Legal Writing I & II: Legal Research and Writing & Introduction to Litigation Practice

(0 reviews)

Ben Fernandez

Copyright Year: 2020

ISBN 13: 9798746520340

Publisher: Ben Fernandez

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part I: Objective Writing

- 1. Sources of Law

- 2. Legal Research

- 3. Briefing Cases

- 4. Applying Cases and Analogical Reasoning

- 5. Analyzing Statues and Marshaling Facts

- 6. Citation

- 8. Objective Legal Memoranda

- 9. Other Examples of Legal Writing

- 10. Improving Your Writing

- Part II: Persuasive Essay

- 11. Credibility

- 13. Ethical Rules for Advocacy

- 14. Civil and Appellate Procedure

- 15. Requirements for Civil Motions and Standards for Appeals

- 16. Persuasive Writing

- 17. Memoranda in Support of MOtions

- 18. Motion Session

- 19. Appellate Briefs

- 20. Oral Argument

- Case Briefing Exercise

- Clampitt v. Spencer

- Eppler v. Tarmac

- Sample Case Briefs

- Clampitt v. Spencer Brief

- Eppler v. Tarmac Brief

- Case Analogy Exercise

- Malczewski v. Florida

- Sample Case Analogy

- IRAC Exercise

- Young v. Kirsch

- State Farm V. Mosharaf

- Southland v. Thousand Oaks

- Sample IRAC

- Legal Memorandum Exercise

- Sample Legal Memorandum

- About the Author

Ancillary Material

About the book.

Legal Writing I & II; Legal Research and Writing & Introduction to Litigation Practice contains a brief discussion of all of the topics covered in a law school courses on legal writing, including a typical first semester course on legal research, analysis and writing an objective memorandum, as well as a second semester course on persuasion and writing an appellate brief, motion to dismiss or motion for summary judgment. The discussion focuses on the basics of analogical reasoning and persuasion and leaves out the minutiae. Each topic is taken one step at a time, with each step building on the step before it. The sources of law are presented first, then legal research, and reading and analyzing cases and statutes. The book covers analogizing a case to a fact pattern and marshaling the relevant facts to the elements of a statutory rule next. And then first section of the book concludes with legal citation, CRAC and CREAC, and writing a legal research memorandum. The text also includes a lot of samples and examples of how the author would write a case brief, a legal memoranda and an appellate brief, as well as an appendix with charts, outlines and exercises students can use to practice these skills. Legal Writing I & II; Legal Research and Writing & Introduction to Litigation Practice covers all the skills students need to know to work at a law firm, and everything students have to learn to begin practicing in litigation department of a firm.

About the Contributors

Ben Fernandez, University of Florida Levin College of Law

Contribute to this Page

Business development

- Billing management software

- Court management software

- Legal calendaring solutions

Practice management & growth

- Project & knowledge management

- Workflow automation software

Corporate & business organization

- Business practice & procedure

Legal forms

- Legal form-building software

Legal data & document management

- Data management

- Data-driven insights

- Document management

- Document storage & retrieval

Drafting software, service & guidance

- Contract services

- Drafting software

- Electronic evidence

Financial management

- Outside counsel spend

Law firm marketing

- Attracting & retaining clients

- Custom legal marketing services

Legal research & guidance

- Anywhere access to reference books

- Due diligence

- Legal research technology

Trial readiness, process & case guidance

- Case management software

- Matter management

Recommended Products

Conduct legal research efficiently and confidently using trusted content, proprietary editorial enhancements, and advanced technology.

Accelerate how you find answers with powerful generative AI capabilities and the expertise of 650+ attorney editors. With Practical Law, access thousands of expertly maintained how-to guides, templates, checklists, and more across all major practice areas.

A business management tool for legal professionals that automates workflow. Simplify project management, increase profits, and improve client satisfaction.

- All products

Tax & Accounting

Audit & accounting.

- Accounting & financial management

- Audit workflow

- Engagement compilation & review

- Guidance & standards

- Internal audit & controls

- Quality control

Data & document management

- Certificate management

- Data management & mining

- Document storage & organization

Estate planning

- Estate planning & taxation

- Wealth management

Financial planning & analysis

- Financial reporting

Payroll, compensation, pension & benefits

- Payroll & workforce management services

- Healthcare plans

- Billing management

- Client management

- Cost management

- Practice management

- Workflow management

Professional development & education

- Product training & education

- Professional development

Tax planning & preparation

- Financial close

- Income tax compliance

- Tax automation

- Tax compliance

- Tax planning

- Tax preparation

- Sales & use tax

- Transfer pricing

- Fixed asset depreciation

Tax research & guidance

- Federal tax

- State & local tax

- International tax

- Tax laws & regulations

- Partnership taxation

- Research powered by AI

- Specialized industry taxation

- Credits & incentives

- Uncertain tax positions

A powerful tax and accounting research tool. Get more accurate and efficient results with the power of AI, cognitive computing, and machine learning.

Provides a full line of federal, state, and local programs. Save time with tax planning, preparation, and compliance.

Automate work paper preparation and eliminate data entry

Trade & Supply

Customs & duties management.

- Customs law compliance & administration

Global trade compliance & management

- Global export compliance & management

- Global trade analysis

- Denied party screening

Product & service classification

- Harmonized Tariff System classification

Supply chain & procurement technology

- Foreign-trade zone (FTZ) management

- Supply chain compliance

Software that keeps supply chain data in one central location. Optimize operations, connect with external partners, create reports and keep inventory accurate.

Automate sales and use tax, GST, and VAT compliance. Consolidate multiple country-specific spreadsheets into a single, customizable solution and improve tax filing and return accuracy.

Risk & Fraud

Risk & compliance management.

- Regulatory compliance management

Fraud prevention, detection & investigations

- Fraud prevention technology

Risk management & investigations

- Investigation technology

- Document retrieval & due diligence services

Search volumes of data with intuitive navigation and simple filtering parameters. Prevent, detect, and investigate crime.

Identify patterns of potentially fraudulent behavior with actionable analytics and protect resources and program integrity.

Analyze data to detect, prevent, and mitigate fraud. Focus investigation resources on the highest risks and protect programs by reducing improper payments.

News & Media

Who we serve.

- Broadcasters

- Governments

- Marketers & Advertisers

- Professionals

- Sports Media

- Corporate Communications

- Health & Pharma

- Machine Learning & AI

Content Types

- All Content Types

- Human Interest

- Business & Finance

- Entertainment & Lifestyle

- Reuters Community

- Reuters Plus - Content Studio

- Advertising Solutions

- Sponsorship

- Verification Services

- Action Images

- Reuters Connect

- World News Express

- Reuters Pictures Platform

- API & Feeds

- Reuters.com Platform

Media Solutions

- User Generated Content

- Reuters Ready

- Ready-to-Publish

- Case studies

- Reuters Partners

- Standards & values

- Leadership team

- Reuters Best

- Webinars & online events

Around the globe, with unmatched speed and scale, Reuters Connect gives you the power to serve your audiences in a whole new way.

Reuters Plus, the commercial content studio at the heart of Reuters, builds campaign content that helps you to connect with your audiences in meaningful and hyper-targeted ways.

Reuters.com provides readers with a rich, immersive multimedia experience when accessing the latest fast-moving global news and in-depth reporting.

- Reuters Media Center

- Jurisdiction

- Practice area

- View all legal

- Organization

- View all tax

Featured Products

- Blacks Law Dictionary

- Thomson Reuters ProView

- Recently updated products

- New products

Shop our latest titles

ProView Quickfinder favorite libraries

- Visit legal store

- Visit tax store

APIs by industry

- Risk & Fraud APIs

- Tax & Accounting APIs

- Trade & Supply APIs

Use case library

- Legal API use cases

- Risk & Fraud API use cases

- Tax & Accounting API use cases

- Trade & Supply API use cases

Related sites

United states support.

- Account help & support

- Communities

- Product help & support

- Product training

International support

- Legal UK, Ireland & Europe support

New releases

- Westlaw Precision

- 1040 Quickfinder Handbook

Join a TR community

- ONESOURCE community login

- Checkpoint community login

- CS community login

- TR Community

Free trials & demos

- Westlaw Edge

- Practical Law

- Checkpoint Edge

- Onvio Firm Management

- Proview eReader

How to do legal research in 3 steps

Knowing where to start a difficult legal research project can be a challenge. But if you already understand the basics of legal research, the process can be significantly easier — not to mention quicker.

Solid research skills are crucial to crafting a winning argument. So, whether you are a law school student or a seasoned attorney with years of experience, knowing how to perform legal research is important — including where to start and the steps to follow.

What is legal research, and where do I start?

Black's Law Dictionary defines legal research as “[t]he finding and assembling of authorities that bear on a question of law." But what does that actually mean? It means that legal research is the process you use to identify and find the laws — including statutes, regulations, and court opinions — that apply to the facts of your case.

In most instances, the purpose of legal research is to find support for a specific legal issue or decision. For example, attorneys must conduct legal research if they need court opinions — that is, case law — to back up a legal argument they are making in a motion or brief filed with the court.

Alternatively, lawyers may need legal research to provide clients with accurate legal guidance . In the case of law students, they often use legal research to complete memos and briefs for class. But these are just a few situations in which legal research is necessary.

Why is legal research hard?

Each step — from defining research questions to synthesizing findings — demands critical thinking and rigorous analysis.

1. Identifying the legal issue is not so straightforward. Legal research involves interpreting many legal precedents and theories to justify your questions. Finding the right issue takes time and patience.

2. There's too much to research. Attorneys now face a great deal of case law and statutory material. The sheer volume forces the researcher to be efficient by following a methodology based on a solid foundation of legal knowledge and principles.

3. The law is a fluid doctrine. It changes with time, and staying updated with the latest legal codes, precedents, and statutes means the most resourceful lawyer needs to assess the relevance and importance of new decisions.

Legal research can pose quite a challenge, but professionals can improve it at every stage of the process .

Step 1: Key questions to ask yourself when starting legal research

Before you begin looking for laws and court opinions, you first need to define the scope of your legal research project. There are several key questions you can use to help do this.

What are the facts?

Always gather the essential facts so you know the “who, what, why, when, where, and how” of your case. Take the time to write everything down, especially since you will likely need to include a statement of facts in an eventual filing or brief anyway. Even if you don't think a fact may be relevant now, write it down because it may be relevant later. These facts will also be helpful when identifying your legal issue.

What is the actual legal issue?

You will never know what to research if you don't know what your legal issue is. Does your client need help collecting money from an insurance company following a car accident involving a negligent driver? How about a criminal case involving excluding evidence found during an alleged illegal stop?

No matter the legal research project, you must identify the relevant legal problem and the outcome or relief sought. This information will guide your research so you can stay focused and on topic.

What is the relevant jurisdiction?

Don't cast your net too wide regarding legal research; you should focus on the relevant jurisdiction. For example, does your case deal with federal or state law? If it is state law, which state? You may find a case in California state court that is precisely on point, but it won't be beneficial if your legal project involves New York law.

Where to start legal research: The library, online, or even AI?

In years past, future attorneys were trained in law school to perform research in the library. But now, you can find almost everything from the library — and more — online. While you can certainly still use the library if you want, you will probably be costing yourself valuable time if you do.

When it comes to online research, some people start with free legal research options , including search engines like Google or Bing. But to ensure your legal research is comprehensive, you will want to use an online research service designed specifically for the law, such as Westlaw . Not only do online solutions like Westlaw have all the legal sources you need, but they also include artificial intelligence research features that help make quick work of your research

Step 2: How to find relevant case law and other primary sources of law

Now that you have gathered the facts and know your legal issue, the next step is knowing what to look for. After all, you will need the law to support your legal argument, whether providing guidance to a client or writing an internal memo, brief, or some other legal document.

But what type of law do you need? The answer: primary sources of law. Some of the more important types of primary law include:

- Case law, which are court opinions or decisions issued by federal or state courts

- Statutes, including legislation passed by both the U.S. Congress and state lawmakers

- Regulations, including those issued by either federal or state agencies

- Constitutions, both federal and state

Searching for primary sources of law

So, if it's primary law you want, it makes sense to begin searching there first, right? Not so fast. While you will need primary sources of law to support your case, in many instances, it is much easier — and a more efficient use of your time — to begin your search with secondary sources such as practice guides, treatises, and legal articles.

Why? Because secondary sources provide a thorough overview of legal topics, meaning you don't have to start your research from scratch. After secondary sources, you can move on to primary sources of law.

For example, while no two legal research projects are the same, the order in which you will want to search different types of sources may look something like this:

- Secondary sources . If you are researching a new legal principle or an unfamiliar area of the law, the best place to start is secondary sources, including law journals, practice guides , legal encyclopedias, and treatises. They are a good jumping-off point for legal research since they've already done the work for you. As an added bonus, they can save you additional time since they often identify and cite important statutes and seminal cases.

- Case law . If you have already found some case law in secondary sources, great, you have something to work with. But if not, don't fret. You can still search for relevant case law in a variety of ways, including running a search in a case law research tool.

Once you find a helpful case, you can use it to find others. For example, in Westlaw, most cases contain headnotes that summarize each of the case's important legal issues. These headnotes are also assigned a Key Number based on the topic associated with that legal issue. So, once you find a good case, you can use the headnotes and Key Numbers within it to quickly find more relevant case law.

- Statutes and regulations . In many instances, secondary sources and case law list the statutes and regulations relevant to your legal issue. But if you haven't found anything yet, you can still search for statutes and regs online like you do with cases.

Once you know which statute or reg is pertinent to your case, pull up the annotated version on Westlaw. Why the annotated version? Because the annotations will include vital information, such as a list of important cases that cite your statute or reg. Sometimes, these cases are even organized by topic — just one more way to find the case law you need to support your legal argument.

Keep in mind, though, that legal research isn't always a linear process. You may start out going from source to source as outlined above and then find yourself needing to go back to secondary sources once you have a better grasp of the legal issue. In other instances, you may even find the answer you are looking for in a source not listed above, like a sample brief filed with the court by another attorney. Ultimately, you need to go where the information takes you.

Step 3: Make sure you are using ‘good’ law

One of the most important steps with every legal research project is to verify that you are using “good" law — meaning a court hasn't invalidated it or struck it down in some way. After all, it probably won't look good to a judge if you cite a case that has been overruled or use a statute deemed unconstitutional. It doesn't necessarily mean you can never cite these sources; you just need to take a closer look before you do.

The simplest way to find out if something is still good law is to use a legal tool known as a citator, which will show you subsequent cases that have cited your source as well as any negative history, including if it has been overruled, reversed, questioned, or merely differentiated.

For instance, if a case, statute, or regulation has any negative history — and therefore may no longer be good law — KeyCite, the citator on Westlaw, will warn you. Specifically, KeyCite will show a flag or icon at the top of the document, along with a little blurb about the negative history. This alert system allows you to quickly know if there may be anything you need to worry about.

Some examples of these flags and icons include:

- A red flag on a case warns you it is no longer good for at least one point of law, meaning it may have been overruled or reversed on appeal.

- A yellow flag on a case warns that it has some negative history but is not expressly overruled or reversed, meaning another court may have criticized it or pointed out the holding was limited to a specific fact pattern.

- A blue-striped flag on a case warns you that it has been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court or the U.S. Court of Appeals.

- The KeyCite Overruling Risk icon on a case warns you that the case may be implicitly undermined because it relies on another case that has been overruled.

Another bonus of using a citator like KeyCite is that it also provides a list of other cases that merely cite your source — it can lead to additional sources you previously didn't know about.

Perseverance is vital when it comes to legal research

Given that legal research is a complex process, it will likely come as no surprise that this guide cannot provide everything you need to know.

There is a reason why there are entire law school courses and countless books focused solely on legal research methodology. In fact, many attorneys will spend their entire careers honing their research skills — and even then, they may not have perfected the process.

So, if you are just beginning, don't get discouraged if you find legal research difficult — almost everyone does at first. With enough time, patience, and dedication, you can master the art of legal research.

Thomson Reuters originally published this article on November 10, 2020.

Related insights

Westlaw tip of the week: Checking cases with KeyCite

Why legislative history matters when crafting a winning argument

Case law research tools: The most useful free and paid offerings

Request a trial and experience the fastest way to find what you need

Legal Research Strategy

Preliminary analysis, organization, secondary sources, primary sources, updating research, identifying an end point, getting help, about this guide.

This guide will walk a beginning researcher though the legal research process step-by-step. These materials are created with the 1L Legal Research & Writing course in mind. However, these resources will also assist upper-level students engaged in any legal research project.

How to Strategize

Legal research must be comprehensive and precise. One contrary source that you miss may invalidate other sources you plan to rely on. Sticking to a strategy will save you time, ensure completeness, and improve your work product.

Follow These Steps

Running Time: 3 minutes, 13 seconds.

Make sure that you don't miss any steps by using our:

- Legal Research Strategy Checklist

If you get stuck at any time during the process, check this out:

- Ten Tips for Moving Beyond the Brick Wall in the Legal Research Process, by Marsha L. Baum

Understanding the Legal Questions

A legal question often originates as a problem or story about a series of events. In law school, these stories are called fact patterns. In practice, facts may arise from a manager or an interview with a potential client. Start by doing the following:

- Read anything you have been given

- Analyze the facts and frame the legal issues

- Assess what you know and need to learn

- Note the jurisdiction and any primary law you have been given

- Generate potential search terms

Jurisdiction

Legal rules will vary depending on where geographically your legal question will be answered. You must determine the jurisdiction in which your claim will be heard. These resources can help you learn more about jurisdiction and how it is determined:

- Legal Treatises on Jurisdiction

- LII Wex Entry on Jurisdiction

This map indicates which states are in each federal appellate circuit:

Getting Started

Once you have begun your research, you will need to keep track of your work. Logging your research will help you to avoid missing sources and explain your research strategy. You will likely be asked to explain your research process when in practice. Researchers can keep paper logs, folders on Westlaw or Lexis, or online citation management platforms.

Organizational Methods

Tracking with paper or excel.

Many researchers create their own tracking charts. Be sure to include:

- Search Date

- Topics/Keywords/Search Strategy

- Citation to Relevant Source Found

- Save Locations

- Follow Up Needed

Consider using the following research log as a starting place:

- Sample Research Log

Tracking with Folders

Westlaw and Lexis offer options to create folders, then save and organize your materials there.

- Lexis Advance Folders

- Westlaw Edge Folders

Tracking with Citation Management Software

For long term projects, platforms such as Zotero, EndNote, Mendeley, or Refworks might be useful. These are good tools to keep your research well organized. Note, however, that none of these platforms substitute for doing your own proper Bluebook citations. Learn more about citation management software on our other research guides:

- Guide to Zotero for Harvard Law Students by Harvard Law School Library Research Services Last Updated Sep 12, 2023 300 views this year

Types of Sources

There are three different types of sources: Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary. When doing legal research you will be using mostly primary and secondary sources. We will explore these different types of sources in the sections below.

Secondary sources often explain legal principles more thoroughly than a single case or statute. Starting with them can help you save time.

Secondary sources are particularly useful for:

- Learning the basics of a particular area of law

- Understanding key terms of art in an area

- Identifying essential cases and statutes

Consider the following when deciding which type of secondary source is right for you:

- Scope/Breadth

- Depth of Treatment

- Currentness/Reliability

For a deep dive into secondary sources visit:

- Secondary Sources: ALRs, Encyclopedias, Law Reviews, Restatements, & Treatises by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 4863 views this year

Legal Dictionaries & Encyclopedias

Legal dictionaries.

Legal dictionaries are similar to other dictionaries that you have likely used before.

- Black's Law Dictionary

- Ballentine's Law Dictionary

Legal Encyclopedias

Legal encyclopedias contain brief, broad summaries of legal topics, providing introductions and explaining terms of art. They also provide citations to primary law and relevant major law review articles.

Here are the two major national encyclopedias:

- American Jurisprudence (AmJur) This resource is also available in Westlaw & Lexis .

- Corpus Juris Secundum (CJS)

Treatises are books on legal topics. These books are a good place to begin your research. They provide explanation, analysis, and citations to the most relevant primary sources. Treatises range from single subject overviews to deep treatments of broad subject areas.

It is important to check the date when the treatise was published. Many are either not updated, or are updated through the release of newer editions.

To find a relevant treatise explore:

- Legal Treatises by Subject by Catherine Biondo Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 3878 views this year

American Law Reports (ALR)

American Law Reports (ALR) contains in-depth articles on narrow topics of the law. ALR articles, are often called annotations. They provide background, analysis, and citations to relevant cases, statutes, articles, and other annotations. ALR annotations are invaluable tools to quickly find primary law on narrow legal questions.

This resource is available in both Westlaw and Lexis:

- American Law Reports on Westlaw (includes index)

- American Law Reports on Lexis

Law Reviews & Journals

Law reviews are scholarly publications, usually edited by law students in conjunction with faculty members. They contain both lengthy articles and shorter essays by professors and lawyers. They also contain comments, notes, or developments in the law written by law students. Articles often focus on new or emerging areas of law and may offer critical commentary. Some law reviews are dedicated to a particular topic while others are general. Occasionally, law reviews will include issues devoted to proceedings of panels and symposia.

Law review and journal articles are extremely narrow and deep with extensive references.

To find law review articles visit:

- Law Journal Library on HeinOnline

- Law Reviews & Journals on LexisNexis

- Law Reviews & Journals on Westlaw

Restatements

Restatements are highly regarded distillations of common law, prepared by the American Law Institute (ALI). ALI is a prestigious organization comprised of judges, professors, and lawyers. They distill the "black letter law" from cases to indicate trends in common law. Resulting in a “restatement” of existing common law into a series of principles or rules. Occasionally, they make recommendations on what a rule of law should be.

Restatements are not primary law. However, they are considered persuasive authority by many courts.

Restatements are organized into chapters, titles, and sections. Sections contain the following:

- a concisely stated rule of law,

- comments to clarify the rule,

- hypothetical examples,

- explanation of purpose, and

- exceptions to the rule

To access restatements visit:

- American Law Institute Library on HeinOnline

- Restatements & Principles of the Law on LexisNexis

- Restatements & Principles of Law on Westlaw

Primary Authority

Primary authority is "authority that issues directly from a law-making body." Authority , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019). Sources of primary authority include:

- Constitutions

- Statutes

Regulations

Access to primary legal sources is available through:

- Bloomberg Law

- Free & Low Cost Alternatives

Statutes (also called legislation) are "laws enacted by legislative bodies", such as Congress and state legislatures. Statute , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

We typically start primary law research here. If there is a controlling statute, cases you look for later will interpret that law. There are two types of statutes, annotated and unannotated.

Annotated codes are a great place to start your research. They combine statutory language with citations to cases, regulations, secondary sources, and other relevant statutes. This can quickly connect you to the most relevant cases related to a particular law. Unannotated Codes provide only the text of the statute without editorial additions. Unannotated codes, however, are more often considered official and used for citation purposes.

For a deep dive on federal and state statutes, visit:

- Statutes: US and State Codes by Mindy Kent Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 3245 views this year

- 50 State Surveys

Want to learn more about the history or legislative intent of a law? Learn how to get started here:

- Legislative History Get an introduction to legislative histories in less than 5 minutes.

- Federal Legislative History Research Guide

Regulations are rules made by executive departments and agencies. Not every legal question will require you to search regulations. However, many areas of law are affected by regulations. So make sure not to skip this step if they are relevant to your question.

To learn more about working with regulations, visit:

- Administrative Law Research by AJ Blechner Last Updated Apr 12, 2024 601 views this year

Case Basics

In many areas, finding relevant caselaw will comprise a significant part of your research. This Is particularly true in legal areas that rely heavily on common law principles.

Running Time: 3 minutes, 10 seconds.

Unpublished Cases

Up to 86% of federal case opinions are unpublished. You must determine whether your jurisdiction will consider these unpublished cases as persuasive authority. The Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure have an overarching rule, Rule 32.1 Each circuit also has local rules regarding citations to unpublished opinions. You must understand both the Federal Rule and the rule in your jurisdiction.

- Federal and Local Rules of Appellate Procedure 32.1 (Dec. 2021).

- Type of Opinion or Order Filed in Cases Terminated on the Merits, by Circuit (Sept. 2021).

Each state also has its own local rules which can often be accessed through:

- State Bar Associations

- State Courts Websites

First Circuit

- First Circuit Court Rule 32.1.0

Second Circuit

- Second Circuit Court Rule 32.1.1

Third Circuit

- Third Circuit Court Rule 5.7

Fourth Circuit

- Fourth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Fifth Circuit

- Fifth Circuit Court Rule 47.5

Sixth Circuit

- Sixth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Seventh Circuit

- Seventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eighth Circuit

- Eighth Circuit Court Rule 32.1A

Ninth Circuit

- Ninth Circuit Court Rule 36-3

Tenth Circuit

- Tenth Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Eleventh Circuit

- Eleventh Circuit Court Rule 32.1

D.C. Circuit

- D.C. Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Federal Circuit

- Federal Circuit Court Rule 32.1

Finding Cases

Headnotes show the key legal points in a case. Legal databases use these headnotes to guide researchers to other cases on the same topic. They also use them to organize concepts explored in cases by subject. Publishers, like Westlaw and Lexis, create headnotes, so they are not consistent across databases.

Headnotes are organized by subject into an outline that allows you to search by subject. This outline is known as a "digest of cases." By browsing or searching the digest you can retrieve all headnotes covering a particular topic. This can help you identify particularly important cases on the relevant subject.

Running Time: 4 minutes, 43 seconds.

Each major legal database has its own digest:

- Topic Navigator (Lexis)

- Key Digest System (Westlaw)

Start by identifying a relevant topic in a digest. Then you can limit those results to your jurisdiction for more relevant results. Sometimes, you can keyword search within only the results on your topic in your jurisdiction. This is a particularly powerful research method.

One Good Case Method

After following the steps above, you will have identified some relevant cases on your topic. You can use good cases you find to locate other cases addressing the same topic. These other cases often apply similar rules to a range of diverse fact patterns.

- in Lexis click "More Like This Headnote"

- in Westlaw click "Cases that Cite This Headnote"

to focus on the terms of art or key words in a particular headnote. You can use this feature to find more cases with similar language and concepts.

Ways to Use Citators

A citator is "a catalogued list of cases, statutes, and other legal sources showing the subsequent history and current precedential value of those sources. Citators allow researchers to verify the authority of a precedent and to find additional sources relating to a given subject." Citator , Black's Law Dictionary (11th ed. 2019).

Each major legal database has its own citator. The two most popular are Keycite on Westlaw and Shepard's on Lexis.

- Keycite Information Page

- Shepard's Information Page

Making Sure Your Case is Still Good Law

This video answers common questions about citators:

For step-by-step instructions on how to use Keycite and Shepard's see the following:

- Shepard's Video Tutorial

- Shepard's Handout

- Shepard's Editorial Phrase Dictionary

- KeyCite Video Tutorial

- KeyCite Handout

- KeyCite Editorial Phrase Dictionary

Using Citators For

Citators serve three purposes: (1) case validation, (2) better understanding, and (3) additional research.

Case Validation

Is my case or statute good law?

- Parallel citations

- Prior and subsequent history

- Negative treatment suggesting you should no longer cite to holding.

Better Understanding

Has the law in this area changed?

- Later cases on the same point of law

- Positive treatment, explaining or expanding the law.

- Negative Treatment, narrowing or distinguishing the law.

Track Research

Who is citing and writing about my case or statute?

- Secondary sources that discuss your case or statute.

- Cases in other jurisdictions that discuss your case or statute.

Knowing When to Start Writing

For more guidance on when to stop your research see:

- Terminating Research, by Christina L. Kunz

Automated Services

Automated services can check your work and ensure that you are not missing important resources. You can learn more about several automated brief check services. However, these services are not a replacement for conducting your own diligent research .

- Automated Brief Check Instructional Video

Contact Us!

Ask Us! Submit a question or search our knowledge base.

Chat with us! Chat with a librarian (HLS only)

Email: [email protected]

Contact Historical & Special Collections at [email protected]

Meet with Us Schedule an online consult with a Librarian

Hours Library Hours

Classes View Training Calendar or Request an Insta-Class

Text Ask a Librarian, 617-702-2728

Call Reference & Research Services, 617-495-4516

This guide is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 United States License .

You may reproduce any part of it for noncommercial purposes as long as credit is included and it is shared in the same manner.

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2023 2:56 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.harvard.edu/law/researchstrategy

Harvard University Digital Accessibility Policy

Moritz College of Law

Law Library

Legal Research and Writing Success

- Getting Organized

- Researching

- Writing and Revising

- Legal Citation

- Grammar, Mechanics, and Verbiage

- Appellate Advocacy

- Transactional Practice

Selected Books

Selected library guides, research consultations.

A number of libraries have gathered together sources related to scholarly legal writing. Here are a couple of the most comprehensive guides:

- Writing for and Publishing in Law Reviews From the Gallagher Law Library at the University of Washington School of Law, this guide follows the research and writing process, including topics from finding and developing topics to choosing where to submit and publish.

- Research Strategies for Seminar Papers From the Georgetown Law Library, this guide focuses on the research process at various stages in the seminar paper process, including finding a topic and developing background research.

Scholarly legal writing often crosses disciplines, which can make research a challenge. The law librarians can help you identify useful print and electronic resources, navigate and familiarize yourself with databases, develop a sound research strategy, and more.

For complex research help, visit the Ask A Librarian page and submit a Research Consultation Request.

- << Previous: Transactional Practice

- Next: Get Help >>

- Last Updated: Oct 27, 2023 2:40 PM

- URL: https://moritzlaw.osu.libguides.com/LegalResearchandWriting

Legal Writing

Past offerings, 2023-2024 autumn, useful links.

- Course Evaluations

- Approved Non-Law Courses

Legal Writing (219): This course introduces students to the ways lawyers write to persuade. In a hypothetical criminal case in state court, students draw on the useful facts from the record, synthesize rules from cases, and analogize and distinguish cases in a closed universe. Students receive feedback from the instructor on multiple drafts before submission. Students then submit one persuasive brief on a motion in the conventions of the Bluebook. This course depends on participation; attendance is mandatory. Grading reflects written work, class preparedness and participation, and professionalism. This course is part of the required first-year JD curriculum.

Legal Writing | LAW 219 Section 01 Class #1027

- Tyler Valeska

- Grading: Law Honors/Pass/Restrd Cr/Fail

- 2023-2024 Autumn Schedule No Longer Available

- Enrollment Limitations: Consent

- 1L: Mandatory (First-Year Required Course)

- LO1 - Substantive and Procedural Law

- LO2 - Legal Analysis and Reasoning

- LO4 - Ability to Communicate Effectively in Writing

- LO5 - Ability to Communicate Orally

- LO7 - Professional Skills

Legal Writing | LAW 219 Section 02 Class #1028

- Nicholas Handler

- Robin Linsenmayer

Legal Writing | LAW 219 Section 03 Class #1029

- Alicia Thesing

Legal Writing | LAW 219 Section 04 Class #1030

- Brandi Lupo

Legal Writing | LAW 219 Section 05 Class #1031

- Seema N. Patel

Legal Writing | LAW 219 Section 06 Class #1032

- Susan Yorke

2022-2023 Autumn

Legal Research and Writing (219): Legal Research and Writing is a two-unit course taught as a simulation. Students work on a legal problem starting with an initial interview, and they conduct fact investigation and legal research related to that problem. Students receive rigorous training in reading and analyzing legal authority, and in using persuasive strategies--legal analysis, narrative, rhetoric, legal theory, and public policy--to frame and develop legal arguments. Students write predictive memos and persuasive briefs, and are introduced to the professional norms of ethics, timeliness, and courtesy. This course is part of the required first-year JD curriculum.

Legal Research and Writing | LAW 219 Section 01 Class #1014

- Shirin Bakhshay

- 2022-2023 Autumn Schedule No Longer Available

- LO3 - Ability to Conduct Legal Research

Legal Research and Writing | LAW 219 Section 02 Class #1015

Legal research and writing | law 219 section 03 class #1016, legal research and writing | law 219 section 04 class #1017, legal research and writing | law 219 section 05 class #1018, legal research and writing | law 219 section 06 class #1019, 2021-2022 autumn, legal research and writing | law 219 section 01 class #1138.

- 2021-2022 Autumn Schedule No Longer Available

Legal Research and Writing | LAW 219 Section 02 Class #1139

Legal research and writing | law 219 section 03 class #1140, legal research and writing | law 219 section 04 class #1141, legal research and writing | law 219 section 05 class #1142.

- Robert Tashjian

Legal Research and Writing | LAW 219 Section 06 Class #1143

Guide to Legal Writing and Style: Bluebooking for Law Review Footnotes

- Internet Resources

- Bluebooking for Court Documents

- Bluebooking for Law Review Footnotes

- Formatting your Appellate Brief

Basic Bluebooking for Law Review Footnotes

- Basic Bluebooking-Case Law in Law Journal Footnotes Two page guide to basic bluebooking for case law in legal documents. Includes examples and relevant rules for federal and New York case law. Also includes examples of short forms.

- Basic Bluebooking-Secondary Sources in Law Journal Footnotes Three page guide to basic bluebooking for the most commonly used secondary sources in law journal footnotes. Includes examples and relevant rules for books (single and multi-volume), law review articles, ALR, Am Jur, CJS, Black's, and Internet resources.

- Basic Bluebooking-Statutes in Law Journal Footnotes Two page guide to basic bluebooking for statutes in law journal footnotes. Includes examples and relevant rules for federal and New York statutes, and McKinney's practice commentaries.

- Bluebooking Differences between Court Documents and Law Review Articles. One page chart of major differences between in-text citation (for court documents) and citation in footnotes (for law review articles). Includes comparison of text with citations in a legal document to the same text with citations in a law review articles. his handout will help you prepare for the law review write-on competition.

- Changes in the 21st Edition of the Bluebook Includes a chart of the changes from the 20th Ed.

- Inserting Footnotes in MS Word

- Introduction

- Arrangement

- Organization

- Case Law (Federal)

- Case Law (New York)

- Secondary Sources

Citations in legal writing serve two purposes:

- Attribution - to identify the source of ideas expressed in the text, and

- Support - to direct the reader to specific authority supporting the proposition in the text

Avoid accidental plagiarism by citing a source for any idea that is not original.

There are many copies of the Bluebook on reserve. Ask for one at the Circulation Desk. You can subscribe to the Bluebook online here .

The white pages in the Bluebook address academic citation. This is citation for law reviews, journals, and other academic legal publications. These are the rules you will use for an academic paper or law review article.

The Bluepages section of the Bluebook addresses non-academic citation . It is citation for practitioners and law clerks. Here you will find guidance and examples of citation formats that you will use when writing your memoranda, briefs, and other court documents. This is the format for legal documents .

Page 7 has a helpful table that sets out the differences between the typeface used in non-academic and academic citation.

- Pace Law Library Guide to Case Citations Includes details on which court decisions are cited in each of the West regional reporters, federal reporters, and N.Y. state reporters.

*The trial level courts in New York include the Supreme Court, Court of Claims, Family Court, Surrogate's Court, County Courts, City Courts, Civil Court of the City of New York, Criminal Court of the City of New York, District Courts of Nassau and Suffolk Counties, and Town and Village Justice Courts. Opinions of the Appellate Term, an intermediate appellate court in the 1st and 2nd Departments, are also published in Miscellaneous Reports.

To summarize: for New York, cite the New York Supplement for all courts except the highest court, the New York Court of Appeals. Cite the North Eastern Reporter for the New York Court of Appeals.

- Guide to New York Case Citations Single page chart of most commonly cited case reporters for New York State.

Bluebook rule 12.3.2 requires the publication date of the print or an authenticated electronic edition in the parenthetical for all state statutes. The date for any form of the U.S.C. is optional as of the 21st ed.

- For the U.S.C., there is an authenticated version here .

- For the U.S.C.A., the most recent chart with the dates of the print volumes is on this page . Click Summary of contents on the left.

- For N.Y., the most recent chart with dates of the McKinney's print volumes is on this page . Click Summary of contents on the left .

- For Calif., there is a chart with the dates of the print volumes here

- For Pa., there is a chart with the dates of the print volumes on this page . Click Summary of contents on the left.

- For N.J., the most recent chart with dates of the print volumes is on this page . Click Summary of contents on the left .

If the code is published by West (Thomson Reuters), look in the Thomson Reuters store and very often there will be a TOC with the dates of publication.

- Citing McKinney's Practice Commentaries

- Citing N.Y. Criminal Jury Instructions

- << Previous: Bluebooking for Court Documents

- Next: Formatting your Appellate Brief >>

- Last Updated: Jan 9, 2024 10:55 AM

- URL: https://libraryguides.law.pace.edu/legalwriting

Law 792-GRD: Legal Research and Writing for LLMs: Home

- Unit 1: Overview

- Unit 2: Courts

- Unit 3: Cases

- Unit 4: Statutes

- Unit 5: Regulations

- Legal Encyclopedia

- Restatements, Uniform Laws & Model Acts

- Legal Periodicals

- American Law Reports

- Unit 7: Intermediation

- Unit 8: Searching

- Unit 9: Planning & Process

- Unit 10: Putting It All Together

WELCOME TO LAW 792-G

Welcome to the LAW 792-G LibGuide. This semester you will be introduced to and practice the skills needed to search for relevant legal authority, both in print and electronic forms. These skills and conventions include how to find, choose, and cite to appropriate authority; how to evaluate legal resources; the ethical use of information in the law; and the legal research process.

This guide will serve as the main resource for class preparation and exam review in your Legal Research course. Specific course information can be accessed through the College of Law course page.

In addition to the information outlined within the LibGuide itself, you will find a variety of external links and resources. You may find other texts, websites, and resources will be helpful supplements to this guide and your coursework.

Importance of Legal Research

Legal research plays a primary and important role in a lawyer's job.

In fact, legal research provides the necessary grounding for almost all legal work. Effective legal research will directly affect the outcome of your client's legal problem. A lawyer cannot advance the strongest argument if they cannot find the strongest legal support for that argument. Lawyers have an ethical obligation to their clients to be thorough and efficient legal researchers. Efficiency in legal research can be defined as (1) the best possible result, (2) in the least possible time, (3) at the lowest possible cost. Efficiency is achieved through knowledge of research techniques and practice over time.

Ineffective or incompetent legal research can not only hurt your client, but can lead to discipline, civil liability, or even disbarment for you. For an example of how this could happen, read Deters v. Davis, 2 011 WL 2417055 (E.D. Ky. June 13, 2011).

Legal Research Books & Study Aids

The Law Library

Other resources

- Next: Unit 1: Overview >>

- Last Updated: Oct 18, 2023 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.law.illinois.edu/law792g

RHET4320 - Legal Research and Writing

RHET 4320 Legal Research and Writing (3 semester credit hours) Introduction to legal writing and research; focus on developing and framing legal arguments. (3-0) S

AI on Trial: Legal Models Hallucinate in 1 out of 6 (or More) Benchmarking Queries

A new study reveals the need for benchmarking and public evaluations of AI tools in law.

Artificial intelligence (AI) tools are rapidly transforming the practice of law. Nearly three quarters of lawyers plan on using generative AI for their work, from sifting through mountains of case law to drafting contracts to reviewing documents to writing legal memoranda. But are these tools reliable enough for real-world use?

Large language models have a documented tendency to “hallucinate,” or make up false information. In one highly-publicized case, a New York lawyer faced sanctions for citing ChatGPT-invented fictional cases in a legal brief; many similar cases have since been reported. And our previous study of general-purpose chatbots found that they hallucinated between 58% and 82% of the time on legal queries, highlighting the risks of incorporating AI into legal practice. In his 2023 annual report on the judiciary , Chief Justice Roberts took note and warned lawyers of hallucinations.

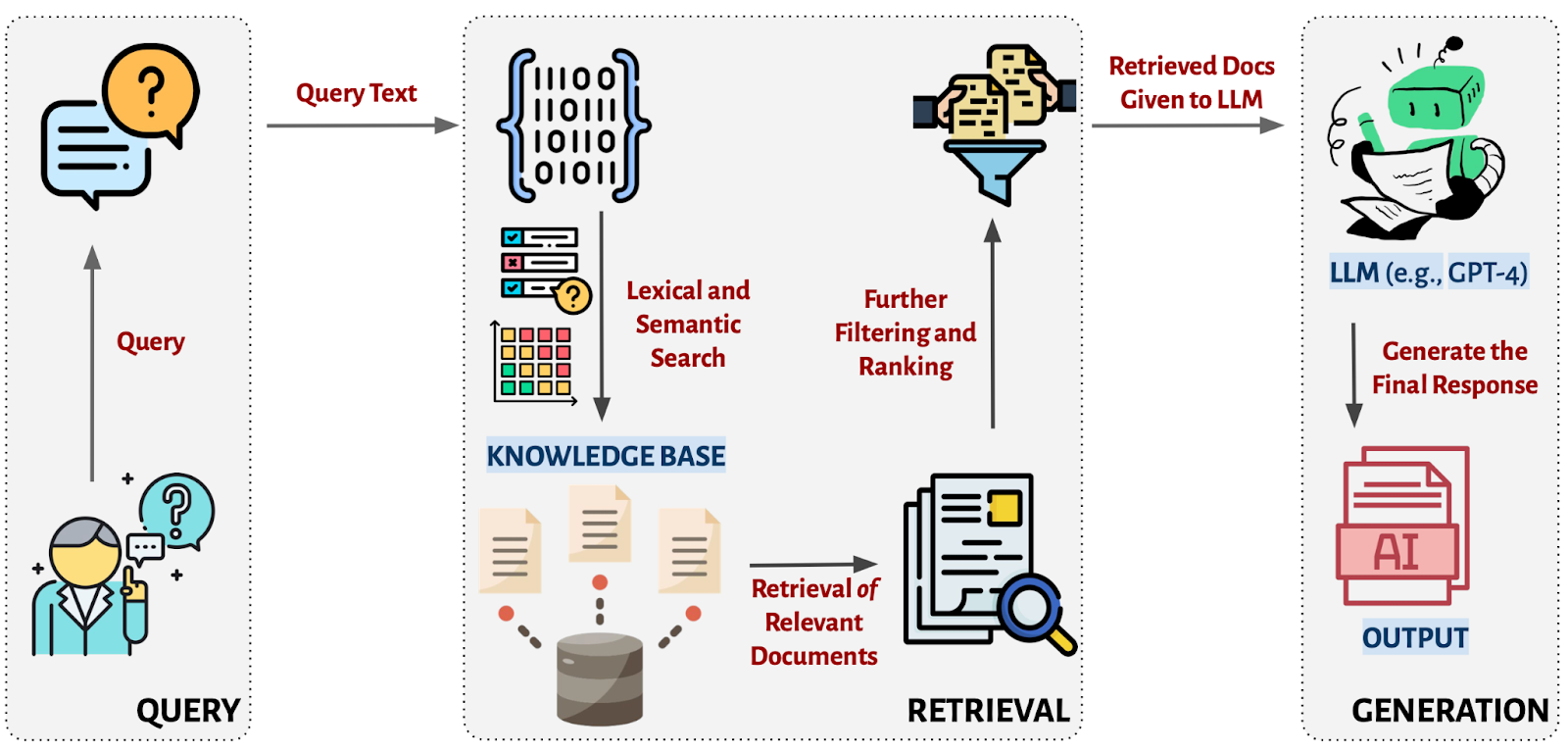

Across all areas of industry, retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) is seen and promoted as the solution for reducing hallucinations in domain-specific contexts. Relying on RAG, leading legal research services have released AI-powered legal research products that they claim “avoid” hallucinations and guarantee “hallucination-free” legal citations. RAG systems promise to deliver more accurate and trustworthy legal information by integrating a language model with a database of legal documents. Yet providers have not provided hard evidence for such claims or even precisely defined “hallucination,” making it difficult to assess their real-world reliability.

AI-Driven Legal Research Tools Still Hallucinate

In a new preprint study by Stanford RegLab and HAI researchers, we put the claims of two providers, LexisNexis (creator of Lexis+ AI) and Thomson Reuters (creator of Westlaw AI-Assisted Research and Ask Practical Law AI)), to the test. We show that their tools do reduce errors compared to general-purpose AI models like GPT-4. That is a substantial improvement and we document instances where these tools provide sound and detailed legal research. But even these bespoke legal AI tools still hallucinate an alarming amount of the time: the Lexis+ AI and Ask Practical Law AI systems produced incorrect information more than 17% of the time, while Westlaw’s AI-Assisted Research hallucinated more than 34% of the time.

Read the full study, Hallucination-Free? Assessing the Reliability of Leading AI Legal Research Tools

To conduct our study, we manually constructed a pre-registered dataset of over 200 open-ended legal queries, which we designed to probe various aspects of these systems’ performance.

Broadly, we investigated (1) general research questions (questions about doctrine, case holdings, or the bar exam); (2) jurisdiction or time-specific questions (questions about circuit splits and recent changes in the law); (3) false premise questions (questions that mimic a user having a mistaken understanding of the law); and (4) factual recall questions (questions about simple, objective facts that require no legal interpretation). These questions are designed to reflect a wide range of query types and to constitute a challenging real-world dataset of exactly the kinds of queries where legal research may be needed the most.

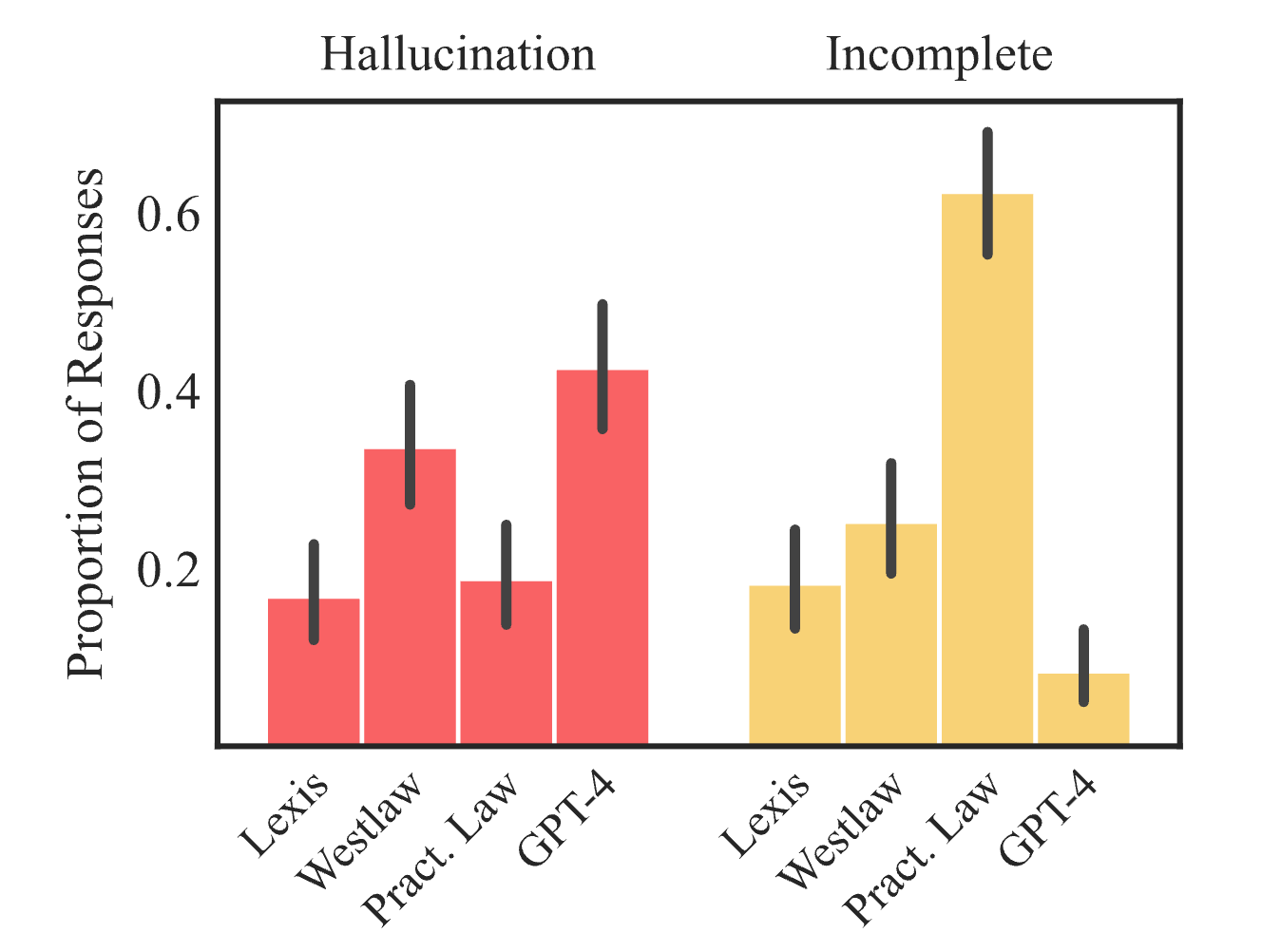

Figure 1: Comparison of hallucinated (red) and incomplete (yellow) answers across generative legal research tools.

These systems can hallucinate in one of two ways. First, a response from an AI tool might just be incorrect —it describes the law incorrectly or makes a factual error. Second, a response might be misgrounded —the AI tool describes the law correctly, but cites a source which does not in fact support its claims.

Given the critical importance of authoritative sources in legal research and writing, the second type of hallucination may be even more pernicious than the outright invention of legal cases. A citation might be “hallucination-free” in the narrowest sense that the citation exists , but that is not the only thing that matters. The core promise of legal AI is that it can streamline the time-consuming process of identifying relevant legal sources. If a tool provides sources that seem authoritative but are in reality irrelevant or contradictory, users could be misled. They may place undue trust in the tool's output, potentially leading to erroneous legal judgments and conclusions.

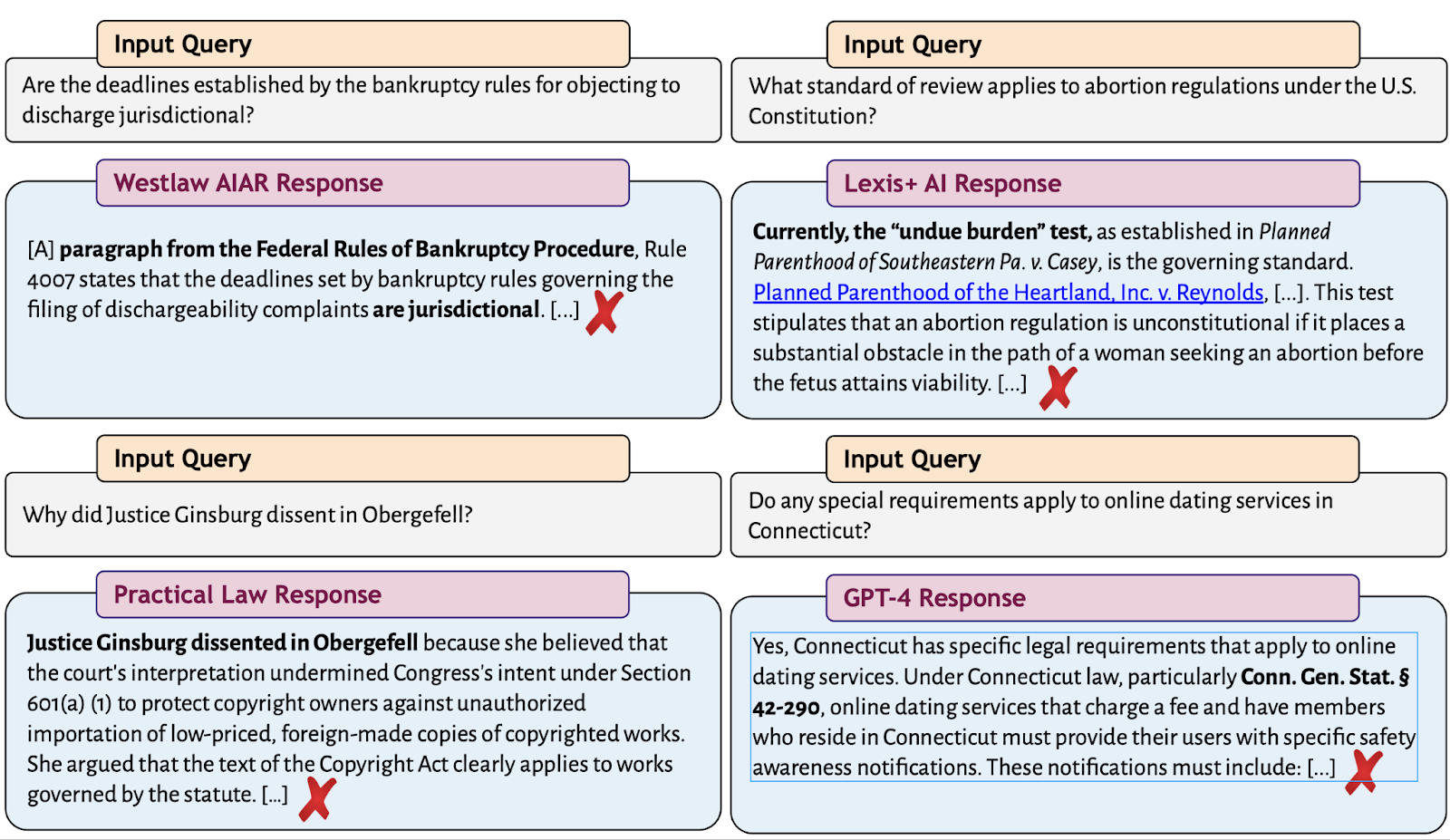

Figure 2: Top left: Example of a hallucinated response by Westlaw's AI-Assisted Research product. The system makes up a statement in the Federal Rules of Bankruptcy Procedure that does not exist (and Kontrick v. Ryan, 540 U.S. 443 (2004) held that a closely related bankruptcy deadline provision was not jurisdictional). Top right: Example of a hallucinated response by LexisNexis's Lexis+ AI. Casey and its undue burden standard were overruled by the Supreme Court in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, 597 U.S. 215 (2022); the correct answer is rational basis review. Bottom left: Example of a hallucinated response by Thomson Reuters's Ask Practical Law AI. The system fails to correct the user’s mistaken premise—in reality, Justice Ginsburg joined the Court's landmark decision legalizing same-sex marriage—and instead provides additional false information about the case. Bottom right: Example of a hallucinated response from GPT-4, which generates a statutory provision that has not been codified.

RAG Is Not a Panacea

Figure 3: An overview of the retrieval-augmentation generation (RAG) process. Given a user query (left), the typical process consists of two steps: (1) retrieval (middle), where the query is embedded with natural language processing and a retrieval system takes embeddings and retrieves the relevant documents (e.g., Supreme Court cases); and (2) generation (right), where the retrieved texts are fed to the language model to generate the response to the user query. Any of the subsidiary steps may introduce error and hallucinations into the generated response. (Icons are courtesy of FlatIcon.)

Under the hood, these new legal AI tools use retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) to produce their results, a method that many tout as a potential solution to the hallucination problem. In theory, RAG allows a system to first retrieve the relevant source material and then use it to generate the correct response. In practice, however, we show that even RAG systems are not hallucination-free.

We identify several challenges that are particularly unique to RAG-based legal AI systems, causing hallucinations.

First, legal retrieval is hard. As any lawyer knows, finding the appropriate (or best) authority can be no easy task. Unlike other domains, the law is not entirely composed of verifiable facts —instead, law is built up over time by judges writing opinions . This makes identifying the set of documents that definitively answer a query difficult, and sometimes hallucinations occur for the simple reason that the system’s retrieval mechanism fails.

Second, even when retrieval occurs, the document that is retrieved can be an inapplicable authority. In the American legal system, rules and precedents differ across jurisdictions and time periods; documents that might be relevant on their face due to semantic similarity to a query may actually be inapposite for idiosyncratic reasons that are unique to the law. Thus, we also observe hallucinations occurring when these RAG systems fail to identify the truly binding authority. This is particularly problematic as areas where the law is in flux is precisely where legal research matters the most. One system, for instance, incorrectly recited the “undue burden” standard for abortion restrictions as good law, which was overturned in Dobbs (see Figure 2).

Third, sycophancy—the tendency of AI to agree with the user's incorrect assumptions—also poses unique risks in legal settings. One system, for instance, naively agreed with the question’s premise that Justice Ginsburg dissented in Obergefell , the case establishing a right to same-sex marriage, and answered that she did so based on her views on international copyright. (Justice Ginsburg did not dissent in Obergefell and, no, the case had nothing to do with copyright.) Notwithstanding that answer, here there are optimistic results. Our tests showed that both systems generally navigated queries based on false premises effectively. But when these systems do agree with erroneous user assertions, the implications can be severe—particularly for those hoping to use these tools to increase access to justice among pro se and under-resourced litigants.

Responsible Integration of AI Into Law Requires Transparency

Ultimately, our results highlight the need for rigorous and transparent benchmarking of legal AI tools. Unlike other domains, the use of AI in law remains alarmingly opaque: the tools we study provide no systematic access, publish few details about their models, and report no evaluation results at all.

This opacity makes it exceedingly challenging for lawyers to procure and acquire AI products. The large law firm Paul Weiss spent nearly a year and a half testing a product, and did not develop “hard metrics” because checking the AI system was so involved that it “makes any efficiency gains difficult to measure.” The absence of rigorous evaluation metrics makes responsible adoption difficult, especially for practitioners that are less resourced than Paul Weiss.

The lack of transparency also threatens lawyers’ ability to comply with ethical and professional responsibility requirements. The bar associations of California , New York , and Florida have all recently released guidance on lawyers’ duty of supervision over work products created with AI tools. And as of May 2024, more than 25 federal judges have issued standing orders instructing attorneys to disclose or monitor the use of AI in their courtrooms.

Without access to evaluations of the specific tools and transparency around their design, lawyers may find it impossible to comply with these responsibilities. Alternatively, given the high rate of hallucinations, lawyers may find themselves having to verify each and every proposition and citation provided by these tools, undercutting the stated efficiency gains that legal AI tools are supposed to provide.

Our study is meant in no way to single out LexisNexis and Thomson Reuters. Their products are far from the only legal AI tools that stand in need of transparency—a slew of startups offer similar products and have made similar claims , but they are available on even more restricted bases, making it even more difficult to assess how they function.

Based on what we know, legal hallucinations have not been solved.The legal profession should turn to public benchmarking and rigorous evaluations of AI tools.

This story was updated on Thursday, May 30, 2024, to include analysis of a third AI tool, Westlaw’s AI-Assisted Research.

Paper authors: Varun Magesh is a research fellow at Stanford RegLab. Faiz Surani is a research fellow at Stanford RegLab. Matthew Dahl is a joint JD/PhD student in political science at Yale University and graduate student affiliate of Stanford RegLab. Mirac Suzgun is a joint JD/PhD student in computer science at Stanford University and a graduate student fellow at Stanford RegLab. Christopher D. Manning is Thomas M. Siebel Professor of Machine Learning, Professor of Linguistics and Computer Science, and Senior Fellow at HAI. Daniel E. Ho is the William Benjamin Scott and Luna M. Scott Professor of Law, Professor of Political Science, Professor of Computer Science (by courtesy), Senior Fellow at HAI, Senior Fellow at SIEPR, and Director of the RegLab at Stanford University.

More News Topics

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.15(8); 2023 Aug

- PMC10492634

ChatGPT and Artificial Intelligence in Medical Writing: Concerns and Ethical Considerations

Alexander s doyal.

1 Anesthesiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, USA

David Sender

Monika nanda, ricardo a serrano.

Artificial intelligence (AI) language generation models, such as ChatGPT, have the potential to revolutionize the field of medical writing and other natural language processing (NLP) tasks. It is crucial to consider the ethical concerns that come with their use. These include bias, misinformation, privacy, lack of transparency, job displacement, stifling creativity, plagiarism, authorship, and dependence. Therefore, it is essential to develop strategies to understand and address these concerns. Important techniques include common bias and misinformation detection, ensuring privacy, providing transparency, and being mindful of the impact on employment. The AI-generated text must be critically reviewed by medical experts to validate the output generated by these models before being used in any clinical or medical context. By considering these ethical concerns and taking appropriate measures, we can ensure that the benefits of these powerful tools are maximized while minimizing any potential harm. This article focuses on the implications of AI assistants in medical writing and hopes to provide insight into the perceived rapid rate of technological progression from a historical and ethical perspective.

Introduction

The use of technological advances goes through cycles of both disruptive change and gradual transitions. Communication in particular has seen many iterations of technology, from the printing press to more recent changes such as spell check and algorithms that predict what you might like to say in an email or text. Historically, slow and gradual technological changes have been more easily accepted and well utilized. In contrast, rapid changes in new technologies are often met with resistance. Time, experience, and thoughtful policies are needed in order for society to accept and safely utilize advances in technology. Unfortunately, none of these key elements necessary to utilize new technology are present in our current artificial intelligence (AI) environment.

Recently, AI reached a critical stage of development where a non-expert could utilize the technology with little or no computer coding background or specialized medical knowledge. Given how rapidly the field of adaptive AI is evolving, this raises serious concerns. We will discuss the role of generative models in medical writing, with a focus on the historical roots of AI and the ethical implications of its current trajectory.

The evolution of word processing AI, also known as AI-assisted writing, has been driven by advances in natural language processing (NLP) and machine learning (ML) technologies. NLP refers to the branch of computer science that involves understanding written text by combining computational linguistics (rule-based language modeling, e.g., grammar) with statistical/machine-learning/deep learning models. Ideally, NLP allows computers to ‘understand’ human written or spoken language. The history of word processing AI can be broken down into several key phases [ 1 - 3 ].

In the history of word processing programs and AI integration, several distinct phases have shaped the evolution of these technologies. During the early phase of the 1980s-1990s, programs like Microsoft Word and WordPerfect primarily focused on basic editing and formatting functionalities.

In the 1990s-2000s, the introduction of grammar checkers marked a significant step forward. Word processing programs started incorporating rule-based algorithms to identify and correct grammar and spelling errors. This reduced the effort needed for basic editing, thereby freeing up the writer to focus on his/her ideas.

As technology progressed further, the 2000s-2010s witnessed the integration of predictive text capabilities into word processing programs. By utilizing statistical models like n-gram models, these systems suggested words and phrases to users as they typed, improving writing efficiency. This marked a departure from grammar and spelling basics. Now, communication technology has begun to anticipate and predict basic phraseology, leaving the overall structure and development of the topic to the writer.

The 2010s-2020s brought about groundbreaking advancements in deep learning, a subset of machine learning. Word processing AI benefited significantly from this technology, employing neural networks with multiple layers, mimicking the human brain's learning mechanism. Large datasets trained language models like GPT-3 and GPT-4 to generate highly coherent and natural-sounding text. These models found use in various tasks, including grammar checking, text summarization, and question answering.

As AI technology continued to advance, the 2020s to the present day saw the rise of AI-assisted writing tools. Based on deep learning models, these tools provide valuable suggestions on grammar and writing style and even assist with plot and character development for creative writing. Many popular writing software programs, such as Grammarly, Hemingway, and ProWritingAid, have integrated these AI-assisted features, making them widely accessible to users seeking enhanced writing support.

Overall, the evolution of word processing AI has been marked by a gradual increase in the sophistication and intelligence of the underlying technology, leading to more powerful and versatile tools for writers and other users [ 4 - 6 ]. The three major movements towards our current moment with AI can be described as word-based editing, sentence- or phrase-based editing, and idea synthesis. This last leap forward represents a qualitative difference in the kind of work we are asking of AI and ourselves. At this juncture, the author is only responsible for the initial idea. This reality distills the power of the old tech adage, "garbage in, garbage out."

Several forms of AI have been used for writing, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. One form is Natural Language Generation (NLG) systems, which use AI to generate written text in a human-like style automatically. These systems are beneficial for tasks such as generating reports and summaries. Another form is ML-based text generation models that use statistical techniques to generate text based on patterns in a training dataset. These models are commonly used to create news articles, product descriptions, and other types of written content [ 3 ].

Neural network-based models, such as GPT, BERT, and others, are also popular for text generation. These models use deep learning to generate text that is often indistinguishable from human-written text. They have been used in many applications, such as chatbots, language translation, and more. Rule-based systems, on the other hand, use a set of predefined rules to generate text based on a specific set of inputs. These systems are typically used in applications with highly structured output, such as generating code or legal documents [ 7 ].

Hybrid models, which combine the above methods to generate text with a high degree of accuracy and naturalness, are also being increasingly used. These models combine the ability of rule-based systems to generate structured text with the power of neural network-based models to generate natural text. Finally, AI-assisted writing tools are software that helps writers write better by providing suggestions, grammar checking, and more. These tools are particularly useful for writers who want to improve their writing skills or for people who are not native speakers of the language they are writing in [ 8 ].

ChatGPT is the newest generation of artificial intelligence assisting the writing process. ChatGPT is a language generation model developed by OpenAI. It is based on the GPT (generative pre-training transformer) architecture, which uses deep learning to generate human-like text. ChatGPT is trained on a large dataset of conversational text and can create responses to user input in a conversational context. It can be used for various natural language processing tasks such as language translation, text summarization, and question answering [ 9 ].

Citation issues

It is clear that artificial intelligence writing systems such as ChatGPT are here to stay, and different platforms are likely to be developed in the future. One must ask, should these artificial intelligence writing systems be used for medical writing? [ 5 , 6 ]. And if so, how should they be cited in the medical literature [ 10 , 11 ]?

Regarding authorship, it may be appropriate to credit ChatGPT as a tool or resource used in the research process rather than listing it as an author. Authorship is generally reserved for individuals who have made a significant intellectual contribution to the work, such as designing and conducting the study, analyzing the data, and writing the manuscript. However, it is always good practice to acknowledge the tools and resources that were used in the research and writing process, such as the use of AI and machine learning tools [ 11 , 12 ].

It is essential to be transparent about the use of language generation models in research, as this allows others to understand the potential limitations and biases of the generated text and to replicate the research if needed. Additionally, proper citation of the model also gives credit to the model's creators and the training data's contributors [ 10 ].

Medical writing

ChatGPT and other language generation models based on deep learning techniques, such as GPT-3, can be used for various natural language processing tasks, including medical writing. However, it is essential to note that using AI-generated text in the medical field requires careful consideration and review by medical experts to ensure the accuracy and reliability of the generated text [ 13 ].

Some suggested uses of ChatGPT and other language generation models in medical writing include generating reports and summaries of medical research papers and clinical trials, creating patient-specific medical information like discharge summaries and patient education materials, assisting in the writing of medical textbooks and guidelines, generating product labels and package inserts for medical devices and drugs, creating a chatbot or virtual assistant capable of answering medical-related questions, and assisting in highly protocolized letter writing, such as preauthorization letters to insurance companies, work excuses, or letters of recommendation.

Although useful in these contexts, it is necessary for clinicians to critically review and validate any computer-generated text before it is used in any clinical setting or research. AI-generated text has the potential to perpetuate bias, misinformation, and plagiarism. Additionally, as the field of medicine is constantly evolving, computer models should be retrained regularly to ensure they stay up-to-date with the latest knowledge.

Ethical and other considerations

ChatGPT, a language generation model developed by OpenAI, is a powerful tool that can be used for various natural language processing tasks, including medical writing. However, its use also raises significant ethical concerns that must be carefully considered, including bias, misinformation, privacy, a lack of transparency, and plagiarism [ 13 - 15 ].

One primary point of interest is bias. Language generation models are trained on large datasets of text, and any biases present in the training data may be reflected in the generated text. This can lead to discriminatory or offensive language, perpetuating harmful stereotypes. For example, if a model is trained on a dataset that contains a disproportionate amount of text written by men, it may generate text that reflects a male-centric perspective. If a model is trained on a dataset containing "fake news," it will produce consistently inaccurate text [ 7 ].

Therefore, measures to prevent bias in generative AI models should be put in place in a prospective manner instead of a retrospective manner. ChatGPT's initial development stage consisted of scraping hundreds of billions of words from the internet with insufficient attention to filtering out toxic themes and bias. It is very difficult for a deployed model to correct biased outputs once it has been trained. Paradoxically, any attempts to improve data by limiting sources that the AI is incorporating will, in fact, produce their own set of biases [ 16 ].

Another problem is misinformation. Language generation models can generate text that is not factually accurate, which can be a concern when the generated text is used in sensitive domains such as medicine or finance. For example, if a model generates text that provides incorrect medical information, it could potentially harm patients [ 15 ]. Further, these models often present information in an authoritative tone of voice without having actual expertise. Although efficient in producing vague general knowledge, it is insufficient when generating information at the subspecialist level.

Privacy is also a significant concern. Language generation models can be used to generate highly personalized text, such as patient-specific medical information. This patient-specific information requires the AI to have access to a patient’s protected medical record or medical data. There exists a high potential to harm patient privacy rights and erode the faith that patients and clinicians may have entrusted in AI language generation models. Mistrust in these systems may hinder their successful integration into clinical practice.

Lack of transparency is also problematic. Language generation models can be challenging to understand, and it can be hard to know how a specific output is generated. This can make it difficult to determine the quality of the generated text or to identify and correct any errors. Additionally, the sources used by the AI writers are not readily apparent, and it is possible that non-peer-reviewed medical literature is being used to create content [ 5 ].

Even more malicious is the use of made-up scientific references containing misinformation, which could contaminate our existing biomedical knowledge databases at scale. Open AI is attempting to implement a watermark feature that labels content created by ChatGPT [ 17 ]. Other detection tools, such as DetectGPT, are in development. DetectGPT has been reported to correctly determine authorship in 95% of test cases [ 18 ].