Chapter 11. Interviewing

Introduction.

Interviewing people is at the heart of qualitative research. It is not merely a way to collect data but an intrinsically rewarding activity—an interaction between two people that holds the potential for greater understanding and interpersonal development. Unlike many of our daily interactions with others that are fairly shallow and mundane, sitting down with a person for an hour or two and really listening to what they have to say is a profound and deep enterprise, one that can provide not only “data” for you, the interviewer, but also self-understanding and a feeling of being heard for the interviewee. I always approach interviewing with a deep appreciation for the opportunity it gives me to understand how other people experience the world. That said, there is not one kind of interview but many, and some of these are shallower than others. This chapter will provide you with an overview of interview techniques but with a special focus on the in-depth semistructured interview guide approach, which is the approach most widely used in social science research.

An interview can be variously defined as “a conversation with a purpose” ( Lune and Berg 2018 ) and an attempt to understand the world from the point of view of the person being interviewed: “to unfold the meaning of peoples’ experiences, to uncover their lived world prior to scientific explanations” ( Kvale 2007 ). It is a form of active listening in which the interviewer steers the conversation to subjects and topics of interest to their research but also manages to leave enough space for those interviewed to say surprising things. Achieving that balance is a tricky thing, which is why most practitioners believe interviewing is both an art and a science. In my experience as a teacher, there are some students who are “natural” interviewers (often they are introverts), but anyone can learn to conduct interviews, and everyone, even those of us who have been doing this for years, can improve their interviewing skills. This might be a good time to highlight the fact that the interview is a product between interviewer and interviewee and that this product is only as good as the rapport established between the two participants. Active listening is the key to establishing this necessary rapport.

Patton ( 2002 ) makes the argument that we use interviews because there are certain things that are not observable. In particular, “we cannot observe feelings, thoughts, and intentions. We cannot observe behaviors that took place at some previous point in time. We cannot observe situations that preclude the presence of an observer. We cannot observe how people have organized the world and the meanings they attach to what goes on in the world. We have to ask people questions about those things” ( 341 ).

Types of Interviews

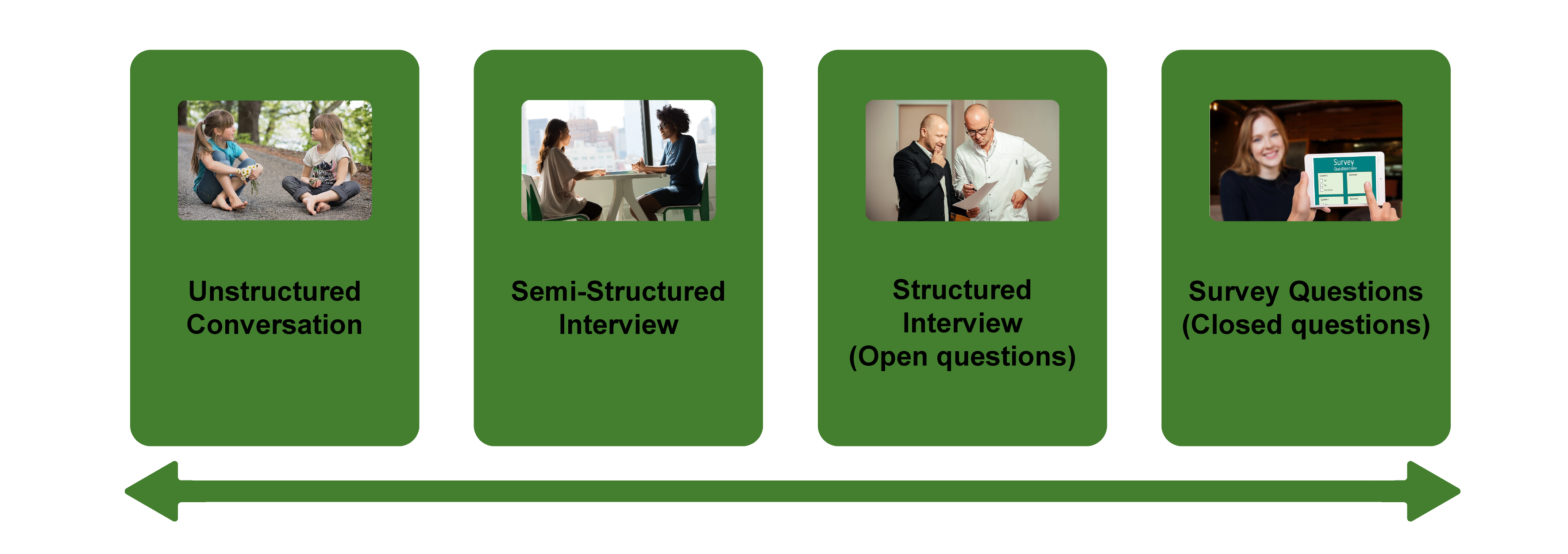

There are several distinct types of interviews. Imagine a continuum (figure 11.1). On one side are unstructured conversations—the kind you have with your friends. No one is in control of those conversations, and what you talk about is often random—whatever pops into your head. There is no secret, underlying purpose to your talking—if anything, the purpose is to talk to and engage with each other, and the words you use and the things you talk about are a little beside the point. An unstructured interview is a little like this informal conversation, except that one of the parties to the conversation (you, the researcher) does have an underlying purpose, and that is to understand the other person. You are not friends speaking for no purpose, but it might feel just as unstructured to the “interviewee” in this scenario. That is one side of the continuum. On the other side are fully structured and standardized survey-type questions asked face-to-face. Here it is very clear who is asking the questions and who is answering them. This doesn’t feel like a conversation at all! A lot of people new to interviewing have this ( erroneously !) in mind when they think about interviews as data collection. Somewhere in the middle of these two extreme cases is the “ semistructured” interview , in which the researcher uses an “interview guide” to gently move the conversation to certain topics and issues. This is the primary form of interviewing for qualitative social scientists and will be what I refer to as interviewing for the rest of this chapter, unless otherwise specified.

Informal (unstructured conversations). This is the most “open-ended” approach to interviewing. It is particularly useful in conjunction with observational methods (see chapters 13 and 14). There are no predetermined questions. Each interview will be different. Imagine you are researching the Oregon Country Fair, an annual event in Veneta, Oregon, that includes live music, artisan craft booths, face painting, and a lot of people walking through forest paths. It’s unlikely that you will be able to get a person to sit down with you and talk intensely about a set of questions for an hour and a half. But you might be able to sidle up to several people and engage with them about their experiences at the fair. You might have a general interest in what attracts people to these events, so you could start a conversation by asking strangers why they are here or why they come back every year. That’s it. Then you have a conversation that may lead you anywhere. Maybe one person tells a long story about how their parents brought them here when they were a kid. A second person talks about how this is better than Burning Man. A third person shares their favorite traveling band. And yet another enthuses about the public library in the woods. During your conversations, you also talk about a lot of other things—the weather, the utilikilts for sale, the fact that a favorite food booth has disappeared. It’s all good. You may not be able to record these conversations. Instead, you might jot down notes on the spot and then, when you have the time, write down as much as you can remember about the conversations in long fieldnotes. Later, you will have to sit down with these fieldnotes and try to make sense of all the information (see chapters 18 and 19).

Interview guide ( semistructured interview ). This is the primary type employed by social science qualitative researchers. The researcher creates an “interview guide” in advance, which she uses in every interview. In theory, every person interviewed is asked the same questions. In practice, every person interviewed is asked mostly the same topics but not always the same questions, as the whole point of a “guide” is that it guides the direction of the conversation but does not command it. The guide is typically between five and ten questions or question areas, sometimes with suggested follow-ups or prompts . For example, one question might be “What was it like growing up in Eastern Oregon?” with prompts such as “Did you live in a rural area? What kind of high school did you attend?” to help the conversation develop. These interviews generally take place in a quiet place (not a busy walkway during a festival) and are recorded. The recordings are transcribed, and those transcriptions then become the “data” that is analyzed (see chapters 18 and 19). The conventional length of one of these types of interviews is between one hour and two hours, optimally ninety minutes. Less than one hour doesn’t allow for much development of questions and thoughts, and two hours (or more) is a lot of time to ask someone to sit still and answer questions. If you have a lot of ground to cover, and the person is willing, I highly recommend two separate interview sessions, with the second session being slightly shorter than the first (e.g., ninety minutes the first day, sixty minutes the second). There are lots of good reasons for this, but the most compelling one is that this allows you to listen to the first day’s recording and catch anything interesting you might have missed in the moment and so develop follow-up questions that can probe further. This also allows the person being interviewed to have some time to think about the issues raised in the interview and go a little deeper with their answers.

Standardized questionnaire with open responses ( structured interview ). This is the type of interview a lot of people have in mind when they hear “interview”: a researcher comes to your door with a clipboard and proceeds to ask you a series of questions. These questions are all the same whoever answers the door; they are “standardized.” Both the wording and the exact order are important, as people’s responses may vary depending on how and when a question is asked. These are qualitative only in that the questions allow for “open-ended responses”: people can say whatever they want rather than select from a predetermined menu of responses. For example, a survey I collaborated on included this open-ended response question: “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?” Some of the answers were simply one word long (e.g., “debt”), and others were long statements with stories and personal anecdotes. It is possible to be surprised by the responses. Although it’s a stretch to call this kind of questioning a conversation, it does allow the person answering the question some degree of freedom in how they answer.

Survey questionnaire with closed responses (not an interview!). Standardized survey questions with specific answer options (e.g., closed responses) are not really interviews at all, and they do not generate qualitative data. For example, if we included five options for the question “How does class affect one’s career success in sociology?”—(1) debt, (2) social networks, (3) alienation, (4) family doesn’t understand, (5) type of grad program—we leave no room for surprises at all. Instead, we would most likely look at patterns around these responses, thinking quantitatively rather than qualitatively (e.g., using regression analysis techniques, we might find that working-class sociologists were twice as likely to bring up alienation). It can sometimes be confusing for new students because the very same survey can include both closed-ended and open-ended questions. The key is to think about how these will be analyzed and to what level surprises are possible. If your plan is to turn all responses into a number and make predictions about correlations and relationships, you are no longer conducting qualitative research. This is true even if you are conducting this survey face-to-face with a real live human. Closed-response questions are not conversations of any kind, purposeful or not.

In summary, the semistructured interview guide approach is the predominant form of interviewing for social science qualitative researchers because it allows a high degree of freedom of responses from those interviewed (thus allowing for novel discoveries) while still maintaining some connection to a research question area or topic of interest. The rest of the chapter assumes the employment of this form.

Creating an Interview Guide

Your interview guide is the instrument used to bridge your research question(s) and what the people you are interviewing want to tell you. Unlike a standardized questionnaire, the questions actually asked do not need to be exactly what you have written down in your guide. The guide is meant to create space for those you are interviewing to talk about the phenomenon of interest, but sometimes you are not even sure what that phenomenon is until you start asking questions. A priority in creating an interview guide is to ensure it offers space. One of the worst mistakes is to create questions that are so specific that the person answering them will not stray. Relatedly, questions that sound “academic” will shut down a lot of respondents. A good interview guide invites respondents to talk about what is important to them, not feel like they are performing or being evaluated by you.

Good interview questions should not sound like your “research question” at all. For example, let’s say your research question is “How do patriarchal assumptions influence men’s understanding of climate change and responses to climate change?” It would be worse than unhelpful to ask a respondent, “How do your assumptions about the role of men affect your understanding of climate change?” You need to unpack this into manageable nuggets that pull your respondent into the area of interest without leading him anywhere. You could start by asking him what he thinks about climate change in general. Or, even better, whether he has any concerns about heatwaves or increased tornadoes or polar icecaps melting. Once he starts talking about that, you can ask follow-up questions that bring in issues around gendered roles, perhaps asking if he is married (to a woman) and whether his wife shares his thoughts and, if not, how they negotiate that difference. The fact is, you won’t really know the right questions to ask until he starts talking.

There are several distinct types of questions that can be used in your interview guide, either as main questions or as follow-up probes. If you remember that the point is to leave space for the respondent, you will craft a much more effective interview guide! You will also want to think about the place of time in both the questions themselves (past, present, future orientations) and the sequencing of the questions.

Researcher Note

Suggestion : As you read the next three sections (types of questions, temporality, question sequence), have in mind a particular research question, and try to draft questions and sequence them in a way that opens space for a discussion that helps you answer your research question.

Type of Questions

Experience and behavior questions ask about what a respondent does regularly (their behavior) or has done (their experience). These are relatively easy questions for people to answer because they appear more “factual” and less subjective. This makes them good opening questions. For the study on climate change above, you might ask, “Have you ever experienced an unusual weather event? What happened?” Or “You said you work outside? What is a typical summer workday like for you? How do you protect yourself from the heat?”

Opinion and values questions , in contrast, ask questions that get inside the minds of those you are interviewing. “Do you think climate change is real? Who or what is responsible for it?” are two such questions. Note that you don’t have to literally ask, “What is your opinion of X?” but you can find a way to ask the specific question relevant to the conversation you are having. These questions are a bit trickier to ask because the answers you get may depend in part on how your respondent perceives you and whether they want to please you or not. We’ve talked a fair amount about being reflective. Here is another place where this comes into play. You need to be aware of the effect your presence might have on the answers you are receiving and adjust accordingly. If you are a woman who is perceived as liberal asking a man who identifies as conservative about climate change, there is a lot of subtext that can be going on in the interview. There is no one right way to resolve this, but you must at least be aware of it.

Feeling questions are questions that ask respondents to draw on their emotional responses. It’s pretty common for academic researchers to forget that we have bodies and emotions, but people’s understandings of the world often operate at this affective level, sometimes unconsciously or barely consciously. It is a good idea to include questions that leave space for respondents to remember, imagine, or relive emotional responses to particular phenomena. “What was it like when you heard your cousin’s house burned down in that wildfire?” doesn’t explicitly use any emotion words, but it allows your respondent to remember what was probably a pretty emotional day. And if they respond emotionally neutral, that is pretty interesting data too. Note that asking someone “How do you feel about X” is not always going to evoke an emotional response, as they might simply turn around and respond with “I think that…” It is better to craft a question that actually pushes the respondent into the affective category. This might be a specific follow-up to an experience and behavior question —for example, “You just told me about your daily routine during the summer heat. Do you worry it is going to get worse?” or “Have you ever been afraid it will be too hot to get your work accomplished?”

Knowledge questions ask respondents what they actually know about something factual. We have to be careful when we ask these types of questions so that respondents do not feel like we are evaluating them (which would shut them down), but, for example, it is helpful to know when you are having a conversation about climate change that your respondent does in fact know that unusual weather events have increased and that these have been attributed to climate change! Asking these questions can set the stage for deeper questions and can ensure that the conversation makes the same kind of sense to both participants. For example, a conversation about political polarization can be put back on track once you realize that the respondent doesn’t really have a clear understanding that there are two parties in the US. Instead of asking a series of questions about Republicans and Democrats, you might shift your questions to talk more generally about political disagreements (e.g., “people against abortion”). And sometimes what you do want to know is the level of knowledge about a particular program or event (e.g., “Are you aware you can discharge your student loans through the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program?”).

Sensory questions call on all senses of the respondent to capture deeper responses. These are particularly helpful in sparking memory. “Think back to your childhood in Eastern Oregon. Describe the smells, the sounds…” Or you could use these questions to help a person access the full experience of a setting they customarily inhabit: “When you walk through the doors to your office building, what do you see? Hear? Smell?” As with feeling questions , these questions often supplement experience and behavior questions . They are another way of allowing your respondent to report fully and deeply rather than remain on the surface.

Creative questions employ illustrative examples, suggested scenarios, or simulations to get respondents to think more deeply about an issue, topic, or experience. There are many options here. In The Trouble with Passion , Erin Cech ( 2021 ) provides a scenario in which “Joe” is trying to decide whether to stay at his decent but boring computer job or follow his passion by opening a restaurant. She asks respondents, “What should Joe do?” Their answers illuminate the attraction of “passion” in job selection. In my own work, I have used a news story about an upwardly mobile young man who no longer has time to see his mother and sisters to probe respondents’ feelings about the costs of social mobility. Jessi Streib and Betsy Leondar-Wright have used single-page cartoon “scenes” to elicit evaluations of potential racial discrimination, sexual harassment, and classism. Barbara Sutton ( 2010 ) has employed lists of words (“strong,” “mother,” “victim”) on notecards she fans out and asks her female respondents to select and discuss.

Background/Demographic Questions

You most definitely will want to know more about the person you are interviewing in terms of conventional demographic information, such as age, race, gender identity, occupation, and educational attainment. These are not questions that normally open up inquiry. [1] For this reason, my practice has been to include a separate “demographic questionnaire” sheet that I ask each respondent to fill out at the conclusion of the interview. Only include those aspects that are relevant to your study. For example, if you are not exploring religion or religious affiliation, do not include questions about a person’s religion on the demographic sheet. See the example provided at the end of this chapter.

Temporality

Any type of question can have a past, present, or future orientation. For example, if you are asking a behavior question about workplace routine, you might ask the respondent to talk about past work, present work, and ideal (future) work. Similarly, if you want to understand how people cope with natural disasters, you might ask your respondent how they felt then during the wildfire and now in retrospect and whether and to what extent they have concerns for future wildfire disasters. It’s a relatively simple suggestion—don’t forget to ask about past, present, and future—but it can have a big impact on the quality of the responses you receive.

Question Sequence

Having a list of good questions or good question areas is not enough to make a good interview guide. You will want to pay attention to the order in which you ask your questions. Even though any one respondent can derail this order (perhaps by jumping to answer a question you haven’t yet asked), a good advance plan is always helpful. When thinking about sequence, remember that your goal is to get your respondent to open up to you and to say things that might surprise you. To establish rapport, it is best to start with nonthreatening questions. Asking about the present is often the safest place to begin, followed by the past (they have to know you a little bit to get there), and lastly, the future (talking about hopes and fears requires the most rapport). To allow for surprises, it is best to move from very general questions to more particular questions only later in the interview. This ensures that respondents have the freedom to bring up the topics that are relevant to them rather than feel like they are constrained to answer you narrowly. For example, refrain from asking about particular emotions until these have come up previously—don’t lead with them. Often, your more particular questions will emerge only during the course of the interview, tailored to what is emerging in conversation.

Once you have a set of questions, read through them aloud and imagine you are being asked the same questions. Does the set of questions have a natural flow? Would you be willing to answer the very first question to a total stranger? Does your sequence establish facts and experiences before moving on to opinions and values? Did you include prefatory statements, where necessary; transitions; and other announcements? These can be as simple as “Hey, we talked a lot about your experiences as a barista while in college.… Now I am turning to something completely different: how you managed friendships in college.” That is an abrupt transition, but it has been softened by your acknowledgment of that.

Probes and Flexibility

Once you have the interview guide, you will also want to leave room for probes and follow-up questions. As in the sample probe included here, you can write out the obvious probes and follow-up questions in advance. You might not need them, as your respondent might anticipate them and include full responses to the original question. Or you might need to tailor them to how your respondent answered the question. Some common probes and follow-up questions include asking for more details (When did that happen? Who else was there?), asking for elaboration (Could you say more about that?), asking for clarification (Does that mean what I think it means or something else? I understand what you mean, but someone else reading the transcript might not), and asking for contrast or comparison (How did this experience compare with last year’s event?). “Probing is a skill that comes from knowing what to look for in the interview, listening carefully to what is being said and what is not said, and being sensitive to the feedback needs of the person being interviewed” ( Patton 2002:374 ). It takes work! And energy. I and many other interviewers I know report feeling emotionally and even physically drained after conducting an interview. You are tasked with active listening and rearranging your interview guide as needed on the fly. If you only ask the questions written down in your interview guide with no deviations, you are doing it wrong. [2]

The Final Question

Every interview guide should include a very open-ended final question that allows for the respondent to say whatever it is they have been dying to tell you but you’ve forgotten to ask. About half the time they are tired too and will tell you they have nothing else to say. But incredibly, some of the most honest and complete responses take place here, at the end of a long interview. You have to realize that the person being interviewed is often discovering things about themselves as they talk to you and that this process of discovery can lead to new insights for them. Making space at the end is therefore crucial. Be sure you convey that you actually do want them to tell you more, that the offer of “anything else?” is not read as an empty convention where the polite response is no. Here is where you can pull from that active listening and tailor the final question to the particular person. For example, “I’ve asked you a lot of questions about what it was like to live through that wildfire. I’m wondering if there is anything I’ve forgotten to ask, especially because I haven’t had that experience myself” is a much more inviting final question than “Great. Anything you want to add?” It’s also helpful to convey to the person that you have the time to listen to their full answer, even if the allotted time is at the end. After all, there are no more questions to ask, so the respondent knows exactly how much time is left. Do them the courtesy of listening to them!

Conducting the Interview

Once you have your interview guide, you are on your way to conducting your first interview. I always practice my interview guide with a friend or family member. I do this even when the questions don’t make perfect sense for them, as it still helps me realize which questions make no sense, are poorly worded (too academic), or don’t follow sequentially. I also practice the routine I will use for interviewing, which goes something like this:

- Introduce myself and reintroduce the study

- Provide consent form and ask them to sign and retain/return copy

- Ask if they have any questions about the study before we begin

- Ask if I can begin recording

- Ask questions (from interview guide)

- Turn off the recording device

- Ask if they are willing to fill out my demographic questionnaire

- Collect questionnaire and, without looking at the answers, place in same folder as signed consent form

- Thank them and depart

A note on remote interviewing: Interviews have traditionally been conducted face-to-face in a private or quiet public setting. You don’t want a lot of background noise, as this will make transcriptions difficult. During the recent global pandemic, many interviewers, myself included, learned the benefits of interviewing remotely. Although face-to-face is still preferable for many reasons, Zoom interviewing is not a bad alternative, and it does allow more interviews across great distances. Zoom also includes automatic transcription, which significantly cuts down on the time it normally takes to convert our conversations into “data” to be analyzed. These automatic transcriptions are not perfect, however, and you will still need to listen to the recording and clarify and clean up the transcription. Nor do automatic transcriptions include notations of body language or change of tone, which you may want to include. When interviewing remotely, you will want to collect the consent form before you meet: ask them to read, sign, and return it as an email attachment. I think it is better to ask for the demographic questionnaire after the interview, but because some respondents may never return it then, it is probably best to ask for this at the same time as the consent form, in advance of the interview.

What should you bring to the interview? I would recommend bringing two copies of the consent form (one for you and one for the respondent), a demographic questionnaire, a manila folder in which to place the signed consent form and filled-out demographic questionnaire, a printed copy of your interview guide (I print with three-inch right margins so I can jot down notes on the page next to relevant questions), a pen, a recording device, and water.

After the interview, you will want to secure the signed consent form in a locked filing cabinet (if in print) or a password-protected folder on your computer. Using Excel or a similar program that allows tables/spreadsheets, create an identifying number for your interview that links to the consent form without using the name of your respondent. For example, let’s say that I conduct interviews with US politicians, and the first person I meet with is George W. Bush. I will assign the transcription the number “INT#001” and add it to the signed consent form. [3] The signed consent form goes into a locked filing cabinet, and I never use the name “George W. Bush” again. I take the information from the demographic sheet, open my Excel spreadsheet, and add the relevant information in separate columns for the row INT#001: White, male, Republican. When I interview Bill Clinton as my second interview, I include a second row: INT#002: White, male, Democrat. And so on. The only link to the actual name of the respondent and this information is the fact that the consent form (unavailable to anyone but me) has stamped on it the interview number.

Many students get very nervous before their first interview. Actually, many of us are always nervous before the interview! But do not worry—this is normal, and it does pass. Chances are, you will be pleasantly surprised at how comfortable it begins to feel. These “purposeful conversations” are often a delight for both participants. This is not to say that sometimes things go wrong. I often have my students practice several “bad scenarios” (e.g., a respondent that you cannot get to open up; a respondent who is too talkative and dominates the conversation, steering it away from the topics you are interested in; emotions that completely take over; or shocking disclosures you are ill-prepared to handle), but most of the time, things go quite well. Be prepared for the unexpected, but know that the reason interviews are so popular as a technique of data collection is that they are usually richly rewarding for both participants.

One thing that I stress to my methods students and remind myself about is that interviews are still conversations between people. If there’s something you might feel uncomfortable asking someone about in a “normal” conversation, you will likely also feel a bit of discomfort asking it in an interview. Maybe more importantly, your respondent may feel uncomfortable. Social research—especially about inequality—can be uncomfortable. And it’s easy to slip into an abstract, intellectualized, or removed perspective as an interviewer. This is one reason trying out interview questions is important. Another is that sometimes the question sounds good in your head but doesn’t work as well out loud in practice. I learned this the hard way when a respondent asked me how I would answer the question I had just posed, and I realized that not only did I not really know how I would answer it, but I also wasn’t quite as sure I knew what I was asking as I had thought.

—Elizabeth M. Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology at Saint Joseph’s University, author of Class and Campus Life , and co-author of Geographies of Campus Inequality

How Many Interviews?

Your research design has included a targeted number of interviews and a recruitment plan (see chapter 5). Follow your plan, but remember that “ saturation ” is your goal. You interview as many people as you can until you reach a point at which you are no longer surprised by what they tell you. This means not that no one after your first twenty interviews will have surprising, interesting stories to tell you but rather that the picture you are forming about the phenomenon of interest to you from a research perspective has come into focus, and none of the interviews are substantially refocusing that picture. That is when you should stop collecting interviews. Note that to know when you have reached this, you will need to read your transcripts as you go. More about this in chapters 18 and 19.

Your Final Product: The Ideal Interview Transcript

A good interview transcript will demonstrate a subtly controlled conversation by the skillful interviewer. In general, you want to see replies that are about one paragraph long, not short sentences and not running on for several pages. Although it is sometimes necessary to follow respondents down tangents, it is also often necessary to pull them back to the questions that form the basis of your research study. This is not really a free conversation, although it may feel like that to the person you are interviewing.

Final Tips from an Interview Master

Annette Lareau is arguably one of the masters of the trade. In Listening to People , she provides several guidelines for good interviews and then offers a detailed example of an interview gone wrong and how it could be addressed (please see the “Further Readings” at the end of this chapter). Here is an abbreviated version of her set of guidelines: (1) interview respondents who are experts on the subjects of most interest to you (as a corollary, don’t ask people about things they don’t know); (2) listen carefully and talk as little as possible; (3) keep in mind what you want to know and why you want to know it; (4) be a proactive interviewer (subtly guide the conversation); (5) assure respondents that there aren’t any right or wrong answers; (6) use the respondent’s own words to probe further (this both allows you to accurately identify what you heard and pushes the respondent to explain further); (7) reuse effective probes (don’t reinvent the wheel as you go—if repeating the words back works, do it again and again); (8) focus on learning the subjective meanings that events or experiences have for a respondent; (9) don’t be afraid to ask a question that draws on your own knowledge (unlike trial lawyers who are trained never to ask a question for which they don’t already know the answer, sometimes it’s worth it to ask risky questions based on your hypotheses or just plain hunches); (10) keep thinking while you are listening (so difficult…and important); (11) return to a theme raised by a respondent if you want further information; (12) be mindful of power inequalities (and never ever coerce a respondent to continue the interview if they want out); (13) take control with overly talkative respondents; (14) expect overly succinct responses, and develop strategies for probing further; (15) balance digging deep and moving on; (16) develop a plan to deflect questions (e.g., let them know you are happy to answer any questions at the end of the interview, but you don’t want to take time away from them now); and at the end, (17) check to see whether you have asked all your questions. You don’t always have to ask everyone the same set of questions, but if there is a big area you have forgotten to cover, now is the time to recover ( Lareau 2021:93–103 ).

Sample: Demographic Questionnaire

ASA Taskforce on First-Generation and Working-Class Persons in Sociology – Class Effects on Career Success

Supplementary Demographic Questionnaire

Thank you for your participation in this interview project. We would like to collect a few pieces of key demographic information from you to supplement our analyses. Your answers to these questions will be kept confidential and stored by ID number. All of your responses here are entirely voluntary!

What best captures your race/ethnicity? (please check any/all that apply)

- White (Non Hispanic/Latina/o/x)

- Black or African American

- Hispanic, Latino/a/x of Spanish

- Asian or Asian American

- American Indian or Alaska Native

- Middle Eastern or North African

- Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander

- Other : (Please write in: ________________)

What is your current position?

- Grad Student

- Full Professor

Please check any and all of the following that apply to you:

- I identify as a working-class academic

- I was the first in my family to graduate from college

- I grew up poor

What best reflects your gender?

- Transgender female/Transgender woman

- Transgender male/Transgender man

- Gender queer/ Gender nonconforming

Anything else you would like us to know about you?

Example: Interview Guide

In this example, follow-up prompts are italicized. Note the sequence of questions. That second question often elicits an entire life history , answering several later questions in advance.

Introduction Script/Question

Thank you for participating in our survey of ASA members who identify as first-generation or working-class. As you may have heard, ASA has sponsored a taskforce on first-generation and working-class persons in sociology and we are interested in hearing from those who so identify. Your participation in this interview will help advance our knowledge in this area.

- The first thing we would like to as you is why you have volunteered to be part of this study? What does it mean to you be first-gen or working class? Why were you willing to be interviewed?

- How did you decide to become a sociologist?

- Can you tell me a little bit about where you grew up? ( prompts: what did your parent(s) do for a living? What kind of high school did you attend?)

- Has this identity been salient to your experience? (how? How much?)

- How welcoming was your grad program? Your first academic employer?

- Why did you decide to pursue sociology at the graduate level?

- Did you experience culture shock in college? In graduate school?

- Has your FGWC status shaped how you’ve thought about where you went to school? debt? etc?

- Were you mentored? How did this work (not work)? How might it?

- What did you consider when deciding where to go to grad school? Where to apply for your first position?

- What, to you, is a mark of career success? Have you achieved that success? What has helped or hindered your pursuit of success?

- Do you think sociology, as a field, cares about prestige?

- Let’s talk a little bit about intersectionality. How does being first-gen/working class work alongside other identities that are important to you?

- What do your friends and family think about your career? Have you had any difficulty relating to family members or past friends since becoming highly educated?

- Do you have any debt from college/grad school? Are you concerned about this? Could you explain more about how you paid for college/grad school? (here, include assistance from family, fellowships, scholarships, etc.)

- (You’ve mentioned issues or obstacles you had because of your background.) What could have helped? Or, who or what did? Can you think of fortuitous moments in your career?

- Do you have any regrets about the path you took?

- Is there anything else you would like to add? Anything that the Taskforce should take note of, that we did not ask you about here?

Further Readings

Britten, Nicky. 1995. “Qualitative Interviews in Medical Research.” BMJ: British Medical Journal 31(6999):251–253. A good basic overview of interviewing particularly useful for students of public health and medical research generally.

Corbin, Juliet, and Janice M. Morse. 2003. “The Unstructured Interactive Interview: Issues of Reciprocity and Risks When Dealing with Sensitive Topics.” Qualitative Inquiry 9(3):335–354. Weighs the potential benefits and harms of conducting interviews on topics that may cause emotional distress. Argues that the researcher’s skills and code of ethics should ensure that the interviewing process provides more of a benefit to both participant and researcher than a harm to the former.

Gerson, Kathleen, and Sarah Damaske. 2020. The Science and Art of Interviewing . New York: Oxford University Press. A useful guidebook/textbook for both undergraduates and graduate students, written by sociologists.

Kvale, Steiner. 2007. Doing Interviews . London: SAGE. An easy-to-follow guide to conducting and analyzing interviews by psychologists.

Lamont, Michèle, and Ann Swidler. 2014. “Methodological Pluralism and the Possibilities and Limits of Interviewing.” Qualitative Sociology 37(2):153–171. Written as a response to various debates surrounding the relative value of interview-based studies and ethnographic studies defending the particular strengths of interviewing. This is a must-read article for anyone seriously engaging in qualitative research!

Pugh, Allison J. 2013. “What Good Are Interviews for Thinking about Culture? Demystifying Interpretive Analysis.” American Journal of Cultural Sociology 1(1):42–68. Another defense of interviewing written against those who champion ethnographic methods as superior, particularly in the area of studying culture. A classic.

Rapley, Timothy John. 2001. “The ‘Artfulness’ of Open-Ended Interviewing: Some considerations in analyzing interviews.” Qualitative Research 1(3):303–323. Argues for the importance of “local context” of data production (the relationship built between interviewer and interviewee, for example) in properly analyzing interview data.

Weiss, Robert S. 1995. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies . New York: Simon and Schuster. A classic and well-regarded textbook on interviewing. Because Weiss has extensive experience conducting surveys, he contrasts the qualitative interview with the survey questionnaire well; particularly useful for those trained in the latter.

- I say “normally” because how people understand their various identities can itself be an expansive topic of inquiry. Here, I am merely talking about collecting otherwise unexamined demographic data, similar to how we ask people to check boxes on surveys. ↵

- Again, this applies to “semistructured in-depth interviewing.” When conducting standardized questionnaires, you will want to ask each question exactly as written, without deviations! ↵

- I always include “INT” in the number because I sometimes have other kinds of data with their own numbering: FG#001 would mean the first focus group, for example. I also always include three-digit spaces, as this allows for up to 999 interviews (or, more realistically, allows for me to interview up to one hundred persons without having to reset my numbering system). ↵

A method of data collection in which the researcher asks the participant questions; the answers to these questions are often recorded and transcribed verbatim. There are many different kinds of interviews - see also semistructured interview , structured interview , and unstructured interview .

A document listing key questions and question areas for use during an interview. It is used most often for semi-structured interviews. A good interview guide may have no more than ten primary questions for two hours of interviewing, but these ten questions will be supplemented by probes and relevant follow-ups throughout the interview. Most IRBs require the inclusion of the interview guide in applications for review. See also interview and semi-structured interview .

A data-collection method that relies on casual, conversational, and informal interviewing. Despite its apparent conversational nature, the researcher usually has a set of particular questions or question areas in mind but allows the interview to unfold spontaneously. This is a common data-collection technique among ethnographers. Compare to the semi-structured or in-depth interview .

A form of interview that follows a standard guide of questions asked, although the order of the questions may change to match the particular needs of each individual interview subject, and probing “follow-up” questions are often added during the course of the interview. The semi-structured interview is the primary form of interviewing used by qualitative researchers in the social sciences. It is sometimes referred to as an “in-depth” interview. See also interview and interview guide .

The cluster of data-collection tools and techniques that involve observing interactions between people, the behaviors, and practices of individuals (sometimes in contrast to what they say about how they act and behave), and cultures in context. Observational methods are the key tools employed by ethnographers and Grounded Theory .

Follow-up questions used in a semi-structured interview to elicit further elaboration. Suggested prompts can be included in the interview guide to be used/deployed depending on how the initial question was answered or if the topic of the prompt does not emerge spontaneously.

A form of interview that follows a strict set of questions, asked in a particular order, for all interview subjects. The questions are also the kind that elicits short answers, and the data is more “informative” than probing. This is often used in mixed-methods studies, accompanying a survey instrument. Because there is no room for nuance or the exploration of meaning in structured interviews, qualitative researchers tend to employ semi-structured interviews instead. See also interview.

The point at which you can conclude data collection because every person you are interviewing, the interaction you are observing, or content you are analyzing merely confirms what you have already noted. Achieving saturation is often used as the justification for the final sample size.

An interview variant in which a person’s life story is elicited in a narrative form. Turning points and key themes are established by the researcher and used as data points for further analysis.

Introduction to Qualitative Research Methods Copyright © 2023 by Allison Hurst is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Chapter 13: Interviews

Danielle Berkovic

Learning outcomes

Upon completion of this chapter, you should be able to:

- Understand when to use interviews in qualitative research.

- Develop interview questions for an interview guide.

- Understand how to conduct an interview.

What are interviews?

An interviewing method is the most commonly used data collection technique in qualitative research. 1 The purpose of an interview is to explore the experiences, understandings, opinions and motivations of research participants. 2 Interviews are conducted one-on-one with the researcher and the participant. Interviews are most appropriate when seeking to understand a participant’s subjective view of an experience and are also considered suitable for the exploration of sensitive topics.

What are the different types of interviews?

There are four main types of interviews:

- Key stakeholder: A key stakeholder interview aims to explore one issue in detail with a person of interest or importance concerning the research topic. 3 Key stakeholder interviews seek the views of experts on some cultural, political or health aspects of the community, beyond their personal beliefs or actions. An example of a key stakeholder is the Chief Health Officer of Victoria (Australia’s second-most populous state) who oversaw the world’s longest lockdowns in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Dyad: A dyad interview aims to explore one issue in a level of detail with a dyad (two people). This form of interviewing is used when one participant of the dyad may need some support or is not wholly able to articulate themselves (e.g. people with cognitive impairment, or children). Independence is acknowledged and the interview is analysed as a unit. 4

- Narrative: A narrative interview helps individuals tell their stories, and prioritises their own perspectives and experiences using the language that they prefer. 5 This type of interview has been widely used in social research but is gaining prominence in health research to better understand person-centred care, for example, negotiating exercise and food abstinence whilst living with Type 2 diabetes. 6,7

- Life history: A life history interview allows the researcher to explore a person’s individual and subjective experiences within a history of the time framework. 8 Life history interviews challenge the researcher to understand how people’s current attitudes, behaviours and choices are influenced by previous experiences or trauma. Life history interviews have been conducted with Holocaust survivors 9 and youth who have been forcibly recruited to war. 10

Table 13.4 provides a summary of four studies, each adopting one of these types of interviews.

Interviewing techniques

There are two main interview techniques:

- Semi-structured: Semi-structured interviewing aims to explore a few issues in moderate detail, to expand the researcher’s knowledge at some level. 11 Semi-structured interviews give the researcher the advantage of remaining reasonably objective while enabling participants to share their perspectives and opinions. The researcher should create an interview guide with targeted open questions to direct the interview. As examples, semi-structured interviews have been used to extend knowledge of why women might gain excess weight during pregnancy, 12 and to update guidelines for statin uptake. 13

- In-depth: In-depth interviewing aims to explore a person’s subjective experiences and feelings about a particular topic. 14 In-depth interviews are often used to explore emotive (e.g. end-of-life care) 15 and complex (e.g. adolescent pregnancy) topics. 16 The researcher should create an interview guide with selected open questions to ask of the participant, but the participant should guide the direction of the interview more than in a semi-structured setting. In-depth interviews value participants’ lived experiences and are frequently used in phenomenology studies (as described in Chapter 6) .

When to use the different types of interview s

The type of interview a researcher uses should be determined by the study design, the research aims and objectives, and participant demographics. For example, if conducting a descriptive study, semi-structured interviews may be the best method of data collection. As explained in Chapter 5 , descriptive studies seek to describe phenomena, rather than to explain or interpret the data. A semi-structured interview, which seeks to expand upon some level of existing knowledge, will likely best facilitate this.

Similarly, if conducting a phenomenological study, in-depth interviews may be the best method of data collection. As described in Chapter 6 , the key concept of phenomenology is the individual. The emphasis is on the lived experience of that individual and the person’s sense-making of those experiences. Therefore, an in-depth interview is likely best placed to elicit that rich data.

While some interview types are better suited to certain study designs, there are no restrictions on the type of interview that may be used. For example, semi-structured interviews provide an excellent accompaniment to trial participation (see Chapter 11 about mixed methods), and key stakeholder interviews, as part of an action research study, can be used to define priorities, barriers and enablers to implementation.

How do I write my interview questions?

An interview aims to explore the experiences, understandings, opinions and motivations of research participants. The general rule is that the interviewee should speak for 80 per cent of the interview, and the interviewer should only be asking questions and clarifying responses, for about 20 per cent of the interview. This percentage may differ depending on the interview type; for example, a semi-structured interview involves the researcher asking more questions than in an in-depth interview. Still, to facilitate free-flowing responses, it is important to use open-ended language to encourage participants to be expansive in their responses. Examples of open-ended terms include questions that start with ‘who’, ‘how’ and ‘where’.

The researcher should avoid closed-ended questions that can be answered with yes or no, and limit conversation. For example, asking a participant ‘Did you have this experience?’ can elicit a simple ‘yes’, whereas asking them to ‘Describe your experience’, will likely encourage a narrative response. Table 13.1 provides examples of terminology to include and avoid in developing interview questions.

Table 13.1. Interview question formats to use and avoid

How long should my interview be.

There is no rule about how long an interview should take. Different types of interviews will likely run for different periods of time, but this also depends on the research question/s and the type of participant. For example, given that a semi-structured interview is seeking to expand on some previous knowledge, the interview may need no longer than 30 minutes, or up to one hour. An in-depth interview seeks to explore a topic in a greater level of detail and therefore, at a minimum, would be expected to last an hour. A dyad interview may be as short as 15 minutes (e.g. if the dyad is a person with dementia and a family member or caregiver) or longer, depending on the pairing.

Designing your interview guide

To figure out what questions to ask in an interview guide, the researcher may consult the literature, speak to experts (including people with lived experience) about the research and draw on their current knowledge. The topics and questions should be mapped to the research question/s, and the interview guide should be developed well in advance of commencing data collection. This enables time and opportunity to pilot-test the interview guide. The pilot interview provides an opportunity to explore the language and clarity of questions, the order and flow of the guide and to determine whether the instructions are clear to participants both before and after the interview. It can be beneficial to pilot-test the interview guide with someone who is not familiar with the research topic, to make sure that the language used is easily understood (and will be by participants, too). The study design should be used to determine the number of questions asked and the duration of the interview should guide the extent of the interview guide. The participant type may also determine the extent of the interview guide; for example, clinicians tend to be time-poor and therefore shorter, focused interviews are optimal. An interview guide is also likely to be shorter for a descriptive study than a phenomenological or ethnographic study, given the level of detail required. Chapter 5 outlined a descriptive study in which participants who had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention were interviewed. The interview guide consisted of four main questions and subsequent probing questions, linked to the research questions (see Table 13.2). 17

Table 13.2. Interview guide for a descriptive study

Table 13.3 is an example of a larger and more detailed interview guide, designed for the qualitative component of a mixed-methods study aiming to examine the work and financial effects of living with arthritis as a younger person. The questions are mapped to the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health, which measures health and disability at individual and population levels. 18

Table 13.3. Detailed interview guide

It is important to create an interview guide, for the following reasons:

- The researcher should be familiar with their research questions.

- Using an interview guide will enable the incorporation of feedback from the piloting process.

- It is difficult to predict how participants will respond to interview questions. They may answer in a way that is anticipated or they may provide unanticipated insights that warrant follow-up. An interview guide (a physical or digital copy) enables the researcher to note these answers and follow-up with appropriate inquiry.

- Participants will likely have provided heterogeneous answers to certain questions. The interview guide enables the researcher to note similarities and differences across various interviews, which may be important in data analysis.

- Even experienced qualitative researchers get nervous before an interview! The interview guide provides a safety net if the researcher forgets their questions or needs to anticipate the next question.

Setting up the interview

In the past, most interviews were conducted in person or by telephone. Emerging technologies promote easier access to research participation (e.g. by people living in rural or remote communities, or for people with mobility limitations). Even in metropolitan settings, many interviews are now conducted electronically (e.g. using videoconferencing platforms). Regardless of your interview setting, it is essential that the interview environment is comfortable for the participant. This process can begin as soon as potential participants express interest in your research. Following are some tips from the literature and our own experiences of leading interviews:

- Answer questions and set clear expectations . Participating in research is not an everyday task. People do not necessarily know what to expect during a research interview, and this can be daunting. Give people as much information as possible, answer their questions about the research and set clear expectations about what the interview will entail and how long it is expected to last. Let them know that the interview will be recorded for transcription and analysis purposes. Consider sending the interview questions a few days before the interview. This gives people time and space to reflect on their experiences, consider their responses to questions and to provide informed consent for their participation.

- Consider your setting . If conducting the interview in person, consider the location and room in which the interview will be held. For example, if in a participant’s home, be mindful of their private space. Ask if you should remove your shoes before entering their home. If they offer refreshments (which in our experience many participants do), accept it with gratitude if possible. These considerations apply beyond the participant’s home; if using a room in an office setting, consider privacy and confidentiality, accessibility and potential for disruption. Consider the temperature as well as the furniture in the room, who may be able to overhear conversations and who may walk past. Similarly, if interviewing by phone or online, take time to assess the space, and if in a house or office that is not quiet or private, use headphones as needed.

- Build rapport. The research topic may be important to participants from a professional perspective, or they may have deep emotional connections to the topic of interest. Regardless of the nature of the interview, it is important to remember that participants are being asked to open up to an interviewer who is likely to be a stranger. Spend some time with participants before the interview, to make sure that they are comfortable. Engage in some general conversation, and ask if they have any questions before you start. Remember that it is not a normal part of someone’s day to participate in research. Make it an enjoyable and/or meaningful experience for them, and it will enhance the data that you collect.

- Let participants guide you. Oftentimes, the ways in which researchers and participants describe the same phenomena are different. In the interview, reflect the participant’s language. Make sure they feel heard and that they are willing and comfortable to speak openly about their experiences. For example, our research involves talking to older adults about their experience of falls. We noticed early in this research that participants did not use the word ‘fall’ but would rather use terms such as ‘trip’, ‘went over’ and ‘stumbled’. As interviewers we adopted the participant’s language into our questions.

- Listen consistently and express interest. An interview is more complex than a simple question-and-answer format. The best interview data comes from participants feeling comfortable and confident to share their stories. By the time you are completing the 20th interview, it can be difficult to maintain the same level of concentration as with the first interview. Try to stay engaged: nod along with your participants, maintain eye contact, murmur in agreement and sympathise where warranted.

- The interviewer is both the data collector and the data collection instrument. The data received is only as good as the questions asked. In qualitative research, the researcher influences how participants answer questions. It is important to remain reflexive and aware of how your language, body language and attitude might influence the interview. Being rested and prepared will enhance the quality of the questions asked and hence the data collected.

- Avoid excessive use of ‘why’. It can be challenging for participants to recall why they felt a certain way or acted in a particular manner. Try to avoid asking ‘why’ questions too often, and instead adopt some of the open language described earlier in the chapter.

After your interview

When you have completed your interview, thank the participant and let them know they can contact you if they have any questions or follow-up information they would like to provide. If the interview has covered sensitive topics or the participant has become distressed throughout the interview, make sure that appropriate referrals and follow-up are provided (see section 6).

Download the recording from your device and make sure it is saved in a secure location that can only be accessed by people on the approved research team (see Chapters 35 and 36).

It is important to know what to do immediately after each interview is completed. Interviews should be transcribed – that is, reproduced verbatim for data analysis. Transcribing data is an important step in the process of analysis, but it is very time-consuming; transcribing a 60-minute interview can take up to 8 hours. Data analysis is discussed in Section 4.

Table 13.4. Examples of the four types of interviews

Interviews are the most common data collection technique in qualitative research. There are four main types of interviews; the one you choose will depend on your research question, aims and objectives. It is important to formulate open-ended interview questions that are understandable and easy for participants to answer. Key considerations in setting up the interview will enhance the quality of the data obtained and the experience of the interview for the participant and the researcher.

- Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J . 2008;204(6):291-295. doi:10.1038/bdj.2008.192

- DeJonckheere M, Vaughn LM. Semistructured interviewing in primary care research: a balance of relationship and rigour. Fam Med Community Health . 2019;7(2):e000057. doi:10.1136/fmch-2018-000057

- Nyanchoka L, Tudur-Smith C, Porcher R, Hren D. Key stakeholders’ perspectives and experiences with defining, identifying and displaying gaps in health research: a qualitative study. BMJ Open . 2020;10(11):e039932. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039932

- Morgan DL, Ataie J, Carder P, Hoffman K. Introducing dyadic interviews as a method for collecting qualitative data. Qual Health Res . 2013;23(9):1276-84. doi:10.1177/1049732313501889

- Picchi S, Bonapitacola C, Borghi E, et al. The narrative interview in therapeutic education. The diabetic patients’ point of view. Acta Biomed . Jul 18 2018;89(6-S):43-50. doi:10.23750/abm.v89i6-S.7488

- Stuij M, Elling A, Abma T. Negotiating exercise as medicine: Narratives from people with type 2 diabetes. Health (London) . 2021;25(1):86-102. doi:10.1177/1363459319851545

- Buchmann M, Wermeling M, Lucius-Hoene G, Himmel W. Experiences of food abstinence in patients with type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study. BMJ Open . 2016;6(1):e008907. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-008907

- Jessee E. The Life History Interview. Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences . 2018:1-17:Chapter 80-1.

- Sheftel A, Zembrzycki S. Only Human: A Reflection on the Ethical and Methodological Challenges of Working with “Difficult” Stories. The Oral History Review . 2019;37(2):191-214. doi:10.1093/ohr/ohq050

- Harnisch H, Montgomery E. “What kept me going”: A qualitative study of avoidant responses to war-related adversity and perpetration of violence by former forcibly recruited children and youth in the Acholi region of northern Uganda. Soc Sci Med . 2017;188:100-108. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.07.007

- Ruslin., Mashuri S, Rasak MSA, Alhabsyi M, Alhabsyi F, Syam H. Semi-structured Interview: A Methodological Reflection on the Development of a Qualitative Research Instrument in Educational Studies. IOSR-JRME . 2022;12(1):22-29. doi:10.9790/7388-1201052229

- Chang T, Llanes M, Gold KJ, Fetters MD. Perspectives about and approaches to weight gain in pregnancy: a qualitative study of physicians and nurse midwives. BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth . 2013;13(47)doi:10.1186/1471-2393-13-47

- DeJonckheere M, Robinson CH, Evans L, et al. Designing for Clinical Change: Creating an Intervention to Implement New Statin Guidelines in a Primary Care Clinic. JMIR Hum Factors . 2018;5(2):e19. doi:10.2196/humanfactors.9030

- Knott E, Rao AH, Summers K, Teeger C. Interviews in the social sciences. Nature Reviews Methods Primers . 2022;2(1)doi:10.1038/s43586-022-00150-6

- Bergenholtz H, Missel M, Timm H. Talking about death and dying in a hospital setting – a qualitative study of the wishes for end-of-life conversations from the perspective of patients and spouses. BMC Palliat Care . 2020;19(1):168. doi:10.1186/s12904-020-00675-1

- Olorunsaiye CZ, Degge HM, Ubanyi TO, Achema TA, Yaya S. “It’s like being involved in a car crash”: teen pregnancy narratives of adolescents and young adults in Jos, Nigeria. Int Health . 2022;14(6):562-571. doi:10.1093/inthealth/ihab069

- Ayton DR, Barker AL, Peeters G, et al. Exploring patient-reported outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention: A qualitative study. Health Expect . 2018;21(2):457-465. doi:10.1111/hex.12636

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). WHO. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health#:~:text=ICF%20is%20the%20WHO%20framework,and%20measure%20health%20and%20disability.

- Cuthbertson J, Rodriguez-Llanes JM, Robertson A, Archer F. Current and Emerging Disaster Risks Perceptions in Oceania: Key Stakeholders Recommendations for Disaster Management and Resilience Building. Int J Environ Res Public Health . 2019;16(3)doi:10.3390/ijerph16030460

- Bannon SM, Grunberg VA, Reichman M, et al. Thematic Analysis of Dyadic Coping in Couples With Young-Onset Dementia. JAMA Netw Open . 2021;4(4):e216111. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.6111

- McGranahan R, Jakaite Z, Edwards A, Rennick-Egglestone S, Slade M, Priebe S. Living with Psychosis without Mental Health Services: A Narrative Interview Study. BMJ Open . 2021;11(7):e045661. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045661

- Gutiérrez-García AI, Solano-Ruíz C, Siles-González J, Perpiñá-Galvañ J. Life Histories and Lifelines: A Methodological Symbiosis for the Study of Female Genital Mutilation. Int J Qual Methods . 2021;20doi:10.1177/16094069211040969

Qualitative Research – a practical guide for health and social care researchers and practitioners Copyright © 2023 by Danielle Berkovic is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- University Libraries

- Research Guides

- Topic Guides

- Research Methods Guide

- Interview Research

Research Methods Guide: Interview Research

- Introduction

- Research Design & Method

- Survey Research

- Data Analysis

- Resources & Consultation

Tutorial Videos: Interview Method

Interview as a Method for Qualitative Research

Goals of Interview Research

- Preferences

- They help you explain, better understand, and explore research subjects' opinions, behavior, experiences, phenomenon, etc.

- Interview questions are usually open-ended questions so that in-depth information will be collected.

Mode of Data Collection

There are several types of interviews, including:

- Face-to-Face

- Online (e.g. Skype, Googlehangout, etc)

FAQ: Conducting Interview Research

What are the important steps involved in interviews?

- Think about who you will interview

- Think about what kind of information you want to obtain from interviews

- Think about why you want to pursue in-depth information around your research topic

- Introduce yourself and explain the aim of the interview

- Devise your questions so interviewees can help answer your research question

- Have a sequence to your questions / topics by grouping them in themes

- Make sure you can easily move back and forth between questions / topics

- Make sure your questions are clear and easy to understand

- Do not ask leading questions

- Do you want to bring a second interviewer with you?

- Do you want to bring a notetaker?

- Do you want to record interviews? If so, do you have time to transcribe interview recordings?

- Where will you interview people? Where is the setting with the least distraction?

- How long will each interview take?

- Do you need to address terms of confidentiality?

Do I have to choose either a survey or interviewing method?

No. In fact, many researchers use a mixed method - interviews can be useful as follow-up to certain respondents to surveys, e.g., to further investigate their responses.

Is training an interviewer important?

Yes, since the interviewer can control the quality of the result, training the interviewer becomes crucial. If more than one interviewers are involved in your study, it is important to have every interviewer understand the interviewing procedure and rehearse the interviewing process before beginning the formal study.

- << Previous: Survey Research

- Next: Data Analysis >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 10:42 AM

Research Methodologies: Research Instruments

- Research Methodology Basics

- Research Instruments

- Types of Research Methodologies

Header Image

Types of Research Instruments

A research instrument is a tool you will use to help you collect, measure and analyze the data you use as part of your research. The choice of research instrument will usually be yours to make as the researcher and will be whichever best suits your methodology.

There are many different research instruments you can use in collecting data for your research:

- Interviews (either as a group or one-on-one). You can carry out interviews in many different ways. For example, your interview can be structured, semi-structured, or unstructured. The difference between them is how formal the set of questions is that is asked of the interviewee. In a group interview, you may choose to ask the interviewees to give you their opinions or perceptions on certain topics.

- Surveys (online or in-person). In survey research, you are posing questions in which you ask for a response from the person taking the survey. You may wish to have either free-answer questions such as essay style questions, or you may wish to use closed questions such as multiple choice. You may even wish to make the survey a mixture of both.

- Focus Groups. Similar to the group interview above, you may wish to ask a focus group to discuss a particular topic or opinion while you make a note of the answers given.

- Observations. This is a good research instrument to use if you are looking into human behaviors. Different ways of researching this include studying the spontaneous behavior of participants in their everyday life, or something more structured. A structured observation is research conducted at a set time and place where researchers observe behavior as planned and agreed upon with participants.

These are the most common ways of carrying out research, but it is really dependent on your needs as a researcher and what approach you think is best to take. It is also possible to combine a number of research instruments if this is necessary and appropriate in answering your research problem.

Data Collection

How to Collect Data for Your Research This article covers different ways of collecting data in preparation for writing a thesis.

- << Previous: Research Methodology Basics

- Next: Types of Research Methodologies >>

- Last Updated: Sep 27, 2022 12:28 PM

- URL: https://paperpile.libguides.com/research-methodologies

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Types of Interviews in Research and Methods

There are more types of interviews than most people think. An interview is generally a qualitative research technique that involves asking open-ended questions to converse with respondents and collect elicit data about a subject.

The interviewer, in most cases, is the subject matter expert who intends to understand respondent opinions in a well-planned and executed series of star questions and answers .

Interviews are similar to focus groups and surveys for garnering information from the target market but are entirely different in their operation – focus groups are restricted to a small group of 6-10 individuals, whereas surveys are quantitative.

Interviews are conducted with a sample from a population, and the key characteristic they exhibit is their conversational tone.

LEARN ABOUT: telephone survey

Content Index

What is An Interview?

Fundamental types of interviews in research, other types of interviews.

- Methods of Research Interviews

What to Avoid in Different Types of Interviews

- Interview-Related Questions

An interview is a way to get information from a person by asking questions and hearing their answers.

An interview is a question-and-answer session where one person asks questions, and the other person answers those questions. It can be a one-on-one, two-way conversation, or there can be more than one interviewer and more than one participant.

The interview is the most important part of the whole selection bias process. It is used to decide if a person should be interviewed further, hired, or taken out of consideration. It is the main way to learn more about applicants and the basis for judging their job-related knowledge, research skills , and abilities.

A researcher has to conduct interviews with a group of participants at a juncture in the research where information can only be obtained by meeting and personally connecting with a section of their target audience. Interviews offer the researchers a platform to prompt their participants and obtain inputs in the desired detail. There are three fundamental types of interviews in research:

1. Structured Interviews:

Structured interviews are defined as research tools that could be more flexible in their operations are allow more or no scope of prompting the participants to obtain and analyze results. It is thus also known as a standardized interview and is significantly quantitative in its approach.

Questions in this interview are pre-decided according to the required detail of information. This can be used in a focus group interview and an in-person interview.

These interviews are excessively used in survey research with the intention of maintaining uniformity throughout all the interview sessions.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

They can be closed-ended and open-ended – according to the type of target population. Closed-ended questions can be included to understand user preferences from a collection of answer options. In contrast, open-ended ones can be included to gain details about a particular section in the interview.

Example of a structured interview question:

Here’s an example of a structured question for a job interview for a customer service job:

- Can you talk about what it was like to work in customer service?

- How do you deal with an angry or upset customer?

- How do you ensure that the information you give customers is correct?

- Tell us about when you went out of your way to help a customer.

- How do you handle a lot of customers or tasks at once?

- Can you talk about how you’ve used software or tools for customer service?

- How do you set priorities and use your time well while giving good customer service?

- Can you tell us about when you had to get a customer to calm down?

- How do you deal with a customer who wants something that goes against your company’s rules?

- Tell me about a time when you had to deal with a hard customer or coworker.

Advantages of structured interviews:

- It focuses on the accuracy of different responses, due to which extremely organized data can be collected. Different respondents have different types of answers to the same structure of questions – answers obtained can be collectively analyzed.

- They can be used to get in touch with a large sample of the target population.

- The interview procedure is made easy due to the standardization offered by it.

- Replication across multiple samples becomes easy due to the same structure of the interview.

- As the scope of detail is already considered while designing the interview questions, better information can be obtained. The researcher can analyze the research problem comprehensively by asking accurate research questions .