- Practitioner

- EBP Monthly

- EBP Quarterly

- Event Updates

- Continued Education

- Conferences

- Frontline Pathway

- Leadership Pathway

- MI Skills Day

- Supervisors

- Faculty Guidelines

- Joyfields Institute

- Request Demo

- Masterclasses

- Schedule-A-Mentor

- Login/Sign In

An Overview of Recent National and International Research on the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility

Kelly orts, university of new haven .

What is a child? There is worldwide variation in how a "child" is defined differently from an "adult." The factors taken into consideration when creating this definition differ even further (Morgan, 2010). The varying cultures, societal norms, histories, economies, and political climates create challenges to establishing a globally accepted juvenile justice system. There is a societal understanding that children differ from adults and should, therefore, receive different and separate treatment (Morgan, 2010). Juvenile justice systems, child welfare systems, and other protective services for youth were created on the basis that children lack the maturity, rights, responsibility, and capacity of adults. The common goal in addressing youthful behavior is for systems to focus on rehabilitating and supporting the child and his or her family. With this in mind, the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) and the age of criminal majority (ACM) set the boundaries of entry into the juvenile justice system.

The minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) refers to the youngest age at which an individual can be processed formally in the justice system. Although using chronological age may seem as simple as identifying a number, determining this number is much more complex. Factors such as brain development, competency, and childhood experiences may influence whether a child is diverted from or handled within the justice system. Legal concepts around the MACR help assess an individual's mental wellness, cognitive ability, and developmental maturity (Abrams et al., 2019a). Similarly, “mental capacity” is a term used to refer to an individual's cognitive ability to understand right from wrong, and “ doli incapax” is a Latin term referring to the presumption of incapacity of an individual to commit a crime.

Much attention is also placed on the ACM, due to a greater number of crimes committed by teenagers (rather than young children) and the debate surrounding transferring teenagers to the adult system. Unfortunately, there is relatively little research or concern placed on the MACR, despite it being equally significant to a child's future. The purpose of this paper is to provide a national and international landscape of the MACR, as well as to review current trends in legislation, research studies, public perceptions, and possible alternative handling. Research shows many potential consequences for children who are processed formally in the juvenile justice system, including future involvement in the system as adults, interruption in school, separation from family, and harm to their physical and mental health (Abrams et al., 2019a). By understanding the context in which various juvenile justice jurisdictions stand, amongst the relevant research, societal trends, and reform efforts, we can look toward future policies and research studies that can further address the needs of our youth.

Juvenile Justice Evolution

In 1899, the first U.S. juvenile court was established based on the idea that children are more amendable to growth and change, and therefore they should be considered less responsible and less culpable as compared to adults (Abrams et al., 2019a). Since then, all American states have created separate juvenile systems that moved away from a punitive approach and toward a more rehabilitative strategy.

The United States does not have a federally established MACR and allows states to determine if they would like to set one and specify what that MACR should be. Currently, 22 states have established a MACR between 6 and 11 years of age (Abrams et al., 2019a). Nebraska recently established a new MACR of 11 in 2017, and Massachusetts raised their MACR from 7 to 12 in 2018. California did not have an established MACR, but recently passed a bill that will implement a MACR of 12 years of age, joining Massachusetts as the highest MACR in the country and the only American jurisdictions meeting international standards set forth by the United Nations (Abrams et al., 2019b). In 2016, there were more than 30,000 children who were referred to the juvenile court while under the age of 12 (Abrams et al., 2019a). Although this population is small, the MACR controls the identification of children eligible to be prosecuted in court.

Child advocates emphasize the value of a higher MACR and use of diversion programs to avoid the lifelong consequences produced by experiencing the juvenile justice system. Others have argued, however, that a lower MACR would allow for earlier identification and intervention for delinquent juveniles, and the ability to connect them to appropriate services (Abrams, Jordan, & Montero, 2018).

The United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) brought forth an international perspective on a developmentally appropriate MACR. The committee indicated that any MACR under 12 years was unacceptable (Abrams, Jordan, Montero, 2018). Since this UNCRC recommendation was produced, 40 countries either have established or increased their MACR to meet this standard and remain accountable through reporting to the UNCRC. In contrast, other countries, such as France, Denmark, and Brazil, have lowered their MACR in adherence to the UNCRC recommendation. Perhaps not surprisingly, the UNCRC continues to investigate increasing their MACR recommendation.

Historically, legislation has shifted to (or from) rehabilitative reform, to reflect the country’s specific political climate, public perception, and societal values at the time. Argentinian legislation in 1980 established a MACR of 16 and presumes anyone under that age to lack criminal intent (Abrams et al., 2018). The Crime Control and Criminal Justice Act of 1994 in Belize allows for the imprisonment of anyone older than 10, but assumes a lack of criminal capacity for those under 10 (Abrams et al., 2018). In Finland, a MACR of 15 has remained consistent for almost a century, with a recent push for increased community sanctions and supervision of juveniles (Abrams et al., 2018).

Finally, case law in America not directly changing the MACR but affecting the same population includes Dusky v. United States (1960), which established a requirement for all criminal defendants to have a basic understanding of legal proceedings, and In re Gault (1967), which ensured juveniles a right to a fair trial. Additionally, some states have recently removed status offenses from the juvenile court system, which immediately diverts truant children or runaways to other systems and services (Abrams et al., 2019a).

Previous Research Findings

Research on the MACR historically focused on evaluating the impact of juvenile justice reforms and legislation. For example, South Africa’s Child Justice Act of 2008 extended the Constitution of the Republic in order to serve the best interests of their youth and create a justice system more appropriate and rehabilitative for children. This act set the MACR at 10 years, with a stipulation to review this act in 5 years to assess its progress and impact (Schloeman, 2016). The results found by Schloeman (2016) reflected an increase in capacity evaluations of youth, but also a delay in case processing, overburdening of mental health professionals, and an increase in costs.

Other research in the United Kingdom focused on highly publicized violent crimes committed by youth and their influence on legislation. Delmage (2013) explained how the murder of James Burgler by two 10-year-old boys in 1993 led to the abolishment of doli incapax in the U.K., through the Crime and Disorder Act of 1998. Due to this legislation, the following year there was a 29% increase in 10-14 year olds involved in court (Goldson, 2013). The conviction of these two boys led to a publicly and politically supported movement towards punitive reform, which also included the Powers of Criminal Courts Sentencing Act in 2000, allowing for children under 18 and convicted of murder to be held for an indeterminate amount of time “at Her Majesty's Pleasure” (Abrams et al., 2018).

Previous research on measuring criminality depended greatly on the research areas of developmental psychology, social learning, and cognitive maturity (Morgan, 2010). For example, a study by Wagland and Bussey (2017) assessed the ability to appreciate wrongfulness of criminal conduct among individuals of various ages, including 8, 12, 16, and those in adulthood. The results showed that even the youngest individuals in the study were able to understand the wrongfulness of criminal behavior and identify reasons as to why it was wrong. Other relevant research referenced by the authors showed individuals as young as 3 years old to have a developed sense of wrongfulness.

Recently, there has been relatively little research focused specially on the MACR in relation to national and international jurisdictions. Within the past two years, however, three empirical studies published on the MACR were conducted by Abrams and associates (Abrams et al., 2018; 2019a; 2019b). The limited number of recent MACR studies may indicate the lack of care and consideration the younger juvenile population has received in comparison to the larger teenage population.

Current Research Findings

The contemporary research conducted by Abrams and colleagues, between the years of 2018 and 2019, provided a deeper dive into the juvenile justice system and minimum age boundaries in the United States and the rest of the world. To begin, Abrams and colleagues (2019a) completed a comparative study on the major metropolitan regions within the six largest states in America, California, Texas, New York, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Illinois. Separately, Abrams et al. (2019b) specifically focused on California, due to the recent bill proposal of establishing a MACR of 12 years. This study selected three California counties that would provide variety in geography, demographics, poverty rate, and population. Similarly, Abrams and associates (2018) previously hand-selected four different countries, varying in age boundaries, poverty, education, population, size, culture, legal systems, and crime rates, which included Belize, Finland, Argentina, and England/Wales. This allowed for a cross-national comparison of how a “child” is defined, handled, and advocated for.

All three studies included a legal analysis of the justice system, its age boundaries, and effectiveness. The two studies completed in the U.S. also used semi-structured telephone interviews with criminal justice professionals, ranging from juvenile court judges, juvenile public defenders, probation, police, and district attorneys. Interviews were recorded and coded into specific themes, such as implementation challenges, perceptions of effectiveness, and local practices. Questions to the stakeholders focused on examining their perception of the MACR, competency practices, capacity practices, and effectiveness.

The legal analysis used an online database to pull laws and statutes for each jurisdiction relating to juveniles, capacity, competency, and diversionary alternatives. Juvenile crime data focused on juvenile arrests, bookings, and referrals. Abrams and associates (2018) also reviewed reports from global and regional organizations to supplement their analysis. By gathering this information, the combined research by Abrams and colleagues (2018, 2019a, 2019b) sought to create a larger timeline and scope of juvenile justice trends, structure, function, effectiveness, and practices surrounding the lower age statute.

In the six largest U.S. states, justice-involved youth under 12 made up 1-3% of their juvenile justice population (Abrams et al., 2019a). Generally, this rate is on the decline across the country and follows a similar international trend of very low juvenile involvement for young children (Abrams et al, 2018). Specifically, in California, this young population was referred largely for status offenses or misdemeanors, and there was also an overrepresentation of African American children (Abrams et al., 2019b).

Juvenile Justice Jurisdictions

In the most recent analyses of Abrams et al. (2019a; 2019b), there were hard boundaries (e.g., age restrictions), soft boundaries (e.g., discretionary decisions), and local practices within the U.S. states that guided juvenile case processing. In states without a MACR, other related practices, such as Illinois' minimum age for detention, would serve as an informal threshold into the juvenile justice system. States are also allowed to determine their own guidelines and utilize assessment tools to determine a defendant’s capacity and competency.

In Texas, where the MACR is 10, competency is required for the proceedings to continue. If a child does not exemplify an understanding of their rights or the legal process, the court can order the child to a facility for 90 days, to be taught this information and be reassessed. Similarly, Florida will pause a trial for up to two years to reassess a child’s competency every six months, until moving forward. In New York, where the MACR is 7 years, judges hold the decision-making responsibility on a defendant's competency, which contrasts with other states that have a trained professional complete the assessment. Abrams et al. (2019b) also found that current juvenile justice legislation in California was unevenly implemented throughout the state, largely due to the freedom each of the 58 counties has in creating their own protocols, such as capacity and competency guidelines. Although these types of guidelines intend to protect children from inappropriate processing, the threshold for meeting competency standards is very low and typically is met easily through the state’s assessment tool, the Gladys R. questionnaire.

Like the United States, many other countries use specific courts and capacity/competency procedures to handle juveniles. In England/Wales, there are specific youth courts with a Youth Justice Board that provide probationary services and supervision for all justice-involved youth. These specialized courts can send youth under 15 to state-run homes, or those over 15 to secure Young Offender Institutions (Abrams et al., 2018).

In Belize, youth may be processed in family court, juvenile court, municipal court, or the Supreme Court, depending on the circumstance. Despite the separation of systems, the housing facilities present a conflict, as children can be sent to the same wards as adults. Out of the four international countries examined, Belize was the smallest and least developed, with high incarceration, homicide, and poverty rates (Abrams et al., 2018). There is also a large population of teenagers and young adults, which may contribute to these crime statistics. When conducting the legal analysis, Abrams et al. (2018) found conflicting MACR between ages 9 (as stated in the Crime Control and Criminal Justice Act), 10 (as stated in the Criminal Code), and 12 (as mandated under international law of the UNCRC). This may lead to an increase in disparities and unfair sentencing across the country.

Finland and Argentina are examples of countries without a separate court system, but with a high MACR. This high MACR proves effective in reducing juvenile incarceration, as both countries have relatively low rates in comparison to other counties of similar size and population. In Finland, 15-17-year olds are sent to municipal, child welfare, appellate, or supreme court, and are only subject to a quarter of what the equivalent adult sentence would be for the convicted crime. These determinate sentences are different than in Argentina, where youth from 16-17 are handled similarly to adults and face similar sentences, but are housed separately. In 2009, a bill was proposed to lower the Argentinian MACR to 14, to deter more young people and provide earlier intervention services. However, the bill did not pass.

Perspectives of Youth Justice Professionals

In all three studies, youth justice professionals were interviewed to solicit their feedback on the effectiveness, implementation, and opinion of the juvenile justice system and minimum age boundaries. In relation to capacity assessments, youth justice professionals in Abrams et al. (2019b) emphasized the flaws in the Gladys R. assessment, such as a lack of data collection, notification, training, and parental awareness. In regards to competency assessments, both public defenders and district attorneys stated they were more likely to look for a plea deal in order to avoid the lengthy competency restoration process. When considering the new California MACR, interviewees who were in support of raising the minimum age stated it was a necessary protection for youth, especially with regard to capacity and competency assessments. They also cited the potential cost savings and reduction in racial disparities among youth. Those who expressed opposition to the MACR increase were concerned politicians and legislators were not the appropriate decision-makers for this legislation, due to their lack of expertise and involvement on the ground.

In New York, interviews with youth justice professionals by Abrams et al. (2019a) showed a general agreement that the legal MACR of 7 was not realistically followed, and most juvenile case processing utilized an informal boundary around 10 years old. These professionals also explained that the movement to raise the age from 7 years has been greatly opposed by policymakers. In the same study, Texas youth justice professionals agreed that the state's MACR of 10 was effective in keeping young children out of the formal court processes. There was also an agreement among the interviewees that the competency assessments were unfair and designed to either find a child competent or require a great deal of time and money be spent until the child is found competent to stand trial.

Alternatives to the Juvenile Justice System

Various alternatives to handling children under the MACR exist within most jurisdictions, in order to provide informal, civil, or community services. In the United States, various diversionary systems are in place to address the needs of children and families together. In 2015, 45% of total juvenile court referrals were handled informally, and 65% of children under the age of 12 were handled informally (Abrams et al., 2019a). Abrams et al. (2019b) highlight some of these alternatives in Florida, New York, Illinois, and Pennsylvania.

In Florida, there are multidisciplinary teams that work collaboratively to assess each case individually. They emphasize family referrals to relevant social services or using the civil court systems in lieu of formal criminal court systems. In New York, legal actors generally work together to avoid referring young children with lower level offenses to court, and instead, divert them to informal social services. The Illinois Juvenile Act specifically encourages the use of diversionary alternatives that will promote productive, responsible, and educational benefits for a child in the community. The Act also requires children who have experienced abuse or neglect to be processed though the child welfare system instead of the criminal court system, which takes into consideration the individual needs and circumstances of each child. Interviews with legal actors also highlighted multiple opportunities for a child to be diverted prior to entering the juvenile justice system. If a judge feels there is a possibility the child could benefit from specific treatment or services, the judge can order a program, with a stipulation of the case being reassessed in the future.

Limitations

Because the studies by Abrams and colleagues (2018; 2019a; 2019b) focused on handpicked counties, states, and countries, there are limitations to the overview of data provided. Abrams et al. (2019a) reviewed the largest states and the most populated counties, which limits ability to generalize findings to smaller, more rural jurisdictions. Similarly, Abrams et al. (2019b) only focused on larger California counties and did not look at smaller, rural areas. This study was also limited by the data collection before and after the Gladys R. questionnaire was administered. Data regarding juvenile arrests or referrals that were dropped due to results of incompetency were not always recorded consistently or tracked. Therefore, the cases that were dropped from the system cannot speak to alternative handling and outcomes. Finally, Abrams and associates (2018) selected four differing nations to compare to one another, but did not do a deeper dive into local norms, direct fieldwork, or individual jurisdiction settings. Although some information can be inferred to other similar economic, social, and political climates, an international overview of four countries out of 195 limits generalizability and understanding.

Policy Implications

Although the MACR is set by legislation, it is not the only factor preventing or allowing a child to be prosecuted in court. Policy implications of this research show the need for each jurisdiction to seriously weigh how their MACR, or lack thereof, is impacting their juvenile justice system, incarceration rates, recidivism rates, and racial disparities. The main goal of capacity assessments is to protect vulnerable children from unfair court processes. This should be the goal in every jurisdiction, rather than the goal of making a child gain capacity or competency in order to move forward with the trial. Capacity and competency assessments also impact the MACR, governmental costs, and length of court processes. It would be beneficial for jurisdictions to look at other, similar areas who recently raised the MACR; how it was implemented; what alternatives are in place for young children; and their successes and challenges to the process. With this comes the need for more research in each specific country on what works best for their jurisdictions and how to implement improvements.

Implications for Future Research

There is little recent research regarding the MACR, especially in the United States. Future studies should focus on analyzing the costs spent on the front end versus the deep end of the system, examining the needs of the young children population, and assessing any discretionary opportunities legal actors have when moving forward with a juvenile referral. In relation to capacity and competency services, research should focus on investigating effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis to either support the expansion of restoration services or remove them as an option (Abrams et al., 2019b). A similar look into diversionary alternatives in various states and countries would also be helpful, such as in other youth systems, services, and facilities. There are also research gaps in following a juvenile referral from beginning to end and looking at different outcomes for young children in comparison to teenagers (Abrams et al., 2019a). Ensuring data collection at each stage would help provide a bigger picture explanation of the population in each state.

Recent research by Abrams and colleagues (2018; 2019a; 2019b) shows the variations, complications, and trends among different national and international juvenile justice systems. Informal boundaries, local practices, and discretion in decision-making points allow for the system to work differently in reality than reflected in written legislation. Establishing age parameters into and out of the justice system is vital in guiding our youth toward appropriate services, fair case handling, and opportunities for a successful future. Although there are many benefits to a higher MACR, there are dangers in combining young teenagers with adults in sentencing and housing (Abrams et al., 2018). Maintaining separate systems and establishing age-appropriate services for juveniles are equally important to diverting young children away from the formal systems. Capacity and competency assessments are not always directly related to chronological age, and special consideration for individual traits should be considered. Some concerns regarding the victim impact and restitution costs also need to be considered when establishing an appropriate MACR, but support in early diversionary programs can be beneficial for all parties involved.

Abrams, L. S., Barnert, E. S., Mizel, M. L., Bedros, A., Webster, E., & Bryan, I. (2019a). When Is a Child Too Young for Juvenile Court? A Comparative Case Study of State Law and Implementation in Six Major Metropolitan Areas. Crime & Delinquency , 001112871983935. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719839356

Abrams, L. S., Barnert, E. S., Mizel, M. L., Bryan, I., Lim, L., Bedros, A., Soung, P., Harris, M. (2019b). Is a Minimum Age of Juvenile Court Jurisdiction a Necessary Protection? A Case Study in the State of California. Crime & Delinquency , 65 (14), 1976–1996. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128718770817

Abrams, L. S., Jordan, S. P., & Montero, L. A. (2018). What Is a Juvenile? A Cross-National Comparison of Youth Justice Systems. Youth Justice , 18 (2), 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225418779850

Countries Compared by Crime Age of criminal responsibility. International Statistics. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nationmaster.com/country-info/stats/Crime/Age-of-criminal-responsibility .

Delmage, E. (2013). The Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility: A Medico-Legal Perspective. Youth Justice , 13 (2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225413492053

Minimum age for delinquency adjudication: Multi-jurisdiction survey . National Juvenile Defender Center. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://njdc.info/practice-policy-resources/state-profiles/multi-jurisdiction-data/minimum-age-for-delinquency-adjudication-multi-jurisdiction-survey/ .

Minimum Ages of Criminal Responsibility in Europe. Child Rights International Network. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://archive.crin.org/en/home/ages/europe.html .

The minimum age of criminal responsibility continues to divide opinion. (2017, March 15). Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2017/03/15/the-minimum-age-of-criminal-responsibility-continues-to-divide-opinion .

Morgan, R. (2010). Children’s Rights and the Minimum Age of Criminal Responsibility: A Global Perspective. By Don Cipriani (Farnham: Ashgate, 2009, 232pp. 55.00 hb). British Journal of Criminology , 50 (5), 990–991. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq044

Schloeman, M. I. (2016). Determining the Age of Criminal Capacity: Acting in the best interest of children in conflict with the law. South African Crime Quarterly , (57). https://doi.org/10.17159/2413-3108/2016/v0n57a39

Wagland, P., & Bussey, K. (2017). Appreciating the wrongfulness of criminal conduct: Implications for the age of criminal responsibility. Legal and Criminological Psychology , 22 (1), 130–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12090

Photo by Bernard Hermant on Unsplash

Blog Categories

- News & Announcements

- Continued Evidence-Based Education

Recent Articles

Evidence-Based Professionals' Monthly - May 2024

Understanding the Criminal Pathways of Victimized Youth

The Price of Punishment: Exclusionary Discipline in Connecticut PreK-12 Schools

Breaking the Cycle of Absenteeism: Strategies for Prevention

Evidence-Based Professionals' Monthly - March 2024

Evidence-based professionals' monthly - april 2024.

Quarterly for Evidence-Based Professionals - Volume 8, Number 3

Unlock the Power of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): Elevate Your Practice!

MI Days-2.0

Get Your Free Article to...

"Becoming An Evidence-Based Organization (EBO)

Five Key Components To Consider" by David L. Myers, PhD.

Would You Like To Set Your Leadership Apart from The Typical?

"Becoming An Evidence-Based Practitioner (EBP)

How To Set Yourself Apart" By Mark M. Lowis, MINT

Would You Like To Set Your Yourself Apart from The Typical Practitioner?

Masterclass Options

We offer a Masterclass & Certification for LEADERS and PRACTITIONERS. Which are you interested in exploring?

5 reasons why the age of criminal responsibility should be raised

1. it should be a public health (not criminal justice) response.

The vast majority of children involved in offending behaviour from age 10 to 14 are either childr e n who will ‘grow out of it’ with proper support and without being brought into the juvenile justice system, or those who have a difficult personal, family or community background who need a public health response, not a criminal justice response.

2. The younger the child enters the criminal justice system the more likely they will reoffend

Bringing children into the juvenile justice system has a criminogenic effect; that is the younger a child is at their first contact with the criminal justice system, the greater their chances of future offending.

3. Indigenous children are disproportionately affected

Most importantly, Aboriginal and Indigenous children are highly over-represented in this group of children so positive, culturally and age-appropriate responses are critical for these children to reduce this over-representation.

4. It is expensive

It is extremely costly to bring children into juvenile detention – that money urgently needs to go into therapeutic justice re-investment.

5. It would be in line with the rest of world

Raising the age to 14 would bring Australia into line with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The UN Committee has repeatedly recommended and most recently expressed its regrets at Australia’s lack of implementation of its previous recommendations, and remains seriously concerned about:

(a) The very low age of criminal responsibility;

(b) The enduring over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children and their parents/carers in the justice system.

Judy Cashmore is Professor of Socio-Legal Research and Policy in the University of Sydney Law School and joint Professorial Research Fellow, School of Education and Social Work . (Photo credit: Pixabay)

Need more news?

Elissa blake.

- +61 408 565 604

- [email protected]

Related articles

Expert witness bias largely unchecked in australian courts, university of sydney sociologist bound for the ias in princeton, fatal woman, the origin of evil, and other tantalising tales.

- Laws & Rights

- Stock Market

- Real Estate

- Middle East

- North America

- Formula One

- Other Sports

- Science, Technology & Environment

- Around the Web

- Webiners and Interviwes

- Google News

- Today's Paper

- Webinars and Interviews

Won’t someone think of the children?

Why the Minimum age of criminal responsibility should be raised in Bangladesh

Bangladesh ratified the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Child -UNCRC (1989) all the way back in 1990, and Article 40.3 of the Convention defines the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) as “the age below which a person is completely immune from any criminal liability due to lack of maturity and judgment to understand the consequences of one's actions.” The age is below the MACR (12 years or higher) as recommended by the UNCRC. At present, in Bangladesh, the MACR is nine years which is below the recommended age by the Convention.

In recent years, there have been a number of initiatives taken by the Bangladesh government to ensure the disparate treatment of children under the justice system. In 2004, Bangladesh raised the MACR from seven to nine after almost 14 years after it had ratified the UNCRC. As a part of it, the government has enacted the Children Act 2013 (amended 2018) repealing the Children Act 1974. However, in Bangladesh the MACR remains nine, as per Section 82 of the Penal Code 1860. This means children under the age of nine cannot be charged with and sentenced for committing any given offense.

With juvenile crimes coming to the attention of police in Bangladesh over the last decade or so, the numbers of children entering justice systems has also increased. According to the available statistics of the Department of Social Services (2024) in three Child Development Centres, many children -- particularly girls -- are sent and detained under the justice system for committing minor offenses (eg running away from home, underaged marriage, theft, shoplifting, and brawling). Evidence shows that in May 2024, there were almost 939 children (both girls and boys) in the three CDCs, and a considerable number of children below the age of 12 who have been detained or sent to these centres before their 12th birthday. If the MACR was to be increased, the recidivism rate would drop considerably among children.

In 2015, the UN Committee on the Rights of the Child expressed concerns about the Children Act (2013) not to specify MACRC. T he Committee has reiterated its previous that the minimum age of criminal responsibility (9) is still very low. The committee recommended to raise the minimum age of criminal responsibility to an internationally acceptable standard. Bangladesh has not taken any further initiative to increase the MACR after 2004.

In total, 196 countries have signed up to the UNCRC and the MACR of children varies among them while some countries are in the process of increasing the age. This age of children varies among South Asian countries, for example in Nepal, Bhutan, Afghanistan and Sri Lanka this ages are 10, 10, 12, and 12 respectively. In India, the present age of criminal responsibility is seven years. In India an offense committed by the child of age between seven years and 12 years will not be punishable if the judge is of the opinion that the child is not mature enough to understand the consequences of his actions.

Bangladesh raised the age in 2004 but still there is a continuous pressure from the United Nations to raise the age to protect children’s rights. Due to rising criminal offenses, particularly by children and young people, few countries have lowered the MACR, and many have considered doing the same. In contrast, some countries have increased the MACR to comply with the UNCRC.

In my opinion, increasing the threshold of age by amending this Act would protect many children, particularly those who commit minor offenses and/or those who commit offenses without understanding the consequences. Many NGOs advocate for increasing the MACR, but the government is not taking any visible initiatives to do so. In order to ensure a welfare-based justice approach rather than a punitive approach, the government should focus on the needs of the children rather than their deeds.

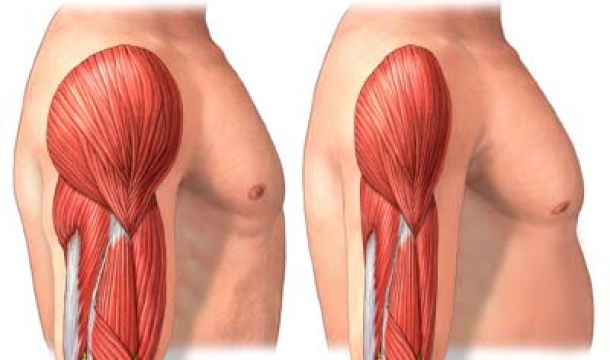

Like other countries, the principle of doli incapax which is a rebuttable presumption that children aged 10-13 years (inclusive) lack the capacity to form criminal intent, should be clearly stipulated in existing acts and legislations to ensure the safeguard of the children. Research shows that brain development, particularly the synaptic pruning in the prefrontal cortex, occurs between 20 and 30 years of age. This means that children above between nine and below 12 are not of sufficient maturity to understand the consequences of their deeds.

In Bangladesh, there has been a sharp rise in crimes committed by children or young people. However, it is important to understand how the children are being treated under the justice system once they come under the justice system as a first-time offender. It is important to take the decision or make the changes based on evidence rather than focusing on public sentiment to be tough on offenses committed by children.

Bangladesh should be fully in tune with the ratified convention to ensure the best interests of the children who come in conflict with the law. Welfare approach should be adopted for the care and protection of the children. The justice system should take into consideration how committing offenses by children is not related to their brain development. If the MCRC is increased then many children will not come into the deep end of the system.

Bangladesh should increase the MACR to 12 so that there should be a child-oriented justice system in Bangladesh. This will ensure the well-being and best interests of children in conflict with the laws by increasing the MACR. Many INGOs, as well as local human rights organizations, have started asking the government to amend the existing law to comply with the global best practices on children’s rights protection.

Bangladesh should change the policy and take initiative to increase the MCRC based on evidence to protect the children from doing further offense and being stigmatized with an ultimate aim to ensure their best interests.

Shilpi Rani Dey PhD is Associate Professor, Department of Social Work, Jagannath University. She can be reached at [email protected] .

Every child has a right to education

Protecting children from becoming political pawns, once upon a time…, children and youths for disaster risk reduction in bangladesh, where will the children play, foreign minister: bangladeshi students in kyrgyzstan are safe, government to legalize battery run autorickshaws/vehicles, cabinet approves signing of apostille convention: nearly 500c to be saved annually, roundtable discussion on china-bangladesh relations held at du, pm to meet with 14-party leaders on thursday.

Popular Links

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Advertisement

Connect With Us

- Election 2024

- Entertainment

- Newsletters

- Photography

- Personal Finance

- AP Investigations

- AP Buyline Personal Finance

- AP Buyline Shopping

- Press Releases

- Israel-Hamas War

- Russia-Ukraine War

- Global elections

- Asia Pacific

- Latin America

- Middle East

- Election Results

- Delegate Tracker

- AP & Elections

- Auto Racing

- 2024 Paris Olympic Games

- Movie reviews

- Book reviews

- Personal finance

- Financial Markets

- Business Highlights

- Financial wellness

- Artificial Intelligence

- Social Media

“Raise the Age” juvenile justice reforms altered by North Carolina Senate

- Copy Link copied

RALEIGH, N.C. (AP) — More youths accused of serious crimes in North Carolina would be automatically tried in adult court in legislation that advanced through the state Senate on Wednesday.

The measure approved 41-4 reworks some of the bipartisan juvenile justice reforms approved by the General Assembly that ended in late 2019 the mandate that 16- and 17-year-olds be tried in the adult criminal justice system.

The bill’s chief proponent says the changes will ease backed-up juvenile court caseloads for prosecutors by putting matters that ultimately will end up in adult Superior Court immediately there instead.

The “Raise the Age” law was designed to reduce recidivism through the services offered to youths in the juvenile system and help young people avoid having lifetime criminal records if tried in adult courts. Juvenile records are confidential.

The current law says that 16- and 17-year-olds accused of the most serious felonies, from murder and rape to violent assaults and burglary, must be transferred to Superior Court after the notice of an indictment being handed up or when a hearing determines there is probable cause a crime was committed. Prosecutors have discretion in keeping cases for some of the lower-grade felonies in juvenile court.

The measure now heading to the House would do away with the transfer requirement for most of these high-grade felonies — usually the most violent — by trying these young people in adult court to begin with.

Sen. Danny Britt, a Robeson County Republican, said the provision addresses a “convoluted” transfer process for juvenile defendants, the bulk of whom are winding up in adult court anyway.

“Like any law that we pass in this body, there are some kind of boots-on-ground impacts that we need to look at,” Britt, a defense attorney and former prosecutor, said in a committee earlier Wednesday. “And if we see that things are not going as smoothly as what we want them to go in the judicial system, and there are ways to make things go smoother ... we need to adjust what we’ve done.”

The bill also would create a new process whereby a case can be removed from Superior Court to juvenile court — with the adult records deleted — if the prosecutor and the defendant’s attorney agree to do so.

Advocates for civil rights and the disabled fear legislators are dismantling the “Raise the Age” changes, which they say help more young people adjudicated in the juvenile system access mental health treatment and other services in youth centers before they return to their communities.

When someone is in adult court, a defendant’s name is public and it’s harder to get the person to cooperate and testify against “more culpable people,” said Liz Barber with the North Carolina chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union.

“It is going to be a harder lift for those juvenile defense attorneys to convince a prosecutor who already has them in adult court to remand someone down to juvenile court than it is if you have someone in juvenile court and getting them to keep them there,” Barber told the Senate Rules Committee.

Britt rejected the idea that the changes were harming the “Raise the Age” effort.

The juvenile transfer change was sought in part by the North Carolina Conference of District Attorneys, which represents the state’s elected local prosecutors.

North Carolina had been the last state in which 16- and 17-year-olds were automatically prosecuted as adults. These youths are still tried in adult court for motor vehicle-related crimes.

The Senate on Wednesday also approved unanimously and sent to the House a measure portrayed as modernizing sex-related crimes, particularly against minors, in light of new technology like artificial intelligence.

The bill, for example, creates new sexual exploitation of a minor counts that make it a lower-grade felony to possess or distribute obscene sexual material of a child engaging in sexual activity, even if the minor doesn’t actually exist.

And a new sexual extortion crime would address someone who threatens to disclose or who refuses to delete a sex-related “private image” unless cash or something else of value is received.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

The law. Section 16 of the Children and Young Persons Act 1963 states the age of criminal responsibility in England and Wales at ten years. All children under this age are presumed to be doli incapax (incapable of committing a crime). After reaching the age of ten however, and as Elizabeth Stokes informs us, there is nothing within the ...

The age of criminal responsibility. The age of criminal responsibility in England and Wales is ten years. [ 3] All children under this age are presumed to be doli incapax (incapable of committing a crime). After reaching the age of ten however, and as Elizabeth Stokes informs us, there is nothing within the substantive criminal law regarding ...

The minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) refers to the youngest age at which an individual can be processed formally in the justice system. Although using chronological age may seem as simple as identifying a number, determining this number is much more complex. Factors such as brain development, competency, and childhood experiences ...

The age of criminal responsibility: D evelopmental science and human rights perspectives. Farmer, E. (2011). In Journal of Children's Services, 6 (2), 86-95. Winner of Emerald Literati ...

Age and Criminal Responsibility. G. Maher. Published 2005. Law. Age is a relatively unexplored topic in the theoretical literature on criminal responsibility. The first part of this paper examines a project on the age of criminal responsibility conducted by the Scottish Law Commission, the official law reform body for the law in Scotland.

Raising the age of criminal responsibility There are strong moral, medical and legal arguments for raising the age of criminal responsibility from 10 years of age. Most Australians already think that the age of criminal responsibility is 14 years or higher, and when told it is not most Australians support raising it to 14. Discussion paper

The age of criminal responsibility is the primary legal barrier to criminalisation and thus entry into the criminal justice system. This paper1 provides arguments for raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR). Nationally the minimum age is 10 years old. Some Australian states set the MACR at 10 years in the mid-to

The age of criminal responsibility is the age below which a child is deemed incapable of having committed a criminal offence. In legal terms, it is referred to as a defence/defense of infancy, which is a form of defense known as an excuse so that defendants falling within the definition of an "infant" are excluded from criminal liability for ...

In the three UK jurisdictions - England and Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland - the minimum age of criminal responsibility falls significantly below the European average. In England and Wales, for example, the largest UK jurisdiction by some distance, children are held to be fully responsible in criminal proceedings once they reach the ...

Adam Graycar Director. In all Australian jurisdictions the statutory minimum age of criminal responsibility is now 10 years. Between the ages of 10 and 14 years, a further rebuttable presumption (known in common law as doli incapax) operates to deem a child between the ages of 10 and 14 incapable of committing a criminal act.

Summary. The age of criminal responsibility - the age below which a child is deemed not to have the capacity to commit a crime - is currently set at 10 years in England and Wales and in Northern Ireland. Scotland has the youngest age of criminal responsibility in Europe at 8 years of age.

Abstract. This paper provides arguments for raising the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR). Nationally the minimum age is 10 years old. Some Australian states set the MACR at 10 years in the mid-to late1970s (Queensland (1976), NSW (1977) and South Australia (1979)). However, only since the early 2000s has there been a uniform ...

The minimum age of criminal responsibility in England and Wales remains 10 years: something which has attracted criticism globally by policy makers and youth justice practitioners. Yet, the Westminster Government refuses to consider changes to minimum age of criminal responsibility, despite evidence supporting reform. ...

Professor Judy Cashmore, from the University of Sydney Law School, outlines five urgent reasons why we must raise the age of criminal responsibility from 10 to 14 now. "It's time to make the change," she says. 1. It should be a public health (not criminal justice) response. The vast majority of children involved in offending behaviour from age ...

Considerable recent attention has been directed towards rules governing the minimum age of criminal responsibility, and the imposition of criminal responsibility above that age depending on a young offender's appreciation of the wrongness of their act. This paper examines the operation of these rules, along with criticisms and prospects for reform.

Search for more papers by this author. Leigh Haysom, Corresponding Author. ... (Age of Criminal Responsibility) Bill 2021. The Bill proposed to amend section 5 of the Children (Criminal Proceedings) Act 1987 (NSW) so that 'it should be conclusively presumed that no child who is under the age of 14 years can be guilty of an offence'. It also ...

However, the age of criminal responsibility varies greatly across the world. It ranges from 6 in North Carolina or 7 in India, South Africa, Singapore and most of the United States of America, to 13 in France 16 in Portugal and 18 in Belgium. There has recently been much talk in England and Wales, where the age is now 10, about whether this ...

1 INTRODUCTION. The minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) refers to the minimum age at which a person might be held criminally liable (Cipriani, 2009).The recent amendment to China's Criminal Law came into effect in 2021, lowering the age of criminal responsibility to twelve years for two specified offences.

Essay Writing Service. The age of criminal responsibility is the age at which a child can be considered an adult for purposes of criminal prosecution. In England and Wales, the criminal age of responsibility is set at age ten and is one of the lowest in Europe, with only Switzerland being lower at age seven. Countries such as Uganda, Algeria ...

Criminal youth justice introduction in this essay will be critically analysing the current in england and wales, the issues with the current policy and the. Skip to document. University; High School. ... T o raise the age of criminal responsibility may lead to issues like a la ck. of justic e for the victims, ...

MANILA, 18 January 2019 - UNICEF is deeply concerned about ongoing efforts in Congress to lower the minimum age of criminal responsibility in the Philippines below 15 years of age. The proposed lowering vary from 9 and 12 years, and goes against the letter and spirit of child rights. There is a lack of evidence and data that children are ...

In many instances, the line that separates creative acts from criminal ones is thin and arbitrarily drawn, shaped by the discretion and biases of various decisionmakers, including police, prosecutors, or juries. Creative acts are mischaracterized as criminal ones. Creative expressions are used as evidence of one's criminality or dangerousness.

Bangladesh ratified the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Child -UNCRC (1989) all the way back in 1990, and Article 40.3 of the Convention defines the minimum age of criminal responsibility (MACR) as "the age below which a person is completely immune from any criminal liability due to lack of maturity and judgment to understand the consequences of one's actions."

The measure approved 41-4 reworks some of the bipartisan juvenile justice reforms approved by the General Assembly that ended in late 2019 the mandate that 16- and 17-year-olds be tried in the adult criminal justice system.