Microsoft 365 Life Hacks > Writing > The pros and cons of the five-paragraph essay

The pros and cons of the five-paragraph essay

The five-paragraph essay is a writing structure typically taught in high school. Structurally, it consists of an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. This clear structure helps students connect points into a succinct argument. It’s a great introductory structure, but only using this writing formula has its limitations.

What is a five-paragraph essay?

Outside of the self-titled structure, the five-paragraph essay has additional rules. To start, your introductory paragraph should include a hook to captivate your audience. It should also introduce your thesis , or the argument you are proving. The thesis should be one sentence, conclude your introductory paragraph, and include supporting points. These points will become the body of your essay. The body paragraphs should introduce a specific point, include examples and supporting information, and then conclude. This process is repeated until you reach the fifth concluding paragraph, in which you summarize your essay.

Get the most out of your documents with Word

Elevate your writing and collaborate with others - anywhere, anytime

The benefits of a five-paragraph essay

- Your ideas are clear. Presenting your ideas in a succinct, organized manner makes them easy to understand and the five-paragraph essay is designed for that. It provides a clear outline to follow. And most importantly, it’s organized around the thesis, so the argument can be traced from the beginning of the essay to its conclusion. When learning how to write essays, losing track of your thesis can be a common mistake. By using this structure, it’s harder to go on tangents. Each of your points are condensed into a single paragraph. If you struggle presenting your ideas, following this structure might be your best bet.

- It’s simple. Creating an essay structure takes additional brainpower and time to craft. If an essay is timed in an exam, relying on this method is helpful. You can quickly convey your ideas so you can spend more time writing and less structuring your essay.

- It helps build your writing skills. If you’re new to writing essays, this is a great tool. Since the structure is taken care of, you can practice writing and build your skills. Learn more writing tips to improve your essays.

The cons of writing a five-paragraph essay

- The structure is rigid. Depending on its usage, the structure and convention of the five paragraphs can make creating an essay easier to understand and write. However, for writing outside of a traditional high school essay, this format can be limiting. To illustrate points creatively, you might want to create a different structure to illustrate your argument.

- Writing becomes repetitive. This format quickly becomes repetitive. Moving from body-to-body paragraph using the same rules and format creates a predictable rhythm. Reading this predictable format can become dull. And if you’re writing for a college professor, they will want you to showcase creativity in your writing. Try using a different essay structure to make your writing more interesting

- Lack of transitions. Quickly moving through ideas in a five-paragraph structure essay doesn’t always leave room for transitions. The structure is too succinct. Each paragraph only leaves enough space for a writer to broadly delve into an idea and then move onto the next. In longer essays, you can use additional paragraphs to connect ideas. Without transitions, essays in this format can feel choppy, as each point is detached from the previous one

- Its rules can feel unnecessary. Breaking your essay into three body paragraphs keeps it concise. But is three the perfect number of body paragraphs? Some arguments might need more support than three points to substantiate them. Limiting your argument to three points can weaken its credibility and can feel arbitrary for a writer to stick to.

Creating essays using the five-paragraph structure is situational. Use your best judgement to decide when to take advantage of this essay formula. If you’re writing on a computer with Microsoft Word , try using Microsoft Editor to edit your essay.

Get started with Microsoft 365

It’s the Office you know, plus the tools to help you work better together, so you can get more done—anytime, anywhere.

Topics in this article

More articles like this one.

What is independent publishing?

Avoid the hassle of shopping your book around to publishing houses. Publish your book independently and understand the benefits it provides for your as an author.

What are literary tropes?

Engage your audience with literary tropes. Learn about different types of literary tropes, like metaphors and oxymorons, to elevate your writing.

What are genre tropes?

Your favorite genres are filled with unifying tropes that can define them or are meant to be subverted.

What is literary fiction?

Define literary fiction and learn what sets it apart from genre fiction.

Everything you need to achieve more in less time

Get powerful productivity and security apps with Microsoft 365

Explore Other Categories

- >> Return to Heinemann.com

Dedicated to Teachers

- Penny Kittle

- Creative Writing

- Kelly Gallagher

- Teaching Writing

- 4 Essential Studies

- Middle School

- Education Policy

- Language Arts

- Lucy Calkins

- View All Topics

Why the Five-Paragraph Essay is a Problem Now—and Later

.png?width=1200&name=Why%20the%20Five-Paragraph%20Essay%20is%20a%20Problem%20Now%E2%80%94and%20Later.%20(1).png)

Belief #1: The five-paragraph essay is a problem now

Current common approaches for teaching writing are simultaneously too punishing and not nearly challenging enough. Part of the problem is how “rigor” is viewed in education. “Rigor” means “strictness” and “severity.” It is an artifact of a different time and a different mentality toward schooling. It remains popular mostly as a way to invoke days of yore that are supposedly better than today. . . . When students say a class was “hard,” they often mean “confusing” or “arbitrary,” rather than stimulating and challenging. (2018, 142)

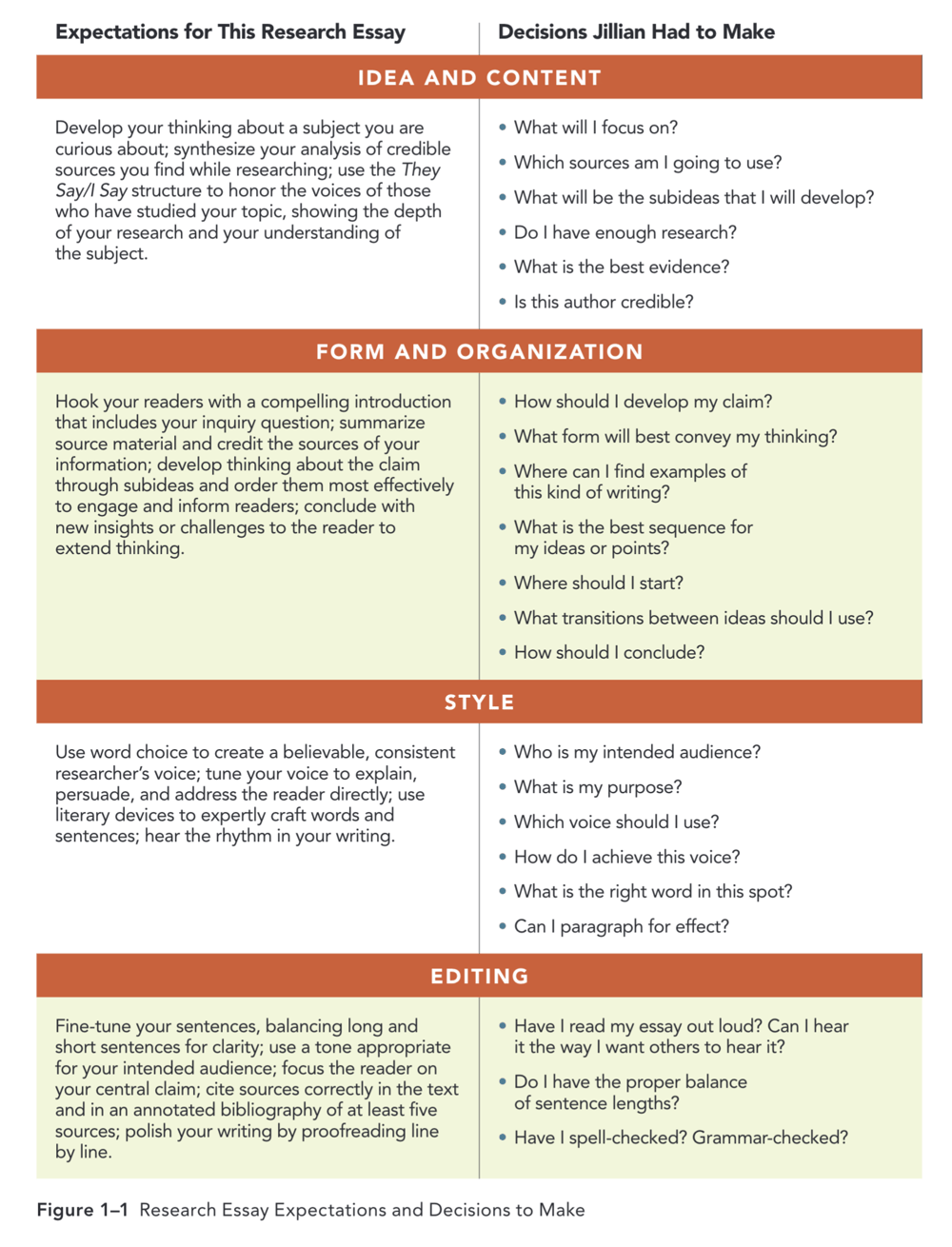

We would add the following to the list of arbitrary and confusing approaches to teaching writing: rules that demand paragraphs will contain five (or nine or whatever) sentences; the topic sentence will always be first in each paragraph; and the thesis or claim must always be directly stated in the introduction. These rules do not represent excellence in writing. On the contrary: in many cases, adhering to them wrings the goodness out of writing. The writer is punished by being shoehorned into a form. Peter Elbow, noted writing researcher, argues that “the five-paragraph essay tends to function as an anti-perplexity machine” (2012, 308). Katherine Bomer agrees, adding, “There is no room for the untidiness of inquiry or complexity and therefore no energy in the writing” (2016, xi). Not only is energy drained from the writing when students practice mechanized thinking, but students also lose the valuable practice of generating and organizing ideas. When the form is predetermined, much of the writer’s important decision-making has already been stripped, which is one reason Penny is now encountering so many college students who believe they cannot solve their own writing problems.

We agree with John Warner’s notion that approaches taken by writing teachers are “not nearly challenging enough” (2018, 142). The form does the thinking for the student, and the student simply plugs in and follows. Without an understanding of options, students can’t imagine how a different form might better engage an audience or how changing the structure might better communicate their ideas. Teachers in high school rarely (if ever) meet across content areas to consider how often students are writing the exact same formulaic essays. The teachers at our schools never met to have these discussions. Students need numerous opportunities to study the various forms an essay can take, and they need repeated practice experimenting. This is not our only objection, however. The lack of student decision-making and agency is compounded when students are constrained by the teacher’s choice of subject and the lack of an authentic audience for their writing. We like how novelist Lily King explains the problems with standardized essays about books:

While you’re reading [the book] rubs off on you and your mind starts working like that for a while. I love that. That reverberation for me is what is most important about literature. . . . I would want kids to talk and write about how the book makes them feel, what it reminded them of, if it changed their thoughts about anything. . . . Questions like [man versus nature] are designed to pull you completely out of the story. . . . Why would you want to pull kids out of the story? You want to push them further in, so they can feel everything the author tried so hard to create for them. (2020, 271)

Night has fallen and is swirling and twirling around me. Gold chains hang across his neckline like trophies against a prize. The fine oil paintings and white pillars line sunken walls. It is a life filled with artificial riches, swishing like change in a pocket of hope. And the noises it made rustled in our dreams.

Abby writes with verve and authenticity. Jillian, the same age, is sitting in a first-year college classroom without the skill set to make the decisions expected of her. And we know this: students get to Abby’s level of essay writing when they’ve experienced a lot of practice in struggling with generating ideas and organizing their thinking. The road to excellence is rife with trial and error. It is up to us to entrust our young writers to wrestle with their decisions. Doing so matters now. And later.

Penny Kittle teaches freshman composition at Plymouth State University in New Hampshire. She was a teacher and literacy coach in public schools for 34 years, 21 of those spent at Kennett High School in North Conway. She is the co-author (with Kelly Gallagher) of Four Essential Studies: Beliefs and Practices to Reclaim Student Agency , as well as the bestselling 180 Days .

Penny is the author of Book Love and Write Beside Them , which won the NCTE James Britton award. She also co-authored two books with her mentor, Don Graves, and co-edited (with Tom Newkirk) a collection of Graves’ work, Children Want to Write . She is the president of the Book Love Foundation and was given the Exemplary Leader Award from NCTE’s Conference on English Leadership. In the summer Penny teaches graduate students at the University of New Hampshire Literacy Institutes. Throughout the year, she travels across the U.S. and Canada (and once in awhile quite a bit farther) speaking to teachers about empowering students through independence in literacy. She believes in curiosity, engagement, and deep thinking in schools for both students and their teachers. Penny stands on the shoulders of her mentors, the Dons (Murray & Graves), and the Toms (Newkirk & Romano), in her belief that intentional teaching in a reading and writing workshop brings the greatest student investment and learning in a classroom.

Learn more about Penny Kittle on her websites, pennykittle.net and booklovefoundation.org , or follow her on twitter .

Topics: Penny Kittle , Creative Writing , Kelly Gallagher , Teaching Writing , 4 Essential Studies

Recent Posts

Popular posts, related posts, on the podcast: the dispatch with penny kittle and kelly gallagher, 4 essential studies with penny kittle, kelly gallagher, and tom newkirk, putting books into the hands of teachers of teenagers: the book love foundation, 4 essential studies - the audiobook.

© 2023 Heinemann, a division of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt

Is the Five-Paragraph Essay History?

- Share article

Has the five-paragraph essay, long a staple in school writing curricula, outlived its usefulness?

The venerable writing tool has largely fallen out of favor among influential English/language arts researchers and professional associations. “Rigid” and “constraining” are the two words critics often use to describe the format.

There’s no denying that a five-paragraph essay—comprising an introduction with a thesis, three paragraphs each with a topic sentence and supporting details, and a conclusion—is highly structured, even artificial, in format. Yet many teachers still rely on it at least to some degree. Supporters of the method argue that, used judiciously, it can be a helpful step on the road to better writing for emerging writers.

“You can’t break the rules until you know the rules. That’s why for me, we definitely teach it and we teach it pretty strongly,” said Mark Anderson, a teacher at the Jonas Bronck Academy in New York City, who recently helped devise a framework for grading student writing based on the five-paragraph form.

Classical Origins

Long before “graphic organizers” and other writing tools entered teachers’ toolkits, students whittled away at five-paragraph essays.

Just where the form originated seems to be something of a mystery, with some scholars pointing to origins as far back as classical rhetoric. Today, the debate about the form is intertwined with broader arguments about literacy instruction: Should it be based on a formally taught set of skills and strategies? Should it be based on a somewhat looser approach, as in free-writing “workshop” models, which are sometimes oriented around student choice of topics and less around matters of grammar and form?

Surprisingly, not much research on writing instruction compares the five-paragraph essay with other tools for teaching writing, said Steve Graham, a professor of educational leadership and innovation at Arizona State University, who has studied writing instruction for more than 30 years.

Instead, meta-analyses seem to point out general features of effective writing instruction. Among other things, they include supportive classroom environments in which students can work together as they learn how to draft, revise, and edit their work; some specific teaching of skills, such as learning to combine sentences; and finally, connecting reading and content acquisition to writing, he said.

As a result, the five-paragraph essay remains a point of passionate debate.

A quick Google search turns up hundreds of articles, both academic and personal, pro and con, with titles like “If You Teach or Write the 5-Paragraph Essay—Stop It!” duking it out with “In Defense of the Five-Paragraph Essay.”

Structure or Straitjacket?

One basic reason why the form lives on is that writing instruction does not appear to be widely or systematically taught in teacher-preparation programs, Graham said, citing surveys of writing teachers he’s conducted.

“It’s used a lot because it provides a structure teachers are familiar with,” he said. “They were introduced to it as students and they didn’t get a lot of preparation on how to teach writing.”

The advent of standardized accountability assessments also seems to have contributed, as teachers sought ways of helping students respond to time-limited prompts, said Catherine Snow, a professor of education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education.

“It simplified the tasks in the classroom and it gives you structures across students that are comparable and gradable, because you have real expectations for structure,” she said.

It’s not clear whether the Common Core State Standards’ new emphases in writing expectations have impacted the five-paragraph essay’s popularity one way or another.

“I don’t connect the two in my mind,” Anderson said. “There is more informational writing and analytical writing, but I haven’t got a sense that the five paragraph format is necessarily the best way to teach it.”

Still, Anderson argues that structure matters a great deal when teaching writing, and the five-paragraph essay has that in spades.

At a prior school, Anderson found that a more free-form workshop model in use tended to fall short for students with disabilities and those who came without a strong foundation in spelling and grammar. The format of a five-paragraph essay provided them with useful scaffolds.

“The structure guides them to organizing their ideas in a way that is very clear, and even if they’re very much at a literal level, they’re at least clearly stating what their ideas are,” he said. “Yes, it is very formulaic. But that’s not to say you can’t have a really good question, with really rich text, and engage students in that question.”

On the other hand, scholars who harbor reservations about the five-paragraph essay argue that it can quickly morph from support to straitjacket. The five-paragraph essay lends itself to persuasive or argumentative writing, but many other types of writing aren’t well served by it, Snow pointed out. You would not use a five-paragraph essay to structure a book review or a work memorandum.

“To teach it extensively I think undermines the whole point of writing,” she said. “You write to communicate something, and that means you have to adapt the form to the function.”

A Balanced Approach

Melissa Mazzaferro, a middle school writing teacher in East Hartford, Conn., tries to draw from the potential strengths of the five-paragraph essay when she teaches writing, without adhering slavishly to it.

A former high school teacher, Mazzaferro heard a lot of complaints from her peers about the weak writing skills of entering high school students and ultimately moved to middle school to look into the problem herself.

Her take on the debate: It’s worth walking students through some of the classic five-paragraph-essay strategies—compare and contrast, cause and effect—but not worth insisting that students limit themselves to three points, if they can extend an idea through multiple scenarios.

“Middle school especially is where they start to learn those building blocks: how you come up with a controlling idea for a writing piece and how you support it with details and examples,” she said. “You want to draw your reader in, to have supportive details, whether it’s five paragraphs or 20. That is where it’s a great starting point.”

But, she adds, it shouldn’t be an ending point. By the time students enter 9th grade, Mazzaferro says that students should be developing more sophisticated arguments.

“I used to help a lot of kids write their college essays, and whenever I saw a five-paragraph essay, I’d make them throw it out and start over,” she said. “At that point, you should be able to break the rules.”

Coverage of the implementation of college- and career-ready standards and the use of personalized learning is supported in part by a grant from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Education Week retains sole editorial control over the content of this coverage.

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Unlearning the Five Paragraph Essay

A key challenge for our freshmen students in the transition from high school to college is to unlearn the five paragraph essay.

I call the five paragraph essay a hot house flower because it cannot blossom in the sun. No professional writers actually use this form. College instructors may be baffled when they witness it. Yet it is the main form that our freshmen students know and deploy.

Unlearning the five paragraph essay may be a greater challenge for our students than learning how to write—with all its messiness—in the first place. As anyone who has tried to master a second language knows, the first language creates interference. We fall back on the inherited patterns of the first language which impede our mastery of the second.

What is the five paragraph essay?

The five paragraph essay encourages its practitioners to produce a thesis with three parts and then to map those three parts onto body paragraphs followed by a conclusion.

The five paragraph essay gives the writer the false comfort of a formula into which to plug ideas. It takes the sting out of thinking—which is one of the primary challenges of writing—and promises us whatever our thoughts, we can reduce them to an over-simplified format.

I have witnessed some student writers attempting to produce six page papers with five horribly bloated paragraphs. It’s like religiously following Siri-narrated map directions into an adjacent lake.

As long as you are not a stickler for nomenclature, some longer essays are also five paragraph essays when they hew to its peculiar logic of listing and mapping. Not all essays with five paragraphs are five paragraph essays when they grow organically—based on a writer’s purposes and design—rather than being held hostage to a formula.

Why is the five paragraph essay a weak form?

It distorts what a thesis is.

This distortion is both conceptual and syntactic.

A thesis presents an arguable idea and also serves as the controlling generalization for the essay as a whole.

One way of conceptualizing a thesis is to use the metaphor of an umbrella (this metaphor comes from an article written by my colleague Karen Gocsik). A thesis is like an umbrella because it is large enough to cover the full range of ideas explored in body paragraphs. When a thesis is distorted by being broken down into the three parts which are then mapped onto the body paragraphs, it serves as three little umbrellas rather than one large one. Student writers aren’t learning to generalize, but to find a poor substitute for generalizing. The three little umbrellas aren't keeping them from getting soaked.

In its crudest form, the three part thesis often devolves into identifying subjects rather than arguments and identifies the areas of focus picked up by the body paragraphs. For example, a student writer might decide to address the issue of friendship in literature, history, and personal experience. Such a tentative thesis focuses on a subject (“friendship”) and three major areas where the writer hopes to address that subject. The writer never identifies the claim about friendship to be developed in the essay, nor even wonders whether it is useful to address these claims in such disparate areas as literature, history, and personal experience. Rather, he or she just joins or adds these three disparate areas together as though they formed an automatically meaningful sequence.

Finally, when a thesis is divided into three parts, the sentence which reports these three parts itself frequently breaks down. It is difficult enough to express an idea in a complete sentence. Try encapsulating three ideas, joining them together, and jamming them into the thesis. Chaos generally ensues.

It distorts the organization of an essay.

The sole organizing principle of the five paragraph essay is that of addition.

A well organized essay is more than the sum of its parts.

Consider the various components that might be included in an essay.

A writer might want to highlight major ideas or issues and minor ones as well.

A writer may want to anticipate and address the arguments of others that run counter to his or her own.

A writer might wish to explain the complicated reasons behind any given phenomenon (mass incarceration, global warming, income disparity) and identify which ones are most compelling and why.

In order to perform the first task one might organize according to a relationship of emphasis: most important, less important, less important still.

In order to perform the second task, one might compare and contrast the various arguments.

In order to perform the third task, one might devote a paragraph to defining the phenomenon and the next to identifying and assessing its causes.

Because it is too rigid in its over-reliance on addition, the five paragraph essay would not allow a writer to organize via emphasis, contrast, or causality. Rather the ideas would have to be presented illogically (as additions) when they should be organized according to other types of relationships which would reflect the real purpose for writing. The form itself encourages incoherence.

The five paragraph essay takes meaning making out of the writer’s hands.

An essay is a vehicle for exploring ideas and creating meaning.

In order to explore ideas, a writer makes a series of decisions about how to present, develop, and organize them.

In order to create meaning, a writer decides how to sequence sentence after sentence and paragraph after paragraph.

The five paragraph essay takes many of these decisions away from the writer. It promises that a formula will replace decision and meaning making. As long as a writer plugs into the formula, the reader will be electrified by the magical results.

As a consequence, students do not develop strategies for the complex expression of their own ideas. How do I best express them? Why should I organize in one way rather than another? How do I anticipate a reader's response to my argument?

It creates the illusion that the form creates meaning instead of the writer. It creates the illusion that it is the sole or primary form so that student writers never learn the full variety of formal approaches.

The five paragraph essay may have been developed out of a well-meaning effort to simplify essay writing for novice writers.But it is not merely a simplification of essay writing, it is an over-simplification. And as such, it limits the development of the cognitive abilities of student writers.

The five paragraph essay does not encourage students to develop the ability to be critical about their own strengths and weaknesses as writers because it turns writing into a check-list of features that are either present or absent.

Why should college instructors pay attention to what students have learned in the past?

Teaching students about writing requires an understanding and acknowledgment about their earlier instruction in the five paragraph essay.

Without understanding the nature of and the reasoning for that past instruction, you will appear to undermine that instruction without a real purpose.

Students won't understand why they are being asked to adapt to a new, unusual, and even strange mode of writing instruction.

They will fall into the familiar and comfortable formulas taught to them in the past because you won't have given them reasons for the new instruction about writing and the challenges you put in their path.

You might not even know that your instruction in writing is new to your students.

In that regard, you and your students may be on a common ground: what is familiar to each of you may not be familiar to the other.

But that common ground is not fertile ground for teaching or learning.

Unlearning the five paragraph essay means unteaching it as well.

The Ultimate Guide to the 5-Paragraph Essay

PeopleImages / Getty Images

- M.Ed., Education Administration, University of Georgia

- B.A., History, Armstrong State University

A five-paragraph essay is a prose composition that follows a prescribed format of an introductory paragraph, three body paragraphs, and a concluding paragraph, and is typically taught during primary English education and applied on standardized testing throughout schooling.

Learning to write a high-quality five-paragraph essay is an essential skill for students in early English classes as it allows them to express certain ideas, claims, or concepts in an organized manner, complete with evidence that supports each of these notions. Later, though, students may decide to stray from the standard five-paragraph format and venture into writing an exploratory essay instead.

Still, teaching students to organize essays into the five-paragraph format is an easy way to introduce them to writing literary criticism, which will be tested time and again throughout their primary, secondary, and further education.

Writing a Good Introduction

The introduction is the first paragraph in your essay, and it should accomplish a few specific goals: capture the reader's interest, introduce the topic, and make a claim or express an opinion in a thesis statement.

It's a good idea to start your essay with a hook (fascinating statement) to pique the reader's interest, though this can also be accomplished by using descriptive words, an anecdote, an intriguing question, or an interesting fact. Students can practice with creative writing prompts to get some ideas for interesting ways to start an essay.

The next few sentences should explain your first statement, and prepare the reader for your thesis statement, which is typically the last sentence in the introduction. Your thesis sentence should provide your specific assertion and convey a clear point of view, which is typically divided into three distinct arguments that support this assertation, which will each serve as central themes for the body paragraphs.

Writing Body Paragraphs

The body of the essay will include three body paragraphs in a five-paragraph essay format, each limited to one main idea that supports your thesis.

To correctly write each of these three body paragraphs, you should state your supporting idea, your topic sentence, then back it up with two or three sentences of evidence. Use examples that validate the claim before concluding the paragraph and using transition words to lead to the paragraph that follows — meaning that all of your body paragraphs should follow the pattern of "statement, supporting ideas, transition statement."

Words to use as you transition from one paragraph to another include: moreover, in fact, on the whole, furthermore, as a result, simply put, for this reason, similarly, likewise, it follows that, naturally, by comparison, surely, and yet.

Writing a Conclusion

The final paragraph will summarize your main points and re-assert your main claim (from your thesis sentence). It should point out your main points, but should not repeat specific examples, and should, as always, leave a lasting impression on the reader.

The first sentence of the conclusion, therefore, should be used to restate the supporting claims argued in the body paragraphs as they relate to the thesis statement, then the next few sentences should be used to explain how the essay's main points can lead outward, perhaps to further thought on the topic. Ending the conclusion with a question, anecdote, or final pondering is a great way to leave a lasting impact.

Once you complete the first draft of your essay, it's a good idea to re-visit the thesis statement in your first paragraph. Read your essay to see if it flows well, and you might find that the supporting paragraphs are strong, but they don't address the exact focus of your thesis. Simply re-write your thesis sentence to fit your body and summary more exactly, and adjust the conclusion to wrap it all up nicely.

Practice Writing a Five-Paragraph Essay

Students can use the following steps to write a standard essay on any given topic. First, choose a topic, or ask your students to choose their topic, then allow them to form a basic five-paragraph by following these steps:

- Decide on your basic thesis , your idea of a topic to discuss.

- Decide on three pieces of supporting evidence you will use to prove your thesis.

- Write an introductory paragraph, including your thesis and evidence (in order of strength).

- Write your first body paragraph, starting with restating your thesis and focusing on your first piece of supporting evidence.

- End your first paragraph with a transitional sentence that leads to the next body paragraph.

- Write paragraph two of the body focussing on your second piece of evidence. Once again make the connection between your thesis and this piece of evidence.

- End your second paragraph with a transitional sentence that leads to paragraph number three.

- Repeat step 6 using your third piece of evidence.

- Begin your concluding paragraph by restating your thesis. Include the three points you've used to prove your thesis.

- End with a punch, a question, an anecdote, or an entertaining thought that will stay with the reader.

Once a student can master these 10 simple steps, writing a basic five-paragraph essay will be a piece of cake, so long as the student does so correctly and includes enough supporting information in each paragraph that all relate to the same centralized main idea, the thesis of the essay.

Limitations of the Five-Paragraph Essay

The five-paragraph essay is merely a starting point for students hoping to express their ideas in academic writing; there are some other forms and styles of writing that students should use to express their vocabulary in the written form.

According to Tory Young's "Studying English Literature: A Practical Guide":

"Although school students in the U.S. are examined on their ability to write a five-paragraph essay , its raison d'être is purportedly to give practice in basic writing skills that will lead to future success in more varied forms. Detractors feel, however, that writing to rule in this way is more likely to discourage imaginative writing and thinking than enable it. . . . The five-paragraph essay is less aware of its audience and sets out only to present information, an account or a kind of story rather than explicitly to persuade the reader."

Students should instead be asked to write other forms, such as journal entries, blog posts, reviews of goods or services, multi-paragraph research papers, and freeform expository writing around a central theme. Although five-paragraph essays are the golden rule when writing for standardized tests, experimentation with expression should be encouraged throughout primary schooling to bolster students' abilities to utilize the English language fully.

- 100 Persuasive Essay Topics

- Examples of Great Introductory Paragraphs

- How To Write an Essay

- How to Write a Great Essay for the TOEFL or TOEIC

- How to Write and Format an MBA Essay

- Write an Attention-Grabbing Opening Sentence for an Essay

- How to Structure an Essay

- Paragraph Writing

- 3 Changes That Will Take Your Essay From Good To Great

- What Is Expository Writing?

- How to Help Your 4th Grader Write a Biography

- Definition and Examples of Body Paragraphs in Composition

- What an Essay Is and How to Write One

- Definition and Examples of Analysis in Composition

- An Introduction to Academic Writing

- The Introductory Paragraph: Start Your Paper Off Right

Steven D. Krause

Writer, Professor, and Everything Else

More than three reasons why the five paragraph essay is bad

From Household Opera comes this good discussion about the five paragraph essay. For anyone invested in composition and rhetoric theory and practice, this isn’t exactly a news flash, but this discussion and the many links Amanda has here suggests to me that it is becoming the conventional wisdom for all kinds of folks outside of composition studies, too.

My favorite critique of the five paragraph essay is in Jasper Neel’s book Plato, Derrida, and Writing; he argues the five paragraph essay comes from Plato’s notions of the way rhetoric and arguments work, and Neel convincingly explains why the five paragraph essay is “anti-writing.” A very worthwhile read.

In my own mind, learning how to write a five paragraph essay is the same as learning how to fill out a form. Filling out a form is obviously not the same as writing, though people do need to learn how to fill out forms, and the five paragraph essay does have its uses. For example, the five paragraph form works well for any sort of timed writing like an essay test. But the five paragraph form becomes a problem for students when they learn it is the only tool they will ever need to write anything, sort of like using a hammer to bake a pie.

Yet, as easy as it is to note how wrong the five paragraph essay is, we do see its form in all sorts of different kinds of writing and settings. Ultimately, it is an embodiment of the “holy trinity”– a beginning and an end, sure, but also a division of everything into three mysterious parts, a father, a son, a holy spirit/ghost. This division of three is everywhere– small, medium, large, etc. And most dissertations (including mine) are divided into… five chapters…

Share this:

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Shopping Cart

Advanced Search

- Browse Our Shelves

- Best Sellers

- Digital Audiobooks

- Featured Titles

- New This Week

- Staff Recommended

- Reading Lists

- Upcoming Events

- Ticketed Events

- Science Book Talks

- Past Events

- Video Archive

- Online Gift Codes

- University Clothing

- Goods & Gifts from Harvard Book Store

- Hours & Directions

- Newsletter Archive

- Frequent Buyer Program

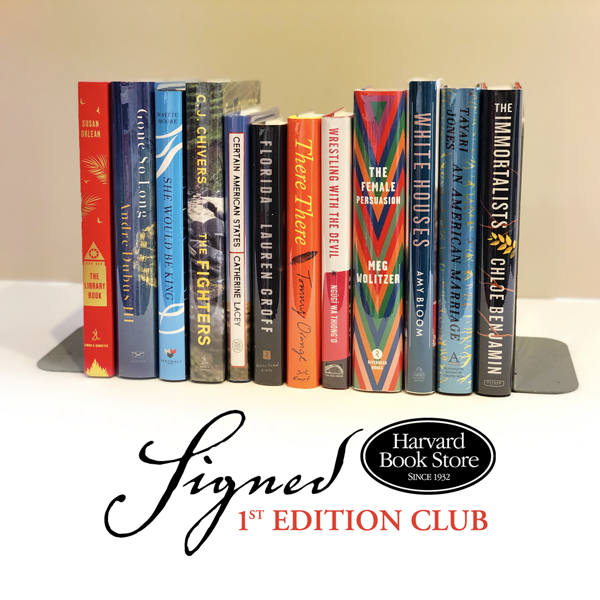

- Signed First Edition Club

- Signed New Voices in Fiction Club

- Off-Site Book Sales

- Corporate & Special Sales

- Print on Demand

- All Our Shelves

- Academic New Arrivals

- New Hardcover - Biography

- New Hardcover - Fiction

- New Hardcover - Nonfiction

- New Titles - Paperback

- African American Studies

- Anthologies

- Anthropology / Archaeology

- Architecture

- Asia & The Pacific

- Astronomy / Geology

- Boston / Cambridge / New England

- Business & Management

- Career Guides

- Child Care / Childbirth / Adoption

- Children's Board Books

- Children's Picture Books

- Children's Activity Books

- Children's Beginning Readers

- Children's Middle Grade

- Children's Gift Books

- Children's Nonfiction

- Children's/Teen Graphic Novels

- Teen Nonfiction

- Young Adult

- Classical Studies

- Cognitive Science / Linguistics

- College Guides

- Cultural & Critical Theory

- Education - Higher Ed

- Environment / Sustainablity

- European History

- Exam Preps / Outlines

- Games & Hobbies

- Gender Studies / Gay & Lesbian

- Gift / Seasonal Books

- Globalization

- Graphic Novels

- Hardcover Classics

- Health / Fitness / Med Ref

- Islamic Studies

- Large Print

- Latin America / Caribbean

- Law & Legal Issues

- Literary Crit & Biography

- Local Economy

- Mathematics

- Media Studies

- Middle East

- Myths / Tales / Legends

- Native American

- Paperback Favorites

- Performing Arts / Acting

- Personal Finance

- Personal Growth

- Photography

- Physics / Chemistry

- Poetry Criticism

- Ref / English Lang Dict & Thes

- Ref / Foreign Lang Dict / Phrase

- Reference - General

- Religion - Christianity

- Religion - Comparative

- Religion - Eastern

- Romance & Erotica

- Science Fiction

- Short Introductions

- Technology, Culture & Media

- Theology / Religious Studies

- Travel Atlases & Maps

- Travel Lit / Adventure

- Urban Studies

- Wines And Spirits

- Women's Studies

- World History

- Writing Style And Publishing

Why They Can’t Write: Killing the Five-Paragraph Essay and Other Necessities

There seems to be widespread agreement that?when it comes to the writing skills of college students?we are in the midst of a crisis. In Why They Can’t Write, John Warner, who taught writing at the college level for two decades, argues that the problem isn’t caused by a lack of rigor, or smartphones, or some generational character defect. Instead, he asserts, we’re teaching writing wrong. Warner blames this on decades of educational reform rooted in standardization, assessments, and accountability. We have done no more, Warner argues, than conditioned students to perform "writing-related simulations," which pass temporary muster but do little to help students develop their writing abilities. This style of teaching has made students passive and disengaged. Worse yet, it hasn’t prepared them for writing in the college classroom. Rather than making choices and thinking critically, as writers must, undergraduates simply follow the rules?such as the five-paragraph essay?designed to help them pass these high-stakes assessments. In Why They Can’t Write, Warner has crafted both a diagnosis for what ails us and a blueprint for fixing a broken system. Combining current knowledge of what works in teaching and learning with the most enduring philosophies of classical education, this book challenges readers to develop the skills, attitudes, knowledge, and habits of mind of strong writers.

There are no customer reviews for this item yet.

Classic Totes

Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more!

Shipping & Pickup

We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail!

Noteworthy Signed Books: Join the Club!

Join our Signed First Edition Club (or give a gift subscription) for a signed book of great literary merit, delivered to you monthly.

Harvard Square's Independent Bookstore

© 2024 Harvard Book Store All rights reserved

Contact Harvard Book Store 1256 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138

Tel (617) 661-1515 Toll Free (800) 542-READ Email [email protected]

View our current hours »

Join our bookselling team »

We plan to remain closed to the public for two weeks, through Saturday, March 28 While our doors are closed, we plan to staff our phones, email, and harvard.com web order services from 10am to 6pm daily.

Store Hours Monday - Saturday: 9am - 11pm Sunday: 10am - 10pm

Holiday Hours 12/24: 9am - 7pm 12/25: closed 12/31: 9am - 9pm 1/1: 12pm - 11pm All other hours as usual.

Map Find Harvard Book Store »

Online Customer Service Shipping » Online Returns » Privacy Policy »

Harvard University harvard.edu »

- Clubs & Services

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

By Quentin Vieregge

The five-paragraph essay (5PE) doesn’t have many vocal defenders in Departments of English in higher education, but for some instructors, the 5PE remains a useful tool in the pedagogi cal kit. Most college writing instructors have eschewed the 5PE, contending that it limits what writing can be, constricts writers’ roles, and even arbitrarily shapes writers’ thoughts. Yet, defenders of the 5PE counter that beginning writers need the guidance and structure that it affords. It works, they say, and it gives writers a place from which to start.

Reflect as You Read

Why does the reader begin by discussing the viewpoints of people who might be proponents of the 5PE? How does starting with acknowledging the validity of the form affect his argument?

The 5PE may sound familiar. In its most basic form, it is an introduction, three points, and a conclusion. Students are often given a topic to discuss, a passage to respond to, or a question to answer. The introduction and body paragraphs typically follow prescribed conventions regardless of content. For instance, the introduction has an attention-getter and explains what others have said about the topic, and the thesis usually comes close to the end of the paragraph. Each of the body paragraphs has a topic sentence that makes a claim that can be backed up with evidence and that refers back to the thesis. Each topic sentence is followed by sentences that provide evidence and reinforce the thesis. The body paragraphs end with a wrap-up sentence. The conclusion reminds the reader of the main idea, summarizes the main points, and might even leave the reader with one lasting impression. If all that sounds familiar, then it might be because you were taught the 5PE. Defenders of the 5PE can sometimes be found in high schools or two-year colleges, where they might work with students who struggle with writing or are learning English as a second language. One such teacher, David Gugin, writes about how the five-paragraph model benefits students learning English as a second language. Like many proponents of the 5PE, he assumes that the main impediment to expressing an idea is knowing how to organize it. As he puts it, “Once they have the vessel, so to speak, they can start thinking more about what to fill it with.”

This type of metaphor abounds. Byung-In Seo compares writing to building a house: One builds a basic structure and the individ ual spark comes from personalizing the details, either decorating the house or the content of the essay. She refers particularly to her experience with at-risk students, usually meaning students who come into college without the writing skills needed to immediately dive into college-level work. Similarly, Susanna L. Benko describes the 5PE as scaffolding that can either enhance or hinder student learning. A scaffold can be useful as construction workers move about when working on a building, but it should be removed when the building can stand on its own; the problem, as Benko observes, is when neither teacher nor student tears down the scaffold.

Here is the thing, though: When writers (and critics) talk about the 5PE, they’re not really talking about five paragraphs any more than critics or proponents of fast-food restaurants are talking about McDonald’s. Most defenders of the 5PE will either explic itly or implicitly see the sentence, the paragraph, and the essay as reflections of each other. Just as an essay has a thesis, a paragraph has a topic sentence; just as a paper has evidence to support it, a paragraph has detail. An essay has a beginning, middle, and end; so does a paragraph. To quote a line from William Blake, to be a defender of the 5PE is “To see a World in a Grain of Sand.” There are circles within circles within circles from this perspective. If you take this approach to writing, form is paramount. Once you under stand the form, you can say anything within it.

This focus on form first (and on the use of the 5PE) is a hall mark of what composition scholars call the current-traditional approach to writing instruction. The current-traditional approach is traceable to the late 19 th century, but still persists today in the 5PE and in writing assignments and textbooks organized around a priori modes of writing (the modes being definition, argument, exposition, and narrative). Current-traditional rhetoric valorizes form, structure, and arrangement over discovering and developing ideas. In current-traditional pedagogy, knowledge does not need to be interpreted or analyzed, but merely apprehended. Writing processes are mostly about narrowing and defining ideas and about applying style as external dressing to a finished idea.

The article focuses on a distinction between writing for form or structure and writing for the rhetorical situation. Which of these have you done before?

Detractors of the 5PE claim that it all but guarantees that writing will be a chore. What fun is it to write when you have no choices, when the shape of your words and thoughts are controlled by an impersonal model that everyone uses, but only in school? Teaching the 5PE is like turning students into Charlie Chaplin’s character from Modern Times , stuck in the gears of writing. The 5PE allegedly dehumanizes people. A number of writing special ists from University of North Carolina–Charlotte wrote an arti cle called, “The Five-Paragraph Essay and the Deficit Model of Education.” One of their critiques is that this model means that students aren’t taught to think and feel fully; rather they’re taught to learn their place as future workers in an assembly line econ omy: topic sentence, support, transition, repeat. Finally, as several writing instructors have observed, the 5PE doesn’t comport with reality. Who actually writes this way? Who actually reads this way? Does anyone care if an essay in The Atlantic or David Sedaris’s non-fiction collection Me Talk Pretty One Day doesn’t follow some prescriptive model? If the model doesn’t connect to how people actually write when given a choice, then how useful can it be?

Well, as it happens, formulaic writing has some support. Two such people who support it are Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, coauthors of one of a celebrated writing textbook, They Say/I Say . Graff and Birkenstein’s book rests on the assumption that all writers—especially skilled writers—use templates, which they’ve learned over time. For instance, there are templates for thesis sentences, templates for counterarguments, templates for rebut tals, templates for introducing quotes, and templates for explaining what quotations mean. One example from their book is this: “While they rarely admit as much, __________ often take for granted that _______,” which is a template students might use to begin writ ing their paper. Students are supposed to plug their own thoughts into the blanks to help them express their thoughts. Graff and Birkenstein tackle the issue of whether templates inhibit creativ ity. They make several of the same arguments that proponents of the 5PE make: Skilled writers use templates all the time; they actually enhance creativity; and they’re meant to guide and inspire rather than limit. This doesn’t mean Graff and Birkenstein love the 5PE, though. In an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education , they contend that templates are an accurate reflection of how people write because templates are dialogic, but the 5PE is not.

Formulas, including templates, can be effective, and arbitrary formulas can be useful under the right circumstances too. They can be useful if they are used as a point-of-inquiry, meaning if writers use them as a starting place rather than a destination when writing. In what ways does the five-paragraph model work for this partic ular assignment? How should I deviate from it? Should I have an implied thesis rather than an explicit one?

Now, you might be thinking, that’s well and good for begin ning students, but what about advanced students or professionals? They never use formulas. Well, when my proposal for this piece was accepted, the two editors sent me explicit instructions about how to organize the essay. They divided their instructions into “first paragraph,” “middle paragraphs,” and “later paragraphs,” and then instructions about what comes after the essay. Within each part, they gave specific directions; everything was spelled out. I had a problem; I planned to argue in favor of the five-paragraph essay, so I couldn’t use their formula, which presupposed I would argue against the bad idea.

Hmm. That conundrum required me to ask myself questions, to inquire. How should I innovate from the model? How should I not? Their prescriptive advice was a point-of-inquiry for me that forced me to think rhetorically and creatively. Maybe the five-para graph model can be a point-of-inquiry—a way to start asking ques tions about rhetoric and writing. When I wrote this piece, I asked myself, “Why do the editors want me to write using a specific format?” And I then asked, “In what ways does this format prevent or enable me from making my point?” Finally, I asked, “In what ways can I exploit the tension between what they want me to do and what I feel I must do?” Asking these questions forced me to think about audience and purpose. But, perhaps more crucially, I was forced to think of the editors’ purpose, not just my own. By understanding their purpose, the format was more than an arbi trary requirement but an artifact indicating a dynamic rhetorical context that I, too, played a role in.

Once I understood the purpose behind the format for this essay, I could restructure it in purposeful and creative ways. The 5PE follows the same logic. Teachers often, mistakenly, think of it as an arbitrary format, but it’s only arbitrary if students and teachers don’t converse and reflect on its purpose. Once students consider their teacher’s purpose in assigning it, then the format becomes contextualized in consideration of audience, purpose, and context, and students are able to negotiate the expectations of the model with their own authorial wishes.

Reflect on Your Reading

- Where does Vieregge’s argument agree with the one made in “The Five Paragraph Essay Transmits Knowledge”? Where does Vieregge disagree?

- Who do you think the audience is for this essay? Think about which audience might need this information or be already thinking about this topic? What context clues in the essay support your answer?

- How can asking questions and analyzing a writing task help you apply the knowledge you already have?

Further Reading For more information about the connection between the five-paragraph essay and current-traditional rhetoric, you might read Michelle Tremmel’s “What to Make of the Five-Paragraph Theme: History of the Genre and Implications.” For a critique of the 5PE, you might read Lil Brannon et al.’s “The Five-Paragraph Essay and the Deficit Model of Education.” If you’re interested in reading defenses for the 5PE, you might start with Byung-In Seo’s “Defending the Five-Paragraph Essay.” A longer more formal argument in favor of the 5PE can be found in David Gugin’s “A Paragraph-First Approach to the Teaching of Academic Writing.” In the essay, “In Teaching Composition, ‘Formulaic’ Is Not a 4-Letter Word,” Cathy Birkenstein and Gerald Graff criticize the 5PE but defend writing formulas done in more rhetorically effective ways.

Defenses of the five-paragraph theme often frame the genre as a scaffolding device. Susanna Benko’s essay, “Scaffolding: An Ongoing Process to Support Adolescent Writing Development,” explains the importance of scaffolding and how that technique can be misapplied. Though her essay only partially addresses the 5PE, her argument can be applied to the genre’s potential advantages and disadvantages.

Keywords basic writing, current-traditional rhetoric, discursive writing, five-paragraph essay (or theme), prescriptivism

Author Bio Quentin Vieregge is a faculty member in the Department of English at the University of Wisconsin–Barron County, a two-year liberal arts college. He teaches first-year composition, advanced composition, business writing, literature, and film courses. He can be followed on Twitter at @Vieregge. His website is quentin vieregge.com.

To the extent possible under law, Lisa Dunick has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to Readings for Writing , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Teaching College English

the glory and the challenges

Is the 5-paragraph essay always bad?

I realize, quite well thank you, that the five-paragraph essay is not always good. Sometimes it is rote, formulaic, and poorly applied. Despite that, in my freshman composition courses, I teach the five-paragraph essay because my students don’t know how to write an essay at all.

Am I doing the wrong thing?

Community College Spotlight had a post that brought this question up for me again.

I particularly liked the response the author had to the article “Why Can’t Tiffany Write?”

When I was in high school, we did nothing but expository writing for four years. Our model was the 3-3-3 paragraph: One thesis sentence with a subject and an attitude supported by three topic sentences, each with a subject and attitude and each supported by three subtopic sentences, each with a subject and attitude and each supported by three “concrete and specific†details. It drove us nuts, but we learned to support our assertions. College writing was a snap.

I really like that idea. Even though it is even more formulaic. I think it could work for my students.

One thought on “Is the 5-paragraph essay always bad?”

I tried to leave a comment in the linked blog, but it wouldn’t let me. As a 9-12 teacher, I use the 5 paragraph essay with my lower grades and lower level students. It provides structure to their thinking, especially when they lack the experience to express themselves on literary topics.

With upper level grades or advanced students, we really focus on tight theses and support, not so much on format.

I think the reason that this is an issue with colleges is systemic to both the k-12 system and college system. While it is true that public schools often don’t push students to develop critical thinking skills, and therefore produce poor writers, it is also true that colleges are being run more and more as businesses, and accepting students of lower caliber.

I don’t believe that there has ever been a time in history where a society has attempted to educate, at such a high level, it’s entire populace. So, we have a systemic ‘problem’ that emerges as poorly literate college students, when really they’re highly literate elementary ones.

Our district is really undergoing growing pains as we develop a comprehensive k-12 literacy program. As a 13 year veteran, I’m basically relearning my craft. I don’t think it’s that high schools are necessarily producing less literate students, it’s just that more are choosing to go to college than ever before, and current research in literacy is exposing a gap that we’ve had for quite some time.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of followup comments via e-mail

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Module: Beyond the Five-Paragraph Essay

Why it matters: beyond the five-paragraph essay.

College writing is different from high school writing. College professors view you as independent junior scholars and imagine you writing with a genuine, driving interest in tackling a complex question. They envision you approaching an assignment without a pre-existing thesis. They expect you to look deep into the evidence, consider several alternative explanations, and work out an original, insightful argument that you actually care about. This kind of scholarly approach usually entails writing a rough draft, through which you work out an ambitious thesis and the scope of your argument, and then starting over with a wholly rewritten second draft containing a more complete argument anchored by a refined thesis.

In that second round, you’ll discover holes in the argument that should be remedied, counterarguments that should be acknowledged and addressed, and important implications that should be noted. That means further reading and research, more revision, and more drafting. When the paper is substantially complete, you’ll go through it again to tighten up the writing and ensure clarity, cohesion, and coherence. Writing a paper isn’t about getting the “right answer” and adhering to basic conventions; it’s about joining an academic conversation with something original to say, borne of rigorous thought. That’s why, as a college writer, you’ll need to move beyond the five-paragraph essay. This module will introduce you to strategies for doing just that.

- Why It Matters: Writing Process. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Really? Writing? Again?.. Authored by : Amy Guptill.. Provided by : The College at Brockport, SUNY.. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/writing-in-college-from-competence-to-excellence/ . Project : Writing in College: From Competence to Excellence. . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Hiker on Dune Ridges at Sunset. Authored by : Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/greatsanddunesnpp/35474169820/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Our Mission

Alternatives to the 5 Paragraph Essay

While the standard essay format is a useful scaffold, it’s important to teach students other, more authentic kinds of writing as well.

There are benefits to assigning a five-paragraph essay.

Its sturdy structure provides students with a safe and organized way to express their thoughts. The introduction enables them to stake a claim with the thesis. The body paragraphs are where they can make assertions and provide the supporting details to prove their argument. The conclusion wraps it all up, reinforcing the main ideas.

Many students need that predictability. They need that familiar structure to develop a thoughtful progression of ideas.

Teachers know what to expect from five-paragraph essays, too. And that’s why they work well—there’s a clarity to them. Both the writing and the grading are neat and orderly.

But the five-paragraph essay isn’t the be-all, end-all of student writing. It’s often reduced to formulas and templates, stifling creativity and originality. A student’s voice is often masked, hidden under monotonous sentences and bland vocabulary.

There are other, more authentic ways in which students can flesh out complex thoughts, experiment with voice, and present a sequence of ideas in an organized way.

Five Ideas for Authentic Student Writing

Stephen King, in his memoir, On Writing , recognized the weight of writing. He understood that each time any writer approaches the blank page, there is an opportunity to craft something meaningful and powerful: “You can approach the act of writing with nervousness, excitement, hopefulness, or even despair—the sense that you can never completely put on the page what’s in your mind and heart. You can come to the act with your fists clenched and your eyes narrowed.... Come to it any way but lightly. Let me say it again: You must not come lightly to the blank page.”

Here are five ways students can turn a blank page into a powerful expression of their mind and heart.

1. Blogs: Rather than have students write essays about the novels, stories, and articles they read during the year, have them create and maintain a blog. I’ve written about the power of blogging before. Each year blogging is voted my students’ favorite unit, and it’s been the best way for them to break free from the confines of the five-paragraph essay.

While a traditional essay can box students into a limited area, a blog allows them to express themselves as they see fit. Because of the many customization options, each blog can be unique. And that personal space creates the conditions for more authentic writing because it naturally fosters a student’s voice, style, and thoughts.

2. Multigenre research papers: A multigenre research paper communicates a central thesis through a variety of pieces composed in an assortment of genres. The genres run the gamut from a journal entry to a newspaper article, a biographical summary to a pop-up book. Here’s a great introduction to multigenre possibilities .

While each piece in the paper has its own purpose, identity, and style, the whole of the paper is more than the sum of its parts because the multigenre research paper assimilates research, advances an argument, and has an organizational structure just like a traditional research paper. What distinguishes it from its counterpart is its creative versatility. Students must not only choose the genres that best suit their purpose but also display a wide swath of writing skills as they follow the conventions of the various genres.

3. Infographics: It’s easy to look at infographics as collections of images with some facts or statistics. A better way to see them is as organized distillations of complex ideas told in a bold and powerful way.

Infographics can be created to show comparisons, explain rules or a process, show trends, present a timeline, and so much more. The best infographics don’t just display information—they take the reader on a well-crafted journey, using visuals, research, and concise writing to arrive at an enlightened conclusion. The New York Times has a useful introduction to teaching with infographics.

4. Debates: Debates incorporate a broad array of skills that are foundational to the Common Core State Standards. In my AP literature class, I’ve had my students formally debate who is the true monster in Frankenstein , Victor or his creation, and in my public speaking class they’ve tackled topical issues such as “Should college athletes be paid?” and “Has Christmas become too commercial?”

I love the way debates naturally enable students to read critically, write persuasively, listen attentively, and speak forcefully, all within the same unit. They write out opening statements and closing arguments, and must anticipate what their opponents will say and have talking points written out so that they can offer convincing counter-arguments. It’s cool to see them edit their writing, especially the closing arguments, on the fly in reaction to what transpires in the debate.

The Guardian has a brief guide to getting your students debating.

5. Parody/satire: In order to create an imitation or exaggeration of something, you must possess a keen awareness of its style, format, and effect. Parodies encourage students to transform something familiar into something comedic and fresh.

I have my students create modern-day parodies of famous poems. Using William Wordsworth’s “The World Is Too Much With Us,” a student created his own sonnet, “The World Is Too Much With Snapchat.” And inspired by Gwendolyn Brooks’s “We Real Cool,” a poem about high school dropouts, a student penned “We Still Drool,” about infants still dependent on their parents.

For inspiration, ReadWriteThink has a four-session lesson plan on using the movie Shrek to explore satire.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

5.5: The Five-Paragraph Essay is Rhetorically Sound

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 60966

- Cheryl E. Ball & Drew M. Loewe ed.

- West Virginia University via Digital Publishing Institute and West Virginia University Libraries

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Author: Quentin Vieregge, Department of English, University of Wisconsin–Barron County

The five-paragraph essay (5PE) doesn’t have many vocal defenders in Departments of English in higher education, but for some instructors, the 5PE remains a useful tool in the pedagogical kit. Most college writing instructors have eschewed the 5PE, contending that it limits what writing can be, constricts writers’ roles, and even arbitrarily shapes writers’ thoughts. Yet, defenders of the 5PE counter that beginning writers need the guidance and structure that it affords. It works, they say, and it gives writers a place from which to start.

The 5PE may sound familiar. In its most basic form, it is an introduction, three points, and a conclusion. Students are often given a topic to discuss, a passage to respond to, or a question to answer. The introduction and body paragraphs typically follow prescribed conventions regardless of content. For instance, the introduction has an attention-getter and explains what others have said about the topic, and the thesis usually comes close to the end of the paragraph. Each of the body paragraphs has a topic sentence that makes a claim that can be backed up with evidence and that refers back to the thesis. Each topic sentence is followed by sentences that provide evidence and reinforce the thesis. The body paragraphs end with a wrap-up sentence. The conclusion reminds the reader of the main idea, summarizes the main points, and might even leave the reader with one lasting impression.

If all that sounds familiar, then it might be because you were taught the 5PE. Defenders of the 5PE can sometimes be found in high schools or two-year colleges, where they might work with students who struggle with writing or are learning English as a second language. One such teacher, David Gugin, writes about how the five-paragraph model benefits students learning English as a second language. Like many proponents of the 5PE, he assumes that the main impediment to expressing an idea is knowing how to organize it. As he puts it, “Once they have the vessel, so to speak, they can start thinking more about what to fill it with.”

This type of metaphor abounds. Byung-In Seo compares writing to building a house: One builds a basic structure and the individual spark comes from personalizing the details, either decorating the house or the content of the essay. She refers particularly to her experience with at-risk students, usually meaning students who come into college without the writing skills needed to immediately dive into college-level work. Similarly, Susanna L. Benko describes the 5PE as scaffolding that can either enhance or hinder student learning. A scaffold can be useful as construction workers move about when working on a building, but it should be removed when the building can stand on its own; the problem, as Benko observes, is when neither teacher nor student tears down the scaffold.

Here is the thing, though: When writers (and critics) talk about the 5PE, they’re not really talking about five paragraphs any more than critics or proponents of fast-food restaurants are talking about McDonald’s. Most defenders of the 5PE will either explicitly or implicitly see the sentence, the paragraph, and the essay as reflections of each other. Just as an essay has a thesis, a paragraph has a topic sentence; just as a paper has evidence to support it, a paragraph has detail. An essay has a beginning, middle, and end; so does a paragraph. To quote a line from William Blake, to be a defender of the 5PE is “To see a World in a Grain of Sand.” There are circles within circles within circles from this perspective. If you take this approach to writing, form is paramount. Once you understand the form, you can say anything within it.

This focus on form first (and on the use of the 5PE) is a hallmark of what composition scholars call the current-traditional approach to writing instruction. The current-traditional approach is traceable to the late 19th century, but still persists today in the 5PE and in writing assignments and textbooks organized around a priori modes of writing (the modes being definition, argument, exposition, and narrative). Current-traditional rhetoric valorizes form, structure, and arrangement over discovering and developing ideas. In current-traditional pedagogy, knowledge does not need to be interpreted or analyzed, but merely apprehended. Writing processes are mostly about narrowing and defining ideas and about applying style as external dressing to a finished idea.

Detractors of the 5PE claim that it all but guarantees that writing will be a chore. What fun is it to write when you have no choices, when the shape of your words and thoughts are controlled by an impersonal model that everyone uses, but only in school? Teaching the 5PE is like turning students into Charlie Chaplin’s character from Modern Times , stuck in the gears of writing. The 5PE allegedly dehumanizes people. A number of writing specialists from University of North Carolina–Charlotte wrote an article called, “The Five-Paragraph Essay and the Deficit Model of Education.” One of their critiques is that this model means that students aren’t taught to think and feel fully; rather they’re taught to learn their place as future workers in an assembly line economy: topic sentence, support, transition, repeat. Finally, as several writing instructors have observed, the 5PE doesn’t comport with reality. Who actually writes this way? Who actually reads this way? Does anyone care if an essay in The Atlantic or David Sedaris’s non-fiction collection Me Talk Pretty One Day doesn’t follow some prescriptive model? If the model doesn’t connect to how people actually write when given a choice, then how useful can it be?

Well, as it happens, formulaic writing has some support. Two such people who support it are Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, coauthors of one of a celebrated writing textbook, They Say/I Say . Graff and Birkenstein’s book rests on the assumption that all writers—especially skilled writers—use templates, which they’ve learned over time. For instance, there are templates for thesis sentences, templates for counterarguments, templates for rebuttals, templates for introducing quotes, and templates for explaining what quotations mean. One example from their book is this: “While they rarely admit as much, __________ often take for granted that _______,” which is a template students might use to begin writing their paper. Students are supposed to plug their own thoughts into the blanks to help them express their thoughts. Graff and Birkenstein tackle the issue of whether templates inhibit creativity. They make several of the same arguments that proponents of the 5PE make: Skilled writers use templates all the time; they actually enhance creativity; and they’re meant to guide and inspire rather than limit. This doesn’t mean Graff and Birkenstein love the 5PE, though. In an article in The Chronicle of Higher Education , they contend that templates are an accurate reflection of how people write because templates are dialogic, but the 5PE is not.

Formulas, including templates, can be effective, and arbitrary formulas can be useful under the right circumstances too. They can be useful if they are used as a point-of-inquiry, meaning if writers use them as a starting place rather than a destination when writing. In what ways does the five-paragraph model work for this particular assignment? How should I deviate from it? Should I have an implied thesis rather than an explicit one?

Now, you might be thinking, that’s well and good for beginning students, but what about advanced students or professionals? They never use formulas. Well, when my proposal for this piece was accepted, the two editors sent me explicit instructions about how to organize the essay. They divided their instructions into “first paragraph,” “middle paragraphs,” and “later paragraphs,” and then instructions about what comes after the essay. Within each part, they gave specific directions; everything was spelled out. I had a problem; I planned to argue in favor of the five-paragraph essay, so I couldn’t use their formula, which presupposed I would argue against the bad idea.

Hmm. That conundrum required me to ask myself questions, to inquire. How should I innovate from the model? How should I not? Their prescriptive advice was a point-of-inquiry for me that forced me to think rhetorically and creatively. Maybe the five-paragraph model can be a point-of-inquiry—a way to start asking questions about rhetoric and writing. When I wrote this piece, I asked myself, “Why do the editors want me to write using a specific format?” And I then asked, “In what ways does this format prevent or enable me from making my point?” Finally, I asked, “In what ways can I exploit the tension between what they want me to do and what I feel I must do?” Asking these questions forced me to think about audience and purpose. But, perhaps more crucially, I was forced to think of the editors’ purpose, not just my own. By understanding their purpose, the format was more than an arbitrary requirement but an artifact indicating a dynamic rhetorical context that I, too, played a role in.

Once I understood the purpose behind the format for this essay, I could restructure it in purposeful and creative ways. The 5PE follows the same logic. Teachers often, mistakenly, think of it as an arbitrary format, but it’s only arbitrary if students and teachers don’t converse and reflect on its purpose. Once students consider their teacher’s purpose in assigning it, then the format becomes contextualized in consideration of audience, purpose, and context, and students are able to negotiate the expectations of the model with their own authorial wishes.

Further Reading

If you’re interested in reading defenses for the 5PE, you might start with Byung-In Seo’s “Defending the Five-Paragraph Essay.” A longer more formal argument in favor of the 5PE can be found in David Gugin’s “A Paragraph-First Approach to the Teaching of Academic Writing.” In the essay, “In Teaching Composition, ‘Formulaic’ Is Not a 4-Letter Word,” Cathy Birkenstein and Gerald Graff criticize the 5PE but defend writing formulas done in more rhetorically effective ways.