- Skip to global menu .

- Skip to primary navigation .

- Skip to secondary navigation .

- Skip to page content .

- Return to global menu .

- Search Library site

- Search UVic

- Search for people

- Search for departments

- Search for experts

- Search for news

- Search for resources

- tips and tutorials

- what's a journal?

What's a journal?

A journal is a scholarly publication containing articles written by researchers, professors and other experts. Journals focus on a specific discipline or field of study. Unlike newspapers and magazines, journals are intended for an academic or technical audience, not general readers.

Most journal articles...

- Are peer reviewed

- Have original research

- Focus on current developments

- Cite other works and have bibliographies

- Can be in print, online or both

Journals are published on a regular basis (monthly, quarterly, etc.) and are sequentially numbered.

Each copy is an issue ; a set of issues makes a volume (usually each year is a separate volume). Like newspapers and magazines, journals are also called periodicals or serials.

Take the Peer Review Tutorial here

Email [email protected]

What's new?

- Return to primary navigation .

- Return to secondary navigation .

- Return to page content .

- UNO Criss Library

Social Work Research Guide

What is a research journal.

- Find Articles

- Find E-Books and Books

Reading an Academic Article

- Free Online Resources

- Reference and Writing

- Citation Help This link opens in a new window

Anatomy of a Scholarly Article

TIP: When possible, keep your research question(s) in mind when reading scholarly articles. It will help you to focus your reading.

Title : Generally are straightforward and describe what the article is about. Titles often include relevant key words.

Abstract : A summary of the author(s)'s research findings and tells what to expect when you read the full article. It is often a good idea to read the abstract first, in order to determine if you should even bother reading the whole article.

Discussion and Conclusion : Read these after the Abstract (even though they come at the end of the article). These sections can help you see if this article will meet your research needs. If you don’t think that it will, set it aside.

Introduction : Describes the topic or problem researched. The authors will present the thesis of their argument or the goal of their research.

Literature Review : May be included in the introduction or as its own separate section. Here you see where the author(s) enter the conversation on this topic. That is to say, what related research has come before, and how do they hope to advance the discussion with their current research?

Methods : This section explains how the study worked. In this section, you often learn who and how many participated in the study and what they were asked to do. You will need to think critically about the methods and whether or not they make sense given the research question.

Results : Here you will often find numbers and tables. If you aren't an expert at statistics this section may be difficult to grasp. However you should attempt to understand if the results seem reasonable given the methods.

Works Cited (also be called References or Bibliography ): This section comprises the author(s)’s sources. Always be sure to scroll through them. Good research usually cites many different kinds of sources (books, journal articles, etc.). As you read the Works Cited page, be sure to look for sources that look like they will help you to answer your own research question.

Adapted from http://library.hunter.cuny.edu/research-toolkit/how-do-i-read-stuff/anatomy-of-a-scholarly-article

A research journal is a periodical that contains articles written by experts in a particular field of study who report the results of research in that field. The articles are intended to be read by other experts or students of the field, and they are typically much more sophisticated and advanced than the articles found in general magazines. This guide offers some tips to help distinguish scholarly journals from other periodicals.

CHARACTERISTICS OF RESEARCH JOURNALS

PURPOSE : Research journals communicate the results of research in the field of study covered by the journal. Research articles reflect a systematic and thorough study of a single topic, often involving experiments or surveys. Research journals may also publish review articles and book reviews that summarize the current state of knowledge on a topic.

APPEARANCE : Research journals lack the slick advertising, classified ads, coupons, etc., found in popular magazines. Articles are often printed one column to a page, as in books, and there are often graphs, tables, or charts referring to specific points in the articles.

AUTHORITY : Research articles are written by the person(s) who did the research being reported. When more than two authors are listed for a single article, the first author listed is often the primary researcher who coordinated or supervised the work done by the other authors. The most highly‑regarded scholarly journals are typically those sponsored by professional associations, such as the American Psychological Association or the American Chemical Society.

VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY : Articles submitted to research journals are evaluated by an editorial board and other experts before they are accepted for publication. This evaluation, called peer review, is designed to ensure that the articles published are based on solid research that meets the normal standards of the field of study covered by the journal. Professors sometimes use the term "refereed" to describe peer-reviewed journals.

WRITING STYLE : Articles in research journals usually contain an advanced vocabulary, since the authors use the technical language or jargon of their field of study. The authors assume that the reader already possesses a basic understanding of the field of study.

REFERENCES : The authors of research articles always indicate the sources of their information. These references are usually listed at the end of an article, but they may appear in the form of footnotes, endnotes, or a bibliography.

PERIODICALS THAT ARE NOT RESEARCH JOURNALS

POPULAR MAGAZINES : These are periodicals that one typically finds at grocery stores, airport newsstands, or bookstores at a shopping mall. Popular magazines are designed to appeal to a broad audience, and they usually contain relatively brief articles written in a readable, non‑technical language.

Examples include: Car and Driver , Cosmopolitan , Esquire , Essence , Gourmet , Life , People Weekly , Readers' Digest , Rolling Stone , Sports Illustrated , Vanity Fair , and Vogue .

NEWS MAGAZINES : These periodicals, which are usually issued weekly, provide information on topics of current interest, but their articles seldom have the depth or authority of scholarly articles.

Examples include: Newsweek , Time , U.S. News and World Report .

OPINION MAGAZINES : These periodicals contain articles aimed at an educated audience interested in keeping up with current events or ideas, especially those pertaining to topical issues. Very often their articles are written from a particular political, economic, or social point of view.

Examples include: Catholic World , Christianity Today , Commentary , Ms. , The Militant , Mother Jones , The Nation , National Review , The New Republic , The Progressive , and World Marxist Review .

TRADE MAGAZINES : People who need to keep up with developments in a particular industry or occupation read these magazines. Many trade magazines publish one or more special issues each year that focus on industry statistics, directory lists, or new product announcements.

Examples include: Beverage World , Progressive Grocer , Quick Frozen Foods International , Rubber World , Sales and Marketing Management , Skiing Trade News , and Stores .

Literature Reviews

- Literature Review Guide General information on how to organize and write a literature review.

- The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It Contains two sets of questions to help students review articles, and to review their own literature reviews.

- << Previous: Find E-Books and Books

- Next: Statistics >>

- Last Updated: Mar 8, 2024 11:27 AM

- URL: https://libguides.unomaha.edu/social_work

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Understanding the Differences Between a Research Paper and a Journal

When it comes to academic writing, one of the most important distinctions that must be made is between a research paper and a journal. A research paper is an in-depth exploration of a specific topic; while journals are collections of articles on various topics relating to the same subject or field. Understanding these differences can help researchers ensure they’re using the right tools for their particular project. This article will outline key differences between a research paper and journal, as well as discuss how each type contributes to academia. Furthermore, it will provide examples of both types of work from several different fields in order to further explain how they differ in format, content and purpose.

I. Introduction

Ii. what is a research paper, iii. what is a journal, iv. types of journals and their purpose, v. differences between a research paper and journal, vi. benefits of publishing in both mediums, vii. conclusion.

As the ever-increasing population of researchers continues to generate vast amounts of knowledge and data, there is a growing need for reliable storage solutions. The research paper , which has been used as an effective means of disseminating information since its emergence in the 19th century, provides a particularly pertinent solution. In essence, it allows scientists from all over the world to store their findings without having to worry about preserving physical copies.

- A research paper acts as an online repository that ensures critical data is not lost or misappropriated; instead it can be referred back to by any interested parties at any given time.

A research paper is a form of academic writing that presents an argument or analysis based on the author’s original research. It typically follows a particular format and structure, which is designed to help readers locate specific pieces of information quickly. The main sections are often titled Introduction, Literature Review, Methodology, Results and Discussion.

Research papers can be written about virtually any topic imaginable but they generally center around literature reviews that include other scholarly work in the field such as journal articles or books. These documents also analyze data collected from surveys and experiments conducted by the author in order to provide evidence for their thesis statement. Additionally, some research papers may incorporate theoretical elements into their discussion section where philosophical concepts are discussed in relation to the findings presented earlier in the document.

- Is Research Paper A Journal?

No – while both types of documents aim to present knowledge within certain subject areas, journals tend towards shorter length content with more broad-reaching themes while research papers usually contain longer lengths with deeper levels of analysis pertaining to a specific area or topic. Furthermore, most journals do not require authorship credit whereas research papers almost always list authors’ names along with references at the end since its contents will serve as primary sources used by future researchers studying similar topics

A journal is an invaluable tool for academic research, allowing scholars to keep track of their work in a systematic and organized way. Journals are typically composed of multiple volumes or issues that each contain different articles related to the same subject matter.

- Periodicals : These journals may be published monthly, quarterly or annually depending on the type of content they focus on. They often cover topics such as news, politics and culture.

- Scholarly/Peer-Reviewed Journals : These publications specialize in scientific literature and other areas requiring advanced degrees. Authors have to submit their papers for peer review before publication.

Scholarly journals are a key resource for researchers to understand and share their findings. Journals come in many shapes and sizes, each with its own purpose.

- Peer-reviewed: These publications have gone through the scrutiny of academics who check the validity of content before it is published. They range from scientific research papers to essays or reviews on topics like literature or philosophy.

The goal of peer-reviewing journals is to keep information accurate and trustworthy by eliminating errors as much as possible. It also helps ensure that readers can rely on the material found within these types of journals.

- Non-peer reviewed: These publications may not be subject to an academic review process, but they do provide valuable perspectives related to specific fields such as history, economics, technology, etc. Some examples include magazines and trade publications containing interviews with experts in various industries.

Is a research paper considered a journal? Yes! Research papers often undergo some form of peer review before being accepted for publication – whether via online submission systems or traditional print publishing models – thus meeting the criteria necessary for them to be classified as scholarly journals. .

Exploring the Nuances

When it comes to academic writing, there are some distinctions between a research paper and a journal. To start with, while they both involve researching an issue in depth, their ultimate purpose differs. A research paper is meant to present original findings on a particular topic that have been gathered from different sources of information; its goal is usually to make new contributions or expand upon existing knowledge within its field of study. On the other hand, journals are intended for publishing comprehensive reviews on topics covered by experts in the field that summarise what has already been established so far – as such, they focus more heavily on disseminating current trends and developments than expanding them further.

The Details

In addition to this general divergence in overall aims and purposes between these two genres of writing, several structural differences can be identified. Generally speaking, research papers tend to be shorter than journals; moreover, unlike published articles which may feature sections such as introduction/background material & methodology before leading into conclusions about their central hypotheses or theories — most research papers will go straight into presenting evidence-based discussion followed by conclusion section without any referenceable materials throughout body content apart from cited works used previously in referencing mentioned ideas. Lastly it should also be noted here that ‘is research paper a journal?’ does not quite fit contextually either since even though traditionally both refer largely towards same domain viz., academics but generally differing levels of complexity across specific aspects definitely exist therein!

Publishing in both a research paper and journal has its advantages. First, publishing in either medium provides an opportunity to make one’s work accessible , allowing it to be seen by other academics and experts within the field. Additionally, publishing can create an avenue for dialogue among peers and colleagues about relevant topics.

Research papers serve as more comprehensive resources than journals . They typically provide authors with greater space for exploration of their ideas, so they are better suited to cover complex topics or those that require a deeper level of explanation. Journals on the other hand offer readers concise information—summarizing current theories or practices related to certain fields—which allows busy professionals quick access when researching new developments.

In conclusion, the research presented in this paper has determined that journaling is a useful and effective tool for dealing with negative emotions. Through self-reflection, individuals can better understand their feelings and learn to manage them more effectively. Journaling also provides an opportunity to engage in positive thought patterns, which leads to increased emotional stability and improved mental health outcomes.

The findings of this study suggest that those who use journals are likely to experience greater psychological well-being than those who do not. By engaging in reflective writing activities on a regular basis, people have access to powerful insights into their own thoughts and behaviors that they may otherwise miss out on if they rely solely on verbal communication or other traditional forms of therapy. Furthermore, since journaling is an inexpensive activity requiring no special training or equipment aside from pen/paper (or digital devices), it is accessible for all individuals regardless of resources available.

English: This article provided a detailed comparison between research papers and journals, presenting their respective characteristics, writing conventions, and importance in academia. Understanding these differences is essential for any student looking to hone their skills as an academic writer. With this knowledge at hand, students can approach any assignment with confidence in knowing how best to structure and compose the text for maximum effect.

- SpringerLink shop

Types of journal articles

It is helpful to familiarise yourself with the different types of articles published by journals. Although it may appear there are a large number of types of articles published due to the wide variety of names they are published under, most articles published are one of the following types; Original Research, Review Articles, Short reports or Letters, Case Studies, Methodologies.

Original Research:

This is the most common type of journal manuscript used to publish full reports of data from research. It may be called an Original Article, Research Article, Research, or just Article, depending on the journal. The Original Research format is suitable for many different fields and different types of studies. It includes full Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion sections.

Short reports or Letters:

These papers communicate brief reports of data from original research that editors believe will be interesting to many researchers, and that will likely stimulate further research in the field. As they are relatively short the format is useful for scientists with results that are time sensitive (for example, those in highly competitive or quickly-changing disciplines). This format often has strict length limits, so some experimental details may not be published until the authors write a full Original Research manuscript. These papers are also sometimes called Brief communications .

Review Articles:

Review Articles provide a comprehensive summary of research on a certain topic, and a perspective on the state of the field and where it is heading. They are often written by leaders in a particular discipline after invitation from the editors of a journal. Reviews are often widely read (for example, by researchers looking for a full introduction to a field) and highly cited. Reviews commonly cite approximately 100 primary research articles.

TIP: If you would like to write a Review but have not been invited by a journal, be sure to check the journal website as some journals to not consider unsolicited Reviews. If the website does not mention whether Reviews are commissioned it is wise to send a pre-submission enquiry letter to the journal editor to propose your Review manuscript before you spend time writing it.

Case Studies:

These articles report specific instances of interesting phenomena. A goal of Case Studies is to make other researchers aware of the possibility that a specific phenomenon might occur. This type of study is often used in medicine to report the occurrence of previously unknown or emerging pathologies.

Methodologies or Methods

These articles present a new experimental method, test or procedure. The method described may either be completely new, or may offer a better version of an existing method. The article should describe a demonstrable advance on what is currently available.

Back │ Next

Explore millions of high-quality primary sources and images from around the world, including artworks, maps, photographs, and more.

Explore migration issues through a variety of media types

- Part of The Streets are Talking: Public Forms of Creative Expression from Around the World

- Part of The Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 34, No. 1 (Winter 2020)

- Part of Cato Institute (Aug. 3, 2021)

- Part of University of California Press

- Part of Open: Smithsonian National Museum of African American History & Culture

- Part of Indiana Journal of Global Legal Studies, Vol. 19, No. 1 (Winter 2012)

- Part of R Street Institute (Nov. 1, 2020)

- Part of Leuven University Press

- Part of UN Secretary-General Papers: Ban Ki-moon (2007-2016)

- Part of Perspectives on Terrorism, Vol. 12, No. 4 (August 2018)

- Part of Leveraging Lives: Serbia and Illegal Tunisian Migration to Europe, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (Mar. 1, 2023)

- Part of UCL Press

Harness the power of visual materials—explore more than 3 million images now on JSTOR.

Enhance your scholarly research with underground newspapers, magazines, and journals.

Explore collections in the arts, sciences, and literature from the world’s leading museums, archives, and scholars.

How to find the right journal for your research (using actual data)

Joanna Wilkinson

Want to help your research flourish? We share tips for using publisher-neutral data and statistics to find the right journal for your research paper.

The right journal helps your research flourish. It puts you in the best position to reach a relevant and engaged audience, and can extend the impact of your paper through a high-quality publishing process.

Unfortunately, finding the right journal is a particular pain point for inexperienced authors and those who publish on interdisciplinary topics. The sheer number of journals published today is one reason for this. More than 42,000 active scholarly peer-reviewed journals were published in 2018 alone, and there’s been accelerated growth of more than 5% in recent years.

The overwhelming growth in journals has left many researchers struggling to find the best home for their manuscripts which can be a daunting prospect after several long months producing research. Submitting to the wrong journal can hinder the impact of your manuscript. It could even result in a series of rejections, stalling both your research and career. Conversely, the right journal can help you showcase your research to the world in an environment consistent with your values.

Keep reading to learn how solutions like Journal Citation Reports ™ (JCR) and Master Journal List can help you find the right journal for your research in the fastest possible time.

What to look for in a journal and why

To find the right journal for your research paper, it’s important to consider what you need and want out of the publishing process.

The goal for many researchers is to find a prestigious, peer-reviewed journal to publish in. This might be one that can support an application for tenure, promotion or future funding. It’s not always that simple, however. If your research is in a specialized field, you may want to avoid a journal with a multidisciplinary focus. And if you have ground-breaking results, you may want to pay attention to journals with a speedy review process and frequent publication schedule. Moreover, you may want to publish your paper as open access so that it’s accessible to everyone—and your institution or funder may also require this.

With so many points to consider, it’s good practice to have a journal in mind before you start writing. We published an earlier post to help you with this: Find top journals in a research field, step-by-step guide . Check it out to discover where the top researchers in your field are publishing.

Already written your manuscript? No problem: this blog will help you use publisher-neutral data and statistics to choose the right journal for your paper.

First stop: Manuscript Matcher in the Master Journal List

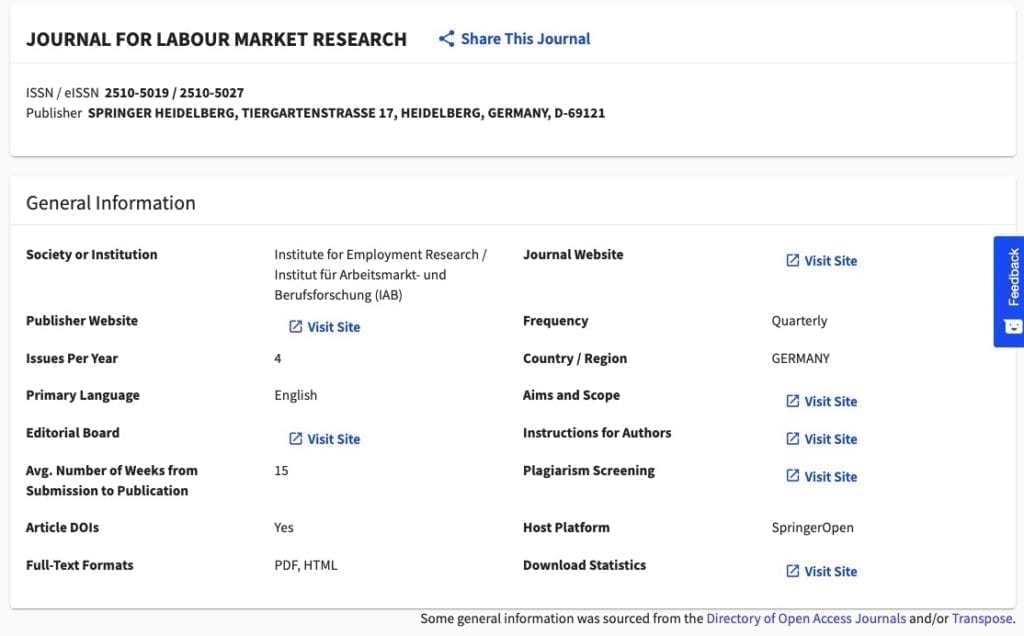

Master Journal List Manuscript Matcher is the ultimate place to begin your search for journals. It is a free tool that helps you narrow down your journal options based on your research topic and goals.

Pairing your research with a journal

Manuscript Matcher, also available via EndNote™ , provides a list of relevant journals indexed in the Web of Science™ . First, you’ll want to input your title and abstract (or keywords, if you prefer). You can then filter your results using the options shown on the left-hand sidebar, or simply click on the profile page of any journal listed.

Each journal page details the journal’s coverage in the Web of Science. Where available, it may also display a wealth of information, including:

- open access information (including whether a journal is Gold OA)

- the journal’s aims and scope

- download statistics

- average number of weeks from submission to publication, and

- peer review information (including type and policy)

Ready to try Manuscript Matcher? Follow this link .

Identify the journals that are a good topical fit for your research using Manuscript Matcher. You can then move to Journal Citation Reports to understand their citation impact, audience and open access statistics.

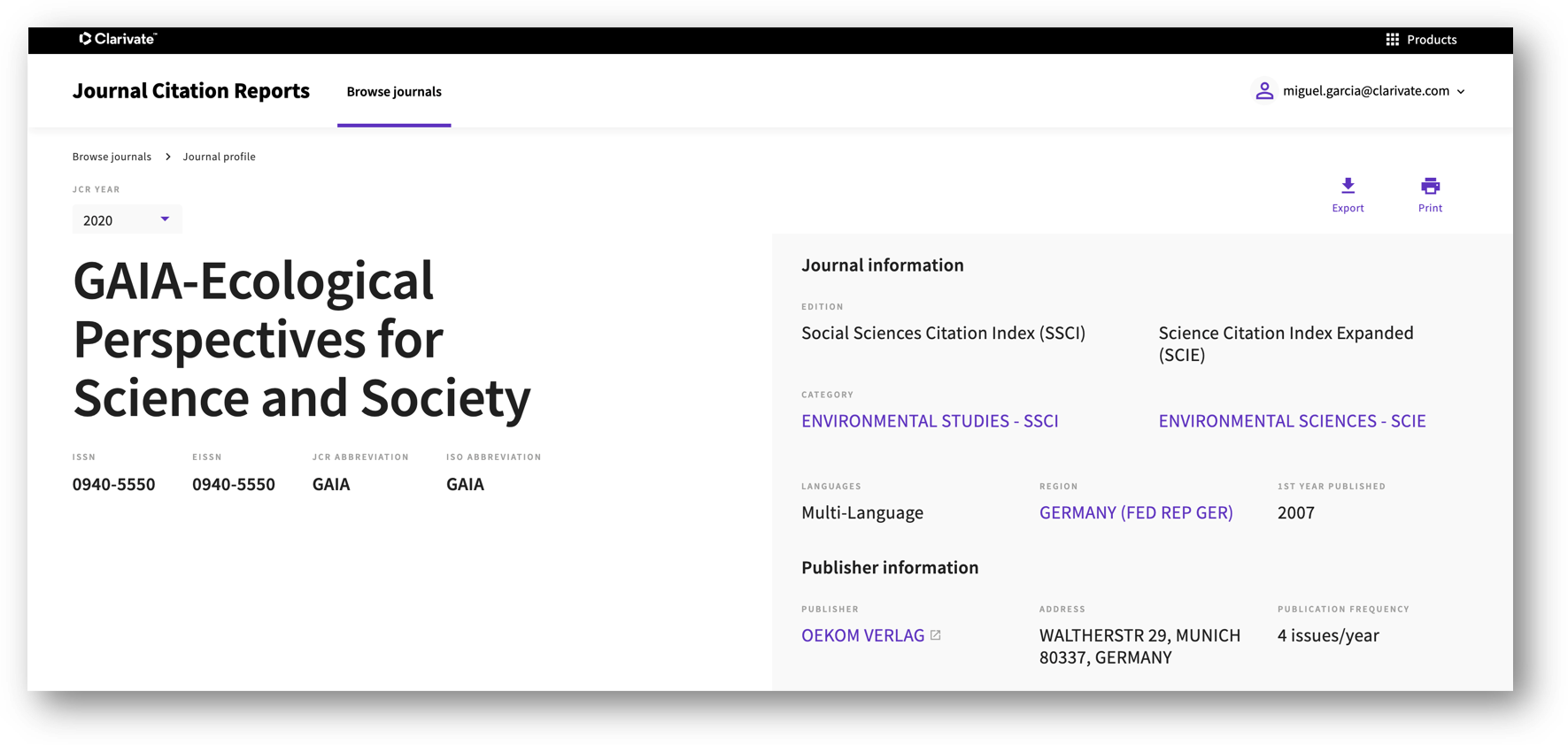

Find the right journal with Journal Citation Reports

Journal Citation Reports is the most powerful solution for journal intelligence. It uses transparent, publisher-neutral data and statistics to provide unique insight into a journal’s role and influence. This will help you produce a definitive list of journals best-placed to publish your findings, and more.

Three data points exist on every journal page to help you assess a journal as a home for your research. These are: citation metrics, article relevance and audience.

Citation Metrics

The Journal Impact Factor™ (JIF) is included as part of the rich array of citation metrics offered on each journal page. It shows how often a journal’s recently published material is cited on average.

Learn how the JIF is calculated in this guide .

It’s important to note that the JIF has its limitations and no researcher should depend on the impact factor alone when assessing the usefulness or prestige of a journal. Journal Citation Reports helps you understand the context of a journal’s JIF and how to use the metric responsibly.

The JCR Trend Graph, for example, places the JIF in the context of time and subject category performance. Citation behavior varies across disciplines, and journals in JCR may be placed across multiple subject categories depending on the scope of their content. The Trend Graph shows you how the journal performs against others in the same subject category. It also gives you an understanding of how stable that performance is year-on-year.

You can learn more about this here .

The 2021 JCR release introduced a new, field-normalized metric for measuring the citation impact of a journal’s recent publications. By normalizing for different fields of research and their widely varying rates of publication and citation, the Journal Citation Indicator provides a single journal-level metric that can be easily interpreted and compared across disciplines. Learn more about the Journal Citation Indicator here .

Article relevance

The Contributing Items section in JCR demonstrates whether the journal is a good match for your paper. It can also validate the information you found in the Manuscript Matcher. You can view the full list in the Web of Science by selecting “Show all.”

JCR helps you understand the scholarly community engaging with a journal on both a country and an institutional level. This information provides insight on where in the world your own paper might have an impact if published in that particular journal. It also gives you a sense of general readership, and who you might be talking to if you choose that journal.

Start using Journal Citation Reports today .

Ready to find the right journal for your paper?

The expansion of scholarly journals in previous years has made it difficult for researchers to choose the right journal for their research. This isn’t a good position to be in when you’ve spent many long months preparing your research for the world. Journal Citation Reports , Manuscript Matcher by Master Journal List and the Web of Science are all products dedicated to helping you find the right home for your paper. Try them out today and help your research flourish.

Stay connected

Want to learn more? You can also read related articles in our Research Smarter series, with guidance on finding the relevant papers for your research and how you can save hundreds of hours in the writing process . You can also read about the 2022 JCR release here . Finally, subscribe to receive our latest news, resources and events to help make your research journey a smart one.

Subscribe to receive regular updates on how to research smarter

Related posts

Unlocking emerging topics in research with research horizon navigator.

Journal Citation Reports 2024 preview: Unified rankings for more inclusive journal assessment

Introducing the Clarivate Academic AI Platform

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

Clara busse.

1 Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599 Chapel Hill, NC USA

Ella August

2 Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI 48109-2029 USA

Associated Data

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table Table1 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table Table2 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common methods section pitfalls and recommendations

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table Table3 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common results section pitfalls and recommendations

Discussion Section

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table Table4 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. (Fig.3) 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

(PDF 362 kb)

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Data Availability

Compliance with ethical standards.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Research Paper – Structure, Examples and Writing Guide

Table of Contents

Research Paper

Definition:

Research Paper is a written document that presents the author’s original research, analysis, and interpretation of a specific topic or issue.

It is typically based on Empirical Evidence, and may involve qualitative or quantitative research methods, or a combination of both. The purpose of a research paper is to contribute new knowledge or insights to a particular field of study, and to demonstrate the author’s understanding of the existing literature and theories related to the topic.

Structure of Research Paper

The structure of a research paper typically follows a standard format, consisting of several sections that convey specific information about the research study. The following is a detailed explanation of the structure of a research paper:

The title page contains the title of the paper, the name(s) of the author(s), and the affiliation(s) of the author(s). It also includes the date of submission and possibly, the name of the journal or conference where the paper is to be published.

The abstract is a brief summary of the research paper, typically ranging from 100 to 250 words. It should include the research question, the methods used, the key findings, and the implications of the results. The abstract should be written in a concise and clear manner to allow readers to quickly grasp the essence of the research.

Introduction

The introduction section of a research paper provides background information about the research problem, the research question, and the research objectives. It also outlines the significance of the research, the research gap that it aims to fill, and the approach taken to address the research question. Finally, the introduction section ends with a clear statement of the research hypothesis or research question.

Literature Review

The literature review section of a research paper provides an overview of the existing literature on the topic of study. It includes a critical analysis and synthesis of the literature, highlighting the key concepts, themes, and debates. The literature review should also demonstrate the research gap and how the current study seeks to address it.

The methods section of a research paper describes the research design, the sample selection, the data collection and analysis procedures, and the statistical methods used to analyze the data. This section should provide sufficient detail for other researchers to replicate the study.

The results section presents the findings of the research, using tables, graphs, and figures to illustrate the data. The findings should be presented in a clear and concise manner, with reference to the research question and hypothesis.

The discussion section of a research paper interprets the findings and discusses their implications for the research question, the literature review, and the field of study. It should also address the limitations of the study and suggest future research directions.

The conclusion section summarizes the main findings of the study, restates the research question and hypothesis, and provides a final reflection on the significance of the research.

The references section provides a list of all the sources cited in the paper, following a specific citation style such as APA, MLA or Chicago.

How to Write Research Paper

You can write Research Paper by the following guide:

- Choose a Topic: The first step is to select a topic that interests you and is relevant to your field of study. Brainstorm ideas and narrow down to a research question that is specific and researchable.

- Conduct a Literature Review: The literature review helps you identify the gap in the existing research and provides a basis for your research question. It also helps you to develop a theoretical framework and research hypothesis.

- Develop a Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the main argument of your research paper. It should be clear, concise and specific to your research question.

- Plan your Research: Develop a research plan that outlines the methods, data sources, and data analysis procedures. This will help you to collect and analyze data effectively.

- Collect and Analyze Data: Collect data using various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments. Analyze data using statistical tools or other qualitative methods.

- Organize your Paper : Organize your paper into sections such as Introduction, Literature Review, Methods, Results, Discussion, and Conclusion. Ensure that each section is coherent and follows a logical flow.

- Write your Paper : Start by writing the introduction, followed by the literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. Ensure that your writing is clear, concise, and follows the required formatting and citation styles.

- Edit and Proofread your Paper: Review your paper for grammar and spelling errors, and ensure that it is well-structured and easy to read. Ask someone else to review your paper to get feedback and suggestions for improvement.

- Cite your Sources: Ensure that you properly cite all sources used in your research paper. This is essential for giving credit to the original authors and avoiding plagiarism.

Research Paper Example

Note : The below example research paper is for illustrative purposes only and is not an actual research paper. Actual research papers may have different structures, contents, and formats depending on the field of study, research question, data collection and analysis methods, and other factors. Students should always consult with their professors or supervisors for specific guidelines and expectations for their research papers.

Research Paper Example sample for Students:

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Mental Health among Young Adults

Abstract: This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults. A literature review was conducted to examine the existing research on the topic. A survey was then administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Introduction: Social media has become an integral part of modern life, particularly among young adults. While social media has many benefits, including increased communication and social connectivity, it has also been associated with negative outcomes, such as addiction, cyberbullying, and mental health problems. This study aims to investigate the impact of social media use on the mental health of young adults.

Literature Review: The literature review highlights the existing research on the impact of social media use on mental health. The review shows that social media use is associated with depression, anxiety, stress, and other mental health problems. The review also identifies the factors that contribute to the negative impact of social media, including social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Methods : A survey was administered to 200 university students to collect data on their social media use, mental health status, and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. The survey included questions on social media use, mental health status (measured using the DASS-21), and perceived impact of social media on their mental health. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Results : The results showed that social media use is positively associated with depression, anxiety, and stress. The study also found that social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO are significant predictors of mental health problems among young adults.

Discussion : The study’s findings suggest that social media use has a negative impact on the mental health of young adults. The study highlights the need for interventions that address the factors contributing to the negative impact of social media, such as social comparison, cyberbullying, and FOMO.

Conclusion : In conclusion, social media use has a significant impact on the mental health of young adults. The study’s findings underscore the need for interventions that promote healthy social media use and address the negative outcomes associated with social media use. Future research can explore the effectiveness of interventions aimed at reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health. Additionally, longitudinal studies can investigate the long-term effects of social media use on mental health.

Limitations : The study has some limitations, including the use of self-report measures and a cross-sectional design. The use of self-report measures may result in biased responses, and a cross-sectional design limits the ability to establish causality.

Implications: The study’s findings have implications for mental health professionals, educators, and policymakers. Mental health professionals can use the findings to develop interventions that address the negative impact of social media use on mental health. Educators can incorporate social media literacy into their curriculum to promote healthy social media use among young adults. Policymakers can use the findings to develop policies that protect young adults from the negative outcomes associated with social media use.

References :

- Twenge, J. M., & Campbell, W. K. (2019). Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Preventive medicine reports, 15, 100918.

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Barrett, E. L., Sidani, J. E., Colditz, J. B., … & James, A. E. (2017). Use of multiple social media platforms and symptoms of depression and anxiety: A nationally-representative study among US young adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 69, 1-9.

- Van der Meer, T. G., & Verhoeven, J. W. (2017). Social media and its impact on academic performance of students. Journal of Information Technology Education: Research, 16, 383-398.

Appendix : The survey used in this study is provided below.

Social Media and Mental Health Survey

- How often do you use social media per day?

- Less than 30 minutes

- 30 minutes to 1 hour

- 1 to 2 hours

- 2 to 4 hours

- More than 4 hours

- Which social media platforms do you use?

- Others (Please specify)

- How often do you experience the following on social media?

- Social comparison (comparing yourself to others)

- Cyberbullying

- Fear of Missing Out (FOMO)

- Have you ever experienced any of the following mental health problems in the past month?

- Do you think social media use has a positive or negative impact on your mental health?

- Very positive

- Somewhat positive

- Somewhat negative

- Very negative

- In your opinion, which factors contribute to the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Social comparison

- In your opinion, what interventions could be effective in reducing the negative impact of social media on mental health?

- Education on healthy social media use

- Counseling for mental health problems caused by social media

- Social media detox programs

- Regulation of social media use

Thank you for your participation!

Applications of Research Paper

Research papers have several applications in various fields, including:

- Advancing knowledge: Research papers contribute to the advancement of knowledge by generating new insights, theories, and findings that can inform future research and practice. They help to answer important questions, clarify existing knowledge, and identify areas that require further investigation.

- Informing policy: Research papers can inform policy decisions by providing evidence-based recommendations for policymakers. They can help to identify gaps in current policies, evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, and inform the development of new policies and regulations.

- Improving practice: Research papers can improve practice by providing evidence-based guidance for professionals in various fields, including medicine, education, business, and psychology. They can inform the development of best practices, guidelines, and standards of care that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- Educating students : Research papers are often used as teaching tools in universities and colleges to educate students about research methods, data analysis, and academic writing. They help students to develop critical thinking skills, research skills, and communication skills that are essential for success in many careers.

- Fostering collaboration: Research papers can foster collaboration among researchers, practitioners, and policymakers by providing a platform for sharing knowledge and ideas. They can facilitate interdisciplinary collaborations and partnerships that can lead to innovative solutions to complex problems.

When to Write Research Paper

Research papers are typically written when a person has completed a research project or when they have conducted a study and have obtained data or findings that they want to share with the academic or professional community. Research papers are usually written in academic settings, such as universities, but they can also be written in professional settings, such as research organizations, government agencies, or private companies.

Here are some common situations where a person might need to write a research paper:

- For academic purposes: Students in universities and colleges are often required to write research papers as part of their coursework, particularly in the social sciences, natural sciences, and humanities. Writing research papers helps students to develop research skills, critical thinking skills, and academic writing skills.

- For publication: Researchers often write research papers to publish their findings in academic journals or to present their work at academic conferences. Publishing research papers is an important way to disseminate research findings to the academic community and to establish oneself as an expert in a particular field.

- To inform policy or practice : Researchers may write research papers to inform policy decisions or to improve practice in various fields. Research findings can be used to inform the development of policies, guidelines, and best practices that can improve outcomes for individuals and organizations.

- To share new insights or ideas: Researchers may write research papers to share new insights or ideas with the academic or professional community. They may present new theories, propose new research methods, or challenge existing paradigms in their field.

Purpose of Research Paper

The purpose of a research paper is to present the results of a study or investigation in a clear, concise, and structured manner. Research papers are written to communicate new knowledge, ideas, or findings to a specific audience, such as researchers, scholars, practitioners, or policymakers. The primary purposes of a research paper are:

- To contribute to the body of knowledge : Research papers aim to add new knowledge or insights to a particular field or discipline. They do this by reporting the results of empirical studies, reviewing and synthesizing existing literature, proposing new theories, or providing new perspectives on a topic.

- To inform or persuade: Research papers are written to inform or persuade the reader about a particular issue, topic, or phenomenon. They present evidence and arguments to support their claims and seek to persuade the reader of the validity of their findings or recommendations.

- To advance the field: Research papers seek to advance the field or discipline by identifying gaps in knowledge, proposing new research questions or approaches, or challenging existing assumptions or paradigms. They aim to contribute to ongoing debates and discussions within a field and to stimulate further research and inquiry.

- To demonstrate research skills: Research papers demonstrate the author’s research skills, including their ability to design and conduct a study, collect and analyze data, and interpret and communicate findings. They also demonstrate the author’s ability to critically evaluate existing literature, synthesize information from multiple sources, and write in a clear and structured manner.

Characteristics of Research Paper

Research papers have several characteristics that distinguish them from other forms of academic or professional writing. Here are some common characteristics of research papers:

- Evidence-based: Research papers are based on empirical evidence, which is collected through rigorous research methods such as experiments, surveys, observations, or interviews. They rely on objective data and facts to support their claims and conclusions.

- Structured and organized: Research papers have a clear and logical structure, with sections such as introduction, literature review, methods, results, discussion, and conclusion. They are organized in a way that helps the reader to follow the argument and understand the findings.

- Formal and objective: Research papers are written in a formal and objective tone, with an emphasis on clarity, precision, and accuracy. They avoid subjective language or personal opinions and instead rely on objective data and analysis to support their arguments.

- Citations and references: Research papers include citations and references to acknowledge the sources of information and ideas used in the paper. They use a specific citation style, such as APA, MLA, or Chicago, to ensure consistency and accuracy.

- Peer-reviewed: Research papers are often peer-reviewed, which means they are evaluated by other experts in the field before they are published. Peer-review ensures that the research is of high quality, meets ethical standards, and contributes to the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Objective and unbiased: Research papers strive to be objective and unbiased in their presentation of the findings. They avoid personal biases or preconceptions and instead rely on the data and analysis to draw conclusions.

Advantages of Research Paper

Research papers have many advantages, both for the individual researcher and for the broader academic and professional community. Here are some advantages of research papers:

- Contribution to knowledge: Research papers contribute to the body of knowledge in a particular field or discipline. They add new information, insights, and perspectives to existing literature and help advance the understanding of a particular phenomenon or issue.

- Opportunity for intellectual growth: Research papers provide an opportunity for intellectual growth for the researcher. They require critical thinking, problem-solving, and creativity, which can help develop the researcher’s skills and knowledge.

- Career advancement: Research papers can help advance the researcher’s career by demonstrating their expertise and contributions to the field. They can also lead to new research opportunities, collaborations, and funding.

- Academic recognition: Research papers can lead to academic recognition in the form of awards, grants, or invitations to speak at conferences or events. They can also contribute to the researcher’s reputation and standing in the field.

- Impact on policy and practice: Research papers can have a significant impact on policy and practice. They can inform policy decisions, guide practice, and lead to changes in laws, regulations, or procedures.

- Advancement of society: Research papers can contribute to the advancement of society by addressing important issues, identifying solutions to problems, and promoting social justice and equality.

Limitations of Research Paper

Research papers also have some limitations that should be considered when interpreting their findings or implications. Here are some common limitations of research papers:

- Limited generalizability: Research findings may not be generalizable to other populations, settings, or contexts. Studies often use specific samples or conditions that may not reflect the broader population or real-world situations.

- Potential for bias : Research papers may be biased due to factors such as sample selection, measurement errors, or researcher biases. It is important to evaluate the quality of the research design and methods used to ensure that the findings are valid and reliable.

- Ethical concerns: Research papers may raise ethical concerns, such as the use of vulnerable populations or invasive procedures. Researchers must adhere to ethical guidelines and obtain informed consent from participants to ensure that the research is conducted in a responsible and respectful manner.

- Limitations of methodology: Research papers may be limited by the methodology used to collect and analyze data. For example, certain research methods may not capture the complexity or nuance of a particular phenomenon, or may not be appropriate for certain research questions.

- Publication bias: Research papers may be subject to publication bias, where positive or significant findings are more likely to be published than negative or non-significant findings. This can skew the overall findings of a particular area of research.

- Time and resource constraints: Research papers may be limited by time and resource constraints, which can affect the quality and scope of the research. Researchers may not have access to certain data or resources, or may be unable to conduct long-term studies due to practical limitations.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Research Objectives – Types, Examples and...

Research Gap – Types, Examples and How to...

Context of the Study – Writing Guide and Examples

Informed Consent in Research – Types, Templates...

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

8 Key Elements of a Research Paper Structure + Free Template (2024)

.webp)

Table of contents

Brinda Gulati

Welcome to the twilight zone of research writing. You’ve got your thesis statement and research evidence, and before you write the first draft, you need a wireframe — a structure on which your research paper can stand tall.

When you’re looking to share your research with the wider scientific community, your discoveries and breakthroughs are important, yes. But what’s more important is that you’re able to communicate your research in an accessible format. For this, you need to publish your paper in journals. And to have your research published in a journal, you need to know how to structure a research paper.

Here, you’ll find a template of a research paper structure, a section-by-section breakdown of the eight structural elements, and actionable insights from three published researchers.

Let’s begin!

Why is the Structure of a Research Paper Important?

A research paper built on a solid structure is the literary equivalent of calcium supplements for weak bones.

Richard Smith of BMJ says, “...no amount of clever language can compensate for a weak structure."

There’s space for your voice and creativity in your research, but without a structure, your paper is as good as a beached whale — stranded and bloated.

A well-structured research paper:

- Communicates your credibility as a student scholar in the wider academic community.

- Facilitates accessibility for readers who may not be in your field but are interested in your research.

- Promotes clear communication between disciplines, thereby eliminating “concept transfer” as a rate-limiting step in scientific cross-pollination.

- Increases your chances of getting published!

Research Paper Structure Template

.webp)

Why Was My Research Paper Rejected?

A desk rejection hurts — sometimes more than stubbing your pinky toe against a table.

Oftentimes, journals will reject your research paper before sending it off for peer review if the architecture of your manuscript is shoddy.

The JAMA Internal Medicine , for example, rejected 78% of the manuscripts it received in 2017 without review. Among the top 10 reasons? Poor presentation and poor English . (We’ve got fixes for both here, don’t you worry.)

5 Common Mistakes in a Research Paper Structure

- Choppy transitions : Missing or abrupt transitions between sections disrupt the flow of your paper. Read our guide on transition words here.

- Long headings : Long headings can take away from your main points. Be concise and informative, using parallel structure throughout.

- Disjointed thoughts : Make sure your paragraphs flow logically from one another and support your central point.

- Misformatting : An inconsistent or incorrect layout can make your paper look unprofessional and hard to read. For font, spacing, margins, and section headings, strictly follow your target journal's guidelines.

- Disordered floating elements : Ill-placed and unlabeled tables, figures, and appendices can disrupt your paper's structure. Label, caption, and reference all floating elements in the main text.

What Is the Structure of a Research Paper?

The structure of a research paper closely resembles the shape of a diamond flowing from the general ➞ specific ➞ general.

We’ll follow the IMRaD ( I ntroduction , M ethods , R esults , and D iscussion) format within the overarching “context-content-conclusion” approach:

➞ The context sets the stage for the paper where you tell your readers, “This is what we already know, and here’s why my research matters.”

➞ The content is the meat of the paper where you present your methods, results, and discussion. This is the IMRad (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) format — the most popular way to organize the body of a research paper.

➞ The conclusion is where you bring it home — “Here’s what we’ve learned, and here’s where it plays out in the grand scheme of things.”

Now, let’s see what this means section by section.

1. Research Paper Title

A research paper title is read first, and read the most.

The title serves two purposes: informing readers and attracting attention . Therefore, your research paper title should be clear, descriptive, and concise . If you can, avoid technical jargon and abbreviations. Your goal is to get as many readers as possible.

In fact, research articles with shorter titles describing the results are cited more often .

An impactful title is usually 10 words long, plus or minus three words.

For example:

- "Mortality in Puerto Rico after Hurricane Maria" (word count = 7)

- “A Review of Practical Techniques For the Diagnosis of Malaria” (word count = 10)

2. Research Paper Abstract

In an abstract, you have to answer the two whats :

- What has been done?

- What are the main findings?

The abstract is the elevator pitch for your research. Is your paper worth reading? Convince the reader here.

✏️ NOTE : According to different journals’ guidelines, sometimes the title page and abstract section are on the same page.

An abstract ranges from 200-300 words and doubles down on the relevance and significance of your research. Succinctly.

This is your chance to make a second first impression.

If you’re stuck with a blob of text and can’t seem to cut it down, a smart AI elf like Wordtune can help you write a concise abstract! The AI research assistant also offers suggestions for improved clarity and grammar so your elevator pitch doesn’t fall by the wayside.

Get Wordtune for free > Get Wordtune for free >

3. Introduction Section

What does it do.

Asks the central research question.

Pre-Writing Questions For the Introduction Section

The introduction section of your research paper explains the scope, context, and importance of your project.

I talked to Swagatama Mukherjee , a published researcher and graduate student in Neuro-Oncology studying Glioblastoma Progression. For the Introduction, she says, focus on answering three key questions:

- What isn’t known in the field?

- How is that knowledge gap holding us back?

- How does your research focus on answering this problem?

When Should You Write It?

Write it last. As you go along filling in the body of your research paper, you may find that the writing is evolving in a different direction than when you first started.

Organizing the Introduction

Visualize the introduction as an upside-down triangle when considering the overall outline of this section. You'll need to give a broad introduction to the topic, provide background information, and then narrow it down to specific research. Finally, you'll need a focused research question, hypothesis, or thesis statement. The move is from general ➞ specific.

✨️ BONUS TIP: Use the famous CARS model by John Swales to nail this upside-down triangle.

4. methods section.

Describes what was done to answer the research question, and how.

Write it first . Just list everything you’ve done, and go from there. How did you assign participants into groups? What kind of questionnaires have you used? How did you analyze your data?

Write as if the reader were following an instruction manual on how to duplicate your research methodology to the letter.

Organizing the Methods Section

Here, you’re telling the story of your research.

Write in as much detail as possible, and in the chronological order of the experiments. Follow the order of the results, so your readers can track the gradual development of your research. Use headings and subheadings to visually format the section.

This skeleton isn’t set in stone. The exact headings will be determined by your field of study and the journal you’re submitting to.

✨️ BONUS TIP : Drowning in research? Ask Wordtune to summarize your PDFs for you!

5. results section .

Reports the findings of your study in connection to your research question.

Write the section only after you've written a draft of your Methods section, and before the Discussion.

This section is the star of your research paper. But don't get carried away just yet. Focus on factual, unbiased information only. Tell the reader how you're going to change the world in the next section. The Results section is strictly a no-opinions zone.

How To Organize Your Results

A tried-and-true structure for presenting your findings is to outline your results based on the research questions outlined in the figures.

Whenever you address a research question, include the data that directly relates to that question.

What does this mean? Let’s look at an example:

Here's a sample research question:

How does the use of social media affect the academic performance of college students?

Make a statement based on the data:

College students who spent more than 3 hours per day on social media had significantly lower GPAs compared to those who spent less than 1 hour per day (M=2.8 vs. M=3.4; see Fig. 2).

You can elaborate on this finding with secondary information:

The negative impact of social media use on academic performance was more pronounced among freshmen and sophomores compared to juniors and seniors ((F>25), (S>20), (J>15), and (Sr>10); see Fig. 4).

Finally, caption your figures in the same way — use the data and your research question to construct contextual phrases. The phrases should give your readers a framework for understanding the data:

Figure 4. Percentage of college students reporting a negative impact of social media on academic performance, by year in school.

Dos and Don’ts For The Results Section

✔️ Related : How to Write a Research Paper (+ Free AI Research Paper Writer)

6. discussion section.

Explains the importance and implications of your findings, both in your specific area of research, as well as in a broader context.

Pre-Writing Questions For the Discussion Section

- What is the relationship between these results and the original question in the Introduction section?

- How do your results compare with those of previous research? Are they supportive, extending, or contradictory to existing knowledge?

- What is the potential impact of your findings on theory, practice, or policy in your field?

- Are there any strengths or weaknesses in your study design, methods, or analysis? Can these factors affect how you interpret your results?

- Based on your findings, what are the next steps or directions for research? Have you got any new questions or hypotheses?

Before the Introduction section, and after the Results section.

Based on the pre-writing questions, five main elements can help you structure your Discussion section paragraph by paragraph:

- Summary : Restate your research question/problem and summarize your major findings.

- Interpretations : Identify patterns, contextualize your findings, explain unexpected results, and discuss if and how your results satisfied your hypotheses.

- Implications: Explore if your findings challenge or support existing research, share new insights, and discuss the consequences in theory or practice.

- Limitations : Acknowledge what your results couldn’t achieve because of research design or methodological choices.

- Recommendations : Give concrete ideas about how further research can be conducted to explore new avenues in your field of study.

Dos and Don’ts For the Discussion Section

Aritra Chatterjee , a licensed clinical psychologist and published mental health researcher, advises, “If your findings are not what you expected, disclose this honestly. That’s what good research is about.”

7. Acknowledgments

Expresses gratitude to mentors, colleagues, and funding sources who’ve helped your research.

Write this section after all the parts of IMRaD are done to reflect on your research journey without getting distracted midway.

After a lot of scientific writing, you might get stumped trying to write a few lines to say thanks. Don’t let this be the reason for a late or no-submission.

Wordtune can make a rough draft for you.

All you then have to do is edit the AI-generated content to suit your voice, and replace any text placeholders as needed:

8. References