Creating Your Assignment Sheets

Main navigation.

In order to help our students best engage with the writing tasks we assign them, we need as a program to scaffold the assignments with not only effectively designed activities, but equally effectively designed assignment sheets that clearly explain the learning objectives, purpose, and logistics for the assignment.

Checklist for Assignment Sheet Design

As a program, instructors should compose assignment sheets that contain the following elements.

A clear description of the assignment and its purpose . How does this assignment contribute to their development as writers in this class, and perhaps beyond? What is the genre of the assignment? (e.g., some students will be familiar with rhetorical analysis, some will not).

Learning objectives for the assignment . The learning objectives for each assignment are available on the TeachingWriting website. While you might include others objectives, or tweak the language of these a bit to fit with how you teach rhetoric, these objectives should appear in some form on the assignment sheet and should be echoed in your rubric.

Due dates or timeline, including dates for drafts . This should include specific times and procedures for turning in drafts. You should also indicate dates for process assignments and peer review if they are different from the main assignment due dates.

Details about format (including word count, documentation form) . This might also be a good place to remind them of any technical specifications (even if you noted them on the syllabus).

Discussion of steps of the process. These might be “suggested” to avoid the implication that there is one best way to achieve a rhetorical analysis.

Evaluation criteria / grading rubric that is in alignment with learning objectives . While the general PWR evaluation criteria is a good starting place, it is best to customize your rubric to the specific purposes of your assignment, ideally incorporating some of the language from the learning goals. In keeping with PWR’s elevation of rhetoric over rules, it’s generally best to avoid rubrics that assign specific numbers of points to specific features of the text since that suggests a fairly narrow range of good choices for students’ rhetorical goals. (This is not to say that points shouldn’t be used: it’s just more in the spirit of PWR’s rhetorical commitments to use them holistically.)

Canvas Versions of Assignment Sheets

Canvas offers an "assignment" function you can use to share assignment sheet information with students. It provides you with the opportunity to upload a rubric in conjunction with assignment details; to create an upload space for student work (so they can upload assignments directly to Canvas); to link the assignment submissions to Speedgrader, Canvas's internal grading platform; and to sync your assigned grades with the gradebook. While these are very helpful features, don't hesitate to reach out to the Canvas Help team or our ATS for support when you set them up for the first time. In addition, you should always provide students with access to a separate PDF assignment sheet. Don't just embed the information in the Canvas assignment field; if students have trouble accessing Canvas for any reason (Canvas outage; tech issues), they won't be able to access that information.

In addition, you might creating video mini-overviews or "talk-throughs" of your assignments. These should serve as supplements to the assignment sheets, not as a replacement for them.

Sample Assignment Sheets

Check out some examples of Stanford instructors' assignment sheets via the links below. Note that these links will route you to our Canvas PWR Program Materials site, so you must have access to the Canvas page in order to view these files:

See examples of rhetorical analysis assignment sheets

See examples of texts in conversation assignment sheets

See examples of research-based argument assignment sheets

Further reading on assignment sheets

- Sign Up for Mailing List

- Search Search

Username or Email Address

Remember Me

Resources for Teachers: Creating Writing Assignments

This page contains four specific areas:

Creating Effective Assignments

Checking the assignment, sequencing writing assignments, selecting an effective writing assignment format.

Research has shown that the more detailed a writing assignment is, the better the student papers are in response to that assignment. Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an “assignment sheet” tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment. Assignment sheets should detail:

- the kind of writing expected

- the scope of acceptable subject matter

- the length requirements

- formatting requirements

- documentation format

- the amount and type of research expected (if any)

- the writer’s role

- deadlines for the first draft and its revision

Providing questions or needed data in the assignment helps students get started. For instance, some questions can suggest a mode of organization to the students. Other questions might suggest a procedure to follow. The questions posed should require that students assert a thesis.

The following areas should help you create effective writing assignments.

Examining your goals for the assignment

- How exactly does this assignment fit with the objectives of your course?

- Should this assignment relate only to the class and the texts for the class, or should it also relate to the world beyond the classroom?

- What do you want the students to learn or experience from this writing assignment?

- Should this assignment be an individual or a collaborative effort?

- What do you want students to show you in this assignment? To demonstrate mastery of concepts or texts? To demonstrate logical and critical thinking? To develop an original idea? To learn and demonstrate the procedures, practices, and tools of your field of study?

Defining the writing task

- Is the assignment sequenced so that students: (1) write a draft, (2) receive feedback (from you, fellow students, or staff members at the Writing and Communication Center), and (3) then revise it? Such a procedure has been proven to accomplish at least two goals: it improves the student’s writing and it discourages plagiarism.

- Does the assignment include so many sub-questions that students will be confused about the major issue they should examine? Can you give more guidance about what the paper’s main focus should be? Can you reduce the number of sub-questions?

- What is the purpose of the assignment (e.g., review knowledge already learned, find additional information, synthesize research, examine a new hypothesis)? Making the purpose(s) of the assignment explicit helps students write the kind of paper you want.

- What is the required form (e.g., expository essay, lab report, memo, business report)?

- What mode is required for the assignment (e.g., description, narration, analysis, persuasion, a combination of two or more of these)?

Defining the audience for the paper

- Can you define a hypothetical audience to help students determine which concepts to define and explain? When students write only to the instructor, they may assume that little, if anything, requires explanation. Defining the whole class as the intended audience will clarify this issue for students.

- What is the probable attitude of the intended readers toward the topic itself? Toward the student writer’s thesis? Toward the student writer?

- What is the probable educational and economic background of the intended readers?

Defining the writer’s role

- Can you make explicit what persona you wish the students to assume? For example, a very effective role for student writers is that of a “professional in training” who uses the assumptions, the perspective, and the conceptual tools of the discipline.

Defining your evaluative criteria

1. If possible, explain the relative weight in grading assigned to the quality of writing and the assignment’s content:

- depth of coverage

- organization

- critical thinking

- original thinking

- use of research

- logical demonstration

- appropriate mode of structure and analysis (e.g., comparison, argument)

- correct use of sources

- grammar and mechanics

- professional tone

- correct use of course-specific concepts and terms.

Here’s a checklist for writing assignments:

- Have you used explicit command words in your instructions (e.g., “compare and contrast” and “explain” are more explicit than “explore” or “consider”)? The more explicit the command words, the better chance the students will write the type of paper you wish.

- Does the assignment suggest a topic, thesis, and format? Should it?

- Have you told students the kind of audience they are addressing — the level of knowledge they can assume the readers have and your particular preferences (e.g., “avoid slang, use the first-person sparingly”)?

- If the assignment has several stages of completion, have you made the various deadlines clear? Is your policy on due dates clear?

- Have you presented the assignment in a manageable form? For instance, a 5-page assignment sheet for a 1-page paper may overwhelm students. Similarly, a 1-sentence assignment for a 25-page paper may offer insufficient guidance.

There are several benefits of sequencing writing assignments:

- Sequencing provides a sense of coherence for the course.

- This approach helps students see progress and purpose in their work rather than seeing the writing assignments as separate exercises.

- It encourages complexity through sustained attention, revision, and consideration of multiple perspectives.

- If you have only one large paper due near the end of the course, you might create a sequence of smaller assignments leading up to and providing a foundation for that larger paper (e.g., proposal of the topic, an annotated bibliography, a progress report, a summary of the paper’s key argument, a first draft of the paper itself). This approach allows you to give students guidance and also discourages plagiarism.

- It mirrors the approach to written work in many professions.

The concept of sequencing writing assignments also allows for a wide range of options in creating the assignment. It is often beneficial to have students submit the components suggested below to your course’s STELLAR web site.

Use the writing process itself. In its simplest form, “sequencing an assignment” can mean establishing some sort of “official” check of the prewriting and drafting steps in the writing process. This step guarantees that students will not write the whole paper in one sitting and also gives students more time to let their ideas develop. This check might be something as informal as having students work on their prewriting or draft for a few minutes at the end of class. Or it might be something more formal such as collecting the prewriting and giving a few suggestions and comments.

Have students submit drafts. You might ask students to submit a first draft in order to receive your quick responses to its content, or have them submit written questions about the content and scope of their projects after they have completed their first draft.

Establish small groups. Set up small writing groups of three-five students from the class. Allow them to meet for a few minutes in class or have them arrange a meeting outside of class to comment constructively on each other’s drafts. The students do not need to be writing on the same topic.

Require consultations. Have students consult with someone in the Writing and Communication Center about their prewriting and/or drafts. The Center has yellow forms that we can give to students to inform you that such a visit was made.

Explore a subject in increasingly complex ways. A series of reading and writing assignments may be linked by the same subject matter or topic. Students encounter new perspectives and competing ideas with each new reading, and thus must evaluate and balance various views and adopt a position that considers the various points of view.

Change modes of discourse. In this approach, students’ assignments move from less complex to more complex modes of discourse (e.g., from expressive to analytic to argumentative; or from lab report to position paper to research article).

Change audiences. In this approach, students create drafts for different audiences, moving from personal to public (e.g., from self-reflection to an audience of peers to an audience of specialists). Each change would require different tasks and more extensive knowledge.

Change perspective through time. In this approach, students might write a statement of their understanding of a subject or issue at the beginning of a course and then return at the end of the semester to write an analysis of that original stance in the light of the experiences and knowledge gained in the course.

Use a natural sequence. A different approach to sequencing is to create a series of assignments culminating in a final writing project. In scientific and technical writing, for example, students could write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic. The next assignment might be a progress report (or a series of progress reports), and the final assignment could be the report or document itself. For humanities and social science courses, students might write a proposal requesting approval of a particular topic, then hand in an annotated bibliography, and then a draft, and then the final version of the paper.

Have students submit sections. A variation of the previous approach is to have students submit various sections of their final document throughout the semester (e.g., their bibliography, review of the literature, methods section).

In addition to the standard essay and report formats, several other formats exist that might give students a different slant on the course material or allow them to use slightly different writing skills. Here are some suggestions:

Journals. Journals have become a popular format in recent years for courses that require some writing. In-class journal entries can spark discussions and reveal gaps in students’ understanding of the material. Having students write an in-class entry summarizing the material covered that day can aid the learning process and also reveal concepts that require more elaboration. Out-of-class entries involve short summaries or analyses of texts, or are a testing ground for ideas for student papers and reports. Although journals may seem to add a huge burden for instructors to correct, in fact many instructors either spot-check journals (looking at a few particular key entries) or grade them based on the number of entries completed. Journals are usually not graded for their prose style. STELLAR forums work well for out-of-class entries.

Letters. Students can define and defend a position on an issue in a letter written to someone in authority. They can also explain a concept or a process to someone in need of that particular information. They can write a letter to a friend explaining their concerns about an upcoming paper assignment or explaining their ideas for an upcoming paper assignment. If you wish to add a creative element to the writing assignment, you might have students adopt the persona of an important person discussed in your course (e.g., an historical figure) and write a letter explaining his/her actions, process, or theory to an interested person (e.g., “pretend that you are John Wilkes Booth and write a letter to the Congress justifying your assassination of Abraham Lincoln,” or “pretend you are Henry VIII writing to Thomas More explaining your break from the Catholic Church”).

Editorials . Students can define and defend a position on a controversial issue in the format of an editorial for the campus or local newspaper or for a national journal.

Cases . Students might create a case study particular to the course’s subject matter.

Position Papers . Students can define and defend a position, perhaps as a preliminary step in the creation of a formal research paper or essay.

Imitation of a Text . Students can create a new document “in the style of” a particular writer (e.g., “Create a government document the way Woody Allen might write it” or “Write your own ‘Modest Proposal’ about a modern issue”).

Instruction Manuals . Students write a step-by-step explanation of a process.

Dialogues . Students create a dialogue between two major figures studied in which they not only reveal those people’s theories or thoughts but also explore areas of possible disagreement (e.g., “Write a dialogue between Claude Monet and Jackson Pollock about the nature and uses of art”).

Collaborative projects . Students work together to create such works as reports, questions, and critiques.

Assignment Sheet

One of the many sheet uses specifically directed toward academic purpose is the assignment sheet. Students are given assignments and have to submit a research regarding the topic given for assignment in an assignment sheet.

As with the balance sheet, assignment sheet examples in the page provide further information in the sheet uses and functions of an assignment sheet. Feel free to scroll down and get a closer look on the samples provided for in the page. The sheets in word are all available for download by clicking on the download link button below the sample. So stay awhile and have a good look around.

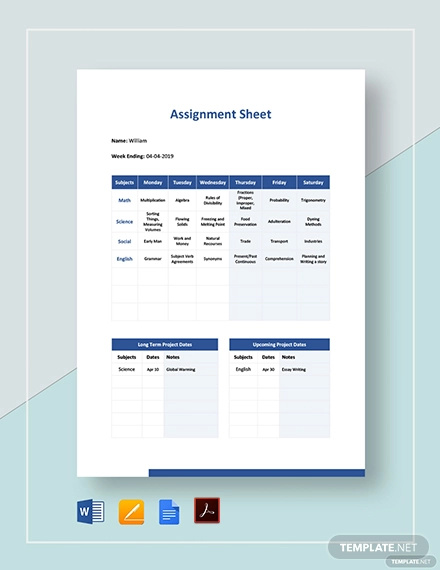

Assignment Sheet Example

- Google Docs

- Editable PDF

Size: A4, US

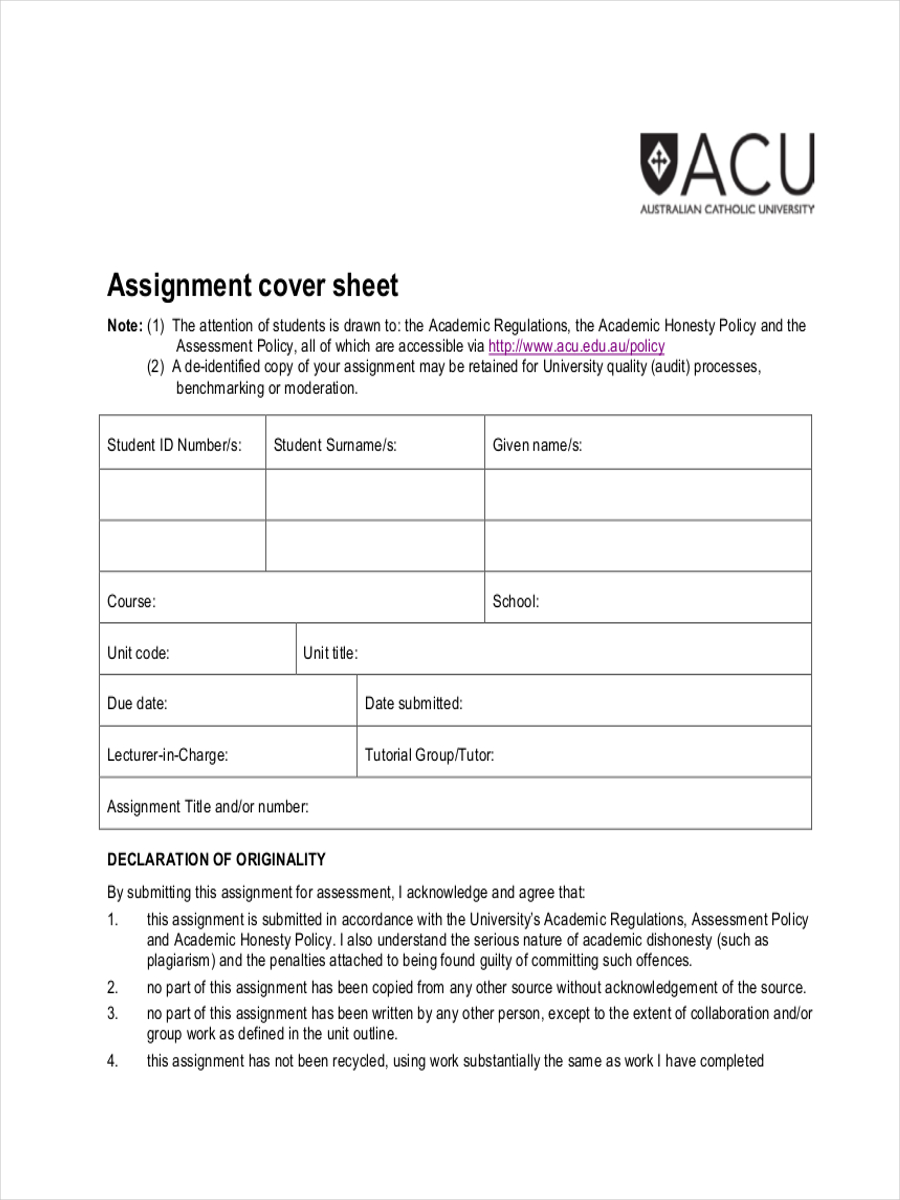

Assignment Cover Sheet Example

Size: 82 KB

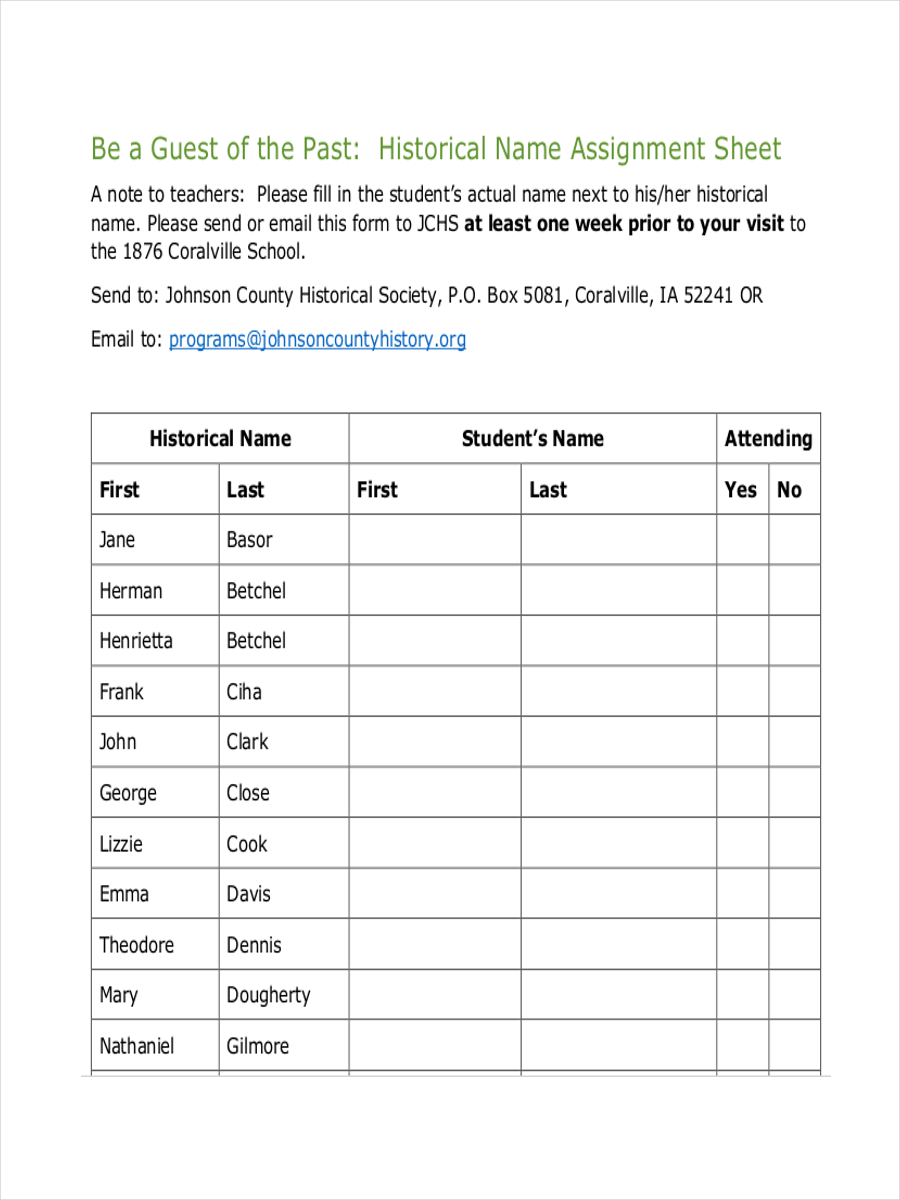

Name Sheet for Assignment

Size: 159 KB

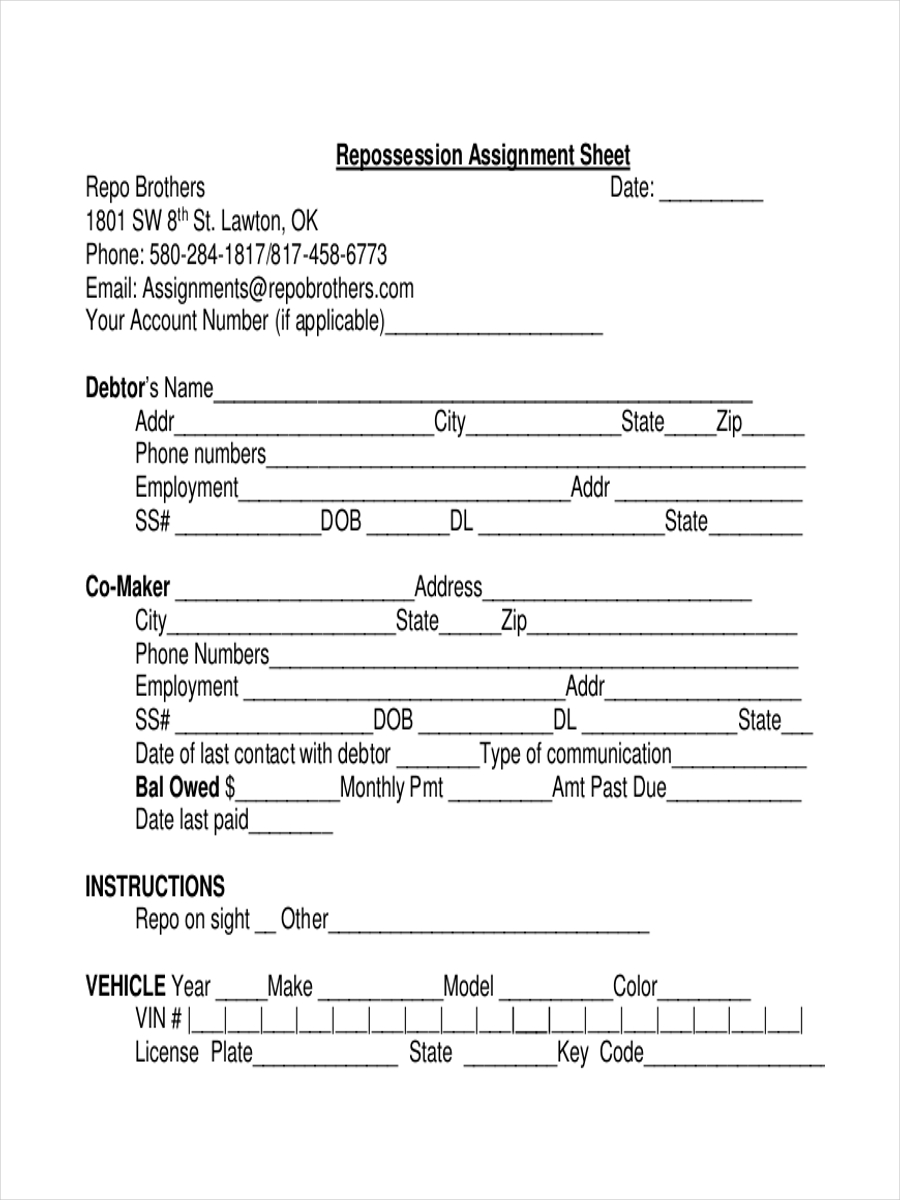

Repossession Assignment Sheet

Size: 260 KB

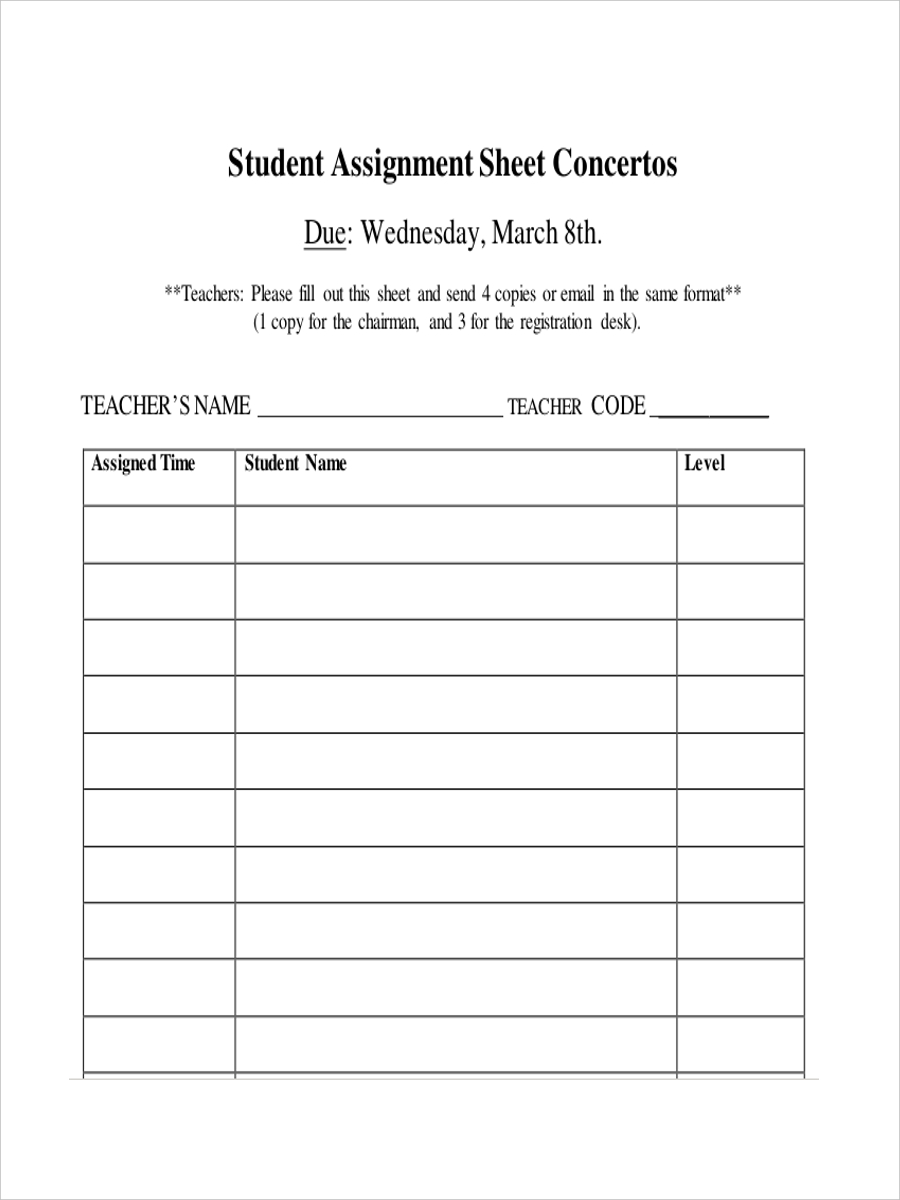

Sheet for Student Assignment

Size: 98 KB

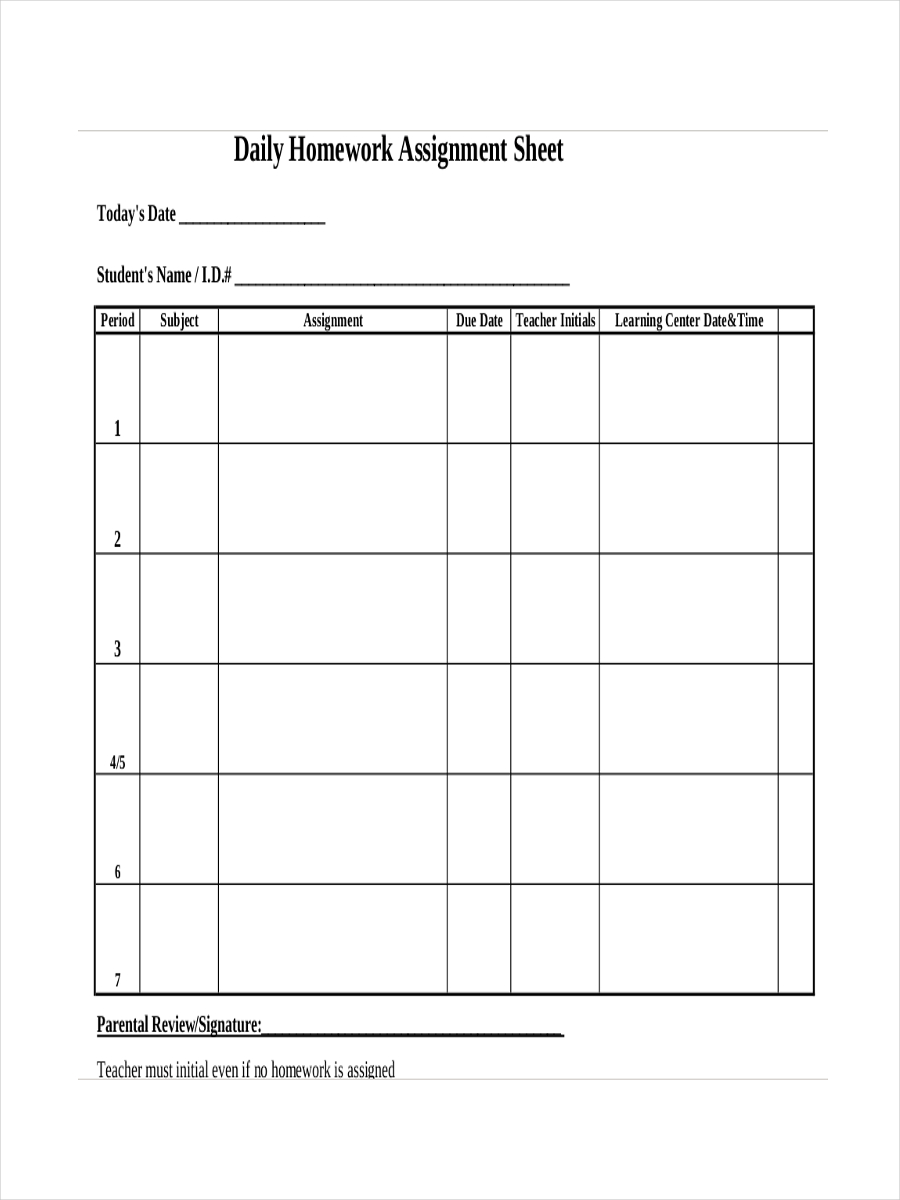

Homework Assignment Sheet

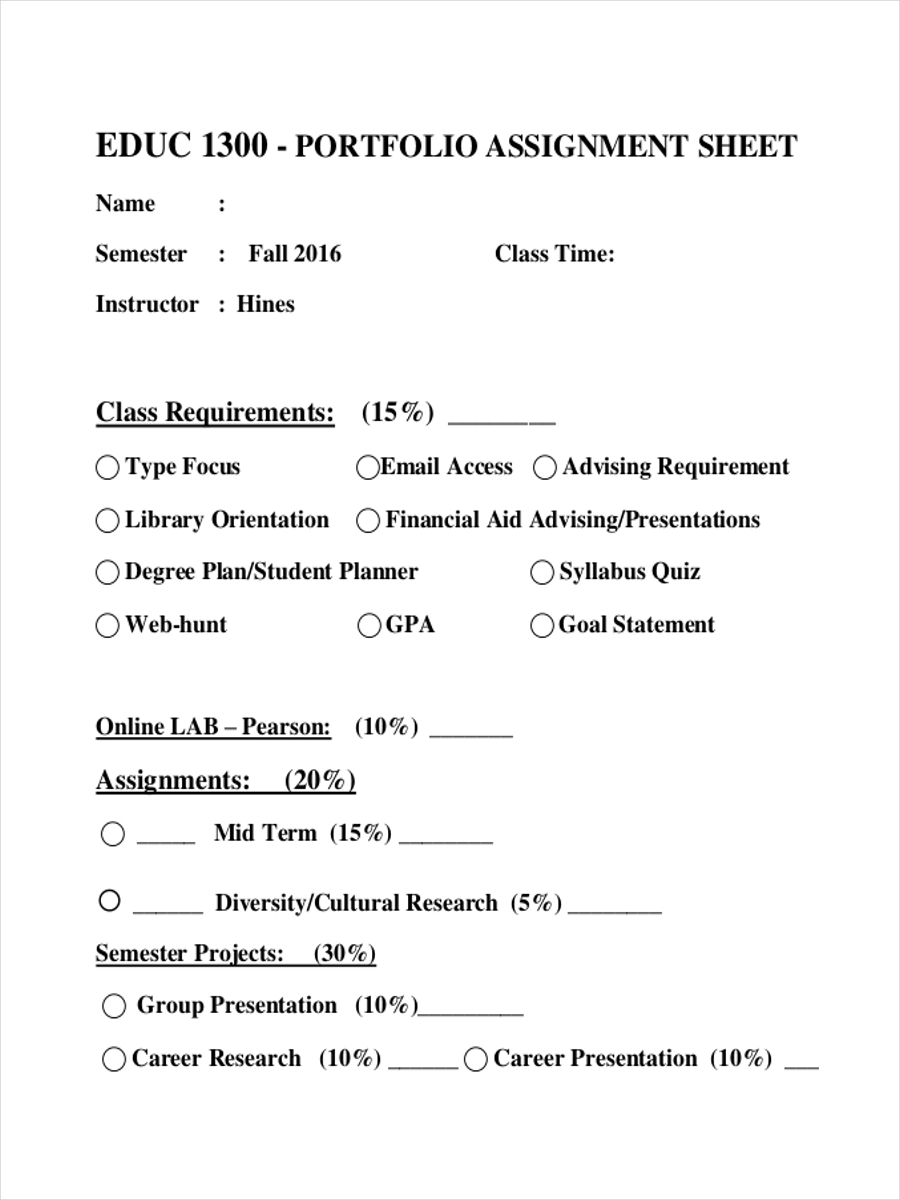

Portfolio Assignment Sample Sheet

Size: 213 KB

What Is an Assignment Sheet?

An assignment sheet is a document written for the statement of purpose of delegating or appointing a task or research and discussion on a topic or purpose.

General sheet examples in doc provide further aid regarding an assignment sheet and how it is made. Just click on the download link button below the samples to access the files.

Reviewing an Assignment Sheet

In reviewing an assignment sheet, the following questions need to be asked or satisfied:

- What is it that the assignment is asking me to do?

- Are there clear instructions in completing the assignment?

- What needs to be done in order to be successful in the assignment?

- Are the due dates clearly stated and shown?

- Are the technical requirements stated clearly?

- Is there any resource or resources included?

- Is the assignment stated in a clear language?

- Is the tone appealing to students?

- Do I have clear understanding why the assignment is being done?

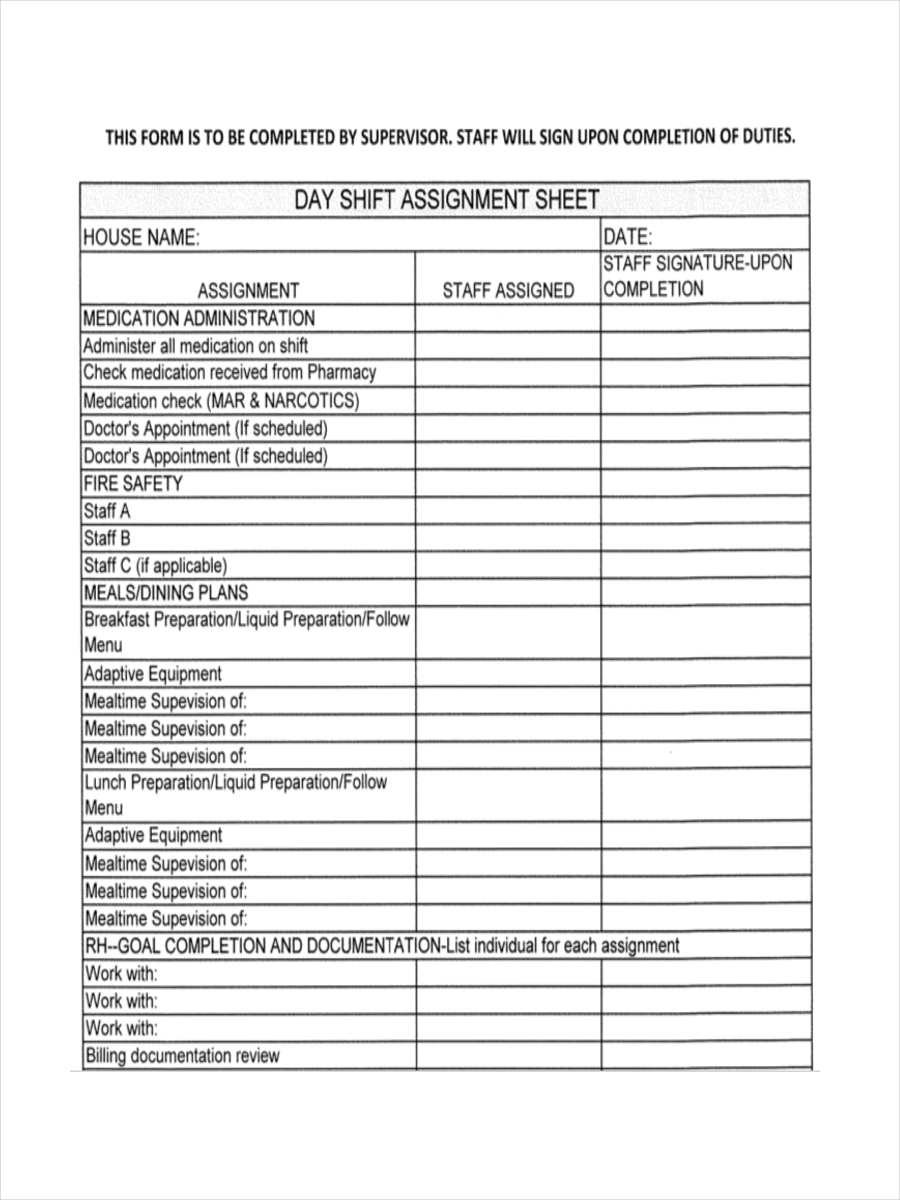

Day Shift Assignment Sheet Example

Size: 448 KB

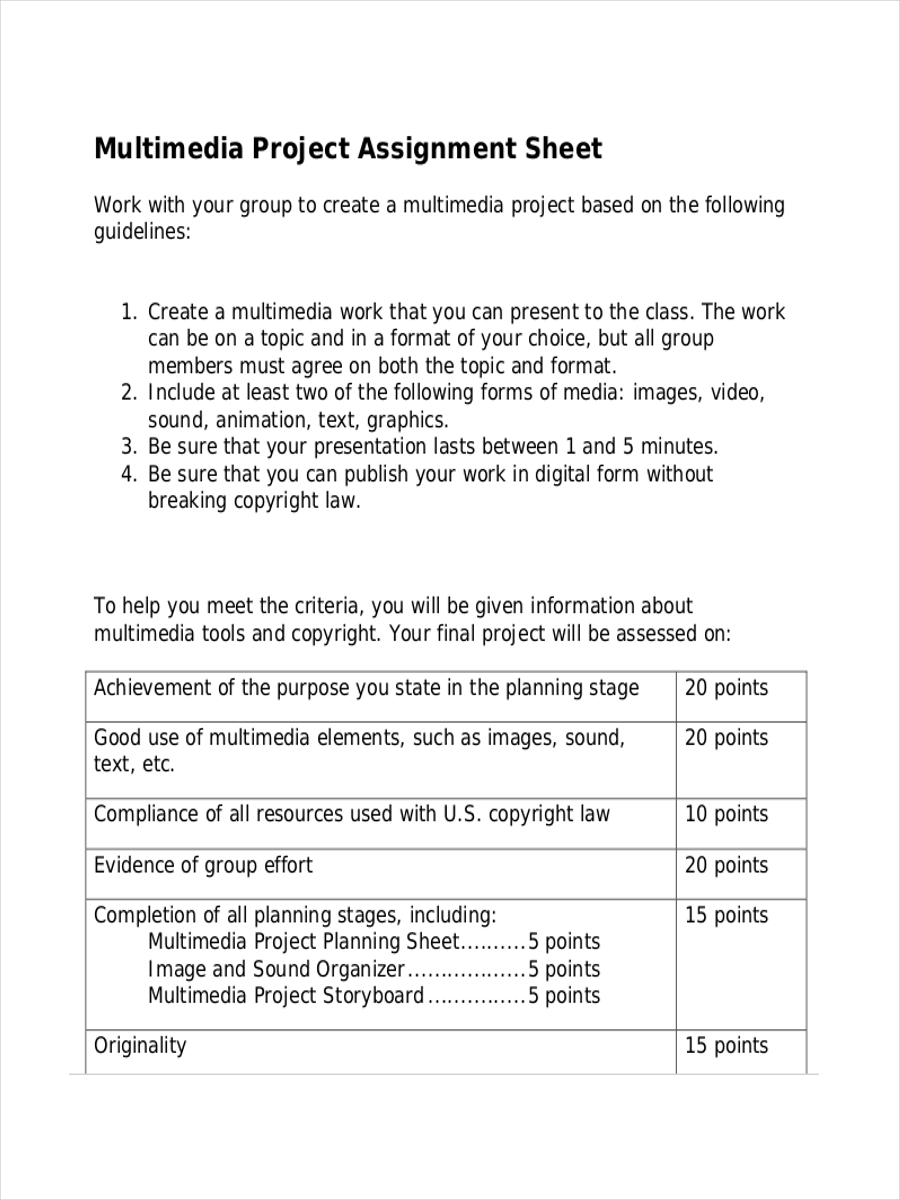

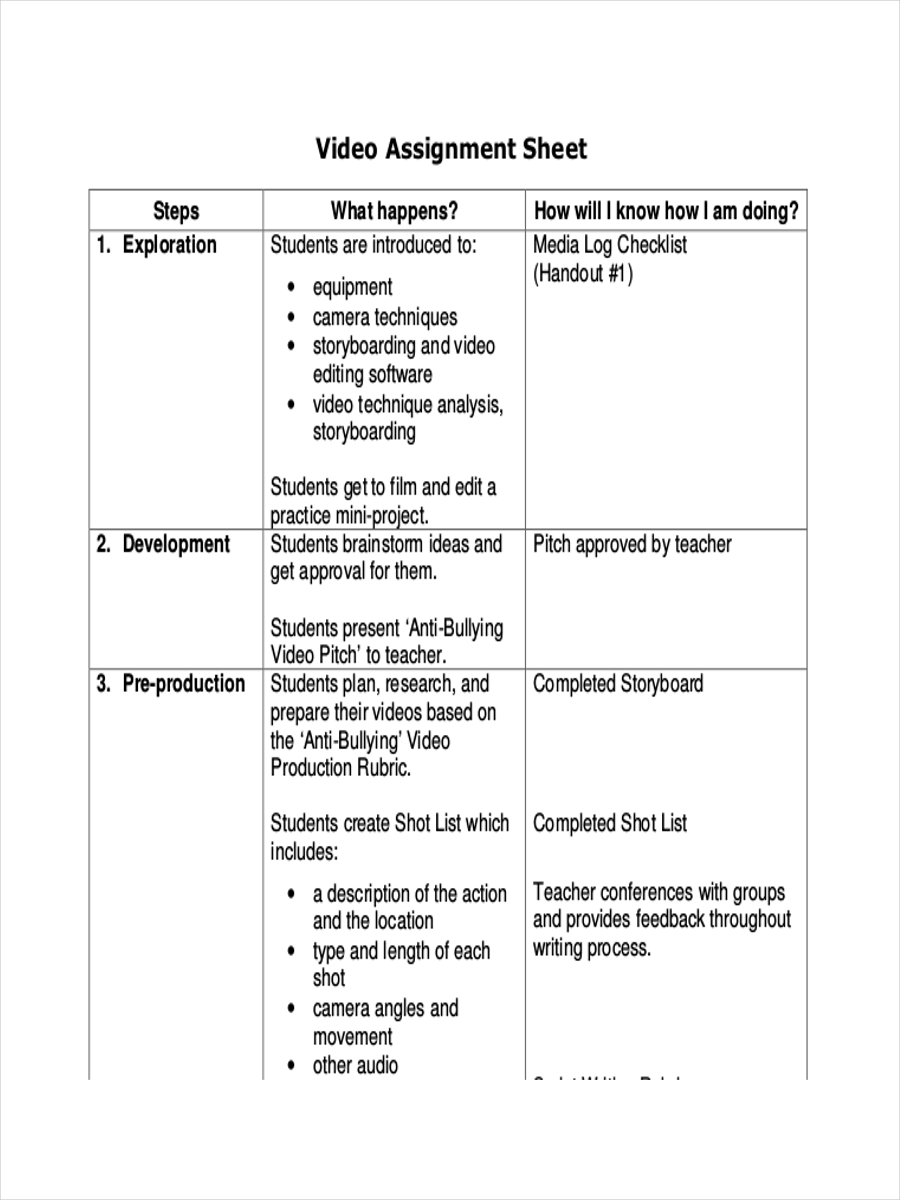

Sheet for Multimedia Assignment

Size: 15 KB

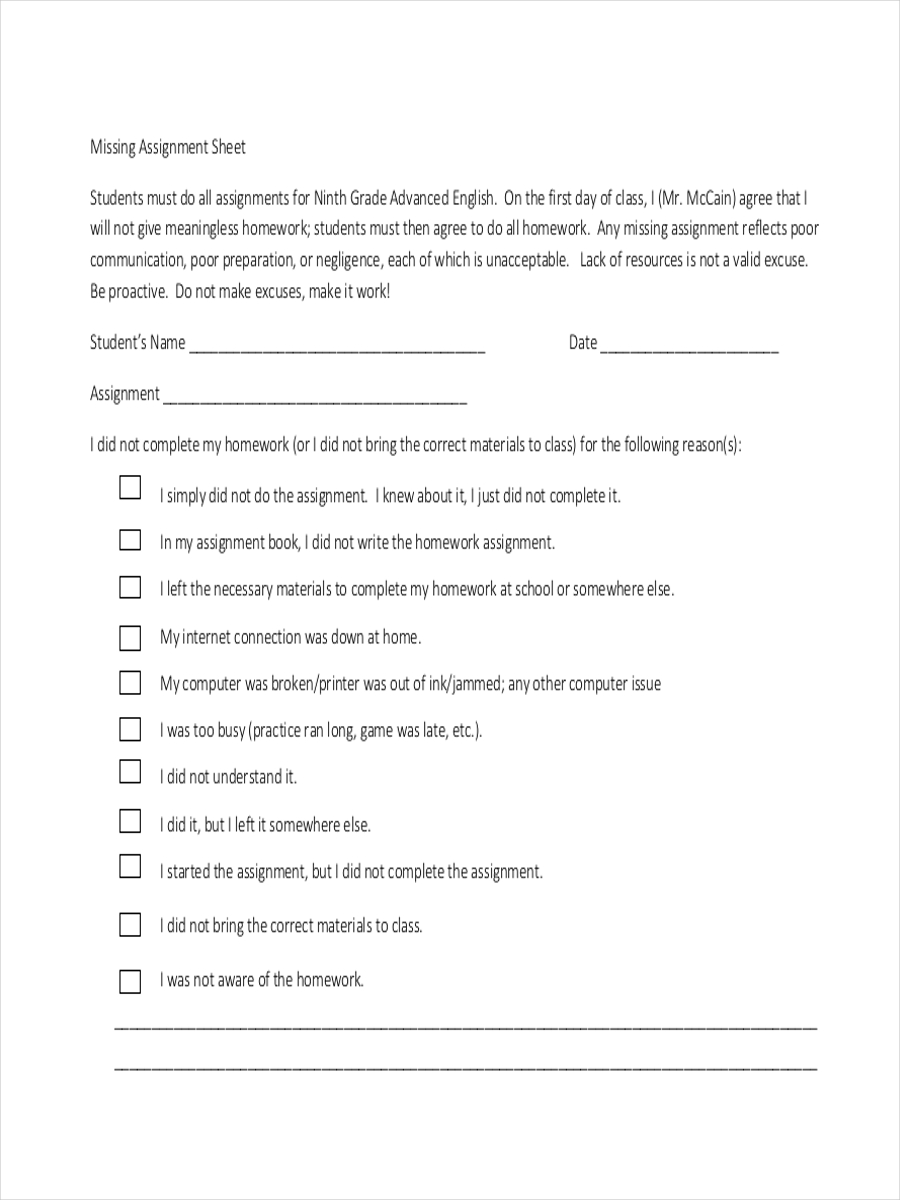

Missing Assignment Sample Sheet

Size: 141 KB

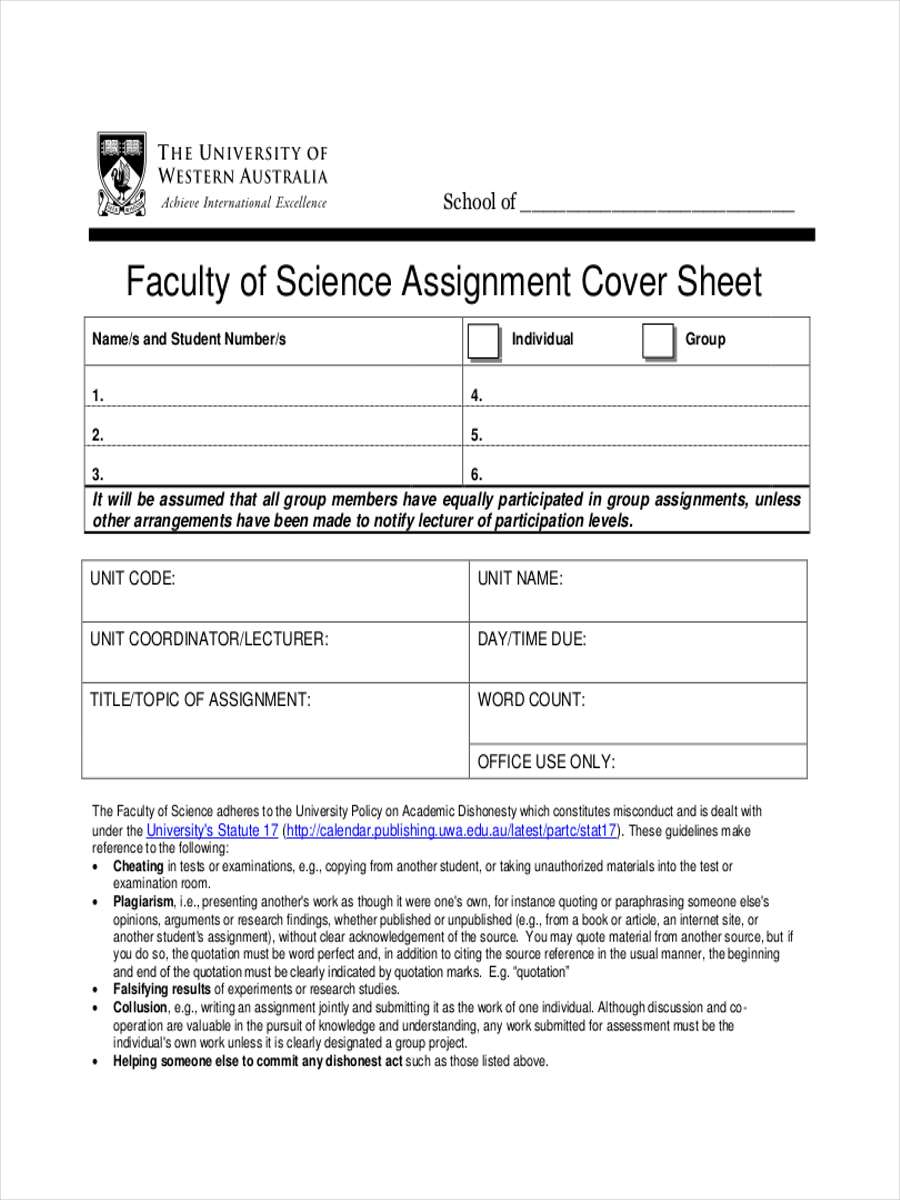

Sheet for Faculty Assignment

Size: 232 KB

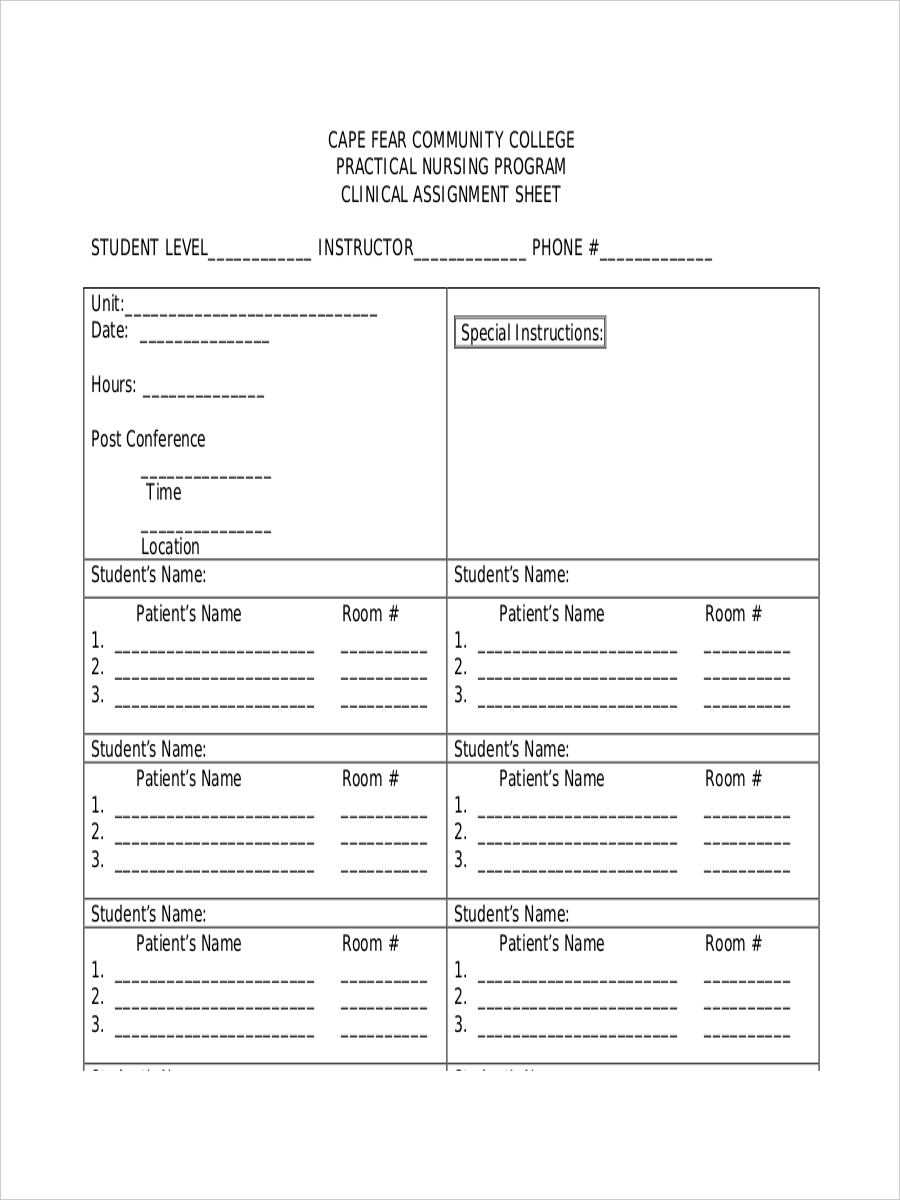

Sheet for Clinical Assignment

Video Assignment Sample Sheet

Size: 27 KB

How to Make an Effective Assignment Sheet, for Students

In creating an effective assignment sheet, the following have to be considered:

- Plan the task or purpose of the assignment. Ensure that the students understand critical tasks that need to be done which includes research, simple analysis , synthesis, and summary of the assignment.

- Schedule the whole process. Make a step by step instructions of what the project plan seeks to accomplish.

- Explain the requirements for the assignment.

- Decide on the due dates for the assignments. Include detailed instructions for important writing assignments.

- Include all important information that would make up a strong paper during submission. Help the students to understand the importance of sources. Discuss on formatting of the assignment and other suggestions in connection to the assignment.

- Include the grading criteria for your assignments.

Sample sheet templates and sheet examples in pdf are found in the page for your review. The examples further show how an assignment sheet is structured and the format it follows. To download an example, click on the download link button below the example.

AI Generator

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

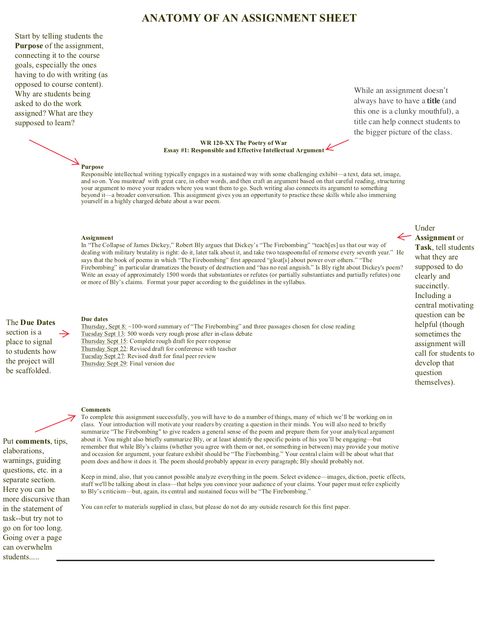

Anatomy of an Assignment Sheet

Guides & tips.

In this guide, we invite instructors to think through the different sections of an assignment sheet and perhaps take a fresh look at their own assignment sheets. At the bottom of the page, you’ll find some insights into more effective assignment sheets from Writing Consultants working in the CAS Writing Center .

Key Elements

Things to Consider

- While an assignment does not necessarily have to have a title (this one’s a clunky mouthful), it can help students connect an individual assignment to the bigger context of the class.

- Start by telling students the purpose of the assignment, connecting it to the course goals, especially the ones having to do with writing as opposed to course content. Why are students being asked to do the work assigned? What are they supposed to learn?

- The due dates (or submission guidelines) section is a chance to draw students’ attention to how the assignment will be scaffolded.

- Under assignment (or task ), tell students what they are supposed to do clearly and succinctly. Including a central motivating question can be helpful, though sometimes the assignment will call for students to develop that question themselves.

- In the comments section (or additional information) you can include elaborations, warnings, guiding questions, etc. in a separate section. Here you can be more discursive than in the statement of task, but try not to go on for too long. Going over a page can overwhelm students.

Additional Resources

- Learn more about transparent assignment design and use a template for transparent assignments ( Winkelmes 2013-2016 ).

- Look at the Writing Program’s templates for major assignments in WR 120 to begin customizing your own assignment sheets.

Tips from Tutors: What Writing Consultants Say About More Effective Assignment Sheets

Keep assignment sheets short (~1 page if possible)..

- Students genuinely want to understand what’s being asked of them, but if there is too much information, they don’t always know how to prioritize what to focus on.

- Focus on specific questions you want students to answer or tasks you want them to complete. Avoid content that isn’t specifically related to the assignment itself.

- It’s generally best not to include all assignments for the semester in a single document. While it can be helpful to have one sheet or section of the syllabus with all assignments listed, it’s best to give each assignment its own document with detailed expectations.

- Students need some guidelines for assignments. Following the WP “anatomy of an assignment” guidelines (above) helps students as they move from one WR course to the next, and it also helps consultants figure out where to find key information more quickly.

Give students some choices, but be (overly) clear about your expectations.

- It’s especially challenging for WR 120 students to come up with their own “research question” and then answer it. If you’re asking them to do that, be very specific about what you want them to do and what parameters they should work within.

- Don’t give students a long list of questions to consider — or, if you do, be incredibly explicit about what questions are intended to generate ideas as opposed to what questions they actually need to answer in their paper.

- The best assignment sheets tend to be those that give students a set number of options and then ask them to pick one to answer.

Give clear (as in legible and also as in straightforward) feedback.

- Provide typed rather than handwritten comments.

- Avoid cryptic feedback like “awkward” or “?” that could be interpreted in different ways.

- If you write comments in shorthand, be sure to provide students with a key.

- Provide feedback as specific questions that students can either address themselves, or discuss with a writing consultant (or you!)

Remember WR courses are introductory courses.

- Choose course readings for written assignments that lend themselves to teaching writing as opposed to seminal texts or your personal favorites.

- Go over all readings that students are expected to write about in class and devote extra time to particularly challenging ones. If you are working on difficult topic and/or dense texts, don’t assume your students can navigate them without explicit scaffolding in class.

- Not all students have been taught how to analyze quotations and use them as evidence to support their argument, so be sure to spend time teaching these skills.

- Don’t take anything for granted. Students are coming from all kinds of educational backgrounds, and our courses meant to reinforce (but sometimes teach for the first time) skills all students will need for future college papers. You may also want to read about the “hidden curriculum” in writing classes when considering inclusivity and assumptions.

Understanding Assignments

What this handout is about.

The first step in any successful college writing venture is reading the assignment. While this sounds like a simple task, it can be a tough one. This handout will help you unravel your assignment and begin to craft an effective response. Much of the following advice will involve translating typical assignment terms and practices into meaningful clues to the type of writing your instructor expects. See our short video for more tips.

Basic beginnings

Regardless of the assignment, department, or instructor, adopting these two habits will serve you well :

- Read the assignment carefully as soon as you receive it. Do not put this task off—reading the assignment at the beginning will save you time, stress, and problems later. An assignment can look pretty straightforward at first, particularly if the instructor has provided lots of information. That does not mean it will not take time and effort to complete; you may even have to learn a new skill to complete the assignment.

- Ask the instructor about anything you do not understand. Do not hesitate to approach your instructor. Instructors would prefer to set you straight before you hand the paper in. That’s also when you will find their feedback most useful.

Assignment formats

Many assignments follow a basic format. Assignments often begin with an overview of the topic, include a central verb or verbs that describe the task, and offer some additional suggestions, questions, or prompts to get you started.

An Overview of Some Kind

The instructor might set the stage with some general discussion of the subject of the assignment, introduce the topic, or remind you of something pertinent that you have discussed in class. For example:

“Throughout history, gerbils have played a key role in politics,” or “In the last few weeks of class, we have focused on the evening wear of the housefly …”

The Task of the Assignment

Pay attention; this part tells you what to do when you write the paper. Look for the key verb or verbs in the sentence. Words like analyze, summarize, or compare direct you to think about your topic in a certain way. Also pay attention to words such as how, what, when, where, and why; these words guide your attention toward specific information. (See the section in this handout titled “Key Terms” for more information.)

“Analyze the effect that gerbils had on the Russian Revolution”, or “Suggest an interpretation of housefly undergarments that differs from Darwin’s.”

Additional Material to Think about

Here you will find some questions to use as springboards as you begin to think about the topic. Instructors usually include these questions as suggestions rather than requirements. Do not feel compelled to answer every question unless the instructor asks you to do so. Pay attention to the order of the questions. Sometimes they suggest the thinking process your instructor imagines you will need to follow to begin thinking about the topic.

“You may wish to consider the differing views held by Communist gerbils vs. Monarchist gerbils, or Can there be such a thing as ‘the housefly garment industry’ or is it just a home-based craft?”

These are the instructor’s comments about writing expectations:

“Be concise”, “Write effectively”, or “Argue furiously.”

Technical Details

These instructions usually indicate format rules or guidelines.

“Your paper must be typed in Palatino font on gray paper and must not exceed 600 pages. It is due on the anniversary of Mao Tse-tung’s death.”

The assignment’s parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do.

Interpreting the assignment

Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

Why did your instructor ask you to do this particular task?

Who is your audience.

- What kind of evidence do you need to support your ideas?

What kind of writing style is acceptable?

- What are the absolute rules of the paper?

Try to look at the question from the point of view of the instructor. Recognize that your instructor has a reason for giving you this assignment and for giving it to you at a particular point in the semester. In every assignment, the instructor has a challenge for you. This challenge could be anything from demonstrating an ability to think clearly to demonstrating an ability to use the library. See the assignment not as a vague suggestion of what to do but as an opportunity to show that you can handle the course material as directed. Paper assignments give you more than a topic to discuss—they ask you to do something with the topic. Keep reminding yourself of that. Be careful to avoid the other extreme as well: do not read more into the assignment than what is there.

Of course, your instructor has given you an assignment so that they will be able to assess your understanding of the course material and give you an appropriate grade. But there is more to it than that. Your instructor has tried to design a learning experience of some kind. Your instructor wants you to think about something in a particular way for a particular reason. If you read the course description at the beginning of your syllabus, review the assigned readings, and consider the assignment itself, you may begin to see the plan, purpose, or approach to the subject matter that your instructor has created for you. If you still aren’t sure of the assignment’s goals, try asking the instructor. For help with this, see our handout on getting feedback .

Given your instructor’s efforts, it helps to answer the question: What is my purpose in completing this assignment? Is it to gather research from a variety of outside sources and present a coherent picture? Is it to take material I have been learning in class and apply it to a new situation? Is it to prove a point one way or another? Key words from the assignment can help you figure this out. Look for key terms in the form of active verbs that tell you what to do.

Key Terms: Finding Those Active Verbs

Here are some common key words and definitions to help you think about assignment terms:

Information words Ask you to demonstrate what you know about the subject, such as who, what, when, where, how, and why.

- define —give the subject’s meaning (according to someone or something). Sometimes you have to give more than one view on the subject’s meaning

- describe —provide details about the subject by answering question words (such as who, what, when, where, how, and why); you might also give details related to the five senses (what you see, hear, feel, taste, and smell)

- explain —give reasons why or examples of how something happened

- illustrate —give descriptive examples of the subject and show how each is connected with the subject

- summarize —briefly list the important ideas you learned about the subject

- trace —outline how something has changed or developed from an earlier time to its current form

- research —gather material from outside sources about the subject, often with the implication or requirement that you will analyze what you have found

Relation words Ask you to demonstrate how things are connected.

- compare —show how two or more things are similar (and, sometimes, different)

- contrast —show how two or more things are dissimilar

- apply—use details that you’ve been given to demonstrate how an idea, theory, or concept works in a particular situation

- cause —show how one event or series of events made something else happen

- relate —show or describe the connections between things

Interpretation words Ask you to defend ideas of your own about the subject. Do not see these words as requesting opinion alone (unless the assignment specifically says so), but as requiring opinion that is supported by concrete evidence. Remember examples, principles, definitions, or concepts from class or research and use them in your interpretation.

- assess —summarize your opinion of the subject and measure it against something

- prove, justify —give reasons or examples to demonstrate how or why something is the truth

- evaluate, respond —state your opinion of the subject as good, bad, or some combination of the two, with examples and reasons

- support —give reasons or evidence for something you believe (be sure to state clearly what it is that you believe)

- synthesize —put two or more things together that have not been put together in class or in your readings before; do not just summarize one and then the other and say that they are similar or different—you must provide a reason for putting them together that runs all the way through the paper

- analyze —determine how individual parts create or relate to the whole, figure out how something works, what it might mean, or why it is important

- argue —take a side and defend it with evidence against the other side

More Clues to Your Purpose As you read the assignment, think about what the teacher does in class:

- What kinds of textbooks or coursepack did your instructor choose for the course—ones that provide background information, explain theories or perspectives, or argue a point of view?

- In lecture, does your instructor ask your opinion, try to prove their point of view, or use keywords that show up again in the assignment?

- What kinds of assignments are typical in this discipline? Social science classes often expect more research. Humanities classes thrive on interpretation and analysis.

- How do the assignments, readings, and lectures work together in the course? Instructors spend time designing courses, sometimes even arguing with their peers about the most effective course materials. Figuring out the overall design to the course will help you understand what each assignment is meant to achieve.

Now, what about your reader? Most undergraduates think of their audience as the instructor. True, your instructor is a good person to keep in mind as you write. But for the purposes of a good paper, think of your audience as someone like your roommate: smart enough to understand a clear, logical argument, but not someone who already knows exactly what is going on in your particular paper. Remember, even if the instructor knows everything there is to know about your paper topic, they still have to read your paper and assess your understanding. In other words, teach the material to your reader.

Aiming a paper at your audience happens in two ways: you make decisions about the tone and the level of information you want to convey.

- Tone means the “voice” of your paper. Should you be chatty, formal, or objective? Usually you will find some happy medium—you do not want to alienate your reader by sounding condescending or superior, but you do not want to, um, like, totally wig on the man, you know? Eschew ostentatious erudition: some students think the way to sound academic is to use big words. Be careful—you can sound ridiculous, especially if you use the wrong big words.

- The level of information you use depends on who you think your audience is. If you imagine your audience as your instructor and they already know everything you have to say, you may find yourself leaving out key information that can cause your argument to be unconvincing and illogical. But you do not have to explain every single word or issue. If you are telling your roommate what happened on your favorite science fiction TV show last night, you do not say, “First a dark-haired white man of average height, wearing a suit and carrying a flashlight, walked into the room. Then a purple alien with fifteen arms and at least three eyes turned around. Then the man smiled slightly. In the background, you could hear a clock ticking. The room was fairly dark and had at least two windows that I saw.” You also do not say, “This guy found some aliens. The end.” Find some balance of useful details that support your main point.

You’ll find a much more detailed discussion of these concepts in our handout on audience .

The Grim Truth

With a few exceptions (including some lab and ethnography reports), you are probably being asked to make an argument. You must convince your audience. It is easy to forget this aim when you are researching and writing; as you become involved in your subject matter, you may become enmeshed in the details and focus on learning or simply telling the information you have found. You need to do more than just repeat what you have read. Your writing should have a point, and you should be able to say it in a sentence. Sometimes instructors call this sentence a “thesis” or a “claim.”

So, if your instructor tells you to write about some aspect of oral hygiene, you do not want to just list: “First, you brush your teeth with a soft brush and some peanut butter. Then, you floss with unwaxed, bologna-flavored string. Finally, gargle with bourbon.” Instead, you could say, “Of all the oral cleaning methods, sandblasting removes the most plaque. Therefore it should be recommended by the American Dental Association.” Or, “From an aesthetic perspective, moldy teeth can be quite charming. However, their joys are short-lived.”

Convincing the reader of your argument is the goal of academic writing. It doesn’t have to say “argument” anywhere in the assignment for you to need one. Look at the assignment and think about what kind of argument you could make about it instead of just seeing it as a checklist of information you have to present. For help with understanding the role of argument in academic writing, see our handout on argument .

What kind of evidence do you need?

There are many kinds of evidence, and what type of evidence will work for your assignment can depend on several factors–the discipline, the parameters of the assignment, and your instructor’s preference. Should you use statistics? Historical examples? Do you need to conduct your own experiment? Can you rely on personal experience? See our handout on evidence for suggestions on how to use evidence appropriately.

Make sure you are clear about this part of the assignment, because your use of evidence will be crucial in writing a successful paper. You are not just learning how to argue; you are learning how to argue with specific types of materials and ideas. Ask your instructor what counts as acceptable evidence. You can also ask a librarian for help. No matter what kind of evidence you use, be sure to cite it correctly—see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

You cannot always tell from the assignment just what sort of writing style your instructor expects. The instructor may be really laid back in class but still expect you to sound formal in writing. Or the instructor may be fairly formal in class and ask you to write a reflection paper where you need to use “I” and speak from your own experience.

Try to avoid false associations of a particular field with a style (“art historians like wacky creativity,” or “political scientists are boring and just give facts”) and look instead to the types of readings you have been given in class. No one expects you to write like Plato—just use the readings as a guide for what is standard or preferable to your instructor. When in doubt, ask your instructor about the level of formality they expect.

No matter what field you are writing for or what facts you are including, if you do not write so that your reader can understand your main idea, you have wasted your time. So make clarity your main goal. For specific help with style, see our handout on style .

Technical details about the assignment

The technical information you are given in an assignment always seems like the easy part. This section can actually give you lots of little hints about approaching the task. Find out if elements such as page length and citation format (see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial ) are negotiable. Some professors do not have strong preferences as long as you are consistent and fully answer the assignment. Some professors are very specific and will deduct big points for deviations.

Usually, the page length tells you something important: The instructor thinks the size of the paper is appropriate to the assignment’s parameters. In plain English, your instructor is telling you how many pages it should take for you to answer the question as fully as you are expected to. So if an assignment is two pages long, you cannot pad your paper with examples or reword your main idea several times. Hit your one point early, defend it with the clearest example, and finish quickly. If an assignment is ten pages long, you can be more complex in your main points and examples—and if you can only produce five pages for that assignment, you need to see someone for help—as soon as possible.

Tricks that don’t work

Your instructors are not fooled when you:

- spend more time on the cover page than the essay —graphics, cool binders, and cute titles are no replacement for a well-written paper.

- use huge fonts, wide margins, or extra spacing to pad the page length —these tricks are immediately obvious to the eye. Most instructors use the same word processor you do. They know what’s possible. Such tactics are especially damning when the instructor has a stack of 60 papers to grade and yours is the only one that low-flying airplane pilots could read.

- use a paper from another class that covered “sort of similar” material . Again, the instructor has a particular task for you to fulfill in the assignment that usually relates to course material and lectures. Your other paper may not cover this material, and turning in the same paper for more than one course may constitute an Honor Code violation . Ask the instructor—it can’t hurt.

- get all wacky and “creative” before you answer the question . Showing that you are able to think beyond the boundaries of a simple assignment can be good, but you must do what the assignment calls for first. Again, check with your instructor. A humorous tone can be refreshing for someone grading a stack of papers, but it will not get you a good grade if you have not fulfilled the task.

Critical reading of assignments leads to skills in other types of reading and writing. If you get good at figuring out what the real goals of assignments are, you are going to be better at understanding the goals of all of your classes and fields of study.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Templates for college and university assignments

Include customizable templates in your college toolbox. stay focused on your studies and leave the assignment structuring to tried and true layout templates for all kinds of papers, reports, and more..

Keep your college toolbox stocked with easy-to-use templates

Work smarter with higher-ed helpers from our college tools collection. Presentations are on point from start to finish when you start your project using a designer-created template; you'll be sure to catch and keep your professor's attention. Staying on track semester after semester takes work, but that work gets a little easier when you take control of your scheduling, list making, and planning by using trackers and planners that bring you joy. Learning good habits in college will serve you well into your professional life after graduation, so don't reinvent the wheel—use what is known to work!

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

Assignment Tracker Template For Students (Google Sheets)

- 6-minute read

- 18th May 2023

If you’re a student searching for a way to keep your assignments organized, congratulate yourself for taking the time to set yourself up for success. Tracking your assignments is one of the most important steps you can take to help you stay on top of your schoolwork .

In this Writing Tips blog post, we’ll discuss why keeping an inventory of your assignments is important, go over a few popular ways to do so, and introduce you to our student assignment tracker, which is free for you to use.

Why Tracking Is Important

Keeping your assignments organized is essential for many reasons. First off, tracking your assignments enables you to keep abreast of deadlines. In addition to risking late submission penalties that may result in low grades, meeting deadlines can help develop your work ethic and increase productivity. Staying ahead of your deadlines also helps lower stress levels and promote a healthy study-life balance.

Second, keeping track of your assignments assists with time management by helping prioritize the order you complete your projects.

Third, keeping a list of your completed projects can help you stay motivated by recording your progress and seeing how far you’ve come.

Different Ways to Organize Your Assignments

There are many ways to organize your assignment, each with its pros and cons. Here are a few tried and true methods:

- Sticky notes

Whether they are online or in real life , sticky notes are one of the most popular ways to bring attention to an important reminder. Sticky notes are a quick, easy, and effective tool to highlight time-sensitive reminders. However, they work best when used temporarily and sparingly and, therefore, are likely better used for the occasional can’t-miss deadline rather than for comprehensive assignment organization.

- Phone calendar reminders

The use of cell phone calendar reminders is also a useful approach to alert you to an upcoming deadline. An advantage to this method is that reminders on your mobile device have a good chance of grabbing your attention no matter what activity you’re involved with.

On the downside, depending on how many assignments you’re juggling, too many notifications might be overwhelming and there won’t be as much space to log the details of the assignment (e.g., related textbook pages, length requirements) as you would have in a dedicated assignment tracking system.

- Planners/apps

There are a multitude of physical planners and organization apps for students to help manage assignments and deadlines. Although some vow that physical planners reign superior and even increase focus and concentration , there is almost always a financial cost involved and the added necessity to carry around a sometimes weighty object (as well as remembering to bring it along with you).

Mobile organization apps come with a variety of features, including notifications sent to your phone, but may also require a financial investment (at least for the premium features) and generally will not provide substantial space to add details about your assignments.

- Spreadsheets

With spreadsheets, what you lose in bells and whistles, you gain in straightforwardness and customizability – and they’re often free! Spreadsheets are easy to access from your laptop or phone and can provide you with enough space to include whatever information you need to complete your assignments.

There are templates available online for several different spreadsheet programs, or you can use our student assignment tracker for Google Sheets . We’ll show you how to use it in the next section.

How to Use Our Free Writing Tips Student Assignment Tracker

Follow this step-by-step guide to use our student assignment tracker for Google Sheets :

- Click on this link to the student assignment tracker . After the prompt “Would you like to make a copy of Assignment Tracker Template ?”, click Make a copy .

Screenshot of the “Copy document” screen

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

2. The first tab in the spreadsheet will display several premade assignment trackers for individual subjects with the name of the subject in the header (e.g., Subject 1, Subject 2). In each header, fill in the title of the subjects you would like to track assignments for. Copy and paste additional assignment tracker boxes for any other subjects you’d like to track, and color code the labels.

Screenshot of the blank assignment template

3. Under each subject header, there are columns labeled for each assignment (e.g., Assignment A, Assignment B). Fill in the title of each of your assignments in one of these columns, and add additional columns if need be. Directly under the assignment title is a cell for you to fill in the due date for the assignment. Below the due date, fill in each task that needs to be accomplished to complete the assignment. In the final row of the tracker, you should select whether the status of your assignment is Not Started , In Progress , or Complete . Please see the example of a template that has been filled in (which is also available for viewing in the Example tab of the spreadsheet):

Example of completed assignment tracker

4. Finally, for an overview of all the assignments you have for each subject throughout the semester, fill out the assignment tracker in the Study Schedule tab. In this tracker, list the title of the assignment for each subject under the Assignment column, and then color code the weeks you plan to be working on each one. Add any additional columns or rows that you need. This overview is particularly helpful for time management throughout the semester.

There you have it.

To help you take full advantage of this student assignment tracker let’s recap the steps:

1. Make a copy of the student assignment tracker .

2. Fill in the title of the subjects you would like to track assignments for in each header row in the Assignments tab.

3. Fill in the title of each of your assignments and all the required tasks underneath each assignment.

4. List the title of the assignment for each subject and color code the week that the assignment is due in the Study Schedule .

Now that your assignments are organized, you can rest easy . Happy studying! And remember, if you need help from a subject-matter expert to proofread your work before submission, we’ll happily proofread it for free .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

9-minute read

How to Use Infographics to Boost Your Presentation

Is your content getting noticed? Capturing and maintaining an audience’s attention is a challenge when...

8-minute read

Why Interactive PDFs Are Better for Engagement

Are you looking to enhance engagement and captivate your audience through your professional documents? Interactive...

7-minute read

Seven Key Strategies for Voice Search Optimization

Voice search optimization is rapidly shaping the digital landscape, requiring content professionals to adapt their...

4-minute read

Five Creative Ways to Showcase Your Digital Portfolio

Are you a creative freelancer looking to make a lasting impression on potential clients or...

How to Ace Slack Messaging for Contractors and Freelancers

Effective professional communication is an important skill for contractors and freelancers navigating remote work environments....

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Introduction

Background on the Course

CO300 as a University Core Course

Short Description of the Course

Course Objectives

General Overview

Alternative Approaches and Assignments

(Possible) Differences between COCC150 and CO300

What CO300 Students Are Like

And You Thought...

Beginning with Critical Reading

Opportunities for Innovation

Portfolio Grading as an Option

Teaching in the computer classroom

Finally. . .

Classroom materials

Audience awareness and rhetorical contexts

Critical thinking and reading

Focusing and narrowing topics

Mid-course, group, and supplemental evaluations

More detailed explanation of Rogerian argument and Toulmin analysis

Policy statements and syllabi

Portfolio explanations, checklists, and postscripts

Presenting evidence and organizing arguments/counter-arguments

Research and documentation

Writing assignment sheets

Assignments for portfolio 1

Assignments for portfolio 2

Assignments for portfolio 3

Workshopping and workshop sheets

On workshopping generally

Workshop sheets for portfolio 1

Workshop sheets for portfolio 2

Workshop sheets for portfolio 3

Workshop sheets for general purposes

Sample materials grouped by instructor

Writing Assignment Sheets

Included here are the assignment sheets for most of the major writing tasks assigned by instructors in recent semesters. We include multiple samples for each essay so you can choose from a variety of prompts.

- Under "Assignments for portfolio 3," you'll find mediating/negotiating and analysis assignments.

Several instructors did not assign specific essays during the second half of the term. Rather, they introduced general rhetorical strategies in a series of short activities and then had their students define their own assignments by identifying the rhetorical context within which they wished to write and choosing the most appropriate argumentative strategy for that context.

Just a note of comfort: having taught synthesis/response and the problem-solving essay before, you are already well acquainted with the problems most of your students will face in the COCC300 essays. On the other hand, we would like to push the students beyond 100-level writing. In the exploratory essay (the COCC300 version of synthesis/response) this might mean, as Laura Thomas put it, "getting students to make the individual texts to disappear." That is, rather than asking students to represent discrete arguments in oppositional relation to each other, instead asking students to represent the complexity of the relations among different perspectives. One possible means of achieving this complexity is to ask students to consider the rhetorical context of the essays they are synthesizing and to explain how the apparent differences in perspectives might be related to the different purposes and audiences each author had in mind.

And a self-indulgent note about the persuasive essay, should you choose to assign it. As Aims defines this essay, students are asked to appeal not only to reason (a typical expectation in the academic community) but also to character, style, and emotion (rather atypical in our world). Because all appeals can be so effective in motivating people to action--toward both worthy and unworthy ends--I suggest that the weeks leading up to the persuasion essay offer a likely spot in the syllabus to talk about the ethics of argumentation, should this topic interest you. During the spring 1995 term, for example, I spent one well-received class period on the ethical nature of persuasion. Having read about audience appeals in Aims, the students and I watched a series of video clips from Branagh's Henry V , Martin Luther King's "I Have a Dream" speech, Eleanor Roosevelt's appeal to the United Nations, and one of Hitler's many vacuous presentations. After each clip, the students considered the appeals the speaker used, why those appeals were effective for his or her audience, and what end the speaker wished to achieve through his or her persuasion. Thus, without positioning myself as a morality cop, the students started thinking about how their own essays fit into larger ethical systems.

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Music Matters Blog

Inspiring Creativity

The Perfect Assignment Sheet for Piano Students

January 26, 2017 by natalie 1 Comment

Somehow I just came across this fabulous compilation of free downloadable assignment sheets that Amy Chaplin, of the Piano Pantry blog , has either created or adapted! Even though I always create custom assignment books that correlate with our practice incentive theme for the year, I absolutely love the variety of ideas that Amy incorporates into these sheets. Whether you’re looking for an assignment sheet that includes helpful theory concepts, or one that outlines technique warm-ups, or even one that is based on specific practice tips, you’re sure to find one that is just the right fit for your students and studio!

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Reader Interactions

January 26, 2017 at 8:54 am

What a lovely surprise, Natalie. Thank you! There are more to come too. I only have about 60% of the ones I’ve made uploaded at the moment but plan on finishing it in the next few weeks. Thanks for sharing!

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

Free Resources

- Amazing Photos of Deconstructed Pianos

- Financial Resources for Independent Music Teachers

- Piano Music for Left Hand

- New Free Tortoises Beginner Piano Solo with Teacher Duet

- Free Piano Music from Composer Albert Rozin

Click for more Free Resources

Product Search

Blog archives, blog categories.

Advertisers and Affiliates

RSS Feed | YouTube | Twitter | Pinterest | LinkedIn | Facebook | Email

Blog content by Natalie's Piano Studio | © 2005-2024. All Rights Reserved. Sitemap | Privacy Policy | Terms and Conditions | Advertising Opportunities

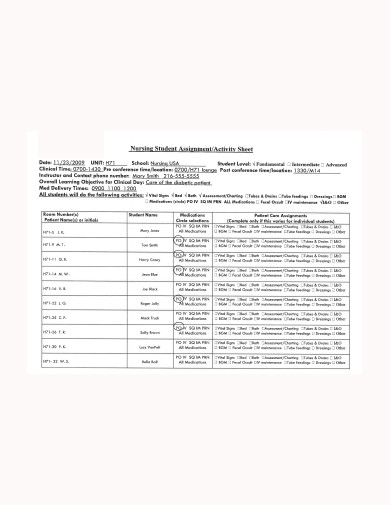

All Formats

Table of Contents

5 steps to create a nursing assignment sheet, 10+ nursing assignment sheet templates in doc | pdf, 1. nursing students assignment activity sheet template, 2. nursing students assignment sheet template, 3. nursing staffing assignment and sign in sheet template, 4. basic nursing student assignment sheet template, 5. nursing unit assignment sheet template, 6. nursing program clinical assignment sheet template, 7. nursing assignment sheet template, 8. standard nursing student assignment sheet template, 9. nursing assignment cover sheet template, 10. professional nursing assignment cover sheet template, 11. simple nursing assignment cover sheet template, sheet templates.

For assignments to be successful, you need to determine the needs of both nurses and patients. Nursing assignments, usually help to determine the daily activities of the nurses, the patient meets and assessments, coordinate different shifts and maintain a specific length of working hours. To meet this challenge of preparing nursing assignment sheets , you can take the assistance of sheet templates and learn the process eventually.

Step 1: Gather Information

Step 2: determine the process, step 3: set shift priorities, step 4: evaluating success, step 5: keep updating.

More in Sheet Templates

Simple nursing care plan template, blank nursing care plan template, nursing care plan template, nursing care emergency action plan template, nursing fact sheet template, nursing care plan smart goals template, sample nursing teaching plan template, nursing staffing plan template, clinical development plan template, nursing school lesson plan template.

- 43+ Spreadsheet Examples in Microsoft Excel

- 22+ Job Sheet Templates & Samples – DOC, PDF, Excel

- 18+ Personal Statement Worksheet Templates in PDF | DOC

- 11+ Retirement Budget Worksheet Templates in PDF | DOC

- 7+ Retirement Calculator Spreadsheet Templates in PDF | XLS

- 30+ Printable Timesheet Templates

- Bi-weekly Timesheet Template – 12+ Free Word, Excel, PDF Documents Download

- 14+ Blank Spreadsheet Templates – PDF, DOC, Pages, Excel

- 20+ Sample Answer Sheet Templates

- 10+ Earnings Per Share Templates in Google Docs | Google Sheets | Word | Excel | Numbers | Pages | PDF

- 10+ Revenue Per Employee Ratio Templates in Google Docs | Google Sheets | MS Word | Excel | Numbers | Pages | PDF

- 10+ Average Revenue Per User Templates in Google Docs | Google Sheets | Excel | Word | Numbers | Pages | PDF

- 10+ Multiple Employer Welfare Arrangement Templates in Google Docs | Google Sheets | Excel | Word | Numbers | Pages | PDF

- 10+ Marginal Revenue Templates in Google Docs | Google Sheets | Excel | Word | Pages | Numbers | PDF

- 10+ Accrued Revenue Templates in Google Docs | Google Sheets | Excel | Word | Numbers | Pages | PDF

File Formats

Word templates, google docs templates, excel templates, powerpoint templates, google sheets templates, google slides templates, pdf templates, publisher templates, psd templates, indesign templates, illustrator templates, pages templates, keynote templates, numbers templates, outlook templates.

tag manager container

- Employee Hub

- Directories

University Writing Program

- Mission Statement

- Course Description

- Assignments

- Research Tools

- Recommended Texts

- English 2000 Teachers

- Policies and Procedures

- Grade Appeals

- Policies and Procedures: Plagiarism

- Teaching Strategies

- In-Class Strategies

- Research Strategies

- Peer Response Strategies

- Important Links

- Resources | University Writing Program

For Teachers: Sample Assignments

Below are suggested assignments for English 2000, drawn from past and current syllabi of LSU instructors. You'll find resources on teaching strategies (peer response, research, and designing in-class activities) here .

Annotated Bibliography : An annotated bibliography helps students think through a research topic. In addition to bibliographical entry, each source is followed by a concise analysis of its main points. Annotations may also include a short response or a statement of potential uses for the source. These annotations are intended to be tools for students as they work on their researched argument essays; annotations should be designed to help them quickly remember how each source might be useful in their writing. How to prepare an annotated bibliography (with example) | Assignment sheets 1 | 2 (collaborative)

Argument Analysis: Analyzing an argument can work to activate the analytical skills that students learned in English 1001 and introduce them to the genre of argument. These essays can proceed according to formal traditions, such as the Toulmin model or the Rogerian Argument, or they can work from a more general analytical frame, as the assignment on the right does, to uncover assumptions, evaluate claims and evidence, and identify logical fallacies. Assignment Sheet | Toulmin Analysis

Background Essay : The background essay asks students to fully investigate their own rhetorical situation by considering (1) their purpose for writing, (2) the audience for whom they write, (3) the situation in which they are writing, and (4) the larger context of their work. More specifically, the background essay asks students to answer questions about geography, demographics, history, and culture (among other relevant factors) and articulate these factors in four-to-six pages, thus exploring the context of their writing. Assignment Sheet | Audience Analysis guide | Sample Essay and Peer Review Sheet | Rubric

Causal Argument: An argument of cause can begin with an effect and make claims about underlying causes. Alternatively, it can identify a cause and make claims about effects that will result. It might trace a chain of such causes and effects. Causal arguments rarely offer absolute or single conclusions; they are usually complex and involve a great deal of analytical thinking. Causal claims are often part of a larger argument, such as a proposal, and often rely on arguments of definition. Assignment Sheet 1 | 2 | 3 || Causal Argument Rubric

Definition Argument: The question of definition is at the heart of most arguments; it hinges on the meaning of a contested term (examples from current events include the terms citizen, enemy combatant, and marriage). Such arguments offer a definition—often one that differs from or is more developed than popular understanding—provide examples to develop it, and argue that a particular term does or does not fit that definition. Lesson + assignment | Assignment 2 || Sample essays 1 | 2 Evaluation Argument: The writer establishes criteria by which to assert a positive or negative judgment, or to argue the relative merits of two or more ideas or things. Classical arguments of evaluation (or quality) ask “is it just and expedient?” Such arguments might also assert that a thing is (or is not) useful, effective, successful, innovative, valid, important, etc. The book or film review is a popular genre of evaluative writing. Evaluation Assignment 1 | 2 || Defense of Major Assignment

Issue Analysis : In an issue analysis, students are asked to explain the debate surrounding a contested issue. Because issues involve multiple perspectives, students must locate a wide range of sources in order to present each perspective fairly and thoughtfully. The ultimate goal of an issue analysis is to introduce the debate to an uninformed audience without favoring one argument. Find assignment sheets, scoring matrices, and sample issue analysis essays on the 1001 Assessment page.

Policy Argument: Also called a “proposal argument,” this assignment asks students to suggest a solution to a problem. This form of deliberative rhetoric addresses the question, “what are we going to do?” A successful proposal argument demonstrates not only that the problem is significant enough to merit attention, but that the proposed solution is the best one. Sample Student Essay

Presentation : For the presentation, students are asked to present their analysis of an issue, text, or image to the entire class. Some teachers ask students to work collaboratively, use technology such as Power Points, or use other visual media. Group Visual Presentation Assignment | Individual Oral Presentation Assignment

*Researched Argument (required final essay): The researched argument essay should include a debatable thesis and evidence to support each claim and sub-claim as well as a discussion that anticipates and addresses alternative points of view and/or counter arguments. Students should draw on six to ten sources with topic-appropriate mix of primary and secondary sources, including some scholarly ones. Because this is the essay that will be assessed, all sections should assign it as 1500 words, plus Works Cited (MLA). Students should turn in a digital copy to teacher in MSWord format. Click here for more information on the program's assessment model. Assignment Sheet || Sample student essays 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (scored) || Peer Review Guide

Research Proposal : The research proposal is designed to help students select a topic of interest and narrow their research down to a specific question or thesis. By the end of the proposal, students should be able to articulate the ultimate goal of their research as well as construct a potential model for argument. The research proposal is best used in sequence with other research-oriented assignments, such as the background essay. Assignment sheets 1 | 2 || Sample student essays 1 | 2

Rogerian Argument: Named for psychotherapist Carl Rogers, the Rogerian argument focuses on resolving conflict by honestly considering opposing views and striving to find common ground. It offers students an alternative to the belief that the point of argument is to defeat one's opponents. The structure of this argument emphasizes understanding and concession by placing them first in the essay, followed by a statement of the writer's position. Assignment with Resources

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Sample Assignment Sheets. Check out some examples of Stanford instructors' assignment sheets via the links below. Note that these links will route you to our Canvas PWR Program Materials site, so you must have access to the Canvas page in order to view these files: See examples of rhetorical analysis assignment sheets. See examples of texts in ...

Instructors can often help students write more effective papers by giving students written instructions about that assignment. Explicit descriptions of assignments on the syllabus or on an "assignment sheet" tend to produce the best results. These instructions might make explicit the process or steps necessary to complete the assignment.

This guide will help you set up an APA Style student paper. The basic setup directions apply to the entire paper. Annotated diagrams illustrate how to set up the major sections of a student paper: the title page or cover page, the text, tables and figures, and the reference list. Basic Setup. Seventh edition APA Style was designed with modern ...

An assignment sheet is a document written for the statement of purpose of delegating or appointing a task or research and discussion on a topic or purpose. General sheet examples in doc provide further aid regarding an assignment sheet and how it is made. Just click on the download link button below the samples to access the files.

Things to Consider. While an assignment does not necessarily have to have a title (this one's a clunky mouthful), it can help students connect an individual assignment to the bigger context of the class.; Start by telling students the purpose of the assignment, connecting it to the course goals, especially the ones having to do with writing as opposed to course content.

The assignment's parts may not appear in exactly this order, and each part may be very long or really short. Nonetheless, being aware of this standard pattern can help you understand what your instructor wants you to do. Interpreting the assignment. Ask yourself a few basic questions as you read and jot down the answers on the assignment sheet:

These sample papers demonstrate APA Style formatting standards for different student paper types. Students may write the same types of papers as professional authors (e.g., quantitative studies, literature reviews) or other types of papers for course assignments (e.g., reaction or response papers, discussion posts), dissertations, and theses.

Pitfall #3: The assignment sheet lacks active verbs. This follows from #2. Notice how, in the series of questions, the assignment sheet doesn't use active verbs. It asks questions, but doesn't provide a method or approach for students to employ. In effect, it doesn't clearly define the task.

Strive for Clarity in Your Assignment Sheet. Use "active voice" commands as you write your assignment sheet. It might feel more polite to write, "You might try comparing A to B," but students need to see "Compare A to B.". Use language that your students will understand. Students may not know exactly what you want when they see ...

Designing Writing Assignments designing-assignments. As you think about creating writing assignments, use these five principles: Tie the writing task to specific pedagogical goals. Note rhetorical aspects of the task, i.e., audience, purpose, writing situation. Make all elements of the task clear. Include grading criteria on the assignment sheet.

Templates for college and university assignments. Include customizable templates in your college toolbox. Stay focused on your studies and leave the assignment structuring to tried and true layout templates for all kinds of papers, reports, and more. Category. Color. Create from scratch. Show all.

Then, checkout this Assignment sheet template to keep track of all your assignment work. In this sheet template, you can organize your projects including short terms and long terms in an organized way. Apart from that, you can create your number of assignments in correspondence to the days you would like to do your work.

PDF. Size: 26 KB. Download. A daily assignment sheet is used to track whether the student working on the assignment is all right, or whether the student's behavior is okay or not. This is tracked both by the parent and the teacher through this sheet where both parties sign on, and teacher comments on the assignment done.

Also, all our assignment templates have industry-compliant, original suggestive content. So, if you don't want your assignment of contract to sound generic, Template.net is your best source. Furthermore, our assignment templates are easy to customize in case to perfectly fit your needs. They are also ready for download and print.

1. Make a copy of the student assignment tracker. 2. Fill in the title of the subjects you would like to track assignments for in each header row in the Assignments tab. 3. Fill in the title of each of your assignments and all the required tasks underneath each assignment. 4.

Writing Assignment Sheets. Included here are the assignment sheets for most of the major writing tasks assigned by instructors in recent semesters. We include multiple samples for each essay so you can choose from a variety of prompts. Under "Assignments for portfolio 1," you'll find samples for summary, Toulmin analysis, response, summary ...

All sections of English 1001 must include an issue analysis in order to complete the end-of-semester assessment . Find assignment sheets, scoring matrices, and sample issue analysis essays in the English 1001 Teachers topic on the community moodle page. Literacy Analysis: In a literacy analysis, students are asked to reflect on the experiences ...

In this sample paper, we've put four blank lines above the title. Commented [AF3]: Authors' names are written below the title, with one double-spaced blank line between them. Names should be written as follows: First name, middle initial(s), last name. Commented [AF4]: Authors' affiliations follow immediately after their names.

The Perfect Assignment Sheet for Piano Students. January 26, 2017 by natalie 1 Comment. Somehow I just came across this fabulous compilation of free downloadable assignment sheets that Amy Chaplin, of the Piano Pantry blog, has either created or adapted! Even though I always create custom assignment books that correlate with our practice ...

Size: 352.4 KB. Download Now. Most of the nurses learn their duty during the time of assignments therefore, it's important to assign them their work as scheduled. You can do this quite easily with the assistance of the Professional Nursing Assignment Cover Sheet Template accessible in PDF file.

The ultimate goal of an issue analysis is to introduce the debate to an uninformed audience without favoring one argument. Find assignment sheets, scoring matrices, and sample issue analysis essays on the 1001 Assessment page. Policy Argument: Also called a "proposal argument," this assignment asks students to suggest a solution to a problem.

Download Free Cover Page Templates. Explore our collection of 23 beautifully designed cover page templates in Microsoft Word format. These templates feature captivating colors and layouts that are sure to make a lasting impression. Simply click on the preview image of each template and download it for free.

Excel Practice Exercises. Download our 100% fre e Excel Practice Workbook. The workbook contains 50+ automatically graded exercises. Each exercise is preceeded by corresponding lessons and examples. Download.