Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper

Definition and Purpose of Abstracts

An abstract is a short summary of your (published or unpublished) research paper, usually about a paragraph (c. 6-7 sentences, 150-250 words) long. A well-written abstract serves multiple purposes:

- an abstract lets readers get the gist or essence of your paper or article quickly, in order to decide whether to read the full paper;

- an abstract prepares readers to follow the detailed information, analyses, and arguments in your full paper;

- and, later, an abstract helps readers remember key points from your paper.

It’s also worth remembering that search engines and bibliographic databases use abstracts, as well as the title, to identify key terms for indexing your published paper. So what you include in your abstract and in your title are crucial for helping other researchers find your paper or article.

If you are writing an abstract for a course paper, your professor may give you specific guidelines for what to include and how to organize your abstract. Similarly, academic journals often have specific requirements for abstracts. So in addition to following the advice on this page, you should be sure to look for and follow any guidelines from the course or journal you’re writing for.

The Contents of an Abstract

Abstracts contain most of the following kinds of information in brief form. The body of your paper will, of course, develop and explain these ideas much more fully. As you will see in the samples below, the proportion of your abstract that you devote to each kind of information—and the sequence of that information—will vary, depending on the nature and genre of the paper that you are summarizing in your abstract. And in some cases, some of this information is implied, rather than stated explicitly. The Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , which is widely used in the social sciences, gives specific guidelines for what to include in the abstract for different kinds of papers—for empirical studies, literature reviews or meta-analyses, theoretical papers, methodological papers, and case studies.

Here are the typical kinds of information found in most abstracts:

- the context or background information for your research; the general topic under study; the specific topic of your research

- the central questions or statement of the problem your research addresses

- what’s already known about this question, what previous research has done or shown

- the main reason(s) , the exigency, the rationale , the goals for your research—Why is it important to address these questions? Are you, for example, examining a new topic? Why is that topic worth examining? Are you filling a gap in previous research? Applying new methods to take a fresh look at existing ideas or data? Resolving a dispute within the literature in your field? . . .

- your research and/or analytical methods

- your main findings , results , or arguments

- the significance or implications of your findings or arguments.

Your abstract should be intelligible on its own, without a reader’s having to read your entire paper. And in an abstract, you usually do not cite references—most of your abstract will describe what you have studied in your research and what you have found and what you argue in your paper. In the body of your paper, you will cite the specific literature that informs your research.

When to Write Your Abstract

Although you might be tempted to write your abstract first because it will appear as the very first part of your paper, it’s a good idea to wait to write your abstract until after you’ve drafted your full paper, so that you know what you’re summarizing.

What follows are some sample abstracts in published papers or articles, all written by faculty at UW-Madison who come from a variety of disciplines. We have annotated these samples to help you see the work that these authors are doing within their abstracts.

Choosing Verb Tenses within Your Abstract

The social science sample (Sample 1) below uses the present tense to describe general facts and interpretations that have been and are currently true, including the prevailing explanation for the social phenomenon under study. That abstract also uses the present tense to describe the methods, the findings, the arguments, and the implications of the findings from their new research study. The authors use the past tense to describe previous research.

The humanities sample (Sample 2) below uses the past tense to describe completed events in the past (the texts created in the pulp fiction industry in the 1970s and 80s) and uses the present tense to describe what is happening in those texts, to explain the significance or meaning of those texts, and to describe the arguments presented in the article.

The science samples (Samples 3 and 4) below use the past tense to describe what previous research studies have done and the research the authors have conducted, the methods they have followed, and what they have found. In their rationale or justification for their research (what remains to be done), they use the present tense. They also use the present tense to introduce their study (in Sample 3, “Here we report . . .”) and to explain the significance of their study (In Sample 3, This reprogramming . . . “provides a scalable cell source for. . .”).

Sample Abstract 1

From the social sciences.

Reporting new findings about the reasons for increasing economic homogamy among spouses

Gonalons-Pons, Pilar, and Christine R. Schwartz. “Trends in Economic Homogamy: Changes in Assortative Mating or the Division of Labor in Marriage?” Demography , vol. 54, no. 3, 2017, pp. 985-1005.

![undergraduate research abstract examples “The growing economic resemblance of spouses has contributed to rising inequality by increasing the number of couples in which there are two high- or two low-earning partners. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the topic under study (the “economic resemblance of spouses”). This sentence also implies the question underlying this research study: what are the various causes—and the interrelationships among them—for this trend?] The dominant explanation for this trend is increased assortative mating. Previous research has primarily relied on cross-sectional data and thus has been unable to disentangle changes in assortative mating from changes in the division of spouses’ paid labor—a potentially key mechanism given the dramatic rise in wives’ labor supply. [Annotation for the previous two sentences: These next two sentences explain what previous research has demonstrated. By pointing out the limitations in the methods that were used in previous studies, they also provide a rationale for new research.] We use data from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) to decompose the increase in the correlation between spouses’ earnings and its contribution to inequality between 1970 and 2013 into parts due to (a) changes in assortative mating, and (b) changes in the division of paid labor. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The data, research and analytical methods used in this new study.] Contrary to what has often been assumed, the rise of economic homogamy and its contribution to inequality is largely attributable to changes in the division of paid labor rather than changes in sorting on earnings or earnings potential. Our findings indicate that the rise of economic homogamy cannot be explained by hypotheses centered on meeting and matching opportunities, and they show where in this process inequality is generated and where it is not.” (p. 985) [Annotation for the previous two sentences: The major findings from and implications and significance of this study.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-1.png)

Sample Abstract 2

From the humanities.

Analyzing underground pulp fiction publications in Tanzania, this article makes an argument about the cultural significance of those publications

Emily Callaci. “Street Textuality: Socialism, Masculinity, and Urban Belonging in Tanzania’s Pulp Fiction Publishing Industry, 1975-1985.” Comparative Studies in Society and History , vol. 59, no. 1, 2017, pp. 183-210.

![undergraduate research abstract examples “From the mid-1970s through the mid-1980s, a network of young urban migrant men created an underground pulp fiction publishing industry in the city of Dar es Salaam. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence introduces the context for this research and announces the topic under study.] As texts that were produced in the underground economy of a city whose trajectory was increasingly charted outside of formalized planning and investment, these novellas reveal more than their narrative content alone. These texts were active components in the urban social worlds of the young men who produced them. They reveal a mode of urbanism otherwise obscured by narratives of decolonization, in which urban belonging was constituted less by national citizenship than by the construction of social networks, economic connections, and the crafting of reputations. This article argues that pulp fiction novellas of socialist era Dar es Salaam are artifacts of emergent forms of male sociability and mobility. In printing fictional stories about urban life on pilfered paper and ink, and distributing their texts through informal channels, these writers not only described urban communities, reputations, and networks, but also actually created them.” (p. 210) [Annotation for the previous sentences: The remaining sentences in this abstract interweave other essential information for an abstract for this article. The implied research questions: What do these texts mean? What is their historical and cultural significance, produced at this time, in this location, by these authors? The argument and the significance of this analysis in microcosm: these texts “reveal a mode or urbanism otherwise obscured . . .”; and “This article argues that pulp fiction novellas. . . .” This section also implies what previous historical research has obscured. And through the details in its argumentative claims, this section of the abstract implies the kinds of methods the author has used to interpret the novellas and the concepts under study (e.g., male sociability and mobility, urban communities, reputations, network. . . ).]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-2.png)

Sample Abstract/Summary 3

From the sciences.

Reporting a new method for reprogramming adult mouse fibroblasts into induced cardiac progenitor cells

Lalit, Pratik A., Max R. Salick, Daryl O. Nelson, Jayne M. Squirrell, Christina M. Shafer, Neel G. Patel, Imaan Saeed, Eric G. Schmuck, Yogananda S. Markandeya, Rachel Wong, Martin R. Lea, Kevin W. Eliceiri, Timothy A. Hacker, Wendy C. Crone, Michael Kyba, Daniel J. Garry, Ron Stewart, James A. Thomson, Karen M. Downs, Gary E. Lyons, and Timothy J. Kamp. “Lineage Reprogramming of Fibroblasts into Proliferative Induced Cardiac Progenitor Cells by Defined Factors.” Cell Stem Cell , vol. 18, 2016, pp. 354-367.

![undergraduate research abstract examples “Several studies have reported reprogramming of fibroblasts into induced cardiomyocytes; however, reprogramming into proliferative induced cardiac progenitor cells (iCPCs) remains to be accomplished. [Annotation for the previous sentence: The first sentence announces the topic under study, summarizes what’s already known or been accomplished in previous research, and signals the rationale and goals are for the new research and the problem that the new research solves: How can researchers reprogram fibroblasts into iCPCs?] Here we report that a combination of 11 or 5 cardiac factors along with canonical Wnt and JAK/STAT signaling reprogrammed adult mouse cardiac, lung, and tail tip fibroblasts into iCPCs. The iCPCs were cardiac mesoderm-restricted progenitors that could be expanded extensively while maintaining multipo-tency to differentiate into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells in vitro. Moreover, iCPCs injected into the cardiac crescent of mouse embryos differentiated into cardiomyocytes. iCPCs transplanted into the post-myocardial infarction mouse heart improved survival and differentiated into cardiomyocytes, smooth muscle cells, and endothelial cells. [Annotation for the previous four sentences: The methods the researchers developed to achieve their goal and a description of the results.] Lineage reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs provides a scalable cell source for drug discovery, disease modeling, and cardiac regenerative therapy.” (p. 354) [Annotation for the previous sentence: The significance or implications—for drug discovery, disease modeling, and therapy—of this reprogramming of adult somatic cells into iCPCs.]](https://writing.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/535/2019/08/Abstract-3.png)

Sample Abstract 4, a Structured Abstract

Reporting results about the effectiveness of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis, from a rigorously controlled study

Note: This journal requires authors to organize their abstract into four specific sections, with strict word limits. Because the headings for this structured abstract are self-explanatory, we have chosen not to add annotations to this sample abstract.

Wald, Ellen R., David Nash, and Jens Eickhoff. “Effectiveness of Amoxicillin/Clavulanate Potassium in the Treatment of Acute Bacterial Sinusitis in Children.” Pediatrics , vol. 124, no. 1, 2009, pp. 9-15.

“OBJECTIVE: The role of antibiotic therapy in managing acute bacterial sinusitis (ABS) in children is controversial. The purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of high-dose amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate in the treatment of children diagnosed with ABS.

METHODS : This was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Children 1 to 10 years of age with a clinical presentation compatible with ABS were eligible for participation. Patients were stratified according to age (<6 or ≥6 years) and clinical severity and randomly assigned to receive either amoxicillin (90 mg/kg) with potassium clavulanate (6.4 mg/kg) or placebo. A symptom survey was performed on days 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, 7, 10, 20, and 30. Patients were examined on day 14. Children’s conditions were rated as cured, improved, or failed according to scoring rules.

RESULTS: Two thousand one hundred thirty-five children with respiratory complaints were screened for enrollment; 139 (6.5%) had ABS. Fifty-eight patients were enrolled, and 56 were randomly assigned. The mean age was 6630 months. Fifty (89%) patients presented with persistent symptoms, and 6 (11%) presented with nonpersistent symptoms. In 24 (43%) children, the illness was classified as mild, whereas in the remaining 32 (57%) children it was severe. Of the 28 children who received the antibiotic, 14 (50%) were cured, 4 (14%) were improved, 4(14%) experienced treatment failure, and 6 (21%) withdrew. Of the 28children who received placebo, 4 (14%) were cured, 5 (18%) improved, and 19 (68%) experienced treatment failure. Children receiving the antibiotic were more likely to be cured (50% vs 14%) and less likely to have treatment failure (14% vs 68%) than children receiving the placebo.

CONCLUSIONS : ABS is a common complication of viral upper respiratory infections. Amoxicillin/potassium clavulanate results in significantly more cures and fewer failures than placebo, according to parental report of time to resolution.” (9)

Some Excellent Advice about Writing Abstracts for Basic Science Research Papers, by Professor Adriano Aguzzi from the Institute of Neuropathology at the University of Zurich:

Academic and Professional Writing

This is an accordion element with a series of buttons that open and close related content panels.

Analysis Papers

Reading Poetry

A Short Guide to Close Reading for Literary Analysis

Using Literary Quotations

Play Reviews

Writing a Rhetorical Précis to Analyze Nonfiction Texts

Incorporating Interview Data

Grant Proposals

Planning and Writing a Grant Proposal: The Basics

Additional Resources for Grants and Proposal Writing

Job Materials and Application Essays

Writing Personal Statements for Ph.D. Programs

- Before you begin: useful tips for writing your essay

- Guided brainstorming exercises

- Get more help with your essay

- Frequently Asked Questions

Resume Writing Tips

CV Writing Tips

Cover Letters

Business Letters

Proposals and Dissertations

Resources for Proposal Writers

Resources for Dissertators

Research Papers

Planning and Writing Research Papers

Quoting and Paraphrasing

Writing Annotated Bibliographies

Creating Poster Presentations

Thank-You Notes

Advice for Students Writing Thank-You Notes to Donors

Reading for a Review

Critical Reviews

Writing a Review of Literature

Scientific Reports

Scientific Report Format

Sample Lab Assignment

Writing for the Web

Writing an Effective Blog Post

Writing for Social Media: A Guide for Academics

University of Missouri

- Bias Hotline: Report bias incidents

Undergraduate Research

- How to Write An Abstract

Think of your abstract or artist statement like a movie trailer: it should leave the reader eager to learn more but knowledgeable enough to grasp the scope of your work. Although abstracts and artist statements need to contain key information on your project, your title and summary should be understandable to a lay audience.

Please remember that you can seek assistance with any of your writing needs at the MU Writing Center . Their tutors work with students from all disciplines on a wide variety of documents. And they are specially trained to use the Abstract Review Rubric that will be used on the abstracts reviewed at the Spring Forum.

Types of Research Summaries

Students should submit artist statements as their abstracts. Artist statements should introduce to the art, performance, or creative work and include information on media and methods in creating the pieces. The statements should also include a description of the inspiration for the work, the meaning the work signifies to the artist, the artistic influences, and any unique methods used to create the pieces. Students are encouraged to explain the connections of the work with their inspirations or themes. The statements should be specific to the work presented and not a general statements about the students’ artistic philosophies and approaches. Effective artist statements should provide the viewer with information to better understand the work of the artists. If presentations are based on previous performances, then students may include reflections on the performance experiences and audience reactions.

Abstracts should describe the nature of the project or piece (ex: architectural images used for a charrette, fashion plates, advertising campaign story boards) and its intended purpose. Students should describe the project or problem that they addressed and limitations and challenges that impact the design process. Students may wish to include research conducted to provide context for the project and inform the design process. A description of the clients/end users may be included. Information on inspirations, motivations, and influences may also be included as appropriate to the discipline and project. A description of the project outcome should be included.

Abstracts should include a short introduction or background to put the research into context; purpose of the research project; a problem statement or thesis; a brief description of materials, methods, or subjects (as appropriate for the discipline); results and analysis; conclusions and implications; and recommendations. For research projects still in progress at the time of abstract submission, students may opt to indicate that results and conclusions will be presented [at the Forum].

Tips for writing a clear and concise abstract

The title of your abstract/statement/poster should include some language that the lay person can understand. When someone reads your title they should have SOME idea of the nature of your work and your discipline.

Ask a peer unfamiliar with your research to read your abstract. If they’re confused by it, others will be too.

Keep it short and sweet.

- Interesting eye-catching title

- Introduction: 1-3 sentences

- What you did: 1 sentence

- Why you did it: 1 sentence

- How you did it: 1 sentence

- Results or when they are expected: 2 sentences

- Conclusion: 1-3 sentences

Ideas to Address:

- The big picture your project helps tackle

- The problem motivating your work on this particular project

- General methods you used

- Results and/or conclusions

- The next steps for the project

Things to Avoid:

- A long and confusing title

- Jargon or complicated industry terms

- Long description of methods/procedures

- Exaggerating your results

- Exceeding the allowable word limit

- Forgetting to tell people why to care

- References that keep the abstract from being a “stand alone” document

- Being boring, confusing, or unintelligible!

Artist Statement

The artist statement should be an introduction to the art and include information on media and methods in creating the piece(s). It should include a description of the inspiration for the work, what the work signifies to the artist, the artistic influences, and any unique methods used to create the work. Students are encouraged to explain the connections of the work with their inspiration or theme. The artist statement (up to 300 words) should be written in plain language to invite viewers to learn more about the artist’s work and make their own interpretations. The statement should be specific to the piece(s) that will be on display, and not a general statement about the student’s artistic philosophy and approach. An effective artist statement should provide the viewer with information to better understand and experience viewing the work on display.

Research/Applied Design Abstract

The project abstract (up to 300 words) should describe the nature of the project or piece (ex: architectural images used for a charrette, fashion plates, small scale model of a theater set) and its intended purpose. Students should describe the project or problem that was addressed and limitations and challenges that impact the design process. Students may wish to include research conducted to provide context for the project and inform the design process. A description of the clients/end users may be included. Information on inspirations, motivations, and influences may also be included as appropriate to the discipline and project.

Key Considerations

- What is the problem/ big picture that your project helps to address?

- What is the appropriate background to put your project into context? What do we know? What don’t we know? (informed rationale)

- What is YOUR project? What are you seeking to answer?

- How do you DO your research? What kind of data do you collect? How do you collect it?

- What is the experimental design? Number of subjects or tests run? (quantify if you can!)

- Provide some data (not raw, but analyzed)

- What have you found? What are your results? How do you KNOW this – how did you analyze this?

- What does this mean?

- What are the next steps? What don’t we know still?

- How does this relate (again) to the bigger picture. Who should care and why? (what is your audience?)

More Resources

- Abstract Writing Presentation from University of Illinois – Chicago

- Sample Abstracts

- A 10-Step Guide to Make Your Research Paper More Effective

- Your Artist Statement: Explaining the Unexplainable

- How to Write an Artist Statement

Here is the Forum Abstract Review Rubric for you and your mentor to use when writing your abstract to submit to the Spring Research & Creative Achievements Forum.

Let your curiosity lead the way:

Apply Today

- Arts & Sciences

- Graduate Studies in A&S

Writing an Abstract

What is an abstract.

An abstract is a summary of your paper and/or research project. It should be single-spaced, one paragraph, and approximately 250-300 words. It is NOT an introduction to your paper; rather, it should highlight your major points, explain why your work is important, describe how you researched your problem, and offer your conclusions.

How do I prepare an abstract?

An abstract should be clear and concise, without any grammatical mistakes or typographical errors. You may wish to have it reviewed by the Writing Center , who are happy to work with you on your abstract and are available via appointments , as well as a writing instructor, tutor, or other writing specialist.

For the purposes of the symposium, the wording of an abstract should be understandable to a well-read, interdisciplinary audience. Specialized terms should be either defined or avoided.

A successful abstract addresses the following points:

- Problem: What is the central problem or question you investigated?

- Purpose : Why is your study important? How it is different from other similar investigations? Why we should care about your project?

- Methods : What are the important methods you used to perform your research?

- Results : What are the major results of the research project? (You do not have to detail all of the results, highlight only the major ones.)

- Interpretation : How do your results relate back to your central problem?

- Implications : Why are your results important? What can we learn from them?

It should not include any charts, tables, figures, footnotes, references or other supporting information.

Finally, please note that your abstract must have the approval of your research mentor or advisor.

Samples of Abstracts

Browse through past volumes of WUSHTA and WUURD available via WashU Open Scholarship to view samples of abstracts in all disciplines, or take a look at the samples below:

Sample abstract: Social Sciences

Sample abstract: Natural Sciences

Sample abstract: Humanities

- Skip to main navigation

- Skip to main content

College Center for Research and Fellowships

- Our Students, Their Stories

- Research Scholars

- For Students

- Research Grant Programs

- 2024 Undergraduate Research Symposium: Honoring Mentors

Undergraduate Research Symposium: Abstract Writing

- Undergraduate Research Symposium: Research Resource Expo

- Undergraduate Research Symposium: Information for Presenters

- Undergraduate Research Symposium: FAQs

- Past Undergraduate Research Symposium Events

- National Fellowships

- Collegiate Honors & Scholars

- CCRF Seminars: The Common Year

- CCRF General Resources for Students

- CCRF Resources for Faculty & Staff

- Connect with Us

Search form

What is a research abstract?

An abstract is a concise summary of a larger research project. It should address all the major points of the project, providing an overview of the research topic, question, methods, results, and significance. The abstract is a snapshot that captures a reader's attention and--although it can stand alone as a representation of the project--invites readers to learn more by viewing your poster or attending your presentation.

What should a research abstract include?

You will likely want to include:

- Background, context, and purpose (the "big picture" in which your research fits)

- Your question, hypothesis, or goal

- The methods and research design you employed/are employing

- Results, products, outcomes (achieved or anticipated)

- Implications and significance: for your field, for future work, for your viewers

What is the format of a research abstract?

The length and format of research abstracts can vary depending on the requirements of a particular conference or journal.

For the UChicago Undergraduate Research Symposium, the requirements are :

- Include a short, descriptive title, capitalized in title case

- Make it only one paragraph

- Have no section breaks, footnotes, or illustrations

- Adhere to a limit of 300 words.

- Pitch your abstract to an educated non-specialist audience (minimize jargon, spell out acronyms)

Should I show my abstract to my mentor?

YES! It is very important that your faculty mentor review and approve your abstract. Your abstract will be publicly available, so you and your mentor should work together to ensure that the abstract presents your work appropriately and does not raise any intellectual-property concerns. Your mentor will need to approve your abstract in our application system before you can be accepted to present at the Undergraduate Research Symposium.

Will you host abstract writing workshops?

Yes! Abstract workshops are now concluded. View the slides and a recorded workshop in our Resource Library .

Where can I find examples of research abstracts?

You can review abstracts from major conferences or journals in your field to ascertain the conventions of your discipline. You can also review the abstracts from prior Undergraduate Research Symposia to see what your peers have written.

Where do I submit my abstract for the upcoming Undergraduate Research Symposium?

Access the online submission form here .

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 3. The Abstract

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

An abstract summarizes, usually in one paragraph of 300 words or less, the major aspects of the entire paper in a prescribed sequence that includes: 1) the overall purpose of the study and the research problem(s) you investigated; 2) the basic design of the study; 3) major findings or trends found as a result of your analysis; and, 4) a brief summary of your interpretations and conclusions.

Writing an Abstract. The Writing Center. Clarion University, 2009; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century . Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010;

Importance of a Good Abstract

Sometimes your professor will ask you to include an abstract, or general summary of your work, with your research paper. The abstract allows you to elaborate upon each major aspect of the paper and helps readers decide whether they want to read the rest of the paper. Therefore, enough key information [e.g., summary results, observations, trends, etc.] must be included to make the abstract useful to someone who may want to examine your work.

How do you know when you have enough information in your abstract? A simple rule-of-thumb is to imagine that you are another researcher doing a similar study. Then ask yourself: if your abstract was the only part of the paper you could access, would you be happy with the amount of information presented there? Does it tell the whole story about your study? If the answer is "no" then the abstract likely needs to be revised.

Farkas, David K. “A Scheme for Understanding and Writing Summaries.” Technical Communication 67 (August 2020): 45-60; How to Write a Research Abstract. Office of Undergraduate Research. University of Kentucky; Staiger, David L. “What Today’s Students Need to Know about Writing Abstracts.” International Journal of Business Communication January 3 (1966): 29-33; Swales, John M. and Christine B. Feak. Abstracts and the Writing of Abstracts . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2009.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Types of Abstracts

To begin, you need to determine which type of abstract you should include with your paper. There are four general types.

Critical Abstract A critical abstract provides, in addition to describing main findings and information, a judgment or comment about the study’s validity, reliability, or completeness. The researcher evaluates the paper and often compares it with other works on the same subject. Critical abstracts are generally 400-500 words in length due to the additional interpretive commentary. These types of abstracts are used infrequently.

Descriptive Abstract A descriptive abstract indicates the type of information found in the work. It makes no judgments about the work, nor does it provide results or conclusions of the research. It does incorporate key words found in the text and may include the purpose, methods, and scope of the research. Essentially, the descriptive abstract only describes the work being summarized. Some researchers consider it an outline of the work, rather than a summary. Descriptive abstracts are usually very short, 100 words or less. Informative Abstract The majority of abstracts are informative. While they still do not critique or evaluate a work, they do more than describe it. A good informative abstract acts as a surrogate for the work itself. That is, the researcher presents and explains all the main arguments and the important results and evidence in the paper. An informative abstract includes the information that can be found in a descriptive abstract [purpose, methods, scope] but it also includes the results and conclusions of the research and the recommendations of the author. The length varies according to discipline, but an informative abstract is usually no more than 300 words in length.

Highlight Abstract A highlight abstract is specifically written to attract the reader’s attention to the study. No pretense is made of there being either a balanced or complete picture of the paper and, in fact, incomplete and leading remarks may be used to spark the reader’s interest. In that a highlight abstract cannot stand independent of its associated article, it is not a true abstract and, therefore, rarely used in academic writing.

II. Writing Style

Use the active voice when possible , but note that much of your abstract may require passive sentence constructions. Regardless, write your abstract using concise, but complete, sentences. Get to the point quickly and always use the past tense because you are reporting on a study that has been completed.

Abstracts should be formatted as a single paragraph in a block format and with no paragraph indentations. In most cases, the abstract page immediately follows the title page. Do not number the page. Rules set forth in writing manual vary but, in general, you should center the word "Abstract" at the top of the page with double spacing between the heading and the abstract. The final sentences of an abstract concisely summarize your study’s conclusions, implications, or applications to practice and, if appropriate, can be followed by a statement about the need for additional research revealed from the findings.

Composing Your Abstract

Although it is the first section of your paper, the abstract should be written last since it will summarize the contents of your entire paper. A good strategy to begin composing your abstract is to take whole sentences or key phrases from each section of the paper and put them in a sequence that summarizes the contents. Then revise or add connecting phrases or words to make the narrative flow clearly and smoothly. Note that statistical findings should be reported parenthetically [i.e., written in parentheses].

Before handing in your final paper, check to make sure that the information in the abstract completely agrees with what you have written in the paper. Think of the abstract as a sequential set of complete sentences describing the most crucial information using the fewest necessary words. The abstract SHOULD NOT contain:

- A catchy introductory phrase, provocative quote, or other device to grab the reader's attention,

- Lengthy background or contextual information,

- Redundant phrases, unnecessary adverbs and adjectives, and repetitive information;

- Acronyms or abbreviations,

- References to other literature [say something like, "current research shows that..." or "studies have indicated..."],

- Using ellipticals [i.e., ending with "..."] or incomplete sentences,

- Jargon or terms that may be confusing to the reader,

- Citations to other works, and

- Any sort of image, illustration, figure, or table, or references to them.

Abstract. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Abstract. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Abstracts. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Borko, Harold and Seymour Chatman. "Criteria for Acceptable Abstracts: A Survey of Abstracters' Instructions." American Documentation 14 (April 1963): 149-160; Abstracts. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Hartley, James and Lucy Betts. "Common Weaknesses in Traditional Abstracts in the Social Sciences." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (October 2009): 2010-2018; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-first Century. Oxford, UK: Chandos Publishing, 2010; Procter, Margaret. The Abstract. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Riordan, Laura. “Mastering the Art of Abstracts.” The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association 115 (January 2015 ): 41-47; Writing Report Abstracts. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Abstracts. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Koltay, Tibor. Abstracts and Abstracting: A Genre and Set of Skills for the Twenty-First Century . Oxford, UK: 2010; Writing an Abstract for Your Research Paper. The Writing Center, University of Wisconsin, Madison.

Writing Tip

Never Cite Just the Abstract!

Citing to just a journal article's abstract does not confirm for the reader that you have conducted a thorough or reliable review of the literature. If the full-text is not available, go to the USC Libraries main page and enter the title of the article [NOT the title of the journal]. If the Libraries have a subscription to the journal, the article should appear with a link to the full-text or to the journal publisher page where you can get the article. If the article does not appear, try searching Google Scholar using the link on the USC Libraries main page. If you still can't find the article after doing this, contact a librarian or you can request it from our free i nterlibrary loan and document delivery service .

- << Previous: Research Process Video Series

- Next: Executive Summary >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Admission and Aid

- Student Life

Undergraduate Research and Creative Scholarship

Site navigation.

- About OUR@UM

- Getting Started

- Student Resources

- Presenting & Publishing

- Faculty Mentor Award

- Resources for Faculty Mentors

- Appointments

UMCUR Section Sidebar Navigation

- Participation Details

- Important Dates

- Workshops & Resources

- Judges & Volunteers

Sample Abstracts

Sample physical and life sciences abstract.

Do Voles Select Dense Vegetation for Movement Pathways at the Microhabitat Level? Biological Sciences The relationship between habitat use by voles (Rodentia: Microtus) and the density of vegetative cover was studied to determine if voles select forage areas at the microhabitat level. Using live traps, I trapped, powdered, and released voles at 10 sites. At each trap site, I analyzed the type and height of the vegetation in the immediate area. Using a black light, I followed the trails left by powdered voles through the vegetation. I mapped the trails using a compass to ascertain the tortuosity or amount the trail twisted and turned, and visually checked the trails to determine the obstruction of the movement path by vegetation. I also checked vegetative obstruction on 4 random paths near the actual trail, to compare the cover on the trail with other nearby alternative pathways. There was not a statistically significant difference between the amount of cover on a vole trail and the cover off to the sides of the trail when completely covered; there was a significant difference between on and off the trail when the path was completely open. These results indicate that voles are selectively avoiding bare areas, while not choosing among dense patches at a fine microhabitat scale.

Sample Social Science Abstract

Traditional Healers and the HIV Crisis in Africa: Toward an Integrated Approach Anthropology The HIV virus is currently destroying all facets of African life. It, therefore, is imperative that a new holistic form of health education and accessible treatment be implemented in African public health policy which improves dissemination of prevention and treatment programs while maintaining the cultural infrastructure. Drawing on government and NGO reports, as well as other documentary sources, this paper examines the nature of current efforts and the state of health care practices in Africa. I review access to modern health care and factors that inhibit local utilization of these resources, as well as traditional African beliefs about medicine, disease, and healthcare. This review indicates that a collaboration of western and traditional medical care and philosophy can help slow the spread of HIV in Africa. This paper encourages the acceptance and financial support of traditional health practitioners in this effort owing to their accessibility and affordability and their cultural compatibility with the community.

Sample Humanities Abstract

Echoes from the Underground European and American Literature Friedrich Nietzsche notably referred to the Russian novelist Fyodor Dostoevsky as “the only psychologist from whom I have anything to learn.” Dostoevsky’s ability to encapsulate the darkest and most twisted depths of the human psyche within his characters has had a profound impact on those writers operating on the periphery of society. Through research on his writing style, biography, and a close reading of his novel Notes from the Underground I am exploring the impact of his most famous outcast, the Underground Man, on counterculture writers in America during the great subculture upsurge of the 1950s and 60s. Ken Kesey, Allen Ginsberg, and Jack Kerouac employ both the universal themes expressed by the Underground Man as well as more specific stylistic and textual similarities. Through my research, I have drawn parallels between these three writers with respect to their literary works as well as the impact of both their personal lives and the worlds that they inhabit. The paper affirms that Dostoevsky has had a profound influence on the geography of the Underground and that this literary topos has had an impact on the writers who continue to inhabit that space.

Sample Creative Writing Abstract

Passersby Creative Writing Richard Hugo wrote in his book of essays, The Triggering Town , that “knowing can be a limiting thing.” His experiences, however brief, in many of the small towns that pepper Montana’s landscape served as the inspiration to much of his poetry, and his observations came to reveal more of the poet than of the triggering subject. For Hugo, the less he knew of a place, the more he could imagine. My project, “Passersby,” is a short collection of poems and black and white photographs that explore this notion of knowledge and imagination. The place is the triggering subject in “Passersby” and will take the audience or viewer to a variety of national and international locations, from Rome and Paris to Beaver, Utah, and the Oregon Coast, and from there, into an exploration of experience and imagination relished by the poet. Hugo believed that as a writer “you owe reality nothing and the truth about your feelings everything.” While reality will play a role in “Passersby,” this work aims to blur the lines between knowing and imagination in order, perhaps, to find a truer place for the poet.

Sample Visual and Performing Arts Abstract/Artist Statement

The Integration of Historic Periods in Costume Design Theatre As productions turn away from resurrecting museum pieces, integrating costumes from two different historical periods has become more popular. This research project focuses on what makes costume integration successful. A successful integration must be visually compelling, but still, give characters depth and tell the story of the play. By examining several Shakespearean theatre productions, I have pinpointed the key aspects of each costume integration that successfully assist the production. While my own experiences have merged Elizabethan with the 1950s, other designers have merged Elizabethan with contemporary and even a rock concert theme. By analyzing a variety of productions, connecting threads helped establish “rules” for designers.

Through this research, I have established common guidelines for integrating two periods of costume history while still maintaining a strong design that helps tell a story. One method establishes the silhouette of one period while combining the details, such as fabric and accessories, of another period, creating an equal representation of the two. A second option creates a world blended equally of the two periods, in which the design becomes timeless and unique to the world of the play. A third option assigns opposing groups to two different periods, establishing visual conflict. Many more may exist, but the overall key to costume integration is to define how each period is represented. When no rules exist, there is no cohesion of ideas and the audience loses sight of character, story, and concept. Costumes help tell a story, and without guidance, that story is lost.

Sample Journalism Abstracts

International Headlines 3.0: Exploring Youth-Centered Innovation in Global News Delivery Traditional news media must innovate to maintain their ability to inform contemporary audiences. This research project analyzes innovative news outlets that have the potential to draw young audiences to follow global current events. On February 8, 2011, a Pew Research Center Poll found that 52 percent of Americans reported having heard little or nothing about the anti-government protests in Egypt. Egyptians had been protesting for nearly two weeks when this poll was conducted. The lack of knowledge about the protests was not a result of scarce media attention. In the United States, most mainstream TV news sources (CNN, FOX, MSNBC, ABC) ran headline stories on the protests by January 26, one day after the protests began. Sparked by an assignment in International Reporting J450 class, we selected 20 innovative news outlets to investigate whether they are likely to overcome the apparent disinterest of Americans, particularly the youth, in foreign news. Besides testing those news outlets for one week, we explored the coverage and financing of these outlets, and we are communicating with their editors and writers to best understand how and why they publish as they do. We will evaluate them, following a rubric, and categorize them based on their usefulness and effectiveness.

Launch UM virtual tour.

Office of Undergraduate Research

- Office of Undergraduate Research FAQ's

- URSA Engage

- Resources for Students

- Resources for Faculty

- Engaging in Research

- Spring Poster Symposium (SPS)

- Ecampus SPS Videos

- Earn Money by Participating in Research Studies

- Transcript Notation

- Student Publications

How to Write an Abstract

How to write an abstract for a conference, what is an abstract and why is it important, an abstract is a brief summary of your research or creative project, usually about a paragraph long (250-350 words), and is written when you are ready to present your research or included in a thesis or research publication..

For additional support in writing your abstract, you can contact the Office of URSA at [email protected] or schedule a time to meet with a Writing and Research Consultant at the OSU Writing Center

Main Components of an Abstract:

The opening sentences should summarize your topic and describe what researchers already know, with reference to the literature.

A brief discussion that clearly states the purpose of your research or creative project. This should give general background information on your work and allow people from different fields to understand what you are talking about. Use verbs like investigate, analyze, test, etc. to describe how you began your work.

In this section you will be discussing the ways in which your research was performed and the type of tools or methodological techniques you used to conduct your research.

This is where you describe the main findings of your research study and what you have learned. Try to include only the most important findings of your research that will allow the reader to understand your conclusions. If you have not completed the project, talk about your anticipated results and what you expect the outcomes of the study to be.

Significance

This is the final section of your abstract where you summarize the work performed. This is where you also discuss the relevance of your work and how it advances your field and the scientific field in general.

- Your word count for a conference may be limited, so make your abstract as clear and concise as possible.

- Organize it by using good transition words found on the lef so the information flows well.

- Have your abstract proofread and receive feedback from your supervisor, advisor, peers, writing center, or other professors from different disciplines.

- Double-check on the guidelines for your abstract and adhere to any formatting or word count requirements.

- Do not include bibliographic references or footnotes.

- Avoid the overuse of technical terms or jargon.

Feeling stuck? Visit the OSU ScholarsArchive for more abstract examples related to your field

Contact Info

618 Kerr Administration Building Corvallis, OR 97331

541-737-5105

Sample abstracts

Reprocessing used nuclear fuel (UNF) is crucial to the completion of a closed fuel cycle and would reduce the volume of waste produced during nuclear power production. Pyroprocessing is a promising reprocessing technique as it offers pure forms of product recovery. A limiting issue with pyroprocessing, however, is the inability to monitor concentrations of chemical species inside the electrorefiner. As with many nuclear processes, safe guards and monitoring become increasingly important; therefore, development of real - time monitoring techniques for various chemical species may allow for commercialization of this recycling process [1 - 5]. The focus of the proposed research is to develop accurate diffusion coefficients for Yttrium, a fission product found in UNF, in molten salt conditions through Cyclic Voltammetry (CV). Quantification of the diffusion coefficient will allow current measurements from inside the melt to be directly related to species concentration. With the diffusion coefficients, in - situ CV would then facilitate real - time monitoring of chemical concentrations.

This project aims to analyze the social and cultural effects of the Iranian Revolution through primary source material and interviews with those directly affected by the revolution. Iran’s political seclusion and its animosity toward the West has limited the voices and perspectives available to an American audience. Moreover, the attitude of the West towards Iran since the revolution has been myopic and often marred by political perspectives. The objective of this project will be to bring those voices and stories to light, putting a greater focus on the experiences of individuals who lived through the Revolution. These stories will be presented in a digital medium (film and web) in order to bring these voices and perspectives to an American audience.

Undergraduate Research Center

Undergraduate research abstract books:.

Check out these searchable PDF abstracts from our annual undergraduate research conference as this is a great way to see examples of undergraduate research taking place on campus and which faculty have supported undergraduate students in their labs and on their research projects.

2021 Abstract Book

2020 Abstract Book

2019 Abstract Book

2018 Abstract Book

2017 Abstract Book

2016 Abstract Book

2015 Abstract Book

2014 Abstract Book

2013 Abstract Book

2012 Abstract Book

2011 Abstract Book

- Office of Undergraduate Research

- Current Students

- Online Only Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Family

- Alumni & Friends

- Community & Business

- Student Life

- Student Assistants

- Latest News

- What is Research

- Get Started

- First-Year Scholars Program

- Current Research Projects

- Involvement Opportunities

- Undergraduate Research Space

- About to Graduate?

- Find Undergraduate Researchers

- Request a Classroom Visit

- Presenting and Publishing

- Workshops and Training

- Office of Research

How to Write a Research Abstract

Explore the possibilities.

Tuesday October 13, 2020 11:00am - 12:00pm Microsoft Teams Virtual Workshop

An abstract is a shortened version of a research project and is typically required for conference submissions and manuscripts submitted for publication. This workshop is focused on how to write an effective research abstract. Particular emphasis will be on writing abstracts for the National Conference on Undergraduate Research (NCUR), which will be held virtually in April 2021.

Contact Info

Kennesaw Campus 1000 Chastain Road Kennesaw, GA 30144

Marietta Campus 1100 South Marietta Pkwy Marietta, GA 30060

Campus Maps

Phone 470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

kennesaw.edu/info

Media Resources

Resources For

Related Links

- Financial Aid

- Degrees, Majors & Programs

- Job Opportunities

- Campus Security

- Global Education

- Sustainability

- Accessibility

470-KSU-INFO (470-578-4636)

© 2024 Kennesaw State University. All Rights Reserved.

- Privacy Statement

- Accreditation

- Emergency Information

- Report a Concern

- Open Records

- Human Trafficking Notice

Info for Morgan State University

- Future Students

- Current Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Families

- Alumni & Friends

- For the Media

Search Morgan State University

Commonly searched pages.

- Payment Plan

- Housing Application

- Comptroller

- Office of Undergraduate Research

- Spring Into Research Week III

- Award Recipients

- Schedule of Events

- Abstract Submission & Registration Information

- Rules for Abstract Submission

- Abstract Format/ Sample Abstract

- Guest Registration/ Abstract Submission

- Poster and Oral Presentation Guidelines

- Call for Judges

- About the Office

- MSU/PGCC Bridges Program (B2B)

- Research Internships

- The Leadership Alliance

- Research Ambassadors

- Post-baccalaureate Training Opportunities

- OUR Resources

ABSTRACT FORMAT/ SAMPLE ABSTRACT

Abstracts must be submitted as an MS WORD document only.

All WORD documents must be submitted with the following formatted name: Last name_discipline_poster or oral (Example: Brown_biology_poster)

All abstracts must meet formatting requirements (see sample). Abstracts that do not meet all formatting/submission guidelines will not be accepted.

Abstracts must not exceed 250 words, excluding title, authors, and institutions.

Abstracts should be typed, single space in Times New Roman, 11 point font.

Abstract title must be bold and typed in ALL CAPITAL LETTERS.

Authors should be listed as follows: *Joan A. Doe, Thomas T. Smith, and Carl Jones More than one student presenter is allowed for poster presentations. Only one presenter is allowed for oral presentations. (*Indicates the student presenter).

List Department, Institution, City, State, Zip Code as follows: Department of Biology, Morgan State University, Baltimore, MD 21251.

Skip one line, indent (5) spaces, and begin typing the abstract.

Abstracts should contain the following: 1. INTRODUCTION outlining the significance of the research project. (For the arts categories, the introduction should state the problem/nature and significance of the topic.) 2. Statement of the HYPOTHESIS being tested or the OBJECTIVE for the research. 3. Brief statement of RESEARCH METHODS used. (For the arts, state the method/investigative strategy.) 4. Summary of the RESULTS . 5. Statement of the CONCLUSIONS . 6. A list of grants that support your abstract.

SAMPLE ABSTRACT

IDENTIFICATION OF GAMMA-2-MELANOCYTE STIMULATING HORMONE (ɣ-2-MSH) RESPONSIVE GENES IN MC3R TRANSFECTED BRAINSTEM CAD CELLS BY MICROARRAY ANALYSIS . *Segun Bernard, Brian Redmond, James Wachira and Cleo Hughes Darden. Morgan State University, Department of Biology, Baltimore, MD 21251.

Melanocortins are peptide hormones that are derived from the precursor polypeptide pro-opiomelanocortin. They mediate their effects through a family) of five G-protein coupled receptors, the melanocortin receptors. Some studies have implicated other signaling pathways such as the PKC, MAP kinase, and the JAK/STAT pathways. Melanocortin receptors, melanocortin-3-receptor (MC3R) and melanocortin-4-receptor (MC4R), have been implicated in the pathophysiology of obesity, insulin resistance and salt-sensitive hypertension through gene knockout studies. In order to understand the molecular mechanisms involved in MC3R signaling, we treated MC3R/GFP and GFP control transfected cells with gamma-MSH and isolated total RNA for gene transcription analysis using oligonucleotide microarrays. Total RNA isolated from the two populations of harvested cells was amplified, labeled and co-hybridized to oligonucleotide microarrays. Eighty-eight genes were up-regulated and 91 genes were down-regulated with > 2 ratio and p-value of < 0.05. Several pathways were altered including signal transduction and G-protein coupled receptor protein signaling, among others. Quantitative PCR data indicate that protein tyrosine phosphatase and protein kinase nu genes are up-regulated as a result of MC3R activation by gamma-MSH. The information gathered from this study will enhance our knowledge of the molecular mechanisms involved in MC3R signaling because of its involvement in salt sensitive hypertension and cardiovascular function. (Supported by NIH/NCRR/RCMI/G12RR17581-05 and RCMI funded core facilities)

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Welcome to the Purdue Online Writing Lab

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University houses writing resources and instructional material, and we provide these as a free service of the Writing Lab at Purdue. Students, members of the community, and users worldwide will find information to assist with many writing projects. Teachers and trainers may use this material for in-class and out-of-class instruction.

The Purdue On-Campus Writing Lab and Purdue Online Writing Lab assist clients in their development as writers—no matter what their skill level—with on-campus consultations, online participation, and community engagement. The Purdue Writing Lab serves the Purdue, West Lafayette, campus and coordinates with local literacy initiatives. The Purdue OWL offers global support through online reference materials and services.

A Message From the Assistant Director of Content Development

The Purdue OWL® is committed to supporting students, instructors, and writers by offering a wide range of resources that are developed and revised with them in mind. To do this, the OWL team is always exploring possibilties for a better design, allowing accessibility and user experience to guide our process. As the OWL undergoes some changes, we welcome your feedback and suggestions by email at any time.

Please don't hesitate to contact us via our contact page if you have any questions or comments.

All the best,

Social Media

Facebook twitter.

Socio-emotional experiences of primary school students: Relations to teachers’ underestimation, overestimation, or accurate judgment of their cognitive ability

- Open access

- Published: 15 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Jessica Gnas 1 ,

- Julian Urban 1 , 2 ,

- Markus Daniel Feuchter 3 &

- Franzis Preckel 1

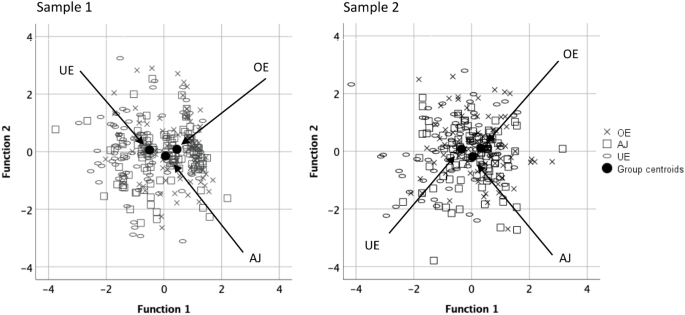

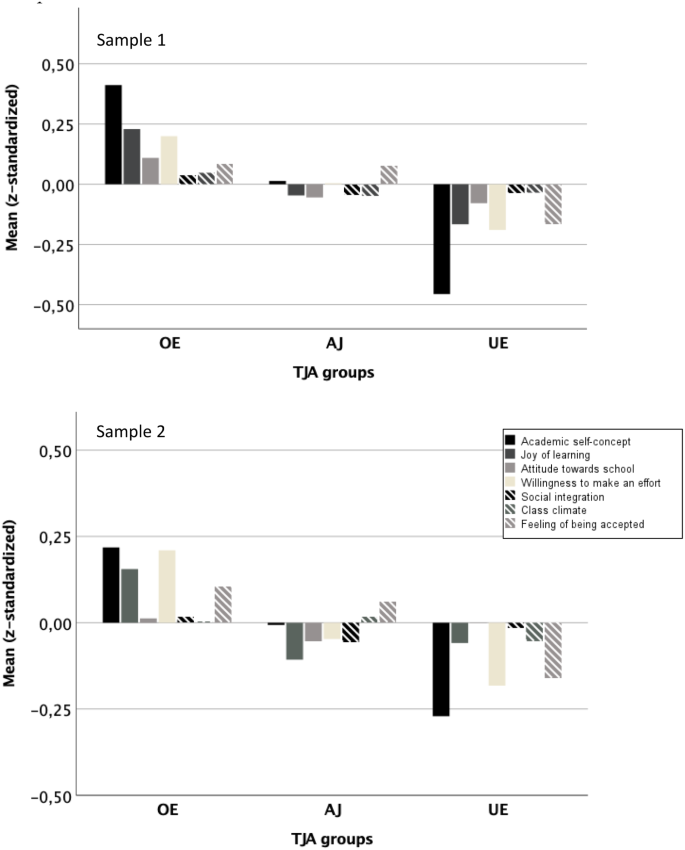

Previous research revealed that students who are overestimated in their ability by their teachers experience school more positively than underestimated students. In the present study, we compared the socio-emotional experiences of N = 1516 students whose cognitive abilities were overestimated, accurately judged, or underestimated by their teachers. We applied propensity score matching using students’ cognitive ability, gender, language, parental education, and teacher’s acquaintance with them as covariates for building the three student groups. Matching students on these variables, reduced the original sample size to subsamples with n 1 = 348, and n 2 = 312 with exact matching including classroom. We compared overestimated, accurately judged, or underestimated students in both matching samples in their socio-emotional profiles (comprised of academic self-concept, joy of learning, attitude towards school, willingness to make an effort, social integration, perceived class climate, and feeling of being accepted by the teacher) by linear discriminant analyses. Groups significantly differed in their profiles. Overestimated students had the most positive socio-emotional experiences of school, followed by accurately judged students. Underestimated students experienced school most negatively. Differences in experiences were most pronounced for the learning environment (medium to large effects for academic self-concept, joy of learning, and willingness to make an effort; negligible effect for attitude towards school) and less for the social environment (medium effects for feeling of being accepted by the teacher; negligible effects for social integration and perceived class climate).

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Theoretical background

1.1 introduction.

How students experience school influences their socio-emotional and personal development. A positive attitude towards school and good social integration at school foster students’ socio-emotional and personal growth (Aviles et al., 2006 ) and academic success (Lam et al., 2018 ). Teachers are heavily involved in students’ socio-emotional experiences of school (SEES); they are central reference persons for students and influence the class’s academic and social climate. Accordingly, students’ positive SEES are associated with teacher support and their relationship with the teacher (Aviles et al., 2006 ; Heller et al., 2012 ; Rucinski et al., 2018 ), teachers’ early childhood specialization (Nocita et al., 2020 ), and teachers’ classroom management skills (Korpershoek et al., 2016 ).

Several studies have investigated the relation between students’ SEES and whether they are over- or underestimated by their teachers. The results consistently show that students who are underestimated in their achievement are at a disadvantage compared to students who are overestimated. For example, underestimated students have a more negative self-concept, enjoy school less, and feel less supported by their teachers and peers (e.g., Rubie-Davies & Peterson, 2016 ; Urhahne, 2015 ). Most studies in this research field have focused on teacher judgments of students’ achievement. However, examining teacher judgments of students’ cognitive ability—rather than academic achievement—in relation to students’ SEES is important because teachers tend to make larger misjudgments for students’ cognitive abilities compared to their academic achievement (Machts et al., 2016 ; Südkamp et al., 2012 ). There is initial evidence supporting the idea that students’ SEES is related to their teachers’ judgments of their cognitive ability. A longitudinal study with primary school students by Baudson ( 2011 ) found that children who were underestimated by their teachers in terms of cognitive ability developed less positively in their academic self-concept, interest, and attitude towards school one year later compared to students who were overestimated. However, other factors could be responsible for the observed differences in the students’ development in this study and more research is needed with matched student samples. In addition, most studies in this area have only investigated students in Grade 4 and above. However, positive experiences in school are particularly relevant in the early school years, and they are a crucial starting point for further learning and socio-emotional development (Aviles et al., 2006 ). Therefore, there is a need for studies with younger students in their primary school years.

In the present study, we add to the literature by investigating a large sample of primary school students in Grades 1 to 4. We assessed multiple dimensions of students’ SEES and teacher judgments of students’ cognitive ability, and controlled for potential confounding variables by matching underestimated, accurately judged, and overestimated students on these variables using propensity score matching (PSM). Our findings may serve to heighten the awareness of possible positive and negative associations between teacher judgments of students’ abilities and students’ SEES.

1.2 Students’ socio-emotional experiences of school

Students’ SEES constitute mental representations of the school environment gained from their experiences. It is a collective term for a multitude of constructs related to the experience of school. De Fruyt et al. ( 2015 ) defined students’ SEES rather broadly as thoughts, feelings, and behaviors developed through learning experiences. Primi et al. ( 2021 ) proposed more specific skills covering socio-emotional functioning in adolescents (i.e., self-management, engaging with others, amity, negative emotion regulation, and open-mindedness). Rauer and Schuck ( 2003 ) defined SEES as the perception and evaluation of the school environment, one’s social relationships and integration, school- and learning-related climate, and one’s own competency. The different dimensions of students’ SEES can broadly be grouped into relationships (with other students and the teacher) and characteristics of the classroom and the school (Eder, 2018 ; Grewe, 2017 ). Similarly, Gnas et al. ( 2022a ) distinguished between the experience of the learning environment and the experience of the social environment . The experience of the learning environment includes students’ academic self-concept, their joy of learning, their attitude towards school, and their willingness to make an effort; the experience of the social environment includes students’ perceptions of their social integration, their feeling of being accepted by the teacher, and the class climate (see Rauer & Schuck, 2003 ; for definitions, see Table 1 ).

Several factors are associated with students’ SEES. First, girls experience school more positively than boys on average (Bergold et al., 2020 ; Likhanov et al., 2020 ; Van Rossem & Vermande, 2004 ). Secondly, positive SEES are related to a positive working atmosphere at school (e.g., high levels of teacher acquaintance with the student, existence of rules in the classroom, low performance goals and competitive pressure; Hofmann & Siebertz-Reckzeh, 2008 ; Johns, 2020 ). Thirdly, social support from peers or adults, such as parents, caregivers, or teachers, promotes positive SEES (Aviles et al., 2006 ). Since students spend a significant part of their lives in school, teachers play a particularly important role. Students’ SEES are associated with their relationship with the teacher (Heller et al., 2012 ; Rucinski et al., 2018 ), teachers’ classroom management (Korpershoek et al., 2016 ), and teachers’ specialization in early childhood education and care, which might be explained by the fact that they gain specialized knowledge and skills that enable them to interact with children in ways that are effective at supporting their future development (Nocita et al., 2020 ). Moreover, teacher judgments of students’ achievement or ability are related to students’ SEES (Wang et al., 2018 ).

1.3 Teacher judgments and students’ socio-emotional experiences of school

In the following, we introduce teacher judgments and their accuracy, and present findings on teacher judgments of students’ achievement and ability. Below, we summarize methods for studying over- and underestimation. We then review findings of studies comparing the SEES of students who are overestimated and underestimated by their teachers.

1.3.1 Teacher judgments of students’ achievement and ability

One central part of teachers’ professional competency is their diagnostic competency (Baumert & Kunter, 2011 ). It can be defined as the competency to correctly judge a student or task concerning a specific characteristic (Urhahne & Wijnia, 2021 ). In research, the term is used interchangeably with teacher judgment accuracy (TJA; Urhahne & Wijnia, 2021 ). Teachers high in this competency can judge task characteristics, such as the demands that certain learning tasks make for students, and student characteristics, such as their cognitive ability. Teachers who are low in judgment accuracy, to various extents, over- or underestimate student or task characteristics. Research distinguishes between relative and absolute TJA (Urhahne & Wijnia, 2021 ). Relative TJA concerns the relation (e.g., the correlation) between the teacher judgment of task or student characteristics and the actual characteristics of the task or student. Absolute TJA concerns the difference between the judged and actual task or student characteristic and allows consideration of both the magnitude and direction of judgment inaccuracies (i.e., over- and underestimation).

To date, most of the studies on TJA have focused on relative TJA concerning judgments of students’ academic achievement and cognitive ability Footnote 1 . Three meta-analyses examined TJA by correlating teacher judgments with students’ actual achievement or cognitive ability. The results demonstrate that teachers are more accurate in judging students’ achievement ( r =.66 in 16 studies with 55 effect sizes, Hoge & Coladarci, 1989 ; r =.63 in 75 studies with 73 effect sizes, Südkamp et al., 2012 ) than students’ cognitive ability ( r =.43 in 33 studies with 106 effect sizes; Machts et al., 2016 ).

1.3.2 Studying overestimated versus underestimated students: methodological considerations

Absolute TJA allows researchers to investigate over- and underestimation. The literature reports two ways of operationalizing absolute TJA: residuals and the level component. Residuals are derived from regressing teacher judgments on student characteristics or vice versa. They display the share of variance in teacher judgments not explained by the actual student characteristic (e.g., Gentrup et al., 2020). The level component represents the difference between the values of teacher judgments and the actual student values (e.g., Zhou & Urhahne, 2013)

For studying over- and underestimation, the residuals or the level component can be used either as continuous variables or by using cut-offs to build groups of underestimated, overestimated, or accurately judged students. Both approaches have been used for the comparison of over- and underestimated students and their SEES (see Table 2 ). The comparison has been conducted by using TJA as a cut-off variable (e.g., binary: overestimated vs. underestimated students) or as a continuous variable (e.g., increasing residuals for decreasing TJA). Furthermore, for studying the relation of over- and underestimation with SEES, the studies either conducted group comparisons (e.g., comparing overestimated and underestimated students in their SEES) or analyzed relations (e.g., TJA served as a predictor for/was correlated with students’ SEES).

1.3.3 Overestimated versus underestimated students’ socio-emotional experiences of school

Table 3 summarizes the findings from studies on students’ SEES in relation to teachers’ over- and underestimation. Most of the findings are related to the experience of the learning environment, and only a few are related to the experience of the social environment. In five studies, students’ achievement was the characteristic judged by the teachers; in two studies, it was students’ cognitive or mathematical ability. Six studies reported actual TJA, and one study by Gniewosz and Watt ( 2017 ) reported students’ perception of TJA. Four studies took place in primary school, and three took place in secondary school. Half the studies did not include any control variables; the other half included only a few (mostly student achievement). Five studies were carried out cross-sectionally, whereas two studies investigated the long-term effect of over- and underestimation on students’ SEES using a longitudinal design. The samples varied between 144 and 1271 students; however, six of eight studies had samples with N < 300. Finally and most importantly, most of the findings were significant and all were in favor of overestimated students. That is, overestimated students perceived their learning and social environment more positively than underestimated students.

Furthermore, Table 3 shows the effect sizes by which over- and underestimated students differed in various dimensions of the experience of the social and learning environment Footnote 2 . More specifically, effects for the experience of the social environment were either small or not significant. Small effects were found for perceived teacher support and behavior as well as perceived peer support (Rubie-Davies & Peterson, 2016 ; Stang & Urhahne, 2016 ; Urhahne, 2015 ); nonsignificant effects were found for changes in feelings of being accepted, social integration, and perceived class climate (Baudson, 2011 ). Effects for the experience of the learning environment were heterogeneous. Looking at the dimensions more closely, it becomes clear that the largest effects (medium to large effect sizes) were consistently present for academic self-concept and enjoyment (Baudson, 2011 ; Urhahne, 2015 ; Urhahne et al., 2010 , 2011 ). Furthermore, (consistently) small effects were found for changes in academic interest and attitude towards school, as well as students’ self-efficacy and test anxiety (Baudson, 2011 ; Rubie-Davies & Peterson, 2016 ; Urhahne, 2015 ; Urhahne et al., 2010 , 2011 ). The remaining dimensions were more heterogeneous: small, medium, and large effects were found for expectancy of success and attribution for success/failure (Urhahne et al., 2010 , 2011 ; Urhahne, 2015 ; Zhou & Urhahne, 2013 ); and nonsignificant, small, and medium effects were found for motivational variables (i.e., students’ learning motivation, learning goals, level of aspiration, and changes in utility and intrinsic values; Gniewosz & Watt, 2017 ; Rubie-Davies & Peterson, 2016 ; Urhahne, 2015 ; Urhahne et al., 2010 ; Urhahne et al., 2011 ). Altogether, overestimated and underestimated students descriptively differed more in their experience of the learning environment compared to their experience of the social environment. However, the findings mainly concern the TJA of academic achievement and there are more findings for the experience of the learning environment than for the social environment.