Picture Theory

Essays on verbal and visual representation.

W. J. T. Mitchell

462 pages | 79 halftones | 6 x 9 | © 1994

Art: Art Criticism

- Table of contents

- Author Events

- Related Titles

Table of Contents

College Art Association: Charles Rufus Morey Award Won

The University of Chicago Press: Gordon J. Laing Award Won

Be the first to know

Get the latest updates on new releases, special offers, and media highlights when you subscribe to our email lists!

Sign up here for updates about the Press

Examples of Visual Rhetoric: The Persuasive Use of Images

Glossary of Grammatical and Rhetorical Terms

Zsolt Hlinka / Getty Images

- An Introduction to Punctuation

- Ph.D., Rhetoric and English, University of Georgia

- M.A., Modern English and American Literature, University of Leicester

- B.A., English, State University of New York

Visual rhetoric is a branch of rhetorical studies concerned with the persuasive use of images, whether on their own or in the company of words .

Visual rhetoric is grounded in an expanded notion of rhetoric that involves "not only the study of literature and speech , but of culture, art, and even science" (Kenney and Scott in Persuasive Imagery , 2003).

Examples and Observations

"[W]ords and how they're gathered on a page have a visual aspect of their own, but they may also interact with nondiscursive images such as drawings, paintings, photographs, or moving pictures. Most advertisements, for instance, use some combination of text and visuals to promote a product for service. . . . While visual rhetoric is not entirely new, the subject of visual rhetoric is becoming increasingly important, especially since we are constantly inundated with images and also since images can serve as rhetorical proofs ." (Sharon Crowley and Debra Hawhee, Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students . Pearson, 2004

"Not every visual object is visual rhetoric. What turns a visual object into a communicative artifact--a symbol that communicates and can be studied as rhetoric--is the presence of three characteristics. . . . The image must be symbolic, involve human intervention, and be presented to an audience for the purpose of communicating with that audience." (Kenneth Louis Smith, Handbook of Visual Communication . Routledge, 2005)

A Public Kiss

"[S]tudents of visual rhetoric may wish to consider how doing certain deeds expresses or conveys varied meanings from the perspectives of diverse participants or onlookers. For example, something as apparently simple as a public kiss can be a greeting between friends, an expression of affection or love, a featured symbolic act during a marriage ceremony, a taken-for-granted display of privileged status, or an act of public resistance and protest defying discrimination and social injustice. Our interpretation of the meaning of the kiss will depend on who performs the kiss; its ritual, institutional, or cultural circumstances; and the participants' and onlookers' perspectives." (Lester C. Olson, Cara A. Finnegan, and Diane S. Hope, Visual Rhetoric: A Reader in Communication and American Culture . Sage, 2008)

The Grocery Store

"[T]he grocery store--banal as it may be--is a crucial place for understanding everyday, visual rhetoric in a postmodern world." (Greg Dickinson, "Placing Visual Rhetoric." Defining Visual Rhetorics , ed. by Charles A. Hill and Marguerite H. Helmers. Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004)

Visual Rhetoric in Politics

"It is easy to dismiss images in politics and public discourse as mere spectacle, opportunities for entertainment rather than engagement, because visual images transfix us so readily. The question of whether a presidential candidate wears an American flag pin (sending a visual message of patriotic devotion) can triumph over real discussion of issues in today's public sphere. Similarly, politicians are at least as likely to employ managed photo opportunities to create an impression as they are to speak from the bully pulpit with facts, figures, and rational arguments . In heightening the value of the verbal over the visual, sometimes we forget that not all verbal messages are rational, as politicians and advocates also speak strategically with code terms, buzz words , and glittering generalities." (Janis L. Edwards, "Visual Rhetoric." 21st Century Communication: A Reference Handbook , ed. by William F. Eadie. Sage, 2009)

"In 2007, conservative critics assailed then candidate Barack Obama for his decision not to wear an American flag pin. They sought to frame his choice as evidence of his presumed disloyalty and lack of patriotism. Even after Obama explained his position, the criticism persisted from those who lectured him on the importance of the flag as a symbol." (Yohuru Williams, "When Microaggressions Become Macro Confessions." Huffington Post , June 29, 2015)

Visual Rhetoric in Advertising

"[A]dvertising constitutes a dominant genre of visual rhetoric . . . . Like verbal rhetoric, visual rhetoric depends on strategies of identification ; advertising's rhetoric is dominated by appeals to gender as the primary marker of consumer identity." (Diane Hope, "Gendered Environments," in Defining Visual Rhetorics , ed. by C. A. Hill and M. H. Helmers, 2004)

- What Is an Icon in Rhetoric and Popular Culture?

- Visual Metaphor

- Feminist Rhetoric

- Persuasion and Rhetorical Definition

- Definition and Examples of Ethos in Classical Rhetoric

- Understanding the Use of Language Through Discourse Analysis

- Critical Analysis in Composition

- Invented Ethos (Rhetoric)

- Exigence in Rhetoric

- Constraints: Definition and Examples in Rhetoric

- The Rhetorical Canons

- Definition and Examples of the New Rhetorics

- Situated Ethos in Rhetoric

- What is Direct Address in Grammar and Rhetoric?

- What Is a Message in Communication?

- Definition and Examples of Composition-Rhetoric

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How and When to Use Images in an Essay

3-minute read

- 15th December 2018

Pages of text alone can look quite boring. And while you might think that ‘boring’ is normal for an essay, it doesn’t have to be. Using images and charts in an essay can make your document more visually interesting. It can even help you earn better grades if done right!

Here, then, is our guide on how to use images in an academic essay .

How to Use Images in an Essay

Usually, you will only need to add an image in academic writing if it serves a specific purpose (e.g. illustrating your argument). Even then, you need to make sure images are presently correctly. As such, try asking yourself the following questions whenever you add an image in an essay:

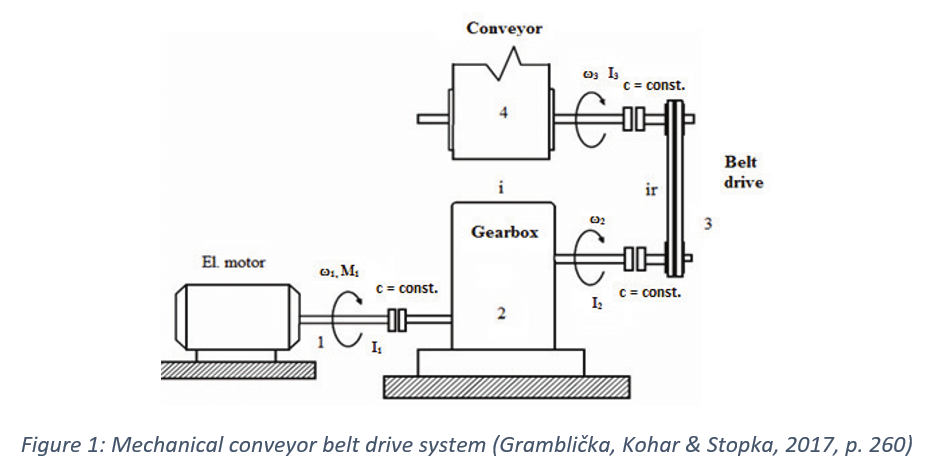

- Does it add anything useful? Any image or chart you include in your work should help you make your argument or explain a point more clearly. For instance, if you are analysing a film, you may need to include a still from a scene to illustrate a point you are making.

- Is the image clearly labelled? All images in your essay should come with clear captions (e.g. ‘Figure 1’ plus a title or description). Without these, your reader may not know how images relate to the surrounding text.

- Have you mentioned the image in the text? Make sure to directly reference the image in the text of your essay. If you have included an image to illustrate a point, for instance, you would include something along the lines of ‘An example of this can be seen in Figure 1’.

The key, then, is that images in an essay are not just decoration. Rather, they should fit with and add to the arguments you make in the text.

Citing Images and Illustrations

If you have created all the images and charts you want to use in your essay, then all you need to do is label them clearly (as described above). But if you want to use an image found somewhere else in your work, you will need to cite your source as well, just as you would when quoting someone.

The exact format for this will depend on the referencing system you’re using. However, with author–date referencing, it usually involves giving the source author’s name and a year of publication:

In the caption above, for example, we have cited the paper containing the image and the page it is on. We would then need to add the paper to the reference list at the end of the document:

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Gramblička, S., Kohar, R., & Stopka, M. (2017). Dynamic analysis of mechanical conveyor drive system. Procedia Engineering , 192, 259–264. DOI: 10.1016/j.proeng.2017.06.045

You can also cite an image directly if it not part of a larger publication or document. If we wanted to cite an image found online in APA referencing , for example, we would use the following format:

Surname, Initial(s). (Role). (Year). Title or description of image [Image format]. Retrieved from URL.

In practice, then, we could cite a photograph as follows:

Booth, S. (Photographer). (2014). Passengers [Digital image]. Retrieved from https://www.flickr.com/photos/stevebooth/35470947736/in/pool-best100only/

Make sure to check your style guide for which referencing system to use.

Need to Write An Excellent Essay?

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Get help from a language expert. Try our proofreading services for free.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

(Stanford users can avoid this Captcha by logging in.)

- Send to text email RefWorks EndNote printer

Picture theory : essays on verbal and visual representation

Available online, at the library.

Art & Architecture Library (Bowes)

More options.

- Find it at other libraries via WorldCat

- Contributors

Description

Creators/contributors, contents/summary, bibliographic information, browse related items.

- Stanford Home

- Maps & Directions

- Search Stanford

- Emergency Info

- Terms of Use

- Non-Discrimination

- Accessibility

© Stanford University , Stanford , California 94305 .

Department of Art History

Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation

W.J.T. Mitchell

From the publisher :

What precisely, W. J. T. Mitchell asks, are pictures (and theories of pictures) doing now, in the late twentieth century, when the power of the visual is said to be greater than ever before, and the "pictorial turn" supplants the "linguistic turn" in the study of culture? This book by one of America's leading theorists of visual representation offers a rich account of the interplay between the visible and the readable across culture, from literature to visual art to the mass media.

Publications

Charles Ray: Adam and Eve

Seeing Race Before Race (with Noémie Ndiaye)

Unseen Art: Making, Vision, and Power in Ancient Mesoamerica

Houses to Die In and Other Essays on Art

Divine Inspiration in Byzantium: Notions of Authenticity in Art and Theology.

Radical Form: Modernist Abstraction in South America

Building with Paper. The Materiality of Renaissance Architectural Drawings , eds. D. Donetti and C. Rachele

The Allure of Matter: Material Art from China (with Orianna Cacchione)

Bisa Butler: Portraits

Francesco da Sangallo e l'identità dell'architettura toscana

“Introduction: Inventing the Nova Reperta,” in Renaissance Invention: Stradanus’s Nova Reperta

First Class: Teaching Chinese Art History at Harvard University and the University of Chicago

Vessels: The Object as Container

A Forest of Symbols: Art, Science, and Truth in the Long Nineteenth Century

Art & Archaeology of the Greek World: A New History, c. 2500–c. 150 BCE

Conditions of Visibility

Pindar, Song, and Space: Towards a Lyric Archaeology

Among Others: Blackness at MoMA

A Companion to Modern and Contemporary Latin American and Latino Art

To Describe a Life: Notes from the Intersection of Art and Race Terror

Architecture and Dystopia

Il'ia i Emiliia Kabakovy

Ellsworth Kelly, Color Panels for a Large Wall

On Art: Ilya Kabakov

Scale & the Incas

Art in Chicago: A History from the Fire to Now

Comparativism in Art History

Giuliano da Sangallo: Disegni degli Uffizi

Memory in Motion. Archives, Technology and the Social

The Ark of Civilization

The Poetics of Late Latin Literature

The New World in Early Modern Italy, 1492-1750 (with Elizabeth Horodowich), Cambridge University Press, 2017

1971: A Year in the Life of Color

Ugliness: The Non-Beautiful in Art and Theory

The Autobiography of Video. The Life and Times of a Memory Technology

Zooming In: Histories of Photography in China

The Noisy Renaissance: Sound, Architecture, and Florentine Urban Life

Un/Translatables: New Maps for Germanic Literatures

Art History and Emergency

Imagining the Americas in Medici Florence

Poetry and the Thought of Song in Nineteenth-Century Britain

Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics

Antiquity, Theatre, and the Painting of Henry Fuseli

The Art of the Yellow Springs: Understanding Chinese Tombs

«Di molte figure adornato»: L’Orlando furioso nei cicli pittorici fra Cinque e Seicento. Milano: Officina Libraria, 2015.

Making Modern Japanese-Style Painting: Kano Hogai and the Search for Images

Aesthetics of Ugliness: A Critical Edition

The Murals of Cacaxtla: The Power of Painting in Ancient Central Mexico

The Art of Conversion: Christian Visual Culture in the Kingdom of Kongo

En Guerre: French Illustrators and World War I

Contemporary Chinese Art

Building a Sacred Mountain: The Buddhist Architecture of China's Mount Wutai

Raoul Hausmann et Les Avant-Gardes

Italian Master Drawings from the Princeton University Art Museum (Laura Giles and Claire Van Cleave), Yale University Press, 2014

Art and Rhetoric in Roman Culture,

Kunst und Archäologie der griechischen Welt: Von den Anfängen bis zum Hellenismus

The Spectacle of the Late Maya Court: Reflections on the Murals of Bonampak

Occupy: Three Inquiries in Disobedience

The Emergence of the Classical Style in Greek Sculpture

Sabine Moritz: Limbo 2013

Capital Culture : J. Carter Brown, the National Gallery of Art, and the Reinvention of the Museum Experience

Fugitive Objects: Sculpture and Literature in the German Nineteenth Century

Seeing Through Race

Awash in Color: French and Japanese Prints

Seeing Madness, Insanity, Media, and Visual Culture

A Story of Ruins: Presence and Absence in Chinese Art and Visual Culture

Art & Archaeology of the Greek World: A New History, c. 2500 - c. 150 BCE

Vision and Communism

Translating Truth: Ambitious Images and Religious Knowledge in Late Medieval France and England

Life, Death and Representation: Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi

Cloning Terror: the War of Images 9/11 to the Present

A Field Guide to a New Metafield: Bridging the Humanities-Neurosciences Divide

Saints: Faith at the Borders

Éfficacité/Efficacity: How to Do Things with Words and Images?

Wonder, Image, & Cosmos in Medieval Islam

Bild und Text im Mittelalter (Sensus, 2)

Contemporary Chinese Art: Primary Documents

Critical Terms for Media Studies

The Experimental Group: Ilya Kabakov, Moscow Conceptualism, Soviet Avant-Gardes

Reinventing the Past: Archaism and Antiquarianism in Chinese Art and Visual Culture

Gerhard Richter: Early Work 1951-1972

Blinky Palermo: Abstraction of an Era

Making History: Wu Hung on Contemporary Art

Elective Affinities: Testing Word and Image Relationships

Veiled Brightness: A History of Ancient Maya Color

Looking and Listening in 19th Century France (With Anne Leonard)

The Chicagoan: A Lost Magazine of the Jazz Age

Poetry and the Pre-Raphaelite Arts: William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti

The Writing of Modern Life: the Etching Revival in France, Britain, and the U.S., 1850-1940

The Late Derrida

How to See a Work of Art in Total Darkness

Echo Objects: The Cognitive Work of Images

Severan Culture

Roman Eyes: Visuality and Subjectivity in Art and Text

On the Style Site: Art, Sociality and Media Culture

What Do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images

Edward Said: Continuing the Conversation

Remaking Beijing: Tiananmen Square and the Creation of a Political Space

Neo Rauch: Renegaten

Die Illustrierten Homilien des Johannes Chrysostomos in Byzanz

Chicago Apartments: A Century of Lakefront Luxury

Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties

Kara Walker: Narratives of a Negress

The Name of the Game: Ray Johnson's Postal Performance

Style and Politics in Athenian Vase Painting: The Craft of Democracy, ca. 530-460 B.C.E.

Landscape and Power

Confronting Identities in German Art: Myths, Reactions, Reflections

Pious Journeys: Christian Devotional Art and Practice in the Later Middle Ages and Renaissance

Stress and Resilience: The Social Context of Reproduction in Central Harlem

Joseph Beuys

The Films of Fritz Lang: Allegories of Vision and Modernity

Exhibiting Experimental Art in China

Wols Photographs

Building Lives: Constructing Rites and Passages;

Legends in Limestone: Lazarus, Gislebertus, and the Cathedral of Autun

Looking to Learn: Visual Pedagogy at the University of Chicago

Visual Analogy: Consciousness as the Art of Connecting

The Last Dinosaur Book: The Life and Times of a Cultural Icon

Embodying Ambiguity: Androgyny and Aesthetics from Winckelmann to Keller

Imperial Rome and Christian Triumph: The Art of the Roman Empire A.D. 100-450

Rural Scenes and National Representation, Britain 1815-1850

The Double Screen: Medium and Representation in Chinese Painting

The Art of Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone: Between Dialect and Language Volume II

The Art of Giovanni Antonio da Pordenone: Between Dialect and Language Volume I

Pissarro, Neo-Impressionism, and the Spaces of the Avant-Garde

Good Looking: Essays on the Virtue of Images

Monumentality in Early Chinese Art and Architecture

Pilgrimage Past and Present: Sacred Travel and Sacred Space in the World Religions

Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity

Artful Science: Enlightenment, Entertainment and the Eclipse of Visual Education

D.W. Griffith and the Origins of American Narrative Film

In the Theater of Criminal Justice: The Palais De Justice in Second Empire Paris

Art and the Public Sphere

Cultural Excursions: Marketing Appetites and Cultural Tastes in Modern America

The Wu Liang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art

Kilowatts and Crisis: Hydroelectric Power and Social Dislocation in Eastern Panama

The Woman Question: Society and Literature in Britain and America, 1837-1883

Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology

Hildegard Auer: A Yearning for Art

Munch: His Life and Work

Ruskin and the Art of the Beholder

On Narrative

The Language of Images

Blake's Composite Art: A Study of the Illuminated Poetry

Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum

The Artist in American Society: The Formative Years, 1790-1860

Body Criticism: Imaging the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine

Meiji Modern: Fifty Years of New Japan

Visual and Spatial Rhetoric: Analyzing Images

Most texts are more than words on a page. Photographs, works of art, graphic novels, political cartoons, computer or video game screens, television or magazine advertisements, webpages, billboards, and more are all texts composed and designed to communicate ideas.

The texts you encounter in college also have visual or spatial components—an author’s profile picture on a publisher’s website, a reporter’s blog with hyperlinks to recommended websites, embedded videos and podcasts, a scientist’s precise figures and tables within a cutting-edge scientific journal, a business person’s PowerPoint presentation to prospective investors, or the photographic forensic evidence a police detective collects during a routine crime scene investigation.

A viewer or reader will come to many substantial conclusions analyzing a visual or spatial text. There often is not a “right” answer as much as a well-supported approach to a possible idea. Each viewer interprets the image separately (Alfano & O’Brien, 2017).

Whatever discipline you study, chances are you’ll come into contact with images, illustrations, and designs that require a sophisticated and close reading, so you may draw conclusions about the text’s rhetorical significance—its argument—that which the text makes the reader understand or believe.

Audience, Context, Subject, and Purpose

Analyzing a text’s rhetorical significance begins with determining the rhetorical situation—how the communication format, be it visual, written, aural, or any other multimodal form, situates itself on four main concepts: the audience, context, subject, and purpose.

Audience : Who is the intended audience for the text, and how do you know?

Context : What historical, sociological, cultural, political, ideological, or genre situations influence the text? What was happening during the time this text was being created?

Subject and Purpose : What is the author expressing? Why do you think her or she is communicating about this particular idea, issue, or concept?

Visual and spatial rhetoric uses images to communicate ideas. What is Figure 1 communicating?

Visual Rhetoric Sample Analysis: “Cake Batter With Eggs”

Note . From Mixing Bowl With Flour and Eggs and Spatula , by Clipart.com, 2015 ( https://www.clipart.com/download.php?iid=1792295&tl=photos ). Copyright 2015 by Clipart.com. Reprinted with permission.

Subject : What the author wants the audience to explore. Example : Homemade cake batter with fresh eggs.

Purpose : Why is the author creating this text? Example : Perhaps the creator of this photograph wanted to document kitchen adventures or she or he may love to bake.

Audience : Who is the author trying to reach? Example : Possibly food lovers who like to see how ingredients morph into baked goods.

Context : What historical or value-based situation surrounds this text? Example : A personal food blog? Perhaps a cooking website? Something fairly contemporary and American given the style of cooking instruments being used (plastic bowl, spatula, and measuring cups (in cups rather than pints or liters used outside the US).

What to Look for in a Visual Text

Next, you’ll want to look at the grounding, color scheme, medium, and typography of the text:

Grounding or the placement of images within a text : What is the most and least prominent element? The first place the eye focuses may seem the most important, but the background may be influencing your understanding of the text as well.

Color scheme, the colors the artist chooses : Blues and greys are associated with water and stone, so they suggest a cooling and calming mood; greens remind people of living plants as well as money, so they can suggest both health and wealth; yellows are commonly used on hospital walls to evoke a softness (in an otherwise noisy environment); and reds express passion as well as anger, creating feelings of energy and excitement.

Medium, the materials the artist chooses : A painter may use watercolor or oil; a sculptor may choose clay, copper, bronze, or iron; a cartoonist may use pencils on paper; and a writer may use a digital medium. The medium can suggest the intended audience as well as the purpose of the communication.

Typography, the appearance of printed characters : What moods do the fonts create?

Typography on a Bakery and Catering Storefront Window

Heading fonts may be different than body text fonts for the purpose of readability. Depending on the intended reader and purpose, fonts may be chosen to express formality or playfulness or to express a particular cultural or historical context.

Visual Rhetoric and Color Theory

Color theory looks at how colors work together to create effective and appealing designs. Certain colors also act symbolically to affect us emotionally.

The color wheel, first developed by Sir Issac Newton, provides a framework for understanding color harmony. The color wheel depicts the primary colors (red, blue, and yellow) and the secondary colors (green, orange, and purple), which are formed from mixing the primary colors. The tertiary colors (red-orange, yellow-orange, red-violet, blue-violet, blue-green, and yellow-green) are formed when primary and secondary colors are mixed.

The Color Wheel

Color harmony suggests that certain colors together create palates that are pleasing to the eye. These color combinations include analogous colors, or any set of three colors that appear next to each other on the color wheel such as blue, blue-green, and green.

Another formula for pleasing color arrangements is to choose complementary colors, or two colors which appear directly opposite each other on the color wheel such as purple and yellow. Finally, a designer may choose to mimic a combination found in nature such as the yellow, red, orange, and brown colors found in autumn foliage.

Image of Markers, Drafting Tools, and Pantone Color Swatches

Color theory also includes the emotional effect of certain colors through natural association and symbolism.

Visual Rhetoric: Analyzing Pictures

When analyzing the rhetorical significance of a photograph, the goal is to uncover its argument. Does the photograph say something about love? Family? Patriotism? Wellness? Success? What happiness is?

In determining the argument, the first elements to analyze are the audience, context, subject, and purpose . Additionally, you’ll want to consider the following:

- Material context : Where was the picture published? Where is it displayed? Is it the original version or a reproduction (as might be the case for artwork and paintings)?

- Rhetorical Stance : What is the point-of-view of the photographer? Is the photographer a participant in the activity or scene being depicted, or is the photographer an observer? Are the subjects in the picture aware that their photo is being taken? Where is the focus of the image?

- Reality or Abstraction : Is the photograph of a realistic scene, or has it been edited into an abstract piece of art? How do the modifications (if any) affect the meaning of the image? Does the editing serve the purpose of making the people in the picture look younger or more attractive than they might be otherwise?

- Caption and Accompanying Text : Does the photo have a title and/or a caption? Does it accompany written text such as on a website, in a newspaper, or in a magazine? How does the photograph support or illustrate the text? How does the text affect the meaning of the picture? The next section of this resource covers images with text in more detail.

Analyzing Pictures

Photographic elements work together to communicate ideas.

Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima, February 23, 1945

Note. From Raising the Flag on Iwo Jima , by Joe Rosenthal, 1945, Archives.gov ( https://unwritten-record.blogs.archives.gov/2015/02/23/raising-the-flag-over-iwo-jima/ ). In the public domain.

Subject or content : The scene or people the photo is depicting. Example : Five marines and a Navy hospital corpsman raising an American flag on top of Mt. Surabachi, Iwo Jima during World War II.

Purpose : Why is the author creating this text? Example : The photographer was from the Associated Press. He was documenting the battle of Iwo Jima during WWII.

Audience : Who is the author trying to reach? Example : The photographer likely intended to reach the American public who revere the American Flag as a symbol of pride and patriotism and who were awaiting news about the progress of the war.

Cultural Context : What is the cultural or historical context of the photograph, and how does that context affect the photograph’s meaning and importance? Example : This photo was taken during the bloodiest battle of WWII when the American public needed reassurance that they were doing the right thing. The photograph was immediately popular and widely reproduced as a message to support the war.

Visual Rhetoric: Images and Text

Authors and designers carefully consider the inclusion and interplay of visual images with text. For example, consider this picture quote from the Purdue Global Facebook page:

Image of Children in the Rain

Note. From A Loving Heart , by Purdue University Global, 2020 ( https://www.facebook.com/PurdueGlobal ). Copyright 2020 by Purdue University Global.

In this example, the image of the children holding hands sharing an umbrella interacts with the quote from Tomas Carlyle (1795-1891): “A loving heart is the beginning of all knowledge.” The text expresses a possible idea behind the image of the children who appear loving. And as this was a Facebook post by a university, the connection to knowledge fits with the context of the webpage.

Consider how your reaction to this picture would be different if the text were removed? What about if the image were removed? Or if the image were changed? These questions are valuable when analyzing and discussing the visual rhetoric of print advertisements, television commercials, websites, and cartoons too.

Visual and spatial texts make arguments, and readers will have different understandings and beliefs about them. Analyzing a text’s subject, purpose, audience, and context, taking into consideration the colors, design, perspective, and the interplay of visuals and language is critical when it comes to developing your own understandings and beliefs and then communicating your own arguments about them.

Alfano, C. & O’Brien, A. (2017). Envision: Writing and researching arguments (5th ed.). Pierson Education. https://bit.ly/32RxV4x

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

- Arts & Photography

- History & Criticism

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } -5% $34.97 $ 34 . 97 FREE delivery Monday, June 3 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select the return method

Save with Used - Very Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $19.88 $ 19 . 88 FREE delivery Tuesday, June 4 on orders shipped by Amazon over $35 Ships from: Amazon Sold by: Haystack Market

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation 1st Edition

Purchase options and add-ons.

- ISBN-10 0226532321

- ISBN-13 978-0226532325

- Edition 1st

- Publisher University of Chicago Press

- Publication date September 1, 1995

- Language English

- Dimensions 8.88 x 6.16 x 0.97 inches

- Print length 462 pages

- See all details

Frequently bought together

Similar items that may deliver to you quickly

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : University of Chicago Press; 1st edition (September 1, 1995)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 462 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0226532321

- ISBN-13 : 978-0226532325

- Item Weight : 1.5 pounds

- Dimensions : 8.88 x 6.16 x 0.97 inches

- #301 in Trade

- #1,402 in Arts & Photography Criticism

- #5,007 in Sociology (Books)

About the author

W. j. thomas mitchell.

Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

Top reviews from other countries

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

University of Notre Dame

Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews

- Home ›

- Reviews ›

Words and Images: An Essay on the Origin of Ideas

Christopher Gauker, Words and Images: An Essay on the Origin of Ideas , Oxford University Press, 2011, 288pp., $65.00 (hbk), ISBN 9780199599462.

Reviewed by Edouard Machery, University of Pittsburgh

Christopher Gauker's new book is a rich and innovative study of the nature of conceptual thought, its relation to language, the relation between concepts and perception, and the place of imagistic thinking in cognition. Many more topics are broached in passing, including the alleged ambiguity of "concept" in psychology and philosophy (contra Machery (2009), this term is used unambiguously to refer to the constituents of judgments), the myth of folk psychology (it is not true that we predict and explain behavior by ascribing beliefs and desires), the proper interpretation of Kant's opaque theory of concepts, the non-conceptual nature of perceptual content, and the nature of meaning (strictly speaking, words don't have any meaning, although we use the word "meaning" to prescribe how words should be used), and the views of many philosophers (Sellars, McDowell, Prinz, Gärdenfors, etc.) and psychologists (Rosch, Mandler, Barsalou, Tversky, etc.) are critically discussed.

Words and Images is divided into a critical and a constructive part. In the critical part (Chapters 1 to 4), Gauker sharply scrutinizes the views about concepts he believes are mistaken, occasionally rescuing an insight from the ruins his criticisms are supposed to leave behind. Chapters 1 and 2 focus on the views that, in different ways, tie together concepts and perception: first, the Lockean view that concepts are abstracted from perceptions, then the Kantian view that concepts are rules of synthesis of perceptions. Chapter 3 examines Churchland's and Gärdenfors's view that concepts are regions of a hyperdimensional mental space. Chapter 4 discusses Sellars's functionalism, Fodor's nativism, and Brandom's normative functionalism.

In the constructive part (Chapters 5 to 8), Gauker develops his own views, starting with the nature of imagistic cognition and its place in cognition (Chapters 5 and 6). Chapter 7 explains how assertions are guided by imagistic representations, while the final chapter defends the identification of conceptual judgments with linguistic assertions in inner speech (which, as Gauker emphasizes, should not be confused with the inner perception of sentences).

The broad outline of Gauker's theory of conceptual thought is familiar: concepts are words, judgments are assertions in inner speech, and there is no conceptual thinking without language. While we've heard that story before, Gauker's remake is worth a detour. This is due in large part to the role played by imagistic cognition. Non-human animals and human beings are hypothesized to possess non-conceptual (in contrast to Gärdenfors's theory), perceptual hyperdimensional mental spaces (think of, e.g., the space of colors), over which similarity measures are defined. (Apparently, we have several such spaces; unfortunately, Gauker does not explain how they are related to one another and how they are organized.) Points in a perceptual space represent perceived or imagined particulars, and their location determines which properties these are represented as possessing. Represented particulars are more or less similar to one another, depending on their distance in these hypothesized perceptual spaces. Causal relations of a limited type (e.g., a billiard ball pushing another one) can also be represented in them. In contrast to particulars and some causal relations, kinds are not represented. For instance, points representing dogs happen to be clustered in the same region of space and to be closer to one another than they are to points representing cats, but their referents are neither represented as dogs nor as forming a kind. Representations of kinds are conceptual, and require a language. Imagistic representations can be more or less accurate, and to that extent they can misrepresent. Endogenously controlled imagistic representations are used to solve many different types of problem. In fact, Gauker goes out of his way to showcase how much can be done with these representations and without concepts -- one of the most interesting aspects of his book. Cognition in non-human animals is exclusively imagistic, and much of human mental life is imagistic too.

Imagistic representations guide the use of words in assertions (including in inner speech) and thus the occurrence of concepts in judgments. Linguistic competence involves being disposed to make various types of assertions in response to various kinds of perceptual representations. Focusing on a simplified language containing atomic (demonstrative + predicate, e.g., "this is red"), disjunctive, and conditional sentences, Gauker maps these kinds of sentences onto different kinds of imagistic representations. Acquiring a language consists in acquiring the relevant dispositions. Perceptions do not provide us with reasons for our judgments (these are not inferred from perceptions, but caused by them), but we are justified in judging the way we do when our judgments are caused by imagistic representations in the right way.

There is much to like in Words and Images . It is ambitious and deals with a fundamental question in the philosophy of mind -- the nature of conceptual thinking. It is full of bold, iconoclastic views (e.g., communication does not consist in conveying thoughts, words do not have any meaning, behavior is not explained by means of belief and desire ascription), detailed arguments for these views and against competing ones, and careful discussion of possible objections. It moves swiftly between philosophical arguments and psychological hypotheses and results, which is very fitting for the topic.

Before focusing on Gauker's positive claims about conceptual thinking, I will first record a minor reservation with the critical part of the book. Gauker sometimes recycles well-known arguments, and the reader who is conversant with the literature on concepts may find some developments a bit slow. More importantly, despite being canonical among philosophers of mind, some of these arguments are poor. For example, it is often said that if concepts were bundles of beliefs, then we could not change our minds (Gauker uses a version of this argument against Gärdenfors). Changing our mind involves having a belief at t 2 that contradicts a belief held at t 1 , which is possible only if we possess the same concept at t 1 and t 2 . But, if concepts are bundles of beliefs and if beliefs change, then we do not possess the same concept at t 1 and t 2 . We can change our mind, and so concepts are not bundles of beliefs. This argument looses its appeal when concepts are viewed as individuals: What makes a concept at t 1 and a concept at t 2 the same concept is the psychological continuity between the bundle of beliefs that constitutes the former and the bundle that constitutes the latter (Machery, 2010 in response to Hill, 2010).

Gauker's positive proposal will probably leave readers unconvinced. Let's focus first on imagistic cognition. As we saw above, imagistic representations do not represent particulars as belonging to kinds. This claim seems to be challenged by the phenomenon of categorical perception -- viz. by the fact that there are boundaries between regions of perceptual spaces such that a pair of points across a boundary is judged to be more dissimilar than a pair of points within a bounded region even when the distance between points is the same for both pairs (e.g., Harnad, 1987; Gauker is aware of this phenomenon, p. 169). Gauker would probably deny that the categorical nature of perception shows that perceptual representations represent kinds. However, this response is unconvincing since the mind treats all the points within bounded regions of some spaces identically: for instance, in the space of phonemes, all r 's are r 's, function identically in speech perception. More generally, as Matthen has convincingly argued (2005), much of perception consists in digitalizing, i.e., in treating diverse things as being the same. Thus, the ventral temporal cortex includes a sequence of representations that forms a hierarchy of invariances, as shown, e.g., by Tanaka's work. Suppose now that perceptual spaces can represent kinds. This does not entail that perception involves concepts, as Gauker notes in a different, but related context (p. 166), but it means that kind cognition does not require a language. And, if kind cognition does not require a language, then one of the important characteristics of concepts (viz. that particulars that belong to their extensions are represented as being in some sense the same) is not language-dependent. This weakens the need for identifying concepts and words.

Second, Gauker is explicit that not all dimensions are innate and that perceptual spaces can acquire new dimensions. But, since their dimensions are necessarily perpetual (they are "dimensions of perceptual variation," p. 95), it is only the looks or appearances of particulars that are represented in perceptual similarity spaces. If perceptual spaces represent only the looks of particulars, there are limitations to what can be done by representing them in perceptual spaces and by computing their similarity. In particular, any evidence in comparative and developmental psychology that behavior depends on treating perceptually dissimilar objects similarly would undermine the role Gauker assigns to imagistic cognition. It would not straightforwardly follow that animals and non-linguistic babies have concepts and thus that concepts are not necessarily words, since a distinct, non-perceptual and non-conceptual kind of representations could be ascribed to them., But this evidence would probably be more easily explained by a proponent of non-linguistic concepts than by Gauker.

Third, the plausibility of Gauker's views depends on his capacity to explain the behavior of non-linguistic animals (non-human animals and babies) by means of his hypothesized perceptual similarity spaces. He dedicates twenty pages to this task (pp.163-183), but his discussion left me unconvinced. The problem is not that it is obviously mistaken. No, the problem with Gauker's exercise in post-hoc explanation is that his theory is vague and makes few clear, specific predictions. As a result, it is largely a matter of ingenuity and imagination to find explanations consistent with it. If Gauker's theory made specific predictions, then it would be quite a feat to show that the behavior of non-human animals and of babies are exactly those that are predicted. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

I will finish with a brief discussion of Gauker's views about how perceptual spaces guide assertions (Chapter 7). Gauker's exposition is puzzling. He apparently views his account as an empirical hypothesis about how concepts are acquired, but it is nothing of the sort. What it is is a speculative description of the target of language and concept acquisition: what one has to learn to be a competent speaker and thinker. But, Gauker has nothing to say about how the dispositions that for him are constitutive of linguistic and conceptual competence are actually acquired. This is particularly damning since one of his key general concerns with other views of concepts is that they cannot explain how concepts are acquired. Similarly, after having read Chapter 7, the reader will have no idea how the relevant dispositions are acquired.

Harnad, S. (1987). Categorical Perception: The Groundwork of Cognition . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hill, C. (2010). "I love Machery's book, but love concepts more." Philosophical Studies , 149, 411-421.

Machery, E. (2009). Doing without Concepts . New York: Oxford University Press.

Machery, E. (2010). "Replies to my critics." Philosophical Studies , 149, 429-436.

Matthen, M. (2005). Seeing, Doing, and Knowing: A Philosophical Theory of Sense Perception . Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Format Images in an Essay

- 5-minute read

- 27th April 2022

Writing an essay ? It may enhance your argument to include some images, as long as they’re directly relevant to the essay’s narrative. But how do you format images in an essay? Read on for tips on inserting and organizing images, creating captions, and referencing.

Inserting Images

To insert an image into the text using Microsoft Word:

● Place the cursor where you want to add a picture.

● Go to Insert > Pictures .

● Click on This Device to add pictures from your own computer or select Online Pictures to search for a picture from the internet.

● Select the image you wish to use and click Insert .

See our companion blog post for further detail on inserting images into documents using Word.

Organizing Images

There are two common methods of organizing images in your essay: you can either place them next to the paragraph where they are being discussed (in-text), or group them all together at the end of the essay (list of figures). It can be clearer to display images in-text, but remember to refer to your university style guide for its specifications on formatting images.

Whichever method you decide upon, always remember to refer directly to your images in the text of your essay. For example:

● An example of Cubism can be seen in Figure 1.

● Cubist paintings have been criticized for being overly abstract (see Figure 1).

● Many paintings of this style, including those by Picasso (Figure 1), are very abstract.

Every image that you include in your essay needs to have a caption. This is so that the reader can identify the image and where it came from. Each caption should include the following:

● A label (e.g., Figure 1 ).

● A description of the image, such as “Picasso’s Guernica ,” or “ Guernica : One of Picasso’s most famous works.”

● The source of the image. Even if you have created the image yourself, you should attribute it correctly (for example, “photo by author”).

Have a look at this example:

Figure 1: Picasso’s Guernica

Photo: Flickr

Here, the image is given both a label and a title, and its source is clearly identified.

Creating Captions Using Microsoft Word

If you are using Word, it’s very simple to add a caption to an image. Simply follow the steps below:

● Click on the image.

● Open the References toolbar and click Insert Caption .

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

● Fill in or select the required details and click OK .

You can also add a caption manually.

Referencing Captions

At this point, you’ll need to refer to your style guide again to check which referencing system you’re using. As mentioned above, all sources should be clearly identified within the caption for the image. However, the format for captions will vary depending on your style guide. Here, we give two examples of common style guides:

- APA 7th Edition

The format for a caption in APA style is as follows:

Note. By Creator’s Initials, Last Name (Year), format. Site Name (or Museum, Location). URL

The image format refers to whether it’s a photograph, painting, or map you are citing. If you have accessed the image online, then you should give the site name, whereas if you have viewed the image in person, you should state the name and location of the museum. The figure number and title should be above the image, as shown:

Figure 1

Note . By P. Picasso (1937), painting. Flickr. https://www.flickr.com/photos/huffstutterrobertl/5257246455

If you were to refer to the image in the text of your essay, simply state the creator’s last name and year in parentheses:

(Picasso, 1937).

Remember that you should also include the details of the image in your reference list .

MLA style dictates that an image caption should be centered, and each figure labeled as “Fig.” and numbered. You then have two options for completing the caption:

1. Follow the Works Cited format for citing an image, which is as follows:

Creator’s Last Name, First Name. “Image Title.” Website Name , Day Month Year, URL.

2. Provide key information about the source, such as the creator, title, and year.

In this case, we have followed option 1:

Fig. 1. Picasso, Pablo. “Guernica.” Flickr , 1937, https://www.flickr.com/photos/huffstutterrobertl/5257246455

When referring to the image in the text of the essay, you need only cite the creator’s last name in parentheses:

And, again, remember to include the image within the Works Cited list at the end of your essay.

Expert Proofreading and Formatting

We hope this guide has left you a little clearer on the details of formatting images in your essays . If you need any further help, try accessing our expert proofreading and formatting service . It’s available 24 hours a day!a

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

- Even more »

Account Options

- Try the new Google Books

- Advanced Book Search

Get this book in print

- Oxford University Press

- Barnes&Noble.com

- Books-A-Million

- Find in a library

- All sellers »

Selected pages

Other editions - View all

Common terms and phrases, about the author (2011), bibliographic information.

- Skip to content

Davidson Writer

Academic Writing Resources for Students

Main navigation

Literary analysis: applying a theoretical lens.

A common technique for analyzing literature (by which we mean poetry, fiction, and essays) is to apply a theory developed by a scholar or other expert to the source text under scrutiny. The theory may or may not have been developed in the service literary scholarship. One may apply, say, a Marxist theory of historical materialism to a novel, or a Freudian theory of personality development to a poem. In the hands of an analyst, another’s theory (in parts or whole) acts as a conceptual lens that when brought to the material brings certain elements into focus. The theory magnifies aspects of the text according to its special interests. The term theory may sound rarified or abstract, but in reality a theory is simply an argument that attempts to explain something. Anytime you go to analyze literature—as you attempt to explain its meanings—you are applying theory, whether you recognize its exact dimensions or not. All analysis proceeds with certain interests, desires, and commitments (and not others) in mind. One way to define the theory—implicit or explicit—that you bring to a text is to ask yourself what assumptions (for instance, about how stories are told, about how language operates aesthetically, or about the quality of characters’ actions) guide your findings. A theory is an argument that attempts to explain something.

Let’s turn again to the insights about using theories to analyze literature provided in Joanna Wolfe’s and Laura Wilder’s Digging into Literature: Strategies for Reading, Analysis, and Writing (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2016).

Here’s a brief example of a writer using a theoretical text as a lens for reading the primary text :

In her book, The Second Sex , the feminist philosopher Simone de Beauvoir describes how many mothers initially feel indifferent toward and estranged from their new infants, asserting that though “the woman would like to feel that the new baby is surely hers as is her own hand,. . . she does not recognize him because. . .she has experienced her pregnancy without him: she has no past in common with this little stranger” (507). Sylvia Plath’s “Morning Song” exemplifies the indifference and estrangement that de Beauvoir describes. However, where de Beauvoir asserts that “a whole complex of economical and sentimental considerations makes the baby seem either a hindrance or a jewel” (510), Plath’s poem illustrates how a child can simultaneously be both hindrance and jewel. Ultimately, “Morning Song” shows us how new mothers can overcome the conflicting emotions de Beauvoir describes.

Daniel DiGiacomo. From Mourning Song to “Morning Song”: The Maturation of a Maternal Bond.

Notice that in this brief passage, the writer fairly represents de Beauvoir’s theory about maternal feelings, then goes on to apply a portion of that theory to Plath’s poem, a focusing move that establishes the writer’s special interest in an aspect of Plath’s text. In this case, the application yields new insight about the non-universality of de Beauvoir’s theory, which Plath’s poem troubles. The theory magnifies a portion of the primary text, and its application puts pressure on the soundness of the theory.

Applying a Theoretical Lens: W.E.B. Du Bois Applied to Langston Hughes

Experienced literary critics are familiar with a wide range of theoretical texts they can use to interpret a primary text. As a less experienced student, your instructors will likely suggest pairings of theoretical and primary texts. We would like you to consider the writerly workings of the theory-primary text application by examining a student’s paper entitled “Double-consciousness in ‘Theme for English B,” an essay which uses W.E.B. Du Bois’s theory (of double-consciousness ) to elucidate and interpret Langston Hughes’s poem (“Theme for English B”). W.E.B. Du Bois (1868-1963) was an American sociologist, civil rights activist, author, and editor. Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was an American poet, activist, editor, and guiding member of the group of artists now known as the Harlem Renaissance.

But before you can make sense of that student’s essay, we ask that you read both a synopsis of the theoretical text and the primary text .

Primary Text

The instructor said,

Go home and write a page tonight.

And let that page come out of you—

Then, it will be true.

I wonder if it’s that simple?

I am a twenty-two, colored, born in Winston-Salem.

I went to school there, then Durham, then here

to this college on the hill above Harlem,

I am the only colored student in my class.

The steps from the hill lead down into Harlem through a park, then I cross St. Nicholas,

Eighth Avenue, Seventh, and I come to the Y,

the Harlem Branch Y, where I take the elevator

up to my room, site down, and write this page:

It’s not easy to know what is true for you or me

at twenty-two, my age. But I guess I’m what

I feel and see and hear, Harlem, I hear you:

hear you, hear me—we two—you, me, talk on this page.

(I hear New York, too.) Me—who?

Well, I like to eat, sleep, drink, and be in love.

I like to work, read, learn, and understand life.

I like a pipe for a Christmas present,

or records—Bessie, bop, or Bach.

I guess being colored doesn’t make me not like

the same things other folks like who are other races.

So will my page be colored that I write?

Being me, it will not be white.

But it will be a part of you, instructor.

You are white—

yet a part of me, as I am a part of you.

That’s American.

Sometimes perhaps you don’t want to be a part of me.

Nor do I often want to be a part of you.

But we are, that’s true!

As I learn from you,

I guess you learn from me—

although you’re older—and white—

and somewhat more free.

Theoretical Text

W.E.B. Du Bois

Of Our Spiritual Strivings

O water, voice of my heart, crying in the sand,

All night long crying with a mournful cry,

As I lie and listen, and cannot understand

The voice of my heart in my side or the voice of the sea.

O water, crying for rest, is it I, is it I?

All night long the water is crying to me.

Unresting water, there shall never be rest

Till the last moon drop and the last tide fall,

And the fire of the end begin to burn in the west;

And the heart shall be weary and wonder and cry like the sea,

All life long crying without avail

As the water all nigh long is crying to me.

—Arthur Symons

Between me and the other world there is an unasked question: unasked by some through feelings of delicacy; by others through the difficulty of rightly framing it. All, nevertheless, flutter round it. They approach me in a half-hesitant sort of way, eye me curiously or compassionately, and then, instead of saying directly, How does it feel to be a problem? they say, I know an excellent colored man in my town; or I fought at Mechanicsville; or Do not these Southern outrages make your blood boil? At these I smile, or am interested, or reduce the boiling to a simmer, as the occasion may require. To the real question, How does it feel to be a problem? I answer seldom a word.

And yet, being a problem is a strange experience—peculiar even for one who has never been anything else, save perhaps in babyhood and in Europe. It is in the early days of rollicking boyhood that the revelation first bursts upon one, all in a day, as it were. I remember well when the shadow swept across me. I was a little thing, away up in the hills of New England, where the dark Housatonic winds between Hoosac and Taghkanic to the sea. In a wee wooden schoolhouse, something put it into the boys’ and girls’ heads to buy gorgeous visiting-cards—ten cents a package—and exchange. The exchange was merry, till one girl, a tall newcomer, refused my card—refused it peremptorily, with a glance. Then it dawned upon me with a certain sadness that I was different from the others; or, like, mayhap, in heart and life and longing, but shut out from their world as by a vast veil. I had thereafter no desire to tear down that veil, to creep through; I held all beyond it in common contempt, and lived above it in a region of blue sky and great wandering shadows. That sky was bluest when I could beat my mates at examination time, or beat them at a footrace, or even beat their stringy heads. Alas, with the hears all this fine contempt began to fade; for the worlds I long for, and all their dazzling opportunities, were theirs, not mine. But they should not keep these prizes, I said; some, all, I would wrest from them. Just how I would do it I could never decide: by reading law, by healing the sick, by telling the wonderful tales that swam in my head—some way. With other black boys the strife was not so fiercely sunny: their youth shrunk into tasteless sycophancy, or into silent hatred of the pale world about them and mocking distrust of everything white, or wasted itself in a bitter cry, Why did God make me an outcast and a stranger in mine own house? The shades of the prison-house closed round about us all: walls strait and stubborn to the whitest, but relentlessly narrow, tall, and unscalable to sons of night who must plod darkly on in resignation, or beat unavailing palms against the stone, or steadily, half hopelessly, watch the streak of blue above.

After the Egyptian and Indian, the Greek and Roman, the Teuton and Mongolian, the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world, a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his tw0-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strengths alone keeps it from being torn asunder.

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.

This, then, is the end of his striving: To be a coworker in the kingdom of culture, to escape both death and isolation, to husband and use his best powers and his latent genius. These powers of body and mind have in the past been strangely wasted, dispersed, or forgotten. The shadow of a might Negro past flits through the tale of Ethiopia the Shadowy and of Egypt the Sphinx. Throughout history, the powers of single black men flash here and there like falling stars, and die sometimes before the world has rightly gauged their brightness. Here in America, in the few days since Emancipation, the black man’s turning hither and thither in hesitant and doubtful striving has often made his very strength to loos effectiveness, to seem like absence of power, like weakness. And yet it is not weakness—it is the contradiction of double aims. The double-aimed struggle of the black artisan—on the one hand to escape white contempt for a nation of mere hewers of wood and drawers of water, and on the other hand to plough and nail and dig for a poverty-stricken horde—could only result in making him a poor craftsman, for he had but half a heart either cause. By the poverty and ignorance of his people, the Negro minister or doctor was tempted toward quackery and demagogy; and by the criticism of the other world, toward ideals that made him ashamed of his lowly tasks. The would-be black savant was confronted by the paradox that the knowledge his people needed was a twice-told tale to his white neighbors, while the knowledge which would teach the white world was Greek to his own flesh and blood. The innate love of harmony and beauty that set the ruder souls of his people a-dancing and a-singing raised but confusion and doubt in the soul of the black artist; for the beauty revealed to him was the soul-beauty of a race which his larger audience despised, and he could not articulate the message of another people. This waste of double aims, this seeking to satisfy two unreconciled ideals, has wrought sad havoc with the courage and faith and deeds of ten thousand thousand people—has sent them often wooing false gods and invoking false means of salvation, and at times has even seemed about to make them ashamed of themselves.

Away back in the days of bondage they thought to see in one divine event the end of all doubt and disappointment; few men ever worshipped Freedom with half such unquestioning faither as did the American Negro for two centuries. To him, so far as he thought and dreamed, slavery was indeed the sum of all villainies, the cause of all sorrow, the root of all prejudice; Emancipation was the key to a promised land of sweeter beauty than ever stretched before the eyes of wearied Israelites. In song and exhortation swelled one refrain—Liberty; in his tears and curses the God he implored had Freedom in his right hand. At last it came—suddenly, fearfully, like a dream. With one wild carnival of blood and passion came the message in his own plaintive cadences:—

“Shout, O children!

Shout, you’re free!

For God has bought your liberty!”

Years have passed away since then—ten, twenty, forty; forty years of national life, forty years of renewal and development, and yet the swarthy scepter sits in its accustomed seat at the Nation’s feast. In vain do we cry to this our vastest social problem:—

“Take any shape but that, and my firm nerves

Shall never tremble!”

The Nation has not yet found peace from its since; the freedman has not yet found in freedom his promised land. Whatever of good may have come in these years of change, the shadow of a deep disappointment rests upon the Negro people—a disappointment all the more bitter because the unattained ideal was unbounded save by the simple ignorance of a lowly people.

The first decade was merely a prolongation of the vain search for freedom, the boon that seemed ever barely to elude their grasp—like a tantalizing will-o-the-wisp, maddening and misleading the headless host. The holocaust of war, the terrors of the Ku Klux Klan, the lies of carpetbaggers, the disorganization of industry, and the contradictory advice of friends and foes, left the bewildered serf with no new watchword beyond the old cry for freedom. As the time flew, however, he began to grasp a new idea. The ideal of liberty demanded for its attainment powerful means, and these the Fifteenth Amendment gave him. The ballot, which before he had looked upon as a visible sign of freedom, he now regarded as the chief means of gaining and perfecting the liberty with which war had partially endowed him. And why not? Had not votes made war and emancipated millions? Had not votes enfranchised the freedmen? Was anything impossible to a power that had done all this? A million black men started with renewed zeal to vote themselves into the kingdom. So the decade flew away, the revolution of 1876 came, and left the half-free serf weary, wondering, but still inspired. Slowly but steadily, in the following years, a new vision began gradually to replace the dream of political power—a powerful movement, the rise of another ideal to guide the unguided, another pillar of fire by night after a clouded day. It was the ideal of “book-learning”: the curiosity, born of compulsory ignorance, to know and test the power of the cabalistic letters of the white man, the longing to know. Here at last seemed to have been discovered the mountain path to Canaan; longer than the highway to Emancipation and law, steep and rugged, but straight, leading to heights high enough to overlook life.

Up the new path the advance guard toiled, slowly, heavily, doggedly; only those who have watched and guided the faltering feet, the misty minds, the dull understandings, of the dark pupils of these schools know how faithfully, how piteously, this people strove to learn. It was weary work. The cold statistician wrote down the inches of progress here and there, noted also where here and there a foot had slipped or someone fallen. To the tired climbers, the horizon was ever dark, the mists were often cold, the Canaan was always dim and far away. If, however, the vistas disclosed as yet no goal, no resting place, little but flattery and criticism, the journey at least gave leisure for reflection and self-examination; it changed the child of Emancipation to the youth with dawning self-consciousness, self-realization, self-respect. In those somber forests of his striving his own soul rose before him, and he saw himself—darkly as through a veil; and yet he saw in himself some faint revelation of his power, of his mission. He began to have a dim feeling that, to attain his place in the world, he must be himself, and not another. For the first time he sought to analyze the burden he bore upon his back, that deadweight of social degradation partially masked behind a half-named Negro problem. He felt his poverty; without a cent, without a home, without land, tools, or savings, he had entered into competition with rich, landed, skilled neighbors. To be a poor man is hard, but to be a poor race in a land of dollars is the very bottom of hardships. He felt the weight of his ignorance,—not simply of letters, but of life, of business, of the humanities; the accumulated sloth and shirking and awkwardness of decades and centuries shackled his hands and feet. Nor was his burden all poverty and ignorance. The red stain of bastardy, which two centuries of systematic legal defilement of Negro women had stamped upon his race, meant not only the loss of ancient African chastity, but also the hereditary weight of a mass of corruption from white adulterers, threatening almost the obliteration of the Negro home.

A people thus handicapped ought not to be asked to race with the world, but rather allowed to give all its time and thought to its own social problems. But alas! while sociologists gleefully count his bastards and prostitutes, the very soul of the toiling, sweating black man is darkened by the shadow of a vast despair. Men call the shadow prejudice, and learnedly explain it as the natural defense of culture against barbarism, learning against ignorance, purity against crime, the “higher” against the lower races. To which the Negro cries Amen! and swears that to such much of this strange prejudice as is founded on just homage to civilization, culture, righteousness, and progress, he humbly bows and meekly does obeisance. But before that nameless prejudice that leaps beyond all this he stands helpless, dismayed, and well-nigh speechless; before that personal disrespect and mockery, the ridicule and systematic humiliation, the distortion of fact and wanton license of fancy, the cynical ignoring of the better and the boisterous welcoming of the worse, the all-pervading desire to inculcate disdain for everything b lack, from Toussaint to the devil—before this there rises a sickening despair that would disarm and discourage any nation save the black host to whom “discouragement” is an unwritten word.

But the facing of so vast a prejudice could not but bring the inevitable self-questioning, self-disparagement, and lowering of ideals which ever accompany repression and breed in an atmosphere of contempt and hate. Whisperings and portents came borne upon the four winds: Lo! we are diseased and dying, cried the dark hosts; we cannot write, our voting is vain; what we need of education, since we must always cook and serve? And the Nation echoed and enforced this self-criticism, saying: Be content to be servants, and nothing more; what need of higher culture for half-men? Away with the black man’s ballot, by force or fraud—and behold the suicide or a race! Nevertheless, out of the evil came something of good—the more careful adjustment of education to real life, the clearer perception of the Negroes’ social responsibilities, and the sobering realization of the meaning of progress.