Writing an Introduction for a Scientific Paper

Dr. michelle harris, dr. janet batzli, biocore.

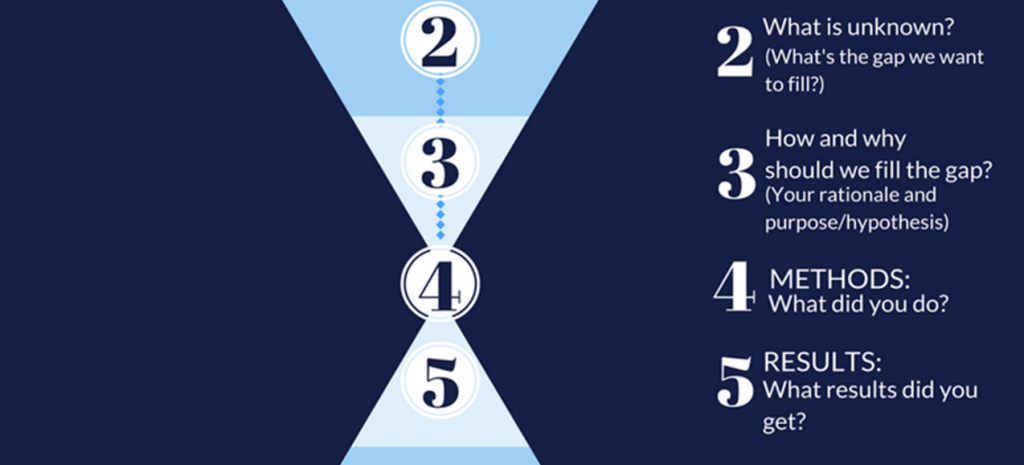

This section provides guidelines on how to construct a solid introduction to a scientific paper including background information, study question , biological rationale, hypothesis , and general approach . If the Introduction is done well, there should be no question in the reader’s mind why and on what basis you have posed a specific hypothesis.

Broad Question : based on an initial observation (e.g., “I see a lot of guppies close to the shore. Do guppies like living in shallow water?”). This observation of the natural world may inspire you to investigate background literature or your observation could be based on previous research by others or your own pilot study. Broad questions are not always included in your written text, but are essential for establishing the direction of your research.

Background Information : key issues, concepts, terminology, and definitions needed to understand the biological rationale for the experiment. It often includes a summary of findings from previous, relevant studies. Remember to cite references, be concise, and only include relevant information given your audience and your experimental design. Concisely summarized background information leads to the identification of specific scientific knowledge gaps that still exist. (e.g., “No studies to date have examined whether guppies do indeed spend more time in shallow water.”)

Testable Question : these questions are much more focused than the initial broad question, are specific to the knowledge gap identified, and can be addressed with data. (e.g., “Do guppies spend different amounts of time in water <1 meter deep as compared to their time in water that is >1 meter deep?”)

Biological Rationale : describes the purpose of your experiment distilling what is known and what is not known that defines the knowledge gap that you are addressing. The “BR” provides the logic for your hypothesis and experimental approach, describing the biological mechanism and assumptions that explain why your hypothesis should be true.

The biological rationale is based on your interpretation of the scientific literature, your personal observations, and the underlying assumptions you are making about how you think the system works. If you have written your biological rationale, your reader should see your hypothesis in your introduction section and say to themselves, “Of course, this hypothesis seems very logical based on the rationale presented.”

- A thorough rationale defines your assumptions about the system that have not been revealed in scientific literature or from previous systematic observation. These assumptions drive the direction of your specific hypothesis or general predictions.

- Defining the rationale is probably the most critical task for a writer, as it tells your reader why your research is biologically meaningful. It may help to think about the rationale as an answer to the questions— how is this investigation related to what we know, what assumptions am I making about what we don’t yet know, AND how will this experiment add to our knowledge? *There may or may not be broader implications for your study; be careful not to overstate these (see note on social justifications below).

- Expect to spend time and mental effort on this. You may have to do considerable digging into the scientific literature to define how your experiment fits into what is already known and why it is relevant to pursue.

- Be open to the possibility that as you work with and think about your data, you may develop a deeper, more accurate understanding of the experimental system. You may find the original rationale needs to be revised to reflect your new, more sophisticated understanding.

- As you progress through Biocore and upper level biology courses, your rationale should become more focused and matched with the level of study e ., cellular, biochemical, or physiological mechanisms that underlie the rationale. Achieving this type of understanding takes effort, but it will lead to better communication of your science.

***Special note on avoiding social justifications: You should not overemphasize the relevance of your experiment and the possible connections to large-scale processes. Be realistic and logical —do not overgeneralize or state grand implications that are not sensible given the structure of your experimental system. Not all science is easily applied to improving the human condition. Performing an investigation just for the sake of adding to our scientific knowledge (“pure or basic science”) is just as important as applied science. In fact, basic science often provides the foundation for applied studies.

Hypothesis / Predictions : specific prediction(s) that you will test during your experiment. For manipulative experiments, the hypothesis should include the independent variable (what you manipulate), the dependent variable(s) (what you measure), the organism or system , the direction of your results, and comparison to be made.

If you are doing a systematic observation , your hypothesis presents a variable or set of variables that you predict are important for helping you characterize the system as a whole, or predict differences between components/areas of the system that help you explain how the system functions or changes over time.

Experimental Approach : Briefly gives the reader a general sense of the experiment, the type of data it will yield, and the kind of conclusions you expect to obtain from the data. Do not confuse the experimental approach with the experimental protocol . The experimental protocol consists of the detailed step-by-step procedures and techniques used during the experiment that are to be reported in the Methods and Materials section.

Some Final Tips on Writing an Introduction

- As you progress through the Biocore sequence, for instance, from organismal level of Biocore 301/302 to the cellular level in Biocore 303/304, we expect the contents of your “Introduction” paragraphs to reflect the level of your coursework and previous writing experience. For example, in Biocore 304 (Cell Biology Lab) biological rationale should draw upon assumptions we are making about cellular and biochemical processes.

- Be Concise yet Specific: Remember to be concise and only include relevant information given your audience and your experimental design. As you write, keep asking, “Is this necessary information or is this irrelevant detail?” For example, if you are writing a paper claiming that a certain compound is a competitive inhibitor to the enzyme alkaline phosphatase and acts by binding to the active site, you need to explain (briefly) Michaelis-Menton kinetics and the meaning and significance of Km and Vmax. This explanation is not necessary if you are reporting the dependence of enzyme activity on pH because you do not need to measure Km and Vmax to get an estimate of enzyme activity.

- Another example: if you are writing a paper reporting an increase in Daphnia magna heart rate upon exposure to caffeine you need not describe the reproductive cycle of magna unless it is germane to your results and discussion. Be specific and concrete, especially when making introductory or summary statements.

Where Do You Discuss Pilot Studies? Many times it is important to do pilot studies to help you get familiar with your experimental system or to improve your experimental design. If your pilot study influences your biological rationale or hypothesis, you need to describe it in your Introduction. If your pilot study simply informs the logistics or techniques, but does not influence your rationale, then the description of your pilot study belongs in the Materials and Methods section.

How will introductions be evaluated? The following is part of the rubric we will be using to evaluate your papers.

What Is A Research (Scientific) Hypothesis? A plain-language explainer + examples

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewed By: Dr Eunice Rautenbach | June 2020

If you’re new to the world of research, or it’s your first time writing a dissertation or thesis, you’re probably noticing that the words “research hypothesis” and “scientific hypothesis” are used quite a bit, and you’re wondering what they mean in a research context .

“Hypothesis” is one of those words that people use loosely, thinking they understand what it means. However, it has a very specific meaning within academic research. So, it’s important to understand the exact meaning before you start hypothesizing.

Research Hypothesis 101

- What is a hypothesis ?

- What is a research hypothesis (scientific hypothesis)?

- Requirements for a research hypothesis

- Definition of a research hypothesis

- The null hypothesis

What is a hypothesis?

Let’s start with the general definition of a hypothesis (not a research hypothesis or scientific hypothesis), according to the Cambridge Dictionary:

Hypothesis: an idea or explanation for something that is based on known facts but has not yet been proved.

In other words, it’s a statement that provides an explanation for why or how something works, based on facts (or some reasonable assumptions), but that has not yet been specifically tested . For example, a hypothesis might look something like this:

Hypothesis: sleep impacts academic performance.

This statement predicts that academic performance will be influenced by the amount and/or quality of sleep a student engages in – sounds reasonable, right? It’s based on reasonable assumptions , underpinned by what we currently know about sleep and health (from the existing literature). So, loosely speaking, we could call it a hypothesis, at least by the dictionary definition.

But that’s not good enough…

Unfortunately, that’s not quite sophisticated enough to describe a research hypothesis (also sometimes called a scientific hypothesis), and it wouldn’t be acceptable in a dissertation, thesis or research paper . In the world of academic research, a statement needs a few more criteria to constitute a true research hypothesis .

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis (also called a scientific hypothesis) is a statement about the expected outcome of a study (for example, a dissertation or thesis). To constitute a quality hypothesis, the statement needs to have three attributes – specificity , clarity and testability .

Let’s take a look at these more closely.

Need a helping hand?

Hypothesis Essential #1: Specificity & Clarity

A good research hypothesis needs to be extremely clear and articulate about both what’ s being assessed (who or what variables are involved ) and the expected outcome (for example, a difference between groups, a relationship between variables, etc.).

Let’s stick with our sleepy students example and look at how this statement could be more specific and clear.

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

As you can see, the statement is very specific as it identifies the variables involved (sleep hours and test grades), the parties involved (two groups of students), as well as the predicted relationship type (a positive relationship). There’s no ambiguity or uncertainty about who or what is involved in the statement, and the expected outcome is clear.

Contrast that to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – and you can see the difference. “Sleep” and “academic performance” are both comparatively vague , and there’s no indication of what the expected relationship direction is (more sleep or less sleep). As you can see, specificity and clarity are key.

Hypothesis Essential #2: Testability (Provability)

A statement must be testable to qualify as a research hypothesis. In other words, there needs to be a way to prove (or disprove) the statement. If it’s not testable, it’s not a hypothesis – simple as that.

For example, consider the hypothesis we mentioned earlier:

Hypothesis: Students who sleep at least 8 hours per night will, on average, achieve higher grades in standardised tests than students who sleep less than 8 hours a night.

We could test this statement by undertaking a quantitative study involving two groups of students, one that gets 8 or more hours of sleep per night for a fixed period, and one that gets less. We could then compare the standardised test results for both groups to see if there’s a statistically significant difference.

Again, if you compare this to the original hypothesis we looked at – “Sleep impacts academic performance” – you can see that it would be quite difficult to test that statement, primarily because it isn’t specific enough. How much sleep? By who? What type of academic performance?

So, remember the mantra – if you can’t test it, it’s not a hypothesis 🙂

Defining A Research Hypothesis

You’re still with us? Great! Let’s recap and pin down a clear definition of a hypothesis.

A research hypothesis (or scientific hypothesis) is a statement about an expected relationship between variables, or explanation of an occurrence, that is clear, specific and testable.

So, when you write up hypotheses for your dissertation or thesis, make sure that they meet all these criteria. If you do, you’ll not only have rock-solid hypotheses but you’ll also ensure a clear focus for your entire research project.

What about the null hypothesis?

You may have also heard the terms null hypothesis , alternative hypothesis, or H-zero thrown around. At a simple level, the null hypothesis is the counter-proposal to the original hypothesis.

For example, if the hypothesis predicts that there is a relationship between two variables (for example, sleep and academic performance), the null hypothesis would predict that there is no relationship between those variables.

At a more technical level, the null hypothesis proposes that no statistical significance exists in a set of given observations and that any differences are due to chance alone.

And there you have it – hypotheses in a nutshell.

If you have any questions, be sure to leave a comment below and we’ll do our best to help you. If you need hands-on help developing and testing your hypotheses, consider our private coaching service , where we hold your hand through the research journey.

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

You Might Also Like:

16 Comments

Very useful information. I benefit more from getting more information in this regard.

Very great insight,educative and informative. Please give meet deep critics on many research data of public international Law like human rights, environment, natural resources, law of the sea etc

In a book I read a distinction is made between null, research, and alternative hypothesis. As far as I understand, alternative and research hypotheses are the same. Can you please elaborate? Best Afshin

This is a self explanatory, easy going site. I will recommend this to my friends and colleagues.

Very good definition. How can I cite your definition in my thesis? Thank you. Is nul hypothesis compulsory in a research?

It’s a counter-proposal to be proven as a rejection

Please what is the difference between alternate hypothesis and research hypothesis?

It is a very good explanation. However, it limits hypotheses to statistically tasteable ideas. What about for qualitative researches or other researches that involve quantitative data that don’t need statistical tests?

In qualitative research, one typically uses propositions, not hypotheses.

could you please elaborate it more

I’ve benefited greatly from these notes, thank you.

This is very helpful

well articulated ideas are presented here, thank you for being reliable sources of information

Excellent. Thanks for being clear and sound about the research methodology and hypothesis (quantitative research)

I have only a simple question regarding the null hypothesis. – Is the null hypothesis (Ho) known as the reversible hypothesis of the alternative hypothesis (H1? – How to test it in academic research?

this is very important note help me much more

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

- What Is Research Methodology? Simple Definition (With Examples) - Grad Coach - […] Contrasted to this, a quantitative methodology is typically used when the research aims and objectives are confirmatory in nature. For example,…

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 4. The Introduction

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

The introduction leads the reader from a general subject area to a particular topic of inquiry. It establishes the scope, context, and significance of the research being conducted by summarizing current understanding and background information about the topic, stating the purpose of the work in the form of the research problem supported by a hypothesis or a set of questions, explaining briefly the methodological approach used to examine the research problem, highlighting the potential outcomes your study can reveal, and outlining the remaining structure and organization of the paper.

Key Elements of the Research Proposal. Prepared under the direction of the Superintendent and by the 2010 Curriculum Design and Writing Team. Baltimore County Public Schools.

Importance of a Good Introduction

Think of the introduction as a mental road map that must answer for the reader these four questions:

- What was I studying?

- Why was this topic important to investigate?

- What did we know about this topic before I did this study?

- How will this study advance new knowledge or new ways of understanding?

According to Reyes, there are three overarching goals of a good introduction: 1) ensure that you summarize prior studies about the topic in a manner that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem; 2) explain how your study specifically addresses gaps in the literature, insufficient consideration of the topic, or other deficiency in the literature; and, 3) note the broader theoretical, empirical, and/or policy contributions and implications of your research.

A well-written introduction is important because, quite simply, you never get a second chance to make a good first impression. The opening paragraphs of your paper will provide your readers with their initial impressions about the logic of your argument, your writing style, the overall quality of your research, and, ultimately, the validity of your findings and conclusions. A vague, disorganized, or error-filled introduction will create a negative impression, whereas, a concise, engaging, and well-written introduction will lead your readers to think highly of your analytical skills, your writing style, and your research approach. All introductions should conclude with a brief paragraph that describes the organization of the rest of the paper.

Hirano, Eliana. “Research Article Introductions in English for Specific Purposes: A Comparison between Brazilian, Portuguese, and English.” English for Specific Purposes 28 (October 2009): 240-250; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide. Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Reyes, Victoria. Demystifying the Journal Article. Inside Higher Education.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Structure and Approach

The introduction is the broad beginning of the paper that answers three important questions for the reader:

- What is this?

- Why should I read it?

- What do you want me to think about / consider doing / react to?

Think of the structure of the introduction as an inverted triangle of information that lays a foundation for understanding the research problem. Organize the information so as to present the more general aspects of the topic early in the introduction, then narrow your analysis to more specific topical information that provides context, finally arriving at your research problem and the rationale for studying it [often written as a series of key questions to be addressed or framed as a hypothesis or set of assumptions to be tested] and, whenever possible, a description of the potential outcomes your study can reveal.

These are general phases associated with writing an introduction: 1. Establish an area to research by:

- Highlighting the importance of the topic, and/or

- Making general statements about the topic, and/or

- Presenting an overview on current research on the subject.

2. Identify a research niche by:

- Opposing an existing assumption, and/or

- Revealing a gap in existing research, and/or

- Formulating a research question or problem, and/or

- Continuing a disciplinary tradition.

3. Place your research within the research niche by:

- Stating the intent of your study,

- Outlining the key characteristics of your study,

- Describing important results, and

- Giving a brief overview of the structure of the paper.

NOTE: It is often useful to review the introduction late in the writing process. This is appropriate because outcomes are unknown until you've completed the study. After you complete writing the body of the paper, go back and review introductory descriptions of the structure of the paper, the method of data gathering, the reporting and analysis of results, and the conclusion. Reviewing and, if necessary, rewriting the introduction ensures that it correctly matches the overall structure of your final paper.

II. Delimitations of the Study

Delimitations refer to those characteristics that limit the scope and define the conceptual boundaries of your research . This is determined by the conscious exclusionary and inclusionary decisions you make about how to investigate the research problem. In other words, not only should you tell the reader what it is you are studying and why, but you must also acknowledge why you rejected alternative approaches that could have been used to examine the topic.

Obviously, the first limiting step was the choice of research problem itself. However, implicit are other, related problems that could have been chosen but were rejected. These should be noted in the conclusion of your introduction. For example, a delimitating statement could read, "Although many factors can be understood to impact the likelihood young people will vote, this study will focus on socioeconomic factors related to the need to work full-time while in school." The point is not to document every possible delimiting factor, but to highlight why previously researched issues related to the topic were not addressed.

Examples of delimitating choices would be:

- The key aims and objectives of your study,

- The research questions that you address,

- The variables of interest [i.e., the various factors and features of the phenomenon being studied],

- The method(s) of investigation,

- The time period your study covers, and

- Any relevant alternative theoretical frameworks that could have been adopted.

Review each of these decisions. Not only do you clearly establish what you intend to accomplish in your research, but you should also include a declaration of what the study does not intend to cover. In the latter case, your exclusionary decisions should be based upon criteria understood as, "not interesting"; "not directly relevant"; “too problematic because..."; "not feasible," and the like. Make this reasoning explicit!

NOTE: Delimitations refer to the initial choices made about the broader, overall design of your study and should not be confused with documenting the limitations of your study discovered after the research has been completed.

ANOTHER NOTE : Do not view delimitating statements as admitting to an inherent failing or shortcoming in your research. They are an accepted element of academic writing intended to keep the reader focused on the research problem by explicitly defining the conceptual boundaries and scope of your study. It addresses any critical questions in the reader's mind of, "Why the hell didn't the author examine this?"

III. The Narrative Flow

Issues to keep in mind that will help the narrative flow in your introduction :

- Your introduction should clearly identify the subject area of interest . A simple strategy to follow is to use key words from your title in the first few sentences of the introduction. This will help focus the introduction on the topic at the appropriate level and ensures that you get to the subject matter quickly without losing focus, or discussing information that is too general.

- Establish context by providing a brief and balanced review of the pertinent published literature that is available on the subject. The key is to summarize for the reader what is known about the specific research problem before you did your analysis. This part of your introduction should not represent a comprehensive literature review--that comes next. It consists of a general review of the important, foundational research literature [with citations] that establishes a foundation for understanding key elements of the research problem. See the drop-down menu under this tab for " Background Information " regarding types of contexts.

- Clearly state the hypothesis that you investigated . When you are first learning to write in this format it is okay, and actually preferable, to use a past statement like, "The purpose of this study was to...." or "We investigated three possible mechanisms to explain the...."

- Why did you choose this kind of research study or design? Provide a clear statement of the rationale for your approach to the problem studied. This will usually follow your statement of purpose in the last paragraph of the introduction.

IV. Engaging the Reader

A research problem in the social sciences can come across as dry and uninteresting to anyone unfamiliar with the topic . Therefore, one of the goals of your introduction is to make readers want to read your paper. Here are several strategies you can use to grab the reader's attention:

- Open with a compelling story . Almost all research problems in the social sciences, no matter how obscure or esoteric , are really about the lives of people. Telling a story that humanizes an issue can help illuminate the significance of the problem and help the reader empathize with those affected by the condition being studied.

- Include a strong quotation or a vivid, perhaps unexpected, anecdote . During your review of the literature, make note of any quotes or anecdotes that grab your attention because they can used in your introduction to highlight the research problem in a captivating way.

- Pose a provocative or thought-provoking question . Your research problem should be framed by a set of questions to be addressed or hypotheses to be tested. However, a provocative question can be presented in the beginning of your introduction that challenges an existing assumption or compels the reader to consider an alternative viewpoint that helps establish the significance of your study.

- Describe a puzzling scenario or incongruity . This involves highlighting an interesting quandary concerning the research problem or describing contradictory findings from prior studies about a topic. Posing what is essentially an unresolved intellectual riddle about the problem can engage the reader's interest in the study.

- Cite a stirring example or case study that illustrates why the research problem is important . Draw upon the findings of others to demonstrate the significance of the problem and to describe how your study builds upon or offers alternatives ways of investigating this prior research.

NOTE: It is important that you choose only one of the suggested strategies for engaging your readers. This avoids giving an impression that your paper is more flash than substance and does not distract from the substance of your study.

Freedman, Leora and Jerry Plotnick. Introductions and Conclusions. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Introduction. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Introductions. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Introductions, Body Paragraphs, and Conclusions for an Argument Paper. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70; Resources for Writers: Introduction Strategies. Program in Writing and Humanistic Studies. Massachusetts Institute of Technology; Sharpling, Gerald. Writing an Introduction. Centre for Applied Linguistics, University of Warwick; Samraj, B. “Introductions in Research Articles: Variations Across Disciplines.” English for Specific Purposes 21 (2002): 1–17; Swales, John and Christine B. Feak. Academic Writing for Graduate Students: Essential Skills and Tasks . 2nd edition. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2004 ; Writing Your Introduction. Department of English Writing Guide. George Mason University.

Writing Tip

Avoid the "Dictionary" Introduction

Giving the dictionary definition of words related to the research problem may appear appropriate because it is important to define specific terminology that readers may be unfamiliar with. However, anyone can look a word up in the dictionary and a general dictionary is not a particularly authoritative source because it doesn't take into account the context of your topic and doesn't offer particularly detailed information. Also, placed in the context of a particular discipline, a term or concept may have a different meaning than what is found in a general dictionary. If you feel that you must seek out an authoritative definition, use a subject specific dictionary or encyclopedia [e.g., if you are a sociology student, search for dictionaries of sociology]. A good database for obtaining definitive definitions of concepts or terms is Credo Reference .

Saba, Robert. The College Research Paper. Florida International University; Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina.

Another Writing Tip

When Do I Begin?

A common question asked at the start of any paper is, "Where should I begin?" An equally important question to ask yourself is, "When do I begin?" Research problems in the social sciences rarely rest in isolation from history. Therefore, it is important to lay a foundation for understanding the historical context underpinning the research problem. However, this information should be brief and succinct and begin at a point in time that illustrates the study's overall importance. For example, a study that investigates coffee cultivation and export in West Africa as a key stimulus for local economic growth needs to describe the beginning of exporting coffee in the region and establishing why economic growth is important. You do not need to give a long historical explanation about coffee exports in Africa. If a research problem requires a substantial exploration of the historical context, do this in the literature review section. In your introduction, make note of this as part of the "roadmap" [see below] that you use to describe the organization of your paper.

Introductions. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; “Writing Introductions.” In Good Essay Writing: A Social Sciences Guide . Peter Redman. 4th edition. (London: Sage, 2011), pp. 63-70.

Yet Another Writing Tip

Always End with a Roadmap

The final paragraph or sentences of your introduction should forecast your main arguments and conclusions and provide a brief description of the rest of the paper [the "roadmap"] that let's the reader know where you are going and what to expect. A roadmap is important because it helps the reader place the research problem within the context of their own perspectives about the topic. In addition, concluding your introduction with an explicit roadmap tells the reader that you have a clear understanding of the structural purpose of your paper. In this way, the roadmap acts as a type of promise to yourself and to your readers that you will follow a consistent and coherent approach to addressing the topic of inquiry. Refer to it often to help keep your writing focused and organized.

Cassuto, Leonard. “On the Dissertation: How to Write the Introduction.” The Chronicle of Higher Education , May 28, 2018; Radich, Michael. A Student's Guide to Writing in East Asian Studies . (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Writing n. d.), pp. 35-37.

- << Previous: Executive Summary

- Next: The C.A.R.S. Model >>

- Last Updated: May 15, 2024 9:53 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Manuscript Preparation

What is and How to Write a Good Hypothesis in Research?

- 4 minute read

- 313.6K views

Table of Contents

One of the most important aspects of conducting research is constructing a strong hypothesis. But what makes a hypothesis in research effective? In this article, we’ll look at the difference between a hypothesis and a research question, as well as the elements of a good hypothesis in research. We’ll also include some examples of effective hypotheses, and what pitfalls to avoid.

What is a Hypothesis in Research?

Simply put, a hypothesis is a research question that also includes the predicted or expected result of the research. Without a hypothesis, there can be no basis for a scientific or research experiment. As such, it is critical that you carefully construct your hypothesis by being deliberate and thorough, even before you set pen to paper. Unless your hypothesis is clearly and carefully constructed, any flaw can have an adverse, and even grave, effect on the quality of your experiment and its subsequent results.

Research Question vs Hypothesis

It’s easy to confuse research questions with hypotheses, and vice versa. While they’re both critical to the Scientific Method, they have very specific differences. Primarily, a research question, just like a hypothesis, is focused and concise. But a hypothesis includes a prediction based on the proposed research, and is designed to forecast the relationship of and between two (or more) variables. Research questions are open-ended, and invite debate and discussion, while hypotheses are closed, e.g. “The relationship between A and B will be C.”

A hypothesis is generally used if your research topic is fairly well established, and you are relatively certain about the relationship between the variables that will be presented in your research. Since a hypothesis is ideally suited for experimental studies, it will, by its very existence, affect the design of your experiment. The research question is typically used for new topics that have not yet been researched extensively. Here, the relationship between different variables is less known. There is no prediction made, but there may be variables explored. The research question can be casual in nature, simply trying to understand if a relationship even exists, descriptive or comparative.

How to Write Hypothesis in Research

Writing an effective hypothesis starts before you even begin to type. Like any task, preparation is key, so you start first by conducting research yourself, and reading all you can about the topic that you plan to research. From there, you’ll gain the knowledge you need to understand where your focus within the topic will lie.

Remember that a hypothesis is a prediction of the relationship that exists between two or more variables. Your job is to write a hypothesis, and design the research, to “prove” whether or not your prediction is correct. A common pitfall is to use judgments that are subjective and inappropriate for the construction of a hypothesis. It’s important to keep the focus and language of your hypothesis objective.

An effective hypothesis in research is clearly and concisely written, and any terms or definitions clarified and defined. Specific language must also be used to avoid any generalities or assumptions.

Use the following points as a checklist to evaluate the effectiveness of your research hypothesis:

- Predicts the relationship and outcome

- Simple and concise – avoid wordiness

- Clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Observable and testable results

- Relevant and specific to the research question or problem

Research Hypothesis Example

Perhaps the best way to evaluate whether or not your hypothesis is effective is to compare it to those of your colleagues in the field. There is no need to reinvent the wheel when it comes to writing a powerful research hypothesis. As you’re reading and preparing your hypothesis, you’ll also read other hypotheses. These can help guide you on what works, and what doesn’t, when it comes to writing a strong research hypothesis.

Here are a few generic examples to get you started.

Eating an apple each day, after the age of 60, will result in a reduction of frequency of physician visits.

Budget airlines are more likely to receive more customer complaints. A budget airline is defined as an airline that offers lower fares and fewer amenities than a traditional full-service airline. (Note that the term “budget airline” is included in the hypothesis.

Workplaces that offer flexible working hours report higher levels of employee job satisfaction than workplaces with fixed hours.

Each of the above examples are specific, observable and measurable, and the statement of prediction can be verified or shown to be false by utilizing standard experimental practices. It should be noted, however, that often your hypothesis will change as your research progresses.

Language Editing Plus

Elsevier’s Language Editing Plus service can help ensure that your research hypothesis is well-designed, and articulates your research and conclusions. Our most comprehensive editing package, you can count on a thorough language review by native-English speakers who are PhDs or PhD candidates. We’ll check for effective logic and flow of your manuscript, as well as document formatting for your chosen journal, reference checks, and much more.

- Research Process

Systematic Literature Review or Literature Review?

What is a Problem Statement? [with examples]

You may also like.

Make Hook, Line, and Sinker: The Art of Crafting Engaging Introductions

Can Describing Study Limitations Improve the Quality of Your Paper?

A Guide to Crafting Shorter, Impactful Sentences in Academic Writing

6 Steps to Write an Excellent Discussion in Your Manuscript

How to Write Clear and Crisp Civil Engineering Papers? Here are 5 Key Tips to Consider

The Clear Path to An Impactful Paper: ②

The Essentials of Writing to Communicate Research in Medicine

Changing Lines: Sentence Patterns in Academic Writing

Input your search keywords and press Enter.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How to Write an Introduction for a Psychology Paper

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Emily is a board-certified science editor who has worked with top digital publishing brands like Voices for Biodiversity, Study.com, GoodTherapy, Vox, and Verywell.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/Emily-Swaim-1000-0f3197de18f74329aeffb690a177160c.jpg)

- Writing Tips

If you are writing a psychology paper, it is essential to kick things off with a strong introduction. The introduction to a psychology research paper helps your readers understand why the topic is important and what they need to know before they delve deeper.

Your goal in this section is to introduce the topic to the reader, provide an overview of previous research on the topic, and identify your own hypothesis .

At a Glance

Writing a great introduction can be a great foundation for the rest of your psychology paper. To create a strong intro:

- Research your topic

- Outline your paper

- Introduce your topic

- Summarize the previous research

- Present your hypothesis or main argument

Before You Write an Introduction

There are some important steps you need to take before you even begin writing your introduction. To know what to write, you need to collect important background information and create a detailed plan.

Research Your Topic

Search a journal database, PsychInfo or ERIC, to find articles on your subject. Once you have located an article, look at the reference section to locate other studies cited in the article. As you take notes from these articles, be sure to write down where you found the information.

A simple note detailing the author's name, journal, and date of publication can help you keep track of sources and avoid plagiarism.

Create a Detailed Outline

This is often one of the most boring and onerous steps, so students tend to skip outlining and go straight to writing. Creating an outline might seem tedious, but it can be an enormous time-saver down the road and will make the writing process much easier.

Start by looking over the notes you made during the research process and consider how you want to present all of your ideas and research.

Introduce the Topic

Once you are ready to write your introduction, your first task is to provide a brief description of the research question. What is the experiment or study attempting to demonstrate? What phenomena are you studying? Provide a brief history of your topic and explain how it relates to your current research.

As you are introducing your topic, consider what makes it important. Why should it matter to your reader? The goal of your introduction is not only to let your reader know what your paper is about, but also to justify why it is important for them to learn more.

If your paper tackles a controversial subject and is focused on resolving the issue, it is important to summarize both sides of the controversy in a fair and impartial way. Consider how your paper fits in with the relevant research on the topic.

The introduction of a research paper is designed to grab interest. It should present a compelling look at the research that already exists and explain to readers what questions your own paper will address.

Summarize Previous Research

The second task of your introduction is to provide a well-rounded summary of previous research that is relevant to your topic. So, before you begin to write this summary, it is important to research your topic thoroughly.

Finding appropriate sources amid thousands of journal articles can be a daunting task, but there are several steps you can take to simplify your research. If you have completed the initial steps of researching and keeping detailed notes, writing your introduction will be much easier.

It is essential to give the reader a good overview of the historical context of the issue you are writing about, but do not feel like you must provide an exhaustive review of the subject. Focus on hitting the main points, and try to include the most relevant studies.

You might describe previous research findings and then explain how the current study differs or expands upon earlier research.

Provide Your Hypothesis

Once you have summarized the previous research, explain areas where the research is lacking or potentially flawed. What is missing from previous studies on your topic? What research questions have yet to be answered? Your hypothesis should lead to these questions.

At the end of your introduction, offer your hypothesis and describe what you expected to find in your experiment or study.

The introduction should be relatively brief. You want to give your readers an overview of a topic, explain why you are addressing it, and provide your arguments.

Tips for Writing Your Psychology Paper Intro

- Use 3x5 inch note cards to write down notes and sources.

- Look in professional psychology journals for examples of introductions.

- Remember to cite your sources.

- Maintain a working bibliography with all of the sources you might use in your final paper. This will make it much easier to prepare your reference section later on.

- Use a copy of the APA style manual to ensure that your introduction and references are in proper APA format .

What This Means For You

Before you delve into the main body of your paper, you need to give your readers some background and present your main argument in the introduction of you paper. You can do this by first explaining what your topic is about, summarizing past research, and then providing your thesis.

Armağan A. How to write an introduction section of a scientific article ? Turk J Urol . 2013;39(Suppl 1):8-9. doi:10.5152/tud.2013.046

Fried T, Foltz C, Lendner M, Vaccaro AR. How to write an effective introduction . Clin Spine Surg . 2019;32(3):111-112. doi:10.1097/BSD.0000000000000714

Jawaid SA, Jawaid M. How to write introduction and discussion . Saudi J Anaesth . 2019;13(Suppl 1):S18-S19. doi:10.4103/sja.SJA_584_18

American Psychological Association. Information Recommended for Inclusion in Manuscripts That Report New Data Collections Regardless of Research Design . Published 2020.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

How to Write a Research Hypothesis: Good & Bad Examples

What is a research hypothesis?

A research hypothesis is an attempt at explaining a phenomenon or the relationships between phenomena/variables in the real world. Hypotheses are sometimes called “educated guesses”, but they are in fact (or let’s say they should be) based on previous observations, existing theories, scientific evidence, and logic. A research hypothesis is also not a prediction—rather, predictions are ( should be) based on clearly formulated hypotheses. For example, “We tested the hypothesis that KLF2 knockout mice would show deficiencies in heart development” is an assumption or prediction, not a hypothesis.

The research hypothesis at the basis of this prediction is “the product of the KLF2 gene is involved in the development of the cardiovascular system in mice”—and this hypothesis is probably (hopefully) based on a clear observation, such as that mice with low levels of Kruppel-like factor 2 (which KLF2 codes for) seem to have heart problems. From this hypothesis, you can derive the idea that a mouse in which this particular gene does not function cannot develop a normal cardiovascular system, and then make the prediction that we started with.

What is the difference between a hypothesis and a prediction?

You might think that these are very subtle differences, and you will certainly come across many publications that do not contain an actual hypothesis or do not make these distinctions correctly. But considering that the formulation and testing of hypotheses is an integral part of the scientific method, it is good to be aware of the concepts underlying this approach. The two hallmarks of a scientific hypothesis are falsifiability (an evaluation standard that was introduced by the philosopher of science Karl Popper in 1934) and testability —if you cannot use experiments or data to decide whether an idea is true or false, then it is not a hypothesis (or at least a very bad one).

So, in a nutshell, you (1) look at existing evidence/theories, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction that allows you to (4) design an experiment or data analysis to test it, and (5) come to a conclusion. Of course, not all studies have hypotheses (there is also exploratory or hypothesis-generating research), and you do not necessarily have to state your hypothesis as such in your paper.

But for the sake of understanding the principles of the scientific method, let’s first take a closer look at the different types of hypotheses that research articles refer to and then give you a step-by-step guide for how to formulate a strong hypothesis for your own paper.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Hypotheses can be simple , which means they describe the relationship between one single independent variable (the one you observe variations in or plan to manipulate) and one single dependent variable (the one you expect to be affected by the variations/manipulation). If there are more variables on either side, you are dealing with a complex hypothesis. You can also distinguish hypotheses according to the kind of relationship between the variables you are interested in (e.g., causal or associative ). But apart from these variations, we are usually interested in what is called the “alternative hypothesis” and, in contrast to that, the “null hypothesis”. If you think these two should be listed the other way round, then you are right, logically speaking—the alternative should surely come second. However, since this is the hypothesis we (as researchers) are usually interested in, let’s start from there.

Alternative Hypothesis

If you predict a relationship between two variables in your study, then the research hypothesis that you formulate to describe that relationship is your alternative hypothesis (usually H1 in statistical terms). The goal of your hypothesis testing is thus to demonstrate that there is sufficient evidence that supports the alternative hypothesis, rather than evidence for the possibility that there is no such relationship. The alternative hypothesis is usually the research hypothesis of a study and is based on the literature, previous observations, and widely known theories.

Null Hypothesis

The hypothesis that describes the other possible outcome, that is, that your variables are not related, is the null hypothesis ( H0 ). Based on your findings, you choose between the two hypotheses—usually that means that if your prediction was correct, you reject the null hypothesis and accept the alternative. Make sure, however, that you are not getting lost at this step of the thinking process: If your prediction is that there will be no difference or change, then you are trying to find support for the null hypothesis and reject H1.

Directional Hypothesis

While the null hypothesis is obviously “static”, the alternative hypothesis can specify a direction for the observed relationship between variables—for example, that mice with higher expression levels of a certain protein are more active than those with lower levels. This is then called a one-tailed hypothesis.

Another example for a directional one-tailed alternative hypothesis would be that

H1: Attending private classes before important exams has a positive effect on performance.

Your null hypothesis would then be that

H0: Attending private classes before important exams has no/a negative effect on performance.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

A nondirectional hypothesis does not specify the direction of the potentially observed effect, only that there is a relationship between the studied variables—this is called a two-tailed hypothesis. For instance, if you are studying a new drug that has shown some effects on pathways involved in a certain condition (e.g., anxiety) in vitro in the lab, but you can’t say for sure whether it will have the same effects in an animal model or maybe induce other/side effects that you can’t predict and potentially increase anxiety levels instead, you could state the two hypotheses like this:

H1: The only lab-tested drug (somehow) affects anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

You then test this nondirectional alternative hypothesis against the null hypothesis:

H0: The only lab-tested drug has no effect on anxiety levels in an anxiety mouse model.

How to Write a Hypothesis for a Research Paper

Now that we understand the important distinctions between different kinds of research hypotheses, let’s look at a simple process of how to write a hypothesis.

Writing a Hypothesis Step:1

Ask a question, based on earlier research. Research always starts with a question, but one that takes into account what is already known about a topic or phenomenon. For example, if you are interested in whether people who have pets are happier than those who don’t, do a literature search and find out what has already been demonstrated. You will probably realize that yes, there is quite a bit of research that shows a relationship between happiness and owning a pet—and even studies that show that owning a dog is more beneficial than owning a cat ! Let’s say you are so intrigued by this finding that you wonder:

What is it that makes dog owners even happier than cat owners?

Let’s move on to Step 2 and find an answer to that question.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 2:

Formulate a strong hypothesis by answering your own question. Again, you don’t want to make things up, take unicorns into account, or repeat/ignore what has already been done. Looking at the dog-vs-cat papers your literature search returned, you see that most studies are based on self-report questionnaires on personality traits, mental health, and life satisfaction. What you don’t find is any data on actual (mental or physical) health measures, and no experiments. You therefore decide to make a bold claim come up with the carefully thought-through hypothesis that it’s maybe the lifestyle of the dog owners, which includes walking their dog several times per day, engaging in fun and healthy activities such as agility competitions, and taking them on trips, that gives them that extra boost in happiness. You could therefore answer your question in the following way:

Dog owners are happier than cat owners because of the dog-related activities they engage in.

Now you have to verify that your hypothesis fulfills the two requirements we introduced at the beginning of this resource article: falsifiability and testability . If it can’t be wrong and can’t be tested, it’s not a hypothesis. We are lucky, however, because yes, we can test whether owning a dog but not engaging in any of those activities leads to lower levels of happiness or well-being than owning a dog and playing and running around with them or taking them on trips.

Writing a Hypothesis Step 3:

Make your predictions and define your variables. We have verified that we can test our hypothesis, but now we have to define all the relevant variables, design our experiment or data analysis, and make precise predictions. You could, for example, decide to study dog owners (not surprising at this point), let them fill in questionnaires about their lifestyle as well as their life satisfaction (as other studies did), and then compare two groups of active and inactive dog owners. Alternatively, if you want to go beyond the data that earlier studies produced and analyzed and directly manipulate the activity level of your dog owners to study the effect of that manipulation, you could invite them to your lab, select groups of participants with similar lifestyles, make them change their lifestyle (e.g., couch potato dog owners start agility classes, very active ones have to refrain from any fun activities for a certain period of time) and assess their happiness levels before and after the intervention. In both cases, your independent variable would be “ level of engagement in fun activities with dog” and your dependent variable would be happiness or well-being .

Examples of a Good and Bad Hypothesis

Let’s look at a few examples of good and bad hypotheses to get you started.

Good Hypothesis Examples

Bad hypothesis examples, tips for writing a research hypothesis.

If you understood the distinction between a hypothesis and a prediction we made at the beginning of this article, then you will have no problem formulating your hypotheses and predictions correctly. To refresh your memory: We have to (1) look at existing evidence, (2) come up with a hypothesis, (3) make a prediction, and (4) design an experiment. For example, you could summarize your dog/happiness study like this:

(1) While research suggests that dog owners are happier than cat owners, there are no reports on what factors drive this difference. (2) We hypothesized that it is the fun activities that many dog owners (but very few cat owners) engage in with their pets that increases their happiness levels. (3) We thus predicted that preventing very active dog owners from engaging in such activities for some time and making very inactive dog owners take up such activities would lead to an increase and decrease in their overall self-ratings of happiness, respectively. (4) To test this, we invited dog owners into our lab, assessed their mental and emotional well-being through questionnaires, and then assigned them to an “active” and an “inactive” group, depending on…

Note that you use “we hypothesize” only for your hypothesis, not for your experimental prediction, and “would” or “if – then” only for your prediction, not your hypothesis. A hypothesis that states that something “would” affect something else sounds as if you don’t have enough confidence to make a clear statement—in which case you can’t expect your readers to believe in your research either. Write in the present tense, don’t use modal verbs that express varying degrees of certainty (such as may, might, or could ), and remember that you are not drawing a conclusion while trying not to exaggerate but making a clear statement that you then, in a way, try to disprove . And if that happens, that is not something to fear but an important part of the scientific process.

Similarly, don’t use “we hypothesize” when you explain the implications of your research or make predictions in the conclusion section of your manuscript, since these are clearly not hypotheses in the true sense of the word. As we said earlier, you will find that many authors of academic articles do not seem to care too much about these rather subtle distinctions, but thinking very clearly about your own research will not only help you write better but also ensure that even that infamous Reviewer 2 will find fewer reasons to nitpick about your manuscript.

Perfect Your Manuscript With Professional Editing

Now that you know how to write a strong research hypothesis for your research paper, you might be interested in our free AI proofreader , Wordvice AI, which finds and fixes errors in grammar, punctuation, and word choice in academic texts. Or if you are interested in human proofreading , check out our English editing services , including research paper editing and manuscript editing .

On the Wordvice academic resources website , you can also find many more articles and other resources that can help you with writing the other parts of your research paper , with making a research paper outline before you put everything together, or with writing an effective cover letter once you are ready to submit.

HOW TO: Use Articles for Research: Introduction: Hypothesis/Thesis

- What's a Scholarly Journal?

- Reading the Citation

- Authors' Credentials

- Introduction: Hypothesis/Thesis

- Literature Review

- Research Method

- Results/Data

- Discussion/Conclusions

Hypothesis or Thesis

The first few paragraphs of a journal article serve to introduce the topic, to provide the author's hypothesis or thesis, and to indicate why the research was done. A thesis or hypothesis is not always clearly labled; you may need to read through the introductory paragraphs to determine what the authors are proposing.

- << Previous: Abstract

- Next: Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jan 29, 2024 3:35 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cayuga-cc.edu/1ST-PRIORITY/articles

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Dissertation

How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction

Published on 9 September 2022 by Tegan George and Shona McCombes.

The introduction is the first section of your thesis or dissertation , appearing right after the table of contents . Your introduction draws your reader in, setting the stage for your research with a clear focus, purpose, and direction.

Your introduction should include:

- Your topic, in context: what does your reader need to know to understand your thesis dissertation?

- Your focus and scope: what specific aspect of the topic will you address?

- The relevance of your research: how does your work fit into existing studies on your topic?

- Your questions and objectives: what does your research aim to find out, and how?

- An overview of your structure: what does each section contribute to the overall aim?

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Be assured that you'll submit flawless writing. Upload your document to correct all your mistakes.

Table of contents

How to start your introduction, topic and context, focus and scope, relevance and importance, questions and objectives, overview of the structure, thesis introduction example, introduction checklist, frequently asked questions about introductions.

Although your introduction kicks off your dissertation, it doesn’t have to be the first thing you write – in fact, it’s often one of the very last parts to be completed (just before your abstract ).

It’s a good idea to write a rough draft of your introduction as you begin your research, to help guide you. If you wrote a research proposal , consider using this as a template, as it contains many of the same elements. However, be sure to revise your introduction throughout the writing process, making sure it matches the content of your ensuing sections.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Correct my document today

Begin by introducing your research topic and giving any necessary background information. It’s important to contextualise your research and generate interest. Aim to show why your topic is timely or important. You may want to mention a relevant news item, academic debate, or practical problem.

After a brief introduction to your general area of interest, narrow your focus and define the scope of your research.

You can narrow this down in many ways, such as by:

- Geographical area

- Time period

- Demographics or communities

- Themes or aspects of the topic

It’s essential to share your motivation for doing this research, as well as how it relates to existing work on your topic. Further, you should also mention what new insights you expect it will contribute.

Start by giving a brief overview of the current state of research. You should definitely cite the most relevant literature, but remember that you will conduct a more in-depth survey of relevant sources in the literature review section, so there’s no need to go too in-depth in the introduction.

Depending on your field, the importance of your research might focus on its practical application (e.g., in policy or management) or on advancing scholarly understanding of the topic (e.g., by developing theories or adding new empirical data). In many cases, it will do both.

Ultimately, your introduction should explain how your thesis or dissertation:

- Helps solve a practical or theoretical problem

- Addresses a gap in the literature

- Builds on existing research

- Proposes a new understanding of your topic

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Perhaps the most important part of your introduction is your questions and objectives, as it sets up the expectations for the rest of your thesis or dissertation. How you formulate your research questions and research objectives will depend on your discipline, topic, and focus, but you should always clearly state the central aim of your research.

If your research aims to test hypotheses , you can formulate them here. Your introduction is also a good place for a conceptual framework that suggests relationships between variables .

- Conduct surveys to collect data on students’ levels of knowledge, understanding, and positive/negative perceptions of government policy.

- Determine whether attitudes to climate policy are associated with variables such as age, gender, region, and social class.

- Conduct interviews to gain qualitative insights into students’ perspectives and actions in relation to climate policy.

To help guide your reader, end your introduction with an outline of the structure of the thesis or dissertation to follow. Share a brief summary of each chapter, clearly showing how each contributes to your central aims. However, be careful to keep this overview concise: 1-2 sentences should be enough.

I. Introduction

Human language consists of a set of vowels and consonants which are combined to form words. During the speech production process, thoughts are converted into spoken utterances to convey a message. The appropriate words and their meanings are selected in the mental lexicon (Dell & Burger, 1997). This pre-verbal message is then grammatically coded, during which a syntactic representation of the utterance is built.

Speech, language, and voice disorders affect the vocal cords, nerves, muscles, and brain structures, which result in a distorted language reception or speech production (Sataloff & Hawkshaw, 2014). The symptoms vary from adding superfluous words and taking pauses to hoarseness of the voice, depending on the type of disorder (Dodd, 2005). However, distortions of the speech may also occur as a result of a disease that seems unrelated to speech, such as multiple sclerosis or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

This study aims to determine which acoustic parameters are suitable for the automatic detection of exacerbations in patients suffering from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) by investigating which aspects of speech differ between COPD patients and healthy speakers and which aspects differ between COPD patients in exacerbation and stable COPD patients.

Checklist: Introduction

I have introduced my research topic in an engaging way.

I have provided necessary context to help the reader understand my topic.

I have clearly specified the focus of my research.

I have shown the relevance and importance of the dissertation topic .

I have clearly stated the problem or question that my research addresses.

I have outlined the specific objectives of the research .

I have provided an overview of the dissertation’s structure .

You've written a strong introduction for your thesis or dissertation. Use the other checklists to continue improving your dissertation.

The introduction of a research paper includes several key elements:

- A hook to catch the reader’s interest

- Relevant background on the topic

- Details of your research problem

- A thesis statement or research question

- Sometimes an outline of the paper

Don’t feel that you have to write the introduction first. The introduction is often one of the last parts of the research paper you’ll write, along with the conclusion.

This is because it can be easier to introduce your paper once you’ve already written the body ; you may not have the clearest idea of your arguments until you’ve written them, and things can change during the writing process .

Research objectives describe what you intend your research project to accomplish.

They summarise the approach and purpose of the project and help to focus your research.

Your objectives should appear in the introduction of your research paper , at the end of your problem statement .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

George, T. & McCombes, S. (2022, September 09). How to Write a Thesis or Dissertation Introduction. Scribbr. Retrieved 14 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/thesis-dissertation/introduction/

Is this article helpful?

Tegan George

Other students also liked, what is a dissertation | 5 essential questions to get started, how to write an abstract | steps & examples, how to write a thesis or dissertation conclusion.

How to Develop a Good Research Hypothesis

The story of a research study begins by asking a question. Researchers all around the globe are asking curious questions and formulating research hypothesis. However, whether the research study provides an effective conclusion depends on how well one develops a good research hypothesis. Research hypothesis examples could help researchers get an idea as to how to write a good research hypothesis.

This blog will help you understand what is a research hypothesis, its characteristics and, how to formulate a research hypothesis

Table of Contents

What is Hypothesis?

Hypothesis is an assumption or an idea proposed for the sake of argument so that it can be tested. It is a precise, testable statement of what the researchers predict will be outcome of the study. Hypothesis usually involves proposing a relationship between two variables: the independent variable (what the researchers change) and the dependent variable (what the research measures).

What is a Research Hypothesis?

Research hypothesis is a statement that introduces a research question and proposes an expected result. It is an integral part of the scientific method that forms the basis of scientific experiments. Therefore, you need to be careful and thorough when building your research hypothesis. A minor flaw in the construction of your hypothesis could have an adverse effect on your experiment. In research, there is a convention that the hypothesis is written in two forms, the null hypothesis, and the alternative hypothesis (called the experimental hypothesis when the method of investigation is an experiment).

Characteristics of a Good Research Hypothesis

As the hypothesis is specific, there is a testable prediction about what you expect to happen in a study. You may consider drawing hypothesis from previously published research based on the theory.

A good research hypothesis involves more effort than just a guess. In particular, your hypothesis may begin with a question that could be further explored through background research.

To help you formulate a promising research hypothesis, you should ask yourself the following questions:

- Is the language clear and focused?

- What is the relationship between your hypothesis and your research topic?

- Is your hypothesis testable? If yes, then how?

- What are the possible explanations that you might want to explore?

- Does your hypothesis include both an independent and dependent variable?

- Can you manipulate your variables without hampering the ethical standards?

- Does your research predict the relationship and outcome?

- Is your research simple and concise (avoids wordiness)?

- Is it clear with no ambiguity or assumptions about the readers’ knowledge

- Is your research observable and testable results?

- Is it relevant and specific to the research question or problem?

The questions listed above can be used as a checklist to make sure your hypothesis is based on a solid foundation. Furthermore, it can help you identify weaknesses in your hypothesis and revise it if necessary.

Source: Educational Hub

How to formulate a research hypothesis.

A testable hypothesis is not a simple statement. It is rather an intricate statement that needs to offer a clear introduction to a scientific experiment, its intentions, and the possible outcomes. However, there are some important things to consider when building a compelling hypothesis.

1. State the problem that you are trying to solve.

Make sure that the hypothesis clearly defines the topic and the focus of the experiment.

2. Try to write the hypothesis as an if-then statement.

Follow this template: If a specific action is taken, then a certain outcome is expected.

3. Define the variables

Independent variables are the ones that are manipulated, controlled, or changed. Independent variables are isolated from other factors of the study.

Dependent variables , as the name suggests are dependent on other factors of the study. They are influenced by the change in independent variable.

4. Scrutinize the hypothesis

Evaluate assumptions, predictions, and evidence rigorously to refine your understanding.

Types of Research Hypothesis

The types of research hypothesis are stated below:

1. Simple Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between a single dependent variable and a single independent variable.

2. Complex Hypothesis

It predicts the relationship between two or more independent and dependent variables.

3. Directional Hypothesis

It specifies the expected direction to be followed to determine the relationship between variables and is derived from theory. Furthermore, it implies the researcher’s intellectual commitment to a particular outcome.

4. Non-directional Hypothesis

It does not predict the exact direction or nature of the relationship between the two variables. The non-directional hypothesis is used when there is no theory involved or when findings contradict previous research.

5. Associative and Causal Hypothesis

The associative hypothesis defines interdependency between variables. A change in one variable results in the change of the other variable. On the other hand, the causal hypothesis proposes an effect on the dependent due to manipulation of the independent variable.

6. Null Hypothesis

Null hypothesis states a negative statement to support the researcher’s findings that there is no relationship between two variables. There will be no changes in the dependent variable due the manipulation of the independent variable. Furthermore, it states results are due to chance and are not significant in terms of supporting the idea being investigated.

7. Alternative Hypothesis

It states that there is a relationship between the two variables of the study and that the results are significant to the research topic. An experimental hypothesis predicts what changes will take place in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated. Also, it states that the results are not due to chance and that they are significant in terms of supporting the theory being investigated.