Russell Millner/Alamy

Defend Our Planet and Most Vulnerable Species

Your donation today will be triple-matched to power NRDC’s next great chapter in protecting our ecosystems and saving imperiled wildlife.

What Are the Causes of Climate Change?

We can’t fight climate change without understanding what drives it.

Low water levels at Shasta Lake, California, following a historic drought in October 2021

Andrew Innerarity/California Department of Water Resources

- Share this page block

At the root of climate change is the phenomenon known as the greenhouse effect , the term scientists use to describe the way that certain atmospheric gases “trap” heat that would otherwise radiate upward, from the planet’s surface, into outer space. On the one hand, we have the greenhouse effect to thank for the presence of life on earth; without it, our planet would be cold and unlivable.

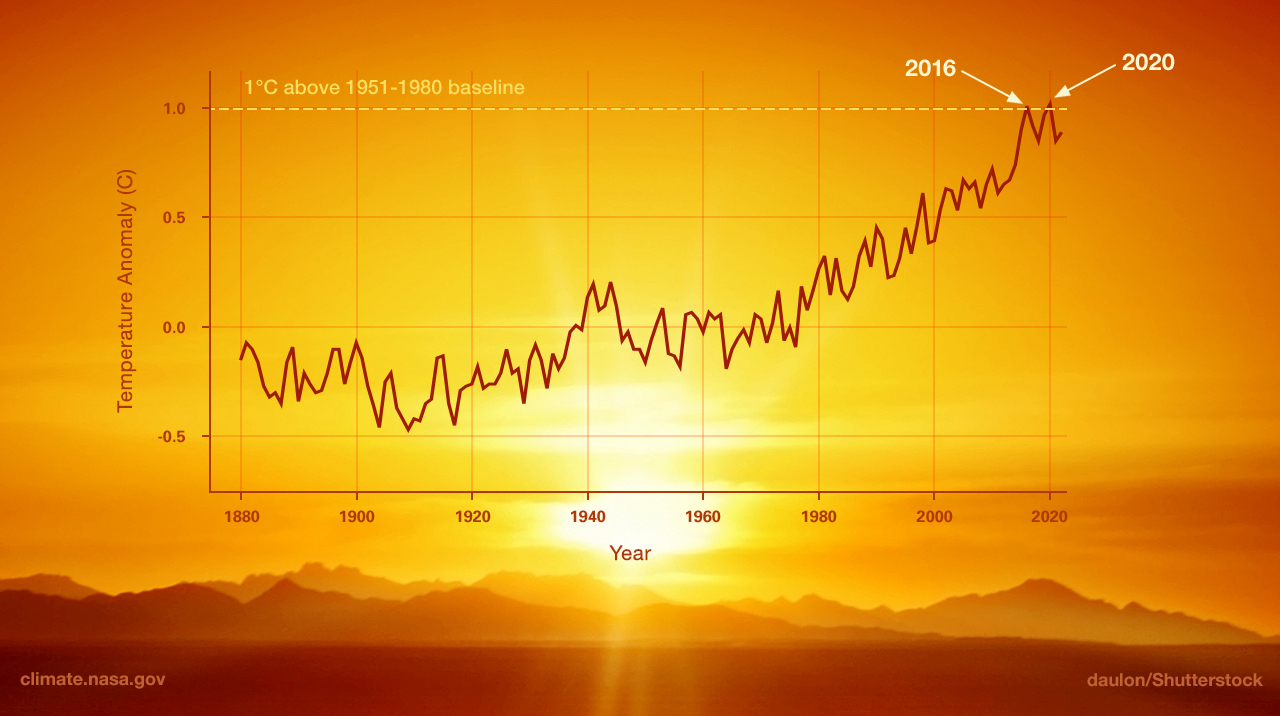

But beginning in the mid- to late-19th century, human activity began pushing the greenhouse effect to new levels. The result? A planet that’s warmer right now than at any other point in human history, and getting ever warmer. This global warming has, in turn, dramatically altered natural cycles and weather patterns, with impacts that include extreme heat, protracted drought, increased flooding, more intense storms, and rising sea levels. Taken together, these miserable and sometimes deadly effects are what have come to be known as climate change .

Detailing and discussing the human causes of climate change isn’t about shaming people, or trying to make them feel guilty for their choices. It’s about defining the problem so that we can arrive at effective solutions. And we must honestly address its origins—even though it can sometimes be difficult, or even uncomfortable, to do so. Human civilization has made extraordinary productivity leaps, some of which have led to our currently overheated planet. But by harnessing that same ability to innovate and attaching it to a renewed sense of shared responsibility, we can find ways to cool the planet down, fight climate change , and chart a course toward a more just, equitable, and sustainable future.

Here’s a rough breakdown of the factors that are driving climate change.

Natural causes of climate change

Human-driven causes of climate change, transportation, electricity generation, industry & manufacturing, agriculture, oil & gas development, deforestation, our lifestyle choices.

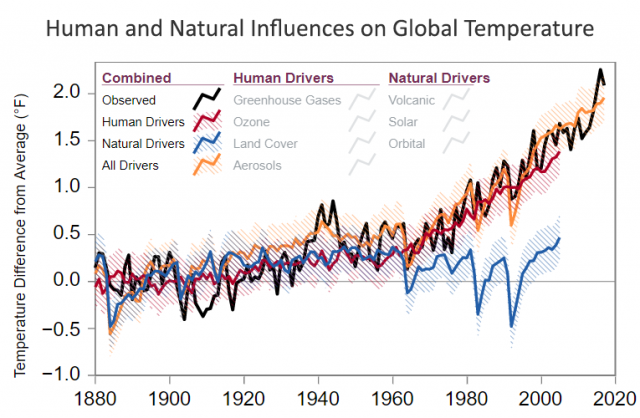

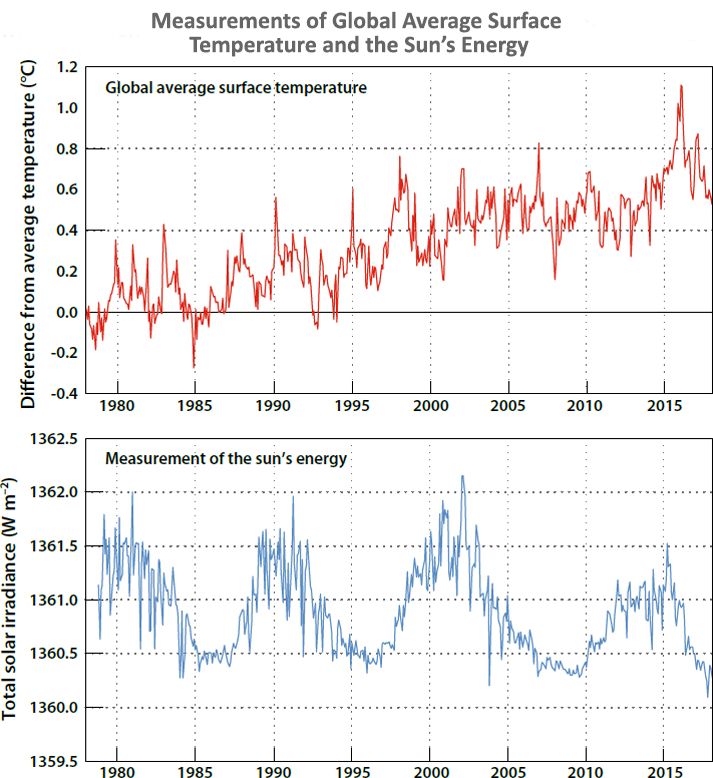

Some amount of climate change can be attributed to natural phenomena. Over the course of Earth’s existence, volcanic eruptions , fluctuations in solar radiation , tectonic shifts , and even small changes in our orbit have all had observable effects on planetary warming and cooling patterns.

But climate records are able to show that today’s global warming—particularly what has occured since the start of the industrial revolution—is happening much, much faster than ever before. According to NASA , “[t]hese natural causes are still in play today, but their influence is too small or they occur too slowly to explain the rapid warming seen in recent decades.” And the records refute the misinformation that natural causes are the main culprits behind climate change, as some in the fossil fuel industry and conservative think tanks would like us to believe.

Chemical manufacturing plants emit fumes along Onondaga Lake in Solvay, New York, in the late-19th century. Over time, industrial development severely polluted the local area.

Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Detroit Publishing Company Collection

Scientists agree that human activity is the primary driver of what we’re seeing now worldwide. (This type of climate change is sometimes referred to as anthropogenic , which is just a way of saying “caused by human beings.”) The unchecked burning of fossil fuels over the past 150 years has drastically increased the presence of atmospheric greenhouse gases, most notably carbon dioxide . At the same time, logging and development have led to the widespread destruction of forests, wetlands, and other carbon sinks —natural resources that store carbon dioxide and prevent it from being released into the atmosphere.

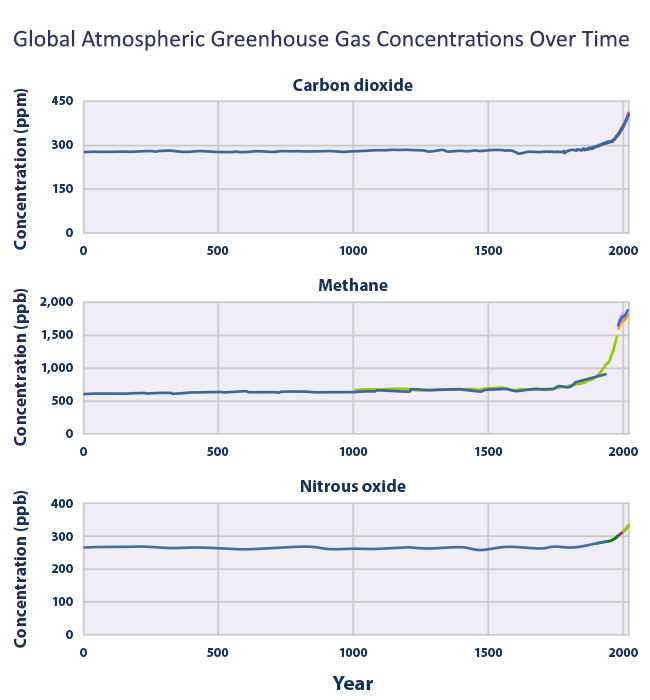

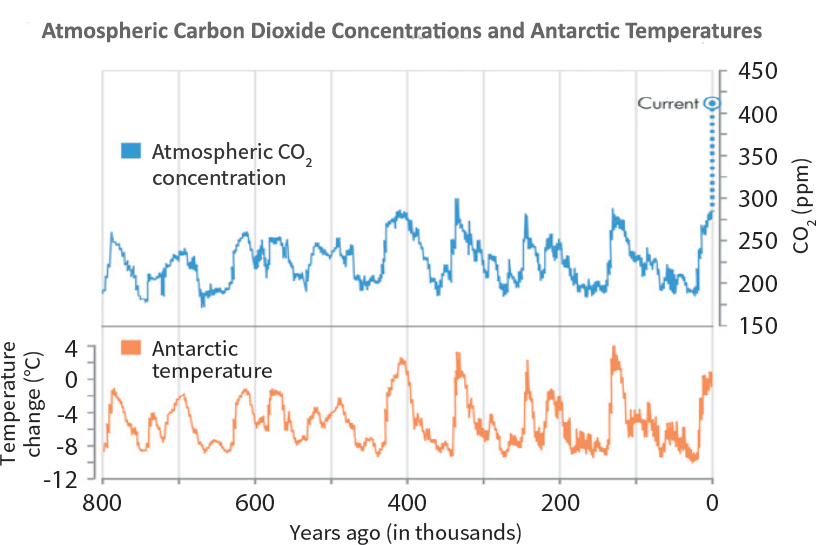

Right now, atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, methane , and nitrous oxide are the highest they’ve been in the last 800,000 years . Some greenhouse gases, like hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HFCs) , do not even exist in nature. By continuously pumping these gases into the air, we helped raise the earth’s average temperature by about 1.9 degrees Fahrenheit during the 20th century—which has brought us to our current era of deadly, and increasingly routine, weather extremes. And it’s important to note that while climate change affects everyone in some way, it doesn’t do so equally: All over the world, people of color and those living in economically disadvantaged or politically marginalized communities bear a much larger burden , despite the fact that these communities play a much smaller role in warming the planet.

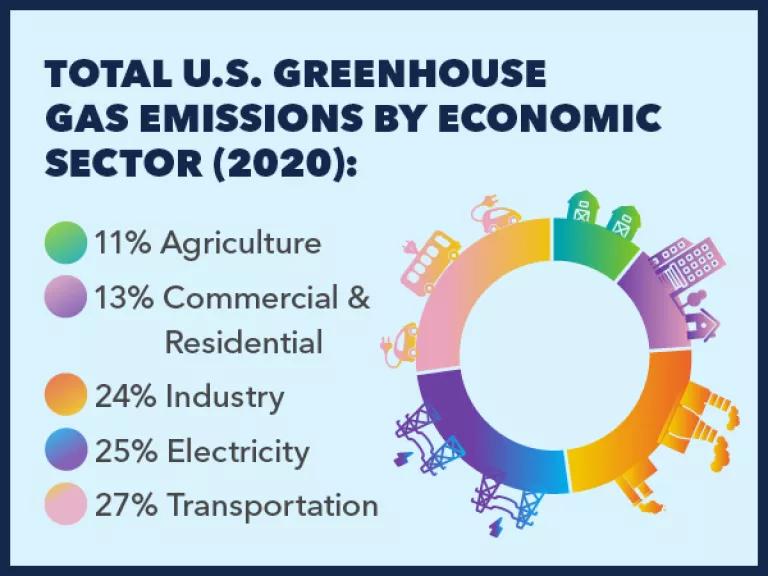

Our ways of generating power for electricity, heat, and transportation, our built environment and industries, our ways of interacting with the land, and our consumption habits together serve as the primary drivers of climate change. While the percentages of greenhouse gases stemming from each source may fluctuate, the sources themselves remain relatively consistent.

Traffic on Interstate 25 in Denver

David Parsons/iStock

The cars, trucks, ships, and planes that we use to transport ourselves and our goods are a major source of global greenhouse gas emissions. (In the United States, they actually constitute the single-largest source.) Burning petroleum-based fuel in combustion engines releases massive amounts of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Passenger cars account for 41 percent of those emissions, with the typical passenger vehicle emitting about 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year. And trucks are by far the worst polluters on the road. They run almost constantly and largely burn diesel fuel, which is why, despite accounting for just 4 percent of U.S. vehicles, trucks emit 23 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions from transportation.

We can get these numbers down, but we need large-scale investments to get more zero-emission vehicles on the road and increase access to reliable public transit .

As of 2021, nearly 60 percent of the electricity used in the United States comes from the burning of coal, natural gas , and other fossil fuels . Because of the electricity sector’s historical investment in these dirty energy sources, it accounts for roughly a quarter of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, including carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide.

That history is undergoing a major change, however: As renewable energy sources like wind and solar become cheaper and easier to develop, utilities are turning to them more frequently. The percentage of clean, renewable energy is growing every year—and with that growth comes a corresponding decrease in pollutants.

But while things are moving in the right direction, they’re not moving fast enough. If we’re to keep the earth’s average temperature from rising more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, which scientists say we must do in order to avoid the very worst impacts of climate change, we have to take every available opportunity to speed up the shift from fossil fuels to renewables in the electricity sector.

The factories and facilities that produce our goods are significant sources of greenhouse gases; in 2020, they were responsible for fully 24 percent of U.S. emissions. Most industrial emissions come from the production of a small set of carbon-intensive products, including basic chemicals, iron and steel, cement and concrete, aluminum, glass, and paper. To manufacture the building blocks of our infrastructure and the vast array of products demanded by consumers, producers must burn through massive amounts of energy. In addition, older facilities in need of efficiency upgrades frequently leak these gases, along with other harmful forms of air pollution .

One way to reduce the industrial sector’s carbon footprint is to increase efficiency through improved technology and stronger enforcement of pollution regulations. Another way is to rethink our attitudes toward consumption (particularly when it comes to plastics ), recycling , and reuse —so that we don’t need to be producing so many things in the first place. And, since major infrastructure projects rely heavily on industries like cement manufacturing (responsible for 7 percent of annual global greenhouse gas), policy mandates must leverage the government’s purchasing power to grow markets for cleaner alternatives, and ensure that state and federal agencies procure more sustainably produced materials for these projects. Hastening the switch from fossil fuels to renewables will also go a long way toward cleaning up this energy-intensive sector.

The advent of modern, industrialized agriculture has significantly altered the vital but delicate relationship between soil and the climate—so much so that agriculture accounted for 11 percent of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions in 2020. This sector is especially notorious for giving off large amounts of nitrous oxide and methane, powerful gases that are highly effective at trapping heat. The widespread adoption of chemical fertilizers , combined with certain crop-management practices that prioritize high yields over soil health, means that agriculture accounts for nearly three-quarters of the nitrous oxide found in our atmosphere. Meanwhile, large-scale industrialized livestock production continues to be a significant source of atmospheric methane, which is emitted as a function of the digestive processes of cattle and other ruminants.

Stephen McComber holds a squash harvested from the community garden in Kahnawà:ke Mohawk Territory, a First Nations reserve of the Mohawks of Kahnawà:ke, in Quebec.

Stephanie Foden for NRDC

But farmers and ranchers—especially Indigenous farmers, who have been tending the land according to sustainable principles —are reminding us that there’s more than one way to feed the world. By adopting the philosophies and methods associated with regenerative agriculture , we can slash emissions from this sector while boosting our soil’s capacity for sequestering carbon from the atmosphere, and producing healthier foods.

A decades-old, plugged and abandoned oil well at a cattle ranch in Crane County, Texas, in June 2021, when it was found to be leaking brine water

Matthew Busch/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Oil and gas lead to emissions at every stage of their production and consumption—not only when they’re burned as fuel, but just as soon as we drill a hole in the ground to begin extracting them. Fossil fuel development is a major source of methane, which invariably leaks from oil and gas operations : drilling, fracking , transporting, and refining. And while methane isn’t as prevalent a greenhouse gas as carbon dioxide, it’s many times more potent at trapping heat during the first 20 years of its release into the atmosphere. Even abandoned and inoperative wells—sometimes known as “orphaned” wells —leak methane. More than 3 million of these old, defunct wells are spread across the country and were responsible for emitting more than 280,000 metric tons of methane in 2018.

Unsurprisingly, given how much time we spend inside of them, our buildings—both residential and commercial—emit a lot of greenhouse gases. Heating, cooling, cooking, running appliances, and maintaining other building-wide systems accounted for 13 percent of U.S. emissions overall in 2020. And even worse, some 30 percent of the energy used in U.S. buildings goes to waste, on average.

Every day, great strides are being made in energy efficiency , allowing us to achieve the same (or even better) results with less energy expended. By requiring all new buildings to employ the highest efficiency standards—and by retrofitting existing buildings with the most up-to-date technologies—we’ll reduce emissions in this sector while simultaneously making it easier and cheaper for people in all communities to heat, cool, and power their homes: a top goal of the environmental justice movement.

An aerial view of clearcut sections of boreal forest near Dryden in Northwestern Ontario, Canada, in June 2019

River Jordan for NRDC

Another way we’re injecting more greenhouse gas into the atmosphere is through the clearcutting of the world’s forests and the degradation of its wetlands . Vegetation and soil store carbon by keeping it at ground level or underground. Through logging and other forms of development, we’re cutting down or digging up vegetative biomass and releasing all of its stored carbon into the air. In Canada’s boreal forest alone, clearcutting is responsible for releasing more than 25 million metric tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere each year—the emissions equivalent of 5.5 million vehicles.

Government policies that emphasize sustainable practices, combined with shifts in consumer behavior , are needed to offset this dynamic and restore the planet’s carbon sinks .

The Yellow Line Metro train crossing over the Potomac River from Washington, DC, to Virginia on June 24, 2022

Sarah Baker

The decisions we make every day as individuals—which products we purchase, how much electricity we consume, how we get around, what we eat (and what we don’t—food waste makes up 4 percent of total U.S. greenhouse gas emissions)—add up to our single, unique carbon footprints . Put all of them together and you end up with humanity’s collective carbon footprint. The first step in reducing it is for us to acknowledge the uneven distribution of climate change’s causes and effects, and for those who bear the greatest responsibility for global greenhouse gas emissions to slash them without bringing further harm to those who are least responsible .

The big, climate-affecting decisions made by utilities, industries, and governments are shaped, in the end, by us : our needs, our demands, our priorities. Winning the fight against climate change will require us to rethink those needs, ramp up those demands , and reset those priorities. Short-term thinking of the sort that enriches corporations must give way to long-term planning that strengthens communities and secures the health and safety of all people. And our definition of climate advocacy must go beyond slogans and move, swiftly, into the realm of collective action—fueled by righteous anger, perhaps, but guided by faith in science and in our ability to change the world for the better.

If our activity has brought us to this dangerous point in human history, breaking old patterns can help us find a way out.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

We need climate action to be a top priority in Washington!

Tell President Biden and Congress to slash climate pollution and reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.

Urge President Biden and Congress to make equitable climate action a top priority in 2024

Related stories.

Greenhouse Effect 101

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?

Failing to Meet Our Climate Goals Is Not an Option

When you sign up, you’ll become a member of NRDC’s Activist Network. We will keep you informed with the latest alerts and progress reports.

Search the United Nations

- What Is Climate Change

- Myth Busters

- Renewable Energy

- Finance & Justice

- Initiatives

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Paris Agreement

- Climate Ambition Summit 2023

- Climate Conferences

- Press Material

- Communications Tips

Causes and Effects of Climate Change

Fossil fuels – coal, oil and gas – are by far the largest contributor to global climate change, accounting for over 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 90 per cent of all carbon dioxide emissions. As greenhouse gas emissions blanket the Earth, they trap the sun’s heat. This leads to global warming and climate change. The world is now warming faster than at any point in recorded history. Warmer temperatures over time are changing weather patterns and disrupting the usual balance of nature. This poses many risks to human beings and all other forms of life on Earth.

Sacred plant helps forge a climate-friendly future in Paraguay

El Niño and climate crisis raise drought fears in Madagascar

The El Niño climate pattern, a naturally occurring phenomenon, can significantly disrupt global weather systems, but the human-made climate emergency is exacerbating the destructive effects.

“Verified for Climate” champions: Communicating science and solutions

Gustavo Figueirôa, biologist and communications director at SOS Pantanal, and Habiba Abdulrahman, eco-fashion educator, introduce themselves as champions for “Verified for Climate,” a joint initiative of the United Nations and Purpose to stand up to climate disinformation and put an end to the narratives of denialism, doomism, and delay.

Facts and figures

- What is climate change?

- Causes and effects

- Myth busters

Cutting emissions

- Explaining net zero

- High-level expert group on net zero

- Checklists for credibility of net-zero pledges

- Greenwashing

- What you can do

Clean energy

- Renewable energy – key to a safer future

- What is renewable energy

- Five ways to speed up the energy transition

- Why invest in renewable energy

- Clean energy stories

- A just transition

Adapting to climate change

- Climate adaptation

- Early warnings for all

- Youth voices

Financing climate action

- Finance and justice

- Loss and damage

- $100 billion commitment

- Why finance climate action

- Biodiversity

- Human Security

International cooperation

- What are Nationally Determined Contributions

- Acceleration Agenda

- Climate Ambition Summit

- Climate conferences (COPs)

- Youth Advisory Group

- Action initiatives

- Secretary-General’s speeches

- Press material

- Fact sheets

- Communications tips

Home — Essay Samples — Environment — Climate Change — Climate Change: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

Climate Change: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

- Categories: Climate Change

About this sample

Words: 663 |

Published: Jan 29, 2024

Words: 663 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

Introduction, causes of climate change, effects of climate change, efforts to combat climate change, challenges and future outlook.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). " Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis." IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, 2021. https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). "The Paris Agreement." UNFCCC, 2015. https://unfccc.int/process-and-meetings/the-paris-agreement/the-paris-agreement

- United Nations. "Sustainable Development Goals." United Nations, https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Verified writer

- Expert in: Environment

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 574 words

2 pages / 793 words

2 pages / 842 words

3 pages / 1381 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Climate Change

Climate change has been widely discussed over the past few decades. The climate crisis is the result of human activities that have been detrimental to our planet's ecosystem, leading to severe consequences that are felt [...]

The issue of climate change has become one of the most pressing challenges facing humanity today. Among the many factors contributing to global climate change, there is a widely accepted claim that human activities, particularly [...]

Climate change refers to the long-term alteration in Earth's climate due to human activities, such as the emission of greenhouse gases and deforestation. This issue is of great importance as it poses a threat to the well-being [...]

Hartmann D.L., Klein Tank A.M.G., Rusticuccie M., Alexander L.(2013) Chapter 2: Observations: Atmosphere and Surface. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment [...]

The impact of climate change in Bangladesh, discussed in this essay, is a pressing issue due to the country's vulnerability to natural disasters. Bangladesh's low land, high population, and poverty make it [...]

As we stand on the precipice of a changing world, it becomes increasingly important for us to understand the gravity of the situation we face. Climate change, a phenomenon that has been the subject of much debate and [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

view all topics > Climate change

Humans are causing global warming

What Is Climate Change?

Climate change is a long-term change in the average weather patterns that have come to define Earth’s local, regional and global climates. These changes have a broad range of observed effects that are synonymous with the term.

Changes observed in Earth’s climate since the mid-20th century are driven by human activities, particularly fossil fuel burning, which increases heat-trapping greenhouse gas levels in Earth’s atmosphere, raising Earth’s average surface temperature. Natural processes, which have been overwhelmed by human activities, can also contribute to climate change, including internal variability (e.g., cyclical ocean patterns like El Niño, La Niña and the Pacific Decadal Oscillation) and external forcings (e.g., volcanic activity, changes in the Sun’s energy output , variations in Earth’s orbit ).

Scientists use observations from the ground, air, and space, along with computer models , to monitor and study past, present, and future climate change. Climate data records provide evidence of climate change key indicators, such as global land and ocean temperature increases; rising sea levels; ice loss at Earth’s poles and in mountain glaciers; frequency and severity changes in extreme weather such as hurricanes, heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, floods, and precipitation; and cloud and vegetation cover changes.

“Climate change” and “global warming” are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings. Similarly, the terms "weather" and "climate" are sometimes confused, though they refer to events with broadly different spatial- and timescales.

What Is Global Warming?

Global warming is the long-term heating of Earth’s surface observed since the pre-industrial period (between 1850 and 1900) due to human activities, primarily fossil fuel burning, which increases heat-trapping greenhouse gas levels in Earth’s atmosphere. This term is not interchangeable with the term "climate change."

Since the pre-industrial period, human activities are estimated to have increased Earth’s global average temperature by about 1 degree Celsius (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit), a number that is currently increasing by more than 0.2 degrees Celsius (0.36 degrees Fahrenheit) per decade. The current warming trend is unequivocally the result of human activity since the 1950s and is proceeding at an unprecedented rate over millennia.

Weather vs. Climate

“if you don’t like the weather in new england, just wait a few minutes.” - mark twain.

Weather refers to atmospheric conditions that occur locally over short periods of time—from minutes to hours or days. Familiar examples include rain, snow, clouds, winds, floods, or thunderstorms.

Climate, on the other hand, refers to the long-term (usually at least 30 years) regional or even global average of temperature, humidity, and rainfall patterns over seasons, years, or decades.

Find Out More: A Guide to NASA’s Global Climate Change Website

This website provides a high-level overview of some of the known causes, effects and indications of global climate change:

Evidence. Brief descriptions of some of the key scientific observations that our planet is undergoing abrupt climate change.

Causes. A concise discussion of the primary climate change causes on our planet.

Effects. A look at some of the likely future effects of climate change, including U.S. regional effects.

Vital Signs. Graphs and animated time series showing real-time climate change data, including atmospheric carbon dioxide, global temperature, sea ice extent, and ice sheet volume.

Earth Minute. This fun video series explains various Earth science topics, including some climate change topics.

Other NASA Resources

Goddard Scientific Visualization Studio. An extensive collection of animated climate change and Earth science visualizations.

Sea Level Change Portal. NASA's portal for an in-depth look at the science behind sea level change.

NASA’s Earth Observatory. Satellite imagery, feature articles and scientific information about our home planet, with a focus on Earth’s climate and environmental change.

Header image is of Apusiaajik Glacier, and was taken near Kulusuk, Greenland, on Aug. 26, 2018, during NASA's Oceans Melting Greenland (OMG) field operations. Learn more here . Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Discover More Topics From NASA

Explore Earth Science

Earth Science in Action

Earth Science Data

Facts About Earth

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Climate change.

Climate change is a long-term shift in global or regional climate patterns. Often climate change refers specifically to the rise in global temperatures from the mid-20th century to present.

Earth Science, Climatology

Fracking tower

Fracking is a controversial form of drilling that uses high-pressure liquid to create cracks in underground shale to extract natural gas and petroleum. Carbon emissions from fossils fuels like these have been linked to global warming and climate change.

Photograph by Mark Thiessen / National Geographic

Climate is sometimes mistaken for weather. But climate is different from weather because it is measured over a long period of time, whereas weather can change from day to day, or from year to year. The climate of an area includes seasonal temperature and rainfall averages, and wind patterns. Different places have different climates. A desert, for example, is referred to as an arid climate because little water falls, as rain or snow, during the year. Other types of climate include tropical climates, which are hot and humid , and temperate climates, which have warm summers and cooler winters.

Climate change is the long-term alteration of temperature and typical weather patterns in a place. Climate change could refer to a particular location or the planet as a whole. Climate change may cause weather patterns to be less predictable. These unexpected weather patterns can make it difficult to maintain and grow crops in regions that rely on farming because expected temperature and rainfall levels can no longer be relied on. Climate change has also been connected with other damaging weather events such as more frequent and more intense hurricanes, floods, downpours, and winter storms.

In polar regions, the warming global temperatures associated with climate change have meant ice sheets and glaciers are melting at an accelerated rate from season to season. This contributes to sea levels rising in different regions of the planet. Together with expanding ocean waters due to rising temperatures, the resulting rise in sea level has begun to damage coastlines as a result of increased flooding and erosion.

The cause of current climate change is largely human activity, like burning fossil fuels , like natural gas, oil, and coal. Burning these materials releases what are called greenhouse gases into Earth’s atmosphere . There, these gases trap heat from the sun’s rays inside the atmosphere causing Earth’s average temperature to rise. This rise in the planet's temperature is called global warming. The warming of the planet impacts local and regional climates. Throughout Earth's history, climate has continually changed. When occuring naturally, this is a slow process that has taken place over hundreds and thousands of years. The human influenced climate change that is happening now is occuring at a much faster rate.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Yale Program on Climate Change Communication

- About YPCCC

- Yale Climate Connections

- Student Employment

- For The Media

- Past Events

- YPCCC in the News

- Climate Change in the American Mind (CCAM)

- Publications

- Climate Opinion Maps

- Climate Opinion Factsheets

- Six Americas Super Short Survey (SASSY)

- Resources for Educators

- All Tools & Interactives

- Partner with YPCCC

Home / For Educators: Grades 6-12 / Climate Explained: Introductory Essays About Climate Change Topics

Climate Explained: Introductory Essays About Climate Change Topics

Filed under: backgrounders for educators ,.

Climate Explained, a part of Yale Climate Connections, is an essay collection that addresses an array of climate change questions and topics, including why it’s cold outside if global warming is real, how we know that humans are responsible for global warming, and the relationship between climate change and national security.

More Activities like this

Climate Change Basics: Five Facts, Ten Words

Backgrounders for Educators

To simplify the scientific complexity of climate change, we focus on communicating five key facts about climate change that everyone should know.

Why should we care about climate change?

Having different perspectives about global warming is natural, but the most important thing that anyone should know about climate change is why it matters.

External Resources

Looking for resources to help you and your students build a solid climate change science foundation? We’ve compiled a list of reputable, student-friendly links to help you do just that!

Subscribe to our mailing list

Please select all the ways you would like to hear from Yale Program on Climate Change Communication:

You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the link in the footer of our emails. For information about our privacy practices, please visit our website.

We use Mailchimp as our marketing platform. By clicking below to subscribe, you acknowledge that your information will be transferred to Mailchimp for processing. Learn more about Mailchimp's privacy practices here.

- Share full article

You Asked, We Answered: Some Burning Climate Questions

Reporters from the Climate Desk gathered reader questions and are here to help explain some frequent puzzlers.

What’s one thing you want to know about climate change? We asked, and hundreds of you responded.

The topic, like the planet, is vast. Overwhelming. Complex. But there’s no more important time to understand what is happening and what can be done about it.

Why are extreme cold weather events happening if the planet is warming?

I understand that scientists believe that some extreme cold weather events are due to climate change, but I don’t quite understand how, especially if Earth is getting warmer overall. Could you explain this? — Gabriel Gutierrez, West Lafayette, Ind.

By Maggie Astor

The connection between climate change and extreme cold weather involves the polar jet stream in the Northern Hemisphere, strong winds that blow around the globe from west to east at an altitude of 5 to 9 miles. The jet stream naturally shifts north and south, and when it shifts south, it brings frigid Arctic air with it.

A separate wind system, called the polar vortex , forms a ring around the North Pole. When the vortex is temporarily disrupted — sometimes stretched or elongated, and other times broken into pieces — the jet stream tends to take one of those southward shifts. And research “suggests these disruptions to the vortex are happening more often in connection with a rapidly warming, melting Arctic, which we know is a clear symptom of climate change,” said Jennifer A. Francis, a senior scientist at the Woodwell Climate Research Center.

In other words, as climate change makes the Arctic warmer, the polar vortex is being more frequently disrupted in ways that allow Arctic air to escape south. And while temperatures are increasing on average, Arctic air is still frigid much of the time. Certainly frigid enough to cause extreme cold snaps in places like, say, Texas that are not accustomed to or prepared for them.

Where the extreme cold occurs depends on the nature of the disruption to the polar vortex. One type of disruption brings Arctic air into Europe and Asia. Another type brings Arctic air into the United States, and “that’s the type of polar vortex disruption that’s increasing the fastest,” said Judah L. Cohen, the director of seasonal forecasting at Atmospheric and Environmental Research, a private organization that works with government agencies.

It is important to note that these atmospheric patterns are extremely complicated, and while studies have shown a clear correlation between the climate-change-fueled warming of the Arctic and these extreme cold events, there is some disagreement among scientists about whether the warming of the Arctic is directly causing the extreme cold events. Research on that question is ongoing.

How will climate change affect biodiversity?

What impact will climate change have on biodiversity? How are they interlinked? How do the roles of developing versus developed countries differ, for example the United States and India? — A reader in India

By Catrin Einhorn

Warmer oceans are killing corals . Rising sea levels threaten the beaches that sea turtles need for nesting, and hotter temperatures are causing more females to be born. Changing seasons are increasingly out of step with the conditions species have evolved to depend on.

And then there are the polar bears , long a symbol of what could be lost in a warming world.

Climate change is already affecting plants and animals in ways that scientists are racing to understand. One study predicted sudden die offs , with large segments of ecosystems collapsing in waves. This has already started in coral reefs, scientists say, and could start in tropical forests by the 2040s.

Keeping global warming under 2 degrees Celsius, or 3.6 degrees Fahrenheit, the upper limit outlined by the Paris Agreement, would reduce the number of species exposed to dangerous climate change by 60 percent, the study found.

Despite these grim predictions, climate change isn’t yet the biggest driver of biodiversity loss. On land, the largest factor is the ways in which people have reshaped the terrain itself, creating farms and ranches, towns and cities, roads and mines from what was once habitat for myriad species. At sea, the main cause of biodiversity loss is overfishing. Also at play: pollution, introduced species that outcompete native ones, and hunting. A sobering report in 2019 by the leading international authority on biodiversity found that around a million species were at risk of extinction, many within decades.

While climate change will increasingly drive species loss, that’s not the only way in which the two are interlinked. Last year the same biodiversity panel joined with its climate change counterpart to issue a paper declaring that neither crisis could be addressed effectively on its own. For example, intact ecosystems like peatlands and forests both nurture biodiversity and sequester carbon; destroy them, and they turn into emitters of greenhouse gasses as well as lost habitat.

What to do? The science is clear that the world must transition away from fossil fuels far more quickly than is happening. Deforestation must stop . Consuming less meat and dairy would free up farmland for restoration , providing habitat for species and stashing away carbon. Ultimately, many experts say, we need a transformation from an extraction-based economy to a circular one. Like nature’s cycle, our waste — old clothes, old smartphones, old furniture — must be designed to provide the building blocks of what comes next.

Countries around the world are working on a new United Nations biodiversity agreement , which is expected to be approved later this year. One sticking point: How much money wealthy countries are willing to give poorer ones to protect intact natural areas, since wealthy countries have already largely exploited theirs.

Advertisement

What’s the status of U.S. climate legislation and emissions?

Where is the trimmed back version of climate legislation at? Joe Manchin reportedly said he would support such a bill. What do you know about the bill and will it pass with just Democrats? — Richard Buttny, Virgil, N.Y.

What is the current stated U.S. goal regarding reducing greenhouse gases and climate change, and how likely is it that we will achieve that goal? What do we need to do today to make progress toward achieving that goal? — Kathy Gray, Oak Ridge, Tenn.

By Lisa Friedman

Richard, as to the last part of your question, honestly, at this point your guess is as good as ours.

But here is what we know so far. Senator Joe Manchin III, Democrat of West Virginia, the most powerful man in Congress because his support in an evenly divided Senate is key, effectively killed President Biden’s Build Back Better climate and social spending legislation when he ended months of negotiations last year, saying he could not support the package .

A few weeks ago amid talks of revived discussions, Mr. Manchin was blunt. “There is no Build Back Better legislation,” he told reporters. Mr. Manchin also has not committed to passing a smaller version of the original $1 trillion spending plan. He has, however, voiced support for an “all of the above” energy package that increases oil and gas development.

Democrats hope that billions of dollars in tax incentives for wind, solar, geothermal and electric vehicle charging stations can also make its way into such a package. But relations between the White House and Mr. Manchin are rocky and it is unclear whether such a bill could pass before lawmakers leave town for an August recess.

To your emissions question, Kathy, Mr. Biden has pledged to cut United States emissions 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 . Energy experts say it is a challenging but realistic goal, and critical for helping the world avert the worst impacts of climate change.

It’s not going to be easy. So far there are few regulations and even fewer laws that can help achieve that target. Mr. Biden’s centerpiece legislation, the Build Back Better Act, includes $550 billion in clean energy tax incentives that researchers said could get the country about halfway to its goal. But, as noted, that bill is stalled in the Senate . Even if it manages to win approval this year, the administration will still have to enact regulations on things like power plants and automobile emissions to meet the target.

Will our drinking water be safe?

A lot of coverage on climate change deals with rising sea levels and extreme weather — droughts, floods, etc. My question is more about how climate change will affect drinking water and access to safe clean water. Are we in danger within our current lifetime to see an impact to safe water within the U.S. due to climate change? — Jessica, Silver Spring, Md.

By Christopher Flavelle

Climate change threatens Americans’ access to clean drinking water in a number of ways. The most obvious is drought: Rising temperatures are reducing the snowpack that supplies drinking water for much of the West.

But drought is far from the only climate-related threat to America’s water. Along the coast, cities like Miami that draw drinking water from underground aquifers have to worry about rising seas pushing saltwater into those aquifers , a process called saltwater intrusion. And rising seas also push up groundwater levels, which can cause septic systems to stop working, pushing unfiltered human waste into that groundwater.

Even in cities far from the coast, worsening floods are overwhelming aging sewer systems , causing untreated storm water and sewage to reach rivers and streams more frequently . And some 2,500 chemical sites are in areas at risk of flooding, which could cause those chemicals to leach into the groundwater.

In some cases, protecting drinking water from the effects of climate change is possible, so long as governments can find enough money to upgrade infrastructure — building new systems to contain storm water, for example, or better protect chemicals from being released during a flood.

Far harder will be finding new supplies of water to make up for what’s lost as temperatures rise. Some communities are responding by pumping more water from the ground. But if those aquifers are depleted faster than rainwater can replenish them, they will eventually run dry, a concern with the Ogallala Aquifer that supports much of the High Plains.

Even with significant reductions in water use, climate change could reduce the number of people that some regions can support, and leave more areas dependent on importing water.

Can you solve drought by piping water across the country?

Why don’t we create a national acequia system to capture excess rain falling primarily in the Eastern United States and pipeline it to the drought in the West? — Carol P. Chamberland, Albuquerque, N.M

The idea of taking water from one community and giving it to another has some basis in American history. In 1913, Los Angeles opened an aqueduct to carry water from Owens Valley, 230 miles north of the city, to sustain its growth.

But the project, in addition to costing some $23 million at the time, greatly upset Owens Valley residents, who so resented losing their water that they took to dynamiting the aqueduct. Repeatedly .

Today, there are some enormous water projects in the United States, though building a pipeline that spanned a significant stretch of the country would be astronomically more difficult. The distance between Albuquerque, for example, and the Mississippi River — perhaps the closest hypothetical starting point for such a pipeline — is about 1,000 miles, crossing at least three states along the way. Moving that water all the way to Los Angeles would mean piping it at least 1,800 miles across five states.

So the engineering and permitting challenges alone would be daunting. And that’s assuming the local and state governments that would have to give up their water would be willing to do so.

China dealt with similar challenges to build a colossal network of waterways that is transferring water from the country’s humid south to its dry north. But of course, China’s system of government makes engineering feats of that scale somewhat more feasible to pull off.

For the United States, it would be easier to just build a series of desalination plants along the West coast, according to Greg Pierce, director of the Human Right to Water Solutions Lab at the University of California, Los Angeles. And before turning to desalination, which is itself energy-intensive and thus expensive, communities in the West should work harder at other steps, such as water conservation and recycling, he said.

“It’s not worth it,” Dr. Pierce said of the pipeline idea. “You’d have to exhaust eight other options first.”

Is the weather becoming more extreme than scientists predicted?

How can we have faith in climate modeling when extreme events are much worse than predicted? Given “unexpected” extreme events like the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave and extreme heat in Antarctica that appear to shock scientists, it’s difficult for me to trust the I.P.C.C.’s framing that we haven’t run out of time. — Kevin, Herndon, Va.

By Raymond Zhong

Climate scientists have said for a long time that global warming is causing the intensity and frequency of many types of extreme weather to increase. And that’s exactly what has been happening. But global climate models aren’t really designed to simulate extreme events in individual regions. The factors that shape individual heat waves, for instance, are very local. Large-scale computer models simply can’t handle that level of detail quite yet.

That said, sometimes there are events that seem so anomalous that they make scientists wonder if they reflect something totally new and unforeseen, a gap in our understanding of the climate. Some researchers put the 2021 Pacific Northwest heat wave in that category, and are working to figure out whether they need to re-evaluate some of their assumptions.

For its part, the I.P.C.C. has hardly failed to acknowledge what’s happening with extreme weather. But its mandate is to assess the whole range of climate research, which might make it lean toward the middle of the road in its summaries. A decade ago, when a group of researchers looked back at the panel’s assessments from the early 2000s, they found that it generally underestimated the actual changes in sea level rise, increases in surface temperatures, intensity of rainfall and more. They blamed the instinct of scientists to avoid making conclusions that seem “excessively dramatic,” perhaps out of fear of being called alarmist.

The panel’s latest report, from April , concluded that we haven’t run out of time to slow global warming, but only if nations and societies make some huge changes right away. That’s a big if.

How can I hear from climate scientists themselves?

Why are climate change scientists faceless, aloof, terrible communicators and absent from social media? — A reader in Dallas

Climate science may not yet have its Bill Nye or its Neil deGrasse Tyson, but plenty of climate scientists are passionate about communicating their work to the public. Lots of them are on Twitter. Here’s a (very small) cross-section of people to follow, in alphabetical order:

Alaa Al Khourdajie : Senior scientist in London with the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the body of experts convened by the United Nations that puts out regular, authoritative surveys of climate research. Tweets on climate change economics and climate diplomacy.

Andrew Dessler : Professor of atmospheric sciences at Texas A&M University. Elucidator of energy and renewables, climate models and Texas.

Zeke Hausfather : Climate research lead at the payment processing company Stripe and scientist at Berkeley Earth, a nonprofit research group. A seemingly tireless chronicler, charter and commentator on all things climate.

David Ho : Climate scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa and École Normale Supérieure in Paris. Talks oceans and carbon dioxide removal, with wry observations on transit, cycling and life in France, too.

Twila Moon : Deputy lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo. Covers glaciers, polar regions and giant ice sheets, and why we should all care about what happens to them.

Maisa Rojas : Climatologist at the University of Chile and Chile’s current environment minister. Follow along for slices of life at the intersection of science and government policy.

Sonia I. Seneviratne : Professor of land-climate dynamics at ETH Zurich in Switzerland. Tweets on extreme weather, greenhouse gas emissions and European energy policy.

Chandni Singh : Researcher on climate adaptation at the Indian Institute for Human Settlements in Bangalore. Posts about how countries and communities are coping with climate change, in both helpful ways and not so helpful ones.

Kim Wood : Geoscientist and meteorologist at Mississippi State University. A fount of neat weather maps and snarky GIFs.

What kind of trees are best to plant for the planet?

The world is trying to reforest the planet by planting nonnative trees like eucalyptus. Is this another disastrous plan? Shouldn’t they be planting native trees? — Katy Green, Nashville

Ecologists would say planting native trees is the best choice. We recently published an article on this very topic , examining how tree planting can resurrect or devastate ecosystems, depending on what species are planted and where.

To be sure, people need wood and other tree products for all kinds of reasons, and sometimes nonnative species make sense. But even when the professed goal is to help nature, the commercial benefits of certain trees, like Australian eucalyptus in Africa and South America or North American Sitka spruce in Europe, often win out.

A new standard is in development that would score tree planting projects on how well they’re doing with regard to biodiversity, with the aim of helping those with poor scores to improve.

The same ecological benefit of planting native species also holds true for people’s yards. Doug Tallamy, a professor of entomology at the University of Delaware, worked with the National Wildlife Federation to develop this tool to help people find native trees, shrubs and flowers that support the most caterpillars, which in turn feed baby birds .

Can we engineer solutions to atmospheric warming?

Why are we not investing in scalable solutions that can remove carbon or reduce solar radiation? — Hayes Morehouse, Hayward, Calif.

By Henry Fountain

As a group, these types of solutions are referred to as geoengineering, or intentional manipulation of the climate. Geoengineering generally falls into two categories: removing some of the carbon dioxide already in the atmosphere so Earth traps less heat, known as direct air capture, or reducing how much sunlight reaches Earth’s surface so that there is less heat to begin with, usually called solar radiation management.

There are a few companies developing direct air capture machines, and some have deployed them on a small scale. According to the International Energy Agency, these projects capture a total of about 10 thousand tons of CO2 a year, a tiny fraction of the roughly 35 billion tons of annual energy-related emissions. Removing enough CO2 to have a climate impact would take a long time and require many thousands of machines, all of which would need energy to operate.

The captured gas would also have to be securely stored to keep it from re-entering the atmosphere. Those hurdles make direct air capture a long shot, especially since, for now at least, there are few financial incentives to overcome them. No one wants to pay to remove carbon dioxide from the air and bury it underground.

Solar radiation management is a different story. The basics of how to do it are known: inject some kind of chemical (perhaps sulfur dioxide) into the upper atmosphere, where it would reflect more of the sun’s rays. Relatively speaking, it wouldn’t be all that expensive (a fleet of high-flying planes would probably suffice) although once started it would have to continue indefinitely.

The major hurdle to developing the technology has been grave concern among many scientists, policymakers and others about unintended consequences that might result, and about the lack of a structure to govern its deployment. To date, there have been almost no real-world studies of the technology .

How do we know how warm the planet was in the 1800s?

One key finding of climate science is that global temperatures have increased by 2 degrees Fahrenheit since the late 1800s. How can we possibly have reliable measures of global temperatures from back then, keeping in mind that oceans cover about 70 percent of the globe and that a large majority of land has never been populated by humans to any significant degree? — Robert, Madison, Wis.

The mercury thermometer was invented in the early 1700s, and by the mid- to late 19th century, local temperatures were being monitored continuously in many locations, predominantly in the United States, Europe and the British colonies. By 1900, there were hundreds of recording stations worldwide, but over half of the Southern Hemisphere still wasn’t covered. And the techniques could be primitive. To measure temperatures at the sea’s surface, for instance, the most common method before about 1940 was to toss a bucket overboard a ship, haul it back up with a rope and read the temperature of the water inside.

To turn these spotty local measurements into estimates of average temperatures globally, across both land and ocean, climate scientists have had to perform some highly delicate analysis . They’ve used statistical models to fill in the gaps in direct readings. They’ve taken into account when weather stations changed locations or were situated close to cities that were hot for reasons unrelated to larger temperature trends.

They have also used some clever techniques to try to correct for antiquated equipment and methods. Those bucket readings , for example, might be inaccurate because the water in the bucket cooled down as it was pulled aboard. So scientists have scoured various nations’ maritime archives to determine what materials their sailors’ buckets were made of — tin, wood, canvas, rubber — during different periods in history and adjusted the way they incorporate those temperature recordings into their computations.

Such analysis is fiendishly tricky. The numbers that emerge are uncertain estimates, not gospel truth. Scientists are working constantly to refine them. Today’s global temperature measurements are based on a much broader and more quality-controlled set of readings, including from ships and buoys in the oceans.

But having a historical baseline, even an imperfect one, is important. As Roy L. Jenne, a researcher at the National Center for Atmospheric Research, wrote in a 1975 report on the institution’s collections of climate data: “Although they are not perfect, if they are used wisely they can help us find answers to a number of problems.”

Does producing batteries for electric cars damage the environment more than gas vehicles do?

Is the environmental damage collecting metals/producing batteries for electric cars more dangerous to the environment than gas powered vehicles? — Sandy Rogers, San Antonio, Texas

By Hiroko Tabuchi

There’s no question that mining the metals and minerals used in electric car batteries comes with sizable costs that are not just environmental but also human.

Much of the world’s cobalt, for example, is mined in the Democratic Republic of Congo , where corruption and worker exploitation has been widespread. Extracting the metals from their ores also requires a process called smelting, which can emit sulfur oxide and other harmful air pollution.

Beyond the minerals required for batteries, electric grids still need to become much cleaner before electric vehicles are emissions free.

Most electric vehicles sold today already produce significantly fewer planet-warming emissions than most cars fueled with gasoline, but a lot still depends on how much coal is being burned to generate the electricity they use.

Still, consider that batteries and other clean technology require relatively tiny amounts of these critical minerals, and that’s only to manufacture them. Once a battery is in use, there are no further minerals necessary to sustain it. That’s a very different picture from oil and gas, which must constantly be drilled from the ground, transported via pipelines and tankers, refined and combusted in our gasoline cars to keep those cars moving, said Jim Krane, a researcher at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy in Houston. In terms of environmental and other impacts, he said, “There’s just no comparison.”

How close are alternatives to fuel-powered aircraft?

As E. V.s are to gas-powered cars, are there greener alternatives to fuel-powered planes that are close to commercialization? — Rashmi Sarnaik, Boston

There are alternatives to fossil-fuel-powered aircraft in development, but whether they are close to commercialization depends on how you define “close.” It’s probably fair to say that the day when a significant amount of air travel is on low- or zero-emissions planes is still far-off.

There has been some work on using hydrogen , including burning it in modified jet engines. Airbus and the engine manufacturer CFM International expect to begin flight testing a hydrogen-fueled engine by the middle of the decade.

As with cars, though, most of the focus in aviation has been on electric power and batteries. The main problem with batteries is how little energy they supply relative to their weight. In cars that’s less of an obstacle (they don’t have to get off the ground, after all) but in aviation, batteries severely limit the size of the plane and how far it can fly.

One of the biggest battery-powered planes to fly so far was a modified Cessna Grand Caravan, test-flown by two companies, Magnix and Aerotec. Turboprop Grand Caravans can carry 10 or more people up to 1,200 miles. The companies said theirs could fly four or five people 100 miles or less.

The limitations of batteries, at least for now, have led some companies to work on other designs. Some use fuel cells, which work like batteries but can continuously supply electricity using hydrogen or other fuel. Others use hybrid systems — like hybrid cars, combining batteries and fossil-fuel-powered engines. In one approach, the engines provide some power and also keep the batteries charged. In another, the engines are used in takeoff and descent, when more power is needed, and the batteries for cruising, which requires less power. That keeps the number of batteries, and the weight, down.

Can countries meet the goals they set in the Paris agreement?

What countries, if any, have a realistic chance of meeting their Paris agreement pledges? — Michael Svetly, Philadelphia

According to Climate Action Tracker , a research group that analyzes climate goals and policies, very few. Ahead of United Nations talks in Glasgow last year, the organization found most major emitters of carbon dioxide, including the United States and China, are falling short of their pledge to stabilize global warming around 1.5 degrees Celsius, or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit.

A few are doing better than most, including Costa Rica and the United Kingdom. Just one country was on track to meet its promises: Gambia, a small West African nation that has been bolstering its renewable energy use.

What will happen to N.Y.C.?

How is N.Y.C. planning for relocation or redevelopment, or both, of its many low-lying neighborhoods as floodwaters become too high to levee? — A reader in North Bergen, N.J.

New York City has yet to announce plans to fully relocate entire neighborhoods threatened by climate change, with all the steps that would entail: determining which homes to buy, getting agreement from homeowners, finding a new patch of land for the community, building new infrastructure, securing funding and so on.

Relocation projects on that scale, often described as “managed retreat,” remain extremely rare in the United States. What projects have been attempted so far have mostly been in rural areas or small towns , and their success has been mixed.

And the idea of pulling back from the water, while never easy, is especially fraught in New York City, which has some of the highest real estate values in the country. Those high values have been used to justify fantastically expensive projects to protect low-lying land in the city, rather than abandon it — like a $10 billion berm along the South Street Seaport , or a $119 billion sea wall in New York Harbor .

Perhaps unsurprisingly, then, the city’s most recent Comprehensive Waterfront Plan , issued in December, makes no mention of managed retreat. But the plan does include what it calls “housing mobility” — policies aimed at helping individual households move to safer areas, for example by giving people money to buy a new home on higher ground, as well as paying for moving and other costs. The city also says it is limiting the density of new development in high-risk areas.

Robert Freudenberg, a vice president of the Regional Plan Association, a nonprofit planning group in New York, New Jersey and Connecticut, gave city officials credit for beginning to talk about the idea that some areas can’t be protected forever.

“It’s an extremely challenging topic,” Mr. Freudenberg said. But as flooding gets worse, he added, “we can’t not talk about it.”

As oceans rise, will the Great Lakes, too?

The oceans are predicted to rise and affect coastal areas and cities, however, does this rise also affect the coastal areas of the Great Lakes, as the lakes are connected to the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River and one would have to assume they would eventually be impacted? — Terri Messinides, Madison, Wis.

The Great Lakes are not directly threatened by rising oceans because of their elevation: The lowest of them, Lake Ontario, is about 240 feet above sea level. The St. Lawrence River carries water from the lakes to the Atlantic Ocean, but because of the elevation change, rising waters in the Atlantic can’t travel in the other direction.

That said, climate change is causing increasingly frequent and intense storms in the Great Lakes region, and the effects, including higher water levels and more flooding, are in many respects the same as those caused by rising seas. It’s just a different manifestation of climate change.

When it comes to precipitation, the past five years, from April 2017 through March 2022, the last month for which complete data is available, have been the second-wettest on record for the Great Lakes Basin, according to records kept by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration . The water has risen accordingly. In 2019, water levels in the lakes hit 100-year highs , causing severe flooding and shoreline erosion.

At the same time, higher temperatures increase the rate of evaporation, which can lead to abnormally low water levels. People who live around the Great Lakes can expect to see both extremes — high water driven by severe rainfall, and low water driven by evaporation — happen more often as the climate continues to warm.

What is the environmental cost of cryptocurrency?

Can you tell us about the damage being done to our environment by crypto mining? I’ve heard the mining companies are trying to switch to renewable energy, yet at the same time reopening old coal power plants to provide the huge amounts of electricity they need. — Barry Engelman, Santa Monica, Calif.

Cryptomining, the enigmatic way in which virtual cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are created (and which is also behind technology like NFTs ), requires a whole lot of computing power, is highly energy-intensive and generates outsize emissions. We delved into that process, and its environmental impact in this article — but suffice to say the problem isn’t going away soon.

The way Bitcoin is set up, using a process called “proof of work,” means that as interest in cryptocurrencies grows and more people start mining, more energy is required to mine a single Bitcoin. Researchers at Cambridge University estimate that mining Bitcoin uses more electricity than midsize countries like Norway. In New York, an influx of Bitcoin miners has led to the reopening of mothballed power plants.

But you might wonder about the traditional financial system: doesn’t that use energy, too? Yes, of course. But Bitcoin, for all its hype, still makes up just a few percent of all the world’s money or its transactions. So even though one industry study estimated that Bitcoin consumes about a 10th of the energy required by the traditional banking system, that still means Bitcoin’s energy use is outsize.

To address its high emissions footprint, cryptomining has increasingly tapped into renewable forms of energy, like hydroelectric power. But figuring out exactly just how much renewable energy Bitcoin miners use can be tricky. For one, we don’t exactly know where many of these miners are. We do know a lot of crypto miners used to be in China, where they had access to large amounts of hydro power. But now that they’ve largely been kicked out, cryptomining’s global climate impact has likely gotten worse .

In the United States, cryptominers have started to tap an unconventional new energy source: drilled gas, collected at oil and gas wells. The miners argue that this gas would otherwise have been flared or vented into the atmosphere, so no excess emissions are created. The reality is not that clear cut: If the presence of those cryptominers disincentivizes oil and gas companies from piping away that gas to be used elsewhere, any savings effect is blunted.

Other efforts are afoot to make cryptomining less damaging for the environment, including an alternative way of cryptomining involving a process called “proof of stake,” that doesn’t require miners to use as much energy. But unless Bitcoin, the most popular cryptocurrency, switches over, that’s going to do little to dent miners’ energy use.

How much do volcanoes contribute to global warming?

What does the data look like for greenhouse gas emissions in the last 200 years if volcanic activity was subtracted out? — Haley Rowlands, Boston

Volcanic activity generates 130 million to 440 million tons of carbon dioxide per year, according to the United States Geological Survey . Human activity generates about 35 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year — 80 times as much as the high-end estimate for volcanic activity, and 270 times as much as the low-end estimate. And that’s carbon dioxide. Human activity also emits other greenhouse gases, like methane, in far greater quantities than volcanoes.

The largest volcanic eruption in the past century was the 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines; if an explosion that size happened every day, NASA has calculated , it would still release only half as much carbon dioxide as daily human activity does. The annual emissions from cement production alone, one small component of planet-warming human activity, are greater than the annual emissions from every volcano in the world.

There is also no evidence that volcanic activity has increased over the past 200 years. While there have been more documented eruptions, researchers at the Smithsonian Institution’s Global Volcanism Program found that this was attributable not to an actual trend, but rather to “increases in populations living near volcanoes to observe eruptions and improvements in communication technologies to report those eruptions.”

All told, volcanic activity accounts for less than 1 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, which is not enough to contribute in any meaningful way to the increase we’ve seen over the past 200 years. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found in 2013 (see Page 56 of its report ) that the climatic effects of volcanic activity were “inconsequential” over the scale of a century.

Do carbon dioxide concentrations vary around the globe?

Why is the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere at Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii used as the global reference? It’s only one point on Earth. Do concentrations vary between different parts of the world? — Evan, Boston

At any given moment, levels of carbon dioxide in the air vary from place to place, depending on the amount of vegetation and human activity nearby. Which is why, as a location to monitor the average state of the atmosphere, at least over a large part of the Northern Hemisphere, a barren volcano in the middle of the Pacific has much to offer. It’s high above the ground and far enough from major sources of industrial pollution but still relatively accessible to researchers.

Today, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration studies global carbon dioxide levels by looking at readings from Mauna Loa Observatory and a variety of other sources. These include observatories in Alaska, American Samoa and the South Pole, tall towers across the United States, and samples collected by balloons, aircraft and volunteers around the world. ( Here’s a map of all those sites.)

NOAA also checks its measurements at Mauna Loa against others from the same location, including ones taken independently, using different methods, by the Scripps Institution of Oceanography . On average, the difference in their monthly estimates is tiny.

Could a ‘new ice age’ offset global warming?

Will increases in global temperature associated with climate change be mitigated by the coming of a new “ice age?” — Suzanne Smythe, Essex, Conn.

In a “mini ice age,” if it occurred, average worldwide temperatures would drop, thus offsetting the warming that has been caused by emissions of greenhouse gases from the burning of fossil fuels in the last century and a half.

It’s a nice thought: a natural phenomenon comes to our rescue. But it’s not happening, nor is it expected to.

The idea is linked to the natural variability in the amount of the sun’s energy that reaches Earth. The sun goes through regular cycles, lasting about 11 years, when activity swings from a minimum to a maximum. But there are also longer periods of reduced activity, called grand solar minimums. The last one began in the mid-17th century and lasted seven decades.

There is some debate among scientists whether we are entering a new grand minimum . But even if we are, and even if it lasted for a century, the reduction in the sun’s output would not have a significant effect on temperatures. NASA scientists, among others, have calculated that any cooling effect would be overwhelmed by the warming effect of all the greenhouse gases we have pumped, and continue to pump, into the atmosphere.

An official website of the United States government

Here’s how you know

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock A locked padlock ) or https:// means you’ve safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

JavaScript appears to be disabled on this computer. Please click here to see any active alerts .

Causes of Climate Change

Since the Industrial Revolution, human activities have released large amounts of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere, which has changed the earth’s climate. Natural processes, such as changes in the sun's energy and volcanic eruptions, also affect the earth's climate. However, they do not explain the warming that we have observed over the last century. 1

Human Versus Natural Causes

It is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land . - Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 4

Scientists have pieced together a record of the earth’s climate by analyzing a number of indirect measures of climate, such as ice cores, tree rings, glacier lengths, pollen remains, and ocean sediments, and by studying changes in the earth’s orbit around the sun. 2 This record shows that the climate varies naturally over a wide range of time scales, but this variability does not explain the observed warming since the 1950s. Rather, it is extremely likely (> 95%) that human activities have been the dominant cause of that warming. 3

Human activities have contributed substantially to climate change through:

- Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Reflectivity or Absorption of the Sun’s Energy

Heat-trapping greenhouse gases and the earth's climate, greenhouse gases.

Concentrations of the key greenhouse gases have all increased since the Industrial Revolution due to human activities. Carbon dioxide, methane, and nitrous oxide concentrations are now more abundant in the earth’s atmosphere than any time in the last 800,000 years. 5 These greenhouse gas emissions have increased the greenhouse effect and caused the earth’s surface temperature to rise . Burning fossil fuels changes the climate more than any other human activity.

Carbon dioxide: Human activities currently release over 30 billion tons of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere every year. 6 Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations have increased by more than 40 percent since pre-industrial times, from approximately 280 parts per million (ppm) in the 18th century 7 to 414 ppm in 2020. 8

Methane: Human activities increased methane concentrations during most of the 20th century to more than 2.5 times the pre-industrial level, from approximately 722 parts per billion (ppb) in the 18th century 9 to 1,867 ppb in 2019. 10

Nitrous oxide: Nitrous oxide concentrations have risen approximately 20 percent since the start of the Industrial Revolution, with a relatively rapid increase toward the end of the 20th century. Nitrous oxide concentrations have increased from a pre-industrial level of 270 ppb 11 to 332 ppb in 2019. 12

For more information on greenhouse gas emissions, see the Greenhouse Gas Emissions website. To learn more about actions that can reduce these emissions, see What You Can Do . To translate abstract greenhouse gas emissions measurements into concrete terms, try using EPA's Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator .

Activities such as agriculture, road construction, and deforestation can change the reflectivity of the earth's surface, leading to local warming or cooling. This effect is observed in heat islands , which are urban centers that are warmer than the surrounding, less populated areas. One reason that these areas are warmer is that buildings, pavement, and roofs tend to reflect less sunlight than natural surfaces. While deforestation can increase the earth’s reflectivity globally by replacing dark trees with lighter surfaces such as crops, the net effect of all land-use changes appears to be a small cooling. 13

Emissions of small particles, known as aerosols, into the air can also lead to reflection or absorption of the sun's energy. Many types of air pollutants undergo chemical reactions in the atmosphere to create aerosols. Overall, human-generated aerosols have a net cooling effect on the earth. Learn more about human-generated and natural aerosols .

Natural Processes

Natural processes are always influencing the earth’s climate and can explain climate changes prior to the Industrial Revolution in the 1700s. However, recent climate changes cannot be explained by natural causes alone.

Changes in the Earth’s Orbit and Rotation

Changes in the earth’s orbit and its axis of rotation have had a big impact on climate in the past. For example, the amount of summer sunshine on the Northern Hemisphere, which is affected by changes in the planet’s orbit, appears to be the primary cause of past cycles of ice ages, in which the earth has experienced long periods of cold temperatures (ice ages), as well as shorter interglacial periods (periods between ice ages) of relatively warmer temperatures. 14 At the coldest part of the last glacial period (or ice age), the average global temperature was about 11°F colder than it is today. At the peak of the last interglacial period, however, the average global temperature was at most 2°F warmer than it is today. 15

Variations in Solar Activity