Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society Essay

Key concepts, works cited.

Living in the modern world people live in the consumer society. To get a closer understanding of the notion ‘consumer society’, people should pay attention to the life style they follow. Having a lot of different goods at the market, people consume those and buy more and more other goods. One of the main characteristic features of a consumer society is that while consuming different products people do not do it independently, in vacuum.

People are inevitable participants of the consumer society, as buying products they want to buy more and more other related or dependant ones. For example, when people buy a toothbrush, they are unable to use it isolated from other objects, they need toothpaste to get the highest effect from the bought product. The same is about other products, buying some goods, people always want to buy more.

Ideology is a notion which may refer to different spheres of human life. One of the broadest meanings of this notion is the way people think. Ideology is not just the ideas people have in their minds in the relation to one specific problem. Ideology is a set of rules and norms people live with. People should not confuse ideology and culture as these are two absolutely different notions. Culture is an objective notion which just exists in the society.

Culture is created out of traditions which have been formulating for many years. Ideology is a personal subjective treatment of the surrounding world, the attitude to each other and the desire to show a piece of a picture as a whole. Ideology tends to make complex notions simple. Propaganda is one of the sides of ideology, as its main idea is the conviction of other people that his way of thinking is the only correct.

Semiotics is a notion which is aimed at exploring different signs and symbols. One of the best practical applications of semiotics is the creation of different planned or constructed languages. Living in the modern world, it is impossible to imagine contemporary life without computers.

Programming languages are an inevitable part of any computer program and software. Being divided into different branches, semiotics studies different qualities of sign systems, the relation between signs and symbols and their meaning, the connection between symbols their interpretation. Speech and language are the main objects of research in semiotics.

Envy, Desire and Belonging in Advertising

Envy, desire and belonging in advertising are the notions which can exist only in the consumer society. When people watch advertising they want what they see. The feeling of desire may be provoked by a number of reasons. It is not a problem when people want what they see because they need it, advertisement just helps them choose a brand. The problem appears when people want to buy a product because they envy those who possess it.

This is called an advertising belonging. No matter whether people need this product or not, they will surely buy it as their desire to possess the thing others have is too big. All these notions, envy, desire and belonging in advertising are closely related. To become free from advertising belonging, people should either stop envy those who has an opportunity to belong a specific product or should enclose themselves from the desire to buy it.

Introduction

There are a number of different definitions of mass culture, and depending on the stress the author makes in his/her definition, this notion have either positive or negative connotation. Having referred a contemporary culture to both mass and popular, it is possible to compare and contrast these two different opinions.

On the one hand, “mass culture is not and can never be good” (Macdonald 43), on the other hand, being mass, “popular culture is linked, for so long, to questions or tradition, of traditional form of life” (Hall 442). Thus, identifying the notion of contemporary culture, we have faced the problem whether to consider it as a positive or a negative issue.

To answer the question whether mass and popular cultures are the elements of contemporary culture and whether they are identified as positive or negative phenomena, we are going to consider different opinions and key arguments offer by the following thinkers, Stuart Hall, F.R. Levis, Dwight Macdonald, and Raymond Williams.

“Mass Culture Is not and Can Never Be Good”

Having stated this idea, Macdonald strictly supports it with the arguments. He is sure that a culture is something individual, which is created by and provided for a human being. Mass use of culture eliminates the very idea of individuality that makes this notion lose its primary meaning.

The following idea is used in support, “a large quantity of people [are] unable to express themselves as human beings because they are related to one another neither as individuals nor as members of communities – indeed, they are not related to each other at all, but only as something distant, abstract, nonhuman”( Macdonald 43).

Looking at the problem from this angle, it is possible to agree with Macdonald, but to investigate the truth, it is important to check the meaning of the word ‘culture’ to make sure that the author considers it in a proper way. Reading an essay by Raymond Williams who tries to explore the origin and etymology of the words ‘culture’ and ‘mass’, many different definitions of the word ‘culture’ was identified. But, there was not mentioned that culture means individual expression or a possession to a specific human being.

Moreover, Raymond underlines that the variations of whatever kind of the word ’culture’ “necessarily involve alternative views of the activities, relationships, and processes which this complex word indicates” (Raymond 28). Thus, the word culture does not mean a specific characteristic of one particular person, it is a set of issues which characterizes a group of people.

The Benefits of Mass Culture

According to Hall, popular culture has a positive connotation as it reflects traditions people have. To make the discussion clear, popular culture is a mass culture, as “the things are said to be ‘popular’ because masses of people listen to them, buy them, read them, consume them, and seem to enjoy them to the full” (Hall 446). The main idea of this opinion is that if the culture is mass and people like it, it is popular and there is no need to speak about negative connotation of mass culture.

But, Levis tries to contradict this point of view by means of providing some negative effect of such mass popular culture. It is not a secret that culture changes.

The changes which occur in the society may be too fast and people may not even notice those, but, if too look at the problem broadly, it can be easily noticed that parents are unable to understand their children, “generations find it hard to adjust themselves to each other, and parents are helpless to deal with their children” (Levis 34). Thus, the generations which are so close have different cultures.

The inability to have an individual or at least family culture leads to misunderstanding and conflicts. Hall can contradict this opinion stating that it is not the culture which changes and makes people become different, it is the change in the relationships. Culture changes when a specific tradition becomes dominant over another one. He states that “almost all cultural forms will be contradictory in this sense, composed of antagonistic and unstable elements” (Hall 449).

Contemporary Culture as Mass and Popular One: Personal Opinion

Having considered an opinion of different thinkers on the problem devoted to culture and its essence, I came to the conclusion that contemporary culture is a mass popular culture which denotes the present ideology of people. Thus, I definitely disagree with Macdonald and his point of view that “mass culture is not and can never be good” (Macdonald 43).

The problem of likes and having a personal opinion appears in the frames of this issue. Living in the age of mass entertainment, some people still manage to appreciate high and avant-garde culture.

So, it may be concluded that popular culture in the contemporary world is more than just an opinion of the vast majority of people, being interesting to a limited group of people, a specific culture may be popular as well. It is not the opinion of a separate individual, so it is also mass. Being in demand among a group of people, it is considered to be popular and mass. Mass in this meaning may denote something revolutionary and opposite (Williams 32).

Turning to the personal opinion, I mostly agree with Hall who states that popular culture is a mass one which expresses the ideas of people who consume the cultural products. Culture should be and is referred to the tradition. It can be even stated that culture and tradition are interconnected notions which should always come together. Still, I also agree with Levis, who highlights that culture is in crisis now (34), thus it is impossible to discuss this problem.

One may state that culture and tradition are not related as there are numerous directions in the modern culture of one specific nation. A close consideration of this problem allows us state that the culture of one specific nation is changing by means of influence and domination of different streams, but still, there is always something traditional in ach new trend which makes this very culture related to the national tradition of people.

In conclusion, contemporary culture is both mass and popular as the characteristic features of these notions coincide with the understanding of the modern culture. I strongly believe that culture should be connected with traditions as only in this way each nations will remain particular and unique. Cultural and traditional features are the most characteristic for describing different nations.

Hall, Stuart. “Notes on deconstructing ‘the popular.” Cultural theory and popular culture: a reader . Ed. John Storey. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 1998. 442-453. Print.

Levis, F.R. “Mass Civilisation and Minority Culture.” Popular culture: a reader . Eds. Raiford Guins, and Omayra Zaragoza Cruz. New York: SAGE, 2005. 33-38. Print.

Macdonald, Dwight. “A theory of mass culture.” Popular culture: a reader . Eds. Raiford Guins, and Omayra Zaragoza Cruz. New York: SAGE, 2005. 39-46. Print.

Williams, Raymond. “’Culture’ and ‘Masses’.” Popular culture: a reader . Eds. Raiford Guins, and Omayra Zaragoza Cruz. New York: SAGE, 2005. 25-32. Print.

- Ralph Lauren's Printed Advertising: Semiotic Analysis

- Semiotics in the Arab-Israeli Confrontation

- The Semiotics of Advertising

- "The McDonaldization thesis: Is expansion inevitable?” by George Ritzer

- The Veil and Muslim: How the Veil Became the Symbol of Muslim Civilization and What the Veil Meant to Islamic Reformists

- Abortion and the Aspects of Pro-Abortion

- Moral Issues in the Abortion

- Smoking and Adolescents

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, September 5). Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society. https://ivypanda.com/essays/consumer-society/

"Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society." IvyPanda , 5 Sept. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/consumer-society/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society'. 5 September.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society." September 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/consumer-society/.

1. IvyPanda . "Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society." September 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/consumer-society/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Concept of Consumer Society in Modern Society." September 5, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/consumer-society/.

Why do we buy what we buy?

A sociologist on why people buy too many things.

If you buy something from a Vox link, Vox Media may earn a commission. See our ethics statement.

by Emily Stewart

What’s at the root of modern American consumerism? It might not just be competition among the brands trying to sell us things, but also competition among ourselves.

An easy story to tell is that marketers and advertisers have perfected tactics to convince us to purchase things, some we need, some we don’t. And it’s an important part of the country’s capitalistic, growth-centered economy: The more people spend, the logic goes, the better it is for everybody. (Never mind that they’re sometimes spending money they don’t have, or the implications of all this production and trash for the planet.) People, naturally, want things.

But American consumerism is also built on societal factors that are often overlooked. We have a social impetus to “keep up with the Joneses,” whoever our own version of the Joneses is. And in an increasingly unequal society, the Joneses at the very top are doing a lot of the consuming, while the people at the bottom struggle to keep up or, ultimately, are left fighting for scraps.

I recently spoke with Juliet Schor, a sociologist at Boston College, about the history of modern American consumerism — what it’s rooted in, how it’s evolved, and how different groups of people have experienced it. Schor, who is the author of books on consumerism, wealth, and spending, has a bit of a unique view on the matter. She tends to focus on the roles of work, inequality, and social pressures in determining what people buy and when. In her view, marketers have less to do with what we want than, say, our neighbors, coworkers, or the people we follow on social media.

Our conversation, edited for length and clarity, is below.

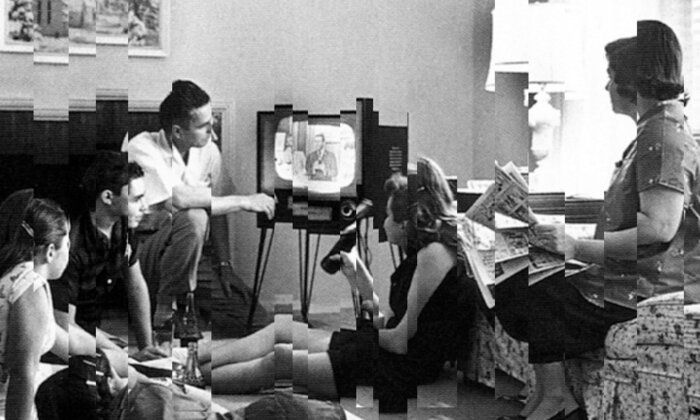

When I think of the beginning of what I perceive as modern American consumerism, I tend to go back to the 1950s and post-World War II, people moving to the suburbs in the cookie-cutter homes. But is that the right place to start?

Scholars differ on how to date consumerism. I would say we need to go back a bit earlier to the 1920s, which is when you get the development of mass production, which is what makes mass consumption possible. This perspective differentiates the 20th century from the earlier period, in which you have shopping and you have consumer fads. But what changes beginning in the 1920s is that the production technologies make it possible to produce things cheaply enough that eventually you can get a majority of the population consuming them.

All-Consuming

The acquisition of stuff looms large in the American imagination. What is life under consumerism doing to us?

Read more from The Goods’ series .

In addition to the things that are happening in factories, the automobile is the leading industry where you move from stationary production to a moving assembly line and big declines in costs. You also have the beginnings of the modern advertising industry and the beginnings of consumer credit.

Then it stalls out, of course, because of the Depression and the war. What happens in the 1950s is the model gets picked up again, this time with major participation by the federal government to spur housing, road building, the auto industry, education, and income. We get into durable goods and household appliances. As we know, that’s really confined to white people post-war.

I imagine it’s changed across the decades, but why do we buy things, often more than we need?

Scholars have different answers to this question. Economists just assume that goods and services provide well-being, and people want to maximize their well-being. Psychologists root it in universal dimensions of human nature, which some of them tie back to evolutionary dynamics. I don’t think either of those are particularly convincing.

The key impetus for contemporary consumer society has been the growth of inequality, the existence of unequal social structures, and the role that consumption came to play in establishing people’s position in that unequal hierarchy. For many people, it’s about consuming to their social position, and trying to keep up with their social position.

The Joneses at the very top are doing a lot of the consuming, while the people at the bottom struggle to keep up

It’s not necessarily experienced by people in that way — it’s experienced more as identity or natural desire. But I think our social and cultural context naturalizes that desire for us.

If you think about the particular things people want, it mostly has to do with being the kind of person that they think they are because there’s a consumption style connected with that. The role of what are called reference groups — the people we compare ourselves to, the people we identify with — is really key in that. It’s why, for example, I’ve found that people who have reference groups that are wealthier than they are tend to save less and spend more, and people who keep more modest reference groups, even as they gain in income and wealth, tend to save more.

Increases in inequality trigger what I’ve called “ competitive consumption ,” [the idea that we spend because we’re comparing ourselves with our peers and what they’re spending]. It can be hard to keep up, particularly if standards are escalating rapidly, as we’ve seen.

I want to dig into this idea of competitive consumption. How are we competing with each other to consume?

We have a society which is structured so that social esteem or value is connected to what we can consume. And so the inability to consume affects the kind of social value that we have. Money displayed in terms of consumer goods just becomes a measure of worth, and that’s really important to people.

How do we pick our “reference groups” if it’s not necessarily by wealth?

We don’t know too much about it. The argument that I made in [my book] The Overspent American was that in the postwar period, we had residentially-based reference groups. So it was really your neighborhood. People moved to the suburbs, and they interacted with people in the suburbs. Those were reference groups of people of similar economic standing because housing is the biggest thing that people buy, and houses tend to cost the same amount roughly within a neighborhood. Family and friends and social networks have always been really important.

Then the next big thing that happens is that you get more and more married women going into the workforce. That really changes reference groups, because they go from a flat social structure in the suburbs to a hierarchy in the workplace, particularly if you’re talking about better-remunerated work and white-collar work. People interact with people above and below them in the hierarchy. So people were exposed to the lifestyles of the people above them in the informal socialization that goes on in the workplace.

Then there is the impact of media, and increasingly now, social media. It’s the friends that you don’t actually know, the Friends on TV.

“Everybody they know is getting a house, and then they think, ‘Okay, am I just going to be a renter?’”

The reference groups change under different socioeconomic dynamics, but it mostly has to do with who you’re in contact with — what you’re seeing in front of you, so your neighbors, your coworkers, what you’re seeing on TV, in movies, on social media.

I think the key point here that differentiates this approach from that of many people who think about consumption is that it is not saying that it’s primarily driven by advertising. It’s not a process of creating desire where it didn’t exist. Critics of advertising say it’s just making people want stuff they don’t need and doesn’t have value to them. And you have to think, “Okay, why do they keep doing that? Why do they keep falling for the advertisements?” Many of the things that people desperately want are not particularly advertised. My approach is rooted in really deep social logic.

It can be very rational and compelling for people to do something that in the end doesn’t necessarily make them all that better off but that failing to do requires really a major effort and going against the social grain in a very big way.

People aren’t buying a house because they saw a commercial for it.

Exactly. It’s because their sibling got one and their best friend got one. Everybody they know is getting a house, and then they think, “Okay, am I just going to be a renter?”

How has the role of women evolved in consumerism? Women are often driving what to buy, right?

Men still dominate in certain kinds of purchases, and particularly the big ones. Women were responsible for everyday purchasing: food and apparel and things like that. There’s that old binary that “men produce, women consume,” which comes out of the differences in roles we have in our economy to a certain extent.

It’s fascinating, though, because I did some work trying to estimate models of differences between men and women and various kinds of consumption, and I never found any gender differences. But if you are looking at data from marketers, you see a disproportionate amount of spending done by women.

What about Black Americans? You alluded to this earlier, but they were at least left out of the ’50s version of consumerism.

The literature on Black Americans’ consumption is not large. If you look at it as a whole, you get a couple of things.

The biggest takeaway is that Black consumers are not that different from white consumers. Now, they do spend on different things, but it’s not like there are two types of consumers, whites and Blacks, and they have different orientations and dynamics. You have differences that are occasioned by some of the dynamics of structural racism — for example, the lower rates of Black homeownership. You’ve got some particular things that you see in part due to the high urban population. Urban dwellers spend more on shoes because they walk a lot more.

You have dynamics among Black consumers that are driven in part by racism. So, for example, sartorial choices in which middle-class and upper-middle-class Black people will have to spend more on their wardrobes in order to avoid being stigmatized in retail settings, the so-called “shopping while Black phenomenon.” Cassi Pittman Claytor, a sociologist at Case Reserve Western University, wrote a wonderful dissertation [ now a book ] on middle-class and upper-class Black people in New York City, and one chapter is on the shopping while Black question. Some of the consumption choices are driven by the attempts to manage racism and stigma in the workplace and outside of it.

Another important phenomenon around the racial discourse in consumption goes back to the period of enslavement of Black Americans in which consumption was a prohibited activity. You see the linkages from the period of enslavement where you’ve got white moralistic discourses against consumption [by] African Americans. A lot of this is in the context of poverty and poor Black people, and the illegitimacy of their consumption choices. And that’s still present today. It’s a really pernicious line of discourse back to enslavement and the ways in which whites attempted to control consumption [by] enslaved people.

What about anti-consumerism? How has that evolved, the people who try to reject consumerism?

There’s a long history of consumer rejectors. You have it in the 19th century as well, and often these were religious groups or sects of people who went into intentional communities, like the Shakers.

Sign up for the Vox Culture newslett er

Each week we’ll send you the very best from the Vox Culture team, plus a special internet culture edition by Rebecca Jennings on Wednesdays. Sign up here .

To me what’s interesting about anti-consumerist movements of the current period is that there’s a certain kind of mainstreaming going on of them. They’re growing. My work is focused on the connections between work choices and consumer choices. So with downshifters, these are people who made decisions to work less and consume less, and it was often the decisions around work that were driving them. Many of them were not people who wanted to consume less in and of itself, but they wanted to take control of their time. And they were willing to make that trade-off.

You do have this minimalist movement now where the stuff is first, though it has a whole story around not getting tied to a burnout job. It’s connected with financial independence and this big “FIRE” movement — financial independence, retire early — and that’s really mainstream. It has much less of a countercultural aspect of it.

You’ve got people coming from the ecological side of things, like buy-nothing groups, and some of these are really big now. They have an ethic of anti-consumerism.

What we’re not sure about is how much participating in one of these actually reduces people’s consumption of new items. But people who participate in buy-nothing groups, most of them don’t buy nothing.

Has the conversation around consumerism and the environment picked up? Should we be talking about consumerism more in the context of saving the planet?

I think we should, and there are two parts to it. One is consuming differently, and the other is not consuming as much. So, volume and composition. To meet climate targets, we need to do both.

There are also issues of inequality of consumption. Look at the inequalities of income and wealth, which have led to these really gross disparities — the excess consumption of people at the top and the deprivation of huge numbers of people both domestically and abroad. It’s not just the bottom, it’s a big swath of the population that doesn’t have enough. So the distribution of consumption is really key, and a lot of the discourse around climate ignored that for a long time. The Green New Deal really put it at the center — it doesn’t lead with a critique of consumerism by any means, but it’s about meeting people’s needs and equity. It has a lot of implications about how we live.

“From 1991 to 2007, the number of pieces of apparel people were buying went from 34 to 67. That number hasn’t budged in 10 years.”

The climate situation does compel us to look differently. In Plenitude: The New Economics of True Wealth , a book I wrote which is now 10 years old, one of the things I looked at was the volume of consumption of consumer goods over the decade before the crash [ahead of the Great Recession]. There was a massive speedup in what I call the cycle of acquisition and discard, just the volume of things people were buying. The fast fashion model that we saw in apparel happened in all sorts of other items, too.

The crash led to a hangover in which you haven’t seen that acceleration again, but it was just a period that showed how dysfunctional the consumer system has become.

Did the Great Recession change how we’re behaving and what we’re buying?

It really slowed down that cycle of acquisition and discard. From 1991 to 2007, the number of pieces of apparel people were buying, on average, went from 34 pieces of new apparel a year to 67. That number hasn’t really budged in the last 10 years.

We haven’t had a massive discontinuity in how the consumption system is operating, but people had less money. And that’s part of the rejecter dynamic — when it’s more difficult for people to participate in that system, either because of its growing cost or their own incomes stagnating, they are likelier to reject it.

It will be interesting to see whether there are any wider impacts of Covid and the fact that people lived with not much more than basic necessities for a while. My own view is that the work patterns are really key in driving consumption. The standard economic view is that it’s the consumer decisions and desires that drive work patterns, and I don’t think that’s the way it works. I think that work patterns actually end up driving consumption.

People make decisions about work, and the hours of work and the incomes associated with them are fixed with the decision. In general, if I decide to take my job as a professor, it has a salary that goes with it, and then that’s what drives my consumption decisions because it drives my income.

If I can’t work this hard anymore, I’m going to go part-time and my income gets cut in half, then I have to adjust my consumption. And that’s not to say it doesn’t go in the other direction — if I want to buy a house, I am going to work some more. But this is my analysis of how the work and spending sides fit together, which is that the work side is a little more dominant.

So we are entering a moment where lots of people have been sitting at home for a year and a half, and as you said, there’s a lot of pent-up demand. Plenty of people I know are ready to spend. Is it odd that we’re responding to the end of a crisis by spending money?

We’re just talking about the people who have it. One of the things about the pandemic is that it made the inequalities in income and spending power more visible to many Americans.

You had so many people who just were struggling through the pandemic to meet basic needs. If you think of that as a working-class phenomenon, you also had this middle-class phenomenon of people whose salaries continued. They were stuck in their houses, so the money was coming into their bank accounts every month and they didn’t have much to spend it on at all. There are people with considerable disposable income right now. We’re going to see a burst of spending now, and we’ll see how long it lasts.

Most Popular

Massive invasive snakes are on the loose and spreading in puerto rico, “everyone is absolutely terrified”: inside a us ally’s secret war on its american critics, leaked openai documents reveal aggressive tactics toward former employees, take a mental break with the newest vox crossword, the misleading, wasteful way we measure gas mileage, explained, today, explained.

Understand the world with a daily explainer plus the most compelling stories of the day.

More in Money

Why are Americans spending so much?

The unionization fight is coming to the South

Why can’t prices just stay the same?

Meme stocks like GameStop are soaring like it’s 2021

How a bunch of Redditors made GameStop’s stock soar

What a Zoom cashier 8,000 miles away can tell us about the future of work

The double sexism of ChatGPT’s flirty “Her” voice

Dopamine, explained

How worried should we be about Russia putting a nuke in space?

Why ICC arrest warrants matter, even if Israel and Hamas leaders evade them

A Brief History of Consumer Culture

The notion of human beings as consumers first took shape before World War I, but became commonplace in America in the 1920s. Consumption is now frequently seen as our principal role in the world.

People, of course, have always “consumed” the necessities of life — food, shelter, clothing — and have always had to work to get them or have others work for them, but there was little economic motive for increased consumption among the mass of people before the 20th century.

Quite the reverse: Frugality and thrift were more appropriate to situations where survival rations were not guaranteed. Attempts to promote new fashions, harness the “propulsive power of envy,” and boost sales multiplied in Britain in the late 18th century. Here began the “slow unleashing of the acquisitive instincts,” write historians Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J.H. Plumb in their influential book on the commercialization of 18th-century England, when the pursuit of opulence and display first extended beyond the very rich.

But, while poorer people might have acquired a very few useful household items — a skillet, perhaps, or an iron pot — the sumptuous clothing, furniture, and pottery of the era were still confined to a very small population. In late 19th-century Britain a variety of foods became accessible to the average person, who would previously have lived on bread and potatoes — consumption beyond mere subsistence. This improvement in food variety did not extend durable items to the mass of people, however. The proliferating shops and department stores of that period served only a restricted population of urban middle-class people in Europe, but the display of tempting products in shops in daily public view was greatly extended — and display was a key element in the fostering of fashion and envy.

Although the period after World War II is often identified as the beginning of the immense eruption of consumption across the industrialized world, the historian William Leach locates its roots in the United States around the turn of the century.

In the United States, existing shops were rapidly extended through the 1890s, mail-order shopping surged, and the new century saw massive multistory department stores covering millions of acres of selling space. Retailing was already passing decisively from small shopkeepers to corporate giants who had access to investment bankers and drew on assembly-line production of commodities, powered by fossil fuels; the traditional objective of making products for their self-evident usefulness was displaced by the goal of profit and the need for a machinery of enticement.

“The cardinal features of this culture were acquisition and consumption as the means of achieving happiness; the cult of the new; the democratization of desire; and money value as the predominant measure of all value in society,” Leach writes in his 1993 book “ Land of Desire: Merchants, Power, and the Rise of a New American Culture .” Significantly, it was individual desire that was democratized, rather than wealth or political and economic power.

The 1920s: “The New Economic Gospel of Consumption”

Release from the perils of famine and premature starvation was in place for most people in the industrialized world soon after the Great War ended. U.S. production was more than 12 times greater in 1920 than in 1860, while the population over the same period had increased by only a factor of three, suggesting just how much additional wealth was theoretically available. The labor struggles of the 19th century had, without jeopardizing the burgeoning productivity, gradually eroded the seven-day week of 14- and 16-hour days that was worked at the beginning of the Industrial Revolution in England. In the United States in particular, economic growth had succeeded in providing basic security to the great majority of an entire population.

It would be feasible to reduce hours of work and release workers for the pleasurable activities of free time with families and communities, but business did not support such a trajectory.

In these circumstances, there was a social choice to be made. A steady-state economy capable of meeting the basic needs of all, foreshadowed by philosopher and political economist John Stuart Mill as the stationary state , seemed well within reach and, in Mill’s words, likely to be an improvement on “the trampling, crushing, elbowing and treading on each other’s heels … the disagreeable symptoms of one of the phases of industrial progress.” It would be feasible to reduce hours of work further and release workers for the spiritual and pleasurable activities of free time with families and communities, and creative or educational pursuits. But business did not support such a trajectory, and it was not until the Great Depression that hours were reduced, in response to overwhelming levels of unemployment.

In 1930 the U.S. cereal manufacturer Kellogg adopted a six-hour shift to help accommodate unemployed workers, and other forms of work-sharing became more widespread. Although the shorter workweek appealed to Kellogg’s workers, the company, after reverting to longer hours during World War II, was reluctant to renew the six-hour shift in 1945. Workers voted for it by three-to-one in both 1945 and 1946, suggesting that, at the time, they still found life in their communities more attractive than consumer goods. This was particularly true of women. Kellogg, however, gradually overcame the resistance of its workers and whittled away at the short shifts until the last of them were abolished in 1985.

Even if a shorter working day became an acceptable strategy during the Great Depression, the economic system’s orientation toward profit and its bias toward growth made such a trajectory unpalatable to most captains of industry and the economists who theorized their successes. If profit and growth were lagging, the system needed new impetus. The short depression of 1921–1922 led businessmen and economists in the United States to fear that the immense productive powers created over the previous century had grown sufficiently to meet the basic needs of the entire population and had probably triggered a permanent crisis of overproduction; prospects for further economic expansion were thought to look bleak.

The historian Benjamin Hunnicutt, who examined the mainstream press of the 1920s, along with the publications of corporations, business organizations, and government inquiries, found extensive evidence that such fears were widespread in business circles during the 1920s. Victor Cutter, president of the United Fruit Company, exemplified the concern when he wrote in 1927 that the greatest economic problem of the day was the lack of “consuming power” in relation to the prodigious powers of production.

“Unless [the consumer] could be persuaded to buy and buy lavishly, the whole stream of six-cylinder cars, super heterodynes, cigarettes, rouge compacts and electric ice boxes would be dammed up at its outlets.”

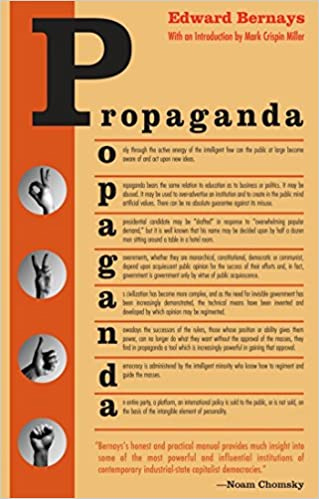

Notwithstanding the panic and pessimism, a consumer solution was simultaneously emerging. As the popular historian of the time Frederick Allen wrote , “Business had learned as never before the importance of the ultimate consumer. Unless he could be persuaded to buy and buy lavishly, the whole stream of six-cylinder cars, super heterodynes, cigarettes, rouge compacts and electric ice boxes would be dammed up at its outlets.” In his classic 1928 book “ Propaganda ,” Edward Bernays, one of the pioneers of the public relations industry, put it this way:

Mass production is profitable only if its rhythm can be maintained—that is if it can continue to sell its product in steady or increasing quantity.… Today supply must actively seek to create its corresponding demand … [and] cannot afford to wait until the public asks for its product; it must maintain constant touch, through advertising and propaganda … to assure itself the continuous demand which alone will make its costly plant profitable.

Edward Cowdrick, an economist who advised corporations on their management and industrial relations policies, called it “the new economic gospel of consumption,” in which workers (people for whom durable possessions had rarely been a possibility) could be educated in the new “skills of consumption.”

It was an idea also put forward by the new “consumption economists” such as Hazel Kyrk and Theresa McMahon, and eagerly embraced by many business leaders. New needs would be created, with advertising brought into play to “augment and accelerate” the process. People would be encouraged to give up thrift and husbandry, to value goods over free time. Kyrk argued for ever-increasing aspirations: “a high standard of living must be dynamic, a progressive standard,” where envy of those just above oneself in the social order incited consumption and fueled economic growth.

President Herbert Hoover’s 1929 Committee on Recent Economic Changes welcomed the demonstration “on a grand scale [of] the expansibility of human wants and desires,” hailed an “almost insatiable appetite for goods and services,” and envisaged “a boundless field before us … new wants that make way endlessly for newer wants, as fast as they are satisfied.” In this paradigm, people are encouraged to board an escalator of desires (a stairway to heaven, perhaps) and progressively ascend to what were once the luxuries of the affluent.

Charles Kettering, general director of General Motors Research Laboratories, equated such perpetual change with progress. In a 1929 article called “Keep the Consumer Dissatisfied,” he stated that “there is no place anyone can sit and rest in an industrial situation. It is a question of change, change all the time — and it is always going to be that way because the world only goes along one road, the road of progress.” These views parallel political economist Joseph Schumpeter’s later characterization of capitalism as “creative destruction”:

Capitalism, then, is by nature a form or method of economic change and not only never is, but never can be stationary .… The fundamental impulse that sets and keeps the capitalist engine in motion comes from the new consumers, goods, the new methods of production or transportation, the new markets, the new forms of industrial organization that capitalist enterprise creates.

The prospect of ever-extendable consumer desire, characterized as “progress,” promised a new way forward for modern manufacture, a means to perpetuate economic growth. Progress was about the endless replacement of old needs with new, old products with new. Notions of meeting everyone’s needs with an adequate level of production did not feature.

The nonsettler European colonies were not regarded as viable venues for these new markets, since centuries of exploitation and impoverishment meant that few people there were able to pay. In the 1920s, the target consumer market to be nourished lay at home in the industrialized world. There, especially in the United States, consumption continued to expand through the 1920s, though truncated by the Great Depression of 1929.

Electrification was crucial for the consumption of the new types of durable items, and the fraction of U.S. households with electricity connected nearly doubled between 1921 and 1929, from 35 percent to 68 percent; a rapid proliferation of radios, vacuum cleaners, and refrigerators followed. Motor car registration rose from eight million in 1920 to more than 28 million by 1929. The introduction of time payment arrangements facilitated the extension of such buying further and further down the economic ladder. In Australia, too, the trend could be observed; there, however, the base was tiny, and even though car ownership multiplied nearly fivefold in the eight years to 1929, few working-class households possessed cars or large appliances before 1945.

The prospect of ever-extendable consumer desire, characterized as “progress,” promised a new way forward for modern manufacture, a means to perpetuate economic growth.

This first wave of consumerism was short-lived. Predicated on debt, it took place in an economy mired in speculation and risky borrowing. U.S. consumer credit rose to $7 billion in the 1920s, with banks engaged in reckless lending of all kinds. Indeed, though a lot less in gross terms than the burden of debt in the United States in late 2008, which Sydney economist Steve Keen has described as “the biggest load of unsuccessful gambling in history,” the debt of the 1920s was very large, over 200 percent of the GDP of the time. In both eras, borrowed money bought unprecedented quantities of material goods on time payment and (these days) credit cards. The 1920s bonanza collapsed suddenly and catastrophically. In 2008, a similar unraveling began; its implications still remain unknown. In the case of the Great Depression of the 1930s, a war economy followed, so it was almost 20 years before mass consumption resumed any role in economic life — or in the way the economy was conceived.

The Second Wave

Once World War II was over, consumer culture took off again throughout the developed world, partly fueled by the deprivation of the Great Depression and the rationing of the wartime years and incited with renewed zeal by corporate advertisers using debt facilities and the new medium of television. Stuart Ewen, in his history of the public relations industry, saw the birth of commercial radio in 1921 as a vital tool in the great wave of debt-financed consumption in the 1920s — “a privately owned utility, pumping information and entertainment into people’s homes.”

“Requiring no significant degree of literacy on the part of its audience,” Ewen writes, “radio gave interested corporations … unprecedented access to the inner sanctums of the public mind.” The advent of television greatly magnified the potential impact of advertisers’ messages, exploiting image and symbol far more adeptly than print and radio had been able to do. The stage was set for the democratization of luxury on a scale hitherto unimagined.

Though the television sets that carried the advertising into people’s homes after World War II were new, and were far more powerful vehicles of persuasion than radio had been, the theory and methods were the same — perfected in the 1920s by PR experts like Bernays. Vance Packard echoes both Bernays and the consumption economists of the 1920s in his description of the role of the advertising men of the 1950s:

They want to put some sizzle into their messages by stirring up our status consciousness.… Many of the products they are trying to sell have, in the past, been confined to a “quality market.” The products have been the luxuries of the upper classes. The game is to make them the necessities of all classes . This is done by dangling the products before non-upper-class people as status symbols of a higher class. By striving to buy the product—say, wall-to-wall carpeting on instalment—the consumer is made to feel he is upgrading himself socially.

Though it is status that is being sold, it is endless material objects that are being consumed.

In a little-known 1958 essay reflecting on the conservation implications of the conspicuously wasteful U.S. consumer binge after World War II, John Kenneth Galbraith pointed to the possibility that this “gargantuan and growing appetite” might need to be curtailed. “What of the appetite itself?,” he asks. “Surely this is the ultimate source of the problem. If it continues its geometric course, will it not one day have to be restrained? Yet in the literature of the resource problem this is the forbidden question.”

“We need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate,” retail analyst Victor Lebow remarked in 1955.

Galbraith quotes the President’s Materials Policy Commission setting out its premise that economic growth is sacrosanct. “First we share the belief of the American people in the principle of Growth,” the report maintains, specifically endorsing “ever more luxurious standards of consumption.” To Galbraith, who had just published “ The Affluent Society ,” the wastefulness he observed seemed foolhardy, but he was pessimistic about curtailment; he identified the beginnings of “a massive conservative reaction to the idea of enlarged social guidance and control of economic activity,” a backlash against the state taking responsibility for social direction. At the same time he was well aware of the role of advertising: “Goods are plentiful. Demand for them must be elaborately contrived,” he wrote. “Those who create wants rank amongst our most talented and highly paid citizens. Want creation — advertising — is a ten billion dollar industry.”

Or, as retail analyst Victor Lebow remarked in 1955:

Our enormously productive economy demands that we make consumption our way of life, that we convert the buying and use of goods into rituals, that we seek our spiritual satisfaction, our ego satisfaction, in consumption.… We need things consumed, burned up, replaced and discarded at an ever-accelerating rate.

Thus, just as immense effort was being devoted to persuading people to buy things they did not actually need, manufacturers also began the intentional design of inferior items, which came to be known as “planned obsolescence.” In his second major critique of the culture of consumption, “ The Waste Makers ,” Packard identified both functional obsolescence, in which the product wears out quickly and psychological obsolescence, in which products are “designed to become obsolete in the mind of the consumer, even sooner than the components used to make them will fail.”

Galbraith was alert to the way that rapidly expanding consumption patterns were multiplied by a rapidly expanding population. But postwar industrial enterprise stoked the expansion nonetheless. The rise of consumer debt, interrupted in 1929, also resumed. In Australia, the 1939 debt of AU$39 million doubled in the first two years after the war and, by 1960, had grown by a factor of 25, to more than AU$1 billion dollars. This new burst in debt-financed consumerism was, again, incited intentionally.

Tapping into the Unconscious: Image and Message

In researching his excellent history of the rise of PR, Ewen interviewed Bernays himself in 1990, not long before he turned 99. Ewen found Bernays, a key pioneer of the new PR profession, to be just as candid about his underlying motivations as he had been in 1928 when he wrote “Propaganda”:

Throughout our conversation, Bernays conveyed his hallucination of democracy: A highly educated class of opinion-molding tacticians is continuously at work … adjusting the mental scenery from which the public mind, with its limited intellect, derives its opinions.… Throughout the interview, he described PR as a response to a transhistoric concern: the requirement, for those people in power, to shape the attitudes of the general population.

Bernays’s views, like those of several other analysts of the “crowd” and the “herd instinct,” were a product of the panic created among the elite classes by the early 20th-century transition from the limited franchise of propertied men to universal suffrage. “On every side of American life, whether political, industrial, social, religious or scientific, the increasing pressure of public judgment has made itself felt,” Bernays wrote. “The great corporation which is in danger of having its profits taxed away or its sales fall off or its freedom impeded by legislative action must have recourse to the public to combat successfully these menaces.”

The opening page of “Propaganda” discloses his solution:

The conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country.… It is they who pull the wires which control the public mind, who harness old social forces and contrive new ways to bind and guide the world.

The front-line thinkers of the emerging advertising and public relations industries turned to the key insights of Sigmund Freud, Bernays’s uncle. As Bernays noted:

Many of man’s thoughts and actions are compensatory substitutes for desires which [he] has been obliged to suppress. A thing may be desired, not for its intrinsic worth or usefulness, but because he has unconsciously come to see in it a symbol of something else, the desire for which he is ashamed to admit to himself … because it is a symbol of social position, an evidence of his success.

Bernays saw himself as a “propaganda specialist,” a “public relations counsel,” and PR as a more sophisticated craft than advertising as such; it was directed at hidden desires and subconscious urges of which its targets would be unaware. Bernays and his colleagues were anxious to offer their services to corporations and were instrumental in founding an entire industry that has since operated along these lines, selling not only corporate commodities but also opinions on a great range of social, political, economic, and environmental issues.

Though it has become fashionable in recent decades to brand scholars and academics as elites who pour scorn on ordinary people, Bernays and the sociologist Gustave Le Bon were long ago arguing, on behalf of business and political elites, respectively, that the mass of people are incapable of thought.

According to Le Bon, “A crowd thinks in images, and the image itself immediately calls up a series of other images, having no logical connection with the first”; crowds “can only comprehend rough-and-ready associations of ideas,” leading to “the utter powerlessness of reasoning when it has to fight against sentiment.” Bernays and his PR colleagues believed ordinary people to be incapable of logical thought, let alone mastery of “abstruse economic, political and ethical data,” and saw the need to “control and regiment the masses according to our will without their knowing about it”; PR could thus ensure the maintenance of order and corporate control in society.

Bernays and his PR colleagues believed ordinary people to be incapable of logical thought, let alone mastery of “abstruse economic, political and ethical data.”

The commodification of reality and the manufacture of demand have had serious implications for the construction of human beings in the late 20th century, where, to quote philosopher Herbert Marcuse, “people recognize themselves in their commodities.” Marcuse’s critique of needs, made more than 50 years ago, was not directed at the issues of scarce resources or ecological waste, although he was aware even at that time that Marx was insufficiently critical of the continuum of progress and that there needed to be “a restoration of nature after the horrors of capitalist industrialisation have been done away with.”

Marcuse directed his critique at the way people, in the act of satisfying our aspirations, reproduce dependence on the very exploitive apparatus that perpetuates our servitude. Hours of work in the United States have been growing since 1950, along with a doubling of consumption per capita between 1950 and 1990. Marcuse suggested that this “voluntary servitude (voluntary inasmuch as it is introjected into the individual) … can be broken only through a political practice which reaches the roots of containment and contentment in the infrastructure of man [ sic ], a political practice of methodical disengagement from and refusal of the Establishment, aiming at a radical transvaluation of values.”

The difficult challenge posed by such a transvaluation is reflected in current attitudes. The Australian comedian Wendy Harmer in her 2008 ABC TV series called “Stuff” expressed irritation at suggestions that consumption is simply generated out of greed or lack of awareness:

I am very proud to have made a documentary about consumption that does not contain the usual footage of factory smokestacks, landfill tips and bulging supermarket trolleys. Instead, it features many happy human faces and all their wonderful stuff! It’s a study of a love affair as much as anything else.

In the same vein, during the Q&A after a talk given by the Australian economist Clive Hamilton at the 2006 Byron Bay Writers’ Festival, one woman spoke up about her partner’s priorities: Rather than entertain questions about any impact his possessions might be having on the environment, she said, he was determined to “go down with his gadgets.”

The capitalist system, dependent on a logic of never-ending growth from its earliest inception, confronted the plenty it created in its home states, especially the United States, as a threat to its very existence. It would not do if people were content because they felt they had enough. However over the course of the 20th century, capitalism preserved its momentum by molding the ordinary person into a consumer with an unquenchable thirst for its “wonderful stuff.”

Kerryn Higgs is an Australian writer and historian. She is the author of “ Collision Course: Endless Growth on a Finite Planet ,” from which this article is adapted.

How Humans Became 'Consumers': A History

Until the 19th century, hardly anyone recognized the vital role everyday buyers play in the world economy.

“Consumption is the sole end and purpose of all production,” Adam Smith confidently announced in The Wealth of Nations in 1776. Smith’s quote is famous, but in reality this was one of the few times he explicitly addressed the topic. Consumption is conspicuous by its absence in The Wealth of Nations , and neither Smith nor his immediate pupils treated it as a separate branch of political economy.

It was in an earlier work, 1759’s The Theory of Moral Sentiments , that Smith put his finger on the social and psychological impulses that push people to accumulate objects and gadgets. People, he observed, were stuffing their pockets with “little conveniences,” and then buying coats with more pockets to carry even more. By themselves, tweezer cases, elaborate snuff boxes, and other “baubles” might not have much use. But, Smith pointed out, what mattered was that people looked at them as “means of happiness." It was in people’s imagination that these objects became part of a harmonious system and made the pleasures of wealth “grand and beautiful and noble."

This moral assessment was a giant step towards a more sophisticated understanding of consumption, for it challenged the dominant negative mindset that went back to the ancients. From Plato in ancient Greece to St. Augustine and the Christian fathers to writers in the Italian Renaissance, thinkers routinely condemned the pursuit of things as wicked and dangerous because it corrupted the human soul, destroyed republics, and overthrew the social order. The splendour of luxus , the Latin word for “luxury,” smacked of luxuria —excess and lechery.

The term “consumption” itself entered circulation with a heavy burden. It originally derived from the Latin word consumere and found its way first into French in the 12th century, and from there into English and later into other European languages. It meant the using up of food, candles, and other resources. (The body, too, could be consumed, in this sense—this is why in English, the “wasting disease,” tuberculosis, was called “consumption.") To complicate matters, there was the similar-sounding Latin word consummare , as in Christ’s last words on the cross: “ Consummatum est ,” meaning “It is finished." The word came to mean using up, wasting away, and finishing.

Perhaps those meanings informed the way that many pre-modern governments regulated citizens’ consumption. Between the 14th and 18th centuries, most European states (and their American colonies) rolled out an ever longer list of “sumptuary laws” to try and stem the tide of fashion and fineries. The Venetian senate stipulated in 1512 that no more than six forks and six spoons could be given as wedding gifts; gilded chests and mirrors were completely forbidden. Two centuries later, in German states, women were fined or thrown in jail for sporting a cotton neckerchief.

To rulers and moralists, such a punitive, restrictive view of the world of goods made eminent sense. Their societies lived with limited money and resources in an era before sustained growth. Money spent on a novelty item from afar, such as Indian cotton, was money lost to the local treasury and to local producers; those producers, and the land they owned, were heralded as sources of strength and virtue. Consumers, by contrast, were seen as fickle and a drain on wealth.

Adam Smith’s reappraisal of this group in 1776 came in the midst of a transformation that was as much material as it was cultural. Between the 15th and 18th centuries, the world of goods was expanding in dramatic and unprecedented ways, and it was not a phenomenon confined to Europe. Late Ming China enjoyed a golden age of commerce that brought a profusion of porcelain cups, lacquerware, and books. In Renaissance Italy, it was not only the palazzi of the elite but the homes of artisans that were filling up with more and more clothing, furniture, and tableware, even paintings and musical instruments.

It was in Holland and Britain, though, where the momentum became self-sustaining. In China, goods had been prized for their antiquity; in Italy, a lot of them had circulated as gifts or stored wealth. The Dutch and English, by contrast, put a new premium on novelties such as Indian cottons, exotic goods like tea and coffee, and new products like the gadgets that caught Smith’s attention.

In the 1630s, the Dutch polymath Caspar Barlaeus praised trade for teaching people to appreciate new things, and such secular arguments for the introduction of new consumer products—whether through innovation or importation—were reinforced by religious ones. Would God have created a world rich in minerals and exotic plants, if He had not wanted people to discover and exploit them? The divine had furnished man with a “multiplicity of desires” for a reason, wrote Robert Boyle, the scientist famous for his experiments with gases. Instead of leading people astray from the true Christian path, the pursuit of new objects and desires was now justified as acting out God’s will. In the mid-18th century, Smith’s close friend David Hume completed the defense of moderate luxury. Far from being wasteful or ruining a community, it came to be seen as making nations richer, more civilized, and stronger.

By the late 18th century, then, there were in circulation many of the moral and analytical ingredients for a more positive theory of consumption. But the French Revolution and the subsequent reaction stopped them from coming together. For many radicals and conservatives alike, the revolution was a dangerous warning that excess and high living had eaten away at social virtues and stability. Austerity and a new simple life were held up as answers.

Moreover, economic writers at the time did not dream there could be something like sustained growth. Hence consumption could easily be treated as a destructive act that used up resources or at best redistributed them. Even when writers were feeling their way towards the idea of a higher standard of living for all, they did not yet talk of different groups of people as "consumers." One reason was that, unlike today, they did not yet single out the goods and services that households purchased, but often also included industrial uses of resources under the rubric of consumption.The French economist Jean-Baptiste Say—today remembered for Say’s law, which states that supply creates its own demand—was one of the few writers in the early 19th century who considered consumption on its own, according the topic a special section in his Treatise on Political Economy . Interestingly, he included the “reproductive consumption” of coal, wood, metal, and other goods used in factories alongside the private end-use by customers.

Elsewhere, other economists showed little interest in devising a unified theory of consumption. As the leading public moralist in Victorian England and a champion of the weak and vulnerable, John Stuart Mill naturally stood up for the protection of unorganized consumers against the interests of organized monopolies. In his professional writings, however, consumption got short shrift. Mill even denied that it might be a worthy branch of economic analysis: “We know not of any laws of the consumption of wealth as the subject of a distinct science," he declared in 1844. “They can be no other than the laws of human enjoyment." Anyone pitching a distinct analysis of consumption was guilty by association of believing in the possibility of “under-consumption," an idea that to Mill was suspect, wrong, and dangerous.

It fell to a popular French liberal and writer, Frédéric Bastiat, to champion the consumer—supposedly his dying words in 1850 were “We must learn to look at everything from the point of view of the consumer." That may have sounded prescient but it hardly qualified as a theory, since Bastiat believed that free markets ultimately took care of everything. For someone like Mill with a concern for social justice and situations when markets did not function, such laissez-faire dogma was bad politics just as much as bad economics.

By the middle of the 19th century, then, there was a curious mismatch between material and intellectual trends. Consumer markets had expanded enormously in the previous two centuries. In economics, by contrast, the consumer was still a marginal figure who mainly caught attention in situations of market failure, such as when urban utilities failed or cheated their customers, but rarely attracted it when it came to the increasingly important role they’d play in the expansion of modern economies.

Theory finally caught up in 1871, when William Stanley Jevons published his Theory of Political Economy . “The theory of economics," he wrote, “must begin with a correct theory of consumption.” Mill and his ilk had it completely wrong, he argued. For them the value of goods was a function of their cost, such as the cloth and sweat that went into making a coat. Jevons looked at the matter from the other end. Value was created by the consumer, not the producer: The value of the coat depended on how much a person desired it.

Further, that desire was not fixed but varied, and depended on a product’s utility function. Goods had a “final (or marginal) utility," where each additional portion had less utility than the one before, because the final one was less intensely desired, a foundational economic concept that can be understood intuitively through cake: The first slice may taste wonderful, but queasiness tends to come after the third or fourth. Carl Menger in Austria and Léon Walras in Switzerland were developing similar ideas at around the same time. Together, those two and Jevons put the study of consumption and economics on entirely new foundations. Marginalism was born, and the utility of any given good could now be measured as a mathematical function.

It was Alfred Marshall who built on these foundations and, in the 1890s, turned economics into a proper discipline at the University of Cambridge. Jevons, he noted, was absolutely right: The consumer was the “ultimate regulator of demand." But he considered Jevons’s focus on wants was too static. Wants, Marshall wrote, are “the rulers of life among lower animals” and human life was distinguished by “changing forms of efforts and activities”—he contested that needs and desires changed over time, and so did the attempts and means devoted to satisfying them. People, he believed, had a natural urge for self-improvement and, over time, moved from drink and idleness to physical exercise, travel, and an appreciation of the arts.

For Marshall, the history of civilization resembled a ladder on which people climbed towards higher tastes and activities. It was a very Victorian view of human nature. And it reflected a deep ambivalence towards the world of goods that he shared with such critics of mass production like the designer William Morris and the art critic John Ruskin. Marshall believed fervently in social reform and a higher standard of living for all. But at the same time, he was also deeply critical of standardized mass consumption. His hope was that people in the future would learn instead to “buy a few things made well by highly paid labour rather than many made badly by low paid labour." In this way, the refinement of consumers’ taste would benefit highly-skilled workers.

The growing attention to consumption was not limited to liberal England. In imperial Germany, national economists turned to it as an indicator of national strength: Nations with high demand were also the most energetic and powerful, it was argued. The first general account of a high-consumption society, however, came not surprisingly from the country with the highest standard of living: the United States. In 1889, Simon Patten, the chair of the Wharton School of Business, announced that the country had entered a “new order of consumption." For the first time, there was a society that was no longer fixated on physical survival but that now enjoyed a surplus of wealth and could think about what to do with it. The central question became how Americans spent their money and their time, as well as how much they earned. People, Patten wrote, had a right to leisure. The task ahead was no longer telling people to restrain themselves—to save or to put on a hairshirt—but to develop habits for greater pleasure and welfare.

This was more than an academic viewpoint. It had radical implications for how people should consume and think about money and their future. Patten summarised the new morality of consumption for a congregation in a Philadelphia church in 1913:

I tell my students to spend all that they have and borrow more and spend that … It is no evidence of loose morality when a stenographer, earning eight or ten dollars a week, appears dressed in clothing that takes nearly all of her earnings to buy.

Quite the contrary, he said, it was “a sign of her growing moral development.” It showed her employer that she was ambitious. Patten added that a “well-dressed working girl … is the backbone of many a happy home that is prospering under the influence that she is exerting over the household.” Some members at the Unitarian Church were outraged, insisting, “The generation you’re talking to now is too deep in crime and ignorance … to heed you.” Discipline, not spending on credit, was what they needed. Whether they liked it or not, the future would be with Patten’s more liberal, generous view of consumption.

Economists were not the only ones who discovered consumption in the late 19th century. They were part of a larger movement that included states, social reformers, and consumers themselves. These were years when steamships, trade, and imperial expansion accelerated globalization and many workers in industrial societies started to benefit from cheaper and more varied food and clothing. Attention now turned to “standard of living," a new concept that launched thousands of investigations into household budgets from Boston to Berlin and Bombay.

The central idea behind these inquiries was that the welfare and happiness of a household was determined by habits of spending, and not just earnings. A better understanding of how money was spent assisted social reformers in teaching the art of prudent budgeting. In France in the 1840s, Frédéric Le Play compiled 36 volumes on the budgets of European workers. In the next generation, his student Ernst Engel took the method to Saxony and Prussia, where he professionalized the study of social statistics. He fathered Engel’s law, which held that the greater a family’s income, the smaller the proportion of income spent on food. For those of Engel’s contemporaries who worried about revolutions and socialism, there was hope here: Less spending on food translated into more money for personal improvement and social peace.

Above all, it was citizens and subjects who discovered their voice as consumers. Today, the fin-de-siècle is remembered for its cathedrals of consumption, epitomized by the Bon Marché in Paris and Selfridges in London. While they did not invent the art of shopping, these commercial temples were important in widening the public profile and spaces for shoppers, especially for women.

Intriguingly, though, it was not there in the glitzy galleries but literally underground, through the new material networks of gas and water, that people first came together collectively as consumers. A Water Consumers’ Association was launched in Sheffield in 1871 in protest against water taxes. In addition, needs and wants themselves were changing, and this expanded notions of entitlements and rights. In England, middle-class residents at this time were becoming accustomed to having a bath and refused to pay “extra” charges for their extra water. A bath was a necessity, not a luxury, they argued, so they organized a consumer boycott.

The years before the First World War turned into the golden years of consumer politics. By 1910, most working-class families and every fourth household in England was a member of a consumer cooperative. In Germany and France, such groups counted over a million members. In Britain, the Woman’s Cooperative Guild was the largest women’s movement at the time. Organizing as consumers gave women a new public voice and visibility; after all, it was the “women with the baskets”, as these working-class housewives were called, who did the shopping.

And it was women who marched in the vanguard of ethical consumerism. Consumer leagues sprang up in New York, Paris, Antwerp, Rome, and Berlin. In the United States, the league grew into a national federation with 15,000 activists, headed by Florence Kelley, whose Quaker aunt had campaigned against slave-grown goods. These middle-class consumers used the power of their purses to target sweatshops and reward businesses that offered decent working conditions and a minimum wage.

“The consumer,” a German activist explained, “is the clock which regulates the relationship between employer and employee.” If the clock was driven by “selfishness, self-interest, thoughtlessness, greed and avarice, thousands of our fellow beings have to live in misery and depression.” If, on the other hand, consumers thought about the workers behind the product, they advanced social welfare and harmony. Consumers, in other words, were asked to be citizens. For women, this new role as civic-minded consumers became a powerful weapon in the battle for the vote. This call on the “citizen-consumer” reached its apotheosis in Britain on the eve of the First World War in the popular campaigns for free trade, when millions rallied in defense of the consumer interest as the public interest.

Even before these movements took shape, many advocates had predicted a steady advance of consumer power throughout the 1900s. “The 19th century has been the century of producers," Charles Gide, the French political economist and a champion of consumer cooperatives, told his students in 1898. “Let us hope that the 20th century will be that of consumers. May their kingdom come!”

Did Gide’s hope come true? Looking back from the early 21st century, it would be foolish not to recognize the enormous gains in consumer welfare and consumer protection that have taken place in the course of the last century, epitomized by John F. Kennedy’s Consumer Bill of Rights in 1962. Cars no longer explode on impact. Food scandals and frauds continue but are a far cry from the endemic scandals of adulteration that scarred the Victorians.

And consumers have remained a focus of academics. Economists continue to debate whether people adjust their consumption over time to get most out of life , whether they spend depending on what they expect to earn in the future , or whether their spending is determined more by how their income compares to others’ . Consumption is still an integral component of college curricula, and not only in economics and business, but in sociology, anthropology, and history, too, although the last few tend to stress culture, social customs, and habits rather than choice and the utility-maximizing individual.

Today, companies and marketers follow consumers as much as direct them. Grand critiques of consumerism as stupefying, dehumanizing, or alienating—still an essential part of the intellectual furniture of the 1960s—have had their wings clipped by a recognition of how products and fashions can provide identities, pleasure, and fodder for entirely new cultural styles. Younger generations in particular have created their own subcultures, from the Mods and rockers in Western Europe in the 1960s to Gothic Lolitas in Japan more recently. Rather than being passive, the consumer is now celebrated for actively adding value and meaning to media and products.

And yet, in other respects, today’s economies are a long way from Gide’s kingdom of consumers. Consumer associations and activism continue, but they have become dispersed between so many issues that they no longer carry the punch of the social-reform campaigns of the early 20th century; today there are, for example, movements for slow food, organic food, local food, fair-trade food—even ethical dog food.

In hard times, like the First and Second World Wars, some countries introduced consumer councils and ministries, but that was because states had a temporary interest in organizing their purchasing power for war efforts and to recruit them in the fight against profiteering and inflation. During peacetime, markets and vocal business lobbies returned, and such consumer bodies were just as quickly wound up again. Welfare states and social services have taken over many of the causes for which consumer leagues fought a century ago. India has a small Ministry of Consumer Affairs, but its primary role is to raise awareness and fight unfair practices. In many less developed countries, consumers continue to be a vocal political force in battles over access and prices of water and energy. In the richest societies today, though, consumers have little or no organized political voice, and the great campaigns for direct consumer representation four or five generations ago have come to very little. Markets, choice, and competition are now seen to be the consumer’s best friend—not political representation. Consumers are simultaneously more powerful and powerless today than Gide had foreseen.

Today, climate change makes the future role of consumption increasingly uncertain. The 1990s gave birth to the idea of sustainable consumption, a commitment championed by the United Nations in Rio de Janeiro in 1992. Price incentives and more-efficient technologies, it was hoped, would enable consumers to lighten the material footprint of their lifestyles. Since then, there have been many prophecies and headlines that predict “peak stuff” and the end of consumerism. People in affluent societies, they say, have become bored with owning lots stuff. They prefer experiences instead or are happy sharing. Dematerialization will follow.

Such forecasts sound nice but they fail to stand up to the evidence. After all, a lot of consumption in the past was also driven by experiences, such as the delights of pleasure gardens, bazaars, and amusement parks. In the world economy today, services might be growing faster than goods, but that does not mean the number of containers is declining—far from it. And, of course, the service economy is not virtual, and requires material resources too. In France in 2014, people drove 32 billion miles to do their shopping—that involves a lot of rubber, tarmac, and gas. Digital computing and WiFi absorb a growing share of electricity. Sharing platforms like Airbnb have likely increased frequent travel and flights, not reduced them.

Moreover, people may say they feel overwhelmed or depressed by their possessions but in most cases this has not converted them to living more simply. Nor is this a peculiarly American or Anglo-Saxon problem. In 2011, the people of Stockholm bought three times more clothing and appliances than they did 20 years earlier.