A Step-by-Step Guide To Case Discussion

By ashi jain.

Join InsideIIM GOLD

Webinars & Workshops

- Compare B-Schools

- Free CAT Course

Take Free Mock Tests

Upskill With AltUni

CAT Study Planner

Are you comfortable in Decision Making in a given situation How aptly you analyze the situation with a logical approach How much time do you take in arriving at a decision How good are you in taking the rightful course of action

Solved Example:

Hari, the only working member of the family has been working an organization for 25 years. His job required long standing hours. One day, while working, he lost his leg in an accident. The company paid for his medical reimbursement.

Since he was a hardworking employee; the company offered him another compensatory job. He refused by saying, ‘Once a Lion, always a Lion’. As an HR, what solution would you suggest?

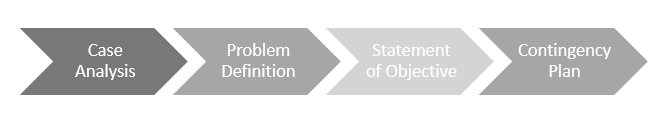

Identification of the Problem:

Obvious: accident, refusal of job, only earning member, his attitude, and inability to do his current job Hidden: the reputation of the company at stake, the course of action might influence other employees

Action Plan:

As an HR, you are first expected to check the company records and find out how a similar case has been dealt with in the past. Second, you need to take cognizance of the track record of the employee highlighted by the keyword ‘hardworking’.

Given the situation at hand, he is deemed unfit for his current role. However, the problem arises because of his attitude towards the compensatory job. Hence, in such a case, counselling is required.

Here, three levels of Counselling is required: 1. Ist level is with Hari 2. IInd level of counselling is required with the Union Leader (if any) to keep the collective interest and the reputation of the company in mind 3. IIIrd level of counselling is required with his family members as they constitute of the afflicted party

If the counselling does not work, one should also identify a contingency plan or Plan B. In this case, the Contingency Plan would be – hire someone from his family for a compensatory role.

Note that the following options are out of scope and should be avoided: 1. Increase Hari’s salary so that he gives in and agrees to do the compensatory job 2. Status Quo – do not bother as long as the Company is making a profit 3. Replace Hari with someone else

1. Pinpoint the key issues to be solved and identify their cause and effects

2. Start broad and try to work through a range of issues methodically

3. Connect the facts and evidence and focus on the big picture

4. Discuss any trade-offs or implications of your proposed solution

5. Relate your conclusion back to the problem statement and make sure you have answered all the questions

1. Do not be anxious if you are not able to understand the situation well or unable to justify the problem. Read again, a little slowly, it will help you understand better.

2. Do not jump to conclusions; try to move systematically and gradually.

3. Do not panic if you are unable to analyze the situation. Listen carefully to others as the discussion starts, it will help you gauge the problem at hand.

All the best! Ace the GDPI season.

Related Tags

FMS Delhi Summer Placements 2024: Median Stipend at 3 Lakhs

Mini Mock Test

CUET-PG Mini Mock 2 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

CUET-PG Mini Mock 3 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

CUET-PG Mini Mock 1 (By TISS Mumbai HRM&LR)

MBA Admissions 2024 - WAT 1

SNAP Quantitative Skills

SNAP Quant - 1

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 1

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 2

SNAP DILR Mini Mock - 4

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 2

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 4

SNAP LR Mini Mock - 3

SNAP Quant Mini Mock - 3

SNAP VARC Mini Mock - 3

SNAP - Quant Mini Mock 5

XAT Decision Making 2020

XAT Decision Making 2019

XAT Decision Making 2018

XAT Decision Making -10

XAT Decision Making -11

XAT Decision Making - 12

XAT Decision Making - 13

XAT Decision Making - 14

XAT Decision Making - 15

XAT Decision Making - 16

XAT Decision Making - 17

XAT Decision Making 2021

LR Topic Test

DI Topic Test

ParaSummary Topic Test

Take Free Test Here

Life of indian mba students in milan, italy - what’s next.

By InsideIIM Career Services

IMI Delhi: Worth It? | MBA ROI, Fees, Selection Process, Campus Life & More | KYC

How to calculate the real cost of an mba in 2024 ft. imt nagpur professors, mahindra university mba: worth it | campus life, academics, courses, placement | know your campus, how to uncover the reality of b-schools before joining, ft. masters' union, gmat focus edition: syllabus, exam pattern, scoring system, selection & more | new gmat exam, how to crack the jsw challenge 2023: insider tips and live q&a with industry leaders, why an xlri jamshedpur & fms delhi graduate decided to join the pharma industry, subscribe to our newsletter.

For a daily dose of the hottest, most insightful content created just for you! And don't worry - we won't spam you.

Who Are You?

Top B-Schools

Write a Story

InsideIIM Gold

InsideIIM.com is India's largest community of India's top talent that pursues or aspires to pursue a career in Management.

Follow Us Here

Konversations By InsideIIM

TestPrep By InsideIIM

- NMAT by GMAC

- Score Vs Percentile

- Exam Preparation

- Explainer Concepts

- Free Mock Tests

- RTI Data Analysis

- Selection Criteria

- CAT Toppers Interview

- Study Planner

- Admission Statistics

- Interview Experiences

- Explore B-Schools

- B-School Rankings

- Life In A B-School

- B-School Placements

- Certificate Programs

- Katalyst Programs

Placement Preparation

- Summer Placements Guide

- Final Placements Guide

Career Guide

- Career Explorer

- The Top 0.5% League

- Konversations Cafe

- The AltUni Career Show

- Employer Rankings

- Alumni Reports

- Salary Reports

Copyright 2024 - Kira9 Edumedia Pvt Ltd. All rights reserved.

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

This Is What You Need to Know to Pass Your Group Case Interview

- Last Updated January, 2024

If you’re on this page, chances are you’ve been told you’re scheduled for a group interview.

After practicing for weeks to get good at cracking a normal case interview, hearing you have a group interview might make you feel like you’ve scaled a huge mountain only to find that there’s an even higher peak beyond it that you need to climb.

Group case interviews present some different challenges than individual cases, but if you know what those challenges are, you can overcome them.

We’ll tell you how.

In this article, we’ll cover what a group case interview is, why consulting firms use them, the key to passing your group interview, and tell you the 6 tips on group interviews you need to know.

If this is your first time to MyConsultingOffer.org, you may want to start with this page on Case Interview Prep . But if you’re ready to learn everything you need to know to pass a group case, you’re in the right place.

Let’s get started!

What is a Group Case Interview?

The group needs to come to a collective point of view on what the client’s problem is, how to structure their analysis, and what the final recommendation should be.

The group should also agree on how the analysis of the case will be conducted at a high level, but the actual number-crunching will need to be divided between group members in order to complete the work in the allotted time.

The group’s analysis and recommendation will be presented to one or more interviewers.

Why Do Consulting Firms Use Group Case Interviews?

It can feel difficult to trust your team members when you know that you’re all competing for the same job, but that’s what the group case is about — it tests teamwork skills in a high-stakes environment.

Management consultants are hired to solve big, thorny business problems, ones that require the work of multiple people to solve.

While there is a hierarchy on consulting teams with a partner leading the work, consulting partners simultaneously manage multiple clients or multiple studies at one large client.

They won’t work with your team every day and in their absence, the team still needs to be able to work together effectively.

Even if a partner is leading a team’s problem-solving discussion, each consultant has a responsibility to make sure the team’s best thinking is being put forward to help the client.

Ideas are both expected from each member of the team and valued.

Even the newest analyst has a contribution to make.

T he analyst may have been the person to analyze the data and therefore be closest to the information that will drive the solution to the problem.

The flat power-structure of the team makes it critical that each consultant works well with others on teams.

In assessing each member of a group case team, interviewers will ask themselves:

Does each of the recruits listen as well as lead?

Are they open to other peoples’ ideas?

Can they perform independent analysis and interpret what impact their work has on the overall problem the team is trying to solve?

Can they persuade team members of their points of view?

The Key to Passing the Group Case: Make Sure Your Group Is Organized

A group case must be solved by going through the same 4 steps as individual cases : the opening, structuring the problem, the analysis, and the recommendation.

Your team should break down the time you have to solve the case into time allotted to each of these steps to ensure you don’t spend too long in one area and not reach a recommendation.

Make sure the team agrees on a single statement of the client’s problem.

Take the time for everyone to read the materials, take notes, and suggest what they think is the key question(s) that need to be solved in this case.

Write it on a whiteboard or somewhere else to ensure there’s agreement. You can’t solve the problem together if you don’t agree on what the problem is.

Usually, someone in the group will take the lead on organizing the group.

If no one does, this is your opportunity to demonstrate your leadership and teamwork skills, but if there are people fighting over the leadership position (unlikely since everyone is on their “best behavior”), then contribute and don’t worry that you aren’t “leading” the discussion just yet.

Create a clear, MECE structure to analyze the problem.

This is even more important to solving a group case than an individual one because you need to make sure that when the group breaks up so each member can perform part of the analysis, all the issues are covered and there’s not duplicated effort between team members.

After your group structures the problem, split up the analysis that needs to be done between members of the group.

If no one suggests breaking up the analysis, then volunteer the idea. Be sure to explain how each person’s piece fits into the team effort.

Each person should do their analysis independently to ensure there is sufficient time to complete all the required tasks, though the team should regroup briefly if someone has a problem they need help with or comes up with an insight that could influence the work other group members are doing.

While you do your own analysis, you’ll need to demonstrate you understand the bigger picture by involving your teammates, sharing how your findings impacts their work, and articulating how all the insights lead to an answer to the client’s problem.

After everyone has completed their analysis, the group should come back together so everyone can report their results and the group can collectively come to a recommendation to present to interviewers.

In addition to the normal 4 parts of the case, group cases usually require you to present your recommendation to the interviewer(s).

Be sure to build time into your schedule for creating slides, deciding who presents what, and practicing your delivery.

Many groups fail because they begin their presentation without deciding who has which role.

In consulting, this is like going into a client meeting without knowing who is presenting which slide to the client and makes your team look unprofessional.

Presentation

Start with your recommendation and then provide the key pieces of analysis and/or reasoning that support it.

Again, the work will need to be divided between team members to ensure you get slides written in the allotted time.

For more information on writing good slide presentations, see Written Case Interview page.

6 Tips to Pass Your Group Case Interview

Tip 1: organize your team.

A disorganized team will not be able to complete their analysis and develop a strong recommendation in the time allotted.

See the previous section for the steps the group needs to complete to solve the case.

If someone else does take charge, don’t fight for control.

Show leadership by making points that help to move the team’s problem solving forward, not fighting so that it goes backwards.

Tip 2: Move the Problem-Solving Forward

With multiple team members trying to contribute and express their point of view, it’s possible to have a lot of discussion without getting closer to a solution to the client’s business problem. You can overcome this by:

- Summing up what the team has agreed on so far,

- Providing insight into how the team’s discussion impacts the problem you’re tasked with solving, and/or

- Steering the team to discuss the next steps.

If it feels like the team is rehashing the same topics, use these options to move the problem solving forward.

Tip 3: Make Fact-Based Decisions

It’s okay to disagree with team members but always disagree like a consultant. Challenge teammates’ ideas with data, not opinions.

If there is analysis that needs to be done to determine which point of view is correct, table the discussion until the analysis has been completed.

Tip 4: Don't Steamroll Teammates

As mentioned earlier, consulting teams value the ideas and input of every team member.

Because of this, cutting off, interrupting or talking over other team members is more likely to get you turned down for a consulting job than hired.

The quality of your contribution to group discussions is more important than the quantity (or air time) you consume.

Demonstrate your collaboration and interpersonal skills.

Tip 5: Remain Confident When the Team Presents

Keep your poker face on even if your teammates don’t make every point the way you would have made it.

Like steamrolling teammates in discussions, frowning or shaking your head as they present will make it look like you’re not a team player.

Tip 6: Remember, Everyone Can Get Offers

In many jobs, there is only one position open.

At consulting firms, a class of new analysts and associates is hired each year.

There aren’t quotas regarding hiring only one person from a group interview team, so working cooperatively to solve the problem is a better strategy than undermining other members of your group to appear smarter than they are.

We’ve seen group interviews where no one gets a job offer and that can be because teammates undermine each other.

Don’t Over-Invest in Prepping for a Group Case Study Interview

Like the written case interview , group cases come up infrequently.

The 2 most common types of case interviews are individual interviews: the candidate-led interview or the interviewer-led interview.

In the candidate-led interview , the recruit is responsible for moving the problem solving forward. After they ensure they understand the problem and structure how they’d approach solving it, they pick one piece of the problem to start drilling down on first. Candidate-led cases are commonly used by Bain and BCG.

In the interviewer-led interview , the interviewer will suggest the first part of the case a recruit should probe after they have presented their opening and structured the problem. Interviewer-led interviews are commonly used by McKinsey .

Because individual cases are much more common than group cases, don’t spend time preparing for a group case unless you’re sure you’ll have one.

If you’re invited to take part in a group case interview, your preparation on individual cases will ensure you have a good approach cracking the case.

At this point, we hope you feel confident you can pass your group case interview.

In this article, we’ve covered what a group case interview is, why consulting firms use them, the key to passing your group interview, and the 6 tips on group interviews you need to know.

Still have questions?

If you have more questions about group interviews, leave them in the comments below. One of My Consulting Offer’s case coaches will answer them.

People prepping for a group case interview have also found the following other pages helpful:

- Case Interview Math ,

- Written Case Interview , and

- Bain One Way Interview .

Help with Case Study Interview Preparation

Thanks for turning to My Consulting Offer for advice on case study interview prep. My Consulting Offer has helped almost 85% of the people we’ve worked with get a job in management consulting. We want you to be successful in your consulting interviews too.

If you want a step-by-step solution to land more offers from consulting firms, then grab the free video training series below. It’s been created by former Bain, BCG, and McKinsey Consultants, Managers and Recruiters.

It contains the EXACT solution used by over 500 of our clients to land offers.

The best part?

It’s absolutely free. Just put your name and email address in and you’ll have instant access to the training series.

© My CONSULTING Offer

3 Top Strategies to Master the Case Interview in Under a Week

We are sharing our powerful strategies to pass the case interview even if you have no business background, zero casing experience, or only have a week to prepare.

No thanks, I don't want free strategies to get into consulting.

We are excited to invite you to the online event., where should we send you the calendar invite and login information.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A case study research paper examines a person, place, event, condition, phenomenon, or other type of subject of analysis in order to extrapolate key themes and results that help predict future trends, illuminate previously hidden issues that can be applied to practice, and/or provide a means for understanding an important research problem with greater clarity. A case study research paper usually examines a single subject of analysis, but case study papers can also be designed as a comparative investigation that shows relationships between two or more subjects. The methods used to study a case can rest within a quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-method investigative paradigm.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010 ; “What is a Case Study?” In Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London: SAGE, 2010.

How to Approach Writing a Case Study Research Paper

General information about how to choose a topic to investigate can be found under the " Choosing a Research Problem " tab in the Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper writing guide. Review this page because it may help you identify a subject of analysis that can be investigated using a case study design.

However, identifying a case to investigate involves more than choosing the research problem . A case study encompasses a problem contextualized around the application of in-depth analysis, interpretation, and discussion, often resulting in specific recommendations for action or for improving existing conditions. As Seawright and Gerring note, practical considerations such as time and access to information can influence case selection, but these issues should not be the sole factors used in describing the methodological justification for identifying a particular case to study. Given this, selecting a case includes considering the following:

- The case represents an unusual or atypical example of a research problem that requires more in-depth analysis? Cases often represent a topic that rests on the fringes of prior investigations because the case may provide new ways of understanding the research problem. For example, if the research problem is to identify strategies to improve policies that support girl's access to secondary education in predominantly Muslim nations, you could consider using Azerbaijan as a case study rather than selecting a more obvious nation in the Middle East. Doing so may reveal important new insights into recommending how governments in other predominantly Muslim nations can formulate policies that support improved access to education for girls.

- The case provides important insight or illuminate a previously hidden problem? In-depth analysis of a case can be based on the hypothesis that the case study will reveal trends or issues that have not been exposed in prior research or will reveal new and important implications for practice. For example, anecdotal evidence may suggest drug use among homeless veterans is related to their patterns of travel throughout the day. Assuming prior studies have not looked at individual travel choices as a way to study access to illicit drug use, a case study that observes a homeless veteran could reveal how issues of personal mobility choices facilitate regular access to illicit drugs. Note that it is important to conduct a thorough literature review to ensure that your assumption about the need to reveal new insights or previously hidden problems is valid and evidence-based.

- The case challenges and offers a counter-point to prevailing assumptions? Over time, research on any given topic can fall into a trap of developing assumptions based on outdated studies that are still applied to new or changing conditions or the idea that something should simply be accepted as "common sense," even though the issue has not been thoroughly tested in current practice. A case study analysis may offer an opportunity to gather evidence that challenges prevailing assumptions about a research problem and provide a new set of recommendations applied to practice that have not been tested previously. For example, perhaps there has been a long practice among scholars to apply a particular theory in explaining the relationship between two subjects of analysis. Your case could challenge this assumption by applying an innovative theoretical framework [perhaps borrowed from another discipline] to explore whether this approach offers new ways of understanding the research problem. Taking a contrarian stance is one of the most important ways that new knowledge and understanding develops from existing literature.

- The case provides an opportunity to pursue action leading to the resolution of a problem? Another way to think about choosing a case to study is to consider how the results from investigating a particular case may result in findings that reveal ways in which to resolve an existing or emerging problem. For example, studying the case of an unforeseen incident, such as a fatal accident at a railroad crossing, can reveal hidden issues that could be applied to preventative measures that contribute to reducing the chance of accidents in the future. In this example, a case study investigating the accident could lead to a better understanding of where to strategically locate additional signals at other railroad crossings so as to better warn drivers of an approaching train, particularly when visibility is hindered by heavy rain, fog, or at night.

- The case offers a new direction in future research? A case study can be used as a tool for an exploratory investigation that highlights the need for further research about the problem. A case can be used when there are few studies that help predict an outcome or that establish a clear understanding about how best to proceed in addressing a problem. For example, after conducting a thorough literature review [very important!], you discover that little research exists showing the ways in which women contribute to promoting water conservation in rural communities of east central Africa. A case study of how women contribute to saving water in a rural village of Uganda can lay the foundation for understanding the need for more thorough research that documents how women in their roles as cooks and family caregivers think about water as a valuable resource within their community. This example of a case study could also point to the need for scholars to build new theoretical frameworks around the topic [e.g., applying feminist theories of work and family to the issue of water conservation].

Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. “Building Theories from Case Study Research.” Academy of Management Review 14 (October 1989): 532-550; Emmel, Nick. Sampling and Choosing Cases in Qualitative Research: A Realist Approach . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2013; Gerring, John. “What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?” American Political Science Review 98 (May 2004): 341-354; Mills, Albert J. , Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Seawright, Jason and John Gerring. "Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research." Political Research Quarterly 61 (June 2008): 294-308.

Structure and Writing Style

The purpose of a paper in the social sciences designed around a case study is to thoroughly investigate a subject of analysis in order to reveal a new understanding about the research problem and, in so doing, contributing new knowledge to what is already known from previous studies. In applied social sciences disciplines [e.g., education, social work, public administration, etc.], case studies may also be used to reveal best practices, highlight key programs, or investigate interesting aspects of professional work.

In general, the structure of a case study research paper is not all that different from a standard college-level research paper. However, there are subtle differences you should be aware of. Here are the key elements to organizing and writing a case study research paper.

I. Introduction

As with any research paper, your introduction should serve as a roadmap for your readers to ascertain the scope and purpose of your study . The introduction to a case study research paper, however, should not only describe the research problem and its significance, but you should also succinctly describe why the case is being used and how it relates to addressing the problem. The two elements should be linked. With this in mind, a good introduction answers these four questions:

- What is being studied? Describe the research problem and describe the subject of analysis [the case] you have chosen to address the problem. Explain how they are linked and what elements of the case will help to expand knowledge and understanding about the problem.

- Why is this topic important to investigate? Describe the significance of the research problem and state why a case study design and the subject of analysis that the paper is designed around is appropriate in addressing the problem.

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study? Provide background that helps lead the reader into the more in-depth literature review to follow. If applicable, summarize prior case study research applied to the research problem and why it fails to adequately address the problem. Describe why your case will be useful. If no prior case studies have been used to address the research problem, explain why you have selected this subject of analysis.

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding? Explain why your case study will be suitable in helping to expand knowledge and understanding about the research problem.

Each of these questions should be addressed in no more than a few paragraphs. Exceptions to this can be when you are addressing a complex research problem or subject of analysis that requires more in-depth background information.

II. Literature Review

The literature review for a case study research paper is generally structured the same as it is for any college-level research paper. The difference, however, is that the literature review is focused on providing background information and enabling historical interpretation of the subject of analysis in relation to the research problem the case is intended to address . This includes synthesizing studies that help to:

- Place relevant works in the context of their contribution to understanding the case study being investigated . This would involve summarizing studies that have used a similar subject of analysis to investigate the research problem. If there is literature using the same or a very similar case to study, you need to explain why duplicating past research is important [e.g., conditions have changed; prior studies were conducted long ago, etc.].

- Describe the relationship each work has to the others under consideration that informs the reader why this case is applicable . Your literature review should include a description of any works that support using the case to investigate the research problem and the underlying research questions.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research using the case study . If applicable, review any research that has examined the research problem using a different research design. Explain how your use of a case study design may reveal new knowledge or a new perspective or that can redirect research in an important new direction.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies . This refers to synthesizing any literature that points to unresolved issues of concern about the research problem and describing how the subject of analysis that forms the case study can help resolve these existing contradictions.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research . Your review should examine any literature that lays a foundation for understanding why your case study design and the subject of analysis around which you have designed your study may reveal a new way of approaching the research problem or offer a perspective that points to the need for additional research.

- Expose any gaps that exist in the literature that the case study could help to fill . Summarize any literature that not only shows how your subject of analysis contributes to understanding the research problem, but how your case contributes to a new way of understanding the problem that prior research has failed to do.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important!] . Collectively, your literature review should always place your case study within the larger domain of prior research about the problem. The overarching purpose of reviewing pertinent literature in a case study paper is to demonstrate that you have thoroughly identified and synthesized prior studies in relation to explaining the relevance of the case in addressing the research problem.

III. Method

In this section, you explain why you selected a particular case [i.e., subject of analysis] and the strategy you used to identify and ultimately decide that your case was appropriate in addressing the research problem. The way you describe the methods used varies depending on the type of subject of analysis that constitutes your case study.

If your subject of analysis is an incident or event . In the social and behavioral sciences, the event or incident that represents the case to be studied is usually bounded by time and place, with a clear beginning and end and with an identifiable location or position relative to its surroundings. The subject of analysis can be a rare or critical event or it can focus on a typical or regular event. The purpose of studying a rare event is to illuminate new ways of thinking about the broader research problem or to test a hypothesis. Critical incident case studies must describe the method by which you identified the event and explain the process by which you determined the validity of this case to inform broader perspectives about the research problem or to reveal new findings. However, the event does not have to be a rare or uniquely significant to support new thinking about the research problem or to challenge an existing hypothesis. For example, Walo, Bull, and Breen conducted a case study to identify and evaluate the direct and indirect economic benefits and costs of a local sports event in the City of Lismore, New South Wales, Australia. The purpose of their study was to provide new insights from measuring the impact of a typical local sports event that prior studies could not measure well because they focused on large "mega-events." Whether the event is rare or not, the methods section should include an explanation of the following characteristics of the event: a) when did it take place; b) what were the underlying circumstances leading to the event; and, c) what were the consequences of the event in relation to the research problem.

If your subject of analysis is a person. Explain why you selected this particular individual to be studied and describe what experiences they have had that provide an opportunity to advance new understandings about the research problem. Mention any background about this person which might help the reader understand the significance of their experiences that make them worthy of study. This includes describing the relationships this person has had with other people, institutions, and/or events that support using them as the subject for a case study research paper. It is particularly important to differentiate the person as the subject of analysis from others and to succinctly explain how the person relates to examining the research problem [e.g., why is one politician in a particular local election used to show an increase in voter turnout from any other candidate running in the election]. Note that these issues apply to a specific group of people used as a case study unit of analysis [e.g., a classroom of students].

If your subject of analysis is a place. In general, a case study that investigates a place suggests a subject of analysis that is unique or special in some way and that this uniqueness can be used to build new understanding or knowledge about the research problem. A case study of a place must not only describe its various attributes relevant to the research problem [e.g., physical, social, historical, cultural, economic, political], but you must state the method by which you determined that this place will illuminate new understandings about the research problem. It is also important to articulate why a particular place as the case for study is being used if similar places also exist [i.e., if you are studying patterns of homeless encampments of veterans in open spaces, explain why you are studying Echo Park in Los Angeles rather than Griffith Park?]. If applicable, describe what type of human activity involving this place makes it a good choice to study [e.g., prior research suggests Echo Park has more homeless veterans].

If your subject of analysis is a phenomenon. A phenomenon refers to a fact, occurrence, or circumstance that can be studied or observed but with the cause or explanation to be in question. In this sense, a phenomenon that forms your subject of analysis can encompass anything that can be observed or presumed to exist but is not fully understood. In the social and behavioral sciences, the case usually focuses on human interaction within a complex physical, social, economic, cultural, or political system. For example, the phenomenon could be the observation that many vehicles used by ISIS fighters are small trucks with English language advertisements on them. The research problem could be that ISIS fighters are difficult to combat because they are highly mobile. The research questions could be how and by what means are these vehicles used by ISIS being supplied to the militants and how might supply lines to these vehicles be cut off? How might knowing the suppliers of these trucks reveal larger networks of collaborators and financial support? A case study of a phenomenon most often encompasses an in-depth analysis of a cause and effect that is grounded in an interactive relationship between people and their environment in some way.

NOTE: The choice of the case or set of cases to study cannot appear random. Evidence that supports the method by which you identified and chose your subject of analysis should clearly support investigation of the research problem and linked to key findings from your literature review. Be sure to cite any studies that helped you determine that the case you chose was appropriate for examining the problem.

IV. Discussion

The main elements of your discussion section are generally the same as any research paper, but centered around interpreting and drawing conclusions about the key findings from your analysis of the case study. Note that a general social sciences research paper may contain a separate section to report findings. However, in a paper designed around a case study, it is common to combine a description of the results with the discussion about their implications. The objectives of your discussion section should include the following:

Reiterate the Research Problem/State the Major Findings Briefly reiterate the research problem you are investigating and explain why the subject of analysis around which you designed the case study were used. You should then describe the findings revealed from your study of the case using direct, declarative, and succinct proclamation of the study results. Highlight any findings that were unexpected or especially profound.

Explain the Meaning of the Findings and Why They are Important Systematically explain the meaning of your case study findings and why you believe they are important. Begin this part of the section by repeating what you consider to be your most important or surprising finding first, then systematically review each finding. Be sure to thoroughly extrapolate what your analysis of the case can tell the reader about situations or conditions beyond the actual case that was studied while, at the same time, being careful not to misconstrue or conflate a finding that undermines the external validity of your conclusions.

Relate the Findings to Similar Studies No study in the social sciences is so novel or possesses such a restricted focus that it has absolutely no relation to previously published research. The discussion section should relate your case study results to those found in other studies, particularly if questions raised from prior studies served as the motivation for choosing your subject of analysis. This is important because comparing and contrasting the findings of other studies helps support the overall importance of your results and it highlights how and in what ways your case study design and the subject of analysis differs from prior research about the topic.

Consider Alternative Explanations of the Findings Remember that the purpose of social science research is to discover and not to prove. When writing the discussion section, you should carefully consider all possible explanations revealed by the case study results, rather than just those that fit your hypothesis or prior assumptions and biases. Be alert to what the in-depth analysis of the case may reveal about the research problem, including offering a contrarian perspective to what scholars have stated in prior research if that is how the findings can be interpreted from your case.

Acknowledge the Study's Limitations You can state the study's limitations in the conclusion section of your paper but describing the limitations of your subject of analysis in the discussion section provides an opportunity to identify the limitations and explain why they are not significant. This part of the discussion section should also note any unanswered questions or issues your case study could not address. More detailed information about how to document any limitations to your research can be found here .

Suggest Areas for Further Research Although your case study may offer important insights about the research problem, there are likely additional questions related to the problem that remain unanswered or findings that unexpectedly revealed themselves as a result of your in-depth analysis of the case. Be sure that the recommendations for further research are linked to the research problem and that you explain why your recommendations are valid in other contexts and based on the original assumptions of your study.

V. Conclusion

As with any research paper, you should summarize your conclusion in clear, simple language; emphasize how the findings from your case study differs from or supports prior research and why. Do not simply reiterate the discussion section. Provide a synthesis of key findings presented in the paper to show how these converge to address the research problem. If you haven't already done so in the discussion section, be sure to document the limitations of your case study and any need for further research.

The function of your paper's conclusion is to: 1) reiterate the main argument supported by the findings from your case study; 2) state clearly the context, background, and necessity of pursuing the research problem using a case study design in relation to an issue, controversy, or a gap found from reviewing the literature; and, 3) provide a place to persuasively and succinctly restate the significance of your research problem, given that the reader has now been presented with in-depth information about the topic.

Consider the following points to help ensure your conclusion is appropriate:

- If the argument or purpose of your paper is complex, you may need to summarize these points for your reader.

- If prior to your conclusion, you have not yet explained the significance of your findings or if you are proceeding inductively, use the conclusion of your paper to describe your main points and explain their significance.

- Move from a detailed to a general level of consideration of the case study's findings that returns the topic to the context provided by the introduction or within a new context that emerges from your case study findings.

Note that, depending on the discipline you are writing in or the preferences of your professor, the concluding paragraph may contain your final reflections on the evidence presented as it applies to practice or on the essay's central research problem. However, the nature of being introspective about the subject of analysis you have investigated will depend on whether you are explicitly asked to express your observations in this way.

Problems to Avoid

Overgeneralization One of the goals of a case study is to lay a foundation for understanding broader trends and issues applied to similar circumstances. However, be careful when drawing conclusions from your case study. They must be evidence-based and grounded in the results of the study; otherwise, it is merely speculation. Looking at a prior example, it would be incorrect to state that a factor in improving girls access to education in Azerbaijan and the policy implications this may have for improving access in other Muslim nations is due to girls access to social media if there is no documentary evidence from your case study to indicate this. There may be anecdotal evidence that retention rates were better for girls who were engaged with social media, but this observation would only point to the need for further research and would not be a definitive finding if this was not a part of your original research agenda.

Failure to Document Limitations No case is going to reveal all that needs to be understood about a research problem. Therefore, just as you have to clearly state the limitations of a general research study , you must describe the specific limitations inherent in the subject of analysis. For example, the case of studying how women conceptualize the need for water conservation in a village in Uganda could have limited application in other cultural contexts or in areas where fresh water from rivers or lakes is plentiful and, therefore, conservation is understood more in terms of managing access rather than preserving access to a scarce resource.

Failure to Extrapolate All Possible Implications Just as you don't want to over-generalize from your case study findings, you also have to be thorough in the consideration of all possible outcomes or recommendations derived from your findings. If you do not, your reader may question the validity of your analysis, particularly if you failed to document an obvious outcome from your case study research. For example, in the case of studying the accident at the railroad crossing to evaluate where and what types of warning signals should be located, you failed to take into consideration speed limit signage as well as warning signals. When designing your case study, be sure you have thoroughly addressed all aspects of the problem and do not leave gaps in your analysis that leave the reader questioning the results.

Case Studies. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Gerring, John. Case Study Research: Principles and Practices . New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Merriam, Sharan B. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education . Rev. ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 1998; Miller, Lisa L. “The Use of Case Studies in Law and Social Science Research.” Annual Review of Law and Social Science 14 (2018): TBD; Mills, Albert J., Gabrielle Durepos, and Eiden Wiebe, editors. Encyclopedia of Case Study Research . Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010; Putney, LeAnn Grogan. "Case Study." In Encyclopedia of Research Design , Neil J. Salkind, editor. (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2010), pp. 116-120; Simons, Helen. Case Study Research in Practice . London: SAGE Publications, 2009; Kratochwill, Thomas R. and Joel R. Levin, editors. Single-Case Research Design and Analysis: New Development for Psychology and Education . Hilldsale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1992; Swanborn, Peter G. Case Study Research: What, Why and How? London : SAGE, 2010; Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods . 6th edition. Los Angeles, CA, SAGE Publications, 2014; Walo, Maree, Adrian Bull, and Helen Breen. “Achieving Economic Benefits at Local Events: A Case Study of a Local Sports Event.” Festival Management and Event Tourism 4 (1996): 95-106.

Writing Tip

At Least Five Misconceptions about Case Study Research

Social science case studies are often perceived as limited in their ability to create new knowledge because they are not randomly selected and findings cannot be generalized to larger populations. Flyvbjerg examines five misunderstandings about case study research and systematically "corrects" each one. To quote, these are:

Misunderstanding 1 : General, theoretical [context-independent] knowledge is more valuable than concrete, practical [context-dependent] knowledge. Misunderstanding 2 : One cannot generalize on the basis of an individual case; therefore, the case study cannot contribute to scientific development. Misunderstanding 3 : The case study is most useful for generating hypotheses; that is, in the first stage of a total research process, whereas other methods are more suitable for hypotheses testing and theory building. Misunderstanding 4 : The case study contains a bias toward verification, that is, a tendency to confirm the researcher’s preconceived notions. Misunderstanding 5 : It is often difficult to summarize and develop general propositions and theories on the basis of specific case studies [p. 221].

While writing your paper, think introspectively about how you addressed these misconceptions because to do so can help you strengthen the validity and reliability of your research by clarifying issues of case selection, the testing and challenging of existing assumptions, the interpretation of key findings, and the summation of case outcomes. Think of a case study research paper as a complete, in-depth narrative about the specific properties and key characteristics of your subject of analysis applied to the research problem.

Flyvbjerg, Bent. “Five Misunderstandings About Case-Study Research.” Qualitative Inquiry 12 (April 2006): 219-245.

- << Previous: Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Next: Writing a Field Report >>

- Last Updated: Jun 3, 2024 9:44 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

The Discussion Group Experience

Leadership Insights Blog

Overview dropdown up, overview dropdown down, benefits expand all collapse all, gain a better understanding of the case materials gain a better understanding of the case materials dropdown down, practice teaching and learning from others practice teaching and learning from others dropdown down, "test-market" ideas and opinions before class "test-market" ideas and opinions before class dropdown down, get to know a handful of people more deeply get to know a handful of people more deeply dropdown down, benefits dropdown up, benefits dropdown down, gain a better understanding of the case materials, practice teaching and learning from others, "test-market" ideas and opinions before class, get to know a handful of people more deeply, best practices expand all collapse all, designate one discussion leader designate one discussion leader dropdown down, ensure 100 percent attendance ensure 100 percent attendance dropdown down, expect 100 percent participation expect 100 percent participation dropdown down, encourage challenging viewpoints encourage challenging viewpoints dropdown down, stay focused and use time wisely stay focused and use time wisely dropdown down, accept responsibility to learn and teach accept responsibility to learn and teach dropdown down, best practices dropdown up, best practices dropdown down, designate one discussion leader, ensure 100 percent attendance, expect 100 percent participation, encourage challenging viewpoints, stay focused and use time wisely, accept responsibility to learn and teach, what can i expect on the first day dropdown down.

Most programs begin with registration, followed by an opening session and a dinner. If your travel plans necessitate late arrival, please be sure to notify us so that alternate registration arrangements can be made for you. Please note the following about registration:

HBS campus programs – Registration takes place in the Chao Center.

India programs – Registration takes place outside the classroom.

Other off-campus programs – Registration takes place in the designated facility.

What happens in class if nobody talks? Dropdown down

Professors are here to push everyone to learn, but not to embarrass anyone. If the class is quiet, they'll often ask a participant with experience in the industry in which the case is set to speak first. This is done well in advance so that person can come to class prepared to share. Trust the process. The more open you are, the more willing you’ll be to engage, and the more alive the classroom will become.

Does everyone take part in "role-playing"? Dropdown down

Professors often encourage participants to take opposing sides and then debate the issues, often taking the perspective of the case protagonists or key decision makers in the case.

View Frequently Asked Questions

Subscribe to Our Emails

- Utility Menu

GA4 tagging code

- Demonstrating Moves Live

- Raw Clips Library

- Facilitation Guide

Structuring the Case Discussion

Well-designed cases are intentionally complex. Therefore, presenting an entire case to students all at once has the potential to overwhelm student groups and lead them to overlook key details or analytic steps. Accordingly, Barbara Cockrill asks students to review key case concepts the night before, and then presents the case in digestible “chunks” during a CBCL session. Structuring the case discussion around key in-depth questions, Cockrill creates a thoughtful interplay between small group work and whole group discussion that makes for more systematic forays into the case at hand.

Barbara Cockrill , Harold Amos Academy Associate Professor of Medicine

Student Group

Harvard Medical School

Homeostasis I

40 students

Additional Details

First-year requisite

- Classroom Considerations

- Relevant Research

- Related Resources

- CBCL provides students the opportunity to apply course material in new ways. For this reason, you might consider not sharing the case with students beforehand and having them experience it in class with fresh eyes.

- Chunk cases so students can focus on case specifics and gradually build-up to greater complexity and understanding.

- Introduce variety into case-based discussions. Integrate a mix of independent work, small group discussion, and whole group share outs to keep students engaged and provide multiple junctures for students to get feedback on their understanding.

- Instructor scaffolding is critical for effective case-based learning ( Ramaekers et al., 2011 )

- This resource from the Harvard Business School provides suggestions for questioning, listening, and responding during a case discussion .

- This comprehensive resource on “The ABCs of Case Teaching” provides helpful tips for planning and “running” your case .

Related Moves

Experiencing the Case as a Student Team

Regulating the Flow of Energy in the Classroom

Designing Focused Discussions for Relevance and Transfer of Knowledge

Search form

- Table of Contents

- Troubleshooting Guide

- A Model for Getting Started

- Justice Action Toolkit

- Best Change Processes

- Databases of Best Practices

- Online Courses

- Ask an Advisor

- Subscribe to eNewsletter

- Community Stories

- YouTube Channel

- About the Tool Box

- How to Use the Tool Box

- Privacy Statement

- Workstation/Check Box Sign-In

- Online Training Courses

- Capacity Building Training

- Training Curriculum - Order Now

- Community Check Box Evaluation System

- Build Your Toolbox

- Facilitation of Community Processes

- Community Health Assessment and Planning

- Section 4. Techniques for Leading Group Discussions

Chapter 16 Sections

- Section 1. Conducting Effective Meetings

- Section 2. Developing Facilitation Skills

- Section 3. Capturing What People Say: Tips for Recording a Meeting

- Main Section

A local coalition forms a task force to address the rising HIV rate among teens in the community. A group of parents meets to wrestle with their feeling that their school district is shortchanging its students. A college class in human services approaches the topic of dealing with reluctant participants. Members of an environmental group attend a workshop on the effects of global warming. A politician convenes a “town hall meeting” of constituents to brainstorm ideas for the economic development of the region. A community health educator facilitates a smoking cessation support group.

All of these might be examples of group discussions, although they have different purposes, take place in different locations, and probably run in different ways. Group discussions are common in a democratic society, and, as a community builder, it’s more than likely that you have been and will continue to be involved in many of them. You also may be in a position to lead one, and that’s what this section is about. In this last section of a chapter on group facilitation, we’ll examine what it takes to lead a discussion group well, and how you can go about doing it.

What is an effective group discussion?

The literal definition of a group discussion is obvious: a critical conversation about a particular topic, or perhaps a range of topics, conducted in a group of a size that allows participation by all members. A group of two or three generally doesn’t need a leader to have a good discussion, but once the number reaches five or six, a leader or facilitator can often be helpful. When the group numbers eight or more, a leader or facilitator, whether formal or informal, is almost always helpful in ensuring an effective discussion.

A group discussion is a type of meeting, but it differs from the formal meetings in a number of ways: It may not have a specific goal – many group discussions are just that: a group kicking around ideas on a particular topic. That may lead to a goal ultimately...but it may not. It’s less formal, and may have no time constraints, or structured order, or agenda. Its leadership is usually less directive than that of a meeting. It emphasizes process (the consideration of ideas) over product (specific tasks to be accomplished within the confines of the meeting itself. Leading a discussion group is not the same as running a meeting. It’s much closer to acting as a facilitator, but not exactly the same as that either.

An effective group discussion generally has a number of elements:

- All members of the group have a chance to speak, expressing their own ideas and feelings freely, and to pursue and finish out their thoughts

- All members of the group can hear others’ ideas and feelings stated openly

- Group members can safely test out ideas that are not yet fully formed

- Group members can receive and respond to respectful but honest and constructive feedback. Feedback could be positive, negative, or merely clarifying or correcting factual questions or errors, but is in all cases delivered respectfully.

- A variety of points of view are put forward and discussed

- The discussion is not dominated by any one person

- Arguments, while they may be spirited, are based on the content of ideas and opinions, not on personalities

- Even in disagreement, there’s an understanding that the group is working together to resolve a dispute, solve a problem, create a plan, make a decision, find principles all can agree on, or come to a conclusion from which it can move on to further discussion

Many group discussions have no specific purpose except the exchange of ideas and opinions. Ultimately, an effective group discussion is one in which many different ideas and viewpoints are heard and considered. This allows the group to accomplish its purpose if it has one, or to establish a basis either for ongoing discussion or for further contact and collaboration among its members.

There are many possible purposes for a group discussion, such as:

- Create a new situation – form a coalition, start an initiative, etc.

- Explore cooperative or collaborative arrangements among groups or organizations

- Discuss and/or analyze an issue, with no specific goal in mind but understanding

- Create a strategic plan – for an initiative, an advocacy campaign, an intervention, etc.

- Discuss policy and policy change

- Air concerns and differences among individuals or groups

- Hold public hearings on proposed laws or regulations, development, etc.

- Decide on an action

- Provide mutual support

- Solve a problem

- Resolve a conflict

- Plan your work or an event

Possible leadership styles of a group discussion also vary. A group leader or facilitator might be directive or non-directive; that is, she might try to control what goes on to a large extent; or she might assume that the group should be in control, and that her job is to facilitate the process. In most group discussions, leaders who are relatively non-directive make for a more broad-ranging outlay of ideas, and a more satisfying experience for participants.

Directive leaders can be necessary in some situations. If a goal must be reached in a short time period, a directive leader might help to keep the group focused. If the situation is particularly difficult, a directive leader might be needed to keep control of the discussion and make

Why would you lead a group discussion?

There are two ways to look at this question: “What’s the point of group discussion?” and “Why would you, as opposed to someone else, lead a group discussion?” Let’s examine both.

What’s the point of group discussion?

As explained in the opening paragraphs of this section, group discussions are common in a democratic society. There are a number of reasons for this, some practical and some philosophical.

A group discussion:

- G ives everyone involved a voice . Whether the discussion is meant to form a basis for action, or just to play with ideas, it gives all members of the group a chance to speak their opinions, to agree or disagree with others, and to have their thoughts heard. In many community-building situations, the members of the group might be chosen specifically because they represent a cross-section of the community, or a diversity of points of view.

- Allows for a variety of ideas to be expressed and discussed . A group is much more likely to come to a good conclusion if a mix of ideas is on the table, and if all members have the opportunity to think about and respond to them.

- Is generally a democratic, egalitarian process . It reflects the ideals of most grassroots and community groups, and encourages a diversity of views.

- Leads to group ownership of whatever conclusions, plans, or action the group decides upon . Because everyone has a chance to contribute to the discussion and to be heard, the final result feels like it was arrived at by and belongs to everyone.

- Encourages those who might normally be reluctant to speak their minds . Often, quiet people have important things to contribute, but aren’t assertive enough to make themselves heard. A good group discussion will bring them out and support them.

- Can often open communication channels among people who might not communicate in any other way . People from very different backgrounds, from opposite ends of the political spectrum, from different cultures, who may, under most circumstances, either never make contact or never trust one another enough to try to communicate, might, in a group discussion, find more common ground than they expected.

- Is sometimes simply the obvious, or even the only, way to proceed. Several of the examples given at the beginning of the section – the group of parents concerned about their school system, for instance, or the college class – fall into this category, as do public hearings and similar gatherings.

Why would you specifically lead a group discussion?

You might choose to lead a group discussion, or you might find yourself drafted for the task. Some of the most common reasons that you might be in that situation:

- It’s part of your job . As a mental health counselor, a youth worker, a coalition coordinator, a teacher, the president of a board of directors, etc. you might be expected to lead group discussions regularly.

- You’ve been asked to . Because of your reputation for objectivity or integrity, because of your position in the community, or because of your skill at leading group discussions, you might be the obvious choice to lead a particular discussion.

- A discussion is necessary, and you’re the logical choice to lead it . If you’re the chair of a task force to address substance use in the community, for instance, it’s likely that you’ll be expected to conduct that task force’s meetings, and to lead discussion of the issue.

- It was your idea in the first place . The group discussion, or its purpose, was your idea, and the organization of the process falls to you.

You might find yourself in one of these situations if you fall into one of the categories of people who are often tapped to lead group discussions. These categories include (but aren’t limited to):

- Directors of organizations

- Public officials

- Coalition coordinators

- Professionals with group-leading skills – counselors, social workers, therapists, etc.

- Health professionals and health educators

- Respected community members. These folks may be respected for their leadership – president of the Rotary Club, spokesperson for an environmental movement – for their positions in the community – bank president, clergyman – or simply for their personal qualities – integrity, fairness, ability to communicate with all sectors of the community.

- Community activists. This category could include anyone from “professional” community organizers to average citizens who care about an issue or have an idea they want to pursue.

When might you lead a group discussion?

The need or desire for a group discussion might of course arise anytime, but there are some times when it’s particularly necessary.

- At the start of something new . Whether you’re designing an intervention, starting an initiative, creating a new program, building a coalition, or embarking on an advocacy or other campaign, inclusive discussion is likely to be crucial in generating the best possible plan, and creating community support for and ownership of it.

- When an issue can no longer be ignored . When youth violence reaches a critical point, when the community’s drinking water is declared unsafe, when the HIV infection rate climbs – these are times when groups need to convene to discuss the issue and develop action plans to swing the pendulum in the other direction.

- When groups need to be brought together . One way to deal with racial or ethnic hostility, for instance, is to convene groups made up of representatives of all the factions involved. The resulting discussions – and the opportunity for people from different backgrounds to make personal connections with one another – can go far to address everyone’s concerns, and to reduce tensions.

- When an existing group is considering its next step or seeking to address an issue of importance to it . The staff of a community service organization, for instance, may want to plan its work for the next few months, or to work out how to deal with people with particular quirks or problems.

How do you lead a group discussion?

In some cases, the opportunity to lead a group discussion can arise on the spur of the moment; in others, it’s a more formal arrangement, planned and expected. In the latter case, you may have the chance to choose a space and otherwise structure the situation. In less formal circumstances, you’ll have to make the best of existing conditions.

We’ll begin by looking at what you might consider if you have time to prepare. Then we’ll examine what it takes to make an effective discussion leader or facilitator, regardless of external circumstances.

Set the stage

If you have time to prepare beforehand, there are a number of things you may be able to do to make the participants more comfortable, and thus to make discussion easier.

Choose the space

If you have the luxury of choosing your space, you might look for someplace that’s comfortable and informal. Usually, that means comfortable furniture that can be moved around (so that, for instance, the group can form a circle, allowing everyone to see and hear everyone else easily). It may also mean a space away from the ordinary.

One organization often held discussions on the terrace of an old mill that had been turned into a bookstore and café. The sound of water from the mill stream rushing by put everyone at ease, and encouraged creative thought.

Provide food and drink

The ultimate comfort, and one that breaks down barriers among people, is that of eating and drinking.

Bring materials to help the discussion along

Most discussions are aided by the use of newsprint and markers to record ideas, for example.

Become familiar with the purpose and content of the discussion

If you have the opportunity, learn as much as possible about the topic under discussion. This is not meant to make you the expert, but rather to allow you to ask good questions that will help the group generate ideas.

Make sure everyone gets any necessary information, readings, or other material beforehand

If participants are asked to read something, consider questions, complete a task, or otherwise prepare for the discussion, make sure that the assignment is attended to and used. Don’t ask people to do something, and then ignore it.

Lead the discussion

Think about leadership style

The first thing you need to think about is leadership style, which we mentioned briefly earlier in the section. Are you a directive or non-directive leader? The chances are that, like most of us, you fall somewhere in between the extremes of the leader who sets the agenda and dominates the group completely, and the leader who essentially leads not at all. The point is made that many good group or meeting leaders are, in fact, facilitators, whose main concern is supporting and maintaining the process of the group’s work. This is particularly true when it comes to group discussion, where the process is, in fact, the purpose of the group’s coming together.

A good facilitator helps the group set rules for itself, makes sure that everyone participates and that no one dominates, encourages the development and expression of all ideas, including “odd” ones, and safeguards an open process, where there are no foregone conclusions and everyone’s ideas are respected. Facilitators are non-directive, and try to keep themselves out of the discussion, except to ask questions or make statements that advance it. For most group discussions, the facilitator role is probably a good ideal to strive for.

It’s important to think about what you’re most comfortable with philosophically, and how that fits what you’re comfortable with personally. If you’re committed to a non-directive style, but you tend to want to control everything in a situation, you may have to learn some new behaviors in order to act on your beliefs.

Put people at ease

Especially if most people in the group don’t know one another, it’s your job as leader to establish a comfortable atmosphere and set the tone for the discussion.

Help the group establish ground rules

The ground rules of a group discussion are the guidelines that help to keep the discussion on track, and prevent it from deteriorating into namecalling or simply argument. Some you might suggest, if the group has trouble coming up with the first one or two:

- Everyone should treat everyone else with respect : no name-calling, no emotional outbursts, no accusations.

- No arguments directed at people – only at ideas and opinions . Disagreement should be respectful – no ridicule.

- Don’t interrupt . Listen to the whole of others’ thoughts – actually listen, rather than just running over your own response in your head.

- Respect the group’s time . Try to keep your comments reasonably short and to the point, so that others have a chance to respond.

- Consider all comments seriously, and try to evaluate them fairly . Others’ ideas and comments may change your mind, or vice versa: it’s important to be open to that.

- Don’t be defensive if someone disagrees with you . Evaluate both positions, and only continue to argue for yours if you continue to believe it’s right.

- Everyone is responsible for following and upholding the ground rules .

Ground rules may also be a place to discuss recording the session. Who will take notes, record important points, questions for further discussion, areas of agreement or disagreement? If the recorder is a group member, the group and/or leader should come up with a strategy that allows her to participate fully in the discussion.

Generate an agenda or goals for the session

You might present an agenda for approval, and change it as the group requires, or you and the group can create one together. There may actually be no need for one, in that the goal may simply be to discuss an issue or idea. If that’s the case, it should be agreed upon at the outset.

How active you are might depend on your leadership style, but you definitely have some responsibilities here. They include setting, or helping the group to set the discussion topic; fostering the open process; involving all participants; asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion; summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, and ideas; and wrapping up the session. Let’s look at these, as well as some do’s and don’t’s for discussion group leaders.

- Setting the topic . If the group is meeting to discuss a specific issue or to plan something, the discussion topic is already set. If the topic is unclear, then someone needs to help the group define it. The leader – through asking the right questions, defining the problem, and encouraging ideas from the group – can play that role.

- Fostering the open process . Nurturing the open process means paying attention to the process, content, and interpersonal dynamics of the discussion all at the same time – not a simple matter. As leader, your task is not to tell the group what to do, or to force particular conclusions, but rather to make sure that the group chooses an appropriate topic that meets its needs, that there are no “right” answers to start with (no foregone conclusions), that no one person or small group dominates the discussion, that everyone follows the ground rules, that discussion is civil and organized, and that all ideas are subjected to careful critical analysis. You might comment on the process of the discussion or on interpersonal issues when it seems helpful (“We all seem to be picking on John here – what’s going on?”), or make reference to the open process itself (“We seem to be assuming that we’re supposed to believe X – is that true?”). Most of your actions as leader should be in the service of modeling or furthering the open process.

Part of your job here is to protect “minority rights,” i.e., unpopular or unusual ideas. That doesn’t mean you have to agree with them, but that you have to make sure that they can be expressed, and that discussion of them is respectful, even in disagreement. (The exceptions are opinions or ideas that are discriminatory or downright false.) Odd ideas often turn out to be correct, and shouldn’t be stifled.

- Involving all participants . This is part of fostering the open process, but is important enough to deserve its own mention. To involve those who are less assertive or shy, or who simply can’t speak up quickly enough, you might ask directly for their opinion, encourage them with body language (smile when they say anything, lean and look toward them often), and be aware of when they want to speak and can’t break in. It’s important both for process and for the exchange of ideas that everyone have plenty of opportunity to communicate their thoughts.

- Asking questions or offering ideas to advance the discussion . The leader should be aware of the progress of the discussion, and should be able to ask questions or provide information or arguments that stimulate thinking or take the discussion to the next step when necessary. If participants are having trouble grappling with the topic, getting sidetracked by trivial issues, or simply running out of steam, it’s the leader’s job to carry the discussion forward.

This is especially true when the group is stuck, either because two opposing ideas or factions are at an impasse, or because no one is able or willing to say anything. In these circumstances, the leader’s ability to identify points of agreement, or to ask the question that will get discussion moving again is crucial to the group’s effectiveness.

- Summarizing or clarifying important points, arguments, or ideas . This task entails making sure that everyone understands a point that was just made, or the two sides of an argument. It can include restating a conclusion the group has reached, or clarifying a particular idea or point made by an individual (“What I think I heard you say was…”). The point is to make sure that everyone understands what the individual or group actually meant.