- Netherlands

- Saudi Arabia

- South Africa

- Switzerland

- United Arab Emirates

- United Kingdom

Children's Education

The education system in Italy

Are you and your little ones moving to Italy? Learn how to navigate the Italian education system and how to access international schools.

By Valentine Marie

Updated 15-5-2024

Moving with children to a new country is both daunting and fun. If you are considering Italy , there’s plenty to look forward to: the delicious food , the sunny weather , and the rich culture . However, given that education in Italy is compulsory until 16 years old, you’ll need to sort out your child’s schooling pronto .

To get started, here are the ins and outs of Italy’s education system, from the enrollment process to financial aid to changing schools:

Education in Italy

Preschool education in italy, the primary school system, public primary schools in italy, private primary schools, the secondary school system, public secondary schools in italy, private secondary schools, the international baccalaureate (ib) in italy, graduating in italy, tips for saving on schoolbooks, educational support for international students, hospital schools, changing schools in italy, parent involvement in italian schooling, homeschooling in italy, useful resources.

The education system in Italy is mainly state-funded, with public schools often being the most sought-after option. However, you can also access private and international schools in the country.

Education is mandatory from ages 6–16. On average, students can expect to go through 16.7 years of education in Italy, which falls below the OECD average of 18 years. When it comes to quality of education, Italy scores 477 for reading, mathematics, and sciences, which is just below the OECD average of 488.

The Italian government prioritizes educational inclusion, so education is open to citizens and internationals. Overseen by the Ministry of Education and Merit ( Ministero dell’Istruzione e del Merito – Muir ), Italy’s education system splits into five phases:

| Kindergarten ( ) | 3–6 |

| Primary ( ) | 6–11 |

| Lower secondary ( ) | 11–14 |

| Upper secondary ( ) or the regional vocational training system ( ) | 14–19 |

| University ) | Bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees |

Although preschool education in Italy is not required, many parents access these facilities for childcare, enabling them to return to work . Public preschools communicate primarily in Italian , which could be tricky but can help your international child to learn the language .

Italian preschool divides into two sections:

- Day nursery ( nido d’infanza ): from 3 months to 3 years old

- Nursery school ( scuola dell’infanzia ): between the ages of 3–6

The state subsidizes many preschools, but there are regional differences in costs . For example, you would generally pay more in the north than in the south. If your child’s school doesn’t charge tuition fees, you only need to pay for registration and school lunches. Again, the lunch fee ( refezione scolastica ) varies depending on location and the family’s income. Some state preschools also prioritize places for lower-income families and charge them lower monthly fees if any.

Italian primary education

Primary schools in Italy ( scuola primaria ) cater for students from ages 6 to 11. It is mandatory for all students living in Italy, regardless of immigration, economic, or disability status. Public schools can provide linguistic support to migrant students with limited knowledge of Italian.

Although students do not have to attend their closest school, local children may receive preference over those living in another municipality.

Public primary schools in Italy are free and are popular among Italian families. Schools often focus on learning through rote memorization: a teaching method focused on recalling information.

Core subjects include:

- Mathematics

Classes typically accommodate 14 to 20 students at a time.

Italian children typically attend school for 24 to 40 hours a week. Most schools have a school week from Monday to Friday, but many also have classes on a Saturday. If a school runs for six days, their teaching hours may be from 08:30 to 13:00. However, if the school week ends on a Friday, the school day may finish at 16:00 with an hour lunch break. Be sure to ask about the schedule when touring prospective schools.

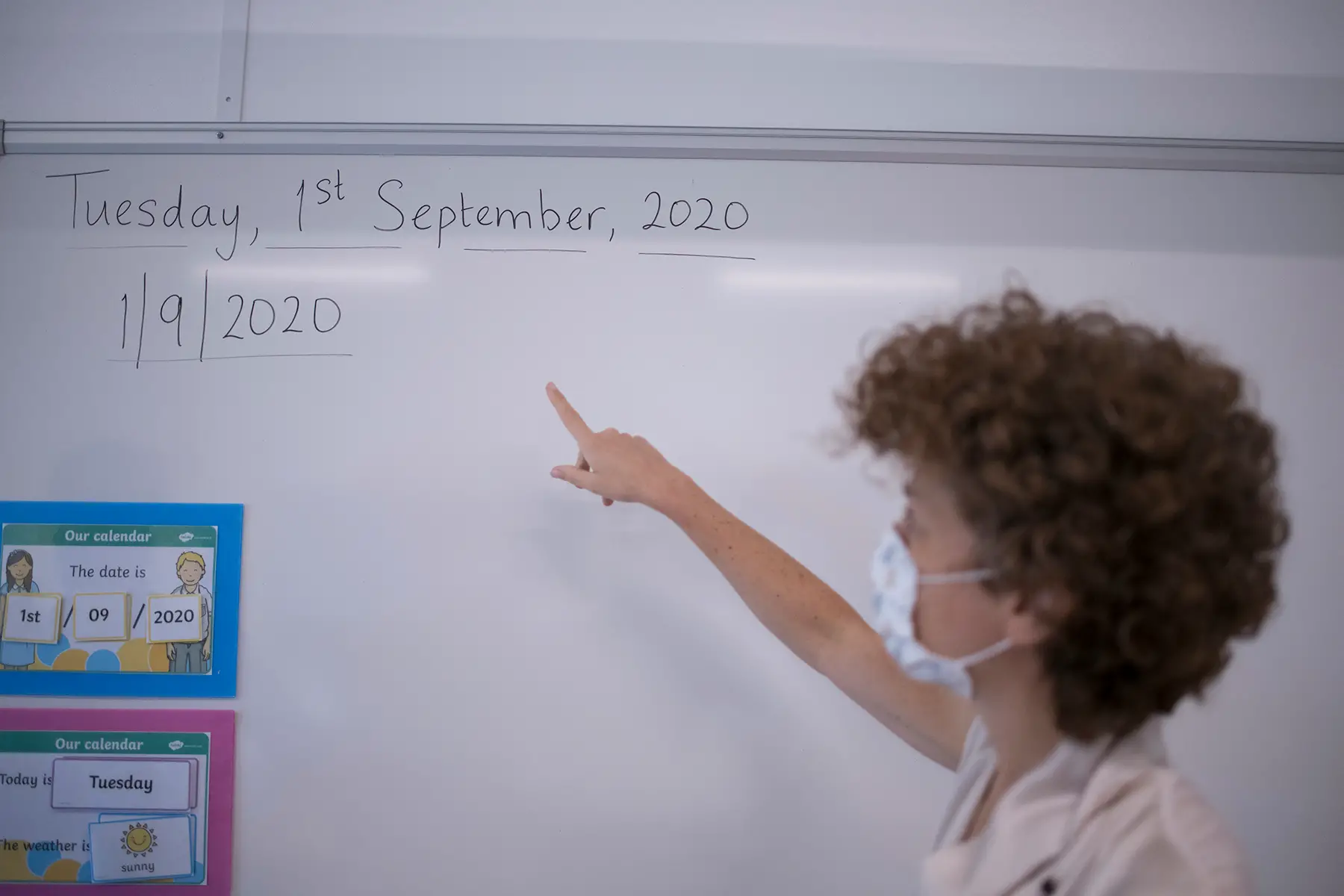

The school year runs from September to June, with four holiday breaks , summer being the longest. Schools also close on public holidays , which can have regional variations.

Private primary schools in Italy are available but not popular among Italians. Of course, if parents prefer a particular educational approach (e.g., Montessori or Steiner), they may choose private education for their children.

In Italy, independent primary schools generally fall into one of these categories:

| Religious | Catholic (mostly) Muslim, Buddhist, Jewish |

| Mostly primary schools Follow the child approach Encourage the child to learn at own pace by doing Nurture individual development Develop critical thinking skills and lifelong learning | |

| Artistic, creative approach Develop whole child – mind, body, spirit Strong student-teacher relationship Work with rhythm, repetition, music, stories, nature, art | |

| (Without a Backpack) | Instead of backpacks crammed with homework and learning materials, functional workstations are set up in class to encourage independent learning Instill a sense of community and responsibility |

Most Italian independent schools follow the same national curriculum and standards as public schools, with a similar level of educational quality. Still, private schools tend to have smaller class sizes (i.e., more personal attention from the teacher), better facilities, and more extracurricular activities.

Primary schools in Italy

International schools – popular with expats – are independent and do not have to adhere to the national syllabus. Instead, they will follow their home country’s curriculum.

Tuition fees for private schools (primary and secondary) are expensive and vary greatly, depending on the grade or year, location, curriculum, and facilities offered. On average, yearly payments range from €4,000 to 27,000.

Secondary education in Italy

Secondary school education in Italy organizes into two parts:

| Lower secondary ( | 11–14 |

| Upper secondary ( ) | 14–19 |

At the age of 16, students complete their compulsory education. However, most learners go on to complete upper secondary education.

All public secondary schools in Italy are free. Still, parents need to purchase their children’s textbooks and educational supplies.

Many public schools focus on rote memorization as their teaching method. However, students can opt for different educational paths at the upper secondary level.

Secondary schools in Italy

As such, they can follow these specialized streams:

| Lyceums ( | These schools focus on academics and specialize in a range of topics, such as languages, sciences, music, and classics. After lyceums, students can go on to university, provided they receive their upper secondary school certificate. |

| Technical institutes ( ) | These institutes focus on a theoretical foundation of knowledge, followed by specialization in fields, such as electrical engineering, information technology, communications, and more. Students at these schools typically do internships in their fifth year. |

| Artistic institutes ( ) | These programs last three years and prepare students to pursue a career in the arts. |

| Teacher training programs ( ) | These five-year programs prepare pupils to become primary school teachers. |

| Vocational programs ( ) | These programs prepare students to begin working in their field and can last between 3 and 5 years. Study areas include agriculture, food and wine, social work, and more. |

A small number of Italian students are in private education. In 2020, only 7% of secondary school enrolments were for private schools. These usually have a religious or methodological focus, but teach the same syllabus. So, the standard of education between schools hardly differs.

Below are the types of private schools you can find in Italy:

| Religious schools | Mostly Catholic Heavier focus on religious study and ethics |

| Boarding schools | Rare in Italy Instruction is usually not in Italian Student population is generally wealthy and international |

| Montessori schools | Named after Italian scholar, The methodology revolves around children’s instinctive interests, rather than formal teaching |

| International schools | Popular with transient expat families Tend to be bilingual (home language and Italian) Multicultural environment |

International Baccalaureate (IB) schools teach a rigorous and internationally recognized curriculum that focuses on essay writing, creativity, and community service, alongside the expected academic courses.

Many expats appreciate the IB program because universities worldwide recognize the IB Diploma, giving students a wider choice of higher education opportunities. There are currently over 30 IB schools in Italy .

Students who have completed five years of Italian upper secondary schooling can sit the state final exam ( esame di maturità ). If they pass, they can apply to universities in Italy.

Of course, international schools’ assessments and graduation will look different. Depending on the curriculum, graduates may qualify to study at universities outside of Italy, including those in the United Kingdom (UK) , the United States (US), and further afield.

Financial aid and scholarships

As Italian public education is free, parents and guardians only need to pay for books and school supplies. However, due to inflation and the rising cost of living , some families may struggle to afford these expenses, which could lead to early school leaving. Therefore, the government launched the Fondo Unico (Single Fund) scheme to help secondary students cover school-related expenses.

You can apply online and pick up the student card ( La Carta dello Studente ) from any local post office , presenting the following documentation.

If you are 18 or older:

- Identification (e.g., a passport or ID card)

- A tax code ( codice fiscale )

If you are younger than 18, your parents must also show their:

- Identification

- Completed self-declaration (PDF in Italian) to be signed by the postal service clerk

The state does not subsidize nor offer financial support for children wanting to enroll in private or international schools. However, some schools do offer payment plans or scholarships.

You can contact the school administration directly to discuss these options. Most schools will ask for proof of the family’s financial situation. Some institutions may also give preference to alumni families or students with siblings already attending.

Another way that parents can save some money is by selling their books from the previous year. Many bookstores in Italy give a huge discount on books for the following year if you sell them your used schoolbooks. In addition, booksellers such as IBS and Libraccio have regular sales on textbooks and stationery.

The country’s public and private schools generally teach in Italian , which could be a challenge for international children who do not speak the language. While there is linguistic support to help non-Italian students academically, the expectation is that, eventually, learners will become fluent.

The Ministry of Education has also launched several projects to support migrant children (especially unaccompanied minors or refugees ) to integrate into the Italian education system.

International schools in Italy

International schools are well equipped to support students struggling to adapt to their expat life in a new country with linguistic, developmental, and mental health services. That said, facilities may differ between institutions. So, discuss with prospective schools how they will meet your child’s needs.

Inclusive or accessible education in Italy

Italy follows an inclusive education policy , often referred to as special needs education ( bisogni educativi speciali ). This means no separate specialized schools are dedicated to teaching children with disabilities, learning difficulties, or behavioral challenges. Instead, a public school must work with the national health service and the Ministry of Education to create a personalized education plan ( piano educativo individualizzato – PEI) for the child. This plan details an individualized support strategy to enable the student to reach their learning goals.

When it comes to adaptive education services in private or international schools, support teachers ( insegnanti di sostegno ) are present in the class to work with a student individually. They can also recommend any extramural care if your child needs it.

Italy has decentralized many support services, but two good sources of information include:

- Special Kids of Rome – an online resource about inclusive international schools in Rome ( Roma )

- FISH – the Federazione Italiana per il Superamento dell’Handicap (Italian Federation for Disability Support)

Children who spend much time in the hospital – with chronic or severe health conditions – can fall behind academically. Therefore, hospital schools ( La Scuola in Ospedale ) also use PEIs to help them keep up with their education.

Although the process depends on the institution, most schools are flexible and accommodating regarding students changing schools. For public schools, you must first inform the current facility and obtain a written request signed by the principal. With this, you can apply to your new school and provide the required documents, which may include:

- Academic records

- A form of identification for children and guardians (e.g., a passport or birth certificate)

- Proof of address (e.g., utility bill )

Private schools have their own processes, so check your facility’s prospectus to be clear about the procedure.

While many parents are involved (PDF) in their children’s education, they do not tend to form parent organizations in public schools. Most guardians communicate directly with the teachers or other staff.

However, many international schools have Parent-Teacher Associations (PTAs) that encourage parental involvement, help fundraise, and integrate new families.

If you are interested in being a part of your child’s school experience, ask the administration about the options when you enroll them.

Homeschooling in Italy is legal but not widely accessed. That said, with the advent of the COVID-19 pandemic, this alternative education route is growing in popularity. Between 2018 and 2021, the number of home-schooled students in Italy almost tripled . Children with chronic illnesses hindering their school attendance may also follow this route.

Recently, the Italian government has started to regulate homeschooling more. For example, in 2017, it stipulated that students must pass annual school exams to remain home-educated. As such, parents must also be in more regular contact with school officials.

- Ministry of Education (MIUR) – manages the education system in Italy

- IB Organization – IB schools in Italy

- International Schools Database – online portal to find schools in Italy and compare fees

- FISH – Italian Federation for Disability Support

- Borse di Studio – government financial support scheme to help secondary students from low-income famlies with school expenses

Related Articles

THE ITALIAN SCHOOL SYSTEM: how does education work in Italy?

A question that is often asked on our pages is about how the school system is organized in Italy! In fact, every school system is different depending on the country you live in and for many foreigners it’s difficult to understand the subdivision and the functioning of the Italian system. Therefore, in the following lesson we’re going to clear up any confusion about this topic!

- Facebook LearnAmo

- Instagram LearnAmo

- Twitter LearnAmo

- YouTube LearnAmo

- TikTok LearnAmo

- Pinterest LearnAmo

The structure of the Italian school system

Before we begin, you need to know that Italian schools can be:

– public : State-funded

– private : funded through school fees, namely the sums of money paid by the students

The academic programs of both of these types of school follow the regulations from the MIUR (Ministry of Education, University and Research)

Now let’s see the various steps:

1) Infant school

The attending of this school is not obligatory (parents can decide to register their children in accordance with the needs), and it’s divided into:

– asilo nido (kindergarten) : attended by 0-to-3 years old children

– scuola materna (preschool) : attended by 3-to-6 years old children

From 6 to 16 years of age, attending school becomes obligatory, as established by the law, and we enter the so-called scuola dell’obbligo (compulsory education) , that starts with:

2) primary or elementary school

This school is attended by 6 to 11 years old students: thus the attending lasts 5 years. During those years, boys and girls learn to write and read and they apprehend the first notions of History, Geography, Mathematics, Italian Grammar, Science, Music and Physical Education and, for a few years now, also English and Computer Science while Religion classes are optional.

3) 1st grade secondary or middle school

This step lasts 3 years and involves students from 11 to 13 years of age. During this period, the students deepen the various subjects studied in elementary school, and at the end of it, they must take the esame di terza media (middle school exam) , composed by:

- Italian written test

- written Math test

- written language test

- oral which consists in the presentation of a work on a specific topic including all the studied subjects.

4) upper secondary school or high school

This step lasts 5 years and involves 14 to 19 years old students, but from the age of 16 boys and girls have the possibility to abandon their studies.

The students can choose among 3 types of di high schools, depending on their goals:

Liceo : it offers a more theoretical education and more oriented to further education at the University and, depending on the subjects studied, they can be of different types:

– classico (grammar) (Latin, Greek and Italian)

– scientifico (scientific) (Mathematics, Physics and Science)

– linguistico (language) (English and foreign languages)

– tecnologico (technology) (Computer Science)

– artistico (artistic) (art),

– musicale (music).

Professional Technical High School : in this type of school in addition to common subjects, students can acquire practical-technical skills, suited to the entry into employment, in sectors like:

– economy

– tourism

– technology

– agricolture

– healthcare professions

ITF (Vocational education and training) : in this type of school, students acquire practical and professional skills. The studies in these schools focus on jobs like:

– plumber

– electrician

– hairdresser

– beautician …

At the end of high school student must take another exam, the feared esame di maturità (graduation exam) which is composed by 3 written tests and 1 oral examination, and if you pass it, you’ll receive a degree of maturity, that will allow you to have access to University .

5) University

It’s divided into:

First cycle : also known as “laurea triennale” and, as its name suggest, it lasts 3 years. There’s a wide and diverse selection of Italian universities like:

– scientific departments (Mathematics, Physics, Astrophysics, Chemistry…),

– humanities faculty (Literatures, Philosophy, Foreign Languages, Cultural Heritage…)

– technical faculties (Architecture, Engineering, Economy…).

Second cycle : also known as “laurea magistrale” or “specialistica” (second level degree), it usually lasts 2 years and it’s the continuation of the first cycle to ensure the students a higher level of specialization. However, there are some courses (Faculty of law, Faculty of Pharmacy, Construction Engineering, Architecture etc) that last 5 years (6 years as regards Med School) and take the name of “ Corsi di Laurea a ciclo unico ” (Single Cycle Degree Course)

Third cycle: it’s devoted to the most ambitious students and it includes:

– master : they’re usually short courses of study that offer the opportunity (to those who are interested) to deepen some specific aspects of the subject studied during the first two cycles.

– doctoral degrees : they’re theoretical courses, that are perfect for those who desire a career in the academic field or in the field of research.

Well, this is the Italian school system. Let us know how the school systems in your countries work! If you want to speak Italian like a true native speaker, don’t miss the promo 2×1 that includes our course Italiano in Contesto and a digital copy of our book Italiano Colloquiale , at the price of 69 euros .

Podcast: Play in new window | Download (Duration: 10:01 — 9.2MB)

Iscriviti: Apple Podcasts | Spotify | Android | iHeartRadio | Blubrry | Podcast Index | Email | TuneIn | Deezer | RSS | Altri...

One thought to “THE ITALIAN SCHOOL SYSTEM: how does education work in Italy?”

Just a clarification: It’s not specified really well in the text, but Lyceum students do not ONLY study the subjects that are specific to their learning goal. Scientific Lyceum, Classical Lyceum, and so on, we have up to 10-11 subjects for five consecutive years. All of these subjects are usually done as rigorously as the others, and (I’m a Liceo Scientifico student) we often have the same amount of class hours for things such as Mathematics and Literature, or English Lit. and Physics. The objective of this school is to have a very broad and quite detailed program for the main subjects.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

- Introduction & Quick Facts

- Mountain ranges

- Coastal areas

- Animal life

- Ethnic groups

- Traditional regions

- Rural areas

- Urban centres

- Internal migration patterns

- Emigration and immigration

- Public and private sectors

- Postwar economic development

- Later economic trends

- Field crops

- Iron and coal

- Mineral production

- Mining and quarrying

- Development of heavy industry

- Light manufacturing

- Construction

- Business services

- Labour and taxation

- Water transport

- Rail transport

- Road transport

- Air transport

- Telecommunications

- Constitution of 1948

- The legislature

- The presidential office

- The government

- Regional and local government

- Electoral system

- Political parties

- The participation of the citizen

- Health and welfare

Cultural milieu

- Daily life and social customs

- Visual arts

- Architecture

- Museums and galleries

- Cultural institutes

- Sports and recreation

- Media and publishing

- Fifth-century political trends

- The Ostrogothic kingdom

- The end of the Roman world

- The Lombard kingdom, 584–774

- Popes and exarchs, 590–800

- Lombard Italy

- Byzantine Italy

- Similarities between Lombard and Byzantine states

- The role of Rome

- The reign of Berengar I

- The south, 774–1000

- Literature and art

- Subsistence cultivation

- The growing power of the aristocracy

- Socioeconomic developments in the city

- The Ottonian system

- Social and economic developments

- The papacy and the Normans

- The Investiture Controversy

- The rise of communes

- Papal-imperial relations

- Institutional reforms

- Northern Italy

- Economic and cultural developments

- Relations to the papacy

- The kingdom of Jerusalem

- The Sicilian kingdom

- The war in northern Italy

- The factors shaping political factions

- The end of Hohenstaufen rule

- Economic developments

- Cultural developments

- Characteristics of the period

- The southern kingdoms and the Papal States

- The popolo and the formation of the signorie in central and northern Italy

- Venice in the 14th century

- Florence in the 14th century

- Economic change

- Famine, war, and plague (1340–80)

- Political development, 1380–1454

- The southern monarchies and the Papal States

- The first French invasion

- The arts and intellectual life

- French loss of Naples, gain of Milan

- Spanish acquisition of Naples

- Tuscany and the papacy

- French victories in Lombardy

- New warfare

- Spanish victory in Italy

- The Kingdom of Naples

- The kingdom of Sicily

- The duchy of Milan

- Principates and oligarchic republics

- The duchy of Savoy

- The duchy of Tuscany

- The republic of Genoa

- The Republic of Venice

- The Papal States

- Culture and society

- Society and economy

- The 17th-century crisis

- Political thought and early attempts at reform

- Naples and Sicily

- The other Italian states

- The crisis of the old regime

- French invasion of Italy

- Roots of the Risorgimento

- The Italian republics of 1796–99

- Collapse of the republics

- The French Consulate, 1799–1804

- Northern and central Italy

- Sardinia and Sicily

- The end of French rule

- The Vienna settlement

- Economic slump and revival

- The rebellions of 1831 and their aftermath

- The Revolutions of 1848

- The role of Piedmont

- The war of 1859

- Garibaldi and the Thousand

- Condition of the Italian kingdom

- The acquisition of Venetia and Rome

- Forces of opposition

- Land reform

- Protectionism

- Social changes

- Domestic policies

- Colonialism

- Years of crisis

- Health and education

- Conduct of the war

- The cost of victory

- Economic and political crisis: the “two red years”

- The rise of Mussolini

- The end of constitutional rule

- Anti-Fascist movements

- Economic policy

- Foreign policy

- Military disaster

- End of the regime

- The republic of Salò (the Italian Social Republic) and the German occupation

- The partisans and the Resistance

- Birth of the Italian republic

- Parties and party factions

- Industrial growth

- Demographic and social change

- Economic stagnation and labour militancy in the 1960s and ’70s

- Student protest and social movements, 1960s to ’80s

- Politics in the 1970s and ’80s

- Regional government

- The economy in the 1980s

- The fight against organized crime

- Emergence of the “second republic”

- Economic strength

- The rise of Berlusconi

- Shifting power

- Scandal and the struggling economy

- The Renzi and Gentiloni governments

- The victory of populist parties

- Immigration and foreign policy

- How did Giuseppe Garibaldi become famous?

- How did Benito Mussolini rise to power?

- What were Benito Mussolini’s political beliefs?

- Where did the word fascism come from?

- What was Benito Mussolini’s role in World War II?

Education of Italy

The constitution guarantees the freedom of art, science, and teaching. It also provides for state schools and guarantees the independence of the universities. Private schools (mainly run by religious bodies) are permitted. The constitution further states that the public schools are open to all and makes provision for scholarships and grants.

Education is compulsory only for those age 6 to 16 years. The school system begins with kindergarten for the 3- to 6-year-olds. Primary schools are attended by children between the ages of 6 and 11, at which stage most go on to secondary schools for 11- to 14-year-olds, but those wishing to study music go directly to the conservatories.

Postsecondary schooling is not compulsory and includes a wide range of technical and trade schools, art schools, teacher-training schools, and scientific and humanistic preparatory schools. Pupils from these schools can then continue their education attending either non-university- or university-level courses. University education is composed of three levels. At the first level, it takes between two and three years to gain a diploma. At the second level, between four and six years are spent to gain a university degree. At the third level, specialized courses of two to five years’ duration or doctorate courses lasting three to four years are offered.

At the beginning of the 21st century, more than one-third of the population had a high school diploma, about one-third had a junior high school diploma, and more than one-tenth had obtained a college degree. But educational attainment is higher in the younger generations. About two-thirds of people of university age attend university, and almost nine-tenths of people of high school age attend high school. Most schools and universities are run by the state, with programs that are uniform across the country . Less than one-tenth of students attend private schools. University fees are low, and enrollment is unrestricted for most students with a postsecondary school diploma.

Cultural life

The 20th century saw the transformation of Italy from a highly traditional, agricultural society to a progressive, industrialized state. Although the country was politically unified in 1861, regional identity remains strong, and the nation has developed unevenly as a cultural entity. Many regional differences are lessening with the increasing influence of television and other mass media as well as a nationally shared school curriculum. Though Italians have long tended to consider themselves citizens of their town or city first, followed by their region or province and so on, this is changing as Italy becomes more closely integrated into the European Union (EU) and as Italians come to think of themselves as part of a supranational community made up of many peoples.

2.3 Organisation of the education system and of its structure

On this page, the structure of the education and training system, early childhood education and care (ecec), the first cycle of education, the second cycle of education, post-secondary non-tertiary education, tertiary education, adult education, compulsory education, home education.

The education and training system covers from Early childhood education and care (ECEC) to tertiary and adult education.

Education is compulsory for 10 years from 6 to 16 years of age. Compulsory education covers five years of primary education, three years of lower secondary education and two years of upper secondary education. The last two years of compulsory education can also be spent by attending the vocational education and training courses ( Istruzione e formazione professionale – IeFP), organised by the single Regions.

For a schematic representation of the education and training system please refer to the diagram in the ‘Overview’ section.

Early childhood education and care ( ECEC ) is organised into two different stages according to children's age: 0-3 years and 3-6 years. The two offers make up the so called 'integrated system 0-6', introduced by the law 107/2015. The whole ECEC phase is part of the education system and is not compulsory. The Ministry of education and merit has a general responsibility, per esempio for the allocation of financial resources to the local authorities, for the definition of the educational guidelines and for the promotion of the integrated system at local level.

Provision for children aged 0-3 years is organised at nurseries ( nidi d’infanzia ). Public ECEC (0-3) settings are run directly by the municipalities, while private settings are run by private subjects. All types of settings must comply with the general criteria defined at regional and national level. ECEC services are not free for families.

ECEC for children over 3 years of age is organised at preprimary schools ( scuole dell'infanzia ) and is free. This ECEC phase falls under the responsibilities of the Ministry of education and merit that provides the educational guidelines and the financial and human resources, while local authorities are in charge of the organisation of the facilities. Beside the State, the providers of ECEC can also be the municipalities themselves as well as private subjects.

The first cycle of education ( primo ciclo di istruzione ) is made up of primary and lower secondary education, for a total length of eight years. However, primary and lower secondary education are considered separate levels of education with their own specificities and are described separately.

Primary education

Primary education is organised at primary schools ( scuole primarie ). Primary education is compulsory, has an overall length of 5 years and is attended by pupils aged from 6 to 11. The aim of primary education is to provide pupils with basic learning and the basic tools of active citizenship. It helps pupils to understand the meaning of their own experiences.

Lower secondary education

The lower secondary level of education is organised at ‘first-level secondary schools’ ( scuole secondarie di I grado ). Lower secondary education is compulsory, lasts for three years and is attended by pupils aged 11 to 14 years. Lower secondary education aims at fostering the ability to study autonomously and at strengthening the pupils’ attitudes towards social interaction, at organising and increasing knowledge and skills and at providing students with adequate instruments to continue their education and training activities.

The second cycle ( secondo ciclo di istruzione ) offers two parallel paths:

- the upper secondary school education called ‘second-level secondary school’ ( istruzione secondaria di II grado )

- the vocational education and training system ( Istruzione e formazione professionale - IeFP ) organised at regional level

1) Upper secondary school education

The upper secondary level of education ( istruzione secondaria di II grado ) offers general, technical and vocational education. Studies last five years and are addressed to students aged from 14 to 19 years.

The general path is organised at general schools called ‘ licei ’. General education aims at preparing students to higher-level studies and to the labour world. It provides students with adequate competences and knowledge, as well as cultural and methodological instruments for developing their own critical and planning attitude.

Technical education is organised at technical institutes ( istituti tecnici ). It provides students with a solid scientific and technological background in the economic and technological professional sectors.

Vocational education is organised at vocational institute ( istituti professionali ). It provides students with a solid technical and vocational general background in the sectors of services, industry and handicraft, to facilitate access to the labour world.

At the end of the upper secondary school education students receive a qualification that gives access to tertiary education offered at universities, at the Higher education for the fine arts, music and dance ( Alta formazione artistica, musicale e coreutica – Afam) and at the Higher technological institutes ( Istituti tecnologici superiori – ITS).

2) Regional vocational education and training

Regional vocational education and training ( istruzione e formazione professionale – IeFP) is organised into three and four-year courses. Courses can be organised by both accredited local training agencies and by vocational upper secondary schools in partnership with training agencies. The main characteristic of courses is a wider use of laboratories and of periods of work experiences. The aim is to faster access to the job market. At the end of courses, learners receive a vocational qualification that gives them access to the second-level regional courses or, in case of the four-year programmes and at certain conditions, to tertiary education.

The post-secondary non-tertiary level offers two types of courses, both organised at regional level:

- Courses in the vocational education and training system ( istruzione e formazione professionale - IeFP)

- Courses in the Higher technical education and training system ( Istruzione e formazione tecnica superiore - IFTS)

The Regions organise short IeFP courses (400-800 hours) that are addressed to those who hold a qualification obtained either in the three- and four-year vocational education and training system (IeFP) or in the upper secondary vocational school education.

The IFTS courses aim at developing professional specialisations at post-secondary level to meet the requirements of the labour market, both in the public and private sectors.

The following types of institution offer tertiary education:

- Universities and equivalent institutions

- Institutes of the Higher education for the fine arts, music and dance ( Alta formazione artistica, musicale e coreutica - Afam )

- Higher technological institutes ( Istituti tecnologici superiori – ITS)

Universities and Afam institutes offer programmes of the first, second and third cycle according to the Bologna structure and issue the relevant qualifications. In addition, universities and Afam institutes organise courses leading to qualifications outside the Bologna structure.

Higher technological institutes are highly specialised technical schools that offer programmes in the technical and technological sectors, corresponding to the levels 5 and 6 of the EQF. ITSs have been recently reformed. Main changes are described in the chapter on ongoing reforms in higher education .

The system of formal adult education ( istruzione degli adulti - IDA) refers to the domain of the educational activities aimed at the acquisition of qualifications of the education and training system. It falls under the responsibility of the Ministry of Education and merit. This type of provision is financed through public resources, and it is free for participants (16 years of age and above). Formal adult education is organised at Provincial Centres for School Education for Adults ( Centri provinciali per l’istruzione degli adulti – CPIA ) and involves also upper secondary schools.

The system offers:

- first-level courses, organised by CPIAs, aimed at obtaining an ISCED 1 and ISCED 2qualification and the certification of basic competences to be acquired at the end of compulsory education in vocational and technical education

- second-level courses, organised by upper secondary schools, aimed at the obtainment of a technical, vocational and artistic upper secondary school leaving certificate;

- literacy and Italian language courses for foreign adults, organised by CPIAs, aimed at the acquisition of competences in the Italian language at least at the level A2 of the Common European Framework of Reference for languages.

Courses are available also in detention centres.

Education is compulsory for ten years, between 6 and 16 years of age. Compulsory education covers ( DM 139/2007 ):

- five years of primary education,

- three years of lower secondary education

- the first two years of upper secondary education.

Students can also attend the last two years of compulsory education in the regional vocational education and training system ( Istruzione e formazione professionale – IeFP ).

Compulsory school education is organised at State schools or at independent schools with parity ( paritarie )These latter are either public or private independent schools that are equal to State schools. Subject to certain conditions, pupils and students can complete their compulsory education through home education ( istruzione parentale ), described below in the relevant article, or by attending independent schools without parity. The State also guarantees the right to study and to complete compulsory education to hospitalised pupils and to pupils held in detention centres for minors.

In addition to compulsory education, everyone has a right and a duty ( diritto/dovere ) to receive education and training for at least 12 years within the education system or until they have obtained a three-year vocational qualification by the age of 18 ( D.Lgs 76/2005 ).

Finally, 15-year-olds can also spend the last year of compulsory education on an apprenticeship, upon a specific arrangement between the Regions, the Ministry of labour, the Ministry of education and trade unions (law 183/2010).

Compulsory education refers to both enrolment and attendance. Parents are responsible for the attendance and completion of compulsory education. Supervision of compliance with compulsory education is the responsibility of the municipality of residence and of the head of the school attended by the individual pupil.

Those who do not continue with their studies after compulsory education, receive a certificate of completion of compulsory education that also describes the skills they have acquired. Dispositions on compulsory education apply to Italian citizens as well as to EU and non-EU citizens in compulsory school age.

Home education in Early childhood education and care (ECEC)

Law 107/2015 acknowledges home-based education ( servizi educativi in contesto domiciliare ) for children aged less than three years, as one of the alternatives to centre-based provision ( nido d’infanzia ), together with play areas and centres for children and families. These supplementary educational services have the purpose of meeting the needs of families through a flexible organisation and structure.

Home-based educational services welcome children from 3 to 36 months organised in very small groups under the care of one or more childminders.

The Regions and local authorities organise and monitor the offer in their own territories.

Home education during compulsory education

Pupils and students can attend home education ( istruzione parentale ) to complete compulsory education, which covers the whole primary and lower secondary levels of education and the first two years of upper secondary education, up to 16 years of age. Central legislation regulates home education during compulsory education (D.Lgs 297/1994, D.lgs 76/2005, D.Lgs 62/2017).

During compulsory school age, parents can decide to start home tuition at any time of the school year. However, they must certify to hold the technical skills and the economic capacity to deliver this kind of education on their own (Dlgs 297/1994 and Dlgs 76/2005). To this end, parents must submit a communication addressed to the school head of the school closest to the child’s resident area. The school head verifies the veracity of this declaration, but no authorisation is needed and the communication must be submitted every year.

Pupils attending home-based compulsory education must sit an aptitude examination every year both to continue home education and to be admitted to the State examination held at the end of lower secondary education. They also must pass an aptitude examination in case they are willing to enrol at school . The aptitude test aims at verifying the competences and skills acquired by pupils in home education and, therefore, to verify the accomplishment of compulsory education. Parents draw up the study plan for their child in coherence with the National guidelines issued at central level for the relevant level of education.

Once compulsory education is completed, students can finish their studies at school, either State or paritaria , upon passing the aptitude examination. Otherwise, they can complete the remaining three years through home education or attending a private institution. In this case, they sit for the State examination held at the end of upper secondary education, as external candidates. Central legislation regulates the participation of external candidates to the final State examination (please see the sections on the assessment of students in either general or vocational upper secondary education).

In school year 2021/2022, pupils attending home education were 11 363 at primary level, 6 122 in lower secondary school, while students in upper secondary education were 1 972 (Source: elaboration of data, Ministero dell’istruzione e del merito – Rilevazioni sulle scuole).

Students at all levels of education, unable to attend school for health reasons , receive home tuition by school teachers. This type of tuition is not subject to the dispositions on home education.

Contents revised: 18 May 2023

- Society ›

Education & Science

Education in Italy - Statistics & Facts

Education in Italy is free and is compulsory for children aged between 6 and 16 years. The Italian education system is divided into nursery, kindergarten, elementary school, middle school, and high school. University is usually undertaken at the age of 19. Primary education is the first stage of compulsory education. In the last school years, there have been around 2.7 million children enrolled in almost 17 thousand elementary schools . On average, Italian elementary schools have around 19 pupils in each class. However, regional differences are remarkable: the average number of children per class in Emilia-Romagna is 20.6, whereas a class in Aosta Valley had on average 14.6 scholars. Factors like urbanization and rural exodus could explain such differences. Indeed, Aosta Valley is a mountainous region, while Emilia Romagna is one of the main industrial centers of Italy. Elementary education is followed by middle school. Students usually attend middle school for three years, from the age of 10 to 13. In the 2018/2019 school year, a total of 1.7 million students were enrolled in Italian middle schools . The Northern region of Lombardy counts the largest number of schools nationwide, followed by the Southern regions of Campania and Sicily. Together with the number of middle schools in the country , the average count of pupils per class has decreased slightly in recent years, reaching 20.8 children per class. High school education follows to middle school and it has a duration of five years. Generally, students can choose among three different types of upper secondary schools : lyceums, technical schools, and vocational schools. Among the different types of Italian upper secondary schools, lyceums are those most of all preparing students for the tertiary education the most. Moreover, technical high schools offer both a technical and a theoretical preparation, while vocational schools mostly focus on practical training. Nevertheless, all these types of secondary schools allow students to apply to university. About 40 percent of students who graduate from high school enroll at university. In the 2018/2019 academic year, the Central regions of Italy registered the highest enrollment rate , where 46 percent of all high school graduates decided to attend university. In the same year, there were over one million bachelor students in Italy, accounting for approximately 60 percent of all university students in the country. The most popular field of study in Italy is economics, followed by engineering. The largest Italian universities are La Sapienza University of Rome, in the Capital, the University of Bologna, which also ranks as the best Italian university, and the University of Turin. This text provides general information. Statista assumes no liability for the information given being complete or correct. Due to varying update cycles, statistics can display more up-to-date data than referenced in the text. Show more - Description Published by Statista Research Department , Jan 10, 2024

Key insights

Detailed statistics

Enrollment in elementary schools in Italy 2012-2022

Government expenditure on education as percentage of GDP in Italy 2008-2016

Editor’s Picks Current statistics on this topic

Educational Institutions & Market

Number of students at leading Italian universities 2019/2020

Number of enrolled students in Italy 2020-2021, by field of study

Share of foreign students enrolled at university 2019-2020, by county of origin

Further recommended statistics

Kindergarten.

- Basic Statistic Number of pre-primary schools 2012-2019

- Premium Statistic Number of pre-primary schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

- Basic Statistic Enrollment in kindergartens schools in Italy 2012-2022

- Basic Statistic Enrollment in pre-primary schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

- Premium Statistic Average number of children per class in kindergartens in Italy 2012-2019

Number of pre-primary schools 2012-2019

Number of kindergartens in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Number of pre-primary schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

Number of kindergartens in Italy in the school year 2018/2019, by region

Enrollment in kindergartens schools in Italy 2012-2022

Number of children enrolled in kindergartens in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2022

Enrollment in pre-primary schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

Number of children enrolled in kindergartens in Italy in the school year 2018/2019, by region

Average number of children per class in kindergartens in Italy 2012-2019

Average number of children per class in kindergartens in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Elementary school

- Basic Statistic Number of elementary schools in Italy 2012-2019

- Premium Statistic Number of elementary schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

- Basic Statistic Enrollment in elementary schools in Italy 2012-2022

- Premium Statistic Number of children in elementary schools 2021-2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Average number of children per class in elementary schools in Italy 2012-2019

Number of elementary schools in Italy 2012-2019

Number of elementary schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Number of elementary schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

Number of elementary schools in Italy in the school year 2018/2019, by region

Number of children enrolled in elementary schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2022

Number of children in elementary schools 2021-2022, by region

Number of children enrolled in elementary schools in Italy in the school year 2021-2022, by region

Average number of children per class in elementary schools in Italy 2012-2019

Average number of children per class in elementary schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Middle school

- Basic Statistic Number of middle schools in Italy 2012-2019

- Premium Statistic Number of middle schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

- Basic Statistic Enrollment in middle schools in Italy 2012-2019

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in middle schools in Italy 2021-2022 by region

- Premium Statistic Average number of students per class in middle schools in Italy 2012-2019

Number of middle schools in Italy 2012-2019

Number of middle schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Number of middle schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

Number of middle schools in Italy in the school year 2018/2019, by region

Enrollment in middle schools in Italy 2012-2019

Number of students enrolled in middle schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Enrollment in middle schools in Italy 2021-2022 by region

Number of students enrolled in middle schools in Italy in the school year 2021/2022, by region

Average number of students per class in middle schools in Italy 2012-2019

Average number of students per class in middle schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

High school

- Premium Statistic Number of high schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

- Basic Statistic Enrollment in high schools in Italy 2012-2019

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in upper secondary schools in Italy 2021-2022, by region

- Premium Statistic Average number of students per class in high schools in Italy 2012-2019

- Premium Statistic Distribution of students enrolled in upper secondary schools 2019-2020, by gender

Number of high schools in Italy 2018-2019, by region

Number of high schools in Italy in the school year 2018/2019, by region

Enrollment in high schools in Italy 2012-2019

Number of students enrolled in upper secondary schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Enrollment in upper secondary schools in Italy 2021-2022, by region

Number of students enrolled in high schools in Italy in the school year 2021-2022, by region

Average number of students per class in high schools in Italy 2012-2019

Average number of students per class in high schools in Italy in the school years between 2012 and 2019

Distribution of students enrolled in upper secondary schools 2019-2020, by gender

Distribution of students enrolled in high schools in Italy for the school year 2019/2020, by type of school and gender

- Premium Statistic Number of enrolled students in Italy 2020-2021, by field of study

- Premium Statistic Distribution of enrolled students at Italian universities 2019-2020, by area

- Basic Statistic Number of students at leading Italian universities 2019/2020

- Basic Statistic Number of university students in Italy 2017-2019, by course

- Premium Statistic Enrollment in PhD courses in Italy 2018-2019, by region

- Premium Statistic Share of foreign students enrolled at university 2019-2020, by county of origin

- Basic Statistic Leading big public universities in Italy 2023. by score ranking

Number of students enrolled at university in Italy in the academic year 2020/2021, by field of study

Distribution of enrolled students at Italian universities 2019-2020, by area

Distribution of students enrolled at university in Italy in the academic year 2019/2020, by macro-area of studies

Number of students enrolled at university in Italy in the academic year 2019/2020, by leading universities

Number of university students in Italy 2017-2019, by course

Number of university students in Italy in the academic years between 2017 and 2019, by course

Enrollment in PhD courses in Italy 2018-2019, by region

Number of students enrolled in doctoral courses in Italy in the academic year 2018/2019, by region of the university

Share of foreign students enrolled at university in Italy in the academic year 2019/2020, by most frequent county of origin

Leading big public universities in Italy 2023. by score ranking

Leading big public universities in Italy in 2023, by score ranking

Further reports

Get the best reports to understand your industry.

Mon - Fri, 9am - 6pm (EST)

Mon - Fri, 9am - 5pm (SGT)

Mon - Fri, 10:00am - 6:00pm (JST)

Mon - Fri, 9:30am - 5pm (GMT)

- Profile of Italy

- History Overview

- Destruction of Pompei

- Etruscans in Italy

- Roman Empire

- Greeks in Italy

- Normans in Italy

- Aragons in Italy

- Moors in Italy

- Napoleon in Italy

- Risorgimento

- Italian National Anthem

- Italian Royal Family

- Italian Fascism

- Italian immigration crisis

- Amerigo Vespucci

- Benito Mussolini

- Cesare Borgia

- Christopher Columbus

- Giacomo Casanova

- Giuseppe Garibaldi

- Julius Caesar

- Lucrezia Borgia

- Niccolò Machiavelli

- Antonio Segni

- Carlo Ciampi

- Enrico De Nicola

- Francesco Cossiga

- Giorgia Meloni

- Giorgio Napolitano

- Giovanni Gronchi

- Giovanni Leone

- Giuseppe Saragat

- Luigi Einaudi

- Oscar Luigi Scalfaro

- Sandro Pertini

- Sergio Mattarella

- Silvio Berlusconi

- Giuseppe Arcimboldo

- Leonardo da Vinci

- Michelangelo

- Alessia Gazzola

- Dante Alighieri

- Elena Ferrante

- Giuseppe T. di Lampedusa

- Grazia Deledda

- Umberto Eco

- Andrea Palladio

- Carlo Scarpa

- Renzo Piano

- Andrea Bocelli

- Antonio Stradivari

- Giacomo Puccini

- Giuseppe Verdi

- Luciano Ligabue

- Luciano Pavarotti

- Vincenzo Bellini

- Federico Fellini

- Marcello Mastroianni

- Monica Bellucci

- Silvana Pampanini

- Sophia Loren

- Alessandro Volta

- Antonio Meucci

- Galileo Galilei

- Guglielmo Marconi

- Margherita Hack

- Maria Montessori

- St Francis of Assisi

- St Valentine

- Alberto Ascari

- Alberto Tomba

- Fabio Fognini

- Flavia Pennetta

- Francesco Totti

- Gianluigi Buffon

- Jannik Sinner

- Matteo Berrettini

- Nino Farina

- Simone Velasco

- Sofia Goggia

- Valentino Rossi

- Chiara Ferragni

- Gianluca Vacchi

- Giovanni Brusca

- Italian Army

- Italian Airforce

- Italian Navy

- Italian Coastguard

- Carabinieri

- Government overview

- Prime Minister

- The First Republic

- The 'Years of Lead'

- Tangentopoli & Mani Puliti

- The Second Republic

- Carlo Azeglio Ciampi

- Political Parties in Italy

- Partito Democratico

- Forza Italia

- Movimento Cinque Stelle

- Fratelli d'Italia

- Immigration Crisis

- Italian Local Government

- Italian Police

- Fire Service

- Civil Protection

- Social Care

- Energy in Italy

- Water in Italy

- Internet in Italy

- Mafia - Cosa Nostra

- Falcone and Borsellino

- Mafia - Camorra

- Mafia - Ndrangheta

- John Paul Getty III

- Mafia - Sacra Corona Unita

- Media Overview

- The Italian Economy

- Italy is the next market

- Artistry of Italian Leather

- Artistry of Italian Ceramics

- Artistry of Murano Glass

- Lamborghini

- Dolce & Gabbana

- Giorgio Armani

- Perini Navi

- Italian Top Unesco Sites

- Italian Top Geographical Features

- Italian Top Historical Events

- Italian Top Cultural Developments

- Italian Top Scientific Discoveries

- Italian Top Fashion Contributions

- Regions of Italy

- Emilia Romagna

- Friuli-Venezia Giulia

- Trentino-Alto Adige

- Chieti (CH)

- L'Aquila (AQ)

- Pescara (PE)

- Teramo (TE)

- Matera (MT)

- Potenza (PZ)

- Catanzaro (CZ)

- Cosenza (CS)

- Crotone (KR)

- Reggio Calabria (RC)

- Vibo Valentia (VV)

- Avellino (AV)

- Benevento (BN)

- Caserta (CE)

- Napoli (NA)

- Salerno (SA)

- Bologna (BO)

- Ferrara (FE)

- Forlì-Cesena (FC)

- Modena (MO)

- Piacenza (PC)

- Ravenna (RA)

- Reggio Emilia (RE)

- Rimini (RN)

- Gorizia (GO)

- Pordenone (PN)

- Trieste (TS)

- Frosinone (FR)

- Latina (LT)

- Viterbo (VT)

- Genova (GE)

- Imperia (IM)

- La Spezia (SP)

- Savona (SV)

- Bergamo (BG)

- Brescia (BS)

- Cremona (CR)

- Milano (MI)

- Mantova (MN)

- Monza e della Brianza (MB)

- Sondrio (SO)

- Varese (VA)

- Ancona (AN)

- Ascoli Piceno (AP)

- Macerata (MC)

- Pesaro e Urbino (PU)

- Campobasso (CB)

- Isernia (IS)

- Alessandria (AL)

- Biella (BI)

- Novara (NO)

- Torino (TO)

- Verbano-Cusio-Ossola (VB)

- Vercelli (VC)

- Barletta-Andria-Trani (BT)

- Brindisi (BR)

- Foggia (FG)

- Taranto (TA)

- Cagliari (CA)

- Carbonia-Iglesias (CI)

- Medio Campidano (MD/VS)

- Ogliastra (OG)

- Olbia-Tempio (OT)

- Oristano (OR)

- Sassari (SS)

- Agrigento (AG)

- Caltanissetta (CL)

- Catania (CT)

- Messina (ME)

- Palermo (PA)

- Ragusa (RG)

- Siracusa (SR)

- Trapani (TP)

- Bolzano (BZ)

- Trento (TN)

- Arezzo (AR)

- Firenze (FI)

- Grosseto (GR)

- Livorno (LI)

- Massa-Carrara (MS)

- Pistoia (VC)

- Perugia (PG)

- Belluno (BL)

- Padova (PD)

- Rovigo (RO)

- Treviso (TV)

- Venezia (VE)

- Verona (VR)

- Vicenza (VI)

- Reggio Calabria

- Finale Ligure

- Ascoli Piceno

- Alberobello

- Santa Maria Navarrese

- Porto Ercole

- Porto Santo Stefano

- Abruzzo, Lazio e Molise

- Alta Murgia

- Appennino Lucano

- Appennino Tosco-Emiliano

- Archipelago di La Maddalena

- Archipelago Toscano

- Cilento, Vallo di Diano e Alburni

- Cinque Terre

- Dolomiti Bellunesi

- Foreste Casentinesi

- Gran Paradiso

- Gran Sasso e Monti della Laga

- Monti Sibillini

- Orosei e del Gennargentu

- Pantelleria

- The Northern Lakes - Overview

- Lake Bolseno

- Lake Bracciano

- Lake Lugano

- Lake Maggiore

- Lake Trasimeno

- Aegadian islands

- Aeolian Islands

- Pelagie islands

- Phlegraean Islands

- Pontine Islands

- Tremiti Islands

- Herculaneum

- Roman Forum

- Valley of the Temples

- Castel Savoia

- Basilicata Gallery

- Lake Laudemio

- Bourbon Tunnel

- Caserta Palace

- Castello di Miramare

- Fusine Lakes

- Altare della Patria

- Parco dei mostri

- Ponte Fabricio

- Spanish Square

- Tivoli Gardens

- Trevi Fountain

- Trinità dei Monti

- Genoa Aquarium

- Scaligero Castle

- Lake Pilato

- Malacological Museum

- Tempio de Valadier

- Archipelago di la Maddalena

- Costa Smeralda

- Sicily Gallery

- Chiantishire

- Leaning Tower Pisa

- Pozzo San Patrizio

- Grand Canal

- Saint Mark's Basilica

- Venice Gallery

- Geography of Italy

- Autumn in Italy

- Climate Change

- Spring in Italy

- Summer in Italy

- Winter in Italy

- Campi Flegrei

- Earthquakes

- Mount Stromboli

- Mount Vesuvius

- Bougainvillea

- Oleander Tree

- Strawberry Tree

- Marsican Brown Bear

- Italian Wolf

- Bottlenose Dolphin

- Italian Golden Eagle

- Italian Golden Oriole

- Italian Red Kite

- Pink Flamingo

- Italian Sparrow

- Italian Snakes Overview

- Italian Wall Lizard

- Italian Green Turtle

- Praying Mantis

- Carpenter Bee

- Campari Wasp

- Italian Culture

- Etruscan Influence

- Greek Influence

- Roman influence

- Norman Influence

- Aragonese Influence

- Moorish Influence

- Renaissance

- Italian Art

- Italian Literature

- Italian Classical Music

- Italian Opera

- Italian Fashion

- Classical Architecture

- Baroque Architecture

- Modern Architecture

- Commedia dell'arte

- A List of Events Calendar Full

- Viareggio Carnival

- Venice Carnival

- Festival of San Remo

- Venice Film Festival

- Scoppio del Carro

- Festival of Saint Efisio

- Calcio Fiorentino

- Umbria Jazz Festival

- Wine & Taranta Festival

- Pinacoteca di Brera

- Uffizi Gallery

- Alfa Romeo - Parking

- Barilla - Al Bronzo

- Barilla - Masters of Pasta

- Birra Moretti - Zero

- Coop - Cambiare il mondo

- D&G - A lover's story in Rome

- D&G - Dolce Rosa Excelsa

- D&G - Family

- D&G - Pour Femme & Homme

- Fiat 500 - The Italians are coming

- Ichnusa TV Commercial

- Idealista - Mi Raccomando

- Italian Army Recruitment

- Maserati MC20 Cielo

- Sardinia TV Commercial

- A un passo dalla luna

- Chiamami Per Nome

- Movimento Lento

- Non è Detto

- Notti di Luna

- Un Bacio All'Improvviso

- Una Volta Ancora

- Vivo per lei

- Zitti e Buoni

- Italian Sport

- Motorcycle Racing

- Stadio Olimpico

- Mille Miglia

- Giro d'Italia

- Italy wins curling gold

- Italy wins gold in Rhythmic Gymnastics

- Luna Rossa Americas Cup Trials

- Visiting Italy

- Getting Around

- Italian Buses

- Italian Car Hire

- Italian Ferries

- Italian Motorways

- Italian Scooter Hire

- Italian Trains

- Useful Phrases

- Walking in Italy

- Cycling in Italy

- Best things to do in Florence

- Best things to do in Naples

- Best things to do in Rome

- Best things to do in Venice

- Where to stay

- ABC - Tuscany

- ABC - Liguria

- Scuola Dante Alighieri - Marche

- Terramare - Tuscany

- Conte Ruggiero - Calabria

- Molise Italian Studies - Molise)

- Italian in the Alps - Aosta

- Italian Lakes

- Alberobello Video

- Lucca Video

- Maratea Cristo Video

- Matera Video

- Mount Vesuvius Video

- Palmarola Video

- Ponza Video

- Procida Video

- Punta Campanella Video

- Sardinia Beaches Video

- Taormina Video

- The Amalfi Drive Video

- Tropea Video

- Living in Italy

- Stunning Italian Properties for Sale

- Finding Your Dream Home in Italy

- The Buying Process

- Accessing Italian Healthcare

- Accessing Italian Schooling

- Under a Sardinian Sky

- Bella Figura

- Drive Yourself Crazy!

- Give me a break!

- Grazie Giving

- Homicide by Hospitality

- In My Best Italian

- Superstitions

- Driving in Naples

- Ferragni-Fedez celebrity wedding

- Flight of the angel

- Frecce Tricolore

- Gran Caffè Gambrinus

- High Tide Venice

- La Pignasecca

- Palio video

- Pizza Making Video

- Pizzicarella

- Socially distanced tennis - 01

- Socially distanced tennis - 02

- The 'Vendemmia'

- Vespa trip through Tuscany

- Viareggio Carnival Video

- Italian Food

- Anelletti al Forno alla Siciliana

- Bistecca alla Valdostana

- Bruschette al pomodoro

- Bucatini all'amatriciana

- Cacio e Pepe

- Conchiglie con merluzzo

- Crema di Zucca

- Fagioli al pomodoro

- Fritto Misto

- Insalata Caprese

- Insalata di rucola, pere e noci

- Lenticchie in umido

- Palle di Neve

- Pasta alla Norma

- Pasta Arrabbiata

- Pasta con limone e verdure

- Pasta Sorrentina

- Peach Tiramisu

- Pennette al forno con mozzarella

- Pollo agli agrumi

- Pollo alla Marengo

- Polpette al sugo

- Ragù alla Bolognese

- Risotto agli asparagi

- Risotto alla Milanese

- Risotto con limone e fagioli verdi

- Risotto con piselli e menta

- Spaghetti alle Vongole

- Spaghetti Carbonara

- Spaghetti con Camoscio d'Oro

- Spaghetti con pecorino

- Spaghetti con pesto e pomodoro

- Strudel di mele

- Stufato di agnello alla Romana

- Tagliatelle con cotto e piselli

- Torta di mele

- Balsamic Vinegar

- Dried Pasta

- Fontina Cheese

- Gorgonzola Cheese

- Mozzarella Cheese

- Pane Carasau

- Parmesan Cheese

- Peperoncino

- Italian Wine

- Marsala Wine

Education in Italy

Free state education is available to children of all nationalities who are residents of Italy. Children attending the Italian education system can start with the Scuola dell'Infanzia also known as Scuola Materna (nursery school), which is non-compulsory, from the age of three. Every child is entitled to a place.

Scuola Primaria (Primary School)

At age six, children start their formal, compulsory education with the Scuola Primaria, also known as Scuola Elementare (Primary School). In order to comply with a European standard for school leaving age, it is possible to enter the Scuola Primaria at any time after the age of five and a half. At Scuola Primaria children learn to read, write and study a wide range of subjects including maths, geography, Italian, English and science. They also have music lessons, computer studies and social studies. Religious instruction is optional. Scuola Primaria lasts for five years. Classes are small, containing between 10 and 25 children. Pupils no longer take a leaving exam at the Scuola Primaria. At the age of eleven, they begin their Secondary education.

Scuola Media (Middle School) or Scuola Secondaria di Primo Grado (First Grade Secondary School)

All children aged between eleven and fourteen must attend the Scuola Secondaria di Primo Grado (First Grade Secondary School). Students must attend at least thirty hours of formal lessons per week, although many schools provide additional activities in the afternoons, such as computer studies, music lessons and sports activities. Formal lessons cover a broad range of subjects following a National Curriculum set by the Ministero della Pubblica Istruzione, MPI (Ministry of Public Education). At the end of each term, students receive a school report. At the end of the third year, students sit for a written exam in the subjects of Italian, mathematics, science and a foreign language. There is an oral examination of the other subjects. Successful students are awarded the Licenza di Scuola Media (Licenza Media). They then move onto the Scuola Secondaria di Secondo Grado (Second Grade Secondary School)

Scuola Superiore (High School) or Scuola Secondaria di Secondo Grado (Second Grade Secondary School)

There are two types of Scuola Secondaria di Secondo Grado in Italy: the Liceo (like a British grammar school), which is more academic in nature, and an Istituto, which is essentially a vocational school . For the first two years, all students use the same state-mandated curriculum of Italian language and literature, science, mathematics, foreign language, religion, geography, history, social studies and physical education. Specialised courses called 'Indirizzi' begin in the third year.

Types of Italian High Schools

Liceo classico (classical high school).

This lasts for five years and prepares the student for university-level studies. Latin, Greek and Italian literature form an important part of the curriculum. During the last three years, Philosophy and History of Art are also studied. This is usually the period when students start noticing that help with assignments wouldn't hurt. So, they search for different ways to manage their homework.

Liceo Scientifico (Scientific High School)

This lasts for five years with an emphasis on Physics, Chemistry and Natural Sciences. The student also continues to study Latin and one modern language.

Liceo Artistico (Fine Arts High School)

Studies can last four to five years and prepare for university studies in Painting, Sculpture or Architecture.

Istituto Magistrale (Teacher Training School)

Studies last for five years and prepare future primary school teachers. There is also a three-year training course for nursery school teachers, but this diploma does not entitle students to then enrol at a university.

Studies last three years and prepare for work within an artistic field and leading to an arts qualification (diploma di Maestro d'Arte)

Istituti Tecnici (Technical Institutes)

Studies last five years and prepare for both university studies and for a vocation. There is a majority of technical school students who prepare students to work in a technical or administrative capacity in agriculture, industry or commerce.

Istituti Professionali (Professional Institutes)

These studies lead, in three or five years, to the achievement of a vocational qualification. In order to receive the Diploma di Scuola Superiore, also known as the Diploma di Maturità (Secondary school diploma), students must pass written and oral exams. The first written exam requires an essay written in Italian, on an aspect of Literature, History, Society or Science.

The second written exam requires the student to write a paper relating to their chosen specialisation. The third exam is more general and includes questions regarding contemporary issues and the student's chosen foreign language.

After completing the written exams, students must take an oral exam in front of a board of six teachers. This exam covers aspects of their final year at school. Successful students receive various types of diplomas according to the type of school attended. The Diploma di Scuola Superiore is generally recognised as a university entrance qualification, although some universities have additional entrance requirements.

University is available to all students if they have completed five years of secondary school and received an upper secondary school diploma. It is possible for students who have attended vocational schools to attend university. If a student attended a four-year secondary school program, an additional year of schooling is necessary to qualify for university.

Those attending university after completing their Diploma di Scuola Superiore go for three years (four years for teaching qualifications) to achieve their Laurea (Bachelor's Degree).

University is divided into three cycles:

First cycle - ‘lauria triennale’.

This lasts for three years. Students can choose from a diverse range of universities such as scientific departments, humanities (Literatures, Philosophy) or technical (Architecture, Engineering)

Second Cycle - ‘Lauria Magistrale’ or ‘Specialistica’

This is two years and builds on the student’s first cycle of study. Some courses, however, take five years: typically, Law, Pharmacy, Architecture). Medical school takes six years.

Third Cycle

This is only for the most ambitious students. This is offered as a ‘master’ (a short course building on the first two cycles) or ‘doctoral’ (theoretical courses for those heading into a career in academia or research)

Vocational education is called the Formazione Professionale. The first part of this lasts for three years, after which they are awarded the Qualifica Professionale. The second part, which lasts for a further two years, leads to the Licenza professionale also known as the Maturità professionale.

Enrolling in an Italian school

The Best Italian Handmade Gifts Direct From Italy

More Details

Dani Milazzo

All about Italian Citizenship and Culture

Exploring the Italian Education System: A Comprehensive Guide

Introduction

The education system in Italy is one of the oldest and most respected in the world, with a rich history dating back to the medieval era. The Italian educational system has been around for centuries, and it has evolved throughout the years, adapting to the changing needs of society. Today, it is a highly structured and organized system that provides students with a well-rounded education that prepares them for both academic and career success.

Italy has a strong emphasis on education, and this is evident in the quality of its schools and universities. Italian education is not just about acquiring knowledge, but also about personal growth, cultural enrichment, and social development. Students are encouraged to explore their interests and passions while also learning about the world around them.

If you are interested in learning more about the Italian education system, this blog post is for you. We’ll take a deep dive into the Italian education system, exploring everything from its structure and organization to its unique teaching methods and cultural significance.

The Structure and Organization of the Italian Education System

The Italian education system is divided into three main levels: primary, secondary, and tertiary education. Primary education is mandatory and is typically completed between the ages of 6 and 11. Secondary education is divided into two levels: lower secondary and upper secondary. Lower secondary education is mandatory and is typically completed between the ages of 11 and 14. Upper secondary education is not mandatory, but it is required for students who wish to attend university.

Italian universities are part of the tertiary education system and are divided into two main types: universities and non-university institutions. Universities offer a wide range of degree programs, including bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees. Non-university institutions, on the other hand, offer vocational and professional training programs.

Unique Teaching Methods in Italian Education