Critical Thinking Crucial to Entrepreneurship

Apr 18, 2022

The students we serve, sometimes called Generation Next, are typically between 18 and 25 years of age and have grown up with personal computers, cell phones, the internet, text messaging and social media. They are taking their place in a world where the only constant is rapid change.

Our entrepreneurship programs are focused on developing knowledge and critical thinking skills in an action-based, learn-by-doing setting. We see a new age of diversity coming — more diversity of backgrounds, more women and more younger people.

Characteristics we see in successful entrepreneurs which shape our thinking on programs and initiatives are:

- A sense of curiosity that allows them to continually challenge the status quo, explore different options and innovate

- A willingness to refine and validate their idea to determine whether it has potential

- The ability to adapt and keep moving forward when unexpected events occur

- The decisiveness to make challenging decisions and see them through

- The ability to build a team with complementary talents focused on a common goal

- A high risk tolerance and the ability to balance risk and reward

- Persistence, grit and the ability to deal with and learn from failure

- Critical thinking skills and a long-term focus which allows them to start, grow and sustain a business

In 1899, Charles Dewell, head of the U.S. Patent Office, recommended to President McKinley that the office should be closed because “Everything that can be invented has been invented.” History has proven and will continue to prove that vision to be woefully incorrect. Our take on the future has innovation and an increasingly diverse population of entrepreneurs playing a significant role in providing products and services across a broad range of solutions in health care, data analytics, artificial intelligence, additive manufacturing, digital commerce, ease of use, social media, social and environmental responsibility, location-independent solutions serviced by more remote workers, as well as online learning, just to name a few.

Our job is to help develop the critical thinking skills to enable Auburn students to lead and excel in these fields and many others.

Lou Bifano Director New Venture Accelerator

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 11 min read

Entrepreneurial Skills

The skills you need to start a great business.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

Are you thinking about setting up your own business? If the answer is yes, you're not alone. The pandemic may have laid waste to great swathes of industry, but it's fueled an extraordinary surge in startups and new small businesses, as those laid off from affected firms explore new opportunities.

Reports from the U.S., Japan and across Europe show record-breaking levels of business registrations. [1] For example, figures from the U.S. Census Bureau show that new business registrations in July 2020 were 95 percent higher than during the same period in 2019. [2]

But what does it take to be a successful entrepreneur? Whether you've seen an exciting gap in the market, or feel forced to reassess your career following job loss, this article explores the skills you need to make it as an entrepreneur. It also signposts resources that you can use to develop the skills required for success.

What Are Entrepreneurial Skills?

Entrepreneurial skills are those normally associated with being an entrepreneur, although anyone can develop them.

Being an entrepreneur usually means starting and building your own successful business, but people with entrepreneurial skills can thrive within larger organizations, too.

Many researchers have studied entrepreneurial skills, but found no definitive answers. Some common themes are:

- Personal characteristics.

- Interpersonal skills.

- Critical and creative-thinking skills.

- Practical skills and knowledge.

Regardless of how you define it, entrepreneurship isn't easy. So be prepared to do the "hard yards," even after you've learned the skills we describe below.

The following sections examine each skill area in more detail, and look at some of the questions you'll need to ask yourself if you want to become a successful entrepreneur.

The Personal Characteristics of an Entrepreneur

Do you have the mindset to be a successful entrepreneur? For example, entrepreneurs tend to be strongly innovative in outlook, and they may take risks that others would avoid.

Examine your own personal characteristics, values and beliefs, and ask yourself these questions:

- Optimism: Are you an optimistic thinker? Optimism is an asset, and it will help you through the tough times that many entrepreneurs experience as they find a business model that works for them.

- Initiative: Do you have initiative, and instinctively start problem-solving or business-improvement projects?

- Drive and persistence: Are you self-motivated and energetic? And are you prepared to work hard, for a very long time, to realize your goals?

- Risk tolerance: Are you able to take risks, and make decisions when facts are uncertain?

- Resilience: Are you resilient, so that you can pick yourself up when things don't go as planned? And do you learn and grow from your mistakes and failures? (If you avoid taking action because you're afraid of failing, our article, Overcoming Fear of Failure , can help you to face your fears and move forward.)

Entrepreneurial Interpersonal Skills

As an entrepreneur, you'll likely have to work closely with others – so it's essential that you're able to build good relationships with your team, customers, suppliers, shareholders, investors, and other stakeholders.

Some people are more gifted in this area than others, but you can learn and improve these skills.

Evaluate your people skills by taking our How Good Are Your People Skills? self-test.

The types of interpersonal skills you'll need include:

- Leadership and motivation: Can you lead and motivate others to follow you and deliver your vision? And are you able to delegate work to other people? As an entrepreneur, you'll have to depend on others to get beyond the early stages of your business – there's just too much to do by yourself!

- Communication skills: Are you skilled in all types of communication? You need to be able to communicate well to sell your vision of the future to a wide variety of audiences, including investors, potential clients and team members.

- Listening: Do you hear what others are telling you? Your ability to listen and absorb information and opinions can make or break you as an entrepreneur. Make sure that you're skilled at active and empathic listening .

- Personal relationships: Do you have good "people skills"? Are you self-aware, good at regulating your emotions, and able to respond positively to feedback or criticism? Our article, Emotional Intelligence , offers a range of strategies for developing these crucial attributes.

- Negotiation: Are you a strong negotiator? Not only do you need to negotiate favorable prices, but you'll also need to resolve differences between people in a positive, mutually beneficial way.

- Ethics: Do you deal with people based on respect, integrity, fairness, and trust? Can you lead ethically? You'll find it difficult to build a happy, productive business if you deal with staff, customers or suppliers in a shabby way.

Many startups are single-owner ventures, or small numbers of friends or family members looking to make it together. For information on how to work or manage in these micro- or family enterprises, see these useful Mind Tools resources:

- How to Manage People in a Micro Business

- Working in a Family Business

- Managing in a Family Business

- Working for a Small Business

Critical and Creative-Thinking Skills for Entrepreneurs

As an entrepreneur, you need to come up with fresh ideas, and make good decisions about opportunities and potential projects.

Many people think that you're either born creative or you're not. But creativity is a skill that you can develop, and there are many tools available to inspire you.

- Creative thinking: Are you able to see situations from a variety of perspectives to generate original ideas? Tools like the Reframing Matrix can help you to do this.

- Problem solving: You'll need sound strategies for solving business problems that will inevitably arise. Tools such as Cause & Effect Analysis , the 5 Whys technique, and CATWOE are a good place to start.

- Recognizing opportunities: Do you recognize opportunities when they present themselves? Can you spot a trend? And are you able to create a workable plan to take advantage of the opportunities you identify?

Practical Entrepreneurial Skills and Knowledge

Entrepreneurs also need solid practical skills and knowledge to produce goods or services effectively, and to run a company.

- Goal setting: Setting SMART goals (Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-Bound) will focus your efforts and allow you to use your time and resources more effectively.

- Planning and organizing: Do you have the talents, skills and abilities necessary to achieve your goals? Can you coordinate people to achieve these efficiently and effectively? Strong project-management skills are important, as are basic organization skills. And you'll need a coherent, well thought-out business plan , and the appropriate financial forecasts .

- Decision making: Your business decisions should be based on good information, evidence, and weighing up the potential consequences. Core decision-making tools include Decision Tree Analysis, Grid Analysis, and Six Thinking Hats .

Take our self-test, How Good Is Your Decision Making? , to learn more.

You need knowledge in many different areas when you're starting or running a business, so be prepared for some serious learning!

Be sure to include:

- Business knowledge: Ensure that you have a working knowledge of the main functional areas of a business: sales, marketing, finance, and operations. If you can't fulfilll all these functions yourself, you'll need to hire others to work with you, and manage them competently.

- Entrepreneurial knowledge: How will you fund your business, and how much capital do you need to raise? Finding a business model that works for you can require a long period of experimentation and hard work.

- Opportunity-Specific Knowledge: Do you understand the market you're attempting to enter, and do you know what you need to do to bring your product or service to market?

- Venture-Specific Knowledge: Do you know what it takes to make this type of business successful? And do you understand the specifics of the business that you want to start?

You can also learn from others who've worked on projects similar to the ones that you're contemplating, or find a mentor – someone else who's been there before and is willing to coach you.

As an entrepreneur, you must also learn the rules and regulations that apply in the territory or territories that you're operating in. These websites may be useful:

- Australia – Business.gov.au

- Canada – Canada Business Network

- India – startupindia

- United Kingdom – GOV.UK

- United States – U.S. Small Business Administration

Working in a business like the one you want to launch is a great way to learn the ropes. But be aware of non-compete clauses in your employment contract. In some jurisdictions, these clauses can be very restrictive. You don't want to risk your future projects by violating the rights of another entrepreneur or organization.

Is Entrepreneurship Right for You?

Before you proceed with your plan to become an entrepreneur, assess your skills against all of the questions and considerations above. Use a Personal SWOT Analysis to examine your Strengths and Weaknesses, your Opportunities, and the Threats that you may face.

Be honest with yourself about your motivations and the level of commitment you're prepared to give to your project. This could prevent you from making a costly mistake.

As you work through your analysis, you may feel that you're ready to plunge into your exciting new venture. Alternatively, you may decide to wait and further develop your skills. You may even decide that entrepreneurship isn't for you after all.

Becoming an entrepreneur is an important career decision, so avoid the temptation to act impulsively. Do your homework. Reflect on your needs, your objectives, and your financial and personal circumstances. Entrepreneurialism can take a huge amount of time and dedication, so make sure that it feels right.

While there's no single set of traits or skills for being a successful entrepreneur, there are many that you can learn to help you succeed.

These can be divided into four broad categories:

Examine your own strengths and weaknesses in these areas and assess the time and commitment you'll need to get "up to speed."

Take time to decide whether this is the right path for you.

[1] Forbes (2021). Pandemic Fuels Global Growth Of Entrepreneurship And Startup Frenzy [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 23, 2022.]

[2] U.S. Census Bureau. Business Formation Statistics [online]. Available here . [Accessed May 23, 2022.]

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Book Insights

Winning Minds: Secrets from the Language of Leadership

By Simon Lancaster

Goffee and Jones' DREAMS

Retain People by Being Authentic

Add comment

Comments (0)

Be the first to comment!

Get 30% off your first year of Mind Tools

Great teams begin with empowered leaders. Our tools and resources offer the support to let you flourish into leadership. Join today!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Tips for Dealing with Customers Effectively

Pain Points Podcast - Procrastination

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Pain points podcast - starting a new job.

How to Hit the Ground Running!

Ten Dos and Don'ts of Career Conversations

How to talk to team members about their career aspirations.

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Strategic choice at business level.

Exploring How Different Strategies Can Help Organizations Succeed In Their Industry

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Critical Thinking Skills for Entrepreneurs

The average person is barely equipped with foundational knowledge on how to start a business, which is why the most successful entrepreneurs will tell you that it takes more than just ideas or even intelligence to turn that idea into an operating company. It's all about critical thinking.

Here, we'll look at the fundamental critical thinking skills every entrepreneur needs to succeed. These perceptions- and understanding-changing skills can be acquired through a thorough education or life experience, so there's no reason not to learn them.

Learn understanding not concepts:

This is the most important foundational skill of critical thinking. It allows you to process complex information and arrive at sound decisions. Understanding comes from analyzing data, discovering new perspectives, and finding hidden meanings in a meaningful way.

Practical experience teaches you to ask hard questions, think outside the box, and connect complex dots. There is no faster way to develop understanding than learning from mistakes and challenging your beliefs through debate.

Experiment, take risks, and challenge your own beliefs:

This is the testing phase of critical thinking, where you put your understanding to the test. That means you create two different conclusions and let the audience decide which one sounds more convincing. You can challenge your beliefs in real time if you know how to phrase your arguments correctly.

It's important to deal with ambiguity and uncertainty as well. You should be prepared for when things don't work out as you'd expect. A good example is emotional intelligence, where you get to choose between different options, like choosing between anger and relief.

Know what you don't know:

When you were just an observer, you could choose between two sides. When you become an observer and create a new perspective, you are no longer the judge; you are the subject. The consequence is that you need to acknowledge that you don't know things.

Recognizing your ignorance will help you understand the unknown parts of any problem. It also helps you in your decision-making because you'll be able to consider new options and understand risks a lot better than if you felt invincible.

Do you feel like you are struggling with putting "strategy" and "business growth concepts" in place that make a difference? Doing it all is overwhelming! Let’s have a honest discussion about your business and see if the Power of 10 can help you. Click “HERE” to have a great conversation with our team today.

Written By The Strategic Advisor Board - Chris O'Byrne C. 2017-2021 Strategic Advisor Board / M&C All Rights Reserved www.strategicadvisorboard.com / [email protected]

5 Questions Every Founder Must Ask

The Secrets Of Viral Marketing

How To Succeed Amid A Personal Crisis

Body Language That Helps You Connect

5 Ways To Become A Better Boss

The Best Industries For Starting A Business

The 3 Steps To Side Hustling

Stretching Your Money During Inflation

How to Surpass Your Largest Competitors

What To Consider When Returning To The Office Post Pandemic

SAB Foresight

Receive updates and insights

SAB Foresight Signup Form

Thank you for subscribing.

You will receive the next newsletter as soon as it is available.

Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

GPDR

Copyright © 2017-2023 Strategic Advisor Board, LLC / M&C

- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Urban Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Language Acquisition

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Culture

- Music and Religion

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Lifestyle, Home, and Garden

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Society

- Law and Politics

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Medical Ethics

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Games

- Computer Security

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business History

- Business Strategy

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Systems

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Theory

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Politics and Law

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Developmental and Physical Disabilities Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

4 Entrepreneurial Creativity: The Role of Learning Processes and Work Environment Supports

Michele Rigolizzo is a Doctoral Student at Harvard Business School.

Teresa Amabile is the Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration in the Entrepreneurial Management Unit at Harvard Business School.

- Published: 09 July 2015

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

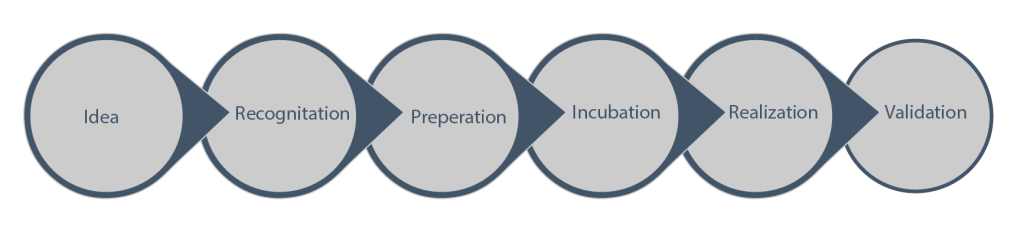

This chapter argues that the creative process is supported, at each stage, by certain learning behaviors and that both creative behaviors and learning behaviors depend on particular social-environmental conditions at each stage. Focusing on entrepreneurial creativity within startups and established organizations, the chapter describes four stages: problem identification; preparation; idea generation; idea evaluation and implementation. It explains how creativity-relevant and domain-relevant skills are distinct and how each skill set becomes more or less important depending on the uncertainty inherent in a given stage. The chapter also discusses the role of intrinsic motivation and the impact of various forces on the motivation for entrepreneurial creativity. With examples drawn from cases of entrepreneurial individuals and companies, links are made between creativity, learning, and the ways in which social-environmental factors influence the motivation for these behaviors differentially at different points in the creative process.

Introduction

Individuals are constantly seeking creative outlets. Hobbies—the activities we choose to engage in for fun—are often very creative activities. Even at work, organizations advertise innovation as a way to attract top talent. Why, then, is it important or even necessary to motivate creativity? Creativity—the generation of new, useful ideas—may be inherently rewarding, but it is also easily stifled and highly sensitive to social-environmental conditions ( Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996 ). In this chapter, we argue that creativity is a staged process supported by learning behaviors. Both creative behaviors and learning behaviors differ somewhat across the stages of the creative process, and the optimal social environments for motivating them are stage dependent ( Amabile, 1997 ; Nembhard & Edmondson, 2006 ).

As humans learn new skills, we assess our environment, process new information, develop solutions, and evaluate their use. Creative performance involves a similar process that is directed toward the production and evaluation of novel and useful ideas rather than skills. Entrepreneurial undertakings require rapid learning in service of nimble creativity in order to succeed in dynamic and complex business environments. In essence, entrepreneurial creativity is the development of novel and useful products, services, or business models in the establishment of a new venture ( Amabile, 1997 ). The entrepreneurial creative process and its associated learning behaviors do not differ from those involved in other forms of creativity (for example, in science or the arts). However, in entrepreneurial ventures, implementation of the end product serves as a touchstone for each stage of the creative process, providing guidance and correction as ideas are developed, tested, rejected, and finally come to fruition. Learning is heavily involved throughout. Therefore, by understanding the process of creativity through the lens of learning, entrepreneurs (and entrepreneurial managers in more established organizations) can make purposeful decisions about how to motivate employees and, most importantly, how to avoid extinguishing the creative spark.

Creativity depends on three internal components within the individual, and one external component, the social environment ( Amabile, 1983 , 1993 , 1996 ). The internal components are domain-relevant skills, creativity-relevant processes, and task motivation. Although each component depends, to some extent, on innate or deeply ingrained talents and orientations, they can all be influenced by experience and by the immediate social environment. Each component is necessary, and none is sufficient for creative behavior; the higher the level of each component, the more creative the outcome.

Domain-relevant skills include talent in, knowledge about, and technical expertise for doing work in the domain or domains that are relevant to the problem or task at hand. Essentially, this component is the individual’s set of cognitive pathways for solving a given problem or doing a given task. The larger the set, the more alternatives the individual has for producing a new combination. The ability to merge ideas or products into new designs is especially important for entrepreneurs. Many of the most successful new entrepreneurial ventures involve the combination of already existing products or technologies. For example, the explosion of popular apps for smartphones demonstrates the opportunity of combining an existing product (e.g., game, calendar, paperback book) with a new technology.

Creativity-relevant processes include personality processes (e.g., tolerance for ambiguity) and cognitive styles (e.g., a propensity for idea proliferation) that predispose the individual toward unusual approaches to problems, as well as work styles marked by high energy and perseverance on difficult problems. Because so many new ideas fail for reasons both within and outside the entrepreneur’s control, both an abundance of ideas and the determination to persevere are critical skills to entrepreneurial creativity.

Task motivation can be either intrinsic or extrinsic (or, more, likely, some combination of the two). Intrinsic motivation is the drive to engage in a task because it is interesting, enjoyable, personally challenging, or satisfying in some way; this form of motivation is most conducive to creativity. Extrinsic motivation is the drive to engage in a task for some reason outside the task itself—for example, to gain a reward, win a competition, or earn a positive evaluation. Extrinsic motivation can undermine intrinsic motivation (e.g., Deci, Koestner, & Ryan, 1999 ), and thus creativity, if it is perceived by the individual as controlling or constraining. However, “synergistic extrinsic motivation,” which is the use of externally derived incentives to enhance existing intrinsic motivation, can be a powerful tool ( Amabile, 1993 ). For example, informational feedback that provides direction on how to make progress or improve performance can support intrinsic engagement in the task.

The fourth component, the external social environment (e.g., the work environment in an organization) influences each of the three internal components ( Amabile, 1983 , 1993 , 1996 ). Domain-relevant skills can be influenced by supports for learning, including formal training and on-the-job opportunities for gaining new skills. Creativity-relevant processes can be influenced by training in idea-generation techniques and the development of thinking skills through observation of and collaboration with creative colleagues ( Scott, Leritz, & Mumford, 2004 ). Studies of learning curves ( Epple, Argote, & Devadas, 1991 ) show that the more we use skills, the more skilled we become. An environment that supports the process of creativity, rather than the outcome, allows people to practice and learn both from and for the creative process.

Recent research suggests that creativity-relevant processes can also be influenced by events in the work environment that cause positive or negative affect ( Amabile, Barsade, Mueller, & Staw, 2005 ; Amabile & Mueller, 2008 ). Of all three components, however, task motivation is the most strongly and immediately influenced by the work environment. When the environment supports autonomy and exploration of challenging, meaningful work, intrinsic motivation increases. When the environment is constraining and the work is perceived as meaningless, intrinsic motivation decreases ( Ryan & Deci, 2000 ).

The four creativity components all contribute to the outcome of any creative process an individual undertakes—whether that process is as minor as tweaking a company’s logo or as major as starting a new venture. The creative process encompasses stages which, although distinct, do not necessarily follow a straightforward sequence ( Amabile, 1996 ). However, for simplicity’s sake, the stylized sequence can be described as follows: (1) problem or opportunity identification; (2) preparation; (3) idea generation; and (4) idea evaluation and implementation ( Amabile, 1983 ).

The initial stage of the creative process, problem identification, is accomplished by the difficult task of challenging assumptions ( Amabile, 1996 ; Piaget, 1966 ). It is facilitated by cultivating the intrinsic motivation to take risks and explore the world—two behaviors that are particularly important for entrepreneurship. In Stage Two, preparation, knowledge, and resources are gathered from multiple sources; the purpose of this stage is to acquire relevant information before generating solutions to the problem ( Amabile, 1996 ). Reinventing the wheel is not a useful exercise for entrepreneurs. In Stage Three, idea generation, the newly gathered information is combined with existing knowledge to generate new connections and create new solutions. However, not all of these new ideas will be valuable or acceptable. The fourth stage of the creative process is idea evaluation and implementation—the evaluation of ideas in terms of the optimal level of novelty and appropriateness to meet the initial goal ( Amabile, 1996 ). In the arts, the appropriateness criterion is met when the work of art is expressive of intended meaning. In business, however, appropriateness equates to usefulness for customers. For entrepreneurs, it is especially important that the ideas be truly useful.

The three components of creativity—domain- relevant skills, creativity-relevant processes, and task motivation—have differential importance at the different stages of the creative process, depending on the level of new learning or novel cognitive processing required in the activity at that stage.

Domain-relevant skills play a prominent role at the second and fourth stages, where knowledge is acquired (Stage Two) or applied (Stage Four) in a relatively straightforward way. For example, for individuals in entrepreneurial ventures, knowledge about the domain and technical skills provide a way to assess the current business environment and evaluate the feasibility of newly generated ideas. Creativity-relevant processes are more prominent in the third stage. Developing novel ideas requires complex cognitive processing and breaking mental sets to view existing problems in new ways.

Of course, both domain skills and creativity skills are needed at all stages of the creative process, but they become more or less important depending on the level of uncertainty inherent in the stage. For example, knowledge of the domain space could reduce the time and effort exerted in the Stage One (problem identification). An entrepreneur who is familiar with the needs of customers and potential customers should be able to more easily identify unmet needs or avoid trying something that has already been shown not to work.

Finally, intrinsic motivation is most important in the first and third stages, when a drive to engage in unfettered exploration is most valuable. The componential theory of creativity emphasizes the importance of stage-appropriate motivation ( Amabile, 1997 ): intrinsic motivation is more crucial at Stages One and Three, when the most novel thinking is required, but synergistic extrinsic motivation can be useful at the more algorithmic stages (Stages Two and Four).

In the remainder of this chapter, we integrate research on creativity, learning, and entrepreneurship to delve more deeply into each stage of the creative process. Using examples from successful and struggling entrepreneurial ventures, we explore the creative behaviors that are most needed at each stage, the learning behaviors that support creativity at each stage, and the environmental factors that are most conducive to the necessary motivational states. Throughout, we discuss implications for leading entrepreneurial ventures.

Stage One: Problem Identification

The first stage of the creative process is problem identification, which is directed toward making sense of the problem or opportunity at hand ( Amabile, 1997 ). The goal of this stage is to construct the problem in a way that increases the chances of generating novel, workable solutions. In entrepreneurial settings, opportunities may seem obvious after the fact—although no one had seized them previously. For example, Nike founder Phil Knight, an avid middle-distance runner in school, had a coach who was obsessed with finding great shoes for his team ( Wasserman & Anderson, 2010 ). Knight knew that he wanted to provide runners like himself with shoes that were comparable in quality to Adidas but much less expensive. Knight’s domain-relevant knowledge made the opportunity in the market clear to him. His innovation lay in figuring out how to make that idea a reality.

Alternatively, an entrepreneur may spend intensive time and effort figuring out the problem that needs solving. Creativity-relevant processes, such as challenging assumptions and making novel connections, can help entrepreneurs discover new problems. Southwest Airlines challenged the assumption that consumers make air travel decisions based on service and amenities. Solving the problem—by lowering cost at the expense of amenities—was then a matter of execution.

Problems can also be “discovered” by reframing an existing situation. Reframing has the power to transform difficult problems into exciting opportunities ( Dutton, 1992 ). Jeff Housenburg, CEO of Shutterfly, attributes his success to reframing Shutterfly’s service model. The company transformed from a photo finishing service to a vehicle for publishing personal photo albums. The reframing lay in viewing the company as one that sells memories, not products. This new way of envisioning the use of an existing product enabled Shutterfly to develop creative solutions for a much wider, nonprofessional market base. In Stage One of the creative process, reframing presents an old or familiar problem as a newly discovered one.

Desired Behaviors for Problem/Opportunity Identification

Whether the entrepreneur is discovering a new problem or reframing an existing one, certain behaviors help him or her to be effective during this stage of the creative process. These behaviors include thinking broadly; considering the passions, pain points, and nagging problems of oneself and others; scanning the environment widely ( Perkins, 2001 ); staying alert to things that don’t fit and needs that aren’t met; amplifying weak information signals that others may miss ( Ansoff, 1975 ); and abandoning safe, taken-for-granted assumptions ( Argyris, 1976 ).

As an example, consider the entrepreneurial venture Sittercity, an online babysitter–parent matching service ( Wasserman & Gordon, 2009 ). Sittercity was founded in Boston in 2001 by Genevieve Thiers, then a college student. By 2009, Sittercity had moved to Chicago, and its large, successful program in cities throughout the United States led to equity financing of $7.5 million. Throughout the growth of this company, Thiers engaged in many iterations through the creative process—each time, identifying a problem or opportunity, preparing to solve it, generating ideas, validating her chosen ideas by actually implementing them, and assessing results.

Thiers had a long history of babysitting—first for her six younger siblings, then for neighborhood children, and eventually for families who hired her during her college years. Moreover, she loved it; she had a passion for meeting new people, getting out of her own home, and eating food from someone else’s kitchen. Her initial problem identification grew from paying attention to her own unmet needs and nagging problems. About to graduate from college, she said, “I didn’t know what I was going to do with my life, but I wanted to do something big—not be a nine-to-five employee” ( Wasserman & Gordon, 2009 , p. 2). Thus, the initial problem was to create an unusual (entrepreneurial) career path for herself. This realization heightened Thiers’ alertness to unconventional opportunities, led her to think broadly about her future, and amounted to abandoning the safe, taken-for-granted assumption that she would stay in a “regular” job—even as she accepted a full-time job at IBM after college.

Three days before college graduation in 2000, Thiers identified the specific opportunity that would lead to the founding of Sittercity. She did so by picking up on a weak signal that most other people would have completely missed. She was posting flyers for an upcoming musical event, and she found herself helping a very pregnant woman post flyers advertising for a mother’s helper. In that moment, she saw the unmet need that countless parents have of finding a suitable babysitter, and she wondered if it would be possible to list all of the babysitters in the country in one place. To her, this could be the “big” undertaking she had been looking for. She worked on her business idea for many months, while also working full-time at IBM, and launched the Sittercity website in September 2001.

By March 2002, the number of parents and sitters registered on the site had begun to grow, and Thiers—still alert to weak signals and things that didn’t fit—noticed that a few parents were not from Boston; they were from New York or Cleveland. Puzzled, she inquired, and discovered that they were commuters to Boston from those cities who had heard about Sittercity from their work colleagues and were hoping to find sitters in their hometowns. This identified another opportunity: expand Sittercity to new locations.

Learning Behaviors that Support Stage One

The goal of the first stage of creativity is to spot new problems and opportunities. This requires a difficult shift in the deeply rooted underlying assumptions that drive the routine behaviors that make up most of our day. Learning these routines is often effortless; changing them is not. The difficulty arises, in part, because routines are extremely valuable. In their classic work on organizations, March and Simon (1958) provided a description of the power of routines for accomplishing the well-defined tasks that build organizational capacity. Routines increase efficiency by reducing uncertainty, variability, and the time it takes to make decisions. Once established, routinized behaviors, which March and Simon termed “programs,” are launched by a particular stimulus that can occur in many different situations. It is the routine, not the situation, that guides behavior ( Levitt & March, 1988 ). The nuances of the situation are suppressed in favor of the expectations of the routine ( Nelson & Winter, 1982 ). Routines, whether examined at the organizational or the individual level, are sticky—so sticky that adult learning theorists have long argued that breaking routine thinking requires a triggering event ( Dewey, 1938 ; Marsick & Watkins, 2001 ; Piaget, 1966 ).

This is particularly problematic for creative entrepreneurs because they must not only break their own routines but also convince investors and customers to try something new. Certain learning behaviors can help to activate routine-breaking triggers. Adopting an open systems view ( Senge, 1990 ), seeking feedback ( Edmondson, 1999a ), and maintaining a learning mindset ( Dweck, 2006 ) can all serve the creative behaviors of Stage One. An open systems view considers how all elements of a system interact, as well as the interactions among related systems. Seeking feedback means, among other things, looking for disconfirming information at the risk of proving favored ideas false. Similarly, a learning mindset is open to new possibilities and able to challenge existing assumptions. For our purposes, the key element is that individuals with a learning mindset are better able to extract learning from situations; they have “learned how to learn” in just about any setting ( Feuerstein & Rand, 1974 ).

Developing an open systems view of a given domain supports the creative behavior of thinking broadly. In his seminal work on organizational learning, Senge (1990) reveals how prone even top executives are to viewing only their piece in a system of interacting dependencies. By seeking to understand how a given product or service relies on, and is relied upon, by consumers, suppliers, competitors, and industries, entrepreneurs may be able to identify the gaps that trigger great ideas and the problems that are not being addressed by the current business environment.

Confirming or disconfirming hunches can be facilitated by expanding the scope of feedback beyond one’s own internal states and seeking help from others both within and outside the relevant domain. The active seeking of feedback is a necessary part of the learning process ( Edmondson, 1999a ) and can save valuable time by allowing the problem-solver to abandon infeasible ideas early ( McGrath, 2001 ) or by triggering new connections that identify unmet needs. Internal feedback can alert us to the weak signals missed by others and give us a sense of what doesn’t fit, while openness to external feedback helps us expand our thinking and develop a learning mindset.

A learning mindset is needed to engage in the creative behavior of scanning the environment widely. It raises one’s perspective above the routines themselves to adjust embedded associations and reframe the situation ( Kegan, 1982 ). This embracing of uncertainty, at the expense of the comfort of certainty, is a hallmark of human learning ( Piaget, 1966 ). As demonstrated in the example of Southwest Airlines, entrepreneurial opportunities often arise because current products and services rest on specific assumptions about the customers that belie their actual needs and desires. Getting into the practice of surfacing, and challenging, underlying beliefs is a learning tool that enables entrepreneurs to define the ultimate goal of their creative process.

Work Environment Influences at Stage One

All work behavior is motivated either intrinsically or extrinsically, and usually both ways ( Amabile, 1997 ). As we have noted, work motivation is strongly affected by the social environment. The social-environmental conditions that entrepreneurs seek for themselves and establish for their first employees can determine whether, and how, people in the entrepreneurial organization will be motivated to engage in the learning behaviors necessary at each stage of the creative process.

Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation are often considered opposite constructs, with extrinsic motivation undermining intrinsic. Indeed, decades of research in psychology, organizational behavior, and economics suggest that intrinsic motivation and complex performance (like creativity) diminish when people are focused primarily on extrinsic goals, such as tangible rewards and deadlines, or extrinsic constraints, such as restrictions on how a task may be done ( Deci & Ryan, 1980 ; Frey & Palacios-Huerta, 1997 ; Lepper & Greene, 1978 ; see Deci et al., 1999 , for a review).

However, an accumulating body of research supports a much more nuanced view ( Amabile, 1993 , 1996 ; Amabile & Kramer, 2011 ). It is true that extrinsic forces that lead individuals to feel controlled generate nonsynergistic extrinsic motivation, which does undermine the intrinsic desire to tackle a problem for its own sake. But extrinsic forces that support individuals’ ability to engage in problem solving or opportunity identification, such as rewards that provide resources or recognition that confirms competence, can create the synergistic extrinsic motivation that actually adds to intrinsic motivation. Whether this type of extrinsic motivation will support creativity depends on the stage of the creative process; this is the concept of stage-appropriate motivation mentioned earlier.

According to the componential theory of creativity ( Amabile, 1983 , 1996 ; Amabile & Mueller, 2008 ), a more purely intrinsically motivated state is conducive to Stage One, when problems to be solved and entrepreneurial opportunities to be pursued are being identified. Intrinsic motivation fosters the expansive thinking, wide exploration, breaking out of routines, and questioning of assumptions that this stage requires.

Ideally, the work environment at this stage will present individuals with puzzles, dilemmas, problems, and tasks that match their interests and passions, thus maximizing the probability that intrinsic motivation will remain high throughout the process ( Csikszentmihalyi, 1990 ). For example, from a young age, Phil Knight was passionate about running and gear that optimized the running experience; he sought out environments in which he could explore this domain. Whatever the domain, the environment should allow a high degree of autonomy ( Gagne & Deci, 2005 ), whereby the person feels free to follow new pathways and need not fear breaking out of established routines—whether formalized or implicit. There should also be an optimal level of challenge, in which work demands are neither well below nor well above the person’s current skills ( Csikszentmihalyi, 1997 ); it is at optimal levels of challenge that learning is most likely to occur ( Bandura, 1993 ). Ideally, the task or problem will have sufficient structure so that the person can engage with it productively but not so much structure that there is little room for anything surprising.

Within an existing organization, leaders at the highest level can engender the proper environment for Stage One by voicing support for entrepreneurial, creative, innovative behavior and then showing that support through actions that reward and recognize good new ideas—even when those ideas ultimately fail ( McGrath, 2001 ). In fact, one of the most effective means for triggering the learning described in the previous section is to laud the value of good-effort failures that naturally arise whenever people try radically new ideas. Leaders at all levels in an organization, down to immediate supervisors, should talk about the importance of creativity—and then walk the talk.

Lower-level leaders can play a particularly important role at Stage One by matching people to projects on the basis of not only their skills and experience but also their interests ( Amabile et al., 1996 ). Moreover, supervisors can greatly increase the probability that people will engage effectively with new problems to solve (and find hidden opportunities) if they put two structural supports in place. First, providing clear strategic direction toward meaningful goals lends purpose to the work ( Latham & Yukl, 1975 ); coupling that strategic direction with operational autonomy allows flexible exploration ( Ryan & Deci, 2000 ). Second, in forming teams to collaborate on a creative task, leaders should ensure a substantial degree of diversity in perspectives and disciplinary backgrounds among the members and then provide the teams with support for communicating effectively across their differences ( Mannix & Neale, 2005 ). With these structural conditions in place, people are more likely to question their taken-for-granted assumptions in deciding how to tackle the task before them.

Conversely, managers undermine intrinsic motivation and creativity if they establish a work environment that is marked by an emphasis on the status quo and on extrinsic motivators such as unrealistic deadlines ( Amabile, DeJong, & Lepper, 1976 ) and rewards that are dangled like carrots to induce employees to perform. And, although competition with other organizations can fuel intrinsic motivation by lending additional meaning to the work, win-lose competition within the organization can sap intrinsic motivation ( Deci, Betley, Kahle, Abrams, & Porac, 1981 ). Finally, rigid status structures in the organization can lead employees to consciously or unconsciously believe that certain assumptions may not be questioned and certain problem domains are off-limits to them ( Detert & Edmondson, 2011 ).

Startup entrepreneurs have the advantage and challenge of establishing their own work environment. As such, they should be conscious that they are developing long-term practices for the fellow members of their founding team and their earliest employees. Generally, the first employees are intrinsically motivated because there is little pecuniary reward at the outset. Even in the earliest days of a firm, founders can model and encourage the sort of freewheeling exploration and questioning of assumptions that characterize Stage One. They can look for partners and initial employees who are also passionate about the undertaking, and they can focus everyone’s competitive instincts on external entities rather than internal colleagues.

Stage Two: Preparation

Preparation in this context is the acquisition of knowledge within a relevant domain. It is accomplished by gathering information and resources to understand what has and has not been done to address the defined problem. Gaining a deep understanding of the problem space allows entrepreneurs to seize opportunities as well as sharpen the creative goal. Nike founder Phil Knight’s travels through Japan, including many visits to sporting goods stores, allowed him to identify a Japanese company and brand that could help bring his idea to fruition. Although he still had not actually established his own company before he traveled, his growing understanding of the culture enabled him to make a favorable deal with his targeted Japanese manufacturer based on a cold call.

For individuals who have a deep familiarity with the problem space, this stage can be a trivial one. An important exception to consider is that such individuals may face a different sort of challenge in the preparation stage: unlearning some of their familiar cognitive pathways and re-examining their assumptions. Experts who engage in creative endeavors can be stifled by the deeply ingrained mental representations they hold ( Runco, 1994 ), which may lead them to think they already know the answer.

Desired Behaviors for Preparation

The behaviors that can be most conducive to the preparation stage are, in some ways, distinct from the desired behaviors for problem/opportunity identification. They include perseverance ( Dweck, 1986 ), searching for and incorporating a wide range of information, and discarding preconceived notions as warranted by new information ( Piaget, 1966 ).

In her many iterations through the creative process to build Sittercity, Genevieve Thiers engaged in a range of preparation behaviors. Although she could not have known it at the time, her years of babysitting, including the junior year abroad at Oxford University, when she elected to be both a student and a nanny, served as excellent preparation. The wide range of information she gained about parents and their constraints, needs, and concerns served her well as she founded her company. This knowledge formed the broad foundation of domain-relevant skills that Thiers could immediately call to mind and upon which she built as she worked intensely on her startup.

Excited about her initial opportunity identification just before college graduation, Thiers did an Internet search to see if anyone was already offering such a service. Although she found websites for Babysitters.com and Sitters.com, neither was an operating business. In the summer of 2000, after Thiers had graduated from college and started her job at IBM, she spent her free time writing a business plan for Sittercity. She searched for relevant information during this phase, drawing on resources at the Boston office of the US Small Business Administration (SBA), and incorporated that information into her approach to preparing the business plan. By the fall of 2000, after Thiers had participated in three meetings with potential investors arranged by the SBA, she discarded her preconceived notion that external funding was the route to starting this business. She persevered, searching for other ways to fund Sittercity.

As new problems and opportunities arose, Thiers repeatedly dove into information gathering. As described earlier, when she noticed the puzzling fact that a few parents from outside of Boston were signing up for her service, which was then available only in Boston, she spent time talking with them to discover their underlying motivations. Later, when Sittercity’s major competitor, Babysitters.com, launched its site, she diligently monitored that site, as well as others that later appeared, to keep herself prepared to deal with competition.

An important resource on which Thiers drew in preparing to grow her business was her boyfriend, Dan Ratner, whom she met a few months after launching Sittercity. Ratner, although only a few years older than Thiers, had already been involved in more than one startup. His entrepreneurship experience, as well as his technical expertise, served as broad and deep sources of information and assistance for Thiers in the ensuing years. Eventually, in 2005, Ratner joined Sittercity as vice president. Thiers was CEO.

Learning Behaviors That Support Stage Two

The second stage of creativity can be viewed as adopting or calling up the routines of the domain; as such, it is subject to all the advantages and drawbacks of human minds as incredible learning machines. For experts, the second stage of creativity can be a trap when the routines of the domain become mental ruts ( Levitt & March, 1988 ). On the other hand, knowing a subject matter can free up cognitive resources to engage with it in multiple ways. This freedom is not typically available to novices during the learning process ( Bransford, Vye, Stevens, Kuhl, Schwartz, Bell, & Meltzoff, 2005 ). One of the great paradoxes of creativity is that expertise can be both a great source of and a substantial barrier to creative thinking. What makes the difference is whether the expert retains a learning mindset and continues to learn from the situations she encounters ( Feuerstein & Rand, 1974 ).

Novices face different challenges at Stage Two. The learning process is generally a social one, situated in a specific context ( Vygotsky & Cole, 1978 ). Studies on how novices become full participants in a community of practice have demonstrated that learning best occurs when individuals engage in the co-construction of knowledge in that community ( Lave & Wenger, 1991 ). As demonstrated in the partnership of Thiers and Ratner to build Sittercity, working with practiced professionals can help novices process vast amounts of new information in meaningful ways.

In the first stage of creativity, there is possible discomfort from surfacing deeply held beliefs and challenging the assumptions embedded within routines. In Stage Two, there can also be discomfort in the effort it takes to learn something new. For adults, context is particularly important in enhancing the intrinsic motivation needed to stay actively engaged in the often arduous learning process. For example, informal learning through problem solving ( Marsick & Yates, 2012 ) acquired in the “midst of action” is specific to the task at hand ( Raelin, 1997 ). This action learning is potent because it addresses challenges of transfer, which are common when employees attend external trainings and then struggle to apply what they’ve learned back in their job context. Action learning means paying particular attention to learning while actually doing one’s work.