- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Contentious Politics and Political Violence

- Governance/Political Change

- Groups and Identities

- History and Politics

- International Political Economy

- Policy, Administration, and Bureaucracy

- Political Anthropology

- Political Behavior

- Political Communication

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Philosophy

- Political Psychology

- Political Sociology

- Political Values, Beliefs, and Ideologies

- Politics, Law, Judiciary

- Post Modern/Critical Politics

- Public Opinion

- Qualitative Political Methodology

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- World Politics

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Attitudes toward women and the influence of gender on political decision making.

- Mary-Kate Lizotte Mary-Kate Lizotte Department of Social Sciences, Augusta University

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190228637.013.771

- Published online: 28 August 2018

There is a great deal of research, spanning social psychology, sociology, and political science, on politically relevant attitudes toward women and the influence of gender on individual’s political decision making. First, there are several measures of attitudes toward women, including measures of sexism and gender role attitudes, such as the Attitudes Toward Women Scale, the Old-Fashioned Sexism Scale, the Modern Sexism Scale, and the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory. There are advantages and disadvantages of these existing measures. Moreover, there are important correlates and consequences of these attitudes. Correlates include education level and the labor force participation of one’s mother or spouse. The consequences of sexist and non-egalitarian gender role attitudes include negative evaluations of female candidates for political office and lower levels of gender equality at the state level. Understanding the sources and effects of attitudes toward women is relevant to public policy and electoral scholars.

Second, gender appears to have a strong effect on shaping men’s and women’s attitudes and political decisions. Gender differences in public opinion consistently arise across several issue areas, and there are consistent gender differences in vote choice and party identification. Various issues produce gender gaps, including the domestic and international use of force, compassion issues such as social welfare spending, equal rights, and government spending more broadly. Women are consistently more liberal on all of these policies. On average, women are more likely than men to vote for a Democratic Party candidate and identify as a Democrat. There is also a great deal of research investigating various origins of these gender differences. Comprehending when and why gender differences in political decision making emerge is important to policymakers, politicians, the political parties, and scholars.

- public opinion

- attitudes toward women

- political behavior

- gender role attitudes

- feminist identification

- party identification

- political ideology

- political decision making

Introduction

Historically, gendered attitudes toward women effectively excluded women from political participation, silencing women’s policy preferences and public opinion, and preventing them from contributing to political institutions. American women supporting the abolition of slavery attended the World Anti-Slavery Convention in London in 1840 . These women, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, were not allowed to participate in the conference proceedings. Realizing that their desire to effect change was hindered by their inability to participate in politics, a desire for change—via women’s rights and eventually suffrage—soon began to develop (Ford, 2017 ). Attitudes toward women were making it impossible for women’s policy preferences to be heard by other citizens or heeded by government officials. This historical example illustrates the importance of understanding attitudes toward women and the influence of gender on public opinion and other political decisions. Stanton and Mott epitomize the importance of studying gender and political decision making. This essay discusses both attitudes toward women and gender differences in political decision making. The first section provides an overview of politically relevant attitudes toward women. A discussion of the role of gender in shaping individuals’ political attitudes and decisions follows. This article focuses primarily on political decision makers as its unit of analysis. For more on how candidates are gender stereotyped and its implications, see Bauer (“Gender Stereotyping in Political Decision Making,” this work).

Attitudes Toward Women and Gender Equality

An abundance of research exists studying attitudes toward women, much of which has a particular focus on sexist attitudes and gender role attitudes. This research is predominantly from social psychology and sociology but is relevant to politics and political science because of the consequences such attitudes have for policy preferences and support for women in politics. This section provides a critical overview of several measures of attitudes toward women and their consequences. Gender differences are an important component of this research and are noted throughout this section on attitudes toward women. This section does not provide an exhaustive list of measures of attitudes toward women and does not discuss the reliability or validity of the measures (see McHugh & Frieze, 1997 , for a discussion).

Sexism, Gender Role Attitudes, and Feminism

One of the older measures is the Attitudes Toward Women Scale, which was developed in the early 1970s to measure attitudes about women’s rights, gender roles, proper behavior of women, and women’s responsibilities in the public and private spheres (Spence, Helmreich, & Stapp, 1973 ). Women are consistently more egalitarian in their scores on the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (Spence & Hahn, 1997 ), meaning that women are more likely to endorse equal opportunity in the workplace, to advocate shared household and parenting duties between men and women, and to oppose a double standard for sex before marriage. Overtime, men’s and women’s attitudes have on average become more egalitarian (Spence & Hahn, 1997 ). Although its widespread usage over the decades makes it useful for comparisons over time, the scale may now be outdated and no longer properly discriminates between individuals with differing attitudes, particularly at the liberal end of the spectrum. This may be due to changes in attitudes and possibly also because of social desirability (Fassinger, 1994 ; Spence & Hahn, 1997 ). For example, this scale measures support for equal opportunity in the workplace, the acceptability for women to engage in sex before marriage, and the sharing of household and parenting responsibilities, all of which have become much more mainstream attitudes and behaviors compared to in the 1970s when the scale originated.

Two more recent measures of sexism exist, which were developed to better capture contemporary sexist attitudes. First, the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory measures hostile sexism and benevolent sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1996 ). Hostile sexism includes antagonism toward women seeking special favors in the workplace, the belief that women are overly sensitive to sexist remarks, and the belief that women use of their sexuality to control men. Benevolent sexism consists of the desire to protect women, placing women on a pedestal, and believing that women are morally superior. Men are more likely to endorse hostile sexism, and women often endorse benevolent sexism while opposing hostile sexism (Glick & Fiske, 2001 ).

The second category of contemporary measures of sexism, the Modern Sexism Scale and the Old-Fashioned Sexism Scale, measure nuances within contemporary sexist attitudes (Swim, Aikin, Hall, & Hunter, 1995 ). The Modern Sexism Scale is a measure of sexism including the denial of gender discrimination, a lack of understanding for the concerns of women’s groups, and denial of sexism on television (Swim et al., 1995 ). The Old-Fashioned Sexism Scale includes beliefs that women are not as smart as men, that mothers should take on the burden of child care to a greater extent than men, and that having a woman as a boss would be uncomfortable (Swim et al., 1995 ). Men are more likely than women to endorse the measures of Modern Sexism and Old-Fashioned Sexism (Barreto & Ellemers, 2005 ; Swim et al., 1995 ).

It may seem as though there has been an unnecessary proliferation of scales measuring attitudes toward women. While historical and contemporary sexism scales do correlate with one another, they are measuring somewhat distinct underlying beliefs. For example, the Attitudes Toward Women Scale and the Modern Sexism Scale are distinct but correlated measures (Swim & Cohen, 1997 ). The Old-Fashioned Sexism Scale, however, appears to measure the same underlying beliefs as the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (Swim & Cohen, 1997 ). The Hostile Dimension of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory moderately correlates with the Attitudes Toward Women Scale, the Modern Sexism Scale, and the Old-Fashioned Sexism Scale (Glick & Fiske, 1997 ). There is a low correlation between the benevolent dimension and these other measures of sexism (Glick & Fiske, 1997 ). As time goes on, attitudes of interest to researchers change, as does how to best capture culturally prevalent attitudes.

Feminist identity, endorsement of feminist beliefs, or support for the feminist movement are other ways to measure politically relevant attitudes toward women. Gender differences are significant, particularly for male respondents who are less likely to identify as feminists, shaping their attitudes toward women in general. Analysis of 1996 General Social Survey (GSS) data reveals that women are more likely than men to identify as a feminist (McCabe, 2005 ; Schnittker, Freese, & Powell, 2003 ). In the 1996 ANES, men were 8 percentage points less likely to support equal rights for women and 11 percentage points less likely to report favorable views toward the women’s movement (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). In the 2004 ANES, men were 4 percentage points less likely to support equal rights (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). The gender gap in feminist identification appears to range between 9 to 40 percentage points depending on available response options (Huddy, Neely, & Lafay, 2000 ). Attitudes around feminism even shape men’s attitudes toward women who self-identify as feminists: according to feeling thermometer ratings in the 1988 American National Election Study (ANES), men rated feminists less favorably than women (Cook & Wilcox, 1991 ). It is important to note that researchers do not always find gender differences in feminist identification or feminist beliefs (Clark & Clark, 2009 ; Rhodebeck, 1996 ).

Gender ideology, the belief in separate spheres for men and women, and gender role attitudes may be rooted in interest-based or exposure-based explanations (Davis & Greenstein, 2009 ). The interest-based explanation is that women benefit from more egalitarian attitudes and are therefore more likely than men to hold egalitarian gender attitudes, and the exposure-based explanation includes that socialization, like being raised by an educated and/or working mother, leads to more egalitarian gender views (Davis & Greenstein, 2009 ). There is support for the interest-based explanation as women are more likely to identify as feminist, endorse feminist beliefs, and feel positively toward the feminist movement (Clark & Clark, 2009 ; Huddy et al., 2000 ; McCabe, 2005 ; Schnittker et al., 2003 ). Additionally, women have less sexist/more egalitarian views than men on the Attitudes Toward Women Scale, the Ambivalence Sexism Inventory, the Modern Sexism Scale, and the Old-Fashioned Sexism Scale (Barreto & Ellemers, 2005 ; Glick & Fiske, 2001 ; Spence & Hahn, 1997 ; Swim et al., 1995 ).

There is also evidence to support the interest-based explanation using other measures of gender role attitudes. Generally, women have more egalitarian gender attitudes than men (Brewster & Padavic, 2000 ). In one study of GSS data from 1974 to 2006 , black females are the most liberal on gender role attitudes, measured as women’s suitability for politics and women’s traditional family responsibilities, than white females, white males, and black males; there is also a main effect of gender, with females more liberal than males (Carter, Corra, & Carter, 2009 ). Among women, working outside the home and higher education levels lead to greater support for equal gender roles, while frequent church attendance predicts more conservative views (Bolzendahl & Myers, 2004 ). Using a two-wave study of married individuals across both waves, support exists for the interest-based explanation, including female employment and the presence of a small child positively related to women’s levels of egalitarianism (Kroska & Elman, 2009 ).

Evidence exists supporting the exposure-based explanation as well. First, exposure via parents or a spouse appears to lead to more egalitarian gender role attitudes. Among men, having a spouse in the labor force and higher education of one’s mother are associated with more liberal views toward gender roles, while church attendance is associated with more conservative views (Bolzendahl & Myers, 2004 ). A two-wave study of married individuals finds support for the exposure-based explanation with a positive relationship between spouse and individual levels of gender role egalitarianism (Kroska & Elman, 2009 ). For men, having an employed mother is positively associated with feminist identity and holding feminist opinions (Rhodebeck, 1996 ).

Second, exposure via higher levels of education or liberal/Democratic identification leads to attitudes that are more egalitarian on gender roles. For men and women higher education levels predict more egalitarian gender attitudes (Brewster & Padavic, 2000 ). Among men, higher levels of education are positively associated with feminist identity and holding feminist opinions (Rhodebeck, 1996 ). In the 1996 GSS, men and women with higher levels of education, liberal ideology, and Democratic partisanship are also more likely to identify as feminist (McCabe, 2005 ). It is possible that egalitarian gender role attitudes lead to liberal/Democratic identification and not vice versa. Additionally, it may be the case that African Americans are more likely exposed to egalitarian gender roles because of a longer history of black women working outside the home. There are racial and gender differences, with whites and men being less liberal (Carter et al., 2009 ). 1

Consequences

Understanding how sexism, feminist identity, and gender role attitudes correlate with or predict other attitudes and outcomes is important in shaping attitudes toward women in the public sphere, particularly in politics. This section also discusses other evidence of politically relevant attitudes toward women, such as women’s suitability for politics.

With respect to policy preferences, less research has focused on these attitudes as predictors of issue positions. Benevolent sexism predicts support for and hostile sexism predicts opposition to affirmative action policies to promote the hiring of women among New Zealanders (Fraser, Osborne, & Sibley, 2015 ). A recent study employing 2006 Cooperative Congressional Election Study data finds that “modern sexism” predicts anti-abortion attitudes, support for the Iraq War, and less support for employment discrimination legislation to protect women; support for traditional women’s roles also predicts opposition to abortion and support for the war in Iraq (Burns, Jardina, Kinder, & Reynolds, 2016 ).

More research has investigated these attitudes as predictors of candidate evaluations (see “Gender Stereotyping in Political Decision Making,” this work). In an experiment, individuals with more egalitarian scores on the Attitudes Toward Women Scale rated female candidates as more effective at solving problems of the disabled, the aged, and the educational system as well as at guaranteeing rights for racial minorities (Rosenwasser, Rogers, Fling, Silvers-Pickens, & Butemeyer, 1987 ). Individuals with less egalitarian scores on the Attitudes Toward Women Scale rated male candidates as more effective at dealing with military issues (Rosenwasser et al., 1987 ). Men possessing hostile sexist attitudes evaluate women in nontraditional roles such as career women more negatively than women in traditional roles (Glick, Diebold, Bailey-Werner, & Zhu, 1997 ). “Hostile sexism” influences competence ratings of female political candidates in an experiment (Carey & Lizotte, 2017 ). Modern sexism and hostile sexism are associated with a greater likelihood of favorability and voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election (Blair, 2017 ; Bock, Byrd-Craven, & Burkley, 2017 ; Cassese & Holman, 2016 ; Valentino, Wayne, & Oceno, 2018 ) and voting for Romney among men in the 2012 presidential election (Simas & Bumgardner, 2017 ). In slight contrast, “benevolent sexism” predicted greater support for Clinton after exposure to a Trump attack on Clinton for “playing the woman’s card” (Cassese & Holman, 2016 ).

In the 1996 GSS, feminist identifiers, which are more likely to be women, are more likely to support abortion legality, affirmative action for women, and gender equality in employment as well as in the home (Schnittker et al., 2003 ). For men, feminist identification is associated with positive views toward women in politics, mothers working outside the home, and career-focused women but is not associated with those attitudes for women according to analysis of the 1996 GSS (McCabe, 2005 ). Perceptions of candidate positions on the issue of equal gender roles leads to greater support for Democratic presidential candidates in the 1988 through 2012 presidential elections (Hansen, 2016 ). Feminism appears to have a substantial influence on partisanship particularly among women, with feminist women being very likely to identify as Democrats and anti-feminist women being increasingly likely to identify as Republican (Beinart, 2017 ; Huddy & Willmann, 2017 ).

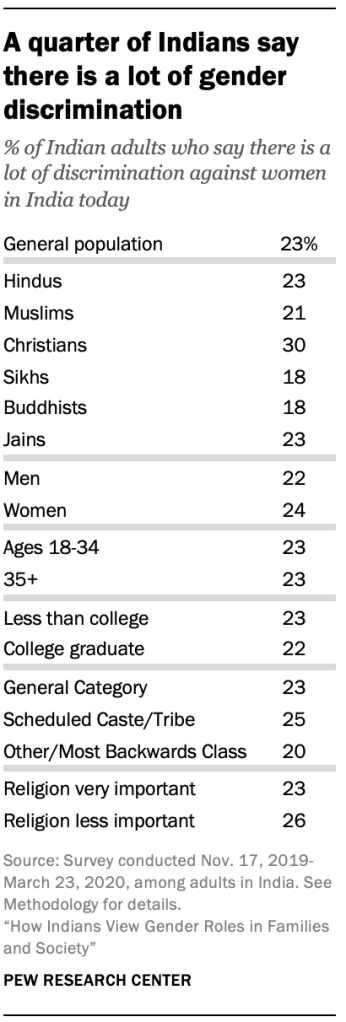

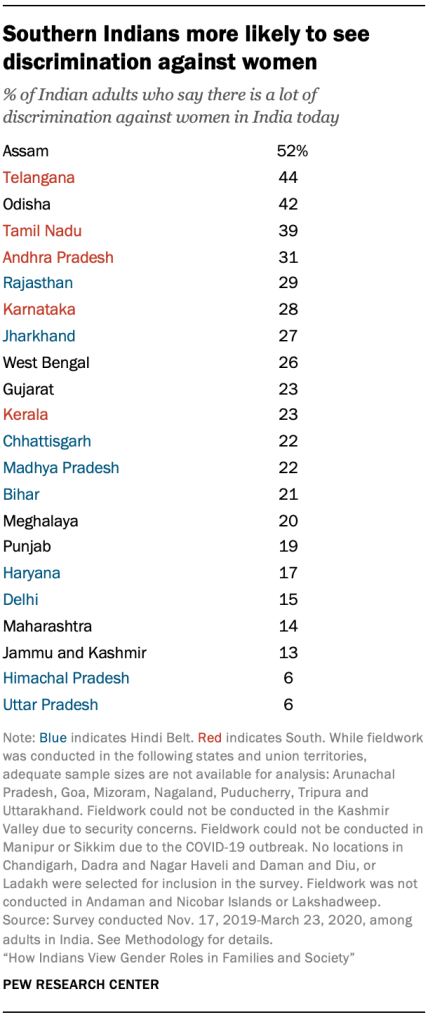

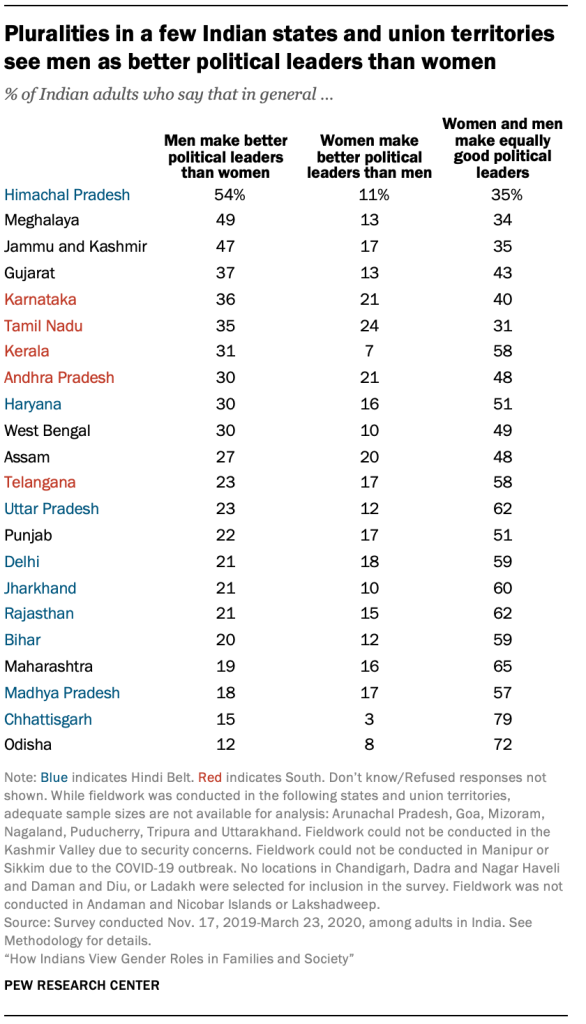

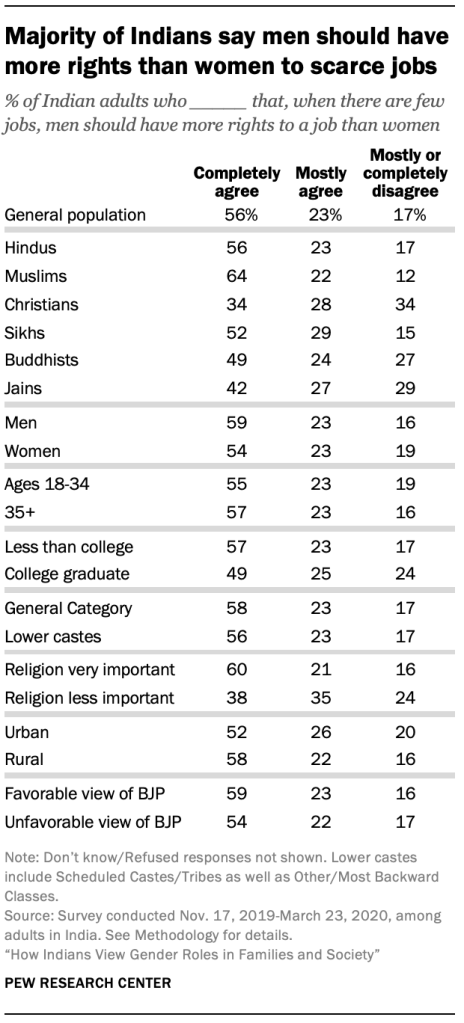

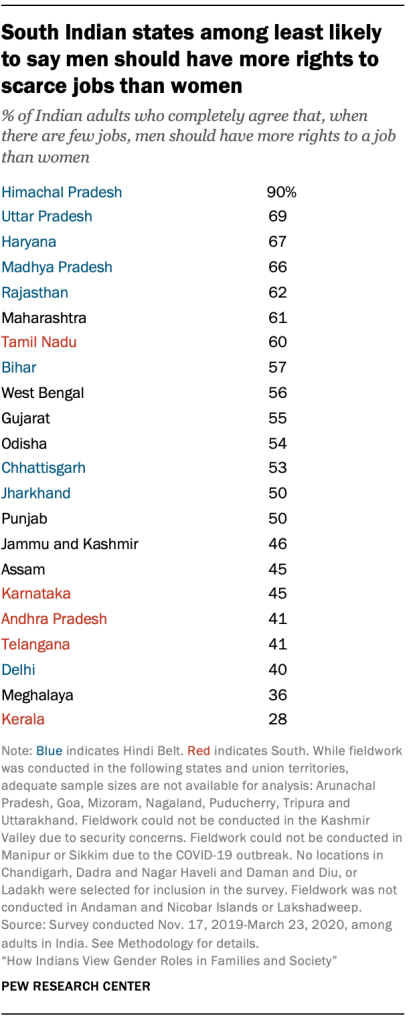

There is comparative cross-country data showing that individual attitudes toward women correlate with or predict gender inequality at the national level. Sexism at the individual level, measured as a belief that men make better political leaders and business executives than women, is associated with gender inequality at the nation level across 57 different countries including the United States (Brandt, 2011 ). Similar results exist for hostile and benevolent sexism; men’s average level of sexism, both hostile and benevolent, is correlated with gender inequality at the state level in 19 countries (Glick & Fiske, 2001 ). Egalitarian gender role attitudes, compared to traditional gender role attitudes, predicts higher income levels among women in data including individuals from 28 different countries (Stickney & Konrad, 2007 ).

Finally, there is research in political science that looks at support for women in politics but does not include measures of sexism, feminist identity, or gender role attitudes. This research area is vast, and the following discussion is not exhaustive. Some of this research does not find gender differences. According to analysis of GSS data from 1972 , 1974 , and 1978 , there were no consistent gender differences on women’s suitability for politics, while younger people, more educated individuals, and less religious respondents were more likely to view women as suitable for politics (Welch & Sigelman, 1982 ). In 1974 and 1978 GSS data, white women did not significantly differ from white men in their support for a female president (Sigelman & Welch, 1984 ). In the United States, there has been considerable research and polling that finds men are less likely to believe women are suitable for politics, particularly in higher levels of executive office. Men are less likely to report willingness to vote for a woman for president (Dolan, 2004 ; Lawless, 2004 ) and are less likely to report voting for a woman for the House of Representatives (Dolan, 2004 ). Controlling for a number of other demographic and attitudinal variables, men are more likely to believe that men are better suited to handle a military crisis, to punish terrorists, to prevent terrorism, and to bring peace in the Middle East (Lawless, 2004 ). Analysis of 2000 National Annenberg Election Survey data finds that men were less likely than women to be favorable toward a female president (Kenski & Falk, 2004 ). Finally, men were less likely to vote for Hillary Clinton for president (Burden, Crawford, & DeCrescenzo, 2016 ).

Gender Differences in Political Attitudes

As noted in the prior section, gender has an effect on shaping women’s and men’s attitudes on sexism, feminism, and gender roles. Gender also has a strong effect on shaping men’s and women’s attitudes and issue preferences with gender differences in ideology, party identification, vote choice, and public opinion across several issue areas consistently arising. In the following sections is, first, a summary of the literature on how women are more likely to identify as liberal, to identify as Democrat, and to vote for Democratic candidates. Second, there is an overview of gender differences in policy preferences. Third, there is a critical discussion of existing and potential explanations for gender differences in attitudes and policy preferences.

Gender influences political ideology, party identification, and vote choice. The gender gap in ideology is also a modest gap, in which women tend to identify as more liberal than men (Condon & Wichowsky, 2015 ; Norrander & Wilcox, 2008 ). Well-educated and single women are more likely to identify as liberal, and religiosity predicts conservatism for men and women (Norrander & Wilcox, 2008 ). Abortion and gender role attitudes contribute more to women’s ideology, while social welfare issues contribute more to men’s ideology (Norrander & Wilcox, 2008 ). In contrast, other research finds evidence that the gender gap in ideology results from differences in opinion, not differential prioritizing or weighting of issues (Condon & Wichowsky, 2015 ). In other words, men are more ideologically conservative than women because of different policy preferences, not because men and women differ in how they connect issue positions to ideology with positions on social welfare and abortion contributing equally to men’s and women’s ideological constructs (Condon & Wichowsky, 2015 ). Finally, ideological differences exist among partisans. Within the Republican primary electorate, men are more likely to describe themselves as conservative and women are more likely to identify as moderates (Norrander, 2003 ).

Party Identification

Consistent gender differences in party identification exist, with women more likely to identify with the Democratic Party (Huddy, Cassese, & Lizotte, 2008b ). Additionally, there are gender differences in the propensity to identify with a party at all. Men are more likely than women to identify as Independents (Norrander, 1997 ). Women are more likely to identify as weak partisans, while men identify as leaning Independents (Norrander, 1997 , 2003 ). This has consequences for the partisan gap overall. Failing to take into account the leaning Independents makes the gender gap in partisanship appear to be caused by women’s attraction to the Democratic Party; including leaning Independents shows the partisan gap to be equally due to men’s attraction to the Republican Party and women’s attraction to the Democratic Party (Norrander, 1997 ). Other research argues that the evidence suggests the partisan gender gap is mostly the result of white men leaving the Democratic Party (Kaufmann & Petrocik, 1999 ; Norrander, 1999 ). The most recent analysis finds that the gender in partisanship appears to be the result of both men’s and women’s response to the symbolic images of the political parties, including the gender make-up of congressional delegations and partisan realignments, not simply men’s movement away from the Democratic Party as earlier work often claimed (Ondercin, 2017 ).

Vote Choice

According to analysis of cumulative ANES data ( 1980–2004 ), women are consistently more likely to vote for the Democratic presidential nominee over the Republican (Huddy et al., 2008b ). The gender gap in vote choice exists across several demographic groups (Clark & Clark, 2009 ; Huddy et al., 2008b ). For example, in the 1980 presidential election, women were more likely than men to vote for Carter across most income categories, among all education levels, regardless of union membership, among all racial/ethnic groups, regardless of parental status, among all ages, and across all regions (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). Similar findings exist for presidential vote choice for the 1996 , 2000 , and 2004 elections (Clark & Clark, 2009 ) as well as the 2016 election, which featured a woman major-party candidate (Burden, Crawford, & DeCrescenzo, 2016 ). Gender gaps even emerge within parties; women and men within the same party primaries tend to support different candidates on average (Norrander, 2003 ). For example, in the 2000 presidential primaries, female Democrats were more likely to vote for Gore in comparison to male Democrats, who were more likely to vote for Bradley, and female Republicans were more likely to vote for George W. Bush compared to male Republicans, who were more likely to vote for McCain (Norrander, 2003 ). This was also true in the 2016 presidential primaries, with female Democrats more likely to vote for Clinton and male Democrats more likely to vote for Sanders and female Republicans being consistently less likely than male Republicans to vote for Trump (Presidential Gender Watch, 2016 ). In Europe, women also tend to vote for left-leaning political parties (Abendschön & Steinmetz, 2014 ; Annesley & Gains, 2014 ; Emmenegger & Manow, 2014 ; Harteveld & Ivarsflaten, 2016 ; Immerzeel, Coffé, & Van der Lippe, 2015 ). 2

Issue Preferences

There are gender gaps on various policy issues, including the domestic and international use of force, compassion issues such as social welfare spending, equal rights, and government spending more broadly. Women are consistently more liberal on all of these policies, but the size of gender differences vary. Gender differences on the use of force, social welfare, equal rights, the environment, and morality have been the gaps most studied in the literature. Gender gaps in policy preferences are politically consequential. These issue gaps contribute to the gender gap in voting (Chaney, Alvarez, & Nagler, 1998 ; Clark & Clark, 2009 ). Moreover, the gender gap in party identification does not completely account for the gender gap in vote choice (Kaufmann & Petrocik, 1999 ). In recent elections, women have turned out to vote at consistently higher levels than men, increasing the likelihood that these opinion differences could be politically consequential (CAWP, 2015 ). Hence, a gender gap on a single issue, especially a salient issue, could have significant electoral effects.

Use of Force Attitudes

There are robust gender differences on support for the use of force, with women less likely to support the use of force both internationally and domestically. Women are less likely to support defense spending and the use of the military to solve international crises. The gap on defense spending and use of the military was 10 percentage points and 5 percentage points in 1996 and 10 percentage points and 7 percentage points in 2004 (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). Differences on support for war in the abstract, troops in Afghanistan, and military intervention in Libya also appear to exist outside of the United States but considerably vary in size across Europe and Turkey, ranging from 0 to 23 percentage points (Eichenberg & Read, 2016 ). Gender differences on the use of international force do not always materialize outside of the United States. For example, only women in the United States have greater support for peacekeeping forces in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and greater favorability for the United Nations (Eichenberg & Read, 2016 ). Moreover, the gender gap on the use of military force consistently fails to appear in the Middle East (Ben Shitrit, Elad-Strenger, & Hirsch-Hoefler, 2017 ; Tessler, Nachtwey, & Grant, 1999 ). Finally, women are also less likely to support the use of torture to prevent terrorist attacks (Lizotte, 2017a ).

With respect to domestic force issues, women are also more supportive of gun control and less supportive of the death penalty. The gap on gun control was 23 percentage points and the gap on the death penalty was 8 percentage points in the 1996 ANES, and in the 2004 ANES the gaps were 19 percentage points and 9 percentage points, respectively (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). Women are consistently less likely than men to support the death penalty (Stack, 2000 ; Whitehead & Blankenship, 2000 ). Many studies show a robust gender gap on gun control (Filindra & Kaplan, 2016 ; Haider-Markel & Joslyn, 2001 ; Howell & Day, 2000 ), with women being less likely to own a gun and less likely to see owning a gun as a means of self-protection (Kleck, Gertz, & Bratton, 2009 ). There are, however, important differences in terms of party identification and ideology in support for the death penalty and gun control among women—women, who identify as Democrats and liberals, are more likely than Republican and conservative women to oppose the death penalty and to support gun control (Deckman, 2016 ).

Social Welfare Attitudes

Women are generally more supportive of social welfare spending and domestic spending on services. Generally, women are more supportive of a bigger government with a more activist role (Fox & Oxley, 2015 ). Social welfare issues include support for increased government spending on Social Security, the homeless, welfare, food stamps, child care, aid to the poor, and schools as well as government guaranteeing jobs, providing more services, and providing health insurance (Clark & Clark, 1996 , 2008 ; Howell & Day, 2000 ; Kaufmann & Petrocik, 1999 ). Women are also more likely than men to support the Affordable Care Act (Lizotte, 2016a ). Recent analysis finds small and consistent gender differences on government provision of services, government-guaranteed jobs, government-guaranteed standard of living, government provision of health insurance, and increased government spending on public schools, child care, social security, welfare aid to the poor, and food stamps (Fox & Oxley, 2015 ). Not all women are supportive of increased government aid to the poor; in particular, Tea Party women and Republican women are less supportive than women nationally (Deckman, 2012 ).

These gaps differ in size across these varied issue areas and are generally robust to the inclusion of control variables. For example, on government-funded health insurance and government-guaranteed jobs, the gap ranges from 4 to 5 percentage points (Clark & Clark, 1996 ). In contrast, on Social Security spending the gap has been much larger at 14 or 15 percentage points (Clark & Clark, 1996 ). Spending on the poor, welfare, food stamps, and the homeless tends to produce gaps of 4 to 7 percentage points (Kaufmann & Petrocik, 1999 ). The gap on social welfare spending has recently been the second largest opinion gap at around 10 percentage points (Norrander, 2008 ). These gaps remain significant, controlling for educational attainment, marital status, income, children, age, cohort, occupational status, party identification, religious identification, parental status, and race (Howell & Day, 2000 ; Lizotte, 2017b ). Gender differences on income inequality, however, do not exist in many countries outside of the United States and Western Europe (Jaime-Castillo, Fernández, Valiente, & Mayrl, 2016 ).

Minority Rights Attitudes

There is less consistent evidence of gender differences on racial policy or racial attitudes. In the 1996 ANES and in the 2004 ANES, the gender gap on support for government aid to blacks was only 3 percentage points (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). There appears to be a 4 or 5 percentage point gender gap in support for government spending to help blacks (Clark & Clark, 1996 ; Kaufmann & Petrocik, 1999 ). Women are slightly more likely to support affirmative action (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). For support of affirmative action, the gap for jobs is 4 to 6 percentage points, while support for education quotas results in a 9 percentage point difference, both without control variables (Clark & Clark, 1996 ). Much of the research finds that the gender gap no longer exists when control variables and/or party identification are included (Howell & Day, 2000 ; Hughes & Tuch, 2003 ).

Women are more supportive of gay rights than men. Women are more likely to support civil rights for gays (Clark & Clark, 1996 ; Herek, 2002 ). Women are more supportive of consensual sexual relations between same-sex partners being legal, gay adoption rights, the right to serve in the military, and employment protections (Brewer, 2003 ; Clark & Clark, 2009 ; Herek, 2002 ; Stoutenborough, Haider-Markel, & Allen, 2006 ). Women are more likely to support equal rights and to support same-sex marriage controlling for various demographic and religious variables (Haider-Markel & Joslyn, 2008 ). Of course, not all women are supportive of gay rights; Republican women and Tea Party women are less favorable toward gay rights than women as a whole (Deckman, 2012 ).

Environmental Attitudes

Gender differences often emerge on environmental policy preferences. Women are more likely to support environmental protections even if it reduces the number of jobs (Clark & Clark, 2009 ). Conservative women are less likely compared to women nationally to support environmental protections (Deckman, 2012 ). There is also a gender gap on environmental concern (McCright, 2010 ; Mohai, 1992 ). The gap remains significant when demographic variables, ideology, party identification, knowledge about climate change, and parenthood/motherhood are controlled for in the analysis (McCright, 2010 ; Mohai, 1992 ). This gap is not as big as the gaps on the use of force or some of the social welfare gaps. Women are more likely by 5 percentage points to believe global warming is occurring and are more likely by 8 percentage points to believe that humans are causing it (McCright, 2010 ). Women also express by 6 percentage points greater worry about global warming and are more likely by 9 percentage points to believe that it will threaten their way of life (McCright, 2010 ). Additionally, women are more likely to agree that climate change will cause coastal flooding, drought, and loss of animal and plant species (Blocker & Eckberg, 1997 ).

Religiosity and Morality Attitudes

There are gender differences in religiosity, religious fundamentalism, commitment to religion, and frequency of religious behaviors, with women being more religious than men (Cook & Wilcox, 1991 ; Tolleson-Rinehart & Perkins, 1989 ). Republican women and Tea Party women are more religious than women as a whole (Deckman, 2012 ). This could translate into policy preferences. Women are more supportive of school prayer, more opposed to the legalization of marijuana, and more supportive of legal access restrictions on pornography (Eagly, Diekman, Johannesen-Schmidt, & Koenig, 2004 ). Religious belief does not always influence women to be more conservative on moral issues (e.g., the gender gap on gay rights). Gender differences in religiosity and traditional morality may be due to gender role socialization that promotes traits such as passivity and obedience in women (Thompson, 1991 ) or that prepares women for the role of motherhood in which they have the primary responsibility for the moral development of children (Eagly et al., 2004 ).

Gender differences on reproductive issues, which are often framed as morality issues, tend to be small and inconsistent in comparison to other gender gaps. Gender differences do not always emerge on abortion legality—it appears to depend on how abortion attitudes are modeled. In particular, if religious and religiosity indicators are included, women are more likely to support legality under all circumstances (Lizotte, 2015 ). Women are more likely to believe that abortion is morally wrong (Scott, 1989 ). No gender differences exist on the influence of abortion attitudes on party identification or vote choice (Lizotte, 2016b ). Relatedly, women were more likely to support the birth control mandate included in the Affordable Care Act, but men and women were both likely to have their support influence their 2012 presidential vote choice (Deckman & McTague, 2014 ).

Explanations

There are several explanations for gender differences in political attitudes and behavior, with varying levels of evidence to support each one. Examining the different theories put forth in the literature is integral to understanding how and why gender influences political attitudes. The following theories exist in the literature: Feminist Identity, Economic Circumstances, Social Role Theory and Motherhood, Risk and Threat Perceptions, Personality, and Values. There are varying degrees of support for each of these explanations. These explanations are not mutually exclusive, and it may be that more than one explanation simultaneously contributes to each gap, or that different explanations explain different gaps.

Feminist Identity

First, there is the feminist identity or feminist consciousness explanation. There are several different types of feminism, but commonalities exist across the different forms. Specifically, most types of feminism include the following: a belief in sex/gender equality; the belief that historical gender equality is socially constructed and not natural or intended by God; and the recognition of shared experience among women, which ought to inspire a longing for change (Cott, 1987 ). Evidence exists that feminist identity contributes to gender differences on defense spending, environmental attitudes, social welfare spending, and anti-war attitudes (Conover, 1988 ; Conover & Sapiro, 1993 ; Cook & Wilcox, 1991 ; Feinstein, 2017 ; Somma & Tolleson-Rinehart, 1997 ). Early work investigating this explanation finds a link between feminist consciousness and gender gaps on unemployment spending, child care spending, equal opportunity for African Americans, and foreign policy positions (Conover, 1988 ). Much of this research argues that feminist identity likely has an indirect influence on political attitudes and behavior. This research finds that feminist identity correlates with lower endorsement of traditionalism, individualism, and symbolic racism as well as greater endorsement of egalitarianism (Conover, 1988 ; Cook & Wilcox, 1991 ).

Economic Circumstances

Second, there are two economic explanations in the literature: economically independent women or economically vulnerable women are causing gender differences. Economically independent women are more likely than men to work in the public sector, such as in public schools and as health providers, and consequently would be more likely to support the Democratic Party, which is perceived as wanting to maintain or increase funding for that sector (Huddy et al., 2008b ). There is mixed evidence for this explanation. In 1980–2004 ANES data, professional and high-income women are not significantly more likely to vote or identify as Democrats (Huddy et al., 2008b ). Increases in women’s workforce participation explains the gender gap in presidential vote choice in the ANES 1952–1992 data (Manza & Brooks, 1998 ). Educated women as well as women and men working in the public sector are more likely to support social welfare spending, the men even more than the women (Howell & Day, 2000 ).

Economically vulnerable women may support the Democratic Party and greater government spending on social welfare programs because of the potential for them to benefit from such policies and spending. Additionally, economically vulnerable women may oppose defense spending and military interventions because it could lead to less funding of the welfare state. There is moderate evidence for this explanation in that income level is a predictor but does not fully account for gender differences in the following research. In some years but not all of the ANES 1980–2004 , low-income women are more likely to identify as and vote for Democrats (Huddy et al., 2008b ). Time-series analysis shows an association at the aggregate level between the size of the partisan gap and the proportion of economically vulnerable (Box-Steffensmeier, De Boef, & Lin, 2004 ). Low income explains some but not all of the gender differences in wanting more government services and spending (Clark & Clark, 2009 ) and in support for the Affordable Care Act (Lizotte, 2016a ). Finally, low-income individuals are less supportive of military interventions (Nincic & Nincic, 2002 ), but equalizing men’s and women’s income would only reduce the gender gap by about 9% (Feinstein, 2017 ).

Social Role Theory and Motherhood

Third, there is the Social Role Theory explanation, which posits that gender gaps result from gender role socialization (Diekman & Schneider, 2010 ; Eagly et al., 2004 ). Social Role Theory argues for an interaction between the physical characteristics and the features of the local environment leading to a particular male–female division of labor in a given society. Consequently, this division of labor brings about certain gender roles and gender socialization of agentic traits among males and communal traits among females (Eagly & Wood, 2012 ). Communal traits include anti-conflict and nurturance, and agentic traits include aggression and assertiveness. Therefore, women’s anti-force and pro-equality attitudes fit with these gendered socialized traits (Eagly et al., 2004 ). It is somewhat difficult to test this explanation because of the assumption that the vast majority of individuals will receive the same gendered socialization within a given society. Motherhood, however, predicts greater support for aid to the poor, government healthcare, child care spending, public school spending, preference for greater government services, and food stamp spending (Elder & Greene, 2007 ; Greenlee, 2014 ; Howell & Day, 2000 ; Lizotte, 2017b ). These findings show that motherhood contributes to these gaps but does not fully explain the gender differences. Motherhood also predicts opposition to the legalization of marijuana (Deckman, 2016 ; Greenlee, 2014 ); in a piece employing 2013 Pew Research Center data, however, motherhood actually does not predict attitudes toward the legalization of marijuana (Elder & Greene, 2019 ). There is no evidence that mothers are causing gender differences on security and foreign policy (Carroll, 2008 ; Elder & Greene, 2007 ).

Relatedly, gender identity, which may vary as a result of differences in gendered socialization, and the salience of gender identity produce even stronger gender differences in public opinion. In a Canadian sample, greater gender identity salience predicts increased support for social programs, welfare spending, marriage equality, and women in the legislature (Bittner & Goodyear-Grant, 2017a ). Similarly, in an Australian twin study sample, gender identity had a greater influence on vote choice than sex (Hatemi, McDermott, Bailey, & Martin, 2012 ). Sex, however, approximates gender identity well for most people except about a quarter (Bittner & Goodyear-Grant, 2017b ).

Risk and Threat Perceptions

Fourth, gender differences in risk and threat perceptions are a promising, potential explanation for the gender gap in force and environmental attitudes. There is a lot of evidence that women and men differ in risk perceptions. Although men and women often perceive the same things as risky, women perceive greater risk than men with regard to the same risky event or behavior (Gustafsod, 1998 ). Women perceive greater risks than do men in four out of five domains and are less likely than men to report engaging in risky behaviors (Weber, Blais, & Betz, 2002 ). The extant literature provides much evidence of gender differences in risk aversion. Women tend to be more risk averse or avoidant of risky behavior (Byrnes, Miller, & Schafer, 1999 ); this difference even appears to exist between male and female children (Ginsburg & Miller, 1982 ). Women are more likely to feel anxious in response to terrorism and, therefore, be more risk averse about retaliatory measures (Huddy, Feldman, & Cassese, 2009 ). Increased threat perceptions of future terrorist attacks lead men to be more likely to support the use of torture, while perceived threat does not increase women’s support for torture (Lizotte, 2017a ). In non–gender focused work, threat perceptions and risk orientations influence policy views and vote choice (Huddy, Feldman, Taber, & Lahav, 2005 ; Huddy, Feldman, & Weber, 2007 ; Kam & Simas, 2010 , 2012 ).

Relatedly in the biopsychology literature, Taylor and colleagues ( 2000 ) provide a compelling theory based on prior research that women are less likely than men to respond to stress in terms of “fight or flight.” They argue that women’s response to stress is better characterized as “tend and befriend.” Evolutionarily, women have been the primary caregivers of offspring. Taylor et al. ( 2000 ) argue that to prevent harm to themselves and offspring, women may have evolved to tend, which they define as keeping offspring quiet in order to hide from threat, and befriend, which they describe as building networks and making effective use of social groups to provide aid and protection during stressful or threatening times. The idea that women do not exhibit the “fight-or-flight” response could explain why they respond differently than men to threat such as force-related issues.

Personality Traits

Fifth, personality traits is for the most part an untested theory for gender differences in political attitudes. The Big Five Personality Traits, including neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness, constitute a widely accepted measure (Goldberg, 1993 ). Studies of the Big Five Personality Traits have found significant, though small, average gender differences in self-reported traits. Meta-analysis found gender differences across cultures on subcomponents of neuroticism, agreeableness, extraversion, and openness to experience (Costa, Terracciano, & McCrae, 2001 ). Specifically, women score higher on anxiety, a subcomponent of neuroticism; higher on altruism, a subcomponent of agreeableness; lower on assertiveness/dominance, a subcomponent of extraversion; and higher on the feelings subcomponent of openness to experience (Costa et al., 2001 ). These differences in personality could explain many gaps in political decision making. Ideological differences among men and women appear to exist partially because of women being more open to experience, more agreeable, and more emotionally stable than men (Morton, Tyran, & Wengström, 2016 ). Agreeableness appears to have differing consequences for men and women’s partisanship, with increased agreeableness among men being associated with Democratic Party identification and among women with Republican Party identification (Wang, 2017 ). More research on personality and political attitudes could be informative. For example, anxiety and assertiveness differences may explain women’s lower support for military interventions and their greater concerns about climate change. There is a link between altruism and women’s concern about the environment (Dietz, Kalof, & Stern, 2002 ). Altruism may also explain women’s higher levels of support for social welfare spending and equal rights for African Americans and the LGBTQ+ community.

Sixth, value differences offer another explanation for gender gaps in political attitudes. Values are more abstract than attitudes, making them applicable across different attitude objects, and are evaluative expressions of desired behaviors and goals for individuals and society (Feldman, 2003 ). Prior work provides evidence that values such as egalitarianism, humanitarianism, and militarism influence political attitudes (Peffley & Hurwitz, 1985 ; Schwartz, Caprara, & Vecchione, 2010 ). Schwartz ( 1992 ) developed the study of values through the examination of 10 value types, each of which is a set of values that are closely linked conceptually. According to Schwartz, values such as social justice, equality, tolerance, and peace belong to one of 10 key value types known as universalism. The other 9 types are benevolence, tradition, conformity, security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction.

There are modest gender differences in value endorsements (Feldman & Steenbergen, 2001 ; Howell & Day, 2000 ; Schwartz & Rubel, 2005 ). For example, gender differences exist on benevolence, which measures individuals’ concern for the welfare of others; on power, which encompasses a desire for control of others; and all of the other types (Schwartz & Rubel, 2005 ). Benevolence and universalism could explain gender differences on aid to the poor and environmental protections, while power and security could explain differences in support for the use of force. Women also score higher on measures of egalitarianism (Feldman & Steenbergen, 2001 ; Howell & Day, 2000 ). Value differences reduce the gap on social welfare attitudes, gun control attitudes, and support for the Affordable Care Act (Howell & Day, 2000 ; Lizotte, 2016a ).

Future Directions and Conclusions

Gender is an important factor in understanding attitudes toward women, including sexism and feminist identity, and gender differences in political decision making, such as gender differences in ideology, party identification, vote choice, and issue positions. Future work is needed to better understand the sources and effects of attitudes toward women and to further comprehend the origins and consequences of gender differences in political decision making.

There is little known about the political leanings of those with sexist attitudes or traditional gender role attitudes. For example, are those endorsing hostile sexism more likely to identify as Republican compared to those endorsing benevolent sexism? Do women who score higher on sexism measures identify as Republican? Presumably, the answer to both of these questions is yes because of the overlap between the GOP and conservative ideology. Anti-feminist women are more likely to identify as Republican (Huddy & Willmann, 2017 ). There is some evidence that in 2016 and in 2012 , among men, sexism predicts support for Republican presidential candidates (Blair, 2017 ; Bock et al., 2017 ; Cassese & Holman, 2016 ; Simas & Bumgardner, 2017 ; Valentino et al., 2018 ). In addition, men, whites, and Republicans have higher scores on measures of sexism compared to women, non-whites, and Democrats (Simas & Bumgardner, 2017 ). More research in this area should further explore the electoral consequences of sexism and feminist identity. It would also be of value to understand how these attitudes relate to policy preferences. One recent piece finds that support for traditional roles for women is associated with opposition to abortion legality and support for the War in Iraq; modern sexism also predicts opposition to abortion, opposition to job discrimination protections for women, and support for the Iraq War (Burns et al., 2016 ). The Attitudes Toward Women Scale and other sexism measures could also predict positions on a wide range of policies such as child care spending, insurance coverage of birth control, equal pay, sexual harassment, and Title IX. Additionally, it is unclear what the implications of these types of attitudes are for voter decisions, in particular for female candidates. There is some recent work finding that modern sexism and hostile sexism predict greater favorability of and a greater likelihood of voting for Donald Trump in the 2016 presidential election (Blair, 2017 ; Bock et al., 2017 ; Cassese & Holman, 2016 ; Valentino et al., 2018 ). More of the work on voter evaluations of female candidates should strive to measure attitudes toward women. In fact, similar items have been included in the 2016 ANES and presumably will provide insight into presidential and congressional vote choice.

With respect to how gender influences political attitudes, there are a number of unanswered questions. First, there is very little research looking at the gender gap in public opinion among African Americans (for exceptions, see Lien, 1998 ; Welch & Sigelman, 1989 ). There is a great deal of research that looks at gender differences in public opinion and controls for race. There is emerging evidence that black women are more likely to turn out to vote than black men, as well as the fact that according to exit polls, black men were more likely than black women to vote for Trump in 2016 (Dittmar & Carr, 2016 ). This suggests that there may be gender differences in policy preferences among African Americans. There is also work showing gender differences among Latinos in public opinion and ideology (Bejarano, 2014 ; Bejarano, Manzano, & Montoya, 2011 ). Lack of existing data is likely one of the most prominent reasons for the lack of research. It would be of interest to better understand how gender intersects with race/ethnicity when it comes to policy preferences.

Second, it is clear that gender differences in political attitudes are not the result of biological factors. The essentialist notion that all women are born more caring or conflict-avoidant is not borne out in the modestly to moderately sized gaps that exist in public opinion. This approach should simply be put to rest. Relatedly, via gendered socialization and/or because of lived experiences, men and women on average differ slightly in their positions on a number of issues. It would be quite beneficial to further investigate to what extent gendered socialization versus lived experiences explains these gaps. Perhaps including measures of each one in future survey collections could provide insight. For example, are women, who support greater government aid to the needy, more likely to have been raised to care and nurture others through playing with dolls? Or are women, who are opposed to military interventions, past victims or observers of violence, making them reluctant to use violent means to solve conflict?

Third, further research is needed to understand the usefulness of the personality and values explanations discussed here. It may be the case that gender differences in altruism lead to greater support for government aid to the poor. Or, that differences in the power value type account for the gap in gun control attitudes. The 2012 ANES data include a short personality inventory. The inclusion of values beyond egalitarianism in nationally representative data sets would make it possible to better investigate the values explanations. Finally, for both of these explanations (but also for the others discussed throughout), more work is needed to understand how multiple explanations may simultaneously contribute. For example, altruism as a personality trait may lead to greater endorsement of humanitarianism, which then contributes to the gender gap on aid to the poor.

- Abendschön, S. , & Steinmetz, S. (2014). The gender gap in voting revisited: Women’s party preferences in a European context. Social Politics , 21 (2), 315–344.

- Annesley, C. , & Gains, F. (2014). Can Cameron capture women’s votes? The gendered impediments to a conservative majority in 2015. Parliamentary Affairs , 67 (4), 767–782.

- Barreto, M. , & Ellemers, N. (2005). The perils of political correctness: Men’s and women’s responses to old-fashioned and modern sexist views. Social Psychology Quarterly , 68 (1), 75–88.

- Beinart, P. (2017, December 15). The growing partisan divide over feminism . The Atlantic .

- Bejarano, C. E. (2014). Latino gender and generation gaps in political ideology. Politics & Gender , 10 (1), 62–88.

- Bejarano, C. E. , Manzano, S. , & Montoya, C. (2011). Tracking the Latino gender gap: Gender attitudes across sex, borders, and generations. Politics & Gender , 7 (4), 521–549.

- Ben Shitrit, L. , Elad-Strenger, J. , & Hirsch-Hoefler, S. (2017). Gender differences in support for direct and indirect political aggression in the context of protracted conflict. Journal of Peace Research , 54 (6), 733–747.

- Bittner, A. , & Goodyear-Grant, E. (2017a). Digging deeper into the gender gap: Gender salience as a moderating factor in political attitudes. Canadian Journal of Political Science/Revue canadienne de science politique , 50 (2), 559–578.

- Bittner, A. , & Goodyear-Grant, E. (2017b). Sex isn’t gender: Reforming concepts and measurements in the study of public opinion. Political Behavior , 39 (4), 1–23.

- Blair, K. L. (2017). Did Secretary Clinton lose to a “basket of deplorables”? An examination of Islamophobia, homophobia, sexism and conservative ideology in the 2016 US presidential election. Psychology & Sexuality , 8 (4), 334–355.

- Blocker, T. J. , & Eckberg, D. L. (1997). Gender and environmentalism: Results from the 1993 general social survey. Social Science Quarterly , 78 (4), 841–858.

- Bock, J. , Byrd-Craven, J. , & Burkley, M. (2017). The role of sexism in voting in the 2016 presidential election. Personality and Individual Differences , 119 , 189–193.

- Bolzendahl, C. I. , & Myers, D. J. (2004). Feminist attitudes and support for gender equality: Opinion change in women and men, 1974–1998. Social Forces , 83 (2), 759–789.

- Box-Steffensmeier, J. M. , De Boef, S. , & Lin, T. M. (2004). The dynamics of the partisan gender gap. American Political Science Review , 98 (03), 515–528.

- Brandt, M. J. (2011). Sexism and gender inequality across 57 societies. Psychological Science , 22 (11), 1413–1418.

- Brewer, P. R. (2003). The shifting foundations of public opinion about gay rights. Journal of Politics , 65 (4), 1208–1220.

- Brewster, K. L. , & Padavic, I. (2000). Change in gender‐ideology, 1977–1996: The contributions of intracohort change and population turnover. Journal of Marriage and Family , 62 (2), 477–487.

- Burden, B. C. , Crawford, E. , & DeCrescenzo, M. G. (2016, December). The unexceptional gender gap of 2016. The Forum , 14 (4), 415–432.

- Burns, N. , Jardina, A. E. , Kinder, D. , & Reynolds, M. E. (2016). The politics of gender. In A. J. Berinsky (Ed.), New directions in public opinion (2nd ed., pp. 124–145). New York: Routledge.

- Burns, N. , Schlozman, K. L. , & Verba, S. (1997). The public consequences of private inequality: Family life and citizen participation. American Political Science Review , 91 (2), 373–389.

- Byrnes, J. P. , Miller, D. C. , & Schafer, W. D. (1999). Gender differences in risk taking: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin , 125 (3), 367.

- Carey, T. E., Jr. , & Lizotte, M. K. (2017). Political experience and the intersection between race and gender . Politics, Groups, and Identities , 1–24.

- Carroll, S. J. (2008). Security moms and presidential politics: Women voters in the 2004 election. In L. D. Whitaker (Ed.), Voting the gender gap (pp. 75–90). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Carter, S. J. , Corra, M. , & Carter, S. K. (2009). The interaction of race and gender: Changing gender‐role attitudes, 1974–2006. Social Science Quarterly , 90 (1), 196–211.

- Cassese, E. C. , & Holman, M. R. (2016). Playing the gender card: Ambivalent sexism in the 2016 presidential race . Unpublished manuscript.

- Center for American Women and Politics . (2012). The gender gap: Attitudes on public policy issues .

- Center for American Women and Politics . (2015). Gender differences in voter turnout .

- Chaney, C. K. , Alvarez, R. M. , & Nagler, J. (1998). Explaining the gender gap in US presidential elections, 1980–1992. Political Research Quarterly , 51 (2), 311–339.

- Clark, C. , & Clark, J. (1996). Whither the gender gap? Converging and conflicting attitudes among women. In L. L. Duke (Ed.), Women in politics: Outsiders or insiders? (2nd ed., pp. 78–99). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Clark, C. , & Clark, J. (2009). Women at the polls: The gender gap, cultural politics, and contested constituencies in the United States . Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Clark, C. , & Clark, J. M. (2008). The reemergence of the gender gap in 2004. In L. D. Whitaker (Ed.), Voting the gender gap (pp. 50–74). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Condon, M. , & Wichowsky, A. (2015). Same blueprint, different bricks: Reexamining the sources of the gender gap in political ideology. Politics, Groups, and Identities , 3 (1), 4–20.

- Conover, P. J. (1988). Feminists and the gender gap. The Journal of Politics , 50 (4), 985–1010.

- Conover, P. J. , & Sapiro, V. (1993). Gender, feminist consciousness, and war. American Journal of Political Science , 37 (4), 1079–1099.

- Cook, E. A. , & Wilcox, C. (1991). Feminism and the gender gap—a second look. The Journal of Politics , 53 (4), 1111–1122.

- Costa, P. T. , Terracciano, A. , & McCrae, R. R. (2001). Gender differences in personality traits across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 81 (2), 322–331.

- Cott, N. F. (1987). The grounding of modern feminism . New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Davis, S. N. , & Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology , 35 , 87–105.

- Deckman, M. (2012). Of mama grizzlies and politics: Women and the Tea Party. In L. Rosenthal & C. Trost (Eds.), Steep: The precipitous pise of the Tea Party (pp. 171–191). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Deckman, M. (2016). Tea Party women: Mama grizzlies, grassroots leaders, and the changing face of the American right . New York: NYU Press.

- Deckman, M. , & McTague, J. (2014, July 3). The Affordable Care Act’s birth control mandate was an important factor in Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection . LSE American Politics and Policy .

- Diekman, A. B. , & Schneider, M. C. (2010). A social role theory perspective on gender gaps in political attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 34 (4), 486–497.

- Dietz, T. , Kalof, L. , & Stern, P. C. (2002). Gender, values, and environmentalism. Social Science Quarterly , 83 (1), 353–364.

- Dittmar, K. , & Carr, G. (2016). Black women voters: By the numbers . HuffPost Blog.

- Dolan, K. A. (2004). Voting for women: How the public evaluates women candidates . Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Downs, A. C. , & Engleson, S. A. (1982). The Attitudes Toward Men Scale (AMS): An analysis of the role and status of men and masculinity. Catalog of Selected Documents in Psychology , 12 (4), 45, (Ms. No. 2503).

- Eagly, A. H. , Diekman, A. B. , Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C. , & Koenig, A. M. (2004). Gender gaps in sociopolitical attitudes: A social psychological analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 87 (6), 796–816.

- Eagly, A. H. , & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. In A. W. Kruglanski , P. A. M. Van Lange , & T. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 458–476). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Eichenberg, R. C. , & Read, B. M. (2016). Gender difference in attitudes towards global issues. In J. Steans & D. Tepe-Belfrage (Eds.), Handbook on gender in world politics (pp. 234–244). Northhampton, MA: Edward Elgar.

- Elder, L. , & Greene, S. (2007). The myth of “security moms” and “Nascar dads”: Parenthood, political stereotypes, and the 2004 election.” Social Science Quarterly , 88 , 1–19.

- Elder, L. , & Greene, S. (2019). Gender and the Politics of Marijuana. Social Science Quarterly , 100, 109–122.

- Emmenegger, P. , & Manow, P. (2014). Religion and the gender vote gap: Women’s changed political preferences from the 1970s to 2010. Politics & Society , 42 (2), 166–193.

- Fassinger, R. E. (1994). Development and testing of the Attitudes Toward Feminism and the Women’s Movement (FWM) Scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 18 (3), 389–402.

- Feinstein, Y. (2017). The rise and decline of “gender gaps” in support for military action: United States, 1986–2011. Politics & Gender , 13 (4), 618–655.

- Feldman, S. (2003). Values, ideology, and the structure of political attitudes. In D. O. Sears , L. Huddy , & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 477–508). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Feldman, S. , & Steenbergen, M. R. (2001). The humanitarian foundation of public support for social welfare. American Journal of Political Science , 45 (3), 658–677.

- Filindra, A. , & Kaplan, N. J. (2016). Racial resentment and whites’ gun policy preferences in contemporary America. Political behavior , 38 (2), 255–275.

- Ford, L. E. (2017). Women and politics: The pursuit of equality (4th ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Fox, R. L. , & Oxley, Z. M. (2015). Women’s support for an active government. In K. L. Kreider & T. J. Baldino (Eds.), Minority voting in the United States (pp. 148–167). Santa Barbara: Praeger.

- Fraser, G. , Osborne, D. , & Sibley, C. G. (2015). “We want you in the workplace, but only in a skirt!” Social dominance orientation, gender-based affirmative action and the moderating role of benevolent sexism. Sex Roles , 73 (5–6), 231–244.

- Ginsburg, H. J. , & Miller, S. M. (1982). Sex differences in children’s risk-taking behavior. Child Development , 53(2), 426–428.

- Glick, P. , Diebold, J. , Bailey-Werner, B. , & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin , 23 (12), 1323–1334.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 70 (3), 491.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 21 (1), 119–135.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The Ambivalence Toward Men Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 23 (3), 519–536.

- Glick, P. , & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist , 56 (2), 109–118.

- Goldberg, L. R. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist , 48 (1), 26.

- Greenlee, J. S. (2014). The political consequences of motherhood . Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Gustafsod, P. E. (1998). Gender differences in risk perception: Theoretical and methodological perspectives. Risk Analysis , 18 (6), 805–811.

- Haider-Markel, D. P. , & Joslyn, M. R. (2001). Gun policy, opinion, tragedy, and blame attribution: The conditional influence of issue frames. The Journal of Politics , 63 (2), 520–543.

- Haider-Markel, D. P. , & Joslyn, M. R. (2008). Beliefs about the origins of homosexuality and support for gay rights: An empirical test of attribution theory. Public Opinion Quarterly , 72 (2), 291–310.

- Hansen, S. B. (2016). Sex, race, gender, and the presidential vote. Cogent Social Sciences , 2 (1), 1172936.

- Harteveld, E. , & Ivarsflaten, E. (2016). Why women avoid the radical right: Internalized norms and party reputations. British Journal of Political Science , 48 (2), 1–16.

- Hatemi, P. K. , McDermott, R. , Bailey, J. M. , & Martin, N. G. (2012). The different effects of gender and sex on vote choice. Political Research Quarterly , 65 (1), 76–92.

- Herek, G. M. (2002). Gender gaps in public opinion about lesbians and gay men. Public Opinion Quarterly , 66 (1), 40–66.

- Howell, S. E. , & Day, C. L. (2000). Complexities of the gender gap. Journal of Politics , 62 (3), 858–874.

- Huddy, L. , Cassese, E. , & Lizotte, M. K. (2008a). Gender, public opinion, and political reasoning. In C. Wolbrecht , K. Beckwith , & L. Baldez (Eds.), Political women and American democracy (pp. 31–49). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Huddy, L. , Cassese, E. , & Lizotte, M. K. (2008b). Sources of political unity and disunity among women: Placing the gender gap in perspective. In L. D. Whittaker (Ed.), Voting the gender gap (pp. 141–169). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Huddy, L. , Feldman, S. , & Cassese, E. (2009). Terrorism, anxiety, and war. In W. Stritzke , S. Lewandowsky , D. Denemark , F. Morgan , & J. Clare (Eds.), Terrorism and torture: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 290–312). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Huddy, L. , Feldman, S. , Taber, C. , & Lahav, G. (2005). Threat, anxiety, and support of antiterrorism policies. American Journal of Political Science , 49 (3), 593–608.

- Huddy, L. , Feldman, S. , & Weber, C. (2007). The political consequences of perceived threat and felt insecurity. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science , 614 (1), 131–153.

- Huddy, L. , Neely, F. K. , & Lafay, M. R. (2000). Trends: Support for the women’s movement. Public Opinion Quarterly , 64 (3), 309–350.

- Huddy, L. , & Willmann, J. (2017). Partisan sorting and the feminist gap in American politics . Unpublished manuscript.

- Hughes, M. , & Tuch, S. A. (2003). Gender differences in whites’ racial attitudes: Are women’s attitudes really more favorable? Social Psychology Quarterly , 66 (4), 384–401.

- Iazzo, A. (1983). The construction and validation of attitudes toward men scale. The Psychological Record , 33 (3), 371–378.

- Immerzeel, T. , Coffé, H. , & Van der Lippe, T. (2015). Explaining the gender gap in radical right voting: A cross-national investigation in 12 Western European countries. Comparative European Politics , 13 (2), 263–286.

- Jaime-Castillo, A. M. , Fernández, J. J. , Valiente, C. , & Mayrl, D. (2016). Collective religiosity and the gender gap in attitudes towards economic redistribution in 86 countries, 1990–2008. Social Science Research , 57 , 17–30.

- Kam, C. D. , & Simas, E. N. (2010). Risk orientations and policy frames. The Journal of Politics , 72 (2), 381–396.

- Kam, C. D. , & Simas, E. N. (2012). Risk attitudes, candidate characteristics, and vote choice. Public Opinion Quarterly , 76 (4), 747–760.

- Kaufmann, K. M. , & Petrocik, J. R. (1999). The changing politics of American men: Understanding the sources of the gender gap. American Journal of Political Science , 43 (3), 864–887.

- Kenski, K. , & Falk, E. (2004). Of what is that glass ceiling made? A study of attitudes about women and the Oval Office. Women & Politics , 26 (2), 57–80.

- Kleck, G. , Gertz, M. , & Bratton, J. (2009). Why do people support gun control?: Alternative explanations of support for handgun bans. Journal of Criminal Justice , 37 (5), 496–504.

- Kroska, A. , & Elman, C. (2009). Change in attitudes about employed mothers: Exposure, interests, and gender ideology discrepancies. Social Science Research , 38 (2), 366–382.

- Lawless, J. L. (2004). Women, war, and winning elections: Gender stereotyping in the post-September 11th era. Political Research Quarterly , 57 (3), 479–490.

- Lien, P. T. (1998). Does the gender gap in political attitudes and behavior vary across racial groups? Political Research Quarterly , 51 (4), 869–894.

- Lizotte, M. K. (2015). The abortion attitudes paradox: Model specification and gender differences. Journal of Women, Politics & Policy , 36 (1), 22–42.

- Lizotte, M. K. (2016a). Investigating women’s greater support of the Affordable Care Act. The Social Science Journal , 53 (2), 209–217.

- Lizotte, M. K. (2016b). Gender, voting, and reproductive rights attitudes. In K. L. Kreider & T. J. Baldino (Eds.), Minority voting in the United States (pp. 127–147). Santa Barbara: Praeger.

- Lizotte, M. K. (2017a). Gender differences in support for torture. Journal of Conflict Resolution , 61 (4), 772–787.

- Lizotte, M. K. (2017b). The gender gap in public opinion: Exploring social role theory as an explanation. In A. L. Bos & M. C. Schneider (Eds.), The political psychology of women in U.S. Politics (pp. 51–69). New York: Routledge.

- Manza, J. , & Brooks, C. (1998). The gender gap in US presidential elections: When? Why? Implications? American Journal of Sociology , 103 (5), 1235–1266.

- McCabe, J. (2005). What’s in a label? The relationship between feminist self-identification and “feminist” attitudes among US women and men. Gender & Society , 19 (4), 480–505.

- McCright, A. M. (2010). The effects of gender on climate change knowledge and concern in the American public. Population and Environment , 32 (1), 66–87.

- McHugh, M. C. , & Frieze, I. H. (1997). The measurement of gender-role attitudes: A review and commentary. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 21 (1), 1–16.

- Mohai, P. (1992). Men, women, and the environment: An examination of the gender gap in environmental concern and activism. Society & Natural Resources , 5 (1), 1–19.

- Morton, R. , Tyran, J. R. , & Wengström, E. (2016). Personality traits and the gender gap in ideology. In M. Gallego & N. Schofield (Eds.), The political economy of social choices (pp. 153–185). Cham: Springer.

- Nincic, M. , & Nincic, D. J. (2002). Race, gender, and war. Journal of Peace Research , 39 (5), 547–568.

- Norrander, B. (1997). The independence gap and the gender gap. Public Opinion Quarterly , 61 (3), 464–476.

- Norrander, B. (1999). The evolution of the gender gap. The Public Opinion Quarterly , 63 (4), 566–576.

- Norrander, B. (2003). The intraparty gender gap: Differences between male and female voters in the 1980–2000 presidential primaries. PS: Political Science and Politics , 36 (2), 181–186.

- Norrander, B. (2008). The history of the gender gaps. In L. D. Whittaker (Ed.), Voting the gender gap (pp. 9–32). Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

- Norrander, B. , & Wilcox, C. (2008). The gender gap in ideology. Political Behavior , 30 (4), 503–523.

- Ondercin, H. L. (2017). Who is responsible for the gender gap? The dynamics of men’s and women’s democratic macropartisanship, 1950–2012. Political Research Quarterly , 70 (4), 749–761.

- Peffley, M. A. , & Hurwitz, J. (1985). A hierarchical model of attitude constraint. American Journal of Political Science , 29 , 871–890.

- Presidential Gender Watch . (2016). Exit polls .

- Rhodebeck, L. A. (1996). The structure of men’s and women’s feminist orientations: Feminist identity and feminist opinion. Gender & Society , 10 (4), 386–403.

- Rosenwasser, S. M. , Rogers, R. R. , Fling, S. , Silvers-Pickens, K. , & Butemeyer, J. (1987). Attitudes toward women and men in politics: Perceived male and female candidate competencies and participant personality characteristics. Political Psychology , 8 (2), 191–200.

- Schnittker, J. , Freese, J. , & Powell, B. (2003). Who are feminists and what do they believe? The role of generations. American Sociological Review , 68 (4), 607–622.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 25, pp. 1–65). New York: Academic Press.

- Schwartz, S. H. , Caprara, G. V. , & Vecchione, M. (2010). Basic personal values, core political values, and voting: A longitudinal analysis. Political Psychology , 31 (3), 421–452.

- Schwartz, S. H. , & Rubel, T. (2005). Sex differences in value priorities: Cross-cultural and multimethod studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 89 (6), 1010.

- Scott, J. (1989). Conflicting beliefs about abortion: Legal approval and moral doubts. Social Psychology Quarterly , 52 (4), 319–326.

- Shapiro, R. Y. , & Mahajan, H. (1986). Gender differences in policy preferences: A summary of trends from the 1960s to the 1980s. Public Opinion Quarterly , 50 (1), 42–61.

- Sigelman, L. , & Welch, S. (1984). Race, gender, and opinion toward black and female presidential candidates. Public Opinion Quarterly , 48 (2), 467–475.

- Simas, E. N. , & Bumgardner, M. (2017). Modern sexism and the 2012 US presidential election: Reassessing the casualties of the “war on women.” Politics & Gender , 13 (3), 1–20.

- Somma, M. , & Tolleson-Rinehart, S. (1997). Tracking the elusive green women: Sex, environmentalism, and feminism in the United States and Europe. Political Research Quarterly , 50 (1), 153–169.

- Spence, J. T. , & Hahn, E. D. (1997). The attitudes toward women scale and attitude change in college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly , 21 (1), 17–34.

- Spence, J. T. , Helmreich, R. , & Stapp, J. (1973). A short version of the Attitudes Toward Women Scale (AWS). Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society , 2 (4), 219–220.

- Stack, S. (2000). Support for the death penalty: A gender-specific model. Sex Roles , 43 (3), 163–179.

- Stickney, L. T. , & Konrad, A. M. (2007). Gender-role attitudes and earnings: A multinational study of married women and men. Sex Roles , 57 (11–12), 801–811.

- Stoutenborough, J. W. , Haider-Markel, D. P. , & Allen, M. D. (2006). Reassessing the impact of Supreme Court decisions on public opinion: Gay civil rights cases. Political Research Quarterly , 59 (3), 419–433.

- Swim, J. K. , Aikin, K. J. , Hall, W. S. , & Hunter, B. A. (1995). Sexism and racism: Old-fashioned and modern prejudices. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology , 68 (2), 199–214.

- Swim, J. K. , & Cohen, L. L. (1997). Overt, covert, and subtle sexism. Psychology Of Women Quarterly , 21 (1), 103–118.

- Taylor, S. E. , Klein, L. C. , Lewis, B. P. , Gruenewald, T. L. , Gurung, R. A. , & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review , 107 (3), 411–429.

- Tessler, M. , Nachtwey, J. , & Grant, A. (1999). Further tests of the women and peace hypothesis: Evidence from cross‐national survey research in the Middle East. International Studies Quarterly , 43 (3), 519–531.

- Thompson, E. H., Jr. (1991). Beneath the status characteristic: Gender variations in religiousness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion , 30 (4), 381–394.

- Tolleson- Rinehart, S. , & Perkins, J. (1989). The intersection of gender politics and religious beliefs. Political Behavior , 11 (1), 33–56.