Movie Reviews

Tv/streaming, collections, great movies, chaz's journal, contributors.

Now streaming on:

In a perfect world, “Selma” would exist solely as a depiction of darker days long since past, an American history lesson that concludes with reassurances that its horrors will no longer be perpetrated, tolerated nor celebrated. Alas, perfection eludes us on this mortal, earthly plane; “Selma” shows the evolution of change while beaming a spotlight on the stunted growth of that which has not changed. Its timeliness is a spine-chilling reminder that those who do not know their history are doomed to repeat it. Its story provides a blueprint not only of the past, but of the way forward.

There’s a reason why Ava DuVernay ’s film is called “Selma” and not “King”. Like Spielberg’s “ Lincoln ”, “Selma” is as much about the procedures of political maneuvering, in-fighting and bargaining as it is about the chief orchestrator of the resulting deals. “Selma” affords Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. the same human characteristics of humor, frustration and exhaustion that “Lincoln” provided its President. This relatable humanity elevates King’s actions and his efforts. It inspires by suggesting that the reverence for Dr. King was bestowed on a person no different than any of us. If he can provoke change, we have no excuse not to as well.

As King, David Oyelowo is a revelation. Like Anthony Hopkins in “ Nixon ”, he channels the essence of his character rather than a dead-on visual interpretation. In recreating King’s speaking voice, Oyelowo resists the preacherly curlicues one might be inclined to use based on hearing King’s speeches. Like any good pastor, Oyelowo saves those cadences for his speech scenes, the last of which is so stirring and powerful it knocks the air out of your lungs. Oyelowo channels a conflicted King, a tired man with the weight of the movement on his shoulders, then merges that with defiance, humor, strength and strategic expertise. In Oyelowo’s excellent performance, King becomes a complex, flawed man whose faith in God kept him from utter despair.

Known for her superb indie dramas “ I Will Follow ” and “ Middle of Nowhere ”, DuVernay has proven herself a master of small, intimate moments. “Selma” never loses focus on the interpersonal dynamics between King and his followers, his detractors and his family. While touching base with details on SNCC, the SCLC and the organization of the Selma to Montgomery Marches, DuVernay gives memorable scenes to a wide variety of character actors in real-life roles. Andre Holland ’s Andrew Young , Stephan James ’ John Lewis , Colman Domingo ’s Rev. Abernathy and Common’s James Bevel stand out, but eagle-eyed viewers will also notice “ Dear White People ”’s Tessa Thompson , Cuba Gooding, Jr., Martin Sheen and Wendell Pierce . Even comedian Niecy Nash shows up as a gracious, funny host who invites King and his cohorts into her home.

“Selma” continues DuVernay’s exploration of female empowerment by devoting time to King’s marriage to Coretta Scott King (a powerful Carmen Ejogo ). We’re reminded that the movement is as hard on her as it is for her husband, especially since she is home with the kids and the constant victim of harassment from citizens and the government. In one of the film’s best scenes, King is asked a very hard question by his wife. The actors and the director take their time here, with Oyelowo and Ejogo silently and masterfully working the uncomfortable pause between question and answer. In another very good scene, Coretta Scott King meets with Malcolm X (a convincing Nigel Thatch), and their dialogue is an informative piece of strategizing.

In addition to reminding us how good she is with drama, DuVernay puts Hollywood on notice by mastering huge sequences heretofore unseen in her work. Her staging of “Bloody Sunday” on the Edmund Pettis bridge is a spectacular mini-movie that could stand on its own as a short. Narrated by a journalist calling in the story, the scene takes on documentarian proportions. With this scene, and her horrific staging of the 16 th Street Baptist Church bombing, DuVernay and her editor Spencer Averick make you feel the intensity and chaotic terror of the violence. Dozens of kneeling, peaceful protests fill the screen end to end, and the juxtaposition between the historical depiction on the movie screen and the current images on today’s TV screens does not go unnoticed.

During the fight for voter rights, King has several meetings with President Johnson (a jarring but effective Tom Wilkinson ). Their scenes, and Johnson’s scenes with J. Edgar Hoover ( Dylan Baker ) focus on the political gamesmanship required to bring about change. “Selma” points out the media’s role in influencing the hearts and minds of the American people, and how easily that can be manipulated. King knows about this media power, and how his team handles it is a precursor to today’s social media shenanigans.

The prescient timing of “Selma” could not have been planned. Its opening scene is a casual reminder of what life was like before the Voting Rights Act, with poll taxes and absurd literacy tests suppressing the Black vote. Miss Sofia herself, producer Oprah Winfrey , shows up in the opening scene as a woman on her fourth journey to the voting bureau to take the test that will give her a right she already had. Winfrey disappears into an ordinary person’s countenance, and her gradual disappointment as she realizes once again she will be denied is both heartbreaking and a warning.

“Selma” works as both an epic and a small scale drama, and credit must be extended to DuVernay’s longtime cinematographer, Bradford Young . Young’s camera loves Black skin, and he lights it in beautiful, fearless, shadowy Gordon Willis flourishes the likes of which I have not seen in Hollywood cinema. His stylistic touches during the action scenes are startling and original. That there hasn’t been more talk about his work (he also shot “Ain’t Them Bodies Saints”) is something of a travesty that “Selma” should correct.

This is an emotional movie that aims to anger, sadden and inspire viewers, sometimes in the same scene. “Selma” takes no prisoners and, while it welcomes moviegoers of all hues, it has no intention of sugarcoating its horrors for politically correct comforting. This film—one of the year’s best—is an announcement of a major talent in Ms. DuVernay, but its core message will not be lost nor hidden by the accolades it receives. Through the noise, “Selma” speaks to us: From the top of the hill of progress, it is just as easy to slide down backwards as it is to move forward. Attention must be paid.

Odie Henderson

Odie "Odienator" Henderson has spent over 33 years working in Information Technology. He runs the blogs Big Media Vandalism and Tales of Odienary Madness. Read his answers to our Movie Love Questionnaire here .

Now playing

Force of Nature: The Dry 2

Sheila o'malley.

Matt Zoller Seitz

The First Omen

Tomris laffly.

A Bit of Light

Peyton robinson.

Boy Kills World

Simon abrams.

Gasoline Rainbow

Film credits.

Selma (2014)

Rated PG-13 for disturbing thematic material including violence, a suggestive moment, and brief strong language

127 minutes

David Oyelowo as Martin Luther King

Tom Wilkinson as Lyndon Baines Johnson

Carmen Ejogo as Coretta Scott King

Andre Holland as Andrew Young

Omar J. Dorsey as James Orange

Alessandro Nivola as John Doar

Giovanni Ribisi as Lee White

Colman Domingo as Ralph Abernathy

Oprah Winfrey as Annie Lee Cooper

Common as James Bevel

Keith Stanfield as Jimmie Lee Jackson

- Ava DuVernay

Latest blog posts

Cannes 2024: Megalopolis, Bird, The Damned, Meeting with Pol Pot

Prime Video's Outer Range Opens Up in a Hole New Way in Season 2

The Ebert Fellows Go to Ebertfest 2024

Cannes 2024 Video #2: The Festival Takes Off

- Cast & crew

- User reviews

- A chronicle of Dr. Martin Luther King , Jr.'s campaign to secure equal voting rights via an epic march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1965.

- The unforgettable true story chronicles the tumultuous three-month period in 1965, when Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. led a dangerous campaign to secure equal voting rights in the face of violent opposition. The epic march from Selma to Montgomery culminated in President Johnson signing the Voting Rights Act of 1965, one of the most significant victories for the civil rights movement. Director Ava DuVernay's "Selma" tells the story of how the revered leader and visionary Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr and his brothers and sisters in the movement prompted change that forever altered history. — Miss W J Mcdermott

- Alabama, 1965. While black citizens of Alabama constitutionally have the same voting rights as whites, they are hamstrung by racist local registration officers, politicians and lawmen. Dr Martin Luther King and his followers go to Selma, Alabama to attempt to achieve, through non-violent protest, equal voting rights and abilities for black people. — grantss

- In 1964, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) accepts his Nobel Peace Prize. Four black girls walking down stairs in the Birmingham, Alabama 16th Street Baptist Church are killed by a bomb set by the Ku Klux Klan. Annie Lee Cooper attempts to register to vote in Selma, Alabama but is prevented by the white registrar. King meets with Lyndon B. Johnson and asks for federal legislation to allow black citizens to register to vote unencumbered, but the president responds that, although he understands Dr. King's concerns, he has more important projects. King travels to Selma with Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, James Orange, and Diane Nash. James Bevel greets them, and other SCLC activists appear. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover tells Johnson that King is a problem, and suggests they disrupt his marriage. Coretta Scott King has concerns about her husband's upcoming work in Selma. King calls singer Mahalia Jackson to inspire him with a song. King, other SCLC leaders, and black Selma residents march to the registration office to register. After a confrontation in front of the courthouse, a shoving match occurs as the police go into the crowd. Cooper fights back, knocking Sheriff Jim Clark to the ground, leading to the arrest of Cooper, King, and others..

- A chronicle of Martin Luther King's (Oyelowo) campaign to secure equal voting rights via an epic march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama in 1965, forcing a famous statement by President Lyndon B. Johnson (Wilkinson) that ultimately led to the signing of the Voting Rights Act.

- In 1964 Dr. Martin Luther King (David Oyelowo), Jr. accepts his Nobel Peace Prize. Four African American girls are shown walking down the stairs of the 16th Street Baptist Church, talking. An explosion goes off, killing all four girls and injuring others. In Selma, Alabama, Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey) attempts to register to vote but is prevented by the white registrar. King meets with President Lyndon B. Johnson and asks for federal legislation to allow African American citizens to register to vote unencumbered. Johnson says he has more important projects. King says that the right to vote is important because for decades African American's have been systematically prosecuted & hunted by whites in a still segregated South. The white criminals are never apprehended by white officials chosen by an all-white electorate, & in the rare occasion they go to trial, they are freed by an all-white jury, as you can't serve on the jury unless you have the right to vote. President Jhonson wants King on his side as he does not want the African American civil rights movement going back to its extremists roots under Malcolm X. King travels to Selma with Ralph Abernathy, Andrew Young, James Orange, and Diane Nash. Selma is an Alabama town & heart of the anti-African American sentiment in the south. King checks into a hotel that bars African Americans. James Bevel greets them, and other SCLC activists appear. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover tells Johnson that King is a problem, and suggests they disrupt his marriage. Coretta Scott King has concerns about her husband's upcoming work in Selma. King calls singer Mahalia Jackson to inspire him with song. King and African American Selma residents march to the registration office to register. After a confrontation in front of the courthouse a shoving match occurs as the police go into the crowd. Cooper fights back, knocking Sheriff Jim Clark to the ground, leading to the arrest of Cooper, King, and others. Alabama Governor George Wallace speaks out against the movement. Coretta meets with Malcolm X who says he will drive whites to ally with King by advocating a more extreme position. Malcolm & King never saw eye to eye as King was a proponent of non-violence, while Malcolm wanted to raise a African American army to fight for African American rights Wallace and Al Lingo (state police sheriff) decide to use force at an upcoming night march in Marion, Alabama, using state troopers to assault the marchers. A group of protesters runs into a restaurant to hide, but troopers rush in to beat and shoot Jimmie Lee Jackson. King and Bevel meet with Cager Lee, Jackson's grandfather, at the morgue. King speaks to ask people to continue to fight for their rights. The Kings receive threats to their children, and King is criticized by members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). As the Selma to Montgomery march is about to begin, King talks to Young about canceling it, but Young convinces King to persevere. The marchers, including John Lewis of SNCC, Hosea Williams of SCLC, and Selma activist Amelia Boynton, cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge and approach a line of state troopers who put on gas masks, and then attack with clubs, horses, tear gas and other weapons. Lewis and Boynton are among those badly injured. The attack is shown on national television as the wounded are treated at the movement's headquarter church. Movement attorney Fred Gray asks federal Judge Frank Minis Johnson to let the march go forward. President Johnson demands that King and Wallace stop their actions and sends John Doar to convince King to postpone the next march. White Americans, including Viola Liuzzo and James Reeb, arrive to join the second march. Marchers cross the bridge again and see the state troopers lined up, but the troopers turn aside to let them pass. King, after praying, leads the group away, and comes under sharp criticism from SNCC activists. That evening Reeb is beaten by two white men on the street, and King is told of his death. Judge Johnson allows the march. President Johnson speaks before a Joint Session of Congress to ask for quick passage of a bill to eliminate restrictions on voting, praises the courage of the activists, and proclaims in his speech "We shall overcome". The march on the highway to Montgomery takes place, and when the marchers reach Montgomery King delivers a speech on the steps of the State Capitol. King concludes by saying that equality for African Americans is approaching.

Contribute to this page

- See more gaps

- Learn more about contributing

More from this title

More to explore.

Recently viewed

59 Selma (2014)

Marching toward justice in selma.

By Anonymous

Ava DuVernay’s Selma is a complex film mired in conflict and history. At its heart is the campaign to secure full voting rights for African Americans with the march from Selma to Montgomery serving as its nexus. I choose this film for its historical consistency and compelling performances. Selma is able to draw from history and show the internal conflict within the civil rights movement in 1964-1965. Martin Luther King (David Oyelowo) is the main protagonist though it also stresses the importance of the collective and highlights other important figures too.

The civil rights movement in America is long and amorphous; however, Selma ‘s story starts at Dr. King’s Nobel prize ceremony for his work in civil rights. The film makes an earnest effort to humanize the legends of history surrounding the civil rights movement between 1964-65. Before Dr. King’s speech, he is distracted by his ascot, and during it, he is reminded of the past events that compel him. Selma immediately has us looking backward to help orient us in history, provide a sense of scope and give an idea of what motivates Martin Luther King. Dr. King begins his speech at the esteemed ceremony in well-lit room filled with dignitaries and elites.

“I accept this honor for our lost ones, whose deaths pave our path, and for the more than twenty million American Negroes” …the scene fades.

We flashback to a sunlit church in Birmingham Alabama. Four little girls chatter while walking down the church steps and past ornate stained glass on their way to service. As the frame focuses on one girl, mid-sentence an explosion interrupts her. The totality of the tragedy is revealed as the motionless children lay buried in rubble. A reminder of the radical discrimination that left no place safe for people of color. The Birmingham bombing took place the year prior, September 15, 1963 (Parrott-Sheffer, C., n.d.). King described it as “one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity.”

Title I of the 1964 Civil Rights Rct granted equal voting rights to people but had some critical flaws. In the courthouse in Selma, Alabama, where Annie Cooper (Oprah Winfrey) slowly and quietly fills out her voter registration in anticipation of exercising her newly given right. Downtrodden, she approaches the clerk’s booth. The close-up exchange of expressions conveys the causality and mutual understanding of the racism of the time. The everyday racism of the clerk alludes to the power dynamic, they both know Annie is eligible to register, but they also know she is powerless. Inevitably we arrive at a close-up of “DENIED” stamped across her registration as sad music shuffles Annie away, looking down at her feet, crushed. A straightforward example of the shortcomings of the civil rights act. It showcases the imbalance of power despite the law and contextualizes Cooper’s link to the struggle.

The Civil Rights Act is only six months old, and Martin Luther King has come to discuss voting rights again. They exchange pleasantries before sitting down to discuss matters of the nation, and the tone changes. The President asks, “How can help?” Dr. King asks for the fulfillment of voting rights for African Americans. President Johnson points out that African Americans had the right to vote through the 1964 civil rights act. King explains the flagrant denial of voting rights in the South. President Johnson tries to pivot priorities to the war on poverty as he towers over King and pats him on the back. King’s face scrunched with frustration but remains composed, explaining the gaps in enforcement in the South. He also points out that registering to vote is a prerequisite for serving on a jury, further contributing to inequalities in the system. King requests a federal law that guarantees the right to vote without restriction and robust enforcement of the law. President Johnson tries to postpone any further action for now.

This scene is crucial to the movie. The Birmingham bombers escaped conviction, likely due to a lack of enforcement and African American jurors. (Parrott-Sheffer, C., n.d.) The scene also incorporates Annie Cooper’s story into the movie by showing how easy it was to deny her vote and what little recourse she had to refute the decision. Additionally, it lays out the contrast between King and Johnson, who could not be more different in background and perception. This is also where things start to get tricky.

Martin Luther King is a legendary civil rights leader and humanitarian. He also had his issues; adultery among one. However, President Johnson has even more mixed and colorful history. He is on record, having used the n-word multiple times. As a senator, he opposed every civil rights measure, over 20 in total. President Johnson knew of the FBI’s wiretap on Martin Luther King and received regular updates (Conversation WH6707-01-12005, Presidential Recordings Digital Edition):

From December 1963 until his death in 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was the target of an intensive campaign by the Federal Bureau of Investigation to “neutralize” him as an effective civil rights leader. (Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities pg. 81)

The program was funded and continued for years on the assumption that Dr. King’s or his advisors were secret communists through the program never produced any evidence. The program continued years after his advisor quit and broke ties.

We have seen no evidence establishing that either of those Advisers attempted to exploit the civil rights movement to carry out the plans of the Communist Party. (Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities pg. 85)

President Johnson also passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and later the voting rights act of 1965. He waged war on poverty, reformed healthcare, and increased federal funding for education. DuVernay’s depiction of President Johnson was consistent with historical text. The director of the FBI was able to falsely convince him that there was a chance that Dr. King had secret communist ties. Martin Luther King was a keystone player in the civil rights movement. Without him there it was no unifying strategy or pressure to change. But President Johnson is the actual agent of change, and that is due to his position foremost, but ultimately his openness to being persuaded to do something he doesn’t initially understand or want to do. Johnson has a character arc that lands him in a good place, and it is hard not to see him as a flawed hero by the end of the film. A march on Selma wouldn’t make sense if Martin Luther King and President Johnson were on the same page at that time. Selma (2014) offers a reasonable and logical course between these events.

No one is spared in the telling of Selma . What I covered only accounts for the first ten minutes of this two-hour film, but those minutes are crucial. Selma shows the civil rights movement was not just a unifying of America, but a hard-fought battle among a fractured America for its future. Selma is not an easy movie to watch, but it does reward patience and understanding. It illustrates how easy it was to subvert the civil rights act of 1964 and how it served to placate white Americans. I appreciate how much care was put into explicitly speaking to the principle of the issues and showing real-world examples played out. It does a great job of outlining the strategies that overcame deep and powerful racism in America. Most of all, it makes a solid case on how the march on Selma was instrumental in the civil rights movement.

“Is Selma Historically Accurate?” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 12 Feb. 2015, www.theguardian.com/film/2015/feb/12/reel-history-selma-film-historically-accurate-martin-luther-king-lyndon-johnson.

Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library. “Selma” movie. Accessed Wed. 25 Aug 2021. http://www.lbjlibrary.org/press/selma-movie.

“Lyndon B. Johnson and J. Edgar Hoover on 25 July 1967,” Conversation WH6707-01-12005, Presidential Recordings Digital Edition [Lyndon B. Johnson and Civil Rights, vol. 2, ed. Kent B. Germany] (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2014–). URL: http://prde.upress.virginia.edu/conversations/4005335

Martin Luther King Jr. – Acceptance Speech. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2021. Wed. 25 Aug 2021. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/peace/1964/king/acceptance-speech/

Parrott-Sheffer, C. (n.d.). 16Th Street Baptist Church bombing. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/event/16th-Street-Baptist-Church-bombing

Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. Supplementary Detailed Staff Reports on Intelligence Activities and the Rights of Americas: Book III. Report No. 94-755. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1976. (https://archive.org/details/finalreportofsel03unit)

Difference, Power, and Discrimination in Film and Media: Student Essays Copyright © by Students at Linn-Benton Community College is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Issue Archive

- Stay Connected

Deep Focus: Selma

By Michael Sragow on December 29, 2014

Selma begins with the camera squarely framing Martin Luther King Jr. (David Oyelowo), as if for a formal portrait. The immediate effect is ironic. He’s rehearsing a solemn line for an award speech, and he’s unhappy about something , which turns out to be his tie—or, rather, his “ascot,” as his wife, Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo), calls it. She adjusts the neckwear. King complains about feeling ill at ease in such a swanky getup. When he spins out his blue-sky ideal about taking a calm job as a minister in a college town, Coretta looks pleased and then wistful, as if her husband has pulled this nostalgic number on her once too often. The director, Ava DuVernay, cuts to the dais at a grand occasion, and King accepts the 1964 Nobel Prize for Peace.

With this opening vignette, DuVernay ( Middle of Nowhere ) and the credited screenwriter, Paul Webb, mean to signal audiences that we’re in for an intimate, maybe irreverent look at the world-changing figure whose nonviolent campaigns against institutional racism propelled America’s boldest civil-rights advances of the 20th century. But even if you know nothing about King, both the cute business with the ascot and the dreamy escapism about a quieter life are too wispy to introduce this complex character. They’re like anecdotes about the human side of Great Men that educators employ to make biographies “relatable.” If you do know something about King, this Nobel Prize moment is inadequate.

At that time, the real King was depressed for many troubling reasons: rifts between King’s longtime partner in the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, Ralph Abernathy (Colman Domingo), and other members of the SCLC; scandalous behavior among members of King’s entourage in Oslo; bogus FBI-spread rumors about his mismanagement of funds and links to Communism as well as the agency’s hyperbolic gossip about his extramarital affairs; frustration that 19 white Mississippians accused of murdering civil rights workers James Chaney, Michael Schwerner, and Andrew Goodman had been released from prison (briefly, it turned out); and apprehension over the violence he rightly thought would erupt in Selma as soon as he started marching there for voting rights.

It’s understandable that DuVernay would make a priority of avoiding excessive detail. But too much of the movie is like that opening: deliberate, broad, uninspired. Selma is nothing if not ambitious. DuVernay aims to evoke the urgency behind King’s goal to enfranchise Southern blacks—that’s why she interrupts her chronology to depict the church bombing in Birmingham that killed four little girls in 1963. (She envisions them chattering, pre-explosion, about Coretta Scott King’s hairstyle.) And she seeks to emphasize the grounded political wisdom behind the high-flying rhetoric of King’s nonviolent protest. When King arrives in Selma and confronts the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), his youthful competition, he states three principles of protest: “Negotiate, demonstrate, resist.” He explains that raising white America’s consciousness is as crucial as organizing black communities. King’s marches provoke racists to behave badly so national media will take notice. DuVernay lays that much out clearly. But when his legions proceed to the courthouse, the awful spectacle of Southern white lawmen brutalizing righteous citizens overpowers the film’s attempt to engage viewers more deeply. DuVernay’s scenes of street atrocities achieve a dogged power, but her rendering of King’s character fails to provide a counterweight to all the carnage. With police batons thudding against flesh and bone, and almost surreal images like a mounted posse-man in a cowboy hat lashing men and women of all ages, the movie captures horrific challenges to civil disobedience. But it doesn’t clarify King’s own complicated responses to events.

What is King thinking when he sees Annie Lee Cooper (Oprah Winfrey), outraged by the sheriff’s manhandling of an elderly gentleman, wallop him with her handbag, inciting a violent takedown? No matter how intensely Oyelowo grimaces, you can’t read what’s going on in King’s mind. While the moves and countermoves on the street spiral into a destructive dance, King strives to control his own political dance with grassroots political groups on his left (SNCC) and reactionary public figures on his right, like Sheriff Jim Clark (Tim Houston) and Governor George Wallace (Tim Roth). How did King maintain his balance, ethically and tactically? (Even The New York Times once declared: “Non-violence that deliberately provokes violence is a logical contradiction.”) You can appreciate the sincerity of DuVernay’s work and still regret her lack of nimbleness and her psychological opacity. She awkwardly focuses on the same abused marchers in each busted-up demonstration. Watching this movie is like reading a large-type edition of a long and workmanlike biography.

The key politician in King’s sights is President Lyndon B. Johnson (Tom Wilkinson). One of the film’s major disappointments is its failure to imbue LBJ with a scale or fascination equal to his towering domestic accomplishments and imposing wheeler-dealer personality. The script depicts him simply as a beleaguered Chief Executive who stubbornly sticks to his own timetable. Having signed the milestone Civil Rights Act of 1964, the president tells King that his first priority is waging the War on Poverty to benefit impoverished blacks and whites alike, no matter what the facts are on the ground in Selma. He agrees that the federal government should guarantee the right of blacks and other minorities to vote, forcing the ban of prohibitive poll taxes and bogus literacy tests. But he thinks that pushing this issue soon after the civil rights bill would jeopardize his anti-poverty crusade. In the movie, he resents King so much for hectoring him that he gives his consent to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s extortionist tactics, which include recording King’s infidelities and mailing a damning sex audiotape to his home. DuVernay’s clever use of printed legends from FBI logs help her set the time and place of crucial scenes and maintain a modicum of suspense. (Dylan Baker plays Hoover as an albino snake.) The film barely acknowledges the genuine anguish Johnson was suffering over U.S. policy in Southeast Asia—a serious omission, since the first U.S. combat division reached Vietnam on the very same day as the first aborted march from Selma-to-Montgomery. In this movie, the president finally gives King exactly what he wants because he doesn’t want to be seen as a small-minded cracker like Roth’s George Wallace. A more generous view of events would suggest that Johnson welcomed the pressure King put on him to do what he knew was right all along. Selma gives King and only King the moral high ground.

Often a first-class actor, Wilkinson fails to summon an iota of LBJ’s sloppy energy. Instead, he acts like a man in a perpetual snit, until the president gives his stirring plea to Congress to pass the Voting Rights Act. Even then, the way DuVernay sets up the action and the way Wilkinson plays it, when LBJ says “We shall overcome,” he sends a message of reconciliation specifically to King. It’s a reductive interpretation. Johnson was talking to King, but he was also, in a rare feat of eloquence, addressing the better angels of each American’s nature. He had used every hustle in his arsenal to advance a progressive domestic agenda. For Johnson and for the country, that occasion was cathartic.

In the greatest speech of a dreary public speaker, was Johnson trying to rise to the level of Martin Luther King Jr.? The civil rights leader, of course, was a magnificent orator. The film’s chief pleasure is hearing Oyelowo deliver roof-rattling variations on the preacher/activist’s call-and-response style. King had the podium artistry to inject adrenaline into gravitas. When seized by the moment, he entered a zone that was at once spiritual and sensual. Oyelowo emphasizes the visionary roll of King’s distinctive cadence, then adds his own startling staccato punctuation. His achievement is all the more impressive since the words he speaks are not King’s. DuVernay wrote the speeches herself, to bypass copyrighted material. Her pastiches lack the sinewy religious texture of King’s own writing, but their sleekness allows Oyelowo to connect with youthful, secular audiences who’ve never read the King James Bible. It’s when King descends from the lectern that Oyelowo gets into trouble. He’s praised his director for letting him take an extra second or two in playing out a scene, but his conversations often unfold in the same tempo as his sermons and stem-winders, especially when King is with Coretta. Did he actually speak this sagely and ceremoniously at home?

The script for Selma suffers from naming emotions rather than conjuring them and from invoking ideas rather than dramatizing them. In what should be the movie’s boldest domestic scene, Coretta and King listen to an audiotape that’s allegedly of him making love to another woman. But all Coretta wants to know is whether King honestly loves her—and whether he loves any of “the others.” Should these be the sole questions? Despite Oyelowo’s array of facial contortions and Ejogo’s haunting, tremulous elegance as Coretta, the movie leaves you with only the most general notion imaginable of King’s marital guilt. Selma acknowledges King’s infidelity without suggesting how it fit into his temperament or affected his marriage.

The movie is even more evasive about the most intriguing and under-chronicled episode in the Selma voting-rights campaign: King’s decision to curtail the second try at a march to Montgomery. He retreated from state troopers at the Edmund Pettus Bridge, the site of the town’s “Bloody Sunday” two days earlier, after lawmen broke up their battle line and cleared a way for the marchers. King kneels in prayer before turning back. Is he looking for direction from God? According to King biographer and civil rights historian Taylor Branch (in At Canaan’s Edge ), King had been reluctant to flout a federal court order prohibiting a Selma to Montgomery march. Now “King stood stunned at the divide, with but an instant to decide whether this was a trap or a miraculous parting of the Red Sea. If he stepped ahead, the thrill of heroic redemption for Bloody Sunday could give way to any number of reversals—arrests, attacks, laughingstock exhaustion in hostile country—all with marchers compromised as flagrant transgressors of the federal order. If he stepped back, he could lose or divide the movement under a cloud of timidity. If he hesitated or failed, at least some of the marchers would surge through the corridor of blue uniforms toward their goal. ‘We will go back to the church now!’ shouted King, turning around.” Another biographer, David J. Garrow, says that King had cut a deal with one of LBJ’s emissaries to stop until the march was cleared in federal court. The movie, by contrast, shies away from practical explanations and leaves King’s oddest move in a haze. King turns around and walks slowly back, amid his puzzled, angry flock.

The supporting actors bring oomph to their small roles and are dead ringers for their historical counterparts. They include Andre Holland as Andrew Young, Wendell Pierce as Hosea Williams, Common as James Bevel, Ruben Santiago-Hudson as Bayard Rustin, and Stephan James as young John Lewis. Along with Oyelowo, and Domingo as Abernathy, they imbue the whole ensemble with comradely warmth and solidity. It’s hard to resist this cast’s portrayal of idealism in action, or to feel any distance from the characters’ pain as truncheons scar their flesh. They act with the vitality of performers caught up in what Branch calls “Selma’s unique collaboration between a citizen’s movement and elected government.” This particular triumph was to win blacks their voting rights while setting an example of focused, disciplined protest. Its tragedy is that this inspiring episode can still be called “unique.”

The Film Comment Podcast: Cannes 2024 #3

The Film Comment Podcast: Cannes 2024 #2

The Film Comment Podcast: Cannes 2024 #1

The Film Comment Podcast: Writing About Avant-Garde Cinema

Sign up for the Film Comment Letter!

Thoughtful, original film criticism delivered straight to your inbox each week. Enter your email address below to subscribe.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Selma review – handsome civil rights drama with topical resonance

David Oyelowo plays Martin Luther King with poise and charisma but the glow of prestige myth-making overwhelms the personal

J ust as it dramatises Martin Luther King’s momentous marches to the Alabama town of the title, so this stately civil rights movie begins its own march into the awards season with a spring in its step. Unimpeachably important, ambitious in its scope and handsomely presented, it has all the hallmarks of a trophy winner, for better and worse.

Selma wisely bites off no more than it needs to. Its focus is King in 1965, when he had given his “I have a dream” speech and received the Nobel peace prize, but was still frustrated by the lack of genuine progress on civil rights.

Selma became the flashpoint for the next battle – the right of African-Americans to vote freely – and the greatest strength of Ava DuVernay’s movie is in detailing how strategic King’s leadership was, and how non-violent protest was most effective when it was met with violence. Selma was selected as the battleground precisely on account of its brutal law enforcement and racist governor, George Wallace (Tim Roth somehow fits the role perfectly), all the better to generate newsworthy clashes and thus communicate the struggle to the American people, and ultimately to the White House.

Of course, the desired clashes arise – over the course of three tense and brutal protest marches that make for arresting setpieces. But more often this is a story of backroom deals and political compromises, as King negotiates with a recalcitrant Lyndon Johnson (Tom Wilkinson), other civil rights factions, and his conflicted wife Coretta.

There’s so much behind-the-scenes dealmaking going on, it often feels like we’re missing out on the scenes themselves. Perhaps mindful that King’s legendary gift for oratory would eclipse most scriptwriters’ efforts, Selma uses it sparingly, and gives equal time to quiet moments of doubt, regret and reflection. British actor David Oyelowo handles both registers with great poise. He gives the role admirable subtlety, confidence and charisma, and when he gets the chance to build up a head of steam at a lectern, the movie lifts with him.

The trouble is, that swelling oratory mode tends to creep into scenes where it doesn’t really belong. All too often in Selma’s quiet, intimate moments, strings and piano music start to swell on the soundtrack, dialogue gives way to extended, grandstanding monologue, and suddenly we’re thinking, “this’ll make a great clip for the awards campaign”. Perhaps that’s the price of handling big, important episodes of history: it’s almost impossible to take risks or put a personal stamp on them. There’s too much to honour and do justice to.

As a result, the movie becomes infused with that creamy glow of prestige myth-making. Everyone looks dressed in their Sunday best, and there’s no sense of the mud, rain and hardship the real Selma marches entailed. We often see King in church, backed by stained-glass windows, as if in admission that this isn’t the unvarnished truth; it’s the gospel.

It’s no great spoiler to reveal that the movie closes with a rousing King victory speech, on the steps of the Alabama State Capitol, in which he reassures his audience that “our freedom will soon be upon us”.

You could argue that Barack Obama’s election delivered that promise, but events such as the police shootings of Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin cast the victory of Selma in a somewhat ironic light. King’s initial complaint that Alabama was 50% black but that only 2% of them were allowed to vote has curious parallels with modern-day Ferguson, Missouri, with its predominantly black population and predominantly white police force. Perhaps there’s no better time for a reminder of the power of non-violent protest, but Selma also provides a potentially dangerous reassurance that the battle has already been won.

- Civil rights movement

- Martin Luther King

- Tom Wilkinson

Comments (…)

Most viewed.

Find anything you save across the site in your account

The Crucial Lessons of Democracy in “Selma”

By Richard Brody

Movies about media are special because movies are media, so these movies reveal much about the way their directors think about their art—and about its place in the world. That’s one reason why “Selma” is a distinctive political film. No less than an inside-Hollywood drama or a backstage musical, “Selma” tears away the curtain on the making of images—indeed, some of the most important images in American history. The movie tells the story of how these images were made, and shows the colossal sacrifices endured in the effort to make them. It’s a movie about history and the creation of history—and, in the process, it takes its own place in history. That built-in historicity is essential to the movie. It exemplifies what’s best in “Selma” while also revealing the limits of its effectiveness.

The movie’s essential subject is voting rights—the obstacles placed by Southern states to black people registering to vote—and the effort by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., (played majestically by David Oyelowo) to persuade President Lyndon Baines Johnson (Tom Wilkinson) to push for a law eliminating barriers to voter registration and granting the federal government oversight of election laws in states and localities that had practiced discrimination.

The story is how King overcame Johnson’s hesitations about introducing such legislation: by relying on public protest to put public pressure on the President. As depicted in “Selma,” King was, in effect, producing films—organizing events that would be recorded and photographed, broadcast and published—and his “films,” which is to say, the news images of the protests, were intended to test the conscience of the nation. He anticipated the outcome of that test—the outrage that such images would arouse—because he also anticipated the horrific possibility, even likelihood, that the protests would result in violence against the protesters by the local police (all white).

The movie’s director and (uncredited) co-writer, Ava DuVernay, captures the terrifying and tragic sense of King’s leadership: his understanding that justice would come at the price of the protesters’ sacrifice, and that he, like a military officer, was leading (and even, in his absence, sending) troops into battles from which some would likely not return, or return grievously wounded. DuVernay depicts King as a master of diplomacy as well as of strategy. He not only expertly managed the behind-the-scenes negotiations with Johnson, he also held together his own fractious coalition of civil-rights organizations. In retrospect, the divisions among these organizations seem surprising to recognize, given their shared goals, but one of the crucial stories that “Selma” tells is the dependence of political movements and historical moments on individual leaders, especially King.

In “Selma,” DuVernay shows the seeming infinity of small good decisions—effective interactions, apt gestures, wise words—that sustain a few major great ones. She displays unhesitantly the somewhat unseemly and almost inadmissible principle on which a great person’s ability to make great decisions depends: power. Even the most devoted and modest activists working self-sacrificingly on behalf of a principle can’t get anything done without getting others to do it, and DuVernay shows that King’s leadership depended on the ability to gain the confidence both of the inner circle of competing or coördinating leaders and of the many who, in a practical sense, had little power except collectively, and harkened to him on the basis of admiration and trust.

That’s how the images of history get made—and how, as a result, history itself is made. And that’s also how, in its own way, the making of “Selma” converges with the events depicted in the film. Of course, no violence threatened the filmmakers as they recreated violent events. Lives weren’t on the line in the making of the film, and nothing in it suggests any sort of immodest or vainglorious comparison of a film crew to heroic and epochal activists. But timing is everything; these times are different from 1965 but not different enough—and, in some ways, they are even worse. The mainspring of the film, the subject that sparked the marches in Selma, is voting rights, and though they were granted by law in 1965 they’re once again under assault—precisely at a time when many whites are comfortably satisfied that things have, in fact, decisively changed since the bad old days of Jim Crow.

The year 2014 will go down in history, I think, as a year of new consciousness and new activism in the face of long-unaddressed inequities and injustices. Of course DuVernay couldn’t have foreseen the outrages of Ferguson, Missouri, and New York—the killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner and the justice system’s subsequent failures. But those outrages weren’t the beginning, weren’t isolated incidents, but only the most recent and most prominent of such violent injustices. In filming the events of the mid-nineteen-sixties this year, DuVernay catches the spirit and the mood of today’s times.

DuVernay is a brilliant producer who, working on a surprisingly limited budget and a short shoot schedule, recreates a past era with a full and generous scope. Her ability to catch, embody, and transmit the feel of the time is inseparable from her sense of production. The actor David Oyelowo, in a recent interview , explained that the specifics of the shoot infused the work with the spirit of the events themselves—the use of actual locations, the employment of veterans of the Selma marches in the film, and the use of the original pulpit from which King spoke in Montgomery, about which Oyelowo said,

I was like, “Don’t tell me! I have to actually give the speech. I can’t be dealing with the fact that God just showed up again (laughs).” It wasn’t until after that I was just like, “Oh, my goodness, the pulpit!” I just couldn’t. It’s the exact same one. When that’s going on, you just have to go, “O.K., something else is in charge here. Just stay in pocket and get the thing done.”

DuVernay’s contributions to the screenplay are uncredited, but they’re central to the film. Paul Webb, on whose original script the movie is based, has the contractual right to sole credit , though his script was reportedly centered on Johnson and was significantly rewritten by DuVernay, who is responsible for the film’s fundamental shift of emphasis toward King. In the process, DuVernay, who was unable to secure rights from the King estate to his speeches (they’re held by DreamWorks and Warner Bros. for Steven Spielberg ), wrote astonishingly faithful, albeit entirely original, imitations of his sermons and addresses.

Her writing is trenchant and decisive; it’s also dominant. The film’s best visual invention is centered on text: phrases taken verbatim from F.B.I. surveillance reports, put onscreen as if typed (with the sound of a typewriter added), to establish dates and settings and to apostrophize the action ironically about King and his activities. It’s significant that these most original images are words—ones that are documentary in the literal sense, derived from documents. (As the director Jean-Marie Straub said about the word “documentary,” “Who uses documents? The police!”)

DuVernay is focussed on process as determinedly as Steven Soderbergh, which is why, as in Soderbergh’s films, the drama in “Selma” seems to pivot on small events that occur as if in the corner of the screen. One such moment is a judicial ruling to allow a third march across the bridge—the triumphant one—to take place. Very little screen time is devoted to that judicial battle, but its brisk decisiveness makes for an agonized contrast with the state of things today. As I watched the scene, I mentally footnoted it: were such a case to arise in a Southern circuit of the federal court today, I wonder whether there’s a judge who’d see to the rights of mainly black protesters rather than to those of the authorities.

One of the embedded stories of “Selma” is the division, within both the Democratic and Republican parties, on the issue of civil rights—or, conversely, the alliances of Democrats and Republicans on (alas) both sides of the matter. Some Democrats (such as Hubert Humphrey) had long taken up the fight for equality; others, from the South, were brazen segregationists. Similarly, the Republican Party, the party of Lincoln, had many partisans on the side of civil rights, while its ascendant far-right segment (the Goldwater wing) defended segregation.

As Democrats took the lead on civil-rights legislation and enforcement in the nineteen-sixties, and the G.O.P. tilted decisively right, many Southern whites switched parties. Then, the South was solidly Democratic; now it’s solidly Republican. The result is that the Republican Party has been transformed into something that even the most ardently segregationist Democrats could never have dreamed of achieving—a white people’s party—and that’s the party that composes the current Supreme Court majority and that controls both houses of Congress.

The voting rights that were fought for in the events of “Selma” are today under attack from state governments across the country, in the North as well as the South—whether through simple gerrymandering, the intimidations of stringent voter-I.D. requirements and their vigilante enforcement (which Jane Mayer wrote about in the magazine), or the simple calculated scarcity of polling places, subjecting black voters to disproportionately long waiting times and thus placing impediments to their vote—and even from the grossly disproportionate rate of incarceration, where felony convictions often result in disenfranchisement. Meanwhile, in 2013, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was significantly weakened by the Supreme Court : “Our country has changed,” wrote Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr., in his majority opinion. Yes, it has: not least in the disheartening role now played by the Court on matters of civil rights. It is no longer a reliable guarantor of voting rights .

At a time when protest is once again a spark for reform, it’s worth seeing it in the light of “Selma,” which offers crucial lessons in democracy. First, protest isn’t an exception to, departure from, or repudiation of the political process, it’s a part of the political process. Second, the media aren’t independent of the political process, they’re an inextricable part of it, and the creation of images is a political act. That consciousness informs the making of the film, which as a result takes on the tone of history in the making, and becomes a quasi-official work in itself—a resolutely public set of images about the making of public images.

Oyelowo brings a grand and mighty presence to his performance of King (and, I confess, I heard a little British tang to several of his vowels). He doesn’t have the verve or the swing that Jeffrey Wright brought to the same role in the 2001 TV movie “Boycott,” about the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955-56 subsequent to the arrest of Rosa Parks—but Oyelowo’s sculpted strength is apt to the story that DuVernay tells. Wright plays King in a time of expansiveness, when the civil-rights movement was rising to action and his leadership was first developing. Oyelowo plays him at a moment when triumph and tragedy fuse, when progress remains bound to its heavy price—when he already belonged to the ages.

Ultimately, the text of “Selma” and the film’s subject dominate the movie’s actual images. DuVernay displays more originality and audacity as a producer and screenwriter than she does as a director. The film has little visual inflection to match the spoken rhetoric that she crafts. There’s no framing of the words in action, which is what turns language into an aspect of cinematic style. DuVernay’s great achievement in simply making the film exceeds that of any of its individual images, and I think that the gap is no accident. Daring and original cinematic images tap into the director’s unconscious, escape from the director’s intention, and enter the free-flowing realm of uncontrollable impressions and expressions. They risk misunderstanding and misinterpretation, bare conflicts and contradictions that are at odds with a work's public profile and overt import. But they're the way that movies enter history: they make the difference between a timely and notable event and an enduring work of art.

By signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

By Susan B. Glasser

By Neal Katyal

Advertisement

Supported by

The Director Gap

Making History

- Share full article

By Manohla Dargis

- Dec. 3, 2014

On a swampy afternoon in late June, the director Ava DuVernay stood not far from the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala., that haunted place where, President Lyndon B. Johnson told the country, history and fate met. She was instructing a group of white extras on all the ugly things she wanted them to yell at the several hundred black extras snaking across the bridge, part of a sizable army of cast and crew that had been gathered together for “Selma,” her new movie about the campaign for black voter rights.

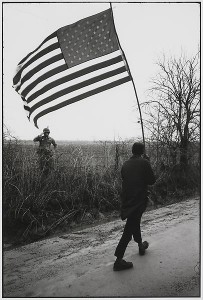

That day, Ms. DuVernay was restaging Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965, when the police violently attacked marchers trying to walk to Montgomery, where they would eventually hear the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s call out to the world: “How long? Not long! Because the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.” A centrifugal force, Ms. DuVernay rarely seemed to stop moving. As she called “Action!,” and people and horses began to run, smoke flooding the air, it was thrilling to witness a female director bring this agonizing American story to life and, in the process, stake her own claim on our cultural history.

Ms. DuVernay, 42, belongs to what she calls “a small sorority” of black female filmmakers, who are part of another modest American sisterhood: female directors of any color. And with “Selma,” she has done what few female directors get the opportunity to do, which is go large — with politics and history — with a decent budget and serious muscle. Paramount Pictures is releasing the movie on Dec. 25, and the producers include Oprah Winfrey, who has a small role in the movie as an activist, and Plan B, Brad Pitt’s company. Four years ago, Kathryn Bigelow became the first woman to win an Academy Award as best director; Ms. DuVernay has a shot to become the second.

Like many, I had hoped Ms. Bigelow’s Oscar for “The Hurt Locker” would be transformative , and that soon female directors would be accepted as equal to men, and, crucially, hired as equals. But that hasn’t happened. In 2009, when “The Hurt Locker” was released, women made up 7 percent of the directors on the top 250 domestic grossing films, according to an annual report by the researcher Martha M. Lauzen. As of early December, by my count, only 19 women — 7.6 percent — were directors on the top 250 grossing features released this year. “Selma” may increase that percentage, as might another big-studio release, Angelina Jolie’s “Unbroken,” about the Olympic runner and war prisoner Louis Zamperini.

It will take more than these two filmmakers to disrupt the industry’s sexism, which has long shut women out from directing movies and, increasingly, shuts them out on screen, too. Notably, Ms. DuVernay and Ms. Jolie, having made movies about women, have now made the leap to bigger stakes with stories centered on men. I hope their movies burn up the box office, but I also hope they return to movies about women. We need those stories, and these days, female directors are often the only ones interested in them. Gender equality is an undeniable imperative. But it’s also essential to the future of the movies: This American art became great with stories about men and women, not just a superhero and some token chick.

Anatomy of a Scene | ‘Selma’

Ava duvernay narrates a sequence from “selma,” featuring david oyelowo and carmen ejogo..

Ms. DuVernay’s path to “Selma” is unusual, not only because she belongs to a small sorority, but also because she came to directing through publicity. After graduating from the University of California, Los Angeles (she majored in English and African-American studies), she had a flirtation with broadcast journalism before landing a publicity job. At 27, she founded her own agency, working on movies by the likes of Steven Spielberg, which embedded her in every stage of the movie process, all the way to award shows. She was on the set of “Collateral” (2004) the moment that she realized what she wanted.

“I just remember standing there in the middle of the night in East L.A. and watching Michael Mann direct and thinking, ‘I have stories,’ ” she said. “That was the moment I thought: ‘Wow, I could do this. I would like to do that.’ ”

She narrated this origin story back home in Los Angeles in September, as we talked in her house, a midcentury perch overlooking Beachwood Canyon with a view of the Hollywood sign. Hours earlier, she had, in the fashion of 21st century cinema, delivered her cut of “Selma” through a high-speed file transfer. Now people whose opinions mattered — including the producers on the Paramount lot a few miles away and the famous one in Chicago (“Ms. Winfrey,” as Ms. DuVernay calls her) — were looking at “Selma” for the first time.

“Your foot is shaking,” I said. “Are you nervous?”

Ms. DuVernay radiates terrific self-confidence, but I assumed that she was anxious. “No,” she shot back.

With its $20 million production budget and the support of a major studio, “Selma” is far bigger than any of Ms. DuVernay’s previous movies. She made her last one, “Middle of Nowhere,” for $200,000. A small-scale, lapidary drama about a woman finding love, though mostly herself, it was beautifully shot by the cinematographer Bradford Young. (They reunited for “Selma.”) It was well received at the 2012 Sundance Film Festival , but, like the rest of the entries that year, it was overshadowed by the juggernaut known as “Beasts of the Southern Wild.” Ms. DuVernay became the first black woman to win the dramatic directing award at Sundance, and while that was gratifying, it didn’t translate into any immediate gains. “No one offered me anything,” she said matter-of-factly.

This is in stark contrast with what happened to Colin Trevorrow, whose first feature, “Safety Not Guaranteed,” was also at the 2012 festival. In what has become a familiar story of male success, he went on to direct the relaunch of a franchise behemoth, “Jurassic World.” Women rarely receive those kinds of big breaks. The director Mimi Leder (“Deep Impact”) and the writer Linda Woolverton (“Maleficent”) have made a lot of money for the industry, but they recently told me they, too, don’t get the calls that you might expect. That no one clamored to hire Ms. DuVernay is even less a surprise given the segregation of American cinema and an industry mind-set that deems that a movie with two black leads is no longer simply a movie but a black movie.

Ms. DuVernay started directing first in documentary, where budgets tend to be low, and you don’t necessarily need to ask anyone’s permission, two reasons so many women may gravitate to the field. She made her first feature, “ This Is the Life ” (2008), a documentary about a Los Angeles hip-hop scene, for $10,000: check to check as she put it. She subsequently took $50,000 that she had saved to buy a house and used it to make her first dramatic feature, “I Will Follow” (2010), an autobiographical tale about a niece mourning an aunt. Ms. DuVernay released the movie through a distribution company she founded (she’s a busy woman) and sank $100,000 of the profits into “Middle of Nowhere.”

Through it all she kept her day job, which is how she came to “Selma.” In January 2010, The Daily News in New York ran an item about the script, by Paul Webb, and a scene in which Dr. King flirts with a prostitute or, as The News put it, “MLK Flick has Tryst Issues.” (There’s no such scene in the final movie.) Ms. DuVernay was tapped as a liaison between King family members and the filmmakers. Nothing ever came of that, however, because the project fell apart when Lee Daniels, who was set to be the director, left after years of trying to make the screenplay work with the budget he had been given.

Ms. DuVernay said that the first director who considered “Selma” was Mr. Mann, who was followed by an intriguing list of directors that she ticked off with a practiced air: Stephen Frears, Paul Haggis, Spike Lee and finally Mr. Daniels. She said that with the exit of Mr. Daniels the producers “just gave up.” David Oyelowo (pronounced oh-YELL-ow-oh), who plays Dr. King, did not. Ms. DuVernay had cast him in “Middle of Nowhere,” and he believed that she could handle “Selma.” He made his case for her in a letter to Pathé, the company that originally financed the movie. (Paramount came onboard later.)

Mr. Oyelowo, speaking by phone, said: “If Tom Hooper is allowed to do ‘The King’s Speech,’ having not necessarily done films of a much bigger budget for Pathé, then why not? Why not take a punt on her?”

He said Ms. DuVernay had to do some rewriting of the script to work with a budget that was lower than she ended up with. What had been a liability for her — directing with tiny sums of money — became an unexpected asset and, unlike all the male directors, she was able to make the script and budget work together. At some point, Mr. Oyelowo said, everyone realized that she was the one: “If we can’t make it work with her, this film is never going to work. It’s just never going to happen.”

“Selma” is certainly modest when compared to mega-blockbusters, where $200 million production budgets are no longer uncommon. (Throw in more for marketing and distribution.) For independents, though, and especially for women, it’s significant. (The production budget often cited for “The Hurt Locker” is about $15 million.) The day I visited the “Selma” set, I was struck by how Ms. DuVernay had made the leap from low-budget filmmaking with a handful of people to commanding hundreds. “I just need some white racists on this side!” she yelled at one point. She later complained that the day had been chaotic, but she looked fully in command, her long hair tucked under a scarf, whether riding shotgun on a cart with Mr. Young or on the ground. Later, when lunch was called, Ms. DuVernay greeted the extras who poured off the bridge, calling out thanks and giving and receiving hugs. Among the marchers were men and women who had been there when the tear gas and blood were real. The march, she said, is “a sensitive subject matter to that community,” and she was navigating through a weighty legacy.

At the same time, I was watching a very smart filmmaker command a veritable army partly with hugs. Movie sets can be very unfriendly spaces for women, as she knows. Before she started shooting, she recalled, she sat down with “every single person” on the crew and said, “I’m inviting you to work with me, so this is going to run in the way that I want it to run.”

Even before “Selma,” Ms. DuVernay had beaten the terrible odds that women face by making her own movies on her own terms. It has brought her new attention, but, in deciding what’s next, she needs to choose carefully. Women don’t always get second chances if they stumble, and they don’t have a long, rich history of female filmmakers to learn from. “Do I play that game and try to figure out what the next move is?” Ms. DuVernay wondered. “Or can I be like these guys that just do whatever the interesting stuff is?”

One of those guys is Cary Fukunaga, who went from directing indies like “Sin Nombre” to the HBO show “True Detective.” “The way that these men move,” Ms. DuVernay said admiringly. “The more proven way is to just stay a good girl,” she added “but the artist in me wants to move like Fukunaga’s moving.”

I checked in with Ms. DuVernay again in November after she had locked “Selma.” Screenings had gone well, and Oscar talk was building. She was tired and after two long years on the movie, suddenly unemployed. She won’t be for long. No matter what happens, she believes she can always raise enough money to shoot a new movie.

And while she wants to continue making movies about women, “Selma” has opened her up to new ideas about how she too can move. Her earlier narrative features, she said, were “very interior, intimate stories,” but, “Selma,” with its set pieces and action scenes, has freed her to think about telling larger stories about women.

“It’s not really all about money,” she said, parsing the challenges women directors face. “Some of it is about allowing our imaginations — and giving ourselves permission — to go outside.”

Explore More in TV and Movies

Not sure what to watch next we can help..

“Megalopolis,” the first film from the director Francis Ford Coppola in 13 years, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. Here’s what to know .

Why is the “Planet of the Apes” franchise so gripping and effective? Because it doesn’t monkey around, our movie critic writes .

Luke Newton has been in the sexy Netflix hit “Bridgerton” from the start. But a new season will be his first as co-lead — or chief hunk .

There’s nothing normal about making a “Mad Max” movie, and Anya Taylor-Joy knew that when she signed on to star in “Furiosa,” the newest film in George Miller’s action series.

If you are overwhelmed by the endless options, don’t despair — we put together the best offerings on Netflix , Max , Disney+ , Amazon Prime and Hulu to make choosing your next binge a little easier.

Sign up for our Watching newsletter to get recommendations on the best films and TV shows to stream and watch, delivered to your inbox.

Selma Movie: a Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement

This essay delves into the heart of “Selma,” a film that masterfully captures a pivotal moment in America’s civil rights movement. Directed by Ava DuVernay and released in 2014, it centers on the impactful Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965. The essay highlights how the film brings a raw and immersive experience, offering a perspective that goes beyond the traditional narratives of the era. It particularly praises David Oyelowo’s portrayal of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., not just as an iconic leader but as a multi-dimensional human being facing immense challenges. The essay also acknowledges the film’s focus on lesser-known figures of the movement, emphasizing its tribute to the collective efforts behind civil rights victories. Additionally, it touches on the film’s visual and musical elements, which enhance its emotional depth. While acknowledging the controversy surrounding its portrayal of President Lyndon B. Johnson, the essay underscores the film’s overall significance in educating and inspiring viewers about a crucial period in American history, its ongoing relevance, and the power of collective action for justice. On PapersOwl, there’s also a selection of free essay templates associated with Civil Rights Movement.

How it works

Imagine stepping into a time machine that takes you back to one of the most tumultuous times in American history – that’s what watching “Selma” feels like. Released in 2014 and directed by Ava DuVernay, this film isn’t just a history lesson; it’s a raw, gripping story that throws you right into the heart of the civil rights battle. It’s all about the 1965 marches from Selma to Montgomery, a pivotal moment that shook the nation and pushed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 across the finish line.

“Selma” brings us up close and personal with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., played brilliantly by David Oyelowo. This isn’t just the King you’ve read about in history books; this is King the human, the strategist, the man grappling with the weight of leading a movement amid constant threats and immense pressure. It’s a side of him that isn’t always in the spotlight – his doubts, his fears, and his unwavering commitment to justice.

But it’s not just a one-man show. “Selma” is a tribute to all the unsung heroes of the civil rights movement. It shines a light on figures like Annie Lee Cooper, powerfully portrayed by Oprah Winfrey. She’s fierce, she’s brave, and she represents the countless individuals who stood up against injustice, often putting their lives on the line. The film is a reminder that big changes are often the result of many people’s small, courageous acts.

Visually, “Selma” is stunning. It doesn’t just tell you about the past; it makes you feel it. The cinematography, the music – it all works together to transport you right into those tense, heart-wrenching moments of the marches. And the soundtrack, especially the song “Glory,” is like the heartbeat of the film. It’s not just background music; it’s a powerful voice in the story.

Sure, “Selma” has stirred up some controversy, especially over its portrayal of President Lyndon B. Johnson. Some say it didn’t do justice to his role in the civil rights movement. But that debate doesn’t take away from the film’s power to move and educate. It’s not just about pointing fingers; it’s about showcasing a crucial moment in time and the people who fought to turn the tide of history.

In wrapping up, “Selma” is more than a movie. It’s a deep dive into a crucial chapter of America’s story. It brings to life the struggles, the pain, and the triumphs of those who marched not just for a law, but for the fundamental right to be heard. Watching “Selma” isn’t just about entertainment; it’s about connecting with a part of history that continues to shape our present. It’s a reminder of the power of standing up for what’s right, the impact of collective action, and the ongoing journey towards justice and equality.

Cite this page

Selma Movie: A Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement. (2024, Feb 01). Retrieved from https://papersowl.com/examples/selma-movie-a-cinematic-tribute-to-the-civil-rights-movement/

"Selma Movie: A Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement." PapersOwl.com , 1 Feb 2024, https://papersowl.com/examples/selma-movie-a-cinematic-tribute-to-the-civil-rights-movement/

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Selma Movie: A Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/selma-movie-a-cinematic-tribute-to-the-civil-rights-movement/ [Accessed: 18 May. 2024]

"Selma Movie: A Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement." PapersOwl.com, Feb 01, 2024. Accessed May 18, 2024. https://papersowl.com/examples/selma-movie-a-cinematic-tribute-to-the-civil-rights-movement/

"Selma Movie: A Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement," PapersOwl.com , 01-Feb-2024. [Online]. Available: https://papersowl.com/examples/selma-movie-a-cinematic-tribute-to-the-civil-rights-movement/. [Accessed: 18-May-2024]

PapersOwl.com. (2024). Selma Movie: A Cinematic Tribute to the Civil Rights Movement . [Online]. Available at: https://papersowl.com/examples/selma-movie-a-cinematic-tribute-to-the-civil-rights-movement/ [Accessed: 18-May-2024]

Don't let plagiarism ruin your grade

Hire a writer to get a unique paper crafted to your needs.

Our writers will help you fix any mistakes and get an A+!

Please check your inbox.

You can order an original essay written according to your instructions.

Trusted by over 1 million students worldwide

1. Tell Us Your Requirements

2. Pick your perfect writer

3. Get Your Paper and Pay

Hi! I'm Amy, your personal assistant!

Don't know where to start? Give me your paper requirements and I connect you to an academic expert.

short deadlines

100% Plagiarism-Free

Certified writers

U.S. Intellectual History Blog

Robert Greene II

January 11, 2015

‘Selma’: A Review

Seeing Selma in theaters Friday night was a moving experience. In recent years, since beginning my training as a historian in earnest, I’ve approached films based on historical figures and events with a critical eye. Often this means watching a historical biopic with a mix of joy (a film I can care about!) and trepidation (my gosh, did they even listen to the historical consultant during this scene?). When it comes to films about the African American experience, in particular, my heartstrings are often ready to be tugged while my brain is on guard against historical inaccuracies. With Selma , the essence of the fight for voting rights is captured on film in a vivid and memorable manner.

I knew the deaths of the four little girls was coming—but the scene jolted me just the same. Violence is a key part of Selma , and it has to be. The threat of violence lurks everywhere King and his cohort when they enter Alabama. And of course violence and the use of force is at the heart of the climax of the film—the brutal attack by Alabama troopers on peaceful protesters at the Edmund Pettis Bridge on March 7, 1965. Violence, of course, would claim the lives of Dr. King and so many others in the Civil Rights Movement. The acts of violence perpetrated upon activists would also play a role in sparking national conversations about the citizenship rights of African Americans.

The film has a sprawling cast of characters, a who’s who of activists known to all civil rights historians and many American historians. It’s unfortunate, however, that we barely get a sense of who these people were—Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young, Diane Nash and James Bevel, among others. Hosea Williams (Wendell Pierce) and John Lewis (Stephan James) get a little extra dialogue and development on screen, largely due to their presence at the “Bloody Sunday” incident from March 7, 1965. It’s too bad Selma wasn’t made into a miniseries, instead of a feature film. More time could have been given to these activists, and still more devoted to activists native to Selma such as Amelia Robinson (Lorraine Toussaint), if it weren’t for the limits of a feature-length film.

Selma may have been better off being called King. It reminded me in many ways of the 2012 film Lincoln . Both films portray beloved American heroes in pivotal moments in their public and private lives. Not your standard biopic, Lincoln chose to focus on the sixteenth president’s determined drive to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, abolishing slavery, through Congress while also wrapping up the American Civil War. Both films were also criticized for historical inaccuracies— Lincoln for leaving out figures such as Frederick Douglass and Selma for downplaying President Lyndon Johnson’s support for the Voting Rights Act.

DuVernay’s film is a clear example of a yearning for a Civil Rights Movement narrative that privileges the black experience. Selma is heavily focused on King. Down the road, perhaps, a different film about Selma will be made, in which MLK is a character often mention but hardly seen by hardworking activists. And I agree that any film based on a historic moment should be scrutinized for inaccuracies and lapses in factual correctness. But I do believe Selma captures the moment of early 1965—the attempt to continue the fight for full equality in American society for African Americans. There are brief mentions of Vietnam, and glimpses here and there of King’s own evolution in thinking about civil rights, economic rights, and human rights. But above all, Selma gets to the heart of the campaign for voting rights in the winter and spring of 1965.

Go see Selma. There are parts of the film, whether concerning LBJ or the local activists, I wished had been done differently. I think it’s a shame Selma wasn’t part of a longer miniseries about the Civil Rights Movement. But Selma is worth seeing, and worth feeling as a film.

Tags: Civil Rights Movement , historical memory , historical representation , Martin Luther King, Jr. , movies and art , public memory

Previous Post

6 thoughts on this post, s-usih comment policy.

We ask that those who participate in the discussions generated in the Comments section do so with the same decorum as they would in any other academic setting or context. Since the USIH bloggers write under our real names, we would prefer that our commenters also identify themselves by their real name. As our primary goal is to stimulate and engage in fruitful and productive discussion, ad hominem attacks (personal or professional), unnecessary insults, and/or mean-spiritedness have no place in the USIH Blog’s Comments section. Therefore, we reserve the right to remove any comments that contain any of the above and/or are not intended to further the discussion of the topic of the post. We welcome suggestions for corrections to any of our posts. As the official blog of the Society of US Intellectual History, we hope to foster a diverse community of scholars and readers who engage with one another in discussions of US intellectual history, broadly understood.