- Privacy Policy

Home » Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Table of Contents – Types, Formats, Examples

Table of Contents

Definition:

Table of contents (TOC) is a list of the headings or sections in a document or book, arranged in the order in which they appear. It serves as a roadmap or guide to the contents of the document, allowing readers to quickly find specific information they are looking for.

A typical table of contents includes chapter titles, section headings, subheadings, and their corresponding page numbers.

The table of contents is usually located at the beginning of the document or book, after the title page and any front matter, such as a preface or introduction.

Table of Contents in Research

In Research, A Table of Contents (TOC) is a structured list of the main sections or chapters of a research paper , Thesis and Dissertation . It provides readers with an overview of the organization and structure of the document, allowing them to quickly locate specific information and navigate through the document.

Importance of Table of Contents

Here are some reasons why a TOC is important:

- Navigation : It serves as a roadmap that helps readers navigate the document easily. By providing a clear and concise overview of the contents, readers can quickly locate the section they need to read without having to search through the entire document.

- Organization : A well-structured TOC reflects the organization of the document. It helps to organize the content logically and categorize it into easily digestible chunks, which makes it easier for readers to understand and follow.

- Clarity : It can help to clarify the document’s purpose, scope, and structure. It provides an overview of the document’s main topics and subtopics, which can help readers to understand the content’s overall message.

- Efficiency : This can save readers time and effort by allowing them to skip to the section they need to read, rather than having to go through the entire document.

- Professionalism : Including a Table of Contents in a document shows that the author has taken the time and effort to organize the content properly. It adds a level of professionalism and credibility to the document.

Types of Table of Contents

There are different types of table of contents depending on the purpose and structure of the document. Here are some examples:

Simple Table of Contents

This is a basic table of contents that lists the major sections or chapters of a document along with their corresponding page numbers.

Example: Table of Contents

I. Introduction …………………………………………. 1

II. Literature Review ………………………………… 3

III. Methodology ……………………………………… 6

IV. Results …………………………………………….. 9

V. Discussion …………………………………………. 12

VI. Conclusion ……………………………………….. 15

Expanded Table of Contents

This type of table of contents provides more detailed information about the contents of each section or chapter, including subsections and subheadings.

A. Background …………………………………….. 1

B. Problem Statement ………………………….. 2

C. Research Questions ……………………….. 3

II. Literature Review ………………………………… 5

A. Theoretical Framework …………………… 5

B. Previous Research ………………………….. 6

C. Gaps and Limitations ……………………… 8 I

II. Methodology ……………………………………… 11

A. Research Design ……………………………. 11

B. Data Collection …………………………….. 12

C. Data Analysis ……………………………….. 13

IV. Results …………………………………………….. 15

A. Descriptive Statistics ……………………… 15

B. Hypothesis Testing …………………………. 17

V. Discussion …………………………………………. 20

A. Interpretation of Findings ……………… 20

B. Implications for Practice ………………… 22

VI. Conclusion ……………………………………….. 25

A. Summary of Findings ……………………… 25

B. Contributions and Recommendations ….. 27

Graphic Table of Contents

This type of table of contents uses visual aids, such as icons or images, to represent the different sections or chapters of a document.

I. Introduction …………………………………………. [image of a light bulb]

II. Literature Review ………………………………… [image of a book]

III. Methodology ……………………………………… [image of a microscope]

IV. Results …………………………………………….. [image of a graph]

V. Discussion …………………………………………. [image of a conversation bubble]

Alphabetical Table of Contents

This type of table of contents lists the different topics or keywords in alphabetical order, along with their corresponding page numbers.

A. Abstract ……………………………………………… 1

B. Background …………………………………………. 3

C. Conclusion …………………………………………. 10

D. Data Analysis …………………………………….. 8

E. Ethics ……………………………………………….. 6

F. Findings ……………………………………………… 7

G. Introduction ……………………………………….. 1

H. Hypothesis ………………………………………….. 5

I. Literature Review ………………………………… 2

J. Methodology ……………………………………… 4

K. Limitations …………………………………………. 9

L. Results ………………………………………………… 7

M. Discussion …………………………………………. 10

Hierarchical Table of Contents

This type of table of contents displays the different levels of headings and subheadings in a hierarchical order, indicating the relative importance and relationship between the different sections.

A. Background …………………………………….. 2

B. Purpose of the Study ……………………….. 3

A. Theoretical Framework …………………… 5

1. Concept A ……………………………….. 6

a. Definition ………………………….. 6

b. Example ……………………………. 7

2. Concept B ……………………………….. 8

B. Previous Research ………………………….. 9

III. Methodology ……………………………………… 12

A. Research Design ……………………………. 12

1. Sample ……………………………………. 13

2. Procedure ………………………………. 14

B. Data Collection …………………………….. 15

1. Instrumentation ……………………….. 16

2. Validity and Reliability ………………. 17

C. Data Analysis ……………………………….. 18

1. Descriptive Statistics …………………… 19

2. Inferential Statistics ………………….. 20

IV. Result s …………………………………………….. 22

A. Overview of Findings ……………………… 22

B. Hypothesis Testing …………………………. 23

V. Discussion …………………………………………. 26

A. Interpretation of Findings ………………… 26

B. Implications for Practice ………………… 28

VI. Conclusion ……………………………………….. 31

A. Summary of Findings ……………………… 31

B. Contributions and Recommendations ….. 33

Table of Contents Format

Here’s an example format for a Table of Contents:

I. Introduction

C. Methodology

II. Background

A. Historical Context

B. Literature Review

III. Methodology

A. Research Design

B. Data Collection

C. Data Analysis

IV. Results

A. Descriptive Statistics

B. Inferential Statistics

C. Qualitative Findings

V. Discussion

A. Interpretation of Results

B. Implications for Practice

C. Limitations and Future Research

VI. Conclusion

A. Summary of Findings

B. Contributions to the Field

C. Final Remarks

VII. References

VIII. Appendices

Note : This is just an example format and can vary depending on the type of document or research paper you are writing.

When to use Table of Contents

A TOC can be particularly useful in the following cases:

- Lengthy documents : If the document is lengthy, with several sections and subsections, a Table of contents can help readers quickly navigate the document and find the relevant information.

- Complex documents: If the document is complex, with multiple topics or themes, a TOC can help readers understand the relationships between the different sections and how they are connected.

- Technical documents: If the document is technical, with a lot of jargon or specialized terminology, This can help readers understand the organization of the document and locate the information they need.

- Legal documents: If the document is a legal document, such as a contract or a legal brief, It helps readers quickly locate specific sections or provisions.

How to Make a Table of Contents

Here are the steps to create a table of contents:

- Organize your document: Before you start making a table of contents, organize your document into sections and subsections. Each section should have a clear and descriptive heading that summarizes the content.

- Add heading styles : Use the heading styles in your word processor to format the headings in your document. The heading styles are usually named Heading 1, Heading 2, Heading 3, and so on. Apply the appropriate heading style to each section heading in your document.

- Insert a table of contents: Once you’ve added headings to your document, you can insert a table of contents. In Microsoft Word, go to the References tab, click on Table of Contents, and choose a style from the list. The table of contents will be inserted into your document.

- Update the table of contents: If you make changes to your document, such as adding or deleting sections, you’ll need to update the table of contents. In Microsoft Word, right-click on the table of contents and select Update Field. Choose whether you want to update the page numbers or the entire table, and click OK.

Purpose of Table of Contents

A table of contents (TOC) serves several purposes, including:

- Marketing : It can be used as a marketing tool to entice readers to read a book or document. By highlighting the most interesting or compelling sections, a TOC can give readers a preview of what’s to come and encourage them to dive deeper into the content.

- Accessibility : A TOC can make a document or book more accessible to people with disabilities, such as those who use screen readers or other assistive technologies. By providing a clear and organized overview of the content, a TOC can help these readers navigate the material more easily.

- Collaboration : This can be used as a collaboration tool to help multiple authors or editors work together on a document or book. By providing a shared framework for organizing the content, a TOC can help ensure that everyone is on the same page and working towards the same goals.

- Reference : It can serve as a reference tool for readers who need to revisit specific sections of a document or book. By providing a clear overview of the content and organization, a TOC can help readers quickly locate the information they need, even if they don’t remember exactly where it was located.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and...

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Paper Format – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Structure the Table of Contents for a Research Paper

4-minute read

- 16th July 2023

So you’ve made it to the important step of writing the table of contents for your paper. Congratulations on making it this far! Whether you’re writing a research paper or a dissertation , the table of contents not only provides the reader with guidance on where to find the sections of your paper, but it also signals that a quality piece of research is to follow. Here, we will provide detailed instructions on how to structure the table of contents for your research paper.

Steps to Create a Table of Contents

- Insert the table of contents after the title page.

Within the structure of your research paper , you should place the table of contents after the title page but before the introduction or the beginning of the content. If your research paper includes an abstract or an acknowledgements section , place the table of contents after it.

- List all the paper’s sections and subsections in chronological order.

Depending on the complexity of your paper, this list will include chapters (first-level headings), chapter sections (second-level headings), and perhaps subsections (third-level headings). If you have a chapter outline , it will come in handy during this step. You should include the bibliography and all appendices in your table of contents. If you have more than a few charts and figures (more often the case in a dissertation than in a research paper), you should add them to a separate list of charts and figures that immediately follows the table of contents. (Check out our FAQs below for additional guidance on items that should not be in your table of contents.)

- Paginate each section.

Label each section and subsection with the page number it begins on. Be sure to do a check after you’ve made your final edits to ensure that you don’t need to update the page numbers.

- Format your table of contents.

The way you format your table of contents will depend on the style guide you use for the rest of your paper. For example, there are table of contents formatting guidelines for Turabian/Chicago and MLA styles, and although the APA recommends checking with your instructor for formatting instructions (always a good rule of thumb), you can also create a table of contents for a research paper that follows APA style .

- Add hyperlinks if you like.

Depending on the word processing software you’re using, you may also be able to hyperlink the sections of your table of contents for easier navigation through your paper. (Instructions for this feature are available for both Microsoft Word and Google Docs .)

To summarize, the following steps will help you create a clear and concise table of contents to guide readers through your research paper:

1. Insert the table of contents after the title page.

2. List all the sections and subsections in chronological order.

3. Paginate each section.

4. Format the table of contents according to your style guide.

5. Add optional hyperlinks.

If you’d like help formatting and proofreading your research paper , check out some of our services. You can even submit a sample for free . Best of luck writing your research paper table of contents!

What is a table of contents?

A table of contents is a listing of each section of a document in chronological order, accompanied by the page number where the section begins. A table of contents gives the reader an overview of the contents of a document, as well as providing guidance on where to find each section.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

What should I include in my table of contents?

If your paper contains any of the following sections, they should be included in your table of contents:

● Chapters, chapter sections, and subsections

● Introduction

● Conclusion

● Appendices

● Bibliography

Although recommendations may differ among institutions, you generally should not include the following in your table of contents:

● Title page

● Abstract

● Acknowledgements

● Forward or preface

If you have several charts, figures, or tables, consider creating a separate list for them that will immediately follow the table of contents. Also, you don’t need to include the table of contents itself in your table of contents.

Is there more than one way to format a table of contents?

Yes! In addition to following any recommendations from your instructor or institution, you should follow the stipulations of your style guide .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

How to Insert a Text Box in a Google Doc

Google Docs is a powerful collaborative tool, and mastering its features can significantly enhance your...

2-minute read

How to Cite the CDC in APA

If you’re writing about health issues, you might need to reference the Centers for Disease...

5-minute read

Six Product Description Generator Tools for Your Product Copy

Introduction If you’re involved with ecommerce, you’re likely familiar with the often painstaking process of...

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

- Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples

Published on 15 May 2022 by Tegan George .

The table of contents is where you list the chapters and major sections of your thesis, dissertation, or research paper, alongside their page numbers. A clear and well-formatted table of contents is essential, as it demonstrates to your reader that a quality paper will follow.

The table of contents (TOC) should be placed between the abstract and the introduction. The maximum length should be two pages. Depending on the nature of your thesis, dissertation, or paper, there are a few formatting options you can choose from.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

What to include in your table of contents, what not to include in your table of contents, creating a table of contents in microsoft word, table of contents examples, updating a table of contents in microsoft word, other lists in your thesis, dissertation, or research paper, frequently asked questions about the table of contents.

Depending on the length of your document, you can choose between a single-level, subdivided, or multi-level table of contents.

- A single-level table of contents only includes ‘level 1’ headings, or chapters. This is the simplest option, but it may be too broad for a long document like a dissertation.

- A subdivided table of contents includes chapters as well as ‘level 2’ headings, or sections. These show your reader what each chapter contains.

- A multi-level table of contents also further divides sections into ‘level 3’ headings. This option can get messy quickly, so proceed with caution. Remember your table of contents should not be longer than 2 pages. A multi-level table is often a good choice for a shorter document like a research paper.

Examples of level 1 headings are Introduction, Literature Review, Methodology, and Bibliography. Subsections of each of these would be level 2 headings, further describing the contents of each chapter or large section. Any further subsections would be level 3.

In these introductory sections, less is often more. As you decide which sections to include, narrow it down to only the most essential.

Including appendices and tables

You should include all appendices in your table of contents. Whether or not you include tables and figures depends largely on how many there are in your document.

If there are more than three figures and tables, you might consider listing them on a separate page. Otherwise, you can include each one in the table of contents.

- Theses and dissertations often have a separate list of figures and tables.

- Research papers generally don’t have a separate list of figures and tables.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

All level 1 and level 2 headings should be included in your table of contents, with level 3 headings used very sparingly.

The following things should never be included in a table of contents:

- Your acknowledgements page

- Your abstract

- The table of contents itself

The acknowledgements and abstract always precede the table of contents, so there’s no need to include them. This goes for any sections that precede the table of contents.

To automatically insert a table of contents in Microsoft Word, be sure to first apply the correct heading styles throughout the document, as shown below.

- Choose which headings are heading 1 and which are heading 2 (or 3!

- For example, if all level 1 headings should be Times New Roman, 12-point font, and bold, add this formatting to the first level 1 heading.

- Highlight the level 1 heading.

- Right-click the style that says ‘Heading 1’.

- Select ‘Update Heading 1 to Match Selection’.

- Allocate the formatting for each heading throughout your document by highlighting the heading in question and clicking the style you wish to apply.

Once that’s all set, follow these steps:

- Add a title to your table of contents. Be sure to check if your citation style or university has guidelines for this.

- Place your cursor where you would like your table of contents to go.

- In the ‘References’ section at the top, locate the Table of Contents group.

- Here, you can select which levels of headings you would like to include. You can also make manual adjustments to each level by clicking the Modify button.

- When you are ready to insert the table of contents, click ‘OK’ and it will be automatically generated, as shown below.

The key features of a table of contents are:

- Clear headings and subheadings

- Corresponding page numbers

Check with your educational institution to see if they have any specific formatting or design requirements.

Write yourself a reminder to update your table of contents as one of your final tasks before submitting your dissertation or paper. It’s normal for your text to shift a bit as you input your final edits, and it’s crucial that your page numbers correspond correctly.

It’s easy to update your page numbers automatically in Microsoft Word. Simply right-click the table of contents and select ‘Update Field’. You can choose either to update page numbers only or to update all information in your table of contents.

In addition to a table of contents, you might also want to include a list of figures and tables, a list of abbreviations and a glossary in your thesis or dissertation. You can use the following guides to do so:

- List of figures and tables

- List of abbreviations

It is less common to include these lists in a research paper.

All level 1 and 2 headings should be included in your table of contents . That means the titles of your chapters and the main sections within them.

The contents should also include all appendices and the lists of tables and figures, if applicable, as well as your reference list .

Do not include the acknowledgements or abstract in the table of contents.

To automatically insert a table of contents in Microsoft Word, follow these steps:

- Apply heading styles throughout the document.

- In the references section in the ribbon, locate the Table of Contents group.

- Click the arrow next to the Table of Contents icon and select Custom Table of Contents.

- Select which levels of headings you would like to include in the table of contents.

Make sure to update your table of contents if you move text or change headings. To update, simply right click and select Update Field.

The table of contents in a thesis or dissertation always goes between your abstract and your introduction.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. (2022, May 15). Dissertation Table of Contents in Word | Instructions & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 6 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/contents-page/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, dissertation title page, how to write an abstract | steps & examples, thesis & dissertation acknowledgements | tips & examples.

- Langson Library

- Science Library

- Grunigen Medical Library

- Law Library

- Connect From Off-Campus

- Accessibility

- Gateway Study Center

Email this link

Thesis / dissertation formatting manual (2024).

- Filing Fees and Student Status

- Submission Process Overview

- Electronic Thesis Submission

- Paper Thesis Submission

- Formatting Overview

- Fonts/Typeface

- Pagination, Margins, Spacing

- Paper Thesis Formatting

- Preliminary Pages Overview

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

Table of Contents

- List of Figures (etc.)

- Acknowledgements

- Text and References Overview

- Figures and Illustrations

- Using Your Own Previously Published Materials

- Using Copyrighted Materials by Another Author

- Open Access and Embargoes

- Copyright and Creative Commons

- Ordering Print (Bound) Copies

- Tutorials and Assistance

- FAQ This link opens in a new window

The Table of Contents should follow these guidelines:

- All sections of the manuscript are listed in the Table of Contents except the Title Page, the Copyright Page, the Dedication Page, and the Table of Contents.

- You may list subsections within chapters

- Creative works are not exempt from the requirement to include a Table of Contents

Table of Contents Example

Here is an example of a Table of Contents page from the Template. Please note that your table of contents may be longer than one page.

- << Previous: Dedication Page

- Next: List of Figures (etc.) >>

- Last Updated: Feb 20, 2024 2:09 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uci.edu/gradmanual

Off-campus? Please use the Software VPN and choose the group UCIFull to access licensed content. For more information, please Click here

Software VPN is not available for guests, so they may not have access to some content when connecting from off-campus.

- University of Michigan Library

- Research Guides

Microsoft Word for Dissertations

- Table of Contents

- Introduction, Template, & Resources

- Formatting for All Readers

- Applying a Style

- Modifying a Style

- Setting up a Heading 1 Example

- Images, Charts, Other Objects

- Footnotes, Endnotes, & Citations

- Cross-References

- Appendix Figures & Tables

- List of Figures/Tables

- Chapter and Section Numbering

- Page Numbers

- Landscape Pages

- Combining Chapter Files

- Commenting and Reviewing

- The Two-inch Top Margin

- Troubleshooting

- Finalizing Without Styles

- Preparing Your Final Document

Automatic Table of Contents

An automatic Table of Contents relies on Styles to keep track of page numbers and section titles for you automatically. Microsoft Word can scan your document and find everything in the Heading 1 style and put that on the first level of your table of contents, put any Heading 2’s on the second level of your table of contents, and so on.

If you want an automatic table of contents you need to apply the Heading 1 style to all of your chapter titles and front matter headings (like “Dedication” and “Acknowledgements”). All section headings within your chapters should use the Heading 2 style. All sub-section headings should use Heading 3 , etc....

If you have used Heading styles in your document, creating an automatic table of contents is easy.

- Place your cursor where you want your table of contents to be.

- On the References Ribbon, in the Table of Contents Group , click on the arrow next to the Table of Contents icon, and select Custom Table of Contents .

- We suggest that you set each level (Chapters, sections, sub-sections, aka TOC 1, TOC 2, TOC 3) to be single-spaced, with 12 points of space afterwards. This makes each item in your ToC clump together if they're long enough to wrap to a second line, with the equivalent of a double space between each item, and makes the ToC easier to read and understand than if every line were double-spaced. See the video below for details.

- If you want to change which headings appear in your Table of Contents, you can do so by changing the number in the Show levels: field. Select "1" to just include the major sections (Acknowledgements, List of Figures, Chapters, etc...). Select "4" to include Chapters, sections, sub-sections, and sub-sub-sections.

- Click OK to insert your table of contents.

The table of contents is a snapshot of the headings and page numbers in your document, and does not automatically update itself as you make changes. At any time, you can update it by right-clicking on it and selecting Update field . Notice that once the table of contents is in your document, it will turn gray if you click on it. This just reminds you that it is a special field managed by Word, and is getting information from somewhere else.

Modifying the format of your Table of Contents

The video below shows how to make your Table of Contents a little easier to read by formatting the spacing between items in your Table of Contents. You may recognize the "Modify Style" window that appears, which can serve as a reminder that you can use this window to modify more than just paragraph settings. You can modify the indent distance, or font, or tab settings for your ToC, just the same as you may have modified it for Styles.

By default, the Table of Contents tool creates the ToC by pulling in Headings 1 through 3. If you'd like to modify that -- to only show H1's, or to show Headings 1 through 4 -- then go to the References tab and select Custom Table of Contents . In the window that appears, set Show Levels to "1" to only show Heading 1's in the Table of Contents, or set it to "4" to show Headings 1 through 4.

Bonus tip for updating fields like the Table of Contents

You'll quickly realize that all of the automatic Lists and Tables need to be updated occasionally to reflect any changes you've made elsewhere in the document -- they do not dynamically update by themselves. Normally, this means going to each field, right-clicking on it and selecting "Update Field".

Alternatively, to update all fields throughout your document (Figure/Table numbers & Lists, cross-references, Table of Contents, etc...), just select "Print". This will cause Word to update everything in anticipation of printing. Once the print preview window appears, just cancel.

The Plagiarism Checker Online For Your Academic Work

Start Plagiarism Check

Editing & Proofreading for Your Research Paper

Get it proofread now

Online Printing & Binding with Free Express Delivery

Configure binding now

- Academic essay overview

- The writing process

- Structuring academic essays

- Types of academic essays

- Academic writing overview

- Sentence structure

- Academic writing process

- Improving your academic writing

- Titles and headings

- APA style overview

- APA citation & referencing

- APA structure & sections

- Citation & referencing

- Structure and sections

- APA examples overview

- Commonly used citations

- Other examples

- British English vs. American English

- Chicago style overview

- Chicago citation & referencing

- Chicago structure & sections

- Chicago style examples

- Citing sources overview

- Citation format

- Citation examples

- College essay overview

- Application

- How to write a college essay

- Types of college essays

- Commonly confused words

- Definitions

- Dissertation overview

- Dissertation structure & sections

- Dissertation writing process

- Graduate school overview

- Application & admission

- Study abroad

- Master degree

- Harvard referencing overview

- Language rules overview

- Grammatical rules & structures

- Parts of speech

- Punctuation

- Methodology overview

- Analyzing data

- Experiments

- Observations

- Inductive vs. Deductive

- Qualitative vs. Quantitative

- Types of validity

- Types of reliability

- Sampling methods

- Theories & Concepts

- Types of research studies

- Types of variables

- MLA style overview

- MLA examples

- MLA citation & referencing

- MLA structure & sections

- Plagiarism overview

- Plagiarism checker

- Types of plagiarism

- Printing production overview

- Research bias overview

- Types of research bias

- Example sections

- Types of research papers

- Research process overview

- Problem statement

- Research proposal

- Research topic

- Statistics overview

- Levels of measurment

- Frequency distribution

- Measures of central tendency

- Measures of variability

- Hypothesis testing

- Parameters & test statistics

- Types of distributions

- Correlation

- Effect size

- Hypothesis testing assumptions

- Types of ANOVAs

- Types of chi-square

- Statistical data

- Statistical models

- Spelling mistakes

- Tips overview

- Academic writing tips

- Dissertation tips

- Sources tips

- Working with sources overview

- Evaluating sources

- Finding sources

- Including sources

- Types of sources

Your Step to Success

Plagiarism Check within 10min

Printing & Binding with 3D Live Preview

Table of Contents

How do you like this article cancel reply.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

A guide to the table of contents page

Inhaltsverzeichnis

- 1 Definition: Table of Contents

- 3 Everything for Your Thesis

- 5 Create in Microsoft Word

- 6 In a Nutshell

Definition: Table of Contents

The table of contents is an organized listing of your document’s chapters, sections and, often, figures, clearly labelled by page number. Readers should be able to look at your table of contents page and understand immediately how your paper is organized, enabling them to skip to any relevant section or sub-section. The table of contents should list all front matter, main content and back matter, including the headings and page numbers of all chapters and the bibliography . A good table of contents should be easy to read, accurately formatted and completed last so that it is 100% accurate. Although you can complete a table of contents manually, many word processing tools like Microsoft Word enable you to format your table of contents automatically.

When adding the finishing touches to your dissertation, the table of contents is one of the most crucial elements. It helps the reader navigate (like a map) through your argument and topic points. Adding a table of contents is simple and it can be inserted easily after you have finished writing your paper. In this guide, we look at the do’s and don’ts of a table of contents; this will help you process and format your dissertation in a professional way.

When adding the finishing touches to your dissertation, the table of contents is one of the most crucial elements. It helps the reader navigate (like a map) through your argument and topic points. Adding a table of contents is simple and can be inserted easily after you have finished writing your paper. In this guide, we look at the do’s and don’ts of a table of contents; this will help you process and format your dissertation in a professional way.

- ✓ Post a picture on Instagram

- ✓ Get the most likes on your picture

- ✓ Receive up to $300 cash back

What is a table of contents?

A table of contents is a list, usually on a page at the beginning of a piece of academic writing , which outlines the chapters or sections names with their corresponding page numbers. In addition to chapter names, it includes bullet points of the sub-chapter headings or subsection headings. It usually comes right after the title page of a research paper.

How do you write a table of contents

To write a table of contents, you first write the title or chapter names of your research paper in chronological order. Secondly, you write the subheadings or subtitles, if you have them in your paper. After that, you write the page numbers for the corresponding headings and subheadings. You can also very easily set up a table of contents in Microsoft Word.

Where do you put a table of contents?

The table of contents is found on a page right at the beginning of an academic writing project. It comes specifically after the title page and acknowledgements, but before the introductory page of a writing project. This position at the beginning of an academic piece of writing is universal for all academic projects.

What to include in a table of contents?

A sample table of contents includes the title of the paper at the very top, followed by the chapter names and subtitles in chronological order. At the end of each line, is the page number of the corresponding headings. Examples of chapter names can be: executive summary, introduction, project description, marketing plan, summary and conclusion. The abstract and acknowledgments are usually not included in the table of contents, however this could depend on the formatting that is required by your institution. Scroll down to see some examples.

How important is a table of contents?

A table of contents is very important at the beginning of a writing project for two important reasons. Firstly, it helps the reader easily locate contents of particular topics itemized as chapters or subtitles. Secondly, it helps the writer arrange their work and organize their thoughts so that important sections of an academic project are not left out. This has the extra effect of helping to manage the reader’s expectation of any academic essay or thesis right from the beginning.

Everything for Your Thesis

A table of contents is a crucial component of an academic thesis. Whether you’re completing a Bachelor’s or a postgraduate degree, the table of contents is a requirement for dissertation submissions. As a rule of thumb, your table of contents will usually come after your title page , abstract, acknowledgement or preface. Although it’s not necessary to include a reference to this front matter in your table of contents, different universities have different policies and guidelines.

Although the table of contents is best completed after you have finished your thesis, it’s a good idea to draw up a mock table of contents in the early stages of writing. This allows you to formulate a structure and think through your topic and how you are going to research, answer and make your argument. Think of this as a form of “reverse engineering”. Knowing how your chapters are going to be ordered and what topics or research questions are included in each will help immensely when it comes to your writing.

The table of contents is not just an academic formality, it allows your examiner to quickly get a feel for your topic and understand how your dissertation will be presented. An unclear or sloppy table of contents may even have an adverse effect on your grade because the dissertation is difficult to follow.

Examiners are readers, after all, and a dissertation is an exercise in producing an argument. A clear table of contents will give both a good impression and provide an accurate roadmap to make the examiner’s job easier and your argument more persuasive.

Your table of contents section will come after your acknowledgements and before your introduction. It includes a list of all your headers and their respective pages and will also contain a sub-section listing your tables, figures or illustrations (if you are using them). In general, your thesis can be ordered like this:

1. Title Page 2. Copyright / Statement of Originality 3. Abstract 4. Acknowledgement, Dedication and Preface (optional) 5. Table of Contents 6. List of Figures/Tables/Illustrations 7. Chapters 8. Appendices 9. Endnotes (depending on your formatting) 10. Bibliography / References

The formatting of your table of contents will depend on your academic field and thesis length. Some disciplines, like the sciences, have a methodical structure which includes recommended subheadings on methodology, data results, discussion and conclusion. Humanities subjects, on the other hand, are far more varied. Whichever discipline you are working in, you need to create an organized list of all chapters in their order of appearance, with chapter subheadings clearly labelled.

Sample table of contents for a short dissertation:

Abstract ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. ii Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. iii Dedication ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. iv List of Tables ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. x List of Figures ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. xi Chapter 1: Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1 Chapter 2: Literature Survey ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 13 Chapter 3: Methodology ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 42 Chapter 4: Analysis ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 100 Chapter 5: Conclusion ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 129 Appendices ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 169 References ………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 172

When producing a more significant and longer dissertation, say for a Master’s degree or even a PhD, your chapter descriptions should contain all subheadings. These are listed with the chapter number, followed by a decimal point and the subheading number.

Sample table of contents for a PhD dissertation:

Chapter 1 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Literature Review 1.3 Data 1.4 Findings 1.5 Conclusion

Chapter 2, and so on.

The key to writing a good table of contents is consistency and accuracy. You cannot list subheadings for one chapter and forget them for another. Subheadings are not always required but they can be very helpful if you are dealing with a detailed topic. The page numbers in the table of contents must match with the respective pages in your thesis or manuscript.

What’s more, chapter titles and subheading titles must match their corresponding pages. If your first chapter is called “Chapter 1: The Beginning”, it must be written as such on both the table of contents and first chapter page. So long as you remain both accurate and consistent, your table of contents will be perfect.

Create in Microsoft Word

Fortunately, the days of manually writing a contents page are over. You can still produce a contents page manually with Microsoft Word, but consider using their automatic feature to guarantee accuracy and save time.

To produce an automatically-generated table of contents, you must first work with heading styles. These can be found in the home tab under “Styles”. Select top-level headings (your chapter titles) and apply the Heading 1 style. This ensures that they will be formatted as main headings. Second-level headings (subheadings) can be applied with the Heading 2 style. This will place them underneath and within each main heading.

Once you have worked with heading styles, simply click on the “References” tab and select “Table of Contents”. This option will allow you to automatically produce a page with accurate page links to your document. To customize the format and style applied to your table of contents, select “Custom Table of Contents” at the bottom of the tab. Remember to update your table of contents by selecting the table and choosing “Update” from the drop-down menu. This will ensure that your headings, sub-headings and page numbers all add up.

Thesis Printing & Binding

You are already done writing your thesis and need a high quality printing & binding service? Then you are right to choose BachelorPrint! Check out our 24-hour online printing service. For more information click the button below :

In a Nutshell

- The table of contents is a vital part of any academic thesis or extensive paper.

- It is an accurate map of your manuscript’s content – its headings, sub-headings and page numbers.

- It shows how you have divided your thesis into more manageable chunks through the use of chapters.

- By breaking apart your thesis into discrete sections, you make your argument both more persuasive and easier to follow.

- What’s more, your contents page should produce an accurate map of your thesis’ references, bibliography, illustrations and figures.

- It is an accurate map of the chapters, references, bibliography, illustrations and figures in your thesis.

We use cookies on our website. Some of them are essential, while others help us to improve this website and your experience.

- External Media

Individual Privacy Preferences

Cookie Details Privacy Policy Imprint

Here you will find an overview of all cookies used. You can give your consent to whole categories or display further information and select certain cookies.

Accept all Save

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Show Cookie Information Hide Cookie Information

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us to understand how our visitors use our website.

Content from video platforms and social media platforms is blocked by default. If External Media cookies are accepted, access to those contents no longer requires manual consent.

Privacy Policy Imprint

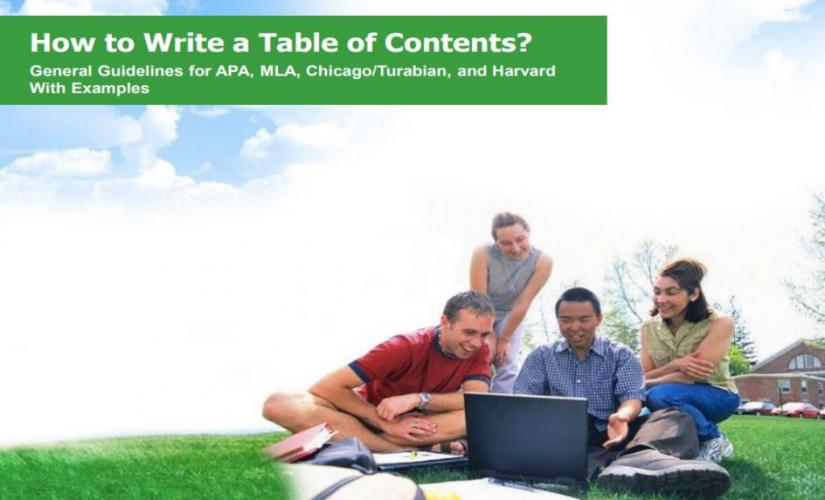

How to Write a Table of Contents for Different Formats With Examples

- 11 December 2023

Rules that guide academic writing are specific to each paper format. However, some rules apply to all styles – APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard. Basically, one of these rules is the inclusion of a Table of Contents (TOC) in an academic text, particularly long ones, like theses, dissertations, and research papers. When writing a TOC, students or researchers should observe some practices regardless of paper formats. Also, it includes writing the TOC on a new page after the title page, numbering the first-level and corresponding second-level headings, and indicating the page number of each entry. Hence, scholars need to learn how to write a table of contents in APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard styles.

General Guidelines

When writing academic texts, such as theses, dissertations, and other research papers, students observe academic writing rules as applicable. Generally, the different paper formats – APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard – have specific standards that students must follow in their writing. In this case, one of the rules is the inclusion of a Table of Contents (TOC) in the document. By definition, a TOC is a roadmap that scholars provide in their writing, outlining each portion of a paper. In other words, a TOC enables readers to locate specific information in documents or revisit favorite parts within written texts. Moreover, this part of academic papers provides readers with a preview of the paper’s contents.

For writing your paper, these links will be helpful:

- Buy Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Paper

- How to Write a Research Proposal

- How to Write a Term Paper

- How to Write a Case Study

Difference Between a Table of Contents and an Outline

In essence, a TOC is a description of first-level headings (topics) and second-level headings (subtopics) within the paper’s body. For a longer document, writers may also include third-level titles to make the text palatable to read. Ideally, the length of papers determines the depth that authors go into detailing their writing in TOCs. Basically, this feature means that shorter texts may not require third-level headings. In contrast, an essay outline is a summary of the paper’s main ideas with a hierarchical or logical structuring of the content. Unlike a TOC that only lists headings and subheadings, outlines capture these headings and then describe the content briefly under each one. As such, an outline provides a more in-depth summary of essay papers compared to a TOC.

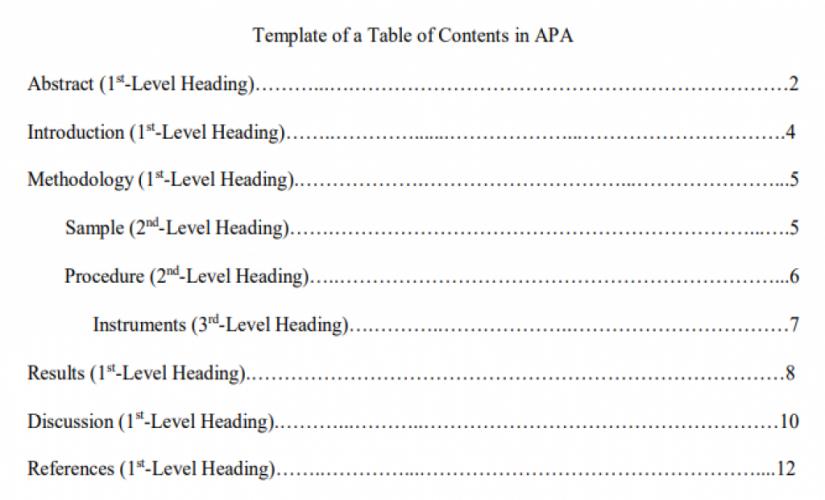

How to Write a Table of Contents in APA

When writing a TOC in the APA format , writers should capture all the headings in the paper – first-level, second-level, and even third-level. Besides this information, they should also include an abstract, references, and appendices. Notably, while a TOC in the APA style has an abstract, this section is not necessary for the other formats, like MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard. Hence, an example of a Table of Contents written in the APA format is indicated below:

How to Write a Table of Contents in MLA

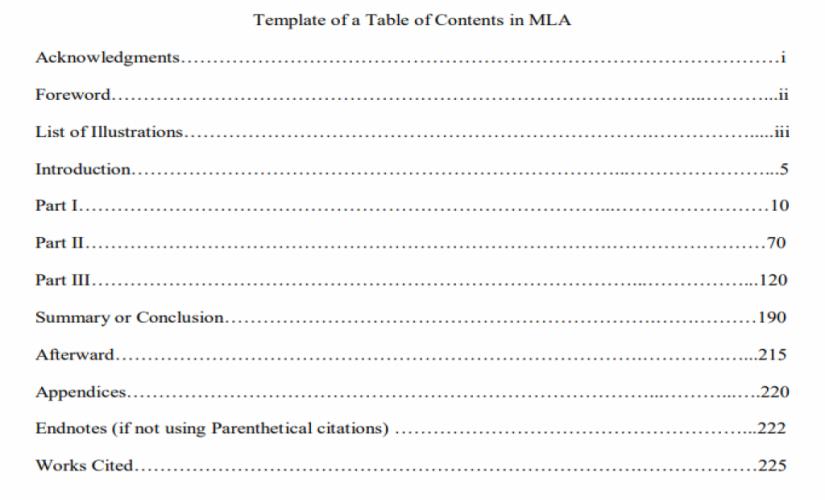

Unlike papers written in the APA style, MLA papers do not require a Table of Contents unless they are long enough. In this case, documents, like theses, dissertations, and books written in the MLA format should have a TOC. Even where a TOC is necessary, there is no specific method that a writer should use when writing it. In turn, the structure of the TOC is left to the writer’s discretion. However, when students have to include a TOC in their papers, the information they capture should be much more than what would appear in the APA paper . Hence, an example of writing a Table of Contents in MLA format is:

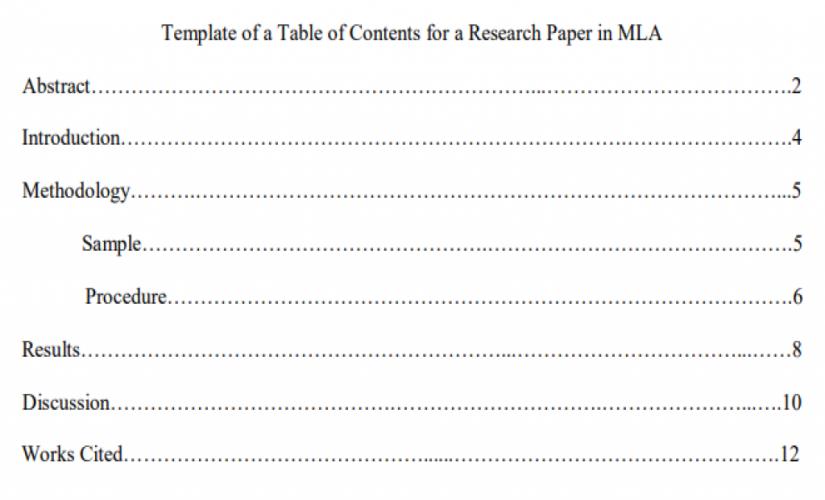

In the case of writing a research paper, an example of a Table of Contents should be:

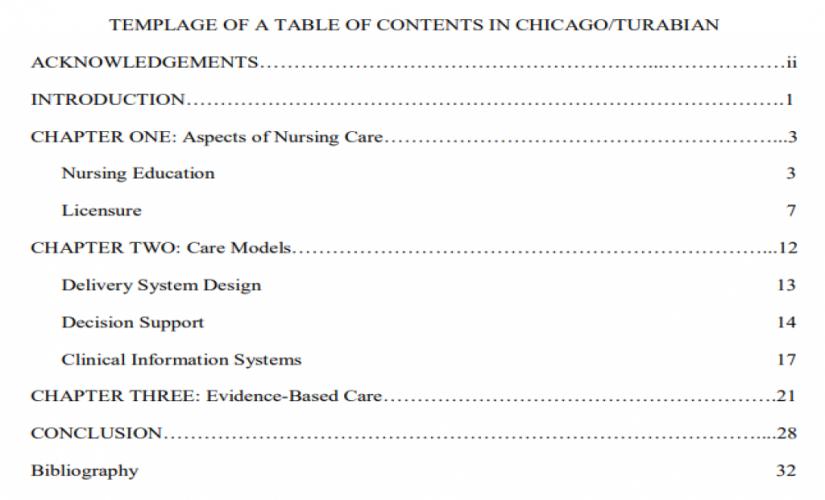

How to Write a Table of Contents in Chicago/Turabian

Like the MLA style, a Chicago/Turabian paper does not require writing a Table of Contents unless it is long enough. When a TOC is necessary, writers should capitalize on major headings. Additionally, authors do not need to add a row of periods (. . . . . . . .) between the heading entry and the page number. Moreover, the arrangement of the content should start with the first-level heading, then the second-level heading, and, finally, the third-level title, just like in the APA paper. In turn, all the information that precedes the introduction part should have lowercase Roman numerals. Also, the row of periods is only used for major headings. Hence, an example of writing a Table of Contents in a Chicago/Turabian paper is:

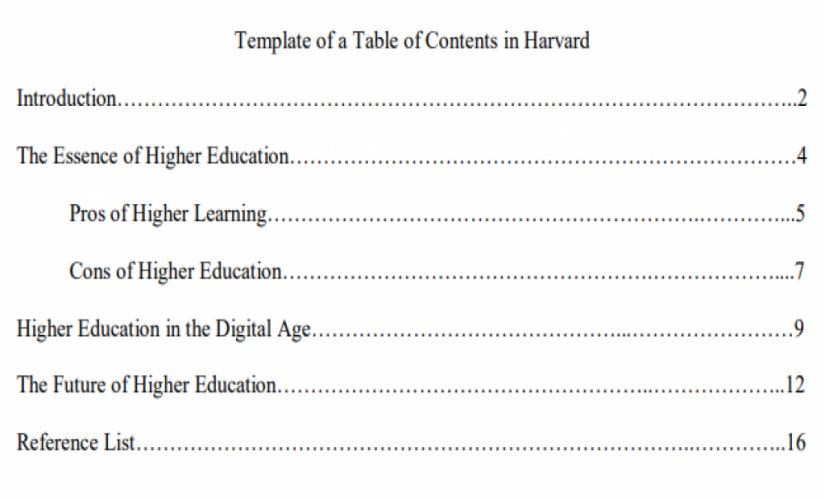

How to Write a Table of Contents in Harvard

Like in the other formats, writing a Table of Contents in the Harvard style is captured by having the title “Table of Contents” at the center of the page, in the first line. Basically, it comes after the title page and captures all the sections and subsections of Harvard papers. In other words, writers must indicate first-level headings in a numbered list. Also, scholars should align titles to the left side and capitalize them. In turn, if there is a need to show second-level headings, authors should list them under corresponding first-level headings by using bullet points. However, it is essential for students not to disrupt the numbering of first-level headings. Moreover, writers should align second-level headings to the left side and indent them by half an inch and capitalize on this content. Hence, an example of writing a Table of Contents in a Harvard paper should appear as below:

A Table of Content (TOC) is an essential component of an academic paper , particularly for long documents, like theses, dissertations, and research papers. When students are writing a TOC, they should be careful to follow the applicable format’s rules and standards. Regardless of the format, writers should master the following tips when writing a TOC:

- Write the TOC on a new page after the title page.

- Indicate first-level headings of the document in a numbered list.

- Indicate second-level headings under the corresponding first-level heading.

- If applicable, indicate third-level headings under the corresponding second-level heading.

- Write the page number for each heading.

- Put the content in a two-column table.

- Title the page with “Table of Contents.”

To Learn More, Read Relevant Articles

MIT Essay Prompts: Free Examples of Writing Assignments in 2024

- 26 August 2020

How to Cite a Dictionary in MLA 9: Guidelines and Examples

- 24 August 2020

- Foundations

- Write Paper

Search form

- Experiments

- Anthropology

- Self-Esteem

- Social Anxiety

- Research Paper >

Table of Contents Format

For Academic Papers

This table of contents is an essential part of writing a long academic paper, especially theoretical papers.

This article is a part of the guide:

- Outline Examples

- Example of a Paper

- Write a Hypothesis

- Introduction

Browse Full Outline

- 1 Write a Research Paper

- 2 Writing a Paper

- 3.1 Write an Outline

- 3.2 Outline Examples

- 4.1 Thesis Statement

- 4.2 Write a Hypothesis

- 5.2 Abstract

- 5.3 Introduction

- 5.4 Methods

- 5.5 Results

- 5.6 Discussion

- 5.7 Conclusion

- 5.8 Bibliography

- 6.1 Table of Contents

- 6.2 Acknowledgements

- 6.3 Appendix

- 7.1 In Text Citations

- 7.2 Footnotes

- 7.3.1 Floating Blocks

- 7.4 Example of a Paper

- 7.5 Example of a Paper 2

- 7.6.1 Citations

- 7.7.1 Writing Style

- 7.7.2 Citations

- 8.1.1 Sham Peer Review

- 8.1.2 Advantages

- 8.1.3 Disadvantages

- 8.2 Publication Bias

- 8.3.1 Journal Rejection

- 9.1 Article Writing

- 9.2 Ideas for Topics

It is usually not present in shorter research articles, since most empirical papers have similar structure .

A well laid out table of contents allows readers to easily navigate your paper and find the information that they need. Making a table of contents used to be a very long and complicated process, but the vast majority of word-processing programs, such as Microsoft WordTM and Open Office , do all of the hard work for you.

This saves hours of painstaking labor looking through your paper and makes sure that you have picked up on every subsection. If you have been using an outline as a basis for the paper, then you have a head start and the work on the table of contents formatting is already half done.

Whilst going into the exact details of how to make a table of contents in the program lies outside the scope of this article, the Help section included with the word-processing programs gives a useful series of tutorials and trouble-shooting guides.

That said, there are a few easy tips that you can adopt to make the whole process a little easier.

The Importance of Headings

In the word processing programs, there is the option of automatically creating headings and subheadings, using heading 1, heading 2, heading 3 etc on the formatting bar. You should make sure that you get into the habit of doing this as you write the paper, instead of manually changing the font size or using the bold format.

Once you have done this, you can click a button, and the program will do everything for you, laying out the table of contents formatting automatically, based upon all of the headings and subheadings.

In Word, to insert a table of contents, first ensure that the cursor is where you want the table of contents to appear. Once you are happy with this, click 'Insert' on the drop down menu, scroll down to 'Reference,' and then across to 'Index and Tables'.

Click on the 'Table of Contents' tab and you are ready to click OK and go. OpenOffice is a very similar process but, after clicking 'Insert,' you follow 'Indexes and Tables' and 'Indexes and Tables' again.

The table of contents should appear after the title page and after the abstract and keywords, if you use them. As with all academic papers, there may be slight variations from department to department and even from supervisor to supervisor.

Check the preferred table of contents format before you start writing the paper , because changing things retrospectively can be a little more time consuming.

- Psychology 101

- Flags and Countries

- Capitals and Countries

Martyn Shuttleworth (Aug 27, 2009). Table of Contents Format. Retrieved May 10, 2024 from Explorable.com: https://explorable.com/table-of-contents-format

You Are Allowed To Copy The Text

The text in this article is licensed under the Creative Commons-License Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) .

This means you're free to copy, share and adapt any parts (or all) of the text in the article, as long as you give appropriate credit and provide a link/reference to this page.

That is it. You don't need our permission to copy the article; just include a link/reference back to this page. You can use it freely (with some kind of link), and we're also okay with people reprinting in publications like books, blogs, newsletters, course-material, papers, wikipedia and presentations (with clear attribution).

Related articles

Want to stay up to date follow us, check out the official book.

Learn how to construct, style and format an Academic paper and take your skills to the next level.

(also available as ebook )

Save this course for later

Don't have time for it all now? No problem, save it as a course and come back to it later.

Footer bottom

- Privacy Policy

- Subscribe to our RSS Feed

- Like us on Facebook

- Follow us on Twitter

Free All-in-One Office Suite with PDF Editor

Edit Word, Excel, and PPT for FREE.

Read, edit, and convert PDFs with the powerful PDF toolkit.

Microsoft-like interface, easy to use.

Windows • MacOS • Linux • iOS • Android

Select areas that need to improve

- Didn't match my interface

- Too technical or incomprehensible

- Incorrect operation instructions

- Incomplete instructions on this function

Fields marked * are required please

Please leave your suggestions below

- Quick Tutorials

- Practical Skills

How to Create a Table of Contents in Word for Your Paper? [For Students]

Working on a paper or thesis is mentally exhausting on its own, but having to format everything according to MLA, APA, or Chicago style can be a real headache, especially when creating a table of contents. Manually updating it every time you make changes is tedious and error-prone. What you really need is a way to generate and update the table of contents automatically, allowing you to concentrate on the content without worrying about the structure.

This makes the entire process smoother and less stressful, letting you focus on your research without the constant formatting frustration. In this article, we will explore the essentials of creating a functional and clear table of contents Word for students, covering what it is, why it's important, and how to prepare one that effectively outlines your paper's structure.

Table of Contents in APA, MLA and Chicago Style

In academic writing, particularly for longer pieces such as thesis, dissertations, and research papers, having a clear organization is highly beneficial. A crucial aspect that helps readers navigate your work is a Table of Contents (TOC). Despite the variations in specific style guides like APA, MLA, or Chicago, incorporating a TOC provides numerous advantages. Besides these benefits, TOCs in these three academic formats adhere to generally similar guidelines, although there are some differences that must be acknowledged and addressed.

1. A Table of Contents in APA

The American Psychological Association (APA) style is commonly used in the social sciences. While APA style does not always require a table of contents, it is often recommended for lengthy papers or theses. Here's how to structure a table of contents in APA style:

Placement : The TOC goes between the abstract and introduction on a separate page.

Formatting : Use the same font and size as your main text (typically 12 pt Times New Roman).

Title : Center and bold the word "Contents" at the top of the page.

Heading Levels : Include all level 1 (main sections) and level 2 (subheadings) headings in the TOC.

Alignment : Left-align all entries in the TOC.

Indentation : Level 2 headings are indented for clarity.

Lower Levels (Optional) : Including level 3 headings or lower is optional and requires additional indentation for each level.

Length : Keep the TOC concise; ideally, it shouldn't exceed two pages.

2. A Table of Contents in MLA

The Modern Language Association (MLA) style is typically used in the humanities. While MLA does not always require a table of contents for shorter papers, longer academic works may benefit from having one. Here are some tips for creating a table of contents in MLA style:

Font and Size : Stick to Times New Roman, 12 point size, for consistency with the rest of your document.

Margins : Use standard 1-inch margins on all sides.

Spacing : Double line spacing is the norm for MLA formatting.

Indentations : Create a clear distinction between paragraphs with a ½-inch indent for the first line.

Headings : Use title case capitalization (capitalize the first word of each main word) for your headings in the TOC.

3. A Table of Contents in Chicago Style

The Chicago Manual of Style (CMS) is widely used in historical and other academic research. Chicago style often requires a detailed table of contents for dissertations and other extensive works. Here's how to create a table of contents in Chicago style:

Starting Fresh : Begin your TOC on a separate page following the title page.

Clear Labeling : Center the title "Contents" at the top of the page.

Spacing for Readability : Leave a double space between "Contents" and the first entry in your TOC.

Mirroring Your Paper : List chapter titles, headings, and subheadings in the exact order they appear in your paper.

Matching Matters : Ensure capitalization and the hierarchy of titles/headings in the TOC match your paper's formatting.

Pinpointing Locations : Place page numbers flush right, using leader dots (a series of periods) to connect them to the corresponding entry.

How to Create a Table of Contents Easily in Word for Your Paper

Before inserting a table of contents in Word , we first need to format the headings of our research paper or thesis according to an academic style.

Let's take a look at it through an example for better understanding. We need to write a research paper on Environment Safety, so before getting started with the writing part, let’s create an outline for it. This means we will need to lay out the headings in order. We have a main heading called Heading 1, and then we have subheadings called Heading 2. In some instances, we have Heading 3 or Heading 4 as well, so let's take a look at the breakdown of these headings beforehand.

H1 : The main heading of your document, typically used once for the overall title.

H2 : Subheadings that break down your H1 topic into major sections.

H3 : Subheadings that further divide your H2 sections into more specific points.

If you understand this, then formatting will be a breeze for you. So let's jump right into it:

Step 1 : We now have our outline laid out in our document on Microsoft Word.

Step 2 : Even though I went through and formatted my headings and subheadings by increasing the font size of the main headings and making them bold, this is completely wrong.

Step 3 : In Word, we need to do proper formatting. To do this, click on your main heading of the essay and head over to the Home tab.

Step 4 : Now, in the "Styles" section, you will see various styles. From this, click on "Heading 1", and you will notice a change in your headings formatting.

Step 5 : To change the formatting to fit your academic style, right-click on the "Heading 1" button in the Styles section to open the context menu, and then click on "Modify".

Step 6 : In the Modify Style dialog, users can change the font, font size, and other changes to format their heading.

Step 7 : Similarly, click on Heading 2 in your document, then in the Styles section, select Heading 2, and so on.

Step 8 : Once all the headings have been formatted, now we can proceed to inserting a table of contents into our document.

Step 9 : To insert the table of contents, visit the Reference tab and then click on the "Table of Contents" option in the ribbon menu.

Step 10 : Microsoft Word gives its users the option to insert a pre-formatted table of contents, but if you wish to insert a custom-made table of contents, that's also possible.

Step 11 : Once you have selected your desired table of contents, it will be added, and you can now complete your work with ease.

How to Update the Table of Contents in Word for Your Paper

The outline was ready, or at least that's what we thought, but now we added a few new headings, but they won't show up in the table of contents. Now, to address this, we need to Update our Table of Contents:

Step 1 : Let's open Microsoft Word again. As we can see, there's nothing changed in the table of contents even though we've correctly styled the headings in our essay.

Step 2 : To update the table of contents, right-click anywhere on the table of contents to open the context menu.

Step 3 : In the context menu, we need to click on "Update Field" or simply press the shortcut key "F9".

Step 4 : Now, we see the Update Table of Contents dialog. Click on "Update entire table" and then click "OK".

Step 5 : The table of contents will now be completely updated with the new headings that you've inserted.

Bonus Tip: Converting Your Paper to PDF Without Losing Format

Once you're done with your paper and a well-organized table of contents, the next step is often converting it to a PDF. This is crucial because PDFs preserve formatting, ensuring that your hard work doesn't get scrambled when shared or printed. However, conversion can be tricky, especially with Microsoft Word 365. When converting a document to PDF in Word 365, you might encounter issues like misaligned text, broken page breaks, or distorted table of contents formatting.

WPS Office is an excellent alternative to Microsoft Word 365 for PDF conversions. It offers robust PDF features that can convert your paper without losing formatting. Here's why WPS Office might be a better choice:

Direct PDF Conversion : WPS Office has a built-in PDF converter that maintains the layout and structure of your document, reducing the risk of misalignment.

Enhanced PDF Features : WPS Office allows you to merge, split, or compress PDFs , which can be useful if you need to adjust your document after conversion.

Easy Table of Contents Management : WPS Office handles tables of contents well, ensuring links and formatting remain intact.

WPS Office: Use Word, Excel, and PPT for FREE, No Ads.

Now, to convert your Word document with the table of contents into a PDF document without losing any formatting in the process, WPS Office provides a very easy and effective solution:

Step 1 : Let's open the Word document in WPS Office and then head over to the Menu on the top left of the page.

Step 2 : In the menu, click on "Save as" and select "Other formats" from the flyout menu.

Step 3 : Simply in the Save as options, change the file type to "PDF" in the "File Type" field and then hit "Save" to save your document as a PDF.

FAQs about Table of Contents in Word

1. how do i link headings to table of contents in word.

If you've inserted a manual table, here's how to link headings to a table of contents in Microsoft Word:

Step 1 : Go to your table of contents.

Step 2 : Select the heading in the table of contents you want to link to your document heading.

Step 3 : Right-click and choose "Link" from the context menu.

Step 4 : In the Insert Link dialog, select the "Place in This Document" tab and choose the heading you want to link to. Click OK to finish.

Step 5 : The linked heading will appear blue and underlined in your table of contents.

2. How do you update a Table of Contents in Word and keep formatting?

To adjust your current table of contents:

Step 1 : Go to the References tab.

Step 2 : Click on Table of Contents.

Step 3 : Choose Custom table of contents.

Step 4 : Use the options to change what appears in the table, how page numbers are displayed, adjust formatting, and decide how many heading levels to include.

3. How do I link a table of contents to a page in word?

Users can easily link the table of contents to pages in Word by applying heading styles to document sections and then clicking on the Update tab in the Reference tab.a

Perfect Your Paper: Mastering Table of Contents with WPS Office

Your thesis or report isn't complete without a table of contents, especially if it's a requirement. Forgetting this crucial section could lead to a lower grade, which might have been avoided by simply adding a well-structured table of contents. To ensure your report meets the necessary academic standards, not only should you include a table of contents Word for students, but you should also make sure it's correctly formatted according to the guidelines.

WPS Office is the ideal tool for writing your paper, thanks to its robust formatting capabilities. It's particularly useful when you need to share your document or convert it to PDF, as WPS Office maintains your formatting without glitches. So, if you haven't tried WPS Office yet, consider downloading it now to streamline your writing process and keep your formatting consistent.

- 1. How to insert table of contents in Word

- 2. How to Find and Replace in Word for Your Paper? [For Students]

- 3. Best & well-organized table of contents template word Free download

- 4. How to insert or remove Table of Contents in Word?

- 5. Free 10 Professional & Simple Word Table of Contents Template Download Now

- 6. Well-Organized TOP 10 Template for Table of Contents in Word

15 years of office industry experience, tech lover and copywriter. Follow me for product reviews, comparisons, and recommendations for new apps and software.

RESEARCH PAPER: Infoblox SOC Insights – Enabling Higher Levels of Security Through DNS

Security professionals face growing complexities created by multi-cloud and hybrid OT and IT infrastructure deployments. A highly disaggregated architectural approach leveraging cloud scale has proven advantages in accelerating digital transformation through gains in operational agility and flexibility. However, it also introduces many challenges – the most glaring one being a dramatically expanded threat surface that must be defended. The heterogeneous nature of cloud networking architectures also contributes to poor observability among clouds. Consequently, enterprises must embrace new security operational models that can provide higher levels of visibility to keep pace with an ever-increasing threat landscape perpetuated by bad actors that hope to leverage AI to their advantage.

You can download the paper by clicking on the logo below:

Table of Contents

- Executive Summary

- SOC Challenges

- Why Infoblox

- Call to Action

Will Townsend

- Will Townsend https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/will-townsend/ John Deere Accelerates Manufacturing Innovation With Private 5G

- Will Townsend https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/will-townsend/ Three Big Telecom Takeaways From Mobile World Congress Barcelona 2024

- Will Townsend https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/will-townsend/ Is 2024 The Year Of Low Earth Orbit Satellite Services?

- Will Townsend https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/will-townsend/ Three 5G Networking And Cybersecurity Predictions: A Retrospective

Patrick Moorhead

- Patrick Moorhead https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/phfmphfmgmail-com/ Moor Insights & Strategy Weekly Update Ending May 3, 2024

- Patrick Moorhead https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/phfmphfmgmail-com/ Microsoft’s AI PCs Focus On Business-First Applications With Copilot

- Patrick Moorhead https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/phfmphfmgmail-com/ Synaptics Introduces Astra Platform For Edge AI

- Patrick Moorhead https://moorinsightsstrategy.com/author/phfmphfmgmail-com/ Intel Announces Gaudi 3 Accelerator For Generative AI

Recent Posts

RESEARCH PAPER: Untether AI – Where Performance Intersects With Efficiency

RESEARCH PAPER: AMD Pensando – Silicon that Supercharges the Modern Datacenter

RESEARCH PAPER: AI PC: What You Need To Know About The Future of Computing and AI

RESEARCH PAPER: Private Cellular Networks: Unlocking Value in Warehousing and Logistics

RESEARCH PAPER: Fortinet: Optimizing Business Outcomes Through Network & Security Convergence

RESEARCH PAPER: Infoblox: Unlocking The Power Of Domain Name System For Security

Become an mi&s insider.

Stay up to date with tech insights and research from leading industry experts.

We work with leaders in every category

#1 ARInsights Ranking

Important Links

Privacy Policy

Terms of Use

Cookie Settings

Disclosures

Sustainability

Join the Conversation on Social

© 2024 Moor Insights & Strategy. All Rights Reserved.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

Volume 629 Issue 8011, 9 May 2024

Fossil fuels supply most of the world’s energy and are the basis of many key products used in everyday life, but they are also a major source of carbon dioxide emissions. Although renewable energy has the potential to replace fossil-fuel-generated energy, there will still be a need for the transport fuels and chemicals produced by oil refineries. In this week’s issue, Eelco Vogt and Bert Weckhuysen examine ways in which oil refineries could be reinvented to be completely fossil-free. They note that with sufficient long-term commitment and support, the science and technology for such a refinery could be developed, and they sketch a roadmap towards this goal.

Cover image: Jasiek Krzysztofiak/Nature

Reinvent oil refineries for a net-zero future

From petrol to plastics, oil-derived products define modern life. A bold plan to change that comes with huge costs — but researchers and policymakers should take it seriously.

Advertisement

Expat grants won’t fix Brazilian research

Permanent jobs and fairer hiring practices would encourage overseas scientists to return.

- Juliano Morimoto

Research Highlights

A magnetic liquid makes for an injectable sensor in living tissue.

Fluid studded with microscopic magnetic particles can be inserted into the body and later retrieved.

Pandemic lockdowns were less of a shock for people with fewer ties

During periods of enforced isolation, life satisfaction for older adults took less of a hit in those who were already socially isolated.

Not just truffles: dogs can sniff out surpassingly rare native fungus

Daisy, a member of a breed used to find fungal delicacies, detected a critically endangered Australian fungus faster than a trained human could.

Never mind little green men: life on other planets might be purple

Bacteria that make food using a compound other than chlorophyll could paint other planets in a wide range of colours.

News in Focus

What china’s mission to collect rocks from the moon’s far side could reveal.

The Chang’e-6 mission aims to land in the Moon’s oldest and largest crater, where it will collect rocks to bring back to Earth.

First fetus-to-fetus transplant demonstrated in rats

The tissue developed into functioning kidneys and produced urine.

- Smriti Mallapaty

Superconductivity hunt gets boost from China’s $220 million physics ‘playground’

From extreme cold to strong magnets and high pressures, the Synergetic Extreme Condition User Facility (SECUF) provides conditions for researching potential wonder materials.

- Gemma Conroy

Scientists tried to give people COVID — and failed

Researchers deliberately infect participants with SARS-CoV-2 in ‘challenge’ trials — but high levels of immunity complicate efforts to test vaccines and treatments.

- Ewen Callaway

Epic blazes threaten Arctic permafrost. Can firefighters save it?

Some scientists argue that it’s time to rethink the blanket policy of letting blazes burn themselves out in northern wildernesses.

- Jeff Tollefson

How reliable is this research? Tool flags papers discussed on PubPeer

Browser plug-in alerts users when studies — or their references — have been posted on a site known for raising integrity concerns.

- Dalmeet Singh Chawla

‘ChatGPT for CRISPR’ creates new gene-editing tools

Some of the AI-designed gene editors could be more versatile than those found in nature.

Dark energy is tearing the Universe apart. What if the force is weakening?

The first set of results from a pioneering cosmic-mapping project hints that the repulsive force known as dark energy has changed over 11 billion years, which would alter ideas about how the Universe has evolved and what its future will be.

- Davide Castelvecchi

Hacking the immune system could slow ageing — here’s how

Our immune system falters over time, which could explain the negative effects of ageing.