Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare Essay

Ensuring and promoting diversity and equity in healthcare is critical and impactful in today’s world. Following national standards on culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) includes providing a comfortable environment for employees and patients with different backgrounds. The healthcare office should maintain diversity and inclusion across ethnic, racial, gender, religious, sexual, and other dimensions.

In particular, integrating workers from racial and ethnic minorities is essential in overcoming disparities in the workplace and receiving health care (Goode & Landefeld). To do this, both leadership and the workforce must be skilled in maintaining a respectful and inclusive environment. It is also vital that the administrators and leaders of the healthcare organization understand and provide development and growth opportunities for the staff. Their commitment and education are key to creating a comfortable and diversed climate in the clinic setting. Training, communication skills development, and cultural education are essential for running a healthcare office.

A crucial element of CLAS is the provision of free language assistance to both office workers and patients. Their competence and engagement will be of great help to patients and contribute to the positive standing of the office. An essential element is the printing and distribution of resources in different languages about the services of the health office. This makes the company’s principles and conditions clear and accessible for its non-English-speaking staff and visitors. Moreover, all individuals should be informed about their state of health and have the right to explain themselves in the language they understand the best.

Culturally and linguistically appropriate practices and policies should article part of company etiquette. By encouraging inclusiveness and diversity, healthcare providers empower people and give them the opportunity to access the appropriate healthcare, as well as to improve their quality of life.

Goode, C. A. & Landefeld, T. (2018). The Lack of Diversity in Healthcare: Causes, Consequences, and Solutions. Journal of Best Practices in Health Professions Diversity, 11( 2), 73–95.

- Healthcare in Non-English Speaking Patients

- Culturally and Linguistically Competent Nursing Care

- The Library of Babel by Jorge Luis

- Tobacco and COVID-19 Relations

- Potential Publications for Project Presentation

- Influenza Vaccination of Healthcare Workers in Acute-Care Hospitals

- “Mandated Benefits, Good or Bad? At N.Y. Hearing, Reviews Are Mixed”: Article Review

- Comparison of Black Death and COVID-19

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, October 30). Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare. https://ivypanda.com/essays/diversity-and-inclusion-in-healthcare/

"Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare." IvyPanda , 30 Oct. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/diversity-and-inclusion-in-healthcare/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare'. 30 October.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare." October 30, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/diversity-and-inclusion-in-healthcare/.

1. IvyPanda . "Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare." October 30, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/diversity-and-inclusion-in-healthcare/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Diversity and Inclusion in Healthcare." October 30, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/diversity-and-inclusion-in-healthcare/.

Home — Essay Samples — Social Issues — Diversity — Culture And Diversity In Healthcare

Culture and Diversity in Healthcare

- Categories: Cultural Competence Diversity

About this sample

Words: 671 |

Published: Mar 19, 2024

Words: 671 | Page: 1 | 4 min read

Table of contents

The influence of culture, promoting cultural competence, the importance of diversity, challenges and initiatives.

Cite this Essay

Let us write you an essay from scratch

- 450+ experts on 30 subjects ready to help

- Custom essay delivered in as few as 3 hours

Get high-quality help

Prof Ernest (PhD)

Verified writer

- Expert in: Arts & Culture Social Issues

+ 120 experts online

By clicking “Check Writers’ Offers”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy . We’ll occasionally send you promo and account related email

No need to pay just yet!

Related Essays

1 pages / 594 words

1 pages / 475 words

1 pages / 467 words

2 pages / 1131 words

Remember! This is just a sample.

You can get your custom paper by one of our expert writers.

121 writers online

Still can’t find what you need?

Browse our vast selection of original essay samples, each expertly formatted and styled

Related Essays on Diversity

The future can be both exciting and daunting. The constant barrage of questions about what we plan on doing next can be overwhelming, but it is an important aspect of growing up. The question of where we see ourselves in the [...]

Diversity is an essential aspect of human society and encompasses a range of primary and secondary aspects that have shaped the world throughout history. This essay will explore the importance of historical perspectives in [...]

The entertainment industry has long struggled with issues of diversity and inclusion, with marginalized communities often underrepresented or misrepresented in mainstream media. This lack of representation can have a profound [...]

In E Pluribus Unum: A Quilt of a Country Summary, Pulitzer Prize-winning author Anna Quindlen explores the diverse tapestry of American society and the challenges and opportunities it presents. This essay will focus on the [...]

Diversity may seem as only a ‘modern buzzword’ full of nonsense and hierarchy to some, it certainly is not an original concept; theoretically, it predates civilization’s creation. In practice, the evolution of diversity – and, [...]

Education is a dynamic field where educators strive to make a profound impact on children's lives, shaping their futures and fostering inclusive learning environments. Within this context, the concept of diversity in the [...]

Related Topics

By clicking “Send”, you agree to our Terms of service and Privacy statement . We will occasionally send you account related emails.

Where do you want us to send this sample?

By clicking “Continue”, you agree to our terms of service and privacy policy.

Be careful. This essay is not unique

This essay was donated by a student and is likely to have been used and submitted before

Download this Sample

Free samples may contain mistakes and not unique parts

Sorry, we could not paraphrase this essay. Our professional writers can rewrite it and get you a unique paper.

Please check your inbox.

We can write you a custom essay that will follow your exact instructions and meet the deadlines. Let's fix your grades together!

Get Your Personalized Essay in 3 Hours or Less!

We use cookies to personalyze your web-site experience. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy .

- Instructions Followed To The Letter

- Deadlines Met At Every Stage

- Unique And Plagiarism Free

Advertisement

- Previous Issue

- Previous Article

- Next Article

Why Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Matter for Patient Safety

- Split-Screen

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

- Peer Review

- Open the PDF for in another window

- Cite Icon Cite

- Get Permissions

- Search Site

Meghan B. Lane-Fall; Why Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion Matter for Patient Safety. ASA Monitor 2021; 85:42 doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ASM.0000798588.38346.fc

Download citation file:

- Ris (Zotero)

- Reference Manager

The recent focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) has highlighted many of the ways that individuals and organizations in health care are fallible; for example, by making decisions informed by social group membership instead of factors more germane to such decisions. We make patient care safer in part by introducing routinization and standardization and by engineering systems that are resilient in the face of human fallibility. It may seem, then, that the steps we take to ensure safety would obviate DEI concerns. In reality, we encounter DEI issues in much of the safety work that we do as members of the anesthesia and perioperative care team. Confronting and learning from these issues can make us better clinicians and team members.

As a leader in DEI, I find it helpful to ground conversations in this space with operational definitions of terms often used imprecisely. Diversity is a characteristic of groups (i.e., a single person cannot be “diverse”) that indicates a range of lived experience ( Acad Med 2015;90:1675-83 ). I think of characteristics that shape peoples' perspectives on the world, work, problem solving, and relationships to other people. In the U.S., conversations about diversity often center on race, ethnicity, and gender identity, but many additional aspects of experience are relevant to safe patient care, including age, languages spoken, physical mobility, body size, handedness, and visual acuity, to name just a few. Equity is about fairness and includes both opportunity and addressing barriers (Organizational Behavior, Theory, and Design in Health Care. 3rd edition, 2021). This might manifest as avoiding dissimilar treatment for similar behaviors, such as women and men being treated differently for speaking directly or raising their voice. I think of inclusion as a sense of belonging, which requires an organizational culture that welcomes differing perspectives. Inclusion does not mean that consensus needs to be achieved in all decisions, but an inclusive culture is one with strong psychological safety and the ability to take “interpersonal risks” like speaking one's mind without a fear of ridicule, retribution, or censure ( Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2014;1:23-43 ). Importantly, the organizational benefits of diversity depend critically on inclusion (Organizational Behavior, Theory, and Design in Health Care. 3rd edition, 2021).

“In reality, we encounter DEI issues in much of the safety work that we do as members of the anesthesia and perioperative care team. Confronting and learning from these issues can make us better clinicians and team members.”

What does this have to do with safety? Let's think about our clinical environment as work systems, as engineers do. In one human factors model, we think about the work system as having five basic components: the care team, tools and technologies, the physical environment, organizational conditions , and the tasks we perform ( Appl Ergon 2020;84:103033 ). I submit that DEI is relevant to all five of these components. Many recent articles have focused on the value of diverse and inclusive care teams. Here I focus on the perhaps less obvious intersections between DEI and the remaining four parts of the work system. A unifying theme across these work system elements is that diversity, equity, and inclusion are necessary to build and maintain systems that are responsive to different team members under a broad range of clinical conditions.

In considering tools and technologies , the concepts of usability and bias are relevant to DEI. Human factors engineers are trained to consider the needs of diverse groups in designing products like machines or software to be usable. Buttons, for example, should be operable by people regardless of dexterity, and user interfaces should be visible by people of different heights. Teams with diversity in these and other characteristics are poised to identify and ameliorate potential safety threats that can be encountered during clinical care. Diverse teams may also help identify or focus attention on bias in technologies, such as pulse oximetry and artificial intelligence ( APSF Newsletter 2021;36 ; BMJ 2020;368:m363 ).

Similar to tools and technologies, the physical environment in health care must be designed to accommodate a diverse workforce. Characteristics such as height, girth, reach, strength, dexterity, mobility, and sensory acuity all influence the way that we interact with our environment and may influence our ability to perform as expected in routine and emergent clinical scenarios (Handbook of Human Factors and Ergonomics in Health Care and Patient Safety. 2nd edition, 2011).

Organizational conditions and tasks are where I think equity and inclusion are most relevant. Our safety measures are developed and executed by people working in complex sociotechnical systems. For these systems to operate at peak performance, team members need to be confident that they will be treated equitably and that their perspectives will be considered in the design, evaluation, and optimization of the systems in which they work. In short, they need to perceive psychological safety. In their review of published research in health care and industry, Edmondson and Lei found that psychological safety was positively associated with organizational learning and organizational performance and that it may mitigate factors like conflict that can undermine performance ( Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 2014;1:23-43 ). Psychological safety is promoted by inviting input, listening to team members, and celebrating failures ( asamonitor.pub/3zSykTj ). It is undermined by explicit or implicit actions that exclude or alienate team members. Microaggressions (also called “subtle acts of exclusion”) experienced by marginalized groups could therefore compromise psychological safety and team functioning ( asamonitor.pub/2YArTH0 ).

As seen in other aspects of health care, like biomedical research and medical education, attention to DEI can broaden our perspectives and allow us to meet the challenges posed by shifting patient populations, innovations in care, and organizational constraints. In highlighting DEI issues relevant to our work system in anesthesia, I believe that applying this lens to safety can help us design better, more resilient, and safer teams and health care systems.

Meghan B. Lane-Fall, MD, MSHP, FCCM. Vice President and Member, Board of Directors, Anesthesia Patient Safety Foundation, and David E. Longnecker Associate Professor and Vice Chair of Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity, Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care, Perelman School of Medicine, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Most Viewed

Email alerts, related articles, social media, affiliations.

- About ASA Monitor

- Information for Authors

- Online First

- Editorial Board

- Advertising

- Career Center

- Rights & Permissions

- Online ISSN 2380-4025

- Print ISSN 2380-4017

- Anesthesiology

- ASA Monitor

- Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy

- Manage Cookie Preferences

- © Copyright 2024 American Society of Anesthesiologists

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

- Medical School Admission: Complete Guides

- Medical School Specialties: Complete Guides

- High-Yield Premed Resources

- Medical School Application Guides

- Medical School Personal Statement Guides

- Medical School Application Essays

- Medical School Recommendation Letters: Complete Guides

- Medical School Application Guides: Interviews

- Taking A Gap Year As A Premed

- MCAT Prep 101: Just Starting

- MCAT Success Stories

- Increasing Your MCAT Score

- MCAT Retaker

- MCAT Motivation

- MCAT Memorization Strategies

- MCAT CARS Guides

- MCAT Chem/Phys Guides

- MCAT Bio/Biochemistry Guides

- MCAT Psych/Soc Guides

- Non-Traditional MCAT Student

- All MedLife Articles

- Science Content Review

- Med School Application Coaching

- Live MCAT Courses

- FREE MCAT Resources

- Free MCAT Course

- MCAT Content Review

- MCAT Blog Articles

- 1:1 MCAT Tutoring

- MCAT Strategy Courses

- Meet The Mentors

Medical School Diversity Essay: Complete Guide

minutes remaining!

Back To Top

Admissions committees want to ensure their campus is as varied as possible, so they require additional diversity essays for medical schools.

Medical schools strive to draw candidates from diverse backgrounds so that each student can bring something unique to the school.

The diversity essay allows you to talk about your ethnicity or other distinctive characteristics and how those characteristics will benefit the campus community.

This article will give you a thorough understanding of a medical school diversity essay and the best tips on making a compelling one.

What is a Diversity Essay for Medical School?

Many secondary admissions require a diversity essay. If a diversity essay is suggested, you should still view it as a requirement because contributing additional, compelling materials increases your chances of getting accepted.

Sending extra resources will enable the admissions committees to understand your distinctive background better since they matriculate well-rounded, diversified, and experienced individuals. A recurrent element across purpose and vision statements on medical school websites is diversity.

This is due to the necessity for healthcare professionals who can relate to and treat a variety of patient populations in the medical industry.

Some institutions even have unique diversity declarations demonstrating their unwavering dedication to enrolling a diverse student body, including students of every color, religion, sexual orientation, identity, and experience in education and the workforce.

To further promote the advantages of diversity in medicine, admissions committees give unconventional applicants with non-science backgrounds substantial consideration and admit them.

What Counts as Diversity?

Put your worries aside if you are concerned that because you do not identify with a historically underrepresented group, you do not qualify as a diverse applicant.

Diversity in the context of med school applications does not mean that only members of racial or ethnic minorities should be admitted.

Yes, minority applicants are diverse and are urged to submit applications to medical school, but diversity does not stop there.

Instead, diversity is viewed broadly to embrace a variety of areas. In addition, everyone is diverse because each person may draw on their own particular experiences and backgrounds, which is advantageous in the healthcare industry.

Candidates might be diverse due to a variety of distinct qualities and traits:

- Career switchers

- Returning older students

- Non-traditional candidates

- Returning parents to the workforce

- Candidates with military experience

- Candidates who did not major in science

- Candidates from challenging socioeconomic backgrounds

- Candidates who persevere in the face of enormous difficulties

- Historically underrepresented groups (including those based on race, ethnicity, gender, and gender identity as well as language, sexual orientation, and more )

You will have many examples to pick from if you widen your idea of diversity to include your learning experiences and worldviews.

8 Tips for Answering Medical School Diversity Essays

Diversity essays for medical schools give candidates with diverse backgrounds, unusual families, unorthodox educations, or other different experiences a chance to describe how their distinctiveness would enrich the campus community.

Your diversity essay is your chance to show the medical school you are applying to what you have to offer. Hence, it is a must that you ensure that you stand out among the other candidates.

Below are the best tips when writing your diversity essay for medical school.

Decide What Makes You Unique

Before you even start writing, develop a list of the characteristics in your background that set you apart.

Consider your schooling, employment history, extracurricular activities, upbringing, family life, and other facets of your path to medical school.

The purpose of brainstorming is to stimulate your creative thinking.

Do not worry about spelling, grammar, or sentence structure at this time. Your objective is to write down as many thoughts as you can so that you can start to develop a narrative for your diversity essay using one to three examples.

Focus on Your Story

This is a crucial aspect since many applicants who do not belong to a particular socioeconomic or ethnic group feel they cannot bring variety to a potential medical school class.

Unfortunately, this is a typical misunderstanding. Diversity is not only about your skin tone or the religion your ancestors practiced.

Did you grow up in a non-traditional environment?

This could involve losing a family member, having a brother or other family member who is ill or disabled, growing up in a home with only one parent, starting work at an early age, or many other things. There are a ton of different things that could be a part of your variety.

Do not Hold Back

Do not be reluctant to share your experiences. Simple or uninteresting anecdotes will not stand out. What specific information about yourself can you include to support your arguments?

Clearly state how the encounter affected you.

What did you discover?

How has the experience helped you grow in terms of your character?

How did you utilize what you learned and acquired skills to further your medical education and, ultimately, your career?

In addition, keep in mind that your experience can come up during the interview. Therefore, any information you include in your application is fair for questioning throughout the interview process.

Never write about an experience that you will not be able to discuss in person. It is beneficial to be honest and vulnerable. Still, it is equally important that you keep your cool throughout the interview.

Make Sure Your Story Has a Potential Contribution to the Community

Occasionally, candidates focus so much on their differences that they lose sight that being unique is a means, not an end, to an objective.

These distinctions and distinctive traits/experiences must have a purpose. They must assist in demonstrating your merit for a place at the roundtable discussion for medical schools.

Being a two-time offender or a habitual absence from school are two examples of unusual qualities and experiences for a medical school applicant . Will they aid you in entering?

Most likely not, and for apparent motives. Concentrating on another subject for your medical school diversity essay might be best.

The idea is straightforward. Once you have determined your unique traits, your primary responsibility is to explain how that distinctiveness will enable you to offer something extraordinary both in and outside school.

Enter your text here...

Keep Developing Your Narrative

The coherent story you weave throughout your primary application about who you are and why you want to be a doctor is crucial to a successful application.

Nothing different applies to the second application. The diversity essay allows you to develop the story you started in your main application.

The diversity essay must flow naturally with the remainder of your secondary application. Each application component should support your narrative and offer further background information on how you came to be where you are.

Do Not Repeat Yourself

Make sure you are expanding on any experiences, moments, or lessons you have already addressed if you will bring them up again. You must include more background if you use the same examples in your secondaries.

Do not say the same thing twice in your secondary. Your initial application is already available to the admissions committee. Repeating the same tales will not give the admission committee any new information about you. The secondary chapters offer you the chance to develop your plot further.

Have Enough Evidence of What You Are Writing

Even if diversity may be an elusive idea or characteristic, it needs concrete proof. Therefore, diversity essays for med school are not comprehensive without a clear explanation of how your "diversity" relates to your experiences.

You cannot, for instance, blatantly claim that your history as an immigrant son or daughter and first-generation college student gives you some important insight into the concerns of immigrant populations.

You still need to provide evidence, even though it makes sense that you would be more knowledgeable than people from wealthy, non-immigrant families. Clearly state the links.

Therefore, the ideal strategy is not to overemphasize how significant your minority identity is if you do choose to focus on ethnic, cultural, or religious diversity.

Instead, a compelling essay might concentrate on your commitment to diversity and social justice issues or your efforts to address the health disparities between minorities and non-minorities. It could also be your encounters that show a concrete proof of your cross-cultural competence in patient or client interactions.

These three subjects are not exhaustive but could serve as an excellent starting point.

Proofread and Double-Check Your Diversity Essay

Spend some time going over a few crucial details in your article again. Ensure the element or elements you emphasize have real personal significance for you. Then, reread your essay one last time to ensure you genuinely respond to the question.

The diversity essay is multifaceted. For example, one school might require you only to list any noteworthy aspects of your background.

At the same time, another would want you to explain how those aspects will improve their curriculum or influence your future line of work.

Additionally, make sure you relate your attributes to medicine, particularly to the institution you are applying to.

Medical School Diversity Essay Sample Prompts

The leading schools' diversity essay prompts are provided below to give you an idea of what is anticipated. Remember that each of these prompts has a consistent theme.

Specifically, medical schools are interested in your broad diversity and how it will benefit the institution's purpose, vision, and student body.

Larner College of Med – University of Vermont

The Larner College of Medicine understands that diversity embraces all of a person's experiences and goes beyond their self-identified or unidentified identities. Consider a period when you gained knowledge from a person or organization that is different from yourself.

Mayo Med School – Mayo Clinic

Our individual inflections, which make up our diversity, distinguish us from one another or bind us together. Describe how your personal and professional activities reflect your relationship to your own variety and the diversity of others.

Stanford University School of Medicine

The diversity of an entering class is viewed by the admissions committee as a crucial component in advancing the school's educational purpose. The Committee on Admissions encourages you to address any distinctive, personally significant, and/or challenging aspects of your background.

These aspects may include how well you were educated as a child, your gender, your sexual orientation, any physical disabilities, and life or employment experiences.

Please explain how these influences have shaped your aspirations and training for a future in medicine and how they might enable you to make a distinctive contribution to the Stanford learning environment.

University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine

The Pritzker Sch of Medicine at the University of Chicago is committed to encouraging diverse students with an extraordinary promise to become leaders and innovators in science and medicine for the benefit of humanity. This is done in an environment of multidisciplinary scholarship and discovery.

Our essential objective and educational ethos are expressed in our mission statement. In particular, it emphasizes how important diversity is to us since we believe that variety in the student body is vital to academic performance. Please submit an essay outlining how you would further Pritzker's goal and promote diversity there.

Wake Forest School of Medicine

We want to develop doctors who can relate to various patient populations, even though they may not have a common background. Tell us about a situation that helped you to see the world more broadly or to understand people who are different from you better and what you took away from it.

Medical School Diversity Essay Samples

The diversity essay questions you are given by various institutions may differ, meaning that the terminology and what is being asked of you will be unique to each institution.

To prepare yourself, reading a few samples is a good idea.

While the general substance of each prompt will not fluctuate significantly depending on the school, you might want to change the organization or sequencing of the content for various prompts.

Here are some of the best samples of medical school diversity essays.

Prompt: Diversity can take many different shapes. How do you think you could add to the class's diversity?

I feel fortunate to have a solid sense of my roots. Being in Italy frequently throughout my life has allowed me to see how this culture's ideologies differ from those of the United States.

Italian society is frequently tarnished by the myth that its people are idle or unwilling to put forth the effort. People will, in my opinion, see a community where love and camaraderie are more critical than monetary possessions if they view the world objectively.

As a result, there is a considerable emphasis on other people's health and wellness. There is always time for family dinner, a coffee with a friend, or a mind-clearing walk in the evening.

Growing up, my family always ensured everyone had access to food and conversation. I adhere to this concept and see working in the healthcare industry as a chance to assist people in leading fulfilling lives and seeking their own happiness.

Healthcare experts have continuously allowed my loved ones to live independently and be there throughout my life. They have provided me with a service and a gift, and I want to spend the rest of my life sharing that gift with others. My passion for studying medicine and my holistic way of living have been influenced by my culture, background, and experiences in life.

In addition to being a physician in training, I will bring these qualities of empathy and holistic care to my role as a classmate who supports others through medical school challenges.

Prompt: Without restricting the discussion to your identity, please elaborate on how you see yourself supporting the fundamental principles of inclusion and diversity at our school of medicine and the medical field.

When I think about diversity, the first thing that springs to me is "a difference of opinion." As a member of the debate club and a student with a budding interest in classical philosophy, I've come to understand the importance of having a variety of viewpoints. I think advancement is basically impossible without the ability to question our assumptions and expectations about the world and ourselves.

My responsibility as a volunteer scribe at a mobile clinic was to document the specifics of patient examinations. We saw primarily middle-aged or older people. One patient, Paul, showed up at the mobile clinic with a nasty cut on his foot that he claimed was caused by catching his foot on an old rolled-up fence behind his barn. He was skeptical when we suggested he get a tetanus injection. He expressed why he didn't think immunizations were effective.

It was crucial to avoid conflict. We emphasized that while maintaining his autonomy was our first goal, he was likely to contract tetanus, which is potentially fatal. We explained to him that the tetanus vaccine has contributed to a 95% reduction in tetanus cases since about 1950. The patient thought for a bit, then agreed to the vaccination and thanked us for our assistance before leaving. I want to provide the University of Maryland School of Medicine with what I've learned through polite, open communication.

Prompt: What diverse characteristics and experiences could you offer the community of medical schools?

Our training for the Peace Corps taught us a metaphor for our work. Our new neighborhood could be compared to a square if America, our country of origin, were a circle. Volunteers like me formed triangles. The purpose? We could see both as legitimate modes of existence since we were a part of both.

The majority of us have several identities. I also practice living in the center by driving a boat across an island chain. The translator assumes a crucial role in Ann Patchett's Bel Canto, one of my favorite books, which tells the tale of foreign ambassadors who are taken hostage during a banquet. He is the one who must communicate, interpret, and give voice to the blank spaces between characters.

I have had many opportunities to translate for my siblings, parents, Belizean villagers, and others in my health advocacy work. I am the oldest child, a former Peace Corps volunteer, and a member of a mixed-race family.

My "triangular" persona enables me to take an alternative perspective on issues. The medical school is a hub for creative thinking and an entrepreneurial community. I wish to take part in the translation of differences and support of evidence-based solutions to health issues.

I believe that to fulfill my duty, I must be willing to try to comprehend others. My capacity to stand in two places, ears and heart open, enable dialogue, and give my perspective from a place of collaborative appreciation, will be my most outstanding contribution to the medical school community. In a silo, growth cannot take place. It starts with acknowledging the significance of all identities while learning from and working with others.

Additional FAQs – Medical School Diversity Essay

Do all medical schools require a diversity essay, why is diversity good in medical school, you're no longer alone on your journey to becoming a physician.

The Importance of Diversity and Inclusion in the Healthcare Workforce

Affiliation.

- 1 Obesity Medicine Physician Scientist, Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Division of Neuroendocrine and Pediatric Endocrinology, Affiliated Faculty, Mongan Institute of Health Policy Associate, Disparities Solutions Center, United States. Electronic address: [email protected].

- PMID: 32336480

- PMCID: PMC7387183

- DOI: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.03.014

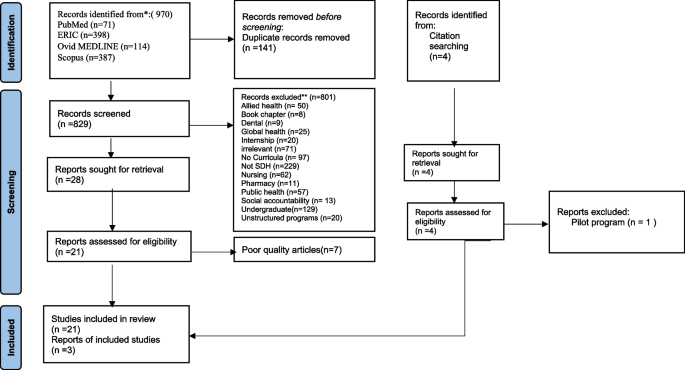

Background: Diversity and inclusion are terms that have been used widely in a variety of contexts, but these concepts have only been intertwined into the discussion in healthcare in the recent past. It is important to have a healthcare workforce which represents the tapestry of our communities as it relates to race/ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, immigration status, physical disability status, and socioeconomic level to render the best possible care to our diverse patient populations.

Methods: We explore efforts by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME), the Institute of Medicine (IOM), and other medical organizations to improve diversity and inclusion in medicine.

Conclusion: Finally, we report on best practices, frameworks, and strategies which have been utilized to improve diversity and inclusion in healthcare.

Keywords: Diversity; Healthcare; Inclusion; Workforce.

Copyright © 2020 National Medical Association. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

- Cultural Diversity*

- Delivery of Health Care / organization & administration

- Health Personnel*

- Health Workforce*

- Societies, Medical

- United States

Grants and funding

- L30 DK118710/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

- P30 DK040561/DK/NIDDK NIH HHS/United States

6 Medical School Diversity Essay Examples (Ranked Best to Worst!)

Most medical school diversity essay prompts give little away when it comes to helping you with ideas on what to write. Without seeing examples? It’s incredibly difficult to know where to get started!

As a medical student with an undergrad in English, I thought I’d run my eye over some of the web’s popular medical school diversity essay examples.

Ranking these six examples from best to worst, I’ll give a critique of each along the way.

All with the hope of better helping you craft your own diversity essays with a bit more ease and expertise!

Ready to get started? Let’s go.

Want some quick writing tips first? Check out this article; How To Write An Awesome Diversity Essay In Medical School (5 Quick Tips) .

I’ll be ranking each of these from, what I feel, is the worst to best.

Note : It’s not my intention to be disparaging (having any one of these examples is a huge plus), but rather entertaining. I hope it’ll be fun figuring out what I’d look for if I was part of a Med School Admissions Team!

Medical School Diversity Essay Examples

Make sure you click through the links on each of these essays. Not only does this help give credit to other people’s work, but you’ll also benefit from their own explanations and critique!

6. Diverse Backgrounds – Chronicles of a Medical Student

My father gave me two things when I was young: early exposure to diverse people and a strong desire to learn to work cross-culturally. But the most important thing he taught me was to be a life-long learner through interaction with people from diverse backgrounds. Our house was always a second home for international students studying at nearby universities. I can remember playing Jenga with Russian engineering students or seeing our kitchen taken over by Korean music students. During college, I continued to learn to relate to people from many backgrounds through an internship to Southeast Asia in 2006. I found that humility and a genuine desire to learn about someone’s culture opened doors to relationships that would have remained closed. If students fail to interact with people of different cultures, preferring to cluster where they are comfortable, the benefit of a diverse campus is lost. My cross-cultural experiences have prepared me to learn to embrace ethnic and cultural diversity. – Chronicles of a Medical Student

This is by no means a bad essay – and there’s a lot of personal relevance that shines through – it’s just that it misses the mark a little when it comes to drawing parallels between the past and the future.

Although the student shows they’ve had a range of experiences that’s brought them into contact with diverse peoples and cultures, it doesn’t really answer how this lends itself to medicine.

Personally, I find myself wanting to know more about how these experiences have shaped this person’s desire to become a doctor!

5. Connecting Through Cultures – BeMo

I am extremely fortunate to have a strong connection to my roots. Spending time in Italy throughout my life has allowed me to see how the ideology of this culture differs from that in the United States. The Italian society is often marred by the stereotype that they are lazy, or not willing to work. I believe that if one truly sees the society from an objective lens, they will see a society that derives their happiness less from material objects and more from love and companionship. Resultantly, there is a monumental emphasis placed on the health and well-being of others. There is always time for a family meal, a coffee with a friend, or an evening walk to clear one’s mind. Growing up my family always made sure everyone had enough to eat, and someone to talk to. I believe in this ideology and view the healthcare field as the opportunity to help others live a full, and fruitful life pursuing their own happiness. Throughout my life, healthcare professionals have consistently given my loved ones the ability to live autonomously and be present in my life. It is a service and a gift that they have given me and a gift I wish to spend my life giving others. My culture, upbringing, and life experiences have fostered my desire to purse medicine and my holistic approach to life. I will bring these elements of empathy and holistic care not only as a training physician, but as a fellow classmate who is there for others through the rigors of medical school. – BeMo

There’s a lot to like about this essay, especially the way they talk about a different culture (Italy) and how it fuels that desire to become a physician.

Where I feel it could be lacking is in drawing upon specific experiences (extracurriculars) diverse enough to pair well with an application.

They perhaps waste the second paragraph a little by repeating a similar sentiment; “a desire to pursue medicine and a holistic approach to life.”

It’s maybe just a bit too unspecific and uncreative.

4. Sharing Passions – Shemassian Consulting

There are many things a girl could be self-conscious about growing up, such as facial hair, body odor, or weight gain. Growing up with a few extra pounds than my peers, I was usually chosen last for team sports and struggled to run a 10-minute mile during P.E. classes. As I started to despise school athletics, I turned towards other hobbies, such as cooking and Armenian dance, which helped me start anew with a healthier lifestyle. Since then, I have channeled my passions for nutrition and exercise into my volunteering activities, such as leading culinary workshops for low-income residents of Los Angeles, organizing community farmer’s markets, or conducting dance sessions with elderly patients. I appreciate not only being able to bring together a range of people, varying in age, socioeconomic status, and ethnicity, but also helping instill a sense of confidence and excitement that comes with making better lifestyle decisions. I have enjoyed encouraging kids in the inner city to combat similar issues of weight gain and low self-esteem through after-school gardening and physical activity lessons. Now, I hope to share my love for culinary nutrition and fitness with fellow medical students at UCLA. As students, we can become better physicians by passing on health and nutrition information to future patients, improving quality of life for ourselves and others. – Shemassian Consulting

This is an example of just how creative you can get when it comes to essay writing – especially when you might not consider yourself “typically diverse” too!

The experiences of this applicant are ones that most of us, growing up in the West, are familiar with. Yet they expertly turn these “standard problems” into something personal that communicates to the reader why they got involved with volunteering and community projects in the first place (i.e. not just because med school admissions teams told them they had to!)

Even if the bottom line is a little generic; “passing on health and nutrition information to future patients”; it’s that honesty at the beginning that makes it seem like a genuine essay.

The way it addresses the school specifically is another nice touch.

3. Multiple Identities – Motivate MD

In Peace Corps training, we learned a metaphor for our service. If our home, America, was a circle, our new community could be described as a square. We, as volunteers, were triangles. The point? We were part of each; not quite one, nor the other, but able to recognize both as valid ways of being. Most of us have multiple identities. I also bring practice of inhabiting the middle; the boat in a channel between islands. In one of my favorite novels, Ann Patchett’s Bel Canto, the story of international diplomats held hostage at a party, the translator plays a central role. It is he who must interpret and communicate; give voice to space between characters. As a Returned Peace Corps Volunteer, oldest child, and part of a mixed-race family, I’ve had many opportunities to translate; on behalf of my siblings (to my parents), my parents (to my siblings), Belizean villagers, & others in my health advocacy work. My “triangular” identity helps me approach problems differently. _______Medical School is a place for visionary thinking; a community of innovators. I want to be part of curiosity-driven inquiry; translating differences & supporting evidence based solutions to health problems. I see my role as one that can only be attempted through willingness to understand others. My greatest contribution to the medical school community at _________will be my ability to stand in two places, ears & heart open, facilitating dialogue & sharing my perspective from a place of collaborative appreciation. Growth cannot occur in a silo. It begins in learning from & with other people, recognizing the value of all identities. – Motivate MD

This is a really awesome example that’s formatted perfectly.

Compact, punchy, and making great use of metaphor, this does so many right things when it comes to putting together a strong diversity essay.

What I like most about it is the way it plays on the cultural background of the applicant to explain how they will contribute to the school’s community moving forward.

This is a really important thing to consider!

But what’s also neat is the way they link reading and literature to their own cross-cultural role. That’s a nice creative flourish.

2. Diversity Through Faith – University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

In the sweating discomfort of the summertime heat, I walked through Philadelphia International Airport with several overweight bags, tired eyes, and a bad case of Shigella. Approaching Customs, I noticed the intensity and seriousness on the faces of the customs officers whose responsibility were to check passports and question passengers. As I moved closer to the front of the line, I noticed someone reading a foreign newspaper. The man was reading about the Middle Eastern conflict, a clash fueled by religious intolerance. What a sharp contrast to Ghana, I thought. I had just spent three weeks in Ghana. While there I worked, studied their religions, ate their food, traveled and contracted malaria. Despite all of Ghana’s economic hardships, the blending of Christianity, Islam, and traditional religion did not affect the health of the country. When I reached the front of the line, the customs officer glanced at my backpack and with authoritative curiosity asked me, “What are you studying?” I responded in a fatigued, yet polite voice, “Religious studies with a pre-med track.” Surprised, the officer replied rhetorically, “Science and religion, interesting, how does that work?” This was not the first time I had encountered the bewildered facial expression or this doubtful rhetorical question. I took a moment to think and process the question and answered, “With balance.” Throughout my young life I have made an effort to be well-rounded, improve in all facets of my personal life, and find a balance between my personal interests and my social responsibility. In my quest to understand where I fit into society, I used service to provide a link between science and my faith. Science and religion are fundamentally different; science is governed by the ability to provide evidence to prove the truth while religion’s truth is grounded on the concept of faith. Physicians are constantly balancing the reality of a person’s humanity and the illness in which they are caring for. The physicians I have found to be most memorable and effective were those who were equally as sensitive and perceptive of my spirits as they were of my symptoms. Therefore, my desire to become a physician has always been validated, not contradicted by my belief system. In serving, a person must sacrifice and give altruistically. When one serves they sacrifice their self for others benefit. Being a servant is characterized by leading by example and striving to be an advocate for equity. As a seventh grade math and science teacher in the Philadelphia public school system, everyday is about sacrifice and service. I sacrifice my time before, during and after-school; tutoring, mentoring and coaching my students. I serve with vigor and purpose so that my students can have opportunities that many students from similar backgrounds do not have. However, without a balance my effectiveness as a teacher is compromised. In February, I was hospitalized twice for a series of asthma attacks. Although I had been diagnosed with asthma, I had not had an attack since I was in middle school. Consequently, the physicians attributed my attacks to high stress, lack of sleep, and poor eating habits. It had become clear to me that my unrelenting drive to provide my students with a sound math and science education without properly balancing teaching and my personal life negatively impacted my ability to serve my students. I believe this experience taught me a lesson that will prove to be invaluable as a physician. Establishing an equilibrium between my service and my personal life as a physician will allow me to remain connected to the human experience; thus enabling me to serve my patients with more compassion and effectiveness. Throughout my travels and experiences I have seen the unfortunate consequences of not having equitable, quality health care both domestically and abroad. While many take having good health for granted, the financial, emotional, mental, and physical effects illnesses have on individuals and families can have a profound affect on them and the greater society. Illness marks a point in many people’s lives where they are most vulnerable, thus making a patient’s faith and health care providers vital to their healing process. My pursuit to blend the roles of science and religion formulate my firm belief that health care providers are caretakers of God’s children and have a responsibility to all of humanity. Nevertheless, I realize my effectiveness and success as a physician will be predicated mostly on my ability to harmonize my ambition with my purpose. Therefore, I will always answer bewildered looks with the assurance that my faith and my abilities will allow me to serve my patients and achieve what I have always strived for and firmly believe in, balance. – University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

First things first, you’re incredibly unlikely to get the chance to write this much for a diversity essay.

Most of the prompts you’ll see from med schools are in the 500 words range. As evidenced in the following article…

Related : Medical School Diversity Essay Prompts (21 Examples)

What I love about this example here however is the narrative. This essay really paints a picture. And has an awesome hook in its opening about the writer experiencing shigellosis!

Other things it does excellently include discussing diverse experiences (teaching, preaching, illness, etc.) and showing a firm understanding of the roles doctors play across societies and cultures.

It shows real passion and drive, as well as someone struggling on a more personal level to make sense of their own journey.

I imagine this would stand out well from the crowd.

1. Exploring Narratives – Morgan (The Crimson)

I started writing in 8th grade when a friend showed me her poetry about self-discovery and finding a voice. I was captivated by the way she used language to bring her experiences to life. We began writing together in our free time, trying to better understand ourselves by putting a pen to paper and attempting to paint a picture with words. I felt my style shift over time as I grappled with challenges that seemed to defy language. My poems became unstructured narratives, where I would use stories of events happening around me to convey my thoughts and emotions. In one of my earliest pieces, I wrote about a local boy’s suicide to try to better understand my visceral response. I discussed my frustration with the teenage social hierarchy, reflecting upon my social interactions while exploring the harms of peer pressure. In college, as I continued to experiment with this narrative form, I discovered medical narratives. I have read everything from Manheimer’s Bellevue to Gawande’s Checklist and from Nuland’s observations about the way we die to Kalanithi’s struggle with his own decline. I even experimented with this approach recently, writing a piece about my grandfather’s emphysema. Writing allowed me to move beyond the content of our relationship and attempt to investigate the ways time and youth distort our memories of the ones we love. I have augmented these narrative excursions with a clinical bioethics internship. In working with an interdisciplinary team of ethics consultants, I have learned by doing by participating in care team meetings, synthesizing discussions and paths forward in patient charts, and contributing to an ongoing legislative debate addressing the challenges of end-of-life care. I have also seen the ways ineffective intra-team communication and inter-personal conflicts of beliefs can compromise patient care. By assessing these difficult situations from all relevant perspectives and working to integrate the knowledge I’ve gained from exploring narratives, I have begun to reflect upon the impact the humanities can have on medical care. In a world that has become increasingly data-driven, where patients can so easily devolve into lists of numbers and be forced into algorithmic boxes in search of an exact diagnosis, my synergistic narrative and bioethical backgrounds have taught me the importance of considering the many dimensions of the human condition. I am driven to become a physician who deeply considers a patient’s goal of care and goals of life. I want to learn to build and lead patient care teams that are oriented toward fulfilling these goals, creating an environment where family and clinician conflict can be addressed efficiently and respectfully. Above all, I look forward to using these approaches to keep the person beneath my patients in focus at each stage of my medical training, as I begin the task of translating complex basic science into excellent clinical care – Morgan, Harvard Med Matriculant; The Crimson

You can see why this student successfully made it into Harvard Med!

Again, they tell a story. They hook us in curiously with a statement that we want to know the answer to. And we continue reading while the greater narrative unfurls.

What this example does perfectly is interweaving the personal with the playful while showing a diversity of thought (writing about a local boy’s suicide etc) and a commitment to expanding her perspective.

Showing (not telling) how this pastime has enriched her staple extracurriculars (internships, research, clinical experience, etc.), it shows real thought as to the future of medicine and exactly where this future physician wants to take it.

The level of detail and specificity shows that she’s really thought about how she wants to develop her career based on her existing clinical experience.

This is the type of diversity essay I’d aspire to write!

Final Thoughts

Hopefully, in ranking these examples and discussing their finer points, you have some better ideas about how you might want to approach writing your own diversity essays.

While it’s impossible to really comment on the appropriateness of each example, namely because we don’t know the exact prompt, they still give plenty of food for thought.

Just remember to follow your own prompts where possible, and make sure to go over your school’s mission statements to help tailor your own essays.

I’m pretty confident you can write essays as effective as these!

Related Articles

- How To Conclude Your Medical School Personal Statement

Born and raised in the UK, Will went into medicine late (31) after a career in journalism. He’s into football (soccer), learned Spanish after 5 years in Spain, and has had his work published all over the web. Read more .

Sign up to our Newsletter

How to write the perfect diversity essay for medical school.

Reviewed by:

Akhil Katakam

Third-Year Medical Student, Lewis Katz School of Medicine at Temple University

Reviewed: 5/19/23

Wondering how to write the perfect diversity essay for medical school? Stick around to find out our top tips!

The medical school admissions process is becoming increasingly holistic. Admissions committees look at more than just your GPA and extracurricular activities to decide your candidacy.

There is a significant need to diversify the medical field, so various other selection factors play an important role in your success. Many medical schools require secondary essays as part of their application materials to help them assess candidates’ strengths, desirable qualities, experiences, and insights.

Some schools require the medical school diversity essay, so it’s essential to understand the ins and outs of what makes a compelling essay stand out. This blog will review the definition of diversity in the context of medical school applications and provide examples of prompts from top schools.

You will also learn how to write a diversity essay, including tips on what to include and the proper format to follow. Lastly, we’ll provide an example that tells an interesting story and connects a candidate’s diversity with a medical school’s mission and vision.

Get The Ultimate Guide on Writing an Unforgettable Personal Statement

What is a Diversity Essay for Medical School?

A diversity essay is required or recommended for many medical school secondary applications . In the cases that the diversity essay is recommended, you should still consider it as a requirement, as submitting additional, strong materials maximize your chances of acceptance.

Admissions committees matriculate well-rounded, diverse, and experienced candidates , so sending more materials will help them gain a better overview of your unique background.

If you look at medical school websites, there is a common theme among mission and vision statements: diversity. This is because the medical field needs to diversify health care practitioners who can empathize with and effectively treat various types of patient populations.

Some schools even have separate diversity statements that show their ongoing commitment to matriculate a diverse student body, representing every race, religion, sexual orientation, identity, educational/professional background, and more.

In fact, admissions committees are even seriously considering and matriculating non-traditional applicants from non-science backgrounds to further serve the benefits of diversity in medicine.

What Counts as Diversity?

If you’re worried that you don’t count as a diverse candidate because you don’t belong to a historically underrepresented group, cast your concerns aside. Diversity in the context of diversity essays for medical school is not a code word to only matriculate ethnic or racial minorities.

Yes, candidates from minority groups are diverse and are encouraged to apply to medical school, but diversity doesn’t end there. Rather, diversity is broadly defined to include many categories. Everyone is diverse because everyone has their own unique experiences and backgrounds to draw from, which is valuable in healthcare.

There are many distinguishing factors and characteristics that can make candidates diverse:

- Non-traditional applicants (2 or more gap years before med school)

- Candidates who are non-science majors

- Career changers

- Candidates with a disability

- Historically underrepresented groups (racial, ethnic, gender and gender identity, linguistic, sexual orientation, religion, and more)

- Older returning students

- Applicants with military service

- Parents returning to the workforce

- Candidates who overcome extreme challenges and adversity

- Applicants with a difficult socioeconomic background

If you broaden your understanding of diversity to include your unique learning experiences and worldviews, you will have a plethora of examples to choose from to write a powerful diversity essay.

Examples of Diversity Essay Prompts

The following are previous diversity essay prompts from top medical schools to give you an idea of what a diversity essay prompt looks like . You’ll notice there is a similar thread in all of these prompts: medical schools want to know about your diversity in broadly defined terms, and most importantly, how it will enhance the school’s mission, vision, and student body.

Prompt: Stanford University School of Medicine

“ The Committee on Admissions regards the diversity (broadly defined) of an entering class as an important factor in serving the educational mission of the school. The Committee on Admissions strongly encourages you to share unique, personally important and/or challenging factors in your background which may include such discussions as the quality of your early education, gender, sexual orientation, any physical challenges, and life or work experiences. Please describe how these factors have influenced your goals and preparation for a career in medicine and may help you to uniquely contribute to the Stanford learning environment.”

Prompt: Wake Forest School of Medicine

“We seek to train physicians who can connect with diverse patient populations with whom they may not share a similar background. Tell us about an experience that has broadened your own worldview or enhanced your ability to understand those unlike yourself and what you learned from it.”

Prompt: Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont

“The Larner College of Medicine at the University of Vermont recognizes that diversity extends beyond chosen and unchosen identities and encompasses the entirety of an individual’s experiences. Reflect on a time you learned something from someone or a group of people who are unlike yourself.”

Prompt: Columbia Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons

“Columbia Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons values diversity in all its forms. How will your background and experiences contribute to this important focus of our institution and inform your future role as a physician?”

Prompt :University of Chicago Pritzker School of Medicine

“At the University of Chicago, in an atmosphere of interdisciplinary scholarship and discovery, the Pritzker School of Medicine is dedicated to inspiring diverse students of exceptional promise to become leaders and innovators in science and medicine for the betterment of humanity. Our mission statement is an expression of our core purpose and educational philosophy. In particular, it highlights the value we place on diversity since we regard the diversity of entering class as essential for educational excellence. Please write an essay on how you would enhance diversity at Pritzker and advance the Pritzker mission.”

Use our tool to discover every U.S. medical school’s secondary essay prompts!

How to Write a Diversity Essay

If you’re having trouble figuring out how to write a diversity essay, take the following steps:

1. Identify What Makes You Unique

First, before you even begin to write, brainstorm the things in your background that make you unique. In particular, think about your education, work experience, extracurricular activities, upbringing, family life, and other aspects of your journey to medical school.

Brainstorming ideas is meant to get your creative juices flowing. At this point, don’t worry about grammar, spelling, or sentence structure. Your goal is to get as many ideas on paper as possible so that you can begin to craft a story that uses one to three examples for your diversity essay.

You can ask yourself the following questions to get started:

- Who are you at your core, at your best self?

- What experiences have defined you?

- How do you identify yourself, and how does this differ from society’s expectations of your identity?

- How have you overcome challenges, adversity, or rejection?

- Where did you grow up, and what was it like to live there? How do your geographic roots inform your worldview?

- What was your family life like?

- Have you faced a disability, injury, or illness? What did you learn, and how did you overcome these challenges?

- Are you a part of any teams, groups, or organizations? How have they contributed to your interpersonal skills?

Remember, admissions committees are interested in your story. You should never falsify information in your essays. Write what you know!

2. Pick 1-3 Meaningful Experiences to Potentially Write About

A compelling diversity essay consists of one or a few meaningful experiences instead of overloading the essay with brief mentions of too many examples. You should prioritize quality over quantity and weave a story that’s memorable to the admissions committee.

You should also be mindful of character limits. Every school has different requirements, so be sure you achieve the minimum character count and stay within the upper limits.

3. Outline the Structure of Your Diversity Essay

No matter the length of your secondary essays , you should always structure it with the following:

- An introduction that hooks the reader.

- A body that details your experience(s).

- A conclusion that concisely ties everything together with the school’s mission.

The introduction should begin to tell your main story. It should introduce your main talking points so that the reader knows what to expect in the essay. Strong introductions often have a hook, which can appear as the beginning of an interesting and evocative anecdote.

The body of your diversity essay should delve into your unique experience through reflective storytelling . Here is where you will go into compelling details about your examples. The body will also demonstrate how your diversity will be an asset to the school and your peers and colleagues.

It’s also important to show rather than tell. For example, rather than list all of the personal characteristics that make you diverse, use imagery and storytelling to show these personal characteristics in action.

Finally, the conclusion should neatly tie in your meaningful and diverse experiences to the pursuit of medicine. Your last sentences should leave the reader with a strong impression of why your diversity will be an asset to the school.

4. Write the First Draft

Draw from your notes and outlines to write the first draft. Excellent writing involves an evolution of multiple drafts, so don’t be discouraged if the first draft isn’t perfect.

You’re not striving for perfection here—you’re still in the beginning stages, so you should prioritize fully addressing the essay prompt with strong examples from your diverse background. Polishing your first draft can come later.

5. Revise and Edit Your Diversity Essay

Go over your draft with a critical eye. Ensure that all prompt components are thoroughly answered, check for spelling and grammatical mistakes, and proofread for proper syntax and sentence structure.

Look at the flow of your essay. The transitions from introduction, to the body, to the conclusion should be seamless and make sense. If you’re writing about a few experiences, ensure that they make sequential and logical sense. The transitions should feel natural, not jarring or out of place.

Have someone else look at your essay to offer objective feedback. This can be a trusted friend, family member, instructor, employer, peer, or mentor. Be open to constructive criticism and revise any areas that need improvement or further clarification/elaboration.

Diversity Essay Examples

The following diversity essay examples both tell compelling and memorable stories. As you read, consider how the essay transports you to another location and invites you to view medicine and health care from a unique perspective.

Note how the essay ties into the school’s mission, vision, and goals for diversifying health care. Finally, consider the overall structure of the essay: there is a tangible introduction, body, and conclusion.

“Being South Asian, I have firsthand knowledge of what it means not to access basic health care. As a child, my mother took me to Pakistan every year, where I spent summers with my grandfather, a top pediatrician in the nation. He had a free clinic attached to his home in Faisalabad, and his practice was so renowned and respected that people from all over the country would travel great distances to have my grandfather treat their children. Pakistan is a third-world country where a significant part of the population remains illiterate and uneducated due to the lack of resources and opportunities. This population is the most vulnerable, with extremely high numbers of infectious disease and mortality rates. Yet, it is entirely underserved. With the lack of hospitals, clinics, and doctor’s offices in rural Pakistan, parents of ailing children must travel great distances and wait in long lines to receive proper health care. Every summer at my grandfather’s clinic, from ages five to 17, my job was to open the doors to long lines of tired, hungry, and thirsty parents with their sick children. I would pass out bottled water and pieces of fruit. I would record names, where the patients came from, and the reasons for their visits. I would scurry back inside with the information for my grandfather to assess, and then he’d send me running back out again to let the next family inside. I learned in my formative years how to communicate with diverse patient populations with special needs and a lack of basic necessities. I learned to listen to every family’s unique reasons for their visit, and some of their desperation and pleading for the lives of their children will stay with me forever. When I get into medical school, I hope to share the story of how Gulzarah carried her dehydrated daughter for 12 miles in the Pakistani summer heat without rest (thanks to my grandfather, she later made a full recovery). I want to tell my peers that doctors like my grandfather are not only healers in biology but healers in the spirit by the way he made up heroic songs for the children and sang the fear out of their hearts. I want to show my peers that patients are unique individuals who have suffered and sacrificed to trust us with their health care, so we must honor their trust by providing quality treatment and empathy. My formative experiences in pediatrics contributed to my globally conscious mindset, and I look forward to sharing these diverse insights in my medical career.”

Example 2: University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

“‘911 operator, what’s your emergency?’ ‘My friend has just been shot and he is not moving!’ ‘Is he breathing?’ ‘I don't think so!’ ‘Are you hurt?’ ‘No.’ ‘Stay there, the paramedics are on their way.’ On April 10th 2003, at approximately 11pm, my best friend Kevin and I, intending to see a movie, headed out my front door. We never made it to see a horror movie; but our night was nothing close to mundane, when we became innocent victims to gang crossfire. As we descended my front door stairs two gunshots were fired and one person fell to the floor. Kevin was shot! I vividly recall holding him in my arms, and while he lost blood I almost lost my mind. All I wanted was to help, but there was nothing I could do. At 1am that morning Kevin's family and I sat in the emergency waiting room at Brookdale Hospital in Brooklyn, hoping and praying that the chief surgeon would bring us good news. While this event started me on my quest to become a medical doctor, at that moment all I could envision was a life of despondency. According to author Jennifer Holloway, ‘tragedy is a substance which can ignite the soul.’ When Kevin’s surgeon walked through the door of the emergency waiting room he did not have to say a word. Kevin’s family cried hysterically. I, on the other hand, could not cry. As fast as despondency had filled my heart, it was now gone; I was consumed by anger, frustration and motivation to change my life’s direction. The death of my best friend compelled me to pursue a career in medicine. This, I hope, will enable me to help save the lives that others try to take. In the fall of this event, I took my first biology and chemistry courses. By the end of the year I excelled as the top student in biology, received the Inorganic Chemistry Achievement Award and was encouraged to become a tutor in general biology and chemistry. Tutoring was a captivating experience for me. Questions raised by students challenged my understanding of scientific concepts and their application in patient care. To further develop my knowledge of medicine, I volunteered in the emergency department at Albert Einstein Hospital, in Bronx, NY. While shadowing doctors, I was introduced to triaging, patient diet monitoring and transitioning from diagnosis to treatment. This exposed me to some of the immense responsibilities of a doctor, but my 5 experience helping in the cancer ward was where I learned the necessity of humanity in a physician and how it can be used to treat patients. Peering through a window I saw Cynthia, a seven-year-old girl diagnosed with terminal cancer, laughing uncontrollably after watching her doctor make funny faces. For a moment not only did Cynthia forget that she was dying, but her smile expressed joy and the beauty of being alive. This taught me that a physician, in addition to being knowledgeable and courageous, should show compassion to patients. It also became clear to me that a patient’s emotional comfort is as important as their physical health, and are both factors that a physician considers while providing patient care. Although focused on medicine, I was introduced to research through the Louis Stokes Alliance for Minority Participation in Science. Here, I learned organic synthesis techniques, while working on a project to elucidate the chemical mechanisms of oxygen protein binding and its relationships to anemia. I also received the United Negro College Fund/Merck Science Initiative Research Scholarship that allowed me to experience cutting edge research in Medicinal Chemistry, with a number of world-class scientists. At Merck Research Labs, I learned the fundamentals of synthesizing novel compounds for drug discovery, and we focused on treatments for cardiac atrial fibrillation. This internship changed my view of medication and their origins, and left me with a deep appreciation of the challenges of medicinal research. I also now understand that medical doctors and research scientists have similar responsibilities: to solve current and future health issues that we face. Despite the tragedy that brought me to the hospital on April 10th 2003, the smells, the residents and the organized chaos of the emergency room have become an integral part of a new chapter in my life. On the day that my friend lost his life I found my soul in medicine. Today as I move forward on the journey to become a physician I never lose sight of the ultimate goal; to turn the dying face of a best friend into the smiling glow of a patient, just like Cynthia’s. A patient’s sickness can be a result of many things. But with the right medications, a physician’s compassion and some luck, sickness can be overcome, and the patient helped. In time and with hard work it will be my privilege to possess the responsibilities of a physician in caring for life.”

FAQs: Med School Diversity Essays

Here are our answers to some of the most frequently asked questions about how to write a diversity essay for medical school.

1. I’m Not an Underrepresented Minority, so How Can I Write a Diversity Essay for Medical School?

Diversity in the context of medical school secondary essays is not limited to race, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, or other historically underrepresented groups. Think of diversity in broader terms that include your unique experiences and insights, and write about how your diverse skill sets will enhance the school and the student body.

2. How Can I Write a Diversity Essay that Stands Out from Other Candidates?

Brainstorm unique experiences that you have had and narrow down one or two main experiences to weave compelling stories with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. You should prioritize the quality of your experiences and elaborate upon them rather than pack too many bullet points in a limited space.

3. I’m Not a Strong Writer, How Can I Improve My Diversity Essay for Medical School?

Writing is not a linear process, and even bestselling authors need skilled editors. Start small with outlines and notes, then flesh out the essay with details. Write multiple drafts. When you’re happy with a draft, ask friends, family, peers, colleagues, instructors, or mentors for objective feedback. You can also consult with our team of experts to help you.

4. Why Do Some Medical Schools Require Diversity Essays?

Medical schools want to diversify the field and accept candidates with unique backgrounds and skill sets. These students will go on to be leaders in health care, so a holistic admissions process ensures that the world’s future doctors represent diverse groups, perspectives, talents, and skill sets.

5. Where Can I Find More Prompts and Examples of Diversity Essays?

Browse the medical school’s website and read their application procedures. You can also contact the school’s admissions committee helpline for more information.

6. What Should I Avoid in my Medical School Diversity Essay?

Avoid spelling and grammar errors, an unprofessional or casual tone/language, controversial or offensive statements, embellishing stories, and negative outlooks. If your diversity essay addresses facing adversity, make sure to focus on a growth mindset, what you learned, and the positive outcomes of that experience.

7. How Long Should a Diversity Essay Be?