- Corrections

Ancient Greek Sculpture in the Classical and Hellenistic Periods

Ancient Greek sculpture was immensely influential in the development of Western art, in many ways shaping the understanding of beauty and aesthetics even in the modern world.

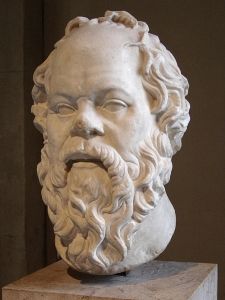

During the Hellenistic and Classical periods, ancient Greek sculpture aimed to depict the human form realistically but in an idealized and harmonious state. Greek Sculptors carefully studied human anatomy and sought to capture the essence of physical perfection and inner vitality. They believed the human body reflected divine beauty, and their sculptures became a medium to express this belief. Let’s discover how the ancient Greeks used sculpture, and some notable “masterpieces”.

Notable Uses of Sculpture in the Classical & Hellenistic Eras

Attic grave monuments.

Attica, the region surrounding Athens, was known for its distinctive burial rites and intricate grave markers. The Attic grave monuments of the 5th and 4th centuries BCE marked graves, commemorated the deceased, and conveyed their social status. In the 5th century BCE, the stele was the most prominent type of grave monument. A stele is a tall, rectangular, and upright piece of stone or marble. The Attic grave stelae displayed high artistic skill and attention to detail. They featured a variety of motifs, such as family members bidding farewell to their loved ones, children with pets and other animals, and war scenes. These sculptures emphasized the achievements and virtues of the deceased and their family.

In the 4th century BCE, there was a shift in the design of Attic grave monuments. The stelae began incorporating architectural elements such as triangular pediments, columns, and small temples. This architectural approach created an even more elaborate and exquisite appearance for the grave monuments. The sculptural decoration became more complex as well. Artists began to depict scenes from everyday life, such as banquets, hunting scenes, or the deceased engaging in athletic activities. These scenes aimed to reflect the interests and accomplishments of the dead and provide a glimpse into their idealized lives.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription, architectural sculpture.

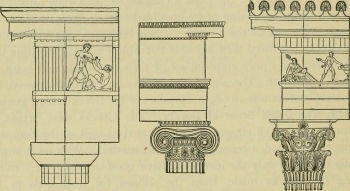

Architectural sculpture played a significant role in ancient Greek art and architecture. It was a prominent element in temples, public buildings, and even private houses. The sculptural decoration in ancient Greek architecture served multiple purposes. It added an aesthetic appeal to buildings, conveyed narratives from mythology and history, and reflected the religious beliefs and cultural values of the time. Here are some key architectural elements that could feature sculptured decoration:

- Metopes are rectangular spaces between the triglyphs on the Doric frieze of a temple. They were often decorated with relief sculptures depicting various mythological or historical scenes. Metopes were typically carved in high relief, creating a sense of depth, narrativity, and three-dimensionality.

- Pediments are the triangular spaces at the ends of a temple. Pediments were excellent locations for sculptural compositions. The pediments featured complex relief sculptures portraying mythological narratives or significant events related to the temple. The sculptures in pediments often pictured gods, goddesses, heroes, and mythological figures.

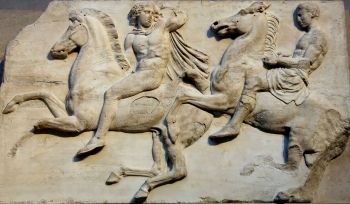

- Friezes are decorative bands located above the architrave of a temple. There were two main types: the Doric frieze and the Ionic frieze. The Doric frieze was characterized by alternating triglyphs and metopes. The metopes could contain relief sculptures, as mentioned earlier. The Ionic frieze, found in Ionic order temples, was a continuous band of relief sculptures depicting various subjects, including processions, rituals, and scenes from daily life. The Parthenon of the Acropolis had a frieze depicting a Panathenaic procession, which circled the temple.

- Caryatids are sculpted female figures used as architectural supports, often as columns. They were typically depicted wearing draped clothing and standing in a contrapposto stance, which created a sense of movement and grace. Caryatids were commonly found in the Ionic order and were named after the city of Caryae.

- Acroteria are decorative elements placed on the corners of pediments, as well as on the corners of roofs. They were later copied in Gothic architecture, so they can be spotted on buildings from different eras.

Honorific Statues

Honorific statues and their bases are an important aspect of ancient Greek art and culture. They were commissioned to honor, commemorate, and pay tribute to individuals and their achievements. The honored persons could be particularly prominent citizens, military leaders, great athletes, or persons who had made other contributions to society.

The statues were typically placed in public spaces such as in the courtyards of sanctuaries or city squares. They served as a visual representation of honor, prestige, and power. This idealism aligned with the ancient Greek belief in pursuing excellence, beauty, virtue, and celebrating extraordinary athletic skill.

Honorific statues were typically made of marble or bronze. Marble statues were sculpted, and bronze statues were cast using the lost wax technique. Honorific statues were usually larger than life, and the aim was not to portray the exact likeness of the person honored but an idealized version of themselves.

Honorific Statue Bases — Important Clues

Honorific statues stood on bases, which survived in larger numbers than the statues. The pedestals were square or rectangular platforms. The purpose was to stabilize the statues and lift them higher so people could see them better. Occasionally, there were multiple statues placed as a visual ensemble on one platform.

The bases of honorific statues frequently contained inscriptions providing information about the honored person. These included the name of the individual, their achievements, and sometimes the names of the sculptor or the patron who commissioned the statue. Inscriptions could also include dedicatory statements or dedications to gods. The inscriptions offer valuable insights into the personal history of the persons to whom the statues were dedicated and insights into the social dynamics of ancient Greece.

Honorific statue bases can also feature decorative elements such as relief sculptures or architectural embellishments. These decorative elements could include scenes related to the honored person, symbols of their achievements, or mythological motifs. These embellishments enhanced the beauty and significance of these monuments, which are easily overlooked during a museum visit.

Roman Copies — Not Always Replicas

The vast majority of original ancient Greek statues have been lost throughout history. However, the Romans created multiple copies of famous Greek sculptures. The Roman copies covered various subjects and themes, including mythological figures, gods and goddesses, athletes, historical figures, and ordinary individuals. These Roman copies played a crucial role in preserving Greek artistic traditions. Sculpted in marble, they were less likely to be destroyed than the multiple bronze Greek statues that were lost in fires or melted down and used for coin production or even ammunition.

Roman copies of Greek statues were not always exact replicas, but rather, adaptations that reflected the tastes, styles, and artistic conventions of the Roman period. Roman artists often modified the original Greek sculptures to suit contemporary preferences or specific patron demands. The statues were frequently commissioned by Roman emperors, aristocrats, and wealthy patrons who sought to emulate Greek culture and assert their status and power. The choice of specific Greek statues and their placement within public spaces or private collections can reveal the patron’s aspirations, interests, and self-presentation.

The Roman copies of Greek statues also demonstrate the evolution of artistic styles over time. As the Roman Empire progressed, there was a shift towards more naturalistic and realistic representations, departing from the idealized forms of ancient Greek art. The Roman copies often exhibit subtle changes in facial expressions, poses, and drapery that reflect the evolving artistic sensibilities of the Roman period.

Greek Sculpture of the Classical Era

The Classical era of ancient Greek sculpture, which emerged in the 5th century BCE, is renowned for its emphasis on harmony, idealized beauty, and the pursuit of perfect proportions. It represents a pinnacle of artistic achievement and profoundly influenced Western art.

Classical Greek sculpture aimed to depict the human form in its most beautiful and balanced state. Sculptors meticulously studied human anatomy to achieve a sense of realism and proportion in their works. They sought to capture the idealized physical perfection and inner vitality of the human body.

One of the defining characteristics of Classical sculpture is its focus on the concept of contrapposto. This technique involved placing the body’s weight on one leg while the other leg relaxed, resulting in a naturalistic and dynamic pose. Using contrapposto added a sense of movement and liveliness to the sculptures, creating an aesthetically pleasing balance between tension and relaxation.

Classical sculptures also display a sense of calmness and serenity. The facial expressions are serene and composed, conveying a sense of grace and dignity. The attention to detail extended to the rendering of hairstyles, musculature, and drapery, showcasing the sculptors’ technical skill and precision.

The sculptures of the Classical era often depicted gods, goddesses, heroes, and revered individuals. They were primarily made of marble, although bronze was also used. These sculptures adorned temples, public spaces, and private collections, serving as a means of religious devotion, commemoration, and artistic expression.

Prominent sculptors of the Classical era include Phidias , Myron, and Polykleitos, whose works exemplify the ideals and aesthetics of the time. Their sculptures, such as the Parthenon sculptures and the Discus Thrower (Discobolus), are iconic representations of Classical Greek art.

Greek Sculpture of the Hellenistic Era

The Hellenistic era , which spanned from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE to the establishment of the Roman Empire in 31 BCE, witnessed a significant evolution in Greek sculpture. During this period, Greek art experienced a shift in style and subject matter, reflecting the cultural, political, and social changes of the time.

Hellenistic sculpture broke away from the idealized perfection of the Classical period and embraced a more emotional and dramatic approach. Sculptors sought to convey intense emotions, extreme narratives, and new levels of detail in their works. The statues often depicted dynamic poses, exaggerated gestures, and complex compositions that captured movement and energy.

One characteristic feature of Hellenistic sculpture is the exploration of diverse subjects and themes. Artists moved beyond the traditional focus on gods and heroes to depict ordinary people, children, elderly individuals, and animals. This expansion of subject matter allowed a greater range of expressions and emotions to be conveyed, making the sculptures more relatable and humanistic.

The Hellenistic period also saw advancements in sculptural techniques and materials. Sculptors experimented with new materials and explored their potential for realism and expressiveness. They mastered bringing out details, such as skin, hair, and clothing textures, and the rendering of emotions through facial expressions and body language.

Notable sculptors of the Hellenistic era include Lysippus, Praxiteles, and Scopas, whose works demonstrated the innovative and expressive spirit of the time. Their sculptures reflected a fascination with the individual, the human psyche, and the exploration of new aesthetic possibilities.

9 Key Ancient Greek Sculptures

1. nike of samothrace.

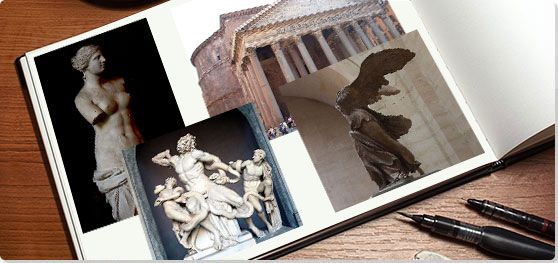

This stunning marble sculpture, dating from the 2nd century BCE, depicts Nike, the Greek goddess of victory. The statue captures the dynamic movement of Nike with her billowing drapery, conveying a sense of triumph and grace. The sculpture is now displayed in the Louvre Museum in Paris.

2. Aphrodite of Knidos

Created by the Greek sculptor Praxiteles in the 4th century BCE, this sculpture depicts the goddess Aphrodite , the embodiment of beauty and love. It is considered one of the first significant depictions of a fully nude female form in Western art. While the original is lost, several Roman copies and adaptations provide insight into its appearance and influence. There are several copies in museums, such as the Louvre, Uffizi Gallery, and the British Museum. Still, the one closest to the original is usually considered to be in the Vatican Museum.

3. Hermes of Praxiteles

Another work attributed to Praxiteles, this sculpture captures the god Hermes holding the infant Dionysus . The delicate forms and the tender interaction between the two figures make this sculpture a masterpiece. The statue was found during the excavations of the temple of Hera in Olympia in 1877 and is on display at the Archaeological Museum of Olympia.

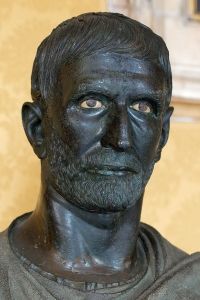

4. The Riace Bronzes

This pair of larger-than-life bronze sculptures, created around 460-450 BCE, depict two ancient Greek warriors. The sculptures are magnificent examples of the sculptor’s ability to display details of the warriors’ anatomical features and facial expressions. The statues were discovered in Riace, Italy, and are housed in the Museo Nazionale della Magna Grecia in Reggio Calabria.

5. Discobolus (Discus Thrower)

The bronze sculpture by Myron was created in the 5th century BCE. The original is now lost, but the sculpture is well-known and studied from several Roman copies. The copies include the Lancellotti Discobolus and the Townley Discobolus (seen in the painting above). The sculptor has used the opportunity to showcase the dynamic pose and prowess of the athlete as he is preparing to throw a discus.

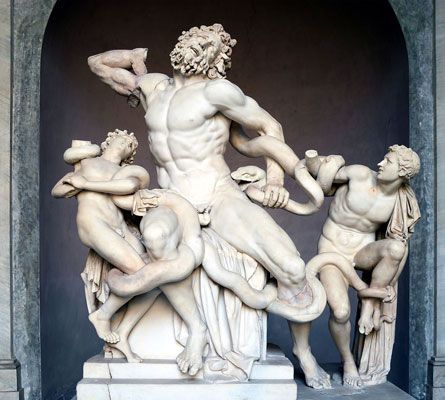

6. Laocoön and His Sons

This Roman copy of a Greek Hellenistic sculpture from the 1st century BCE is an iconic representation of the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being attacked by sea serpents. Laocoon captures intense emotion, dramatic movement, and extreme details, highlighting the mastery of ancient Greek sculpture.

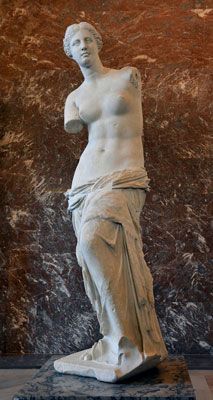

7. Venus de Milo

Also known as the Aphrodite of Milos, this iconic marble sculpture represents the goddess of love and beauty. Despite its missing arms, the statue is renowned for its graceful form, flowing drapery, and idealized depiction of female beauty. Venus de Milo has influenced how artists depict the female body for centuries. On display in the Louvre.

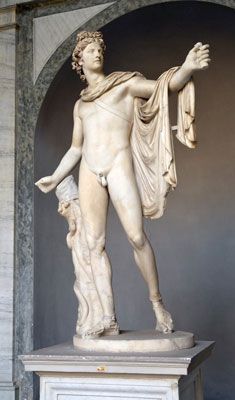

8. Apollo Belvedere

This Roman marble copy is an interesting example of Romans copying the Greek Hellenistic style. The statue’s dynamic pose, idealized physique, and confident expression exemplify the harmonious balance between strength and grace. It was highly regarded during the Renaissance and influenced many subsequent artists.

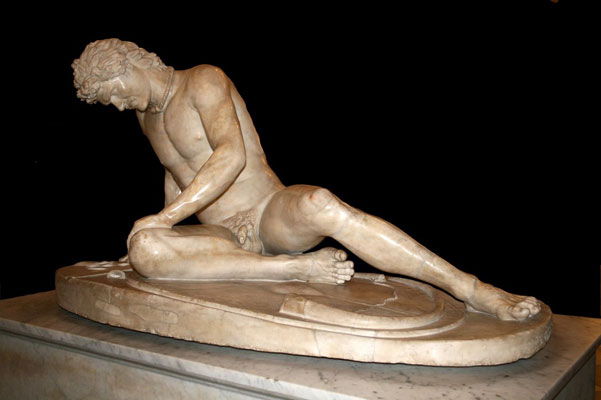

9. Dying Gaul (or “The Dying Galatian”)

This is a Roman marble copy of an original Greek sculpture dating from circa 320 BCE. The work portrays a wounded Gallic warrior in his final moments with clear signs of injury and suffering. The sculpture is recognized for its poignant depiction of the warrior’s pain, vulnerability, and bravery. The Capitoline Museums in Rome house the marble statue.

Timeline of Ancient Greek Art & Sculpture

By Anna Gustafsson M.Sc. Communication & Arts, MA Archaeology Anna is a writer and an archaeologist based in Athens, Greece. She graduated from the University of Athens (NKUA) with an MA in Greek and Eastern Mediterranean archaeology and has an M.Sc. degree in journalism, literature, and art studies. Anna loves to share her passion for history and arts through writing. Her special interests are the Bronze Era in the Eastern Mediterranean area, the visual arts of ancient Greece, and the archaeology of Cyprus. In her spare time, Anna enjoys studying languages, visiting archaeological museums and medieval churches, reading biographies of European royalty, and taking photographs.

Frequently Read Together

4 Ancient Greek Sculptors You Need to Know

6 Spectacular Replicas Of The Parthenon

13 Facts You Did Not Know About the Acropolis of Athens

Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

Summary of Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

Classical Art encompasses the cultures of Greece and Rome and endures as the cornerstone of Western civilization. Including innovations in painting, sculpture, decorative arts, and architecture, Classical Art pursued ideals of beauty, harmony, and proportion, even as those ideals shifted and changed over the centuries. While often employed in propagandistic ways, the human figure and the human experience of space and their relationship with the gods were central to Classical Art. Over the span of almost 1200 years, ideals of human beauty and proportion occupied art's subject. Variations of those ideals were later adopted during the Renaissance in Italy and again during the 18 th and 19 th century Neoclassical trend throughout Europe. Connotations of moral virtue and stability clung to Classical Art, making it attractive to new nations and republics trying to find an aesthetic vocabulary to convey their power, while, later, in the 20 th century it came under attack by modern artists who sought to disrupt and overturn power and traditional ideals.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

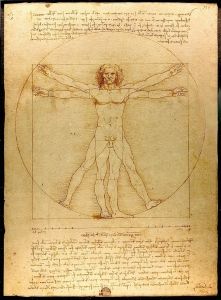

- The idealized human form soon became the noblest subject of art in Greece and was the foundation for a standard of beauty that dominated many centuries of Western art. The Greek ideal of beauty was grounded in a canon of proportions, based on the golden ratio and the ratio of lengths of body parts to each other, which governed the depictions of male and female figures.

- While ideal proportions were paramount, Classical Art strove for ever greater realism in anatomical depictions. This realism also came to encompass emotional and psychological realism that created dramatic tensions and drew in the viewer.

- Greek temple designs started simply and evolved into more complex and ornate structures, but later architects translated the symmetrical design and columned exterior into a host of governmental, educational, and religious buildings over the centuries to convey a sense of order and stability.

- Perhaps a coincidence, but just as increased archaeological digs turned up numerous examples of Greek and Roman art, the field of art history was being developed as a scientific course of study by the likes of Johann Winkelmann. Winkelmann, often considered the father of art history, based his theories of the progression of art on the development of Greek art, which he largely knew only from Roman copies. Since the middle of the 18 th century, art historical and classical tradition have been intimately entwined.

- While Greek and Roman sculpture and ruins are linked with the purity of white marble in the Western mind, most of the works were originally polychrome, painted in multiple, lifelike colors. 18 th century excavations unearthed a number of sculptures with traces of color, but noted art historians dismissed the findings as anomalies. It was only in the late 20 th century that scholars accepted that life-size statues and entire temple friezes were, in fact, brightly painted with numerous colors and decorations, raising many new questions about the assumptions of Western art history and revealing that centuries of classical imitations were not in fact imitations but rather based on nostalgic ideals of the past.

Artworks and Artists of Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

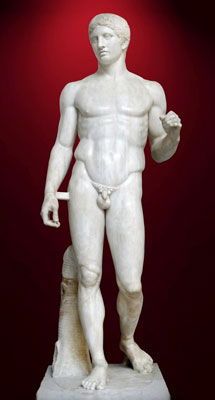

Roman copy 120-50 BCE of original by Polycleitus, Doryphoros (Spear-Bearer) c. 440 BCE

This work depicts a nude muscular warrior, as he steps forward, his head turns slightly to his right, and his left hand would have readied a spear that originally rested upon his left shoulder. The figure's anatomical realism conveys potential movement through a complex interaction of tensed and relaxed muscles. Almost seven feet tall, the monumental work conveys an imposing sense of male heroic beauty that could face whatever may come with dispassionate calm, as shown in the serious but expressionless face. Because marble copies needed additional support, the tree stump was an addition to the bronze original. What is known of the original is based upon the exceptional quality of later copies, including this one. Polycleitus thought this work was synonymous with his Canon, a treatise of sculptural principles, based upon mathematical proportions. Though his treatise has been lost, references to it survived in later accounts, including Galen's, a 2 nd century Greek writer, who wrote that its "Beauty consists in the proportions, not of the elements, but of the parts, that is to say, of finger to finger, and of all the fingers to the palm and the wrist, and of these to the forearm, and of the forearm to the upper arm, and of all the other parts to each other." At the time it was made, the work was widely acclaimed, as Warren G. Moon and Barbara Hughes Fowler write, the Doryphorus ushered in "a new definition of true human greatness...an artistic moral exemplar...tied to no particular place or action, he represents the universal male ideal." This marble copy, found in a gymnasium at Pompeii, became the most admired work of the Roman Republic, as Roman aristocrats commissioned copies.

Marble copy of bronze original - Naples National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy

The Parthenon

Artist: Ictinus and Callicrates

This iconic temple, dedicated to Athena, goddess of wisdom and patron of Athens, stands majestically on top of the Acropolis, a sacred complex overlooking the city. The 17 Doric columns on either side and the eight at each end create both a sense of harmonious proportion and a dynamic visual and horizontal movement. The building exemplifies the Doric order and the rectangular plan of Greek temples, which emphasized a flow of movement and light between the temple's interior and the surrounding space, while the movement of the columns, rising out of the earth, to the entablature that rings the building, draws the eye heavenward to the carved reliefs and statues that, originally, brightly painted, crowned the temple. Ictinus and Callicrates were identified as the architects of the building in ancient sources, while the sculptor Phidias and the statesman Pericles supervised the project. Dedicated in 438 BCE, the Parthenon replaced the earlier temple on the city's holy site that also included a shrine to Erechtheus, the city's mythical founder, a smaller temple of the goddess Athena, and the olive tree that she gave to Athens, all of which were destroyed by the invading Persian Army in 480 BCE. The Persians also killed the priests, priestesses, and citizens who had taken refuge at the site, and, when the new Parthenon was dedicated, following that experience of trauma and desecration, it was a monument to the restoration and continuation of Athenian values and became, as art critic Daniel Mendelsohn wrote, a "dramatization of the political and moral differences between the victims and the perpetrators." As Mendelsohn noted, the Parthenon while taken "as the epitome of Greek architecture...was typical of nothing at all, an anomaly in terms of material, size, and design." It was both the largest temple in Greece and the first built of only marble. While Doric temples commonly had thirteen columns on each side and six in the front, the Parthenon pioneered the octastyle, with eight columns, thus extending the space for sculptural reliefs. Originally the Parthenon Marbles decorated the entablature, as 92 metopes , or rectangular stone panels, depicted mythological battle scenes - of gods fighting giants, Greek warriors fighting Trojans or Amazons, and men battling centaurs - while the pediments contained statues depicting the stories of Athena's life, so that as Mendelsohn wrote, "Merely to walk around the temple was to get a lesson in Greek and Athenian civic history." The temple's interior was equally meant to inspire, as Phidias's colossal statue of Athena Parthenos , or the virgin Athena, dominated the space. Forty feet tall, the statue held a six foot tall gold statue of Victory in her hand. A frieze, carved in relief, lined the surrounding walls, innovatively introducing a decorative feature of Ionic architecture into the Doric order. The 525 foot long frieze has been described by art historian Joan Breton Connelly as "showing 378 human and 245 animal figures... the largest and most detailed revelation of Athenian consciousness we have ... this moving portrayal of noble faces from the distant past, ... the largest, most elaborate narrative tableau the Athenians have left us." The Parthenon's design employed precise mathematical proportions, based upon the golden ratio, but as Mendelsohn noted, "There are almost no straight lines in the building." The columns employ entasis , a swelling at the center of each column, and tilt inward, while the foundation also rises toward the façade, correcting for the optical illusion of sagging and tilting that would have resulted in perfectly straight lines. Aesthetically, though, as Mendelsohn explains, "[T]he slight swelling also conveys the subliminal impression of muscular effort...Arching, leaning, straining, swelling, breathing: the over-all effect...is to give the building a special and slightly unsettling quality of being somehow alive." The building has been highly praised since ancient times as the 1 st century Roman historian Plutarch called it "no less stately in size than exquisite in form," and in the modern era, Le Corbusier called it "the basis for all measurement in art."

Marble - Athens, Greece

Apollo Belvedere, Roman copy, c. 120 - 140 CE of Leochares bronze original c. 350-325 BCE

This nude statue, a little over seven feet tall, depicts Apollo, the Greek god of art and music, as he strides forward, having just shot an arrow from a bow which his extended left hand originally held. Realistic in its anatomical modeling, the work conveys a sense of gravity, both in his form as seen in the musculature of his weight-bearing right leg and in the folds of his chlamys , or robe, falling across his left arm. Contrapposto is employed innovatively to create a sense of complex movement, presenting the statue both frontally and in profile as the god strides forward majestically. While the statue is identified as the god by the headband he wears, reserved for gods or rulers, and his bow and the quiver across his left shoulder, he is also equally a symbol of youthful masculine beauty. The work has also been called the Pythian Apollo, as it was believed to depict Apollo's slaying of the Python, a mythical serpent at Delphi, marking the moment when the site became sacred to the god and home of the famous Delphic Oracle. The marble statue is believed to be a Roman copy of an original bronze from the 4 th century by the Greek sculptor Leochares. The work was discovered in 1489 and became part of the collection of Cardinal Giulano della Rovere who, subsequently, became Pope Julius II, the leading patron of the Italian High Renaissance. He put the work on public display in 1511, and Michelangelo's student, the sculptor Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli, restored the missing parts of the left hand and right arm. Much acclaimed, the work was sketched by Michelangelo, Bandinelli, Goltzius, and Albrecht Dürer who modeled Adam upon Apollo in his engraving Adam and Eve (1504). Marcantonio Raimondi made a copy of the Apollo, and his engraving in the 1530s was widely disseminated throughout Europe; however, the work became most influential in the 1700s as Winckelmann, the pioneering German art historian, wrote, "Of all the works of antiquity that have escaped destruction, the statue of Apollo represents the highest ideal of art." The work became fundamental to the development of Neoclassicism as seen in Antonio Canova's Perseus (1804-1806) modeled after the work. As art critic Jonathan Jones noted, "The work was admired two hundred years ago as an image of the absolute rational clarity of Greek civilisation and the perfect harmony of divine beauty," but in the Romantic era it fell into disfavor as the leading critics, John Ruskin, William Hazlitt, and Walter Pater critiqued it. Still, it has remained popular and frequently reproduced, lending it a cultural currency, as seen in the official seal of the 1972 Apollo XVII moon landing mission.

Marble - Vatican City

The Dying Gaul, Roman marble copy of Greek bronze by Epigonus

This Roman copy of a Greek Hellenistic work depicts a nude and dying man, identified as a Gaul or more specifically a Galatian, a member of a Celtic tribe in Pergamon, a Greek city in Turkey. Sitting on the ground, his left hand grasping his left knee, and his right hand resting upon a broken sword as he holds himself up, he looks down as if contemplating his end. His extended legs and the twist of his torso suggest pain and immanent collapse. The work is realistic and emotionally expressive, as the tension between tensed and relaxed muscles conveys his struggle to fight off death. A pensive and somber feeling dominates the work, making it an intense reflection on defeat and mortality, while the idealization of his physical beauty suggests a heroic death. The statue was discovered sometime in the early 1600s at the Villa Ludovisi, the country residence of a wealthy and powerful Italian family, and was originally believed to depict a Roman gladiator. The work was popular and viewing it became a necessary part of the Grand Tour undertaken by young aristocrats in the 18 th and 19 th centuries. The British Romantic poet, Lord Byron whose famous poem Childe Harold's Pilgrimage (1812) was written following his Grand Tour, wrote, "I see before me the gladiator lie/ He leans upon his hand - his manly brow/ Consents to death, but conquers agony." Its popularity led to a proliferation of marble and plaster copies across Europe. In the 19 th century, scholars identified the subject as a Gaul, due to his hairstyle and the torque he wears on his neck, and Epigonus, a court appointed sculptor of Pergamon, as the original artist. The original was part of a complex sculpture group to celebrate Pergamon's victory over the Gauls and exemplifies what was called the "Pergamene Style," which as contemporary art critic Jerry Saltz noted, "emphasized emotional appeal and almost Baroque volatility. Nothing defines that style quite as clearly as the Dying Gaul , who is both tragic and sensual, firing both our desire and our sense of compassion."

Marble - Capitoline Museums, Rome, Italy

Winged Victory of Samothrace

This monumental work, depicting Nike, the goddess of victory, and created in honor of a naval victory, emphasizes dynamic movement, as the goddess surges forward, swept by the wind, her wings unfurled behind her. As art historian H.W. Jansen wrote, "This invisible force of on-rushing air here becomes a tangible reality; it not only balances the forward movement of the figure but also shapes every fold of the wonderfully animated drapery. As a result, there is an active relationship - indeed, and interdependence - between the statue and the space that envelops it, such as we have never seen before." Over 18 feet tall, the Hellenistic statue stands on a pedestal, placed upon a base that resembles the prow of a ship. Most scholars believe the work was originally placed at the Sanctuary of the Greek Gods, a temple complex overlooking the harbor on the island of Samothrace. Charles Champoiseau, a French envoy, discovered the fragmented statue in 1863 and sent it to Paris where it was reassembled and placed in the Louvre, famously dominating the view up the grand staircase. The work influenced a number of modern artists and movements, as Umberto Boccioni's Futuristic work Unique Forms of Continuity in Space (1913) references the statue, and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti also referenced it in his Futurist Manifesto (1903). The American sculptors Samuel Murray and Augustus Saint-Gaudens created Nike-like figures, as seen in Saint Gauden's Sherman Memorial (1903) and the statue was a favorite work of the architect Frank Lloyd Wright, who included reproductions of it in a number of his residential designs. Yves Klein painted a number of plaster copies, painted in his International Klein Blue and using a resin he named Victoire de Samatrace , and more recently, Banksy's CCTV Angel (2006) repurposed the figure.

Parian Marble - Louvre Museum, Paris

Venus de Milo

Artist: Alexandros of Antioch

Believed to portray Venus, the goddess of love, this six-and-a-half-foot statue creates dynamic visual movement with its accentuated s-curve, emphasizing the curve of the torso and hip, as the lower part of her body is draped in the realistic folds of her falling robe. The dramatic contrapposto , her left knee raised as if lifting her foot off the ground, further emphasizes her movement, as she turns toward the viewer. The work was originally attributed to Praxiteles but is now generally credited to Alexandros of Antioch. Scholarly dispute continues about the identity of its subject; traditionally identified as Venus, some scholars believe the work actually portrays Amphitrite, a sea goddess, worshipped on the island of Milo where the sculpture was found in 1820, and some contemporary scholars have suggested the figure may in fact portray a prostitute. The statue was made from several pieces of marble, two blocks used for the body, while other parts, including the legs and left arm, were sculpted individually and then attached. When excavated in 1820, part of an arm and a fragmented hand holding a round orb were discovered with the statue, which stood upon a stone plinth. At the time, the fragments were discarded, due to their 'rougher' finish, and later so was the plinth. It's believed that, originally, the statue was brightly painted and adorned with expensive jewelry. During his Italian campaign Napoleon Bonaparte took the Medici Venus (1 st century BCE), then the most renowned classical female nude, to France and installed it in the Louvre. But in 1815 the French returned the Medici Venus and bought the Venus de Milo , which they promoted both as the finest classical work and a model of feminine grace and beauty. More than any other classical sculpture, this iconic nude has greatly influenced both modern art and culture, due to its compelling ideal of feminine beauty and its beguiling mystery. As art critic Jonathan Jones writes, "The Venus de Milo is an accidental surrealist masterpiece. Her lack of arms makes her strange and dreamlike. She is perfect but imperfect, beautiful but broken - the body as a ruin. That sense of enigmatic incompleteness has transformed an ancient work of art into a modern one." Salvador Dalí's Venus de Milo with Drawers (1936) copied the work but inserted pull drawers with pink pompom handles into the torso. As Jones noted, the Venus de Milo has retained its contemporary artistic relevance because it "entered European culture in the 19th century just as artists and writers were rejecting the perfect and timeless." As a result, the work haunts the modern imagination, referenced in literature, films, and television episodes and used in any number of advertisements, while its impact on cultural concepts of feminine beauty can be seen in the American Society of Plastic Surgeons' use of the figure on its seal in 1930.

Marble - Louvre Museum, Paris

Laocoön and His Sons

Artist: Agesandro, Athendoros, and Polydoros

This famous work depicts the doomed struggle of Laocoön, and his two sons Antiphantes and Thymbraeus caught in the coils of two giant poisonous sea serpents, one of them biting Laocoön's hip. His hand grasps the snake's neck as he tries to fend it off. On the left, the youngest boy, dying from the poison, has collapsed, his legs caught in the coils that lift him off the ground. The central figure is the father, whose powerful muscular form twists upward and backward, his despairing and contorted gaze turned heavenward, as his son on the right turns to look pleadingly at him. Drawing upon the story of the Trojan war, the work is thought to dramatically depict the moment when Laocoön, a priest of Troy who warned the Trojans against taking the Greek wooden horse into the city, was attacked, along with his two sons, by the serpents sent by the gods to silence him. As a result the frightened Trojans, fearing the gods' punishment, took in the wooden horse containing the Greek soldiers, who, hidden within it, came out at night to open the gates for the Greek army, leading to the fall of Troy. Art historian Nigel Spivey has called the work "the prototypical icon of human agony," and its dynamic sense of drama and its use of slightly unrealistic scale to emphasize paradoxically the father's power and helplessness made it innovative and a masterwork of the Hellenistic style. In 1506 the work was discovered during excavations of Rome and immediately drew the attention of Pope Julius II who sent Michelangelo to oversee the excavation. Its identification drew upon the ancient accounts of Pliny the Elder, a Roman writer, who described the work as located in the emperor Titus's palace and attributed it to the Rhodes sculptors Agesander, Athenodoros and Polydorus. The work greatly influenced Michelangelo, including some of his figures in the Sistine Chapel ceiling and his later sculpture. Raphael depicted Homer with Laocoon's face in his Parnassus , and Titian drew upon the work for his Averoldi Altarpiece (1520-24), as did Rubens for his Descent from the Cross . (1612-14). William Blake also referenced the sculpture, though within his own belief that imitations of Classical Art destroyed the creative imagination. The work informed a number of ongoing debates, as to whether sculpture or painting were more primary, and has played a role in modern discourses, as seen in Irving Babbit's (1910) The New Laokoon: An Essay on the Confusion of the Arts (1910) and Clement Greenberg's Towards a Newer Laocoön (1940), where he argued for abstract art as the new, equivalent, ideal. The Henry Moore Institute held a 2007 exhibition with this title while showing modern works influenced by the statue, and contemporary artist Sanford Biggers has referenced the work within his contemporary installation pieces.

Augustus of Prima Porta

This statue depicts Augustus, the first Emperor of Rome, in military uniform, his right arm raised in a gesture of leadership, addressing the military and populace of Rome. His contrapposto pose, the muscular modeling of his breastplate, and his dispassionate expression are informed by Polycleitus's Doryphorus , as the emperor is presented as the new model of the universal male ideal. His breastplate is intricately carved with scenes and figures - including the sun, sky, and earth gods, a diplomatic victory over the Parthians, and female figures representing conquered countries - that establish him as a military leader, founder of the Pax Romana, and heir of Rome's mythological and historical traditions. Tugging at his right, a small cupid rides a dolphin that symbolizes Augustus's victory at the 31 BCE Battle of Actium over Mark Antony and Cleopatra, which made him sole ruler. At the same time, the cupid, representing Eros, a son of the goddess Venus, refers to Julius Caesar's claim that he was descended from the goddess. As Augustus was Caesar's grand-nephew and adopted heir, he establishes his divine patrimony and connects it to the legendary founding of Rome by Aeneas, the only mortal son of Venus and the only surviving Trojan prince. The statue is barefoot, a trope associated with portrayals of divinity, and as art critic Alastair Sooke noted, the work, "is not simply a portrait of Rome's first emperor...it is also a vision of a god." Emerging victorious from a civil war that followed the assassination of Julius Caesar, Augustus launched a notable building campaign, saying later, "I found Rome a city of bricks and left it a city of marble." His image became a powerful propaganda tool, as art critic Roderick Conway Morris wrote, "He projected his image through art and architecture and...this gave birth to a new classical Roman style, which would long outlive the first emperor and influence imperial and dynastic art over the next two millennia." As a result, more images of Augustus in statues, busts, coins, and cameos, all depicting him as this ever youthful and virile leader, survive than of any other Roman emperor. While Romans were known for their exacting portraiture, Augustus insisted on the idealized, youthful image throughout his reign to distance himself from any unrest in the empire. The work was rediscovered following its excavations in 1863 at Prima Porta, a villa which belonged to Augustus's wife, and as Sooke wrote, "Since its rediscovery, this charismatic work of art has become a symbol of ancient Rome's peculiar blend of refinement and ruthless military might." As a result, it has had a somewhat notorious afterlife, as when the Italian dictator Mussolini held an art exhibition in 1937 dedicated to Augustus and included this work in order to identify Fascist Italy with a new Roman Empire.

The circular temple faces the street with a monumental portico, employing eight Corinthian columns at the front with double rows of four columns behind, to create an imposing entrance. The façade, evoking the octastyle of the Athenian Parthenon, also emphasized that Rome was the heir of the classical tradition. The large granite columns rise to an entablature with an inscription reading "Marcus Agrippa, son of Lucius, made [this] when consul for the third time." Though Agrippa's temple, built during the reign of the Emperor Augustus (27 BCE-14 CE), burned down, the Emperor Hadrian retained the inscription when he rebuilt the temple. The building's innovative and distinctive feature was its concrete dome; with a height and diameter of 142 feet, still, the world's largest dome made of unreinforced concrete. The interior was equally innovative, as the dome rose above a circular interior chamber, illuminated by an oculus opening to the sky in the center of the coffered dome, creating a sense of both an imperial and divine space. "Pantheon" means "relating to the gods," and scholars continue to debate whether this meant the temple was dedicated to all the gods or followed tradition in being dedicated to a specific god. Specific dedications to single gods were considered more provident since, if any mishap struck, the people would know which god had been offended and could offer sacrifices. When Agrippa first built the temple, it was part of the Agrippa complex (29-19 BCE) that also included the Baths of Agrippa and the Basilica of Neptune, and it is thought that the façade is what remains of his original structure. The building is one of the best preserved from the Imperial Roman era, as it was turned into a Christian church in the 7 th century, though it has also been altered, and many of the relief sculptures of gilded bronze were melted down. The work influenced Filippo Brunelleschi's dome of Florence Cathedral in 1436, a radical design that transformed architecture and informed the development of the Italian Renaissance. The Pantheon also informed the Baroque movement, as seen in Bernini's Santa Maria Assunta (1664), and the Neoclassical movement, as seen in Thomas Jefferson's Rotunda (1817-26) on the grounds of the University of Virginia.

Marble, concrete, bronze, stone - Rome, Italy

Beginnings of Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

Mycenaean influences 1600-1100 bce.

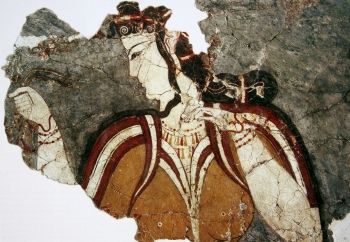

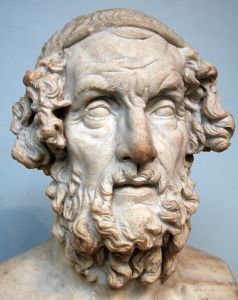

Considered the first Greeks, the Mycenaeans had a lasting influence on later Greek art, architecture, and literature. A bronze age civilization that extended through modern day southern Greece as well as coastal regions of modern day Turkey, Italy, and Syria, Mycenaea was an elite warrior society dominated by palace states. Divided into three classes - the king's attendants, the common people, and slaves - each palace state was ruled by a king with military, political, and religious authority. The society valorized heroic warriors and made offerings to a pantheon of gods. In later Greek literature, including Homer's The Iliad and The Odyssey , the exploits of these warriors and gods engaged in the Trojan War had become legendary and, in fact, appropriated by later Greeks as their founding myths.

Agriculture and trade were the economic engines driving Mycenaean expansion, and both activities were enhanced by the engineering genius of the Mycenaeans, as they constructed harbors, dams, aqueducts, drainage systems, bridges, and an extended network of roads that remained unrivaled until the Roman era. Innovative architects, they developed Cyclopean masonry, using large boulders, fit together without mortar, to create massive fortifications. The name for Cyclopean stonework came from the later Greeks, who believed that only the Cyclops, fierce one-eyed giants of myth and legend, could have lifted the stones. To lighten the heavy load above gates and doorways, the Mycenaeans also invented the relieving triangle, a triangular space above the lintel that was left open or filled with lighter materials.

The Mycenaeans first developed the acropolis, a fortress or citadel, built on a hill that characterized later Greek cities. The king's palace, centered on a megaron , or circular throne room with four columns, was decorated with vividly colored frescoes of marine life, battle, processions, hunting, and gods and goddesses.

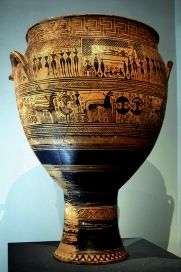

Scholars still debate how the Mycenaean civilization declined, and theories include invasions, internal conflict, and natural disasters. The era was followed by what has been called the Greek Dark Ages, though it is also known as the Homeric Age and the Geometric period. The term Homeric Age refers to Homer whose poems narrated the Trojan War and its aftermath. The term Geometric period refers to the era's style of vase painting, which primarily employed geometric motifs and patterns.

Greek Archaic Period 776-480 BCE

The Archaic Period began in 776 BCE with the establishment of the Olympic Games. Greeks believed that the athletic games, which emphasized human achievement, set them apart from "barbarian," non-Greek peoples. The Greeks' valorization of the Mycenaean era as a heroic golden age led them to idealize male athletes, and the male figure became dominant subjects of Greek art. The Greeks felt that the male nude showed not only the perfection and beauty of the body but also the nobility of character.

The Greeks developed a political and social structure based upon the polis, or city-state. While Argus was a leading center of trade in the early part of the era, Sparta, a city state that emphasized military prowess, grew to be the most powerful. Athens became the pioneering force in the art, culture, science, and philosophy that became the basis of Western civilization. Though the era was dominated by the rule of tyrants, Solon, a philosopher king, became the ruler of Athens around 594 BCE and established notable reforms. He created the Council of Four Hundred, a body that could question and challenge the king, ended the practice of putting people into slavery for their debts, and established a ruling class based on wealth rather than descent. Extensive sea-faring trade drove the Greek economy, and Athens, along with other city-states, began establishing trading posts and settlements throughout the Mediterranean. As a result of these forays, Greek cultural values spread to other cultures, including the Etruscans in southern Italy, influencing and co-mingling with them.

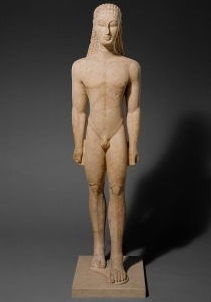

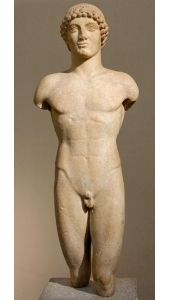

Figurative sculpture was the greatest artistic innovation of the Archaic period as it emphasized realistic, though idealized, figures. Influenced by Egyptian sculpture, the Greeks transformed the frontal poses of pharaohs and other notables into works known as kouros (young men) and kore (young women), life-sized sculptures that were first developed in the Cyclades islands in the 7 th century BCE. During the late Archaic period, individual sculptors, including Antenor, Kritios, and Nesiotes, were celebrated, and their names preserved for posterity.

The late Archaic period was marked by new reforms, as the Athenian lawgiver Cleisthenes established new policies in 508BC that led to him being dubbed "the father of democracy." To celebrate the end of the rule of tyrants, he commissioned the sculptore Antenor to complete a bronze statue, The Tyrannicides (510 BCE), depicting Harmonides and Aristogeion, who had assassinated Hipparchos, the brother of the tyrant Hippias, in 514 BCE. Though the two were executed for the crime, they became symbols of the movement toward democracy that led to the expulsion of Hippias four years later and were considered to be the only contemporary Greeks worthy enough to be granted immortality in art. The commission of Antenor's work was the first public funded art commission, and the subject was so resonant that, when Antenor's work was taken during the 483 BCE Persian invasion, Kritios was commissioned to create a replacement. Kritios's The Tyrannicides (c. 477 BCE) developed what has been called the severe style, or the Early Classical style, as he depicted realistic movement and individual characterization, which had a great influence on subsequent sculpture.

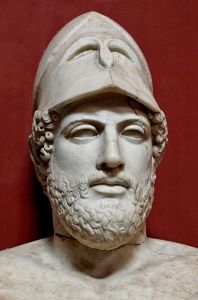

Classical Greece 480-323 BCE

Classical Greece, also known as the Golden Age, became fundamental both to the later Roman Empire and western civilization, in philosophy, politics, literature, science, art, and architecture. The great Greek historian of the era Thucydides, called the general and populist statesman Pericles "Athens's first citizen." Equal rights for citizens (which only meant adult Greek males), democracy, freedom of speech, and a society ruled by an assembly of citizens defined Greek government. Pericles launched the rebuilding of the Parthenon (447-432 BCE) in Athens, a project overseen by his friend, the sculptor Phidias, and established Athens as the most powerful city state, expanding its influence throughout the Mediterranean region.

The Classical era also saw the establishment of Western philosophy in the teachings and writings of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. The philosophy of Socrates survived through Plato's written accounts of his teacher's dialogues, and Plato went on to found the Academy in Athens around 387 BCE, an early prototype of all later academies and universities. Many leaders studied at the Academy, including most notably Aristotle, and it became a leading force known throughout the world for the importance of scientific and philosophical inquiry based upon the belief in reason and knowledge. While their philosophies diverged in key respects, Plato and Aristotle concurred in seeing art as an imitation of nature, aspiring to the beautiful.

Additionally, the emphasis on individuality resulted in a more personalized art, and individual artists, including Phidias, Praxiteles, and Myron, became celebrated. Funerary sculpture began depicting real people (instead of idealized types) with emotional expression, while at the same time, bronze works idealized the human form, particularly the male nude. Praxiteles, though, pioneered the female nude in his Aphrodite of Knidos (4th century BCE), a work that has been referenced time and time again in the ensuing centuries.

Hellenistic Greek 323-31 BCE

The death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period. Having amassed a vast empire beyond Greece that included parts of Asia, North Africa, Europe and not having named a successor instigated a war between Alexander's generals for control of his empire, and local leaders jockeyed to regain control of their regions. Eventually, three generals agreed to a power-sharing relationship and carved the Greek empire into three different regions. While the mainland Greek cultural influence declined, Alexandria in Egypt and Antioch in modern day Syria became important centers of Hellenistic culture. Many Greeks emigrated to other parts of the fractured empire, "Hellenizing the world," as art historian John Griffiths Pedley wrote.

Despite the splintering of the empire, great wealth led to royal patronage of the arts, particularly in sculpture, painting, and architecture. Alexander the Great's official sculptor had been Lysippus who, working in bronze after Alexander's death, created works that marked a transition from the Classical to the Hellenistic style. Some of the most famous works of Greek art, including the Venus de Milo (130-100 BCE) and the Winged Victory of Samothrace (200-190 BCE) were created in the era.

Architecture turned toward urban planning, as cities created complex parks and theaters for leisure. Temples took on colossal proportions, and the architectural style employed the Corinthian order, the most decorative of Classical orders. Pergamon became a vital center of culture, known for its colossal complexes, as exemplified by in the Pergamon Altar (c. 166-156 BCE) with its extensive and dramatic friezes. During the Hellenistic period, the Greeks gradually fell to the rule of the Roman Republic, as Rome conquered Macedonia in the Battle of Corinth in 146 BCE. Upon his death in 133 BCE, King Attalus III left the Kingdom of Pergamon to the Romans. Though Greek rebellions followed, they were crushed in the following century.

Roman Republic 509 BCE - 26 CE

Rome began as a city-state ruled by kings, who were elected by the nobleman of the Roman Senate, and then became a Republic when Lucius Tarquinii Superbus, the last king, was expelled in 509BC. Because his son had raped Lucretia, a married noblewoman, who took her own life, Tarquinii was deposed by her husband, her father, and Lucius Junius Brutus, Tarquinii's nephew. The story became both part of Roman history and a subject depicted in art throughout the following centuries.

With the kingship abolished, the Republic was established with a new system of government led by two consuls. As the patricians, the upper class who governed Rome, were often in conflict with the plebeians, or common people, an emphasis was put upon city planning, including apartment buildings called insulae and public entertainments that featured gladiator fights and horse races to keep the people happy, a type of rule that the Roman poet Juvenal described as "bread and circuses." Cities were planned on a grid system, while architecture and engineering projects were transformed by the development of concrete in the 3 rd century. Rome was primarily a military state, frequently at war with neighboring tribes in Italy at the beginning. Various military campaigns resulted in the conquest and destruction of Carthage, a North African kingdom, in three Punic wars, the conquest of the Macedonia and its eastern territories, and Greece in the 2 nd century BCE resulted in geographically expansive empire.

Roman culture adopted many of the myths, gods, and heroic stories of the Greeks, while emphasizing their own tradition of the mas majorum , the way of the ancestors, a kind of contractual obligation with the gods and the founding fathers of Rome. Greek works, taken as spoils of war, were extensively copied and displayed in Roman homes and became a primary influence upon Roman art and architecture. The rise of Julius Caesar, following his triumph over the Gauls in northern Europe, marked the end of the Republic, as he was assassinated in 44 BCE by a number of senators in order to prevent him being declared emperor. His death plunged the Republic into a civil war, fought by his former general Marc Antony allied with Cleopatra, queen of Egypt, against the forces of Pompeius and the forces of Caesar's great nephew and heir, Octavian.

Imperial Rome 27 BCE - 393 CE

While the assassins may have staved off the crowning of Caesar as emperor, eventually an emperor was named. Imperial Rome begins with the crowning of Octavian as the first emperor, who came to be known as Augustus. In his almost forty-five year reign, he transformed the city, establishing public services, including the first police force, fire fighting force, postal system, and municipal offices, while creating revenue and taxation systems that were the blueprint for the Empire in the following centuries. He also launched a new building program that included temples and notable public buildings, and he transformed the arts, commissioning works like the Augustus of Prima Porta (1 st century CE) that depicted him as an ideal leader in a classical style that harkened back to Greece. He also commissioned The Aeneid (29-19 BCE) an epic poem by the poet Virgil that defined Rome and became a canonical work of Western literature. The poem described the mythical founding of Rome, relating the journey of Aeneas, the son of Venus and Prince of Troy, who fled the Sack of Troy to arrive in Italy, where, fighting and defeating the Etruscan rulers, he founded Rome.

The Imperial era was defined by the monumental grandeur of its architecture and its luxurious lifestyle, as wealthy residences were lavishly decorated with colorful frescoes, and the upper class, throughout the Empire, commissioned portraits. The Empire ended with the Sack of Rome in 393 CE, though by that time, its power had already declined, due to increasingly capricious emperors, internal conflict, and rebellion in its provinces. The conversion of Emperor Constantine to Christianity and the moving of the imperial capital from Rome to Constantinople in 313 CE established the rising power of the Byzantine Empire.

Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

The golden ratio.

The Greeks believed that truth and beauty were closely associated, and noted philosophers understood beauty in largely mathematical terms. Socrates said, "Measure and proportion manifest themselves in all areas of beauty and virtue," and Aristotle advocated for the golden mean, or the middle way, that led to a virtuous and heroic life by avoiding extremes. For the Greeks, beauty derived from the combination of symmetry, harmony, and proportion. The golden ratio, a concept based on the proportions between two quantities, as defined by the mathematicians Pythagoras (6 th century BCE) and Euclid (323-283 BCE), was thought to be the most beautiful proportion. The golden ratio indicates that the ratio between two quantities is the same as the ratio between the larger of the two and their sum. The Parthenon (447-432 BCE) employed the golden ratio in its design and was fêted as the most perfect building imaginable. Because the artist Phidias oversaw the building of the temple, the golden ratio became commonly known by the Greek letter phi , in honor of Phidias. The golden ratio had a noted impact on later artists and architects, influencing the Roman architect Vitruvius, whose principles informed the Renaissance, as seen in the work and theory of Leon Battista Alberti , and modern architects, including Le Corbusier .

Greek Architecture

Best known for its temples, using a rectangular design framed by colonnades open on all sides, Greek architecture emphasized formal unity. The building became a sculptural presence on a high hill, as art historian Nikolaus Pevsner wrote, "The plastic shape of the [Greek] temple ... placed before us with a physical presence more intense, more alive than that of any later building."

The Greeks developed the three orders - the Doric, the Ionic, and the Corinthian - which became part of the fundamental architectural vocabulary of Rome and subsequently much of Europe and the United States. Developed in different parts of Greece and at different times, the distinction between the orders is primarily based upon the differences between the columns themselves, their capitals, and the entablature above them. The Doric order is the simplest, using smooth or fluted columns with circular capitals, while the entablature features add a more complex decorative element above the simple columns. The Ionic column uses volutes , from the Latin word for scroll, as a decorative element at the top of the capital, and the entablature is designed so that a narrative frieze extends the length of the building. The late Classical Corinthian order, named for the Greek city of Corinth, is the most decorative, using elaborately carved capitals with an acanthus leaf motif.

Originally, Greek temples were often built with wood, using a kind of post and beam construction, though stone and marble were increasingly employed. The first temple to be built entirely of marble was the Parthenon (447-432 BCE). Greek architecture also pioneered the amphitheater, the agora , or public square surrounded by a colonnade, and the stadium.The Romans appropriated these architectural structures, creating monumental amphitheaters and revisioning the agora as the Roman forum, an extensive public square that featured hundreds of marble columns.

Roman Architecture and Engineering

Roman architecture was so innovative that it has been called the Roman Architectural Revolution, or the Concrete Revolution, based on its invention of concrete in the 3 rd century. The technological development meant that the form of a structure was no longer constrained by the limitations of brick and masonry and led to the innovative employment of the arch, the barrel vault, the groin vault, and the dome. These new innovations ushered in an age of monumental architecture, as seen in the Colosseum and civil engineering projects, including aqueducts, apartment buildings, and bridges. The Romans, as architectural historian D.S. Robertson wrote, "were the first builders in Europe, perhaps the first in the world, fully to appreciate the advantages of the arch, the vault and the dome." They pioneered the segmental arch - essentially a flattened arch, used in bridges and private residences - the extended arch, and the triumphal arch, which celebrated the emperors' great victories. But it was their employment of the dome that had the most significant impact on Western civilization. Though influenced by the Etruscans, particularly in their use of arches and hydraulic techniques, and the Greeks, Romans still used columns, porticos, and entablatures even when technological innovations no longer required them structurally.

Though little is known of his life beyond his work as a military engineer for Emperor Augustus, Vitruvius was the most noted Roman architect and engineer, and his De architectura ( On Architecture ) (30-15 BCE), known as Ten Books on Architecture , became a canonical work of subsequent architectural theory and practice. His treatise was dedicated to Emperor Augustus, his patron, and was meant to be a guide for all manner of building projects. His work described town planning, residential, public, and religious building, as well as building materials, water supplies and aqueducts, and Roman machinery, such as hoists, cranes, and siege machines. As he wrote, "Architecture is a science arising out of many other sciences, and adorned with much and varied learning." His belief that a structure should have the qualities of stability, unity, and beauty became known as the Vitruvian Triad. He saw architecture imitating nature in its proportionality and ascribed this proportionality to the human form as well, famously expressed later in Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian Man (1490).

Vase Painting

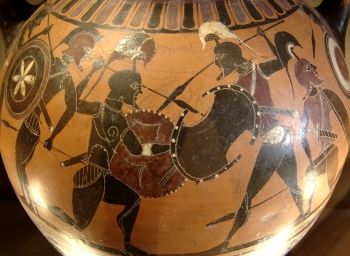

Vase painting was a noted element of Greek art and provides the best example of how Greek painting focused primarily on portraying the human form and evolved toward increased realism. The earliest style was geometric, employing patterns influenced by Mycenaean art, but quickly turned to the human figure, similarly stylized. An "Orientalizing" period followed, as Eastern motifs, including the sphinx, were adopted to be followed by a black figure style, named for its color scheme, that used more accurate detail and figurative modeling.

The Classical era developed the red figure style of vase painting, which created the figures by strongly outlining them against a black background and allowed for their details to be painted rather than incised into the clay. As a result, variations of color and of line thickness allowed for more curving and rounded shapes than were present in the Geometric style of vases.

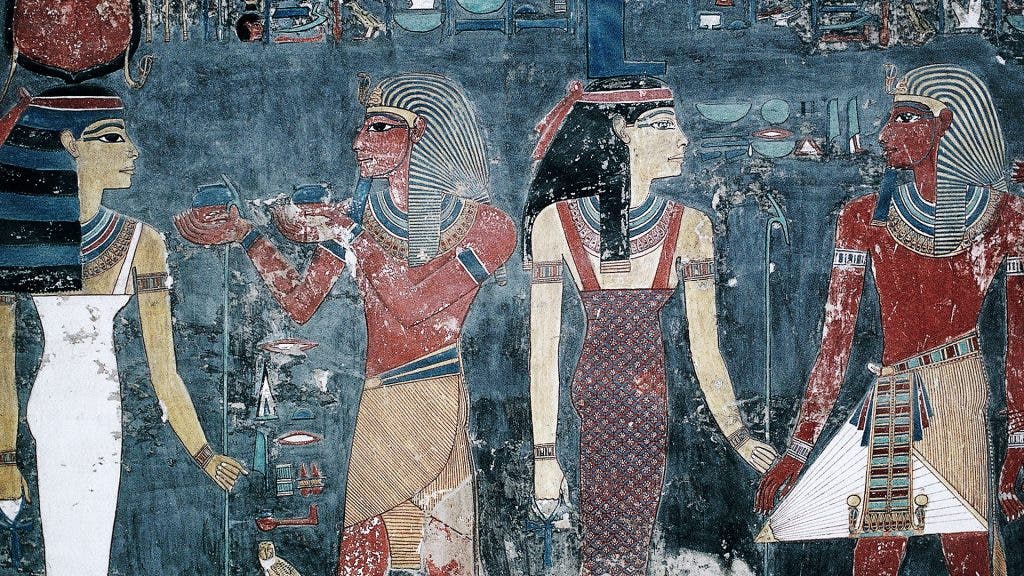

Greek and Roman Painting

While Classical Art is noted primarily for its sculpture and architecture, Greek and Roman artists made innovations in both fresco and panel painting. Most of what is known of Greek painting is ascertained primarily from painting on pottery and from Etruscan and later Roman murals, which are known to have been influenced by Greek artists and, sometimes, painted by them, as the Greeks established settlements in Southern Italy where they introduced their art. Hades Abducting Persephone (4 th century BCE) in the Vergina tombs in Macedonia is a rare example of a Classical era mural painting and shows an increased realism that parallels their experiments in sculpture.

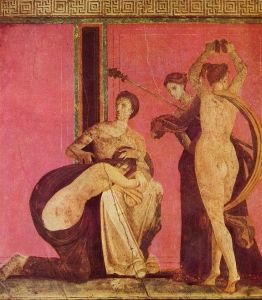

Roman panel and fresco paintings survived in greater number than Greek paintings. The 1748 excavation of Pompeii, a Roman city that was buried almost instantaneously in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE, led to the groundbreaking discovery of many relatively well-preserved frescos in noted Roman residences, including the House of the Vettii, the Villa of Mysteries, and the House of the Tragic Poet. Fresco paintings brought a sense of light, space, and color into interiors that, lacking windows, were often dark and cramped. Preferred subjects included mythological accounts, tales from the Trojan war, historical accounts, religious rituals, erotic scenes, landscapes, and still lifes. Additionally, walls were sometimes painted to resemble brightly colored marble or alabaster panels, enhanced by illusionary beams or cornices.

Greek Sculpture

Influenced by the Egyptians, the Greeks in the Archaic period began making life-sized sculptures, but rather than portraying pharaohs or gods, Greek sculpture largely consisted of kouroi , of which there were three types - the nude young man, the dressed and standing young woman, and a seated woman. Famous for their smiling expressions, dubbed the "Archaic smile", the sculptures were used as funerary monuments, public memorials, and votive statues. They represented an ideal type rather than a particular individual and emphasized realistic anatomy and human movement, as New York Times art critic Alastair Macaulay wrote, "The kouros is timeless; he might be about to breathe, move, speak."

In the late Archaic period a few sculptors like Kritios became known and celebrated, a trend which became even more predominant during the Classical era, as Phidias, Polycleitus, Myron, Scopas, Praxiteles, and Lysippus became legendary. Myron's Discobolos , or "discus thrower," (460-450 BCE) was credited as being the first work to capture a moment of harmony and balance. Increasingly, artists focused their attention on a mathematical system of proportions that Polycleitus described in his Canon of Polycleitus and emphasized symmetry as a combination of balance and rhythm. Polycleitus created Doryphoros ( Spear-Bearer ) (c.440 BCE) to illustrate his theory that "perfection comes about little by little through many numbers."

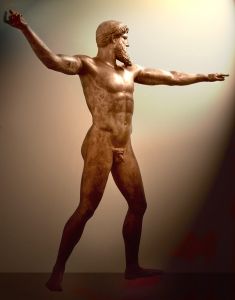

Most of the original Greek bronzes have been lost, as the value of the material led to their frequently being melted down and reused, particularly in the early Christian era where they were viewed as pagan idols. A few notable examples have survived, such as the Charioteer of Delphi (478 or 474 BCE), which was found in 1896 in a temple buried in a rockslide. Other works, including the Raice bronzes (460-450 BCE) and the Artemison Bronze (c.460) were retrieved from the sea. The earliest Greek bronzes were sphyrelaton , or hammered sheets, attached together with rivets; however, by the late Archaic period, around 500 BCE, the Greeks began employing the lost-wax method. To make large-scale sculptures, the works were cast in various pieces and then welded together, with copper inlaid to create the eyes, teeth, lips, fingernails, and nipples to give the statue a lifelike appearance.

Along with sculpture in the round, the Greeks employed relief sculpture to decorate the entablatures of temples with extensive friezes that often depicted mythological and legendary battles and mythological scenes. Created by Phidias, the Parthenon Marbles (c. 447-438 BCE), also known as the Elgin Marbles, are the most famous examples. Created on metopes , or panels, the relief sculptures decorated the frieze lining the interior chamber of the temple and, renowned for their realism and dynamic movement, had a noted influence upon later artists, including Auguste Rodin.

The Greeks also made colossal chryselephantine, or ivory and gold statues, beginning in the Archaic period. Phidias was acclaimed for both his Athena Parthenos (447 BCE), a nearly forty foot tall statue that resided in the Parthenon on the Acropolis, and his Statue of Zeus at Olympia (435 BCE) that was forty three feet tall and considered one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Both statues used a wooden structure with gold panels and ivory limbs attached in a kind of modular construction. They were not only symbols of the gods but also symbols of Greek wealth and power. Both works were destroyed, but small copies of Athena exist, and representations on coins and descriptions in Greek texts survive.

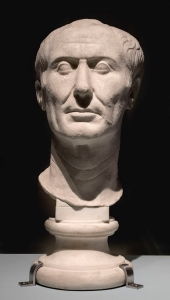

Roman Portraiture

Many Roman sculptures were copies of Greek originals, but their own contribution to Classical sculpture came in the form of portraiture. Emphasizing a realistic approach, the Romans felt that depicting notable men as they were, warts and all, was a sign of character. In contrast, in Imperial Rome, portraiture turned to idealistic treatments, as emperors, beginning with Augustus, wanted to create a political image, showing them as heirs of both classical Greece and Roman history. As a result, a Greco-Roman style developed in sculptural relief as seen in the Augustan Ara Pacis (13 BCE).

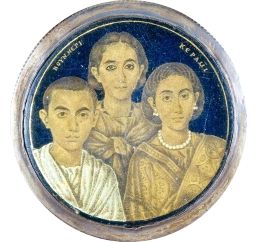

The Romans also revived a method of Greek glass painting to use for portraiture. Most of the images were the size of medallions or roundels cut out of a drinking vessel. Wealthy Romans would have drinking cups made with a gold glass portrait of themselves and, following the owner's death, the portrait would be cut out in a circular shape and cemented into the catacomb walls as a tomb marker.

Some of the most famous painted Roman portraits are the Fayum mummy portraits, named for the place in Egypt where they were found, that covered the faces of the mummified dead. Preserved by Egypt's arid climate, the portraits constitute the largest surviving group of portrait panel painting from the Classical era. Most of the mummy portraits were created between the 1 st century BCE and the 3 rd century CE and reflect the intertwining of Roman and Egyptian traditions, during the time when Egypt was under Rome's rule. Though idealized, the paintings display remarkably individualistic and naturalistic characteristics.

Later Developments - After Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

The influence of Classical Art and architecture cannot be overestimated, as it extends to all art movements and periods of Western art. While Roman architecture and Greek art influenced the Romanesque and Byzantine periods, the influence of Classical Art became dominant in the Italian Renaissance, founded upon a revival of interest in Classical principles, philosophy, and aesthetic ideals. The Parthenon and the Pantheon as well as the writings of Vitruvius informed the architectural theories and practice of Leon Battista Alberti and Palladio and designs into the modern era, including those of Le Corbusier .

Greek sculpture influenced Renaissance artists Michelangelo , Albrecht Dürer , Leonardo da Vinci , Raphael , and the later Baroque artists, including Bernini . The discoveries at Pompeii informed the aesthetic theories of Johann Joachim Winckelmann in the 18 th century and the development of Neoclassicism , as seen in Antonio Canova's sculptures. The modern sculptor Auguste Rodin was influenced primarily by the Parthenon Marbles, of which he wrote, they "had...a rejuvenating influence, and those sensations caused me to follow Nature all the more closely in my studies." Artists from the Futurist Umberto Boccioni , the Surrealist Salvador Dalí , and the multifaceted Pablo Picasso , to, later, Yves Klein , Sanford Biggers, and Banksy all cited Greek art as an influence.

Classical Art has also influenced other art forms, as both the choreography of Isidore Cunningham and Merce Cunningham were influenced by the Parthenon Marbles, and the first fashion garment featured in the Museum of Modern Art in 2003 was Henriette Negrin and Mariano Fortuny y Madrazos' Delphos Gown (1907) a silk dress inspired by the Charioteer Delphi (c. 500 BCE) which had been discovered a decade earlier. The legends, gods, philosophies and art of the Classical era became essential elements of subsequent Western culture and consciousness.

Useful Resources on Classical Greek and Roman Art and Architecture

- Treasures of Ancient Greece | 1 of 3 | The Age of Heroes Our Pick BBC

- Seeing the Parthenon through Greek Eyes Joan Breton Connelly, author of "The Parthenon Enigma," joins Jeffrey Brown

- Vestiges of an ancient Greek art form, preserved by catastrophe January 25, 2016

- The Foundations of Classical Architecture: Roman Classicism Talk by Calder Loth

- Greek Art (World of Art) By John Boardman

- Roman Art By Nancy H. Romage and Andrew Romage

- The Art & Architecture of Ancient Greece Our Pick By Nigel Rodgers

- Roman Architecture Our Pick By Frank Sear

- Athenian Vase Painting: Black- and Red-Figure Techniques Our Pick

- How the Parthenon Lost Its Marbles Our Pick By Juan Pablo Sanchez / National Geographic Magazine / March 4, 2017

- If It Pleases the Gods By Caroline Alexander / New York Times / January 26, 2014

- Why we're still up in arms about the mystery of the Venus de Milo Our Pick By Jonathan Jones / The Guardian / May 11, 2015

- Deep-frieze By Daniel Mendelsohn / The New Yorker / April 14, 2014

- When the Parthenon Had Dazzling Colours Our Pick By Natalie Haynes / BBC / January 22, 2018

- A Look at Emperor Augustus and Roman Classical Style Our Pick By Roderick Conway Morris / New York Times / December 17, 2013

- The Body Beautiful: The Classical Ideal in Ancient Greek Art By Alastair Macaulay / New York Times / May 18, 2015

- The Latest Scheme for the Parthenon By Mary Beard / New York Review of Books / March 6, 2014

- I, Augustus, Emperor of Rome..., at the Grand Palais in Paris, review: 'dazzling and charismatic' By Alastair Sooke / The Telegraph / March 18, 2014

- The top 10 ancient Greek artworks By Jonathan Jones / The Guardian / August 14, 2014

Similar Art

Tempietto (1502)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Rebecca Seiferle

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Kimberly Nichols

Introduction to ancient Greek art

A shared language, religion, and culture

Ancient Greece can feel strangely familiar. From the exploits of Achilles and Odysseus , to the treatises of Aristotle , from the exacting measurements of the Parthenon (image above) to the rhythmic chaos of the Laocoön (image below), ancient Greek culture has shaped our world. Thanks largely to notable archaeological sites, well-known literary sources, and the impact of Hollywood ( Clash of the Titans , for example), this civilization is embedded in our collective consciousness—prompting visions of epic battles, erudite philosophers, gleaming white temples, and limbless nudes (we now know the sculptures—even the ones that decorated temples like the Parthenon—were brightly painted, and, of course, the fact that the figures are often missing limbs is the result of the ravages of time).

Athanadoros, Hagesandros, and Polydoros of Rhodes, Laocoön and his Sons, early first century C.E., marble, 7’10 1/2″ high (Vatican Museums; photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

Dispersed around the Mediterranean and divided into self-governing units called poleis or city-states , the ancient Greeks were united by a shared language, religion, and culture. Strengthening these bonds further were the so-called “Panhellenic” sanctuaries and festivals that embraced “all Greeks” and encouraged interaction, competition, and exchange (for example the Olympics, which were held at the Panhellenic sanctuary at Olympia). Although popular modern understanding of the ancient Greek world is based on the classical art of fifth century B.C.E. Athens, it is important to recognize that Greek civilization was vast and did not develop overnight.

The Dark Ages (c. 1100–c. 800 B.C.E.) to the Orientalizing Period (c. 700–600 B.C.E.)

Following the collapse of the Mycenaean citadels of the late Bronze Age, the Greek mainland was traditionally thought to enter a “Dark Age” that lasted from c. 1100 until c. 800 B.C.E. Not only did the complex socio-cultural system of the Mycenaeans disappear, but also its numerous achievements (i.e., metalworking, large-scale construction, writing). The discovery and continuous excavation of a site known as Lefkandi , however, drastically alters this impression. Located just north of Athens, Lefkandi has yielded an immense apsidal structure (almost fifty meters long), a massive network of graves, and two heroic burials replete with gold objects and valuable horse sacrifices. One of the most interesting artifacts, ritually buried in two separate graves, is a centaur figurine (see photos below). At fourteen inches high, the terracotta creature is composed of a equine (horse) torso made on a potter’s wheel and hand-formed human limbs and features. Alluding to mythology and perhaps a particular story, this centaur embodies the cultural richness of this period.

Centaur, c. 900 B.C.E. (Proto-Geometric period), terracotta, 14 inches high, the head was found in tomb 1 and the body was found in tomb 3 in the cemetery of Toumba, Lefkandi, Greece (detail of head photo: Dan Diffendale CC BY-NC-SA 2)