- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Ancient Rome

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 22, 2023 | Original: October 14, 2009

Beginning in the eighth century B.C., Ancient Rome grew from a small town on central Italy’s Tiber River into an empire that at its peak encompassed most of continental Europe, Britain, much of western Asia, northern Africa and the Mediterranean islands. Among the many legacies of Roman dominance are the widespread use of the Romance languages (Italian, French, Spanish, Portuguese and Romanian) derived from Latin, the modern Western alphabet and calendar and the emergence of Christianity as a major world religion.

After 450 years as a republic, Rome became an empire in the wake of Julius Caesar’s rise and fall in the first century B.C. The long and triumphant reign of its first emperor, Augustus, began a golden age of peace and prosperity; by contrast, the Roman Empire’s decline and fall by the fifth century A.D. was one of the most dramatic implosions in the history of human civilization.

Origins of Rome

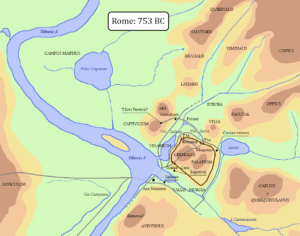

As legend has it, Rome was founded in 753 B.C. by Romulus and Remus, twin sons of Mars, the god of war. Left to drown in a basket on the Tiber by a king of nearby Alba Longa and rescued by a she-wolf, the twins lived to defeat that king and found their own city on the river’s banks in 753 B.C. After killing his brother, Romulus became the first king of Rome, which is named for him.

A line of Sabine, Latin and Etruscan (earlier Italian civilizations) kings followed in a non-hereditary succession. There are seven legendary kings of Rome: Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Martius, Lucius Tarquinius Priscus (Tarquin the Elder), Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus, or Tarquin the Proud (534-510 B.C.). While they were referred to as “Rex,” or “King” in Latin, all the kings after Romulus were elected by the senate.

Did you know? Four decades after Constantine made Christianity Rome's official religion, Emperor Julian—known as the Apostate—tried to revive the pagan cults and temples of the past, but the process was reversed after his death, and Julian was the last pagan emperor of Rome.

Rome’s era as a monarchy ended in 509 B.C. with the overthrow of its seventh king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, whom ancient historians portrayed as cruel and tyrannical, compared to his benevolent predecessors. A popular uprising was said to have arisen over the rape of a virtuous noblewoman, Lucretia, by the king’s son. Whatever the cause, Rome turned from a monarchy into a republic, a world derived from res publica , or “property of the people.”

Rome was built on seven hills, known as “the seven hills of Rome”—Esquiline Hill, Palatine Hill, Aventine Hill, Capitoline Hill, Quirinal Hill, Viminal Hill and Caelian Hill.

The Early Republic

The power of the monarch passed to two annually elected magistrates called consuls. They also served as commanders in chief of the army. The magistrates, though elected by the people, were drawn largely from the Senate, which was dominated by the patricians, or the descendants of the original senators from the time of Romulus. Politics in the early republic was marked by the long struggle between patricians and plebeians (the common people), who eventually attained some political power through years of concessions from patricians, including their own political bodies, the tribunes, which could initiate or veto legislation.

In 450 B.C., the first Roman law code was inscribed on 12 bronze tablets–known as the Twelve Tables–and publicly displayed in the Roman Forum . These laws included issues of legal procedure, civil rights and property rights and provided the basis for all future Roman civil law. By around 300 B.C., real political power in Rome was centered in the Senate, which at the time included only members of patrician and wealthy plebeian families.

Military Expansion

During the early republic, the Roman state grew exponentially in both size and power. Though the Gauls sacked and burned Rome in 390 B.C., the Romans rebounded under the leadership of the military hero Camillus, eventually gaining control of the entire Italian peninsula by 264 B.C. Rome then fought a series of wars known as the Punic Wars with Carthage, a powerful city-state in northern Africa.

The first two Punic Wars ended with Rome in full control of Sicily, the western Mediterranean and much of Spain. In the Third Punic War (149–146 B.C.), the Romans captured and destroyed the city of Carthage and sold its surviving inhabitants into slavery, making a section of northern Africa a Roman province. At the same time, Rome also spread its influence east, defeating King Philip V of Macedonia in the Macedonian Wars and turning his kingdom into another Roman province.

Rome’s military conquests led directly to its cultural growth as a society, as the Romans benefited greatly from contact with such advanced cultures as the Greeks. The first Roman literature appeared around 240 B.C., with translations of Greek classics into Latin; Romans would eventually adopt much of Greek art, philosophy and religion.

Internal Struggles in the Late Republic

Rome’s complex political institutions began to crumble under the weight of the growing empire, ushering in an era of internal turmoil and violence. The gap between rich and poor widened as wealthy landowners drove small farmers from public land, while access to government was increasingly limited to the more privileged classes. Attempts to address these social problems, such as the reform movements of Tiberius and Gaius Gracchus (in 133 B.C. and 123-22 B.C., respectively) ended in the reformers’ deaths at the hands of their opponents.

Gaius Marius, a commoner whose military prowess elevated him to the position of consul (for the first of six terms) in 107 B.C., was the first of a series of warlords who would dominate Rome during the late republic. By 91 B.C., Marius was struggling against attacks by his opponents, including his fellow general Sulla, who emerged as military dictator around 82 B.C. After Sulla retired, one of his former supporters, Pompey, briefly served as consul before waging successful military campaigns against pirates in the Mediterranean and the forces of Mithridates in Asia. During this same period, Marcus Tullius Cicero , elected consul in 63 B.C., famously defeated the conspiracy of the patrician Cataline and won a reputation as one of Rome’s greatest orators.

Julius Caesar’s Rise

When the victorious Pompey returned to Rome, he formed an uneasy alliance known as the First Triumvirate with the wealthy Marcus Licinius Crassus (who suppressed a slave rebellion led by Spartacus in 71 B.C.) and another rising star in Roman politics: Gaius Julius Caesar . After earning military glory in Spain, Caesar returned to Rome to vie for the consulship in 59 B.C. From his alliance with Pompey and Crassus, Caesar received the governorship of three wealthy provinces in Gaul beginning in 58 B.C.; he then set about conquering the rest of the region for Rome.

After Pompey’s wife Julia (Caesar’s daughter) died in 54 B.C. and Crassus was killed in battle against Parthia (present-day Iran) the following year, the triumvirate was broken. With old-style Roman politics in disorder, Pompey stepped in as sole consul in 53 B.C. Caesar’s military glory in Gaul and his increasing wealth had eclipsed Pompey’s, and the latter teamed with his Senate allies to steadily undermine Caesar. In 49 B.C., Caesar and one of his legions crossed the Rubicon, a river on the border between Italy from Cisalpine Gaul. Caesar’s invasion of Italy ignited a civil war from which he emerged as dictator of Rome for life in 45 B.C.

From Caesar to Augustus

Less than a year later, Julius Caesar was murdered on the ides of March (March 15, 44 B.C.) by a group of his enemies (led by the republican nobles Marcus Junius Brutus and Gaius Cassius). Consul Mark Antony and Caesar’s great-nephew and adopted heir, Octavian, joined forces to crush Brutus and Cassius and divided power in Rome with ex-consul Lepidus in what was known as the Second Triumvirate. With Octavian leading the western provinces, Antony the east, and Lepidus Africa, tensions developed by 36 B.C. and the triumvirate soon dissolved. In 31 B.C., Octavian triumped over the forces of Antony and Queen Cleopatra of Egypt (also rumored to be the onetime lover of Julius Caesar) in the Battle of Actium. In the wake of this devastating defeat, Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide.

By 29 B.C., Octavian was the sole leader of Rome and all its provinces. To avoid meeting Caesar’s fate, he made sure to make his position as absolute ruler acceptable to the public by apparently restoring the political institutions of the Roman republic while in reality retaining all real power for himself. In 27 B.C., Octavian assumed the title of Augustus , becoming the first emperor of Rome.

Age of the Roman Emperors

Augustus’ rule restored morale in Rome after a century of discord and corruption and ushered in the famous pax Romana –two full centuries of peace and prosperity. He instituted various social reforms, won numerous military victories and allowed Roman literature, art, architecture and religion to flourish. Augustus ruled for 56 years, supported by his great army and by a growing cult of devotion to the emperor. When he died, the Senate elevated Augustus to the status of a god, beginning a long-running tradition of deification for popular emperors.

Augustus’ dynasty included the unpopular Tiberius (A.D. 14-37), the bloodthirsty and unstable Caligula (37-41) and Claudius (41-54), who was best remembered for his army’s conquest of Britain. The line ended with Nero (54-68), whose excesses drained the Roman treasury and led to his downfall and eventual suicide.

Four emperors took the throne in the tumultuous year after Nero’s death; the fourth, Vespasian (69-79), and his successors, Titus and Domitian, were known as the Flavians; they attempted to temper the excesses of the Roman court, restore Senate authority and promote public welfare. Titus (79-81) earned his people’s devotion with his handling of recovery efforts after the infamous eruption of Vesuvius, which destroyed the towns of Herculaneum and Pompeii .

The reign of Nerva (96-98), who was selected by the Senate to succeed Domitian, began another golden age in Roman history, during which four emperors–Trajan, Hadrian, Antoninus Pius, and Marcus Aurelius–took the throne peacefully, succeeding one another by adoption, as opposed to hereditary succession. Trajan (98-117) expanded Rome’s borders to the greatest extent in history with victories over the kingdoms of Dacia (now northwestern Romania) and Parthia. His successor Hadrian (117-138) solidified the empire’s frontiers (famously building Hadrian's Wall in present-day England) and continued his predecessor’s work of establishing internal stability and instituting administrative reforms.

Under Antoninus Pius (138-161), Rome continued in peace and prosperity, but the reign of Marcus Aurelius (161–180) was dominated by conflict, including war against Parthia and Armenia and the invasion of Germanic tribes from the north. When Marcus fell ill and died near the battlefield at Vindobona (Vienna), he broke with the tradition of non-hereditary succession and named his 19-year-old son Commodus as his successor.

Decline and Disintegration

The decadence and incompetence of Commodus (180-192) brought the golden age of the Roman emperors to a disappointing end. His death at the hands of his own ministers sparked another period of civil war , from which Lucius Septimius Severus (193-211) emerged victorious. During the third century Rome suffered from a cycle of near-constant conflict. A total of 22 emperors took the throne, many of them meeting violent ends at the hands of the same soldiers who had propelled them to power. Meanwhile, threats from outside plagued the empire and depleted its riches, including continuing aggression from Germans and Parthians and raids by the Goths over the Aegean Sea.

The reign of Diocletian (284-305) temporarily restored peace and prosperity in Rome, but at a high cost to the unity of the empire. Diocletian divided power into the so-called tetrarchy (rule of four), sharing his title of Augustus (emperor) with Maximian. A pair of generals, Galerius and Constantius, were appointed as the assistants and chosen successors of Diocletian and Maximian; Diocletian and Galerius ruled the eastern Roman Empire, while Maximian and Constantius took power in the west.

The stability of this system suffered greatly after Diocletian and Maximian retired from office. Constantine (the son of Constantius) emerged from the ensuing power struggles as sole emperor of a reunified Rome in 324. He moved the Roman capital to the Greek city of Byzantium, which he renamed Constantinople . At the Council of Nicaea in 325, Constantine made Christianity (once an obscure Jewish sect) Rome’s official religion.

Roman unity under Constantine proved illusory, and 30 years after his death the eastern and western empires were again divided. Despite its continuing battle against Persian forces, the eastern Roman Empire–later known as the Byzantine Empire –would remain largely intact for centuries to come. An entirely different story played out in the west, where the empire was wracked by internal conflict as well as threats from abroad–particularly from the Germanic tribes now established within the empire’s frontiers like the Vandals (their sack of Rome originated the phrase “vandalism”)–and was steadily losing money due to constant warfare.

Rome eventually collapsed under the weight of its own bloated empire, losing its provinces one by one: Britain around 410; Spain and northern Africa by 430. Attila and his brutal Huns invaded Gaul and Italy around 450, further shaking the foundations of the empire. In September 476, a Germanic prince named Odovacar won control of the Roman army in Italy. After deposing the last western emperor, Romulus Augustus, Odovacar’s troops proclaimed him king of Italy, bringing an ignoble end to the long, tumultuous history of ancient Rome. The fall of the Roman Empire was complete.

Roman Architecture

Roman architecture and engineering innovations have had a lasting impact on the modern world. Roman aqueducts, first developed in 312 B.C., enabled the rise of cities by transporting water to urban areas, improving public health and sanitation. Some Roman aqueducts transported water up to 60 miles from its source and the Fountain of Trevi in Rome still relies on an updated version of an original Roman aqueduct.

Roman cement and concrete are part of the reason ancient buildings like the Colosseum and Roman Forum are still standing strong today. Roman arches, or segmented arches, improved upon earlier arches to build strong bridges and buildings, evenly distributing weight throughout the structure.

Roman roads, the most advanced roads in the ancient world, enabled the Roman Empire—which was over 1.7 million square miles at the pinnacle of its power—to stay connected. They included such modern-seeming innovations as mile markers and drainage. Over 50,000 miles of road were built by 200 B.C. and several are still in use today.

HISTORY Vault: Rome: Rise and Fall of an Empire

History of the ancient Roman Empire.

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

Ancient Rome

Find out why this ancient civilization is still important more than 2,000 years after its fall.

Tens of thousands of Romans take their seats in an enormous stadium made of stone and concrete. It’s the year 80, and these people are entering the newly built Colosseum for the first time. Men wearing togas and women in long dresses called stolas will spend the next hundred days watching gladiator games and wild animal fights to celebrate the opening of this amphitheater.

These ancient people were living in the center of a vast empire that spanned across Europe , northern Africa , and parts of the Middle East. Lasting over a thousand years, the ancient Roman civilization contributed to modern languages, government, architecture, and more.

History of ancient Rome

Around the ninth or tenth century B.C., Rome was just a small town on the Tiber River in what’s now central Italy . (One myth says that the town was founded by two brothers—Romulus and Remus—who were raised by a wolf.) For about 500 years, the area was ruled by a series of kings as it grew in strength and power.

But around the year 509 B.C., the last king was overthrown, and Rome became a republic. That meant that some citizens could vote for their leaders and other important matters. Only male Roman citizens could cast votes; women and enslaved people—often brought back as prisoners from military battles—could not.

Elected officials included two consuls who acted sort of like today’s U.S. presidents and kept each other from taking too much power. Both consuls worked with senators, who advised the consuls and helped create laws. Senators were appointed by other officials and could hold their positions for life.

The Roman army fought many wars during this period, first conquering all of what’s now Italy. In 146 B.C., they destroyed the city of Carthage (in modern-day Tunisia, in northern Africa), which was Rome’s greatest rival for trade in the western Mediterranean Sea. Next they conquered Greece.

For 500 years, the republic system mostly worked. But then a series of civil wars divided the people. In 59 B.C., Gaius Julius Caesar, a politician and military general, used the chaos to take power. Serving as consul, Caesar made new laws that benefitted his troops and other regular citizens. Then he conquered what’s now France and invaded Britain .

Even though his troops and many Roman citizens supported him, the Senate worried he was too powerful and wanted him gone. Knowing this, Caesar marched his loyal army into Rome. It was an illegal act that started a civil war, which Caesar would eventually win.

At first, he was named dictator for 10 years. (Before that, a dictator served during times of emergencies for only six months.) He canceled people’s debts and granted Roman citizenship to people outside of Italy so they could vote. Caesar also traveled to Egypt , making an alliance with the pharaoh Cleopatra.

In 44 B.C., Caesar named himself dictator for life. Fearing he was becoming a king, a group of senators killed him on the floor of the Senate. Caesar was gone, but his supporters chased down the assassins. His heir and nephew, Octavian, and general Mark Anthony battled for power.

Octavian eventually won and renamed himself Augustus Caesar. (The family name, Caesar, would become a title that future emperors would use to connect themselves back to Gaius Julius Caesar.) He convinced the Senate to give him absolute power and served successfully for 45 years. After his death, he was declared a god.

For the rest of its existence, Rome was ruled by emperors who were not elected—they reigned for life. The Senate was still part of the government, but it had very little power. Some emperors, like Claudius, were good at their jobs; others, like Nero and Caligula, were so cruel that even their guards turned against them.

By A.D. 117, the Roman Empire included what’s now France, Spain , Greece , Egypt, Turkey , parts of northern Africa, England, Romania, and more. At one point, one out of every four people in the world lived under Rome’s control.

But emperors and the Senate found this vast empire difficult to rule from the city of Rome. In the year 285, it was split into a Western Roman Empire and an Eastern Roman Empire. Known as the Byzantine Empire, the Eastern Roman Empire was ruled from the city of Constantinople, now the modern-day city of Istanbul in Turkey.

The Byzantine Empire would last for almost another thousand years, but the Western Empire—Rome—began to fall apart. Civil wars, plagues, money troubles, and invasions from other groups made the empire unstable. In the year 476, a Germanic king overthrew Romulus Augustus, the last Roman emperor.

Life in ancient Rome

Most people in the city of Rome lived in crowded apartment buildings called insulae that were five to seven stories high. Wealthier Romans lived in houses called domus that had a dining room and an atrium—an open-air courtyard that often had a pool at the center. Some Romans even had vacation homes in Pompeii and Herculaneum, two Roman cities that were destroyed when Mount Vesuvius erupted in A.D. 79.

Rich or poor, Romans gathered to relax, socialize, and clean themselves at Roman baths. Like modern spas, these structures had exercise rooms, swimming pools, saunas, hot and cold plunge pools, and massage spaces. The people also gathered to watch plays, chariot races, and gladiator battles.

Roman citizens enjoyed relaxing, but enslaved people in ancient Rome had a much more difficult life. Many worked in fields, mines, and on ships. Others, like educated Greeks who tutored wealthy children, were forced to work in rich people’s homes. However, some enslaved people were able to buy or earn their freedom and eventually become Roman citizens.

Roman women sometimes worked as midwives—helping to deliver babies—or became priestesses. But in Roman society, women’s main role was to look after the home and family. Although Romans could easily get divorced, children legally belonged to the father (or a male relative if he was no longer living).

Romans believed in many gods, including the sky god Jupiter; Mars, a god who protected Romans in war; and Vesta, the goddess of the home. People would worship these gods and goddesses both at public temples and in their homes.

Why ancient Rome still matters

Today, the city of Rome is the capital of Italy, with around three million people. Visitors can still see many ancient Roman ruins, from the Colosseum to the Roman Forum, where much of ancient Roman politics took place.

But beyond the crumbling buildings, Rome’s impact is seen all over the world today, from huge sports stadiums inspired by the Colosseum to the way that we vote for politicians. The republic’s system of checks and balances on power even inspired the founders of the United States government.

If you drive in Europe or the Middle East today, you might be on a route created by the ancient Romans. Those engineers built a system of 50,000 miles of roads that connected the empire, allowing troops to easily conquer new land and traders to travel and bring back wealth. (It’s where we get the saying, “All roads lead to Rome.”)

You can also thank Roman engineers for perfecting a system for getting running water. They built aqueducts, which were long channels that delivered fresh water from up to 57 miles away for people’s baths, fountains, and even toilets. (Some ancient aqueducts still provide water to modern-day Rome!)

Julius Caesar even gave the world its 365-day calendar with an extra day every fourth year, or leap year. The month of July is named after him, and August is named after his successor, Augustus.

- The planets Mercury , Venus, Mars , Jupiter , and Saturn are named after Roman gods.

- Roman gods inspired the names of two Western months: January (Janus) and March (Mars).

- Romans spoke Latin, the language that modern French, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Romanian are based on.

- Ancient Romans used animal and human urine to clean their clothes.

- A hill in modern-day Rome called Monte Testaccio is an ancient garbage dump made up of smashed pots and jars.

- Romans sometimes filled the Colosseum with water and held naval battles inside.

Read This Next

The lost city of pompeii, the first olympics.

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your California Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell My Info

- National Geographic

- National Geographic Education

- Shop Nat Geo

- Customer Service

- Manage Your Subscription

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Search on OralHistory.ws Blog

Navigating the Historical Labyrinth of Ancient Rome: Essay Topics

Welcome, intrepid time travelers and history enthusiasts! As we stand on the brink of another academic exploration, the historical labyrinth of Ancient Rome beckons us. Famous for its grandeur, societal advancements, and dramatic political turmoil, Rome offers a goldmine of captivating topics for your next argumentative essay. To help you on this journey, we present a robust selection of 99 exciting essay topics that span various aspects of Roman civilization.

Table of content

Peeling Back the Layers: Rome Uncovered

What makes Rome so special that it commands our attention more than two millennia after its founding? The city is a fascinating embodiment of countless narratives, where every stone and monument whispers tales of yesteryears.

The story of Rome is one of power and decline, glory and catastrophe. A city that rose from a humble settlement on the banks of the Tiber River to rule a vast empire stretching across three continents. It is an epic tale filled with influential leaders, grand political schemes, momentous battles, and artistic innovations that continue to shape our world.

A plunge into Roman history is akin to unraveling a complex web of interactions, directly and indirectly, affecting societies today. Their architectural innovations, from aqueducts to roads, set a precedent for urban infrastructure. The Roman legal system became a foundation for numerous global legal practices. Concepts of citizenship and governance, notions of entertainment, and even parts of our language owe much to Rome.

Moreover, Rome represents a pivotal point in religious history, being central to the spread of Christianity. The development and dissemination of Christian thought within the Roman Empire and the eventual adoption of Christianity as the state religion had enduring consequences on global religious landscapes.

In a broader sense, understanding Rome means understanding the roots of Western civilization. The rise and fall of this once-majestic Empire provide a window into our collective past, offering insights into humanity’s capacity for creativity, resilience, ambition, and even self-destruction.

Rome offers an abundant, complex, and fascinating field of study, a treasure trove of knowledge waiting to be discovered and appreciated. Unearthing the secrets of Rome is a journey, an intellectual adventure that promises to be as enriching as it is exciting. So, are you ready to join us as we traverse the annals of Roman history, picking up the echoes of the past to comprehend our present better?

Topics Galore: Categories for Your Consideration

To aid your exploration, we’ve organized these essay topics into five broad categories: Society and Culture, Politics and Leaders, Warfare and Conquests, Religion and Mythology, and Architecture and Innovations.

The Mosaic of Society and Culture

Step into the everyday life of a Roman citizen, explore their social norms and examine the pivotal Role of culture in shaping the Roman Empire.

Topic Examples:

- The Class Structure of Roman Society: Patricians and Plebeians

- The Evolution of Roman Law and Its Impact on Modern Legal Systems

- The Role of Women in Roman Society

- Slavery in Rome: A Comparative Analysis with Ancient Greece

- The Significance of Roman Festivals and Public Spectacles

- Gladiatorial Games: a Societal Necessity or Brutal Entertainment?

- The Impact of Roman Colonization on Indigenous Cultures

- The Role of Patronage in the Roman Arts

- Language Diversity in the Roman Empire: a Study of Vernacular Languages

- Roman Festivals: an Exploration of Seasonal Celebrations and Their Societal Implications

- The Roman Culinary Arts: From the Simple to the Extravagant

- The Influence of Greek Culture on Roman Society

- The Impact of Rome on Modern Western Civilization

- The Societal Impact of Roman Clothing and Fashion

- An Analysis of the Roman Education System

- Roman Theater: a Societal Mirror or Mere Entertainment?

- The Role of Sports and Recreation in Roman Society

- Roman Marriage Customs and Their Influence on Societal Structure

- Influence of Latin: from Roman Streets to Modern Linguistics

- Roman Literature and Its Reflection on Society

- Graffiti in Pompeii: a Snapshot of Roman Culture

- The Significance of Patron-Client Relationships in Roman Society

- The Societal Role of the Roman Baths

- Roman Dining Customs: a Look at the Convivium

- Examination of Roman Social Clubs and Associations

- Roman Funeral Rituals and Beliefs About Death

- Childhood in Rome: From birth to Adulthood

- Roman Slavery: a Study of Manumission and Freedmen

- The Impact of Greek Philosophy on Roman Society

- Urban Versus Rural Life in Roman Society

- The Contribution of Rome to Modern Theatre

- The Influence of Rome on Western Literature

- The Effect of Roman Tax Policies on Its Citizens

- Examination of Roman Housing and City Planning

- Trade and Commerce in the Roman Empire

- An Overview of Roman Education: From Wax Tablets to Schools

- Influence of Roman Laws on Today’s Legal Systems

- The Cultural Significance of Roman Mosaics and Frescoes

- An In-Depth Look at Roman Entertainment

- Roman Citizenship: Privileges and Responsibilities

- The Role of Public Speaking and Rhetoric in Roman Society

- Influence of Roman Numerals on Modern Numbering Systems

- Roman Jewelry: More than Mere Decoration

- The Life of a Roman Soldier: Expectations and Reality

- The Societal Implications of Roman Expansion

- The Significance of Roman Trade Routes

- The Role of Women in Different Sectors of Roman Society

- The Societal Influence of the Pax Romana

- The Importance of the Family Unit in Roman Society

- An Analysis of Roman Coinage and Its Symbolism

- The Societal Impact of the Roman Calendar

- Roman Music: Its Characteristics and Influence on Modern Music

The Grand Stage of Politics and Leaders

Dive into the tumultuous political arena of Rome and discover the individuals whose leadership shaped the Empire’s destiny.

- Julius Caesar: Revolutionary Leader or Tyrant?

- The Political Implications of Caesar’s Assassination

- The Influence and Impact of the Twelve Tables

- The Transition From the Roman Republic to the Roman Empire

- A Critique of Emperor Nero’s Reign

- The Political Structure of the Roman Empire: a Detailed Study

- The Role of the Roman Senate in the Governance of the Empire

- Analysis of Augustus’ Policies and Their Impact on Rome

- The Rise and Fall of Julius Caesar: a Critical Analysis

- The Political Genius of Emperor Augustus

- The Significance of the Roman Consuls

- An Analysis of the Political Reforms of the Gracchi Brothers

- A Critique of the Rule of Emperor Marcus Aurelius

- An Examination of the Roman Legal System

- The Legacy of Roman Law on Contemporary Legal Practices

- The Reign of Emperor Hadrian: Rome’s Grand Builder

- The Roman Republic vs. the Roman Empire: a Comparison

- The Political Impact of Rome’s Geographic Location

- The Role of the Praetorian Guard in Roman Politics

- Examination of Political Propaganda in Ancient Rome

- The Political Implications of Roman Citizenship

- Influence and Power: the Political Role of Roman Women

- The Effect of Roman Colonization on the Provinces

- Examination of the Political Climate During the Pax Romana

- The Political Strategy behind Roman Road Construction

- The Rule of Emperor Constantine and the Christian Shift

- An Analysis of the Reign of Emperor Diocletian

- Influence of Roman Political Ideologies on Western Political Thought

- Examination of Roman Provincial Administration

- The Influence of Roman Bureaucracy on Modern Administrative Systems

- The Role and Power of the Roman Assemblies

- Impact of the Roman Legal Code on International Law

- Political Conflicts and Their Impact on Rome’s Fall

- An Overview of the Roman Tax System

- The Rule of Emperor Trajan: Rome at Its Zenith

- Role of Foreign Policy in Rome’s Expansion

- The Societal Impact of the ‘Bread and Circuses’ Policy

- The Transition of Power: from Republic to Imperial Rule

- Examination of Treason Laws in the Roman Empire

- The Influence of Stoicism on Roman Leaders

- The Political Significance of the Roman Forum

- The Use and Misuse of Political Power in Rome

- The Influence of Roman Political Architecture

- An Examination of Roman Diplomacy

- The Influence of Emperor Justinian on Roman Law

- Roman Economy: a Source of Political Power?

- The Political Implications of the Roman Census

- The Impact of Corruption on the Decline of the Roman Empire

- Analysis of the Social Mobility in Roman Political Structures

- Examination of the Power Dynamics within the Roman Imperial Family

- The Impact of the “Princeps” Title on the Image of Roman Leadership

- The Role of Tribunes in the Roman Political Landscape

Epic Battles: Warfare and Conquests

Explore Rome’s military might, strategic brilliance, and the monumental conquests that expanded its boundaries.

- The Significance of the Punic Wars in Rome’s Rise to Power

- Roman Military Tactics: a Study of the Roman Legion

- The Impact of Rome’s Military Conquests on Its Economy and Culture

- The Reasons Behind the Fall of the Roman Empire

- The Role of the Roman Navy in the Expansion of the Empire

- A Comparative Study of Roman and Greek Military Strategies

- Analysis of the Barbarian Invasions and Their Effect on Rome

- The Causes and Effects of the Roman Civil War

- Rome vs. Carthage: a Comparative Study of Military Might

- The Military Strategies of Julius Caesar

- An Analysis of the Roman Siege Warfare

- The Military Significance of the Battle of Actium

- The Influence of Roman Military Tactics on Modern Warfare

- Examination of the Roman Siege of Jerusalem

- The Role of the Roman Navy During the Punic Wars

- The Influence of Roman Military Gear and Equipment

- Analysis of the Roman Military Training and Discipline

- Roman Logistics: a Key to Military Success

- The Societal Implications of Rome’s Military Victories

- The Role of the Military in Roman Politics

- The Impact of Rome’s Military Culture on Its Society

- The Roman Army: an Instrument of Imperialism

- The Effect of the Roman Military on Conquered Societies

- The Influence of Roman Fortifications on Modern Military Architecture

- A Study of the Roman Auxiliary Troops

- Analysis of the Roman Military Hierarchy

- The Significance of Roman Military Law

- The Role of Military Engineering in Roman Conquests

- The Strategic Importance of Roman Camps

- A Detailed Study of the Roman Cavalry

- Examination of the Roman Defenses along the Rhine and Danube

- An Analysis of the Roman Supply Lines and Logistics

- The Societal Impact of the Roman Military-Industrial Complex

- The Psychological Warfare Employed by the Romans

- A Study of Roman Battlefield Medicine

- The Role of Intelligence and Espionage in Roman Military Strategy

- The Influence of Roman Military Formations

- The Significance of Roman Veterans in Society

- A Study of the Roman Military Standard

- An Analysis of the Role of Mercenaries in the Roman Army

- The Military Innovations of the Romans

- The Impact of Rome’s War Economy on Society

- A Detailed Study of the Roman Military Roads

- The Influence of Roman Naval Warfare

- A Study of the Roman War Chariots

- An Analysis of the Military Decorations and Honors in Rome

- The Impact of Military Defeats on Rome’s Societal and Political Landscape

- The Influence of Military Infrastructure on the Expansion of the Roman Empire

- The Role of Strategic Fortifications in the Defense of the Roman Empire

- Roman Imperialism: A Study of the Motivations Behind Rome’s Territorial Expansions

- An Examination of Roman War Elephants

- The Impact of the Roman Military on the Spread of the Latin Language

Religion and Mythology: Unraveling the Intricacies of Divine Rome

Unravel the complexities of Roman religious beliefs and mythology and their influence on Roman society.

- The Role of Religion in Roman society

- The Influence of Greek Mythology on Roman Religious Beliefs

- The Cult of the Emperor: Its Inception and Impact

- The Role of Augurs and Oracles in Roman Society

- The Introduction and Spread of Christianity in Rome

- Analysis of Roman Gods and Their Societal Significance

- Mithraism in the Roman Empire: a Detailed Study

- The Impact of Roman Mythology on Roman Societal Norms

- The Significance of Sacrificial Rituals in Roman Religion

- Comparative Study of Roman and Greek Gods

- The Societal Role of Roman Priesthoods

- An Analysis of the Roman State Religion

- The Influence of Roman Religious Festivals on the Societal Structure

- The Role of Religion in Roman Military Campaigns

- An Examination of the Roman Funeral Rites

- The Impact of the Roman Belief in Omens and Divination

- The Societal and Political Implications of the Vestal Virgins

- The Role of Astrology in Roman Religion

- An Analysis of the Eastern Religions in Rome

- The Significance of Roman Temples in Society

- The Evolution of the Roman Pantheon

- The Transition from Roman Polytheism to Christian Monotheism

- The Impact of Roman Religious Tolerance

- Examination of the Religious Symbolism in Roman Art

- The Influence of Roman Religion on Roman Law

- A Detailed Study of Roman Religious Festivals

- The Effect of Christianity on Roman Society and Culture

- A Study of the Persecution of Christians in Rome

- An Examination of the Religious Implications of the Roman Imperial Cult

- The Relationship between Roman Religion and Philosophy

- The Cultural Implications of Roman Burial Practices

- The Role of Mythology in Roman Literature

- The Impact of Roman Religious Architecture

- The Role of Roman Religion in Public Life

- The Influence of Roman Mythology on Western Culture

- Examination of the Roman Religious Calendar

- The Role of Religious Syncretism in Rome

- The Societal Implications of Roman Oracles and Prophecies

- The Significance of Roman Mystery Cults

- An Analysis of the Religious Landscape of Rome

- The Impact of the Roman Catacombs on the Christian Religion

- A Study of the Religious Rites and Rituals in Roman Society

- The Role of Roman Religion in the Preservation of Rome’s Heritage

- An Examination of the Roman Beliefs about the Afterlife

- The Influence of Roman Religion on Roman Music and Theater

- A Detailed Study of the Capitoline Triad

- The Societal Implications of Roman Religious Sculptures and Carvings

- The Impact of Roman Religious Beliefs on Medical Practices

- Examination of Syncretism in Roman Religious Practices

- Influence of Roman Religious and Mythological Narratives on European Literature

- Roman Death Rituals: a Study of Belief in the Afterlife

- The Societal and Political Impact of the Cult of Isis in Rome

Architecture and Innovations: Standing on the Shoulders of Roman Giants

Delve into the architectural marvels of Rome and discover the innovations that advanced Roman society.

- The Architectural Grandeur of the Colosseum: an In-Depth Analysis

- The Significance of Roman Roads and Their Influence on Modern Infrastructure

- The Invention of Concrete and Its Impact on Roman Architecture

- The Design and Purpose of Roman Aqueducts

- A Comparative Study of Roman and Greek Architecture

- The Engineering Marvel of the Roman Sewage System: the Cloaca Maxima

- The Cultural Significance of Roman Baths

- The Architectural Significance of the Roman Arch

- The Role of the Roman Pantheon in Architectural History

- An Analysis of the Roman Domus: From Layout to Lifestyle

- The Influence of Roman Architecture on the Renaissance Period

- An Examination of Roman City Planning

- The Architectural and Cultural Significance of the Roman Basilicas

- The Societal Implications of the Roman Insulae

- A Study of the Construction Techniques of Roman Bridges

- The Innovation and Importance of the Roman Hypocaust System

- An Analysis of the Use of the Arch in Roman Architecture

- The Architectural Marvel of the Roman Thermae

- The Influence of Roman Architecture on Modern Stadium Design

- The Evolution of Roman Wall Painting Styles

- The Architectural Significance of the Roman Villa

- An Examination of the Engineering of the Roman Aqueducts

- The Societal Implications of Roman Road Construction

- A Study of the Roman Forum and Its Buildings

- An Analysis of the Principles of Roman Urban Planning

- The Influence of Roman Architecture on Western Civilization

- The Impact of Roman construction materials and Techniques

- The Use and Symbolism of Roman Sculpture in Public Spaces

- The Aesthetic and Functional Aspects of Roman Gardens

- The Architectural and Societal Importance of Roman Theatres

- The Influence of Roman Military Architecture on Modern Fortifications

- The Significance of the Appian Way

- An Analysis of the Roman Use of the Dome

- The Roman Use of Concrete and Its Influence on Modern Architecture

- The Societal Role of the Roman Circus

- An Examination of the Architectural Innovations in the Colosseum

- A Study of the Architectural Layout of a Roman Military Camp

- An Examination of the Impact of Roman Architecture on Religious Structures

- The Design and Functionality of the Roman Sewer System

- An Analysis of the Roman Use of Column Orders

- The Societal Implications of Roman Public Squares

- The Architectural Legacy of Emperor Hadrian

- A Study of the Architecture and Design of Roman Ports

- An Examination of Roman Lighthouses and Their Architectural Importance

- The Architectural and Societal Impact of Roman Catacombs

- The Influence of Roman Architecture on European Cathedrals

- An Analysis of the Architectural and Artistic Features of Roman Triumphal Arches

- Roman Engineering: a Study of the Design and Construction of Roman Harbors

- The Societal Implications of Roman Apartment Buildings (Insulae)

- Roman City Defenses: a Study of Walls and Fortifications

- The Architectural Significance of the Roman Triumphal Columns

- Roman Villas: a Study of Country Houses and Their Impact on Roman Society

As you embark on this journey through time, remember that the goal of an argumentative essay is to present a balanced view substantiated by solid research and evidence. Choose a topic that excites you, gather your evidence, and embark on an intellectual adventure into the heart of Ancient Rome.

Let the spirit of Rome guide your pen! Happy writing, history explorers!

📎 Related Articles

1. Exploring Riveting World History Before 1500 Paper Topics 2. Navigating Through the Labyrinth of Ancient History Topics 3. Intriguing Modern History Topics for Engaging Research 4. Stirring the Pot: Controversial Topics in History for Research Paper 5. Navigating Historical Debates: History Argumentative Essay Topics

City of Rome overview—origins to the archaic period

Temple of Vesta, The Roman Forum (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The Eternal City

Rome is often described as the “eternal city,” conveying the idea that it lives (and has lived) forever, perhaps even suggesting a sort of unchanging immortality. However, even those things that are iconically eternal have a beginning. The humble beginnings of Rome provide the roots of a long cultural story, one that we continue to experience, sample, and live via archaeology, history, and cultural reception.

Romulus—Rome’s legendary founder—is said to have been suckled by a she-wolf, to have slain his own brother, and to have instituted the bellicose, strong, and independent character of the populus Romanus (“the Roman people”). The history and archaeology of the city that Romulus is credited with founding are inextricably wrapped up in layers of myth and folklore that helped Romans to tell their own story and generate collective memories in the urban space. For many archaeologists, these legends that describe the foundation of the city of Rome are fantastical and represent an attempt to explain not only how the city came to be founded, but also to establish ties between the city center and the surrounding areas of central Italy. The perspective offered by archaeological evidence allows us to examine the earliest phases of the city and the settlements that would have been founded there and to see the places in which myth and reality intersect. The legends and folklore also need testing, especially since blind acceptance of them has reinforced stereotypes about the city of Rome and its people that may not be representative of reality.

Model of Rome in the Archaic period with a view of the Capitol and the Forum (Musée de la Civilisation Romaine, Rome)

Legends aside, Rome’s earliest beginnings are humble and relatively ordinary. Settlements of smaller size that often occupy naturally defensible hilltops characterize the Iron Age in central Italy. Legends aside, Rome’s earliest beginnings are humble and relatively ordinary.

The Iron Age in central Italy is characterized by small settlements that often occupy naturally defensible hilltops. By the eighth century B.C.E., changes in settlement types became evident. These changes involve a reallocation of space and a movement toward nucleation—that is the clustering of population in a more densely populated center as opposed to a lower density scattering of small settlements across the landscape. In the immediate neighborhood of Rome, this is first evident in Latin settlements (for instance, near Gabii to the east of Rome), as well as in Etruscan settlements in south Etruria, for example Veii and Tarquinii.

Map showing Latin settlements in central Italy (and, toward the north, Etruscan sites in Southern Etruria) (map, Cassius Ahenobarbus , CC BY-SA 3.0)

It is as a result of this phenomenon that the historical Rome comes into being. Today archaeologists often refer to “early Rome” as a way to describe the early phases of the city that correspond to the Iron Age. The legendary actions of Romulus were believed to have taken place in the year 753 B.C.E. As a result of Romulus’ actions, the Palatine Hill was thought to have been surrounded by a fortification wall. Archaeological investigation of the Palatine Hill itself has revealed important clues about the earliest days of the city of Rome, including traces of an early wall surrounding at least some part of the Palatine Hill. This wall may be referred to as the “wall of Romulus” or murus Romuli (and should not be confused with the later “Servian wall”).[1]

A model of the Iron Age village on the Palatine Hill (photo: Kathryn Arnold , CC BY-SA 4.0)

“The Palatine City” and the “Hut of Romulus”

The agglomeration of Iron Age huts on the Palatine Hill is representative of the type of settlement commonly found in central Tyrrhenian Italy during the early Iron Age—relatively small in size and taking advantage of naturally defensible positions. The typical Iron Age hut in central Italy is a one-room structure with an oval ground plan. Its roof is of thatching that is supported by a wooden roof tree while its walls are generally made from a technique called wattle-and-daub which is essentially mud plaster applied over a framework of organic material. These huts served multiple functions, including processing and storage. In addition to the examples known from the site of Rome, we can see evidence for similar building types among the Etruscans and the Latins. Some assistance in reconstructing the appearance of these huts is offered by contemporary cinerary urns that take the shape of a hut, earning them the moniker “hut urns”. These urns may represent the economic status of the deceased person.

Hut Urn, 8th century B.C.E., Etruscan, ceramics, 22 x 23 x 28 cm ( The Walters Art Museum )

The Great Drain and the emergence of the Forum Romanum

The valley that is framed by the Palatine, Esquiline, and Capitoline hills (what we today call the Forum Romanum— the Roman Forum ) was originally not a settlement area, but rather a space that lay outside of settlement limits.

Rome in 753 B.C.E. (map, Cristiano64 , CC BY-SA 3.0)

The usability of this valley was compromised by the fact that periodic, seasonal flooding of the Tiber river, coupled with natural surface water, could render the valley wet and marshy. Since this area lay outside of settlement limits, it came to be used for both inhumation and cremation burials as was customary in the Iron Age. As Rome was beginning to coalesce, however, this space came to be of interest to the nascent city and its use was re-tasked. This meant that both human behavior and natural events had to be checked. For the former, human burials in the valley needed to cease, with burial activity being transferred to another location on the far side of the Esquiline Hill. Curbing nature was a larger challenge and it involved an impressive example of the early state organizing labor and resources to raise the surface level of the Forum valley through an artificial landfill project. This project involved the manual gathering and dumping of soil in the forum valley in order to raise the surface level by several meters. This would have required upwards of over 35,000 cubic feet of landfill to accomplish.

In connection with the landfill project was the creation of a channelized drain dubbed the Cloaca Maxima (“great drain”) that drained water away from the valley, through the area of the Velabrum, to the Tiber river. While initially an open drain, the Cloaca Maxima was eventually covered by vaulted masonry.

The poliadic temple—Jupiter Best and Greatest

The chief deity of the Roman people is the sky god Jupiter whose cult is connected in the legendary history with the earliest days of Rome. By the later sixth century B.C.E. a massive building project organized by the last of Rome’s Archaic kings was taking shape, namely creating a chief civic temple dedicated to IUPPITER OPTIMUS MAXIMUS or “Jupiter Best and Greatest.” Perched atop the Capitoline Hill, the temple of Jupiter would remain the focus of the Roman state religion for a millennium to come. Sacro-civic architecture of this type draws on central Italian architectural models and, in terms of urban life, provides a focused location for key events of the state’s ritual activity.

Left: reconstruction (in plexiglass) of the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus revealing the foundations below, which can be seen today in the Capitoline Museum (right).

The river harbor and the “Cattle market”

Another important area of activity in the early city is the area surrounding the river harbor on the Tiber River, a space usually referred to as the Forum Boarium (“Cattle market”). The harbor provided a place where river-borne craft could put-in to shore in order to engage in commerce. Archaeological evidence suggests that this area is early on a focus of regional economic interchange and it takes advantage of a key point on the Tiber river, given that this is one of the only natural fords or crossing points in the lower extent of the river.

Reconstruction of the imperial Rome (4th century C.E.), by Italo Gismondi (photo: Sebastià Giralt , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The twin temples in the archaeological site today known as the “ Sacred Area of Sant’Omobono ” is connected with the commercial function of this zone. Its roofline decorations included a terracotta statue of Herakles who was connected legendarily to the area of the Forum Boarium and also served as patron of travelers and traders. Dedications at the twin temples of Fortuna and Mater Matuta reflect the nature of this area as a place of commerce and interchange. Like the Capitoline temple of Jupiter, these temples draw on central Italic traditions in terms of their architecture.

The foundations of the city and its growth in the Archaic period set the stage for its next phase. Tradition holds that Rome expelled her Archaic kings in 509 B.C.E., ushering in a period when a reshuffling of governmental structures would create a republican system. This new system of government also brought with it implications for the development of the city of Rome and the role played by art and architecture.

1. See T.P. Wiseman, “Review: Reading Carandini,” The Journal of Roman Studies 91 (2001) pp. 182-193; Roberto Suro, “Newly Found Wall May Give Clue To Origin of Rome, Scientist Says: When Did Rome Become Rome? Wall May Give Clue,” The New York Times (10 June 1988), p. A1; Henry R. Hurst, “The ‘Murus Romuli’ at the Northern Corner of the Palatine and the Porta Romanula : a Progress Report,” in Res Bene Gestae: ricerche di storia urbana su Roma antica in onore di Eva Margareta Steinby , edited by Anna Leone et al, pp. 79-102 (Rome: Edizioni Quasar, 2007); Andrea Carandini et al. The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City 2 volumes (Princeton University Press, 2017). Table 62.

Additional Resources

Capitoline Museums – via Google Arts and Culture

Digitales Forum Romanum

Albert J. Ammerman, “On the Origins of the Forum Romanum,” American Journal of Archaeology , vol. 94, no. 4, 1990, pp. 627-645. http://www.jstor.org/stable/505123

Andrea Carandini et al. The Atlas of Ancient Rome: Biography and Portraits of the City 2 v. (Princeton University Press, 2017).

The Atlas of Ancient Rome

Isabella Damiani, Claudio Parisi Presicce (eds.), La Roma dei Re: Il racconto dell’archeologia (Gangemi Editore, 2019).

Alexandre Grandazzi, The Foundation of Rome: Myth and History, trans. Jane Marie Todd (Cornell University Press, 1997).

John N. Hopkins, The Genesis of Roman Architecture (New Haven: Yales University Press, 2016).

C. J. Smith, Early Rome and Latium: Economy and Society c. 1000 to 500 BC. (Oxford University Press, 1996).

N. Terrenato, Brocato, P., Caruso, G., Ramieri, A.M., Becker, H.W., Cangemi, I., Mantiloni, G. and Regoli, C. “The S. Omobono Sanctuary in Rome: Assessing eighty years of fieldwork and exploring perspectives for the future,” Internet Archaeology 31 (2012).

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Visiting Sleeping Beauties: Reawakening Fashion?

You must join the virtual exhibition queue when you arrive. If capacity has been reached for the day, the queue will close early.

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Essays

The roman republic.

Limestone funerary relief

Torso of a Ptolemaic King, inscribed with cartouches of a late Ptolemy

Marble bust of a man

Marble statue of a draped seated man

Signed by Zeuxis as sculptor

Tableware from the Tivoli Hoard

Sword and Scabbard

Cubiculum (bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale

Department of Greek and Roman Art , The Metropolitan Museum of Art

October 2000

From its inauspicious beginnings as a small cluster of huts in the tenth century B.C., Rome developed into a city-state, first ruled by kings, then, from 509 B.C. onward, by a new form of government—the Republic. During the early Republic, power rested in the hands of the patricians, a privileged class of Roman citizens whose status was a birthright. The patricians had exclusive control over all religious offices and issued final assent ( patrum auctoritas ) to decisions made by the Roman popular assemblies. However, debts and an unfair distribution of public land prompted the poorer Roman citizens, known as the plebians, to withdraw from the city-state and form their own assembly, elect their own officers, and set up their own cults . Their principal demands were debt relief and a more equitable distribution of newly conquered territory in allotments to Roman citizens. Eventually, in 287 B.C., with the so-called Conflict of the Orders, wealthier, land-rich plebians achieved political equality with the patricians. The main political result was the birth of a noble ruling class consisting of both patricians and plebians, a unique power-sharing partnership that continued into the late first century B.C.

During the last three centuries of the Republic, Rome became a metropolis and the capital city of a vast expanse of territory acquired piecemeal through conquest and diplomacy. Administered territories ( provinciae ) outside Italy included: Sicily, Sardinia, Spain, Africa, Macedon, Achaea, Asia, Cilicia, Gaul, Cyrene, Bithynia, Crete, Pontus, Syria, and Cyprus. The strains of governing an ever-expanding empire involving a major military commitment, and the widening gulf between those citizens who profited from Rome’s new wealth and those who were impoverished, generated social breakdown, political turmoil, and the eventual collapse of the Republic. Rome experienced a long and bloody series of civil wars, political crises, and civil disturbances that culminated with the dictatorship of Julius Caesar and his assassination on March 15, 44 B.C. After Caesar’s death, the task of reforming the Roman state and restoring peace and stability fell to his grandnephew, Gaius Julius Caesar Octavianus, only eighteen years old, who purged all opposition to his complete control of the Roman empire and was granted the honorific title of Augustus in 27 B.C.

Department of Greek and Roman Art. “The Roman Republic.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/romr/hd_romr.htm (October 2000)

Further Reading

Gruen, Erich S. Culture and National Identity in Republican Rome . Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1992.

Kleiner, Diana E. E. Roman Sculpture . New Haven: Yale University Press, 1992.

Matyszak, Philip. Chronicle of the Roman Republic: The Rulers of Ancient Rome from Romulus to Augustus . London: Thames & Hudson, 2003.

Milleker, Elizabeth J., ed. The Year One: Art of the Ancient World East and West . Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000. See on MetPublications

Additional Essays by Department of Greek and Roman Art

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Classical Cyprus (ca. 480–ca. 310 B.C.) .” (July 2007)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Antonine Dynasty (138–193) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Ancient Greek Dress .” (October 2003)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Death, Burial, and the Afterlife in Ancient Greece .” (October 2003)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Geometric Art in Ancient Greece .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Flavian Dynasty (69–96 A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 B.C.–68 A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Augustan Rule (27 B.C.–14 A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Severan Dynasty (193–235 A.D.) .” (October 2000)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Roman Egypt .” (October 2000)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Roman Copies of Greek Statues .” (October 2002)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques .” (October 2002)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Boscoreale: Frescoes from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Early Cycladic Art and Culture .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Geometric and Archaic Cyprus .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Scenes of Everyday Life in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Greek Art in the Archaic Period .” (October 2003)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Symposium in Ancient Greece .” (October 2002)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Roman Painting .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Tanagra Figurines .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Augustan Villa at Boscotrecase .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ The Cesnola Collection at The Metropolitan Museum of Art .” (October 2004)

- Department of Greek and Roman Art. “ Warfare in Ancient Greece .” (October 2000)

Related Essays

- Art of the Hellenistic Age and the Hellenistic Tradition

- Art of the Roman Provinces, 1–500 A.D.

- Augustan Rule (27 B.C.–14 A.D.)

- The Julio-Claudian Dynasty (27 B.C.–68 A.D.)

- The Roman Empire (27 B.C.–393 A.D.)

- Ancient Greek Colonization and Trade and their Influence on Greek Art

- Barbarians and Romans

- Boscoreale: Frescoes from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor

- The Byzantine City of Amorium

- Contexts for the Display of Statues in Classical Antiquity

- Eastern Religions in the Roman World

- Egypt in the Ptolemaic Period

- Hellenistic and Roman Cyprus

- Hellenistic Jewelry

- Intellectual Pursuits of the Hellenistic Age

- Mystery Cults in the Greek and Roman World

- The Nude in Western Art and Its Beginnings in Antiquity

- Retrospective Styles in Greek and Roman Sculpture

- The Rise of Macedon and the Conquests of Alexander the Great

- Roman Glass

- Roman Housing

- Roman Inscriptions

- Roman Painting

- Roman Portrait Sculpture: Republican through Constantinian

- Roman Portrait Sculpture: The Stylistic Cycle

- Anatolia and the Caucasus (Asia Minor), 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Ancient Greece, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Italian Peninsula, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Western and Central Europe, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- Western North Africa, 1000 B.C.–1 A.D.

- The Roman Republic (ca. 44 B.C.)

- Ancient Egyptian Art

- Ancient Roman Art

- Archaeology

- Architecture

- Augustan Period

- Balkan Peninsula

- Funerary Art

- Musical Instrument

- Period Room

- Ptolemaic Period in Egypt

- Roman Republican Period

- Sculpture in the Round

- String Instrument

- Wall Painting

- Western North Africa (The Maghrib)

Artist or Maker

Online features.

- The Artist Project: “Diana Al-Hadid on the cubiculum from the villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale”

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

World history

Course: world history > unit 2.

- Rise of Julius Caesar

- Caesar, Cleopatra and the Ides of March

- Ides of March spark a civil war

- Augustus and the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire

- Roman empire

- State building: Roman empire

- Ancient Rome

- The Roman Empire began in 27 BCE when Augustus became the sole ruler of Rome.

- Augustus and his successors tried to maintain the imagery and language of the Roman Republic to justify and preserve their personal power.

- Beginning with Augustus, emperors built far more monumental structures, which transformed the city of Rome.

Augustus and the empire

Imperial institutions, infrastructure, monumental building, foreign policy, want to join the conversation.

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

INFOGRAPHIC

How rome inspires us today.

Use this infographic to explore how the society and government of ancient Rome has influenced our modern world.

Anthropology, Archaeology, Social Studies, World History

Loading ...

Idea for Use in the Classroom

Elements of ancient Rome exist in our daily lives and are visible throughout our modern infrastructure, government, and culture. Similar to our modern world, the Romans held cultural events, built and stocked libraries, and provided health care. People gathered in town centers to read news on stone tablets and the children attended school. The government passed laws that protected its citizens. Have students develop a KWL chart to find out what they know about ancient Rome, what they want to learn, and what they find out. Split the class into three groups and invite each group to research life in ancient Rome . Once the groups have finished their research, facilitate a class discussion on their findings. Complete and review the KWL chart with the class. Then, as a whole class, review the infographic. Review with students the connections between ancient Rome and modern life that the infographic displays. Ask students to think of one to two additional examples of traces of ancient Rome that they can see in their community. Then, ask students to write a short essay that addresses the following questions:

- Why have ancient Rome’s influences lasted to inspire modern societies?

- Where have modern societies improved on Rome’s ancient designs, or are there still areas for improvement?

- How do students believe these influences will be affected in the future, especially in the context of the digital revolution occurring worldwide?

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

January 22, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Home — Essay Samples — History — Roman Empire — Ancient Rome

Essays on Ancient Rome

Choosing ancient rome essay topics.

When it comes to writing an essay about Ancient Rome, there are countless topics to explore. The history and culture of this ancient civilization are rich and fascinating, offering a wealth of material for research and analysis. However, choosing the right topic can be a daunting task. In this guide, we will discuss the importance of selecting a compelling topic, offer advice on how to choose the right one, and provide a detailed list of recommended essay topics to inspire your writing.

The Importance of Choosing the Right Topic

Choosing the right topic is crucial for a successful essay about Ancient Rome. The topic you choose will determine the direction and focus of your research, as well as the depth and breadth of your analysis. A compelling topic will not only capture the interest of your readers but also provide you with the opportunity to delve into a specific aspect of Ancient Rome that intrigues you. Additionally, a well-chosen topic will ensure that you have access to a wide range of sources and materials to support your arguments and findings.

Advice on Choosing a Topic

When choosing an Ancient Rome essay topic, it's important to consider your interests, as well as the requirements of the assignment. Think about what aspect of Ancient Rome you are most passionate about and what specific questions or issues you would like to explore. Consider the scope of the assignment and the amount of time and resources you have available for research. It's also helpful to brainstorm potential topics and conduct some preliminary research to gauge the availability of source material.

Recommended Essay Topics

Politics and government.

- The rise and fall of the Roman Republic

- The impact of Julius Caesar on Roman politics

- The role of the Roman Senate in governing the empire

- The reforms of Emperor Augustus

Social and Cultural Life

- The role of women in Ancient Rome

- Entertainment and leisure activities in Roman society

- The importance of religion in the lives of Romans

- The impact of slavery on the Roman economy and society

Military and Warfare

- The conquest of Gaul by Julius Caesar

- The strategies and tactics of the Roman army

- The impact of military expansion on Roman society

- The decline and fall of the Roman military

Art and Architecture

- The legacy of Roman architecture in modern society

- The influence of Greek art on Roman culture

- The significance of Roman sculpture and mosaics

- The construction and engineering of Roman aqueducts

Economy and Trade

- The development of trade routes in the Roman Empire

- The impact of slavery on the Roman economy

- The role of agriculture in sustaining the Roman Empire

- The decline of the Roman economy

These are just a few examples of the many fascinating topics you could explore in an essay about Ancient Rome. Whether you're interested in politics, culture, military history, or economics, there is a wealth of material to inspire your writing. By choosing a compelling and well-researched topic, you can ensure that your essay will be informative, engaging, and thought-provoking.

Ultimately, the key to choosing the right topic is to find something that excites and intrigues you. By selecting a topic that you are passionate about, you can immerse yourself in the research and writing process, resulting in a more compelling and insightful essay. So, take the time to explore the many fascinating aspects of Ancient Rome and choose a topic that will allow you to showcase your knowledge and enthusiasm for this incredible civilization.

Ancient Greece and Rome: a Comparative Analysis

Life expectancy in ancient rome, made-to-order essay as fast as you need it.

Each essay is customized to cater to your unique preferences

+ experts online

Upper-class Homes in Ancient Rome

How ancient rome affected the modern world, the great five poets in ancient rome, the fall of the roman empire, let us write you an essay from scratch.

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Comparison of Augustus and Aeneas

A comparison of malcolm x and julius caesar, polytheistic religion of ancient greeks and romans, get a personalized essay in under 3 hours.

Expert-written essays crafted with your exact needs in mind

The Impact of Food on The Historical Events of The Roman Empire

Why was the roman empire so successful, how the roman republic transformed into the roman empire, constantine: the first roman emperor to be christian, medieval europe after the fall of rome, julius caesar: one of the most prominent figures in the history of rome, the gladiator contests in the roman empire, the portrayal of rome and romans in gladiator and ben hur, the roman empire gladiators, ovid and virgil: two perspectives on the same relationship, the theater of marcellus, the plebeian revolt in ancient rome.

The Era of Pax Romana: Defining Peace and Stability in Ancient Rome

This essay about the Pax Romana discusses the period of relative peace and prosperity from 27 BCE to 180 CE in Ancient Rome under Augustus Caesar’s rule. It outlines how Augustus centralized power, maintained peace through military and diplomatic strategies, and fostered economic and cultural flourishing. However, it also notes the era’s authoritarian governance and social inequalities. The essay concludes by reflecting on the complex legacy of the Pax Romana, highlighting both its achievements and the enduring social challenges it presented.

How it works

The era of Pax Romana, translating to “Roman Peace,” spanned from 27 BCE to 180 CE, marking a pivotal period in the history of Ancient Rome. This era began under the leadership of Augustus Caesar following a tumultuous period of civil wars that had destabilized the late Republic. His ascent to power heralded over two centuries of relative peace and stability across the Roman Empire.

The foundation of the Pax Romana was ostensibly the “restoration of the Republic” as proclaimed by Augustus, though he cleverly retained absolute power.

Rather than expanding democratic practices, Augustus focused on the meticulous control over the Senate, the military, and various other institutional mechanisms that steered Roman life. He positioned himself as the protector of Roman traditions, all the while centralizing authority around himself, which effectively brought an end to the frequent wars and political assassinations that had marred Rome’s political scene.

The sustained peace during this period was achieved through a blend of military strength and strategic diplomacy. Augustus fortified the empire’s borders to ward off barbarian threats and pacified rebellious provinces. His military reforms included the creation of a professional army loyal directly to the emperor, a critical change that curtailed the previous pattern of military commanders using their forces for personal power grabs.

Economically, the Pax Romana ushered in a flourishing era. The stability it introduced allowed for the secure transportation of goods across the empire’s extensive road networks, enabling trade and commerce to thrive under a unified currency and the absence of internal trade barriers. This economic prosperity supported a population boom and the urban centers experienced a vibrant cultural and social life.

The cultural renaissance of the Pax Romana saw advancements in literature, architecture, and arts, under the patronage of the emperor. Literary figures such as Virgil, Horace, and Ovid produced works that still resonate within the Western literary tradition. Architectural feats from this period included the Pantheon and the Colosseum, as well as extensive road and aqueduct systems that remain in use in some parts of the world today.

Despite these advancements, the Pax Romana was not devoid of drawbacks. The era’s stability was often underpinned by authoritarian governance. The series of emperors from Augustus through to Marcus Aurelius wielded absolute power, sometimes at the cost of personal freedoms, maintaining peace often by suppressing dissent and managing public life rigorously.

Additionally, the prosperity of the Pax Romana was unevenly distributed. While the elite enjoyed immense wealth and luxury, those at the lower rungs of society often faced harsh living conditions. Slavery persisted as a cornerstone of the economy, and social mobility was notably constrained.

The conclusion of the Pax Romana is generally recognized with the death of Marcus Aurelius in 180 CE, leading to a slow decline into instability. Yet, the legacy of this period remains a significant reference point in history, symbolizing the potential for sustained peace to cultivate a thriving civilization across multiple facets of life, from economic to cultural, albeit accompanied by notable social challenges.

Overall, the Pax Romana represents a period of significant historical complexity, intertwining stringent political control and military efficiency with economic growth and cultural prosperity, all while showcasing the inherent contradictions of an empire capable of achieving remarkable cultural heights alongside stark social inequalities.

Cite this page

The Era of Pax Romana: Defining Peace and Stability in Ancient Rome. (2024, May 12). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/the-era-of-pax-romana-defining-peace-and-stability-in-ancient-rome/

"The Era of Pax Romana: Defining Peace and Stability in Ancient Rome." PapersOwl.com , 12 May 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/the-era-of-pax-romana-defining-peace-and-stability-in-ancient-rome/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). The Era of Pax Romana: Defining Peace and Stability in Ancient Rome . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/the-era-of-pax-romana-defining-peace-and-stability-in-ancient-rome/ [Accessed: 16 May. 2024]