What is a Conceptual Framework?

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format.

Updated on August 28, 2023

What are frameworks in research?

Both theoretical and conceptual frameworks have a significant role in research. Frameworks are essential to bridge the gaps in research. They aid in clearly setting the goals, priorities, relationship between variables. Frameworks in research particularly help in chalking clear process details.

Theoretical frameworks largely work at the time when a theoretical roadmap has been laid about a certain topic and the research being undertaken by the researcher, carefully analyzes it, and works on similar lines to attain successful results.

It varies from a conceptual framework in terms of the preliminary work required to construct it. Though a conceptual framework is part of the theoretical framework in a larger sense, yet there are variations between them.

The following sections delve deeper into the characteristics of conceptual frameworks. This article will provide insight into constructing a concise, complete, and research-friendly conceptual framework for your project.

Definition of a conceptual framework

True research begins with setting empirical goals. Goals aid in presenting successful answers to the research questions at hand. It delineates a process wherein different aspects of the research are reflected upon, and coherence is established among them.

A conceptual framework is an underrated methodological approach that should be paid attention to before embarking on a research journey in any field, be it science, finance, history, psychology, etc.

A conceptual framework sets forth the standards to define a research question and find appropriate, meaningful answers for the same. It connects the theories, assumptions, beliefs, and concepts behind your research and presents them in a pictorial, graphical, or narrative format. Your conceptual framework establishes a link between the dependent and independent variables, factors, and other ideologies affecting the structure of your research.

A critical facet a conceptual framework unveils is the relationship the researchers have with their research. It closely highlights the factors that play an instrumental role in decision-making, variable selection, data collection, assessment of results, and formulation of new theories.

Consequently, if you, the researcher, are at the forefront of your research battlefield, your conceptual framework is the most powerful arsenal in your pocket.

What should be included in a conceptual framework?

A conceptual framework includes the key process parameters, defining variables, and cause-and-effect relationships. To add to this, the primary focus while developing a conceptual framework should remain on the quality of questions being raised and addressed through the framework. This will not only ease the process of initiation, but also enable you to draw meaningful conclusions from the same.

A practical and advantageous approach involves selecting models and analyzing literature that is unconventional and not directly related to the topic. This helps the researcher design an illustrative framework that is multidisciplinary and simultaneously looks at a diverse range of phenomena. It also emboldens the roots of exploratory research.

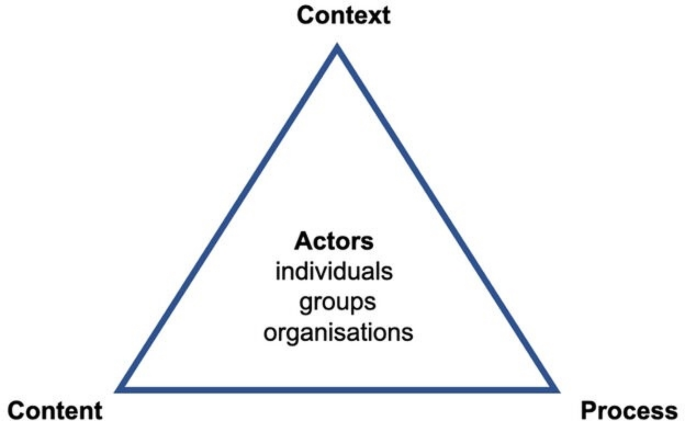

Fig. 1: Components of a conceptual framework

How to make a conceptual framework

The successful design of a conceptual framework includes:

- Selecting the appropriate research questions

- Defining the process variables (dependent, independent, and others)

- Determining the cause-and-effect relationships

This analytical tool begins with defining the most suitable set of questions that the research wishes to answer upon its conclusion. Following this, the different variety of variables is categorized. Lastly, the collected data is subjected to rigorous data analysis. Final results are compiled to establish links between the variables.

The variables drawn inside frames impact the overall quality of the research. If the framework involves arrows, it suggests correlational linkages among the variables. Lines, on the other hand, suggest that no significant correlation exists among them. Henceforth, the utilization of lines and arrows should be done taking into cognizance the meaning they both imply.

Example of a conceptual framework

To provide an idea about a conceptual framework, let’s examine the example of drug development research.

Say a new drug moiety A has to be launched in the market. For that, the baseline research begins with selecting the appropriate drug molecule. This is important because it:

- Provides the data for molecular docking studies to identify suitable target proteins

- Performs in vitro (a process taking place outside a living organism) and in vivo (a process taking place inside a living organism) analyzes

This assists in the screening of the molecules and a final selection leading to the most suitable target molecule. In this case, the choice of the drug molecule is an independent variable whereas, all the others, targets from molecular docking studies, and results from in vitro and in vivo analyses are dependent variables.

The outcomes revealed by the studies might be coherent or incoherent with the literature. In any case, an accurately designed conceptual framework will efficiently establish the cause-and-effect relationship and explain both perspectives satisfactorily.

If A has been chosen to be launched in the market, the conceptual framework will point towards the factors that have led to its selection. If A does not make it to the market, the key elements which did not work in its favor can be pinpointed by an accurate analysis of the conceptual framework.

Fig. 2: Concise example of a conceptual framework

Important takeaways

While conceptual frameworks are a great way of designing the research protocol, they might consist of some unforeseen loopholes. A review of the literature can sometimes provide a false impression of the collection of work done worldwide while in actuality, there might be research that is being undertaken on the same topic but is still under publication or review. Strong conceptual frameworks, therefore, are designed when all these aspects are taken into consideration and the researchers indulge in discussions with others working on similar grounds of research.

Conceptual frameworks may also sometimes lead to collecting and reviewing data that is not so relevant to the current research topic. The researchers must always be on the lookout for studies that are highly relevant to their topic of work and will be of impact if taken into consideration.

Another common practice associated with conceptual frameworks is their classification as merely descriptive qualitative tools and not actually a concrete build-up of ideas and critically analyzed literature and data which it is, in reality. Ideal conceptual frameworks always bring out their own set of new ideas after analysis of literature rather than simply depending on facts being already reported by other research groups.

So, the next time you set out to construct your conceptual framework or improvise on your previous one, be wary that concepts for your research are ideas that need to be worked upon. They are not simply a collection of literature from the previous research.

Final thoughts

Research is witnessing a boom in the methodical approaches being applied to it nowadays. In contrast to conventional research, researchers today are always looking for better techniques and methods to improve the quality of their research.

We strongly believe in the ideals of research that are not merely academic, but all-inclusive. We strongly encourage all our readers and researchers to do work that impacts society. Designing strong conceptual frameworks is an integral part of the process. It gives headway for systematic, empirical, and fruitful research.

Vridhi Sachdeva, MPharm

See our "Privacy Policy"

Get an overall assessment of the main focus of your study from AJE

Our Presubmission Review service will provide recommendations on the structure, organization, and the overall presentation of your research manuscript.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and Examples

Conceptual Framework – Types, Methodology and Examples

Table of Contents

Conceptual Framework

Definition:

A conceptual framework is a structured approach to organizing and understanding complex ideas, theories, or concepts. It provides a systematic and coherent way of thinking about a problem or topic, and helps to guide research or analysis in a particular field.

A conceptual framework typically includes a set of assumptions, concepts, and propositions that form a theoretical framework for understanding a particular phenomenon. It can be used to develop hypotheses, guide empirical research, or provide a framework for evaluating and interpreting data.

Conceptual Framework in Research

In research, a conceptual framework is a theoretical structure that provides a framework for understanding a particular phenomenon or problem. It is a key component of any research project and helps to guide the research process from start to finish.

A conceptual framework provides a clear understanding of the variables, relationships, and assumptions that underpin a research study. It outlines the key concepts that the study is investigating and how they are related to each other. It also defines the scope of the study and sets out the research questions or hypotheses.

Types of Conceptual Framework

Types of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

Theoretical Framework

A theoretical framework is an overarching set of concepts, ideas, and assumptions that help to explain and interpret a phenomenon. It provides a theoretical perspective on the phenomenon being studied and helps researchers to identify the relationships between different concepts. For example, a theoretical framework for a study on the impact of social media on mental health might draw on theories of communication, social influence, and psychological well-being.

Conceptual Model

A conceptual model is a visual or written representation of a complex system or phenomenon. It helps to identify the main components of the system and the relationships between them. For example, a conceptual model for a study on the factors that influence employee turnover might include factors such as job satisfaction, salary, work-life balance, and job security, and the relationships between them.

Empirical Framework

An empirical framework is based on empirical data and helps to explain a particular phenomenon. It involves collecting data, analyzing it, and developing a framework to explain the results. For example, an empirical framework for a study on the impact of a new health intervention might involve collecting data on the intervention’s effectiveness, cost, and acceptability to patients.

Descriptive Framework

A descriptive framework is used to describe a particular phenomenon. It helps to identify the main characteristics of the phenomenon and to develop a vocabulary to describe it. For example, a descriptive framework for a study on different types of musical genres might include descriptions of the instruments used, the rhythms and beats, the vocal styles, and the cultural contexts of each genre.

Analytical Framework

An analytical framework is used to analyze a particular phenomenon. It involves breaking down the phenomenon into its constituent parts and analyzing them separately. This type of framework is often used in social science research. For example, an analytical framework for a study on the impact of race on police brutality might involve analyzing the historical and cultural factors that contribute to racial bias, the organizational factors that influence police behavior, and the psychological factors that influence individual officers’ behavior.

Conceptual Framework for Policy Analysis

A conceptual framework for policy analysis is used to guide the development of policies or programs. It helps policymakers to identify the key issues and to develop strategies to address them. For example, a conceptual framework for a policy analysis on climate change might involve identifying the key stakeholders, assessing their interests and concerns, and developing policy options to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

Logical Frameworks

Logical frameworks are used to plan and evaluate projects and programs. They provide a structured approach to identifying project goals, objectives, and outcomes, and help to ensure that all stakeholders are aligned and working towards the same objectives.

Conceptual Frameworks for Program Evaluation

These frameworks are used to evaluate the effectiveness of programs or interventions. They provide a structure for identifying program goals, objectives, and outcomes, and help to measure the impact of the program on its intended beneficiaries.

Conceptual Frameworks for Organizational Analysis

These frameworks are used to analyze and evaluate organizational structures, processes, and performance. They provide a structured approach to understanding the relationships between different departments, functions, and stakeholders within an organization.

Conceptual Frameworks for Strategic Planning

These frameworks are used to develop and implement strategic plans for organizations or businesses. They help to identify the key factors and stakeholders that will impact the success of the plan, and provide a structure for setting goals, developing strategies, and monitoring progress.

Components of Conceptual Framework

The components of a conceptual framework typically include:

- Research question or problem statement : This component defines the problem or question that the conceptual framework seeks to address. It sets the stage for the development of the framework and guides the selection of the relevant concepts and constructs.

- Concepts : These are the general ideas, principles, or categories that are used to describe and explain the phenomenon or problem under investigation. Concepts provide the building blocks of the framework and help to establish a common language for discussing the issue.

- Constructs : Constructs are the specific variables or concepts that are used to operationalize the general concepts. They are measurable or observable and serve as indicators of the underlying concept.

- Propositions or hypotheses : These are statements that describe the relationships between the concepts or constructs in the framework. They provide a basis for testing the validity of the framework and for generating new insights or theories.

- Assumptions : These are the underlying beliefs or values that shape the framework. They may be explicit or implicit and may influence the selection and interpretation of the concepts and constructs.

- Boundaries : These are the limits or scope of the framework. They define the focus of the investigation and help to clarify what is included and excluded from the analysis.

- Context : This component refers to the broader social, cultural, and historical factors that shape the phenomenon or problem under investigation. It helps to situate the framework within a larger theoretical or empirical context and to identify the relevant variables and factors that may affect the phenomenon.

- Relationships and connections: These are the connections and interrelationships between the different components of the conceptual framework. They describe how the concepts and constructs are linked and how they contribute to the overall understanding of the phenomenon or problem.

- Variables : These are the factors that are being measured or observed in the study. They are often operationalized as constructs and are used to test the propositions or hypotheses.

- Methodology : This component describes the research methods and techniques that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes the sampling strategy, data collection methods, data analysis techniques, and ethical considerations.

- Literature review : This component provides an overview of the existing research and theories related to the phenomenon or problem under investigation. It helps to identify the gaps in the literature and to situate the framework within the broader theoretical and empirical context.

- Outcomes and implications: These are the expected outcomes or implications of the study. They describe the potential contributions of the study to the theoretical and empirical knowledge in the field and the practical implications for policy and practice.

Conceptual Framework Methodology

Conceptual Framework Methodology is a research method that is commonly used in academic and scientific research to develop a theoretical framework for a study. It is a systematic approach that helps researchers to organize their thoughts and ideas, identify the variables that are relevant to their study, and establish the relationships between these variables.

Here are the steps involved in the conceptual framework methodology:

Identify the Research Problem

The first step is to identify the research problem or question that the study aims to answer. This involves identifying the gaps in the existing literature and determining what specific issue the study aims to address.

Conduct a Literature Review

The second step involves conducting a thorough literature review to identify the existing theories, models, and frameworks that are relevant to the research question. This will help the researcher to identify the key concepts and variables that need to be considered in the study.

Define key Concepts and Variables

The next step is to define the key concepts and variables that are relevant to the study. This involves clearly defining the terms used in the study, and identifying the factors that will be measured or observed in the study.

Develop a Theoretical Framework

Once the key concepts and variables have been identified, the researcher can develop a theoretical framework. This involves establishing the relationships between the key concepts and variables, and creating a visual representation of these relationships.

Test the Framework

The final step is to test the theoretical framework using empirical data. This involves collecting and analyzing data to determine whether the relationships between the key concepts and variables that were identified in the framework are accurate and valid.

Examples of Conceptual Framework

Some realtime Examples of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- In economics , the concept of supply and demand is a well-known conceptual framework. It provides a structure for understanding how prices are set in a market, based on the interplay of the quantity of goods supplied by producers and the quantity of goods demanded by consumers.

- In psychology , the cognitive-behavioral framework is a widely used conceptual framework for understanding mental health and illness. It emphasizes the role of thoughts and behaviors in shaping emotions and the importance of cognitive restructuring and behavior change in treatment.

- In sociology , the social determinants of health framework provides a way of understanding how social and economic factors such as income, education, and race influence health outcomes. This framework is widely used in public health research and policy.

- In environmental science , the ecosystem services framework is a way of understanding the benefits that humans derive from natural ecosystems, such as clean air and water, pollination, and carbon storage. This framework is used to guide conservation and land-use decisions.

- In education, the constructivist framework is a way of understanding how learners construct knowledge through active engagement with their environment. This framework is used to guide instructional design and teaching strategies.

Applications of Conceptual Framework

Some of the applications of Conceptual Frameworks are as follows:

- Research : Conceptual frameworks are used in research to guide the design, implementation, and interpretation of studies. Researchers use conceptual frameworks to develop hypotheses, identify research questions, and select appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data.

- Policy: Conceptual frameworks are used in policy-making to guide the development of policies and programs. Policymakers use conceptual frameworks to identify key factors that influence a particular problem or issue, and to develop strategies for addressing them.

- Education : Conceptual frameworks are used in education to guide the design and implementation of instructional strategies and curriculum. Educators use conceptual frameworks to identify learning objectives, select appropriate teaching methods, and assess student learning.

- Management : Conceptual frameworks are used in management to guide decision-making and strategy development. Managers use conceptual frameworks to understand the internal and external factors that influence their organizations, and to develop strategies for achieving their goals.

- Evaluation : Conceptual frameworks are used in evaluation to guide the development of evaluation plans and to interpret evaluation results. Evaluators use conceptual frameworks to identify key outcomes, indicators, and measures, and to develop a logic model for their evaluation.

Purpose of Conceptual Framework

The purpose of a conceptual framework is to provide a theoretical foundation for understanding and analyzing complex phenomena. Conceptual frameworks help to:

- Guide research : Conceptual frameworks provide a framework for researchers to develop hypotheses, identify research questions, and select appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data. By providing a theoretical foundation for research, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that research is rigorous, systematic, and valid.

- Provide clarity: Conceptual frameworks help to provide clarity and structure to complex phenomena by identifying key concepts, relationships, and processes. By providing a clear and systematic understanding of a phenomenon, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that researchers, policymakers, and practitioners are all on the same page when it comes to understanding the issue at hand.

- Inform decision-making : Conceptual frameworks can be used to inform decision-making and strategy development by identifying key factors that influence a particular problem or issue. By understanding the complex interplay of factors that contribute to a particular issue, decision-makers can develop more effective strategies for addressing the problem.

- Facilitate communication : Conceptual frameworks provide a common language and conceptual framework for researchers, policymakers, and practitioners to communicate and collaborate on complex issues. By providing a shared understanding of a phenomenon, conceptual frameworks help to ensure that everyone is working towards the same goal.

When to use Conceptual Framework

There are several situations when it is appropriate to use a conceptual framework:

- To guide the research : A conceptual framework can be used to guide the research process by providing a clear roadmap for the research project. It can help researchers identify key variables and relationships, and develop hypotheses or research questions.

- To clarify concepts : A conceptual framework can be used to clarify and define key concepts and terms used in a research project. It can help ensure that all researchers are using the same language and have a shared understanding of the concepts being studied.

- To provide a theoretical basis: A conceptual framework can provide a theoretical basis for a research project by linking it to existing theories or conceptual models. This can help researchers build on previous research and contribute to the development of a field.

- To identify gaps in knowledge : A conceptual framework can help identify gaps in existing knowledge by highlighting areas that require further research or investigation.

- To communicate findings : A conceptual framework can be used to communicate research findings by providing a clear and concise summary of the key variables, relationships, and assumptions that underpin the research project.

Characteristics of Conceptual Framework

key characteristics of a conceptual framework are:

- Clear definition of key concepts : A conceptual framework should clearly define the key concepts and terms being used in a research project. This ensures that all researchers have a shared understanding of the concepts being studied.

- Identification of key variables: A conceptual framework should identify the key variables that are being studied and how they are related to each other. This helps to organize the research project and provides a clear focus for the study.

- Logical structure: A conceptual framework should have a logical structure that connects the key concepts and variables being studied. This helps to ensure that the research project is coherent and consistent.

- Based on existing theory : A conceptual framework should be based on existing theory or conceptual models. This helps to ensure that the research project is grounded in existing knowledge and builds on previous research.

- Testable hypotheses or research questions: A conceptual framework should include testable hypotheses or research questions that can be answered through empirical research. This helps to ensure that the research project is rigorous and scientifically valid.

- Flexibility : A conceptual framework should be flexible enough to allow for modifications as new information is gathered during the research process. This helps to ensure that the research project is responsive to new findings and is able to adapt to changing circumstances.

Advantages of Conceptual Framework

Advantages of the Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- Clarity : A conceptual framework provides clarity to researchers by outlining the key concepts and variables that are relevant to the research project. This clarity helps researchers to focus on the most important aspects of the research problem and develop a clear plan for investigating it.

- Direction : A conceptual framework provides direction to researchers by helping them to develop hypotheses or research questions that are grounded in existing theory or conceptual models. This direction ensures that the research project is relevant and contributes to the development of the field.

- Efficiency : A conceptual framework can increase efficiency in the research process by providing a structure for organizing ideas and data. This structure can help researchers to avoid redundancies and inconsistencies in their work, saving time and effort.

- Rigor : A conceptual framework can help to ensure the rigor of a research project by providing a theoretical basis for the investigation. This rigor is essential for ensuring that the research project is scientifically valid and produces meaningful results.

- Communication : A conceptual framework can facilitate communication between researchers by providing a shared language and understanding of the key concepts and variables being studied. This communication is essential for collaboration and the advancement of knowledge in the field.

- Generalization : A conceptual framework can help to generalize research findings beyond the specific study by providing a theoretical basis for the investigation. This generalization is essential for the development of knowledge in the field and for informing future research.

Limitations of Conceptual Framework

Limitations of Conceptual Framework are as follows:

- Limited applicability: Conceptual frameworks are often based on existing theory or conceptual models, which may not be applicable to all research problems or contexts. This can limit the usefulness of a conceptual framework in certain situations.

- Lack of empirical support : While a conceptual framework can provide a theoretical basis for a research project, it may not be supported by empirical evidence. This can limit the usefulness of a conceptual framework in guiding empirical research.

- Narrow focus: A conceptual framework can provide a clear focus for a research project, but it may also limit the scope of the investigation. This can make it difficult to address broader research questions or to consider alternative perspectives.

- Over-simplification: A conceptual framework can help to organize and structure research ideas, but it may also over-simplify complex phenomena. This can limit the depth of the investigation and the richness of the data collected.

- Inflexibility : A conceptual framework can provide a structure for organizing research ideas, but it may also be inflexible in the face of new data or unexpected findings. This can limit the ability of researchers to adapt their research project to new information or changing circumstances.

- Difficulty in development : Developing a conceptual framework can be a challenging and time-consuming process. It requires a thorough understanding of existing theory or conceptual models, and may require collaboration with other researchers.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Enhancing Educational Scholarship Through Conceptual Frameworks: A Challenge and Roadmap for Medical Educators

Affiliations.

- 1 Division of Critical Care Medicine, Department of Pediatrics (MW Zackoff),. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Division of General and Community Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics (FJ Real, MD Klein), Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, Cincinnati, Ohio.

- 3 Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, and Department of Healthcare Policy and Research, Weill Cornell Medical Center (EL Abramson), New York, NY.

- 4 Division of Pediatric Hospital Medicine, Department of Pediatrics, University of California, Davis (S-TT Li).

- 5 Department of Medical Education, University of Virginia School of Medicine (ME Gusic), Charlottesville, Va.

- PMID: 30138745

- DOI: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.08.003

Historically, health sciences education has been guided by tradition and teacher preferences rather than by the application of practices supported by rigorous evidence of effectiveness. Although often underutilized, conceptual frameworks-theories that describe the complexities of educational and social phenomenon-are essential foundations for scholarly work in education. Conceptual frameworks provide a lens through which educators can develop research questions, design research studies and educational interventions, assess outcomes, and evaluate the impact of their work. Given this vital role, conceptual frameworks should be considered at the onset of an educational initiative. Use of different conceptual frameworks to address the same topic in medical education may provide distinctive approaches. Exploration of educational issues by employing differing, theory-based approaches advances the field through the identification of the most effective educational methods. Dissemination of sound educational research based on theory is similarly essential to spark future innovation. Ultimately, this rigorous approach to medical education scholarship is necessary to allow us to establish how our educational interventions impact the health and well-being of our patients.

Keywords: conceptual framework; educational research; scholarship.

Copyright © 2018 Academic Pediatric Association. Published by Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Education, Medical / methods*

- Education, Medical / standards

- Evidence-Based Practice / methods*

Advertisement

The instrumental value of conceptual frameworks in educational technology research

- Research Article

- Published: 06 December 2014

- Volume 63 , pages 53–71, ( 2015 )

Cite this article

- Pavlo D. Antonenko 1

4039 Accesses

36 Citations

4 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Scholars from diverse fields and research traditions agree that the conceptual framework is a critically important component of disciplined inquiry. Yet, there is a pronounced lack of shared understanding regarding the definition and functions of conceptual frameworks, which impedes our ability to design effective research and mentor novice researchers. This paper adopts John Dewey’s instrumental view of theory to discuss the prevalent definitions of a conceptual framework, outline its key functions, dispel the popular misconceptions regarding conceptual frameworks, and suggest strategies for developing effective conceptual frameworks and communicating them to the consumers of research. Examples of hypothetical and existing empirical studies in the field of educational technology are used to illustrate the analysis. It is argued in this article that conceptual frameworks should be viewed as an instrument for organizing inquiry and creating a compelling theory-based and data-driven argument for the importance of the problem, rigor of the method, and implications for further development of theory and enhancement of practice.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Social Learning Theory—Albert Bandura

Ethical Considerations of Conducting Systematic Reviews in Educational Research

When Does a Researcher Choose a Quantitative, Qualitative, or Mixed Research Approach?

Anderson, R. C., Nguyen-Jahiel, K., McNurlen, B., Archodidou, A., Kim, S.-Y., Reznitskaya, A., et al. (2001). The snowball phenomenon: Spread of ways of talking and ways of thinking across groups of children. Cognition and Instruction, 19 , 1–46.

Article Google Scholar

Avis, J. (2003). Work-based knowledge, evidence informed practice and education. British Journal of Education Studies, 51 (4), 369–389.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Google Scholar

Barab, S., & Squire, K. (2004). Design-based research: Putting a stake in the ground. The Journal of the Learning Sciences, 13 (1), 1–14.

Becker, H. S. (2007). Writing for social scientists: How to start and finish your thesis, book, or article . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Book Google Scholar

Bruner, J. (1960). The process of education . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Clark, R. E. (1983). Reconsidering research on learning from media. Review of Educational Research, 53 (4), 445–459.

Creswell, J., Plano Clark, V., Gutmann, M., & Hanson, W. (2003). Advanced mixed methods research designs. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social & behavioral research (pp. 209–240). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

De Jong, T., Weinberger, T., Girault, I., Kluge, A., Lazonder, A. W., Pedaste, M., et al. (2012). Using scenarios to design complex technology-enhanced learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 60 (5), 883–901.

DeBacker, T. K., Crowson, H. M., Beesley, A. D., Thoma, S. J., & Hestevold, N. L. (2008). The challenge of measuring epistemic beliefs: An analysis of three self-report instruments. Journal of Experimental Education, 76 , 281–312.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education . New York: Macmillan.

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education . New York: Collier Books.

Ertmer, P. A., Newby, T. J., Liu, W., Tomory, A., Yu, J. H., & Lee, Y. M. (2011). Students’ confidence and perceived value for participating in cross-cultural wiki-based collaborations. Educational Technology Research and Development, 59 , 213–228.

Fodor, J. (1975). The language of thought . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Fredericks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74 , 59–109.

Hannafin, M. J., & Land, S. (1997). The foundations and assumptions of technology-enhanced, student-centered learning environments. Instructional Science, 25 , 167–202.

Heider, F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations . New York: Wiley.

Hofer, B. (2001). Personal epistemology research: Implications for learning and instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 13 (4), 353–382.

Januszewski, A., & Molenda, M. (Eds.). (2007). Educational technology: A definition with commentary . New York: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Johnson, R. B., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2004). Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher, 33 (7), 14–26.

Kaplan, A. (1964). The conduct of inquiry . New York: Harper and Row.

Ke, F. (2008). Computer games application within alternative classroom goal structures: Cognitive, metacognitive, and affective evaluation and interpretation. Educational Technology Research and Development, 56 , 539–556.

Kozma, R. B. (1991). Learning with media. Review of Educational Research, 61 (2), 179–212.

Krajcik, J. S., & Blumenfeld, P. (2006). Project-based learning. In R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Leshem, S., & Trafford, V. N. (2007). Overlooking the conceptual framework. Innovations in Educational and Teaching International, 44 (1), 93–105.

Linn, M. C. (2006). The knowledge integration perspective on learning and instruction. In K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (pp. 243–264). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Margolis, E., & Laurence, S. (2007). The ontology of concepts—abstract objects or mental representations? Nous, 41 (4), 561–593.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2006). Designing qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Maxwell, J. A. (2005). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Maxwell, J. A. (2013). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

McMillan, J. H., & Schumacher, S. (2001). Research in education: A conceptual introduction (5th ed.). New York: Longman.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

National Science Teachers Association (2013). Next Generation Science Standards. Retrieved May 2, 2014, from http://standards.nsta.org/AccessStandardsByTopic.aspx .

Nemirovsky, R., Tierney, C., & Wright, T. (1998). Body motion and graphing. Cognition and Instruction, 16 (2), 119.

Newton, X. A., Poon, R. C., Nunes, N. L., & Stone, E. M. (2013). Research on teacher education programs: Logic model approach. Evaluation and Program Planning, 36 (1), 88–96.

Niederhauser, D. S., Reynolds, R. E., Salmen, D. J., & Skolmoski, P. (2000). The influence of cognitive load on learning from hypertext. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 23 (3), 237–255.

Novak, J. D., & Gowin, D. B. (1984). Learning how to learn . New York: Cambridge University Press.

Orrill, C. H., Hannafin, M. J., & Glazer, E. R. (2004). Research on and research with emerging technologies revisited: The role of disciplined inquiry in the study of technology innovation. In D. H. Jonassen (Ed.), Handbook of research for educational communications and technology (2nd ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Pintrich, P. R. (2003). A motivational science perspective on the role of student motivation in learning and teaching contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 95 , 667–686.

Pintrich, P. R., & De Groot, E. V. (1990). Motivational and self-regulated learning components of classroom academic performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82 (1), 33–40.

Popper, K. (1963). Conjectures and refutations . London: Routledge.

Ravitch, S. M., & Riggan, M. (2012). Reason and rigor: How conceptual frameworks guide research . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Reason, P. (Ed.). (1988). Human inquiry in action: Developments in new paradigm research . London: Sage Publications.

Reason, P. (1994). Three approaches to participative inquiry. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 324–339). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Reeves, T. C. (1995). Questioning the questions of instructional technology research. In M. R. Simonson & M. Anderson (Eds.), Proceedings of the annual conference of the association for educational communications and technology, research and theory division (pp. 459–470). CA: Anaheim.

Reeves, T., Herrington, J., & Oliver, R. (2005). Design research: A socially responsible approach to instructional technology research in higher education. Journal of Computing in Higher Education, 16 (2), 97–116.

Reeves, T., McKenney, S., & Herrington, J. (2011). Publishing and perishing: The critical importance of educational design research. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27 (1), 55–65.

Robson, C. (2011). Real world research: A resource for users of social research methods in applied settings (3rd ed.). Chichester: Wiley.

Rogers, E. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press: New York.

Sangari Active Science (2013). IQWST interactive digital edition. Retrieved May 2, 2014, from http://sangariglobaled.com/iqwst-tablet-edition/ .

Schunk, D. H. (1989). Self-efficacy and achievement behaviors. Educational Psychology Review, 1 , 173–208.

Shields, P. M., & Tajalli, H. (2006). Intermediate theory: The missing link in successful student scholarship. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 12 (3), 313–334.

Spiro, R. J., & Jehng, J. C. (1990). Cognitive flexibility and hypertext: Theory and technology for the nonlinear and multidimensional traversal of complex subject matter. In D. Nix & R. Spiro (Eds.), Cognition, education, and multimedia: Exploring ideas in high technology (pp. 163–205). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Stevenson, A., & Waite, M. (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary (12th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Strauss, A. L. (1987). Qualitative analysis for social scientists . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sweller, J. (1988). Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning. Cognitive Science, 12 (2), 257–285.

Tsai, C.-C., Ho, H.-N., Liang, J.-C., & Lin, H.-M. (2011). Scientific epistemic beliefs, conceptions of learning science and self-efficacy of learning science among high school students. Learning and Instruction, 21 , 757–769.

Tyler, R. W. (1942). General statement on evaluation. Journal of Educational Research, 35 , 492–501.

Winn, W. D. (2002). Current trends in educational technology research: The study of learning environments. Educational Psychology Review, 14 (3), 331–351.

Download references

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the journal editor for their helpful feedback on an early version of this paper.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Florida, PO Box 117048, Norman Hall, Gainesville, FL, 32611-7048, USA

Pavlo D. Antonenko

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Pavlo D. Antonenko .

See Fig. 2 .

A concept map of the original conceptual framework in the Niederhauser et al. ( 2000 ) study

See Fig. 3 .

A concept map of the modified conceptual framework in the Niederhauser et al. ( 2000) ) study. The differences are presented in bold font

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Antonenko, P.D. The instrumental value of conceptual frameworks in educational technology research. Education Tech Research Dev 63 , 53–71 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-014-9363-4

Download citation

Published : 06 December 2014

Issue Date : February 2015

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-014-9363-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Conceptual framework

- Research design

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Family-Centered Theory of Change

A conceptual framework for improving teaching and learning in undergraduate stem courses .

- Juan Salinas The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley

- Parwinder Grewal

- Jose Gutierrez

- Nicolas Pereyra

- Dagoberto Ramirez

- Elizabeth Salinas

- Griselda Salinas

- Virginia Santana

Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs) are often characterized as Hispanic enrolling (rather than serving) that practice deficit-based systems that continue to marginalize Hispanics and other underrepresented students, especially in STEM fields. Extant research on HSIs stresses the importance of investigations into the value of grassroots advocacy groups as external influencers of institutional servingness through deeper engagement with the Hispanic community. Using a novel Family-Centered Theory of Change (FCTC) that addresses diversity, equity, and inclusion, we integrated concepts of intersectionality and servingness into a Family Integrated Education Serving and Transforming Academia (FIESTA) framework. We investigated the potential transformational impact of FIESTA on students, families, faculty, and administrators at The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley (UTRGV), an institution with over 90 % Hispanic population. Preliminary findings shed light on how the FIESTA framework can help reshape an HSI’s identity from “Hispanic enrolling” to a true Hispanic-Serving Institution through Family-Centered Pedagogy. The Family-Centered Pedagogy was defined as the enrichment of the learning experience in which students complement their own instruction by drawing from the experience and ancestral knowledge of their families, supported by the FCTC developed by AVE Frontera, our community partner.

Allsup, C. (1982a). Land of the free, home of the brave. In The American G.I. Forum: Origins and evolution [monograph]. Austin: University of Texas, Center for Mexican American Studies.

Allsup, C. (1982b). Welcome home. In The American G.I. Forum: Origins and evolution [monograph]. Austin: University of Texas, Center for Mexican American Studies.

American Council on Education (1996). Transnational dialogues: Conversations between U.S. college and university CEOs and their counterparts abroad. Washington, DC: Publications TD.

Barnes, M., & Schmitz, P. (2016). Community engagement matters (now more than ever). Stanford Social Innovation Review. Retrieved from https://ssir.org/articles/entry/community_engagement_matters_now_more_than_ever

Blanton, C. (2007). The strange career of bilingual education in Texas, 1836-1981. College Station, TX: A&M University Press.

Carrigan, W. D., & Webb, C. (2013). Forgotten dead: Mob violence against Mexicans in the United States, 1848 – 1928. Oxford, NY: Oxford University Press.

DeNicolo, C. P., González, M., Morales, S., & Romani, L. (2015). Teaching through testimonio: Accessing community cultural wealth in school. Journal of Latinos and Education, 14(4), 228-243.

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

Dunst, C. J. (2002) Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. The Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 139-147.

Excelencia in Education. (2022). Growing what Works Database. Retrieved from https://www.edexcelencia.org/programs-initiatives/growing-what-works-database

Freire, P. (1970). Excerpt from pedagogy of the oppressed. New York, NY: Routledge.

Galdeano, E. C., Flores, A. R., & Moder, J. (2012). The Hispanic association of colleges and universities and Hispanic-serving institutions: Partners in the advancement of Hispanic higher education. Journal of Latinos & Education, 11(3), 157-162.

Gandara, P., Moran, R., & García, E. (2004). Legacy of Brown: Lau and language policy in the United States. Review of Research in Education, 28, 27-46.

Garcia, G. A., Nuñez A. M., & Sansone, V. A. (2019). Toward a multidimensional conceptual framework for understanding “servingness” in Hispanic-serving institutions: A synthesis of the research. Review of Educational Research, 89(5), 745-784.

Guajardo, F., Guajardo, M. (2013). The power of plática. Reflections: A Journal of Public Rhetoric, Civic Writing, and Service Learning. 13(1), 59-164.

Guajardo, M. & Guajardo, F. (2004). The impact of Brown on the brown of south Texas: A micro political perspective on the education of Mexican Americans in a rural south Texas community. American Educational Research Journal, 41(3), 501-526.

Guajardo, M., Guajardo, F., Janson, C., Militello, M. (2016). Reframing Community Partnerships in Education: Uniting the Power of Place and Wisdom of People. New York, NY: Routledge Press.

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U.S. 475; 74 S. Ct. 667; 98 L. Ed. 866 (1954). U.S. LEXIS 2128. Retrieved from www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic

Hurtado, S. (2015). The transformative paradigm: Principles and challenges. In A. Aleman, B.P. Pusser, & E. Bensimon. (Eds.) Critical approaches to the study of higher education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University.

Ladson-Billings, Gloria. (1995). Toward a Theory of Culturally Relevant Pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 32, No. 3, pp. 465-491.

MacDonald, V. M., Botti, J. M., & Clarck, L. H. (2007). From visibility to autonomy: Latinos and higher education in the U.S., 1965-2005. Harvard Educational Review, 77(4), 474-504.

Moll, L. C., Amanti, C., Neff, D., & González, N. (1992). Funds of knowledge for teaching. Theory in Practice, 31(2), 132-140.

Ortegon, R. R. (2013). LULAC v. Richards: The class action lawsuit that prompted the south Texas border initiative and enhanced access to higher education for Mexican Americans living along the south Texas border (Order No. 3604989). [Doctoral dissertation, Northeastern University). ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Ovando, C. (2003). Bilingual education in the United States: Historical and current issues. Bilingual Research Journal, 27(1), 1-24.

Richards v. LULAC, 868 S.W.2d 306 (1993). Tex. LEXIS 120. Retrieved from www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic

Rodriguez v. San Antonio ISD, 337 F. Supp. 280 (1971). U.S. Dist. LEXIS 10250. Retrieved from www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic

Salinas, G., & Lopez, J. (2021). A vehicle of engagement for quality education and student success: La frontera program for immigrant families and students. The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley. Retrieved from https://www.utrgv.edu/sustainability/sustainability-research-fellowships/meet-the-fellows/index.htm

Salinas, J., Jr. (2018). Higher education social responsibility: An empirical analysis and assessment of a Hispanic-serving institution’s commitment to community-engaged scholarship, student integration and sense of belonging (Order No. 10976893). [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Texas Rio Grande Valley]. ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

Santiago, D. A. (2006). Inventing Hispanic-serving institutions (HSIs): The basics. Excelencia in Education. Retrieved from https://www.edexcelencia.org/research/pubs.asp

Santiago, D. A. (2012). Public policy and Hispanic-serving institutions: From invention to accountability. Journal of Latinos and Education, 11(3), 163-167. doi: 10.1080/15348431.2012.686367

Satterfield, J., & Rincones, R. D. (2008). An evolving curriculum: The technical core of Hispanic-serving institutions in the state of Texas. College Quarterly, 11(4), 1-19.

Serna v. Portales, 499 F.2d 1147 (1974). U.S. App. LEXIS 7619. Retrieved from www.lexisnexis.com/hottopics/lnacademic

Valencia, R. (2000). Inequalities and the schooling of minority students in Texas: Historical and contemporary condition. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 22(4), 445-459.

Yarsinske, A. W. (2004). All for one and one for all: A celebration of 75 years of the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). Donning Company Publishers.

Yosso, T.J. (2005). Whose Culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race, Ethnicity, and Education, 8 (1), 69-91.

Copyright (c) 2024 Juan Salinas, Parwinder Grewal, Jose Gutierrez, Nicolas Pereyra, Dagoberto Ramirez, Elizabeth Salinas, Griselda Salinas, Virginia Santana, Can Saygin

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License .

Developed By

Information.

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

Metropolitan Universities journal is the Coalition of Urban and Metropolitan Universities ’ (CUMU) quarterly online journal. Founded in 1990, the journal disseminates scholarship and research relevant to urban and metropolitan universities. Articles amplify the mission of CUMU by reinforcing the value of place-based institutions and illuminating our collective work of supporting the changing needs of our students, institutions, and cities.

If you would like to receive updates about the journal or CUMU, sign up to receive email communications .

Restricted Access

Reason: Restricted by author. A copy can be supplied under Section 51(2) of the Australian Copyright Act 1968 by submitting a document delivery request through your library

Engineering education for sustainability: An international cross-case analysis

Campus location, principal supervisor, additional supervisor 1, additional supervisor 2, year of award, department, school or centre, degree type, usage metrics.

- Environmental education curriculum and pedagogy

- Engineering education

- Curriculum and pedagogy theory and development

- Science, technology and engineering curriculum and pedagogy

- Higher education

- Introduction

- Conclusions

- Article Information

Description of participant enrollment, allocation, and analysis.

a The tasks were not mutually exclusive—we wanted the 30 physicians to do all 3 tasks.

Trial Protocol

eReferences.

eFigure. Screenshots of Game Loop

eTable 1. Characteristics of Responders and Nonresponders to the Virtual Simulation

eTable 2. Structured Assessment of Acceptability of Intervention

Data Sharing Statement

See More About

Sign up for emails based on your interests, select your interests.

Customize your JAMA Network experience by selecting one or more topics from the list below.

- Academic Medicine

- Acid Base, Electrolytes, Fluids

- Allergy and Clinical Immunology

- American Indian or Alaska Natives

- Anesthesiology

- Anticoagulation

- Art and Images in Psychiatry

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assisted Reproduction

- Bleeding and Transfusion

- Caring for the Critically Ill Patient

- Challenges in Clinical Electrocardiography

- Climate and Health

- Climate Change

- Clinical Challenge

- Clinical Decision Support

- Clinical Implications of Basic Neuroscience

- Clinical Pharmacy and Pharmacology

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Consensus Statements

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Critical Care Medicine

- Cultural Competency

- Dental Medicine

- Dermatology

- Diabetes and Endocrinology

- Diagnostic Test Interpretation

- Drug Development

- Electronic Health Records

- Emergency Medicine

- End of Life, Hospice, Palliative Care

- Environmental Health

- Equity, Diversity, and Inclusion

- Facial Plastic Surgery

- Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Genomics and Precision Health

- Global Health

- Guide to Statistics and Methods

- Hair Disorders

- Health Care Delivery Models

- Health Care Economics, Insurance, Payment

- Health Care Quality

- Health Care Reform

- Health Care Safety

- Health Care Workforce

- Health Disparities

- Health Inequities

- Health Policy

- Health Systems Science

- History of Medicine

- Hypertension

- Images in Neurology

- Implementation Science

- Infectious Diseases

- Innovations in Health Care Delivery

- JAMA Infographic

- Law and Medicine

- Leading Change

- Less is More

- LGBTQIA Medicine

- Lifestyle Behaviors

- Medical Coding

- Medical Devices and Equipment

- Medical Education

- Medical Education and Training

- Medical Journals and Publishing

- Mobile Health and Telemedicine

- Narrative Medicine

- Neuroscience and Psychiatry

- Notable Notes

- Nutrition, Obesity, Exercise

- Obstetrics and Gynecology

- Occupational Health

- Ophthalmology

- Orthopedics

- Otolaryngology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Care

- Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

- Patient Care

- Patient Information

- Performance Improvement

- Performance Measures

- Perioperative Care and Consultation

- Pharmacoeconomics

- Pharmacoepidemiology

- Pharmacogenetics

- Pharmacy and Clinical Pharmacology

- Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation

- Physical Therapy

- Physician Leadership

- Population Health

- Primary Care

- Professional Well-being

- Professionalism

- Psychiatry and Behavioral Health

- Public Health

- Pulmonary Medicine

- Regulatory Agencies

- Reproductive Health

- Research, Methods, Statistics

- Resuscitation

- Rheumatology

- Risk Management

- Scientific Discovery and the Future of Medicine

- Shared Decision Making and Communication

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports Medicine

- Stem Cell Transplantation

- Substance Use and Addiction Medicine

- Surgical Innovation

- Surgical Pearls

- Teachable Moment

- Technology and Finance

- The Art of JAMA

- The Arts and Medicine

- The Rational Clinical Examination

- Tobacco and e-Cigarettes

- Translational Medicine

- Trauma and Injury

- Treatment Adherence

- Ultrasonography

- Users' Guide to the Medical Literature

- Vaccination

- Venous Thromboembolism

- Veterans Health

- Women's Health

- Workflow and Process

- Wound Care, Infection, Healing

Get the latest research based on your areas of interest.

Others also liked.

- Download PDF

- X Facebook More LinkedIn

Mohan D , Elmer J , Arnold RM, et al. Testing a Novel Deliberate Practice Intervention to Improve Diagnostic Reasoning in Trauma Triage : A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial . JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(5):e2313569. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.13569

Manage citations:

© 2024

- Permissions

Testing a Novel Deliberate Practice Intervention to Improve Diagnostic Reasoning in Trauma Triage : A Pilot Randomized Clinical Trial

- 1 Department of Surgery, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 2 Department of Critical Care Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 3 Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 4 Department of Neurology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 5 Division of Palliative Care, Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

- 6 Department of Engineering and Environmental Policy, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Question Can deliberate practice (goal-oriented training with a coach who provides immediate, personalized performance feedback) improve diagnostic reasoning in trauma triage?

Findings In this pilot randomized clinical trial of a novel deliberate practice intervention, 93% of participants received 3 planned coaching sessions, and most participants (93%) described the sessions as entertaining and valuable. During a simulation, the triage decisions of physicians in the intervention group were more likely to adhere to clinical practice guidelines than the triage decisions of physicians in the control group.

Meaning The deliberate practice intervention was feasible, acceptable, and effective in the laboratory, setting the stage for a future phase 3 clinical trial.

Importance Diagnostic errors made during triage at nontrauma centers contribute to preventable morbidity and mortality after injury.

Objective To test the feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effect of a novel deliberate practice intervention to improve diagnostic reasoning in trauma triage.

Design, Setting, and Participants This pilot randomized clinical trial was conducted online in a national convenience sample of 72 emergency physicians between January 1 and March 31, 2022, without follow-up.

Interventions Participants were randomly assigned to receive either usual care (ie, passive control) or a deliberate practice intervention, consisting of 3 weekly, 30-minute, video-conferenced sessions during which physicians played a customized, theory-based video game while being observed by content experts (coaches) who provided immediate, personalized feedback on diagnostic reasoning.

Main Outcomes and Measures Using the Proctor framework of outcomes for implementation research, the feasibility, fidelity, acceptability, adoption, and appropriateness of the intervention was assessed by reviewing videos of the coaching sessions and conducting debriefing interviews with participants. A validated online simulation was used to assess the intervention’s effect on behavior, and triage among control and intervention physicians was compared using mixed-effects logistic regression. Implementation outcomes were analyzed using an intention-to-treat approach, but participants who did not use the simulation were excluded from the efficacy analysis.

Results The study enrolled 72 physicians (mean [SD] age, 43.3 [9.4] years; 44 men [61%]) but limited registration of physicians in the intervention group to 30 because of the availability of the coaches. Physicians worked in 20 states; 62 (86%) were board certified in emergency medicine. The intervention was delivered with high fidelity, with 28 of 30 physicians (93%) completing 3 coaching sessions and with coaches delivering 95% of session components (642 of 674). A total of 21 of 36 physicians (58%) in the control group participated in outcome assessment; 28 of 30 physicians (93%) in the intervention group participated in semistructured interviews, and 26 of 30 physicians (87%) in the intervention group participated in outcome assessment. Most physicians in the intervention group (93% [26 of 28]) described the sessions as entertaining and valuable; most (88% [22 of 25]) affirmed the intention to adopt the principles discussed. Suggestions for refinement included providing more time with the coach and addressing contextual barriers to triage. During the simulation, the triage decisions of physicians in the intervention group were more likely to adhere to clinical practice guidelines than those in the control group (odds ratio; 13.8, 95% CI, 2.8-69.6; P = .001).

Conclusions and Relevance In this pilot randomized clinical trial, coaching was feasible and acceptable and had a large effect on simulated trauma triage decisions, setting the stage for a phase 3 trial.

Trial Registration ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT05168579

Half of all injured patients present initially to a nontrauma center, where a clinician must evaluate and stabilize the patient’s injuries and determine whether they warrant transfer to a trauma center. 1 , 2 Timely and guideline-concordant referral reduces mortality by 10% to 25%, increases rates of functional independence, and shortens the duration of pain and disability. 3 - 9 Despite 40 years of efforts by stakeholders to standardize triage practices, undertriage remains common, particularly among patients older than 65 years. 10 - 13 Diagnostic errors—defined as the failure to establish an accurate and timely explanation of the patient’s health problem—are an important cause of undertriage. 14 , 15

Deliberate practice, defined as goal-oriented training in the presence of a content expert who can provide personalized, immediate feedback to improve performance, has successfully improved outcomes across multiple domains, including sports, combat, and surgery. 16 - 18 However, the use of deliberate practice to improve diagnostic reasoning is uncommon and, to our knowledge, has never been tried in trauma triage. 19

The objective of this pilot randomized clinical trial was to test the feasibility (practicability), fidelity (delivery of tasks), acceptability (palatability), adoption (intention to try behaviors), appropriateness (fitting the user’s goals and needs), and effect (compliance with clinical guidelines) of a novel deliberate practice intervention in trauma triage.

We conducted a pilot randomized clinical trial of a deliberate practice intervention to improve diagnostic reasoning in trauma triage between January 1 and March 31, 2022, without follow-up. We enrolled and randomized a national respondent-driven sample of physicians to the intervention group or to a passive control group. We structured the process evaluation of the intervention using the Proctor framework of outcomes for implementation research and followed the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Extension ( CONSORT Extension ) reporting guideline (ie, extension for pilot and feasibility trials) in reporting our results. 20 , 21 We previously published the trial protocol with a priori hypotheses about criteria for defining success. 22 The University of Pittsburgh Human Research Protection Office approved the study. Trial participants provided digital written informed consent at the time of enrollment (trial protocol in Supplement 1 ).

To recruit participants for the study, we contacted physicians who had previously participated in our research and asked them to refer us to 2 colleagues. We sought board-certified emergency physicians who treated adult patients in the emergency department of either a nontrauma center or a Level III or IV trauma center in the US and who therefore would have responsibility for performing trauma triage in their clinical practice. Respondents received a screening questionnaire with details about the trial, a consent form, and items querying their demographic characteristics. Racial and ethnic categories were specified by the study team based on National Institutes of Health criteria. 23 Physicians who provided consent were randomized in a 1:1 ratio, stratified by prior participation in our research, using a schema built in Stata, version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC), with block sizes of 4 ( Figure 1 ). Although we could not blind study personnel and participants, we masked physicians’ exposure during analysis.

Three members of the study team with expertise in trauma surgery (D.M. and R.M.F.) and emergency medicine (J.E.) acted as the coaches. We standardized the fidelity of intervention delivery in 3 ways. First, prior to the trial, we conducted three 1-hour training sessions, supervised by experts in deliberate practice (R.M.A., B.F., and D.B.W.). Second, we created a coaching manual as a reference that summarized the learning objectives, core tasks of the coaching sessions, and the pedagogical strategies that coaches should use (a full draft of the coaching manual is in the eAppendix in Supplement 2 ). Finally, coaches met weekly with the full study team during the trial to debrief and to discuss strategies for managing issues that had arisen. Based on these sessions, we made several modifications to the intervention, including condensing the content to increase the time spent on each decision principle and identifying additional pedagogical strategies that coaches could use to engage participants in the sessions (eg, retrieval practice during sessions 2 and 3).

The intervention consisted of 3 weekly, 30-minute, video-conferenced coaching sessions, in which the participant played a trauma triage video game, the coach observed his or her performance, and they discussed best practice decision principles in trauma triage. We describe the conceptual framework of the intervention in Figure 2 .

We used a single-player, theory-based puzzle video game, previously developed by our group to improve diagnostic reasoning in trauma triage ( Shift: The Next Generation ). 24 To allow its use as a training task, we adapted the user interface and game mechanics in collaboration with Schell Games, creating Shift With Friends . The game included 10 levels, each covering a separate decision principle and involving a 5-step game loop (eFigure in Supplement 2 ): players triaged 10 injured patients over 90 seconds, compared 2 cases to identify similarities or differences so that they could derive the rule for the level, received standardized feedback on their performance, reviewed the decision principle, and finally received a synthesis of the evidence supporting the decision principle.

Both the participant and the coach logged into Zoom, and the participant shared his or her screen so that the coach could observe gameplay. The coach would select the levels covered during the session, personalizing the selection to the needs and skills of the participant. The coach would also encourage the participant to “think aloud” as he or she played, using observations made during the process to provide feedback tailored to improve the participant’s diagnostic reasoning. Each session covered 1 to 3 decision principles and included 6 to 8 tasks (eg, introductions or debriefing).

We did not ask trial participants randomly assigned to the control group to engage in any additional continuing medical education, with the intention of replicating usual care.

After randomization, participating physicians received written instructions on how to complete the trial tasks. We had the capacity to provide coaching for 30 physicians. We therefore asked those in the intervention group to select 1 of the 2 blocks (January or February) in which we offered coaching and to sign up for three 30-minute sessions within the block. Based on availability, we paired participants with a coach on a first-come, first-served basis. After the sessions, we asked participants to complete a survey, a semistructured debriefing interview, and an online simulation. We asked participants in the passive control group to complete the same simulation within 3 weeks of the start of the trial. The trial tasks took approximately 3 hours for those in the intervention group and 1 hour for those in the control group. Participants received 3 personalized reminder emails at weekly intervals or until they completed the trial tasks. We offered a financial incentive to increase response rates, setting its size with a wage-based model of reimbursement. 25 , 26 Physicians in the intervention group received an iPad with the game and Zoom app preloaded, which they used for the coaching sessions and which they kept as their honorarium (approximate value, $300). Those in the control group received a $100 gift card after they completed the simulation.

Using the Proctor framework of outcomes for implementation research, we assessed both implementation and service outcomes. 20 We defined the implementation outcomes as feasibility, fidelity, acceptability, adoption, and appropriateness. Using the National Institutes of Health stage model of intervention development, which recommends assessment of efficacy in the laboratory before moving to real-world testing, 27 we defined the service outcome (efficacy) as compliance with clinical practice guidelines, measured using a simulation.

Each respondent described his or her personal characteristics on the screening questionnaire at the time of enrollment. We maintained a database with a list of scheduled coaching sessions, which was updated daily with the status of the sessions.

We recorded all the coaching sessions and automatically uploaded them to a secure server hosted by the University of Pittsburgh. Two members of the study team (K.R. and J.L.B.) developed a codebook to assess the delivery of session tasks, refined it until they achieved acceptable interrater reliability (Cohen κ = 0.84), and independently applied it to the recordings. Coding discrepancies were resolved through consensus (D.M., K.R., and J.L.B.). We used NVivo qualitative analysis software (QSR International) for data management.

Participants in the intervention group provided structured assessments of the acceptability of the intervention using the User Engagement Scale–Short Form to evaluate the video game (a validated 12-item instrument with a 5-point Likert scale) and the Wisconsin Surgical Coaching Rubric to evaluate the quality of the coaching (a 4-item instrument with a 5-point scale). 28 , 29 They also participated in semistructured debriefing interviews after the final coaching session, during which they discussed their perception of the acceptability, adoption, and appropriateness of the intervention. Two members of the study team (K.R. and J.L.B.) coded the interviews using the same process as for the coaching sessions (Cohen κ = 0.84).

We used a validated 2-dimensional simulation to assess compliance with guidelines after exposure to the intervention. 30 The simulation required participants to respond to 10 cases over 42 minutes: 4 severely injured patients, 2 minimally injured patients, and 4 critically ill nontrauma patients (ie, distractor patients). New patients arrived at prespecified but unpredictable intervals, so that users managed multiple patients concurrently. Without clinical intervention by the player, severely injured patients and critically ill distractor patients decompensated and died over the course of the simulation. Each case included a 2-dimensional rendering of the patient, a chief symptom, vital signs that updated every 30 seconds, a history, and a written description of the physical examination. Users could request information by selecting from a prespecified list of 250 medications, studies, and procedures. They could place orders and request consultations. Each case ended when either the player made a disposition decision (admit, discharge, or transfer) or the patient died. We asked all trial participants to complete the simulation online; responses were uploaded and stored on a secure server hosted by the University of Pittsburgh.

We summarized physician characteristics using mean (SD) values for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. We analyzed implementation outcomes using an intention-to-treat approach but excluded from the efficacy analysis participants who did not use the simulation. We had 2 criteria for the success of the trial: efficacy and feasibility. Our primary hypothesis was that physicians exposed to the intervention would undertriage 25% fewer patients or more on the simulation than physicians in the control group. All P values were from 2-sided tests and results were deemed statistically significant at P < .05. Our secondary hypothesis was that we could deliver 3 coaching sessions to 90% or more of participants. All analyses were conducted in Stata, version 16.0 (StataCorp LLC).

We quantified the percentage of coach-participant dyads that completed three 30-minute sessions (to measure feasibility) and summarized the percentage of session tasks delivered to participants (to measure fidelity). We summarized participant responses to the User Engagement Scale–Short Form and to the Wisconsin Surgical Coaching Rubric (to measure acceptability). We also summarized themes that arose during the semistructured interviews (to further assess acceptability and to assess appropriateness and adoption).

We summarized the time spent and the decisions made for each severely injured trauma case (n = 4) on the simulation (eg, diagnostic testing or administration of blood products) using median values and IQRs, and we scored disposition decisions as consistent with the American College of Surgeons guidelines or not. To compare differences between the intervention and control groups, we fit a mixed-effects logistic regression model, clustered at the participant level, with the transfer decision as the dependent variable and physicians’ exposure as the primary independent variable. Given the statistical power, we did not adjust for any potential confounders (eg, practice environment). In a post hoc sensitivity analysis, we excluded physicians who had previously participated in our research.

We designed the experiment to detect a 25% (large effect size) reduction in undertriage between physicians in the intervention and control groups, with an α of .05 and a power of 80%, using the Cohen method of estimating power for behavioral trials. Based on these estimates, and anticipating a 67% retention rate in the control group, we planned to recruit 30 physicians for each group. 31