advantages associated with it. Following are a few of them.

- It is used to authenticate traditional research through various experiments and observations.

- This research methodology makes the research being conducted more competent and authentic.

- It enables a researcher understand the dynamic changes that can happen and change his strategy accordingly.

- The level of control in such a research is high so the researcher can control multiple variables.

- It plays a vital role in increasing internal validity .

Even though empirical research makes the research more competent and authentic, it does have a few disadvantages. Following are a few of them.

- Such a research needs patience as it can be very time consuming. The researcher has to collect data from multiple sources and the parameters involved are quite a few, which will lead to a time consuming research.

- Most of the time, a researcher will need to conduct research at different locations or in different environments, this can lead to an expensive affair.

- There are a few rules in which experiments can be performed and hence permissions are needed. Many a times, it is very difficult to get certain permissions to carry out different methods of this research.

- Collection of data can be a problem sometimes, as it has to be collected from a variety of sources through different methods.

LEARN ABOUT: Social Communication Questionnaire

Empirical research is important in today’s world because most people believe in something only that they can see, hear or experience. It is used to validate multiple hypothesis and increase human knowledge and continue doing it to keep advancing in various fields.

For example: Pharmaceutical companies use empirical research to try out a specific drug on controlled groups or random groups to study the effect and cause. This way, they prove certain theories they had proposed for the specific drug. Such research is very important as sometimes it can lead to finding a cure for a disease that has existed for many years. It is useful in science and many other fields like history, social sciences, business, etc.

LEARN ABOUT: 12 Best Tools for Researchers

With the advancement in today’s world, empirical research has become critical and a norm in many fields to support their hypothesis and gain more knowledge. The methods mentioned above are very useful for carrying out such research. However, a number of new methods will keep coming up as the nature of new investigative questions keeps getting unique or changing.

Create a single source of real data with a built-for-insights platform. Store past data, add nuggets of insights, and import research data from various sources into a CRM for insights. Build on ever-growing research with a real-time dashboard in a unified research management platform to turn insights into knowledge.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Raked Weighting: A Key Tool for Accurate Survey Results

May 31, 2024

Top 8 Data Trends to Understand the Future of Data

May 30, 2024

Top 12 Interactive Presentation Software to Engage Your User

May 29, 2024

Trend Report: Guide for Market Dynamics & Strategic Analysis

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

What is Empirical Research? Definition, Methods, Examples

Appinio Research · 09.02.2024 · 36min read

Ever wondered how we gather the facts, unveil hidden truths, and make informed decisions in a world filled with questions? Empirical research holds the key.

In this guide, we'll delve deep into the art and science of empirical research, unraveling its methods, mysteries, and manifold applications. From defining the core principles to mastering data analysis and reporting findings, we're here to equip you with the knowledge and tools to navigate the empirical landscape.

What is Empirical Research?

Empirical research is the cornerstone of scientific inquiry, providing a systematic and structured approach to investigating the world around us. It is the process of gathering and analyzing empirical or observable data to test hypotheses, answer research questions, or gain insights into various phenomena. This form of research relies on evidence derived from direct observation or experimentation, allowing researchers to draw conclusions based on real-world data rather than purely theoretical or speculative reasoning.

Characteristics of Empirical Research

Empirical research is characterized by several key features:

- Observation and Measurement : It involves the systematic observation or measurement of variables, events, or behaviors.

- Data Collection : Researchers collect data through various methods, such as surveys, experiments, observations, or interviews.

- Testable Hypotheses : Empirical research often starts with testable hypotheses that are evaluated using collected data.

- Quantitative or Qualitative Data : Data can be quantitative (numerical) or qualitative (non-numerical), depending on the research design.

- Statistical Analysis : Quantitative data often undergo statistical analysis to determine patterns , relationships, or significance.

- Objectivity and Replicability : Empirical research strives for objectivity, minimizing researcher bias . It should be replicable, allowing other researchers to conduct the same study to verify results.

- Conclusions and Generalizations : Empirical research generates findings based on data and aims to make generalizations about larger populations or phenomena.

Importance of Empirical Research

Empirical research plays a pivotal role in advancing knowledge across various disciplines. Its importance extends to academia, industry, and society as a whole. Here are several reasons why empirical research is essential:

- Evidence-Based Knowledge : Empirical research provides a solid foundation of evidence-based knowledge. It enables us to test hypotheses, confirm or refute theories, and build a robust understanding of the world.

- Scientific Progress : In the scientific community, empirical research fuels progress by expanding the boundaries of existing knowledge. It contributes to the development of theories and the formulation of new research questions.

- Problem Solving : Empirical research is instrumental in addressing real-world problems and challenges. It offers insights and data-driven solutions to complex issues in fields like healthcare, economics, and environmental science.

- Informed Decision-Making : In policymaking, business, and healthcare, empirical research informs decision-makers by providing data-driven insights. It guides strategies, investments, and policies for optimal outcomes.

- Quality Assurance : Empirical research is essential for quality assurance and validation in various industries, including pharmaceuticals, manufacturing, and technology. It ensures that products and processes meet established standards.

- Continuous Improvement : Businesses and organizations use empirical research to evaluate performance, customer satisfaction, and product effectiveness. This data-driven approach fosters continuous improvement and innovation.

- Human Advancement : Empirical research in fields like medicine and psychology contributes to the betterment of human health and well-being. It leads to medical breakthroughs, improved therapies, and enhanced psychological interventions.

- Critical Thinking and Problem Solving : Engaging in empirical research fosters critical thinking skills, problem-solving abilities, and a deep appreciation for evidence-based decision-making.

Empirical research empowers us to explore, understand, and improve the world around us. It forms the bedrock of scientific inquiry and drives progress in countless domains, shaping our understanding of both the natural and social sciences.

How to Conduct Empirical Research?

So, you've decided to dive into the world of empirical research. Let's begin by exploring the crucial steps involved in getting started with your research project.

1. Select a Research Topic

Selecting the right research topic is the cornerstone of a successful empirical study. It's essential to choose a topic that not only piques your interest but also aligns with your research goals and objectives. Here's how to go about it:

- Identify Your Interests : Start by reflecting on your passions and interests. What topics fascinate you the most? Your enthusiasm will be your driving force throughout the research process.

- Brainstorm Ideas : Engage in brainstorming sessions to generate potential research topics. Consider the questions you've always wanted to answer or the issues that intrigue you.

- Relevance and Significance : Assess the relevance and significance of your chosen topic. Does it contribute to existing knowledge? Is it a pressing issue in your field of study or the broader community?

- Feasibility : Evaluate the feasibility of your research topic. Do you have access to the necessary resources, data, and participants (if applicable)?

2. Formulate Research Questions

Once you've narrowed down your research topic, the next step is to formulate clear and precise research questions . These questions will guide your entire research process and shape your study's direction. To create effective research questions:

- Specificity : Ensure that your research questions are specific and focused. Vague or overly broad questions can lead to inconclusive results.

- Relevance : Your research questions should directly relate to your chosen topic. They should address gaps in knowledge or contribute to solving a particular problem.

- Testability : Ensure that your questions are testable through empirical methods. You should be able to gather data and analyze it to answer these questions.

- Avoid Bias : Craft your questions in a way that avoids leading or biased language. Maintain neutrality to uphold the integrity of your research.

3. Review Existing Literature

Before you embark on your empirical research journey, it's essential to immerse yourself in the existing body of literature related to your chosen topic. This step, often referred to as a literature review, serves several purposes:

- Contextualization : Understand the historical context and current state of research in your field. What have previous studies found, and what questions remain unanswered?

- Identifying Gaps : Identify gaps or areas where existing research falls short. These gaps will help you formulate meaningful research questions and hypotheses.

- Theory Development : If your study is theoretical, consider how existing theories apply to your topic. If it's empirical, understand how previous studies have approached data collection and analysis.

- Methodological Insights : Learn from the methodologies employed in previous research. What methods were successful, and what challenges did researchers face?

4. Define Variables

Variables are fundamental components of empirical research. They are the factors or characteristics that can change or be manipulated during your study. Properly defining and categorizing variables is crucial for the clarity and validity of your research. Here's what you need to know:

- Independent Variables : These are the variables that you, as the researcher, manipulate or control. They are the "cause" in cause-and-effect relationships.

- Dependent Variables : Dependent variables are the outcomes or responses that you measure or observe. They are the "effect" influenced by changes in independent variables.

- Operational Definitions : To ensure consistency and clarity, provide operational definitions for your variables. Specify how you will measure or manipulate each variable.

- Control Variables : In some studies, controlling for other variables that may influence your dependent variable is essential. These are known as control variables.

Understanding these foundational aspects of empirical research will set a solid foundation for the rest of your journey. Now that you've grasped the essentials of getting started, let's delve deeper into the intricacies of research design.

Empirical Research Design

Now that you've selected your research topic, formulated research questions, and defined your variables, it's time to delve into the heart of your empirical research journey – research design . This pivotal step determines how you will collect data and what methods you'll employ to answer your research questions. Let's explore the various facets of research design in detail.

Types of Empirical Research

Empirical research can take on several forms, each with its own unique approach and methodologies. Understanding the different types of empirical research will help you choose the most suitable design for your study. Here are some common types:

- Experimental Research : In this type, researchers manipulate one or more independent variables to observe their impact on dependent variables. It's highly controlled and often conducted in a laboratory setting.

- Observational Research : Observational research involves the systematic observation of subjects or phenomena without intervention. Researchers are passive observers, documenting behaviors, events, or patterns.

- Survey Research : Surveys are used to collect data through structured questionnaires or interviews. This method is efficient for gathering information from a large number of participants.

- Case Study Research : Case studies focus on in-depth exploration of one or a few cases. Researchers gather detailed information through various sources such as interviews, documents, and observations.

- Qualitative Research : Qualitative research aims to understand behaviors, experiences, and opinions in depth. It often involves open-ended questions, interviews, and thematic analysis.

- Quantitative Research : Quantitative research collects numerical data and relies on statistical analysis to draw conclusions. It involves structured questionnaires, experiments, and surveys.

Your choice of research type should align with your research questions and objectives. Experimental research, for example, is ideal for testing cause-and-effect relationships, while qualitative research is more suitable for exploring complex phenomena.

Experimental Design

Experimental research is a systematic approach to studying causal relationships. It's characterized by the manipulation of one or more independent variables while controlling for other factors. Here are some key aspects of experimental design:

- Control and Experimental Groups : Participants are randomly assigned to either a control group or an experimental group. The independent variable is manipulated for the experimental group but not for the control group.

- Randomization : Randomization is crucial to eliminate bias in group assignment. It ensures that each participant has an equal chance of being in either group.

- Hypothesis Testing : Experimental research often involves hypothesis testing. Researchers formulate hypotheses about the expected effects of the independent variable and use statistical analysis to test these hypotheses.

Observational Design

Observational research entails careful and systematic observation of subjects or phenomena. It's advantageous when you want to understand natural behaviors or events. Key aspects of observational design include:

- Participant Observation : Researchers immerse themselves in the environment they are studying. They become part of the group being observed, allowing for a deep understanding of behaviors.

- Non-Participant Observation : In non-participant observation, researchers remain separate from the subjects. They observe and document behaviors without direct involvement.

- Data Collection Methods : Observational research can involve various data collection methods, such as field notes, video recordings, photographs, or coding of observed behaviors.

Survey Design

Surveys are a popular choice for collecting data from a large number of participants. Effective survey design is essential to ensure the validity and reliability of your data. Consider the following:

- Questionnaire Design : Create clear and concise questions that are easy for participants to understand. Avoid leading or biased questions.

- Sampling Methods : Decide on the appropriate sampling method for your study, whether it's random, stratified, or convenience sampling.

- Data Collection Tools : Choose the right tools for data collection, whether it's paper surveys, online questionnaires, or face-to-face interviews.

Case Study Design

Case studies are an in-depth exploration of one or a few cases to gain a deep understanding of a particular phenomenon. Key aspects of case study design include:

- Single Case vs. Multiple Case Studies : Decide whether you'll focus on a single case or multiple cases. Single case studies are intensive and allow for detailed examination, while multiple case studies provide comparative insights.

- Data Collection Methods : Gather data through interviews, observations, document analysis, or a combination of these methods.

Qualitative vs. Quantitative Research

In empirical research, you'll often encounter the distinction between qualitative and quantitative research . Here's a closer look at these two approaches:

- Qualitative Research : Qualitative research seeks an in-depth understanding of human behavior, experiences, and perspectives. It involves open-ended questions, interviews, and the analysis of textual or narrative data. Qualitative research is exploratory and often used when the research question is complex and requires a nuanced understanding.

- Quantitative Research : Quantitative research collects numerical data and employs statistical analysis to draw conclusions. It involves structured questionnaires, experiments, and surveys. Quantitative research is ideal for testing hypotheses and establishing cause-and-effect relationships.

Understanding the various research design options is crucial in determining the most appropriate approach for your study. Your choice should align with your research questions, objectives, and the nature of the phenomenon you're investigating.

Data Collection for Empirical Research

Now that you've established your research design, it's time to roll up your sleeves and collect the data that will fuel your empirical research. Effective data collection is essential for obtaining accurate and reliable results.

Sampling Methods

Sampling methods are critical in empirical research, as they determine the subset of individuals or elements from your target population that you will study. Here are some standard sampling methods:

- Random Sampling : Random sampling ensures that every member of the population has an equal chance of being selected. It minimizes bias and is often used in quantitative research.

- Stratified Sampling : Stratified sampling involves dividing the population into subgroups or strata based on specific characteristics (e.g., age, gender, location). Samples are then randomly selected from each stratum, ensuring representation of all subgroups.

- Convenience Sampling : Convenience sampling involves selecting participants who are readily available or easily accessible. While it's convenient, it may introduce bias and limit the generalizability of results.

- Snowball Sampling : Snowball sampling is instrumental when studying hard-to-reach or hidden populations. One participant leads you to another, creating a "snowball" effect. This method is common in qualitative research.

- Purposive Sampling : In purposive sampling, researchers deliberately select participants who meet specific criteria relevant to their research questions. It's often used in qualitative studies to gather in-depth information.

The choice of sampling method depends on the nature of your research, available resources, and the degree of precision required. It's crucial to carefully consider your sampling strategy to ensure that your sample accurately represents your target population.

Data Collection Instruments

Data collection instruments are the tools you use to gather information from your participants or sources. These instruments should be designed to capture the data you need accurately. Here are some popular data collection instruments:

- Questionnaires : Questionnaires consist of structured questions with predefined response options. When designing questionnaires, consider the clarity of questions, the order of questions, and the response format (e.g., Likert scale , multiple-choice).

- Interviews : Interviews involve direct communication between the researcher and participants. They can be structured (with predetermined questions) or unstructured (open-ended). Effective interviews require active listening and probing for deeper insights.

- Observations : Observations entail systematically and objectively recording behaviors, events, or phenomena. Researchers must establish clear criteria for what to observe, how to record observations, and when to observe.

- Surveys : Surveys are a common data collection instrument for quantitative research. They can be administered through various means, including online surveys, paper surveys, and telephone surveys.

- Documents and Archives : In some cases, data may be collected from existing documents, records, or archives. Ensure that the sources are reliable, relevant, and properly documented.

To streamline your process and gather insights with precision and efficiency, consider leveraging innovative tools like Appinio . With Appinio's intuitive platform, you can harness the power of real-time consumer data to inform your research decisions effectively. Whether you're conducting surveys, interviews, or observations, Appinio empowers you to define your target audience, collect data from diverse demographics, and analyze results seamlessly.

By incorporating Appinio into your data collection toolkit, you can unlock a world of possibilities and elevate the impact of your empirical research. Ready to revolutionize your approach to data collection?

Book a Demo

Data Collection Procedures

Data collection procedures outline the step-by-step process for gathering data. These procedures should be meticulously planned and executed to maintain the integrity of your research.

- Training : If you have a research team, ensure that they are trained in data collection methods and protocols. Consistency in data collection is crucial.

- Pilot Testing : Before launching your data collection, conduct a pilot test with a small group to identify any potential problems with your instruments or procedures. Make necessary adjustments based on feedback.

- Data Recording : Establish a systematic method for recording data. This may include timestamps, codes, or identifiers for each data point.

- Data Security : Safeguard the confidentiality and security of collected data. Ensure that only authorized individuals have access to the data.

- Data Storage : Properly organize and store your data in a secure location, whether in physical or digital form. Back up data to prevent loss.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical considerations are paramount in empirical research, as they ensure the well-being and rights of participants are protected.

- Informed Consent : Obtain informed consent from participants, providing clear information about the research purpose, procedures, risks, and their right to withdraw at any time.

- Privacy and Confidentiality : Protect the privacy and confidentiality of participants. Ensure that data is anonymized and sensitive information is kept confidential.

- Beneficence : Ensure that your research benefits participants and society while minimizing harm. Consider the potential risks and benefits of your study.

- Honesty and Integrity : Conduct research with honesty and integrity. Report findings accurately and transparently, even if they are not what you expected.

- Respect for Participants : Treat participants with respect, dignity, and sensitivity to cultural differences. Avoid any form of coercion or manipulation.

- Institutional Review Board (IRB) : If required, seek approval from an IRB or ethics committee before conducting your research, particularly when working with human participants.

Adhering to ethical guidelines is not only essential for the ethical conduct of research but also crucial for the credibility and validity of your study. Ethical research practices build trust between researchers and participants and contribute to the advancement of knowledge with integrity.

With a solid understanding of data collection, including sampling methods, instruments, procedures, and ethical considerations, you are now well-equipped to gather the data needed to answer your research questions.

Empirical Research Data Analysis

Now comes the exciting phase of data analysis, where the raw data you've diligently collected starts to yield insights and answers to your research questions. We will explore the various aspects of data analysis, from preparing your data to drawing meaningful conclusions through statistics and visualization.

Data Preparation

Data preparation is the crucial first step in data analysis. It involves cleaning, organizing, and transforming your raw data into a format that is ready for analysis. Effective data preparation ensures the accuracy and reliability of your results.

- Data Cleaning : Identify and rectify errors, missing values, and inconsistencies in your dataset. This may involve correcting typos, removing outliers, and imputing missing data.

- Data Coding : Assign numerical values or codes to categorical variables to make them suitable for statistical analysis. For example, converting "Yes" and "No" to 1 and 0.

- Data Transformation : Transform variables as needed to meet the assumptions of the statistical tests you plan to use. Common transformations include logarithmic or square root transformations.

- Data Integration : If your data comes from multiple sources, integrate it into a unified dataset, ensuring that variables match and align.

- Data Documentation : Maintain clear documentation of all data preparation steps, as well as the rationale behind each decision. This transparency is essential for replicability.

Effective data preparation lays the foundation for accurate and meaningful analysis. It allows you to trust the results that will follow in the subsequent stages.

Descriptive Statistics

Descriptive statistics help you summarize and make sense of your data by providing a clear overview of its key characteristics. These statistics are essential for understanding the central tendencies, variability, and distribution of your variables. Descriptive statistics include:

- Measures of Central Tendency : These include the mean (average), median (middle value), and mode (most frequent value). They help you understand the typical or central value of your data.

- Measures of Dispersion : Measures like the range, variance, and standard deviation provide insights into the spread or variability of your data points.

- Frequency Distributions : Creating frequency distributions or histograms allows you to visualize the distribution of your data across different values or categories.

Descriptive statistics provide the initial insights needed to understand your data's basic characteristics, which can inform further analysis.

Inferential Statistics

Inferential statistics take your analysis to the next level by allowing you to make inferences or predictions about a larger population based on your sample data. These methods help you test hypotheses and draw meaningful conclusions. Key concepts in inferential statistics include:

- Hypothesis Testing : Hypothesis tests (e.g., t-tests, chi-squared tests) help you determine whether observed differences or associations in your data are statistically significant or occurred by chance.

- Confidence Intervals : Confidence intervals provide a range within which population parameters (e.g., population mean) are likely to fall based on your sample data.

- Regression Analysis : Regression models (linear, logistic, etc.) help you explore relationships between variables and make predictions.

- Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) : ANOVA tests are used to compare means between multiple groups, allowing you to assess whether differences are statistically significant.

Inferential statistics are powerful tools for drawing conclusions from your data and assessing the generalizability of your findings to the broader population.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis is employed when working with non-numerical data, such as text, interviews, or open-ended survey responses. It focuses on understanding the underlying themes, patterns, and meanings within qualitative data. Qualitative analysis techniques include:

- Thematic Analysis : Identifying and analyzing recurring themes or patterns within textual data.

- Content Analysis : Categorizing and coding qualitative data to extract meaningful insights.

- Grounded Theory : Developing theories or frameworks based on emergent themes from the data.

- Narrative Analysis : Examining the structure and content of narratives to uncover meaning.

Qualitative data analysis provides a rich and nuanced understanding of complex phenomena and human experiences.

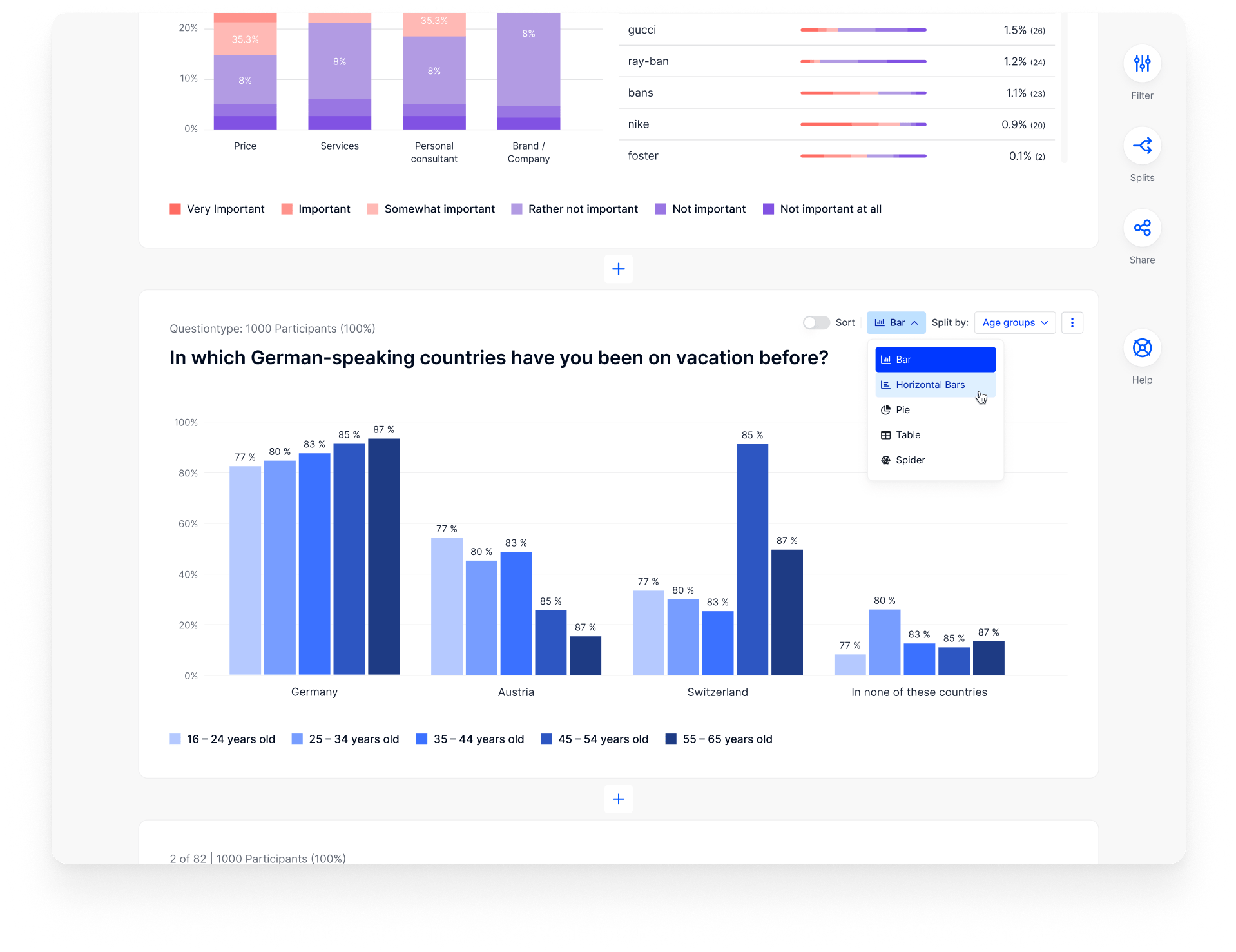

Data Visualization

Data visualization is the art of representing data graphically to make complex information more understandable and accessible. Effective data visualization can reveal patterns, trends, and outliers in your data. Common types of data visualization include:

- Bar Charts and Histograms : Used to display the distribution of categorical data or discrete data .

- Line Charts : Ideal for showing trends and changes in data over time.

- Scatter Plots : Visualize relationships and correlations between two variables.

- Pie Charts : Display the composition of a whole in terms of its parts.

- Heatmaps : Depict patterns and relationships in multidimensional data through color-coding.

- Box Plots : Provide a summary of the data distribution, including outliers.

- Interactive Dashboards : Create dynamic visualizations that allow users to explore data interactively.

Data visualization not only enhances your understanding of the data but also serves as a powerful communication tool to convey your findings to others.

As you embark on the data analysis phase of your empirical research, remember that the specific methods and techniques you choose will depend on your research questions, data type, and objectives. Effective data analysis transforms raw data into valuable insights, bringing you closer to the answers you seek.

How to Report Empirical Research Results?

At this stage, you get to share your empirical research findings with the world. Effective reporting and presentation of your results are crucial for communicating your research's impact and insights.

1. Write the Research Paper

Writing a research paper is the culmination of your empirical research journey. It's where you synthesize your findings, provide context, and contribute to the body of knowledge in your field.

- Title and Abstract : Craft a clear and concise title that reflects your research's essence. The abstract should provide a brief summary of your research objectives, methods, findings, and implications.

- Introduction : In the introduction, introduce your research topic, state your research questions or hypotheses, and explain the significance of your study. Provide context by discussing relevant literature.

- Methods : Describe your research design, data collection methods, and sampling procedures. Be precise and transparent, allowing readers to understand how you conducted your study.

- Results : Present your findings in a clear and organized manner. Use tables, graphs, and statistical analyses to support your results. Avoid interpreting your findings in this section; focus on the presentation of raw data.

- Discussion : Interpret your findings and discuss their implications. Relate your results to your research questions and the existing literature. Address any limitations of your study and suggest avenues for future research.

- Conclusion : Summarize the key points of your research and its significance. Restate your main findings and their implications.

- References : Cite all sources used in your research following a specific citation style (e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago). Ensure accuracy and consistency in your citations.

- Appendices : Include any supplementary material, such as questionnaires, data coding sheets, or additional analyses, in the appendices.

Writing a research paper is a skill that improves with practice. Ensure clarity, coherence, and conciseness in your writing to make your research accessible to a broader audience.

2. Create Visuals and Tables

Visuals and tables are powerful tools for presenting complex data in an accessible and understandable manner.

- Clarity : Ensure that your visuals and tables are clear and easy to interpret. Use descriptive titles and labels.

- Consistency : Maintain consistency in formatting, such as font size and style, across all visuals and tables.

- Appropriateness : Choose the most suitable visual representation for your data. Bar charts, line graphs, and scatter plots work well for different types of data.

- Simplicity : Avoid clutter and unnecessary details. Focus on conveying the main points.

- Accessibility : Make sure your visuals and tables are accessible to a broad audience, including those with visual impairments.

- Captions : Include informative captions that explain the significance of each visual or table.

Compelling visuals and tables enhance the reader's understanding of your research and can be the key to conveying complex information efficiently.

3. Interpret Findings

Interpreting your findings is where you bridge the gap between data and meaning. It's your opportunity to provide context, discuss implications, and offer insights. When interpreting your findings:

- Relate to Research Questions : Discuss how your findings directly address your research questions or hypotheses.

- Compare with Literature : Analyze how your results align with or deviate from previous research in your field. What insights can you draw from these comparisons?

- Discuss Limitations : Be transparent about the limitations of your study. Address any constraints, biases, or potential sources of error.

- Practical Implications : Explore the real-world implications of your findings. How can they be applied or inform decision-making?

- Future Research Directions : Suggest areas for future research based on the gaps or unanswered questions that emerged from your study.

Interpreting findings goes beyond simply presenting data; it's about weaving a narrative that helps readers grasp the significance of your research in the broader context.

With your research paper written, structured, and enriched with visuals, and your findings expertly interpreted, you are now prepared to communicate your research effectively. Sharing your insights and contributing to the body of knowledge in your field is a significant accomplishment in empirical research.

Examples of Empirical Research

To solidify your understanding of empirical research, let's delve into some real-world examples across different fields. These examples will illustrate how empirical research is applied to gather data, analyze findings, and draw conclusions.

Social Sciences

In the realm of social sciences, consider a sociological study exploring the impact of socioeconomic status on educational attainment. Researchers gather data from a diverse group of individuals, including their family backgrounds, income levels, and academic achievements.

Through statistical analysis, they can identify correlations and trends, revealing whether individuals from lower socioeconomic backgrounds are less likely to attain higher levels of education. This empirical research helps shed light on societal inequalities and informs policymakers on potential interventions to address disparities in educational access.

Environmental Science

Environmental scientists often employ empirical research to assess the effects of environmental changes. For instance, researchers studying the impact of climate change on wildlife might collect data on animal populations, weather patterns, and habitat conditions over an extended period.

By analyzing this empirical data, they can identify correlations between climate fluctuations and changes in wildlife behavior, migration patterns, or population sizes. This empirical research is crucial for understanding the ecological consequences of climate change and informing conservation efforts.

Business and Economics

In the business world, empirical research is essential for making data-driven decisions. Consider a market research study conducted by a business seeking to launch a new product. They collect data through surveys , focus groups , and consumer behavior analysis.

By examining this empirical data, the company can gauge consumer preferences, demand, and potential market size. Empirical research in business helps guide product development, pricing strategies, and marketing campaigns, increasing the likelihood of a successful product launch.

Psychological studies frequently rely on empirical research to understand human behavior and cognition. For instance, a psychologist interested in examining the impact of stress on memory might design an experiment. Participants are exposed to stress-inducing situations, and their memory performance is assessed through various tasks.

By analyzing the data collected, the psychologist can determine whether stress has a significant effect on memory recall. This empirical research contributes to our understanding of the complex interplay between psychological factors and cognitive processes.

These examples highlight the versatility and applicability of empirical research across diverse fields. Whether in medicine, social sciences, environmental science, business, or psychology, empirical research serves as a fundamental tool for gaining insights, testing hypotheses, and driving advancements in knowledge and practice.

Conclusion for Empirical Research

Empirical research is a powerful tool for gaining insights, testing hypotheses, and making informed decisions. By following the steps outlined in this guide, you've learned how to select research topics, collect data, analyze findings, and effectively communicate your research to the world. Remember, empirical research is a journey of discovery, and each step you take brings you closer to a deeper understanding of the world around you. Whether you're a scientist, a student, or someone curious about the process, the principles of empirical research empower you to explore, learn, and contribute to the ever-expanding realm of knowledge.

How to Collect Data for Empirical Research?

Introducing Appinio , the real-time market research platform revolutionizing how companies gather consumer insights for their empirical research endeavors. With Appinio, you can conduct your own market research in minutes, gaining valuable data to fuel your data-driven decisions.

Appinio is more than just a market research platform; it's a catalyst for transforming the way you approach empirical research, making it exciting, intuitive, and seamlessly integrated into your decision-making process.

Here's why Appinio is the go-to solution for empirical research:

- From Questions to Insights in Minutes : With Appinio's streamlined process, you can go from formulating your research questions to obtaining actionable insights in a matter of minutes, saving you time and effort.

- Intuitive Platform for Everyone : No need for a PhD in research; Appinio's platform is designed to be intuitive and user-friendly, ensuring that anyone can navigate and utilize it effectively.

- Rapid Response Times : With an average field time of under 23 minutes for 1,000 respondents, Appinio delivers rapid results, allowing you to gather data swiftly and efficiently.

- Global Reach with Targeted Precision : With access to over 90 countries and the ability to define target groups based on 1200+ characteristics, Appinio empowers you to reach your desired audience with precision and ease.

Get free access to the platform!

Join the loop 💌

Be the first to hear about new updates, product news, and data insights. We'll send it all straight to your inbox.

Get the latest market research news straight to your inbox! 💌

Wait, there's more

30.05.2024 | 29min read

Pareto Analysis: Definition, Pareto Chart, Examples

28.05.2024 | 32min read

What is Systematic Sampling? Definition, Types, Examples

16.05.2024 | 30min read

Time Series Analysis: Definition, Types, Techniques, Examples

- University of Memphis Libraries

- Research Guides

Empirical Research: Defining, Identifying, & Finding

Defining empirical research, what is empirical research, quantitative or qualitative.

- Introduction

- Database Tools

- Search Terms

- Image Descriptions

Calfee & Chambliss (2005) (UofM login required) describe empirical research as a "systematic approach for answering certain types of questions." Those questions are answered "[t]hrough the collection of evidence under carefully defined and replicable conditions" (p. 43).

The evidence collected during empirical research is often referred to as "data."

Characteristics of Empirical Research

Emerald Publishing's guide to conducting empirical research identifies a number of common elements to empirical research:

- A research question , which will determine research objectives.

- A particular and planned design for the research, which will depend on the question and which will find ways of answering it with appropriate use of resources.

- The gathering of primary data , which is then analysed.

- A particular methodology for collecting and analysing the data, such as an experiment or survey.

- The limitation of the data to a particular group, area or time scale, known as a sample [emphasis added]: for example, a specific number of employees of a particular company type, or all users of a library over a given time scale. The sample should be somehow representative of a wider population.

- The ability to recreate the study and test the results. This is known as reliability .

- The ability to generalize from the findings to a larger sample and to other situations.

If you see these elements in a research article, you can feel confident that you have found empirical research. Emerald's guide goes into more detail on each element.

Empirical research methodologies can be described as quantitative, qualitative, or a mix of both (usually called mixed-methods).

Ruane (2016) (UofM login required) gets at the basic differences in approach between quantitative and qualitative research:

- Quantitative research -- an approach to documenting reality that relies heavily on numbers both for the measurement of variables and for data analysis (p. 33).

- Qualitative research -- an approach to documenting reality that relies on words and images as the primary data source (p. 33).

Both quantitative and qualitative methods are empirical . If you can recognize that a research study is quantitative or qualitative study, then you have also recognized that it is empirical study.

Below are information on the characteristics of quantitative and qualitative research. This video from Scribbr also offers a good overall introduction to the two approaches to research methodology:

Characteristics of Quantitative Research

Researchers test hypotheses, or theories, based in assumptions about causality, i.e. we expect variable X to cause variable Y. Variables have to be controlled as much as possible to ensure validity. The results explain the relationship between the variables. Measures are based in pre-defined instruments.

Examples: experimental or quasi-experimental design, pretest & post-test, survey or questionnaire with closed-ended questions. Studies that identify factors that influence an outcomes, the utility of an intervention, or understanding predictors of outcomes.

Characteristics of Qualitative Research

Researchers explore “meaning individuals or groups ascribe to social or human problems (Creswell & Creswell, 2018, p3).” Questions and procedures emerge rather than being prescribed. Complexity, nuance, and individual meaning are valued. Research is both inductive and deductive. Data sources are multiple and varied, i.e. interviews, observations, documents, photographs, etc. The researcher is a key instrument and must be reflective of their background, culture, and experiences as influential of the research.

Examples: open question interviews and surveys, focus groups, case studies, grounded theory, ethnography, discourse analysis, narrative, phenomenology, participatory action research.

Calfee, R. C. & Chambliss, M. (2005). The design of empirical research. In J. Flood, D. Lapp, J. R. Squire, & J. Jensen (Eds.), Methods of research on teaching the English language arts: The methodology chapters from the handbook of research on teaching the English language arts (pp. 43-78). Routledge. http://ezproxy.memphis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=125955&site=eds-live&scope=site .

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

How to... conduct empirical research . (n.d.). Emerald Publishing. https://www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/how-to/research-methods/conduct-empirical-research .

Scribbr. (2019). Quantitative vs. qualitative: The differences explained [video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=a-XtVF7Bofg .

Ruane, J. M. (2016). Introducing social research methods : Essentials for getting the edge . Wiley-Blackwell. http://ezproxy.memphis.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=1107215&site=eds-live&scope=site .

- << Previous: Home

- Next: Identifying Empirical Research >>

- Last Updated: Apr 2, 2024 11:25 AM

- URL: https://libguides.memphis.edu/empirical-research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Methods Used in Economic Research: An Empirical Study of Trends and Levels

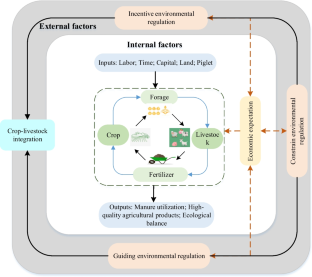

The methods used in economic research are analyzed on a sample of all 3,415 regular research papers published in 10 general interest journals every 5th year from 1997 to 2017. The papers are classified into three main groups by method: theory, experiments, and empirics. The theory and empirics groups are almost equally large. Most empiric papers use the classical method, which derives an operational model from theory and runs regressions. The number of papers published increases by 3.3% p.a. Two trends are highly significant: The fraction of theoretical papers has fallen by 26 pp (percentage points), while the fraction of papers using the classical method has increased by 15 pp. Economic theory predicts that such papers exaggerate, and the papers that have been analyzed by meta-analysis confirm the prediction. It is discussed if other methods have smaller problems.

1 Introduction

This paper studies the pattern in the research methods in economics by a sample of 3,415 regular papers published in the years 1997, 2002, 2007, 2012, and 2017 in 10 journals. The analysis builds on the beliefs that truth exists, but it is difficult to find, and that all the methods listed in the next paragraph have problems as discussed in Sections 2 and 4. Hereby I do not imply that all – or even most – papers have these problems, but we rarely know how serious it is when we read a paper. A key aspect of the problem is that a “perfect” study is very demanding and requires far too much space to report, especially if the paper looks for usable results. Thus, each paper is just one look at an aspect of the problem analyzed. Only when many studies using different methods reach a joint finding, we can trust that it is true.

Section 2 discusses the classification of papers by method into three main categories: (M1) Theory , with three subgroups: (M1.1) economic theory, (M1.2) statistical methods, and (M1.3) surveys. (M2) Experiments , with two subgroups: (M2.1) lab experiments and (M2.2) natural experiments. (M3) Empirics , with three subgroups: (M3.1) descriptive, (M3.2) classical empirics, and (M3.3) newer empirics. More than 90% of the papers are easy to classify, but a stochastic element enters in the classification of the rest. Thus, the study has some – hopefully random – measurement errors.

Section 3 discusses the sample of journals chosen. The choice has been limited by the following main criteria: It should be good journals below the top ten A-journals, i.e., my article covers B-journals, which are the journals where most research economists publish. It should be general interest journals, and the journals should be so different that it is likely that patterns that generalize across these journals apply to more (most?) journals. The Appendix gives some crude counts of researchers, departments, and journals. It assesses that there are about 150 B-level journals, but less than half meet the criteria, so I have selected about 15% of the possible ones. This is the most problematic element in the study. If the reader accepts my choice, the paper tells an interesting story about economic research.

All B-level journals try hard to have a serious refereeing process. If our selection is representative, the 150 journals have increased the annual number of papers published from about 7,500 in 1997 to about 14,000 papers in 2017, giving about 200,000 papers for the period. Thus, the B-level dominates our science. Our sample is about 6% for the years covered, but less than 2% of all papers published in B-journals in the period. However, it is a larger fraction of the papers in general interest journals.

It is impossible for anyone to read more than a small fraction of this flood of papers. Consequently, researchers compete for space in journals and for attention from the readers, as measured in the form of citations. It should be uncontroversial that papers that hold a clear message are easier to publish and get more citations. Thus, an element of sales promotion may enter papers in the form of exaggeration , which is a joint problem for all eight methods. This is in accordance with economic theory that predicts that rational researchers report exaggerated results; see Paldam ( 2016 , 2018 ). For empirical papers, meta-methods exist to summarize the results from many papers, notably papers using regressions. Section 4.4 reports that meta-studies find that exaggeration is common.

The empirical literature surveying the use of research methods is quite small, as I have found two articles only: Hamermesh ( 2013 ) covers 748 articles in 6 years a decade apart studies in three A-journals using a slightly different classification of methods, [1] while my study covers B-journals. Angrist, Azoulay, Ellison, Hill, and Lu ( 2017 ) use a machine-learning classification of 134,000 papers in 80 journals to look at the three main methods. My study subdivide the three categories into eight. The machine-learning algorithm is only sketched, so the paper is difficult to replicate, but it is surely a major effort. A key result in both articles is the strong decrease of theory in economic publications. This finding is confirmed, and it is shown that the corresponding increase in empirical articles is concentrated on the classical method.

I have tried to explain what I have done, so that everything is easy to replicate, in full or for one journal or one year. The coding of each article is available at least for the next five years. I should add that I have been in economic research for half a century. Some of the assessments in the paper will reflect my observations/experience during this period (indicated as my assessments). This especially applies to the judgements expressed in Section 4.

2 The eight categories

Table 1 reports that the annual number of papers in the ten journals has increased 1.9 times, or by 3.3% per year. The Appendix gives the full counts per category, journal, and year. By looking at data over two decades, I study how economic research develops. The increase in the production of papers is caused by two factors: The increase in the number of researchers. The increasing importance of publications for the careers of researchers.

The 3,415 papers

2.1 (M1) Theory: subgroups (M1.1) to (M1.3)

Table 2 lists the groups and main numbers discussed in the rest of the paper. Section 2.1 discusses (M1) theory. Section 2.2 covers (M2) experimental methods, while Section 2.3 looks at (M3) empirical methods using statistical inference from data.

The 3,415 papers – fractions in percent

The change of the fractions from 1997 to 2017 in percentage points

Note: Section 3.4 tests if the pattern observed in Table 3 is statistically significant. The Appendix reports the full data.

2.1.1 (M1.1) Economic theory

Papers are where the main content is the development of a theoretical model. The ideal theory paper presents a (simple) new model that recasts the way we look at something important. Such papers are rare and obtain large numbers of citations. Most theoretical papers present variants of known models and obtain few citations.

In a few papers, the analysis is verbal, but more than 95% rely on mathematics, though the technical level differs. Theory papers may start by a descriptive introduction giving the stylized fact the model explains, but the bulk of the paper is the formal analysis, building a model and deriving proofs of some propositions from the model. It is often demonstrated how the model works by a set of simulations, including a calibration made to look realistic. However, the calibrations differ greatly by the efforts made to reach realism. Often, the simulations are in lieu of an analytical solution or just an illustration suggesting the magnitudes of the results reached.

Theoretical papers suffer from the problem known as T-hacking , [2] where the able author by a careful selection of assumptions can tailor the theory to give the results desired. Thus, the proofs made from the model may represent the ability and preferences of the researcher rather than the properties of the economy.

2.1.2 (M1.2) Statistical method

Papers reporting new estimators and tests are published in a handful of specialized journals in econometrics and mathematical statistics – such journals are not included. In our general interest journals, some papers compare estimators on actual data sets. If the demonstration of a methodological improvement is the main feature of the paper, it belongs to (M1.2), but if the economic interpretation is the main point of the paper, it belongs to (M3.2) or (M3.3). [3]

Some papers, including a special issue of Empirical Economics (vol. 53–1), deal with forecasting models. Such models normally have a weak relation to economic theory. They are sometimes justified precisely because of their eclectic nature. They are classified as either (M1.2) or (M3.1), depending upon the focus. It appears that different methods work better on different data sets, and perhaps a trade-off exists between the user-friendliness of the model and the improvement reached.

2.1.3 (M1.3) Surveys

When the literature in a certain field becomes substantial, it normally presents a motley picture with an amazing variation, especially when different schools exist in the field. Thus, a survey is needed, and our sample contains 68 survey articles. They are of two types, where the second type is still rare:

2.1.3.1 (M1.3.1) Assessed surveys