QUEEN ELIZABETH I

Tilbury speech.

This speech was given by Queen Elizabeth to her troops, fighting the Spanish Armada, on 9 August 1588 at Tilbury in Essex. My loving people, We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm! To which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns, and We do assure you in the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

The Spanish Armada Bookshop

The Spanish Armada

This website is an affiliate of amazon and a small commission is earned on all purchases made through this website.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Spanish Armada

By: History.com Editors

Updated: September 6, 2019 | Original: May 2, 2018

The Spanish Armada was an enormous 130-ship naval fleet dispatched by Spain in 1588 as part of a planned invasion of England. Following years of hostilities between Spain and England, King Philip II of Spain assembled the flotilla in the hope of removing Protestant Queen Elizabeth I from the throne and restoring the Roman Catholic faith in England. Spain’s “Invincible Armada” set sail that May, but it was outfoxed by the English, then battered by storms while limping back to Spain with at least a third of its ships sunk or damaged. The defeat of the Spanish Armada led to a surge of national pride in England and was one of the most significant chapters of the Anglo-Spanish War.

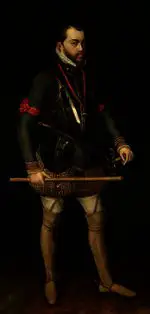

Philip and Elizabeth

King Philip II ’s decision to attempt an overthrow of Queen Elizabeth I was several years in the making.

Despite their family connections—Philip had once been married to Elizabeth’s half-sister, Mary —the two royals had severe political and religious differences and had engaged in a “cold war” for much of the 1560s and 1570s.

Philip was particularly incensed by the spread of Protestantism in England, and he had long toyed with the idea of conquering the British Isle to bring it back into the Catholic fold.

Tensions between Spain and England flared in the 1580s, after Elizabeth began allowing privateers such as Sir Francis Drake to conduct pirate raids on Spanish fleets carrying treasure from their rich New World colonies.

By 1585, when England signed a treaty of support with Dutch rebels in the Spanish-controlled Netherlands, a state of undeclared war existed between the two powers. That same year, Philip began formulating an “Enterprise of England” to remove Elizabeth from the throne.

What Was the Spanish Armada?

The Spanish Armada was a naval force of about 130 ships, plus some 8,000 seamen and an estimated 18,000 soldiers manning thousands of guns. Roughly 40 of the ships were warships.

The Spanish plan called for this “Great and Most Fortunate Navy” to sail from Lisbon, Portugal, to Flanders, where it would rendezvous with 30,000 crack troops led by the Duke of Parma, the governor of the Spanish Netherlands.

The fleet would then guard the army as it was ferried across the English Channel to the Kent coast to begin an overland offensive against London.

England Prepares for Invasion

It was impossible for Spain to hide the preparations for a fleet as large as the Armada, and by 1587, Elizabeth’s spies and military advisors knew an invasion was in the works. That April, the Queen authorized Francis Drake to make a preemptive strike against the Spanish.

After sailing from Plymouth with a small fleet, Drake launched a surprise raid on the Spanish port of Cadiz and destroyed several dozen of the Armada’s ships and over 10,000 tons of supplies. The “singeing of the king of Spain’s beard,” as Drake’s attack was known in England, was later credited with delaying the launch of the Armada by several months.

The English used the time bought by the raid on Cadiz to shore up their defenses and prepare for invasion.

Elizabeth’s forces built trenches and earthworks on the most likely invasion beaches, strung a giant metal chain across the Thames estuary and raised an army of militiamen. They also readied an early warning system consisting of dozens of coastal beacons that would light fires to signal the approach of the Spanish fleet.

Led by Drake and Lord Charles Howard, the Royal Navy assembled a fleet of some 40 warships and several dozen armed merchant vessels. Unlike the Spanish Armada, which planned to rely primarily on boarding and close-quarters fighting to win battles at sea, the English flotilla was heavily armed with long-range naval guns.

Spanish Armada Sets Sail

In May 1588, after several years of preparation, the Spanish Armada set sail from Lisbon under the command of the Duke of Medina-Sidonia. When the 130-ship fleet was sighted off the English coast later that July, Howard and Drake raced to confront it with a force of 100 English vessels.

The English fleet and the Spanish Armada met for the first time on July 31, 1588, off the coast of Plymouth. Relying on the skill of their gunners, Howard and Drake kept their distance and tried to bombard the Spanish flotilla with their heavy naval cannons. While they succeeded in damaging some of the Spanish ships, they were unable to penetrate the Armada’s half-moon defensive formation.

Over the next several days, the English continued to harass the Spanish Armada as it charged toward the English Channel. The two sides squared off in a pair of naval duels near the coasts of Portland Bill and the Isle of Wight, but both battles ended in stalemates.

By August 6, the Armada had successfully dropped anchor at Calais Roads on the coast of France, where Medina-Sidonia hoped to rendezvous with the Duke of Parma’s invasion army.

Fireships Scatter the Armada

Desperate to prevent the Spanish from uniting their forces, Howard and Drake devised a last-ditch plan to scatter the Armada. At midnight on August 8, the English set eight empty vessels ablaze and allowed the wind and tide to carry them toward the Spanish fleet hunkered at Calais Roads.

The sudden arrival of the fireships caused a wave of panic to descend over the Armada. Several vessels cut their anchors to avoid catching fire, and the entire fleet was forced to flee to the open sea.

Battle of Gravelines

With the Armada out of formation, the English initiated a naval offensive at dawn on August 8. In what became known as the Battle of Gravelines, the Royal Navy inched perilously close to the Spanish fleet and unleashed repeated salvos of cannon fire.

Several of the Armada’s ships were damaged and at least four were destroyed during the nine-hour engagement, but despite having the upper hand, Howard and Drake were forced to prematurely call off the attack due to dwindling supplies of shot and powder.

Speech to the Troops at Tilbury

With the Spanish Armada threatening invasion at any moment, English troops gathered near the coast at Tilbury in Essex to ward off a land attack.

Queen Elizabeth herself was in attendance and - dressed in military regalia and a white velvet gown - she gave a rousing speech to her troops, one that is often cited as among the most inspiring speeches ever written and delivered by a sovereign leader:

"I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field."

Bad Weather Besets the Armada

Shortly after the Battle of Gravelines, a strong wind carried the Armada into the North Sea, dashing the Spaniards’ hopes of linking up with the Duke of Parma’s army. With supplies running low and disease beginning to spread through his fleet, the Duke of Medina-Sidonia resolved to abandon the invasion mission and return to Spain by rounding Scotland and Ireland.

The Spanish Armada had lost over 2,000 men during its naval engagements with the English, but its journey home proved to be far more deadly. The once-mighty flotilla was ravaged by sea storms as it rounded Scotland and the western coast of Ireland. Several ships sank in the squalls, while others ran aground or broke apart after being thrown against the shore.

Defeat of the Spanish Armada

By the time the “Great and Most Fortunate Navy” finally reached Spain in the autumn of 1588, it had lost as many as 60 of its 130 ships and suffered some 15,000 deaths.

The vast majority of the Spanish Armada’s losses were caused by disease and foul weather, but its defeat was nevertheless a triumphant military victory for England.

By fending off the Spanish fleet, the island nation saved itself from invasion and won recognition as one of Europe’s most fearsome sea powers. The clash also established the superiority of heavy cannons in naval combat, signaling the dawn of a new era in warfare at sea.

While the Spanish Armada is now remembered as one of history’s great military blunders, it didn’t mark the end of the conflict between England and Spain. In 1589, Queen Elizabeth launched a failed “English Armada” against Spain.

King Philip II, meanwhile, later rebuilt his fleet and dispatched two more Spanish Armadas in the 1590s, both of which were scattered by storms. It wasn’t until 1604—over 16 years after the original Spanish Armada set sail—that a peace treaty was finally signed ending the Anglo-Spanish War as a stalemate.

The Spanish Armada. By Robert Hutchinson . The Spanish Armada. BBC . Sir Francis Drake. By John Sugden . The Spanish Armada: England’s Lucky Escape. History Extra . Elizabeth's Tilbury speech: July 1588. British Library .

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

The History Place - Great Speeches Collection

The History Place - YouTube Channel

Speech to the Troops at Tilbury - Aug. 19, 1588

The 1500s saw a major rivalry between Britain and Spain over control of trade in the New World. King Philip II of Spain assembled a fleet of warships known as the Spanish Armada and in 1588 sailed into the English Channel with the goal of invading and conquering England. Queen Elizabeth I is reported to have delivered an inspiring speech when she visited her troops assembled at Tilbury (Essex) as they prepared for battle. During the nine-day battle, the British ships inflicted terrible losses on the Spanish Armada. Spanish ships attempting to return to Spain encountered inclement weather and few made it back. Following the defeat of the Spanish Armada, Britain became the dominant world power for several centuries.

The version of the speech generally accepted as the speech that was given by Queen Elizabeth was found in a letter from Leonel Sharp (1559-1631), an English churchman and courtier, royal chaplain and archdeacon of Berkshire, to the Duke of Buckingham sometime after 1624.

My loving people

We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust.

I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you on a word of a prince, they shall be duly paid. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over these enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

Another version of the speech was recorded in 1612 by William Leigh (1550 to 1639), an English clergyman and royal tutor.

Come on now, my companions at arms, and fellow soldiers, in the field, now for the Lord, for your Queen, and for the Kingdom. For what are these proud Philistines, that they should revile the host of the living God? I have been your Prince in peace, so will I be in war; neither will I bid you go and fight, but come and let us fight the battle of the Lord. The enemy perhaps may challenge my sex for that I am a woman, so may I likewise charge their mould for that they are but men, whose breath is in their nostrils, and if God do not charge England with the sins of England, little do I fear their force… Si deus nobiscum quis contra nos? (if God is with us, who can be against us?)

In "Elizabetha Triumphans," published in 1588, James Aske provides another version of the speech.

Their loyal hearts to us their lawful Queen.

For sure we are that none beneath the heavens

Have readier subjects to defend their right:

Which happiness we count to us as chief.

And though of love their duties crave no less

Yet say to them that we in like regard

And estimate of this their dearest zeal

(In time of need shall ever call them forth

To dare in field their fierce and cruel foes)

Will be ourself their noted General

Ne dear at all to us shall be our life,

Ne palaces or Castles huge of stone

Shall hold as then our presence from their view:

But in the midst and very heart of them

Bellona-like we mean as them to march;

On common lot of gain or loss to both

They well shall see we recke shall then betide.

And as for honour with most large rewards,

Let them not care they common there shall be:

The meanest man who shall deserve a might,

A mountain shall for his desart receive.

And this our speech and this our solemn vow

In fervent love to those our subjects dear,

Say, seargeant-major, tell them from our self,

On kingly faith we will perform it there…

Neither the Catt Center nor Iowa State University is affiliated with any individual in the Archives or any political party. Inclusion in the Archives is not an endorsement by the center or the university.

A Short Analysis of Queen Elizabeth I’s ‘Heart and Stomach of a King’ Speech at Tilbury

By Dr Oliver Tearle (Loughborough University)

Queen Elizabeth I’s speech to the troops at Tilbury is among the most famous and iconic speeches in English history. On 9 August 1588, Elizabeth addressed the land forces which had been mobilised at the port of Tilbury in Essex, in preparation for the expected invasion of England by the Spanish Armada.

The speech has become inextricably linked with Elizabeth’s reign, which is often called the ‘Golden Age’ of English power and confidence. Elizabeth’s reign was the settling of the earliest English colonies in America, the establishment of the first London theatres, the early works of William Shakespeare and John Donne, and much else.

However, how authentic is the reported text of the speech Elizabeth gave on that day, and did she really tell her loyal troops that, although she had ‘the body of a weak and feeble woman’, she had ‘the heart and stomach of a king’?

Many historians accept the speech of Elizabeth I as genuine, and believe the words quoted above have an authentic ring to them: they were delivered, and probably written, by Elizabeth herself. Elizabeth was also a somewhat gifted poet , so it should little surprise us that she had a fine turn of phrase when it came to speech-writing, too.

However, no contemporary account of the exact words used in the speech is in existence. Indeed, one of the earliest recorded versions of the speech contains quite different words from those quoted above. In 1612 a preacher named William Leigh offered this version of Elizabeth’s words:

The enemy perhaps may challenge my sex for that I am a woman, so may I likewise charge their mould for that they are but men, whose breath is in their nostrils, and if God do not charge England with the sins of England, little do I fear their force… Si deus nobiscum quis contra nos?

This final Latin phrase can be translated as ‘if God is with us, who can be against us?’

It was not until more than a decade later, in the 1620s, that the more familiar wording of Elizabeth’s speech was first written down, when Leonel Sharp included it in a letter to the Duke of Buckingham. This letter was published in 1654. In it, Sharp wrote,

The queen the next morning rode through all the squadrons of her army as armed Pallas attended by noble footmen, Leicester, Essex, and Norris, then lord marshal, and divers other great lords. Where she made an excellent oration to her army, which the next day after her departure, I was commanded to redeliver all the army together, to keep a public fast.

It is Sharp’s version of the speech that has become canonical, and many consider his to be closer to the wording that Elizabeth is likely to have used during the delivery of her speech.

But what marks both versions of the speech out is Elizabeth’s emphasis on her sex. In Leigh’s account of the speech, Elizabeth tells her English troops that the Spanish enemy may believe her to be an ineffectual ruler because she is a woman, rather than being a ‘strong’ man who can lead his troops into battle. But she responds to this hypothetical criticism by reminding her audience that the Spanish enemy are but men, who are mortal (and can therefore be killed).

In Sharp’s more famous version, the wording has become well-known, of course: ‘I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too’. In other words, Elizabeth acknowledges the fact that her body is naturally less masculine and strong than the average man’s, but it is not mere physical strength that will win the day. Instead, the ‘heart’ and ‘stomach’ are important: the strength of passion with which the men are inspired to fight to defend their country from an invading foreign force.

A key part of the quotation’s success, which is undoubtedly at least partly responsible for its fame, is the balancing of the spirit and passion (heart) with the more visceral courage and willingness to fight (stomach).

Curiously, the very first version of the speech to be recorded was in 1588, the same year as the foiled attack from the Spanish Armada. And it was in verse! James Aske published the celebratory ‘ Elizabetha Triumphans ’, which contains the words:

And this our speech and this our solemn vow In fervent love to those our subjects dear, Say, seargeant-major, tell them from our self, On kingly faith we will perform it there …

Here we find no heart and stomach, and no interesting play on the Queen’s femininity or sex. This has led some historians to wonder if Sharp’s later recording of the words is unreliable and inauthentic.

But it seems more likely that Aske, churning out jingoistic doggerel while the national mood was still jubilant, was the one who took liberties with the wording used by the Queen, if he even knew what she had said on that day in August 1588.

Discover more from Interesting Literature

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Type your email…

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

[ Skip to content ] [ Skip to main navigation ] [ Skip to quick links ] [ Go to accessibility information ]

Elizabeth I's Tilbury speech: the birth of a warrior queen

Posted 09 Aug 2019, by Estelle Paranque

As generations of schoolchildren were taught, Elizabeth I of England famously said 'I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too.'

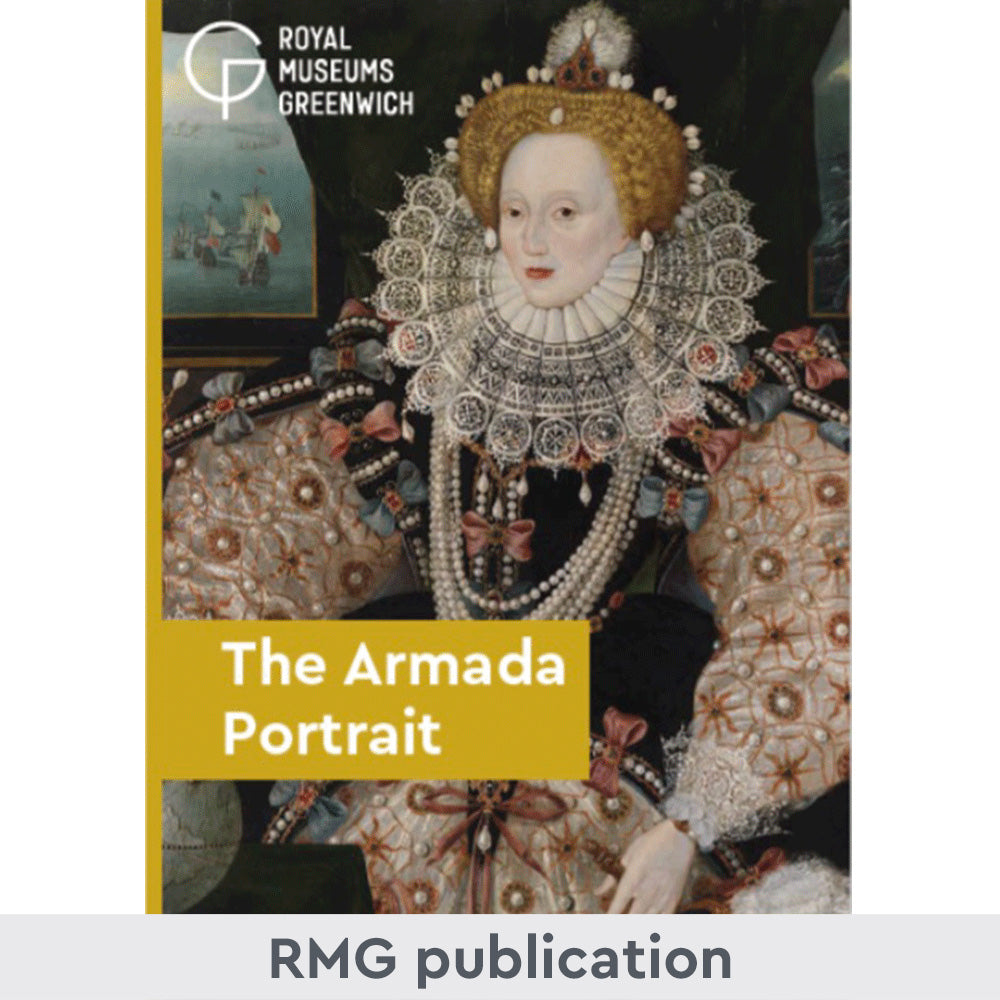

Elizabeth I (The Armada Portrait)

16th C, oil on oak panel by unknown artist

Although many great and sweeping statements have been attributed to influential figures in history over the years, leading experts on the last Tudor queen, including Professor Carole Levin, Professor Steven May, and Professor Janet M. Green, agree that it is very likely that she actually said these words. They are part of a longer version of a piece of rhetoric known as the Tilbury speech , delivered on 9th August 1588, which also marks the defeat of the Spanish Armada and propelled England to the top ranks of Europe's powerful navies.

Launch of Fire Ships against the Spanish Armada, 7 August 1588 c.1590

Netherlandish School

On 8th February 1587, Mary Stuart, former queen of Scots, was executed for being involved in the 1586 Babington Plot. Philip II of Spain, allied with the Guises (Mary Stuart's French family), promised to avenge her. In reality, he saw this as an opportunity to justify an attack on England, since Philip and Elizabeth had been mortal enemies for some years by this point and Spain had long been preparing for an invasion.

Preparatory Sketches of Phillip II of Spain and Elizabeth I c.1854

Richard Burchett (1815–1875) (studio of)

As news of the invasion spread, England got ready for war. Ships were built and ports were armed. The Elizabethan navy was swiftly becoming the best in Europe, attacking Spanish and French cargo ships coming from the New World and stealing their goods and gold to be brought to Elizabeth. Perhaps inevitably, the war began – as the painting below depicts.

English Ships and the Spanish Armada, August 1588 late 16th C

British (English) School

As the battle closed, a storm was ravaging the coast of England. English ships, smaller and more manoeuvrable, got through the tempest, while Spanish galleons, twice the size of English ships and far less manageable, were harried and capsized by the wind and the rain. English sailors and warriors saw this as an opportunity to intensify the attacks. This thorough defeat for the Spanish has been remembered for centuries, becoming the subject of a great deal of artistic expression during the period, particularly in England. The painting by Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740–1812) is a remarkable example of this.

Defeat of the Spanish Armada, 8 August 1588 1796

Philip James de Loutherbourg (1740–1812)

England's victory was quickly portrayed as Elizabeth's victory. From her success over Spain and her mortal enemy Philip II, more and more Elizabeth was represented as a warrior queen, both artistically, in literature and in the political world of the time. In the painting below, she is portrayed rallying her troops atop a white horse, every inch the leader of Englishmen and warriors.

Queen Elizabeth I at Tilbury, 1588 c.1938

Alfred Kingsley Lawrence (1893–1975)

Elizabeth had done the impossible: defeating the 'invincible' Spanish Armada. One of the most famous portraits of her is the Armada Portrait (seen at the top of this article, in the collection of Woburn Abbey) which was then reproduced and copied by different artists, such as the one formerly thought to be by George Gower (in the National Portrait Gallery) and the one now in the Queen's House (Royal Museums Greenwich), acquired for the nation in 2016.

Queen Elizabeth I c.1588

George Gower (c.1540–1596) (formerly attributed to)

Elizabeth I (1533-1603) (the 'Armada Portrait') c.1588

She is depicted sitting victoriously, with very strong – to not say enormous – arms to emphasise her virility and warlike image. From now on, Elizabeth was more than the Virgin Queen: she was Gloriana, and through this image of Gloriana she became a warrior queen, with a strong masculine stance.

After 1588, Elizabeth was portrayed as a dominant and powerful queen who controlled Europe. Another famous portrait of the queen, the Ditchley Portrait, shows her standing on the map of the world as a victorious monarch.

Queen Elizabeth I ('The Ditchley portrait') c.1592

Marcus Gheeraerts the younger (1561/1562–1635/1636)

She represents glory, stability, and prosperity. The artist wished to indicate that after her confident and successful rule, only chaos could happen, hence the storm clouds gathering behind her.

In this portrait by Nicholas Hilliard, exhibited at Hardwick Hall, Elizabeth also has the same strong, masculine stance portrayed in the Ditchley Portrait.

Elizabeth I (1533–1603) 1592

Nicholas Hilliard (1547–1619) (studio of)

Her arms are also enormous and her hand, poised on the armrest of the royal chair, points out to her initials: Elizabeth Regina, the symbol of her monarchical authority. Most historians, such as Professor John Guy, argue that there are two reigns of Elizabeth. In many ways, 1588 and the victory over the Spanish Armada mark the beginning of the second one. Elizabeth is no longer viewed in the royal houses of Europe as a potential bride for their princes. She is Gloriana, the famous warrior queen who defeated the most powerful country of Europe at that time: Spain.

After her death, artists and commentators clung to this warrior image, which was frequently reproduced and conveyed in portraits.

Elizabeth I (1533–1603), with a Miniature Sieve late 16th C & later

This portrait, for example, is an early seventeenth-century portrait of the queen exhibited at Charlecote Park in Warwickshire. Elizabeth's strong, masculine arms remind the viewer of the Armada Portrait. Despite the dark colours of this painting, Elizabeth is depicted as Gloriana.

Moving forward in time, Riehé was a mid-nineteenth-century artist who painted a series of English monarchs, including Victoria, Henry VIII, and Elizabeth, many of which presently hang in Hull Guildhall.

Elizabeth I (1533–1603)

His depiction of the English queen is particularly masculine, looking more like a young man than a queen in her prime. All her feminine features have been masculinised. Her usual fairy wings or collar are replaced by an ornate bodice that looks more like a vest. It seems that the artist decided to paint a male version of Elizabeth to demonstrate her greatness as a ruler, which is perhaps unsurprising, given Victorian views of a woman's place in society.

The last major portrait showing Elizabeth as a warrior queen after her death is by Wilhelm Sonmans. A Dutch artist who lived at Charles II's court, Sonmans died in 1708, but during his career he painted important political figures of the seventeenth century.

Elizabeth I (1533–1603) c.1670 (?)

Wilhelm Sonmans (1650–1708)

In his portrait of Elizabeth, Sonmans decided to reproduce the strong and masculine arms earlier artists had gifted to the warrior queen. On the left top corner, her coat of arms with the lion and dragon stands out – reinforcing the image of the warrior queen, Gloriana. Her stance in this portrait reminds the viewer of the Ditchley and Armada portraits, which were likely influences.

Elizabeth I of England is one of the most famous English monarchs and the public has shown great interest in her reign. Her victory over the Spanish Armada is arguably what makes her so well known. To some extent, through this victory, Elizabeth was reborn, going from the virgin queen to a distinguished warrior queen, an image that was presented and remembered centuries after her death. One can easily claim that, true to her own words, she had 'the heart and stomach of a king.'

Estelle Paranque, historian and author

Further reading John Guy, Elizabeth: The Forgotten Years , Penguin, 2016 Peter Lake and Michael Questier, All Hail to the Archpriest: Confessional Conflict, Toleration, and the Politics of Publicity in Post-Reformation England , OUP, 2019 Carole Levin, The Heart and Stomach of a King: Elizabeth I and the Politics of Sex and Power , University of Pennsylvania Press, second edition, 2013 Estelle Paranque (ed.), Remembering Queens and Kings of Early Modern England and France: Reputation, Reinterpretation, and Reincarnation , Palgrave Macmillan, 2019 Kevin Sharpe, Selling the Tudor Monarchy: Authority and Image in Sixteenth-century England , Yale University Press, 2009

- Share on Facebook

- Share on Twitter

More stories

Learning resources

Queen Elizabeth I: Speech to the Troops at Tilbury. 1

Let tyrants fear; I have always so behaved myself, that under God I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good will of my subjects; and, therefore, I am come amongst you as you see at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live or die amongst you all - to lay down for my God, and for my kingdoms, and for my people, my honor and my blood even in the dust.

I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king - and of a King of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which, rather than any dishonor should grow by me, I myself will take up arms - I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

I know already, for your forwardness, you have deserved rewards and crowns, and, we do assure you, on the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. For the meantime, my Lieutenant General Leicester shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my General, by your concord in the camp, and your valor in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over these enemies of my God, of my kingdom and of my people.

More History

Elizabeth I and the Spanish Armada

How did England under Elizabeth I defend itself from the Spanish Armada?

In December 1587 Queen Elizabeth I put Lord Howard of Effingham in charge of England’s defence against the Spanish Armada.

Although not a celebrated sailor like Sir Francis Drake , Effingham was an able commander and had the support of the nobility. He was also known for his willingness to listen to those more experienced, such as Drake, who was appointed his Vice-Admiral.

Intelligence and diplomacy

Howard's appointment was key, as his aristocratic lineage gave him the authority to keep the huge egos under him, such as Drake, in check. The English fleet was mobilised and intelligence continued to be gathered about the timing and route of the attack, as well as the numbers of ships and troops involved.

During this time, Queen Elizabeth I continued to negotiate with the Duke of Parma about a solution to the situation in the Netherlands.

The Armada in sight

On 19 July 1588 the Spanish Armada was sighted off the Lizard in Cornwall. A fast English ship conveyed the news and a series of beacons were lit along the coast to spread the warning. The English fleet based at Plymouth attempted to disrupt the Armada's passage and managed to inflict some damage but could not stop it.

The Armada anchored off Calais on 27 July 1588. The Duke of Parma and his army had not yet arrived to join them, so the English fleet used this advantage sending in eight fireships on the night of 28 July. Although no Spanish ships caught fire, the attack made the Spaniards panic, cut their anchor cables and scatter out to sea to avoid them. A day of fierce fighting between the two fleets followed, later called the Battle of Gravelines. During this battle the Spanish were blown dangerously close to the shore. Then the wind changed and they sailed northward in disorder.

Defeat of the Spanish Armada

On 31 July 1588 the Spanish fleet tried to turn around to join Parma and his army again. However, the prevailing south-west winds prevented them from doing so.

The decision was made to give up and return to Spain by sailing north around Scotland. Howard and his fleet pursued them into the North Sea for three days until it became clear they were leaving. Bad storms completed the Spanish defeat: many of their fleeing Spanish ships were wrecked off the coasts of Scotland and Ireland. Less than half the fleet made it back to Spain.

The Armada Portrait

The Armada Portrait commemorates the most famous conflict of Elizabeth I's reign – the failed invasion of England by the Spanish Armada in summer 1588. This iconic portrait is now back on public display in the Queen's House after careful conservation.

Find out more and visit The Armada Portrait

Shop for gifts inspired by an iconic Queen

Understand the context, creation and significance of the Armada Portrait in our concise guide. Indulge in gifts inspired by its Elizabethan symbolism

- Recent changes

- Random page

- View source

- What links here

- Related changes

- Special pages

- Printable version

- Permanent link

- Page information

- Create account

How did the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588) change England

The defeat and destruction of the Spanish Armada in 1588 are seen by many as the high point of Elizabeth I’s of England’s reign. If the Armada had been successful, it could have changed the course of English and world history. The defeat of the Armada had profound consequences for England. The first consequence of the English victory was that it secured its independence.

With the defeat of the Armada, England becomes a serious European naval power. Britain's navy was the foundation of the future British Empire. As a result of the failed invasion by Catholic Spain, England became more self-consciously Protestant, and Catholicism became increasingly unpopular and was viewed as anti-English. The English also saw the defeat of the Armada as an act of divine providence. It confirmed to them that England was a kingdom destined for greatness.

Why did Spain send the Spanish Armada to invade England?

The Spanish King Phillip II was an ardent Catholic, and he had two primary ambitions. First, he wanted to return all Protestants to the Catholic faith. Second, he hoped to expand the growing power of Spain. The Spanish King had been married to Mary I of England, and it seemed that England would fall under Spanish influence for a time. However, Elizabeth I's coronation had fundamentally altered this dynamic because she was determined to maintain England's independence from Spain. On the other hand, Spain wanted to force the English back into the Catholic fold and end the English pirates' attacks on their ships and colonies in the Americas.

Elizabeth, I had encouraged English privateers, such as Sir Francis Drake, to mount attacks on Spanish targets. Elizabeth sought to limit Spain's power and secure some of the riches ‘of the american colonies for her subjects.’ [2] The English Queen also supported the Dutch in their revolt against Phillip II. Relations between Spain and England deteriorated rapidly, and by the mid-1580s, the two countries were in an undeclared war. A war that was to last until the end of Elizabeth’s reign. Spain was the richest and the most powerful Empire in Europe, and Phillip decided to invade England. He believed that it would help him secure many of Europe's strategic objectives if he were successful. The Spanish presented the Armada as a Catholic crusade, and the Papacy partially funded it.

How did England defeat the Spanish Armada?

The Armada launch had been delayed several times, including once because of a raid by the English on Cadiz. The Spanish Armada was a fleet of 130 ships, and it first left the port of Coruna in August 1588, under the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the most powerful noble in Spain. [3] The fleet was ordered to sail to the English Channel and transport a large army in Flanders into England. The invasion aimed to depose Elizabeth I and to reimpose Catholicism on the English people. The fleet was impressive, and the Spanish were experienced, sailors and navigators. However, the commander Medina-Sidonia was old and relatively inexperienced, and he committed mistake after mistake throughout the campaign.

Despite its numerical advantage, the Spanish fleet did not attack the English fleet based at Portsmouth and instead sailed to Calais. The Spanish army under the Duke of Parma was advancing to Calais to be transported to England. However, the English navy under Drake and Howard attacked the Armada with fireships, and this was the start of what became known as the Battle of Grave lines. The English tactic of using fire-ships created panic among the Spaniards, and the fleet was broken up into small groups of ships. The battle lasted over a week, with both sides launching attacks. However, Medina-Sidonia decided to withdraw. This decision was decisive as it meant that the Spanish army could not rendezvous with the invasion army. Drake and the other English commanders were happy to let the Armada sail away from the invasion force. A strong wind from the southwest forced the fleet to sail to the north and into the North Sea.

How was the Spanish Armada destroyed?

Medina-Sidonia tried to regroup his ships and withdraw to Spain. This ended Spain's attempt to invade England, but it did not end the Armada's problems. At this point, the Armada sought only to survive and return to Spain. Unfortunately, inclement weather and a strong south-western wind meant that the Spanish could not return via the English Channel. This wind later became known in England as a ‘Protestant Wind.’ [4]

The Spanish Command, which could not communicate with Madrid, decided to round the British Isles. The Armada sailed around Scotland, but the English navy continued to harry the Spanish fleet. The weather was very unseasonable for that time of year, and strong gales and massive storms battered Phillip's fleet. As the Armada made their way around Scotland, they began to lose ships. Many more ships were wrecked on the west coast of Ireland, and the survivors were hunted down and killed by natives loyal to the English crown. [5] By the time that the remnants of the Spanish invasion fleet made it to Spain, over two-thirds of the original Armada was lost. While the Spanish Armada's defeat did not end the undeclared Anglo-Spanish War, which would continue until 1604, it made it difficult for Spain to get the upper hand. Eventually, the conflict ended in a stalemate.

Could Spain have taken England it had successfully landed its invasion force?

The Spanish Armada is one of the great ‘ifs’ in history. If the Spanish ships had been able to rendezvous with Flanders' army and transported it across the Channel, England may have been defeated. The Spanish army was considered the best in Europe at this time, and it was composed not only of Spanish but also German veterans. The English army was mainly composed of local militias and was poorly led and trained. In a set-piece battle, the Spanish forces would most likely have been victorious and deposed Elizabeth I on land.

The kingdom of England would have become part of the Spanish Empire. Phillip II did not plan to rule it directly but planned to place a Catholic on the throne. Philip wanted an ally that would become dependent on Spain. The defeat of the Armada prevented this from happening and secured the independence of England. England's victory allowed her to become a major world power by the eighteenth century. [6]

What impact did the defeat of the Spanish Armada have on Catholics in England?

Phillip II wanted to return England to Catholicism. If the Armada had been successful, then it seems likely that a Catholic king or queen would have been placed on the throne. They would have had the power to overturn the Protestant establishment in the country. No longer would the Church of England by the state church, and once again, the Catholic Church would have been the only recognized religion.

Phillip II believed that it was right for a monarch to ensure religious conformity in their kingdom. The new Catholic monarch probably would have persecuted Protestants in much the same way as Mary I had during her reign. With Catholicism re-established, this could have hobbled Protestantism in England.

By the 1580s, the Church of England was supported by most English people, and they would have resisted any attempt to reimpose the Catholic faith. Still, England would likely have suffered a series of Religious Wars similar to France in the sixteenth century. However, the Armada's failure meant that the Church of England was now more secure than ever before. Increasingly, the English people began to see themselves as Protestant people. They saw Protestantism as an integral part of Englishness and important for their freedom. Many English people became even more anti-Catholic after the Armada. ‘Popery’ as they referred to as Catholicism, was associated with autocracy, intolerance, and slavery. This anti-Catholicism was an important aspect of English political life for many years. [7]

On the other hand, English Catholics faced an increasingly difficult life in England after the Armada's destruction. Catholics, known as ‘recusants,’ refused to recognize the Church of England. They came under official and unofficial pressure to conform to the state religion and give up their faith. [8] Even loyal English Catholics became suspect, and as a result, more and Catholics converted to Protestantism.

By the end of Elizabeth's reign, England was a Protestant nation, with only a small oppressed Catholic minority. The Armada had played an important role in this process. Phillip II had attempted to overturn the religious settlement in England, but his attempted invasion only strengthened it. England's people began to see themselves in providential terms and biblical terms as an ‘elect nation.’ [9] The English began to believe that they were chosen by God to carry out his will. This sense of mission was crucial in later decades and was an important factor in the growth of English power, especially in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Did the defeat of the Spanish Armada turn England into a naval power?

It has often been stated that the Armada's defeat ended the Spanish superiority at sea and began England’s rise as a global naval power. This was not the case. The year following the Spanish Armada defeat, the English monarch launched the ‘English Armada.’ [10]

This was a naval attack on Spain was heavily defeated with substantial English losses. Madrid changed its strategy, and a series of fortifications were built in the Americas that gave greater protection against English and other privateers. Spain, after the defeat of the Armada, remained the premier maritime power outside China.

However, the Armada defeat did lead to long-term changes that proved to be very important in England's rise as a naval power. After the attempted Spanish invasion, there was a recognition that the English needed a strong navy, and successive English administrations pursued policies that helped to expand the navy. England focused on developing new technologies and building ‘modern shipyards.’ [11] These changes laid the groundwork for England's naval power.

Additionally, if the Spanish Armada had been a success, it is improbable that England would have successfully plant colonies in North America. In the early seventeenth century, English colonies were founded at Plymouth Rock and Jamestown. If the Spanish had placed one of their candidates on England's throne, this might never have occurred. The Armada's defeat saw England emerge as, if not a dominant naval power but an important one, and the principal colonizer of North America. Additionally, English trading companies such as the East India Company expanded across the globe. [12] England's naval capability directly led to the British Empire's growth and development.

The defeat of the Armada was a major turning point in English history. It saved the throne of Elizabeth I and guaranteed English independence from Spain. The Spanish saw the invasion as a crusade and one that would stamp out the heresy of Protestantism in England. The failure of the invasion meant that Protestantism became more entrenched and less sympathetic to Catholicism. Indeed, in the aftermath of the Armada, Protestantism became part of the national identity. To be English was to be a Protestant and to reject Catholicism.

The attempted Spanish invasion led to the adoption of an anti-Catholic discourse, known as Popery, and this was an important factor in English political life for over two centuries. The Armada did not end Spanish maritime supremacy, but it did lead to England becoming a formidable naval power. This allowed it to found colonies and trading companies in the early seventeenth century to lay the British Empire's foundation.

- ↑ Duffy, E. Stripping of the Altars (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 113

- ↑ Holmes, Richard. The Oxford Companion to Military History (Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2001), p. 214

- ↑ Holmes, p. 215

- ↑ McDermott, James. England and the Spanish Armada: The Necessary Quarrel . (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), P. 215

- ↑ T. P. Kilfeather. Ireland: Graveyard of the Spanish Armada (Anvil Books, 1967), p. 167

- ↑ Holmes, p. 257

- ↑ Bridgen, Susan. New Worlds, Lost Worlds: The Rule of the Tudors, 1485–1603 . New York, NY: Viking Penguin, 2001), p. 115

- ↑ Bridgen, p. 234

- ↑ Krishan Kumar. The Making of English national identity (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2003), p. 45

- ↑ Bridgen, p. 135

- ↑ Holmes, p. 217

- ↑ Holmes, p. 256

Related DailyHistory.org Articles

- What was the impact of the German Peasant War (1524-1527) on the Reformation?

- Top 10 Books on the origins of the Italian Renaissance

- How did the Renaissance influence the Reformation?

- What were the causes of the Northern Renaissance?

- Why did the Reformation fail in Renaissance Italy?

Admin , Ewhelan and EricLambrecht

- British History

- 16th Century History

- European History

- Religious History

- English History

- History of Elizabethan Age

- This page was last edited on 21 September 2021, at 01:02.

- Privacy policy

- About DailyHistory.org

- Disclaimers

- Mobile view

The Spanish Armada 8 – Elizabeth’s Tilbury Speech

In her article “The Myth of Elizabeth at Tilbury”, Susan Frye, writes that there are no reliable eye-witness accounts regarding Elizabeth I’s appearance on that day, but that tradition places the Queen in armour, giving a rousing speech – an iconic Gloriana.

Descriptions of Elizabeth I at Tilbury

Many historians and authors have described Elizabeth I on that August day in 1588:-

In “Elizabeth the Great” (1958), Elizabeth Jenkins wrote:-

“A steel corselet was found for her to wear and a helmet with white plumes was given to a page to carry. Bareheaded, the Queen mounted the white horse. The Earl of Ormonde carried the sword of state before her, Leicester walked at the horse’s bridle, and the page with the helmet came behind.”

Carolly Erickson, in “The First Elizabeth” (1983), wrote:-

“She rode through their ranks on a huge white warhorse, armed like a queen out of antique mythology in a silver cuirass and silver truncheon. Her gown was white velvet, and there were plumes in her hair like those that waved from the helmets of the mounted soldiers.”

J E Neale, in “Queen Elizabeth I: A Biography” (1934), wrote:-

“Mounted on a stately steed, with a truncheon in her hands, she witnessed a mimic battle and afterwards reviewed the army.”

In “The Armada” (1959), Garrett Mattingly wrote:-

“She was clad all in white velvet with a silver cuirass embossed with a mythological design, and bore in her right hand a silver truncheon chased in gold.”

Reading those descriptions, it is clear, as Susan Frye points out, that an analogy is being drawn between Elizabeth I and Britomart, the armed heroine of Edmund Spenser’s “The Faerie Queene”, the virgin Knight of Chastity and Virtue. However there is no firm evidence that Elizabeth dressed like that on that day, but I like to think, with Elizabeth’s love of drama and her belief in the power of image and propaganda, that she appeared before her troops just like that.

The Tilbury Speech

There are three versions of the speech that Elizabeth I gave to the troops at Tilbury. The first is recorded by Dr Leonel Sharp in a letter to the Duke of Buckingham, thought to have been written sometime after the Duke of Buckingham’s 1623 marriage expedition to Spain. Sharp’s is the most famous rendition of Elizabeth I’s speech:-

“My loving people, We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear. I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good-will of my subjects; and therefore I am come amongst you, as you see, at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live and die amongst you all; to lay down for my God, and for my kingdom, and my people, my honour and my blood, even in the dust. I know I have the body but of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king, and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which rather than any dishonour shall grow by me, I myself will take up arms, I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, for your forwardness you have deserved rewards and crowns; and We do assure you in the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean time, my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over those enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.”

The second version of the Tilbury Speech is one recorded in 1612 by William Leigh, in his sermon “Quene Elizabeth, Paraleld in Her Princely Vertues”, where he described Elizabeth appearing before her troops “with God in her heart, and a commaunding staffe in her hand” and saying the following:-

“Come on now, my companions at arms, and fellow soldiers, in the field, now for the Lord, for your Queen, and for the Kingdom. For what are these proud Philistines, that they should revile the host of the living God? I have been your Prince in peace, so will I be in war; neither will I bid you go and fight, but come and let us fight the battle of the Lord. The enemy perhaps may challenge my sex for that I am a woman, so may I likewise charge their mould for that they are but men, whose breath is in their nostrils, and if God do not charge England with the sins of England, little do I fear their force… Si deus nobiscum quis contra nos? (if God is with us, who can be against us?)”

The third version of Elizabeth’s speech appears beneath the painting of “Elizabeth at Tilbury” in St Faith’s Church, Gaywood, which was commissioned by Thomas Hare (1572 – 1634), the rector and is dated 1588, although it may well have been painted in the early 16th century. This speech, published in Susan Frye’s article, reads:-

“Now for Queene & For the kingdome I have beene your Queene in P[e]a[ce] in warre, neither will I bid you goe & Fight, but come & let us Fight the battell of the Lorde-For what ar thes proud Philistines that they should Revile the host of the Living God. It may be they will challenge my [sexe] For that I am a woman so may I charge [their] mo[uld] [flor that they ar but [men] whose breath is in theire nostrells and if God doe not charge England with the sinnes of England we shall not neede to feare what Rome or Spayne can doe against us w: whome is but An ar[mi]e o[f] Flesh where as with us in the Lord our God to Fight our battells & to helpe I with us yt skills not Greatley if all the devills in hell be against us[.]”

Frye points out that this Gaywood speech and Leigh’s record of Elizabeth’s speech are scrambled versions of one another. Frye explains this:-

“If we delete the very different prayers with which the two versions end, and amend the text of the Gaywood speech as indicated in n. 16 [in note 16 of her article, Frye notes that the words “we commend your prayers, for they will move the heavens, so doe wee your powerfull preaching, for that will shake the earth of our earthly hearts; and call us to repentance, whereby our good God may relieve us, and roote up in mercy his deferred Iudgements against us, onely be faithfull and fear not.” were excluded in the Leigh speech by her elipsis], then the Gaywood text, containing 122 words, reproduces 103 exact words of Leigh’s 147 words. Except for the lengthy Gaywood clause of 45 words (which explains why, if God does not hold England’s sins against her, no one need fear), most of the difference rests in alternate word choices: “I have beene your Queene in Peace” (Gaywood), “I have been your Prince in Peace” (Leigh); in paraphrase: “It may be they will challenge my [sexe]” (Gaywood), “the enemie perhaps may challenge my sexe” (Leigh); and in omission: “now for Queene & For the Kingdome” (Gaywood), “now for the Lord, for your Queene and for the kingdome” (Leigh).”

Frye goes on to say that the Leigh and Gaywood speeches differ enough for the Gaywood painting speech to be a copy of Leigh’s sermon, but it could well be that they are derived from Elizabeth I’s actual speech. Frye is convinced that Leigh’s speech is “a more probable Tilbury speech, while Sharp’s may be a memorial reconstruction (he was at Tilbury)” and although Sharp was present at Tilbury, he was using the wording of the speech to make a point (he feared the proposed Spanish marriage of Prince Charles) so his version could be unreliable as it is coloured by his views. There are, however, similarities between the Leigh/Gaywood version and Sharp’s version, which Frye points out:-

- Military comradery – “my companion at arms” (Leigh) and “I myself will take up arms” (Sharp).

- Elizabeth plays on her sex -“the enemie perhaps may challenge my sexe” (Leigh) and “I have the body of weak and feeble woman.” (Sharp).

Tilbury and the Virgin Queen

Do the exact details of what Elizabeth wore at Tilbury and what she really said matter? Frye argues that:-

“For no matter what happened at Tilbury, no matter what the Queen wore or said, the fictions that surround her visit became essential. Contemporaries invented a first myth as the means to connect the defeat of the Armada with the Queen’s person through her virginity. Historians and biographers perpetuated a second myth, which portrayed Elizabeth as symbolic of England’s emergent military power and, by extension, of a unified political power she did not actually command.”

and she also goes on to say that this image and mythology of Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen, whose “virtue was closely associated with the welfare of England throughout her reign”, meant that an attack on England actually constituted rape, because it was an attack on Elizabeth’s person. She talks about Louis Montrose’s discussion on the Armada Portrait and how the defeat of the Spanish Armada was “expressed in sexual terms”:-

“The Armada portrait-or, more precisely, the three extant Armada portraits, for they are nearly identical-makes a clear spatial connection in the triangle linking the two pictures of an Armada beset by storms and fireships with the virginal bow at the end of Elizabeth’s stomacher, to which our eyes are drawn by strands of virginal pearls and rows of tight, small bows.”

Interesting!

Although I knew that the painting was referring to Elizabeth as the Virgin Queen, I had never thought about the Spanish attack being seen as rape. Elizabeth saw herself as a virgin married to England, so an attack on the country was an attack on her and her virginity.

Susan Frye points out that England was definitely on the defensive during the Spanish Armada and ill prepared for an English invasion. Spain had been preparing its Armada for three years, yet England’s lack of financial credit meant that Elizabeth’s Privy Council could only take defensive measures at the last moment, e.g. the Earl of Leicester amassing troops at Tilbury in late July and early August 1588 when the Armada were already in the Channel. It is fortunate that England made good use of its lighter ships, which were easy to manoeuvre, that it had Effingham and Drake to command its fleet and that the weather (the Protestant Wind) worked against the Armada.

Susan Frye writes:-

“To those alive in 1588, England must have seemed anything but united, just as Elizabeth’s Tilbury visit may have only provided ineffectual pageantry, for she performed before unpaid and illequipped and even hungry soldiers, many of whom, we know from royal proclamation, tried to sell their armor the moment they were disbanded. Nevertheless, the Queen’s review of the troops proved a brilliant stroke, which grew more brilliant in the succeeding weeks, years, and centuries because it provided a moment through which generations could cast Elizabeth I as the powerful political icon she remains.”

and I think she has hit the nail on the head. Elizabeth’s visit to the troops was essential to raise morale and as propaganda. Elizabeth knew just what she was doing!

Elizabeth’s understanding of the importance of image has led to us, over 400 years later, still regarding her as the Virgin Queen and Gloriana, the monarch who brought a Golden Age to England. How powerful is that?!

Notes and Sources

- “The Myth of Elizabeth at Tilbury” by Susan Frye from “The Sixteenth Century Journal”, Vol.23, No.1, Spring 1992, p95-114, found at JSTOR

Related posts:

Elizabeth I Pages

- Privacy Policy

- Queen Elizabeth I Biography

- Elizabeth I Photo Gallery

- Queen Elizabeth I Information

- Elizabeth I Question and Answer

Elizabeth I Categories

Elizabeth i archives.

Copyright © 2024 The Elizabeth Files

Design by ThemesDNA.com

Tuesday Sep 19, 2023

Elizabeth I, Against the Spanish Armada, 1588

England's greatest Queen gives her most well-known speech, as her nation faces utter disaster with the approach of the Spanish Armada.

My loving people, we have been persuaded by some, that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people. Let tyrants fear; I have always so behaved myself that, under God, I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and good will of my subjects. And therefore I am come amongst you at this time, not as for my recreation or sport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of the battle, to live or die amongst you all; to lay down, for my God, and for my kingdom, and for my people, my honour and my blood, even the dust.

I know I have but the body of a weak and feeble woman; but I have the heart of a king, and of a king of England, too; and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realms: to which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take up arms; I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field. I know already, by your forwardness, that you have deserved rewards and crowns; and we do assure you, on the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. In the mean my lieutenant general shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble and worthy subject; not doubting by your obedience to my general, by your concord in the camp, and by your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over the enemies of my God, of my kingdom, and of my people.

Comments (0)

To leave or reply to comments, please download free Podbean iOS App or Android App

No Comments

To leave or reply to comments, please download free Podbean App.

Queen Elizabeth I Speech – Spanish Armada

Queen Elizabeth I speech to her troops facing the Spanish Armada in 1588.

Elizabeth I addresses her troops at Tilbury in the county of Essex in England on the eve of battle with the Spanish Armada in 1588. England won the battle and defeated the Spanish attempts to take the country.

“My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that we are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but, I do assure you, I do not desire to live to distrust my faithful and loving people.

Let tyrants fear, I have always so behaved myself, that under God I have placed my chiefest strength and safeguard in the loyal hearts and goodwill of my subjects; and, therefore, I am come amongst you as you see at this time, not for my recreation and disport, but being resolved, in the midst and heat of battle, to live or die amongst you all – to lay down for my God, and for my kingdoms, and for my people, my honour and my blood even in the dust.

I know I have the body of a weak, feeble woman; but I have the heart and stomach of a king – and of a king of England too, and think foul scorn that Parma or Spain, or any prince of Europe, should dare to invade the borders of my realm; to which, rather than any dishonour should grow by me, I myself will take up arms – I myself will be your general, judge, and rewarder of every one of your virtues in the field.

I know already, for your forwardness, you have deserved rewards and crowns, and, we do assure you, on the word of a prince, they shall be duly paid you. For the meantime, my Lieutenant-General Leicester shall be in my stead, than whom never prince commanded a more noble or worthy subject; not doubting but by your obedience to my General, by your concord in the camp, and your valour in the field, we shall shortly have a famous victory over these enemies of my God, of my kingdom and of my people.”

Elizabeth I – 1588

Privacy Overview

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth made to commemorate the defeat of the Spanish Armada (1588), depicted in the background. Elizabeth's international power is symbolised by the hand resting on the globe. Woburn Abbey, Bedfordshire.. The Speech to the Troops at Tilbury was delivered on 9 August Old Style (19 August New Style) 1588 by Queen Elizabeth I of England to the land forces earlier ...

The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I. The most famous visual expression of the Spanish Armada is The Armada Portrait of Elizabeth I (c. 1588). Although there are several versions of the painting, each one shows Elizabeth flanked by scenes of the defining acts that thwarted Spain's invasion.

Tilbury Speech. This speech was given by Queen Elizabeth to her troops, fighting the Spanish Armada, on 9 August 1588 at Tilbury in Essex. We have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit our selves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you I do not desire to live to distrust my ...

The Spanish Armada was a large naval fleet sent by Spain in 1588 to invade England. ... Speech to the Troops at Tilbury ... Queen Elizabeth launched a failed "English Armada" against Spain ...

The Tilbury Speech - The Elizabeth Files. The Tilbury Speech. The Tilbury Speech of 1588 was Elizabeth I's most famous speech and was given in August 1588 to the land forces at Tilbury, in Essex, who were preparing to defend England against the Spanish Armada. There are two main versions of the speech:-.

At The History Place - Part of the great speeches series. One of the most powerful women who ever lived was Queen Elizabeth I of England. Elizabeth (1533-1603) was the daughter of King Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, and was known as the Virgin Queen or Good Queen Bess. ... Philip assembled a huge fleet of warships known as the Spanish Armada and ...

Speech to the Troops at Tilbury - Aug. 19, 1588. The 1500s saw a major rivalry between Britain and Spain over control of trade in the New World. King Philip II of Spain assembled a fleet of warships known as the Spanish Armada and in 1588 sailed into the English Channel with the goal of invading and conquering England.

Queen Elizabeth I's speech to the troops at Tilbury is among the most famous and iconic speeches in English history. On 9 August 1588, Elizabeth addressed the land forces which had been mobilised at the port of Tilbury in Essex, in preparation for the expected invasion of England by the Spanish Armada.

In the painting below, she is portrayed rallying her troops atop a white horse, every inch the leader of Englishmen and warriors. Queen Elizabeth I at Tilbury, 1588 c.1938. Alfred Kingsley Lawrence (1893-1975) Essex County Council. Elizabeth had done the impossible: defeating the 'invincible' Spanish Armada.

1. Delivered by Elizabeth to the land forces assembled at Tilbury (Essex) to repel the anticipated invasion of the Spanish Armada, 1588. 2. Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester; he was the queen's favorite, once rumored to be her lover. The Norton Anthology of English Literature. 6 th ed. Vol 1. M.

Go here for more about the Spanish Armada. It follows the full text transcript of Elizabeth I's Spanish Armada speech, delivered at Tilbury, Essex, England - 1588. My loving people, we have been persuaded by some that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes for fear of treachery; but, I do assure you ...

In December 1587 Queen Elizabeth I put Lord Howard of Effingham in charge of England's defence against the Spanish Armada. Although not a celebrated sailor like Sir Francis Drake, Effingham was an able commander and had the support of the nobility.He was also known for his willingness to listen to those more experienced, such as Drake, who was appointed his Vice-Admiral.

The Armada launch had been delayed several times, including once because of a raid by the English on Cadiz. The Spanish Armada was a fleet of 130 ships, and it first left the port of Coruna in August 1588, under the Duke of Medina Sidonia, the most powerful noble in Spain. The fleet was ordered to sail to the English Channel and transport a large army in Flanders into England.

The second version of the Tilbury Speech is one recorded in 1612 by William Leigh, in his sermon "Quene Elizabeth, Paraleld in Her Princely Vertues", where he described Elizabeth appearing before her troops "with God in her heart, and a commaunding staffe in her hand" and saying the following:-. "Come on now, my companions at arms ...

The Spanish Armada received the blessing of the Church on April 25, 1588, and set sail over the next two days from Spanish ports bound for the shores of England. ... In a speech to the men, she urged them to take heart and fight alongside her, but the Spanish did not come. The armada feared renewed attacks by the Royal Navy and how a loss would ...

Scene from Elizabeth the Golden Age movie. Queen Elizabeth 1 (Cate Blanchett) gave inspiring speech to British Troops in Tilbury, before fight with Spanish A...

Spanish Armada, the great fleet sent by King Philip II of Spain in 1588 to invade England in conjunction with a Spanish army from Flanders.England's attempts to repel this fleet involved the first naval battles to be fought entirely with heavy guns, and the failure of Spain's enterprise saved England and the Netherlands from possible absorption into the Spanish empire.

England's greatest Queen gives her most well-known speech, as her nation faces utter disaster with the approach of the Spanish Armada. Elizabeth I, Against the Spanish Armada, 1588 My loving people, we have been persuaded by some, that are careful of our safety, to take heed how we commit ourselves to armed multitudes, for fear of treachery; but I assure you, I do not desire to live to ...

The Spanish Armada (often known as Invincible Armada, or the Enterprise of England, Spanish: Grande y Felicísima Armada, lit. 'Great and Most Fortunate Navy') was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by Alonso de Guzmán, Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aristocrat without previous naval experience appointed by Philip ...

Queen Elizabeth I Speech - Spanish Armada. Queen Elizabeth I speech to her troops facing the Spanish Armada in 1588. Elizabeth I addresses her troops at Tilbury in the county of Essex in England on the eve of battle with the Spanish Armada in 1588. England won the battle and defeated the Spanish attempts to take the country. Speech

The great Armada was first sighted on July 19, 1588. At midnight on July 28, the English army filled warships with pitch, brimstone, gunpowder and tar before setting them alight and casting them towards the Spanish ships anchored off Calais. In the confusion, a large number of the fleet cut their anchor cables and were dispersed.

Queen Elizabeth's speech to the troops at tilbury; https://docs.google.com/document/d/1ptEfp2yYGwa5e1pvfR_eT6_o7EEUTvkElDRAY8c9q48/edit?usp=sharing