Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- UConn Library

- Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide

- Introduction

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide — Introduction

- Getting Started

- How to Pick a Topic

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Sources & Lit. Reviews

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

What are Literature Reviews?

So, what is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries." Taylor, D. The literature review: A few tips on conducting it . University of Toronto Health Sciences Writing Centre.

Goals of Literature Reviews

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review? A literature could be written to accomplish different aims:

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1997). Writing narrative literature reviews . Review of General Psychology , 1 (3), 311-320.

What kinds of sources require a Literature Review?

- A research paper assigned in a course

- A thesis or dissertation

- A grant proposal

- An article intended for publication in a journal

All these instances require you to collect what has been written about your research topic so that you can demonstrate how your own research sheds new light on the topic.

Types of Literature Reviews

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Narrative review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Example : Predictors and Outcomes of U.S. Quality Maternity Leave: A Review and Conceptual Framework: 10.1177/08948453211037398

Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L. K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . Plural Publishing.

- Example : The effect of leave policies on increasing fertility: a systematic review: 10.1057/s41599-022-01270-w

Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M. C., & Ilardi, S. S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Blackwell Publishing.

- Example : Employment Instability and Fertility in Europe: A Meta-Analysis: 10.1215/00703370-9164737

Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts . Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53 (3), 311-318.

- Example : Women’s perspectives on career successes and barriers: A qualitative meta-synthesis: 10.1177/05390184221113735

Literature Reviews in the Health Sciences

- UConn Health subject guide on systematic reviews Explanation of the different review types used in health sciences literature as well as tools to help you find the right review type

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: How to Pick a Topic >>

- Last Updated: Sep 21, 2022 2:16 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.uconn.edu/literaturereview

Libraries | Research Guides

Literature reviews, what is a literature review, learning more about how to do a literature review.

- Planning the Review

- The Research Question

- Choosing Where to Search

- Organizing the Review

- Writing the Review

A literature review is a review and synthesis of existing research on a topic or research question. A literature review is meant to analyze the scholarly literature, make connections across writings and identify strengths, weaknesses, trends, and missing conversations. A literature review should address different aspects of a topic as it relates to your research question. A literature review goes beyond a description or summary of the literature you have read.

- Sage Research Methods Core Collection This link opens in a new window SAGE Research Methods supports research at all levels by providing material to guide users through every step of the research process. SAGE Research Methods is the ultimate methods library with more than 1000 books, reference works, journal articles, and instructional videos by world-leading academics from across the social sciences, including the largest collection of qualitative methods books available online from any scholarly publisher. – Publisher

- Next: Planning the Review >>

- Last Updated: May 2, 2024 10:39 AM

- URL: https://libguides.northwestern.edu/literaturereviews

Reference management. Clean and simple.

What is a literature review? [with examples]

What is a literature review?

The purpose of a literature review, how to write a literature review, the format of a literature review, general formatting rules, the length of a literature review, literature review examples, frequently asked questions about literature reviews, related articles.

A literature review is an assessment of the sources in a chosen topic of research.

In a literature review, you’re expected to report on the existing scholarly conversation, without adding new contributions.

If you are currently writing one, you've come to the right place. In the following paragraphs, we will explain:

- the objective of a literature review

- how to write a literature review

- the basic format of a literature review

Tip: It’s not always mandatory to add a literature review in a paper. Theses and dissertations often include them, whereas research papers may not. Make sure to consult with your instructor for exact requirements.

The four main objectives of a literature review are:

- Studying the references of your research area

- Summarizing the main arguments

- Identifying current gaps, stances, and issues

- Presenting all of the above in a text

Ultimately, the main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

The format of a literature review is fairly standard. It includes an:

- introduction that briefly introduces the main topic

- body that includes the main discussion of the key arguments

- conclusion that highlights the gaps and issues of the literature

➡️ Take a look at our guide on how to write a literature review to learn more about how to structure a literature review.

First of all, a literature review should have its own labeled section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature can be found, and you should label this section as “Literature Review.”

➡️ For more information on writing a thesis, visit our guide on how to structure a thesis .

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, it will be short.

Take a look at these three theses featuring great literature reviews:

- School-Based Speech-Language Pathologist's Perceptions of Sensory Food Aversions in Children [ PDF , see page 20]

- Who's Writing What We Read: Authorship in Criminological Research [ PDF , see page 4]

- A Phenomenological Study of the Lived Experience of Online Instructors of Theological Reflection at Christian Institutions Accredited by the Association of Theological Schools [ PDF , see page 56]

Literature reviews are most commonly found in theses and dissertations. However, you find them in research papers as well.

There is no set amount of words for a literature review, so the length depends on the research. If you are working with a large amount of sources, then it will be long. If your paper does not depend entirely on references, then it will be short.

No. A literature review should have its own independent section. You should indicate clearly in the table of contents where the literature review can be found, and label this section as “Literature Review.”

The main goal of a literature review is to provide the researcher with sufficient knowledge about the topic in question so that they can eventually make an intervention.

The Sheridan Libraries

- Write a Literature Review

- Sheridan Libraries

- Find This link opens in a new window

- Evaluate This link opens in a new window

What Will You Do Differently?

Please help your librarians by filling out this two-minute survey of today's class session..

Professor, this one's for you .

Introduction

Literature reviews take time. here is some general information to know before you start. .

- VIDEO -- This video is a great overview of the entire process. (2020; North Carolina State University Libraries) --The transcript is included --This is for everyone; ignore the mention of "graduate students" --9.5 minutes, and every second is important

- OVERVIEW -- Read this page from Purdue's OWL. It's not long, and gives some tips to fill in what you just learned from the video.

- NOT A RESEARCH ARTICLE -- A literature review follows a different style, format, and structure from a research article.

Steps to Completing a Literature Review

- Next: Find >>

- Last Updated: Sep 26, 2023 10:25 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/lit-review

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

Research Methods

- Getting Started

- Literature Review Research

- Research Design

- Research Design By Discipline

- SAGE Research Methods

- Teaching with SAGE Research Methods

Literature Review

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is NOT a Literature Review?

- Purposes of a Literature Review

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Literature Reviews vs. Systematic Reviews

- Systematic vs. Meta-Analysis

Literature Review is a comprehensive survey of the works published in a particular field of study or line of research, usually over a specific period of time, in the form of an in-depth, critical bibliographic essay or annotated list in which attention is drawn to the most significant works.

Also, we can define a literature review as the collected body of scholarly works related to a topic:

- Summarizes and analyzes previous research relevant to a topic

- Includes scholarly books and articles published in academic journals

- Can be an specific scholarly paper or a section in a research paper

The objective of a Literature Review is to find previous published scholarly works relevant to an specific topic

- Help gather ideas or information

- Keep up to date in current trends and findings

- Help develop new questions

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Helps focus your own research questions or problems

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Suggests unexplored ideas or populations

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

- Identifies critical gaps, points of disagreement, or potentially flawed methodology or theoretical approaches.

- Indicates potential directions for future research.

All content in this section is from Literature Review Research from Old Dominion University

Keep in mind the following, a literature review is NOT:

Not an essay

Not an annotated bibliography in which you summarize each article that you have reviewed. A literature review goes beyond basic summarizing to focus on the critical analysis of the reviewed works and their relationship to your research question.

Not a research paper where you select resources to support one side of an issue versus another. A lit review should explain and consider all sides of an argument in order to avoid bias, and areas of agreement and disagreement should be highlighted.

A literature review serves several purposes. For example, it

- provides thorough knowledge of previous studies; introduces seminal works.

- helps focus one’s own research topic.

- identifies a conceptual framework for one’s own research questions or problems; indicates potential directions for future research.

- suggests previously unused or underused methodologies, designs, quantitative and qualitative strategies.

- identifies gaps in previous studies; identifies flawed methodologies and/or theoretical approaches; avoids replication of mistakes.

- helps the researcher avoid repetition of earlier research.

- suggests unexplored populations.

- determines whether past studies agree or disagree; identifies controversy in the literature.

- tests assumptions; may help counter preconceived ideas and remove unconscious bias.

As Kennedy (2007) notes*, it is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the original studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally that become part of the lore of field. In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews.

Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are several approaches to how they can be done, depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study. Listed below are definitions of types of literature reviews:

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply imbedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews.

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical reviews are focused on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [content], but how they said it [method of analysis]. This approach provides a framework of understanding at different levels (i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches and data collection and analysis techniques), enables researchers to draw on a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection and data analysis, and helps highlight many ethical issues which we should be aware of and consider as we go through our study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyse data from the studies that are included in the review. Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?"

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to concretely examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review help establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

* Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147.

All content in this section is from The Literature Review created by Dr. Robert Larabee USC

Robinson, P. and Lowe, J. (2015), Literature reviews vs systematic reviews. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 39: 103-103. doi: 10.1111/1753-6405.12393

What's in the name? The difference between a Systematic Review and a Literature Review, and why it matters . By Lynn Kysh from University of Southern California

Systematic review or meta-analysis?

A systematic review answers a defined research question by collecting and summarizing all empirical evidence that fits pre-specified eligibility criteria.

A meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of these studies.

Systematic reviews, just like other research articles, can be of varying quality. They are a significant piece of work (the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination at York estimates that a team will take 9-24 months), and to be useful to other researchers and practitioners they should have:

- clearly stated objectives with pre-defined eligibility criteria for studies

- explicit, reproducible methodology

- a systematic search that attempts to identify all studies

- assessment of the validity of the findings of the included studies (e.g. risk of bias)

- systematic presentation, and synthesis, of the characteristics and findings of the included studies

Not all systematic reviews contain meta-analysis.

Meta-analysis is the use of statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects of health care than those derived from the individual studies included within a review. More information on meta-analyses can be found in Cochrane Handbook, Chapter 9 .

A meta-analysis goes beyond critique and integration and conducts secondary statistical analysis on the outcomes of similar studies. It is a systematic review that uses quantitative methods to synthesize and summarize the results.

An advantage of a meta-analysis is the ability to be completely objective in evaluating research findings. Not all topics, however, have sufficient research evidence to allow a meta-analysis to be conducted. In that case, an integrative review is an appropriate strategy.

Some of the content in this section is from Systematic reviews and meta-analyses: step by step guide created by Kate McAllister.

- << Previous: Getting Started

- Next: Research Design >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 4:07 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.udel.edu/researchmethods

- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

Write a Literature Review

- Developing a Research Question

- Database Searching

- Documenting Your Search and Findings

- Discipline-Specific Literature Reviews

Ask Us! Cabell Library

As a student at VCU, VCU Libraries are here to help you succeed! This guide offers an introduction to conducting a literature review and provides links to the resources and tools we offer. To navigate, simply click the blue tabs to the left based on type of information you're needing.

If ever you are in need of research assistance, don't hesitate to consult a specialist based on your subject area.

Please provide feedback on this guide at any point by emailing Kelsey Cheshire, [email protected] .

What is a Literature Review?

A literature review is an essential component of every research project. Literature reviews ask: What do we know, or not know, about this particular issue/ topic/ subject?

How well you answer this question depends upon:

- the effectiveness of your search for information

- the quality & reliability of the sources you choose

- your ability to synthesize the sources you select

Literature reviews require “re-viewing” what credible scholars in the field have said, done, and found in order to help you:

- Identify what is currently known in your area of interest

- Establish an empirical/ theoretical/ foundation for your research

- Identify potential gaps in knowledge that you might fill

- Develop viable research questions and hypotheses

- Decide upon the scope of your research

- Demonstrate the importance of your research to the field

A literature review is not a descriptive summary of what you found. All works included in the review must be read, evaluated, and analyzed, and synthesized, meaning that relationships between the works must also be discussed.

- Next: Developing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Oct 16, 2023 1:53 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/lit-review

- Library Homepage

Literature Review: The What, Why and How-to Guide: Literature Reviews?

- Literature Reviews?

- Strategies to Finding Sources

- Keeping up with Research!

- Evaluating Sources & Literature Reviews

- Organizing for Writing

- Writing Literature Review

- Other Academic Writings

What is a Literature Review?

So, what is a literature review .

"A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available or a set of summaries." - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d)."The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it".

- Citation: "The Literature Review: A Few Tips on Conducting it"

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

Each field has a particular way to do reviews for academic research literature. In the social sciences and humanities the most common are:

- Narrative Reviews: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific research topic and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weaknesses, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section that summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : A type of literature review typical in History and related fields, e.g., Latin American studies. For example, the Latin American Research Review explains that the purpose of this type of review is to “(1) to familiarize readers with the subject, approach, arguments, and conclusions found in a group of books whose common focus is a historical period; a country or region within Latin America; or a practice, development, or issue of interest to specialists and others; (2) to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches; and (3) to probe the relation of these new books to previous work on the subject, especially canonical texts. Unlike individual book reviews, the cluster reviews found in LARR seek to address the state of the field or discipline and not solely the works at issue.” - LARR

What are the Goals of Creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what has been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed new light into a body of scholarship.

Where I can find examples of Literature Reviews?

Note: In the humanities, even if they don't use the term "literature review", they may have a dedicated chapter that reviewed the "critical bibliography" or they incorporated that review in the introduction or first chapter of the dissertation, book, or article.

- UCSB electronic theses and dissertations In partnership with the Graduate Division, the UC Santa Barbara Library is making available theses and dissertations produced by UCSB students. Currently included in ADRL are theses and dissertations that were originally filed electronically, starting in 2011. In future phases of ADRL, all theses and dissertations created by UCSB students may be digitized and made available.

Where to Find Standalone Literature Reviews

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature review looks at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic has changed over time.

- Find e-Journals for Standalone Literature Reviews The best way to get familiar with and to learn how to write literature reviews is by reading them. You can use our Journal Search option to find journals that specialize in publishing literature reviews from major disciplines like anthropology, sociology, etc. Usually these titles are called, "Annual Review of [discipline name] OR [Discipline name] Review. This option works best if you know the title of the publication you are looking for. Below are some examples of these journals! more... less... Journal Search can be found by hovering over the link for Research on the library website.

Social Sciences

- Annual Review of Anthropology

- Annual Review of Political Science

- Annual Review of Sociology

- Ethnic Studies Review

Hard science and health sciences:

- Annual Review of Biomedical Data Science

- Annual Review of Materials Science

- Systematic Review From journal site: "The journal Systematic Reviews encompasses all aspects of the design, conduct, and reporting of systematic reviews" in the health sciences.

- << Previous: Overview

- Next: Strategies to Finding Sources >>

- Last Updated: Mar 5, 2024 11:44 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.ucsb.edu/litreview

- Maps & Floorplans

- Libraries A-Z

- Ellis Library (main)

- Engineering Library

- Geological Sciences

- Journalism Library

- Law Library

- Mathematical Sciences

- MU Digital Collections

- Veterinary Medical

- More Libraries...

- Instructional Services

- Course Reserves

- Course Guides

- Schedule a Library Class

- Class Assessment Forms

- Recordings & Tutorials

- Research & Writing Help

- More class resources

- Places to Study

- Borrow, Request & Renew

- Call Numbers

- Computers, Printers, Scanners & Software

- Digital Media Lab

- Equipment Lending: Laptops, cameras, etc.

- Subject Librarians

- Writing Tutors

- More In the Library...

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

- Researcher Support

- Distance Learners

- International Students

- More Services for...

- View my MU Libraries Account (login & click on My Library Account)

- View my MOBIUS Checkouts

- Renew my Books (login & click on My Loans)

- Place a Hold on a Book

- Request Books from Depository

- View my ILL@MU Account

- Set Up Alerts in Databases

- More Account Information...

Introduction to Literature Reviews

Introduction.

- Step One: Define

- Step Two: Research

- Step Three: Write

- Suggested Readings

A literature review is a written work that :

- Compiles significant research published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers;

- Surveys scholarly articles, books, dissertations, conference proceedings, and other sources;

- Examines contrasting perspectives, theoretical approaches, methodologies, findings, results, conclusions.

- Reviews critically, analyzes, and synthesizes existing research on a topic; and,

- Performs a thorough “re” view, “overview”, or “look again” of past and current works on a subject, issue, or theory.

From these analyses, the writer then offers an overview of the current status of a particular area of knowledge from both a practical and theoretical perspective.

Literature reviews are important because they are usually a required step in a thesis proposal (Master's or PhD). The proposal will not be well-supported without a literature review. Also, literature reviews are important because they help you learn important authors and ideas in your field. This is useful for your coursework and your writing. Knowing key authors also helps you become acquainted with other researchers in your field.

Look at this diagram and imagine that your research is the "something new." This shows how your research should relate to major works and other sources.

Olivia Whitfield | Graduate Reference Assistant | 2012-2015

- Next: Step One: Define >>

- Last Updated: Jun 28, 2023 5:49 PM

- URL: https://libraryguides.missouri.edu/literaturereview

Literature Review: What is a Literature Review?

- Sample Searches

- Examples of Published Literature Reviews

- Researching Your Topic

- Subject Searching

- Google Scholar

- Track Your Work

- Citation Managers This link opens in a new window

- Citation Guides This link opens in a new window

- Tips on Writing Your Literature Review This link opens in a new window

- Research Help

Ask a Librarian

Chat with a Librarian

Lisle: (630) 829-6057 Mesa: (480) 878-7514 Toll Free: (877) 575-6050 Email: [email protected]

Book a Research Consultation Library Hours

Not Just for Graduate Students!

A literature review is an in-depth critical analysis of published scholarly research related to a specific topic. Published scholarly research (the "literature") may include journal articles, books, book chapters, dissertations and thesis, or conference proceedings.

A solid lit review must:

- be organized around and related directly to the thesis or research question you're developing

- synthesize results into a summary of what is and is not known

- identify areas of controversy in the literature

- formulate questions that need further research

Why Conduct a Literature Review?

- to distinguish what has been done from what needs to be done

- to discover important variables relevant to the topic

- to synthesize and gain new perspective

- to identify relationships between ideas and practices

- to establish the context of the topic

- to rationalize the significance of the problem

- to enhance and acquire subject vocabulary

- to understand the structure of the subject

- tp relate ideas and theory to applications

- to identify main methodologies and research techniques that have been used

- to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-art development

Questions to Consider

- What is the overarching question or problem your literature review seeks to address?

- How much familiarity do you already have with the field? Are you already familiar with common methodologies or professional vocabularies?

- What types of strategies or questions have others in your field pursued?

- How will you synthesize or summarize the information you gather?

- What do you or others perceive to be lacking in your field?

- Is your topic broad? How could it be narrowed?

- Can you articulate why your topic is important in your field?

- Next: Sample Searches >>

- Last Updated: Apr 25, 2024 3:34 PM

- URL: https://researchguides.ben.edu/lit-review

Kindlon Hall 5700 College Rd. Lisle, IL 60532 (630) 829-6050

Gillett Hall 225 E. Main St. Mesa, AZ 85201 (480) 878-7514

University Libraries

Literature review.

- What is a Literature Review?

- What is Its Purpose?

- 1. Select a Topic

- 2. Set the Topic in Context

- 3. Types of Information Sources

- 4. Use Information Sources

- 5. Get the Information

- 6. Organize / Manage the Information

- 7. Position the Literature Review

- 8. Write the Literature Review

A literature review is a comprehensive summary of previous research on a topic. The literature review surveys scholarly articles, books, and other sources relevant to a particular area of research. The review should enumerate, describe, summarize, objectively evaluate and clarify this previous research. It should give a theoretical base for the research and help you (the author) determine the nature of your research. The literature review acknowledges the work of previous researchers, and in so doing, assures the reader that your work has been well conceived. It is assumed that by mentioning a previous work in the field of study, that the author has read, evaluated, and assimiliated that work into the work at hand.

A literature review creates a "landscape" for the reader, giving her or him a full understanding of the developments in the field. This landscape informs the reader that the author has indeed assimilated all (or the vast majority of) previous, significant works in the field into her or his research.

"In writing the literature review, the purpose is to convey to the reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. The literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (eg. your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries.( http://www.writing.utoronto.ca/advice/specific-types-of-writing/literature-review )

Recommended Reading

- Next: What is Its Purpose? >>

- Last Updated: Oct 2, 2023 12:34 PM

Enhancing Searching as Learning (SAL) with Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Literature Review

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 June 2024

- Cite this conference paper

- Kok Khiang Lim ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7118-6864 8 &

- Chei Sian Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-0891-6526 8

Part of the book series: Communications in Computer and Information Science ((CCIS,volume 2117))

Included in the following conference series:

- International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction

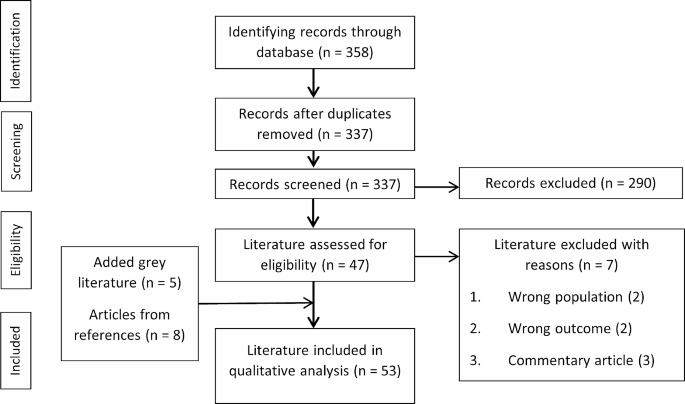

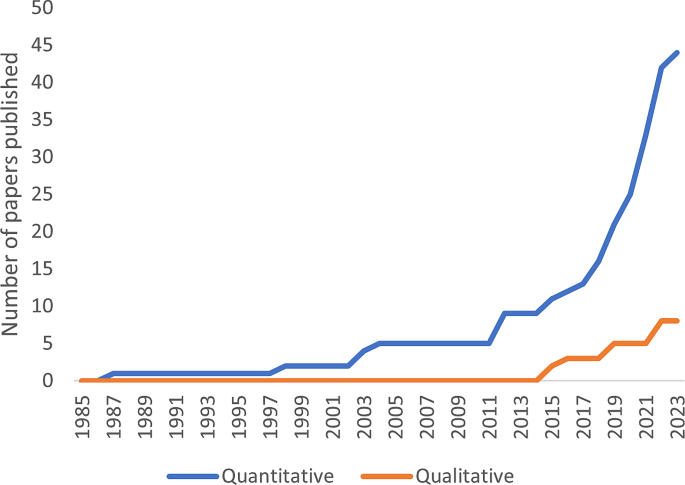

Searching as Learning (SAL), a learning process with potential knowledge gain during searches in a digital environment, is an emerging field in human-computer interaction research, especially with recent technological advancements in generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). According to SAL, the act of searching for the information itself can be a valuable learning experience. Many studies have investigated SAL’s learning perspective and facets supported by traditional search systems (e.g., web browsers), to access, search, and retrieve information to fulfill users’ learning intentions. However, the applications of GenAI, as well as their roles and disruption to the existing SAL process, are unclear. To address this gap, this study aims to shed light on the applicability of GenAI in enhancing the SAL process by conducting a systematic literature review.

First, we seek to define the concepts of ‘learning’ and ‘searching’ by examining the components of SAL in the literature and then detailing how SAL would have occurred. Next, the systematic literature review, guided by PRISMA, uses the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome) framework to develop searchable keywords and guide the literature review. Five major databases were searched, and literature that fulfilled the PICO’s criteria was included for review. Preliminary analysis shows that GenAI could improve and ease SAL human-computer interfaces that inevitably change the process and influence users’ learning behavior, such as how information is retrieved and consumed. Consequently, these opportunities posed concerns about information reliability, accuracy, and long-term effects on user behavior.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Disclosure of Interests

The authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Choo, C.W., Detlor, B., Turnbull, D.: Information seeking on the web: an integrated model of browsing and searching. First Monday 5 (2000). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v5i2.729

Wildemuth, B.M., Freund, L.: Assigning search tasks designed to elicit exploratory search behaviors. In: Proceedings of the Symposium on Human-Computer Interaction and Information Retrieval, pp. 1–10 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1145/2391224.2391228

Vakkari, P.: Searching as learning: a systematization based on literature. J. Inf. Sci. 42 , 7–18 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515615833

Article Google Scholar

Dhillon, M.K.: Online information seeking and higher education students. In: Chelton, M., Cool, C. (eds.) Youth Information- Seeking Behavior II: Context, Theories, Models, and Issues, pp. 165–205. Scarecrow Press, Lanham (2007)

Google Scholar

Chiu, T.K.F.: Future research recommendations for transforming higher education with generative AI. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 6 , 100197 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100197

Song, C.P., Song, Y.P.: Enhancing academic writing skills and motivation: assessing the efficacy of ChatGPT in AI-assisted language learning for EFL students. Front. Psychol. 14 , 1260843 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1260843

Malmström, H., Stöhr, C., Ou, A.W.: Chatbots and other AI for learning: a survey of use and views among university students in Sweden. Chalmers Stud. Commun. Learn. High. Educ. 1 (2023). https://doi.org/10.17196/cls.csclhe/2023/01

Abdaljaleel, M., et al.: A multinational study on the factors influencing university students’ attitudes and usage of ChatGPT. Sci. Rep. 14 , 1983 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52549-8

Stahl, B.C., Eke, D.: The ethics of ChatGPT – exploring the ethical issues of an emerging technology. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 74 , 102700 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2023.102700

Wu, X., Duan, R., Ni, J.: Unveiling security, privacy, and ethical concerns of ChatGPT. J. Inf. Intell. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiixd.2023.10.007

Pollock, A., Berge, E.: How to do a systematic review. Int. J. Stroke 13 , 138–156 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1747493017743796

Gimenez, P., Machado, M., Pinelli, C., Siqueira, S.: Investigating the learning perspective of searching as learning, a review of the state of the art. In: 31st Brazilian Symposium on Computers in Education, pp. 302–311 (2020). doi: https://doi.org/10.5753/cbie.sbie.2020.302

Kuhlthau, C.: Guided inquiry: school libraries in the 21st century. Sch. Libr. Worldw. 16 , 1–12 (2001). https://doi.org/10.29173/slw6797

Flavell, J.: Metacognition and cognitive monitoring: a new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. Am. Psychol. 34 , 906–911 (1979). https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.906

Pressley, M.: Metacognition and self-regulated comprehension. In: Farstrup, A.E., Samuel, S.J. (eds.) What Research Has to Say About Reading Instruction, pp. 291–309. International Reading Association, Newark (2002)

Hoyer, J.v., Pardi, G., Kammerer, Y., Holtz, P.: Metacognitive judgments in searching as learning (SAL) tasks: Insights on (mis-) calibration, multimedia usage, and confidence. Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Search as Learning with Multimedia Information, pp. 3–10. Association for Computing Machinery, Nice (2019)

Marchionini, G.: Exploratory search: from finding to understanding. Commun. ACM 49 , 41–46 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1145/1121949.1121979

https://openai.com/blog/chatgpt/

Niedbał, R., Sokołowski, A., Wrzalik, A.: Students’ use of the artificial intelligence language model in their learning process. Procedia Comput. Sci. 225 , 3059–3066 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2023.10.299

American Psychological Association. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2023/06/chatgpt-learning-tool

Page, M.J., et al.: The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 10 , 89 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01626-4

Fink, A.: Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 2nd edn. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks (2005)

Bach, T.A., Khan, A., Hallock, H., Beltrão, G., Sousa, S.: A systematic literature review of user trust in AI-enabled systems: an HCI perspective. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. 40, 1–16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2022.2138826

Floridi, L., Chiriatti, M.: GPT-3: Its nature, scope, limits, and consequences. Mind. Mach. 30 , 681–694 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11023-020-09548-1

Bandara, W., Miskon, S., Fielt, E.: A systematic, tool-supported method for conducting literature reviews in information systems. In: ECIS 2011 Proceedings 19th European Conference on Information Systems, pp. 1–13. AIS Electronic Library (AISeL)/Association for Information Systems (2011). https://eprints.qut.edu.au/42184/

Jo, H.: Understanding AI tool engagement: a study of ChatGPT usage and word-of-mouth among university students and office workers. Telematics Inform. 85 , 102067 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2023.102067

Jo, H., Park, D.H.: AI in the workplace: examining the effects of ChatGPT on information support and knowledge acquisition. Int. J. Hum.-Comput. Interact. (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2023.2278283

Murgia, E., Abbasiantaeb, Z., Aliannejadi, M., Huibers, T., Landoni, M., Pera, M.S.: ChatGPT in the classroom: a preliminary exploration on the feasibility of adapting ChatGPT to support children’s information discovery. In: Adjunct Proceedings of the 31st ACM Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, pp. 22–27 (2023). doi: https://doi.org/10.1145/3563359.3597399

Pellas, N.: The effects of generative AI platforms on undergraduates’ narrative intelligence and writing self-efficacy. Educ. Sci. 13 , 1155 (2023). https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13111155

Yilmaz, R., Karaoglan Yilmaz, F.G.: The effect of generative artificial intelligence (AI)-based tool use on students’ computational thinking skills, programming self-efficacy and motivation. Comput. Educ. Artif. Intell. 4 , 100147 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.caeai.2023.100147

Yilmaz, R., Karaoglan Yilmaz, F.G.: Augmented intelligence in programming learning: examining student views on the use of ChatGPT for programming learning. Comput. Hum. Behav. Artif. Hum. 1 , 100005 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chbah.2023.100005

Duong, C.D., Vu, T.N., Ngo, T.V.N.: Applying a modified technology acceptance model to explain higher education students’ usage of ChatGPT: a serial multiple mediation model with knowledge sharing as a moderator. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 21 , 100883 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100883

Rahman, M.S., Sabbir, M.M., Zhang, D.J., Moral, I.H., Hossain, G.M.S.: Examining students’ intention to use ChatGPT: does trust matter? Aust. J. Educ. Technol. 39 , 51–71 (2023). https://doi.org/10.14742/ajet.8956

Songsiengchai, S., Sereerat, B.O., Watananimitgul, W.: Leveraging artificial intelligence (AI): Chat GPT for effective English language learning among Thai students. Kurdish Stud. 11 , 359–373 (2023). https://doi.org/10.58262/ks.v11i3.027

Wandelt, S., Sun, X., Zhang, A.: AI-driven assistants for education and research? a case study on ChatGPT for air transport management. J. Air Transp. Manag. 113 , 102483 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jairtraman.2023.102483

Al-Sharafi, M.A., Al-Emran, M., Iranmanesh, M., Al-Qaysi, N., Iahad, N.A., Arpaci, I.: Understanding the impact of knowledge management factors on the sustainable use of AI-based chatbots for educational purposes using a hybrid SEM-ANN approach. Interact. Learn. Environ. 31 , 7491–7510 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2022.2075014

Arif, M., Qaisar, N., Kanwal, S.: Factors affecting students’ knowledge sharing over social media and individual creativity: an empirical investigation in Pakistan. Int. J. Manag. Educ. 20 , 100598 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2021.100598

Bouton, E., Tal, S.B., Asterhan, C.S.C.: Students, social network technology and learning in higher education: visions of collaborative knowledge construction vs. the reality of knowledge sharing. Internet High. Educ. 49 , 100787 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2020.100787

Proper, H.A., Bruza, P.D.: What is information discovery about? J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. 50 , 737–750 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-4571(1999)50:9%3c737::AID-ASI2%3e3.0.CO;2-C

Lee, C.T., Pan, L.-Y., Hsieh, S.H.: Artificial intelligent chatbots as brand promoters: a two-stage structural equation modeling - artificial neural network approach. Internet Res. 32 , 1329–1356 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-01-2021-0030

Holzwarth, M., Janiszewski, C., Neumann, M.M.: The influence of avatars on online consumer shopping behavior. J. Mark. 70 , 19–36 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1509/JMKG.70.4.019

Randall, W.L.: Narrative intelligence and the novelty of our lives. J. Aging Stud. 13 , 11–28 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0890-4065(99)80003-6

Rieh, S.Y., Collins-Thompson, K., Hansen, P., Lee, H.-J.: Towards searching as a learning process: a review of current perspectives and future directions. J. Inf. Sci. 42 , 19–34 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551515615841

Tayan, O., Hassan, A., Khankan, K., Askool, S.: Considerations for adapting higher education technology courses for AI large language models: a critical review of the impact of ChatGPT. Mach. Learn. Appl. 15 , 100513 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mlwa.2023.100513

Slyer, J.T.: Unanswered questions: implications of an empty review. JBI Evid. Synth. 14 , 1–2 (2016). https://doi.org/10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-002934

Yaffe, J., Montgomery, P., Hopewell, S., Shepard, L.D.: Empty reviews: a description and consideration of Cochrane systematic reviews with no included studies. PLoS ONE (2012). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0036626

Abdel Aziz, M.H., Rowe, C., Southwood, R., Nogid, A., Berman, S., Gustafson, K.: A scoping review of artificial intelligence within pharmacy education. Am. J. Pharm. Educ. 88 , 100615 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpe.2023.100615

Download references

Acknowledgments

This research is supported by the National Research Foundation, Singapore under its AI Singapore Programme (AISG Award No: AISG-GV-2023-013).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wee Kim Wee School of Communication and Information, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Kok Khiang Lim & Chei Sian Lee

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kok Khiang Lim .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

University of Crete and Foundation for Research and Technology - Hellas (FORTH), Heraklion, Crete, Greece

Constantine Stephanidis

Foundation for Research and Technology - Hellas (FORTH), Heraklion, Crete, Greece

Margherita Antona

Stavroula Ntoa

University of Central Florida, Orlando, FL, USA

Gavriel Salvendy

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2024 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Lim, K.K., Lee, C.S. (2024). Enhancing Searching as Learning (SAL) with Generative Artificial Intelligence: A Literature Review. In: Stephanidis, C., Antona, M., Ntoa, S., Salvendy, G. (eds) HCI International 2024 Posters. HCII 2024. Communications in Computer and Information Science, vol 2117. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-61953-3_17

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-61953-3_17

Published : 01 June 2024

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-61952-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-61953-3

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Behav Neurosci

- PMC10317209

Understanding health behavior change by motivation and reward mechanisms: a review of the literature

The global rise of lifestyle-related chronic diseases has engendered growing interest among various stakeholders including policymakers, scientists, healthcare professionals, and patients, regarding the effective management of health behavior change and the development of interventions that facilitate lifestyle modification. Consequently, a plethora of health behavior change theories has been developed with the intention of elucidating the mechanisms underlying health behavior change and identifying key domains that enhance the likelihood of successful outcomes. Until now, only few studies have taken into account neurobiological correlates underlying health behavior change processes. Recent progress in the neuroscience of motivation and reward systems has provided further insights into the relevance of such domains. The aim of this contribution is to review the latest explanations of health behavior change initiation and maintenance based on novel insights into motivation and reward mechanisms. Based on a systematic literature search in PubMed, PsycInfo, and Google Scholar, four articles were reviewed. As a result, a description of motivation and reward systems (approach/wanting = pleasure; aversion/avoiding = relief; assertion/non-wanting = quiescence) and their role in health behavior change processes is presented. Three central findings are discussed: (1) motivation and reward processes allow to distinguish between goal-oriented and stimulus-driven behavior, (2) approach motivation is the key driver of the individual process of behavior change until a new behavior is maintained and assertion motivation takes over, (3) behavior change techniques can be clustered based on motivation and reward processes according to their functional mechanisms into facilitating (= providing external resources), boosting (= strengthening internal reflective resources) and nudging (= activating internal affective resources). The strengths and limitations of these advances for intervention planning are highlighted and an agenda for testing the models as well as future research is proposed.

1. Introduction

The prevalence of lifestyle-related chronic diseases has increased dramatically in the last decades. Chronic diseases were responsible for 71% of all deaths occurring worldwide in 2019 ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 2022a ), of which about one third are premature deaths, i.e., happening to people aged between 30 and 69 years ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 2022a ). Diseases of the circulatory system like stroke and ischaemic heart disease accounted for 30% of all deaths in 2019 in OECD countries, followed by cancer (24%), diseases of the respiratory system (10%) and diabetes (3%) ( Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021 ). Individuals living with these conditions also face a major stress burden due to disability, in some cases already at young ages. Indeed, averaged across 26 OECD countries, more than one third of individuals aged 16 and over have been found to be living with longstanding illness or health problems ( Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development [OECD], 2021 ). In addition, comorbidities (multimorbidity) as well as individual physical and emotional suffering frequently occur ( Stewart et al., 1989 ; Moussavi et al., 2007 ; de Ridder et al., 2008 ), reducing overall quality of life ( Maresova et al., 2019 ).

These numbers and trends can in part be traced back to rising rates of obesity, sedentary behavior and poor nutrition, as well as other metabolic risk factors for chronic diseases including tobacco use and harmful alcohol intake. In addition, as diseases and comorbidities accumulate in older age, countries’ aging populations further influence these numbers ( Zhou et al., 2016 ). Indeed, most countries in the world have experienced, and will experience great demographic transitions. It has been estimated that between 2015 and 2050, the number of individuals aged 60 years and older will nearly double from 12 to 22%, with two billion people aged above 60 years by 2050 ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 2022b ). At the same time, life expectancy has risen from 67.5 years in 2000 to 72.9 years in 2020 at the world’s average ( The World Bank, 2022 ). Based on these projections, it can be assumed that the total number of individuals with longstanding illnesses or health problems will continue to rise.

The treatment of chronic diseases is often lengthy and intense, and is frequently accompanied by a reduced ability to work ( Seuring et al., 2015 ). While this can reduce the quality of life in patients further ( Jing et al., 2018 ), it can also affect an individual’s household financial resources ( Seuring et al., 2015 ). In low income settings, tremendous costs for treatment can quickly drain savings ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 2022a ). This, in return, may perpetuate people’s conditions, as it has been found that poverty is closely linked with the prevalence of chronic diseases: vulnerable and socially disadvantaged people tend to get ill quicker and have lower life expectancy than people of higher social positions ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 2022a ). The main reasons for this phenomenon are that economically vulnerable individuals are at greater risk of being exposed to harmful products, such as tobacco, tend to have unhealthy diets, and, in some countries, cities or neighborhoods, have limited access to health services. In fact, the average life expectancy at birth of people with low income is 4.4 (women) to 8.6 (men) years lower than of people in the highest of five income groups ( Lampert et al., 2019 ).

These costs on individuals are accompanied by costs for the healthcare system and society as a whole. Health expenditure related to diabetes, for example, is at least 966 billion USD per year worldwide, which represents a 316% increase over the last 15 years ( International Diabetes Federation [IDF], 2021 ). In Germany, the cost burden for diabetes type 2 treatment has been calculated to be on average 1.8 times higher than for other diseases ( Ulrich et al., 2016 ). Multimorbidity typically incurs greater health care costs ( Rizzo et al., 2015 ), measured by the use of medication as well as emergency department presentations and hospital admissions ( Chan et al., 2002 ). For example, Schneider et al. (2009) found that older adults in the United States with three or more chronic conditions utilized on average 25 times more hospital bed-days and had on average 14.6 times more hospital admissions than older adults without any chronic condition. Furthermore, with one additional chronic condition in older adults, the health care utilization costs increase near exponentially ( Lehnert et al., 2011 ). In addition to these financial impacts, chronic conditions tend to dwell on non-tangible resources, e.g., through time and energy spent on disease management by the patient and family members ( Ellrodt et al., 1997 ; Korff et al., 1998 ; Wagner, 2000 ). These circumstances call for shifting the focus to health care measures that help to prevent and improve chronic conditions according to patient needs in a cost-effective way.

There is compelling evidence to suggest that lifestyle changes can significantly improve the conditions of chronic diseases. Studies have demonstrated the positive impact of increased exercise, healthier nutrition, reduced alcohol intake, smoking cessation, and relaxation techniques on a range of chronic conditions ( Ornish et al., 1990 ; Knowler et al., 2002 ; Savoye et al., 2007 ; Alert et al., 2013 ; Cramer et al., 2014 ; Morris et al., 2019 ). These health behaviors can decrease the major metabolic risk factors for chronic diseases and premature deaths, including blood pressure, blood glucose, blood lipids, and obesity ( World Health Organisation [WHO], 2022a ). Remarkably, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes is predominantly attributable to lifestyle-related factors rather than genetic risks ( Langenberg et al., 2014 ). Moreover, lifestyle changes could prevent up to 70% of strokes and cases of colon cancer, 80% of coronary heart diseases, and 90% of diabetes cases ( Willett, 2002 ). Such findings highlight the tremendous potential of lifestyle modification interventions for public health outcomes.

It is widely recognized that individuals encounter challenges when endeavoring to attain their lifestyle goals. This is not unexpected, given that lifestyle change necessitates a series of individual choices that often require postponement of immediate pleasure in favor of prospective long-term health gains (a.k.a. delayed gratification, present bias, hyperbolic discounting, etc., see Stroebe et al., 2008 , 2013 ; Hall and Fong, 2015 ). Despite these obvious difficulties, practitioners, politicians and stakeholders aim to engage patients in health behavior change ( Esch, 2018 ). How consistently individuals pursue health behavior changes depends largely on how well they can overcome their innate present bias and on their endowment with other resources, such as their knowledge about health behavior change consequences, their beliefs in their ability to succeed, their self-regulation skills, self-efficacy, internal locus of control, engagement and empowerment ( Cane et al., 2012 ; Cheng et al., 2016 ; Sheeran et al., 2016 ; Ludwig et al., 2020 ; Cardoso Barbosa et al., 2021 ). Hence, a thorough understanding of health behavior change and interventions to support health behavior change taking into account individuals’ resources are necessary.

Numerous health behavior change theories have been devised, with a primary emphasis on reflective resources and willpower ( Kwasnicka et al., 2016 ). However, there is a scarcity of research on domains that are supported by, or rooted in, neuroscientific evidence. Notably, recent advances in the neuroscience of motivation and reward systems have revealed new insights into the importance of such domains ( Michaelsen and Esch, 2021 , 2022 ).