'I Lost 190 Pounds Using Therapy To Manage My Binge-Eating Disorder'

“I’d eat until I felt sick, go to bed, and wakeup for a midnight snack.”

I grew up overweight, but I didn't really become aware of it until third grade. It hit me one day in gym class when a boy I had a crush on told me I looked like I was pregnant—I was devastated.

Then, my weight started to yo-yo. In high school, I tried out LA Weight Loss and lost 85 pounds, but gained it all back (and then some) so that by my sophomore year in college, I weighed 353 pounds. But it didn't end there: I had gastric bypass surgery as a 19-year-old college student and lost 154 pounds. But, 10 years later, my weight crept back up 305 pounds.

Once I hit 325 pounds again—my second highest weight—I knew I needed to make some changes.

In January 2017, I made a New Year's resolution to lose weight once and for all—and my first step was getting treatment for binge-eating disorder, depression, and anxiety. I realized I needed help when I found myself living the same dismal day over and over again—and food was my only oasis.

It took therapy to make me realize how awful my eating habits had become: I ate from the moment I woke up to the moment I went to bed. I'd often eat until I felt sick, go to bed, then wake up and do it all again the next day—and sometimes I'd even wake up in the middle of the night and snack. I also had physical symptoms: I always felt lethargic, sluggish, and bloated.

In therapy, we worked on developing normalized eating habits—but absolutely no crash or fad dieting.

I did still revamp my diet though, and I chose to keep it as simple as possible for myself. I ate 1,200 calories per day, which meant I had to drastically reduce my portion sizes. Because of that, I began eating foods that were already portioned out for me, like cans of soup or 100-calorie packs of popcorn. I also cut way back on fast food. Here's what I typically eat in a day:

- Breakfast: Coffee and a vanilla protein shake

- Lunch: Progresso Light Chicken and Vegetable Rotini Soup, an orange

- Snacks: 100-calorie bag Orville Redenbacher popcorn sprayed with I Can't Believe It's Not Butter Spray and sprinkled with Truvia, a sugar-free gelatin cup, or a low-fat cheese stick

- Dinner: Steak Portobello Lean Cuisine, with sautéed mushrooms and half of a light English muffin

- Dessert: Halo Top Ice Cream (rotating flavors, but Peanut Butter Cup is my favorite)

I also started to exercise regularly, committing to 45 minutes of movement daily.

Before therapy and dieting, I was constantly in pain and out of shape—even hoisting myself out of bed every morning was super-painful.

After I saw some progress with dieting, I added in exercise and chose to do essentially all cardio: primarily walking on the treadmill and increasing the incline gradually. I used the elliptical machine for some variety. Finally, after several months and feeling more fit, I mounted the stair-stepper machine and it became my go-to for an intense workout.

Two years after I decided to make a change, I've lost 190 pounds.

I always tell people that small, daily efforts really add up—all of my progress was achieved one day at a time. On really difficult days—which I still have—I take things one meal or one moment at a time.

And while I'm proud of my weight loss, I want other women to know that they should never put their lives on hold while they're waiting to lose weight, like I did in the past. If there's no weight or size limit on your interests, then get out there and pursue them now. It makes the journey the much more enjoyable.

Weight-Loss Success Stories

This Mom Lost 95 Lbs. With WW And Walking

This Mom Lost 95 Lbs. With Keto And IF

This Mom Lost 75 Lbs. With The 80/20 Rule

'I Lost 135 Pounds By Counting Macros'

How 8 Women Crushed Their Resolutions In 2022

'What Finally Made Weight Loss Click For Me'

The 30-Day Fitness Challenge You Need To Try

‘I Lost 190 Lbs. By Eating Healthy And Running’

This Mom Lost 90 Lbs. By Counting Calories

‘I Lost 90 Pounds With Portion Control, Lifting’

'I Lost 100 Lbs. With WW And Jazzercise'

Binge eating linked to weight-loss challenges

Someone who binge eats consumes an objectively large amount of food while feeling a loss of control over eating. When episodes occur weekly for several months, the action moves into the realm of binge-eating disorder. So how does this type of eating affect people with Type 2 diabetes and obesity who are actively working to lose weight?

According to new findings from the University of Pennsylvania published in the journal Obesity , it presents a significant obstacle: Those who continue to binge eat while trying to lose weight drop about half as much as those who don't or those who do and then subsequently stop.

"Continued binge eating can act as a barrier to achieving success," said Ariana Chao, an assistant professor in the Penn School of Nursing.

Chao studies how addictive-like eating behaviors influence treatment effectiveness for different populations. To better understand the role of binge eating in weight loss, she and colleagues from Penn's Perelman School of Medicine, the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia, the University of Connecticut and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases assessed data from a study called Action for Health in Diabetes, or Look AHEAD. This multi-center randomized, controlled trial included more than 5,000 participants ages 45 to 76, all with a body mass index above 25 (or 27 for those using insulin) and Type 2 diabetes.

Look AHEAD's original aim was to compare the effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality of two treatment options: an intensive lifestyle intervention designed to induce weight loss and diabetes support and education. The former included dietary recommendations, physical activity and behavior modifications; those in the latter group were encouraged to attend three sessions per year, one each about physical activity, social support and eating.

In addition, Look AHEAD annually assessed binge eating. Via a questionnaire, participants noted any instances in the past six months during which they consumed excess food and felt a lack of control over that consumption.

For this study, Chao and her team, which included Thomas Wadden, the Albert J. Stunkard Professor of Psychology in Psychiatry and director of Penn's Center for Weight and Eating Disorders, analyzed the impact of binge eating on weight loss. The researchers found that at four years, participants who reported no binge eating or a reduced tendency to do so lost more weight than those who continued to binge eat. Participants lost 4.6 percent of initial body weight compared to 1.9 percent.

"Previously, it was unclear whether people who binge eat need to be treated for that behavior before attempting behavioral weight loss or whether they'll do OK in behavioral weight loss without it," said Chao, who has a secondary appointment in the Department of Psychiatry. "Our findings suggest that people who continue to binge eat after they start a behavioral weight-loss program need an additional treatment like cognitive behavioral therapy, which is one of the most effective for this condition."

Such treatment includes work to recognize the interconnectedness of thoughts, feelings and behaviors, Chao said. For instance, if someone eats to cope with stress, CBT could aim to untangle why and how to change the behavior.

Though this study looked at a particular subset of people, two-thirds of the adult population in the United States is either overweight or obese. For that reason, Wadden said it's important for clinicians to screen for these behaviors and, if found, refer those patients for additional care.

"Individuals with a history of binge eating shouldn't be excluded or discouraged from engaging in behavioral weight loss," he said. "But binge eating should be monitored regularly during weight loss. Participants who continue to report this may benefit from additional or more targeted treatment to ensure success."

- Diet and Weight Loss

- Eating Disorder Research

- Eating Disorders

- Dieting and Weight Control

- Nutrition Research

- Bulimia nervosa

- Weight Watchers

- Cardiac arrest

- Hyperthyroidism

- Deadly nightshade and related plants

Story Source:

Materials provided by University of Pennsylvania . Note: Content may be edited for style and length.

Journal Reference :

- Ariana M. Chao, Thomas A. Wadden, Amy A. Gorin, Jena Shaw Tronieri, Rebecca L. Pearl, Zayna M. Bakizada, Susan Z. Yanovski, Robert I. Berkowitz. Binge Eating and Weight Loss Outcomes in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes: 4-Year Results from the Look AHEAD Study . Obesity , 2017; 25 (11): 1830 DOI: 10.1002/oby.21975

Cite This Page :

Explore More

- Stopping Flu Before It Takes Hold

- Cosmic Rays Illuminate the Past

- Star Suddenly Vanish from the Night Sky

- Dinosaur Feather Evolution

- Warming Climate: Flash Droughts Worldwide

- Record Low Antarctic Sea Ice: Climate Change

- Brain 'Assembloids' Mimic Blood-Brain Barrier

- 'Doomsday' Glacier: Catastrophic Melting

- Blueprints of Self-Assembly

- Meerkat Chit-Chat

Trending Topics

Strange & offbeat.

Healthy weight loss: a how-to guide

- Top 10 tips

- What to eat

- High protein

- Intermittent fasting

- Other diets

- Metabolic health

- Measuring success

- Breaking a plateau

- The long term

Everyone knows that to lose weight, you’re supposed to eat fewer calories and burn more. The problem is, eating less than you’d like is often easier said than done.

You might be able to deal with hunger for a few weeks or even months, but at some point, hunger wins. And then, the weight tends to come back.

What’s the best way to achieve weight loss in a healthy, sustainable way, without hunger or “white-knuckle” willpower?

The approaches that work tend to follow the same basic principles: eat the lowest calorie foods that fill you up, eliminate high-processed foods that don’t, and make sure you get essential nutrition.

It sounds easy. But why do so many of us struggle with healthy weight loss?

This guide will tell you the best ways to achieve healthy weight loss. It has our top weight loss tips, what to eat and what to avoid, the common mistakes you might be making, how to eat fewer calories, and much more.

But first, what is “healthy weight loss?”

Healthy weight loss starts with setting realistic goals . After that, we define healthy weight loss as mainly losing fat mass instead of lean body mass, improving your metabolic health, having a minimal decline in your resting metabolic rate, and making sure you can maintain your dietary lifestyle long-term.

If you’re struggling with your weight, it may not be your fault. The industrial food environment is stacked against you. The good news is that there are effective approaches to reach your best weight and improve your metabolic health long term! Here’s how.

Key takeaways

Top 10 weight loss tips

- Avoid eating carbs and fat together. This combination provides excessive calories with little to no nutritional value — think pizza, cookies, chips, donuts, etc. — and may increase cravings.

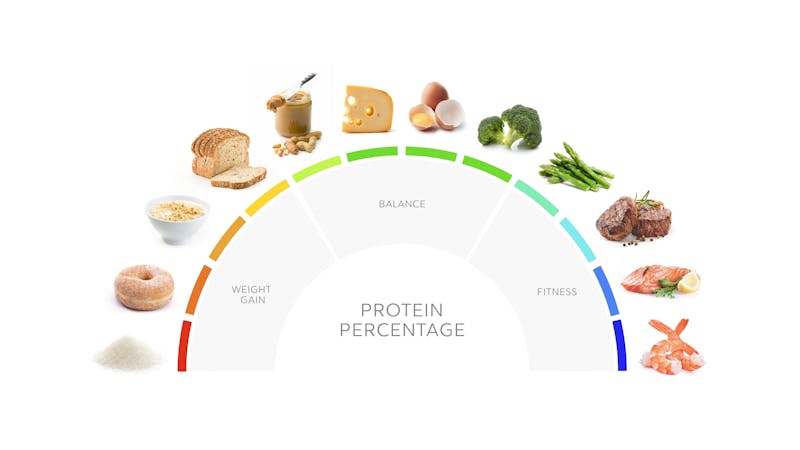

- Eat at least 30 grams of protein at most meals. Protein foods are the most satiating and nutrient-dense type of food.

- On a low carb approach, which is often a successful weight loss strategy, limit net carbs to less than 100 grams (or keep them as low as 20 grams per day, if you want to try a keto diet).

- Fill your plate with fibrous veggies. These provide abundant nutrients, high food volume, and relatively few calories.

- Add enough fat for taste and to enjoy your food, but not more than you need. Let’s be honest, fat tastes great! Taste is an essential part of long-term nutritional success. But too much fat can add calories you don’t need.

- If you’re hungry, start with adding more protein and vegetables. Again, these are the most satiating and nutritious food for the fewest calories.

- Find foods you enjoy that fit the above criteria. Check out our recipes here .

- Stay physically active. You don’t have to run marathons, but physical activity added to a healthy diet can help maintain fat loss while preserving muscle mass.

- Get adequate restorative sleep. Sleep like your health depends on it, because it does!

- Create an environment to promote your success. It isn’t just about knowing what to do. It’s also about creating the environment that will help you succeed. For example, removing tempting foods from your kitchen is just one great way to get started.

What foods to eat and what foods to avoid for healthy weight loss

For healthy weight loss, you want to make every calorie count.

But that doesn’t mean you have to count calories.

How is that possible? By focusing on the foods in the list below, you’ll ensure you are getting adequate nutrition, eating filling foods, and naturally decreasing your caloric intake.

We recommend focusing the bulk of your nutrition on “foods with the most nutrition per calorie”, consider portion control of foods with “moderate nutrition”, and reduce or eliminate foods with the least nutrition per calorie. Give it a try!

Foods with the most nutrition per calorie:

- Meat and poultry

- Non-starchy vegetables

- Dairy products like yogurt and cottage cheese

- Soy, beans, and lentils

Foods with moderate nutrition per calorie:

- Nuts and seeds

- Fatty processed meats like bacon

- Starchy vegetables

- Low-sugar fruits like berries, olives, and avocados

- Whole grains

Foods with the least nutrition per calorie

- Foods with high amounts of sugar and refined starches

- Sugar-sweetened beverages and fruit juice

- Beer and sweetened alcoholic beverages

- Pure added fats like oil and butter

Are you still hungry between meals, or are you looking for ways to add more protein to your diet? Take a look at our guide on high-protein snacks for weight loss. You can choose from hard-boiled eggs, a can of tuna, beef jerky, lupini beans, black soybeans, and more.

Why we recommend high protein for weight loss

Refined carbohydrates (sugar, bread, pasta, etc.) and refined fats (mostly oils) are high in energy density but lack nutritional value and are easier to overeat.

That’s why, for high nutrition eating, we recommend:

- Reduce your carbohydrate intake.

- Prioritize your protein and fibrous vegetables intake.

- Add just enough fat for taste and, if needed, extra calories.

How to get all essential nutrients

Fortunately, when you focus on whole-food proteins, the fatty acids and micronutrients are naturally present. And when you eat above-ground veggies, you automatically get fiber and additional micronutrients.

Based on calculations of the liver and kidney’s ability to safely handle protein, a 176-pound (80-kilo) person can theoretically consume a maximum of 365 grams of protein per day safely. 7 That’s 73% of a 2,000 calorie diet! It’s safe to say that most people won’t have to worry about eating too much protein.

Why we recommend low carb for weight loss

Low carb and keto diets also allow for adequate protein intake, plenty of above-ground fibrous veggies, and added fat for a complete, delicious, and sustainable healthy weight loss plan.

Based on the above data, plus practical considerations, we think carbohydrate reduction can play an essential role in healthy weight loss.

You can learn more about getting started eating low carb in our guides on a keto diet and a low carb diet for beginners.

Why we recommend intermittent fasting for weight loss

Intermittent fasting is an intentional avoidance of caloric intake for a set period. It can be as short as 12 hours (also called time-restricted eating) or as long as five or more days.

One reason that improved results were not seen in the time-restricted eating group may be that subjects ended up eating more calories during their eating window.

Fasting is not an excuse to binge eat or “make up for lost calories.”

Instead, fasting is meant to purposefully reduce caloric intake to preserve resting metabolic rate (the amount of energy you burn at rest), maintain lean muscle mass, and improve metabolic health. 15 In other words, intermittent fasting doesn’t just help with weight loss, but with healthy weight loss.

You can learn more about intermittent fasting in our intermittent fasting for beginners guide .

What other diets work for weight loss?

High-protein, low carb diets, which might also include short-term intermittent fasting, may be the best choice for many people to succeed with healthy weight loss.

Which diet is right for you? Only you can answer this question. The key is to find a pattern of eating that:

- Focuses on foods you like to eat

- Feels sustainable and enjoyable

- Helps you reduce your caloric intake

- Prevents excessive hunger

- Provides adequate nutrition

You may want to experiment with different diets to find the right one for you. And remember that it’s OK to change up your dietary approach as you age — and as your health, eating preferences, and lifestyle change.

How to eat fewer calories

That’s not what we are promoting.

Instead, we promote eating better. That means eating in a way that naturally allows you to reduce your calories without hunger. Does it sound too good to be true?

It doesn’t have to be.

These are all hyperpalatable foods that can make it difficult to control the amount you eat. 28 Overeating may have nothing to do with willpower or “being strong.” Instead, your brain may be telling you: This tastes great and has lots of calories for survival, I want more!

How to achieve metabolic health

However, you shouldn’t define health as merely avoiding disease. While that may be a great starting point, you don’t have to stop there!

Take waist circumference, for example. If you go by the definition used for metabolic syndrome, a normal waist circumference for a male is 39 inches (99 cm). Does that mean 39 inches is your end goal?

Maybe not! A waist size of 35 inches (88 cm) is likely much healthier for a 5’ 8” male than 39 inches. 31 Even though this may be your “end goal,” don’t expect to get there overnight. Continue to strive for slow and steady improvements over time, heading toward a more desirable result.

Just because medicine defines certain metrics as “normal” doesn’t mean they are your goal. Instead, focus on the lifestyles that get to the root cause of metabolic disease.

How can you achieve the goal of metabolic health? Here are our top eight tips.

8 tips to improve metabolic health

- Limit carbs — especially refined starches and sugars. Refined starches and sugars are the foods most likely to cause you to overeat calories and raise your blood sugar, insulin, blood pressure, and triglycerides. 32 A low carb approach may be the most effective diet for improving metabolic syndrome. 33 Low carb diets also successfully reduce hunger for most people. 34

- Eat adequate protein. Numerous studies demonstrate that, despite a slight temporary increase in insulin, higher protein diets improve insulin sensitivity over the long run and contribute to metabolic health. 35

- Moderate your fat intake. Excessive fat intake can raise triglycerides and worsen insulin resistance, especially if fat is combined with carbs or contributes to eating too many calories overall. 36 Eat enough fat to enjoy your meals, and eat fat that naturally comes with your food, such as the skin on your chicken or a naturally fatty rib eye. But don’t go out of your way to add unneeded fat to your foods.

- Don’t smoke. This should go without saying due to the strong connection of smoking to cancer and heart disease risk, but it also contributes to metabolic disease. 37

- Drink minimal to moderate amounts of alcohol. Alcohol provides empty calories that can affect liver health and undermine metabolic health. 38

- Manage stress and sleep well. Poorly controlled chronic stress and poor sleep can increase the likelihood of insulin resistance. 39

- Get regular physical activity. Muscles burn glucose. Building and using your muscles help promote insulin sensitivity and efficient energy utilization. 40

- Practice time-restricted eating or intermittent fasting. 41 Giving your body time without ingesting nutrients allows your insulin levels to decrease, improves insulin sensitivity, allows your body to learn to efficiently use fat for energy, and may even tap into autophagy. 42 The net result is improved metabolic health.

How to measure weight loss

The scale may tell you if your weight is going up or down. But healthy weight loss involves much more than the number on the scale.

Consider trying any of these three techniques in addition to using the scale:

- Follow your waist measurement and your waist-to-height ratio. All you need is a tape measure. If your weight is the same on the scale, but your waist is getting smaller, that is still a fantastic healthy fat loss victory! As we detail in our guide on losing belly fat , waist circumference is one of the best measurements to predict metabolic health and track healthy weight loss. 44

- How do your clothes fit? If you don’t have a tape measure, all you have to do is put on your (non-stretchy) pants. It doesn’t get much easier than that. Are your pants looser? That means your waist is getting smaller. If you are doing resistance training, you might also find that your arms and legs look more toned. That is a good sign that you are building muscle mass.

- Test your body composition. This requires additional tools — either a bioimpedance scale or a more detailed assessment with a DEXA scan or equivalent measuring device. A DEXA scan will not only tell you if your weight is changing, but it will also quantify how much weight loss was fat mass, lean body mass, and visceral fat. As a bonus, you also can follow your bone density to ensure maintaining strong bones is part of your healthy weight loss progress.

How to break weight loss plateaus

But it helps to have a plan for when the plateaus come. Here are the eight best tips for helping you to overcome a plateau and get back on track with healthy weight loss.

Top 8 tips for breaking a weight loss plateau 45

- Are you eating enough protein? Take a couple of days to measure all of the protein you eat and count every gram. Yes, it can be a hassle, but it can also be illuminating. You may think you are eating “plenty of protein,” only to find out you’re actually getting just 15% of your calories from protein. If that’s the case, the best tip for breaking your stall is to increase your protein intake.

- Are you eating enough fibrous vegetables? Fibrous vegetables are one of the best ways to increase nutrients for the minimum number of calories, increase stomach fullness, and slow gastric emptying. 46 Again, keeping track of your intake for a couple of days can help guide you in increasing your consumption of fiber-filled veggies. Aim for at least four cups per day.

- Are you limiting your non-nutrient calories? After increasing your protein and fiber-filled vegetables, what’s left? It’s usually non-nutrient calories — the extra dose of cream or butter, the rice that “comes with” your meal, the sugary salad dressing that seems so innocent. Or maybe it’s the ritual glass of wine with dinner. Experiencing a plateau is the perfect time to take stock of your non-nutrient calories and cut them in half or cut them out completely if you can.

- Are you struggling with cravings or snacking? Usually, addressing protein and fibrous vegetables can help cut down on snacking and cravings. However, if you still find yourself snacking, first make sure you are eating high-protein snacks . Next, make sure you’re snacking for real hunger and not boredom or routine. Finally, try eliminating non-nutritive sweeteners that can stimulate cravings, such as erythritol, stevia, and other sweet additives. 47

- How are you sleeping? Plateaus aren’t always about what you eat. Not only can poor sleep negatively affect your food choices during the day, but lack of sleep can also change your hormonal environment, making it nearly impossible to lose weight. 48 Make sure you prioritize good sleep hygiene. It’s easy to talk about but harder to do. Eliminate screens an hour before bed. Keep a steady sleep-wake routine. Make sure your bedroom is cool, dark, and quiet. Kick the kids and dogs out of your bed. You can keep your spouse, but only if their snoring doesn’t keep you up!

- Are you exercising? Exercise by itself is not great for weight loss. However, regular physical activity can help maintain weight loss and break plateaus when combined with healthy eating. Just make sure your exercise helps build muscle and doesn’t leave you hungry and craving food. For instance, you may find 20 minutes of resistance training more effective than 45 minutes on a treadmill.

- Have you tried time-restricted eating or intermittent fasting? For some, spacing out the timing between meals can naturally reduce caloric intake and allow for lower insulin levels. The combination may be enough to break a weight loss plateau.

Read even more in our detailed guide on tips to break a weight loss stall .

Maintaining weight loss long term

Authors have written hundreds of books on tips to maintain beneficial behavior change, and most of the tips aren’t a secret. The problem is when the recommendations become more items on your “to-do” list, adding chores to your routine that take time and energy you don’t have to give.

If that’s the case, don’t let yourself get overwhelmed. Pick one or two tips that resonate most with you, and stop there. Just because a tip made the list doesn’t mean you have to do it. The list is merely a collection of suggestions to try and see what works best for you.

Top tips for long-term success

- Connect with your why, to keep your motivation for maintaining your weight loss front and center.

- Create accountability with a partner, a coach, an app, or a calendar.

- Control your environment. Don’t allow temptations in your house or workplace.

- See your new way of eating as a lifestyle, not a diet. It isn’t something you “do.” It’s something you “are.” The language you use can make all the difference.

- Keep it enjoyable. Find recipes you love that fit within your eating pattern.

- Celebrate small successes on your way to bigger successes.

- Realize that you won’t be perfect, and that’s OK. Minor detours don’t have to derail you. Anticipate roadblocks and have a plan to get past them.

- Incorporate smart strategies for optimizing your sleep, stress management, and physical activity. Better habits in these areas can help with long-term, healthy weight maintenance.

Sample meals and meal plans

Keto for beginners

Guide A keto diet is a very low-carb, high-fat diet. You eat fewer carbs and replace it with fat, resulting in a state called ketosis. Get started on keto with delicious recipes, amazing meal plans, health advice, and inspiring videos to help you succeed.

Low carb for beginners

Guide Want to try a low carb diet for weight loss or health? In this top low carb guide, we show you what you need to get started: what to eat, what to avoid and how to avoid side effects. Get delicious low carb recipes and meal plans.

High-protein diet

Guide Our guide helps you understand what a high-protein diet is and why it might help you lose weight and improve your health.

Weight loss

4. Enjoy healthier foods

Adopting a new eating style that promotes weight loss must include lowering your total calorie intake. But decreasing calories need not mean giving up taste, satisfaction or even ease of meal preparation.

One way you can lower your calorie intake is by eating more plant-based foods — fruits, vegetables and whole grains. Strive for variety to help you achieve your goals without giving up taste or nutrition.

Get your weight loss started with these tips:

- Eat at least four servings of vegetables and three servings of fruits daily.

- Replace refined grains with whole grains.

- Use modest amounts of healthy fats, such as olive oil, vegetable oils, avocados, nuts, nut butters and nut oils.

- Cut back on sugar as much as possible, except the natural sugar in fruit.

- Choose low-fat dairy products and lean meat and poultry in limited amounts.

5. Get active, stay active

While you can lose weight without exercise, regular physical activity plus calorie restriction can help give you the weight-loss edge. Exercise can help burn off the excess calories you can't cut through diet alone.

Exercise also offers numerous health benefits, including boosting your mood, strengthening your cardiovascular system and reducing your blood pressure. Exercise can also help in maintaining weight loss. Studies show that people who maintain their weight loss over the long term get regular physical activity.

How many calories you burn depends on the frequency, duration and intensity of your activities. One of the best ways to lose body fat is through steady aerobic exercise — such as brisk walking — for at least 30 minutes most days of the week. Some people may require more physical activity than this to lose weight and maintain that weight loss.

Any extra movement helps burn calories. Think about ways you can increase your physical activity throughout the day if you can't fit in formal exercise on a given day. For example, make several trips up and down stairs instead of using the elevator, or park at the far end of the lot when shopping.

6. Change your perspective

It's not enough to eat healthy foods and exercise for only a few weeks or even months if you want long-term, successful weight management. These habits must become a way of life. Lifestyle changes start with taking an honest look at your eating patterns and daily routine.

After assessing your personal challenges to weight loss, try working out a strategy to gradually change habits and attitudes that have sabotaged your past efforts. Then move beyond simply recognizing your challenges — plan for how you'll deal with them if you're going to succeed in losing weight once and for all.

You likely will have an occasional setback. But instead of giving up entirely after a setback, simply start fresh the next day. Remember that you're planning to change your life. It won't happen all at once. Stick to your healthy lifestyle and the results will be worth it.

There is a problem with information submitted for this request. Review/update the information highlighted below and resubmit the form.

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips, current health topics, and expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

Error Email field is required

Error Include a valid email address

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Thank you for subscribing!

You'll soon start receiving the latest Mayo Clinic health information you requested in your inbox.

Sorry something went wrong with your subscription

Please, try again in a couple of minutes

- Hensrud DD, et al. Ready, set, go. In: The Mayo Clinic Diet. 2nd ed. Mayo Clinic; 2017.

- Duyff RL. Reach and maintain your healthy weight. In: Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics Complete Food and Nutrition Guide. 5th ed. John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

- Losing weight: Getting started. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/losing_weight/getting_started.html. Accessed Nov. 15, 2019.

- Do you know some of the health risks of being overweight? National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-topics/weight-control/health_risks_being_overweight/Pages/health-risks-being-overweight.aspx. Accessed Nov. 15, 2019.

- 2013 AHA/ACC/TOS guideline for the management of overweight and obesity in adults: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and The Obesity Society. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2014; doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.004.

- 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and U.S. Department of Agriculture. http://health.gov/dietaryguidelines/2015/guidelines. Accessed Nov. 15, 2019.

- Physical activity for a healthy weight. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/physical_activity/index.html. Accessed Nov. 15, 2019.

Products and Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

- The Mayo Clinic Diet Online

- A Book: The Mayo Clinic Diet Bundle

- A Book: Live Younger Longer

- Calorie calculator

- Carbohydrates

- Counting calories

- Weight-loss plateau

- Hidradenitis suppurativa: Tips for weight-loss success

- Keep the focus on your long-term vision

- Maintain a healthy weight with psoriatic arthritis

- BMI and waist circumference calculator

- Metabolism and weight loss

- Weight gain during menopause

- Weight Loss After Breast Cancer

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

- Healthy Lifestyle

- Weight loss 6 strategies for success

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and Outcomes of Binge-Eating Disorder [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2015 Dec. (Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160.)

Management and Outcomes of Binge-Eating Disorder [Internet].

Executive summary, definition of binge-eating disorder and loss-of-control eating.

Binge-eating disorder (BED) is characterized by recurrent episodes of binge eating—i.e., eating episodes that occur in a discrete period of time (≤2 hours) and involve the consumption of an amount of food that is definitely larger than most people would consume under similar circumstances. Other core features of BED are a sense of lack of control over eating during binge episodes, significant psychological distress (e.g., shame, guilt) about binge eating, and the absence of regular use of inappropriate compensatory behaviors, such as purging, fasting, and excessive exercise.

In May 2013, the American Psychiatric Association (APA) recognized BED as a distinct eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5). 1 Previously (in the DSM-IV), BED had been designated as a provisional diagnosis.

Table A presents the DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for BED. In the shift from provisional to formal diagnosis for BED, APA experts changed the criterion for frequency of BED from twice per week to once per week and the duration criterion from 6 months to 3 months, in line with those for bulimia nervosa.

DSM-IV and DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for binge-eating disorder.

A sense of loss of control (LOC) during binge episodes is a core feature of BED. The term “LOC eating” is used to describe these episodes, but it is also used more broadly throughout the literature to describe binge-like eating behavior accompanied by a sense of LOC that occurs across a wide spectrum of individuals. That spectrum includes, among others, individuals who exhibit some features of BED but do not meet full diagnostic criteria for the disorder (i.e., subthreshold BED) and individuals with other eating disorders (bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa binge-eating/purge subtype).

The spectrum of those described as exhibiting LOC eating also includes individuals for whom diagnosis of threshold BED is challenging for unique reasons, such as postbariatric surgery patients and children. Bariatric surgery significantly reduces the stomach size and capacity, effectively rendering it physically impossible for a patient to meet BED criterion 1a ( Table A ; i.e., to consume a definitely large amount of food). In the bariatric surgery literature, LOC eating is used not only to describe binge-like behavior that falls short of meeting criterion 1a, but also to describe eating behavior that is contraindicated based on meal size and meal content. Children, especially young children, may not meet BED criterion 1a because their parents or others limit the quantity of food they consume or because they are unable to provide accurate quantification of the amount they eat. For the purposes of our review, LOC eating treatment and outcomes are limited to postbariatric surgery patients and children, and do not include individuals in other groups who may meet subclinical diagnosis of BED.

Prevalence of Binge-Eating Disorder and Loss-of-Control Eating

Prevalence estimates (and citations) are covered in more detail in the full report. In the United States, the prevalence of BED among adults is about 3.5 percent in women and about 2 percent in men based on DSM-IV criteria and slightly higher based on DSM-5 criteria. 2 , 3 BED is more common among obese individuals 4 , 5 and slightly lower among Latino- and Asian-Americans (1.9% and 2.0%, respectively) than among the general population. 6 , 7 BED is typically first diagnosed in young adulthood (early to mid-20s); 8 , 9 symptoms often persist well beyond midlife. 10 – 12

The prevalence of LOC eating is unknown. In postbariatric surgery patients, it may be as high as 25 percent. 13 , 14 In children at risk for adult obesity because of either their own overweight or that of their parents, prevalence may be as high as 32 percent. 15

- Current Challenges and Controversies in Diagnosing These Disorders

In diagnosing BED, assessing whether a patient is eating an atypically large amount of food is not wholly quantitative; it requires the clinician’s evaluation of the patient’s self-report. Assessment by a structured clinical interview is considered the gold standard. We included only studies in which participants were identified as meeting DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria for BED as determined through a structured interview.

Assessing BED and LOC in children poses unique challenges, in part because neither the DSM-IV nor the DSM-5 established a minimum age for a BED diagnosis. As a result, when diagnosing adolescents, some clinicians consider BED criteria and others consider LOC eating criteria. We included studies of LOC eating in children ages 6–17 years.

In the postbariatric surgery circumstance, defining LOC eating is not straightforward; assessment methods are not standardized. Patients may report their disordered eating behaviors as a general subjective sense of lack of control over their eating rather than in terms of specific overconsumption based on the amount of food. Also, LOC eating may manifest in the consumption of food types and patterns of intake that are contraindicated after surgery.

- Current Challenges and Controversies in Treating These Disorders

Treating patients with BED targets the core behavioral features (binge eating) and psychological features (i.e., eating, weight, and shape concerns, and distress) of this condition. Other important targets of treatment include metabolic health (in patients who are obese, have diabetes, or both) and mood regulation (e.g., in patients with coexisting depression or anxiety). Table B describes commonly used approaches. Treatments for LOC eating for postbariatric surgery patients and children reflect BED treatment options; treatment of children may include a role for parents.

Treatments commonly used for binge-eating disorder.

- Scope and Key Questions

This review addresses the efficacy and effectiveness of interventions for individuals meeting DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria for BED, for postbariatric surgery patients with LOC eating, and for children with LOC eating. (Hereafter, the term “effectiveness” refers to both efficacy and effectiveness, including comparative effectiveness.) We also attempted to examine whether treatment effectiveness differed in subgroups based on sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, body mass index (BMI), duration of illness, or coexisting conditions.

Broadly, we included pharmacological, psychological, behavioral, and combination interventions. We considered physical and psychological health outcomes in four major categories: (1) binge behavior (binge eating or LOC eating); (2) binge-eating–related psychopathology (e.g., weight and shape concerns, dietary restraint); (3) physical health functioning (i.e., weight and other indexes of metabolic health—e.g., diabetes); and (4) general psychopathology (e.g., depression, anxiety). Additional outcomes of interest included social and occupational functioning and harms of treatment.

We also examined the course of illness of BED and of LOC eating, particularly given their relatively high comorbidity with other medical and psychiatric conditions. In addition, clinical interest in understanding whether LOC eating reliably predicts poorer weight outcomes and new-onset BED over time is considerable. Little is known about the temporal stability of BED in the community generally, and of LOC in postbariatric surgery patients and children specifically.

Ultimately, the information produced in this review is intended to contribute to improved care for patients, better decisionmaking capacity for clinicians, and more sophisticated policies from those responsible for establishing treatment guidelines or making various insurance and related decisions.

Key Questions

We addressed 15 Key Questions (KQs). Nine are about effectiveness of treatment (benefits and harms overall and benefits for various patient subgroups)—three for BED, three for LOC eating among bariatric surgery patients, and three for LOC eating among children. The other six KQs deal with course of illness, overall and for various subgroups, for BED or LOC eating.

What is the evidence for the effectiveness of treatments or combinations of treatments for binge-eating disorder?

What is the evidence for harms associated with treatments for binge-eating disorder?

Does the effectiveness of treatments for binge-eating disorder differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, initial body mass index, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions?

What is the course of illness of binge-eating disorder?

Does the course of illness of binge-eating disorder differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, body mass index, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions?

What is the evidence for the effectiveness of treatments or combinations of treatments for loss-of-control eating among bariatric surgery patients?

What is the evidence for harms associated with treatments for loss-of-control eating among bariatric surgery patients?

Does the effectiveness of treatments for loss-of-control eating among bariatric surgery patients differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, initial body mass index, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions?

What is the course of illness of loss-of-control eating among bariatric surgery patients?

Does the course of illness of loss-of-control eating among bariatric surgery patients differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, initial body mass index, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions?

What is the evidence for the effectiveness of treatments or combinations of treatments for loss-of-control eating among children?

What is the evidence for harms associated with treatments for loss-of-control eating among children?

Does the effectiveness of treatments for loss-of-control eating among children differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, initial body mass index, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions?

What is the course of illness of loss-of-control eating among children?

Does the course of illness of loss-of-control eating among children differ by age, sex, race, ethnicity, initial body mass index, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions?

Analytic Frameworks

The relationships among the patient populations, interventions, comparators, and outcomes are depicted for each treatment KQ in Figure A and for each course-of-illness KQ in Figure B .

Analytic framework for binge-eating disorder and loss-of-control eating: effectiveness and harms of interventions. BMI = body mass index; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; KQ = Key Question

Analytic framework for binge-eating disorder and loss-of-control eating: course of illness (outcomes of the disorders). BMI = body mass index; GERD = gastroesophageal reflux disease; KQ = Key Question

Topic Refinement and Protocol Review

This topic and its KQs were developed through a public process. The Binge-Eating Disorder Association nominated the topic. The RTI International–University of North Carolina Evidence-based Practice Center (EPC) further developed and refined the topic with input from Key Informants in the field. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) posted provisional KQs for public comment on January 13, 2014. We incorporated public comments and guidance from a Technical Expert Panel into the final research protocol (posted on the AHRQ Web site on April 4, 2014).

Literature Search Strategy

Search strategy.

We conducted focused searches of MEDLINE ® (via PubMed ® ), Embase ® , CINAHL (nursing and allied health database), Academic OneFile, and the Cochrane Library. An experienced research librarian used a predefined list of search terms and medical subject headings. The librarian completed the searches for the draft report on June 23, 2014; she conducted a second (update) search on January 19, 2015, during peer review.

We searched for relevant unpublished and gray literature, including trial registries, specifically ClinicalTrials.gov and Health Services Research Projects in Progress. AHRQ requested Scientific Information Packets (SIPs) from the developers and distributors of interventions identified in the literature review. We also requested Technical Expert Panel members’ and Peer Reviewers’ recommendations of additional published, unpublished, and gray literature not identified by the review team. We included unpublished studies that met all inclusion criteria and contained enough information on their research methods to permit us to make a standard risk-of-bias assessment of individual studies. This could include, but was not limited to, conference posters and proceedings, studies posted on the Web site ClinicalTrials.gov, and U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) medication approval packages. We included unpublished studies that met all inclusion criteria and contained enough information to permit us to make a standard risk-of-bias assessment. We searched reference lists of pertinent review articles for studies that we should consider for inclusion in this review, including our earlier review on this topic. 16 – 18

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We developed inclusion and exclusion criteria with a framework in mind that considered the relationship among the patient populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes, timing of outcome assessments, and settings (PICOTS). We considered only trials or studies written in English; additional evidence possibly available in non–English-language studies that had an abstract in English is also discussed.

The populations of interest are (1) individuals meeting DSM-IV or DSM-5 criteria for BED, (2) postbariatric surgery patients with LOC eating, and (3) children with LOC eating. We excluded studies of individuals with co-occurring anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa and studies of children younger than 6 years of age. We excluded trials with fewer than 10 participants and nonrandomized studies with fewer than 50 participants.

Treatments of interest include pharmacological interventions (e.g., antidepressants, anticonvulsants, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD] medications, and weight loss medications) and interventions that combine various psychological and behavioral techniques and principles to varying degrees (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT], interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT], behavioral weight loss [BWL], dialectical behavioral therapy [DBT], and psychodynamic interpersonal therapy [PIPT]). We sought evidence on complementary and alternative medicine treatments but did not find any, and such interventions are not further discussed. Treatment combinations could involve psychological and behavioral interventions or psychological and behavioral with pharmacological interventions. Included studies had to have at least two groups. Acceptable comparisons included one of the other treatment comparisons, placebo, nonintervention, wait-list controls, or treatment as usual.

For psychological and behavioral interventions, we evaluated evidence by modality separately: individual and group therapy, and therapist-led and self-help approaches. The modalities involve a different therapist-patient relationship and level of health care resources; and only group therapy includes the influence of other patients suffering from the condition in the therapeutic process.

We specified a broad range of outcomes—intermediate and final health benefit outcomes and treatment harms ( Figures A and B ). We analyzed five groups of treatment effectiveness and course-of-illness outcomes: binge-eating outcomes, eating-related psychopathology outcomes, weight-related outcomes, general psychological outcomes (e.g., depression), and other (e.g., quality of life). Potential harms (also a broad range of minor to severe side effects or adverse events) varied across intervention types. Outcome differences for subgroups were evaluated for both treatment effectiveness and course of illness. We reported treatment outcomes at the end of treatment or later, but course-of-illness studies had a 1-year minimum followup from the diagnosis.

We included studies with inpatient or outpatient settings. We did not exclude studies based on geography.

Study designs included meta-analyses, systematic reviews, randomized controlled trials (RCTs), nonrandomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies, and case-control studies. We counted systematic reviews only if they provided information used in the evidence synthesis.

Study Selection

Trained members of the research team reviewed article abstracts and full-text articles. Two members independently reviewed each title and abstract using the predefined inclusion and exclusion criteria. Studies marked for possible inclusion by either reviewer underwent a full-text review. Two members of the team independently reviewed each full-text article. If both reviewers agreed that a study did not meet the eligibility criteria, it was excluded; each reviewer recorded the primary reason for exclusion. If reviewers disagreed, they resolved conflicts by discussion and consensus or by consulting a third member of the review team. We screened unpublished studies and reviewed SIPs using the same title/abstract and full-text review processes. The project coordinator tracked abstract and full-text reviews in an EndNote database (EndNote ® X4).

Data Abstraction

We developed a template for evidence tables using the PICOTS framework and abstracted relevant information into the tables using Microsoft Excel. We recorded characteristics of study populations, interventions, comparators, settings, study designs, methods, and results. Six trained members of the team participated in the data abstraction. One reviewer initially abstracted the relevant data from each included article; a second more senior member of the team reviewed each data abstraction against the original article for completeness and accuracy.

Risk-of-Bias Assessment

We assessed risk of bias with three appropriate tools, described in more detail in the full report: (1) one for judging trials based on the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for RCTs and summary judgments corresponding with EPC guidance; (2) one for evaluating risk of bias in non-RCTs and observational studies (modified from 2 existing tools); and (3) AMSTAR (A Measurement Tool To Assess Systematic Reviews) for assessing the quality of a systematic review. Two independent reviewers rated the risk of bias for each study. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus or by consulting a third member of the team.

Risk of bias is reported as a rating of low, medium, or high. RCTs with a high risk of bias are those with at least one major issue that has the potential to cause significant bias and thus might invalidate its results; such flaws include different application of inclusion/exclusion criteria between arms, substantial differences in arms at baseline, high overall attrition, differential attrition across arms that is not adequately addressed through analytic methods, or lack of control for concurrent treatment. An RCT may be evaluated as medium risk of bias, in contrast to low risk of bias, if the study does not have an obvious source of significant bias but, while it is unlikely that the study is biased because of the reported conduct in relation to other aspects of the trial, information on multiple bias criteria is unclear because of gaps in reporting. A key consideration in evaluating the risk of bias of cohort and case-control studies (only for our course-of-illness analyses) was control for critical potential confounding through design or statistical analyses. If critical information for making that assessment was not reported or was unclear, or if the conduct or analysis was severely flawed, we rated the study as high risk of bias.

To maintain a focus on interpretable evidence, we opted generally not to use trials with a high risk of bias in synthesizing treatment benefits. However, we did consider studies with high risk of bias in sensitivity analyses of our meta-analyses of treatment benefits and as allowable evidence for both treatment harms and course of illness.

Data Synthesis

For quantitative synthesis (meta-analyses to estimate overall effect sizes using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis, version 3.2), we had sufficiently similar evidence for placebo-controlled trials of second-generation antidepressants and lisdexamfetamine and for wait-list–controlled trials of therapist-led CBT. We did all other analyses qualitatively, based on our reasoned judgment of similarities in measurement of interventions and outcomes, and homogeneity of patient populations.

Strength of the Body of Evidence

We graded the strength of evidence based on the “Methods Guide for Effectiveness and Comparative Effectiveness Reviews.” 19 This EPC approach incorporates five key domains: study limitations, directness, consistency, precision of the evidence, and reporting bias. Reviewers may also consider three optional domains if relevant to the evidence: increasing dose response, large magnitude of effect, and an effect that would have been larger if confounding variables had not been controlled for in the analysis.

Grades reflect the strength of the body of evidence to answer each KQ. A grade of high strength of evidence indicates that we have high confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect. Moderate strength of evidence indicates that we have moderate confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect. Low strength of evidence suggests that we have low confidence that the evidence reflects the true effect. Insufficient evidence signifies that the evidence is not available, that we are unable to estimate an effect, or that we have no confidence in the estimate of the effect.

Two reviewers assessed each domain independently and also assigned an overall grade for comparisons for each key outcome; they resolved any conflicts through consensus discussion. If they did not reach consensus, the team brought in a third party to settle the conflict.

Applicability

We assessed the applicability both of individual studies and of the body of evidence. For individual studies, we examined factors that may limit applicability (e.g., characteristics of populations, interventions, or comparators). Such factors may lessen our ability to generalize the effectiveness of an intervention for use in everyday practice. We abstracted key characteristics of applicability into evidence tables. During data synthesis, we assessed the applicability of the body of evidence using the abstracted characteristics.

Peer Review and Public Commentary

Experts in BED and LOC eating, specifically clinicians and researchers specializing in pharmacotherapy treatment, psychotherapy and behavioral treatment, pediatrics, and evidence-based interventions, were invited to provide external peer review of the draft review. AHRQ staff (Task Order Officer and EPC Program Director) and an Associate Editor also provided comments. Associate Editors are leaders in their fields who are also actively involved as directors or leaders at their EPC. The draft report was posted on the AHRQ Web site for 4 weeks to elicit public comment. We responded to all reviewer comments and noted any resulting revisions to the text in the Disposition of Comments Report. This disposition report will be made available 3 months after AHRQ posts the final review on its Web site.

We report results by KQ, grouped basically by intervention comparison (for treatment effectiveness and harms). We cover BED, LOC eating, and then course-of-illness findings in that order. Tables C–E summarize key findings and strength-of-evidence grades. The full report contains summary tables for results. Appendix D of the full report documents risk-of-bias assessments; Appendix E presents evidence tables for all included studies.

Literature Searches

Figure C , a PRISMA [Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses] diagram, depicts our literature search results. We identified a total of 4,395 unduplicated citations and determined that 918 met criteria for full-text review. We excluded 809 full-text articles based on our inclusion criteria and retained 105 articles reporting on a total of 83 trials or studies and 1 systematic review. Because we used some abstractions from our 2006 systematic review on eating disorders to develop some BED treatment and course-of-illness results, we consider that review as included evidence. 16 – 18 However, we reevaluated the risk of bias for all earlier included studies because we updated our assessment tools.

PRISMA diagram for binge-eating disorder treatment and course of illness. AHRQ = Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; KQ = Key Question; PRISMA = Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses a Three studies (3 articles) also (more...)

We did not use 19 studies in our main analyses of treatment benefits because of their high risk of bias. In keeping with standard approaches, however, we included one of these studies, which compared an antidepressant medication with placebo, in sensitivity analysis of our meta-analysis findings. 20 This was the only study with high risk of bias that reported on a treatment comparison that we evaluated through meta-analysis. We also used seven of the studies with high risk of bias in our assessment of treatment harms. 20 – 26

We used 52 studies (67 articles) in our main analysis of treatment benefits (both BED and LOC eating). Fifteen studies (23 articles) met inclusion criteria for course-of-illness KQs. We used all 15 studies in that evidence synthesis, regardless of our risk-of-bias rating for the study.

Of the 20 fair- or good-quality studies on treatment for BED from our previous systematic review, 19 trials met the inclusion criteria for this review. One study was excluded because it used sibutramine, a treatment method no longer available in the United States. 27 Four studies 20 , 24 , 28 , 29 that we had rated as good or fair quality for the earlier review were newly rated as high risk of bias; we omitted them, therefore, from our main analyses. The earlier review also included three studies on BED course of illness that we have used here. 30 – 32

Key Question 1. Effectiveness of Interventions for Binge-Eating Disorder

For treatment effectiveness for BED, we address three broad categories of treatment: pharmacological, psychological or behavioral, and combination treatments.

For medications, the 18 included trials involved second-generation antidepressants, anticonvulsants, ADHD medications, an antiobesity drug, and a variety of other agents, including one dietary supplement. Among the antidepressants were several selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and several agents that primarily inhibit norepinephrine reuptake (i.e., norepinephrine-dopamine reuptake inhibitor [NDRI] or selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor [SNRI]). Among the ADHD medications were lisdexamfetamine and atomoxetine.

In the category of psychological and behavioral treatments, the 23 included trials involved CBT, DBT, IPT, BWL, PIPT, and inpatient treatment.

Seven trials provided data on combination treatments, including pairings of CBT, BWL, hypocaloric diet, and diet counseling with either an antidepressant or an antiobesity medication. Two of the seven trials paired compound nonpharmacotherapy treatments (i.e., CBT plus BWL, CBT plus diet counseling) with an antidepressant. All trials testing a combination psychological plus pharmacological treatment arm also included a comparable combination placebo-controlled treatment arm (e.g., CBT plus antidepressant compared with CBT plus placebo).

Given the variability in outcome reporting and treatment comparisons, we were able to conduct meta-analyses only to measure the effectiveness on several outcomes of antidepressant treatments, as a class, compared with placebo; lisdexamfetamine compared with placebo; and therapist-led CBT compared with wait-list.

Pharmacological Interventions: Antidepressants Compared With Placebo

Eight RCTs (all placebo controlled) examined the effectiveness of antidepressants for treating BED patients. Of these, six involved an SSRI, 33 – 38 and one each involved an NDRI 39 or an SNRI. 40 In the six SSRI trials, two studied fluoxetine, 33 , 34 and one each studied citalopram, 38 escitalopram, 35 fluvoxamine, 36 and sertraline. 37 Assessments were conducted at the end of treatment.

As a class, antidepressants were associated with better binge-eating outcomes than placebo: abstinence (high strength of evidence for benefit), reduction in frequency of binge episodes per week (high strength of evidence for benefit), and reduction in binge days per week (moderate strength of evidence for benefit). Antidepressants were also associated with greater reductions in eating-related obsessions and compulsions (moderate strength of evidence for benefit). Weight reductions and BMI reductions were no greater with antidepressants (for both outcomes, low strength of evidence for no difference). Lastly, antidepressants were associated with greater reductions in symptoms of depression (low strength of evidence for benefit). The evidence was insufficient to evaluate outcomes for any specific antidepressant medication.

Pharmacological Interventions: Antidepressants Compared With Other Active Interventions

One trial involved a head-to-head comparison of two second-generation antidepressants (fluoxetine and sertraline). 41 The evidence was insufficient for concluding anything about treatment superiority.

Pharmacological Interventions: Anticonvulsants Compared With Placebo

Three placebo-controlled RCTs provided evidence about treating BED patients with anticonvulsants; two involved topiramate 42 , 43 and one lamotrigine. 44 Topiramate was associated with abstinence among a greater percentage of participants and with greater reductions in binge eating, obsessions and compulsions related to binge-eating, and weight (moderate strength of evidence for benefit); it also produced greater increases in cognitive restraint and reductions in hunger, disinhibition, and impulsivity (low strength of evidence for benefit). The evidence on the efficacy of lamotrigine was limited to one small trial (insufficient strength of evidence).

Pharmacological Interventions: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Medications Compared With Placebo

The included evidence consisted of four placebo-controlled RCTs of pharmacological interventions that were originally formulated for ADHD and were now being tested for treating patients with BED. One trial investigated the norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor atomoxetine, 45 which has been associated with weight loss; the other three studied the stimulant lisdexamfetamine. 46 The effectiveness of atomoxetine was examined in one small RCT (insufficient strength of evidence). Based on evidence from three RCTs, lisdexamfetamine was associated with abstinence among a greater percentage of participants, greater reductions in binge episodes per week, decreased eating-related obsessions and compulsions, and greater reductions in weight (high strength of evidence for all of these outcomes). Depression measures were not consistently reported across the three studies; one of the studies found no difference from placebo (insufficient strength of evidence). Recently, lisdexamfetamine became the first medication approved by the FDA for treating BED patients. 47

Pharmacological Interventions: Other Medications Compared With Placebo

Three placebo-controlled RCTs dealt with other pharmacological interventions. One trial each investigated the following: the sulfonic acid acamprosate, which is a mixed GABA A receptor agonist/NMDA receptor antagonist; 48 the μ-opioid antagonist ALKS-33 (also known as samidorphan); 49 and the dietary supplement chromium picolinate. 50 The strength of evidence is insufficient to determine effectiveness of any of these treatments because each was studied in a single, small sample trial.

Behavioral Interventions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Compared With No or Limited Intervention

CBT can be delivered in various formats; approaches include therapist-led, partially therapist-led, and self-help strategies (i.e., structured, guided, and pure). The two therapist-led approaches can involve either individual sessions (one-on-one) or group sessions.

Nine trials compared CBT with limited or no intervention. 51 – 59 Of 12 comparisons (in 7 separate trials) involving CBT and wait-list controls, 5 involved therapist-led CBT, 51 – 55 2 involved partially therapist-led CBT, 54 , 55 2 used structured self-help CBT, 54 , 55 2 used guided self-help CBT including one Internet-based guide 56 and one in-person guide, 57 and 1 used pure self-help CBT. 57 Two wait-list trials delivered CBT in an individual format 56 , 57 and five delivered CBT in a group format. 51 – 55

Therapist-led CBT was related to various improved outcomes, including abstinence, binge frequency, and eating-related psychopathology (high strength of evidence for all outcomes). In contrast, reductions in BMI and symptoms of depression were not greater (both moderate strength of evidence for no difference). Similarly, partially therapist-led CBT was related to a greater likelihood of abstinence and reduced binge frequency (both low strength of evidence), but reductions in BMI and symptoms of depression were not greater (both low strength of evidence for no difference). Structured self-help was associated with reduced binge frequency (low strength of evidence) but no greater reduction in BMI or symptoms of depression (low strength of evidence for no difference).

Five small RCTs examined the effectiveness of guided or pure self-help CBT, but they differed in delivery format or comparator, and therefore evidence was insufficient for all comparisons and outcomes.

Behavioral Interventions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Compared With Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Variants

Seven trials compared CBT delivered in one format with CBT delivered in a different format. 54 , 55 , 57 , 60 – 63 Variations across trials resulted in four therapist-led comparisons: exposure versus cognitive restructuring, 60 CBT alone versus CBT plus ecological momentary assessment, 61 individual versus group, 62 and fully therapist-led versus partially therapist-led interventions. 54 , 55 , 63 Several self-help comparisons were also tested: one for guided self-help versus pure self-help 57 and two for therapist-led versus structured self-help. 54 , 63

Only three of these comparisons were replicated in more than one trial. Binge-eating outcomes did not differ across comparisons of variations in therapist-led CBT, with one exception favoring therapist-led over structured self-help in one trial (low strength of evidence for no difference). BMI and depression outcomes did not differ across types of CBT (both moderate strength of evidence for no difference).

Behavioral Interventions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Compared With Behavioral Weight Loss

Four trials compared CBT with BWL approaches; 59 , 64 – 66 one also compared CBT and BWL (separately) with CBT plus BWL. 65 The CBT format varied across trials and included both therapist-led 64 , 65 and guided self-help. 59 , 66 For comparisons with therapist-led CBT, results were mixed. Binge frequency was lower in the therapist-led CBT arm (low strength of evidence), and BMI reduction was greater in the BWL arm at the end of treatment (moderate strength of evidence); the groups did not differ with respect to abstinence, eating-related psychopathology, or depression outcomes (low strength of evidence for no difference). Evidence on comparisons with guided self-help was insufficient because all comparisons were limited to single, small trials.

Behavioral Interventions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Compared With Interpersonal Therapy

Three trials compared CBT with interpersonal therapy strategies in treating patients with BED. 51 , 66 , 67 Two trials compared therapist-led IPT with either therapist-led CBT 68 or guided self-help CBT. 66 Another trial compared therapist-led CBT with therapist-led PIPT. 51 Because trials differed in the intervention types that were compared, we could not synthesize results across trials (insufficient strength of evidence for all outcomes).

Behavioral Interventions: Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Combined With Diet or Weight-Loss Interventions

Three trials examined the use of CBT plus additional interventions involving either diet or weight-loss strategies (or both) in treating patients with BED. These involved two trials comparing CBT alone with CBT plus a diet or weight-loss intervention 65 , 69 and a single trial comparing CBT plus a low-energy dense diet with CBT plus general nutritional counseling. No significant differences were found for virtually any outcomes (insufficient strength of evidence in all cases).

Behavioral Interventions: Behavioral Weight Loss

Two trials tested BWL interventions for BED patients. These compared guided self-help BWL with an active control 59 and therapist-led BWL with therapist-led IPT. 66 Strength of evidence was insufficient because each comparison was limited to one small trial.

Behavioral Interventions: Psychodynamic Interpersonal Therapy Versus Wait-List

One small trial examined the effectiveness of therapist-led group PIPT. 51 Strength of evidence was insufficient for all outcomes.

Behavioral Interventions: Dialectical Behavioral Therapy

One trial evaluated therapist-led DBT against therapist-led active comparison-group therapy (insufficient strength of evidence for all outcomes). 70 – 72

Behavioral Interventions: Inpatient Treatment Versus Inpatient Treatment Plus Active Therapies

Three trials examined treatment in an inpatient setting. 73 – 75 In each trial, patients received a standard inpatient care program and were randomized to additional active therapies. Two trials used virtual reality treatments that aimed to reduce body image distortions and food-related anxiety. However, these trials differed in several ways, so results were all based on single, small studies (insufficient strength of evidence for all outcomes).

Pharmacological Interventions: Combination Treatments Compared With Placebo and With Other Treatments

Evidence about combination interventions came from seven placebo-controlled RCTs. In all seven trials, investigators combined a medication with a psychological treatment; in two, they combined a medication with two psychological treatments. 34 , 76 Three trials used an antidepressant; 34 , 76 , 77 one, an anticonvulsant; 78 and three, an antiobesity agent. 79 – 81 The psychological interventions included CBT in three trials, 34 , 78 , 80 BWL in one trial, 80 CBT plus BWL in one trial, 77 hypocaloric diet in one trial, 81 and group psychological support plus diet counseling in one trial. 76 The strength of evidence was insufficient to reach a conclusion concerning the effectiveness of any specific combination treatment because each combination was studied only in a single, small trial.

Key Question 2. Harms Associated With Treatments or Combinations of Treatments for Binge-Eating Disorder

Virtually all harms were limited to pharmacotherapy intervention trials (reported in 33 trials). Harms associated with treating BED patients and discontinuations from studies attributable to harms occurred approximately twice as often in patients receiving pharmacotherapy as in those receiving placebo. The number of serious adverse events was extremely low. Topiramate was associated with a significantly higher number of events involving sympathetic nervous system arousal (e.g., sweating, dry mouth, rapid heart rate) and “other” events (moderate strength of evidence), as well as a higher number of events related to sleep disturbance (low strength of evidence). Fluvoxamine was associated with greater gastrointestinal (GI) upset and sleep disturbances (low strength of evidence). Lisdexamfetamine was associated with a significantly higher likelihood of insomnia and headache (high strength of evidence), as well as greater GI upset, central nervous system arousal, and decreased appetite (moderate strength of evidence).

Key Questions 6 and 7. Effectiveness of Interventions (and Harms From Interventions) for Loss-of-Control Eating in Bariatric Surgery Patients

We found no evidence meeting our inclusion criteria that examined treatments or combinations of treatments for LOC eating among bariatric surgery patients.

Key Questions 11 and 12. Effectiveness of Interventions (and Harms From Interventions) for Loss-of-Control Eating in Children

Four small trials examined behavioral interventions for children with LOC eating. 82 – 85 One trial was a pilot for a larger trial by the same investigator group. The trials differed in the age range of participants (adolescents only or both adolescents and younger children), the definition of LOC eating that the investigators used to determine participant eligibility, treatment comparisons, and measures used to evaluate binge outcomes. With the exception of weight (low strength of evidence for no difference), strength of evidence was insufficient across all outcomes.

Key Questions 3, 8, and 13. Differences in the Effectiveness of Treatments or Combinations of Treatments for Subgroups

We found no evidence on differences by age, sex, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, initial BMI, duration of illness, or coexisting conditions in any of our three populations of interest: patients with binge-eating disorder, bariatric surgery patients with LOC eating, and children with LOC eating.

Key Question 4. Course of Illness Among Individuals With Binge-Eating Disorder