- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Systematic review article, a systematic literature review of consumers' cognitive-affective needs in product design from 1999 to 2019.

- 1 Industrial and Systems Engineering Graduate Program (PPGEPS), Polytechnic School at Pontifical Catholic University of Paraná, Curitiba, Brazil

- 2 Production Engineering Graduate Program (PPGEP), Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

Understanding consumer cognitive and affective needs is a complex and tricky challenge for consumer studies. Creating and defining product attributes that meet the consumers' personal wishes and needs in different contexts is a challenge that demands new perspectives because there are mismatches between the objective of companies and the consumer's objective, which indicates the need for products to become increasingly consumer-oriented. Product design approaches aim to bring the product and consumer closer together. The objective of this study is to investigate the application of the cognitive and affective needs of the consumer in product design through a systematic review of the literature of publications carried out in the last 20 years. This article selects research carried out in the specific area of cognitive and affective product design and defines the state of the art of the main areas, challenges, and trends. The conclusion that was reached is that cognitive approaches have been updated, are more associated with technology, and so are focused and oriented toward the ease and friendliness of the product. In contrast, affective approaches are older and focus on the quality of life, satisfaction, pleasure, and friendliness of the product. This review indicates that the emotional focus of change for cognitive complexity is due to an understanding of the affective and emotional subjectivity of the consumers and how they can translate these requirements into product attributes. These approaches seem to lose their strength or preference in the areas of design and engineering for more rational and logical cognitive applications, and therefore are more statistically verifiable. Advances in neuroscience are focused on applications in marketing and consumer psychology and some cognitive and affective product designs.

Introduction

Cognitive and affective product design is strategic for companies who wish to create deep connections with consumers through meaningful associations ( Orth and Thurgood, 2018 ). These connections are valued for having intrinsic links with their beliefs, experiences, memories, people, places, or even personal values ( Noble and Kumar, 2008 ). Thus, the Product Design (PD) and New Product Development (NPD) teams seek to understand which main cognitive and affective elements exist in the subjective product experience, relevant to consumer purchase intention and choice ( Homburg et al., 2015 ).

The fact is that some products can be both comfortable and pleasant to use and consume, and thus promote both functional and “cognitive” as well as hedonic and “affective” experiences ( Crilly et al., 2004 ; Khalid and Helander, 2004 , 2006 ; Khalid, 2006 ; Seva and Helander, 2009 ; Wrigley, 2013 ). In previous reviews, these authors emphasize that such characteristics lead consumers to achieve their personal goals through functional, aesthetic, symbolic, semantic, formal, appearance, and status products, among many others. The design of the product aims to conceive and develop products that meet the needs and preferences of the consumer whether by better usability or functionality ( Li and Gunal, 2012 ; Greggianin et al., 2018 ). They create not only a product more pleasant and accessible to use and consume but also products that accommodate for style and aesthetic beauty, hedonic pleasure, sympathy, and other interests ( González-Sánchez and Gil-Iranzo, 2013 ). Through the evaluation and translation of opinions, the engineers and designers seek, to some extent, to produce happiness in the consumers' mind ( Demirbilek and Sener, 2003 ). However, the opinions are individual and subjective, resulting from the use or consumption experience, or product experience ( Schifferstein and Spence, 2008 ).

There were significant advances in product design before 1999, considering the processes of evaluation and the translation of consumers' cognitive and affective aspects. Among the relevant approaches found, Frijda (1986) deepened the research on emotions in products, focusing initially on facial expressions. For Frijda, emotions would tend to engage in behaviors influenced by the person's needs. Norman (1988) sought to include consumer accessibility in product design through resources with intense affective and emotional impact, popularizing the term user-centered design and simplifying the product's usability through greater functionality. Hauser and Clausing (1988) addressed quality as an essential requirement to meet consumer needs. The basis of the quality house was created so that product design activities could be carried out based on the wishes and needs of consumers. Another featured application was the kansei engineering methodology, as according to Nagamachi (1989) , this methodology aims to implement the feelings and demands of consumers in the operation and design of the product. This author proposed a methodology to measure psychological aspects, understood as the consumer's kansei.

In the field of product design, Desmet (2003) , Norman (1988) , Jordan (1998) , and Green and Jordan (1999) were pioneers in delving deeper into the product's affective and cognitive characteristics and in associating this information with the consumer's different cognitive and emotional levels. Since then, different research fields have studied ways of meeting consumers' subjective needs and preferences at different psychological levels ( Hong et al., 2008 ). The objective is to attract the consumer with products that provide innovative experiences with intense cognitive and affective impacts ( Kumar Ranganathan et al., 2013 ).

Ellsworth and Scherer (2003) highlight that, while affection refers to sentimental responses, cognition is used to interpret, comprehend, and understand the experience. Cognition understands and comprehends what is perceived, while affection promotes the learning and experience feeling in the interaction with the product. Norman (2004) argues that the cognitive system gives meaning to the world while the affective one is critical to it. Both complement each other and each system influences the other, with cognition providing affection and being affected by it ( Ashby et al., 1999 ; Coates, 2003 ; Crilly et al., 2004 ). However, the strategy of many designers is not clear on the importance of associating cognitive and affective needs of the consumer with the cognitive and affective attributes of the product, which creates a problem for the research field in product design ( Crilly et al., 2004 ; Khalid and Helander, 2004 ; Kumar Ranganathan et al., 2013 ; Zhou et al., 2013 ; Gómez-Corona et al., 2017 ; Hsu, 2017 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ). Khalid and Helander (2006) state that the consumer perceives reality in an affective (intuitive and experiential) and cognitive (analytical and rational) way, and separating emotion from cognition is a major deficiency of psychology and cognitive science in general. Emotions are not the cause of rational thinking, but they can motivate an interest in objectivity. Rational thinking affects feelings and affective thinking influences cognition. Therefore, the phenomena are inseparable.

Nevertheless, few integrated applications of cognitive and affective needs in product design are found in the literature. Although the opinion among researchers is that the cognitive and affective human systems belong to a single source of informational processing, the understanding and evaluation of the functioning of these systems are considered essentially “closed,” a “minefield” ( Khalid, 2006 ; Khalid and Helander, 2006 ), or a real “black box” ( Zhou et al., 2013 ; Diego-Mas and Alcaide-Marzal, 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ). Although there have been significant advances in the understanding of the combination of cognitive and affective systems ( Damasio, 2001 ; Damasio and Adolphs, 2001 ), areas of engineering and product design still face difficulties in uniting the two mental processes in the same applications. The justification for this research is to investigate the importance of advancing the study of consumers' cognitive and affective needs in the manner of product characteristics and attributes which is considered an essential path for product design ( Kumar Ranganathan et al., 2013 ).

In this sense, this article seeks to select the research carried out in the specific field of cognitive and affective product design and to identify the main areas, challenges, and trends of the applications as well as to advance the investigation of the problems which justify this research. From this, what would be the main research carried out in the last 20 years on the application of cognitive and affective needs regarding the characteristics and attributes of product design that can contribute to the advancement of consumer research?

Methods and Materials

Systematic literature review (slr).

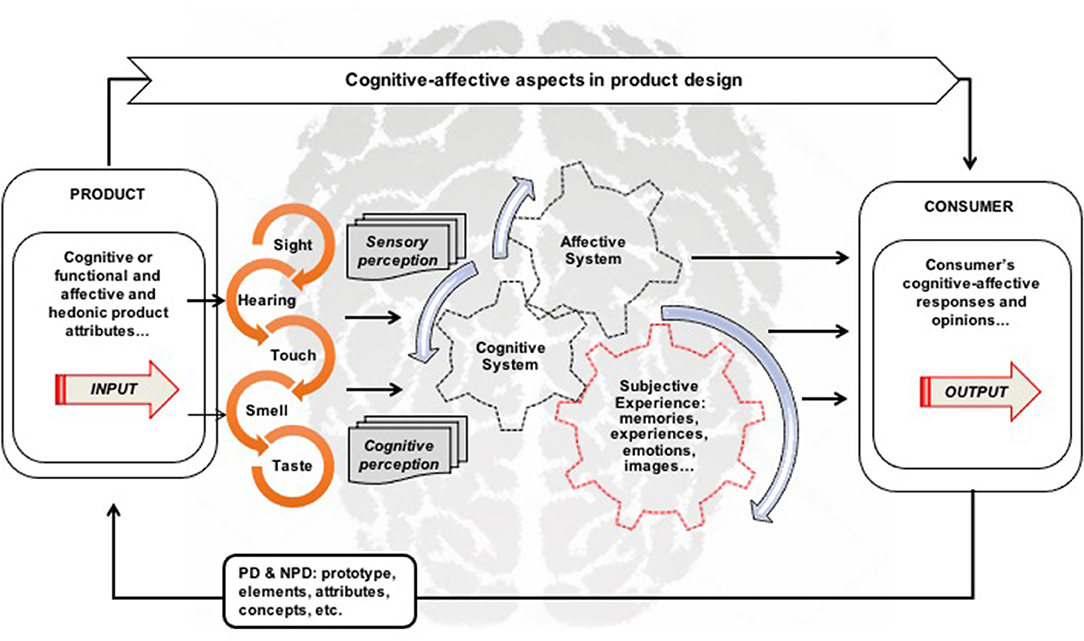

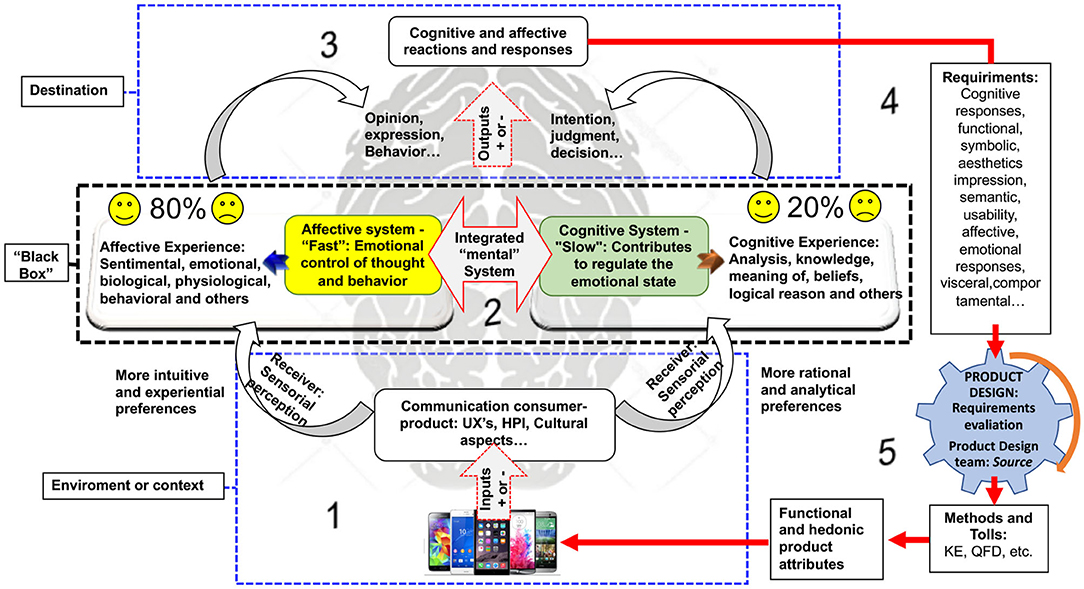

Through the studies presented so far, Figure 1 shows the starting point for the beginning of the research. This focuses on the cognitive and affective aspects derived from the product and the consumer. On the consumer side it involves senses of sensory perception, cognitive, and affective mental systems, and subjectivity experience when interacting with the product. On the product side, it generally involves cognitive attributes (functionality, usability, etc.) and affective attributes (pleasure, hedonism, pleasantness, etc.). This information is usually captured, evaluated, translated, and applied to product design.

Figure 1 . Conceptual framework of the cognitive and affective aspects in product design.

The practical applications of cognitive and affective aspects in the product design are summarized in the conceptual framework. To identify the most relevant literature related to the topics covered, this study conducted a systematic literature review (SLR) based on data from Cambridge Journals Online, Emerald Insight, IEEE Xplore, Scopus Science, Springer Link, Taylor and Francis, and other databases such as Google Scholar.

The SLR procedure is a research method that achieves results through information already described and published, which minimizes distortions and errors ( Jesson and Lacey, 2006 ; Mattioda et al., 2015 ; Randhawa et al., 2016 ). The study selected only articles that were: (i) peer-reviewed; (ii) written in the English language; and (iii) published in the last 20 years (from 1999 to 2019). The 20-year period aims to meet analysis robustness and the synthesis of the topics covered by considering the largest possible number of approaches that define the research object.

The search keywords are derived from the framework presented, and the selection of the articles was defined based on the following terms: cognitive, affective, or emotional aspects, and product and new products design. Based on these terms, the study searched the following keywords in the databases based on the crossing of the two groups of words: (i) cognitive aspects (“cognition” or “cognitive,” “cognitive design”) and affective aspects (“affect” or “affective,” “affective design,” “emotion,” or “emotional” and “emotion/emotional design”); and (ii) product design: “product design” (PD), “product development process” (PDP), “new product development” (NPD).

The PRISMA Flow Diagram

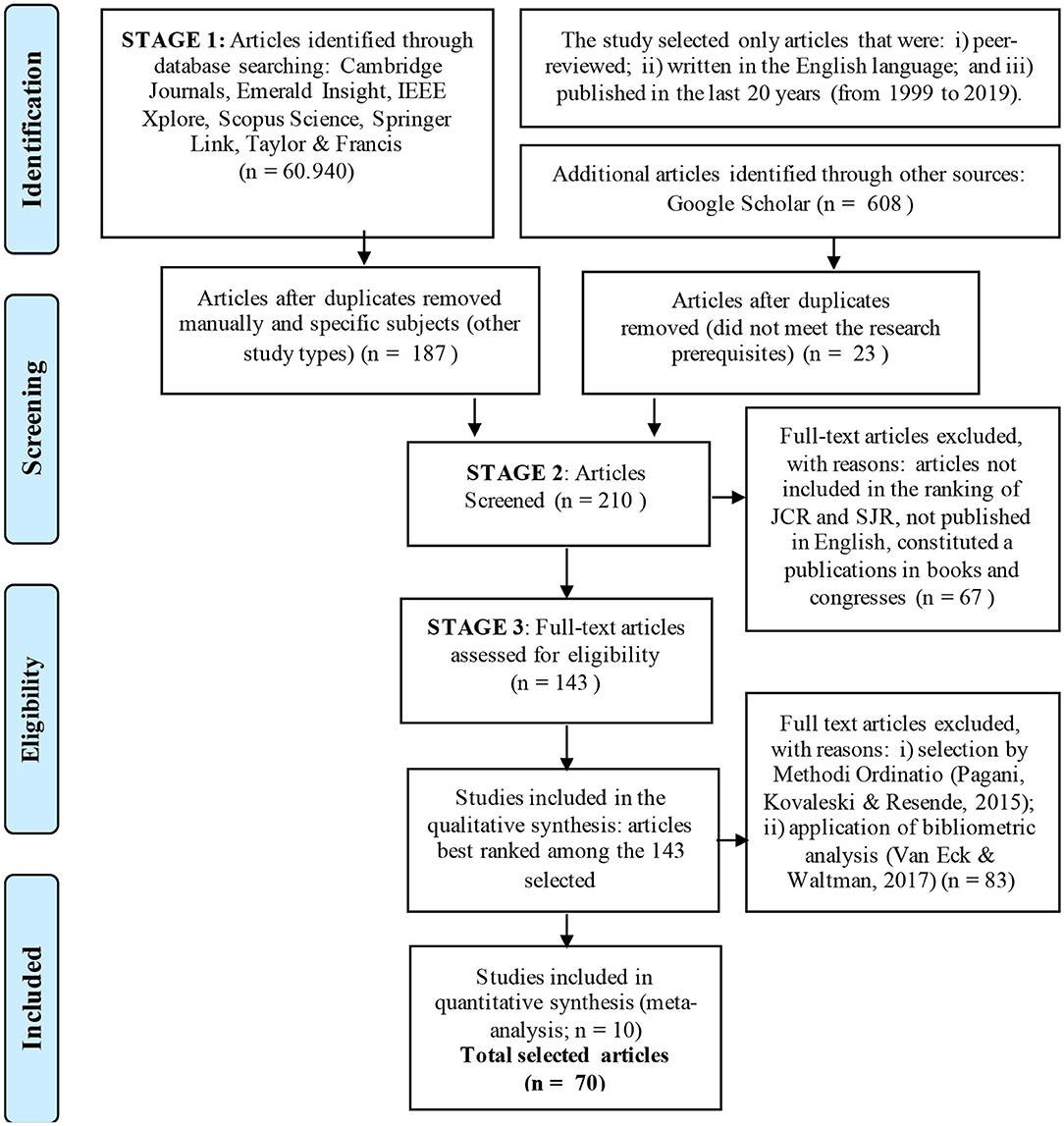

The PRISMA flow diagram ( Moher et al., 2009 ) was used to organize the SLR ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 . Flow diagram of systematic review process (based on the generic diagram in Moher et al., 2009 ).

In the first stage , the research was based on the crosschecking of the keywords. The search result for any subject in the databases included 60,940 articles. After directing the research to only specific subjects considering only the keywords, the result included 187 articles. The research made among Google Scholar's open and available databases resulted in 608 articles.

After identification , in the second stage , the research pre-selected the articles. From the 187 articles, among those that contained in their keywords the terms defined in the preliminary research, 47 of them were excluded because they were duplicated in the sample. After the exclusion of duplicate articles, in a language other than English, and from publications in books and congresses, only 23 articles met the research prerequisites from the 608 found in the open database of Google Scholar. Another exclusion criterion was the removal of articles published in journals not included in the ranking of JCR (Journal Citation Ranking) and SJR (Scimago Journal Ranking) impact factor, a requirement considered important for the next SLR stage. The result was a gross portfolio of 143 base articles for the selection by relevance.

After screening , for the third stage for the eligibility of articles, a qualitative synthesis was initiated.

Qualitative Synthesis

The selection criterion was defined by applying the Methodi Ordinatio ( Pagani et al., 2015 ) that uses the InOrdinatio index, the result of an equation that considers the “impact factor” relevance of the journal where the article is published, the “number of citations” and the importance of more “recent” works that have not yet obtained many citations from peers. In summary, the equation consists of adding the journal's impact factor, the number of citations the article received by its peers to a factor that considers the relevance of how recent the article is when considering its publication year, according to Equation (1):

where: (i) “IF” is the impact factor of the publication, (ii) “α” is a weighting factor that varies from 1 to 10, normally assigned by the researcher; (iii) “ResearchYear” is the year in which the research was developed; (iv) “PublishYear” is the year in which the article was published; and (v) “Σ Ci” is the number of times the article has been cited.

To identify the number of citations by peers, this study considered Google Scholar. The reason for this is the fact that several articles were not included in the main scientific databases that conduct bibliometric analyzes, and that calculate the number of citations by peers, such as Scopus, Proquest, or Elsevier. These databases did not show all articles selected in the initial search. Google Scholar presented all selected items in the gross portfolio after verification.

The “α” criterion was defined by the following formulation that takes into account the current publication status: “10” for publications made in the last 4 years; “8” for publications in the last 5–8 years; “6” for publications in the last 9–12 years; “4” for publications in the last 13–16 years; “2” for publications in the last 17–20 years; and “0” if there were any classic and relevant articles published more than 20 years ago and later inserted in the sample.

After the application of Equation 1 and data handling, the study obtained the InOrdinatio index of each article, for classification according to its scientific relevance for the research. The higher the value of the InOrdinatio index, the more relevant the article was considered. However, articles with more citations stood out in relation to the others and could leave some important studies out of the content analysis.

To solve this deficiency, the study developed a new criterion using the Ordinatio Method and applied it to reinforce the search for the most relevant articles for the research. The new criterion was configured through bibliometric analysis. The objective was to highlight the analysis through the articles initially selected by the research, considering the impact factor of the publication, the number of citations by the peers, and as a complementary addition verify the strength of the keywords chosen for the SLR, both in the occurrences of citation and in the total strength of the correlation links with other works in the gross portfolio.

Quantitative Synthesis

To improve the eligibility of the chosen papers the study considered and calculated all terms available in the title and keywords of the 143 articles in the gross portfolio. The objective was to compensate for the difference in the volume of citations by peers found in the oldest articles compared to the most recent and, therefore, little cited. To achieve this, the study developed a new adherence factor in order to verify the importance of articles that were not included in the previous selection. It also considered the article's proximity to the main topics covered, as presented at the beginning of this review, which justified further research.

The software Vosviewer 1.6.11 , designed for bibliometric network analysis ( Van Eck and Waltman, 2017 ), was used to identify the keywords with the highest occurrence and full strength of links among the main terms addressed by peers from the 143 articles in the gross portfolio. In the software application, the examples were obtained as a result of bibliographic coupling links among publications, co-authoring links among researchers, and occurrence links among terms or keywords. Among the options for a search item, there were links between different terms that point to the number of links between keywords. The total strength of the links between the keywords showed more than one link and the co-occurrence between the terms, which pointed to the number of publications in which the terms occurred together. The higher the numerical value displayed, the stronger the link or the strength of the link between the terms or keywords.

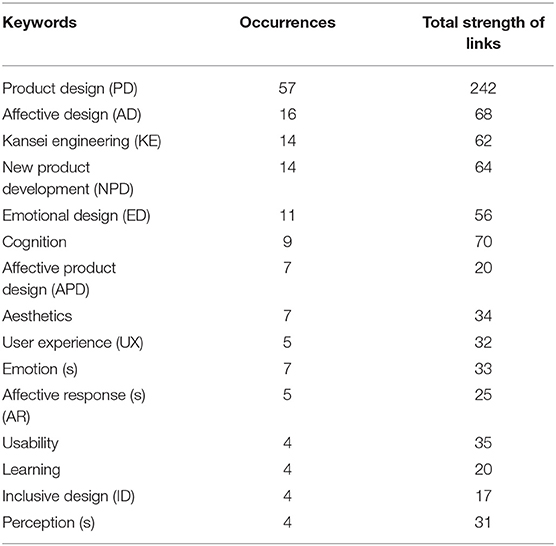

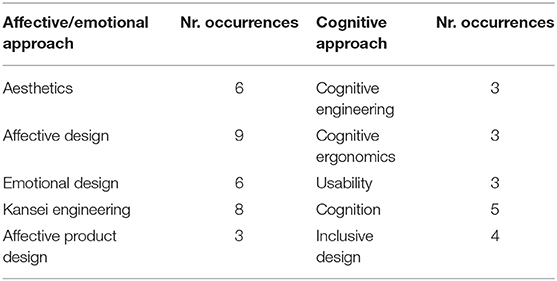

The articles containing the highlighted keywords (considered here with only four or more occurrences— Table 1 ) received the sum of the occurrences volume and the total strength of the links for each keyword. Subsequently, the sum of the volumes of each keyword was added to the value of their InOrdinatio, as shown in Equation (2):

With the application of Equation 2 as a determinant for the selection of articles, articles not considered in the initial qualitative verification (Equation 1) were included in the sample.

Table 1 . Terms or keywords with an occurrence equal to or greater than four.

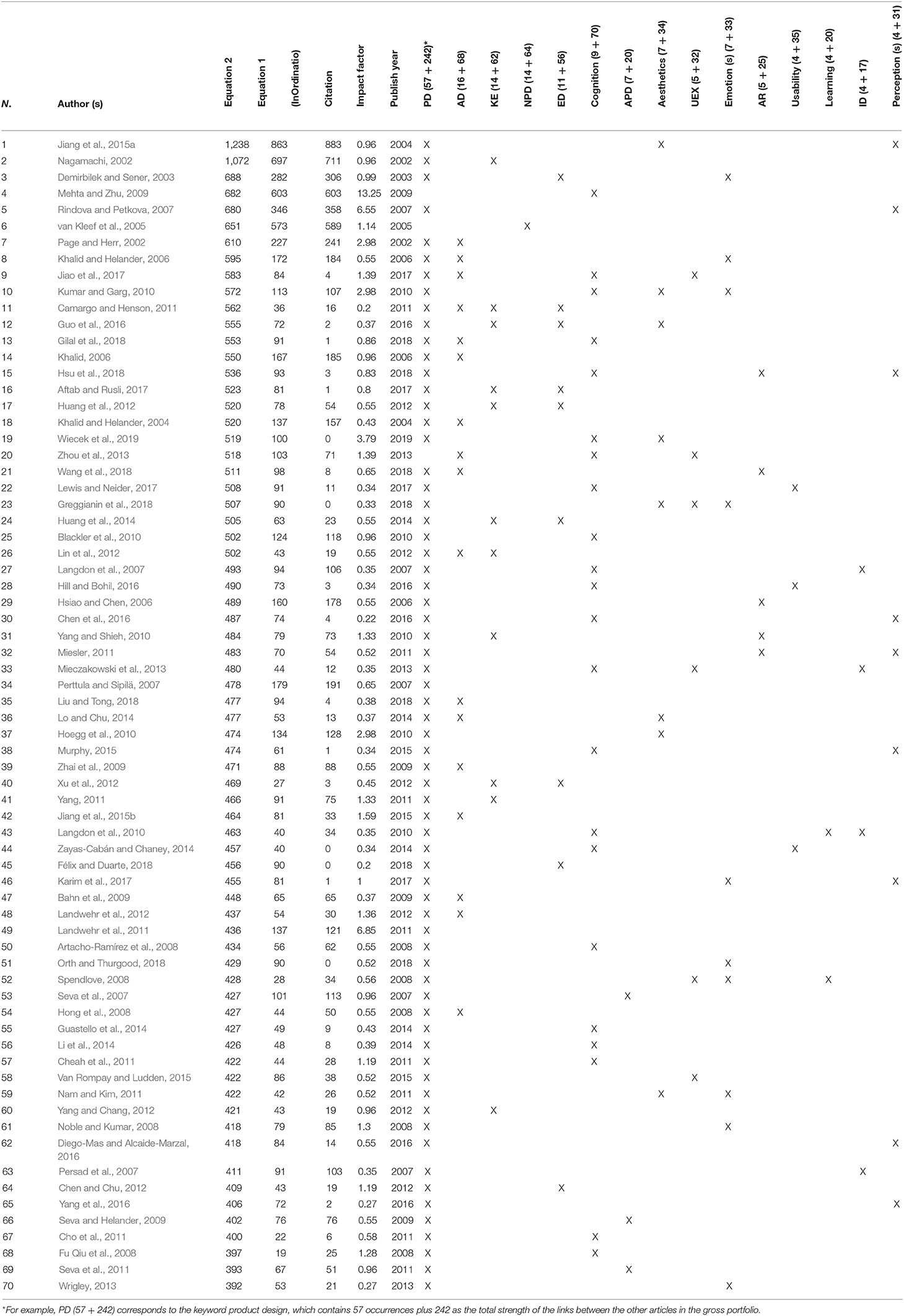

Table 2 shows the result of the SLR (70 articles). These articles compose the sample for the analysis and discussion of the results. It presents the main authors and topics covered highlighted in the research field. It is possible to verify the results of the qualitative synthesis (Equation 1) and the quantitative synthesis (Equation 2) in detail. The volume of citations and the impact factor of each paper, the year outlining the topicality of the subject, as well as the number of occurrences and strength of the links between the titles and the keywords of the research. The methodology used can be easily replicated in future research.

Table 2 . Classification of the final selection by relevance and impact in the research.

The applications occurred in two large areas, as shown in Table 3 . The detailed bibliometric analysis of the applications made it possible to organize the approaches in order of relevance: affective/emotional approach and cognitive approach.

Table 3 . Occurrence of affective/emotional and cognitive product approaches.

Cognitive and Affective Design Approach

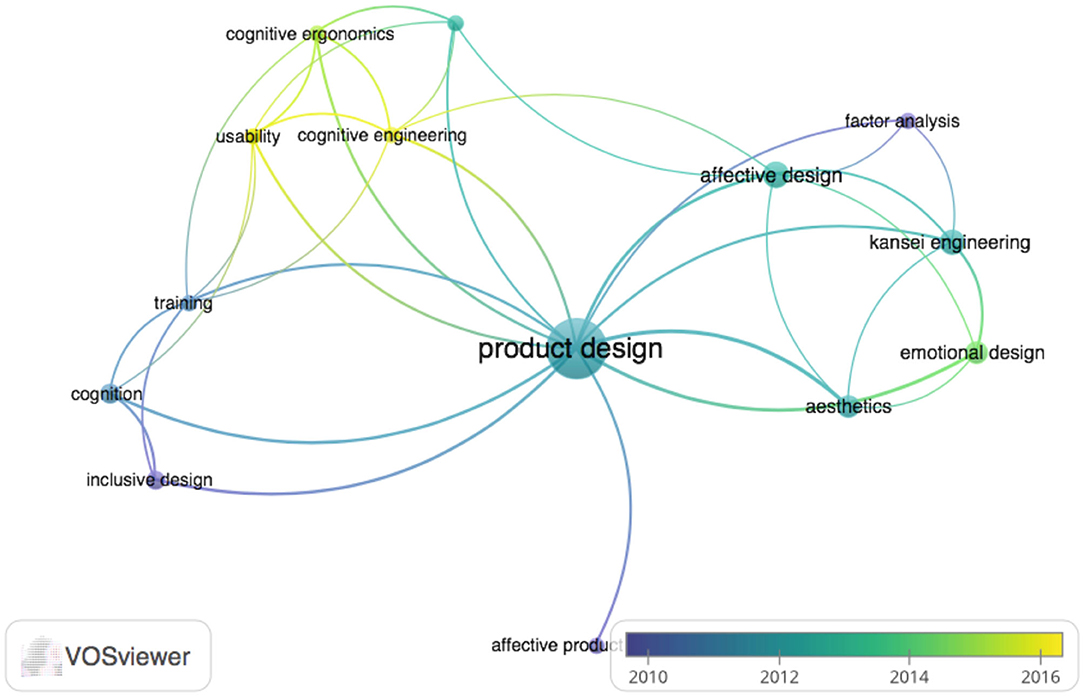

The networked view considers the overlapping data of information about the publication year and presents the timeliness of approaches. Figure 3 presents clusters of evident keywords in the articles. They are organized ranging from the “darkest” and oldest, to the “lightest” and most current, and show an important trend in the types of applications and topicality of the topics covered.

Figure 3 . Network view of the application areas, with information from the publication year overlapped.

Applications in “usability” ( Seva et al., 2011 ; Hill and Bohil, 2016 ), “cognitive ergonomics” ( Chang and Chen, 2016 ; Montewka et al., 2017 ), and “cognitive engineering” ( Li and Gunal, 2012 ) appear to be more current than applications in “affective design” ( Jiao et al., 2006 ; Lu and Petiot, 2014 ; Jiang et al., 2015a ), “kansei engineering” ( Nagamachi, 2002 ; Xu et al., 2012 ; Mele and Campana, 2018 ), and “emotional design” ( Guo et al., 2014 ). All cognitive and affective need applications are interconnected to the product design and indicate cognitive approaches more focused on product usability and functionality, while affective and emotional approaches are more focused on pleasure and consumption.

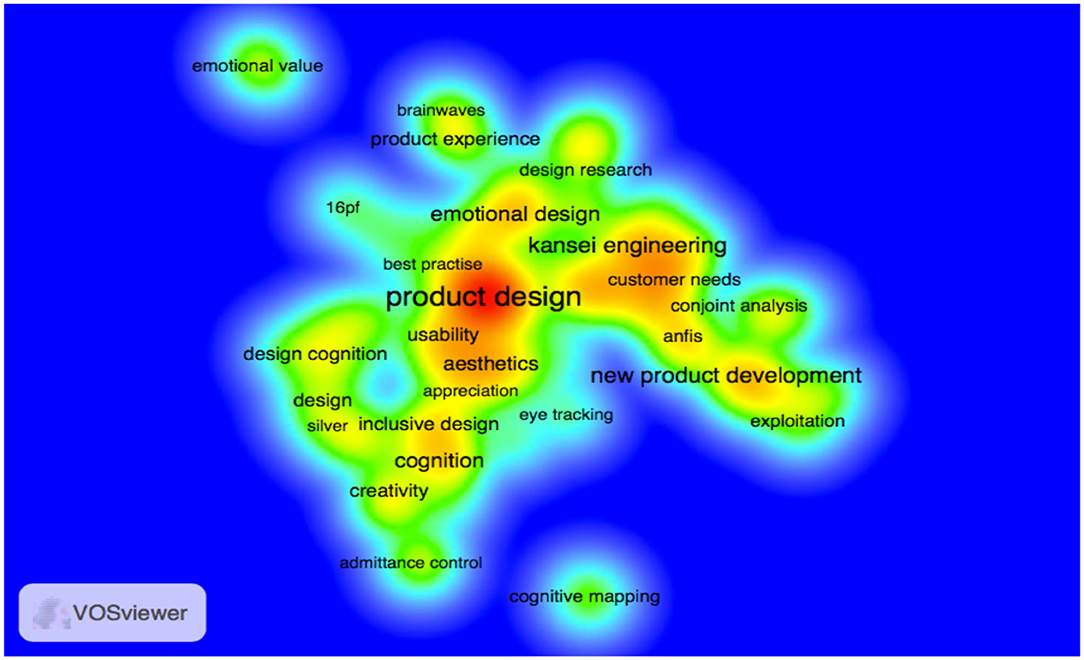

On one hand, there are approaches to ergonomics and cognitive engineering that direct them to usability and product quality ( Seva et al., 2011 ), as well as learning and training aspects ( Yang and Shieh, 2010 ; Hsu, 2017 ), or interaction design ( Langdon et al., 2007 ; Faiola and Matei, 2010 ; Nam and Kim, 2011 ; Mieczakowski et al., 2013 ). On the other hand, there are approaches that seek to meet the consumer's most affective and emotional needs and preferences and, thereby, improve quality of life. These approaches focus on the affective design ( Guo et al., 2016 ; Gilal et al., 2018 ) and emotional design ( Félix and Duarte, 2018 ). The kansei engineering (KE) method is featured among the affective approaches and seeks to evaluate and translate the consumer subjective requirements into product attributes, as shown in Figure 4 in the density view of terms or keywords. The greater the occurrence of the terms, the greater the size of the letters and the more intense the colors presented (for example, warm, red). In addition, the closer a word is to the other, the greater the link strength between the terms, which shows the intensity of research in different types of approaches.

Figure 4 . Visualization map of terms or keywords by density.

Cognitive Design

Among the most current approaches ( Figure 3 ), it is possible to mention the cognitive design application. Inclusive design ( Langdon et al., 2007 , 2010 ), education ( Faiola and Matei, 2010 ; Lu, 2017 ; Kiernan et al., 2019 ), and learning and creativity approaches ( Spendlove, 2008 ) are the most explored by researchers. They seek to evaluate and translate the product's usability and functionality attributes, making the interaction easier for the consumer, as for example when understanding the color effect (blue or red) on the performance of the user's cognitive tasks ( Mehta and Zhu, 2009 ). According to Murphy (2015) , there is an understanding that color should be used with a different code in the world of human-computer interactions, such as form or pattern fillings, in order to make the content accessible to everyone, including those with color vision deficits.

Some approaches aim to gather the perception of the consumer's image with the product form ( Lin et al., 2012 ; Chen et al., 2016 ). Others aim to investigate the “noise” influences on visual cognitive responses to the design of human-oriented products ( Cho et al., 2011 ).

There is strong evidence that a good design is important in the creation of products for intuitive use ( Blackler et al., 2010 ). This makes it possible to assist in the inclusive interaction design, through a better understanding of the cognitive representations or through processes of producing mental images of designers and users ( Mieczakowski et al., 2013 ). Inclusive design is relevant by differentiating the effects of easy-to-use consumer products from those difficult to use ( Langdon et al., 2007 ). These data corroborate the growing demographic demand of an increasingly aging population, which should be included in product design ( Lewis and Neider, 2017 ).

In many approaches, the cognitive application mixes with the affective application ( Hsu et al., 2018 ), as there is still no clear or deeper explanation about the separation between the psychological functions and processes involved in the subjective experience of interaction between the consumer and the product ( Khalid and Helander, 2004 ; Zhou et al., 2013 ). This problem is considered the true “black box” of content or substance knowledge that composes the internal and subjective processes of the functioning of cognitive and affective systems.

Affective/Emotional Design

The approaches on affective/emotional product design are quite varied ( Kumar Ranganathan et al., 2013 ). The affective and emotional satisfaction are objectives of most approaches on affective product design ( Chan et al., 2018 ). These ones mix with emotional approaches and are synonymous in most applications. According to Chen and Chu (2012) , consumers often make their purchasing decisions based on the product price, quality, and functionality. However, in many situations the perceived value influences the decision, which is always subjective and motivated by emotions. It is important to predict the perceived value of design alternatives based on the common language that target consumers and designers understand.

Other approaches seek to measure affective responses to consumer-oriented product design ( Camargo and Henson, 2011 ). There are also approaches that measure the responses to the affective aspects applied to product design in order to improve the consumer's affective satisfaction ( Hong et al., 2008 ; Zhai et al., 2009 ). Still others measure the reactions of the effects of product attributes on personal interactions, for which Lo and Chu (2014) propose a concept of socio-affective product design. The focus of affective approaches is always the consumer, their desires, personal interaction, quality of life, and satisfaction.

In relation to affective design, one of the most important tasks is to evoke specific affective responses through the manipulation of product form ( Yang and Shieh, 2010 ; Yang, 2011 ; Diego-Mas and Alcaide-Marzal, 2016 ). The main objective of these approaches is to provoke positive affective and emotional responses in the consumer. Hsiao and Chen (2006) investigate the structure of the relationship between the product forms and consumer's affective responses. The product shape is increasingly important to provoke affective responses. By applying an evolutionary approach, Miesler (2011) examines affective responses in relation to facial features. When combining facial electromyography with assessments of a “baby's facial shapes” in order to assess innate emotional responses in the consumer, he discovered that, in this case, the participants presented more positive and affective responses. The results confirm that the resources acquired in an evolutionary manner affect the consumer's affective responses to the products' visual forms.

The emotional design and related approaches meet the vision of designers and manufacturers who understand consumption as the main objective of a product. They seek to generate and add value to the product through emotional design, trying to find a lasting connection between the product and consumer ( Aftab and Rusli, 2017 ). The inclusion of aesthetic and functional attributes causes positive emotional experiences ( Seva and Helander, 2009 ), which provide pleasantness and pleasure to the consumer, for example, in bra design ( Greggianin et al., 2018 ).

Digital technology is also presented to apply to the consumer's emotional aspects in product engineering and design. In relation to the digital world, Nam and Kim (2011) seek to help designers to create meaningful products for the digital world while preserving the technology benefits. There is a great opportunity for design to increase the extra experiential value of products in a world with digital technologies. The approaches aim to add value to the product through important emotional attributes for the consumer. Sophisticated applications with smart neural networks and optimization methods are also used to meet emotional needs ( Guo et al., 2016 ) and increase the consumer's quality of life ( Félix and Duarte, 2018 ).

In summary, measuring and evaluating affective and emotional responses and projecting design elements or attributes ( Camargo and Henson, 2011 ), attributes that provoke essentially positive affective and emotional reactions, are the focus of most approaches for a product's affective/emotional design.

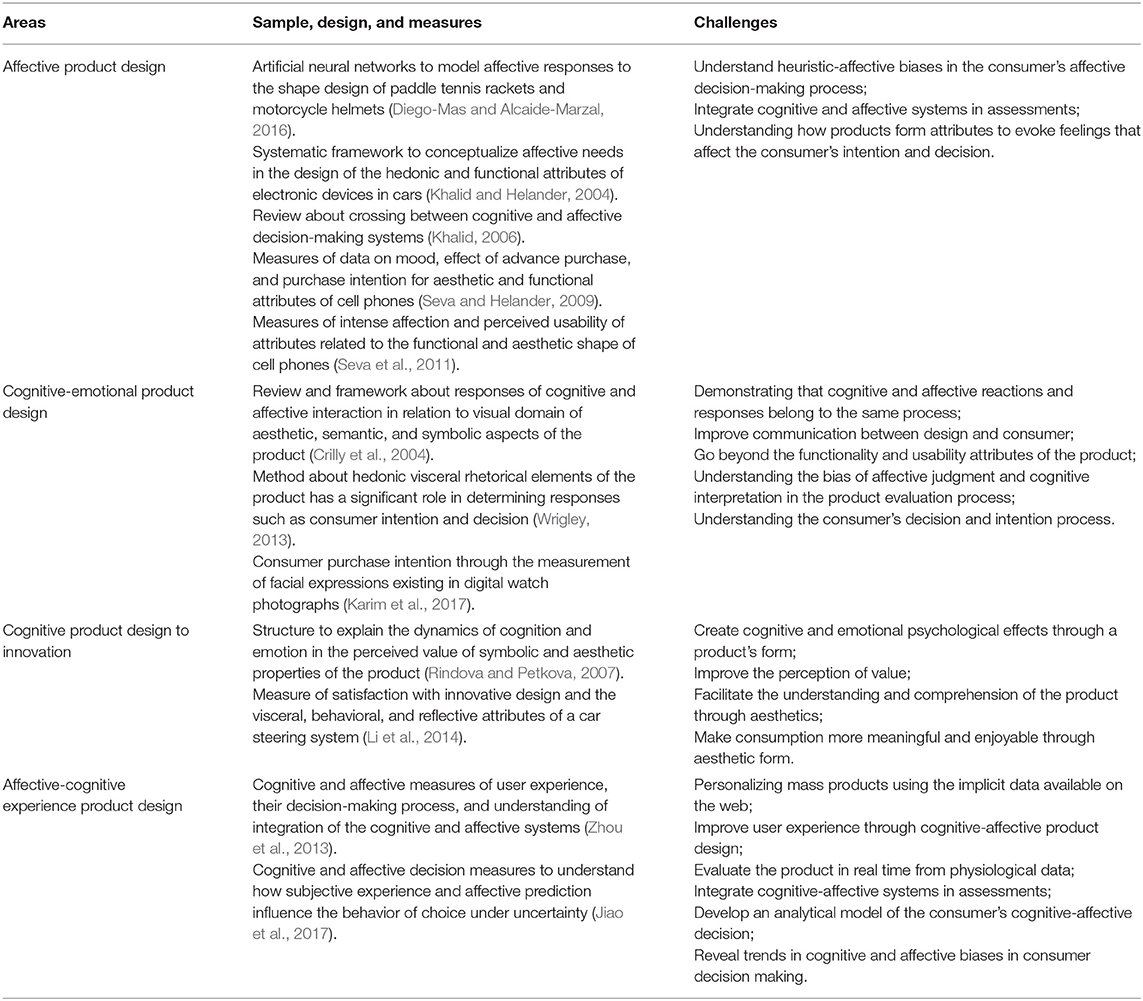

Analysis and Discussion

Different areas of product design seek to understand the relationship between product and consumer. Affective product design explores the most affective aspects between the product and consumer, as proposed by Khalid and Helander (2004) , Khalid (2006) , Khalid and Helander (2006) , Seva and Helander (2009) , Seva et al. (2011) , and Diego-Mas and Alcaide-Marzal (2016) . Cognitive-emotional product design proposes a more sentimental, visceral, and hedonic approach, as suggested by Crilly et al. (2004) , Wrigley (2013) , and Karim et al. (2017) . Other approaches (e.g., Rindova and Petkova, 2007 ; Artacho-Ramírez et al., 2008 ; Li et al., 2014 ) mix innovation elements and cognitive and emotional aspects in the cognitive design. There is also the design approach of affective-cognitive experience product design with user's experience bias (e.g., Zhou et al., 2013 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ). These studies share common challenges, such as the complexity of understanding and evaluating the consumers' subjective cognitive and affective needs ( Table 4 ), or understanding the interaction experience between the product and consumer, or even the product experience ( Schifferstein and Hekker, 2011 ).

Table 4 . Challenges in applications of consumer's cognitive and affective needs in product design.

The main challenges in applications define the current state of cognitive and affective approaches to product design.

State of the Art of Applying Consumer's Cognitive and Affective Needs in Product Design

For Wrigley (2013) , 80% of an individual's life is consumed by their emotions, while the other 20% is controlled by their intellect. Emotions directly influence a variety of cognitive responses, and research on emotional effects on consumer choice is an important field which is little studied by designers and developers ( Hirschman and Stern, 1999 ). At this point the state of the art is structured, where the status of applications and common challenges are summarized and presented in five stages that integrate a cognitive and affective product design cycle as illustrated in Figure 5 .

Figure 5 . State of the art of applying consumer's cognitive and affective needs in product design.

In the first stage ( Figure 5 —Detail 1), most applications' cognitive and affective needs in product design take place in the context of experience between the product and the consumer ( Kumar and Garg, 2010 ; Zhou et al., 2013 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Hsu et al., 2018 ). Product input attributes can be perceived sensibly as “positive” or “negative.” In the initial communication stage, rational preferences, analytical, intuitive, and experimental (beliefs, memories, and others) should be encouraged by the product attributes that can be functional, cognitive, hedonic, or affective ( Blackler et al., 2010 ; Wrigley, 2013 ).

In the second stage ( Figure 5 —Detail 2), the functional and hedonic attributes of the product are processed by the “cognitive and affective systems” of the consumer on a single integrated mental process ( Khalid and Helander, 2004 , 2006 ; Khalid, 2006 ). This is understood by most researchers as a “black box” complex and a difficult to understand assessment ( Zhou et al., 2013 ; Diego-Mas and Alcaide-Marzal, 2016 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ). At this point, what happens is the subjective product experience, in which the bias is not known. However, the systems link different weights and measures which account for the decision-making process ( Kahneman and Tversky, 1979 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ). The emotional system is higher (80%) compared to the cognitive system (20%) ( Wrigley, 2013 ). The result of subjective product experience can be expressed in intentions ( Giese et al., 2014 ; Yang et al., 2016 ; Wang et al., 2018 ), quality judgments ( Page and Herr, 2002 ; Hsu, 2017 ), decisions ( Dogu and Albayrak, 2018 ), opinions, and attitudes. The expressions shown in the third step ( Figure 5 —Detail 3) represent the reactions and cognitive and affective responses (positive and negative outputs) and are intended by the design team and product engineering to result in response requirements of subjective product experience ( Figure 5 —Detail 4).

The outputs are understood as necessary entry requirements for the fourth stage ( Figure 5 —Detail 4). The requirement can be a cognitive response, functional ( Khalid and Helander, 2004 ; Rindova and Petkova, 2007 ; Seva et al., 2011 ; Homburg et al., 2015 ), aesthetic ( Artacho-Ramírez et al., 2008 ; Kumar and Garg, 2010 ; Carbon and Jakesch, 2013 ; Greggianin et al., 2018 ; Wiecek et al., 2019 ), symbolic semantics ( Demirbilek and Sener, 2003 ; Crilly et al., 2004 ; Rindova and Petkova, 2007 ; Artacho-Ramírez et al., 2008 ; Setchi and Asikhia, 2019 ), usability ( Seva et al., 2011 ; Li and Gunal, 2012 ), emotional ( Demirbilek and Sener, 2003 ; Kumar and Garg, 2010 ), visceral ( Wrigley, 2013 ; Aftab and Rusli, 2017 ), and others. At this time, these requirements must be evaluated and translated by engineering and product design teams ( Li et al., 2014 ).

Finally, in the fifth step ( Figure 5 —Detail 5), the product design teams must evaluate the consumer response requirements through models, methods, and tools for evaluation and translation such as kansei engineering, quality function deployment, among others ( Huang et al., 2012 ; Li et al., 2014 ; Yuen, 2014 ; Shen and Wang, 2016 ).

Figure 5 provides designers with reasonable guidelines for comprehensively capturing, evaluating, and translating customer requirements. In this sense, it seeks to convert subjective consumer information into product design demands and processes and select the technical requirements for functional, usability, hedonic, and holistic improvements in the product. The product is then designed and developed in a targeted way for the cognitive and affective subjective satisfaction of consumers, helping designers in search of “cognitive” and “affective” solutions for the product. At this point, the product design application cycle, usually oriented toward the consumer, starts again in a cyclical manner.

Advances in Neuroscience

Neuroscience addresses the importance of multidisciplinary knowledge in order to understand the opinions and consumer responses to cognitive and affective product design. Can a model potentially influence decision processes including price, choice strategy, context, experience, and memory; and also provide new insights into individual differences in consumer behavior and brand preferences? The fundamental question, still little evidenced, is how to apply these neuroscience advances in product design, making the product more accessible, more comfortable, and more enjoyable to use and consume.

According to Maturana and Varela (1987) , if the goal is to understand any human activity, then it is necessary to consider the emotion that defines the field of action in which this activity takes place and in the process, learn to observe what actions the emotion you want. Intentions start from the subjective, emotional, and affective internal processes that are expressed. It is essential to understand in-depth the phenomenon of subjective experience. Wrigley (2011 , 2013) attested that the response elements of “emotional cognition” are not presented as objective qualities of a product. However, these elements are a cognitive interpretation of the qualities of an object, driven both by the perception of real stimuli and by facts evoked by the consumer's memory and emotion. It affects the facial muscles and the musculoskeletal structure, also the visceral and internal environment of the body as well as the neurochemical responses in the brain and are part of how emotions modify the internal state of the body. Damasio (2001) described it similarly as in their exploration noted that the instinctive, visceral, and immediate response to sensory information strongly influenced the secondary information acquired when cognitive-behavioral interaction and reflection occurred later. There is a hierarchy of internal processes in operation, for although the affection and cognition are, to some extent, different neuroanatomically systems, they are deeply interconnected, influencing each other ( Ashby et al., 1999 ; Crilly et al., 2004 ; Norman, 2004 ).

Traditional assessment methods rarely present a complete understanding of user's cognitive and affective experience evoked by the product, which plays a decisive role in intention and purchase decision. Regarding product design, Ding et al. (2016) present a method of accurate measurement of user perception during product experience. The results of the application revealed a neural mechanism in the initial stage of the consumer experience, allowing for an accurate analysis of the time course of neural events when the behavioral intention is forming. Such advances can provide a basis for discovering the cognition and decision process when users perceive product design, and even provide help for the designer to hold the user's attention. Modica et al. (2018) stated that evaluation of a product considers the simultaneous cerebral and emotional evaluation of different qualities of the product, all belonging to the product experience. They investigate reactions by electroencephalographic (EEG) of the influence of brand, familiarity, and hedonic value, and results show more significant mental effort during an interaction with foreign products which demonstrates the importance of the perceived ease of a product. Also, concerning the use of neurophysiological and traditional measures to evaluate the responses of the participants through an EEG index (EEG), Martinez-Levy et al. (2017) pointed out that the change in EEG frontal cortical asymmetry is related to the general appraisal perceived during an observation of a charity campaign focusing on gender differences. Results show higher values for women than men for neurophysiological indices. Therefore, the declared taste of women is statistically significantly higher than the declared taste of men. Results suggest the presence of gender differences in cognitive and emotional responses to charity ads with emotional appeal. By providing a new way of establishing mappings between cognitive processes and traditional marketing data, Venkatraman et al. (2012) point out that a better understanding of neural decision-making mechanisms will increase the ability of marketers to market their products more effectively.

Neuroscience applied to the product market and psychology has brought significant advances in the last 20 years to the understanding that cognitive and emotional aspects generate greater consumer involvement. The objective is to further reduce the gap between product and consumer. New insights into individual differences in consumption behavior and specific preferences are presented. It also contributes to advances in the area of cognitive and affective product design, however still firmly positioned in areas of marketing and psychology.

Research Gaps in Literature

Cognitive design approaches have been proven to be a less discussed topic by the leading authors in the field, while affective/emotional design approaches are the most applied. The reason for this is that cognitive design is more associated with the product functionality and usability, the focus on ergonomics and systems engineering, in addition to interfaces and systems aimed at product use and not necessarily at consumption. Therefore, cognitive design approaches are slightly different from affective/emotional design approaches. These are more oriented to the design, form, and impact of the product attributes on the consumer's feelings and emotions. This way, they are mainly directed to product pleasure and pleasantness.

The areas of product design, engineering, and ergonomics are mixed in applications that focused on product design and on how functional and “cognitive” attributes, as well as hedonic and “affective” ones, affects the consumer's reactions and responses. The results of the SLR indicate that researchers paid predominant attention to areas of how cognitive and affective aspects can be applied in product design, and concentrated at the beginning of the PD and NPD cycle, that is, when evaluating and translating the consumer's reactions and responses when using or consuming the product.

In short, cognitive approaches are more up-to-date and associated with technology, and are therefore aimed at the ease and friendliness of the product. In contrast, affective approaches are older and aimed at quality of life, satisfaction, pleasure, and the pleasantness of the product. Due to the complexity of understanding the affective and emotional subjectivity of the consumer, and in how to translate these requirements into product attributes, these approaches seem to lose their preference in the areas of design and engineering for cognitive applications.

Some approaches identify the importance of an integrated application framework that considers all consumer's cognitive and affective aspects. However, they do not deepen the study on the intrinsic phenomenon of the subjective experience resulting from cognitive and affective systems, inherent to “mental” processes, which opens an essential gap for research ( Khalid and Helander, 2006 ; Zhou et al., 2013 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ). The trends point to the need to decipher the complexity of the “black box” of human subjectivity and, thus, influence consumer behavior.

Future Directions and Research

The main trends in the research field refer to: (i) studies on the consumer's sensory, cognitive, and affective perception ( Wrigley, 2013 ) concerning the product's functional and hedonic attributes and characteristics ( Khalid and Helander, 2004 , 2006 ); (ii) studies on the consumer's subjective cognitive and affective experience about the product ( Jiao et al., 2017 ); and (iii) studies on capturing, measuring, and translating consumers' cognitive and affective responses and opinions ( Crilly et al., 2004 ; Hsu et al., 2018 ).

Therefore, from the individual approaches in each article, it is possible to observe the researchers' acceptance that the consumer's subjective experience begins through sensory and cognitive perception. When it is perceiving and processing the inputs from the product (functional and hedonic characteristics and attributes, for example); then, by the psychological processing of the cognitive (slow) and affective (fast) systems ( Kahneman and Tversky, 1979 ; Kahneman, 2011 ) it brings memories of previous experiences, beliefs, images, and emotions; and finally ends with responses and opinions, with cognitive and affective elements ( Crilly et al., 2004 ; Khalid and Helander, 2004 ; Kumar Ranganathan et al., 2013 ; Zhou et al., 2013 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ; Hsu et al., 2018 ).

Among the topics and questions to be considered in future research, we suggest: what are the psychological relationships between the cognitive and affective needs of the consumer in the use or consumption of products? What characteristics and attributes of the product have a positive cognitive and affective impact on the consumer? Through product design and new products, is it possible to produce pleasure and happiness in the consumer's mind? Can an inclusive product design facilitate use in populations with increasing cognitive difficulties? Can we develop better predictive models to anticipate the consumer's intention and decision when choosing products?

Conclusions

The aim of this study was to investigate the cognitive and affective needs of the consumer applied to product design through a systematic literature review of the literature published in the last 20 years. In this regard, this article selected the main research carried out in the field of cognitive and affective product design and identified the main approaches, challenges, and trends in applications.

Among the different approaches analyzed, there were research fields that seek to understand the consumer's behavior, emotions, affections, and reflections on the product. Cognitive and affective product design follows this path and seeks to narrow the space between the product and the consuming public. However, cognitive approaches were less discussed than affective ones. The possibility of cognitive design was more associated with the product's functionality and usability, interfaces, and systems—usually the focus of ergonomics and systems engineering—and not necessarily consumption, which was clearly the focus of affective design and marketing. The areas of product design, engineering, and ergonomics mix with applications that focus their efforts on how functional and “more cognitive” attributes and characteristics, as well as hedonic and “more affective” attributes and characteristics, affect the consumer's reactions and responses. They indicate that applications that are both cognitive and affective open an important path for future research on consumer-oriented product design. The goal is always to improve the interaction or the consumption experience by facilitating the information flow, thus improving communication between consumer and product, positively affecting them.

As a synthesis for the approaches, it is possible to conclude that applications in “usability,” “cognitive ergonomics,” and “cognitive engineering” are more current than applications in “affective design,” “kansei engineering,” and “emotional design.” All the applications analyzed are interconnected to product design and indicate that cognitive approaches are more focused on product usability and functionality, while the affective/emotional approaches are more focused on pleasure and consumption. These characteristics are important for the consumer study, as it applies to product design that is still in the conceptualization phase, exactly where the approaches are oriented to the evaluation and translation of the consumer's subjective responses.

In short, cognitive approaches are more up-to-date and associated with technology, therefore aimed at the ease and friendliness of the product. While affective approaches are older and aimed at quality of life, satisfaction, pleasure, and the pleasantness of the product. This review indicates that this shift in focus from the affective to the cognitive is due to the complexity of understanding the affective and emotional subjectivity of the consumer and how to translate these requirements into product attributes, these approaches seem to lose their preference in the areas of design and engineering for more rational and logical cognitive applications, making them therefore more statistically verifiable.

Finally, this study recommends that, in future research, the objective should be to create analytical methods and tools ( Zhou et al., 2013 ; Jiao et al., 2017 ), with multidisciplinary approaches ( Jiang et al., 2015a ; Chan et al., 2018 ) from different areas of consumer study such as engineering and design ( Jiang et al., 2015b ; Shen and Wang, 2016 ), marketing ( Seva et al., 2007 ; Bloch, 2011 ; Mu, 2015 ), neuroscience, and cognitive sciences ( Damasio and Adolphs, 2001 ; Turner and Laird, 2012 ), while seeking to evaluate and translate the consumer's subjective experience into product elements and attributes. The objective is to improve the relationship between the consumer and the product, making it lighter and with a better information flow.

We conclude that it is necessary that approaches to cognitive and affective product design be incorporated into research about the consumer, so that no need, be it more functional and cognitive or more pleasurable and affective, is left unattended. Thus, it will be possible to bring the consumer closer to the product, meeting their subjective needs, and to open the “black box” of subjective experience that only the consumer themselves have access to. In this way, it will become possible to meet the cognitive and affective needs of the consumer and produce happiness in their mind, something essentially subjective and understood as difficult to evaluate and translate. The cognitive design must be mixed with affective design, as in a high-tech world, the product's facilities and usability are producing affective pleasure in the consumer through the economy of cognitive effort.

Research Limitations

There are limitations to this research. The next step in the research should focus on finding new methods and models for evaluating and translating the cognitive and affective product experience, with combined psychological and physiological measures, according to what Zhou et al. (2013) previously suggested. The present study only focused on two dimensions of cognitive and affective product design: the cognitive and affective/emotional attributes and characteristics. However, the authors suggest that the symbolic dimension presents significant differences when compared to the cognitive and affective aspects, following the studies carried out by Bloch (2011) , Kumar Ranganathan et al. (2013) , and Homburg et al. (2015) .

The path of opportunities lies in multidisciplinary approaches that consider neuroscience and cognitive sciences, together with cognitive and affective product design, as well as their current understandings on the themes highlighted in this research. The deepening of these questions is a limitation of this research. The authors understand the need to continue research on analytical methods and models capable of improving the understanding of the affective and cognitive decision-making process regarding product design. New analytical tools must be oriented toward the consumer and their subjective experiences. These can translate opinions and responses from the “black box” or the subjective experience of the product.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This research was financially supported by the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personal (CAPES), the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq), and Pontifical Catholic University of Parana (PUCPR).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the Industrial and Systems Engineering Graduate Program at Pontifical Catholic University of Parana (PPGEPS/PUCPR), the Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personal (CAPES), and the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for their financial support of this research.

Aftab, M., and Rusli, H. A. (2017). Designing visceral, behavioural and reflective products. Chin. J. Mech. Eng . 30, 1058–1068. doi: 10.1007/s10033-017-0161-x

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Artacho-Ramírez, M. A., Diego-Mas, J. A., and Alcaide-Marzal, J. (2008). Influence of the mode of graphical representation on the perception of product aesthetic and emotional features: an exploratory study. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 38, 942–952. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2008.02.020

Ashby, F. G., Isen, A. M., and Turken, U. (1999). A neuropsychological theory of positive affect and its influence on cognition. Am. Psychol. Assoc. 106, 529–550.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Bahn, S., Lee, C., Nam, C. S., and Yun, M. H. (2009). Incorporating affective customer needs for luxuriousness into product design attributes. Hum. Fact. Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Industr . 19, 105–127. doi: 10.1002/hfm.20140

Blackler, A., Popovic, V., and Mahar, D. (2010). Investigating users' intuitive interaction with complex artefacts. Appl. Ergon . 41, 72–92. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.04.010

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bloch, P. H. (2011). Product design and marketing: reflections after fifteen years. Product Innovat. Manage. 28, 378–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5885.2011.00805.x

CrossRef Full Text

Camargo, F. R., and Henson, B. (2011). Measuring affective responses for human-oriented product design using the Rasch model. J. Des. Res . 9, 360–375. doi: 10.1504/JDR.2011.043363

Carbon, C., and Jakesch, M. (2013). A model for haptic aesthetic processing and its implications for design. Proc. IEEE 101, 2123–2133. doi: 10.1109/JPROC.2012.2219831

Chan, K. Y., Kwong, C. K., Wongthongtham, P., Jiang, H., Fung, C. K. Y., Abu-Salih, B., et al. (2018). Affective design using machine learning: a survey and its prospect of conjoining big data. Int. J. Comput. Integr. Manuf . 33, 1–19. doi: 10.1080/0951192X.2018.1526412

Chang, Y.-M., and Chen, C.-W. (2016). Kansei assessment of the constituent elements and the overall interrelations in car steering wheel design. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 56, 97–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2016.09.010

Cheah, W. P., Kim, Y. S., Kim, K.-Y., and Yang, H.-J. (2011). Systematic causal knowledge acquisition using FCM constructor for product design decision support. Expert Syst. Appl . 38, 15316–15331. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2011.06.032

Chen, H.-Y., Chang, Y.-M., and Chang, H.-C. (2016). A numerical definition-based systematic design approach for coupling consumers' image perception with product form. J. Eng. Des. Technol . 14, 134–159. doi: 10.1108/JEDT-11-2013-0075

Chen, L.-C., and Chu, P.-Y. (2012). Developing the index for product design communication and evaluation from emotional perspectives. Expert Syst. Appl . 39, 2011–2020. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2011.08.039

Cho, W., Hwang, S.-H., and Choi, H. (2011). An investigation of the influences of noise on EEG power bands and visual cognitive responses for human-oriented product design. J. Mech. Sci. Technol . 25, 821–826. doi: 10.1007/s12206-011-0128-2

Coates, D. (2003). Watches Tell More Than Time: Product Design, Information and the Quest for Elegance . London: McGraw-Hill.

Crilly, N., Moultrie, J., and Clarkson, P. J. (2004). Seeing things: consumer response to the visual domain in product design. Des. Stud . 25, 547–577. doi: 10.1016/j.destud.2004.03.001

Damasio, A. (2001). “Some notes on brain, imagination and creativity,” in The Origins of Creativity , eds K. H. Pfenninger and V. R. Shibik (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 59–68.

Damasio, A., and Adolphs, R. (2001). “The interaction of affect and cognition: a neurobiological perspective,” in Handbook of Affect and Social Cognition , ed J. P. Forgas (Abingdon: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers), 27–49.

Google Scholar

Demirbilek, O., and Sener, B. (2003). Product design, semantics and emotional response. Ergonomics 46, 1346–1360. doi: 10.1080/00140130310001610874

Desmet, P. (2003). A multilayered model of product emotions. Des. J . 6, 4–13. doi: 10.2752/146069203789355480

Diego-Mas, J. A., and Alcaide-Marzal, J. (2016). Single users' affective responses models for product form design. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 53, 102–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2015.11.005

Ding, Y., Guo, F., Zhang, X., Qu, Q., and Liu, W. (2016). Using event related potentials to identify a user's behavioural intention aroused by product form design. Appl. Ergon . 55, 117–123. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2016.01.018

Dogu, E., and Albayrak, Y. E. (2018). Criteria evaluation for pricing decisions in strategic marketing management using an intuitionistic cognitive map approach. Soft Comput . 22, 4989–5005. doi: 10.1007/s00500-018-3219-5

Ellsworth, P. C., and Scherer, K. R. (2003). "Appraisal processes in emotion,” in Series in Affective Science. Handbook of Affective Sciences , eds R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, and H. H. Goldsmith (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 572–595.

Faiola, A., and Matei, S. A. (2010). Enhancing human–computer interaction design education: Teaching affordance design for emerging mobile devices. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ . 20, 239–254. doi: 10.1007/s10798-008-9082-4

Félix, M. J., and Duarte, V. (2018). Design and development of a sustainable lunch box, which aims to contribute to a better quality of life. Int. J. Qual. Res. 12, 869–884. doi: 10.18421/ijqr12.04-06

Frijda, N. H. (1986). The Emotions—Studies in Emotion and Social Interaction . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fu Qiu, Y., Ping Chui, Y., and Helander, M. G. (2008). Cognitive understanding of knowledge processing and modeling in design. J. Knowl. Manage . 12, 156–168. doi: 10.1108/13673270810859587

Giese, J. L., Malkewitz, K., Orth, U. R., and Henderson, P. W. (2014). Advancing the aesthetic middle principle: trade-offs in design attractiveness and strength. J. Bus. Res . 67, 1154–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.05.018

Gilal, N. G., Zhang, J., and Gilal, F. G. (2018). The four-factor model of product design: scale development and validation. J. Prod. Brand Manage . 27, 684–700. doi: 10.1108/JPBM-11-2017-1659

Gómez-Corona, C., Chollet, S., Escalona-Buendía, H. B., and Valentin, D. (2017). Measuring the drinking experience of beer in real context situations. The impact of affects, senses, and cognition. Food Qual. Pref. 60, 113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2017.04.002

González-Sánchez, J.-L., and Gil-Iranzo, R.-M. (2013). Hedonic and multicultural factors in product design that improve the user experience. El Profesional de la Información 22, 26–35. doi: 10.3145/epi.2013.ene.04

Green, W., and Jordan, P. W. (eds.), (1999). Human factors in product design: current practice and future trends. CRC Press , Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis Group.

Greggianin, M., Tonetto, L. M., and Brust-Renck, P. (2018). Aesthetic and functional bra attributes as emotional triggers. Fashion Textiles 5:31. doi: 10.1186/s40691-018-0150-4

Guastello, A. D., Guastello, S. J., and Guastello, D. D. (2014). Personality trait theory and multitasking performance: Implications for ergonomic design. Theor Issues Ergono. Sci . 15, 432–450. doi: 10.1080/1463922X.2012.762063

Guo, F., Liu, W. L., Liu, F. T., Wang, H., and Wang, T. B. (2014). Emotional design method of product presented in multi-dimensional variables based on Kansei Engineering. J. Eng. Design 25, 194–212. doi: 10.1080/09544828.2014.944488

Guo, F., Qu, Q.-X., Chen, P., Ding, Y., and Liu, W. L. (2016). Application of evolutionary neural networks on optimization design of mobile phone based on user's emotional needs. Hum. Fact. Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Industr . 26, 301–315. doi: 10.1002/hfm.20628

Hauser, J. R., and Clausing, D. (1988). The house of quality. Harv. Bus. Rev . 66, 63–73.

Hill, A. P., and Bohil, C. J. (2016). Applications of optical neuroimaging in usability research. Ergon. Des . 24, 4–9. doi: 10.1177/1064804616629309

Hirschman, E., and Stern, B. (1999). The roles of emotion in consumer research. Adv. Cons. Res . 26, 4–11.

Hoegg, J., Alba, J. W., and Dahl, D. W. (2010). The good, the bad, and the ugly: influence of aesthetics on product feature judgments. J. Cons. Psychol . 20, 419–430. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2010.07.002

Homburg, C., Schwemmle, M., and Kuehnl, C. (2015). New product design: concept, measurement, and consequences. J. Mark . 79, 41–56. doi: 10.1509/jm.14.0199

Hong, S. W., Han, S. H., and Kim, K.-J. (2008). Optimal balancing of multiple affective satisfaction dimensions: a case study on mobile phones. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 38, 272–279. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2007.09.002

Hsiao, K.-A., and Chen, L.-L. (2006). Fundamental dimensions of affective responses to product shapes. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 36, 553–564. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2005.11.009

Hsu, C.-L., Chen, Y.-C., Yang, T.-N., Lin, W.-K., and Liu, Y.-H. (2018). Does product design matter? Exploring its influences in consumers' psychological responses and brand loyalty. Inform. Technol. People 31, 886–907. doi: 10.1108/ITP-07-2017-0206

Hsu, W.-Y. (2017). An integrated-mental brainwave system for analyses and judgments of consumer preference. Telematics Informatics 34, 518–526. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2016.11.002

Huang, Y., Chen, C.-H., and Khoo, L. P. (2012). Kansei clustering for emotional design using a combined design structure matrix. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 42, 416–427. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2012.05.003

Huang, Y., Chen, C.-H., Wang, I.-H., and Khoo, L. P. (2014). A product configuration analysis method for emotional design using a personal construct theory. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 44, 120–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2013.11.005

Jesson, J., and Lacey, F. (2006). How to do (or not to do) a critical literature review. Pharmacy Educ . 6, 139–148. doi: 10.1080/15602210600616218

Jiang, H., Kwong, C. K., Liu, Y., and Ip, W. H. (2015a). A methodology of integrating affective design with defining engineering specifications for product design. Int. J. Product. Res . 53, 2472–2488. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2014.975372

Jiang, H., Kwong, C. K., Siu, K. W. M., and Liu, Y. (2015b). Rough set and PSO-based ANFIS approaches to modeling customer satisfaction for affective product design. Adv. Eng. Inform . 29, 727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.aei.2015.07.005

Jiao, R. J., Zhang, Y., and Helander, M. (2006). A Kansei mining system for affective design. Expert Syst. Appl . 30, 658–673. doi: 10.1016/j.eswa.2005.07.020

Jiao, R. J., Zhou, F., and Chu, C.-H. (2017). Decision theoretic modeling of affective and cognitive needs for product experience engineering: key issues and a conceptual framework. J. Intell. Manuf . 28, 1755–1767. doi: 10.1007/s10845-016-1240-z

Jordan, P. W. (1998). Human factors for pleasure in product use. Appl. Ergon . 29, 25–33.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking Fast and Slow . New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, D., and Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica 47, 313–327.

Karim, A. A., Lützenkirchen, B., Khedr, E., and Khalil, R. (2017). Why is 10 past 10 the default setting for clocks and watches in advertisements? A psychological experiment. Front. Psychol . 8:1410. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01410

Khalid, H. M. (2006). Embracing diversity in user needs for affective design. Appl. Ergon . 37, 409–418. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2006.04.005

Khalid, H. M., and Helander, M. G. (2004). A framework for affective customer needs in product design. Theor. Issues Ergon. Sci . 5, 27–42. doi: 10.1080/1463922031000086744

Khalid, H. M., and Helander, M. G. (2006). Customer emotional needs in product design. Concurrent Eng . 14, 197–206. doi: 10.1177/1063293X06068387

Kiernan, L., Ledwith, A., and Lynch, R. (2019). Comparing the dialogue of experts and novices in interdisciplinary teams to inform design education. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ . 30, 1–20. doi: 10.1007/s10798-019-09495-8

Kumar Ranganathan, S., Madupu, V., Sen, S., and R. Brooks, J. (2013). Affective and cognitive antecedents of customer loyalty towards e-mail service providers. J. Serv. Mark . 27, 195–206. doi: 10.1108/08876041311330690

Kumar, M., and Garg, N. (2010). Aesthetic principles and cognitive emotion appraisals: how much of the beauty lies in the eye of the beholder? J. Cons. Psychol . 20, 485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2010.06.015

Landwehr, J. R., Labroo, A. A., and Herrmann, A. (2011). Gut liking for the ordinary: incorporating design fluency improves automobile sales forecasts. Mark. Sci . 30, 416–429. doi: 10.1287/mksc.1110.0633

Landwehr, J. R., Wentzel, D., and Herrmann, A. (2012). The tipping point of design: how product design and brands interact to affect consumers' preferences. Psychol. Mark . 29, 422–433. doi: 10.1002/mar.20531

Langdon, P., Lewis, T., and Clarkson, J. (2007). The effects of prior experience on the use of consumer products. Univers. Access Inform. Soc . 6, 179–191. doi: 10.1007/s10209-007-0082-z

Langdon, P. M., Lewis, T., and Clarkson, P. J. (2010). Prior experience in the use of domestic product interfaces. Univers. Access Inform. Soc . 9, 209–225. doi: 10.1007/s10209-009-0169-9

Lewis, J. E., and Neider, M. B. (2017). Designing wearable technology for an aging population. Ergon. Des . 25, 4–10. doi: 10.1177/1064804616645488

Li, X., and Gunal, M. (2012). Exploring cognitive modelling in engineering usability design. J. Eng. Des . 23, 77–97. doi: 10.1080/09544828.2010.528379

Li, X., Zhao, W., Zheng, Y., Wang, R., and Wang, C. (2014). Innovative product design based on comprehensive customer requirements of different cognitive levels. Sci. World J . 2014:627093. doi: 10.1155/2014/627093

Lin, L., Yang, M.-Q., Li, J., and Wang, Y. (2012). A systematic approach for deducing multi-dimensional modeling features design rules based on user-oriented experiments. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 42, 347–358. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2012.03.005

Liu, C.-Y., and Tong, L.-I. (2018). Developing automatic form and design system using integrated grey relational analysis and affective engineering. Appl. Sci . 8:91. doi: 10.3390/app8010091

Lo, C.-H., and Chu, C.-H. (2014). An investigation of the social-affective effects resulting from appearance-related product models. Hum. Fact. Ergon. Manuf. Serv. Indust . 24, 71–85. doi: 10.1002/hfm.20352

Lu, C.-C. (2017). Interactive effects of environmental experience and innovative cognitive style on student creativity in product design. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ . 27, 577–594. doi: 10.1007/s10798-016-9368-x

Lu, W., and Petiot, J. F. (2014). Affective design of products using an audio-based protocol: application to eyeglass frame. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 44, 383–394. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2014.01.004

Martinez-Levy, A., Cherubino, P., Cartocci, G., Modica, E., Rossi, D., Mancini, M., et al. (2017). Gender differences evaluation in charity campaigns perception by measuring neurophysiological signals and behavioural data. Int. J. Bioelectr . 19, 25–35.

Mattioda, R. A., Mazzi, A., Canciglieri, O., and Scipioni, A. (2015). Determining the principal references of the social life cycle assessment of products. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess . 20, 1155–1165.

Maturana, H. R., and Varela, F. J. (1987). The Tree of Knowledge: The Biological Roots of Human Understanding . Boston, MA; London: Shambala/New Science Library.

Mehta, R., and Zhu, R. J. (2009). Blue or red? Exploring the effect of color on cognitive task performances. Science 323, 1226–1229. doi: 10.1126/science.1169144

Mele, M., and Campana, G. (2018). Prediction of Kansei engineering features for bottle design by a Knowledge Based System. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 12, 1201–1210. doi: 10.1007/s12008-018-0485-5

Mieczakowski, A., Langdon, P., and Clarkson, P. J. (2013). Investigating designers' and users' cognitive representations of products to assist inclusive interaction design. Univers. Access Inform. Soc . 12, 279–296. doi: 10.1007/s10209-012-0278-8

Miesler, L. (2011). Isn't it cute: an evolutionary perspective of baby-schema effects in visual product designs. Int. J. Des. 5:14.

Modica, E., Cartocci, G., Rossi, D., Martinez-Levy, A. C., Cherubino, P., Maglione, A. G., et al. (2018). Neurophysiological responses to different product experiences. Comput. Intell. Neurosci . 2018:9616301. doi: 10.1155/2018/9616301

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., and Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Montewka, J., Goerlandt, F., Innes-Jones, G., Owen, D., Hifi, Y., and Puisa, R. (2017). Enhancing human performance in ship operations by modifying global design factors at the design stage. Reliabil. Eng. Syst. Safety 159, 283–300. doi: 10.1016/j.ress.2016.11.009

Mu, J. (2015). Marketing capability, organizational adaptation and new product development performance. Industr. Mark. Manag . 49, 151–166. doi: 10.1016/j.indmarman.2015.05.003

Murphy, E. D. (2015). The time has come for redundant coding in print publications. Ergon. Des . 23, 28–29. doi: 10.1177/1064804615572630

Nagamachi, M. (1989). Kansei Engineering . Tokyo: Kaibundo Publisher.

Nagamachi, M. (2002). Kansei engineering as a powerful consumer-oriented technology for product development. Appl. Ergon . 33, 289–294. doi: 10.1016/S0003-6870(02)00019-4

Nam, T.-J., and Kim, C. (2011). Enriching interactive everyday products with ludic value. Int. J. Des . 14, 85–98.

Noble, C. H., and Kumar, M. (2008). Using product design strategically to create deeper consumer connections. Bus. Horizons 51, 441–450. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2008.03.006

Norman, D. (1988). The Design of Everyday Things . New York, NY: Basic Books.

Norman, D. A. (2004). Emotional Design: Why Do We Love (or Hate) Everyday Things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Orth, D., and Thurgood, C. (2018). Designing objects with meaningful associations. Int. J. Des . 12:14.

Pagani, R. N., Kovaleski, J. L., and Resende, L. M. (2015). Methodi Ordinatio: a proposed methodology to select and rank relevant scientific papers encompassing the impact factor, number of citation, and year of publication. Scientometrics 105, 2109–2135. doi: 10.1007/s11192-015-1744-x

Page, C., and Herr, P. M. (2002). An investigation of the processes by which product design and brand strength interact to determine initial affect and quality judgments. J. Cons. Psychol . 12, 133–147. doi: 10.1207/S15327663JCP1202_06

Persad, U., Langdon, P., and Clarkson, J. (2007). Characterising user capabilities to support inclusive design evaluation. Univers. Access Inform. Soc . 6, 119–135. doi: 10.1007/s10209-007-0083-y

Perttula, M., and Sipilä, P. (2007). The idea exposure paradigm in design idea generation. J. Eng. Des . 18, 93–102. doi: 10.1080/09544820600679679

Randhawa, K., Wilden, R., and Hohberger, J. (2016). A bibliometric review of open innovation: setting a research agenda. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 33, 750–772. doi: 10.1111/jpim.12312

Rindova, V. P., and Petkova, A. P. (2007). When is a new thing a good thing? Technological change, product form design, and perceptions of value for product innovations. Org. Sci . 18, 217–232. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1060.0233

Schifferstein, H. N., and Hekker, P. (2011). Product Experience . Amsterdam, NT: Elsevier.

Schifferstein, H. N. J., and Spence, C. (2008). “Multisensory product experience,” in Product Experience , eds N. J. S. Hendrik and P. Hekkert (Elsevier), 133–161. doi: 10.1016/B978-008045089-6.50008-3

Setchi, R., and Asikhia, O. K. (2019). Exploring user experience with image schemas, sentiments, and semantics. IEEE Trans. Affect. Comput . 10, 182–195. doi: 10.1109/TAFFC.2017.2705691

Seva, R. R., Duh, H. B.-L., and Helander, M. G. (2007). The marketing implications of affective product design. Appl. Ergon . 38, 723–731. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2006.12.001

Seva, R. R., Gosiaco, K. G. T., Santos, M. C. E. D., and Pangilinan, D. M. L. (2011). Product design enhancement using apparent usability and affective quality. Appl. Ergon . 42, 511–517. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2010.09.009

Seva, R. R., and Helander, M. G. (2009). The influence of cellular phone attributes on users' affective experiences: a cultural comparison. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 39, 341–346. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2008.12.001

Shen, H.-C., and Wang, K.-C. (2016). Affective product form design using fuzzy Kansei engineering and creativity. J. Ambient Intell. Hum. Comput . 7, 875–888. doi: 10.1007/s12652-016-0402-3

Spendlove, D. (2008). The locating of emotion within a creative, learning and product orientated design and technology experience: person, process, product. Int. J. Technol. Des. Educ . 18, 45–57. doi: 10.1007/s10798-006-9012-2

Turner, J. A., and Laird, A. R. (2012). The cognitive paradigm ontology: design and application. Neuroinformatics 10, 57–66. doi: 10.1007/s12021-011-9126-x

Van Eck, N. J., and Waltman, L. (2017). Citation-based clustering of publications using CitNetExplorer and VOSviewer. Scientometrics 111, 1053–1070. doi: 10.1007/s11192-017-2300-7

van Kleef, E., van Trijp, H. C. M., and Luning, P. (2005). Consumer research in the early stages of new product development: a critical review of methods and techniques. Food Qual. Pref . 16, 181–201. doi: 10.1016/j.foodqual.2004.05.012

Van Rompay, T., and Ludden, G. (2015). Types of embodiment in design: the embodied foundations of meaning and affect in product design. Int. J. Des . 9, 1–11.

Venkatraman, V., Clithero, J. A., Fitzsimons, G. J., and Huettel, S. A. (2012). New scanner data for brand marketers: How neuroscience can help better understand differences in brand preferences. J. Cons. Psychol . 22, 143–153. doi: 10.1016/j.jcps.2011.11.008

Wang, W. M., Li, Z., Liu, L., Tian, Z. G., and Tsui, E. (2018). Mining of affective responses and affective intentions of products from unstructured text. J. Eng. Des . 29, 404–429. doi: 10.1080/09544828.2018.1448054

Wiecek, A., Wentzel, D., and Landwehr, J. R. (2019). The aesthetic fidelity effect. Int. J. Res. Mark . 36, 542-557. doi: 10.1016/j.ijresmar.2019.03.002

Wrigley, C. (2013). Design dialogue: the visceral hedonic rhetoric framework. Des. Issues 29, 82–95. doi: 10.1162/DESI_a_00211

Wrigley, C. J. (2011). Visceral hedonic rhetoric (thesis Ph.D.) Brisbane: Queensland University of Technology.

Xu, X., Hsiao, H.-H., and Wang, W. W.-L. (2012). FuzEmotion as a backward kansei engineering tool. Int. J. Autom. Comput . 9, 16–23. doi: 10.1007/s11633-012-0611-y

Yang, C.-C., and Chang, H.-C. (2012). Selecting representative affective dimensions using procrustes analysis: an application to mobile phone design. Appl. Ergon. 43, 1072–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.apergo.2012.03.008

Yang, C.-C., and Shieh, M.-D. (2010). A support vector regression based prediction model of affective responses for product form design. Comput. Industr. Eng . 59, 682–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2010.07.019

Yang, C. C. (2011). Constructing a hybrid Kansei engineering system based on multiple affective responses: application to product form design. Comput. Industr. Eng . 60, 760–768. doi: 10.1016/j.cie.2011.01.011

Yang, X., He, H., Wu, Y., Tang, C., Chen, H., and Liang, J. (2016). User intent perception by gesture and eye tracking. Cogent Eng . 3:1221570. doi: 10.1080/23311916.2016.1221570

Yuen, K. K. F. (2014). A hybrid fuzzy quality function deployment framework using cognitive network process and aggregative grading clustering: an application to cloud software product development. Neurocomputing 142, 95–106. doi: 10.1016/j.neucom.2014.03.045

Zayas-Cabán, T., and Chaney, K. J. (2014). Improving the Effectiveness of Consumer Health IT. Ergono. Des . 22, 26–28. doi: 10.1177/1064804614539328

Zhai, L.-Y., Khoo, L.-P., and Zhong, Z.-W. (2009). A rough set based decision support approach to improving consumer affective satisfaction in product design. Int. J. Industr. Ergon . 39, 295–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ergon.2008.11.003

Zhou, F., Ji, Y., and Jiao, R. J. (2013). Affective and cognitive design for mass personalization: status and prospect. J. Intell. Manuf . 24, 1047–1069. doi: 10.1007/s10845-012-0673-2

Keywords: cognitive, affective, consumer, product design, systematic review, state of the art

Citation: Tavares DR, Canciglieri Junior O, Guimarães LBdM and Rudek M (2021) A Systematic Literature Review of Consumers' Cognitive-Affective Needs in Product Design From 1999 to 2019. Front. Neuroergon. 1:617799. doi: 10.3389/fnrgo.2020.617799

Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 23 December 2020; Published: 03 February 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Tavares, Canciglieri Junior, Guimarães and Rudek. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: David Ribeiro Tavares, economicdavid@hotmail.com

This article is part of the Research Topic

Advances in Affective Neuroergonomics

Creativity in the marketing and consumer behavior literature: a structured review and a research agenda

- Published: 18 February 2020

- Volume 2020 , pages 85–124, ( 2020 )

Cite this article

- Gaetano Miceli ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6869-6161 1 &

- Maria Antonietta Raimondo ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3883-592X 1

1227 Accesses

3 Citations

Explore all metrics

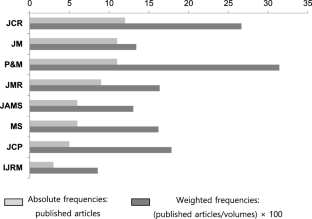

Creativity is one of the most studied concepts in social sciences. Its relevance in disparate disciplines has stimulated the production of a plethora of contributions. Not surprisingly, marketing and consumer behavior scholars have devoted significant efforts to the study of creativity and have offered a relevant though fragmented corpus of contributions that needs a synthesis to guide further research on such a pervasive, yet crucial, concept. This article presents and discusses a structured review of studies on creativity published in eight major marketing and consumer behavior journals. We classify previous research upon a popular alliterative model—the 4Ps of creativity, person, process, product, and press—to present a comprehensive view of the state of research on creativity. The review is instrumental to the identification of eight research directions, two for each of the 4Ps areas, for future research that marketing and consumer behavior scholars can pursue to produce novel and meaningful contributions on one of the most elusive constructs in social sciences.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Online influencer marketing

Social media influencer marketing: foundations, trends, and ways forward

Research in marketing strategy