Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- How it works

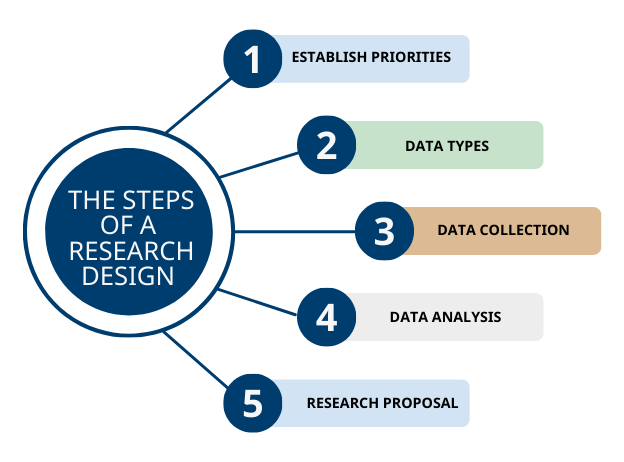

How to Write a Research Design – Guide with Examples

Published by Alaxendra Bets at August 14th, 2021 , Revised On October 3, 2023

A research design is a structure that combines different components of research. It involves the use of different data collection and data analysis techniques logically to answer the research questions .

It would be best to make some decisions about addressing the research questions adequately before starting the research process, which is achieved with the help of the research design.

Below are the key aspects of the decision-making process:

- Data type required for research

- Research resources

- Participants required for research

- Hypothesis based upon research question(s)

- Data analysis methodologies

- Variables (Independent, dependent, and confounding)

- The location and timescale for conducting the data

- The time period required for research

The research design provides the strategy of investigation for your project. Furthermore, it defines the parameters and criteria to compile the data to evaluate results and conclude.

Your project’s validity depends on the data collection and interpretation techniques. A strong research design reflects a strong dissertation , scientific paper, or research proposal .

Step 1: Establish Priorities for Research Design

Before conducting any research study, you must address an important question: “how to create a research design.”

The research design depends on the researcher’s priorities and choices because every research has different priorities. For a complex research study involving multiple methods, you may choose to have more than one research design.

Multimethodology or multimethod research includes using more than one data collection method or research in a research study or set of related studies.

If one research design is weak in one area, then another research design can cover that weakness. For instance, a dissertation analyzing different situations or cases will have more than one research design.

For example:

- Experimental research involves experimental investigation and laboratory experience, but it does not accurately investigate the real world.

- Quantitative research is good for the statistical part of the project, but it may not provide an in-depth understanding of the topic .

- Also, correlational research will not provide experimental results because it is a technique that assesses the statistical relationship between two variables.

While scientific considerations are a fundamental aspect of the research design, It is equally important that the researcher think practically before deciding on its structure. Here are some questions that you should think of;

- Do you have enough time to gather data and complete the write-up?

- Will you be able to collect the necessary data by interviewing a specific person or visiting a specific location?

- Do you have in-depth knowledge about the different statistical analysis and data collection techniques to address the research questions or test the hypothesis ?

If you think that the chosen research design cannot answer the research questions properly, you can refine your research questions to gain better insight.

Step 2: Data Type you Need for Research

Decide on the type of data you need for your research. The type of data you need to collect depends on your research questions or research hypothesis. Two types of research data can be used to answer the research questions:

Primary Data Vs. Secondary Data

Qualitative vs. quantitative data.

Also, see; Research methods, design, and analysis .

Need help with a thesis chapter?

- Hire an expert from ResearchProspect today!

- Statistical analysis, research methodology, discussion of the results or conclusion – our experts can help you no matter how complex the requirements are.

Step 3: Data Collection Techniques

Once you have selected the type of research to answer your research question, you need to decide where and how to collect the data.

It is time to determine your research method to address the research problem . Research methods involve procedures, techniques, materials, and tools used for the study.

For instance, a dissertation research design includes the different resources and data collection techniques and helps establish your dissertation’s structure .

The following table shows the characteristics of the most popularly employed research methods.

Research Methods

Step 4: Procedure of Data Analysis

Use of the correct data and statistical analysis technique is necessary for the validity of your research. Therefore, you need to be certain about the data type that would best address the research problem. Choosing an appropriate analysis method is the final step for the research design. It can be split into two main categories;

Quantitative Data Analysis

The quantitative data analysis technique involves analyzing the numerical data with the help of different applications such as; SPSS, STATA, Excel, origin lab, etc.

This data analysis strategy tests different variables such as spectrum, frequencies, averages, and more. The research question and the hypothesis must be established to identify the variables for testing.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative data analysis of figures, themes, and words allows for flexibility and the researcher’s subjective opinions. This means that the researcher’s primary focus will be interpreting patterns, tendencies, and accounts and understanding the implications and social framework.

You should be clear about your research objectives before starting to analyze the data. For example, you should ask yourself whether you need to explain respondents’ experiences and insights or do you also need to evaluate their responses with reference to a certain social framework.

Step 5: Write your Research Proposal

The research design is an important component of a research proposal because it plans the project’s execution. You can share it with the supervisor, who would evaluate the feasibility and capacity of the results and conclusion .

Read our guidelines to write a research proposal if you have already formulated your research design. The research proposal is written in the future tense because you are writing your proposal before conducting research.

The research methodology or research design, on the other hand, is generally written in the past tense.

How to Write a Research Design – Conclusion

A research design is the plan, structure, strategy of investigation conceived to answer the research question and test the hypothesis. The dissertation research design can be classified based on the type of data and the type of analysis.

Above mentioned five steps are the answer to how to write a research design. So, follow these steps to formulate the perfect research design for your dissertation .

ResearchProspect writers have years of experience creating research designs that align with the dissertation’s aim and objectives. If you are struggling with your dissertation methodology chapter, you might want to look at our dissertation part-writing service.

Our dissertation writers can also help you with the full dissertation paper . No matter how urgent or complex your need may be, ResearchProspect can help. We also offer PhD level research paper writing services.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is research design.

Research design is a systematic plan that guides the research process, outlining the methodology and procedures for collecting and analysing data. It determines the structure of the study, ensuring the research question is answered effectively, reliably, and validly. It serves as the blueprint for the entire research project.

How to write a research design?

To write a research design, define your research question, identify the research method (qualitative, quantitative, or mixed), choose data collection techniques (e.g., surveys, interviews), determine the sample size and sampling method, outline data analysis procedures, and highlight potential limitations and ethical considerations for the study.

How to write the design section of a research paper?

In the design section of a research paper, describe the research methodology chosen and justify its selection. Outline the data collection methods, participants or samples, instruments used, and procedures followed. Detail any experimental controls, if applicable. Ensure clarity and precision to enable replication of the study by other researchers.

How to write a research design in methodology?

To write a research design in methodology, clearly outline the research strategy (e.g., experimental, survey, case study). Describe the sampling technique, participants, and data collection methods. Detail the procedures for data collection and analysis. Justify choices by linking them to research objectives, addressing reliability and validity.

You May Also Like

Repository of ten perfect research question examples will provide you a better perspective about how to create research questions.

How to write a hypothesis for dissertation,? A hypothesis is a statement that can be tested with the help of experimental or theoretical research.

Make sure that your selected topic is intriguing, manageable, and relevant. Here are some guidelines to help understand how to find a good dissertation topic.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 31 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and Templates

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and Templates

Table of Contents

Research paper format is an essential aspect of academic writing that plays a crucial role in the communication of research findings . The format of a research paper depends on various factors such as the discipline, style guide, and purpose of the research. It includes guidelines for the structure, citation style, referencing , and other elements of the paper that contribute to its overall presentation and coherence. Adhering to the appropriate research paper format is vital for ensuring that the research is accurately and effectively communicated to the intended audience. In this era of information, it is essential to understand the different research paper formats and their guidelines to communicate research effectively, accurately, and with the required level of detail. This post aims to provide an overview of some of the common research paper formats used in academic writing.

Research Paper Formats

Research Paper Formats are as follows:

- APA (American Psychological Association) format

- MLA (Modern Language Association) format

- Chicago/Turabian style

- IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) format

- AMA (American Medical Association) style

- Harvard style

- Vancouver style

- ACS (American Chemical Society) style

- ASA (American Sociological Association) style

- APSA (American Political Science Association) style

APA (American Psychological Association) Format

Here is a general APA format for a research paper:

- Title Page: The title page should include the title of your paper, your name, and your institutional affiliation. It should also include a running head, which is a shortened version of the title, and a page number in the upper right-hand corner.

- Abstract : The abstract is a brief summary of your paper, typically 150-250 words. It should include the purpose of your research, the main findings, and any implications or conclusions that can be drawn.

- Introduction: The introduction should provide background information on your topic, state the purpose of your research, and present your research question or hypothesis. It should also include a brief literature review that discusses previous research on your topic.

- Methods: The methods section should describe the procedures you used to collect and analyze your data. It should include information on the participants, the materials and instruments used, and the statistical analyses performed.

- Results: The results section should present the findings of your research in a clear and concise manner. Use tables and figures to help illustrate your results.

- Discussion : The discussion section should interpret your results and relate them back to your research question or hypothesis. It should also discuss the implications of your findings and any limitations of your study.

- References : The references section should include a list of all sources cited in your paper. Follow APA formatting guidelines for your citations and references.

Some additional tips for formatting your APA research paper:

- Use 12-point Times New Roman font throughout the paper.

- Double-space all text, including the references.

- Use 1-inch margins on all sides of the page.

- Indent the first line of each paragraph by 0.5 inches.

- Use a hanging indent for the references (the first line should be flush with the left margin, and all subsequent lines should be indented).

- Number all pages, including the title page and references page, in the upper right-hand corner.

APA Research Paper Format Template

APA Research Paper Format Template is as follows:

Title Page:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Institutional affiliation

- A brief summary of the main points of the paper, including the research question, methods, findings, and conclusions. The abstract should be no more than 250 words.

Introduction:

- Background information on the topic of the research paper

- Research question or hypothesis

- Significance of the study

- Overview of the research methods and design

- Brief summary of the main findings

- Participants: description of the sample population, including the number of participants and their characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, etc.)

- Materials: description of any materials used in the study (e.g., survey questions, experimental apparatus)

- Procedure: detailed description of the steps taken to conduct the study

- Presentation of the findings of the study, including statistical analyses if applicable

- Tables and figures may be included to illustrate the results

Discussion:

- Interpretation of the results in light of the research question and hypothesis

- Implications of the study for the field

- Limitations of the study

- Suggestions for future research

References:

- A list of all sources cited in the paper, in APA format

Formatting guidelines:

- Double-spaced

- 12-point font (Times New Roman or Arial)

- 1-inch margins on all sides

- Page numbers in the top right corner

- Headings and subheadings should be used to organize the paper

- The first line of each paragraph should be indented

- Quotations of 40 or more words should be set off in a block quote with no quotation marks

- In-text citations should include the author’s last name and year of publication (e.g., Smith, 2019)

APA Research Paper Format Example

APA Research Paper Format Example is as follows:

The Effects of Social Media on Mental Health

University of XYZ

This study examines the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students. Data was collected through a survey of 500 students at the University of XYZ. Results suggest that social media use is significantly related to symptoms of depression and anxiety, and that the negative effects of social media are greater among frequent users.

Social media has become an increasingly important aspect of modern life, especially among young adults. While social media can have many positive effects, such as connecting people across distances and sharing information, there is growing concern about its impact on mental health. This study aims to examine the relationship between social media use and mental health among college students.

Participants: Participants were 500 college students at the University of XYZ, recruited through online advertisements and flyers posted on campus. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 25, with a mean age of 20.5 years. The sample was 60% female, 40% male, and 5% identified as non-binary or gender non-conforming.

Data was collected through an online survey administered through Qualtrics. The survey consisted of several measures, including the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) for depression symptoms, the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) for anxiety symptoms, and questions about social media use.

Procedure :

Participants were asked to complete the online survey at their convenience. The survey took approximately 20-30 minutes to complete. Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics, correlations, and multiple regression analysis.

Results indicated that social media use was significantly related to symptoms of depression (r = .32, p < .001) and anxiety (r = .29, p < .001). Regression analysis indicated that frequency of social media use was a significant predictor of both depression symptoms (β = .24, p < .001) and anxiety symptoms (β = .20, p < .001), even when controlling for age, gender, and other relevant factors.

The results of this study suggest that social media use is associated with symptoms of depression and anxiety among college students. The negative effects of social media are greater among frequent users. These findings have important implications for mental health professionals and educators, who should consider addressing the potential negative effects of social media use in their work with young adults.

References :

References should be listed in alphabetical order according to the author’s last name. For example:

- Chou, H. T. G., & Edge, N. (2012). “They are happier and having better lives than I am”: The impact of using Facebook on perceptions of others’ lives. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15(2), 117-121.

- Twenge, J. M., Joiner, T. E., Rogers, M. L., & Martin, G. N. (2018). Increases in depressive symptoms, suicide-related outcomes, and suicide rates among U.S. adolescents after 2010 and links to increased new media screen time. Clinical Psychological Science, 6(1), 3-17.

Note: This is just a sample Example do not use this in your assignment.

MLA (Modern Language Association) Format

MLA (Modern Language Association) Format is as follows:

- Page Layout : Use 8.5 x 11-inch white paper, with 1-inch margins on all sides. The font should be 12-point Times New Roman or a similar serif font.

- Heading and Title : The first page of your research paper should include a heading and a title. The heading should include your name, your instructor’s name, the course title, and the date. The title should be centered and in title case (capitalizing the first letter of each important word).

- In-Text Citations : Use parenthetical citations to indicate the source of your information. The citation should include the author’s last name and the page number(s) of the source. For example: (Smith 23).

- Works Cited Page : At the end of your paper, include a Works Cited page that lists all the sources you used in your research. Each entry should include the author’s name, the title of the work, the publication information, and the medium of publication.

- Formatting Quotations : Use double quotation marks for short quotations and block quotations for longer quotations. Indent the entire quotation five spaces from the left margin.

- Formatting the Body : Use a clear and readable font and double-space your text throughout. The first line of each paragraph should be indented one-half inch from the left margin.

MLA Research Paper Template

MLA Research Paper Format Template is as follows:

- Use 8.5 x 11 inch white paper.

- Use a 12-point font, such as Times New Roman.

- Use double-spacing throughout the entire paper, including the title page and works cited page.

- Set the margins to 1 inch on all sides.

- Use page numbers in the upper right corner, beginning with the first page of text.

- Include a centered title for the research paper, using title case (capitalizing the first letter of each important word).

- Include your name, instructor’s name, course name, and date in the upper left corner, double-spaced.

In-Text Citations

- When quoting or paraphrasing information from sources, include an in-text citation within the text of your paper.

- Use the author’s last name and the page number in parentheses at the end of the sentence, before the punctuation mark.

- If the author’s name is mentioned in the sentence, only include the page number in parentheses.

Works Cited Page

- List all sources cited in alphabetical order by the author’s last name.

- Each entry should include the author’s name, title of the work, publication information, and medium of publication.

- Use italics for book and journal titles, and quotation marks for article and chapter titles.

- For online sources, include the date of access and the URL.

Here is an example of how the first page of a research paper in MLA format should look:

Headings and Subheadings

- Use headings and subheadings to organize your paper and make it easier to read.

- Use numerals to number your headings and subheadings (e.g. 1, 2, 3), and capitalize the first letter of each word.

- The main heading should be centered and in boldface type, while subheadings should be left-aligned and in italics.

- Use only one space after each period or punctuation mark.

- Use quotation marks to indicate direct quotes from a source.

- If the quote is more than four lines, format it as a block quote, indented one inch from the left margin and without quotation marks.

- Use ellipses (…) to indicate omitted words from a quote, and brackets ([…]) to indicate added words.

Works Cited Examples

- Book: Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Publisher, Publication Year.

- Journal Article: Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, volume number, issue number, publication date, page numbers.

- Website: Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Title of Website, publication date, URL. Accessed date.

Here is an example of how a works cited entry for a book should look:

Smith, John. The Art of Writing Research Papers. Penguin, 2021.

MLA Research Paper Example

MLA Research Paper Format Example is as follows:

Your Professor’s Name

Course Name and Number

Date (in Day Month Year format)

Word Count (not including title page or Works Cited)

Title: The Impact of Video Games on Aggression Levels

Video games have become a popular form of entertainment among people of all ages. However, the impact of video games on aggression levels has been a subject of debate among scholars and researchers. While some argue that video games promote aggression and violent behavior, others argue that there is no clear link between video games and aggression levels. This research paper aims to explore the impact of video games on aggression levels among young adults.

Background:

The debate on the impact of video games on aggression levels has been ongoing for several years. According to the American Psychological Association, exposure to violent media, including video games, can increase aggression levels in children and adolescents. However, some researchers argue that there is no clear evidence to support this claim. Several studies have been conducted to examine the impact of video games on aggression levels, but the results have been mixed.

Methodology:

This research paper used a quantitative research approach to examine the impact of video games on aggression levels among young adults. A sample of 100 young adults between the ages of 18 and 25 was selected for the study. The participants were asked to complete a questionnaire that measured their aggression levels and their video game habits.

The results of the study showed that there was a significant correlation between video game habits and aggression levels among young adults. The participants who reported playing violent video games for more than 5 hours per week had higher aggression levels than those who played less than 5 hours per week. The study also found that male participants were more likely to play violent video games and had higher aggression levels than female participants.

The findings of this study support the claim that video games can increase aggression levels among young adults. However, it is important to note that the study only examined the impact of video games on aggression levels and did not take into account other factors that may contribute to aggressive behavior. It is also important to note that not all video games promote violence and aggression, and some games may have a positive impact on cognitive and social skills.

Conclusion :

In conclusion, this research paper provides evidence to support the claim that video games can increase aggression levels among young adults. However, it is important to conduct further research to examine the impact of video games on other aspects of behavior and to explore the potential benefits of video games. Parents and educators should be aware of the potential impact of video games on aggression levels and should encourage young adults to engage in a variety of activities that promote cognitive and social skills.

Works Cited:

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Violent Video Games: Myths, Facts, and Unanswered Questions. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2017/08/violent-video-games

- Ferguson, C. J. (2015). Do Angry Birds make for angry children? A meta-analysis of video game influences on children’s and adolescents’ aggression, mental health, prosocial behavior, and academic performance. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(5), 646-666.

- Gentile, D. A., Swing, E. L., Lim, C. G., & Khoo, A. (2012). Video game playing, attention problems, and impulsiveness: Evidence of bidirectional causality. Psychology of Popular Media Culture, 1(1), 62-70.

- Greitemeyer, T. (2014). Effects of prosocial video games on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 530-548.

Chicago/Turabian Style

Chicago/Turabian Formate is as follows:

- Margins : Use 1-inch margins on all sides of the paper.

- Font : Use a readable font such as Times New Roman or Arial, and use a 12-point font size.

- Page numbering : Number all pages in the upper right-hand corner, beginning with the first page of text. Use Arabic numerals.

- Title page: Include a title page with the title of the paper, your name, course title and number, instructor’s name, and the date. The title should be centered on the page and in title case (capitalize the first letter of each word).

- Headings: Use headings to organize your paper. The first level of headings should be centered and in boldface or italics. The second level of headings should be left-aligned and in boldface or italics. Use as many levels of headings as necessary to organize your paper.

- In-text citations : Use footnotes or endnotes to cite sources within the text of your paper. The first citation for each source should be a full citation, and subsequent citations can be shortened. Use superscript numbers to indicate footnotes or endnotes.

- Bibliography : Include a bibliography at the end of your paper, listing all sources cited in your paper. The bibliography should be in alphabetical order by the author’s last name, and each entry should include the author’s name, title of the work, publication information, and date of publication.

- Formatting of quotations: Use block quotations for quotations that are longer than four lines. Indent the entire quotation one inch from the left margin, and do not use quotation marks. Single-space the quotation, and double-space between paragraphs.

- Tables and figures: Use tables and figures to present data and illustrations. Number each table and figure sequentially, and provide a brief title for each. Place tables and figures as close as possible to the text that refers to them.

- Spelling and grammar : Use correct spelling and grammar throughout your paper. Proofread carefully for errors.

Chicago/Turabian Research Paper Template

Chicago/Turabian Research Paper Template is as folows:

Title of Paper

Name of Student

Professor’s Name

I. Introduction

A. Background Information

B. Research Question

C. Thesis Statement

II. Literature Review

A. Overview of Existing Literature

B. Analysis of Key Literature

C. Identification of Gaps in Literature

III. Methodology

A. Research Design

B. Data Collection

C. Data Analysis

IV. Results

A. Presentation of Findings

B. Analysis of Findings

C. Discussion of Implications

V. Conclusion

A. Summary of Findings

B. Implications for Future Research

C. Conclusion

VI. References

A. Bibliography

B. In-Text Citations

VII. Appendices (if necessary)

A. Data Tables

C. Additional Supporting Materials

Chicago/Turabian Research Paper Example

Title: The Impact of Social Media on Political Engagement

Name: John Smith

Class: POLS 101

Professor: Dr. Jane Doe

Date: April 8, 2023

I. Introduction:

Social media has become an integral part of our daily lives. People use social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to connect with friends and family, share their opinions, and stay informed about current events. With the rise of social media, there has been a growing interest in understanding its impact on various aspects of society, including political engagement. In this paper, I will examine the relationship between social media use and political engagement, specifically focusing on how social media influences political participation and political attitudes.

II. Literature Review:

There is a growing body of literature on the impact of social media on political engagement. Some scholars argue that social media has a positive effect on political participation by providing new channels for political communication and mobilization (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996; Putnam, 2000). Others, however, suggest that social media can have a negative impact on political engagement by creating filter bubbles that reinforce existing beliefs and discourage political dialogue (Pariser, 2011; Sunstein, 2001).

III. Methodology:

To examine the relationship between social media use and political engagement, I conducted a survey of 500 college students. The survey included questions about social media use, political participation, and political attitudes. The data was analyzed using descriptive statistics and regression analysis.

Iv. Results:

The results of the survey indicate that social media use is positively associated with political participation. Specifically, respondents who reported using social media to discuss politics were more likely to have participated in a political campaign, attended a political rally, or contacted a political representative. Additionally, social media use was found to be associated with more positive attitudes towards political engagement, such as increased trust in government and belief in the effectiveness of political action.

V. Conclusion:

The findings of this study suggest that social media has a positive impact on political engagement, by providing new opportunities for political communication and mobilization. However, there is also a need for caution, as social media can also create filter bubbles that reinforce existing beliefs and discourage political dialogue. Future research should continue to explore the complex relationship between social media and political engagement, and develop strategies to harness the potential benefits of social media while mitigating its potential negative effects.

Vii. References:

- Delli Carpini, M. X., & Keeter, S. (1996). What Americans know about politics and why it matters. Yale University Press.

- Pariser, E. (2011). The filter bubble: What the Internet is hiding from you. Penguin.

- Putnam, R. D. (2000). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Simon & Schuster.

- Sunstein, C. R. (2001). Republic.com. Princeton University Press.

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Format

IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers) Research Paper Format is as follows:

- Title : A concise and informative title that accurately reflects the content of the paper.

- Abstract : A brief summary of the paper, typically no more than 250 words, that includes the purpose of the study, the methods used, the key findings, and the main conclusions.

- Introduction : An overview of the background, context, and motivation for the research, including a clear statement of the problem being addressed and the objectives of the study.

- Literature review: A critical analysis of the relevant research and scholarship on the topic, including a discussion of any gaps or limitations in the existing literature.

- Methodology : A detailed description of the methods used to collect and analyze data, including any experiments or simulations, data collection instruments or procedures, and statistical analyses.

- Results : A clear and concise presentation of the findings, including any relevant tables, graphs, or figures.

- Discussion : A detailed interpretation of the results, including a comparison of the findings with previous research, a discussion of the implications of the results, and any recommendations for future research.

- Conclusion : A summary of the key findings and main conclusions of the study.

- References : A list of all sources cited in the paper, formatted according to IEEE guidelines.

In addition to these elements, an IEEE research paper should also follow certain formatting guidelines, including using 12-point font, double-spaced text, and numbered headings and subheadings. Additionally, any tables, figures, or equations should be clearly labeled and referenced in the text.

AMA (American Medical Association) Style

AMA (American Medical Association) Style Research Paper Format:

- Title Page: This page includes the title of the paper, the author’s name, institutional affiliation, and any acknowledgments or disclaimers.

- Abstract: The abstract is a brief summary of the paper that outlines the purpose, methods, results, and conclusions of the study. It is typically limited to 250 words or less.

- Introduction: The introduction provides a background of the research problem, defines the research question, and outlines the objectives and hypotheses of the study.

- Methods: The methods section describes the research design, participants, procedures, and instruments used to collect and analyze data.

- Results: The results section presents the findings of the study in a clear and concise manner, using graphs, tables, and charts where appropriate.

- Discussion: The discussion section interprets the results, explains their significance, and relates them to previous research in the field.

- Conclusion: The conclusion summarizes the main points of the paper, discusses the implications of the findings, and suggests future research directions.

- References: The reference list includes all sources cited in the paper, listed in alphabetical order by author’s last name.

In addition to these sections, the AMA format requires that authors follow specific guidelines for citing sources in the text and formatting their references. The AMA style uses a superscript number system for in-text citations and provides specific formats for different types of sources, such as books, journal articles, and websites.

Harvard Style

Harvard Style Research Paper format is as follows:

- Title page: This should include the title of your paper, your name, the name of your institution, and the date of submission.

- Abstract : This is a brief summary of your paper, usually no more than 250 words. It should outline the main points of your research and highlight your findings.

- Introduction : This section should introduce your research topic, provide background information, and outline your research question or thesis statement.

- Literature review: This section should review the relevant literature on your topic, including previous research studies, academic articles, and other sources.

- Methodology : This section should describe the methods you used to conduct your research, including any data collection methods, research instruments, and sampling techniques.

- Results : This section should present your findings in a clear and concise manner, using tables, graphs, and other visual aids if necessary.

- Discussion : This section should interpret your findings and relate them to the broader research question or thesis statement. You should also discuss the implications of your research and suggest areas for future study.

- Conclusion : This section should summarize your main findings and provide a final statement on the significance of your research.

- References : This is a list of all the sources you cited in your paper, presented in alphabetical order by author name. Each citation should include the author’s name, the title of the source, the publication date, and other relevant information.

In addition to these sections, a Harvard Style research paper may also include a table of contents, appendices, and other supplementary materials as needed. It is important to follow the specific formatting guidelines provided by your instructor or academic institution when preparing your research paper in Harvard Style.

Vancouver Style

Vancouver Style Research Paper format is as follows:

The Vancouver citation style is commonly used in the biomedical sciences and is known for its use of numbered references. Here is a basic format for a research paper using the Vancouver citation style:

- Title page: Include the title of your paper, your name, the name of your institution, and the date.

- Abstract : This is a brief summary of your research paper, usually no more than 250 words.

- Introduction : Provide some background information on your topic and state the purpose of your research.

- Methods : Describe the methods you used to conduct your research, including the study design, data collection, and statistical analysis.

- Results : Present your findings in a clear and concise manner, using tables and figures as needed.

- Discussion : Interpret your results and explain their significance. Also, discuss any limitations of your study and suggest directions for future research.

- References : List all of the sources you cited in your paper in numerical order. Each reference should include the author’s name, the title of the article or book, the name of the journal or publisher, the year of publication, and the page numbers.

ACS (American Chemical Society) Style

ACS (American Chemical Society) Style Research Paper format is as follows:

The American Chemical Society (ACS) Style is a citation style commonly used in chemistry and related fields. When formatting a research paper in ACS Style, here are some guidelines to follow:

- Paper Size and Margins : Use standard 8.5″ x 11″ paper with 1-inch margins on all sides.

- Font: Use a 12-point serif font (such as Times New Roman) for the main text. The title should be in bold and a larger font size.

- Title Page : The title page should include the title of the paper, the authors’ names and affiliations, and the date of submission. The title should be centered on the page and written in bold font. The authors’ names should be centered below the title, followed by their affiliations and the date.

- Abstract : The abstract should be a brief summary of the paper, no more than 250 words. It should be on a separate page and include the title of the paper, the authors’ names and affiliations, and the text of the abstract.

- Main Text : The main text should be organized into sections with headings that clearly indicate the content of each section. The introduction should provide background information and state the research question or hypothesis. The methods section should describe the procedures used in the study. The results section should present the findings of the study, and the discussion section should interpret the results and provide conclusions.

- References: Use the ACS Style guide to format the references cited in the paper. In-text citations should be numbered sequentially throughout the text and listed in numerical order at the end of the paper.

- Figures and Tables: Figures and tables should be numbered sequentially and referenced in the text. Each should have a descriptive caption that explains its content. Figures should be submitted in a high-quality electronic format.

- Supporting Information: Additional information such as data, graphs, and videos may be included as supporting information. This should be included in a separate file and referenced in the main text.

- Acknowledgments : Acknowledge any funding sources or individuals who contributed to the research.

ASA (American Sociological Association) Style

ASA (American Sociological Association) Style Research Paper format is as follows:

- Title Page: The title page of an ASA style research paper should include the title of the paper, the author’s name, and the institutional affiliation. The title should be centered and should be in title case (the first letter of each major word should be capitalized).

- Abstract: An abstract is a brief summary of the paper that should appear on a separate page immediately following the title page. The abstract should be no more than 200 words in length and should summarize the main points of the paper.

- Main Body: The main body of the paper should begin on a new page following the abstract page. The paper should be double-spaced, with 1-inch margins on all sides, and should be written in 12-point Times New Roman font. The main body of the paper should include an introduction, a literature review, a methodology section, results, and a discussion.

- References : The reference section should appear on a separate page at the end of the paper. All sources cited in the paper should be listed in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. Each reference should include the author’s name, the title of the work, the publication information, and the date of publication.

- Appendices : Appendices are optional and should only be included if they contain information that is relevant to the study but too lengthy to be included in the main body of the paper. If you include appendices, each one should be labeled with a letter (e.g., Appendix A, Appendix B, etc.) and should be referenced in the main body of the paper.

APSA (American Political Science Association) Style

APSA (American Political Science Association) Style Research Paper format is as follows:

- Title Page: The title page should include the title of the paper, the author’s name, the name of the course or instructor, and the date.

- Abstract : An abstract is typically not required in APSA style papers, but if one is included, it should be brief and summarize the main points of the paper.

- Introduction : The introduction should provide an overview of the research topic, the research question, and the main argument or thesis of the paper.

- Literature Review : The literature review should summarize the existing research on the topic and provide a context for the research question.

- Methods : The methods section should describe the research methods used in the paper, including data collection and analysis.

- Results : The results section should present the findings of the research.

- Discussion : The discussion section should interpret the results and connect them back to the research question and argument.

- Conclusion : The conclusion should summarize the main findings and implications of the research.

- References : The reference list should include all sources cited in the paper, formatted according to APSA style guidelines.

In-text citations in APSA style use parenthetical citation, which includes the author’s last name, publication year, and page number(s) if applicable. For example, (Smith 2010, 25).

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Paper Title – Writing Guide and Example

Research Paper Introduction – Writing Guide and...

Research Paper Conclusion – Writing Guide and...

Illustration by James Round

How to plan a research project

Whether for a paper or a thesis, define your question, review the work of others – and leave yourself open to discovery.

by Brooke Harrington + BIO

is professor of sociology at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. Her research has won international awards both for scholarly quality and impact on public life. She has published dozens of articles and three books, most recently the bestseller Capital without Borders (2016), now translated into five languages.

Edited by Sam Haselby

Need to know

‘When curiosity turns to serious matters, it’s called research.’ – From Aphorisms (1880-1905) by Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach