- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section New Historicism

Introduction, general overviews.

- Essay Collections

- Theoretical Influences

- Scholarly Influences

- Book-Length Studies

- Feminist Studies

- New New Historicism, or New Materialism

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Jonathan Goldberg

- Michel de Certeau

- Michel Foucault

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Black Atlantic

- Postcolonialism and Digital Humanities

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

New Historicism by Neema Parvini LAST REVIEWED: 26 July 2017 LAST MODIFIED: 26 July 2017 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780190221911-0015

New historicism has been a hugely influential approach to literature, especially in studies of William Shakespeare’s works and literature of the Early Modern period. It began in earnest in 1980 and quickly supplanted New Criticism as the new orthodoxy in early modern studies. Despite many attacks from feminists, cultural materialists, and traditional scholars, it dominated the study of early modern literature in the 1980s and 1990s. Arguably, since then, it has given way to a different, more materialist, form of historicism that some call “new new historicism.” There have also been variants of “new historicism” in other periods of the discipline, most notably the romantic period, but its stronghold has always remained in the Renaissance. At its core, new historicism insists—contra formalism—that literature must be understood in its historical context. This is because it views literary texts as cultural products that are rooted in their time and place, not works of individual genius that transcend them. New-historicist essays are thus often marked by making seemingly unlikely linkages between various cultural products and literary texts. Its “newness” is at once an echo of the New Criticism it replaced and a recognition of an “old” historicism, often exemplified by E. M. W. Tillyard, against which it defines itself. In its earliest iteration, new historicism was primarily a method of power analysis strongly influenced by the anthropological studies of Clifford Geertz, modes of torture and punishment described by Michel Foucault, and methods of ideological control outlined by Louis Althusser. This can be seen most visibly in new-historicist work of the early 1980s. These works came to view the Tudor and early Stuart states as being almost insurmountable absolutist monarchies in which the scope of individual agency or political subversion appeared remote. This version of new historicism is frequently, and erroneously, taken to represent its entire enterprise. Stephen Greenblatt argued that power often produces its own subversive elements in order to contain it—and so what appears to be subversion is actually the final victory of containment. This became known as the hard version of the containment thesis, and it was attacked and critiqued by many commentators as leaving too-little room for the possibility of real change or agency. This was the major departure point of the cultural materialists, who sought a more dynamic model of culture that afforded greater opportunities for dissidence. Later new-historicist studies sought to complicate the hard version of the containment thesis to facilitate a more flexible, heterogeneous, and dynamic view of culture.

Owing to its success, there has been no shortage of textbooks and anthology entries on new historicism, but it has often had to share space with British cultural materialism, a school that, though related, has an entirely distinct theoretical and methodological genesis. The consequence of this dual treatment has resulted in a somewhat caricatured view of both approaches along the axis of subversion and containment, with new historicism representing the latter. While there is some truth to this shorthand account, any sustained engagement with new-historicist studies will reveal its limitations. Readers should be aware, therefore, that while accounts that contrast new historicism with cultural materialism—for example, Dollimore 1990 , Wilson 1992 , and Brannigan 1998 —can be illuminating, they can also by the terms of that contrast tend to oversimplify. Be aware also that because new historicism has been a controversial development in the field, accounts are seldom entirely neutral. Mullaney 1996 , for example, was written by a new historicist, while Parvini 2012 was written by an author who has been strongly critical of the approach.

Brannigan, John. New Historicism and Cultural Materialism . Transitions. New York and London: Palgrave Macmillan, 1998.

DOI: 10.1007/978-1-349-26622-7

Introduction to new historicism and cultural materialism aimed at the general reader and student, which does much to elucidate the differences between those two schools. In doing so, however, it is perhaps guilty of oversimplification, especially as regards the new historicists, who, according to Brannigan, never progress beyond the hard version of the containment thesis.

Dollimore, Jonathan. “Critical Developments: Cultural Materialism, Feminism and Gender Critique, and New Historicism.” In Shakespeare: A Bibliographical Guide . New ed. Edited by Stanley Wells, 405–428. Oxford: Clarendon, 1990.

A cultural-materialist take on “critical developments” over the decade of the 1980s that elaborates on the differences between new historicism and cultural materialism. Useful document of its time, but be aware of identifying new historicists too closely with the containment thesis it outlines, which became softer and more nuanced in later new-historicist work.

Hamilton, Paul. Historicism . New Critical Idiom. New York: Routledge, 1996.

DOI: 10.4324/9780203426289

Guide to wider tradition of historicism from ancient Greece to the late 20th century. Chapters on Michel Foucault and new historicism usefully view both subjects through this wider lens, although some of the nuances (for example, the differences between new historicism and cultural materialism) are lost along the way. See especially pp. 115–150.

Harris, Jonathan Gil. “New Historicism and Cultural Materialism: Michel Foucault, Stephen Greenblatt, Alan Sinfield.” In Shakespeare and Literary Theory . By Jonathan Gil Harris, 175–192. Oxford Shakespeare Topics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Structured into three parts: the first on Foucault, the second on Greenblatt’s “Invisible Bullets” (see Greenblatt 1988 , cited under Essays ), and the third on the cultural materialist Sinfield. Concise, if cursory, overview. Its focus on practice rather than theory renders it too specific to serve as a lone entry point, but useful introductory material if considered alongside other accounts.

Mullaney, Steven. “After the New Historicism.” In Alternative Shakespeares . Vol. 2. Edited by Terence Hawkes, 17–37. New Accents. New York and London: Routledge, 1996.

By its own admission a “partisan account” (p. 21) of new-historicist practice by one of its own foremost practitioners. Argues that the view of new historicism become distorted through oversimplification. Reminds us of the extent of new historicism’s theoretical and methodological innovations, which detractors “sometimes fail to acknowledge” (p. 28).

Parvini, Neema. Shakespeare and Contemporary Theory: New Historicism and Cultural Materialism . New York and London: Bloomsbury, 2012.

DOI: 10.5040/9781472555113

More comprehensive in coverage than other available guides, perhaps owing to its more recent publication. Features a timeline of critical developments, a “Who’s Who” in new historicism and cultural materialism, and a glossary of theoretical terms. Includes sections on Clifford Geertz and Michel Foucault and offers clear distinctions between early new-historicist work and “cultural poetics.”

Robson, Mark. Stephen Greenblatt . Routledge Critical Thinkers. New York and London: Routledge, 2007.

Although centered on Greenblatt, this book effectively doubles as an introduction to new historicism and its concepts. Lucidly written, it features some incisive analysis and a comprehensive reading list to direct further study.

Wilson, Richard. “Introduction: Historicising New Historicism.” In New Historicism and Renaissance Drama . Edited by Richard Wilson and Richard Dutton, 1–18. Longman Critical Readers. New York and London: Longman, 1992.

Gains from being very theoretically well informed. Argues that new historicism is best understood, ironically, if historicized in the context of Ronald Reagan’s America and the final years of the Cold War. An excellent entry point to understanding new historicism and its concerns. A section contrasting cultural materialism with new historicism closes the piece.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Literary and Critical Theory »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Achebe, Chinua

- Adorno, Theodor

- Aesthetics, Post-Soul

- Affect Studies

- Afrofuturism

- Agamben, Giorgio

- Anzaldúa, Gloria E.

- Apel, Karl-Otto

- Appadurai, Arjun

- Badiou, Alain

- Baudrillard, Jean

- Belsey, Catherine

- Benjamin, Walter

- Bettelheim, Bruno

- Bhabha, Homi K.

- Biopower, Biopolitics and

- Blanchot, Maurice

- Bloom, Harold

- Bourdieu, Pierre

- Brecht, Bertolt

- Brooks, Cleanth

- Caputo, John D.

- Chakrabarty, Dipesh

- Conversation Analysis

- Cosmopolitanism

- Creolization/Créolité

- Crip Theory

- Critical Theory

- Cultural Materialism

- de Certeau, Michel

- de Man, Paul

- de Saussure, Ferdinand

- Deconstruction

- Deleuze, Gilles

- Derrida, Jacques

- Dollimore, Jonathan

- Du Bois, W.E.B.

- Eagleton, Terry

- Eco, Umberto

- Ecocriticism

- English Colonial Discourse and India

- Environmental Ethics

- Fanon, Frantz

- Feminism, Transnational

- Foucault, Michel

- Frankfurt School

- Freud, Sigmund

- Frye, Northrop

- Genet, Jean

- Girard, René

- Global South

- Goldberg, Jonathan

- Gramsci, Antonio

- Greimas, Algirdas Julien

- Grief and Comparative Literature

- Guattari, Félix

- Habermas, Jürgen

- Haraway, Donna J.

- Hartman, Geoffrey

- Hawkes, Terence

- Hemispheric Studies

- Hermeneutics

- Hillis-Miller, J.

- Holocaust Literature

- Human Rights and Literature

- Humanitarian Fiction

- Hutcheon, Linda

- Žižek, Slavoj

- Imperial Masculinity

- Irigaray, Luce

- Jameson, Fredric

- JanMohamed, Abdul R.

- Johnson, Barbara

- Kagame, Alexis

- Kolodny, Annette

- Kristeva, Julia

- Lacan, Jacques

- Laclau, Ernesto

- Lacoue-Labarthe, Philippe

- Laplanche, Jean

- Leavis, F. R.

- Levinas, Emmanuel

- Levi-Strauss, Claude

- Literature, Dalit

- Lonergan, Bernard

- Lotman, Jurij

- Lukács, Georg

- Lyotard, Jean-François

- Metz, Christian

- Morrison, Toni

- Mouffe, Chantal

- Nancy, Jean-Luc

- Neo-Slave Narratives

- New Historicism

- New Materialism

- Partition Literature

- Peirce, Charles Sanders

- Philosophy of Theater, The

- Postcolonial Theory

- Posthumanism

- Postmodernism

- Post-Structuralism

- Psychoanalytic Theory

- Queer Medieval

- Race and Disability

- Rancière, Jacques

- Ransom, John Crowe

- Reader Response Theory

- Rich, Adrienne

- Richards, I. A.

- Ronell, Avital

- Rosenblatt, Louse

- Said, Edward

- Settler Colonialism

- Socialist/Marxist Feminism

- Stiegler, Bernard

- Structuralism

- Theatre of the Absurd

- Thing Theory

- Tolstoy, Leo

- Tomashevsky, Boris

- Translation

- Transnationalism in Postcolonial and Subaltern Studies

- Virilio, Paul

- Warren, Robert Penn

- White, Hayden

- Wittig, Monique

- World Literature

- Zimmerman, Bonnie

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|195.190.12.77]

- 195.190.12.77

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

24 What Is New Historicism? What Is Cultural Studies?

When we use New Historicism or cultural studies as our lens, we seek to understand literature and culture by examining the historical and cultural contexts in which literary works were produced and by exploring the ways in which literature and culture influence and are influenced by social and political power dynamics. For our exploration of these critical methods, we will consider the literary work’s context as the center of our target.

New Historicism is often associated with the work of Stephen Greenblatt , who argued that literature is not a timeless reflection of universal truths, but rather a product of the historical and cultural contexts in which it was produced. Greenblatt emphasized the importance of studying the social, political, and economic factors that shaped literary works, as well as the ways in which those works in turn influenced the culture and politics of their time.

New Historicism also seeks to break down the boundaries between high and low culture, and to explore the ways in which literature and culture interact with other forms of discourse and representation, such as science, philosophy, and popular culture.

One of the key principles of New Historicism is the idea that literature and culture are never neutral or objective, but are always implicated in power relations and struggles. It also emphasizes the importance of the reader or interpreter in shaping the meaning of a text, arguing that our own historical and cultural contexts influence the way we understand and interpret literary works. When using this method, we often talk about cultural artifacts as part of the discourse of their time period.

New Historicism has been influential in a variety of fields, including literary and cultural studies, history, and anthropology. It has been used to analyze a wide range of literary works, from Shakespeare to contemporary novels, as well as other cultural artifacts such as films and popular music.

Cultural studies is an interdisciplinary approach to analyzing literature that emerged in the late 20th century. Unlike traditional literary criticism that focuses solely on the text itself, cultural studies criticism explores the relationship between literature and culture. It considers how literature reflects, influences, and is influenced by the broader cultural, social, political, and historical contexts in which it is produced and consumed.

In cultural studies literary criticism, scholars may examine how literature intersects with issues such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and power dynamics. The goal is to understand how literature participates in and shapes cultural discourses. This approach emphasizes the importance of considering the cultural and social implications of literary texts, as well as the ways in which literature can be a site of contestation and negotiation.

Key concepts in cultural studies literary criticism include hegemony, representation, identity, and the politics of culture. Scholars in this field often draw on a variety of theoretical perspectives, including postcolonial theory, feminist theory, queer theory, and critical race theory, to analyze and interpret literary works in their cultural context. We will explore these approaches to literature in more depth in future parts of the book.

Learning Objectives

- Understand how formal elements in literary texts create meaning within the context of culture and literary discourse. (CLO 2.1

- Using a literary theory, choose appropriate elements of literature (formal, content, or context) to focus on in support of an interpretation (CLO 2.3)

- Emphasize what the work does and how it does it with respect to form, content, and context (CLO 2.4

- Understand how context impacts the reading of a text, and how different contexts can bring about different readings (CLO 4.1)

- Demonstrate through discussion and/or writing how textual interpretation can change given the context from which one reads (CLO 6.2)

- Understand that interpretation is inherently political, and that it reveals assumptions and expectations about value, truth, and the human experience (CLO 7.1)

Scholarship: An Excerpt from the Introduction to Michel Foucault’s The Archaeology of Knowledge (1969)

Michel Foucault, the French philosopher and historian, is widely credited with the ideas about history that led to the development of New Historicism as an approach to literary texts. In this passage, Foucault explains his aims in proposing that history does not consist of stable facts. Understanding Foucault’s approach to history is necessary for understanding the New Historicism critical approach to literature.

In order to avoid misunderstanding, I should like to begin with a few observations. My aim is not to transfer to the field of history, and more particularly to the history of knowledge (connaissances), a structuralist method that has proved valuable in other fields of analysis. My aim is to uncover the principles and consequences of an autochthonous transformation that is taking place in the field of historical knowledge. It may well be that this, transformation, the problems that it raises, the tools that it uses, the concepts that emerge from it, and the results that it obtains are not entirely foreign to what is called structural analysis. But this kind of analysis is not specifically used; my aim is most decidedly not to use the categories of cultural totalities (whether world-views, ideal types, the particular spirit of an age) in order to impose on history, despite itself, the forms of structural analysis. The series described, the limits fixed, the comparisons and correlations made are based not on the old philosophies of history, but are intended to question teleologies and totalisations; in so far as my aim is to define a method of historical analysis freed from the anthropological theme, it is clear that the theory that I am about to outline has a dual relation with the previous studies. It is an attempt to formulate, in general terms (and not without a great deal of rectification and elaboration), the tools that these studies have used or forged for themselves in the course of their work. But, on the other hand, it uses the results already obtained to define a method of analysis purged of all anthropologism. The ground on which it rests is the one that it has itself discovered. The studies of madness and the beginnings of psychology, of illness and the beginnings of a clinical medicine, of the sciences of life, language, and economics were attempts that were carried out, to some extent, in the dark: but they gradually became clear, not only because little by little their method became more precise, but also because they discovered – in this debate on humanism and anthropology – the point of its historical possibility. In short, this book, like those that preceded it, does not belong – at least directly, or in the first instance – to the debate on structure (as opposed to genesis, history, development); it belongs to that field in which the questions of the human being, consciousness, origin, and the subject emerge, intersect, mingle, and separate off. But it would probably not be incorrect to say that the problem of structure arose there too. This work is not an exact description of what can be read in Madness and Civilisation, Naissance de la clinique, or The Order of Things. It is different on a great many points. It also includes a number of corrections and internal criticisms. Generally speaking, Madness and Civilisation accorded far too great a place, and a very enigmatic one too, to what I called an ‘experiment’, thus showing to what extent one was still close to admitting an anonymous and general subject of history; in Naissance de la clinique, the frequent recourse to structural analysis threatened to bypass the specificity of the problem presented, and the level proper to archaeology; lastly, in The Order of Things, the absence of methodological signposting may have given the impression that my analyses were being conducted in terms of cultural totality. It is mortifying that I was unable to avoid these dangers: I console myself with the thought that they were intrinsic to the enterprise itself, since, in order to carry out its task, it had first to free itself from these various methods and forms of history; moreover, without the questions that I was asked,’ without the difficulties that arose, without the objections that were made, I may never have gained so clear a view of the enterprise to which I am now inextricably linked. Hence the cautious, stumbling manner of this text: at every turn, it stands back, measures up what is before it, gropes towards its limits, stumbles against what it does not mean, and digs pits to mark out its own path. At every turn, it denounces any possible confusion. It rejects its identity, without previously stating: I am neither this nor that. It is not critical, most of the time; it is not a way of saying that everyone else ‘ is wrong. It is an attempt to define a particular site by the exteriority of its vicinity; rather than trying to reduce others to silence, by claiming that what they say is worthless, I have tried to define this blank space from which I speak, and which is slowly taking shape in a discourse that I still feel to be so precarious and so unsure. ‘Aren’t you sure of what you’re saying? Are you going to change yet again, shift your position according to the questions that are put to you, and say that the objections are not really directed at the place from which you, are speaking? Are you going to declare yet again that you have never been what you have been reproached with being? Are you already preparing the way out that will enable you in your next book to spring up somewhere else and declare as you’re now doing: no, no, I’m not where you are lying in wait for me, but over here, laughing at you?’ ‘What, do you imagine that I would take so much trouble and so much pleasure in writing, do you think that I would keep so persistently to my task, if I were not preparing – with a rather shaky hand – a labyrinth into which I can venture, in which I can move my discourse, opening up underground passages, forcing it to go far from itself, finding overhangs that reduce and deform its itinerary, in which I can lose myself and appear at last to eyes that I will never have to meet again. I am no doubt not the only one who writes in order to have no face. Do not ask who I am and do not ask me to remain the same: leave it to our bureaucrats and our police to see that our papers are in order. At least spare us their morality when we write.’

After reading this brief excerpt from Foucault’s approach to history, how do you feel about his assertion that there are no stable facts, that history is essentially like any other text that we can deconstruct? Is there such a thing as “objective” or “true” history? Why or why not? How does this approach compare with what you learned about deconstruction in our previous section?

Scholar Jean Howard has said of the historical/biographical criticism (which we studied in part one) that it depends on three assumptions:

- “history is knowable”;

- “literature mirrors…or reflects historical reality”;

- “historians and critics can see the facts objectively” (Howard 18).

Foucault and the New Historicists reject these three assumptions.

Cultural Studies: From “Notes on Deconstructing the ‘Popular'” by Stuart Hall

Now let’s look at an example of Cultural Studies criticism: Stuart Hall’s “Notes on Deconstructing the ‘Popular.'” Hall, a Jamaican-born cultural theorist and sociologist, was one of the founders of British Cultural Studies. He explored the process of encoding and decoding that accompanies any interaction readers have with a text. When Hall talks about “periodisation” in the passage below, he is discussing historians’ and literary theorists’ attempts to classify works through “periods” (e.g., the English Romantic poets; the Bloomsbury Group , etc.). Hall extends this difficulty to the phrase “popular culture,” which is often used in cultural studies criticism.

First, I want to say something about periodisations in the study of popular culture. Difficult problems are posed here by periodization—I don’t offer it to you simply as a sort of gesture to the historians. Are the major breaks largely descriptive? Do they arise largely from within popular culture itself, or from factors which are outside of but impinge on it? With what other movements and periodisations is “popular culture” most revealingly linked? Then I want to tell you some of the difficulties I have with the term “popular.” I have almost as many problems with “popular” as I have with “culture.” When you put the two terms together the difficulties can be pretty horrendous. Throughout the long transition into agrarian capitalism and then in the formation and development of industrial capitalism, there is a more or less continuous struggle over the culture of working people, the labouring classes and the poor. This fact must be the starting point for any study, both of the basis for, and of the transformations of, popular culture. The changing balance and relations of social forces throughout that history revealed themselves, time and again, in struggles over the forms of the culture, traditions and ways of life of the popular classes. Capital had a stake in the culture of the popular classes because the constitution of a whole new social order around capital required a more or less continuous, if intermittent, process of re-education, in the broadest sense. And one of the principal sites of resistance to the forms through which this “reformation” of the people was pursued lay in popular tradition. That is why popular culture is linked, for so long, to questions of tradition, of traditional forms of life, and why its “traditionalism” has been so often misinterpreted as a product of a merely conservative impulse, backward-looking and anachronistic. Struggle and resistance—but also, of course, appropriation and ex -propriation. Time and again, what we are really looking at is the active destruction of particular ways of life, and their transformation into something new. “Cultural change” is a polite euphemism for the process by which some cultural forms and practices are driven out of the centre of popular life, actively marginalised. Rather than simply “falling into disuse” through the Long March to modernization, things are actively pushed aside, so that something else can take their place. The magistrate and the evangelical police have, or ought to have, a more “honoured” place in the history of popular culture than they have usually been accorded. Even more important than ban and proscription is that subtle and slippery customer—“reform” (with all the positive and unambiguous overtones it carries today). One way or another, “the people” are frequently the object of “reform”: often, for their own good, of course—in their “best interest.” We understand struggle and resistance, nowadays, rather better than we do reform and transformation. Yet “transformations” are at the heart of the study of popular culture. I mean the active work on existing traditions and activities, their active reworking, so that they come out a different way: they appear to “persist”— yet, from one period to another, they come to stand in a different relation to the ways working people live and the ways they define their relations to each other, to “the others” and to their conditions of life. Transformation is the key to the long and protracted process of the “moralization” of the labouring classes, and the “demoralization” of the poor, and the “re-education” of the people. Popular culture is neither, in a “pure” sense, the popular traditions of resistance to these processes; nor is it the forms which are superimposed on and over them. It is the ground on which the transformations are worked. In the study of popular culture, we should always start here: with the double stake in popular culture, the double movement of containment and resistance, which is always inevitably inside it.

Now that you’ve read examples of scholarship from these two approaches, what similarities and differences do you see? Despite significant overlaps—both approaches consider power structures and view texts as artifacts, for example—Cultural Studies tends to have a broader scope, incorporating insights from various cultural disciplines such as sociology and anthropology. New Historicism focuses more specifically on the interplay between literature and history. Additionally, Cultural Studies may engage more directly with contemporary cultural and political issues, while New Historicism tends to focus on historical periods and their relevance to understanding literature.

How to Use New Historicism and Cultural Studies as Critical Approaches

When using a New Historicism or cultural studies approach to analyze a literary text, you should consider the connections between the text and its historical context. With cultural studies, you will also consider how the text influenced and was influenced by popular culture, and how the text’s reception changed over time. You can do this in a variety of ways. Here are a few approaches you might consider. Some of them such as author background, reader response, and identifying power dynamics will feel familiar to you from previous chapters.

- Research the Historical Context: Investigate the time period in which the literary work was written. Explore political events, social structures, economic conditions, and cultural movements.

- Author’s Background: Examine the life and background of the author. Consider their personal experiences, beliefs, and the historical events that may have influenced them.

- Identify Power Dynamics: Analyze power relationships within the text and in the historical context. Consider issues of class, gender, race, and other forms of social hierarchy.

- Interdisciplinary Approach: Draw on insights from various disciplines such as history, sociology, anthropology, and political science to enrich your understanding of the historical and cultural context.

- Cultural Artifacts: Treat the literary work as a cultural artifact. Identify elements within the text that reflect or respond to the cultural values, norms, and anxieties of the time.

- Dialogues with Other Texts: Explore how the literary work engages with other texts, both literary and non-literary. Look for intertextual references and consider how the work contributes to broader cultural conversations (the discourse Foucault talks about).

- Language and Literary Techniques: Analyze the language, narrative structure, and formal elements of the text. Consider how these literary techniques contribute to the overall meaning and how they may be influenced by or respond to historical factors.

- Ideological Critique: Investigate the ideologies present in the text and how they align with or challenge the dominant ideologies of the historical period. Consider the ways in which literature participates in ideological struggles. We will explore more specific examples of how to do this when we focus on Marxism and Postcolonial Studies in our next section.

- Social and Cultural Constructs: Examine how social and cultural constructs are represented in the text. This includes exploring representations of identity, social norms, and cultural practices.

- Historical Events and Allusions: Identify direct or indirect references to historical events within the text. Consider how the events are portrayed and what commentary they offer on the historical moment.

- Historical Change and Continuity: Assess how the text reflects or responds to processes of historical change and continuity. Consider whether the text aligns with or challenges prevailing attitudes and structures.

- Reader Response: Reflect on how the historical context might shape the way readers interpret and respond to the text. Consider how the meaning of the text may evolve across different historical and cultural contexts.

You do not need to consider every aspect of the text mentioned above to write an effective New Historicism analysis. You can focus on one or a few of these elements in your approach to the text.

As noted above, a cultural studies critical approach is similar to New Historicism but focuses more on the text as it is received in a particular culture, with more emphasis on intersectionality. A cultural studies approach may consider a variety of artifacts in addition to literary texts (such as film and other media) for analysis. A cultural studies approach might also consider how cultural influences, receptions, and attitudes have changed over time.

Let’s look at how do do these types of criticism by applying New Historicism to a text.

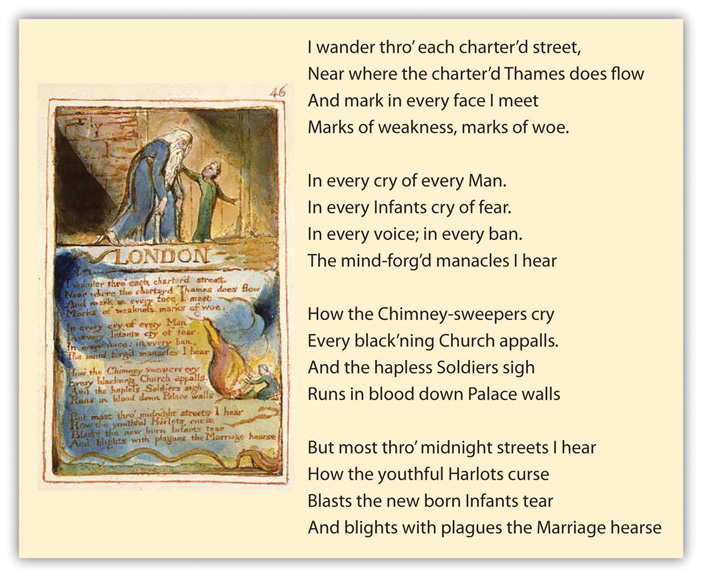

Applying New Historicism Techniques to Literature

As with our other critical approaches, we will start with a close reading of the poem below (we’ll do this together in class or as part of the recorded lecture for this chapter). After you complete your close reading of the poem and find evidence from the text, you’ll need to look outside the text for additional information to place the poem in its context. I have provided some additional resources to demonstrate how you might do this. Looking at the text within its context will help you to formulate a thesis statement that makes an argument about the text, using New Historicism as your critical method.

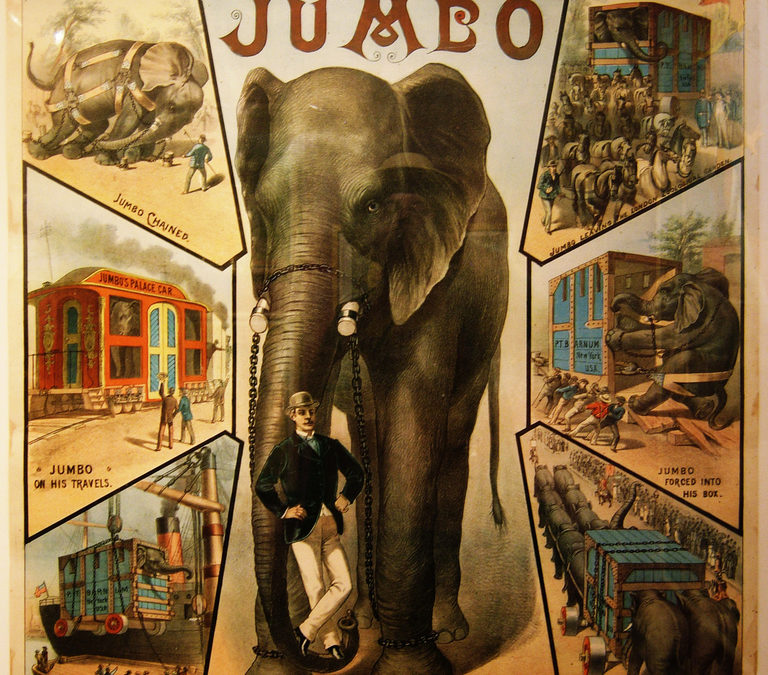

“Lament for Dark Peoples”

I was a red man one time, But the white men came. I was a black man, too, But the white men came.

They drove me out of the forest. They took me away from the jungles. I lost my trees. I lost my silver moons.

Now they’ve caged me In the circus of civilization. Now I herd with the many— Caged in the circus of civilization.

The first thing we need to know is more about Langston Hughes as a poet. Who was he? When did he write? What was the cultural context for his writing? We can go to Wikipedia as a starting point for our research, but we should not cite Wikipedia. Instead, we will want to find higher-quality literary scholarship to use in our analysis.

The open source article “ Langston Hughes’s Poetic Vision of the American Dream: A Complex and Creative Encoded Language” by Christine Dualé informs us that “Hughes gained his reputation as a “jazz poet” during the jazz era or Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s” ( Dualé 1). Dualé quotes a study of Black poets during the Harlem Renaissance that provides some context for this poem: “Many black intellects were disquieted by the white vogue for blackness. They recognized how frivolous and temporal it was, and the extent to which their culture was being admired for all the ‘primitive’ qualities from which they wished to be distanced” ( Dualé quoting Archer Straw).

This quote helps us to understand lines 9-12 of the poem, where Hughes describes the “circus of civilization” that he felt under the gaze of this “white vogue for blackness.”

In considering the question of social constructs and power dynamics during this period, we need to know more about the Harlem Renaissance, preferably looking for contemporary sources that describe this period. JSTOR is a good database for this type of research. I limit my search by year to get five results, and I choose an article from Alain Locke (in part, because I already know enough about the Harlem Renaissance to know that Locke was an important part of it—it’s totally acceptable to use your own existing knowledge of the historical context, if you have it, to guide your research!).

When I read “The Negro’s Contribution to American Art and Literature,” written by Howard University philosophy professor Alain Locke in 1928, I quickly find the prevailing social construct that the dominant intellectual culture at the time (white American men) had formed about African American writers during the period when this poem was written. I have quoted from the first page of the article below:

THERE are two distinctive elements in the cultural background of the American Negro: one, his primitive tropical heritage, however vague and clouded over that may be, and second, the specific character of the Negro group experience in America both with respect to group history and with regard to unique environing social conditions. As an easily discriminable minority, these conditions are almost inescapable for all sections of the Negro population, and function, therefore, to intensify emotionally and intellectually group feelings, group reactions, group traditions. Such an accumulating body of collective experience inevitably matures into a group culture which just as inevitably finds some channels of unique expression, and this has been and will be the basis of the Negro’s characteristic expression of himself in American life. In fact, as it matures to conscious control and intelligent use, what has been the Negro’s social handicap and class liability will very likely become his positive group capital and cultural asset. Certainly whatever the Negro has produced thus far of distinctive worth and originality has been derived in the main from this source, with the equipment from the general stock of American culture acting at times merely as the precipitating agent; at others, as the working tools of this creative expression (Locke 234).

In reading this article, it’s important to note that the author, Alain Locke, is a noted African American scholar and writer and the first African American to win a prestigious Rhodes scholarship. He is widely considered to be one of the principal architects of the Harlem Renaissance. What does this passage tell us about the social constructs and contemporary views of African Americans in the late 1920s, when Langston Hughes wrote “Lament for Dark Peoples”? What important historical context seems to be “missing” or glossed over from this cultural description of African Americans in the 1920s? Hint: It’s only 60 years since President Lincolin signed the Emancipation Proclamation, and yet we see no explicit mention of slavery here.

Now to consider how history and context changes, I might also look for a contemporary appraisal of Langston Hughes’s work in the context of the Harlem Renaissance.

Again, I do a JSTOR search, limiting to articles from 2018 through 2023. I get 157 results using the same search terms. Clearly, Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance are playing a prominent role in our contemporary scholarly discourse, especially in the fields of literature, history, and cultural studies. In fact, there’s even a journal called The Langston Hughes Review ! I choose an article from this journal entitled “Guest Editor’s Introduction: Remembering Langston Hughes: His Art, Life, and Legacy Fifty Years Later” by Wallace Best, Professor of Religion and African American Studies at Princeton University.

In this article, I get some corroboration for what my search results have already told me: “Langston Hughes, one of the principal writers of the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s, is having a renaissance all his own” (Best 1).

Best goes on to demonstrate how Langston Hughes’s role in our culture has shifted since his death:

“There is good reason for all this attention. Arguably one of the most significant writers in United States history, Hughes has left an indelible mark, culturally and politically, on American society. Hailed in his lifetime mainly as the “Poet Laureate of the African American community,” he is now generally embraced as one of the most important poets speaking to, and on behalf of, all Americans. Since his death in May 1967, his writing, particularly his poetry, has been invoked to articulate both our loftiest hopes and our deepest fears as a nation. Seldom has there been a national crisis or an important political event in the United States over the last half-century in which his work has not been recounted. Speakers from across the social, ideological, and political spectrum, from Tim Kaine, Rick Santorum, and Rick Perry to Oprah Winfrey and Barack Obama have cited Hughes’s powerful compositions. His poetry has helped to shape our country’s thinking about itself, our often-troubled past, and our continuing hope for a brighter, more enlightened future.”

With these three external sources and the original poem, I can now begin to think about the kind of thesis statement I want to write.

Example of a New Historicism thesis statement: In one of his earlier poems, “Lament for Dark Peoples,” African American poet Langston Hughes makes a powerful argument against the “circus of [white] civilization (line 12), demonstrating how the cultural norms toward marginalized peoples in place during the early twentieth century damaged all Americans.

I would then use the evidence from the poem as one cultural artifact, including the additional sources I found to provide more context for when the poem was written, the social constructs and power dynamics in place at that time, and the shifts in culture that have now made Langston Hughes a poet for “all Americans” (Best 1).

With New Historicism, because we are considering the context, we must cite some outside sources in addition to the text itself. Here are the sources I cited in this section:

Works Cited

Best, Wallace. “Guest Editor’s Introduction: Remembering Langston Hughes: His Art, Life, and Legacy Fifty Years Later.” The Langston Hughes Review , vol. 25, no. 1, 2019, pp. 1–5. JSTOR , https://doi.org/10.5325/langhughrevi.25.1.0001 . Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

Dualé, Christine. “Langston Hughes’s Poetic Vision of the American Dream: A Complex and Creative Encoded Language.” Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 7 (2018). https://journals.openedition.org/angles/920 . Accessed 3 Oct. 2023. Locke, Alain. “The Negro’s Contribution to American Art and Literature.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , vol. 140, 1928, pp. 234–47. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/1016852 . Accessed 4 Oct. 2023.

One additional note: depending on your approach, it would also be appropriate to borrow research techniques from historians for a New Historicism analysis. This might involve working with archive primary source documents. One example of this type of document that I found in my research on the Harlem Renaissance is this one from the U.S. Library of Congress entitled “The Whites Invade Harlem.”

As noted above, a cultural studies approach would be similar to a New Historicism approach. However, if I were using cultural studies, I might want to focus on the difference between the text’s critical reception when it was published (how it affected and was affected by the discourse in the 1920s) and the text’s critical reception today, focusing on the explosion of academic interest on Langston Hughes’s work in since 2018. I would then look at the particular aspects of culture, such as the election of America’s first Black president and the backlash this created in popular culture, as well as the focus on diversity, equity, and inclusion in academia and how this was reflected in popular culture. For example, I could consider how twenty-first century scholarship focusing on Langston Hughes is one example of a larger desire for inclusion and representation of marginalized groups in literature, what we sometimes refer to as “exploding the canon” (Renza 257).

Limitations of New Historicism and Cultural Studies Criticism

While New Historicism offers valuable insights into the interconnectedness of literature and historical context, it also has its limitations. Here are some potential drawbacks:

- Relativism: New Historicism can sometimes be accused of cultural relativism, as it emphasizes understanding a text within its specific historical context. This might lead to a reluctance to make broader judgments about the quality or significance of a work across different times and cultures.

- Overemphasis on Power Relations: Critics argue that New Historicism can place an excessive focus on power dynamics and political aspects, potentially neglecting other important elements of literary analysis, such as aesthetics or individual authorial intentions.

- Determinism: There’s a risk of determinism in assuming that a text is entirely shaped by its historical context. This approach may downplay the agency of individual authors and the role of artistic creativity in shaping literature.

- Selective Use of History: Scholars employing New Historicism may selectively use historical evidence to support their interpretations, potentially overlooking contradictory historical data or alternative perspectives that challenge their readings (don’t do this!)

- Overlooking Textual Autonomy/Author Authority: Critics argue that New Historicism sometimes neglects the autonomy of literary texts, treating them primarily as reflections of historical conditions rather than as creative and independent entities with their own internal dynamics.

- Tendency for Presentism: There’s a risk of imposing contemporary values and perspectives onto historical texts, leading to anachronistic interpretations that may not accurately reflect the attitudes and beliefs of the time in which the work was created (note how I initially looked for scholarship from the time period of the text I was analyzing above).

These limitations do not mean we shouldn’t use New Historicism; rather, they suggest areas where a more balanced and comprehensive approach to literary analysis may be necessary.

Similarly, cultural studies might place an overwhelming emphasis on cultural factors, sometimes neglecting economic or political considerations that could also shape social dynamics. The relativist stance of cultural studies may hinder critical evaluation and potentially overlook harmful practices or ideologies.

New Historicism and Cultural Criticism Scholars

New historicism.

- Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a French philosopher who viewed history as a text that could be deconstructed. Foucault’s concept of “the discourse” is essential to both New Historicism and Cultural Studies criticism.

- Stephen Greenblatt (b. 1943) is the American Shakespeare scholar who coined the term “New Historicism.”

Cultural Studies

- Stuart Hall (1932-2014) was a Jamaican-born British philosopher and cultural theorist whose ideas were influential to the development of cultural studies as a field.

- Walter Benjamin (1892-1940) was a German philosopher and thinker whose ideas about media were foundational to cultural studies.

- Mikhail Bakhtin (1895-1975) was a Russian philosopher and critic who focused on the importance of context over text in approaches to literary works.

- Roland Barthes (1915-1980) was a French philosopher whose 1967 essay “L’Morte de Auteur” critiqued traditional biographical approaches to literary criticism.

Further Reading

- Benjamin, Walter. “The Author as Producer.” Thinking Photography (1982): 15-31.

- Brannigan, John. New Historicism and Cultural Materialism . Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

- Coates, Christopher. “What was the New Historicism?” The Centennial Review , vol. 37, no. 2, 1993, pp. 267–80. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/23739388. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

- Cotten, Angela L., and Christa Davis Acampora, eds. Cultural Sites of Critical Insight: Philosophy, Aesthetics, and African American and Native American Women’s Writings . State University of New York Press, 2012.

- Dollimore, Jonathan. “Shakespeare, Cultural Materialism and the New Historicism.” New Historicism and Renaissance Drama . Routledge, 2016. 45-56.

- Gallagher, Catherine, and Stephen Greenblatt. Practicing New Historicism . University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. “Racial Memory and Literary History.” PMLA , vol. 116, no. 1, 2001, pp. 48–63. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/463640. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. “What Is the History of Literature?” Critical Inquiry , vol. 23, no. 3, 1997, pp. 460–81. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344030. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

- Hall, Stuart. “Encoding and decoding in the television discourse.” .https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-artslaw/history/cccs/stencilled-occasional-papers/1to8and11to24and38to48/SOP07.pdf

- Hall, Stuart. “Cultural studies and its theoretical legacies.” Stuart Hall . Routledge, 2006. 272-285.

- Harpham, Geoffrey Galt. “Foucault and the New Historicism.” American Literary History , vol. 3, no. 2, 1991, pp. 360–75. JSTOR , http://www.jstor.org/stable/490057. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

- Hoover, Dwight W. “The New Historicism.” The History Teacher , vol. 25, no. 3, 1992, pp. 355–66. JSTOR , https://doi.org/10.2307/494247. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

- Howard, Jean E. “The New Historicism in Renaissance Studies.” English Literary Renaissance 16.1 (1986): 13-43.

- Porter, Carolyn. “History and Literature: ‘After the New Historicism.’” New Literary History , vol. 21, no. 2, 1990, pp. 253–72. JSTOR , https://doi.org/10.2307/469250. Accessed 3 Oct. 2023.

- Renza, Louis A. “Exploding Canons.” Contemporary Literature , vol. 28, no. 2, 1987, pp. 257–70. JSTOR , https://doi.org/10.2307/1208391 . Accessed 13 Feb. 2024.

- Ryan, Kiernan. New Historicism and Cultural Materialism: A Reader. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Directories

- General Literary Theory & Criticism Resources

- African Diaspora Studies

- Critical Disability Studies

- Critical Race Theory

- Deconstruction and Poststructuralism

- Ecocriticism

- Feminist Theory

- Indigenous Literary Studies

- Marxist Literary Criticism

- Narratology

- New Historicism

- Postcolonial Theory

- Psychoanalytic Criticism

- Queer and Trans Theory

- Structuralism and Semiotics

- How Do I Use Literary Criticism and Theory?

- Start Your Research

- Research Guides

- University of Washington Libraries

- Library Guides

- UW Libraries

- Literary Research

Literary Research: New Historicism

What is new historicism.

"New Historicism reopened the interpretation of literature to the social, political, and historical milieu that produced it. To a New Historicist, literature is not the record of a single mind, but the end product of a particular cultural moment. New Historicists look at literature alongside other cultural products of a particular historical period to illustrate how concepts, attitudes, and ideologies operated across a broader cultural spectrum that is not exclusively literary. In addition to analyzing the impact of historical context and ideology, New Historicists also acknowledge that their own criticism contains biases that derive from their historical position and ideology. Because it is impossible to escape one’s own “historicity,” the meaning of a text is fluid, not fixed. New Historicists attempt to situate artistic texts both as products of a historical context and as the means to understand cultural and intellectual history."

Brief Overviews:

- New Historicism/Cultural Poetics (Literary Theory Handbook)

- New Historicism (The Johns Hopkins Guide to Literary Theory & Criticism)

- New Historicism and Cultural Materialism (A Companion to Literary Theory)

Notable Scholars:

Stephen Greenblatt

- Greenblatt, Stephen, and Michael Payne. The Greenblatt Reader . Blackwell Pub., 2005.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. Learning to Curse: Essays in Early Modern Culture . Routledge, 1990.

- Gallagher, Catherine, and Stephen Greenblatt. Practicing New Historicism . University of Chicago Press, 2000.

- Greenblatt, Stephen. Shakespearean Negotiations: The Circulation of Social Energy in Renaissance England. University of California Press, 1988.

Louis Montrose

- Montrose, Louis Adrian. “‘ Eliza, Queene of Shepheardes,’ and the Pastoral of Power. ” English Literary Renaissance , vol. 10, no. 2, 1980, pp. 153–82.

- Montrose, Louis Adrian. “New Historicisms.” In Redrawing the Boundaries: The Transformation of English and American Literary Studies . Edited by Stephen Greenblatt and Giles Gunn, 392–418. New York: Modern Language Association of America, 1992.

Hayden V. White

- White, Hayden. “ The Historical Text as Literary Artifact .” Clio , vol. 3, no. 3, 1974, pp. 277–303.

- White, Hayden V. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe . Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

- White, Hayden V. Tropics of Discourse: Essays in Cultural Criticism . Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

Introductions & Anthologies

Also see other recent eBooks discussing or using new historicism in literature and scholar-recommended sources on new historicism and Hayden White via Oxford Bibliographies.

Definition from: " New Historicism ." Glossary of Poetic Terms. Poetry Foundation.(20 July 2023)

- << Previous: Narratology

- Next: Postcolonial Theory >>

- Last Updated: May 16, 2024 1:27 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uw.edu/research/literaryresearch

Literary Theory and Criticism

Home › Philosophy › New Historicism

New Historicism

By NASRULLAH MAMBROL on October 22, 2020 • ( 0 )

In 1982 Stephen Greenblatt edited a special issue of Genre on Renaissance writing, and in his introduction to this volume he claimed that the articles he had solicited were engaged in a joint enterprise, namely, an effort to rethink the ways that early modern texts were situated within the larger spectrum of discourses and practices that organized sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English culture. This reconsideration had become necessary because many contemporary Renaissance critics had developed misgivings about two sets of assumptions that informed much of the scholarship of previous decades. Unlike the New Critics , Greenblatt and his colleagues were reluctant to consign texts to an autonomous aesthetic realm that dissociated Renaissance writing from other forms of cultural production; and unlike the prewar historicists, they refused to assume that Renaissance texts mirrored, from a safe distance, a unified and coherent world-view that was held by a whole population, or at least by an entire literate class. Rejecting both of these perspectives, Greenblatt announced that a new historicism had appeared in the academy and that it would work from its own set of premises: that Elizabethan and Jacobean society was a site where occasionally antagonistic institutions sponsored a diverse and perhaps even contradictory assortment of beliefs, codes, and customs; that authors who were positioned within this terrain experienced a complex array of subversive and orthodox impulses and registered these complicated attitudes toward authority in their texts; and that critics who wish to understand sixteenth- and seventeenth-century writing must delineate the ways the texts they study were linked to the network of institutions, practices, and beliefs that constituted Renaissance culture in its entirety.

In some ways, Greenblatt’s declaration of New Historicism’s existence was a problematic gesture, for while his title quickly garnered considerable prestige for critics working in this area, it also created expectations that the New Historicists could not satisfy. Specifically, the scholars who encountered Greenblatt’s term tended to conceive of New Historicism as a doctrine or movement, and their inference led them to anticipate that Greenblatt and his colleagues would soon articulate a coherent theoretical program and delineate a set of methodological procedures that would govern their interpretive efforts. When the New Historicists failed to produce such position papers, critics began to accuse them of having a disingenuous relation to literary theory. In response to such objections, Greenblatt published an essay entitled “Towards a Poetics of Culture” (1987), which has had a profound impact on the way academics understand the phenomenon of New Historicism today. In this piece, Greenblatt attempted to show, by way of a shrewd juxtaposition Of Jean-François Lyotard ‘s and Fredric Jameson ‘s paradigms for conceptualizing capitalism, that the genera) question they address, namely, how art and society are interrelated, cannot be answered by appealing to a single theoretical stance. And since the question both Lyotard and Jameson pose is one that New Historicism also raises, its proponents should see the failure of Marxist and poststructuralist attempts to understand the contradictory character of capitalist aesthetics as a warning against any attempt to convert New Historicism into a doctrine or a method. From Greenblatt’s perspective, New Historicism never was and never should be a theory; it is an array of reading practices that investigate a series of issues that emerge when critics seek to chart the ways texts, in dialectical fashion, both represent a society’s behavior patterns and perpetuate, shape, or alter that culture’s dominant codes.

In part because his argument was so effective, and in part because his colleagues developed similar positions independently, most of the critics working in the field of cultural poetics agree that New Historicism is organized by a series of questions and problems, not by a systematic paradigm for the interpretation of literary works. Louis Montrose, for instance, has described some of these issues at length, and in his essay “The Poetics and Politics of Culture” (1986) he provides a list of concerns shared by New Historicists that agrees with and extends Greenblatt’s commentary. Like Greenblatt, Montrose insists that one aim of New Historicism is to refigure the relationship between texts and the cultural system in which they were produced, and he indicates that as a first step in such an undertaking, critics must problematize or reject both the formalist conception of literature as an autonomous aesthetic order that transcends needs and interests and the reflectionist notion that writing simply mirrors a stable and coherent ideology that is endorsed by all members of a society. Having abandoned these paradigms, the New Historicist, he argues, must explain how texts not only represent culturally constructed forms of knowledge and authority but actually instantiate or reproduce in readers the very practices and codes they embody.

Stephen Greenblatt/Pinterest

Montrose also suggests that if New Historicism calls for a rethinking of the relationship between writing and culture, it also initiates a reconsideration of the ways authors specifically and human agents generally interact with social and linguistic systems. This second New Historicist concern is an extension of the first, for if the idea that every human activity is embedded in a cultural field raises questions about the autonomy of literary texts, it also implies that individuals may be inscribed more fully in a network of social practices than many critics tend to believe. But as Montrose goes on to suggest, the New Historicist hostility toward humanist models of freely functioning subjectivity does not imply that he and his colleagues are social determinists. Instead, Montrose argues that individual agency is constituted by a process he calls “subjectification,” which he describes as follows: on the one hand, culture produces individuals who are endowed with subjectivity and the capacity of agency; on the other, it positions them within social networks and subjects them to cultural codes that ultimately exceed their comprehension and control.

In another section of his essay, Montrose adds a third concern to define New Historicism: to what extent can a literary text offer a genuinely radical critique of authority, or articulate views that threaten political orthodoxy? New Historicists have to confront this issue because they are interested in delineating the full range of social work that writing can perform, but as Montrose suggests, they have not yet arrived at a consensus regarding whether literature can generate effective resistance. On one side, critics such as Jonathan Dollimore and Alan Sinfield claim that Renaissance texts contest the dominant religious and political ideologies of their time; on the other, some critics argue that the hegemonic powers of the Tudor and Stuart governments are so great that the state can neutralize all dissident behavior. Although Montrose offers his own distinctive response to the containment- subversion problem, he insists that a willingness to explore the political potential of writing is a distinguishing mark of New Historicism.

A final problem Montrose expects his New Historicist colleagues to engage might be called “the question of theory.” Even as he insists that cultural poetics is not itself a systematic paradigm for producing knowledge, he argues that the New Historicists must be well versed in literary and social theory and be prepared to deploy various modes of analysis in their study of writing and culture. Montrose finds notions of textuality from d e c o n s t r u c t io n and poststructuralism to be particularly useful for the practice of historical criticism, for their emphasis on the discursive character of all experience and their position that every human act is embedded in an arbitrary system of signification that social agents use to make sense of their world allow him and his colleagues to think of events from the past as texts that must be deciphered. In fact, these poststructuralist theories often underlie the cryptically chiastic formulations, such as “the historicity of texts and the textuality of history,” that appeal so much to the practitioners of cultural poetics. Other New Historicists invoke different interpretive perspectives, especially those found in the writings of Michel Foucault and Clifford Geertz , to aid their interpretive endeavors. The crucial point here is that virtually every New Historicist finds theory to be a potential ally.

Such, then, are the issues that shape the terrain of New Historicism. In what remains, I will comment in some detail upon the writings of three exemplary New Historicists, Stephen Greenblatt, Jonathan Goldberg, and Walter Benn Michaels. As a result, many significant contributors to this field will go undiscussed, but it is especially important to gain a sense of how these practitioners of cultural poetics actually interpret texts.

New Historicism: A Brief Note

In his introduction to Renaissance Self-Fashioning (1980), Greenblatt indicates that his book aims to chart the ways identity was constituted in sixteenth-century English culture. He argues that the scene in which his authors lived was controlled by a variety of authorities— institutions such as the church, court, family, and colonial administration, as well as agencies such as God or a sacred book—and that these powers came into conflict because they endorsed competing patterns for organizing social experience. From Greenblatt’s New Historicist perspective, the rival codes and practices that these authorities sponsored were cultural constructions, collective fictions that communities created to regulate behavior and make sense of their world; however, the powers themselves tended to view their customs as natural imperatives, and they sought to represent their enemies as aliens or demonic parodists of genuine order. Because human agents were constituted as selves at the moment they submitted to one of these cultural authorities, their behavior was shaped by the codes that were sponsored by the institution with which they identified, and they learned to fear or hate the Other that threatened their very existence.

Since authors were fully situated within this cultural system, Greenblatt contends that their writings both comment generally upon the political struggles that emerged within the Tudor state and register their complicated encounters with authorities and aliens. To prove his thesis, he analyzes self-fashioning in a number of significant Renaissance works, and he shows that these texts record sophisticated responses to a series of cultural problems. Greenblatt demonstrates that Thomas More’s late writings are the culmination of his engagement with theological controversy, for these letters reiterate his sense that his identity is shaped by his participation in the Catholic community, and they restate his belief that Protestant theology is an alien threat that should be rooted out of England. Edmund Spenser’s Bower of Bliss scene in The Faerie Queene encodes and relieves anxieties about the ways sexuality challenges the state’s legitimate authority, and Thomas Wyatt’ssatires explore whether an aristocrat can detach himself from a court society that has become wholly corrupt.

By consistently situating the texts he studies in relation to sixteenth-century political problems, Greenblatt avoids the formalist error of consigning writing to an autonomous aesthetic realm and produces analyses that accord with the New Historicist premise that critics can understand Renaissance works only by linking them to the network of institutions, practices, and beliefs that constituted Tudor culture in its entirety. And if one of the aims of cultural poetics is to explain how texts are both socially produced and socially productive, Greenblatt addresses this question directly in his chapter on William Tyndale. He argues there that the invention of the printing press converted books into a form of power that could control, guide, and discipline, and he proves that texts fashioned acceptable versions of the self by narrating the story of James Bainham, that ultimate creation of the written word. Following John Foxe, Greenblatt recounts that when Bainham publicly declared his Protestant faith, he spoke with “the New Testament in his hand in English and the Obedience of a Christian Man in his bosom,” and since the “Obedience” is the title of one of Tyndale’s most influential moral tracts, Greenblatt concludes that Bainham’s identity has been constituted by a text.

Stephen Greenblatt and New Historicism

While Greenblatt’s book distinctly advances the New Historicist project of rethinking the relationship between literature and society, it also investigates the other questions that Montrose uses to define cultural poetics. Since self-fashioning is a close analogue to Montrose’s own idea of subjectification, it is clear that much of Greenblatt’s attention is focused on the social processes by which identity is constituted. In his chapter on Christopher Marlowe’s plays, Greenblatt also offers his views on the question whether literature can generate effective resistance, and he concludes that the political ideologies and economic practices that both Marlowe and his characters seek to contest are ultimately too powerful to subvert.

Finally, concerning Greenblatt’s response to the question of theory, it seems fair to conclude that at the time he wrote Renaissance Self-Fashioning he had already decided that no single interpretive model could explain the full complexity of the cultural process New Historicism investigates. Although he invokes a vast array of approaches from a considerable number of disciplines, three of his theoretical borrowings are especially significant. Following Geertz, Greenblatt argues that every social action is embedded in a system of public signification, and this premise is responsible for one of the most spectacular features of his reading practice, namely, his ability to trace in seemingly trivial anecdotes the codes, beliefs, and strategies that organize an entire society. If cultural anthropology supplies Greenblatt with the techniques of thick description that he uses to interpret letters from colonial outposts, then Foucault offers him the theory of power that informs much of his work, for as his chapters on More and Tyndale demonstrate, Greenblatt views disciplinary mechanisms such as shaming, surveillance, and confession as productive of Renaissance culture, not as repressive of innate human potential. Lastly, in poststructuralist criticism from the 1970s and 1980s, Greenblatt finds corroboration of his idea that the self is a vulnerable construction, not a fixed and coherent substance, though he deviates somewhat from deconstructive analyses when he argues that culture, rather than language, creates the subject’s instability. Frankly, when considering his ability to forge these potentially contradictory theories into a powerful critical stance, one wonders who is more adept at self-fashioning, he or the writers he discusses.

In his introduction to James I and the Politics of Literature (1983), Jonathan Goldberg commends Greenblatt’s study of the relationship between Renaissance texts and society, and he claims that his book, like Greenblatt’s, will reveal “the social presence to the world of the literary text and the social presence of the world in the literary text” (Goldberg, James xv, quoting Greenblatt, Renaissance 5). But unlike Greenblatt, who analyzes the techniques that a number of competing institutions use to discipline behavior, Goldberg tends to focus on the ways political discourses circulate around a single authority, James I. According to Goldberg, James’s Roman rhetoric is filled with contradictions, two of which are especially important. First, while James wishes to maintain the integrity of the royal line from which he descends, he also claims that he is both self-originating and the world’s secret animating force. Second, while James refers to kingship as a kind of performance in which his thoughts are fully revealed, he also characterizes public display as necessarily obfuscating and opaque.

In a characteristically New Historicist manner, Goldberg offers a political interpretation of these inconsistencies, and he then proceeds to demonstrate that artistic productions replicate the structures of royal authority. Goldberg claims that James’s emphasis on self-origination is an effort to mystify his body, to free himself from his dubious family history and to derive his sovereignty from a transcendent and eternal world. This strategy allows the king to claim that all life springs from hisspiritual substance, but it also enables him to argue that he is unaccountable to the social world he governs. While the king used this doctrine of mystery and state secrecy to protect his political power, Renaissance writers appropriated his language to make sense of their own activities and experiences, b e n jo n s o n appeals to the theory of arcana imperii in his masques because he wants them to point beyond themselves to the royal patron who is responsible for their existence. John Donne uses James’s terms to represent the undiagnosable disease that festers within him as an undisclosed policy that governs a newly founded kingdom. If the discourse of the state secret infiltrates the body here, it also pervades the Renaissance conception of the family, for in an astonishing analysis of domestic portraits, Goldberg shows that the father, modeled on royal authority, generates his lineage but remains distant and unaccountable as he dreamily gazes away from his wife and children.

From even this brief summary, we see that Goldberg shares many of the enabling assumptions of Renaissance Self-Fashioning : he senses that all human activity is inevitably inscribed in a system of signification that organizes the ways agents understand their world; he views Renaissance literature as being inextricably related to sixteenth- and seventeenth-century social practices; and he conceives of the self as a culturally constituted entity that is shaped by structures of authority. The above account also hints that Goldberg’s theoretical orientation is heavily Foucauldian, for his description of the ways the body is inscribed within discourse echoes Foucault’s notion that disciplinary mechanisms swarm and produce their subtle effects even in the domains of human experience that seem intensely private and personal.

But how does Goldberg respond to the containmentsubversion problem, which is consistently investigated in New Historicist writing? We can answer this question by briefly summarizing the argument of his chapter “The Theatre of Conscience.” Goldberg here examines the ways Renaissance texts replicate the second contradiction inherent in James’s discourse, and he begins by suggesting that George Chapman’s Bussy D’Amboi s and William Shakespeare’s Henry V both depict characters who gain authority by using performative arts to conceal their plans and desires. But if these works concur with James’s sense that power can only be maintained through opaque self-dramatization, other texts invoke the royal rhetoric of obfuscating theatricality to challenge the king’s policies. Writers such as Jonson and Donne confidently satirize the tolerated licentiousness of James’s court because they recognize that if the monarch is aloof, unknowable, and unaccountable, then poets can never say anything that intentionally questions royal motives. And if the censor or the king himself raises doubts about an author’s loyalty, that writer can always cloak himself in the language of regal inscrutability and claim that his works, like James’s acts, were constantly being misread. Goldberg’s point, then, is that subversive behavior emerges from within absolutist discourse itself, and he implies that while such a structure allows writers to express feelings of disgust and contempt, it also ultimately contains the threat posed by gestures of dissent and rebellion.

New Historicism’s Deviation from Old Historicism

Goldberg’s work has helped to convince many Renaissance scholars that they should become practitioners of cultural poetics, and as a result New Historicism thrives in the field of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century English criticism. Since academics who work in other areas of literary studies have also found this reading strategy congenial, we should now briefly consider the way one of these figures has used New Historicist assumptions to interpret texts drawn from a later culture. In his introduction to The Gold Standard and the Logic of Naturalism (1987), Walter Benn Michaels states that his aim is to study how American writing is shaped by changes in economic production, distribution, and consumption that occurred after the Civil War, and his thesis is that the literary mode commonly called naturalism participates in and exemplifies a capitalist discursive system that is structured by a series of internal divisions. Each significant element of American economic practice—corporations, money, commodities, and identities— is intrinsically differentiated from itself, and since writing too is a part of this massive political formation, it must also display the logic of contradiction that drives mercantile culture.

Perhaps the chapter that most clearly illustrates Michaels’s powers as a reader is the one from which he borrows his book’s title. There Michaels discusses the late nineteenth-century debates between the goldbugs and the advocates of paper currency, and he shows that the controversy between these groups stems from competing assumptions about the nature of money itself: while the defenders of precious metals sense that the value of gold resides in its innate beauty, their opponents think that gold is only desirable because it is a representation of money. Having delineated these opposing views, Michaels shows that both of these positions are illustrated in Frank Norris’ s McTeague , for the narrative’s two misers are motivated by these contradictory models of wealth. Trina’s hoarding of gold enacts her society’s presumption that metal is the money itself, and her act encodes her culture’s fear that should preciousmetals stop circulating, civilization will be undone. Zerkow’s collecting of junk embodies his world’s recognition that if wealth is an effect of representation, then anything can be converted into money, and his behavior demonstrates that a discrepancy between material and value is the enabling condition of capital. Michaels’s point in producing this analysis is not that either of these theories of wealth is truer than the other but that the tension between them is a constitutive element of the discourse of naturalism and that any literary text produced at this time will display both views toward money.