Citing sources: Overview

- Citation style guides

Manage your references

Use these tools to help you organize and cite your references:

- Citation Management and Writing Tools

If you have questions after consulting this guide about how to cite, please contact your advisor/professor or the writing and communication center .

Why citing is important

It's important to cite sources you used in your research for several reasons:

- To show your reader you've done proper research by listing sources you used to get your information

- To be a responsible scholar by giving credit to other researchers and acknowledging their ideas

- To avoid plagiarism by quoting words and ideas used by other authors

- To allow your reader to track down the sources you used by citing them accurately in your paper by way of footnotes, a bibliography or reference list

About citations

Citing a source means that you show, within the body of your text, that you took words, ideas, figures, images, etc. from another place.

Citations are a short way to uniquely identify a published work (e.g. book, article, chapter, web site). They are found in bibliographies and reference lists and are also collected in article and book databases.

Citations consist of standard elements, and contain all the information necessary to identify and track down publications, including:

- author name(s)

- titles of books, articles, and journals

- date of publication

- page numbers

- volume and issue numbers (for articles)

Citations may look different, depending on what is being cited and which style was used to create them. Choose an appropriate style guide for your needs. Here is an example of an article citation using four different citation styles. Notice the common elements as mentioned above:

Author - R. Langer

Article Title - New Methods of Drug Delivery

Source Title - Science

Volume and issue - Vol 249, issue 4976

Publication Date - 1990

Page numbers - 1527-1533

American Chemical Society (ACS) style:

Langer, R. New Methods of Drug Delivery. Science 1990 , 249 , 1527-1533.

IEEE Style:

R. Langer, " New Methods of Drug Delivery," Science , vol. 249 , pp. 1527-1533 , SEP 28, 1990 .

American Psychological Association (APA) style:

Langer, R. (1990) . New methods of drug delivery. Science , 249 (4976), 1527-1533.

Modern Language Association (MLA) style:

Langer, R. " New Methods of Drug Delivery." Science 249.4976 (1990) : 1527-33.

What to cite

You must cite:

- Facts, figures, ideas, or other information that is not common knowledge

Publications that must be cited include: books, book chapters, articles, web pages, theses, etc.

Another person's exact words should be quoted and cited to show proper credit

When in doubt, be safe and cite your source!

Avoiding plagiarism

Plagiarism occurs when you borrow another's words (or ideas) and do not acknowledge that you have done so. In this culture, we consider our words and ideas intellectual property; like a car or any other possession, we believe our words belong to us and cannot be used without our permission.

Plagiarism is a very serious offense. If it is found that you have plagiarized -- deliberately or inadvertently -- you may face serious consequences. In some instances, plagiarism has meant that students have had to leave the institutions where they were studying.

The best way to avoid plagiarism is to cite your sources - both within the body of your paper and in a bibliography of sources you used at the end of your paper.

Some useful links about plagiarism:

- MIT Academic Integrity Overview on citing sources and avoiding plagiarism at MIT.

- Avoiding Plagiarism From the MIT Writing and Communication Center.

- Plagiarism: What It is and How to Recognize and Avoid It From Indiana University's Writing Tutorial Services.

- Plagiarism- Overview A resource from Purdue University.

- Next: Citation style guides >>

- Last Updated: Jan 16, 2024 7:02 AM

- URL: https://libguides.mit.edu/citing

University Library

Start your research.

- Research Process

- Find Background Info

- Find Sources through the Library

- Evaluate Your Info

- Cite Your Sources

- Evaluate, Write & Cite

- is the right thing to do to give credit to those who had the idea

- shows that you have read and understand what experts have had to say about your topic

- helps people find the sources that you used in case they want to read more about the topic

- provides evidence for your arguments

- is professional and standard practice for students and scholars

What is a Citation?

A citation identifies for the reader the original source for an idea, information, or image that is referred to in a work.

- In the body of a paper, the in-text citation acknowledges the source of information used.

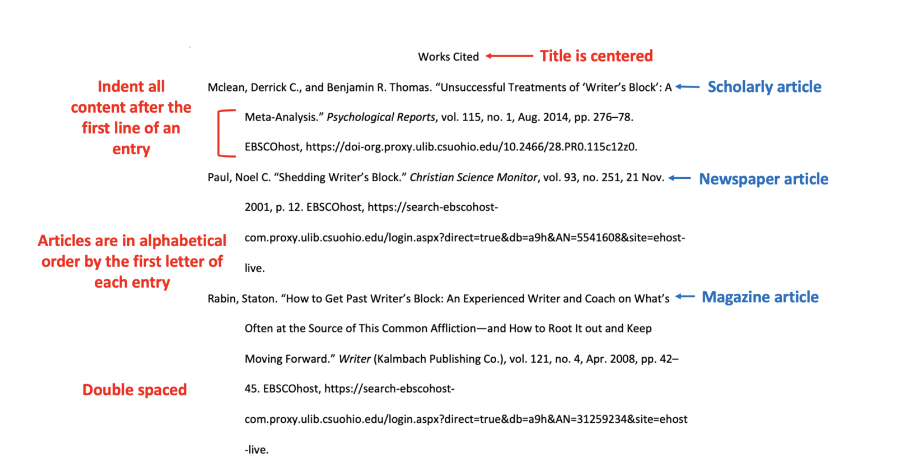

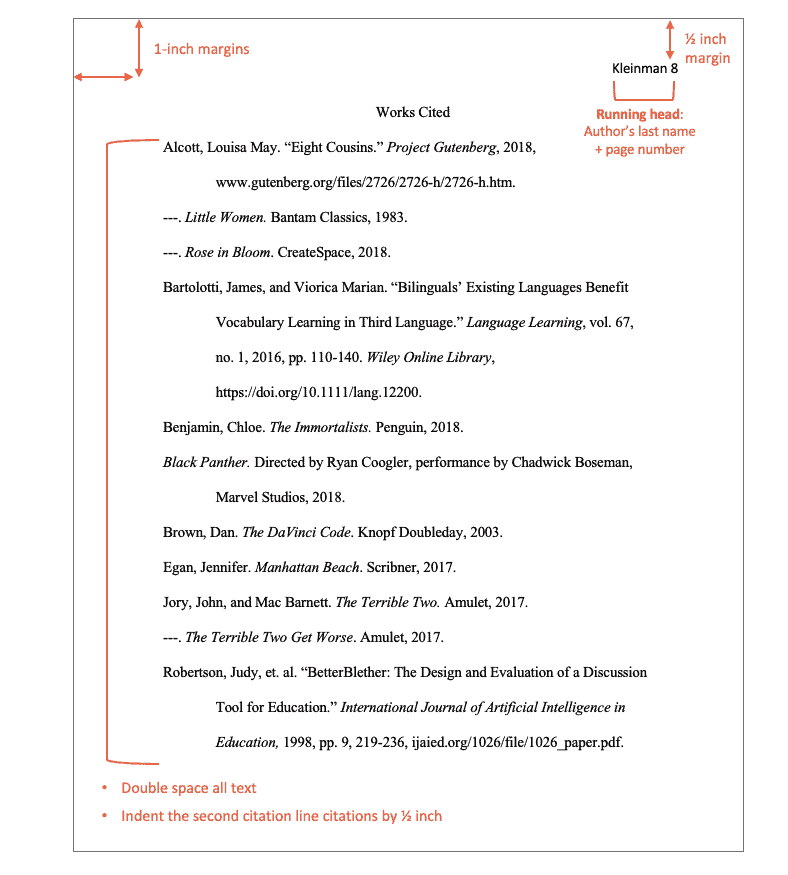

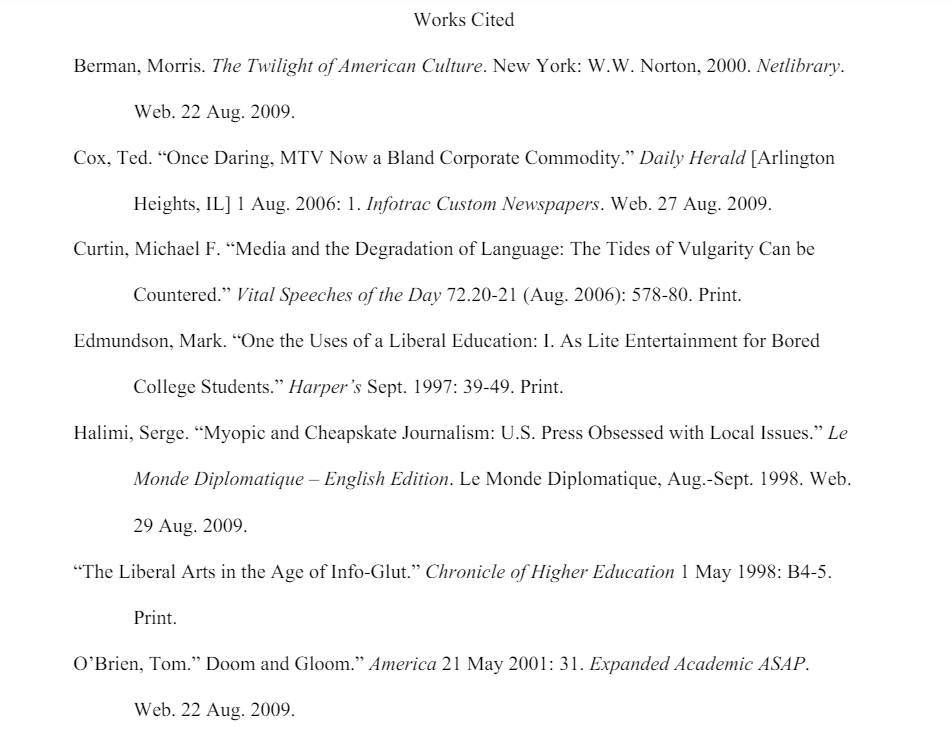

- At the end of a paper, the citations are compiled on a References or Works Cited list. A basic citation includes the author, title, and publication information of the source.

From: Lemieux Library, University of Seattle

Why Should You Cite?

Quoting Are you quoting two or more consecutive words from a source? Then the original source should be cited and the words or phrase placed in quotes.

Paraphrasing If an idea or information comes from another source, even if you put it in your own words , you still need to credit the source. General vs. Unfamiliar Knowledge You do not need to cite material which is accepted common knowledge. If in doubt whether your information is common knowledge or not, cite it. Formats We usually think of books and articles. However, if you use material from web sites, films, music, graphs, tables, etc. you'll also need to cite these as well.

Plagiarism is presenting the words or ideas of someone else as your own without proper acknowledgment of the source. When you work on a research paper and use supporting material from works by others, it's okay to quote people and use their ideas, but you do need to correctly credit them. Even when you summarize or paraphrase information found in books, articles, or Web pages, you must acknowledge the original author.

Citation Style Help

Helpful links:

- MLA , Works Cited : A Quick Guide (a template of core elements)

- CSE (Council of Science Editors)

For additional writing resources specific to styles listed here visit the Purdue OWL Writing Lab

Citation and Bibliography Resources

- How to Write an Annotated Bibliography

- << Previous: Evaluate Your Info

- Next: Evaluate, Write & Cite >>

Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License except where otherwise noted.

Land Acknowledgement

The land on which we gather is the unceded territory of the Awaswas-speaking Uypi Tribe. The Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, comprised of the descendants of indigenous people taken to missions Santa Cruz and San Juan Bautista during Spanish colonization of the Central Coast, is today working hard to restore traditional stewardship practices on these lands and heal from historical trauma.

The land acknowledgement used at UC Santa Cruz was developed in partnership with the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band Chairman and the Amah Mutsun Relearning Program at the UCSC Arboretum .

- MJC Library & Learning Center

- Research Guides

Format Your Paper & Cite Your Sources

- APA Style, 7th Edition

- Citing Sources

- Avoid Plagiarism

- MLA Style (8th/9th ed.)

APA Tutorial

Formatting your paper, headings organize your paper (2.27), video tutorials, reference list format (9.43).

- Elements of a Reference

Reference Examples (Chapter 10)

Dois and urls (9.34-9.36), in-text citations.

- In-Text Citations Format

- In-Text Citations for Specific Source Types

NoodleTools

- Chicago Style

- Harvard Style

- Other Styles

- Annotated Bibliographies

- How to Create an Attribution

What is APA Style?

APA style was created by social and behavioral scientists to standardize scientific writing. APA style is most often used in:

- psychology,

- social sciences (sociology, business), and

If you're taking courses in any of these areas, be prepared to use APA style.

For in-depth guidance on using this citation style, refer to Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association , 7th ed. We have several copies available at the MJC Library at the call number BF 76.7 .P83 2020 .

APA Style, 7th ed.

In October 2019, the American Psychological Association made radical changes its style, especially with regard to the format and citation rules for students writing academic papers. Use this guide to learn how to format and cite your papers using APA Style, 7th edition.

You can start by viewing the video tutorial .

For help on all aspects of formatting your paper in APA Style, see The Essentials page on the APA Style website.

- sans serif fonts such as 11-point Calibri, 11-point Arial, or 10-point Lucida Sans Unicode, or

- serif fonts such as 12-point Times New Roman, 11-point Georgia, or normal (10-point) Computer Modern (the default font for LaTeX)

- There are exceptions for the title page , tables , figures , footnotes , and displayed equations .

- Margins : Use 1-in. margins on every side of the page.

- Align the text of an APA Style paper to the left margin . Leave the right margin uneven, or “ragged.”

- Do not use full justification for student papers.

- Do not insert hyphens (manual breaks) in words at the end of line. However, it is acceptable if your word-processing program automatically inserts breaks in long hyperlinks (such as in a DOI or URL in a reference list entry).

- Indent the first line of each paragraph of text 0.5 in . from the left margin. Use the tab key or the automatic paragraph-formatting function of your word-processing program to achieve the indentation (the default setting is likely already 0.5 in.). Do not use the space bar to create indentation.

- There are exceptions for the title page , section labels , abstract , block quotations , headings , tables and figures , reference list , and appendices .

Paper Elements

Student papers generally include, at a minimum:

- Title Page (2.3)

- Text (2.11)

- References (2.12)

Student papers may include additional elements such as tables and figures depending on the assignment. So, please check with your teacher!

Student papers generally DO NOT include the following unless your teacher specifically requests it:

- Running head

- Author note

For complete information on the order of pages , see the APA Style website.

Number your pages consecutively starting with page 1. Each section begins on a new page. Put the pages in the following order:

- Page 1: Title page

- Page 2: Abstract (if your teacher requires an abstract)

- Page 3: Text

- References begin on a new page after the last page of text

- Footnotes begin on a new page after the references (if your teacher requires footnotes)

- Tables begin each on a new page after the footnotes (if your teacher requires tables)

- Figures begin on a new page after the tables (if your teacher requires figures)

- Appendices begin on a new page after the tables and/or figures (if your teacher requires appendices)

Sample Papers With Built-In Instructions

To see what your paper should look like, check out these sample papers with built-in instructions.

APA Style uses five (5) levels of headings to help you organize your paper and allow your audience to identify its key points easily. Levels of headings establish the hierarchy of your sections just like you did in your paper outline.

APA tells us to use "only the number of headings necessary to differentiate distinct section in your paper." Therefore, the number of heading levels you create depends on the length and complexity of your paper.

See the chart below for instructions on formatting your headings:

Use Word to Format Your Paper:

Use Google Docs to Format Your Paper:

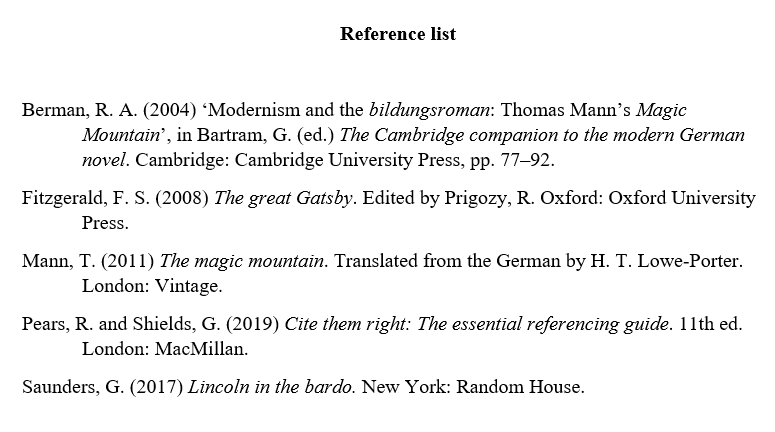

Placement: The reference list appears at the end of the paper, on its own page(s). If your research paper ends on page 8, your References begin on page 9.

Heading: Place the section label References in bold at the top of the page, centered.

Arrangement: Alphabetize entries by author's last name. If source has no named author, alphabetize by the title, ignoring A, An, or The. (9.44-9.48)

Spacing: Like the rest of the APA paper, the reference list is double-spaced throughout. Be sure NOT to add extra spaces between citations.

Indentation: To make citations easier to scan, add a hanging indent of 0.5 in. to any citation that runs more than one line. Use the paragraph-formatting function of your word processing program to create your hanging indent.

See Sample References Page (from APA Sample Student Paper):

Elements of Reference List Entries: (Chapter 9)

References generally have four elements, each of which has a corresponding question for you to answer:

- Author: Who is responsible for this work? (9.7-9.12)

- Date: When was this work published? (9.13-9.17)

- Title: What is this work called? (9.18-9.22)

- Source: Where can I retrieve this work? (9.23-9.37)

By using these four elements and answering these four questions, you should be able to create a citation for any type of source.

For complete information on all of these elements, checkout the APA Style website.

This infographic shows the first page of a journal article. The locations of the reference elements are highlighted with different colors and callouts, and the same colors are used in the reference list entry to show how the entry corresponds to the source.

To create your references, you'll simple look for these elements in your source and put them together in your reference list entry.

American Psychological Association. Example of where to find reference information for a journal article [Infographic]. APA Style Center. https://apastyle.apa.org/style-grammar-guidelines/references/basic-principles

Below you'll find two printable handouts showing APA citation examples. The first is an abbreviated list created by MJC Librarians. The second, which is more comprehensive, is from the APA Style website. Feel free to print these for your convenience or use the links to reference examples below:

- APA Citation Examples Created by MJC Librarians for you.

- Common References Examples (APA Handout) Printable handout from the American Psychological Association.

- Journal Article

- Magazine Article

- Newspaper Article

- Edited Book Chapter

- Webpage on a Website

Classroom or Intranet Sources

- Classroom Course Pack Materials

- How to Cite ChatGPT

- Dictionary Entry

- Government Report

- Legal References (Laws & Cases)

- TED Talk References

- Religious Works

- Open Educational Resources (OER)

- Archival Documents and Collections

You can view the entire Reference Examples website below and view a helpful guide to finding useful APA style topics easily:

- APA Style: Reference Examples

- Navigating the not-so-hidden treasures of the APA Style website

- Missing Reference Information

Sometimes you won't be able to find all the elements required for your reference. In that case, see the instructions in Table 9.1 of the APA style manual in section 9.4 or the APA Style website below:

- Direct Quotation of Material Without Page Numbers

The DOI or URL is the final component of a reference list entry. Because so much scholarship is available and/or retrieved online, most reference list entries end with either a DOI or a URL.

- A DOI is a unique alphanumeric string that identifies content and provides a persistent link to its location on the internet. DOIs can be found in database records and the reference lists of published works.

- A URL specifies the location of digital information on the internet and can be found in the address bar of your internet browser. URLs in references should link directly to the cited work when possible.

When to Include DOIs and URLs:

- Include a DOI for all works that have a DOI, regardless of whether you used the online version or the print version.

- If an online work has both a DOI and a URL, include only the DOI.

- For works without DOIs from websites (not including academic research databases), provide a URL in the reference (as long as the URL will work for readers).

- For works without DOIs from most academic research databases, do not include a URL or database information in the reference because these works are widely available. The reference should be the same as the reference for a print version of the work.

- For works from databases that publish original, proprietary material available only in that database (such as the UpToDate database) or for works of limited circulation in databases (such as monographs in the ERIC database), include the name of the database or archive and the URL of the work. If the URL requires a login or is session-specific (meaning it will not resolve for readers), provide the URL of the database or archive home page or login page instead of the URL for the work. (See APA Section 9.30 for more information).

- If the URL is no longer working or no longer provides readers access to the content you intend to cite, try to find an archived version using the Internet Archive , then use the archived URL. If there is no archived URL, do not use that resource.

Format of DOIs and URLs:

Your DOI should look like this:

https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040251

Follow these guidelines from the APA Style website.

APA Style uses the author–date citation system , in which a brief in-text citation points your reader to the full reference list entry at the end of your paper. The in-text citation appears within the body of the paper and briefly identifies the cited work by its author and date of publication. This method enables your reader to locate the corresponding entry in the alphabetical reference list at the end of your paper.

Each work you cite must appear in the reference list, and each work in the reference list must be cited in the text (or in a table, figure, footnote, or appendix) except for the following (See APA, 8.4):

- Personal communications (8.9)

- General mentions of entire websites, whole periodicals (8.22), and common software and apps (10.10) in the text do not require a citation or reference list entry.

- The source of an epigraph does not usually appear in the reference list (8.35)

- Quotations from your research participants do not need citations or reference list entries (8.36)

- References included in a statistical meta-analysis, which are marked with an asterisk in the reference list, may be cited in the text (or not) at the author’s discretion. This exception is relevant only to authors who are conducting a meta-analysis (9.52).

Formatting Your In-Text Citations

Parenthetical and Narrative Citations: ( See APA Section 8.11)

In APA style you use the author-date citation system for citing references within your paper. You incorporate these references using either a parenthetical or a narrative style.

Parenthetical Citations

- In parenthetical citations, the author name and publication date appear in parentheses, separated by a comma. (Jones, 2018)

- A parenthetical citation can appear within or at the end of a sentence.

- When the parenthetical citation is at the end of the sentence, put the period or other end punctuation after the closing parenthesis.

- If there is no author, use the first few words of the reference list entry, usually the "Title" of the source: ("Autism," 2008) See APA 8.14

- When quoting, always provide the author, year, and specific page citation or paragraph number for nonpaginated materials in the text (Santa Barbara, 2010, p. 243). See APA 8.13

- For most citations, the parenthetical reference is placed BEFORE the punctuation: Magnesium can be effective in treating PMS (Haggerty, 2012).

Narrative Citations

In narrative citations, the author name or title of your source appears within your text and the publication date appears in parentheses immediately after the author name.

- Santa Barbara (2010) noted a decline in the approval of disciplinary spanking of 26 percentage points from 1968 to 1994.

In-Text Citation Checklist

- In-Text Citation Checklist Use this useful checklist from the American Psychological Association to ensure that you've created your in-text citations correctly.

In-Text Citations for Specific Types of Sources

Quotations from Research Participants

Personal Communications

Secondary Sources

Use NoodleTools to Cite Your Sources

NoodleTools can help you create your references and your in-text citations.

- NoodleTools Express No sign in required . When you need one or two quick citations in MLA, APA, or Chicago style, simply generate them in NoodleTools Express then copy and paste what you need into your document. Note: Citations are not saved and cannot be exported to a word processor using NoodleTools Express.

- NoodleTools (Login Full Database) This link opens in a new window Create and organize your research notes, share and collaborate on research projects, compose and error check citations, and complete your list of works cited in MLA, APA, or Chicago style using the full version of NoodleTools. You'll need to Create a Personal ID and password the first time you use NoodleTools.

See How to Use NoodleTools Express to Create a Citation in APA Format

Additional NoodleTools Help

- NoodleTools Help Desk Look up questions and answers on the NoodleTools Web site

- << Previous: MLA Style (8th/9th ed.)

- Next: Chicago Style >>

- Last Updated: May 1, 2024 2:04 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mjc.edu/citeyoursources

Except where otherwise noted, this work is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 and CC BY-NC 4.0 Licenses .

- PRO Courses Guides New Tech Help Pro Expert Videos About wikiHow Pro Upgrade Sign In

- EDIT Edit this Article

- EXPLORE Tech Help Pro About Us Random Article Quizzes Request a New Article Community Dashboard This Or That Game Popular Categories Arts and Entertainment Artwork Books Movies Computers and Electronics Computers Phone Skills Technology Hacks Health Men's Health Mental Health Women's Health Relationships Dating Love Relationship Issues Hobbies and Crafts Crafts Drawing Games Education & Communication Communication Skills Personal Development Studying Personal Care and Style Fashion Hair Care Personal Hygiene Youth Personal Care School Stuff Dating All Categories Arts and Entertainment Finance and Business Home and Garden Relationship Quizzes Cars & Other Vehicles Food and Entertaining Personal Care and Style Sports and Fitness Computers and Electronics Health Pets and Animals Travel Education & Communication Hobbies and Crafts Philosophy and Religion Work World Family Life Holidays and Traditions Relationships Youth

- Browse Articles

- Learn Something New

- Quizzes Hot

- This Or That Game

- Train Your Brain

- Explore More

- Support wikiHow

- About wikiHow

- Log in / Sign up

- Education and Communications

- College University and Postgraduate

- Academic Writing

- Research Papers

How to Cite a Research Paper in APA

Last Updated: October 19, 2022 Fact Checked

This article was co-authored by wikiHow Staff . Our trained team of editors and researchers validate articles for accuracy and comprehensiveness. wikiHow's Content Management Team carefully monitors the work from our editorial staff to ensure that each article is backed by trusted research and meets our high quality standards. There are 12 references cited in this article, which can be found at the bottom of the page. This article has been fact-checked, ensuring the accuracy of any cited facts and confirming the authority of its sources. This article has been viewed 160,493 times. Learn more...

If you’re citing a research article or paper in APA style, you’ll need to use a specific citation format that varies depending on the source. Assess whether your source is an article or report published in an academic journal or book, or whether it is an unpublished research paper, such as a print-only thesis or dissertation. Either way, your in-text citations will need to include information about the author (if available) and the date when your source was published or written.

Sample Citations

Writing an In-Text Citation

- For example, you may write, “Gardener (2008) notes, ‘There are several factors to consider about lobsters’ (p. 199).”

- For example, you may write, “‘There are several factors to consider about lobsters’ (Gardner, 2008, p. 199).” Or, “The paper claims, ‘The fallen angel trope is common in religious and non-religious texts’ (Meek & Hill, 2015, p.13-14).”

- For articles with 3-5 authors, write out the names of all the authors the first time you cite the source. For example: (Hammett, Wooster, Smith, & Charles, 1928). In subsequent citations, write only the first author’s name, followed by et al.: (Hammett et al., 1928).

- If there are 6 or more authors for the paper, include the last name of the first author listed and then write "et al." to indicate that there are more than 5 authors.

- For example, you may write, "'This is a quote' (Minaj et al., 1997, p. 45)."

- For example, you may write, “‘The risk of cervical cancer in women is rising’ (American Cancer Society, 2012, p. 2).”

- For example, you may write, “‘Shakespeare may have been a woman’ (“Radical English Literature,” 2004, p. 45).” Or, “The paper notes, ‘There is a boom in Virgin Mary imagery’ (“Art History in Italy,” 2011, p. 32).”

- For example, you may write, “‘There are several factors to consider about lobsters’ (Gardner, 2008, p. 199).” Or, “The paper claims, ‘The fallen angel trope is common in religious and non-religious texts’ (“Iconography in Italian Frescos,” 2015, p.13-14).”

- For example, you may write, “‘There are several factors to consider about lobsters’ (Gardner, 2008, p. 199).” Or, “The paper claims, ‘The fallen angel trope is common in religious and non-religious texts’ (“Iconography in Italian Frescos,” 2015, p.145-146).”

- For example, you may write, “‘The effects of food deprivation are long-term’ (Mett, 2005, para. 18).”

Creating a Reference List Citation for a Published Source

- Material on websites is also considered “published,” even if it’s not peer-reviewed or associated with a formal publishing company.

- While academic dissertations or theses that are print-only are considered unpublished, these types of documents are considered published if they’re included in an online database (such as ProQuest) or incorporated into an institutional repository.

- For example, you may write, “Gardner, L. M.” Or, “Meek, P. Q., Kendrick, L. H., & Hill, R. W.”

- If there is no author, you can list the name of the organization that published the research paper. For example, you may write, “American Cancer Society” or “The Reading Room.”

- Formally published documents that don’t list an author or that have a corporate author are typically reports or white papers .

- For example, you may write, “Gardner, L. M. (2008).” Or, “American Cancer Society. (2015).”

- For example, you may write, “Gardner, L. M. (2008). Crustaceans: Research and data.” Or, “American Cancer Society. (2015). Cervical cancer rates in women ages 20-45.”

- For example, for a journal article, you may write, “Gardner, L. M. (2008). Crustaceans: Research and data. Modern Journal of Malacostracan Research, 25, 150-305.”

- For a book chapter, you could write: “Wooster, B. W. (1937). A comparative study of modern Dutch cow creamers. In T. E. Travers (Ed.), A Detailed History of Tea Serviceware (pp. 127-155). London: Wimble Press."

- For example, you may write, “Kotb, M. A., Kamal, A. M., Aldossary, N. M., & Bedewi, M. A. (2019). Effect of vitamin D replacement on depression in multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis and Related Disorders, 29, 111-117. Retrieved from PubMed, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30708308.

- If you’re citing a paper or article that was published online but did not come from an academic journal or database, provide information about the author (if known), the date of publication (if available), and the website where you found the article. For example: “Hill, M. (n.d.). Egypt in the Ptolemaic Period. Retrieved from https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ptol/hd_ptol.htm”

Citing Unpublished Sources in Your Reference List

- Print-only dissertations or theses.

- Articles or book chapters that are in press or have been recently prepared or submitted for publication.

- Papers that have been rejected for publication or were never intended for publication (such as student research papers or unpublished conference papers).

- If the paper is currently being prepared for publication, include the author’s name, the year when the current draft was completed, and the title of the article in italics, followed by “Manuscript in preparation.” For example: Wooster, B. W. (1932). What the well-dressed man is wearing. Manuscript in preparation.

- If the paper has been submitted for publication, format the citation the same way as if it were in preparation, but instead follow the title with “Manuscript submitted for publication.” For example: Wooster, B. W. (1932). What the well-dressed man is wearing. Manuscript submitted for publication.

- If the paper has been accepted for publication but is not yet published, replace the date with “in press.” Do not italicize the paper title, but do include the title of the periodical or book in which it will be published and italicize that. For example: Wooster, B. W. (in press). What the well-dressed man is wearing. Milady’s Boudoir.

- If the paper was written for a conference but never published, your citation should look like this: Riker, W. T. (2019, March). Traditional methods for the preparation of spiny lobe-fish. Paper presented at the 325th Annual Intergalactic Culinary Conference, San Francisco, CA.

- For an unpublished paper written by a student for a class, include details about the institution where the paper was written. For example: Crusher, B. H. (2019). A typology of Cardassian skin diseases. Unpublished manuscript, Department of External Medicine, Starfleet Academy, San Francisco, CA.

- For example, you may write, “Pendlebottom, R. H. (2011). Iconography in Italian Frescos (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). New York University, New York, United States.”

Community Q&A

- If you want certain information to stand out in the research paper, then you can consider using a block quote. Thanks Helpful 0 Not Helpful 0

You Might Also Like

- ↑ https://libraryguides.vu.edu.au/apa-referencing/7JournalArticles

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_author_authors.html

- ↑ https://bowvalleycollege.libguides.com/c.php?g=714519&p=5093747

- ↑ https://guides.libraries.psu.edu/apaquickguide/intext

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/in_text_citations_the_basics.html

- ↑ https://libguides.southernct.edu/c.php?g=7125&p=34582#1951239

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_electronic_sources.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_articles_in_periodicals.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_books.html

- ↑ https://morlingcollege.libguides.com/apareferencing/unpublished-or-informally-published-work

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/general_apa_faqs.html

- ↑ https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/apa_style/apa_formatting_and_style_guide/reference_list_other_print_sources.html

About This Article

To cite a research paper in-text in APA, name the author in the text to introduce the quote and put the publication date for the text in parentheses. At the end of your quote, put the page number in parentheses. If you don’t mention the author in your prose, include them in the citation. Start the citation, which should come at the end of the quote, by listing the author’s last name, the year of publication, and the page number. Make sure to put all of this information in parentheses. If there’s no author, use the name of the organization that published the paper or the first few words from the title. To learn how to cite published and unpublished sources in your reference list, keep reading! Did this summary help you? Yes No

- Send fan mail to authors

Did this article help you?

Featured Articles

Trending Articles

Watch Articles

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Do Not Sell or Share My Info

- Not Selling Info

Get all the best how-tos!

Sign up for wikiHow's weekly email newsletter

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 11. Citing Sources

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A citation is a formal reference to a published or unpublished source that you consulted and obtained information from while writing your research paper. It refers to a source of information that supports a factual statement, proposition, argument, or assertion or any quoted text obtained from a book, article, web site, or any other type of material . In-text citations are embedded within the body of your paper and use a shorthand notation style that refers to a complete description of the item at the end of the paper. Materials cited at the end of a paper may be listed under the heading References, Sources, Works Cited, or Bibliography. Rules on how to properly cite a source depends on the writing style manual your professor wants you to use for the class [e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago, Turabian, etc.]. Note that some disciplines have their own citation rules [e.g., law].

Citations: Overview. OASIS Writing Center, Walden University; Research and Citation. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Citing Sources. University Writing Center, Texas A&M University.

Reasons for Citing Your Sources

Reasons for Citing Sources in Your Research Paper

English scientist, Sir Isaac Newton, once wrote, "If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.”* Citations support learning how to "see further" through processes of intellectual discovery, critical thinking, and applying a deliberate method of navigating through the scholarly landscape by tracking how cited works are propagated by scholars over time and the subsequent ways this leads to the devarication of new knowledge.

Listed below are specific reasons why citing sources is an important part of doing good research.

- Shows the reader where to find more information . Citations help readers expand their understanding and knowledge about the issues being investigated. One of the most effective strategies for locating authoritative, relevant sources about a research problem is to review materials cited in studies published by other authors. In this way, the sources you cite help the reader identify where to go to examine the topic in more depth and detail.

- Increases your credibility as an author . Citations to the words, ideas, and arguments of scholars demonstrates that you have conducted a thorough review of the literature and, therefore, you are reporting your research results or proposing recommended courses of action from an informed and critically engaged perspective. Your citations offer evidence that you effectively contemplated, evaluated, and synthesized sources of information in relation to your conceptualization of the research problem.

- Illustrates the non-linear and contested nature of knowledge creation . The sources you cite show the reader how you characterized the dynamics of prior knowledge creation relevant to the research problem and how you managed to effectively identify the contested relationships between problems and solutions proposed among scholars. Citations don't just list materials used in your study, they tell a story about how prior knowledge-making emerged from a constant state of creation, renewal, and transformation.

- Reinforces your arguments . Sources cited in your paper provide the evidence that readers need to determine that you properly addressed the “So What?” question. This refers to whether you considered the relevance and significance of the research problem, its implications applied to creating new knowledge, and its importance for improving practice. In this way, citations draw attention to and support the legitimacy and originality of your own ideas.

- Demonstrates that you "listened" to relevant conversations among scholars before joining in . Your citations tell the reader where you developed an understanding of the debates among scholars. They show how you educated yourself about ongoing conversations taking place within relevant communities of researchers before inserting your own ideas and arguments. In peer-reviewed scholarship, most of these conversations emerge within books, research reports, journal articles, and other cited works.

- Delineates alternative approaches to explaining the research problem . If you disagree with prior research assumptions or you believe that a topic has been understudied or you find that there is a gap in how scholars have understood a problem, your citations serve as the source materials from which to analyze and present an alternative viewpoint or to assert that a different course of action should be pursued. In short, the materials you cite serve as the means by which to argue persuasively against long-standing assumptions propagated in prior studies.

- Helps the reader understand contextual aspects of your research . Cited sources help readers understand the specific circumstances, conditions, and settings of the problem being investigated and, by extension, how your arguments can be fully understood and assessed. Citations place your line of reasoning within a specific contextualized framework based on how others have studied the problem and how you interpreted their findings in support of your overall research objectives.

- Frames the development of concepts and ideas within the literature . No topic in the social and behavioral sciences rests in isolation from research that has taken place in the past. Your citations help the reader understand the growth and transformation of the theoretical assumptions, key concepts, and systematic inquiries that emerged prior to your engagement with the research problem.

- Underscores what sources were most important to you . Your citations represent a set of choices made about what you determined to be the most important sources for understanding the topic. They not only list what you discovered, but why it matters and how the materials you chose to cite fit within the broader context of your research design and arguments. As part of an overall assessment of the study’s validity and reliability , the choices you make also helps the reader determine what research may have been excluded.

- Provides evidence of interdisciplinary thinking . An important principle of good research is to extend your review of the literature beyond the predominant disciplinary space where scholars have examined a topic. Citations provide evidence that you have integrated epistemological arguments, observations, and/or the methodological strategies from other disciplines into your paper, thereby demonstrating that you understand the complex, interconnected nature of contemporary research problems.

- Supports critical thinking and independent learning . Evaluating the authenticity, reliability, validity, and originality of prior research is an act of interpretation and introspective reasoning applied to assessing whether a source of information will contribute to understanding the problem in ways that are persuasive and align with your overall research objectives. Reviewing and citing prior studies represents a deliberate act of critically scrutinizing each source as part of your overall assessment of how scholars have confronted the research problem.

- Honors the achievements of others . As Susan Blum recently noted,** citations not only identify sources used, they acknowledge the achievements of scholars within the larger network of research about the topic. Citing sources is a normative act of professionalism within academe and a way to highlight and recognize the work of scholars who likely do not obtain any tangible benefits or monetary value from their research endeavors.

*Vernon. Jamie L. "On the Shoulder of Giants." American Scientist 105 (July-August 2017): 194.

**Blum, Susan D. "In Defense of the Morality of Citation.” Inside Higher Ed , January 29, 2024.

Aksnes, Dag W., Liv Langfeldt, and Paul Wouters. "Citations, Citation Indicators, and Research Quality: An Overview of Basic Concepts and Theories." Sage Open 9 (January-March 2019): https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244019829575; Blum, Susan Debra. My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009; Bretag, Tracey., editor. Handbook of Academic Integrity . Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020; Ballenger, Bruce P. The Curious Researcher: A Guide to Writing Research Papers . 7th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2012; D'Angelo, Barbara J. "Using Source Analysis to Promote Critical Thinking." Research Strategies 18 (Winter 2001): 303-309; Mauer, Barry and John Venecek. “Scholarship as Conversation.” Strategies for Conducting Literary Research, University of Central Florida, 2021; Why Cite? Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale University; Citing Information. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Harvard College Writing Program. Harvard University; Newton, Philip. "Academic Integrity: A Quantitative Study of Confidence and Understanding in Students at the Start of Their Higher Education." Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education 41 (2016): 482-497; Referencing More Effectively. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra; Using Sources. Yale College Writing Center. Yale University; Vosburgh, Richard M. "Closing the Academic-practitioner Gap: Research Must Answer the “SO WHAT” Question." H uman Resource Management Review 32 (March 2022): 100633; When and Why to Cite Sources. Information Literacy Playlists, SUNY, Albany Libraries.

Structure and Writing Style

Referencing your sources means systematically showing what information or ideas you acquired from another author’s work, and identifying where that information come from . You must cite research in order to do research, but at the same time, you must delineate what are your original thoughts and ideas and what are the thoughts and ideas of others. Citations help achieve this. Procedures used to cite sources vary among different fields of study. If not outlined in your course syllabus or writing assignment, always speak with your professor about what writing style for citing sources should be used for the class because it is important to fully understand the citation style to be used in your paper, and to apply it consistently. If your professor defers and tells you to "choose whatever you want, just be consistent," then choose the citation style you are most familiar with or that is appropriate to your major [e.g., use Chicago style if its a history class; use APA if its an education course; use MLA if it is literature or a general writing course].

GENERAL GUIDELINES

1. Are there any reasons I should avoid referencing other people's work? No. If placed in the proper context, r eferencing other people's research is never an indication that your work is substandard or lacks originality. In fact, the opposite is true. If you write your paper without adequate references to previous studies, you are signaling to the reader that you are not familiar with the literature on the topic, thereby, undermining the validity of your study and your credibility as a researcher. Including references in academic writing is one of the most important ways to demonstrate your knowledge and understanding of how the research problem has been addressed. It is the intellectual packaging around which you present your thoughts and ideas to the reader.

2. What should I do if I find out that my great idea has already been studied by another researcher? It can be frustrating to come up with what you believe is a great topic only to find that it's already been thoroughly studied. However, do not become frustrated by this. You can acknowledge the prior research by writing in the text of your paper [see also Smith, 2002], then citing the complete source in your list of references. Use the discovery of prior studies as an opportunity to demonstrate the significance of the problem being investigated and, if applicable, as a means of delineating your analysis from those of others [e.g., the prior study is ten years old and doesn't take into account new variables]. Strategies for responding to prior research can include: stating how your study updates previous understandings about the topic, offering a new or different perspective, applying a different or innovative method of data gathering, and/or describing a new set of insights, guidelines, recommendations, best practices, or working solutions.

3. What should I do if I want to use an adapted version of someone else's work? You still must cite the original work. For example, maybe you are using a table of statistics from a journal article published in 1996 by author Smith, but you have altered or added new data to it. Reference the revised chart, such as, [adapted from Smith, 1996], then cite the complete source in your list of references. You can also use other terms in order to specify the exact relationship between the original source and the version you have presented, such as, "based on data from Smith [1996]...," or "summarized from Smith [1996]...." Citing the original source helps the reader locate where the information was first presented and under what context it was used as well as to evaluate how effectively you applied it to your own research.

4. What should I do if several authors have published very similar information or ideas? You can indicate that the idea or information can be found in the works of others by stating something similar to the following example: "Though many scholars have applied rational choice theory to understanding economic relations among nations [Smith, 1989; Jones, 1991; Johnson, 1994; Anderson, 2003], little attention has been given to applying the theory to examining the influence of non-governmental organizations in a globalized economy." If you only reference one author or only the most recent study, then your readers may assume that only one author has published on this topic, or more likely, they will conclude that you have not conducted a thorough literature review. Referencing all relevant authors of prior studies gives your readers a clear idea of the breadth of analysis you conducted in preparing to study the research problem. If there has been a significant number of prior studies on the topic, describe the most comprehensive and recent works because they will presumably discuss and reference the older studies. However, note in your review of the literature that there has been significant scholarship devoted to the topic so the reader knows that you are aware of the numerous prior studies.

5. What if I find exactly what I want to say in the writing of another researcher? In the social sciences, the rationale in duplicating prior research is generally governed by the passage of time, changing circumstances or conditions, or the emergence of variables that necessitate a new investigation . If someone else has recently conducted a thorough investigation of precisely the same research problem that you intend to study, then you likely will have to revise your topic, or at the very least, review this literature to identify something new to say about the problem. However, if it is someone else's particularly succinct expression, but it fits perfectly with what you are trying to say, then you can quote from the author directly, referencing the source. Identifying an author who has made the exact same point that you want to make can be an opportunity to add legitimacy to, as well as reinforce the significance of, the research problem you are investigating. The key is to build on that idea in new and innovative ways. If you are not sure how to do this, consult with a librarian .

6. Should I cite a source even if it was published long ago? Any source used in writing your paper should be cited, regardless of when it was written. However, in building a case for understanding prior research about your topic, it is generally true that you should focus on citing more recently published studies because they presumably have built upon the research of older studies. When referencing prior studies, use the research problem as your guide when considering what to cite. If a study from forty years ago investigated the same topic, it probably should be examined and considered in your list of references because the research may have been foundational or groundbreaking at the time, even if its findings are no longer relevant to current conditions or reflect current thinking [one way to determine if a study is foundational or groundbreaking is to examine how often it has been cited in recent studies using the "Cited by" feature of Google Scholar ]. However, if an older study only relates to the research problem tangentially or it has not been cited in recent studies, then it may be more appropriate to list it under further readings .

7. Can I cite unusual and non-scholarly sources in my research paper? The majority of the citations in a research paper should be to scholarly [a.k.a., academic; peer-reviewed] studies that rely on an objective and logical analysis of the research problem based on empirical evidence that reliably supports your arguments. However, any type of source can be considered valid if it brings relevant understanding and clarity to the topic. This can include, for example, non-textual elements such as photographs, maps, or illustrations. A source can include materials from special or archival collections, such as, personal papers, manuscripts, business memorandums, the official records of an organization, or digitized collections. Citations can also be to unusual items, such as, an audio recording, a transcript from a television show, a unique set of data, or a social media post. The challenge is knowing how to properly cite unusual and non-scholarly sources because they often do not fit within standard citation rules like books or journal articles. Given this, consult with a librarian if you are unsure how to cite a source.

NOTE: In any academic writing, you are required to identify which ideas, facts, thoughts, concepts, or declarative statements are yours and which are derived from the research of others. The only exception to this rule is information that is considered to be a commonly known fact [e.g., "George Washington was the first president of the United States"] or a statement that is self-evident [e.g., "Australia is a country in the Global South"]. Appreciate, however, that any "commonly known fact" or self-evidencing statement is culturally constructed and shaped by specific social and aesthetical biases . If you have any doubt about whether or not a fact is considered to be widely understood knowledge, provide a supporting citation, or, ask your professor for clarification about whether the statement should be cited.

Ballenger, Bruce P. The Curious Researcher: A Guide to Writing Research Papers . 7th edition. Boston, MA: Pearson, 2012; Blum, Susan Debra. My Word!: Plagiarism and College Culture . Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2009; Bretag, Tracey., editor. Handbook of Academic Integrity . Singapore: Springer Singapore, 2020; Carlock, Janine. Developing Information Literacy Skills: A Guide to Finding, Evaluating, and Citing Sources . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 2020; Harvard Guide to Using Sources. Harvard College Writing Program. Harvard University; How to Cite Other Sources in Your Paper. The Structure, Format, Content, and Style of a Journal-Style Scientific Paper. Department of Biology. Bates College; Lunsford, Andrea A. and Robert Connors; The St. Martin's Handbook . New York: St. Martin's Press, 1989; Mills, Elizabeth Shown. Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace . 3rd edition. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Company, 2015; Research and Citation Resources. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Why Cite? Poorvu Center for Teaching and Learning, Yale Univeraity.

Other Citation Research Guides

The following USC Libraries research guide can help you properly cite sources in your research paper:

- Citation Guide

The following USC Libraries research guide offers basic information on using images and media in research:

Listed below are particularly well-done and comprehensive websites that provide specific examples of how to cite sources under different style guidelines.

- Purdue University Online Writing Lab

- Southern Cross University Harvard Referencing Style

- University of Wisconsin Writing Center

This is a useful guide concerning how to properly cite images in your research paper.

- Colgate Visual Resources Library, Citing Images

This guide provides good information on the act of citation analysis, whereby you count the number of times a published work is cited by other works in order to measure the impact of a publication or author.

Measuring Your Impact: Impact Factor, Citation Analysis, and other Metrics: Citation Analysis [Sandy De Groote, University of Illinois, Chicago]

Automatic Citation Generators

The links below lead to systems where you can type in your information and have a citation compiled for you. Note that these systems are not foolproof so it is important that you verify that the citation is correct and check your spelling, capitalization, etc. However, they can be useful in creating basic types of citations, particularly for online sources.

- BibMe -- APA, MLA, Chicago, and Turabian styles

- DocsCite -- for citing government publications in APA or MLA formats

- EasyBib -- APA, MLA, and Chicago styles

- Son of Citation Machine -- APA, MLA, Chicago, and Turabian styles

NOTE: Many companies that create the research databases the USC Libraries subscribe to, such as ProQuest , include built-in citation generators that help take the guesswork out of how to properly cite a work. When available, you should always utilize these features because they not only generate a citation to the source [e.g., a journal article], but include information about where you accessed the source [e.g., the database].

- << Previous: Writing Concisely

- Next: Avoiding Plagiarism >>

- Last Updated: May 25, 2024 4:09 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Privacy Policy

Home » How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and Examples

How to Cite Research Paper – All Formats and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Paper Citation

Research paper citation refers to the act of acknowledging and referencing a previously published work in a scholarly or academic paper . When citing sources, researchers provide information that allows readers to locate the original source, validate the claims or arguments made in the paper, and give credit to the original author(s) for their work.

The citation may include the author’s name, title of the publication, year of publication, publisher, and other relevant details that allow readers to trace the source of the information. Proper citation is a crucial component of academic writing, as it helps to ensure accuracy, credibility, and transparency in research.

How to Cite Research Paper

There are several formats that are used to cite a research paper. Follow the guide for the Citation of a Research Paper:

Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Publisher, Year of Publication.

Example : Smith, John. The History of the World. Penguin Press, 2010.

Journal Article

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Title of Journal, vol. Volume Number, no. Issue Number, Year of Publication, pp. Page Numbers.

Example : Johnson, Emma. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Environmental Science Journal, vol. 10, no. 2, 2019, pp. 45-59.

Research Paper

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Paper.” Conference Name, Location, Date of Conference.

Example : Garcia, Maria. “The Importance of Early Childhood Education.” International Conference on Education, Paris, 5-7 June 2018.

Author’s Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Title, Publisher, Date of Publication, URL.

Example : Smith, John. “The Benefits of Exercise.” Healthline, Healthline Media, 1 March 2022, https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-exercise.

News Article

Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper, Date of Publication, URL.

Example : Robinson, Sarah. “Biden Announces New Climate Change Policies.” The New York Times, 22 Jan. 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/climate/biden-climate-change-policies.html.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example: Smith, J. (2010). The History of the World. Penguin Press.

Author, A. A., Author, B. B., & Author, C. C. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of Journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

Example: Johnson, E., Smith, K., & Lee, M. (2019). The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture. Environmental Science Journal, 10(2), 45-59.

Author, A. A. (Year of publication). Title of paper. In Editor First Initial. Last Name (Ed.), Title of Conference Proceedings (page numbers). Publisher.

Example: Garcia, M. (2018). The Importance of Early Childhood Education. In J. Smith (Ed.), Proceedings from the International Conference on Education (pp. 60-75). Springer.

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of webpage. Website name. URL

Example: Smith, J. (2022, March 1). The Benefits of Exercise. Healthline. https://www.healthline.com/health/benefits-of-exercise

Author, A. A. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Newspaper name. URL.

Example: Robinson, S. (2021, January 22). Biden Announces New Climate Change Policies. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/01/22/climate/biden-climate-change-policies.html

Chicago/Turabian style

Please note that there are two main variations of the Chicago style: the author-date system and the notes and bibliography system. I will provide examples for both systems below.

Author-Date system:

- In-text citation: (Author Last Name Year, Page Number)

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher.

- In-text citation: (Smith 2005, 28)

- Reference list: Smith, John. 2005. The History of America. New York: Penguin Press.

Notes and Bibliography system:

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, Title of Book (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), Page Number.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. Title of Book. Place of publication: Publisher, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: John Smith, The History of America (New York: Penguin Press, 2005), 28.

- Bibliography citation: Smith, John. The History of America. New York: Penguin Press, 2005.

JOURNAL ARTICLES:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Article Title.” Journal Title Volume Number (Issue Number): Page Range.

- In-text citation: (Johnson 2010, 45)

- Reference list: Johnson, Mary. 2010. “The Impact of Social Media on Society.” Journal of Communication 60(2): 39-56.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Article Title,” Journal Title Volume Number, Issue Number (Year): Page Range.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Article Title.” Journal Title Volume Number, Issue Number (Year): Page Range.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Mary Johnson, “The Impact of Social Media on Society,” Journal of Communication 60, no. 2 (2010): 39-56.

- Bibliography citation: Johnson, Mary. “The Impact of Social Media on Society.” Journal of Communication 60, no. 2 (2010): 39-56.

RESEARCH PAPERS:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Paper.” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date. Publisher, Page Range.

- In-text citation: (Jones 2015, 12)

- Reference list: Jones, David. 2015. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015. Springer, 10-20.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Paper,” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date (Place of publication: Publisher, Year), Page Range.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Paper.” Conference Proceedings Title, Location, Date. Place of publication: Publisher, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: David Jones, “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture,” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015 (New York: Springer, 10-20).

- Bibliography citation: Jones, David. “The Effects of Climate Change on Agriculture.” Proceedings of the International Conference on Climate Change, Paris, France, June 1-3, 2015. New York: Springer, 10-20.

- In-text citation: (Author Last Name Year)

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL.

- In-text citation: (Smith 2018)

- Reference list: Smith, John. 2018. “The Importance of Recycling.” Environmental News Network. https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Webpage,” Website Name, URL (accessed Date).

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Webpage.” Website Name. URL (accessed Date).

- Footnote/Endnote citation: John Smith, “The Importance of Recycling,” Environmental News Network, https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling (accessed April 8, 2023).

- Bibliography citation: Smith, John. “The Importance of Recycling.” Environmental News Network. https://www.enn.com/articles/54374-the-importance-of-recycling (accessed April 8, 2023).

NEWS ARTICLES:

- Reference list: Author Last Name, First Name. Year. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper, Month Day.

- In-text citation: (Johnson 2022)

- Reference list: Johnson, Mary. 2022. “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity.” The New York Times, January 15.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Author First Name Last Name, “Title of Article,” Name of Newspaper (City), Month Day, Year.

- Bibliography citation: Author Last Name, First Name. “Title of Article.” Name of Newspaper (City), Month Day, Year.

- Footnote/Endnote citation: Mary Johnson, “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity,” The New York Times (New York), January 15, 2022.

- Bibliography citation: Johnson, Mary. “New Study Finds Link Between Coffee and Longevity.” The New York Times (New York), January 15, 2022.

Harvard referencing style

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of book. Publisher.

Example: Smith, J. (2008). The Art of War. Random House.

Journal article:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of article. Title of journal, volume number(issue number), page range.

Example: Brown, M. (2012). The impact of social media on business communication. Harvard Business Review, 90(12), 85-92.

Research paper:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year of publication). Title of paper. In Editor’s First initial. Last name (Ed.), Title of book (page range). Publisher.

Example: Johnson, R. (2015). The effects of climate change on agriculture. In S. Lee (Ed.), Climate Change and Sustainable Development (pp. 45-62). Springer.

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of page. Website name. URL.

Example: Smith, J. (2017, May 23). The history of the internet. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-the-internet

News article:

Format: Author’s Last name, First initial. (Year, Month Day of publication). Title of article. Title of newspaper, page number (if applicable).

Example: Thompson, E. (2022, January 5). New study finds coffee may lower risk of dementia. The New York Times, A1.

IEEE Format

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Book. Publisher.

Smith, J. K. (2015). The Power of Habit: Why We Do What We Do in Life and Business. Random House.

Journal Article:

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Title of Journal, Volume Number (Issue Number), page numbers.

Johnson, T. J., & Kaye, B. K. (2016). Interactivity and the Future of Journalism. Journalism Studies, 17(2), 228-246.

Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Paper. Paper presented at Conference Name, Location.

Jones, L. K., & Brown, M. A. (2018). The Role of Social Media in Political Campaigns. Paper presented at the 2018 International Conference on Social Media and Society, Copenhagen, Denmark.

- Website: Author(s) or Organization Name. (Year of Publication or Last Update). Title of Webpage. Website Name. URL.

Example: National Aeronautics and Space Administration. (2019, August 29). NASA’s Mission to Mars. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/topics/journeytomars/index.html

- News Article: Author(s). (Year of Publication). Title of Article. Name of News Source. URL.

Example: Johnson, M. (2022, February 16). Climate Change: Is it Too Late to Save the Planet? CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2022/02/16/world/climate-change-planet-scn/index.html

Vancouver Style

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “The study conducted by Smith and Johnson^1 found that…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of book. Edition if any. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Smith J, Johnson L. Introduction to Molecular Biology. 2nd ed. New York: Wiley-Blackwell; 2015.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “Several studies have reported that^1,2,3…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of article. Abbreviated name of journal. Year of publication; Volume number (Issue number): Page range.

Example: Jones S, Patel K, Smith J. The effects of exercise on cardiovascular health. J Cardiol. 2018; 25(2): 78-84.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “Previous research has shown that^1,2,3…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of paper. In: Editor(s). Title of the conference proceedings. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication. Page range.

Example: Johnson L, Smith J. The role of stem cells in tissue regeneration. In: Patel S, ed. Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Regenerative Medicine. London: Academic Press; 2016. p. 68-73.

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “According to the World Health Organization^1…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of webpage. Name of website. URL [Accessed Date].

Example: World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public [Accessed 3 March 2023].

In-text citation: Use superscript numbers to cite sources in the text, e.g., “According to the New York Times^1…”.

Reference list citation: Format: Author(s). Title of article. Name of newspaper. Year Month Day; Section (if any): Page number.

Example: Jones S. Study shows that sleep is essential for good health. The New York Times. 2022 Jan 12; Health: A8.

Author(s). Title of Book. Edition Number (if it is not the first edition). Publisher: Place of publication, Year of publication.

Example: Smith, J. Chemistry of Natural Products. 3rd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, 2015.

Journal articles:

Author(s). Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume, Inclusive Pagination.

Example: Garcia, A. M.; Jones, B. A.; Smith, J. R. Selective Synthesis of Alkenes from Alkynes via Catalytic Hydrogenation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 10754-10759.

Research papers:

Author(s). Title of Paper. Journal Name Year, Volume, Inclusive Pagination.

Example: Brown, H. D.; Jackson, C. D.; Patel, S. D. A New Approach to Photovoltaic Solar Cells. J. Mater. Chem. 2018, 26, 134-142.

Author(s) (if available). Title of Webpage. Name of Website. URL (accessed Month Day, Year).

Example: National Institutes of Health. Heart Disease and Stroke. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/heart-disease-and-stroke (accessed April 7, 2023).

News articles:

Author(s). Title of Article. Name of News Publication. Date of Publication. URL (accessed Month Day, Year).

Example: Friedman, T. L. The World is Flat. New York Times. April 7, 2023. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/07/opinion/world-flat-globalization.html (accessed April 7, 2023).

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a book should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of book (in italics)

- Edition (if applicable)

- Place of publication

- Year of publication

Lodish H, Berk A, Zipursky SL, et al. Molecular Cell Biology. 4th ed. New York, NY: W. H. Freeman; 2000.

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a journal article should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of article

- Abbreviated title of journal (in italics)

- Year of publication; volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Chen H, Huang Y, Li Y, et al. Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on depression in adolescents and young adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(6):e207081. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.7081

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a research paper should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of paper

- Name of journal or conference proceeding (in italics)

- Volume number(issue number):page numbers.

Bredenoord AL, Kroes HY, Cuppen E, Parker M, van Delden JJ. Disclosure of individual genetic data to research participants: the debate reconsidered. Trends Genet. 2011;27(2):41-47. doi:10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.004

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a website should include the following information, in this order:

- Title of web page or article

- Name of website (in italics)

- Date of publication or last update (if available)

- URL (website address)

- Date of access (month day, year)

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. How to protect yourself and others. CDC. Published February 11, 2022. Accessed February 14, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/prevention.html

In AMA Style Format, the citation for a news article should include the following information, in this order:

- Name of newspaper or news website (in italics)

- Date of publication

Gorman J. Scientists use stem cells from frogs to build first living robots. The New York Times. January 13, 2020. Accessed January 14, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/13/science/living-robots-xenobots.html

Bluebook Format

One author: Daniel J. Solove, The Future of Reputation: Gossip, Rumor, and Privacy on the Internet (Yale University Press 2007).

Two or more authors: Martha Nussbaum and Saul Levmore, eds., The Offensive Internet: Speech, Privacy, and Reputation (Harvard University Press 2010).

Journal article

One author: Daniel J. Solove, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review 154, no. 3 (January 2006): 477-560.

Two or more authors: Ethan Katsh and Andrea Schneider, “The Emergence of Online Dispute Resolution,” Journal of Dispute Resolution 2003, no. 1 (2003): 7-19.

One author: Daniel J. Solove, “A Taxonomy of Privacy,” GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 113, 2005.

Two or more authors: Ethan Katsh and Andrea Schneider, “The Emergence of Online Dispute Resolution,” Cyberlaw Research Paper Series Paper No. 00-5, 2000.

WebsiteElectronic Frontier Foundation, “Surveillance Self-Defense,” accessed April 8, 2023, https://ssd.eff.org/.

News article

One author: Mark Sherman, “Court Deals Major Blow to Net Neutrality Rules,” ABC News, January 14, 2014, https://abcnews.go.com/Politics/wireStory/court-deals-major-blow-net-neutrality-rules-21586820.

Two or more authors: Siobhan Hughes and Brent Kendall, “AT&T Wins Approval to Buy Time Warner,” Wall Street Journal, June 12, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/at-t-wins-approval-to-buy-time-warner-1528847249.

In-Text Citation: (Author’s last name Year of Publication: Page Number)

Example: (Smith 2010: 35)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Book. Edition. Place of publication: Publisher; Year of publication.

Example: Smith J. Biology: A Textbook. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010.

Example: (Johnson 2014: 27)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Article. Abbreviated Title of Journal. Year of publication;Volume(Issue):Page Numbers.

Example: Johnson S. The role of dopamine in addiction. J Neurosci. 2014;34(8): 2262-2272.

Example: (Brown 2018: 10)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Paper. Paper presented at: Name of Conference; Date of Conference; Place of Conference.

Example: Brown R. The impact of social media on mental health. Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association; August 2018; San Francisco, CA.

Example: (World Health Organization 2020: para. 2)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Webpage. Name of Website. URL. Published date. Accessed date.

Example: World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. WHO website. https://www.who.int/emergencies/disease-coronavirus-2019. Updated August 17, 2020. Accessed September 5, 2021.

Example: (Smith 2019: para. 5)

Reference List Citation: Author’s last name First Initial. Title of Article. Title of Newspaper or Magazine. Year of publication; Month Day:Page Numbers.

Example: Smith K. New study finds link between exercise and mental health. The New York Times. 2019;May 20: A6.

Purpose of Research Paper Citation

The purpose of citing sources in a research paper is to give credit to the original authors and acknowledge their contribution to your work. By citing sources, you are also demonstrating the validity and reliability of your research by showing that you have consulted credible and authoritative sources. Citations help readers to locate the original sources that you have referenced and to verify the accuracy and credibility of your research. Additionally, citing sources is important for avoiding plagiarism, which is the act of presenting someone else’s work as your own. Proper citation also shows that you have conducted a thorough literature review and have used the existing research to inform your own work. Overall, citing sources is an essential aspect of academic writing and is necessary for building credibility, demonstrating research skills, and avoiding plagiarism.

Advantages of Research Paper Citation

There are several advantages of research paper citation, including:

- Giving credit: By citing the works of other researchers in your field, you are acknowledging their contribution and giving credit where it is due.

- Strengthening your argument: Citing relevant and reliable sources in your research paper can strengthen your argument and increase its credibility. It shows that you have done your due diligence and considered various perspectives before drawing your conclusions.