- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Philosophy and Religion

- Christianity

How to Write an Exegesis

Last Updated: December 19, 2023 Approved

This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff . Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards. wikiHow marks an article as reader-approved once it receives enough positive feedback. In this case, 96% of readers who voted found the article helpful, earning it our reader-approved status. This article has been viewed 107,637 times. Learn more...

An exegesis is an essay that focuses on a particular passage in the Bible. A good exegesis will use logic, critical thinking, and secondary sources to demonstrate a deeper understanding of the passage. You may be required to write an exegesis for a Bible study class or write one to broaden your understanding of the Bible. Start by taking notes on the passage and making an outline for the essay. Then, write the exegesis using your interpretations and your research. Always revise the exegesis once you are done so it is at its best.

Starting the Exegesis

- You may also want to read the passage from a number of different translations aloud so you get a better sense of it. Though you will choose only one translation of the passage for the exegesis, it doesn't hurt to look at other translations.

- You should also consider the grammar and syntax of the passage. Notice the structure of the sentences, the tenses of the verbs, as well as the phrases and clauses used.

- For example, you may circle words like "sow," "root," and "soil" in the passage because you think they are important.

- You may also note that the passage ends with "Whoever has ears, let them hear," which is the standard refrain for a parable in the Bible.

- You can also look for articles, essays, and commentaries that discuss the literary genre of the passage as well as any themes or ideas that you notice in the passage.

- Section 1:Introduction

- Section 2: Commentary on the passage

- Section 3: Interpretation of the passage

- Section 4: Conclusion

- Section 5: Bibliography

Writing the Exegesis

- You can also mention the literary genre, such as whether the passage is a hymn or a parable.

- For example, you may have a thesis statement like, “In this Bible passage, one learns about the value of a good foundation for inner and outer growth.”

- For example, if you were writing about Matthew 13:1-8, you may discuss the language and sentence structure of the parable. You may also talk about how the passage uses nature as a metaphor for personal growth.

- You can also discuss the broader context of the passage, including its historical or social significance. Provide context around how the passage has been interpreted by others, such as theological scholars and thinkers.

- If you are writing the exegesis for a class, ask the instructor which citation style they prefer and use it in your essay.

- Your instructor should specify which type of citation style they want you to use for the bibliography.

Polishing the Exegesis

- You can also try reading the essay backwards to catch spelling errors, as this will force you to focus on each word to confirm it is spelled correctly.

- You should also revise the essay to ensure it is not too long. If there is a word count for the exegesis, make sure you do not go over it.

Community Q&A

You Might Also Like

About This Article

An exegesis is an essay that deconstructs and analyzes a Bible passage. To write an exegesis, first read your chosen Bible passage carefully and take notes on the interesting parts. You should also read other secondary texts about your passage, like theological articles and commentaries, to help you build your argument. To structure your exegesis, start by introducing your passage and providing a thesis statement that sums up your key ideas. Then, expand your argument over the next few paragraphs. Use quotes from the passage and from your secondary sources to strengthen your argument. Finish your exegesis with a conclusion that reaffirms your key points. For more tips, including how to get feedback on your exegesis, read on! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Reader Success Stories

Lesley Curtis

Jan 3, 2021

Did this article help you?

Thabitha Mofokeng

Aug 30, 2019

Dana Wilson

Nov 2, 2018

Selvaraj Paulraj

Aug 8, 2022

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

wikiHow Tech Help Pro:

Develop the tech skills you need for work and life

How To Write Bible Verses In An Essay

- by Samuel Solomon

- June 11, 2023

- 7 minute read

Incorporating Bible verses in an essay can significantly enhance the depth, credibility, and persuasiveness of the message being conveyed.

The Bible is a revered and authoritative text for millions of people worldwide, containing profound wisdom, moral teachings, and spiritual insights.

By including relevant Bible verses, writers can tap into this rich source of knowledge and connect with readers on a deeper level and learn how to write Bible verses in an essay.

The purpose of this article is to provide practical guidance and tips for writers on how to effectively incorporate Bible verses into their essays.

Understanding the significance of context, selecting appropriate verses, and interpreting them correctly are essential elements in successfully integrating Bible verses.

By offering insights and strategies, this article aims to help writers utilize Bible verses in a thoughtful and impactful manner.

1. Understanding the Context

choose relevant bible verses that align with the essay’s theme or topic:.

When selecting Bible verses to include in an essay, it is crucial to ensure their relevance to the essay’s theme or topic.

The chosen verses should provide valuable insights, support arguments, or reinforce the central message of the essay.

By carefully considering the essay’s focus, writers can identify verses that effectively contribute to the overall coherence and depth of their writing.

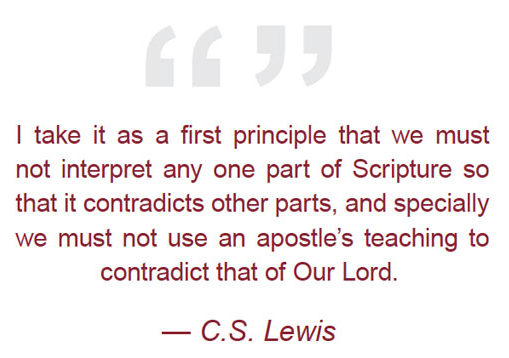

Study the verses in their biblical context to grasp their meaning and intended message:

To fully comprehend the meaning and intended message of selected Bible verses, it is essential to study them within their biblical context.

Reading the surrounding verses, chapters, or entire books helps to understand the historical, narrative, or theological framework in which the verses were originally written.

This contextual understanding enables writers to accurately interpret and effectively convey the intended meaning of the verses in their essay.

Consider the historical and cultural background to enhance interpretation:

The historical and cultural background of biblical texts can provide valuable insights into their meaning and significance.

Considering the historical context, such as the time period, societal norms, and cultural practices prevalent during the biblical era, can shed light on the original intent of the verses.

This understanding allows writers to provide a more nuanced interpretation and present the verses in a manner that resonates with contemporary readers.

2. Selecting Appropriate Verses

Identify key themes or concepts that relate to your essay’s subject matter:.

To select appropriate Bible verses, it is essential to identify the key themes or concepts that are relevant to your essay’s subject matter.

Consider the main ideas or arguments you are presenting and determine the specific biblical teachings or principles that align with those themes. By pinpointing the core aspects of your essay, you can then search for verses that directly address or support those themes.

Conduct thorough research to find verses that address those themes:

Once you have identified the key themes, conduct thorough research to find Bible verses that specifically address or explore those themes.

Utilize concordances, Bible study guides, or online resources to search for verses related to your chosen topics. Take the time to read and evaluate different passages to find the most relevant and impactful verses that will enrich your essay.

Seek guidance from biblical commentaries or scholarly sources for deeper understanding:

To gain a deeper understanding of the selected verses and their context, it can be helpful to consult biblical commentaries or scholarly sources.

These resources provide valuable insights, interpretations, and historical context that can enrich your understanding of the verses.

By seeking guidance from reputable commentaries or scholarly works, you can gain a broader perspective and ensure the accurate representation of the verses in your essay.

3. Introducing Bible Verses

Use introductory phrases or statements to prepare readers for the biblical quote:.

When incorporating Bible verses, it is important to prepare readers for the upcoming quote by using introductory phrases or statements.

These phrases can provide a smooth transition and signal to the readers that a biblical reference is about to be presented.

For example, you can use phrases like “According to Scripture” or “In the words of the Apostle Paul” to indicate that a verse is forthcoming.

Provide context or a brief explanation before quoting the verse:

Before quoting the verse, provide some context or a brief explanation to help readers understand its relevance and intended meaning within the essay.

Share a concise summary of the situation or event described in the verse or provide a brief overview of the biblical narrative from which the verse is taken. This context will assist readers in grasping the significance of the verse in relation to your essay’s argument or message.

Consider using the author’s name and the book and chapter of the Bible for clarity:

To ensure clarity and accuracy, consider including the author’s name, book, and chapter of the Bible when introducing the verse .

For example, you can write “As the apostle Paul writes in Romans 12:2” or “In the book of Psalms, chapter 23 , David proclaims.” This citation style provides clear attribution and allows readers to locate the verse easily if they wish to further explore the context.

4. Quoting and Formatting Bible Verses

follow the appropriate citation style (e.g., mla, apa, chicago) for bible references:.

When quoting Bible verses in your essay, it is important to adhere to the specific citation style required by your academic institution or the guidelines you are following.

Different citation styles may have variations in how Bible references are formatted , such as the placement of commas, abbreviations, or italics. Ensure you are familiar with the specific guidelines for citing Bible verses in the chosen citation style.

Quote verses accurately, including chapter and verse numbers:

When quoting Bible verses, accuracy is crucial. Include the chapter and verse numbers to provide a clear reference for readers.

This ensures that readers can locate the verse easily and verify the information. For example, if quoting John 3:16 , make sure to include both the chapter and verse number in the citation.

Use quotation marks or block quotes, depending on the citation style:

Depending on the citation style, you may need to use quotation marks or block quotes to distinguish the quoted Bible verses from the rest of your text.

Quotation marks are typically used for shorter verses or when the verse is incorporated within a sentence.

Block quotes, on the other hand, are used for longer verses or when you want to set the quoted text apart from the main body of your essay. Familiarize yourself with the specific guidelines of the chosen citation style to ensure proper formatting.

5.Interpreting and Analyzing Bible Verses

Analyze the meaning and significance of the quoted verse within the essay’s context:.

After quoting a Bible verse, it is crucial to analyze its meaning and significance within the context of your essay.

Consider the verse’s relevance to your argument or thesis and explore its deeper implications.

Examine the words, themes, and ideas expressed in the verse and reflect on how they contribute to the overall message of your essay.

Provide your interpretation and insights, relating the verse to your essay’s argument or thesis:

As the writer, it is important to provide your own interpretation and insights when analyzing Bible verses.

Share your understanding of the verse and its connection to your essay’s argument or thesis.

Explain how the verse supports or strengthens your main ideas and provide a clear explanation of the verse’s relevance within the context of your essay.

Support your analysis with additional biblical references or scholarly sources, if applicable:

If relevant and necessary, support your analysis of the quoted Bible verse with additional biblical references or scholarly sources.

This can help provide further context, expand on the themes or ideas presented in the verse, and offer a well-rounded understanding of the topic. Use reputable commentaries, scholarly articles, or other scholarly works to support and enhance your analysis, if appropriate.

6. Reflecting on Personal Application

Discuss how the quoted verse relates to your personal beliefs or experiences:.

After analyzing and interpreting the quoted verse, discuss how it relates to your personal beliefs or experiences.

Share how the verse resonates with you on a personal level and explain why it holds significance in your own life. This personal reflection adds depth and authenticity to your essay, allowing readers to connect with you on a more personal and relatable level.

Share insights or lessons learned from the verse and how it impacts your perspective:

Reflect on the insights or lessons you have gained from the quoted verse and discuss how it has impacted your perspective or understanding.

Share any transformative or enlightening experiences that have resulted from engaging with the verse.

By sharing your personal insights, you invite readers to consider their own perspectives and potentially find meaning or inspiration in the verse as well.

Encourage readers to reflect on the verse’s application in their own lives:

encourage readers to reflect on the verse’s application in their own lives. Invite them to consider how the verse’s teachings, principles, or messages can be relevant and impactful in their own personal journeys.

By prompting readers to reflect and apply the verse’s wisdom to their own lives, you empower them to engage with the material on a deeper level and potentially experience personal growth or transformation.

it is important to emphasize the significance of effectively incorporating Bible verses in essays.

Bible verses carry profound wisdom, moral teachings , and spiritual insights that can add depth and credibility to your writing.

By integrating relevant verses, you tap into a powerful source of guidance and inspiration that resonates with readers on a deeper level.

Incorporating Bible verses effectively allows you to enrich your arguments, strengthen your message, and engage with readers in a meaningful way.

- how to write bible verses in an essay

Samuel Solomon

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

43 Encouraging Bible Verses About Confidence And Self Esteem

31 best proverbs on listening, you may also like.

- 6 minute read

19 Christian Prayers for New Year

- November 21, 2023

- 8 minute read

27 Bible Verse For Confirmation

- 9 minute read

47 Bible Verses With Grace

- May 25, 2023

47 Bible Verses About Peace And Love

- March 10, 2023

- 10 minute read

73 Bible Verses About Togetherness

- April 23, 2023

How To Seek God

- May 15, 2023

Student Sign In

Sign in to begin browsing the members areas and interracting with the community.

Student Resources

- Quisque sit amet est et sapien ullamcorper.

- Quisque sit amet est et sapien ullamcorper pharetra.

- Quisque sit amet est et sapien.

Community Tools

Biblical studies.

- Applied Biblical Studies

- Online Extension Programme

- Extension Class Programme

- Module Registration Form for Distance Learning Programme

- Introduction to Module (INT01)

- INT01 Module Contents

- Advice on How to Study by Distance Learning

- INT01 Unit One

- INT01 Unit Two

- INT01 Unit Three

- INT01 Unit Four

- 1. Introduction to Unit Five

- 2. Unit Five Assignment Instructions

- 3. Step One: Pray

- 4. Step Two: Read the question

- 5. Step Three: Start with what you know

- 6. Step Four: Construct an outline

- 7. Step Five: Research

- 8. Step Five (continued): Back to our research

- 9. Step Five and a Half: Taking notes

- 10. Step Five (continued): Keep researching

- 11. Step Six: More reading and more research

- 12. Step Seven: Repeat Steps One and Two

- 13. Step Eight: Writing the essay - arranging your material

- 14. Step Nine: Writing the essay - getting it down on paper

- 15. Some Further Thoughts on Style

- 16. Step Ten: Revision

- 17. Optional Extras

- 18. Unit Five Checklist and Self Assessment

- INT01 Bibliography

- DLP Module feedback

- DLP Module payments

- BiBloS Magazine

13. Step Eight: Writing the essay – arranging your material

Having undertaken the bulk of your reading and research, it is now time to

A Thesis Statement

Here is mine:

Who was Amos, what did he achieve, and why did he do it?

On reflection, I may decide that I do not want my Thesis Statement to be a question so I can recast this as:

A survey of the life of the prophet Amos outlining his achievements and discussing his motivation.

You are not obliged to agree with my thesis statement but if yours is radically different you had better have some good reasons to be able to defend your thesis.

Checking for relevance

Looking for central points.

Look at how your essay can be structured . By now it should be apparent that you have lots of material on some aspects of the essay so use these as your central points (“chapter” sounds too big). Have you found out lots about what it means to be a prophet? Use this as a key point. Or has your research given you plenty of material on the religious life of eighth century Israel? Then focus on this. Always remembering that your essay is about the prophet Amos and that you need to give specific attention to him as well as more general attention to his background. Look at your provisional outline from Step Four.

Now is the time to move everything into its final position.

Ordering your points

A. Introduction B. Judah and Israel in the Eighth Century B.C. C. The Call of the Prophet Amos D. The Mission of the Prophet to Israel E. The Book of Amos F. Conclusion G. References

We have not yet said anything about the “Introduction” and “Conclusion” but you need both, so put them in. We can fill in the details later.

“Judah and Israel in the Eighth Century B.C.” is background. The material needs to be covered but not in so much detail that it dominates the essay. Keep to the point!

“B.C.” is a standard abbreviation (for “Before Christ”) but be aware that some prefer the politically correct “B.C.E.” for “Before the Christian / Common Era”. The policy of the British Bible School is to use the traditional and Christ-honouring “A.D.” and “B.C.” although whether or not you use the full points is up to you: AD and BC seem to work just as well without them.

“The Call of the Prophet Amos” could include some background material on the call of prophets in general – but only in so far as it helps us to keep moving towards our goal. If you have found some useful material on the call of prophets in general you could document it within a footnote so you can return to it later without it taking over your essay on Amos.

“The Mission of the Prophet to Israel” needs some background. What was the problem and why did God have to send a Judahite to Israel to address this problem? This section should send us into the text of the Book of Amos for our answers.

“The Book of Amos” might need an outline of the book itself and you may wish to ask who wrote it and when and also how much of the record is historically accurate. Sceptics will be sceptical here but you should be able to find some responses that defend the reliability of Scripture. Again, your arguments may need to be summarised in footnotes to keep your essay manageable.

“References” will list all sources from which you quoted both directly (within quotation marks) and indirectly (as summaries of what was said) as well as all other sources that have helped you.

A logical sequence

B. Judah and Israel in the Eighth Century B.C.

1. Judah: loyal to the House of David

2. Israel and the Sin of Jeroboam the Son of Nebat

3. Israel During the Reign of Jeroboam II

We could say more but too much background is too much.

On a more serious level, it is important to prepare carefully when writing about a complex subject. Your object throughout is to sort your material into a few simply-arranged groups and sometimes your research and preparation will take longer than the writing, which can be disappointing: all that work to produce a couple of paragraphs! But if you can get to the point and keep to the point every word should make a contribution and we, when we assess your essays, look for quality not quantity.

A reasonable conclusion

Make sure your conclusion is a consequence of what you have written. If you write something along the lines of “Amos is therefore one of the greatest prophets in the Bible” are you certain the body of your essay has in fact shown this to be true?

Reviewing headings

Review your title and sub-headings critically. They should identify and not merely describe the subject matter under them. Do not try to be too clever. You are not writing headlines for a newspaper and amusing puns and other types of word play are not appropriate in what is intended to be a serious piece of work. Brevity is desirable but three or four precise and informative words are better one or two vague ones.

Visual aids

Consider what use you can make of visual aids. Maps, timelines, photographs, all can help get your point across but do not use them merely for decorative purposes or filler. A map showing Tekoa in relation to Jerusalem and Bethel is going to be much clearer than trying to describe it. Do not forget that all visuals need a title and if you have taken them from another source you must give appropriate credit.

Checking footnotes

- To give full details of quotations or references given in the text. (Some prefer to include Biblical references within parentheses in the text rather than relegating them to footnotes. This is a matter of personal style.)

- To indicate authorities or sources of additional information.

- To show that you are aware of alternative points of view.

A footnote is made by placing a superscript number 1 after the quotation and the same number at the foot (bottom) of the page with the comment or bibliographic details in a smaller font size if typing or in your usual handwriting but under a ruled line if writing by hand so as to separate the footnotes from the body of the text. For example:

Some doubt the necessity of Bible study but most Christians would disagree. As John Job says:

“The purpose of Bible study is thus that the message of a particular passage should become part of us. This is our objective in the long run with the Bible as a whole. This aim may be achieved, as we have made clear, in a variety of ways, but it can be achieved only with effort.” 2

And at the bottom of the page we see: (see below)

It is worth introducing two Latin phrases that you often meet in footnotes: ibid. and op. cit. Both are in italics as they are foreign words (underline them if writing by hand) and both have full points after them as they are abbreviations. Ibid. is short for ibidem , “in the same place” and is used if the same source is used again directly after the first quote. If you quote from the same source after quoting from another source in between then the author’s surname (or the editor’s name, if appropriate) is given, followed by op. cit. or loc. cit . followed by the page number. Op. cit. is short for opere citato , “in the work cited” and loc. cit. is loco citato , “in the place cited”. Do not worry – you will get used to all this jargon. Here is another good one before you get sick of all this Latin: sic, “thus”.

This common word is used by writers and editors to indicate an apparent misspelling or a doubtful word or phrase in a source being quoted. ‘This dessiccant [ sic ] is useless.’ ‘The meeting was the most fortuitous [ sic ] I ever attended.’ Insertion of sic in these examples absolves the quoter of misspelling the word ‘desiccant’ and misusing the word ‘fortuitous’ and lays the blame – if blame it is – on the source quoted.

(It is not generally considered necessary to give page numbers when quoting from a dictionary as the reader can be assumed to know that these are arranged alphabetically and so the entry for sic comes after sesquipedalian verba (“oppressively long words”) and before sic itur ad astra (“this is the path to immortality”) but I do not suppose that this is a major point.)

< Step Seven: Repeat One & Two Step Nine: Writing >

- A little numeral above the type line

- Job, John B., Studying God’s Word, 1972:10

Sign in to your account

- Search Search

How to Write a Paper on a Biblical or Theological Topic

Writing research papers is an excellent way to learn because it trains you to gather information, interpret it, and persuasively present an informed opinion. The process teaches you a great deal, but it also equips you to contribute to ongoing discussions on a given topic.

Here’s the basic process of writing a research paper on a biblical or theological topic, either for a class or for your own personal research. Start at the top, or skip to what topic interests you most.

- Pick a topic

- Research your topic

- Construct an outline

- Draft your paper

- Revise and refine

Pick a Topic

Choosing the topic you want to research is often easier said than done. But perhaps the best advice to get the ball rolling is to narrow your scope. When your topic is too broad, you’ll likely find too much information (much of it unhelpful). But when your topic is appropriately focused, you can hone in on the information you need to gather and get down to the business of interpreting it.

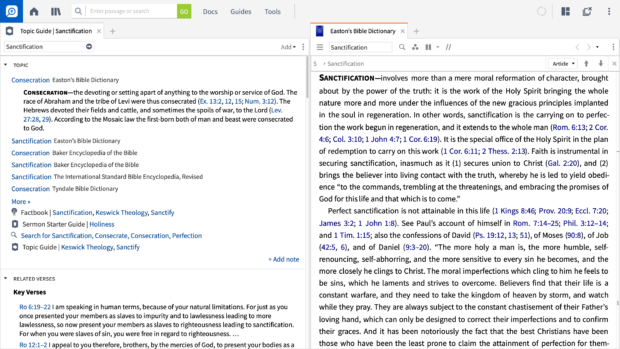

For example, choosing to write a paper on the topic of sanctification is too broad to be helpful. But if you narrow your focus to a specific question about sanctification (for example: How do spiritual disciplines contribute to our sanctification?), you’ll find better direction for your research.

Remember, you don’t have to be an expert on the question you want to find an answer to—that’s what the research process will accomplish. You should, however, have an interest in the question and in finding an answer (or several!) to it.

For more on the process of researching and writing a paper, check out these resources:

- The Craft of Research – particularly chapter 3

- Writing & Research: A Guide for Theological Students by Kevin Gary Smith

- Logos Academic Blog: Work with Librarians to Help Students Write Better Papers

Logos Theological Topic Workflow

The Theological Topic Study Workflow in Logos guides you through the steps of studying a theological topic. It taps into the Lexham Survey of Theology and the built-in Theology Guide to give you the topic’s broader context, basic concepts, and issues associated with the topic. Review the biblical support and go deeper in your theological study by reading relevant sections from systematic theologies.

Research Your Topic

With your topic selected, it’s time to find the resources you’re going to use and dig into them. You may find that one resource offers the best discussion of your topic, but you can’t stop there! Researching well means considering opinions that differ from each other (and probably from your own). It’s in the conversation that emerges from engaging with multiple perspectives on a topic that real insight and understanding emerge.

Start the research phase by reviewing literature and building your bibliography, then consult standard sources and peer-reviewed journals.

1. Conduct a literature review and build your bibliography

The process of conducting a literature review and building a bibliography is an iterative process. It’s not a one-time step but a step you’ll return to repeatedly as you move through your research.

Essentially, in this step, you’re discovering what resources exist and cataloging them. As you begin to read the resources you discover, you’ll likely find references to other works that you’ll then want to read.

Logos Topic Guide

The Topic Guide gathers information from your library about a topic or concept. Using the Logos Controlled Vocabulary dataset , the guide finds topics in your Bible dictionaries and other resources that correspond to the key term you enter.

2. Consult standard sources

Encyclopedias, commentaries, theological dictionaries, concordances, and other theological reference tools contain useful information that will orient you to the topic you’ve selected and its context, but their biggest help to you at this stage will in their bibliographies. Be sure to check the cross-references often.

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, rev. ed. by E. A. Livingstone and F. L. Cross

The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, since its first appearance in 1957, has established itself as the indispensable one-volume reference work on all aspects of the Christian Church. This Revised Edition, published in 2005, builds on the unrivaled reputation of the previous editions. Revised and updated, it reflects changes in academic opinion and Church organization.

Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity (3 vols.) by Angelo Di Berardino

The Encyclopedia of Ancient Christianity covers eight centuries of the Christian church and comprises 3,220 entries by a team of 266 scholars from 26 countries representing a variety of Christian traditions. It draws upon such fields as archaeology, art and architecture, biography, cultural studies, ecclesiology, geography, history, philosophy, and theology.

Theological Dictionary of the New Testament (TDNT) (10 vols.) by Gerhard Kittel, Gerhard Friedrich, Geoffrey William Bromiley

This monumental reference work, complete in ten volumes, is the authorized and unabridged translation of the famous Theologisches Wörterbuch zum Neuen Testament, known commonly as “Kittel” and considered by many scholars to be the best New Testament dictionary ever compiled.

3. Consult peer-reviewed journals

Even if you’re writing on a single text (like John 15:1–8 or Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite’s The Divine Names), you need to see what your contemporaries have to say about it to situate your research in its context. This means consulting peer-reviewed journals. As you read, you’ll discover where scholars agree and disagree and how the study of that topic has advanced over time.

Journal of Hebrew Scriptures (11 vols.)

The Journal of Hebrew Scriptures is an academic, peer-reviewed journal devoted to the study of the Hebrew Bible, and provides a forum for critical scholarly exchange. You’ll find hundreds of articles from top Hebrew scholars on trends in Hebrew and Old Testament scholarship, including historical, literary, textual, and interpretive topics.

Construct an Outline

This step is incredibly important, but it’s often overlooked. Start by refining your topic based on your research, then arrange your notes and research materials into a clear outline that will guide you toward a convincing and coherent argument.

See chapters 8 and 9 of The Craft of Research for more guidance on constructing your outline.

Draft Your Paper

You are now ready to draft your paper. Your initial focus is to expand your outline into paragraph form as straightforwardly as possible. While your outline will be essential as you draft, you don’t have to stick to it absolutely. You may discover as you write that a different structure or organization will better advance your argument. While you’re at it, add relevant quotations from your research to clarify your points or support your arguments.

Revise and Refine

Notice the word “draft” in the previous step. That word is intentionally selected because, arguably, the most important part of the writing process is in your revisions. Drafting gets the ball rolling, but revising is where you refine and revise your previous drafts, ensuring your argument is clear and forceful.

Before you send your final paper, you’ll want to make sure you’re writing clearly and using the right style. If you are in school, follow the rules of your academic handbook. If not, adopt a common style guide like APA, Turabian, or the SBL Handbook of Style , and consult online guides like EasyBib or the Chicago Manual of Style for help. You can also find helpful writing advice in The Elements of Style .

If there are multiple paragraphs, just add another paragraph tag. If you need more padding, use an additional text block section as you see below.

While this structure is helpful, you may find that some variation of it works better for you. Go with what works because, at the end of the day, a thoroughly researched and well-written paper is what you’re after.

See how Logos can power research and aid you in the writing process.

Logos Staff

Logos is the largest developer of tools that empower Christians to go deeper in the Bible.

Related articles

Dividing to Multiply: God’s Pattern of Creation across the Canon

The 16 Best Books on Ecclesiology, Selected by a Theologian

Ecclesiology: What Do We Believe about the Church?

1 Thessalonians 4 & the Truth about the “Secret” Rapture

Your email address has been added

- Research and Course Guides

- Biblical Exegesis

Introduction

Biblical exegesis: introduction.

1. Choose a Passage

2. Examine the Historical, Cultural, and Literary Background

3. Perform Exegesis of Each Verse

4. Offer an Overall Interpretation

5. Provide an Application of the Passage

- 6. Finding Books

- 7. Finding Articles

- 8. Citing Sources

- Theological Reflection Papers

This research guide is designed around the basic types of Bible resources available to our students for beginning a biblical exegesis paper . Many instructors also design their assignments with these basic research resources in mind. Therefore this guide has several sections based on the most common types of Bible tools.

- Backgrounds

- Commentaries

- Journal Articles

Be certain that you fully understand your professor’s instructions for your paper (often an exegesis of a text), since there is room in the process for individual variations. Needless to say, always follow your instructor's requirements and advice!

The typical steps involved in doing exegetical work can include the following:

- Establish or orient the context of the pericope in the Biblical book as a whole

- Examine the historical context or setting

- Analyze the text. This can involve literary, textual, grammatical, and/or lexical analysis

- Critical analysis: employing various critical methods to ask questions of the texts

- Theological analysis

- Your analysis and/or application

A pericope comes from the Greek language, meaning, "a cutting-out". It is a set of verses that forms one coherent unit or thought, thus forming a short passage suitable for public reading from a text, that usually refers to sacred scripture.

Steps in writing an exegesis paper.

Although your professor may have specific instructions that differ from what this guide presents, here are the basic steps common to most exegesis papers. You may go step-by-step, or jump to the topic of interest to you.

There is an additional thing you need to consider:

* Document Your Sources Correctly (See Citing Materials tab above).

First, Choose a Passage.

Oxford Biblical Studies Online

The most respected and authoritative biblical reference titles now online

Oxford Biblical Studies Online

Oxford Biblical Studies Online provides a comprehensive resource for the study of the Bible and biblical history. It contains six essential OUP Bible texts, including the latest edition of the New Oxford Annotated Bible, as well as deuterocanonical collections, Concordances, and the Oxford Bible Commentary. Search across multiple versions of the Bible, and compare different texts and commentaries in an innovative side-by-side view

Biblical studies & exegesis.

- Bible Atlas From Credo Reference collection

- Oxford Companion to Bible Limited background information

- Blackwell Companion to the Bible and Culture A Blackwell Reference Online collection title.

- Oxford Guide to People and Places of the Bible Quick look ups

- Blackwell Companion to the Hebrew Bible

New American Bible Online

- USCCB - New American Bible Online Also has the Church's daily readings....

Online Sources

Bible gateway

The Bible Gateway is a tool for reading and researching scripture online -- all in the language or translation of your choice!

Electronic New Testament Educational Resources

B iblica : Bibles Online

Maintained by Biblica. Biblica is the new name for IBS-STL Global. IBS-STL launched a new identity, including a new name—Biblica—to reflect its expanding vision and focus for transforming lives through God's Word. The new name is part of a rebranding process that began with the merger of International Bible Society and Send the Light in 2007.

A RTFL Project: Multilingual Bibles

Biblia Clerus: Biblical Commentaries Index

Specifically Catholic commentaries on books of the Bible. Part of the larger Biblia Clerus resource.

- Blue Letter Bible

Hermeneia Online Commentaries

Oremus Bible Browser

- Oremus Bible Browser Includes the New Revised Standard Version. Online bible browsers that can help you find specific passages or terms. You should uncheck hide verse numbers. You can search for a particular passage or a key term such as “Abraham” or “covenant”. You tell the browser in which book or range of biblical books to look. It will pop up the passages with some context and provide a link to the passages in the chapters in which they occur. You can also tell the browser to pop up a specific biblical passage. For example, Exodus 20:1-25.

Pronunciation

- Bible Pronunciation Guide Audio files for Bible words.

Oldest relatively complete manuscript of the Bible

Biblical studies organizations.

Society of Biblical Literature

American Bible Society

Catholic Biblical Association of America

Catholic Sources

- Catholic Resources for Bible, Liturgy, Art, and Theology

Bibles and Added Resources

Writing Research Papers

- The Purdue University Writing Center Website on Research papers -

Other Research Guides that May Help You

- An Introduction to Theology & Religion Resources

- Bible LITE - Introductory Sources Only the most useful databases, reference tools and books for introductory level Biblical research.

- Historical Jesus Examines the life of Jesus of Nazareth and considers how much the historian is able to reconstruct the life of Jesus using the historical method.

- Moral Theology

- History of the Classical World

- Citing Theological Sources: How to Do A Bibliography

Credit where credit is due:

- Adapted from a Research Guide from Azuza Pacific Univeristy Azuza's guide was created by Dr. Kenneth D. Litwak, Reference Instructor, University Libraries, October, 2008, and posted by Michele Spomer of Azuza Pacific..

- Next: 1. Choose a Passage >>

- Last Updated: May 10, 2024 11:35 AM

- URL: https://libguides.stthomas.edu/c.php?g=88712

© 2023 University of St. Thomas, Minnesota

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

Andy Naselli

Thoughts on theology, how to write a theology essay.

September 19, 2012 by Andy Naselli

Michael P. Jensen. How to Write a Theology Essay . London: Latimer Trust, 2012. 78 pp.

Each of the twenty chapters (titles in bold below) ends with a bullet-point summary:

1. How not to lose heart before you start

- The topics of theology really matter

- The knowledge of God is not the preserve of the very clever

- Starting to write theology is a challenge that can be fun!

2. What is theology in any case?

- Theology is a species of reason, subject to the Word of God

- Theology is a form of speech

- Theology is evangelical: it about God and his deeds

- Theology is evangelistic: it is an invitation to submit to the Lordship of Christ

3. What is a theology essay?

- An essay is an invitation to persuade

- The object of the theology essay is to say true things about God

- The theology essay deals with ideas and concepts

- It is not merely a summary of Scripture

4. The responsibility of theology

- Theology is answerable to God and must be done with prayerful reverence

- Theology is best done in service to God and his people

5. Choosing the question

- Choose a topic that interests you, but look carefully at the question

- Avoid a topic that is a contemporary church controversy where possible

- Consider what others are doing

6. Analysing the question

- What higher level task am I being asked to do, explicitly or implicitly?

- Am I being asked to find a cause or a purpose, or trace a connection, or describe something?

- What is the measure I am being asked to use, explicitly or implicitly?

- Where is my question located in the context of the ongoing theological conversation?

- Are there any extra features of the question that I have to take into account?

7. Beginning to think about it

- Get your brain moving early on

- What different ways of answering the question are there?

- Do some preliminary quick reading to orient yourself to the topic

8. Brainstorming

- Get everything you can think of down on paper in no particular order

- What thinkers might be relevant? Especially look for potential opponents

- What passages of Scripture might be worth investigating?

9. How to read for theology essays (and what to read)

- Read to gain basic information

- Read to gain nuance and subtlety

- Read to develop arguments

- Read to find stimulating conversation partners and ‘surprising friends’

- Read to find out what the opposition says

10. Using the Bible in theology essays

- You have to read Scripture as a whole to do theology biblically

- Orthodoxy helps you to read Scripture theologically

- Avoid prooftexting and word studies

11. How to treat your opponents

- Treat your opponents with respect

- Avoid cheap shots and caricature

12. Some advice on quoting

- Use quotations sparingly

- The author nailed it

- You want to prove your opponent really does say that

- You are expounding a view to learn from it

- Quote SHORT

- Quote faithfully to the author

13. Types of argument for your essay

- Volume knobs, not on/off switches

14. The classic introduction

- Your introduction should set the scene and frame the question

- Your introduction should state your answer to the question

- Your introduction should give an indication of how you are going to answer the question

15. Why presentation matters, and how to make it work for you

- Presentation does matter

- The essential principle: don’t distract your reader

16. How to write well in a theology essay

- Be a reader of great writing

- Don’t be afraid of metaphors

- Learn the simple rules of English punctuation

- Be clear, and avoid vague words

17. The art of signposting

- Use headings

- Use summative sentences

- Use questions that flow

18. Bringing home the bacon

- Your conclusion should add nothing new

- Make sure you have fulfilled any promises you have made

- If you do have some space, consider the implications of your essay for other areas of theology

19. What to do with it now

- Don’t be shy about thinking of ways in which your essay could have a second life

20. A footnote about footnotes

- Use footnote commentary sparingly

- Don’t hide extra words in your footnotes

- Take care that the footnote relates clearly to the text

- Use footnotes to protect yourself by showing that you have read widely

Related: 10 Issues I Frequently Mark When Grading Theology Papers

Reader Interactions

September 19, 2012 at 9:47 pm

…but there’s more to the book than the summaries! :-)

September 20, 2012 at 1:26 pm

This is a great article. Thanks!

Do you have any thesis ideas in the area of philosophy or apologetics with a theological tone?

[…] How to write a Theology Essay Just in case my students begin to think I’m for dumbing down. […]

[…] How to Write a Theology Essay | Andy Naselli […]

- Featured Essay The Love of God An essay by Sam Storms Read Now

- Faithfulness of God

- Saving Grace

- Adoption by God

Most Popular

- Gender Identity

- Trusting God

- The Holiness of God

- See All Essays

- Conference Media

- Featured Essay Resurrection of Jesus An essay by Benjamin Shaw Read Now

- Death of Christ

- Resurrection of Jesus

- Church and State

- Sovereignty of God

- Faith and Works

- The Carson Center

- The Keller Center

- New City Catechism

- Publications

- Read the Bible

U.S. Edition

- Arts & Culture

- Bible & Theology

- Christian Living

- Current Events

- Faith & Work

- As In Heaven

- Gospelbound

- Post-Christianity?

- TGC Podcast

- You're Not Crazy

- Churches Planting Churches

- Help Me Teach The Bible

- Word Of The Week

- Upcoming Events

- Past Conference Media

- Foundation Documents

- Church Directory

- Global Resourcing

- Donate to TGC

To All The World

The world is a confusing place right now. We believe that faithful proclamation of the gospel is what our hostile and disoriented world needs. Do you believe that too? Help TGC bring biblical wisdom to the confusing issues across the world by making a gift to our international work.

Introduction to the Parables

Other essays.

The parables of Jesus have captivated readers for nearly 2,000 years. Characters like the prodigal son, good Samaritan, or Pharisee and tax collector have become well-known even outside the church. Overfamiliarity, however, can breed misunderstanding. It is often hard to re-create the trauma that some of Jesus’s stories would have caused his original audiences. At times, they seem to conceal truth at least as much as they reveal it (Mark 4:11–12). Parables tended to polarize crowds, drawing some people closer to Jesus while driving others away.

Only about half of the stories in the New Testament Gospels typically termed “parables” have that label attached to them in the text. We have come to recognize them more by their form than by any single word that introduces them. The Greek word parabolē, like the Hebrew mãshãl that it translates, was used for a wide variety of forms of figurative speech. A concise definition of a parable is that it is a short, metaphorical narrative. With or without an explicit comparison, it highlights aspects of the kingdom of God. It presents a series of events involving a small number of characters (people, animals, plants, even inanimate objects), most of which seemed realistic in Jesus’s world. At least one element in most parables, however, pushes the boundaries of plausibility. Along with their contexts in the Gospels, this quality reveals that they are fictional works designed to disclose spiritual truths.

History of Interpretation

The history of the interpretation of Jesus’s parables has been checkered. Critical scholarship has regularly found the stories to be as authentic as anything in the Gospels but has attributed their concluding words of explanation to the early Christian tradition or the Gospel writers themselves. A good parable, like a good joke, needs no interpretation; Jesus as master storyteller would not have explained his tales. The problem with this perspective is that we have hundreds of parables of the early rabbis from Jesus’s time onward, who almost always gave clear interpretations.

For much of church history, the dominant form of interpreting the parables swung the pendulum to the opposite extreme. Commentators viewed them as detailed allegories in which almost every element corresponded to some spiritual counterpart. In 1899, Adolf Jülicher published a massive two-volume German work, Die Gleichnisreden Jesu, on the history of interpretation of each parable. He demonstrated not only the frequency of allegorizing but also the number of contradictory allegorical interpretations of a given passage that had sprung up. He insisted that parables make only one main point and should not be treated allegorically at all.

Most subsequent scholarship has been a reaction to Jülicher: some accepted his views entirely, most modified them a little, and a few have suggested more significant alternatives. To accept him entirely, one had to deny that Jesus could have given the point-by-point explanations of the parables of the sower (Mark 4:14–20) and of the wheat and weeds (Matt 13:36–43). The wicked tenants (Mark 12:1–12) had probably been embellished as well, because it seemed transparently to teach about the coming crucifixion of God’s Son after God had repeatedly sent prophets to try to turn Israel from its evil ways—a clear allegory. Most other parables, nevertheless, could be seen as inculcating a single point: the persistent prayer commended by the parable of the widow and the judge (Luke 18:1–8), the judgment coming on those who resemble the unforgiving servant (Matt 18:23–35), or the inevitability of harvest reflected in the seed growing secretly (Mark 4:26–29).

On closer inspection, however, most of the parables appear more complex. Consider again the prodigal son in Luke 15:11–32. Those who have sought one point from this story throughout church history have offered three quite different clusters of topics. Some have focused on the possibility of repentance no matter how far one has strayed from God; others, on not begrudging God’s generosity to the wayward; and still others, on the amazing grace, love, and forgiveness of the heavenly Father. Must we choose only one of these as Jesus’s sole point, as Jülicher did, and decide on the third option? Interestingly, each of these themes emerges from reading the story from the perspectives of each of its three main characters—the prodigal, the older brother, and the father, respectively. Parables appear to teach one main lesson per main character.

Three-Pointed Parables

Approximately two-thirds of Jesus’s parables have a structure that resembles the story of the prodigal. A master or authority figure illustrates some dimension of God’s reign in the world. This figure could be a king, father, landowner, farmer, slave-master, shepherd, banquet-giver, and so on. A set of subordinates then relates to the authority figure in contrasting ways—servants, sons, tenants, seed, slaves, sheep, guests, etc. Often, but not always, there is a surprise as to which of the subordinates turns out to be the good one to be imitated. When one recognizes that multiple individuals can function as either the good or bad characters, one realizes how pervasive this structure is among Jesus’s parables.

For example, in the parable of the ten bridesmaids (Matt 25:1–13), the bridegroom is the master figure who interacts with both the wise and foolish young women. From his behavior, we learn that God may delay the arrival of the end of this age. Like the wise women, therefore, his followers will be prepared for “the long haul” if necessary. The delay is not forever, though, as the foolish women learn, and when that time comes, people’s destinies are irreversible. Identifying the wise women as followers who are prepared should surprise no one, though the bridegroom’s claim not to know the foolish bridesmaids (25:12) does not fit a normal wedding scenario and points to a second or symbolic level of meaning in the passage.

In the parable of the rich man and Lazarus (Luke 16:19–31), Abraham appears as God’s spokesman. This time the contrasting subordinates do cause surprise. Most in Jesus’s world would have assumed the beggar was poor as a punishment for sin, while the rich man was rich as a reward for his piety; instead, it turns out to be the reverse. The rich man’s concern for his still-living family members’ need for repentance (16:30) suggests that he knows he had never truly repented before God. That this story has the identical structure as other three-pronged stories of Jesus further ensures that it is indeed a fictional parable, not an account of real people, as has sometimes been postulated.

Sometimes the good or bad subordinates can be subdivided. Just like a good joke often begins with two or three similar individuals, then setting up a contrast with the last one (“A pastor, a priest, and a rabbi all went into a bar . . .”), so too in Jesus’s parables. The sower sows seed in four different kinds of soil, but only the last one produces the crop for which the farmer planted it. The seeds that grow briefly but wither or are choked out and die are thus not less mature followers but no true disciples at all, just like the seed that fell on the path and was eaten by birds. The contrast does not occur until one comes to the final seed, sown in the good soil. The surprise is the astonishing size of harvest for its day that it produces. The “law of end-stress” determines where the emphasis should be placed: on the good seed. The sower is a “comic” parable in the literary sense of the term—a story with a happy ending.

Jesus’s parables can also be tragic, though, with unhappy endings for characters who could have done better. The great dinner in Luke 14:16–24 has a banquet-giver as the authority figure and groups of contrasting subordinates: the originally invited guests who alike made up flimsy excuses at the last minute for not attending, and the replacement guests who came from the “riff-raff” of society. No one would have expected that reversal, and the climax of the parable is the final exclusion of the original invitees.

In another setting, Jesus reuses the main plot of the great dinner parable but expands it. The wedding banquet (Matt 22:1–14) employs a king as the master figure. Again, there are originally invited guests who refuse to come, followed by replacements, but here the latter are much more briefly described. Instead, Jesus adds a segment on a man without a wedding garment who tries to crash the party (22:10–13). The negative example in this parable is thus divided into two groups—those who overtly reject God’s kingdom offer, and those who act like they are accepting it but refuse to come on God’s terms. Both exclude themselves.

Not all three-pronged parables create a triangular diagram, with a master at the top and contrasting subordinates below. Two of Jesus’s parables can be diagrammed with a straight vertical line—a master, a subordinate under him, and one or more subordinates under the first one. The unjust steward (Luke 16:1–9) presents a master, his steward under him, and several debtors under the steward. The master commends the steward’s shrewdness, not his injustice (v. 8a), the steward , sadly, exemplifies greater shrewdness than many believers do (v. 8b), and the debtors help the steward out after he is fired (16:9)—the three points from the three characters are thus expressed sequentially after the story itself (16:1–7).

In the unforgiving servant (Matt 18:23–35), we have three successive scenes: first, the king displays amazing grace and forgiveness toward his servant (18:23–27); second, the lowest-level servant experiences the absurdity of not receiving grace when the servant over him had received so much (18:28–31); and, finally, the unforgiving servant experiences the full anger and judgment of his master (18:32–34),

In one case, the Good Samaritan (Luke 10:29–37), the line connecting the three main characters of the story seems to be horizontal. There is no one person in a position of power who interacts with the other two. The “unifying” character is someone in a position of powerlessness—the man robbed and left for dead by the side of the road. Shockingly, the priest and the Levite together form the bad example by not stopping to help, while the Samaritan, just as amazingly, becomes the hero when he helps. There is a good model to imitate (10:37), but the story also teaches how religious duty cannot excuse lovelessness and how even an enemy can become one’s neighbor.

Two- and One-Pointed Parables

In about a sixth of Jesus’s parables, there are only two main characters or elements. Sometimes there is a master and subordinate, without a contrast. Other times, there are good and bad examples, without a master figure. The unjust judge exemplifies the first structure. While it is true from Luke 18:1 that Jesus taught about not losing heart in prayer (from the actions of the widow), verses 6–8 teach us what we should learn from the judge. If even an evil authority can be badgered and frightened into administering justice, how much more will God dispense it to those who ask for it? This “how much more” logic, also known as “from the lesser to the greater,” characterizes a number of Jesus’s parables. Too often, commentators have stumbled over the features of the authorities who do not display God’s attributes, especially when they seem overly harsh, without recalling that the dynamic of a parable is not that its characters match their spiritual counterparts in every respect, but merely in certain key aspects.

The very next parable in Luke, the Pharisee and the tax collector (18:9–14), illustrates the category of a short story with contrasting figures but no overt master. Jesus himself, after completing the story in verses 9–13, renders the verdict on behalf of God, that the tax collector went home “justified” rather than the Pharisee, and then derives the two points from the passage—those who exalt themselves shall be humbled, and those who humble themselves shall be exalted (18:14).

In the remaining one-sixth of the parables, then, it seems that Jülicher was correct in affirming only a single point. Pairs of parables like the mustard seed and the leaven (Matt 13:31–33), the tower builder and the king going to war (Luke 14:28–32), and the treasure hidden a field and the pearl of great price (Matt 13:44–46) each have one main character and teach one central lesson. From them, we learn about the surprisingly large growth of the kingdom from tiny beginnings, about counting the cost of discipleship, and about giving up whatever is necessary to be a part of the kingdom, respectively.

The Power of Narrative

It is important to remember that all Jesus’s parables are couched in a narrative rather than didactic form. The power of good fiction is that it grabs one’s attention, sucks one into the plot, and makes one think it is about other people until it is too late. By the time one recognizes a parable’s metaphorical or even, in a limited sense, allegorical form, one has already identified with one or more of the characters and is caught in the trap. The one Old Testament narrative virtually identical in form to those Jesus told is Nathan’s parable of the ewe lamb (2Sam 12:1–10). In a potentially life-and-death move for the prophet, Nathan confronts King David over his adultery with, or rape of, Bathsheba and his murder of Uriah (by sending him to the front lines in battle to be killed). Uriah is like the poor man; Bathsheba, like the ewe-lamb. The rich man obviously represents David, and once David is hooked, he cannot deny that his behavior was as unjust as that of the rich man in the story, whom he has just condemned (12:5–6). The climax of the account comes in verse 7 when Nathan points the finger at David and declares, “You are the man!” David can no longer ignore his sins; fortunately, he repents (12:13; cf. Ps 51).

When Jesus’s parables have lost their shock value in today’s world, they need to be contemporized in order. The Jew robbed and left for dead may need to become a white evangelical man who is helped by a black Muslim woman after the senior pastor and worship leader from the local Reformed church pass him by! Whenever we face a hostile audience, the indirect rhetoric of compelling stories may help at least some people hear God’s Word more favorably.

Further Reading

- Bailey, Kenneth E. Poet and Peasant and Through Peasant Eyes . Grand Rapids:

- Eerdmans, 1983.

- Blomberg, Craig L. Interpreting the Parable . 2 nd ed. Downers Grove: IVP, 2012.

- Blomberg, Craig L. Preaching the Parables . Grand Rapids: Baker, 2004.

- Hultgren, Arland J. The Parables of Jesus . Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2000.

- Jeremias, Joachim. The Parables of Jesus . 3 rd ed. Philadelphia: Westminster, 1972.

- Lee-Barnewall, Michelle. Surprised by the Parables . Bellingham, WA: Lexham, 2020.

- McArthur, Harvey K. and Robert M. Johnston. They Also Taught in Parables . Grand Rapids:

- Zondervan, 1990.

- Snodgrass, Klyne R. Stories with Intent . Rev. ed . Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2018.

This essay is part of the The Gospel Coalition Bible Commentary , edited by Phil Thompson. This essay is freely available under Creative Commons License with Attribution-ShareAlike, allowing users to share it in other mediums/formats and adapt/translate the content as long as an attribution link, indication of changes, and the same Creative Commons License applies to that material. If you are interested in translating our content or are interested in joining our community of translators, please reach out to us .

Exegetical Papers: 1. Choose a Passage & Create a Thesis Statement

- Introduction & Overview

- 2. Historical, Cultural, and Literary Background

- 3. Perform Exegesis of Each Verse

- 4. Offer an Overall Interpretation

- 5. Provide an Application of the Passage

- 6. Finding Books

- 7. Finding Articles

- Turabian Citation Style

- ATLA Search & Video Tutorials

- Formatting Theses and Dissertations in Word 2010

- Quick Links & Databases

- Web Resources

- Online Reference Sources

- Scholarly vs. Non-scholarly Materials

- Avoid Plagiarism

What is your favorite passage in Luke's Gospel?

Jeremiah by Holly Hayes is licensed under a Creative Commons License .

Luke 4:16-21

- Online Concordance

- Online Bible Concordance Site: Biblegateway.com

WWW Button by Stuart Miles is licensed under a Standard License .

Concordances

A Bible concordance is a verbal index to the Bible. A simple form lists Biblical words alphabetically, with indications to enable the inquirer to find the passages of the Bible where the words occur.

Bible Concordances

Commentaries

I n-depth commentaries that treat a Book of the Bible chapter by chapter, are ideal for research. The only problem: there are so many commentaries! Here are some excellent ones.

- More Good Commentaries

These commentaries are in the RWWL library circulating collections.

- Abingdon New Testament Commentaries

- Calvin's Commentary

- Feminist Companion to the Bible

- Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching

- New Te stament Commentary

- The New International Commentary on the New Testament

- The New International Commentary on the Old Testament

What's on this page?

- Choosing a Passage

- Creating a Thesis Statement

- Definition of Concordance

One Volume Commentaries

- Bible Concordances - Print

- Recommended Commentaries

- Gospel Parallels

Choose a Passage for Your Exegesis Paper

If your professor has assigned you a specific passage for your paper, you can skip the rest of this page. Otherwise, you need to choose a passage:

- From an appropriate place in an acceptable version of the Bible

- Of reasonable size

- With identifiable boundaries

Your passage would naturally come from the section of the Bible that your class covers. This guide will assume that your class includes the Gospel of Luke and you have decided to choose a passage from there. You can choose a passage you like, or that features a concept in which you are interested.

Suppose you are interested in studying the story of Jesus' Transfiguration. That is in Luke 9:28-36. So you could write your paper on that passage. Alternatively, you could write on a passage that contains a theme you want to study. Suppose you want to learn about Jesus' attitudes towards money, but you do not know where in Luke's Gospel to look for a passage about money. You can solve this by using a concordance.

A concordance is a tool that lets you look up a word, and see that word in its context in every place it occurs in the Bible. Since English versions of the Bible differ sometimes in how they translate words, you need to pick a concordance that matches your Bible version. (This assumes you are not working directly from Hebrew or Greek, which have their own concordances.) So, if you use the New Revised Standard Version , you could use Concise Concordance to the New Revised Standard Version (Call Number BS425 C655 1993 ).

Next, you need to determine if the passage is of reasonable size. Suppose you have to write a paper that is ten to twelve pages long. That would be about the right size for a passage that is around eight to fifteen verses long, depending upon the genre of the passage. An argument from Romans would probably take more space to interpret than a story in 1 Samuel, though this may not always be true. If you choose a passage that is too short, your paper will probably be too short, e.g., writing on John 3:16 would be a fairly short paper. On the other hand, Luke 1:1-80 is far too long. You could spend thirty pages on that and not be done. It depends in part upon the complexity of the passage. For this LibGuide, let's choose a simple narrative passage: Luke 1:26-38, the announcement to Mary of the coming birth to her of Jesus while she is a virgin.

In order to decide the number of verses to choose, you need to validate that you are doing a complete passage, not starting or stopping in the middle of a narrative or argument. In the case of Luke 1:26-38, you can tell that v. 26 is an appropriate beginning for this short narrative (called a pericope in biblical studies) because v. 26 provides a statement that indicates a new event is happening at a point later in time than 1:5-25. In Luke 1:26 it is stated that the angel Gabriel, six months after promising Zechariah that John would be born, was sent to Nazareth in Galilee by God. At the beginning of Luke 1:39, we again read about a transition to a new location, as Mary leaves to go visit her cousin Elizabeth. That makes Luke 1:38 the end of the announcement to Mary by Gabriel. This is fifteen verses, which is about the most you should consider doing for a typical exegesis paper. Shifts in time ("and it came to pass"), shifts in location ("went up to Jerusalem"), and shifts in topic ("There is therefore no condemnation to those who are in the Messiah Jesus") all indicate the beginning of a new narrative pericope or a new topic. Look for those as you seek the beginning and end of your passage.

You could verify the boundaries of your passage by finding a Bible that divides the text into paragraphs and seeing how it divides this passage. You should plan, however, to describe why you have chosen a particular set of verses and not more or less. The paragraphs are only the view of one modern editorial team, not part of the Bible itself. The chapters and verses in modern Bibles were put in many centuries after all the books of the Bible were written.

Go to the next tab above to learn how to examine the Historical, Cultural, and Literary Background of your passage.

Create a Thesis Statement

"Defining the Thesis Statement

What is a thesis statement?

Every paper you write should have a main point, a main idea, or central message. The argument(s) you make in your paper should reflect this main idea. The sentence that captures your position on this main idea is what we call a thesis statement.

How long does it need to be?

A thesis statement focuses your ideas into one or two sentences. It should present the topic of your paper and also make a comment about your position in relation to the topic. Your thesis statement should tell your reader what the paper is about and also help guide your writing and keep your argument focused.

Questions to Ask When Formulating Your Thesis

Where is your thesis statement?

You should provide a thesis early in your essay -- in the introduction, or in longer essays in the second paragraph -- in order to establish your position and give your reader a sense of direction.

Tip : In order to write a successful thesis statement:

- Avoid burying a great thesis statement in the middle of a paragraph or late in the paper.

- Be as clear and as specific as possible; avoid vague words.

- Indicate the point of your paper but avoid sentence structures like, “The point of my paper is…”

Is your thesis statement specific?

Your thesis statement should be as clear and specific as possible. Normally you will continue to refine your thesis as you revise your argument(s), so your thesis will evolve and gain definition as you obtain a better sense of where your argument is taking you.

Tip : Check your thesis:

- Are there two large statements connected loosely by a coordinating conjunction (i.e. "and," "but," "or," "for," "nor," "so," "yet")?

- Would a subordinating conjunction help (i.e. "through," "although," "because," "since") to signal a relationship between the two sentences?

- Or do the two statements imply a fuzzy unfocused thesis?

- If so, settle on one single focus and then proceed with further development.

Is your thesis statement too general?

Your thesis should be limited to what can be accomplished in the specified number of pages. Shape your topic so that you can get straight to the "meat" of it. Being specific in your paper will be much more successful than writing about general things that do not say much. Don't settle for three pages of just skimming the surface.

The opposite of a focused, narrow, crisp thesis is a broad, sprawling, superficial thesis. Compare this original thesis (too general) with three possible revisions (more focused, each presenting a different approach to the same topic):

- There are serious objections to today's horror movies.

- Because modern cinematic techniques have allowed filmmakers to get more graphic, horror flicks have desensitized young American viewers to violence.

- The pornographic violence in "bloodbath" slasher movies degrades both men and women.

- Today's slasher movies fail to deliver the emotional catharsis that 1930s horror films did.

Is your thesis statement clear?

Your thesis statement is no exception to your writing: it needs to be as clear as possible. By being as clear as possible in your thesis statement, you will make sure that your reader understands exactly what you mean.

Tip : In order to be as clear as possible in your writing:

- Unless you're writing a technical report, avoid technical language. Always avoid jargon, unless you are confident your audience will be familiar with it.

- Avoid vague words such as "interesting,” "negative," "exciting,” "unusual," and "difficult."

- Avoid abstract words such as "society," “values,” or “culture.”

These words tell the reader next to nothing if you do not carefully explain what you mean by them. Never assume that the meaning of a sentence is obvious. Check to see if you need to define your terms (”socialism," "conventional," "commercialism," "society"), and then decide on the most appropriate place to do so. Do not assume, for example, that you have the same understanding of what “society” means as your reader. To avoid misunderstandings, be as specific as possible.

Compare the original thesis (not specific and clear enough) with the revised version (much more specific and clear):

- Original thesis : Although the timber wolf is a timid and gentle animal, it is being systematically exterminated. [if it's so timid and gentle -- why is it being exterminated?]

- Revised thesis : Although the timber wolf is actually a timid and gentle animal, it is being systematically exterminated because people wrongfully believe it to be a fierce and cold-blooded killer.

Does your thesis include a comment about your position on the issue at hand?

The thesis statement should do more than merely announce the topic; it must reveal what position you will take in relation to that topic, how you plan to analyze/evaluate the subject or the issue. In short, instead of merely stating a general fact or resorting to a simplistic pro/con statement, you must decide what it is you have to say.

- Original thesis : In this paper, I will discuss the relationship between fairy tales and early childhood.

- Revised thesis : Not just empty stories for kids, fairy tales shed light on the psychology of young children.

- Original thesis : We must save the whales.

- Revised thesis : Because our planet's health may depend upon biological diversity, we should save the whales.

- Original thesis : Socialism is the best form of government for Kenya.

- Revised thesis : If the government takes over industry in Kenya, the industry will become more efficient.

- Original thesis : Hoover's administration was rocked by scandal.

- Revised thesis : The many scandals of Hoover's administration revealed basic problems with the Republican Party's nominating process.

Do not expect to come up with a fully formulated thesis statement before you have finished writing the paper. The thesis will inevitably change as you revise and develop your ideas—and that is ok! Start with a tentative thesis and revise as your paper develops.

Is your thesis statement original?

Avoid, avoid, avoid generic arguments and formula statements. They work well to get a rough draft started, but will easily bore a reader. Keep revising until the thesis reflects your real ideas.

Tip : The point you make in the paper should matter:

- Be prepared to answer “So what?” about your thesis statement.

- Be prepared to explain why the point you are making is worthy of a paper. Why should the reader read it?

Compare the following:

- There are advantages and disadvantages to using statistics. (a fill-in-the-blank formula)

- Careful manipulation of data allows a researcher to use statistics to support any claim she desires.

- In order to ensure accurate reporting, journalists must understand the real significance of the statistics they report.

- Because advertisers consciously and unconsciously manipulate data, every consumer should learn how to evaluate statistical claims.

Avoid formula and generic words. Search for concrete subjects and active verbs, revising as many "to be" verbs as possible. A few suggestions below show how specific word choice sharpens and clarifies your meaning.

- Original : “Society is...” [who is this "society" and what exactly is it doing?]