Research Process Guide

- Step 1 - Identifying and Developing a Topic

- Step 2 - Narrowing Your Topic

- Step 3 - Developing Research Questions

- Step 4 - Conducting a Literature Review

- Step 5 - Choosing a Conceptual or Theoretical Framework

- Step 6 - Determining Research Methodology

- Step 6a - Determining Research Methodology - Quantitative Research Methods

- Step 6b - Determining Research Methodology - Qualitative Design

- Step 7 - Considering Ethical Issues in Research with Human Subjects - Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Step 8 - Collecting Data

- Step 9 - Analyzing Data

- Step 10 - Interpreting Results

- Step 11 - Writing Up Results

Step 1: Identifying and Developing a Topic

Whatever your field or discipline, the best advice to give on identifying a research topic is to choose something that you find really interesting. You will be spending an enormous amount of time with your topic, you need to be invested. Over the course of your research design, proposal and actually conducting your study, you may feel like you are really tired of your topic, however, your interest and investment in the topic will help you persist through dissertation defense. Identifying a research topic can be challenging. Most of the research that has been completed on the process of conducting research fails to examine the preliminary stages of the interactive and self-reflective process of identifying a research topic (Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). You may choose a topic at the beginning of the process, and through exploring the research that has already been done, one’s own interests that are narrowed or expanded in scope, the topic will change over time (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019). Where do I begin? According to the research, there are generally two paths to exploring your research topic, creative path and the rational path (Saunders et al., 2019). The rational path takes a linear path and deals with questions we need to ask ourselves like: what are some timely topics in my field in the media right now?; what strengths do I bring to the research?; what are the gaps in the research about the area of research interest? (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020).The creative path is less linear in that it may include keeping a notebook of ideas based on discussion in coursework or with your peers in the field. Whichever path you take, you will inevitably have to narrow your more generalized ideas down. A great way to do that is to continue reading the literature about and around your topic looking for gaps that could be explored. Also, try engaging in meaningful discussions with experts in your field to get their take on your research ideas (Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020). It is important to remember that a research topic should be (Dwarkadas & Lin, 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Wintersberger & Saunders, 2020):

- Interesting to you.

- Realistic in that it can be completed in an appropriate amount of time.

- Relevant to your program or field of study.

- Not widely researched.

Dwarkadas, S., & Lin, M. C. (2019, August 04). Finding a research topic. Computing Research Association for Women, Portland State University. https://cra.org/cra-wp/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2019/04/FindingResearchTopic/2019.pdf

Saunders, M. N. K., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2019). Research methods for business students (8th ed.). Pearson.

Wintersberger, D., & Saunders, M. (2020). Formulating and clarifying the research topic: Insights and a guide for the production management research community. Production, 30 . https://doi.org/10.1590/0103-6513.20200059

- Last Updated: Jun 29, 2023 1:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.kean.edu/ResearchProcessGuide

Selecting a Research Topic: Overview

- Refine your topic

- Background information & facts

- Writing help

Here are some resources to refer to when selecting a topic and preparing to write a paper:

- MIT Writing and Communication Center "Providing free professional advice about all types of writing and speaking to all members of the MIT community."

- Search Our Collections Find books about writing. Search by subject for: english language grammar; report writing handbooks; technical writing handbooks

- Blue Book of Grammar and Punctuation Online version of the book that provides examples and tips on grammar, punctuation, capitalization, and other writing rules.

- Select a topic

Choosing an interesting research topic is your first challenge. Here are some tips:

- Choose a topic that you are interested in! The research process is more relevant if you care about your topic.

- If your topic is too broad, you will find too much information and not be able to focus.

- Background reading can help you choose and limit the scope of your topic.

- Review the guidelines on topic selection outlined in your assignment. Ask your professor or TA for suggestions.

- Refer to lecture notes and required texts to refresh your knowledge of the course and assignment.

- Talk about research ideas with a friend. S/he may be able to help focus your topic by discussing issues that didn't occur to you at first.

- WHY did you choose the topic? What interests you about it? Do you have an opinion about the issues involved?

- WHO are the information providers on this topic? Who might publish information about it? Who is affected by the topic? Do you know of organizations or institutions affiliated with the topic?

- WHAT are the major questions for this topic? Is there a debate about the topic? Are there a range of issues and viewpoints to consider?

- WHERE is your topic important: at the local, national or international level? Are there specific places affected by the topic?

- WHEN is/was your topic important? Is it a current event or an historical issue? Do you want to compare your topic by time periods?

Table of contents

- Broaden your topic

- Information Navigator home

- Sources for facts - general

- Sources for facts - specific subjects

Start here for help

Ask Us Ask a question, make an appointment, give feedback, or visit us.

- Next: Refine your topic >>

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2021 2:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/select-topic

How To Choose A Research Topic

Step-By-Step Tutorial With Examples + Free Topic Evaluator

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Expert Reviewer: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | April 2024

Choosing the right research topic is likely the most important decision you’ll make on your dissertation or thesis journey. To make the right choice, you need to take a systematic approach and evaluate each of your candidate ideas across a consistent set of criteria. In this tutorial, we’ll unpack five essential criteria that will help you evaluate your prospective research ideas and choose a winner.

Overview: The “Big 5” Key Criteria

- Topic originality or novelty

- Value and significance

- Access to data and equipment

- Time limitations and implications

- Ethical requirements and constraints

Criterion #1: Originality & Novelty

As we’ve discussed extensively on this blog, originality in a research topic is essential. In other words, you need a clear research gap . The uniqueness of your topic determines its contribution to the field and its potential to stand out in the academic community. So, for each of your prospective topics, ask yourself the following questions:

- What research gap and research problem am I filling?

- Does my topic offer new insights?

- Am I combining existing ideas in a unique way?

- Am I taking a unique methodological approach?

To objectively evaluate the originality of each of your topic candidates, rate them on these aspects. This process will not only help in choosing a topic that stands out, but also one that can capture the interest of your audience and possibly contribute significantly to the field of study – which brings us to our next criterion.

Criterion #2: Value & Significance

Next, you’ll need to assess the value and significance of each prospective topic. To do this, you’ll need to ask some hard questions.

- Why is it important to explore these research questions?

- Who stands to benefit from this study?

- How will they benefit, specifically?

By clearly understanding and outlining the significance of each potential topic, you’ll not only be justifying your final choice – you’ll essentially be laying the groundwork for a persuasive research proposal , which is equally important.

Criterion #3: Access to Data & Equipment

Naturally, access to relevant data and equipment is crucial for the success of your research project. So, for each of your prospective topic ideas, you’ll need to evaluate whether you have the necessary resources to collect data and conduct your study.

Here are some questions to ask for each potential topic:

- Will I be able to access the sample of interest (e.g., people, animals, etc.)?

- Do I have (or can I get) access to the required equipment, at the time that I need it?

- Are there costs associated with any of this? If so, what are they?

Keep in mind that getting access to certain types of data may also require special permissions and legalities, especially if your topic involves vulnerable groups (patients, youths, etc.). You may also need to adhere to specific data protection laws, depending on the country. So, be sure to evaluate these aspects thoroughly for each topic. Overlooking any of these can lead to significant complications down the line.

Criterion #4: Time Requirements & Implications

Naturally, having a realistic timeline for each potential research idea is crucial. So, consider the scope of each potential topic and estimate how long each phase of the research will take — from literature review to data collection and analysis, to writing and revisions. Underestimating the time needed for a research project is extremely common , so it’s important to include buffer time for unforeseen delays.

Remember, efficient time management is not just about the duration but also about the timing . For example, if your research involves fieldwork, there may specific times of the year when this is most doable (or not doable at all). So, be sure to consider both time and timing for each of your prospective topics.

Criterion #5: Ethical Compliance

Failing to adhere to your university’s research ethics policy is a surefire way to get your proposal rejected . So, you’ll need to evaluate each topic for potential ethical issues, especially if your research involves human subjects, sensitive data, or has any potential environmental impact.

Remember that ethical compliance is not just a formality – it’s a responsibility to ensure the integrity and social responsibility of your research. Topics that pose significant ethical challenges are typically the first to be rejected, so you need to take this seriously. It’s also useful to keep in mind that some topics are more “ethically sensitive” than others , which usually means that they’ll require multiple levels of approval. Ideally, you want to avoid this additional admin, so mark down any prospective topics that fall into an ethical “grey zone”.

If you’re unsure about the details of your university’s ethics policy, ask for a copy or speak directly to your course coordinator. Don’t make any assumptions when it comes to research ethics!

Key Takeaways

In this post, we’ve explored how to choose a research topic using a systematic approach. To recap, the “Big 5” assessment criteria include:

- Topic originality and novelty

- Time requirements

- Ethical compliance

Be sure to grab a copy of our free research topic evaluator sheet here to fast-track your topic selection process. If you need hands-on help finding and refining a high-quality research topic for your dissertation or thesis, you can also check out our private coaching service .

Need a helping hand?

You Might Also Like:

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Writing and Rhetoric II

- Get Started

- News & Magazine Articles

- Scholarly Articles

- Books & Films

- Background Information

Choosing a Topic

Narrowing your topic, developing strong research questions, sample research questions.

- Types of Sources

- Evaluate Sources

- Social Media & News Literacy

- Copyright This link opens in a new window

- MLA Citations

A useful way to think about your project is to describe it in a three-step sentence that states your TOPIC + QUESTION + SIGNIFICANCE (or TQS):

Don’t worry if at first you can’t think of something to put as the significance in the third step. As you develop your answer, you’ll find ways to explain why your question is worth asking!

TQS sentence example:

I am working on the topic of the Apollo mission to the moon , because I want to find out why it was deemed so important in the 1960s , so that I can help my classmates understand the role of symbolic events in shaping national identity .

Note: The TQS formula is meant to prime your thinking. Use it to plan and test your question, but don’t expect to put it in your paper in exactly this form.

Adapted from Kate L. Turabian, Student’s Guide to Writing College Papers , 5th ed. (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019), pp. 14–15.

Start researching your topic more broadly to help you narrow your topic.

Think about:

- Which aspects am I most interested in?

- Is there a particular group of people to focus on?

- Is there a particular place to focus on?

- Is there a particular time period to focus on?

- What's the right scope for this particular research project? (For example, how much can I meaningfully address in this many pages?)

Background information can help with these questions before you dive in to more focused research.

- Research Guides Curated guides for a variety of topics and subject areas. Use them to find subject-specific resources.

Now use your narrowed topic to develop a research question!

Your research question should be:

- Focused on a single problem or issue

- Researchable using primary and/or secondary sources

- Feasible to answer within the timeframe and practical constraints

- Specific enough to answer thoroughly

- Complex enough to develop the answer over the space of a paper or thesis

- Relevant to your subject area and/or society more broadly

Adapted from Shona McCombes, "Developing strong research questions." Scribbr , March 2021.

Adapted from: George Mason University Writing Center. (2008). How to write a research question. Retrieved from http://writingcenter.gmu.edu/?p=307.

- << Previous: Background Information

- Next: Types of Sources >>

- Last Updated: Apr 23, 2024 4:12 PM

- URL: https://libguides.colum.edu/wrII

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

Importance of Narrowing the Research Topic

Whether you are assigned a general issue to investigate, must choose a problem to study from a list given to you by your professor, or you have to identify your own topic to investigate, it is important that the scope of the research problem is not too broad, otherwise, it will be difficult to adequately address the topic in the space and time allowed. You could experience a number of problems if your topic is too broad, including:

- You find too many information sources and, as a consequence, it is difficult to decide what to include or exclude or what are the most relevant sources.

- You find information that is too general and, as a consequence, it is difficult to develop a clear framework for examining the research problem.

- A lack of sufficient parameters that clearly define the research problem makes it difficult to identify and apply the proper methods needed to analyze it.

- You find information that covers a wide variety of concepts or ideas that can't be integrated into one paper and, as a consequence, you trail off into unnecessary tangents.

Lloyd-Walker, Beverly and Derek Walker. "Moving from Hunches to a Research Topic: Salient Literature and Research Methods." In Designs, Methods and Practices for Research of Project Management . Beverly Pasian, editor. ( Burlington, VT: Gower Publishing, 2015 ), pp. 119-129.

Strategies for Narrowing the Research Topic

A common challenge when beginning to write a research paper is determining how and in what ways to narrow down your topic . Even if your professor gives you a specific topic to study, it will almost never be so specific that you won’t have to narrow it down at least to some degree [besides, it is very boring to grade fifty papers that are all about the exact same thing!].

A topic is too broad to be manageable when a review of the literature reveals too many different, and oftentimes conflicting or only remotely related, ideas about how to investigate the research problem. Although you will want to start the writing process by considering a variety of different approaches to studying the research problem, you will need to narrow the focus of your investigation at some point early in the writing process. This way, you don't attempt to do too much in one paper.

Here are some strategies to help narrow the thematic focus of your paper :

- Aspect -- choose one lens through which to view the research problem, or look at just one facet of it [e.g., rather than studying the role of food in South Asian religious rituals, study the role of food in Hindu marriage ceremonies, or, the role of one particular type of food among several religions].

- Components -- determine if your initial variable or unit of analysis can be broken into smaller parts, which can then be analyzed more precisely [e.g., a study of tobacco use among adolescents can focus on just chewing tobacco rather than all forms of usage or, rather than adolescents in general, focus on female adolescents in a certain age range who choose to use tobacco].

- Methodology -- the way in which you gather information can reduce the domain of interpretive analysis needed to address the research problem [e.g., a single case study can be designed to generate data that does not require as extensive an explanation as using multiple cases].

- Place -- generally, the smaller the geographic unit of analysis, the more narrow the focus [e.g., rather than study trade relations issues in West Africa, study trade relations between Niger and Cameroon as a case study that helps to explain economic problems in the region].

- Relationship -- ask yourself how do two or more different perspectives or variables relate to one another. Designing a study around the relationships between specific variables can help constrict the scope of analysis [e.g., cause/effect, compare/contrast, contemporary/historical, group/individual, child/adult, opinion/reason, problem/solution].

- Time -- the shorter the time period of the study, the more narrow the focus [e.g., restricting the study of trade relations between Niger and Cameroon to only the period of 2010 - 2020].

- Type -- focus your topic in terms of a specific type or class of people, places, or phenomena [e.g., a study of developing safer traffic patterns near schools can focus on SUVs, or just student drivers, or just the timing of traffic signals in the area].

- Combination -- use two or more of the above strategies to focus your topic more narrowly.

NOTE : Apply one of the above strategies first in designing your study to determine if that gives you a manageable research problem to investigate. You will know if the problem is manageable by reviewing the literature on your more narrowed problem and assessing whether prior research is sufficient to move forward in your study [i.e., not too much, not too little]. Be careful, however, because combining multiple strategies risks creating the opposite problem--your problem becomes too narrowly defined and you can't locate enough research or data to support your study.

Booth, Wayne C. The Craft of Research . Fourth edition. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 2016; Coming Up With Your Topic. Institute for Writing Rhetoric. Dartmouth College; Narrowing a Topic. Writing Center. University of Kansas; Narrowing Topics. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Strategies for Narrowing a Topic. University Libraries. Information Skills Modules. Virginia Tech University; The Process of Writing a Research Paper. Department of History. Trent University; Ways to Narrow Down a Topic. Contributing Authors. Utah State OpenCourseWare.

- << Previous: Reading Research Effectively

- Next: Broadening a Topic Idea >>

- Last Updated: May 18, 2024 11:38 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

9.1 Developing a Research Question

Emilie Zickel

Think of a research paper as an opportunity to deepen (or create!) knowledge about a topic that matters to you. Just as Toni Morrison states that she is stimulated by what she doesn’t yet know, a research paper assignment can be interesting and meaningful if it allows you to explore what you don’t know.

Research, at its best, is an act of knowledge creation, not just an extended book report. This knowledge creation is the essence of any great educational experience. Instead of being lectured at, you get to design the learning project that will ultimately result in you experiencing and then expressing your own intellectual growth. You get to read what you choose, and you get to become an expert on your topic.

That sounds, perhaps, like a lofty goal. But by spending some quality time brainstorming, reading, thinking, or otherwise tuning into what matters to you, you can end up with a workable research topic that will lead you on an enjoyable research journey.

The best research topics are meaningful to you:

- Choose a topic that you want to understand better.

- Choose a topic that you want to read about and devote time to

- Choose a topic that is perhaps a bit out of your comfort zone

- Choose a topic that allows you to understand others’ opinions and how those opinions are shaped.

- Choose something that is relevant to you, personally or professionally.

- Do not choose a topic because you think it will be “easy”—those can end up being even quite challenging

The video below offers ideas on choosing not only a topic that you are drawn to, but a topic that is realistic and manageable for a college writing class.

“Choosing a Manageable Research Topic” by Pfaul Library is licensed under CC BY

Brainstorming Ideas for a Research Topic

Which question(s) below interest you? Which question(s) below spark a desire to respond? A good topic is one that moves you to think, to do, to want to know more, to want to say more.

There are many ways to come up with a good topic. The best thing to do is to give yourself time to think about what you really want to commit days and weeks to reading, thinking, researching, more reading, writing, more researching, reading, and writing on.

- What news stories do you often see, but want to know more about?

- What (socio-political) argument do you often have with others that you would love to work on strengthening?

- What would you love to become an expert on?

- What are you passionate about?

- What are you scared of?

- What problem in the world needs to be solved?

- What are the key controversies or current debates in the field of work that you want to go into?

- What is a problem that you see at work that needs to be better publicized or understood?

- What is the biggest issue facing [specific group of people: by age, by race, by gender, by ethnicity, by nationality, by geography, by economic standing? choose a group]

- If you could interview anyone in the world, who would it be? Can identifying that person lead you to a research topic that would be meaningful to you?

- What area/landmark/piece of history in your home community are you interested in?

- What in the world makes you angry?

- What global problem do you want to better understand?

- What local problem do you want to better understand?

- Is there some element of the career that you would like to have one day that you want to better understand?

- Consider researching the significance of a song, or an artist, or a musician, or a novel/film/short story/comic, or an art form on some aspect of the broader culture.

- Think about something that has happened to (or is happening to) a friend or family member. Do you want to know more about this?

- Go to a news source ( New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Christian Science Monitor, etc. ) and skim the titles of news stories. Does any story interest you?

From Topic to Research Question

Once you have decided on a research topic, an area for academic exploration that matters to you, it is time to start thinking about what you want to learn about that topic.

The goal of college-level research assignments is never going to be to simply “go find sources” on your topic. Instead, think of sources as helping you to answer a research question or a series of research questions about your topic. These should not be simple questions with simple answers, but rather complex questions about which there is no easy or obvious answer.

A compelling research question is one that may involve controversy, or may have a variety of answers, or may not have any single, clear answer. All of that is okay and even desirable. If the answer is an easy and obvious one, then there is little need for argument or research.

Make sure that your research question is clear, specific, researchable, and limited (but not too limited). Most of all, make sure that you are curious about your own research question. If it does not matter to you, researching it will feel incredibly boring and tedious.

The video below includes a deeper explanation of what a good research question is as well as examples of strong research questions:

“Creating a Good Research Question” by CII GSU

9.1 Developing a Research Question Copyright © 2022 by Emilie Zickel is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Saudi J Anaesth

- v.13(Suppl 1); 2019 Apr

Writing the title and abstract for a research paper: Being concise, precise, and meticulous is the key

Milind s. tullu.

Department of Pediatrics, Seth G.S. Medical College and KEM Hospital, Parel, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

This article deals with formulating a suitable title and an appropriate abstract for an original research paper. The “title” and the “abstract” are the “initial impressions” of a research article, and hence they need to be drafted correctly, accurately, carefully, and meticulously. Often both of these are drafted after the full manuscript is ready. Most readers read only the title and the abstract of a research paper and very few will go on to read the full paper. The title and the abstract are the most important parts of a research paper and should be pleasant to read. The “title” should be descriptive, direct, accurate, appropriate, interesting, concise, precise, unique, and should not be misleading. The “abstract” needs to be simple, specific, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, stand-alone, complete, scholarly, (preferably) structured, and should not be misrepresentative. The abstract should be consistent with the main text of the paper, especially after a revision is made to the paper and should include the key message prominently. It is very important to include the most important words and terms (the “keywords”) in the title and the abstract for appropriate indexing purpose and for retrieval from the search engines and scientific databases. Such keywords should be listed after the abstract. One must adhere to the instructions laid down by the target journal with regard to the style and number of words permitted for the title and the abstract.

Introduction

This article deals with drafting a suitable “title” and an appropriate “abstract” for an original research paper. Because the “title” and the “abstract” are the “initial impressions” or the “face” of a research article, they need to be drafted correctly, accurately, carefully, meticulously, and consume time and energy.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 ] Often, these are drafted after the complete manuscript draft is ready.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] Most readers will read only the title and the abstract of a published research paper, and very few “interested ones” (especially, if the paper is of use to them) will go on to read the full paper.[ 1 , 2 ] One must remember to adhere to the instructions laid down by the “target journal” (the journal for which the author is writing) regarding the style and number of words permitted for the title and the abstract.[ 2 , 4 , 5 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 12 ] Both the title and the abstract are the most important parts of a research paper – for editors (to decide whether to process the paper for further review), for reviewers (to get an initial impression of the paper), and for the readers (as these may be the only parts of the paper available freely and hence, read widely).[ 4 , 8 , 12 ] It may be worth for the novice author to browse through titles and abstracts of several prominent journals (and their target journal as well) to learn more about the wording and styles of the titles and abstracts, as well as the aims and scope of the particular journal.[ 5 , 7 , 9 , 13 ]

The details of the title are discussed under the subheadings of importance, types, drafting, and checklist.

Importance of the title

When a reader browses through the table of contents of a journal issue (hard copy or on website), the title is the “ first detail” or “face” of the paper that is read.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 13 ] Hence, it needs to be simple, direct, accurate, appropriate, specific, functional, interesting, attractive/appealing, concise/brief, precise/focused, unambiguous, memorable, captivating, informative (enough to encourage the reader to read further), unique, catchy, and it should not be misleading.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 12 ] It should have “just enough details” to arouse the interest and curiosity of the reader so that the reader then goes ahead with studying the abstract and then (if still interested) the full paper.[ 1 , 2 , 4 , 13 ] Journal websites, electronic databases, and search engines use the words in the title and abstract (the “keywords”) to retrieve a particular paper during a search; hence, the importance of these words in accessing the paper by the readers has been emphasized.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 , 14 ] Such important words (or keywords) should be arranged in appropriate order of importance as per the context of the paper and should be placed at the beginning of the title (rather than the later part of the title, as some search engines like Google may just display only the first six to seven words of the title).[ 3 , 5 , 12 ] Whimsical, amusing, or clever titles, though initially appealing, may be missed or misread by the busy reader and very short titles may miss the essential scientific words (the “keywords”) used by the indexing agencies to catch and categorize the paper.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 9 ] Also, amusing or hilarious titles may be taken less seriously by the readers and may be cited less often.[ 4 , 15 ] An excessively long or complicated title may put off the readers.[ 3 , 9 ] It may be a good idea to draft the title after the main body of the text and the abstract are drafted.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 ]

Types of titles

Titles can be descriptive, declarative, or interrogative. They can also be classified as nominal, compound, or full-sentence titles.

Descriptive or neutral title

This has the essential elements of the research theme, that is, the patients/subjects, design, interventions, comparisons/control, and outcome, but does not reveal the main result or the conclusion.[ 3 , 4 , 12 , 16 ] Such a title allows the reader to interpret the findings of the research paper in an impartial manner and with an open mind.[ 3 ] These titles also give complete information about the contents of the article, have several keywords (thus increasing the visibility of the article in search engines), and have increased chances of being read and (then) being cited as well.[ 4 ] Hence, such descriptive titles giving a glimpse of the paper are generally preferred.[ 4 , 16 ]

Declarative title

This title states the main finding of the study in the title itself; it reduces the curiosity of the reader, may point toward a bias on the part of the author, and hence is best avoided.[ 3 , 4 , 12 , 16 ]

Interrogative title

This is the one which has a query or the research question in the title.[ 3 , 4 , 16 ] Though a query in the title has the ability to sensationalize the topic, and has more downloads (but less citations), it can be distracting to the reader and is again best avoided for a research article (but can, at times, be used for a review article).[ 3 , 6 , 16 , 17 ]

From a sentence construct point of view, titles may be nominal (capturing only the main theme of the study), compound (with subtitles to provide additional relevant information such as context, design, location/country, temporal aspect, sample size, importance, and a provocative or a literary; for example, see the title of this review), or full-sentence titles (which are longer and indicate an added degree of certainty of the results).[ 4 , 6 , 9 , 16 ] Any of these constructs may be used depending on the type of article, the key message, and the author's preference or judgement.[ 4 ]

Drafting a suitable title

A stepwise process can be followed to draft the appropriate title. The author should describe the paper in about three sentences, avoiding the results and ensuring that these sentences contain important scientific words/keywords that describe the main contents and subject of the paper.[ 1 , 4 , 6 , 12 ] Then the author should join the sentences to form a single sentence, shorten the length (by removing redundant words or adjectives or phrases), and finally edit the title (thus drafted) to make it more accurate, concise (about 10–15 words), and precise.[ 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 9 ] Some journals require that the study design be included in the title, and this may be placed (using a colon) after the primary title.[ 2 , 3 , 4 , 14 ] The title should try to incorporate the Patients, Interventions, Comparisons and Outcome (PICO).[ 3 ] The place of the study may be included in the title (if absolutely necessary), that is, if the patient characteristics (such as study population, socioeconomic conditions, or cultural practices) are expected to vary as per the country (or the place of the study) and have a bearing on the possible outcomes.[ 3 , 6 ] Lengthy titles can be boring and appear unfocused, whereas very short titles may not be representative of the contents of the article; hence, optimum length is required to ensure that the title explains the main theme and content of the manuscript.[ 4 , 5 , 9 ] Abbreviations (except the standard or commonly interpreted ones such as HIV, AIDS, DNA, RNA, CDC, FDA, ECG, and EEG) or acronyms should be avoided in the title, as a reader not familiar with them may skip such an article and nonstandard abbreviations may create problems in indexing the article.[ 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 9 , 12 ] Also, too much of technical jargon or chemical formulas in the title may confuse the readers and the article may be skipped by them.[ 4 , 9 ] Numerical values of various parameters (stating study period or sample size) should also be avoided in the titles (unless deemed extremely essential).[ 4 ] It may be worthwhile to take an opinion from a impartial colleague before finalizing the title.[ 4 , 5 , 6 ] Thus, multiple factors (which are, at times, a bit conflicting or contrasting) need to be considered while formulating a title, and hence this should not be done in a hurry.[ 4 , 6 ] Many journals ask the authors to draft a “short title” or “running head” or “running title” for printing in the header or footer of the printed paper.[ 3 , 12 ] This is an abridged version of the main title of up to 40–50 characters, may have standard abbreviations, and helps the reader to navigate through the paper.[ 3 , 12 , 14 ]

Checklist for a good title

Table 1 gives a checklist/useful tips for drafting a good title for a research paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 12 ] Table 2 presents some of the titles used by the author of this article in his earlier research papers, and the appropriateness of the titles has been commented upon. As an individual exercise, the reader may try to improvise upon the titles (further) after reading the corresponding abstract and full paper.

Checklist/useful tips for drafting a good title for a research paper

Some titles used by author of this article in his earlier publications and remark/comment on their appropriateness

The Abstract

The details of the abstract are discussed under the subheadings of importance, types, drafting, and checklist.

Importance of the abstract

The abstract is a summary or synopsis of the full research paper and also needs to have similar characteristics like the title. It needs to be simple, direct, specific, functional, clear, unbiased, honest, concise, precise, self-sufficient, complete, comprehensive, scholarly, balanced, and should not be misleading.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 17 ] Writing an abstract is to extract and summarize (AB – absolutely, STR – straightforward, ACT – actual data presentation and interpretation).[ 17 ] The title and abstracts are the only sections of the research paper that are often freely available to the readers on the journal websites, search engines, and in many abstracting agencies/databases, whereas the full paper may attract a payment per view or a fee for downloading the pdf copy.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 14 ] The abstract is an independent and stand-alone (that is, well understood without reading the full paper) section of the manuscript and is used by the editor to decide the fate of the article and to choose appropriate reviewers.[ 2 , 7 , 10 , 12 , 13 ] Even the reviewers are initially supplied only with the title and the abstract before they agree to review the full manuscript.[ 7 , 13 ] This is the second most commonly read part of the manuscript, and therefore it should reflect the contents of the main text of the paper accurately and thus act as a “real trailer” of the full article.[ 2 , 7 , 11 ] The readers will go through the full paper only if they find the abstract interesting and relevant to their practice; else they may skip the paper if the abstract is unimpressive.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] The abstract needs to highlight the selling point of the manuscript and succeed in luring the reader to read the complete paper.[ 3 , 7 ] The title and the abstract should be constructed using keywords (key terms/important words) from all the sections of the main text.[ 12 ] Abstracts are also used for submitting research papers to a conference for consideration for presentation (as oral paper or poster).[ 9 , 13 , 17 ] Grammatical and typographic errors reflect poorly on the quality of the abstract, may indicate carelessness/casual attitude on part of the author, and hence should be avoided at all times.[ 9 ]

Types of abstracts

The abstracts can be structured or unstructured. They can also be classified as descriptive or informative abstracts.

Structured and unstructured abstracts

Structured abstracts are followed by most journals, are more informative, and include specific subheadings/subsections under which the abstract needs to be composed.[ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 , 17 , 18 ] These subheadings usually include context/background, objectives, design, setting, participants, interventions, main outcome measures, results, and conclusions.[ 1 ] Some journals stick to the standard IMRAD format for the structure of the abstracts, and the subheadings would include Introduction/Background, Methods, Results, And (instead of Discussion) the Conclusion/s.[ 1 , 2 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 17 , 18 ] Structured abstracts are more elaborate, informative, easy to read, recall, and peer-review, and hence are preferred; however, they consume more space and can have same limitations as an unstructured abstract.[ 7 , 9 , 18 ] The structured abstracts are (possibly) better understood by the reviewers and readers. Anyway, the choice of the type of the abstract and the subheadings of a structured abstract depend on the particular journal style and is not left to the author's wish.[ 7 , 10 , 12 ] Separate subheadings may be necessary for reporting meta-analysis, educational research, quality improvement work, review, or case study.[ 1 ] Clinical trial abstracts need to include the essential items mentioned in the CONSORT (Consolidated Standards Of Reporting Trials) guidelines.[ 7 , 9 , 14 , 19 ] Similar guidelines exist for various other types of studies, including observational studies and for studies of diagnostic accuracy.[ 20 , 21 ] A useful resource for the above guidelines is available at www.equator-network.org (Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of health Research). Unstructured (or non-structured) abstracts are free-flowing, do not have predefined subheadings, and are commonly used for papers that (usually) do not describe original research.[ 1 , 7 , 9 , 10 ]

The four-point structured abstract: This has the following elements which need to be properly balanced with regard to the content/matter under each subheading:[ 9 ]

Background and/or Objectives: This states why the work was undertaken and is usually written in just a couple of sentences.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 ] The hypothesis/study question and the major objectives are also stated under this subheading.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 ]

Methods: This subsection is the longest, states what was done, and gives essential details of the study design, setting, participants, blinding, sample size, sampling method, intervention/s, duration and follow-up, research instruments, main outcome measures, parameters evaluated, and how the outcomes were assessed or analyzed.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

Results/Observations/Findings: This subheading states what was found, is longer, is difficult to draft, and needs to mention important details including the number of study participants, results of analysis (of primary and secondary objectives), and include actual data (numbers, mean, median, standard deviation, “P” values, 95% confidence intervals, effect sizes, relative risks, odds ratio, etc.).[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

Conclusions: The take-home message (the “so what” of the paper) and other significant/important findings should be stated here, considering the interpretation of the research question/hypothesis and results put together (without overinterpreting the findings) and may also include the author's views on the implications of the study.[ 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 ]

The eight-point structured abstract: This has the following eight subheadings – Objectives, Study Design, Study Setting, Participants/Patients, Methods/Intervention, Outcome Measures, Results, and Conclusions.[ 3 , 9 , 18 ] The instructions to authors given by the particular journal state whether they use the four- or eight-point abstract or variants thereof.[ 3 , 14 ]

Descriptive and Informative abstracts

Descriptive abstracts are short (75–150 words), only portray what the paper contains without providing any more details; the reader has to read the full paper to know about its contents and are rarely used for original research papers.[ 7 , 10 ] These are used for case reports, reviews, opinions, and so on.[ 7 , 10 ] Informative abstracts (which may be structured or unstructured as described above) give a complete detailed summary of the article contents and truly reflect the actual research done.[ 7 , 10 ]

Drafting a suitable abstract

It is important to religiously stick to the instructions to authors (format, word limit, font size/style, and subheadings) provided by the journal for which the abstract and the paper are being written.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] Most journals allow 200–300 words for formulating the abstract and it is wise to restrict oneself to this word limit.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 22 ] Though some authors prefer to draft the abstract initially, followed by the main text of the paper, it is recommended to draft the abstract in the end to maintain accuracy and conformity with the main text of the paper (thus maintaining an easy linkage/alignment with title, on one hand, and the introduction section of the main text, on the other hand).[ 2 , 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 ] The authors should check the subheadings (of the structured abstract) permitted by the target journal, use phrases rather than sentences to draft the content of the abstract, and avoid passive voice.[ 1 , 7 , 9 , 12 ] Next, the authors need to get rid of redundant words and edit the abstract (extensively) to the correct word count permitted (every word in the abstract “counts”!).[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 13 ] It is important to ensure that the key message, focus, and novelty of the paper are not compromised; the rationale of the study and the basis of the conclusions are clear; and that the abstract is consistent with the main text of the paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 9 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 ] This is especially important while submitting a revision of the paper (modified after addressing the reviewer's comments), as the changes made in the main (revised) text of the paper need to be reflected in the (revised) abstract as well.[ 2 , 10 , 12 , 14 , 22 ] Abbreviations should be avoided in an abstract, unless they are conventionally accepted or standard; references, tables, or figures should not be cited in the abstract.[ 7 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 13 ] It may be worthwhile not to rush with the abstract and to get an opinion by an impartial colleague on the content of the abstract; and if possible, the full paper (an “informal” peer-review).[ 1 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 11 , 17 ] Appropriate “Keywords” (three to ten words or phrases) should follow the abstract and should be preferably chosen from the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) list of the U.S. National Library of Medicine ( https://meshb.nlm.nih.gov/search ) and are used for indexing purposes.[ 2 , 3 , 11 , 12 ] These keywords need to be different from the words in the main title (the title words are automatically used for indexing the article) and can be variants of the terms/phrases used in the title, or words from the abstract and the main text.[ 3 , 12 ] The ICMJE (International Committee of Medical Journal Editors; http://www.icmje.org/ ) also recommends publishing the clinical trial registration number at the end of the abstract.[ 7 , 14 ]

Checklist for a good abstract

Table 3 gives a checklist/useful tips for formulating a good abstract for a research paper.[ 1 , 2 , 3 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 , 17 , 22 ]

Checklist/useful tips for formulating a good abstract for a research paper

Concluding Remarks

This review article has given a detailed account of the importance and types of titles and abstracts. It has also attempted to give useful hints for drafting an appropriate title and a complete abstract for a research paper. It is hoped that this review will help the authors in their career in medical writing.

Financial support and sponsorship

Conflicts of interest.

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgement

The author thanks Dr. Hemant Deshmukh - Dean, Seth G.S. Medical College & KEM Hospital, for granting permission to publish this manuscript.

Let’s start a new project together

Why you should avoid ambiguous questions in research, written by: paul stallard.

When carrying out any form of market research it is key to avoid ambiguous questions as you may receive vague answers. You only get out what you put in, and if you include poorly planned, ambiguous or misleading questions within your survey, then your results will come out exactly the same way.

Whilst it is important not to include leading questions that push an audience towards feeling a certain way, you should always make sure that your questions are straight to the point and that the respondents can easily decipher what a question means, and they can provide a confident answer. If this is not the case, you will not only receive questionable results, but you may also not get the best representation of the sector you are exploring.

Whether your research is commercial , political or cultural, our full-service market research team can provide you with an accurate picture of what the world thinks, and bring your story to life with more than just opinions . By better understanding buyers, trends, and data, it is possible to build stronger brands and drive sales. But you need to ask the right questions.

The ability to drill into profiled target groups and gather insights will give you strong reliable research to help position you as a thought leader.

...you should always make sure that your questions are straight to the point and that the respondents can easily decipher what a question means

More in: Work

More in: blog.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

‘The scientist is not in the business of following instructions.’

Glimpse of next-generation internet

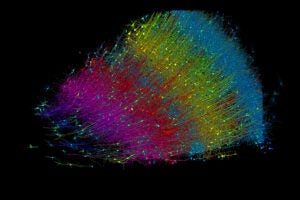

Epic science inside a cubic millimeter of brain

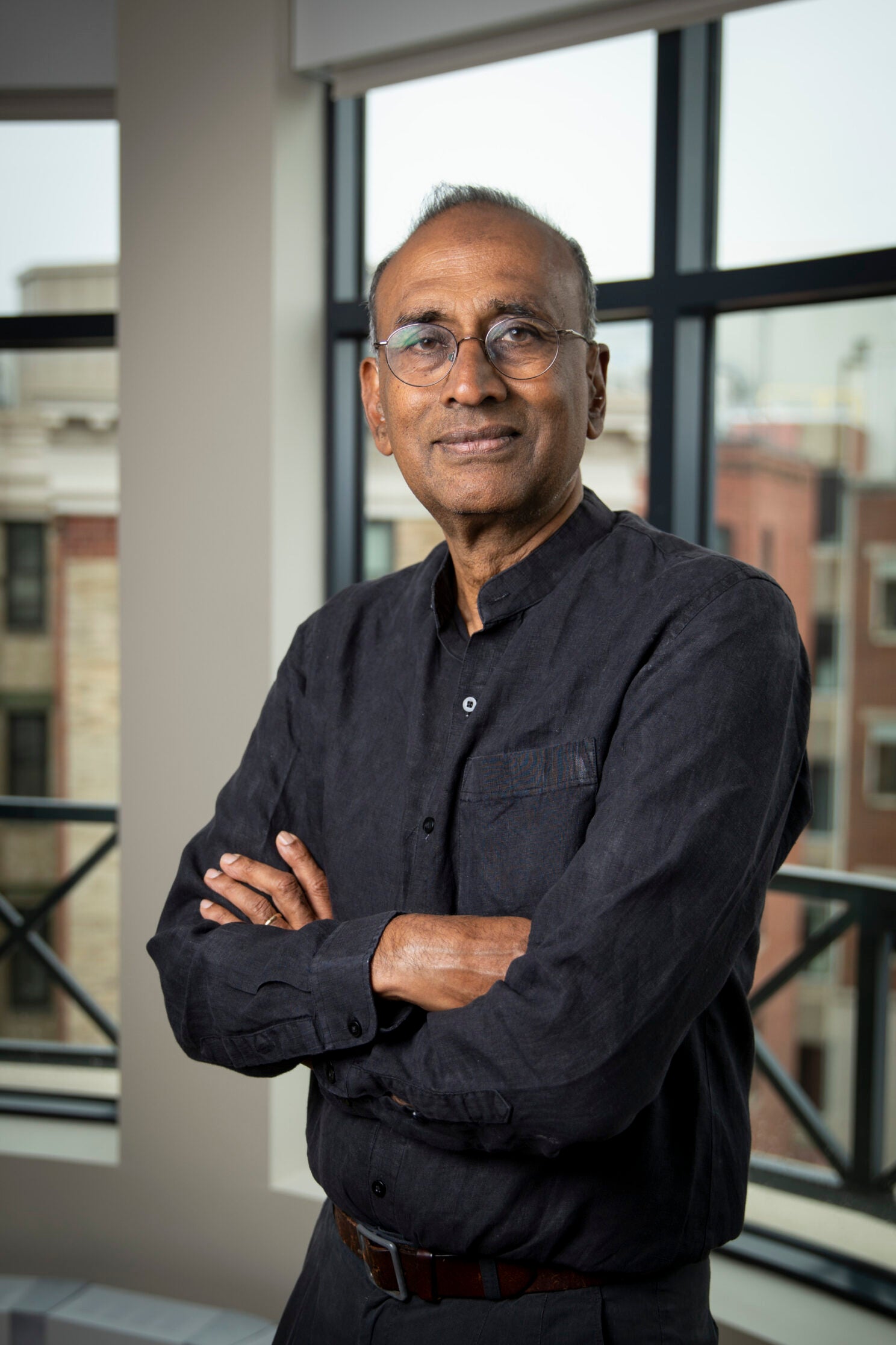

Venki Ramakrishnan.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

Science is making anti-aging progress. But do we want to live forever?

Nobel laureate details new book, which surveys research, touches on larger philosophical questions

Anne J. Manning

Harvard Staff Writer

Mayflies live for only a day. Galapagos tortoises can reach up to age 170. The Greenland shark holds the world record at over 400 years of life.

Venki Ramakrishnan, Nobel laureate and author of the newly released “ Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for Immortality ,” opened his packed Harvard Science Book Talk last week by noting the vast variabilities of lifespans across the natural world. Death is certain, so far as we know. But there’s no physical or chemical law that says it must happen at a fixed time, which raises other, more philosophical issues.

The “why” behind these enormous swings, and the quest to harness longevity for humans, have driven fevered attempts (and billions of dollars in research spending) to slow or stop aging. Ramakrishnan’s book is a dispassionate journey through current scientific understanding of aging and death, which basically comes down to an accumulation of chemical damage to molecules and cells.

“The question is whether we can tackle aging processes, while still keeping us who we are as humans,” said Ramakrishnan during his conversation with Antonio Regalado, a writer for the MIT Technology Review. “And whether we can do that in a safe and effective way.”

Even if immortality — or just living for a very, very long time — were theoretically possible through science, should we pursue it? Ramakrishnan likened the question to other moral ponderings.

“There’s no physical or chemical law that says we can’t colonize other galaxies, or outer space, or even Mars,” he said. “I would put it in that same category. And it would require huge breakthroughs, which we haven’t made yet.”

In fact, we’re a lot closer to big breakthroughs when it comes to chasing immortality. Ramakrishnan noted the field is moving so fast that a book like his can capture but a snippet. He then took the audience on a brief tour of some of the major directions of aging research. And much of it, he said, started in unexpected places.

Take rapamycin, a drug first isolated in the 1960s from a bacterium on Easter Island found to have antifungal, immunosuppressant, and anticancer properties. Rapamycin targets the TOR pathway, a large molecular signaling cascade within cells that regulates many functions fundamental to life. Rapamycin has garnered renewed attention for its potential to reverse the aging process by targeting cellular signaling associated with physiological changes and diseases in older adults.

Other directions include mimicking the anti-aging effects of caloric restriction shown in mice, as well as one particularly exciting area called cellular reprogramming. That means taking fully developed cells and essentially turning back the clock on their development.

The most famous foundational experiment in this area was by Kyoto University scientist and Nobel laureate Shinya Yamanaka, who showed that just four transcription factors could revert an adult cell all the way back to a pluripotent stem cell, creating what are now known as induced pluripotent stem cells.

Ramakrishnan , a scientist at England’s MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, won the 2009 Nobel Prize in chemistry for uncovering the structure of the ribosome. He said he felt qualified to write the book because he has “no skin in the game” of aging research. As a molecular biologist who has studied fundamental processes of how cells make proteins, he had connections in the field but wasn’t too close to any of it.

While researching the book, he took pains to avoid interviewing scientists with commercial ventures tied to aging.

The potential for conflicts of interest abound.

The world has seen an explosion in aging research in recent decades, with billions of dollars spent by government agencies and private companies . And the consumer market for products is forecast to hit $93 billion by 2027 .

As a result, false or exaggerated claims by companies promising longer life are currently on the rise, Ramakrishnan noted. He shared one example: Supplements designed to lengthen a person’s telomeres, or genetic segments that shrink with age, are available on Amazon.

“Of course, these are not FDA approved. There are no clinical trials, and it’s not clear what their basis is,” he said.

But still there appears to be some demand.

Get the best of the Gazette delivered to your inbox

By subscribing to this newsletter you’re agreeing to our privacy policy

Share this article

You might like.

George Whitesides became a giant of chemistry by keeping it simple

Physicists demo first metro-area quantum computer network in Boston

Researchers publish largest-ever dataset of neural connections

Finding right mix on campus speech policies

Legal, political scholars discuss balancing personal safety, constitutional rights, academic freedom amid roiling protests, cultural shifts

Good genes are nice, but joy is better

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Some Ambiguities in the Study of Ambiguity

Cite this chapter.

- Robert R. Hoffman

Part of the book series: Cognitive Science ((COGNITIVE SCIEN))

93 Accesses

1 Citations

Researchers agree that there are different kinds of ambiguity and that ambiguity occurs at a number of levels of language. Everyone agrees that the different kinds and levels can be defined and researched. However, a number of terms are relied upon heavily in explanations of ambiguity — lexicon, retrieval, search, activation, access, inhibition, interference , and representation — and researchers have major disagreements about the meanings of these explanatory terms. It may seem curious that the various technical terms that are used in the scientific analysis of lexical ambiguity are themselves ambiguous in meaning. For instance, what is the “conceptual meaning” of a word? One would be hard-pressed to find any two cognitive psychologists who would fully agree in their answers to this question. Not only are the meanings of the scientific terms left open, but the terms themselves are usually (and rather obviously) reliant on underlying metaphorical concepts. Examples would be the “suppression” of meanings or the “interference” of mental processes.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Unable to display preview. Download preview PDF.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Adelphi University, Garden City, NY, 11530, USA

David S. Gorfein

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 1989 Springer-Verlag New York Inc.

About this chapter

Hoffman, R.R. (1989). Some Ambiguities in the Study of Ambiguity. In: Gorfein, D.S. (eds) Resolving Semantic Ambiguity. Cognitive Science. Springer, New York, NY. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3596-5_11

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-3596-5_11

Publisher Name : Springer, New York, NY

Print ISBN : 978-0-387-96906-0

Online ISBN : 978-1-4612-3596-5

eBook Packages : Springer Book Archive

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

share this!

May 15, 2024

This article has been reviewed according to Science X's editorial process and policies . Editors have highlighted the following attributes while ensuring the content's credibility:

fact-checked

trusted source

Democratic nations should rely on international law to tackle growing 'hybrid' and 'gray zone' security threats

by University of Exeter

Democratic countries should rely on international law and improve their legal resilience to tackle the grave security threats caused by worsening relations between great powers, new research shows.

The growth of hybrid threats and gray zone warfare, two forms of geopolitical competition that fall below the threshold of armed conflict, is one of the great strategic challenges facing liberal democracies today.

Hostile powers routinely employ tactics such as diplomatic pressure, economic espionage, military exercises, cyber operations, disinformation, exploiting social and political divisions, and fostering financial and other dependencies to exploit the vulnerabilities of democratic societies.

In an environment where anything can be weaponized and everything has turned into some form of "warfare," a clear line between war and peace is increasingly difficult to draw.

International law itself has become a tool that strategic rivals use to compete with each other. There are concerns legal processes are not sufficiently robust to contain geopolitical competition within acceptable boundaries and to mitigate its adverse effects.

The ambiguous nature of hybrid and gray zone activities puts considerable strain on core principles of international law, such as the principle of non-intervention. By operating at the dividing line between war and peace, and between lawful and unlawful competition, strategic competitors employing hybrid and gray zone tactics seek to exploit legal uncertainty to their own advantage.

Many rules and principles of international law were developed in the pre-digital era and there is disagreement about how they apply in novel domains, such as cyberspace. This creates opportunities for hostile actors to take advantage of legal gaps and to promote legal developments that undermine liberal values.

In a new book, "Hybrid Threats and Gray Zone Conflict: The Challenge to Liberal Democracies," experts drawn from several disciplines assess the legal and ethical challenges that hybrid threats and gray zone conflict pose for liberal democracies. They argue that states must bolster their legal resilience to prepare their legal systems to cope with these challenges. Democratic nations also need to address basic ethical concerns to ensure that their response to hybrid threats and gray zone conflict does not detract from their own values.

Topics covered in the book include hybrid threats in the maritime domain, China's evolving strategy in the Arctic, the dangers of the absence of agreed standards for assessing military gray zone operations, the legal steps Finland has taken to prepare for threats and the path to legal resilience taken by the Office of Legal Affairs at NATO's Allied Command Operations.

The book is co-edited by Professor Mitt Regan, from Georgetown University, and Professor Aurel Sari, from the University of Exeter. It is published by Oxford University Press under the auspices of the Center for Ethics and the Rule of Law (CERL) at the University of Pennsylvania.

Professor Sari said, "This book brings together an outstanding cast of authors from academia, legal practice and beyond who have done an amazing job of addressing what is a complex and at times controversial subject.

"Although many of these legal, policy and ethical dilemmas have been addressed before, the aim of this volume is to do so systematically and in greater depth so as to contribute to a better understanding of the field and to efforts to develop more effective responses to counter the adverse effects of hybrid and gray zone conflict on liberal democracies and on the international rule of law."

A total of 39 experts contributed to the 28-chapter volume, which considers the strengths and shortcomings of the existing rules and institutions of international law in responding to hybrid threats and gray zone conflicts and how liberal democracies should respond to the challenges posed by hybrid and gray zone competition in a way that does not undermine the very values they seek to uphold.

Provided by University of Exeter

Explore further

Feedback to editors

Blue Origin flies thrill seekers to space, including oldest astronaut

4 hours ago

Composition of gut microbiota could influence decision-making

May 18, 2024

Researchers realize multiphoton electron emission with non-classical light

Saturday Citations: Mediterranean diet racks up more points; persistent quantum coherence; vegan dogs

Physicists propose path to faster, more flexible robots

Scientists develop new geochemical 'fingerprint' to trace contaminants in fertilizer

May 17, 2024

Study reveals how a sugar-sensing protein acts as a 'machine' to switch plant growth—and oil production—on and off

Researchers develop world's smallest quantum light detector on a silicon chip

How heat waves are affecting Arctic phytoplankton

Horse remains show Pagan-Christian trade networks supplied horses from overseas for the last horse sacrifices in Europe

Relevant physicsforums posts, cover songs versus the original track, which ones are better.

10 hours ago

Today's Fusion Music: T Square, Cassiopeia, Rei & Kanade Sato

Bach, bach, and more bach please.

23 hours ago

What are your favorite Disco "Classics"?

Who is your favorite jazz musician and what is your favorite song, for ww2 buffs.

More from Art, Music, History, and Linguistics

Related Stories

Accountability standards based on rules of democracy needed in times of rising political violence, scholar argues

May 6, 2024

Taiwan is experiencing millions of cyberattacks every day—the world should be paying attention

May 4, 2024

A framework for analyzing US–China geopolitical tensions in Indo-Pacific

Nov 11, 2022

Rise of drones necessitates revision of laws of war

Mar 19, 2019

Wolf connected to livestock killings could be breeding, wildlife officials say

Apr 26, 2024

Wildlife officials aim to keep Colorado's wolves from meeting the endangered Mexican wolf

Feb 5, 2024

Recommended for you

The power of ambiguity: Using computer models to understand the debate about climate change

May 13, 2024

Study finds avoiding social media before an election has little to no effect on people's political views

Study shows AI conversational agents can help reduce interethnic prejudice during online interactions

May 10, 2024

Study finds liberals and conservatives differ on climate change beliefs—but are relatively united in taking action

May 9, 2024

Analysis of millions of posts shows that users seek out echo chambers on social media

The spread of misinformation varies by topic and by country in Europe, study finds

May 8, 2024

Let us know if there is a problem with our content

Use this form if you have come across a typo, inaccuracy or would like to send an edit request for the content on this page. For general inquiries, please use our contact form . For general feedback, use the public comments section below (please adhere to guidelines ).

Please select the most appropriate category to facilitate processing of your request

Thank you for taking time to provide your feedback to the editors.

Your feedback is important to us. However, we do not guarantee individual replies due to the high volume of messages.

E-mail the story

Your email address is used only to let the recipient know who sent the email. Neither your address nor the recipient's address will be used for any other purpose. The information you enter will appear in your e-mail message and is not retained by Phys.org in any form.

Newsletter sign up

Get weekly and/or daily updates delivered to your inbox. You can unsubscribe at any time and we'll never share your details to third parties.

More information Privacy policy

Donate and enjoy an ad-free experience

We keep our content available to everyone. Consider supporting Science X's mission by getting a premium account.

E-mail newsletter

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in Europe

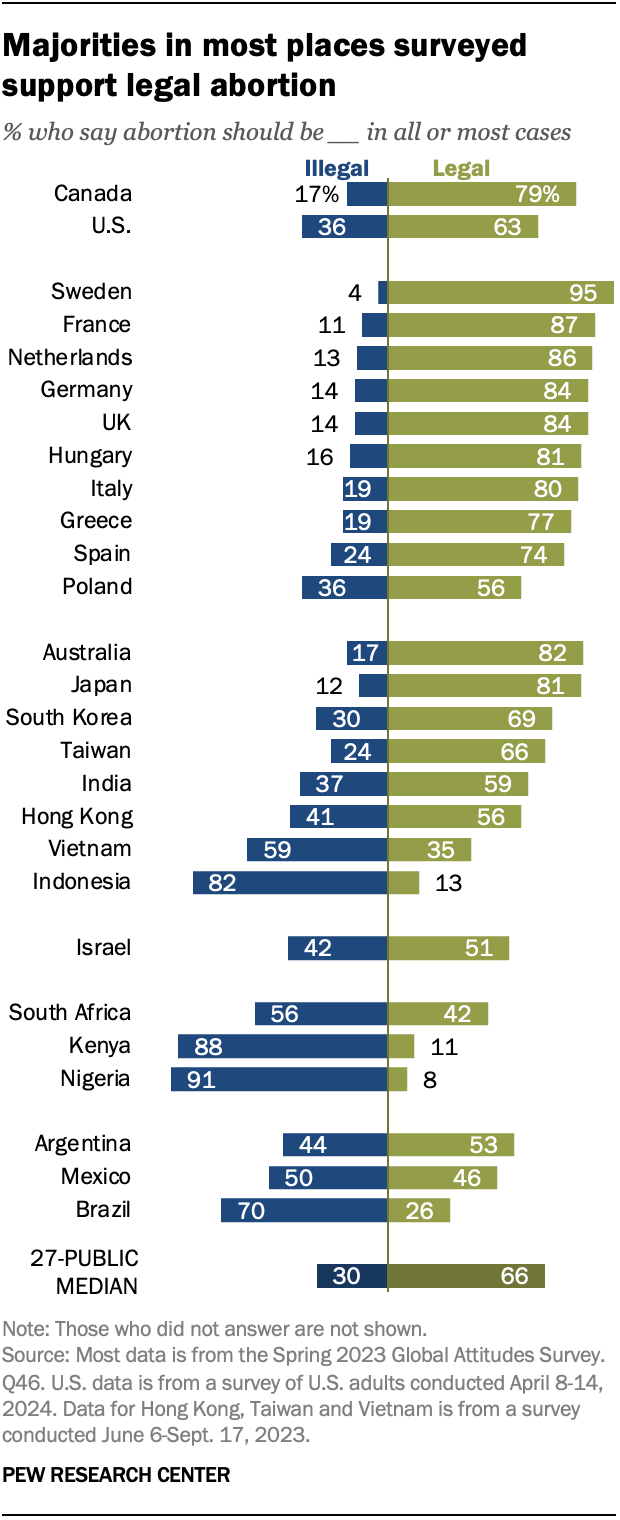

Majorities in most of the 27 places around the world that Pew Research Center surveyed in 2023 and 2024 say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. But attitudes differ widely – even within places. Religiously unaffiliated adults, people on the ideological left and women are more likely to support legal abortion in many places.

This analysis focuses on public opinion of abortion in 27 places in North America, Europe, the Middle East, the Asia-Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America.

This analysis draws on nationally representative surveys of 27,285 adults conducted from Feb. 20 to May 22, 2023. All surveys were conducted over the phone with adults in Canada, France, Germany, Greece, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, South Korea, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom. Surveys were conducted face-to-face in Argentina, Brazil, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Israel, Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria, Poland and South Africa. In Australia, we used a mixed-mode probability-based online panel.

Data from Hong Kong, Taiwan and Vietnam comes from a survey of 6,544 adults conducted from June 6 to Sept. 17, 2023. All interviews in Hong Kong and Taiwan were conducted over the phone; those in Vietnam were conducted face-to-face.

In the United States, data comes from a survey of 8,709 U.S. adults conducted from April 8 to 14, 2024. Everyone who took part in this survey is a member of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

Here are the questions used for this analysis , along with responses, and the survey methodology .

A median of 66% of adults across the 27 places surveyed believe abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while a median of 30% believe it should be illegal in all or most cases.

In the United States, where a Supreme Court decision ended the constitutional right to abortion in 2022, 63% of adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. U.S. support for legal abortion has not changed in recent years.

In Europe, there is widespread agreement that abortion should be legal. In nearly every European country surveyed, at least 75% of adults hold this view, including roughly 25% or more who say it should be legal in all cases.

Swedes are especially supportive: 95% say it should be legal, including 66% who say it should be legal in all cases.

Poland stands out among the European countries surveyed for its residents’ more restrictive views, at least compared with other Europeans. Over half of Poles (56%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, but 36% say it should be illegal in all or most cases.

Attitudes are more varied in the Asia-Pacific region. Majorities say abortion should be legal in all or most cases in Australia, Hong Kong, India, Japan, South Korea and Taiwan. But in Vietnam, a majority (59%) say it should be illegal in all or most cases, and 82% in Indonesia share this view.

In Israel, 51% of adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 42% say it should be illegal in all or most cases.

In all three African countries surveyed – Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa – majorities say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases. That includes 88% of adults in Kenya and 91% in Nigeria.

In South America, views about legal abortion are divided in Argentina and Mexico. But in Brazil, seven-in-ten adults say abortion should be illegal in all or most cases.

Abortion legislation and views of abortion

Abortion rules tend to be more restrictive in places where support for legal abortion is lower. Abortions in Brazil, Indonesia and Nigeria are only permitted when a woman’s life is at risk, according to the Center for Reproductive Rights . In Israel, Kenya and Poland, abortion is permitted to preserve a woman’s health. Most other places surveyed have more permissive regulations that allow abortions up to a specific point during the pregnancy.

Compared with Pew Research Center surveys over the past decade in Europe , India and Latin America , more people in many countries now say that abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

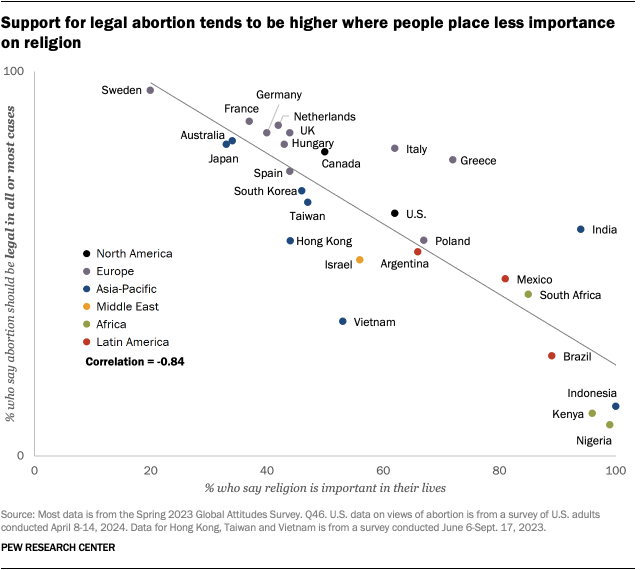

Importance of religion and attitudes toward abortion

Attitudes toward abortion are strongly tied to how important people say religion is in their lives. In places where a greater share of people say religion is at least somewhat important to them, much smaller shares think abortion should be legal.

For example, 99% of Nigerians say religion is important in their lives and only 8% say abortion should be legal in all or most cases. On the opposite end of the spectrum, 20% of Swedes see religion as important and 95% support legal abortion.

People in India are outliers: 94% view religion as important, but 59% also favor legal abortion.

How religious affiliation, GDP relate to abortion views

Economic development plays a role in this relationship, too. In places with lower gross domestic product (GDP) per capita , people tend to be more religious and have more restrictive attitudes about abortion.

But the U.S. stands apart in this regard: Among the advanced economies surveyed, Americans have the highest per capita GDP but are among the most likely to say religion is important to them. They are also among the least likely to say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

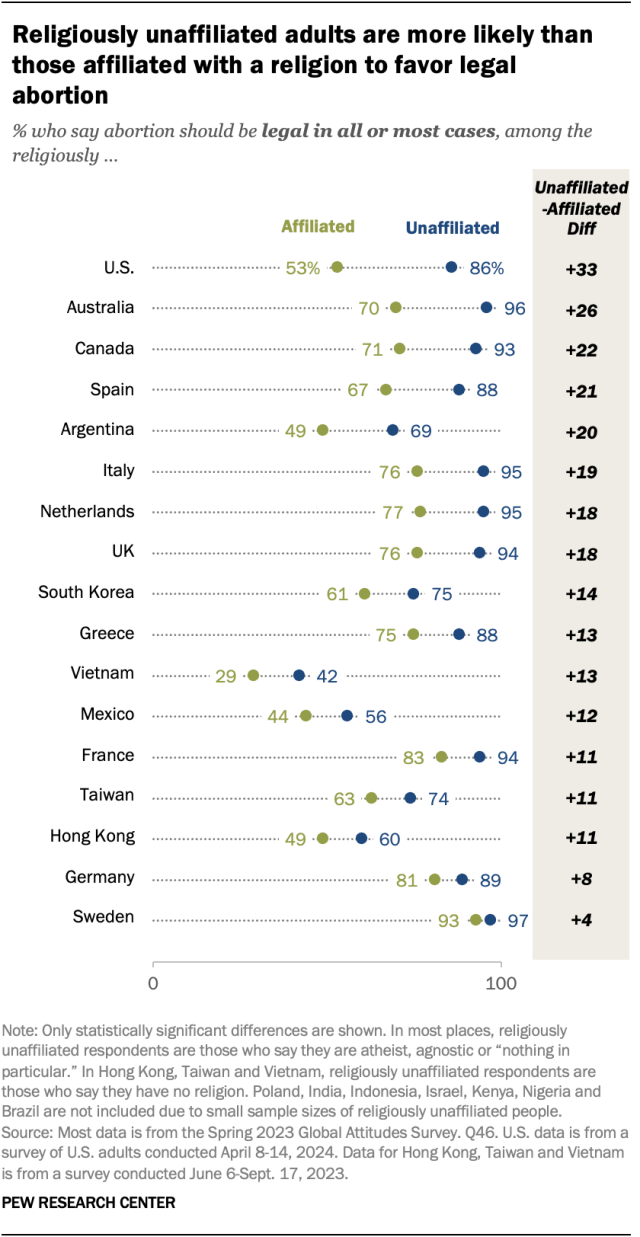

Religious affiliation is also an important factor when considering views of abortion in particular places.

On balance, adults who are religiously unaffiliated – self-identifying as atheist, agnostic or “nothing in particular” – are more likely to say abortion should be legal in all or most cases than are those who identify with a religion.

This difference is largest in the U.S., where 86% of religiously unaffiliated adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, compared with 53% of religiously affiliated Americans. Of course, differences also exist among religiously affiliated Americans. White evangelical Protestants are the least likely to favor legal abortion.

In countries where there are two dominant religions and negligible shares of religiously unaffiliated adults, there are often divides between the dominant religions.

Take Israel, for example, where 99% of adults affiliate with a religion. While 56% of Jewish adults say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, 23% of Muslims agree. And 89% of Jews who describe themselves as Hiloni (“secular”) favor legal abortion, compared with only 12% of Haredi (“ultra-orthodox”) or Dati (“religious”) Jews. Masorti (“traditional”) Jews fall in between, with 58% favoring legal abortion.

Views differ by religion in Nigeria, too, even as the vast majority of Nigerians oppose legal abortion. One-in-ten Nigerian Christians support legal abortion in all or most cases, compared with just 3% of Nigerian Muslims.

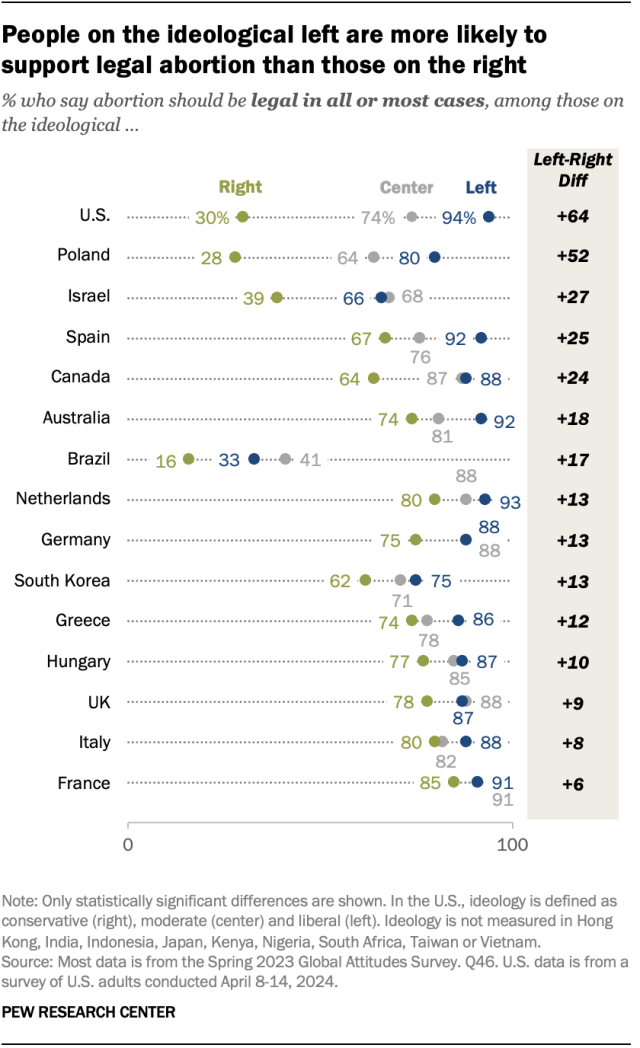

Differences in views by political ideology

In 15 of the 18 countries where the Center measures political ideology on a left-right scale, those on the left are more likely than those on the right to say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

Again, Americans are the most divided in their views: 94% of liberals support legal abortion, compared with 30% of conservatives.

Opinions by gender

Gender also plays a role in views of abortion, though these differences are not as large or widespread as ideological and religious differences.

In seven countries surveyed – Australia, Israel, Japan, South Korea, Sweden, the UK and the U.S. – women are significantly more likely than men to say abortion should be legal in all or most cases.

In an additional six countries in Europe and North America, women are more likely than men to say abortion should be legal in all cases.

In Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Poland, Taiwan, Vietnam and all the African and Latin American countries surveyed, men and women have more similar views on abortion.

Note: Here are the questions used for this analysis , along with responses, and the survey methodology . This is an update of a post originally published June 20, 2023.

- Household Structure & Family Roles

- International Issues

- Religion & Abortion

Janell Fetterolf is a senior researcher focusing on global attitudes at Pew Research Center .

Laura Clancy is a research analyst focusing on global attitudes research at Pew Research Center .

Americans overwhelmingly say access to IVF is a good thing

Among parents with young adult children, some dads feel less connected to their kids than moms do, most east asian adults say men and women should share financial and caregiving duties, parents, young adult children and the transition to adulthood, public has mixed views on the modern american family, most popular.

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics