An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Student satisfaction and interaction in higher education

Wan hoong wong.

1 Singapore Institute of Management, Singapore, Singapore

2 University of Western Australia, Perth, Australia

Elaine Chapman

Associated data.

Data will be made available on request to the corresponding author.

No non-commercial software or custom code used in the study.

Given the pivotal role of student satisfaction in the higher education sector, myriad factors contributing to higher education satisfaction have been examined in the literature. Within this literature, one lesser-researched factor has been that of the quality and types of interpersonal interactions in which students engage. As existing literature has yet to fully explore the contributions made by different forms of interaction to student satisfaction in higher education, this study aimed to provide a more fine-grained analysis of how different forms of interaction between students, their peers and their instructors relate to different aspects of student satisfaction. A total of 280 undergraduate students from one of the largest higher education institutions in Singapore participated in the study. Results provided an in-depth analysis of eight aspects of student satisfaction (i.e. satisfaction with the program, teaching of lecturers, institution, campus facilities, student support provided, own learning, overall university experience and life as a university student in general) and suggested that the different aspects of student satisfaction were associated with three different forms of interaction: student–student formal, student–student informal and student-instructor.

Introduction

In higher education (HE), student satisfaction is vital both for the success of institutions and for that of individual students, particularly in our current global climate. Rapid technological advancements, in particular, have intensified competition in the HE sector in recent years. In Singapore and other countries presently, not only do HE institutions need to compete for students with branch campuses of foreign institutions set up locally, but also with digital platforms that offer massive open online courses (MOOCs) that allow students to learn without being attached to specific institutions. By 2015, there were already about 220 international branch campuses of overseas universities in operation worldwide (Maslen, 2015 ).

In this cut-throat context, maximising student satisfaction has become a primary focus of many universities and colleges, irrespective of their physical location. Such move is no surprise considering that student satisfaction is now often used as a measure of HE institutions’ performance (Jereb et al., 2018 ; McLeay et al., 2017 ). As reflected in recent studies on the impact of COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) upon the HE sector, student satisfaction has been incorporated as an index to measure the extent to which attendant disruptions to services have affected the quality of HE services received by students (e.g. Duraku & Hoxha, 2020 ; Shahzad et al., 2020 ). However, this does not imply that HE institutions have no other considerations when it comes to making student satisfaction their top priorities to pursue service excellence. As discussed in the subsequent section, giving what students want most to keep them satisfied can have undesirable effects on students as well as on institutions. Hence, any discussion that frames the debate on student satisfaction should go beyond its role as a metric to measure HE institutions’ performance.

The vital role of student satisfaction in higher education

Students’ satisfaction with the quality of the education services they receive is a crucial index of the performance of HE institutions in today’s world (Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Santini et al., 2017 ; Weingarten et al., 2018 ). Student satisfaction figures are also used as a means by which to distribute precious resources across HE institutions in many countries. For instance, the Australian government has recently announced the adoption of the performance-based funding (PBF) scheme to be used in future years, in which the provision of funding to Australian universities will be based, in part, on the quality of the overall student experience (Australian Department of Education, Skills and Employment, 2020 ). Student satisfaction is one of the indices that may be used to measure the overall student experience within this scheme (Commonwealth of Australia, 2019 ).

Be it academic programs or the peripheral student support services, the ability to provide high-quality services to students has been regarded by many scholars as crucial for HE institutions to withstand the increasingly competitive HE environments in which they must now operate (Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Lapina et al., 2016 ; McLeay et al., 2017 ; Paul & Pradhan, 2019 ). Higher service quality, driven by outstanding learning processes and high levels of satisfaction with the services delivered, has been deemed to be what will “set a HE institution apart” from its rivals (McLeay et al., 2017 ).

Numerous more immediate commercial benefits derived from high levels of student satisfaction have also been highlighted in the literature. When satisfied with the quality of services provided, students are more likely to continue with their enrolled institutions and recommend them to prospective students (Mihanović et al., 2016 ). Student loyalty is another reward that HE institutions can gain from having highly satisfied students. As loyal students are more likely to engage in alumni activities, greater alumni engagement can in turn benefit the institutions through the provision of direct financial support, as well as attractive employment opportunities for current graduates (Paul & Pradhan, 2019 ; Senior et al., 2017 ).

Concurrently, with rising government interventions in various countries to regulate their HE sectors, there have been increasing calls for HE institutions to improve their service quality (Hou et al., 2015 ; Dill and Beerkens, 2013 ). As a result, the use of quality assurance regimes by governments to regulate HE has become more prominent worldwide (Jarvis, 2014 ). In a recent report, it was estimated that the tuition fees for bachelor programs in some OECD countries (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) have risen as much as 20% between 2007 and 2017 (OECD, 2019 ). With substantial cost outlays involved in the provision of HE, concerns over returns on financial investments are not limited to students and parents, but apply also to entire governments (Lapina et al., 2016 ; Weingarten et al., 2018 ). With the costs of providing HE continue to rise, many HE providers are becoming increasingly concerned about how best to meet the needs and expectations of students and keep them satisfied (Weingarten et al., 2018 ). Such concerns were valid particularly when student satisfaction was linked numerous institutional aspects. As discovered in a study conducted by De Jager and Gbadamosi ( 2010 ) on 391 students from two African universities, student satisfaction was reported to relate significantly to various institutional aspects including academic reputation, accommodation and scholarship, location and logistics, sports reputation and facilities and safety and security.

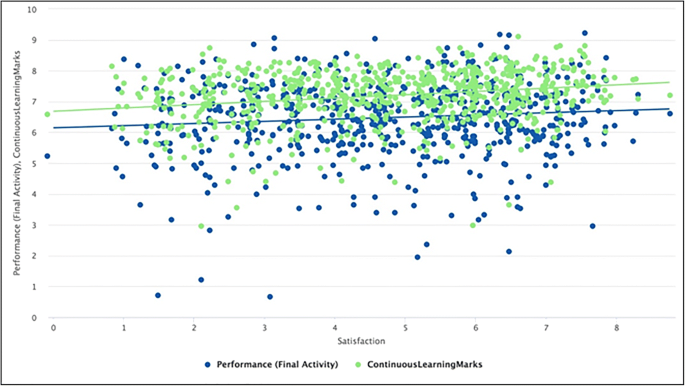

Student satisfaction is not only crucial to institutions, but also to learners themselves. Students’ satisfaction with their learning experiences is not, however, related simply to the feelings they have about the quality of the education services they receive. Within the HE literature, high levels of student satisfaction have also been linked to the attainment of important learning outcomes in HE. For instance, scholars have recognised that student satisfaction may influence outcomes such as academic achievement, retention and student motivation (Aldridge & Rowley, 1998 ; Duque, 2014 ; Mihanović et al., 2016 ; Nastasić et al., 2019 ). Evidently, such hypothesised links between satisfaction and key learning outcomes have received some empirical support to date. For instance, positive associations between student satisfaction and student performance have been reported in two HE-based studies, with one using student grades as performance indicators (van Rooij et al., 2018 ) and the other using mastery of knowledge and general success of the faculty as performance indicators (Mihanović et al., 2016 ). In contrast, strong negative associations between student satisfaction and attrition were reported by Duque ( 2014 ).

However, in considering student satisfaction with the quality of education services, the literature highlighted some key concerns of treating students as customers. Focusing on satisfying students in the same way companies satisfying their customers may result in HE institutions emphasising less on what students need most as learners, such as achieving learning outcomes or training to be work-ready, and more on what they want most in order to feel satisfied as fee payers (Calma and Dickson-Deane, 2020 ). What students want best for themselves may not necessarily be beneficial for them to attain quality education, for that they may adopt short-term perspective and prefer assessment that they can score well rather than those that they can learn well (Guilbault, 2016 ). Additionally, with a customer mindset, students may also feel they are entitled to be awarded a degree for the fees they have paid, resulting in shifting their responsibility to learn and be engaged to institutions (Budd, 2017 ). If student expectations are to be met by institutions in order to keep “customers” satisfied, this can subsequently lead to grade inflation (Hassel & Lourey, 2005 ). As such, although it is crucial for HE institutions to improve the quality of education services provided to students by meeting their expectations and keeping them satisfied, it should be noted that such action may generate undesirable effects if students were treated squarely as customers.

The construct of student satisfaction and its predictive factors

In general, student satisfaction can be viewed as a short-term attitude, which relates to students’ subjective evaluations of the extent to which their expectations of given educational experiences have been met or exceeded (Elliot & Healy, 2001 ; Elliot & Shin, 2002 ). As students form numerous expectations in relation to their educational experiences, many scholars conceptualise student satisfaction as a multidimensional construct (Hanssen & Solvoll, 2015 ; Jereb et al., 2018 ; Nastasić et al., 2019 ; Weerasinghe et al., 2017 ).

In Sirgy et al.’s ( 2010 ) framework, for instance, overall satisfaction with college life was broken down into three components, which represented satisfaction with academic aspects, social aspects and college facilities and services. Similarly, in investigating university students’ views of their academic studies, Wach et al. ( 2016 ) measured satisfaction using items across three dimensions of satisfaction. These related to the content of learning (i.e. the joy and satisfaction felt by students on their chosen preferred majors), the conditions of learning (i.e. students’ satisfaction with the terms and conditions of the academic programs) and personal coping with learning (i.e. students’ satisfaction with their own ability to cope with academic stress).

The recognition that student satisfaction is a multidimensional construct is also evident in the identification of numerous dimensions that contribute to HE students’ overall satisfaction levels. Academic aspects comprise one such set of key contributors to student satisfaction in HE. These relate to considerations such as the perceived quality of teaching, feedback provided by instructors, teaching styles of instructors, quality of learning experiences and class sizes (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004 ; Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Duque, 2014 ; Jereb et al., 2018 ; Nastasić et al., 2019 ; Paul & Pradhan, 2019 ; Weerasinghe et al., 2017 ). More general attributes of the courses in which students are enrolled (e.g. curriculum, course content and teaching materials) have also been cited as significant (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004 ; Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Duque, 2014 ; Weerasinghe et al., 2017 ).

Empirical studies have attested to the relevance of the above-named attributes in determining HE students’ satisfaction levels (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004 ; Bell & Brooks, 2018 ; Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Nastasić et al., 2019 ; Siming et al., 2015 ). However, this list is by no means exhaustive in describing the factors that students will consider in providing satisfaction ratings. More generic, institution-wide attributes, such as ease of access to student services and the level of infrastructure support provided by an institution (e.g. transportation and boarding services, internet access and administrative services), as well as the facilities it offers (e.g. teaching facilities, leisure and sports facilities, IT facilities and study areas) have also been recognised by scholars to contribute to HE students’ satisfaction levels (Aldemir & Gülcan, 2004 ; Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Duque, 2014 ; Hanssen & Solvoll, 2015 ; Jereb et al., 2018 ; Weerasinghe et al., 2017 ). Less tangible aspects of students’ experiences such as the reputation and impressions of the institution (Butt & Rehman, 2010 ; Duque, 2014 ; Hanssen & Solvoll, 2015 ; Jereb et al., 2018 ), student centeredness and campus climate (Elliot & Healy, 2001 ) and students’ own life experiences while at college (Mihanović et al., 2016 ; Nastasić et al., 2019 ; Weerasinghe et al., 2017 ) have also been noted.

Interaction and student satisfaction in higher education

Beyond the factors above, the recent student satisfaction literature has highlighted the potential role played by students’ interpersonal interactions in HE as a key predictor of student satisfaction levels. This is to be expected, given the vital role of interpersonal interaction in learning. According to the social constructivist paradigm, learning is an inherently social process, in which interpersonal interactions are critical in the construction of knowledge and understanding (Pritchard & Woollard, 2013 ). Studies have affirmed that HE students recognise the importance of interpersonal interactions with their classmates and university staff in furthering their content learning (Hurst et al., 2013 ). In Burgess et al.’s ( 2018 ) comprehensive study using the data of millions of university students from the UK’s National Student Survey (NSS), the aspect of “social life and meeting people” was recognised as one of the key determinants contributing to university satisfaction despite it has not been included in their study.

In general, two forms of interaction have been examined in relation to student satisfaction in HE: student-faculty and student–student interactions. The proposed importance of student-faculty interactions in determining student satisfaction levels in HE is reflected in both the theoretical and the empirical literature. In one very early review, Pascarella ( 1980 ) reported that student-faculty informal contact was positively associated with college satisfaction, alongside other educational outcomes. Similarly, in Aldemir and Gülcan’s ( 2004 ) conceptual framework, the authors included the variable “communication with instructors both in and outside classroom” as one of the factors that contributed to university students’ satisfaction levels. This variable was then found empirically significant in predicting satisfaction levels in a sample of more than 300 Turkish university students.

Table Table1 1 provides a broad summary of empirical studies that have examined either student-faculty or student–student interpersonal interactions as predictors of student satisfaction in HE. Collectively, these studies have reported significant associations between satisfaction and both types of interactions. Although most have focused on the context of online learning, as Kuo et al. ( 2014 ) argued, high-quality interactions are important in all forms of education, whether technology-based or more traditional.

Empirical studies on interaction and student satisfaction in HE

The crucial role of interaction in HE has been underscored more recently by the concerns over the loss of social contact and socialisation following the suspension of in-person classes due to the COVID-19 outbreak which has impacted the students negatively (UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean, 2020 ). HE students have also raised their own concerns over the quality of education they receive in online, as compared to in-person formats, which differ primarily in terms of the level of interpersonal interaction they afford (Ang, 2020 ). Such concerns make clear the perceived significance of interpersonal interaction in the overall HE learning experience.

It should be noted that there is a need to consider the role of students’ demographic background in examining the relationship between interaction and student satisfaction, with the evidence in the literature indicating that students’ demographic profiles can moderate the types and levels of interpersonal interactions they have with their peers or instructors. In a study conducted by Kim and Sax ( 2009 ) using data on 58,281 US students, differences in the frequency of student-faculty interactions were attributed to gender, alongside other demographic variables (race, social class and first-generation status). Similarly, in a study by Criado-Gomis et al. ( 2012 ) on 1000 graduates from two Spanish universities, significant differences were seen in the quality of interactions between male and female students. At around the same time, Ke and Kwak’s ( 2013 ) study of 392 students from a US university indicated that age was significantly correlated with the perceived quality of peer interactions that occurred in online learning environments.

Rationale and aims of the present study

The literature suggests a wide range of attributes that may contribute to student satisfaction levels in HE. This aligns with the propositions of Jereb et al. ( 2018 ), who underscored the complexity of student satisfaction and the myriad factors that influence it. Existing scholarly work is yet to provide a complete understanding on the different aspects of HE students’ satisfaction and establish concrete links between these aspects and the different forms of interpersonal interactions in which HE students may engage.

From Table Table1, 1 , studies conducted thus far have tended to focus on measuring student satisfaction using generic or unidimensional measures. Similarly, the measurement of interpersonal interaction has typically been restricted to only two dimensions (student–student or student-instructor), though evidence from the literature suggests a need to divide these further into formal and informal forms (Kraemer, 1997 ; Mamiseishvili, 2011 ; Meeuwisse et al., 2010 ). By taking a broader view of student satisfaction and interpersonal interactions, the present study aimed to provide a more fine-grained analysis of how different aspects of HE students’ satisfaction levels may relate to different forms of interpersonal interaction.

It has been noted that what contributes to student satisfaction levels can be highly contextual. In defining overall student satisfaction in HE, Duque ( 2014 ) contended that overall satisfaction with an organisation will be based on all encounters and experiences a consumer has with that particular organisation. It is acknowledged, therefore, that the results presented in this paper may be particular to the context in which the study was conducted (the details of the participating institution and the participants selected for this research were provided in the “ Method ” section below).

Three research questions were formulated to guide the research conducted in this study:

- How satisfied were the students with different aspects of the HE institution studied, and how did satisfaction levels vary across these different aspects?

- How did different forms of interpersonal interaction relate to different aspects of these students’ satisfaction levels?

- Did the types of interpersonal interaction in which students engaged vary with students’ gender and age?

Participants and setting

Students participated in this research were enrolled 14 international undergraduate degree programs from the UK, offered by the participating institution. The institution is one of the largest private HE institutions in Singapore at the time of the study. Established in the 1960s, the institution admits approximately 17,000 local and foreign students. Its physical campus offers a variety of facilities such as library, performing art theatre, cafeterias and sport facilities. The institution also offers a wide range of services such as counselling and career advisory services.

These students were invited to participate in an online survey in the middle of the 2018–2019 academic year, to report their satisfaction levels with different aspects of their learning experiences, and on the forms of interpersonal interactions in which they typically engaged. In all, 280 students provided complete responses to the survey. Of this sample, 105 (37.50%) were males and 175 (62.50%) were females. The respondents were aged between 18 to 40 years old, with an overall mean of 22.79 years ( SD = 2.40). One hundred and ninety-seven (70.36%) were continuing students, while 83 (29.64%) were final year students.

Student satisfaction

Drawing upon the existing literature, the present study focused on eight aspects of student satisfaction, classified into three categories (academic, institution and university life). Each of these eight aspects was represented by a single item in the student satisfaction measure, to which students responded on a 7-point rating scale (see Table Table2 2 below). The rated satisfaction scores obtained for all the eight aspects form the eight dependent variables, each to be predicted by the four interaction variables (see next section).

Item statements measuring student satisfaction levels on eight different aspects

Note: Item 7 and item 8 may appear similar, but the two items are not the same. While item 7 focuses more on the experiences in attaining university education, item 8 relates more broadly to the overall university life lived out by a student

Interaction

Following Meeuwisse et al.’s ( 2010 ) model, four forms of interaction were measured in the study, each representing a different dimension of interpersonal interaction. Each was measured by a number of items in the interpersonal interaction measure, as shown in Table Table3. 3 . In the survey, respondents were asked to select the items that related to them, based on their own experiences of interacting with their peers and instructors/lecturers. Therefore, for each respondent, the total score obtained for each of the four types of interpersonal interaction was simply a summed total based on selected items within each type. The four scores obtained formed the four independent variables (i.e. predictors) used to predict each of the eight satisfaction variables (the dependent variables) explained above.

Item statements measuring four different forms of interaction

Note: Not all item statements are included in the table. For each form of interaction, only one of the items is presented here for reference

The online survey was hosted on the Qualtrics platform, a web-based survey tool that allows respondents to answer online survey questions. Institutional ethics approval was first obtained prior to conducting the survey. Email invitations were sent to students to participate in the online survey. The purpose of the survey, time required to answer the survey, identity confidentiality and data protection assurances were all stated in the email. Participants were asked to consent to participate before entering the survey. Two email reminders following the initial invitations were also sent to increase participation rates. A pilot study, conducted before the launch of the survey, indicated that the instructions and questions within the survey were clear to a pilot sample of 14 students who attended the same university as the intended survey participants.

The analysis was divided into three parts to address the three research questions. Descriptive statistics and repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to analyse and compare levels of student satisfaction across the eight aspects identified, to address research question 1 (How satisfied were the students with different aspects of the HE institution studied, and how did satisfaction levels vary across these different aspects?). This provided a broad overview of student satisfaction levels within the specific HE institution in which the study was conducted.

Stepwise regression and correlation analyses were conducted to address research question 2 (How did different forms of interpersonal interaction relate to different aspects of these students’ satisfaction levels?) via SPSS V26. Using the satisfaction ratings for each identified aspect of student experience (program, institution, student’s own learning, teaching of lecturers, student support provided, life as a university student in general, campus facilities and overall university experience) as the dependent variables and scores for the four types of interpersonal interaction (student–student formal interaction, student–student informal interaction, student-instructor formal interaction and student-instructor formal interaction) as independent variables, eight regression models were formulated. Results obtained were interpreted and analysed to uncover more specific relationships between different dimensions of student satisfaction and interpersonal interaction.

Bivariate correlations between two demographic variables (age and gender) and the four interaction variables were examined to address research question 3 (Did the types of interpersonal interaction in which students engaged vary with students’ gender and age?). The results obtained were analysed to reveal how the age and gender of the students were associated with their engagement in different forms of interpersonal interaction, and thus, suggest how these variables might contribute differentially to student satisfaction levels.

Five multivariate outliers were detected using the Mahalanobis distances, tested at a significance level of 0.001 and subsequently removed from the analysis. This is because the presence of outliers can distort the statistical analysis performed (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013 ). This resulted in only 275 cases being used in the analyses for the study.

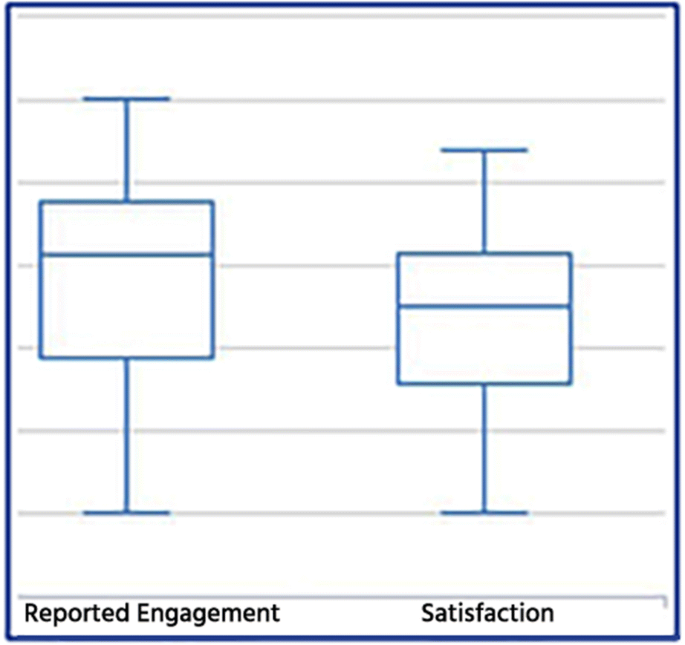

Student satisfaction on different aspects of the institution

The descriptive statistics presented in Table Table4 4 suggest that in general, respondents were favourable about their institution in terms of the different satisfaction elements surveyed. The mean satisfaction score for all eight aspects was higher than 4 (midpoint of the rating scale). For seven of the eight aspects of satisfaction, the median and mode scores were recorded at 5. The proportion of respondents with ratings of 5 and above was in the range of 59.27–76.36% for the same seven aspects.

Descriptive statistics of the eight aspects of student satisfaction ( n = 275)

Comparing different aspects of satisfaction, the respondents were most satisfied with the two academic aspects, particularly with the academic program in which they were enrolled. For both “program” and “teaching of the lecturers”, the mean scores were the highest among all the eight aspects of student satisfaction, and more than 70% of the respondents gave a rating of 5 or above for these two aspects.

They were least satisfied with the items referring to their university lives while studying at the institution. The range of mean scores for the three aspects within this set (4.36–4.78) was generally lower than for other aspects of satisfaction (academic, 4.96–5.12; institution, 4.49–4.85). The item “My life as a university student in general” attracted a particularly low number of positive ratings, with mean, median and mode scores ranked lowest for this item among all the eight aspects of satisfaction surveyed. Less than 50% of respondents gave a rating of 5 or above for this aspect. Among the three aspects surveyed, however, the respondents were most satisfied with “my own learning”.

Among all the three institutional aspects surveyed, “institution” was the aspect with the highest mean score, and the only item in this group in which more than 60% of respondents gave a rating of 5 or above. Satisfaction levels for “campus facilities” and “Student support provided” were notably lower, even when compared with some of the university life aspects.

The results from the repeated measures ANOVA showed a significant difference across the eight satisfaction mean scores, F (7,268) = 14.79, p < 0.001. The effect size (partial η 2 ) was 0.28, indicating that some 28% of variance in satisfaction scores was attributable to the type of satisfaction measure used. The pairwise comparisons also showed that each of the satisfaction mean scores was significantly different from at least two other mean satisfaction mean scores. The mean scores for satisfaction in terms of “program” and “my life as a university student in general”, in particular, were different from the mean satisfaction scores of the other six aspects measured (Table (Table5 5 ).

Pairwise comparisons of different satisfaction mean scores ( n = 275)

* p < 0.05

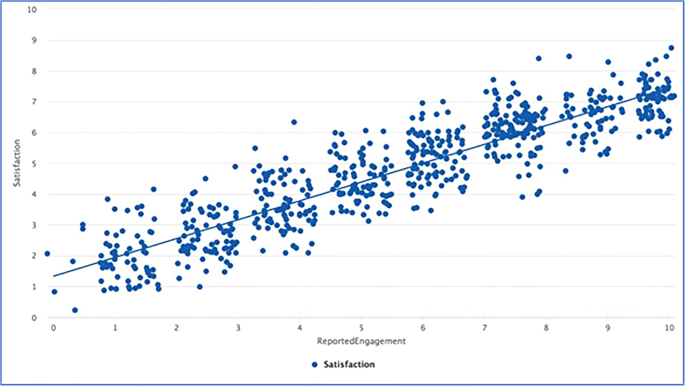

Interaction and student satisfaction

The bivariate correlations between the eight satisfaction variables and the four interaction variables are provided in Table Table6. 6 . To explore relationships between these eight variables and the interaction variables, separate stepwise regression analyses were performed, in each case, with satisfaction ratings as the dependent variable, and the four interaction variables entered as predictors.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of variables examined in the stepwise regression analysis ( n = 275)

** p < 0.01

Relationships between interaction and student satisfaction with academic aspects

The two stepwise regressions performed for satisfaction scores associated with academic aspects are shown in Table Table7. 7 . In both cases, the analysis stopped after one step. For satisfaction ratings related to the “program”, student–student informal interactions were identified as the only significant predictor, while for satisfaction with “teaching of the lecturers”, student-instructor formal interaction was identified as the only significant predictor.

Stepwise regression: student satisfaction on interaction ( n = 275)

Relationships between interaction and student satisfaction with institutional aspects

Three stepwise regressions were performed with the satisfaction scores for “institution”, “campus facilities” and “student support provided” as the dependent variables, respectively. Again, the analysis stopped after one step for satisfaction related to the “institution” and also for “student support provided”. Student–student informal interactions were identified as the only significant predictor of both ratings. There were no significant predictors of satisfaction in terms of “campus facilities”.

Relationships between interaction and student satisfaction with university life

Three stepwise regressions were performed for the satisfaction scores related to “my own learning”, “my overall university experience” and “my life as a university student in general” as the dependent variables. Again, the analysis stopped after one step in all three cases. Student–student informal interaction was identified as the only significant predictor of satisfaction on all three aspects of the students’ self-reflective experiences. The association between student–student informal interaction and satisfaction with respect to “my own learning” and “my overall university experience” was slightly stronger than for “my life as a university student in general”.

Comparison between the four forms of interaction in predicting student satisfaction

From the regression analysis, each of the four interaction variables was identified as a significant predictor of at least one aspect of student satisfaction. At the same time, no aspects of satisfaction were predicted by more than one predictor. Furthermore, satisfaction with campus facilities was not predicted by any of the four interaction variables.

Overall, student–student informal interaction was the only variable that significantly predicted more than one satisfaction aspect (one academic aspect, one institutional aspect and all three university life aspects). None of the other three interaction variables significantly predicted more than one satisfaction aspect, with student–student formal interaction significantly predicting only “student support provided”. Student-instructor formal interactions significantly predicted ratings in terms of “teaching of the lecturers”. Student-instructor informal interactions did not significantly predict any of the satisfaction variables.

Associations between demographic and interaction variables

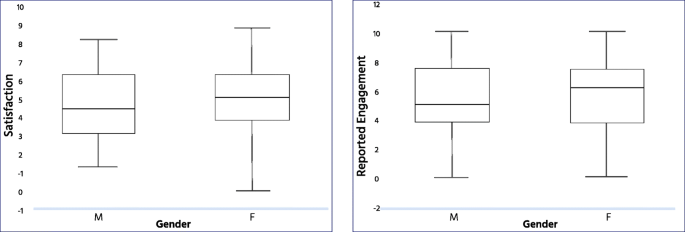

Table Table8 8 presents bivariate correlations between the four interaction variables and the two demographic variables of age and gender. Significant positive correlations were found between the two demographic variables and student-instructor formal instruction. The positive correlation between gender and student-instructor formal interaction indicates that male students were likely to have more formal interactions with their instructors than were female students. In the case of age, the significant positive correlation indicates that older students (this can be taken as those above the mean age of 22.79 years in the participating institution) were more likely to have formal interactions with their lecturers than were younger students (those below the mean age of 22.79 years in the participating institution).

Bivariate correlations between interaction and demographic variables

No significant correlations were found between the two demographic variables and any other interaction variables.

The present study aimed not only to provide a more in-depth analysis of different aspects of HE students’ satisfaction in one HE institution in Singapore, but also to provide a more nuanced analysis of relationships between these aspects and different forms of interpersonal interactions in which HE students engaged. The following sections discuss the findings of the study in greater depth, to address the three formulated research questions.

Student satisfaction on academics, institutions and university life

In addressing research question 1 (How satisfied were the students with different aspects of the HE institution studied, and how did satisfaction levels vary across these different aspects?), while the findings show that students were generally satisfied with the different aspects surveyed, satisfaction levels were not the same across different aspects. This reinforces the notion that student satisfaction in HE ought to be treated as a multidimensional construct. Findings also confirmed that the differences across various satisfaction levels were statistically significant.

More importantly, the findings suggest that general satisfaction as university students requires the fulfilments in aspects beyond what most institutions are currently providing to their students. As reflected in the results, the respondents’ life satisfaction as university students was noticeably lower than satisfaction attained for all other aspects. Not only did “my life as a university student in general” have the lowest satisfaction mean score among all satisfaction aspects measured, it was also noted that its mode and median scores were lower than the midpoint score of 4. As depicted in Rode et al.’s ( 2005 ) and Sirgy et al.’s ( 2010 ) frameworks, HE students’ life satisfaction depends upon on satisfaction attained from a wide range of academic and non-academic aspects.

Analysing the different aspects of satisfaction separately as was done here would provide more nuanced feedback to HE institutions, empowering them further to focus on various aspects of the services they provide to enhance student learning experiences and satisfaction. In this case, the fact that satisfaction with student support was notably lower than the ratings obtained for most of the other satisfaction aspects, the results strongly suggest that enhancing the usual institutional aspects such as campus facilities or administrative services will not be the most effective approach to enhancing student satisfaction. As indicated in Kakada’s ( 2019 ) study, student satisfaction was found positively related to technology, academic, social and service supports provided.

The role of interaction in higher education student satisfaction

Through research question 2 (How did different forms of interpersonal interaction relate to different aspects of these students’ satisfaction levels?), the study aimed to provide a more nuanced analysis of relationships between interpersonal interactions and student satisfaction in HE, by examining how each specific form of interaction related to different aspects of student satisfaction.

Results indicated that student satisfaction in HE was not only explained by who the students interacted with (peers vs. instructors), but also how they interacted with these individuals (either in a formal or an informal format). With three forms of interaction (student–student formal, student–student informal and student-instructor formal) found to be significant predictors of different aspects of satisfaction, this suggests that how the students engage with their peers and lecturers was also vital in explaining their satisfaction with their HE experiences. This further reaffirms the notion that both formal and informal interactions are crucial in HE as posited in Tinto’s, 1975 model of college student attrition (Tinto, 1975 ).

The results also underscored the relative importance of different forms of interpersonal interaction in explaining different aspects of student satisfaction. From the results, student–student informal interaction was significantly associated with satisfaction in all three aspects studied—academic, institution and university life. This suggests that student–student interaction could be the most critical form of interaction in terms of student satisfaction levels. Other forms of interaction were also significantly associated with specific aspects of satisfaction. Student-instructor formal interaction was a significant predictor of HE students’ satisfaction with the teaching of their instructors, while student–student formal interaction significantly predicted satisfaction with the student support provided by the institution. As such, the different forms of interaction appear to play complementary roles in predicting students’ overall satisfaction levels. With consideration on the specificity of different forms of interaction and different aspects of satisfaction, this adds greater depth to the existing literature in discussing the role of student–student and student-instructor interactions as predictors of student satisfaction as most past studies tend to draw limited distinction between different forms of interactions, or between different aspects of satisfaction (see Chang & Smith, 2008 ; Palmer & Koenig-Lewis, 2011 ).

The more granular level of findings on the relationship between interaction and student satisfaction have several possible implications for practice in the HE context. First, the findings suggest a need for HE institutions to recognise the vital role of student–student informal interactions as a predictor of HE students’ satisfaction levels. This finding aligns with the propositions of other scholars in the field. For example, Meeuwisse et al. ( 2010 ) posed that students’ informal relationships with their peers are vital in developing their sense of belonging. In a separate study conducted by Senior and Howard ( 2014 ), it was found that collaborative learning was fostered through friendship groups in which students interact with one another to develop conceptual understanding. From a broader perspective, this finding is consistent with the notion that peers play a significant role in HE student development. In Astin’s 1993 landmark study involving more than 20,000 college students, it was suggested that peer influences had contributed significantly to the growth and development of undergraduate students (Feldman & Astin, 1994 ). Thus, HE institutions who wish to bolster student satisfaction levels could identify ways to establish structures that foster more frequent and higher quality informal student–student interactions. As indicated in Burnett et al.’s ( 2007 ) study, the frequency and intensity of interaction between students and instructors and peers contributed to the students’ satisfaction levels.

Second, with the findings indicating the need to improve student support, the institution concerned should incorporate the element of formal student–student interaction in the provision of student support. One such initiative is the peer-to-peer support programs. Within the literature, such support programs have been reported to have positive impacts on HE learning in different studies (Arco-Tirado et al., 2019 ; Backer et al., 2015 ; Munley et al., 2010 ). As the institution concerned has already put in place a peer tutoring program (called Peer-Assisted Learning Program), it could also consider fostering greater student–student formal interaction in other support areas to further improve student satisfaction, as recommended by Kakada et al. ( 2019 ).

Age and gender were also found to be significantly associated with student-instructor formal interactions, which implies that institutions could consider age and gender differences in designing such structures. For example, given that male students were likely to have a greater number of formal interactions with their lecturers, HE institutions may need to consider more differentiated practices that faculty members can adopt to ensure that new female students engage regularly in formal interactions with them.

Overall, the more nuanced analyses provided by the present study not only expand previous understandings of student satisfaction and interaction in the context of HE, but also offer practical insights upon which HE institutions can draw to elevate their students’ satisfaction levels. From the findings, it is suggested that HE institutions should evaluate more specifically different aspects of student satisfaction on a regular basis, as well as focusing upon enhancing the quality and quantity of interpersonal interactions in which students regularly engage.

It should be noted that, given the highly contextualised nature of student satisfaction research (Santini et al., 2017 ), the generality of the present study may be limited to universities that are similar to the one that participated in the present study. Future research should, therefore, seek to determine whether the results of the present study generalise to other contexts. The study could also be replicated with students studying at other levels (e.g. the postgraduate level) or those with particular profiles (e.g. international students, students at risk or students from minority ethnic group).

Also, as a construct that relates closely to attitudes and expectations, student satisfaction is likely to change over time. As such, research on student satisfaction in HE should be a continual process as no single study—conducted at a specific timepoint—can entirely capture the changing nature of student satisfaction over time. Thus, HE institutions themselves are likely to be in the best position to evaluate the factors which predict their own students’ satisfaction levels, ideally, as an element of regular, ongoing quality improvement efforts.

Data availability

Code availability, declarations.

This research was approved by the University of Western Australia Human Ethics Committee, Approval Number RA/4/20/4756.

All participants were required to provide consent for participation online, prior to entering the survey.

All participants were required to provide consent for publication online, prior to entering the survey.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Aldemir C, Gülcan Y. Students satisfaction in higher education: A Turkish case. Higher Education Management and Policy. 2004; 16 (2):109–122. doi: 10.1787/hemp-v16-art19-en. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aldridge S, Rowley J. Measuring customer satisfaction in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education. 1998; 6 (4):197–204. doi: 10.1108/09684889810242182. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ang, J. (2020, August 23). Hopes up for S’poreans eager to return to Aussie unis. The Straits Times . Retrieved September 21, 2020, from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/education/hopes-up-for-sporeans-eager-to-return-to-aussie-unis

- Arco-Tirado, J., Fernández-Martín, F., & Hervás-Torres, M. (2019). Evidence-based peer-tutoring program to improve students’ performance at the university. Studies in Higher Education (Dorchester-on-Thames) , 1–13. 10.1080/03075079.2019.1597038

- Australia. Department of Education, Skills and Employment. (2020). Performance-based funding for the Commonwealth Grant Scheme . Retrieved January 2, 2021, from https://www.education.gov.au/performance-based-funding-commonwealth-grant-scheme

- Backer LD, Keer HV, Valcke M. Promoting university students metacognitive regulation through peer learning: The potential of reciprocal peer tutoring. Higher Education. 2015; 70 (3):469–486. doi: 10.1007/s10734-014-9849-3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bell A, Brooks C. What makes students satisfied? A discussion and analysis of the UK’s national student survey. Journal of Further and Higher Education. 2018; 42 (8):1118–1142. doi: 10.1080/0309877X.2017.1349886. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Budd R. Undergraduate orientations towards higher education in Germany and England: Problematizing the notion of “student as customer” Higher Education. 2017; 73 (1):23–37. doi: 10.1007/s10734-015-9977-4. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burgess A, Senior C, Moores E. A 10-year case study on the changing determinants of university student satisfaction in the UK. PLoS ONE. 2018; 13 (2):e0192976–e0192976. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0192976. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Burnett K, Bonnici LJ, Miksa SD, Kim J. Frequency, intensity and topicality in online learning: An exploration of the interaction dimensions that contribute to student satisfaction in online learning. Journal of Education for Library and Information Science. 2007; 48 (1):21–35. [ Google Scholar ]

- Butt B, Rehman K. A study examining the students satisfaction in higher education. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 2010; 2 (2):5446–5450. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.03.888. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Calma A, Dickson-Deane C. The student as customer and quality in higher education. International Journal of Educational Management. 2020; 34 (8):1221–1235. doi: 10.1108/IJEM-03-2019-0093. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Chang SH, Smith RA. Effectiveness of personal interaction in a learner-centered paradigm distance education class based on student satisfaction. Journal of Research on Technology in Education. 2008; 40 (4):407–426. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2008.10782514. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Commonwealth of Australia. (2019). Performance-based funding for the Commonwealth Grant Scheme: Report for the Minister for Education – June 2019 . Retrieved September 8, 2020, from https://docs.education.gov.au/system/files/doc/other/ed19-0134_-_he-_performance-based_funding_review_acc.pdf

- Criado-Gomis, A., Iniesta-Bonillom, M. A., & Sanchez-Fernandez, R. (2012). Quality of student-faculty interaction at university: An empirical approach of gender and ICT usage. Socialinės technologijos, 2 (2), 249–262. Retrieved November 23, 2020, from https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/197244734.pdf

- De Jager JW, Gbadamosi G. Specific remedy for specific problem: Measuring service quality in South African higher education. Higher Education. 2010; 60 (3):251–267. doi: 10.1007/s10734-009-9298-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dill DD, Beerkens M. Designing the framework conditions for assuring academic standards: Lessons learned about professional, market, and government regulation of academic quality. Higher Education. 2013; 65 (3):341–357. doi: 10.1007/s10734-012-9548-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duque L. A framework for analysing higher education performance: Students’ satisfaction, perceived learning outcomes, and dropout intentions. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence. 2014; 25 (1–2):1–21. doi: 10.1080/14783363.2013.807677. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Duraku, Z. H., & Hoxha, L. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on higher education: A study of interaction among students' mental health, attitudes toward online learning, study skills, and changes in students' life. Retrieved September 18, 2020, from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/341599684_The_impact_of_COVID-19_on_higher_education_A_study_of_interaction_among_students'_mental_health_attitudes_toward_online_learning_study_skills_and_changes_in_students'_life

- Elliott KM, Healy MA. Key factors influencing student satisfaction related to recruitment and retention. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. 2001; 10 (4):1–11. doi: 10.1300/J050v10n04_01. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Elliott KM, Shin D. Student satisfaction: An alternative approach to assessing this important concept. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management. 2002; 24 (2):197–209. doi: 10.1080/1360080022000013518. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Feldman KA, Astin AW. What matters in college? Four critical years revisited [Review of What Matters in College? Four Critical Years Revisited, by A. W. Astin] The Journal of Higher Education. 1994; 65 (5):615–622. doi: 10.2307/2943781. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Guilbault M. Students as customers in higher education: Reframing the debate. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. 2016; 26 (2):132–142. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2016.1245234. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hanssen T, Solvoll G. The importance of university facilities for student satisfaction at a Norwegian University. Facilities. 2015; 33 (13/14):744–759. doi: 10.1108/F-11-2014-0081. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hassel H, Lourey J. The dea(r)th of student responsibility. College Teaching. 2005; 53 (1):2–13. doi: 10.3200/CTCH.53.1.2-13. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hou AYC, Ince M, Tsai S, Chiang CL. Quality assurance of quality assurance agencies from an Asian perspective: Regulation, autonomy and accountability. Asia Pacific Education Review. 2015; 16 (1):95–106. doi: 10.1007/s12564-015-9358-9. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hurst, B., Wallace, R., & Nixon, S. (2013). The impact of social interaction on student learning. Reading Horizons, 52 (4), 375–398. Retrieved October 11, 2020, from https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1022&context=articles-coe

- Jarvis D. Regulating higher education: Quality assurance and neo-liberal managerialism in higher education—A critical introduction. Policy and Society. 2014; 33 (3):155–166. doi: 10.1016/j.polsoc.2014.09.005. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Jereb E, Jerebic J, Urh M. Revising the importance of factors pertaining to student satisfaction in higher education. Organizacija. 2018; 51 (4):271–285. doi: 10.2478/orga-2018-0020. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Johnson ZS, Cascio R, Massiah CA. Explaining student interaction and satisfaction: An empirical investigation of delivery mode influence. Marketing Education Review. 2014; 24 (3):227–238. doi: 10.2753/MER1052-8008240304. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kakada, P., Deshpande, Y., & ShilpaBisen (2019). Technology support, social support, academic support, service support, and student satisfaction. J ournal of Information Technology Education, 18 , 549–70. Retrieved February 10, 2021, from http://www.jite.org/documents/Vol18/JITEv18ResearchP549-570Kakada5813.pdf

- Ke F, Kwak D. Online learning across ethnicity and age: A study on learning interaction participation, perception, and learning satisfaction. Computers and Education. 2013; 61 :43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.09.003. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kim Y, Sax L. Student–faculty interaction in research universities: Differences by student gender, race, social class, and first-generation status. Research in Higher Education. 2009; 50 (5):437–459. doi: 10.1007/s11162-009-9127-x. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kraemer BA. The academic and social integration of Hispanic students into college. The Review of Higher Education. 1997; 20 (2):163–179. doi: 10.1353/rhe.1996.0011. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuo Y-C, Walker AE, Schroder KE, Belland BR. Interaction, Internet self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning as predictors of student satisfaction in online education courses. The Internet and Higher Education. 2014; 20 :35–50. doi: 10.1016/j.iheduc.2013.10.001. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kurucay M, Inan FA. Examining the effects of learner-learner interactions on satisfaction and learning in an online undergraduate course. Computers & Education. 2017; 115 :20–37. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2017.06.010. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lapina I, Roga R, Müürsepp P. Quality of higher education: International students’ satisfaction and learning experience. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences. 2016; 8 (3):263–278. doi: 10.1108/IJQSS-04-2016-0029. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mamiseishvili K. Academic and social integration and persistence of international students at U.S. two-year institutions. Community College Journal of Research and Practice. 2011; 36 (1):15–27. doi: 10.1080/10668926.2012.619093. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Maslen, G. (2015, February 20). While branch campuses proliferate, many fail . University World News. Retrieved December 15, 2020, from http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20150219113033746

- McLeay F, Robson A, Yusoff M. New applications for importance-performance analysis (IPA) in higher education. Journal of Management Development. 2017; 36 (6):780–800. doi: 10.1108/JMD-10-2016-018. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Meeuwisse M, Severiens SE, Born MP. Learning environment, interaction, sense of belonging and study success in ethnically diverse student groups. Research in Higher Education. 2010; 51 (6):528–545. doi: 10.1007/s11162-010-9168-1. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Mihanović Z, Batinić A, Pavičić J. The link between students’ satisfaction with faculty, overall students’ satisfaction with student life and student performances. Review of Innovation and Competitiveness. 2016; 2 (1):37–60. doi: 10.32728/ric.2016.21/3. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Munley VG, Garvey E, McConnell MJ. The effectiveness of peer tutoring on student achievement at the university level. The American Economic Review. 2010; 100 (2):277–282. doi: 10.1257/aer.100.2.277. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Nastasić A, Banjević K, Gardašević D. Student satisfaction as a performance indicator of higher education institution. Mednarodno Inovativno Poslovanje. 2019; 11 (2):67–76. doi: 10.32015/JIBM/2019-11-2-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- OECD OECD at a glance: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, Paris. 2019 doi: 10.1787/f8d7880d-en. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Palmer A, Koenig-Lewis N. The effects of pre-enrolment emotions and peer group interaction on students’ satisfaction. Journal of Marketing Management. 2011; 27 (11–12):1208–1231. doi: 10.1080/0267257X.2011.614955. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pascarella ET. Student-faculty informal contact and college outcomes. Review of Educational Research. 1980; 50 (4):545–595. doi: 10.3102/00346543050004545. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Paul R, Pradhan S. Achieving student satisfaction and student loyalty in higher education: A focus on service value dimensions. Services Marketing Quarterly. 2019; 40 (3):245–268. doi: 10.1080/15332969.2019.1630177. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pritchard, A., & Woollard, J. (2013). Psychology for the classroom: Constructivism and social learning . Routledge. Retrieved February 19, 2021, from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.library.uwa.edu.au/lib/uwa/detail.action?docID=515360

- Rode JC, Arthaud-Day ML, Mooney CH, Near JP, Baldwin TT, Bommer WH, Rubin RS. Life satisfaction and student performance. Academy of Management Learning & Education. 2005; 4 (4):421–433. doi: 10.5465/AMLE.2005.19086784. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Santini F, Ladeira W, Sampaio C, da Silva Costa G. Student satisfaction in higher education: A meta-analytic study. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education. 2017; 27 (1):1–18. doi: 10.1080/08841241.2017.1311980. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Senior C, Howard C. Learning in friendship groups: Developing students’ conceptual understanding through social interaction. Frontiers in Psychology. 2014; 5 :1–8. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01031. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Senior C, Moores E, Burgess A. “I can’t get no satisfaction”: Measuring student satisfaction in the age of a consumerist higher education. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017; 8 :1–3. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00980. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shahzad, A., Hassan, R., Aremu, A., Hussain, A., & Lodhi, R. (2020 ). Effects of COVID-19 in E-learning on higher education institution students: The group comparison between male and female. Quality & Quantity, 1– 22. 10.1007/s11135-020-01028-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ]

- Sher, A. (2009). Assessing the relationship of student-instructor and student-student interaction to student learning and satisfaction in web-based online learning environment. Journal of Interactive Online Learning, 8 (2), 102–120. Retrieved October 17, 2020, from https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Assessing-the-Relationship-of-Student-Instructor-to-Sher/7810cfba73c549ffc94437375b9e6e8f84336af5

- Siming, L., Niamatullah, Gao, J., Xu, D., & Shafi, K. (2015). Factors leading to students’ Satisfaction in the higher learning institutions. Journal of Education and Practice 6 (31), 114–118. Retrieved March 6, 2021, from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1083362.pdf

- Sirgy M, Lee D, Grzeskowiak S, Yu G, Webb D, El-Hasan K, Jesus Garcia Vega J, Ekici A, Johar J, Krishen A, Kangal A, Swoboda B, Claiborne C, Maggino F, Rahtz D, Canton A, Kuruuzum A. Quality of College Life (QCL) of students: Further validation of a measure of well-being. Social Indicators Research. 2010; 99 (3):375–390. doi: 10.1007/s11205-010-9587-6. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tabachnick B, Fidell L. Using multivariate statistics. 6. Pearson Education; 2013. [ Google Scholar ]

- Tinto V. Dropout from higher education: A theoretical synthesis of recent research. Review of Educational Research. 1975; 45 (1):89–125. doi: 10.3102/00346543045001089. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- UNESCO International Institute for Higher Education in Latin America and the Caribbean (IESALC). (2020). COVID-19 and higher education: Today and tomorrow. Impact analysis, policy responses and recommendations . Retrieved February 24, 2021, from http://www.iesalc.unesco.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/COVID-19-EN-090420-2.pdf

- van Rooij E, Jansen E, van de Grift W. First-year university students’ academic success: The importance of academic adjustment. European Journal of Psychology of Education. 2018; 33 (4):749–767. doi: 10.1007/s10212-017-0347-8. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wach F, Karbach J, Ruffing S, Brünken R, Spinath F. University students’ satisfaction with their academic studies: Personality and motivation matter. Frontiers in Psychology. 2016; 7 (55):1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00055. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Weerasinghe, I.S., Fernando, S., & Lalitha, R. (2017). Students’ satisfaction in higher education. American Journal of Educational Research, 5 (5), 533 – 539. Retrieved September 2, 2020, from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2976013

- Weingarten, H., Hicks, M., & Kaufman, A. (2018). Assessing quality in postsecondary education: International perspectives . Kingston, Ontario, Canada: School of Policy Studies, Queen’s University. Retrieved October 19, 2020, from https://www-jstor-org.ezproxy.library.uwa.edu.au/stable/j.ctv8bt1

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Academic student satisfaction and perceived performance in the e-learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence across ten countries

Contributed equally to this work with: Damijana Keržič, Jogymol Kalariparampil Alex, Roxana Pamela Balbontín Alvarado, Denilson da Silva Bezerra, Maria Cheraghi, Beata Dobrowolska, Adeniyi Francis Fagbamigbe, MoezAlIslam Ezzat Faris, Thais França, Belinka González-Fernández, Luz Maria Gonzalez-Robledo, Fany Inasius, Sujita Kumar Kar, Kornélia Lazányi, Florin Lazăr, Juan Daniel Machin-Mastromatteo, João Marôco, Bertil Pires Marques, Oliva Mejía-Rodríguez, Silvia Mariela Méndez Prado, Alpana Mishra, Cristina Mollica, Silvana Guadalupe Navarro Jiménez, Alka Obadić, Daniela Raccanello, Md Mamun Ur Rashid, Dejan Ravšelj, Nina Tomaževič, Chinaza Uleanya, Lan Umek, Giada Vicentini, Özlem Yorulmaz, Ana-Maria Zamfir, Aleksander Aristovnik

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Faculty of Public Administration, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia, Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Roles Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Educational Sciences, Walter Sisulu University, Mthatha, South Africa

Roles Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Faculty of Education and Humanities, University of Bío Bío, Concepción, Chile

Affiliation Department of Oceanography and Limnology, Federal University of Maranhão, São Luís, Brazil

Roles Investigation

Affiliation Social Determinant of Health Research Center, Department of Public Health, School of Health, Ahvaz Jundishapur University of Medical Sciences, Ahvaz, Iran

Affiliation Faculty of Health Sciences, Medical University of Lublin, Lublin, Poland

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Epidemiology and Medical Statistics, Faculty of Public Health, College of Medicine, University of Ibadan, Ibadan, Nigeria

Roles Investigation, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Clinical Nutrition and Dietetics, College of Health Sciences, University of Sharjah, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates

Affiliation Centre for Research and Studies in Sociology, Cies-Iscte, Portugal

Affiliation Department of Sciences and Engineering, Universidad Iberoamericana Puebla/Red Citeg, Mexico City, Mexico

Affiliation Facultad de Medicina, Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, Morelos, Mexico

Affiliation Faculty of Economic and Communication, Bina Nusantara University, West Jakarta, Indonesia

Roles Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Psychiatry, King George’s Medical University, Lucknow, India

Affiliation John von Neumann Faculty of Informatics, Obuda University, Budapest, Hungary

Affiliation Faculty of Sociology and Social Work, University of Bucharest, Bucharest, Romania

Affiliation Faculty of Philosophy and Letters, Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua, Chihuahua, Mexico

Roles Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation William James Centre for Research, ISPA—Instituto Universitário, Lisbon, Portugal

Affiliation Higher Institute of Engineering of Porto, Polytechnic Institute of Porto, Porto, Portugal

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation División de Investigación Clínica, Centro de Investigación Biomédica de Michoacán, Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, Mexico, Mexico

Affiliation Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, ESPOL Polytechnic University, Guayaquil, Ecuador

Affiliation Faculty of Community Medicine, KIMS, Bhubaneswar, KIIT University, Bhubaneswar, India

Roles Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Statistical Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

Affiliation DTI-CUCEA & Instituto de Astronomía y Meteorología—CUCEI, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Mexico

Affiliation Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Zagreb, Zagreb, Croatia

Affiliation Department of Human Sciences, University of Verona, Verona, Italy

Affiliation Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, Patuakhali Science and Technology University, Barisal, Bangladesh

Roles Data curation

Affiliation Faculty of Public Administration, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia

Affiliation Business Management, University of South Africa (UNISA), Pretoria, South Africa

Roles Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliation Department of Econometrics, Faculty of Economics, University of Istanbul, Istanbul, Turkey

Affiliation National Scientific Research Institute for Labour and Social Protection, Bucharest, Romania

- [ ... ],

Roles Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

- [ view all ]

- [ view less ]

- Damijana Keržič,

- Jogymol Kalariparampil Alex,

- Roxana Pamela Balbontín Alvarado,

- Denilson da Silva Bezerra,

- Maria Cheraghi,

- Beata Dobrowolska,

- Adeniyi Francis Fagbamigbe,

- MoezAlIslam Ezzat Faris,

- Thais França,

- Published: October 20, 2021

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258807

- Reader Comments

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically shaped higher education and seen the distinct rise of e-learning as a compulsory element of the modern educational landscape. Accordingly, this study highlights the factors which have influenced how students perceive their academic performance during this emergency changeover to e-learning. The empirical analysis is performed on a sample of 10,092 higher education students from 10 countries across 4 continents during the pandemic’s first wave through an online survey. A structural equation model revealed the quality of e-learning was mainly derived from service quality, the teacher’s active role in the process of online education, and the overall system quality, while the students’ digital competencies and online interactions with their colleagues and teachers were considered to be slightly less important factors. The impact of e-learning quality on the students’ performance was strongly mediated by their satisfaction with e-learning. In general, the model gave quite consistent results across countries, gender, study fields, and levels of study. The findings provide a basis for policy recommendations to support decision-makers incorporate e-learning issues in the current and any new similar circumstances.

Citation: Keržič D, Alex JK, Pamela Balbontín Alvarado R, Bezerra DdS, Cheraghi M, Dobrowolska B, et al. (2021) Academic student satisfaction and perceived performance in the e-learning environment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence across ten countries. PLoS ONE 16(10): e0258807. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258807

Editor: Dejan Dragan, Univerza v Mariboru, SLOVENIA

Received: July 21, 2021; Accepted: October 5, 2021; Published: October 20, 2021

Copyright: © 2021 Keržič et al. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The data presented in this study are available in Supporting Information (see S1 Dataset ).

Funding: This research and the APC were funded by the Slovenian Research Agency grant number P5-0093. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

COVID-19, as a global public health crisis, has been brutal on the economy, education and food security of people all around the world, regardless of national boundaries. Affected sectors include tertiary education, featuring one of the worst disruptions during the lockdown periods given that most countries have tried to keep their essential economic activities running. Still, such activities did not extend to higher education institutions (HEIs), which were closed completely after the suspension of face-to-face activities in an effort to avoid the virus spreading among their students and staff and, in turn, the general population.

Nevertheless, HEIs have continued to offer education by using various digital media, e-learning platforms and video conferencing systems. The result is that e-learning has become a compulsory educational process. Many HEIs were even encountering this mode of delivery for the first time, making the transition particularly demanding for them since no time was available to organize and adapt to the new landscape for education. Both teachers and students today find themselves in a new environment, where some seem better at adapting than others. This means the quality of teaching and learning call for special consideration. In this article, the term “e-learning” refers to all forms of delivery for teaching and learning purposes that rely on different information communication technologies (ICTs) during the COVID-19 lockdown.

To understand COVID-19’s impact on the academic sphere, especially on students’ learning effectiveness, we explored the factors influencing how students have perceived their academic performance since HEIs cancelled their onsite classes. Students’ satisfaction in e-learning environments has been studied ever since the new mode of delivery via ICT first appeared (e.g. [ 1 ]), with researchers having tried to reveal factors that shape success with the implementation of e-learning systems (e.g. [ 2 – 4 ]), yet hitherto little attention has been paid to this topic in the current pandemic context. This study thus aims to fill this gap by investigating students’ e-learning experience in this emergency shift. Therefore, the questions we address in the paper are:

- R1: Which factors have contributed to students’ greater satisfaction with the e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic?

- R2: Are there any differences between factors influencing quality of the e-learning regarding countries, gender, and fields of study?

- R3: How does the students’ satisfaction with the transition to e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic relate to their academic performance?

According to previous research and considering the new circumstances (e.g. [ 5 – 7 ]), we propose a model for explaining students’ perceived academic performance. In order to identify relevant variables positively affecting students’ performance, we use data from the multi-country research study “Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Life of Higher Education Students”, coordinated by the Faculty of Public Administration, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia [ 8 ]. Structural equation modelling (SEM) is applied to explore the causal relationships among latent concepts, measured by several observed items. Since the SEM approach has a long history of successful applications in research, especially in the social sciences [ 9 , 10 ] and also in the educational context [ 11 ], it offers a suitable statistical framework that allows us to define a conceptual model containing interrelated variables connected to e-learning’s effect on students’ performance [ 9 , 10 ].

This study significantly contributes to understanding of students’ satisfaction and performance in the online environment. The research findings may be of interest to higher education planners, teachers, support services and students all around the world.

E-learning and the COVID-19 pandemic

According to the International Association of Universities (IAU), over 1.5 billion students and young people around the globe have been affected by the suspension of school and university classes due to the pandemic [ 12 ]. Thus, to maintain continuity in learning while working on containing the pandemic, countries have had to rely hugely on the e-learning modality, which may be defined as learning experiences with the assistance of online technologies. However, most HEIs were unprepared to effectively deal with the abrupt switch from on-site classes to on-line platforms, either due to infrastructure unavailability or the lack of suitable pedagogic projects [ 13 , 14 ]. To understand the mechanism and depth of the effects of COVID-19, many research studies have been carried out across the world.

Before COVID-19, as new technologies were developed, different e-learning modalities like blended learning and massive open online courses were gradually spreading around the world during the last few decades [ 15 , 16 ]. Hence, e-learning was deeply rooted in adequate planning and instructional design based on the available theories and models. It should be noted at the outset that what has been installed at many HEIs during the pandemic cannot even be considered e-learning, but emergency remote teaching, which is not necessarily as efficient and effective as a well-established and strategically organized system [ 17 ]. Still, all over the world online platforms, for example MS Teams, Moodle, Google Classroom, and Blackboard are in use. Although e-learning offers some educational continuity when it comes to academic learning, technical education has suffered doubly since the social distancing requirements have disrupted the implementation of both practical and work-based learning activities, which are critical for educational success [ 18 ].

According to Puljak et al. [ 19 ], while students have mostly been satisfied with how they have adapted to e-learning, they have missed the lectures and personal communication with their teachers. They declared that e-learning could not replace regular learning experiences; only 18.9% of students were interested in e-learning exclusively in the long run. Inadequate readiness among teachers and students to abruptly switch from face-to-face teaching to a digital platform has been reported [ 20 ].

The closure of universities and schools due to the COVID-19 pandemic has led to several adverse consequences for students, such as interrupted learning, giving students fewer opportunities to grow and develop [ 21 ]. This shift has resulted in various psychological changes among both students and teachers [ 22 ] and greatly affected their performance. Tutoring system in higher education is an established model of support, advice, and guidance for students in higher education with a purpose to improve motivation and success and prevent drop-out. Pérez-Jorge et al. [ 23 ] studied the effectiveness of the university tutoring system during the Covid-19 pandemic. The relation between tutor and student is based on collaboration and communication, which required to adopting quickly to the new situations using different communication technology. The research focused on four different forms of tutoring: in person, by e-mail, using virtual tutoring (Hangout/Google Meet) and WhatsApp. They pointed out that synchronous models and frequent daily communication are essential for effective and successful tutoring system where application WhatsApp, with synchronous communication by messages and video calls, is the form with which students were most satisfied and gain the most from it.

The goal of shifting teaching and learning over to online platforms is to minimize in-person interactions to reduce the risk of acquiring COVID-19 through physical contact. The form of interaction has also moved from offline mode to online mode. Students interact with each other in online platforms for their close group and also for larger groups [ 24 , 25 ]. Many clinical skills are learned through direct interactions with patients and caregivers, one area that has been badly affected by the switch to e-learning platforms [ 26 – 28 ].

Student satisfaction with e-learning

Student satisfaction has been shown to be a reliable proxy for measuring the success of implementing ICT-based initiatives in e-learning environments. Scholars have documented a strong relationship between how students perceive their academic performance and how satisfied students are with their e-learning environments [ 1 , 29 – 31 ].