- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance articles

- Themed Collections

- Editor's Choice

- Ilona Kickbusch Award

- Supplements

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Online

- Open Access Option

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Promotion International

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

- < Previous

Associations between gender equality and health: a systematic review

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Tania L King, Anne Kavanagh, Anna J Scovelle, Allison Milner, Associations between gender equality and health: a systematic review, Health Promotion International , Volume 35, Issue 1, February 2020, Pages 27–41, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day093

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This systematic review sought to evaluate the impact of gender equality on the health of both women and men in high-income countries. A range of health outcomes arose across the 48 studies included. Gender equality was measured in various ways, including employment characteristics, political representation, access to services, and with standard indicators (such as the Global Gender Gap Index and the Gender Empowerment Measure). The effects of gender equality varied depending on the health outcome examined, and the context in which gender equality was examined (i.e. employment or domestic domain). Overall, evidence suggests that greater gender equality has a mostly positive effect on the health of males and females. We found utility in the convergence model, which postulates that gender equality will be associated with a convergence in the health outcomes of men and women, but unless there is encouragement and support for men to assume more non-traditional roles, further health gains will be stymied.

Email alerts

Citing articles via.

- Recommend to Your Librarian

- Journals Career Network

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1460-2245

- Print ISSN 0957-4824

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

The Gender Equality Paradox in STEM fields: Evidence, criticism, and implications

Margit Osterloh Roles: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Project Administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Katja Rost Roles: Conceptualization, Funding Acquisition, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing – Review & Editing Louisa Hizli Roles: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing Annina Mösching Roles: Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft Preparation, Writing – Review & Editing

This article is included in the Gender Stereotypes in the 21st Century collection.

The gender gap in the fields of STEM (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and computer science) in richer and more egalitarian countries compared to poorer and less egalitarian countries is called “Gender Equality Paradox” (GEP). We provide an overview of the evidence for the GEP and respond to criticism against the GEP. We explain the GEP by the higher identity costs of women in wealthier countries due to an increase in the gender stereotype gap and at the same time a lower marginal utility of wealth. We discuss why the GEP in rich countries in the future might enlarge the gender pay gap in spite of more gender equality.

gender stereotypes, women in STEM, gender pay gap, career aspirations, preferences, identity costs, power imbalance

Introduction

The lack of representation of women in STEM subjects (science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and computer science) is a worldwide phenomenon. Remarkably, within wealthy countries like Switzerland and Sweden which at the same time are characterized by high levels of formal gender equality, the proportion of female STEM graduates is lower than in countries like Algeria or Morocco. For example, female STEM graduates in Switzerland make up 22 percent, in Germany 28 percent, in Sweden 36 percent, while in Morocco there are 45 percent, and in Algeria 58 percent of female STEM graduates ( Hizli et al ., 2022 ). 1 The gender gap in STEM fields in richer and more egalitarian fields compared to poorer and less egalitarian countries is called “Gender Equality Paradox” (GEP). It contradicts the common assumption that as countries become wealthier and more gender equal 2 , the preferences between women and men become more equal.

In our paper, we first provide an overview of the evidence for the GEP. Second, we respond to criticism against the GEP. Third, we try to explain why the share of women in STEM is lower in richer than in poorer countries. Fourth, we discuss why the GEP might matter. We argue that the GEP in wealthy countries might increase the gender pay gap and possibly contribute to a greater power imbalance in partnerships in spite of more formal gender equality. The aim of our paper is to contribute to the understanding of the GEP in order to find out which policy implications are to be considered.

Empirical evidence for the Gender Equality Paradox

In recent years, the GEP has been the subject of extensive research. In this section we discuss the most interesting findings of this research. It shows that the existence and relevance of the GEP today is no longer questioned, but that the explanations for this phenomenon are unsatisfying.

Stoet & Geary (2018) are among the most cited authors studying this phenomenon. They find a negative cross-country correlation between what they term the "propensity of women to graduate with STEM degrees" and formal gender equality. The authors call this the “educational-gender-equality paradox”. Stoet & Geary (2018) used the 2015 PISA database , an every-three-year international assessment of half a million 15-year-old students in mathematics, reading, and science in 37 mostly developed countries and 39 developing countries, which calculated each student´s highest subject, second highest and lowest performing subject. The results on achievements in science, mathematics, and reading show that girls perform better in reading than boys, but at the same time perform similarly or even better than boys in STEM fields across most countries. However, women obtain fewer college degrees in STEM disciplines than men. Paradoxically, the loss of females graduating in STEM fields is higher in gender-equal countries. The study suggests two explanations for this finding. The first explanation is rational decision-making concerning the relative strength of women and men: According to expectancy-value-theory ( Eccles, 1983 ; Wang & Degol, 2013 ) to decide about their educational choices, students use their knowledge of what subjects they perform best and enjoy most. The second explanation concerns economic opportunities and risks: in countries with more gender equality, girls and women can afford to engage in subjects according to their individual interests. In contrast, in environments with fewer economic opportunities and higher economic risks, girls and women tend to choose high-paying STEM occupations. Yet, Stoet & Geary (2018) do not explain, why in more gender-equal environments the differences in competencies and interests of boys and girls amplify.

A more recent study by Stoet & Geary (2022) investigates sex differences in adolescents’ career aspirations across 80 countries using the 2018 PISA database . The study shows that boys are more likely to aspire to things-orientated or STEM careers, while girls tend to aspire to people-oriented occupations, leading to stereotypical male and female careers. In countries with higher levels of women's empowerment, these sex differences are more pronounced, e.g., in Finland or Sweden compared to Morocco or Saudi Arabia. The authors show that these correlations are mostly due to an increase in boys´ aspirations for things-oriented skilled blue-collar careers, and a decrease in their aspirations for people-oriented careers. Stoet & Geary (2022) interpret this result from economic backgrounds: an increase in women's empowerment leads to a higher national wealth, allowing students to pursue careers based on their interests rather than on economic security. The authors suggest that a higher national wealth also enhances working conditions for things-oriented skilled blue-collar jobs, which are often better paid than people-oriented occupations. Stoet & Geary (2022) refer to this interpretation as the “Counter Intuitive Gender Empowerment Model” (CIGEM). They suggest that biological factors contribute to the strong differences in career aspirations in countries with high women´s empowerment. However, it remains unclear why higher economic security affects the interests of boys and girls differently. Overall, the GIGEM model leads the two authors to scepticism about policy interventions to reduce stereotypical careers. In their view, if anything, information about STEM can be provided at an early age, though there is no guarantee that such interventions would be effective. It would make more sense to encourage girls to pursue careers that are neither things- nor people-oriented, for example, careers in management.

The study of Thelwall and Mas-Bleda (2020) extends the GEP to academic research publishing. The study unravels the gender disparities among researchers in STEM by comparing the first-author gender in 30 million articles from various academic fields across 31 countries. In countries where there is a higher proportion of female first-authored research, disparities in gender across different academic fields are larger. These gender disparities are analysed and categorized as subject-wide or nation-specific. The results show that the proportion of female first authors varies to a large extent between the countries as well as the fields. Greater diversity between fields in the proportion of female first-authored research is found in countries and fields with more female researchers, suggesting that in these countries there is more leeway for cultural and biological sex differences in preferences. In order to enlarge the percentage of female researchers in STEM the authors suggest increasing gender differentiation in a more gender-equal academic environment.

Vishkin (2022) considers the GEP in chess participation with a total number of 803,485 active players (15.7% females) originating from 160 countries born between 1920 and 2017. He shows that today, women of younger age cohorts in countries with lower gender equality tend to participate in chess more frequently than women of older age cohorts. The study suggests a generational shift, with younger players participating more in countries with less gender equality. Additionally, a curvilinear effect is found, indicating that gender differences in chess participation are most pronounced at both the highest and lowest ends of the gender equality spectrum.

Napp and Breda (2022) analyse how gender stereotypes concerning brilliance, talent, competitiveness, and self-confidence vary across countries and across students with different abilities using the PISA 2018 database. They measure the strength of gender talent stereotypes among a group of students by the average difference in the attribution of failure to lack of talent, comparing equally able boys and girls within this group. The authors show that stereotypes linking talent and brilliance to men are more pronounced in more developed and gender-egalitarian countries. They also observe similar patterns for competitiveness, self-confidence, and willingness to pursue information and communications technology (ICT)-related occupations. Moreover, the stereotypes associating talent primarily with men are larger among higher-ability students. The more women are present in education, labour force and politics, the stronger is this gender talent stereotype. The authors explain their findings by deeply rooted essential gender norms. According to Napp & Breda (2022) those norms are strengthened in wealthy and egalitarian countries by more individualistic values that give more importance to self-realization and self-expression. However, why this should be the case remains unclear.

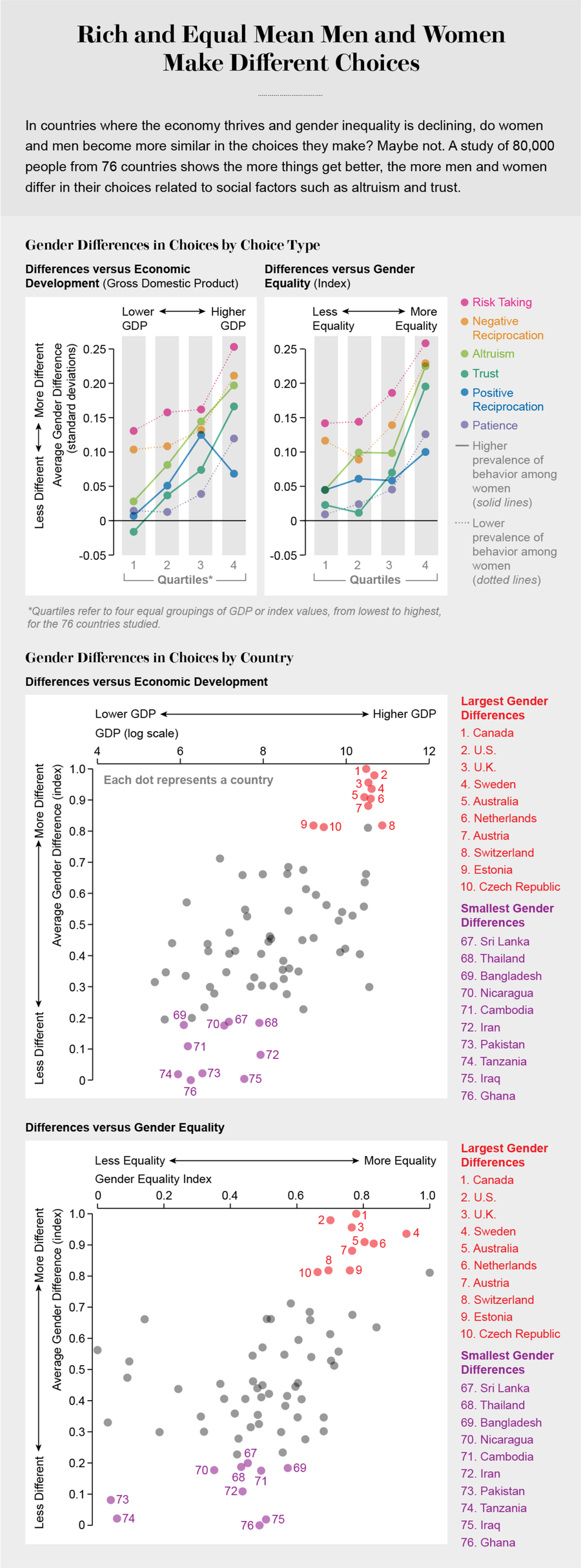

Falk and Hermle (2018) establish a positive cross-country correlation between six fundamental preferences and economic development and gender equality. 3 These values comprise altruism, trust, risk-taking, patience, positive and negative reciprocity. The authors find a strong correlation between GDP per capita and the gender equality index. Both—economic development and gender equality—are associated with higher gender differences in fundamental preferences. The study uses data from the Global Preference Survey across 76 countries. The survey was validated by incentivized choice experiments and controlled for potential confounding factors. The authors explain their findings with better material and social resources available in wealthy countries. These resources eliminate the gender-neutral goal of subsistence and create scope for gender-specific ambitions and desires for self-expression. Again, it is unclear why gender-specific ambitions increase with wealth.

Objections to the Gender Equality Paradox

The findings on the Gender Equality Paradox have met some objections. Richardson et al. (2020) challenge the robustness of the Gender Equality Paradox, showing that it is sensitive to measurement methods. Stoet and Geary (2018) find a negative cross-country correlation between the “propensity of women to graduate with STEM degrees” and formal gender equality. However, Richardson et al. (2020) demonstrate that the correlation between gender equality, as identified by Stoet and Geary (2018) , and women in STEM shows small effect sizes and becomes insignificant when alternative measures of gender equality and of women in STEM are considered. In addition to this methodological criticism, two points have to be taken into account.

First, STEM is a broad designation, including biology, mathematics, physics, or mechanical engineering. The share of women within these fields varies strongly. Based on a study with global data more than 60% of students in biology are female, while the share of women in electrical or mechanical engineering is less than 20% ( Federkeil & Friedhoff, 2022 ). To address this issue, some papers have introduced more narrow definition of scientific fields of study: For instance, Ceci et al. ( 2014 ; 2023 ) have categorized these fields into LPS (life sciences, psychology, and social sciences) and GEMP (geosciences, engineering, economics, mathematics/computer science). LPS-fields tend to have a higher share of women and GEMP-fields a lower share of women. Osterloh et al. (2023) distinguish between female-dominated fields of study (more than 70% of women) and male-dominated fields of study (more than 70% of men). A more precise classifications might lead to a different size of the GEP.

Second, the correlation between the “propensity of women to graduate with STEM degrees” and formal gender equality is based on cross-country data. However, “propensity of women to graduate with STEM degrees” is an individual disposition. Assumptions about individual characteristics solely based on group-level data can lead to incorrect conclusions. Consider a scenario in which countries with a high average GDP consist of very few extremely wealthy individuals and many poor individuals, e.g., South Africa. 4 In Switzerland, there is a relatively high gap between male- and female-dominated fields of study ( Osterloh et al. , 2023 ), thus the GEP matters to a high degree. Yet among women in STEM-fields there are many migrants from countries with a low GDP and a low level of women´s empowerment. Policy implications not taking this fact into account would be misleading.

Third, the GEP suggests causality between wealth and gender equality and gender-specific values. For example, Falk and Hermle (2018) propose as an explanation for their findings the “resource hypothesis”. This hypothesis predicts that the greater availability and gender-equal access to material and social resources as well as the lower exposure of women to male influence reduces economic pressures. It opens opportunities for gender-specific ambitions and desires and contributes to the expression of gender-differentiated preferences across countries. The underlying assumption of the resource hypothesis is inherently different characteristics of men and women. The resource hypothesis thus assumes that affluence causes gender-differentiated preferences. However, causality can only be inferred by panel data or laboratory experiments. To our knowledge, such data do not exist.

Nevertheless, numerous research papers show a cross-county association between affluence of a society, gender equality, and gender gaps in STEM. We acknowledge the difficulties in measuring this gender gap and refrain from assuming causality due to the absence of panel data or experimental evidence on the GEP. Therefore, in the next chapters, we focus on possible explanations of the observed positive correlation between wealth and gender gaps in STEM and why it matters for gender policy.

Possible explanations for the Gender Equality Paradox

Undoubtedly, there is greater financial security associated with STEM degrees which is particularly important for poor countries with little social security ( Stoet & Geary, 2020 ). However, this applies equally to men and women. What then increases the difference between the proportion of male and female STEM students with rising wealth and formal equality?

We try to explain this fact in four steps. In the first step, we draw on the empirical study by Breda et al. (2020) . The authors show that the stereotype "math is not for girls" is more widespread in rich, egalitarian countries compared to poor, non-egalitarian countries. That is, horizontal gender norms are stronger. At the same time, in egalitarian, rich countries, a general superiority of men is rejected, as expressed for example in the statement "a university degree is more important for men than for women", i.e., traditional vertical gender norms have become weaker. Consequently, horizontal, and traditional vertical gender norms today are negatively correlated. This means that women want to be equal concerning formal rights but different in their professional aspirations. This new gender norm termed “equal but different,” is most prevalent among affluent and well-educated couples. A new cult of motherhood is arising among wealthy families ( Goldin, 2021 ): men take “greedy jobs” with 50 to 70 hours work per week and high earnings, and women work in family-and child-friendly jobs with limited career opportunities. Women with such role norms often chose humanities and social fields of study ( Combet, 2023 ). These fields are characterized by a lower decay of knowledge than STEM fields. They allow women to re-enter the workforce more easily after maternity leave ( Ferriman et al. , 2009 ). But which horizontal gender norms gain salience with wealthy families while traditional vertical gender norms erode?

To answer this question, in a second step, we draw on the study by Falk and Hermle (2018) which tells us about the contents of different preferences between men and women. The authors state that the gender difference increases for several fundamental preferences in rich, egalitarian countries. In our context, the difference in altruism is particularly important. Consistent with this finding, Eagly et al. (2020) show that in the USA over the past 80 years, as wealth has increased, the stereotyping of women as "communal" or caring has increased, but that of men has not. The growing gender gap in altruism is important because most STEM careers are not driven by altruistic goals ( Diekman et al., 2010 ). We conclude that in wealthy countries there is an increasing difference in preferences for STEM subjects due to the increase in stereotyping women as communal. Violation of such stereotypes causes identity costs ( Akerlof & Kranton, 2000 ; Akerlof & Kranton, 2010 ). As a result, identity costs increase for women who choose STEM subjects in rich, egalitarian countries. For men, these identity costs do not change.

Third, we draw on the results of happiness research, according to which there is a decreasing marginal utility of wealth ( Frey & Stutzer, 2002 ; Layard et al., 2008 ). Higher income increases life satisfaction less in rich countries than in poor countries. At the same time, the identity costs for women in choosing STEM subjects increase, because in wealthy countries, stereotyping women as communal has increased. This leads to a relatively lower share of female STEM graduates in these countries. However, why the stereotyping of women as communal or caring has increased in rich countries remains unexplained.

As a result, we find some possible explanations for the initially counterintuitive "Gender Equality Paradox". In rich, gender-equal countries for women pursuing STEM careers the increase in utility of wealth is lower than the increase of identity costs. As a result, women avoid identity costs. In poor countries with low formal gender equality the opposite is true because wealth matters more than identity costs. However, we find no explanation for the increase in communal preferences of women in wealthy countries. We do not know whether this is due to a biological “gender essentialism”, or due to a deep history of learned cultural gender norms, e.g., the persistence of the male breadwinner model ( Tinsley et al., 2015 ). Alesina et al. (2013) and Jayachandran (2015) show traditional cultural imprints of values and norms are very stable. In any case, as long as there are no panel data or experimental findings, causality cannot be claimed.

Why does the Gender Equality Paradox matter?

Reducing the GEP—if possible—would offer two advantages. First, more female STEM graduates would counteract the shortage of STEM occupations and promote innovation. The higher the share of female STEM graduates, the higher the number of female innovations ( Niggli & Rutzer, 2021 ; Rutzer & Weder 2021 ).

Second, more female STEM graduates would reduce the gender wage gap between men and women because in most countries STEM-related education is associated with higher earnings ( Kirkeboen et al., 2016 ). For example, in Switzerland, Austria, and Germany, men earn about 20 percent more per hour than women ( European commission, 2020 ). This wage gap to a great part is due to the low percentage of women occupied in well-paid STEM professions. In Germany, graduates in academic STEM subjects earn 17% more than those in non-STEM subjects ( Anger et al., 2021 ). In addition, as soon as children arrive, gender wage gaps enlarge because the lower-earning mother is likely to restrict her working hours more than the well-paid father with a STEM degree. In Germany the part-time rate of women increased from 38 to 68% ( Lott et al., 2022 ), and in Austria from 37 to 65%. 5 Moreover, the mother's career prospects decrease when returning to a full-time job ( Zweimüller, 2021 ), as well as her retirement income and her income security in case of a divorce.

As a consequence, a new paradox arises: The growing GEP in wealthy and gender-equal countries will lead to an increase in the gender wage gap and possibly to a growing power imbalance within partnerships. Yet, this development obviously is not perceived as problematic in our countries. The literature on subjective well-being demonstrates that on average life satisfaction of women in wealthy countries is as high as that of men, even though they earn less and expect lower retirement incomes than men ( Schröder, 2020 ). An explanation might be that the new cult of motherhood and family-friendly occupations reduce the conflicts regarding the costs and quality of childcare. It also enables higher fertility and more intense childcare. Welfare states should not only be rich in equality but also rich in children to be sustainable. Analyses that balance these advantages and disadvantages of a growing GEP are urgently needed.

Conclusions

The "Gender Equality Paradox" (GEP) reveals that richer, gender-equal countries have a larger gender gap in STEM graduation compared to poorer, non-gender-equal countries. We propose a theoretical explanation of the GEP. In rich, gender-equal countries, stereotyping of women as "communal" or caring has increased, leading to higher identity costs for women pursuing STEM careers. Also, the value of the STEM income premium is lower for women in such countries due to the decreasing marginal utility of money. For women in poor, gender-unequal countries, the opposite holds. In these countries, for girls, marginal utility of money matters more than identity costs. With this approach, we can give a more detailed explanation of the GEP than former proposals. This we consider as the strength of our paper. However, a weakness consists in the lack of causality between wealth and communal preferences of women.

Overall, our considerations lead to the prediction that as wealth and formal equality increases, the gender pay gap will become even larger. Possibly the power imbalance within partnerships also increases. A new, surprising paradox would arise. A first step to test the assumptions of our theoretical explanation would need to develop a measurement of identity costs in order to compare these costs in rich and poor countries. This would include an operationalisation of the concept of identity costs, which is still outstanding.

Further research is needed to explore three crucial aspects. First, it is important to investigate the correlation between the wealth of a country and its democracy index. High democratic values might influence the choice of individuals concerning STEM subjects. Second, we need to understand why the preferences of men and women in wealthy countries diverge. Is it biology, inertia of norms, gender marketing or something else? Third, we should analyse the possible advantages and disadvantages of a growing GEP in the light of life satisfaction, fertility and quality of childcare on the one hand and the gender wage gap on the other hand. Further investigations of these factors will provide valuable insights into the complex interplay of societal and individual influences on preferences and career choices.

Data availability

No data are associated with this article.

Acknowledgments

We thank Milena Milosavljevic for her help with literature research.

1 https://genderdata.worldbank.org/indicators/se-ter-grad-fe-zs/?fieldOfStudy=Science%2C%20Technology%2C%20Engineering%20and%20Mathematics%20%28STEM%29&view=bar

2 There is a strong positive correlation between a country’s Gross Domestic Product and measures of formal gender equality, see Duflo (2012) .

3 Falk and Hermle (2018) do not relate explicitly to the gender equality paradox.

4 In such cases, it would be suitable to consider the median instead of the average GDP per capita.

5 https://www.statistik.at/statistiken/arbeitsmarkt/erwerbstaetigkeit/familie-und-erwerbstaetigkeit

- Akerlof GA, Kranton RE: Economics and Identity. Q J Econ. 2000; 115 (3): 715–753. Reference Source

- Akerlof GA, Kranton RE: Identity Economics: How Our Identities Shape Our Work, Wages, and Well-Being. Princeton University Press, 2010. Reference Source

- Alesina A, Giuliano P, Nunn N: On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough. Q J Econ. 2013; 128 (2): 469–530. Publisher Full Text

- Anger C, Kohlisch E, Koppel O, et al. : Mint-Frühjahrsreport 2021. MINT-Engpässe und Corona-Pandemie: von den konjunkturellen zu den strukturellen Herausforderungen. Gutachten für BDA BDI, MINT Zukunft schaffen und Gesamtmetall, Köln, 2021. Reference Source

- Breda T, Jouini E, Napp C, et al. : Gender Stereotypes Can Explain the Gender-Equality Paradox. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117 (49): 31063–31069. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- Ceci SJ, Ginther DK, Kahn S, et al. : Women in Academic Science: A Changing Landscape. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2014; 15 (3): 75–141. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Ceci SJ, Kahn S, Williams WM: Exploring Gender Bias in Six Key Domains of Academic Science: An Adversarial Collaboration. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2023; 24 (1): 15–73. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- Combet B: Women’s aversion to majors that (seemingly) require systemizing skills causes gendered field of study choice. Eur Sociol Rev. 2023; jcad021. Publisher Full Text

- Diekman AB, Brown ER, Johnston AM, et al. : Seeking Congruity between Goals and Roles: A New Look at Why Women Opt out of Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Careers. Psychol Sci. 2010; 21 (8): 1051–1057. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Duflo E: Women Empowerment and Economic Development. J Econ Lit. 2012; 50 (4): 1051–1079. Publisher Full Text

- Eagly AH, Nater C, Miller DI, et al. : Gender Stereotypes Have Changed: A Cross-Temporal Meta-Analysis of U.S. Public Opinion Polls from 1946 to 2018. Am Psychol. 2020; 75 (3): 301–315. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Eccles J: Expectancies, Values and Academic Behaviors. Achievement and achievement motives . 1983; 75–146.

- European commission: The gender pay gap situation in the EU. 2020. Reference Source

- Falk A, Hermle J: Relationship of Gender Differences in Preferences to Economic Development and Gender Equality. Science. 2018; 362 (6412): eaas9899. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Federkeil G, Friedhoff CC: U-Multirank Gender Monitor 2022 – Gender Disparities in Higher Education. CHE Centrum für Hochschulentwicklung. 2022. Reference Source

- Ferriman K, Lubinski D, Benbow CP: Work preferences, life values, and personal views of top math/science graduate students and the profoundly gifted: Developmental changes and gender differences during emerging adulthood and parenthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2009; 97 (3): 517–32. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Frey BS, Stutzer A: What Can Economists Learn from Happiness Research? J Econ Lit. 2002; 40 (2): 402–435. Publisher Full Text

- Goldin C: Career and Family: Women’s Century-Long Journey toward Equity. Princeton University Press, 2021. Reference Source

- Hizli L, Mösching A, Osterloh M: Warum Ist Der Anteil Von Mint-Absolventinnen in Marokko Höher Als Bei Uns? Ökonomenstimme, 18. Januar, 2022. Reference Source

- Jayachandran S: The Roots of Gender Inequality in Developing Countries. Annu Rev Econom. 2015; 7 (1): 63–88. Publisher Full Text

- Kirkeboen LJ, Leuven E, Mogstad M: Field of Study, Earnings, and Self-Selection. Q J Econ. 2016; 131 (3): 1057–1111. Publisher Full Text

- Layard R, Mayraz G, Nickell S: The Marginal Utility of Income. J Public Econ. 2008; 92 (8–9): 1846–1857. Publisher Full Text

- Lott Y, Hobler D, Pfahl S, et al. : Stand Der Gleichstellung Von Frauen Und Männern in Deutschland. 2022.

- Napp C, Breda T: The Stereotype That Girls Lack Talent: A Worldwide Investigation. Sci Adv. 2022; 8 (10): eabm3689. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- Niggli M, Rutzer C: A Gender Gap to More Innovation in Switzerland. 2021. Reference Source

- Osterloh M, Rost K, Hizli L, et al. : How to Explain the Leaky Pipeline? Working Paper University Zurich, 2023.

- Richardson SS, Reiches MW, Bruch J, et al. : Is There a Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (Stem)? Commentary on the Study by Stoet and Geary (2018). Psychol Sci. 2020; 31 (3): 338–341. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Rutzer C, Weder R: Gefährdet Das Fehlen Von Mint-Absolventinnen Den Innovationsstandort Schweiz? Neue Zürcher Zeitung. 2021; 1–7. Reference Source

- Schröder M: Men Lose Life Satisfaction with Fewer Hours in Employment: Mothers Do Not Profit from Longer Employment—Evidence from Eight Panels. Soc Indic Res. 2020; 152 (1): 317–334. Publisher Full Text

- Stoet G, Geary DC: The Gender-Equality Paradox in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics Education. Psychol Sci. 2018; 29 (4): 581–593. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Stoet G, Geary DC: Gender Differences in the Pathways to Higher Education. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020; 117 (25): 14073–14076. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- Stoet G, Geary DC: Sex Differences in Adolescents’ Occupational Aspirations: Variations across Time and Place. PLoS One. 2022; 17 (1): e0261438. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- Thelwall M, Mas-Bleda A: A Gender Equality Paradox in Academic Publishing: Countries with a Higher Proportion of Female First-Authored Journal Articles Have Larger First-Author Gender Disparities between Fields. Quant Sci Stud. 2020; 1 (3): 1260–1282. Publisher Full Text

- Tinsley CH, Howell TM, Amanatullah ET: Who should bring home the bacon? How deterministic views of gender constrain spousal wage preferences. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2015; 126 : 37–48. Publisher Full Text

- Vishkin A: Queen’s Gambit Declined: The Gender-Equality Paradox in Chess Participation across 160 Countries. Psychol Sci. 2022; 33 (2): 276–284. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text

- Wang MT, Degol J: Motivational Pathways to Stem Career Choices: Using Expectancy–Value Perspective to Understand Individual and Gender Differences in Stem Fields. Dev Rev. 2013; 33 (4): 304–340. PubMed Abstract | Publisher Full Text | Free Full Text

- Zweimüller J: Karriereknick Mutterschaft. Schweizer Monat, 2021; (1092). Reference Source

Comments on this article Comments (0)

Open peer review.

- The abstract provides a concise overview of the article's content, including the definition of the Gender Equality Paradox (GEP) and its implications. However, it could be improved by briefly mentioning the main findings or conclusions of the

- The abstract provides a concise overview of the article's content, including the definition of the Gender Equality Paradox (GEP) and its implications. However, it could be improved by briefly mentioning the main findings or conclusions of the study.

- The introduction effectively introduces the concept of the Gender Equality Paradox and provides context for its significance. However, it would be beneficial to include a clear statement of the research objectives or hypotheses to guide the reader. The references to specific countries and their gender disparities in STEM fields provide concrete examples but could be supplemented with additional data or statistics to enhance the argument's persuasiveness.

- Empirical evidence for the Gender Equality Paradox: The section provides a comprehensive review of existing studies on the GEP, demonstrating a thorough understanding of the topic. However, it would be helpful to summarize the key findings of each study to facilitate easier comprehension. The use of various studies and datasets strengthens the credibility of the argument. However, it may be beneficial to incorporate more recent studies, to ensure the information is up-to-date.

- Objections to the Gender Equality Paradox: The section effectively addresses objections to the GEP raised by previous research, demonstrating a critical engagement with the literature. However, it could benefit from a more structured presentation of the objections and the corresponding responses. The inclusion of alternative measures of gender equality and women in STEM fields adds depth to the analysis but could be further elaborated to clarify their significance.

- Possible explanations for the Gender Equality Paradox: The section offers compelling theoretical explanations for the GEP, drawing on existing literature to support the argument. However, it could be strengthened by providing more explicit connections between the proposed explanations and the empirical evidence presented earlier.

- The discussion of identity costs and the decreasing marginal utility of wealth offers valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying the GEP. However, additional clarification may be needed to fully elucidate these concepts.

- Why does the Gender Equality Paradox matter?: The section effectively highlights the implications of the GEP for gender equality and economic outcomes. However, it could be enhanced by discussing potential policy implications or recommendations based on the findings. The consideration of both advantages and disadvantages of the GEP adds nuance to the discussion but could be expanded to provide a more comprehensive analysis of its societal impact.

- Conclusions: The conclusions succinctly summarize the key findings of the study and highlight areas for future research. However, it may be beneficial to reiterate the main contributions of the study and their implications for understanding the GEP.

Is the topic of the opinion article discussed accurately in the context of the current literature?

Are all factual statements correct and adequately supported by citations?

Are arguments sufficiently supported by evidence from the published literature?

Are the conclusions drawn balanced and justified on the basis of the presented arguments?

Competing Interests: No competing interests were disclosed.

Reviewer Expertise: My research interests are in socio-educational approaches, and especially gender equality, gender mainstreaming and gender equality in STEM areas, because of the gender gap in the STEM sector.

- Respond or Comment

- COMMENT ON THIS REPORT

Reviewer Expertise: gender inequality, divorce, homogamy

- The authors frequently use

- The authors frequently use the term “identity costs,” which refers to two papers by Akerlof and Kranton. At the end of the paper under review, the authors assume that it is worthwhile to operationalize the concept of “identity costs” to measure them. Throughout the paper, what “identity costs” may mean in the context discussed did not become fully clear to the reviewer. As the concept seems to be of high importance for further developing the “Gender Equality Paradox” (GEP), a few additional sentences for clarification might be helpful.

- Perhaps it is too early to formulate concrete research hypotheses on the authors’ uptake and further development of GEP research. However, the paper might gain a lot by developing and adding such hypotheses.

Reviewer Expertise: Higher Education Research, Science Studies, Organizational Research, Neo-institutional Theory

Reviewer Status

Alongside their report, reviewers assign a status to the article:

Reviewer Reports

- Georg Krücken , University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany

- Wilfred Uunk , University of Innsbruck, Innsbruck, Austria

- Sonia Verdugo-Castro , University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

Comments on this article

All Comments (0)

Competing Interests Policy

Provide sufficient details of any financial or non-financial competing interests to enable users to assess whether your comments might lead a reasonable person to question your impartiality. Consider the following examples, but note that this is not an exhaustive list:

- Within the past 4 years, you have held joint grants, published or collaborated with any of the authors of the selected paper.

- You have a close personal relationship (e.g. parent, spouse, sibling, or domestic partner) with any of the authors.

- You are a close professional associate of any of the authors (e.g. scientific mentor, recent student).

- You work at the same institute as any of the authors.

- You hope/expect to benefit (e.g. favour or employment) as a result of your submission.

- You are an Editor for the journal in which the article is published.

- You expect to receive, or in the past 4 years have received, any of the following from any commercial organisation that may gain financially from your submission: a salary, fees, funding, reimbursements.

- You expect to receive, or in the past 4 years have received, shared grant support or other funding with any of the authors.

- You hold, or are currently applying for, any patents or significant stocks/shares relating to the subject matter of the paper you are commenting on.

Stay Updated

Sign up for content alerts and receive a weekly or monthly email with all newly published articles

Register with Routledge Open Research

Already registered? Sign in

Not now, thanks

Stay Informed

Sign up for information about developments, publishing and publications from Routledge Open Research.

We'll keep you updated on any major new updates to Routledge Open Research

The email address should be the one you originally registered with F1000.

You registered with F1000 via Google, so we cannot reset your password.

To sign in, please click here .

If you still need help with your Google account password, please click here .

You registered with F1000 via Facebook, so we cannot reset your password.

If you still need help with your Facebook account password, please click here .

If your email address is registered with us, we will email you instructions to reset your password.

If you think you should have received this email but it has not arrived, please check your spam filters and/or contact for further assistance.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(4); 2021 Apr

Gendered stereotypes and norms: A systematic review of interventions designed to shift attitudes and behaviour

Rebecca stewart.

a BehaviourWorks Australia, Monash Sustainable Development Institute, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Breanna Wright

Steven roberts.

b School of Social Sciences, Faculty of Arts, Monash University, Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Natalie Russell

c Victorian Health Promotion Foundation (VicHealth), Melbourne, Victoria, Australia

Associated Data

Data included in article.

In the face of ongoing attempts to achieve gender equality, there is increasing focus on the need to address outdated and detrimental gendered stereotypes and norms, to support societal and cultural change through individual attitudinal and behaviour change. This article systematically reviews interventions aiming to address gendered stereotypes and norms across several outcomes of gender inequality such as violence against women and sexual and reproductive health, to draw out common theory and practice and identify success factors. Three databases were searched; ProQuest Central, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Articles were included if they used established public health interventions types (direct participation programs, community mobilisation or strengthening, organisational or workforce development, communications, social marketing and social media, advocacy, legislative or policy reform) to shift attitudes and/or behaviour in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms. A total of 71 studies were included addressing norms and/or stereotypes across a range of intervention types and gender inequality outcomes, 55 of which reported statistically significant or mixed outcomes. The implicit theory of change in most studies was to change participants' attitudes by increasing their knowledge/awareness of gendered stereotypes or norms. Five additional strategies were identified that appear to strengthen intervention impact; peer engagement, addressing multiple levels of the ecological framework, developing agents of change, modelling/role models and co-design of interventions with participants or target populations. Consideration of cohort sex, length of intervention (multi-session vs single-session) and need for follow up data collection were all identified as factors influencing success. When it comes to engaging men and boys in particular, interventions with greater success include interactive learning, co-design and peer leadership. Several recommendations are made for program design, including that practitioners need to be cognisant of breaking down stereotypes amongst men (not just between genders) and the avoidance of reinforcing outdated stereotypes and norms inadvertently.

Gender; Stereotypes; Social norms; Attitude change; Behaviour change; Men and masculinities

1. Introduction

Gender is a widely accepted social determinant of health [ 1 , 2 ], as evidenced by the inclusion of Gender Equality as a standalone goal in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals [ 3 ]. In light of this, momentum is building around the need to invest in gender-transformative programs and initiatives designed to challenge harmful power and gender imbalances, in line with increasing acknowledgement that ‘restrictive gender norms harm health and limit life choices for all’ ([ 2 ] pe225, see also [ 1 , 4 ]).

Gender-transformative programs and interventions seek to critically examine gender related norms and expectations and increase gender equitable attitudes and behaviours, often with a focus on masculinity [ 5 , 6 ]. They are one of five approaches identified by Gupta [ 6 ] as part of a continuum that targets social change via efforts to address gender (in particular gender-based power imbalances), violence prevention and sexual and reproductive health rights. The approaches in ascending progressive order are; reinforcing damaging gender (and sexuality) stereotypes, gender neutral, gender sensitive, gender-transformative , and gender empowering. The emerging evidence pertaining to the effectiveness of gender-transformative interventions points to the importance of programs challenging the gender binary and related norms, as opposed to focusing only on specific behaviours or attitudes [ 1 , 7 , 8 ]. This understanding is in part derived from a growing appreciation of the need to address outdated and detrimental gendered stereotypes and norms in order to support societal and cultural change in relation to this issue [ 9 , 10 , 11 ]. In addition to this focus on gender-transformative interventions is an increasing call for the engagement of men and boys not only as allies but as participants, partners and agents of change in gender equality efforts [ 12 , 13 ].

When examining the issue of gender inequality, it is necessary to consider the underlying drivers that allow for the maintenance and ongoing repetition of sex-based disparities in access to resources, power and opportunities [ 14 ]. The drivers can largely be categorised as either, ‘structural and systemic’, or ‘social norms and gendered stereotypes’ [ 15 ]. Extensive research and work has, and continues to be, undertaken in relation to structural and systemic drivers. From this perspective, efforts to address inequalities have focused on areas societal institutions exert influence over women's rights and access. One example (of many) is the paid workforce and attempts to address unequal gender representation through policies and practices around recruitment [ 16 , 17 ], retention via tactics such as flexible working arrangements [ 18 , 19 , 20 ] and promotion [ 16 ].

The focus of this review, however, is stereotypes and norms, incorporating the attitudes, behavioural intentions and enacted behaviours that are produced and reinforced as a result of structures and systems that support inequalities. Both categories of drivers (structural and systemic and social norms and gendered stereotypes) are influenced by and exert influence upon each other. Heise and colleagues [ 12 ] suggest that gendered norms uphold the gender system and are embedded in institutions (i.e. structurally), thus determining who occupies positions of leadership, whose voices are heard and listened to, and whose needs are prioritised [ 10 ]. As noted by Kågesten and Chandra-Mouli [ 1 ], addressing both categories of drivers is crucial to the broader strategy needed to meet the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Stereotypes are widely held, generalised assumptions regarding common traits (including strengths and weaknesses), based on group categorisation [ 21 , 22 ]. Traditional gendered stereotypes see the attribution of agentic traits such as ambition, power and competitiveness as inherent in men, and communal traits such as nurturing, empathy and concern for others as characteristics of women [ 21 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 ]. In addition to these descriptive stereotypes (i.e. beliefs about specific characteristics a person possesses based on their gender) are prescriptive stereotypes, which are beliefs about specific characteristics that a person should possess based on their gender [ 21 , 25 ]. Gender-based stereotypes are informed by social norms relating to ideals and practices of masculinity and femininity (e.g. physical attributes, temperament, occupation/role suitability, etc.), which are subject to the influence of culture and time [ 15 , 21 , 26 ].

Social norms are informal (often unspoken) rules governing the behaviour of a group, emerging out of interactions with others and sanctioned by social networks [ 27 ]. Whilst stereotypes inform our assumptions about someone based on their gender [ 21 ], social norms govern the expected and accepted behaviour of women and men, often perpetuating gendered stereotypes (i.e. men as agentic, women as communal) [ 12 ]. Cialdini and Trost [ 27 ] delineate norms by suggesting that, in addition to these general societal behavioural expectations (see also [ 28 , 29 ]), there are personal norms (what we expect of ourselves) [ 30 ], and subjective norms (what we think others expect of us) [ 31 ]. Within subjective norms, there are injunctive norms (behaviours perceived as being approved by others) and descriptive norms (our observations and expectations of what most others are doing). Despite being malleable and subjective to cultural and socio-historical influences, portrayals and perpetuation of these stereotypes and social norms restrict aspirations, expectations and participation of both women and men, with demonstrations of counter-stereotypical behaviours often met with resistance and backlash ([ 12 , 24 , 32 ], see also [ 27 , 33 ]). These limitations are evident both between and among women and men, demonstrative of the power hierarchies that gender inequality and its drivers produce and sustain [ 12 ].

There is an extensive literature that explores interventions targeting gendered stereotypes and norms, each focusing on specific outcomes of gender inequality, such as violence against women [ 13 ], gender-based violence and sexual and reproductive health (including HIV prevention, treatment, care and support) [ 5 , 8 ], parental involvement [ 34 ], sexual and reproductive health rights [ 23 , 35 ], and health and wellbeing [ 2 ]. Comparisons of learnings across these focus areas remains difficult however due to the current lack of a synthesis of interventions across outcomes.

Despite this gap, one of the key findings to arise out of the literature relates to the common, and often implicit, theory of change around shifting participants' attitudes by increasing their knowledge/awareness of gendered stereotypes or norms, and the assumption that this will then lead to behaviour change. This was identified by Jewkes and colleagues [ 13 ] in their review of 67 intervention evaluations in relation to the prevention of violence against women, a finding they noted was in contradiction of research across disciplines which has consistently found this relationship to be complex and bidirectional [ 36 , 37 ]. Similarly, The International Centre for Research on Women indicate the ‘problematic assumption[s] regarding pathways to change’ ([ 7 ] p26) as one of the challenges to engaging men and boys in gender equality work, noting also the focus of evaluation, when undertaken, being on changes in attitude rather than behaviour. Ruane-McAteer and colleagues [ 35 ] made the same observation when looking at interventions aimed at gender equality in sexual and reproductive health, highlighting the need for greater interrogation into the intended outcomes of interventions including what the underlying theory of change is. These findings lend further support to the utilisation of the gender-transformative approach identified by Gupta [ 6 ] if fundamental and sustained shifts in understanding, attitudes and behaviour relating to gender inequality is the desired outcome.

In sum, much is known about gender stereotypes and norms and the contribution they make to perpetuating and sustaining gender inequality through the various outcomes discussed above. Less is known however about how to support and sustain more equitable attitudes and behaviours when it comes to addressing gender equality more broadly. This systematic review aims to address the question which intervention characteristics support change in attitudes and behaviour in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms. It will do this by consolidating the literature to determine what has been done and what works. This includes querying which intervention types work for whom in terms of participant age and sex, as well as delivery style and duration. Additionally, it will consider the theories of change being used to address attitudes and behaviours and how these shifts are being measured, including for impact longevity. Finally, it will allow for insight into interventions specifically targeting men and boys in relation to rigid gender stereotypes and norms, seeking out particular characteristics that are supportive of work engaging this particular cohort. These questions are intentionally broad and based on the framing of the above question it is expected that the review will capture primarily interventions that address underlying societal factors that support a culture in which harmful power and gender imbalances exist by addressing gender inequitable attitudes and behaviours. In asking these questions, this review consolidates the knowledge generated to date, to strengthen the design, development and implementation of future interventions, a synthesis that appears to be both absent and needed.

2.1. Data sources and search strategy

This review was undertaken in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [ 38 ]. A protocol was registered on the Open Science Framework (Title: Gendered norms: A systematic review of how to achieve change in rigid gender stereotypes, accessible at https://osf.io/gyk25/ ). Qualitative, quantitative and mixed method studies were identified through three electronic databases searched in February 2019 (ProQuest Central, PsycINFO and Web of Science). Four search strategies were developed in consultation with a subject librarian and tested across all three databases. The final strategy was confirmed by the lead author and a second reviewer (see Table 1 ).

Table 1

Search terms used.

There were no date or language exclusions, Title, Abstract & Keyword filters were applied where possible, and truncation was used in line with database specifications. The following intervention categories were included due to their standing in public health literature as being effective to create population level impact and having proven effective in addressing other significant health and social issues [ 39 ]; direct participation programs (referred to also as education based interventions throughout this review), community mobilisation or strengthening, organisational or workforce development, communications, social marketing and social media, advocacy, legislative or policy reform. Table 2 provides descriptions of each of these intervention categories that have been obtained from the actions outlined in the World Health Organisation's Ottawa Charter [ 40 ] and Jakarta Declaration [ 41 ] and are a comprehensive set of strategies grounded in prevention theory [ 42 ]. For the purposes of this review, legislative and policy reform within community, educational, organisational and workforce settings were included. Government legislation and policy reform were excluded.

Table 2

Public health intervention categories.

2.2. Screening

Initial search results were merged and duplicates removed using EndNote before transferring data management to Covidence for screening. Two researchers independently screened titles and abstracts excluding studies based on the criteria stipulated in Table 3 .

Table 3

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The University Library document request service was used to obtain articles otherwise inaccessible or in languages other than English. In cases where full-text or English versions were unable to be obtained, the study was excluded. Full-text screening was undertaken by the same two researchers independently and the final selection resulted in 71 included studies (see Figure 1 ).

PRISMA diagram of screening and study selection.

2.3. Data extraction

Data extraction was undertaken by the first author and checked for accuracy by the second author. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus with the remaining three authors. The extracted data included: citation, year and location of study, participant demographics (gender, age), study design, setting, theoretical underpinnings, motivation for study, measurement tools/instruments, primary outcomes and results. A formal meta-analysis was not conducted given heterogeneity of outcome variables and measures, due in part to the broad nature of the review question.

2.4. Quality appraisal

Three established quality appraisal tools were used to account for the different study designs included, the McMasters Critical Review Form – Qualitative Studies 2.0 [ 43 ], the McMasters Critical Review Form – Quantitative Studies [ 44 ], Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018 [ 45 ]. The first author completed quality appraisal for all studies, with the second author undertaking an accuracy check on ten percent of studies. The appraisal score represents the proportion of ‘yes’ responses out of the total number of criteria. ‘Not reported’ was treated as a ‘no’ response. A discussion of the outcomes is located under Results.

2.5. Data synthesis

Included studies were explored using a modified narrative synthesis approach comprising three elements; developing a theory of how interventions worked, why and with whom, developing a preliminary synthesis of findings of included studies, and exploring relationships in studies reporting statistically significant outcomes [ 46 ]. Preliminary analysis was conducted using groupings of studies based on intervention type and thematic analysis based on gender inequality outcomes driving the study and features of the studies including participant sex and age and intervention delivery style and duration [ 46 ]. A conceptual model was developed (see Theory of Change section under Results) as the method of relationship exploration amongst studies reporting significant results, using qualitative case descriptions [ 47 ]. The narrative synthesis was undertaken under the premise that the ‘evidence being synthesised in a systematic review does not necessarily offer a series of discrete answers to a specific question’, so much as ‘each piece of evidence offers are partial picture of the phenomenon of interest’ ([ 46 ] p21).

3.1. Literature search

The literature search returned 4,050 references after the removal of duplicates (see Figure 1 ), from which 210 potentially relevant abstracts were identified. Full-text review resulted in a final list of 71 articles evaluating 69 distinct interventions aligned with the public health methodologies outlined in Table 2 . Table 4 provides a list of the included studies, categorised by intervention type. Studies fell into eight categories of interventions in total, with several combining two methodology types described in Table 2 .

Table 4

Included articles categorised by intervention type.

3.2. Quality assessment

Overall, the results of the quality appraisal indicated a moderate level of confidence in the results. The appraisal scores for the 71 studies ranged from poor (.24) to excellent (.96). The median appraisal score was .71 for all included studies (n = 71) and .76 for studies reporting statistically significant positive results (n = 32). The majority of studies were rated moderate quality (n = 57, 80%), with moderate quality regarded as .50 - .79 [ 119 ]. Ten studies were regarded as high quality (14%, >.80), and four were rated as poor (6%, <.50) [ 119 ]. Of the studies with significant outcomes, one rated high quality (.82) and the remaining 31 were moderate quality, with 18 of these (58% of 31) rating >.70. For the 15 randomised control trials (including n = 13 x cluster), all articles provided clear study purposes and design, intervention details, reported statistical significance of results, reported appropriate analysis methods and drew appropriate conclusions. However, only four studies appropriately justified sampling process and selection. For the qualitative studies (n = 5), the lowest scoring criteria were in relation to describing the process of purposeful selection (n = 1, 20%) and sampling done until redundancy in data was reached (n = 2, 40%). For the quantitative studies (n = 47) the lowest scoring criteria were in relation to sample size justification (n = 8, 17%) and avoiding contamination (n = 1, 2%) and co-intervention (n = 0, none of the studies provided information on this) in regards to intervention participants. For the Mixed Method studies (n = 19) the lowest scoring criteria in relation to the qualitative component of the research was in relation to the findings being adequately derived from the data (n = 9, 47%), and for the mixed methods criteria it was in relation to adequately addressing the divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results (n = 6, 32%).

3.3. Measures

Measures of stereotypes and norms varied across quantitative and mixed method studies with 31 (47%) of the 66 articles reporting the use of 25 different psychometric evaluation tools. The remaining 35 (53%) of quantitative and mixed methods studies reported developing measurement tools specific to the study with inconsistencies in description and provision of psychometric properties. Of the studies that used psychometric evaluation tools, the most frequently used were the Gender Equitable Men Scale (GEMS, n = 6, plus n = 2 used questions from the GEMS), followed by the Gender Role Conflict Scale I (GRCS-I, n = 5, plus n = 1 used a Short Form version) and the Gender-Stereotyped Attitude Scale for Children (GASC, n = 5). Whilst most studies used explicit measures as listed here, implicit measures were also used across several studies, including the Gender-Career Implicit Attitudes Test (n = 1). The twenty-four studies that undertook qualitative data collection used interviews (participant n = 15, key informant n = 3) as well as focus groups (n = 8), ethnographic observations (n = 5) and document analysis (n = 2). Twenty (28%) of the 71 studies measured behaviour and/or behavioural intentions, of which 9 (45%) used self-report measures only, four (20%) used self-report and observational data, and two (10%) used observation only. Follow-up data was collected for four of the studies using self-report measures, and two using observation measures, and one using both methods.

3.4. Study and intervention characteristics

Table 5 provides a summary of study and intervention characteristics. All included studies were published between 1990 and 2019; n = 8 (11%) between 1990 and 1999, n = 15 (21%) between 2000 and 2009, and the majority n = 48 (68%) from 2010 to 2019. Interventions were delivered in 23 countries (one study did not specify a location), with the majority conducted in the U.S. (n = 33, 46%), followed by India (n = 10, 14%). A further 15 studies (21%) were undertaken in Africa across East Africa (n = 7, Ethiopia, Malawi, Mozambique, Uganda), South Africa (n = 6), and West Africa (n = 2, Nigeria, Senegal). The remaining fifteen studies were conducted in Central and South America (n = 4, Mexico, Guatemala, El Salvador and Argentina), Europe (n = 3, Ireland, Spain and Turkey), Nepal (n = 2), and one study each in Australia, China, Oman, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the United Kingdom. Forty-seven (66%) studies employed quantitative methods, 19 (27%) reported both quantitative and qualitative (mixed) methods, and the remaining five studies (7%) reported qualitative methods. Forty-two of the quantitative and mixed-method approaches were non-randomised control trials, 13 were cluster randomised control trials, two were randomised control trials, and eight were quantitative descriptive studies.

Table 5

Summarised study and intervention characteristics (n = 71).

Based on total study sample sizes, data was reported on 46,673 participants. Sample sizes ranged from 15 to 122 for qualitative, 7 to 2887 for mixed methods, and 21 to 6073 for quantitative studies. Of the 71 studies, 23 (32%) reported on children (<18 years old), 13 (18%) on adolescents/young adults (<30 years old), 29 (41%) on adults (>18 years old), and six (8%) studies did not provided details on participant age. Thirty-seven (52%) studies recruited participants from educational settings (i.e. kindergarten, primary, middle and secondary/high school, tertiary including college residential settings, and summer camps/schools), 32 (45%) from general community settings (including home and sports), three from therapy-based programs for offenders (i.e. substance abuse and partner abuse prevention), and one sourced participants from both educational (vocational) and a workplace (factory).

As per Table 5 , the greatest proportion of all studies engaged mixed sex cohorts (n = 39, 55%), looked at norms (n = 34, 48%), were undertaken in community settings (n = 32, 45%), were education/direct participant interventions (n = 47, 66%) and undertook pre and post intervention evaluation (n = 49, 69%). Twenty-four studies reported on follow up data collection, with 10 reporting maintenance of outcomes.

Intervention lengths were varied, from individual sessions (90 min) to ongoing programs (up to 6 years) and were dependent on intervention type. Table 6 provides the duration range by intervention type.

Table 6

Intervention type and duration.

Of the 71 studies examined in this review, 10 (14%) stated a gender approach in relation to the continuum outlined at the start of this paper, utilising two of the five categories; gender-transformative and gender-sensitive [ 6 ]. Eight studies stated that they were gender-transformative, the definition of this strategy being to critically examine gender related norms and expectations and increase gender equitable attitudes and behaviours, often with a focus on masculinity [ 9 , 10 ]. An additional two stated they were gender-sensitive, the definition of which is to take into account and seek to address existing gender inequalities [ 10 ]. The remaining 61 (86%) studies did not specifically state engagement with a specific gender approach. Interpretation of the gender approach was not undertaken in relation to these 61 studies due to insufficient available data and to avoid potential risk of error, mislabelling or misidentification.

3.5. Characteristics supporting success

Due to the broad inclusion criteria for this review, there is considerable variation in study designs and the measurement of attitudes and behaviours. With the exception of the five studies using qualitative methods, all included studies reported on p-values, and 13 reported on effect sizes [ 51 , 60 , 66 , 69 , 70 , 71 , 77 , 78 , 79 , 83 , 92 , 99 , 110 ]. In addition to this, the centrality of gender norms and/or stereotypes within studies meeting inclusion criteria varied from a primary outcome to a secondary one, and in some studies was a peripheral consideration only, with minimal data reported. This heterogeneity prevents comparisons based purely on whether the outcomes of the studies were statistically significant, and as such consideration was also given to the inclusion of effect sizes, author interpretation, qualitative insights and whether outcomes reported as statistically non-significant reported encouraging results, which allowed for the inclusion of those using qualitative methods only [ 53 , 73 , 81 , 82 , 98 ].

As outlined in Table 5 , the studies were grouped into three categories based on reporting of statistical significance using p-values. Two categories include studies reporting statistically significant outcomes (n = 25) and those reporting mixed outcomes including some statistically significant results (n = 30), specifically in relation to the measurement of gender norms and/or stereotypes. Disparate outcomes included negligible behavioural changes, a shift in some but not all norms (i.e. shifts in descriptive but not personal norms, or masculine but not feminine stereotypes), and effects seen in some but not all participants (i.e. shifts in female participant scores but not male). It is worth noting that out of the 71 studies reviewed, all but one reported positive or negligible intervention impacts on attitudes and/or behaviours relating to gender norms and/or stereotypes. The other category include those reporting non-significant results (n = 2) as well as those that reported non-significant but positive results in relation to attitude and/or behaviour change towards gender norms and/or stereotypes (n = 14). These studies include those which had qualitative designs, several who reported on descriptive statistics only, and several which did not meet statistical significance but who demonstrated improvement in participant scores between base and end line and/or between intervention and control groups. The insights from the qualitative studies (n = 5) have been taken into consideration in the narrative synthesis of this review.

Studies reporting statistically significant outcomes were represented across seven of the eight intervention types. The only intervention category not represented was advocacy and education [ 48 ] which reported non-significant but positive results. The remainder of this section will consider the study characteristics of the statistically significant and mixed results categories, as well as identifying similar trends observed in the qualitative studies which reported positive but non-significant intervention outcomes. When considering intervention type, direct participant education was the most common, with 49 of the 55 studies reporting statistically significant or mixed outcomes containing a direct participant education component, and all but one of the five qualitative studies.

The majority of interventions reporting achievement of intended outcomes involved delivery of multiple sessions ranging from five x 20 min sessions across one week to multiple sessions across six years. This included 48 of the 55 studies reporting statistically significant or mixed outcomes, and all five qualitative studies. Only one of the seven that utilised single/one-off sessions reported significant outcomes. The remaining six studies had varying results, including finding shifts in descriptive but not personal norms amongst a male-only cohort, shifts in acceptance of both genders performing masculine behaviours but no shift in acceptance of males performing feminine behaviours, and significant outcomes for participants already demonstrating more egalitarian attitudes at baseline but not those holding more traditional ones – arguably the target audience.

When considering participant sex, the majority of studies reporting statistically significant or mixed results engaged mixed sex cohorts (n = 33 out of 55), with the remaining studies engaging male only (n = 13) and female only (n = 9) cohorts. Of the qualitative studies, three engaged mixed sex participant cohorts. Interestingly however, several studies reported disparate results, including significant outcomes for male but non-significant outcomes for female participants primarily in studies incorporating a community mobilisation element, and the reverse pattern in some studies that were education based. Additional discrepancies were found between several studies looking at individual and community level outcomes.

Finally, a quarter of studies worked with male only cohorts (n = 18). Of these, four reported significant results, nine reported mixed results, and the remaining five studies reported non-significant but positive outcomes, one of which was a qualitative study. Within these studies, two demonstrated shifts in more generalised descriptive norms and/or stereotypes relating to men, but not in relation to personal norms. Additionally, several studies demonstrated that shifts in male participant attitudes were not generalised, with discrepancies found in relation to attitudes shifting towards women but not men and in relation to some norms or stereotypes (for example men acting in ‘feminine’ ways) but not others that appeared to be more culturally entrenched. These studies are explored further in the Discussion.

In summary, interventions that used direct participant education, across multiple sessions, with mixed sex participant cohorts were associated with greater success in changing attitudes and in a small number of studies behaviour. Further to these characteristics, several strategies were identified that appear to enhance intervention impact which are discussed further in the next section.

3.6. Theory of change

One aim of this review was to draw out common theory and practice in order to strengthen future intervention development and delivery. Across all included studies, the implicit theory of change was raising knowledge/awareness for the purposes of shifting attitudes relating to gender norms and/or stereotypes. Direct participant education-based interventions was the predominant method of delivery. In addition to this, 23 (32%) studies attempted to take this a step further to address behaviour and/or behavioural intentions, of which 10 looked at gender equality outcomes (including bystander action and behavioural intentions), whilst the remaining studies focused on gender-based violence (n = 9), sexual and reproductive health (n = 2) and two studies which did not focus on behaviours related to the focus of this review.

As highlighted in Figure 2 , this common theory of change was the same across all identified intervention categories, irrespective of the overarching focus of the study (gender equality, prevention of violence, sexual and reproductive health, mental health and wellbeing). Those examining gender equality more broadly did so in relation to female empowerment in relationships, communities and political participation, identifying and addressing stereotypes and normative attitudes with kindergarten and school aged children. Those considering prevention of violence did so specifically in relation to violence against women, including intimate partner violence, rape awareness and myths, and a number of studies looking at teen dating violence. Sexual and reproductive health studies primarily assessed prevention of HIV, but also men and women's involvement in family planning, with several exploring the interconnected issues of violence and sexual and reproductive health. Finally, those studies looking at mental health and wellbeing did so in relation to mental and physical health outcomes and associated help-seeking behaviours, including reducing stigma around mental health (particularly amongst men in terms of acceptance and help seeking) and emotional expression (in relationships).

Breakdown of study characteristics and strategies associated with achieving intended outcomes.

In addition to the implicit theory of change, the review process identified five additional strategies that appear to have strengthened interventions (regardless of intervention type). In addition to implicit theory of change across all studies, one or more of these strategies were utilised by 31 of the 55 studies that reported statistically significant results:

- • Addressing more than one level of the ecological framework (n = 17): which refers to different levels of personal and environmental factors, all of which influence and are influenced by each other to differing degrees [ 120 ]. The levels are categorised as individual, relational, community/organisational and societal, with the individual level being the most commonly addressed across studies in this review;

- • Peer engagement (n = 14): Using participant peers (for example people from the same geographical location, gender, life experience, etc.) to support or lead an intervention, including the use of older students to mentor younger students, or using peer interactions as part of the intervention to enhance learning. This included students putting on performances for the broader school community, facilitation of peer discussions via online platforms or face-to-face via direct participant education and group activities or assignments;

- • Use of role models and modelling of desired attitudes and/or behaviours by facilitators or persons of influence in participants' lives (n = 11);