Research Topics & Ideas: Healthcare

100+ Healthcare Research Topic Ideas To Fast-Track Your Project

Finding and choosing a strong research topic is the critical first step when it comes to crafting a high-quality dissertation, thesis or research project. If you’ve landed on this post, chances are you’re looking for a healthcare-related research topic , but aren’t sure where to start. Here, we’ll explore a variety of healthcare-related research ideas and topic thought-starters across a range of healthcare fields, including allopathic and alternative medicine, dentistry, physical therapy, optometry, pharmacology and public health.

NB – This is just the start…

The topic ideation and evaluation process has multiple steps . In this post, we’ll kickstart the process by sharing some research topic ideas within the healthcare domain. This is the starting point, but to develop a well-defined research topic, you’ll need to identify a clear and convincing research gap , along with a well-justified plan of action to fill that gap.

If you’re new to the oftentimes perplexing world of research, or if this is your first time undertaking a formal academic research project, be sure to check out our free dissertation mini-course. In it, we cover the process of writing a dissertation or thesis from start to end. Be sure to also sign up for our free webinar that explores how to find a high-quality research topic.

Overview: Healthcare Research Topics

- Allopathic medicine

- Alternative /complementary medicine

- Veterinary medicine

- Physical therapy/ rehab

- Optometry and ophthalmology

- Pharmacy and pharmacology

- Public health

- Examples of healthcare-related dissertations

Allopathic (Conventional) Medicine

- The effectiveness of telemedicine in remote elderly patient care

- The impact of stress on the immune system of cancer patients

- The effects of a plant-based diet on chronic diseases such as diabetes

- The use of AI in early cancer diagnosis and treatment

- The role of the gut microbiome in mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety

- The efficacy of mindfulness meditation in reducing chronic pain: A systematic review

- The benefits and drawbacks of electronic health records in a developing country

- The effects of environmental pollution on breast milk quality

- The use of personalized medicine in treating genetic disorders

- The impact of social determinants of health on chronic diseases in Asia

- The role of high-intensity interval training in improving cardiovascular health

- The efficacy of using probiotics for gut health in pregnant women

- The impact of poor sleep on the treatment of chronic illnesses

- The role of inflammation in the development of chronic diseases such as lupus

- The effectiveness of physiotherapy in pain control post-surgery

Topics & Ideas: Alternative Medicine

- The benefits of herbal medicine in treating young asthma patients

- The use of acupuncture in treating infertility in women over 40 years of age

- The effectiveness of homoeopathy in treating mental health disorders: A systematic review

- The role of aromatherapy in reducing stress and anxiety post-surgery

- The impact of mindfulness meditation on reducing high blood pressure

- The use of chiropractic therapy in treating back pain of pregnant women

- The efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine such as Shun-Qi-Tong-Xie (SQTX) in treating digestive disorders in China

- The impact of yoga on physical and mental health in adolescents

- The benefits of hydrotherapy in treating musculoskeletal disorders such as tendinitis

- The role of Reiki in promoting healing and relaxation post birth

- The effectiveness of naturopathy in treating skin conditions such as eczema

- The use of deep tissue massage therapy in reducing chronic pain in amputees

- The impact of tai chi on the treatment of anxiety and depression

- The benefits of reflexology in treating stress, anxiety and chronic fatigue

- The role of acupuncture in the prophylactic management of headaches and migraines

Topics & Ideas: Dentistry

- The impact of sugar consumption on the oral health of infants

- The use of digital dentistry in improving patient care: A systematic review

- The efficacy of orthodontic treatments in correcting bite problems in adults

- The role of dental hygiene in preventing gum disease in patients with dental bridges

- The impact of smoking on oral health and tobacco cessation support from UK dentists

- The benefits of dental implants in restoring missing teeth in adolescents

- The use of lasers in dental procedures such as root canals

- The efficacy of root canal treatment using high-frequency electric pulses in saving infected teeth

- The role of fluoride in promoting remineralization and slowing down demineralization

- The impact of stress-induced reflux on oral health

- The benefits of dental crowns in restoring damaged teeth in elderly patients

- The use of sedation dentistry in managing dental anxiety in children

- The efficacy of teeth whitening treatments in improving dental aesthetics in patients with braces

- The role of orthodontic appliances in improving well-being

- The impact of periodontal disease on overall health and chronic illnesses

Tops & Ideas: Veterinary Medicine

- The impact of nutrition on broiler chicken production

- The role of vaccines in disease prevention in horses

- The importance of parasite control in animal health in piggeries

- The impact of animal behaviour on welfare in the dairy industry

- The effects of environmental pollution on the health of cattle

- The role of veterinary technology such as MRI in animal care

- The importance of pain management in post-surgery health outcomes

- The impact of genetics on animal health and disease in layer chickens

- The effectiveness of alternative therapies in veterinary medicine: A systematic review

- The role of veterinary medicine in public health: A case study of the COVID-19 pandemic

- The impact of climate change on animal health and infectious diseases in animals

- The importance of animal welfare in veterinary medicine and sustainable agriculture

- The effects of the human-animal bond on canine health

- The role of veterinary medicine in conservation efforts: A case study of Rhinoceros poaching in Africa

- The impact of veterinary research of new vaccines on animal health

Topics & Ideas: Physical Therapy/Rehab

- The efficacy of aquatic therapy in improving joint mobility and strength in polio patients

- The impact of telerehabilitation on patient outcomes in Germany

- The effect of kinesiotaping on reducing knee pain and improving function in individuals with chronic pain

- A comparison of manual therapy and yoga exercise therapy in the management of low back pain

- The use of wearable technology in physical rehabilitation and the impact on patient adherence to a rehabilitation plan

- The impact of mindfulness-based interventions in physical therapy in adolescents

- The effects of resistance training on individuals with Parkinson’s disease

- The role of hydrotherapy in the management of fibromyalgia

- The impact of cognitive-behavioural therapy in physical rehabilitation for individuals with chronic pain

- The use of virtual reality in physical rehabilitation of sports injuries

- The effects of electrical stimulation on muscle function and strength in athletes

- The role of physical therapy in the management of stroke recovery: A systematic review

- The impact of pilates on mental health in individuals with depression

- The use of thermal modalities in physical therapy and its effectiveness in reducing pain and inflammation

- The effect of strength training on balance and gait in elderly patients

Topics & Ideas: Optometry & Opthalmology

- The impact of screen time on the vision and ocular health of children under the age of 5

- The effects of blue light exposure from digital devices on ocular health

- The role of dietary interventions, such as the intake of whole grains, in the management of age-related macular degeneration

- The use of telemedicine in optometry and ophthalmology in the UK

- The impact of myopia control interventions on African American children’s vision

- The use of contact lenses in the management of dry eye syndrome: different treatment options

- The effects of visual rehabilitation in individuals with traumatic brain injury

- The role of low vision rehabilitation in individuals with age-related vision loss: challenges and solutions

- The impact of environmental air pollution on ocular health

- The effectiveness of orthokeratology in myopia control compared to contact lenses

- The role of dietary supplements, such as omega-3 fatty acids, in ocular health

- The effects of ultraviolet radiation exposure from tanning beds on ocular health

- The impact of computer vision syndrome on long-term visual function

- The use of novel diagnostic tools in optometry and ophthalmology in developing countries

- The effects of virtual reality on visual perception and ocular health: an examination of dry eye syndrome and neurologic symptoms

Topics & Ideas: Pharmacy & Pharmacology

- The impact of medication adherence on patient outcomes in cystic fibrosis

- The use of personalized medicine in the management of chronic diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease

- The effects of pharmacogenomics on drug response and toxicity in cancer patients

- The role of pharmacists in the management of chronic pain in primary care

- The impact of drug-drug interactions on patient mental health outcomes

- The use of telepharmacy in healthcare: Present status and future potential

- The effects of herbal and dietary supplements on drug efficacy and toxicity

- The role of pharmacists in the management of type 1 diabetes

- The impact of medication errors on patient outcomes and satisfaction

- The use of technology in medication management in the USA

- The effects of smoking on drug metabolism and pharmacokinetics: A case study of clozapine

- Leveraging the role of pharmacists in preventing and managing opioid use disorder

- The impact of the opioid epidemic on public health in a developing country

- The use of biosimilars in the management of the skin condition psoriasis

- The effects of the Affordable Care Act on medication utilization and patient outcomes in African Americans

Topics & Ideas: Public Health

- The impact of the built environment and urbanisation on physical activity and obesity

- The effects of food insecurity on health outcomes in Zimbabwe

- The role of community-based participatory research in addressing health disparities

- The impact of social determinants of health, such as racism, on population health

- The effects of heat waves on public health

- The role of telehealth in addressing healthcare access and equity in South America

- The impact of gun violence on public health in South Africa

- The effects of chlorofluorocarbons air pollution on respiratory health

- The role of public health interventions in reducing health disparities in the USA

- The impact of the United States Affordable Care Act on access to healthcare and health outcomes

- The effects of water insecurity on health outcomes in the Middle East

- The role of community health workers in addressing healthcare access and equity in low-income countries

- The impact of mass incarceration on public health and behavioural health of a community

- The effects of floods on public health and healthcare systems

- The role of social media in public health communication and behaviour change in adolescents

Examples: Healthcare Dissertation & Theses

While the ideas we’ve presented above are a decent starting point for finding a healthcare-related research topic, they are fairly generic and non-specific. So, it helps to look at actual dissertations and theses to see how this all comes together.

Below, we’ve included a selection of research projects from various healthcare-related degree programs to help refine your thinking. These are actual dissertations and theses, written as part of Master’s and PhD-level programs, so they can provide some useful insight as to what a research topic looks like in practice.

- Improving Follow-Up Care for Homeless Populations in North County San Diego (Sanchez, 2021)

- On the Incentives of Medicare’s Hospital Reimbursement and an Examination of Exchangeability (Elzinga, 2016)

- Managing the healthcare crisis: the career narratives of nurses (Krueger, 2021)

- Methods for preventing central line-associated bloodstream infection in pediatric haematology-oncology patients: A systematic literature review (Balkan, 2020)

- Farms in Healthcare: Enhancing Knowledge, Sharing, and Collaboration (Garramone, 2019)

- When machine learning meets healthcare: towards knowledge incorporation in multimodal healthcare analytics (Yuan, 2020)

- Integrated behavioural healthcare: The future of rural mental health (Fox, 2019)

- Healthcare service use patterns among autistic adults: A systematic review with narrative synthesis (Gilmore, 2021)

- Mindfulness-Based Interventions: Combatting Burnout and Compassionate Fatigue among Mental Health Caregivers (Lundquist, 2022)

- Transgender and gender-diverse people’s perceptions of gender-inclusive healthcare access and associated hope for the future (Wille, 2021)

- Efficient Neural Network Synthesis and Its Application in Smart Healthcare (Hassantabar, 2022)

- The Experience of Female Veterans and Health-Seeking Behaviors (Switzer, 2022)

- Machine learning applications towards risk prediction and cost forecasting in healthcare (Singh, 2022)

- Does Variation in the Nursing Home Inspection Process Explain Disparity in Regulatory Outcomes? (Fox, 2020)

Looking at these titles, you can probably pick up that the research topics here are quite specific and narrowly-focused , compared to the generic ones presented earlier. This is an important thing to keep in mind as you develop your own research topic. That is to say, to create a top-notch research topic, you must be precise and target a specific context with specific variables of interest . In other words, you need to identify a clear, well-justified research gap.

Need more help?

If you’re still feeling a bit unsure about how to find a research topic for your healthcare dissertation or thesis, check out Topic Kickstarter service below.

You Might Also Like:

15 Comments

I need topics that will match the Msc program am running in healthcare research please

Hello Mabel,

I can help you with a good topic, kindly provide your email let’s have a good discussion on this.

Can you provide some research topics and ideas on Immunology?

Thank you to create new knowledge on research problem verse research topic

Help on problem statement on teen pregnancy

This post might be useful: https://gradcoach.com/research-problem-statement/

can you provide me with a research topic on healthcare related topics to a qqi level 5 student

Please can someone help me with research topics in public health ?

Hello I have requirement of Health related latest research issue/topics for my social media speeches. If possible pls share health issues , diagnosis, treatment.

I would like a topic thought around first-line support for Gender-Based Violence for survivors or one related to prevention of Gender-Based Violence

Please can I be helped with a master’s research topic in either chemical pathology or hematology or immunology? thanks

Can u please provide me with a research topic on occupational health and safety at the health sector

Good day kindly help provide me with Ph.D. Public health topics on Reproductive and Maternal Health, interventional studies on Health Education

may you assist me with a good easy healthcare administration study topic

May you assist me in finding a research topic on nutrition,physical activity and obesity. On the impact on children

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 06 May 2021

Co-producing knowledge in health and social care research: reflections on the challenges and ways to enable more equal relationships

- Michelle Farr ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8773-846X 1 , 2 ,

- Philippa Davies ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2678-7126 1 , 2 ,

- Heidi Andrews 1 , 2 ,

- Darren Bagnall 1 , 2 ,

- Emer Brangan ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1288-0960 1 , 2 , 3 &

- Rosemary Davies ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9969-1902 1 , 4

Humanities and Social Sciences Communications volume 8 , Article number: 105 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

6222 Accesses

22 Citations

32 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Health humanities

- Medical humanities

Researchers are increasingly encouraged to co-produce research, involving members of the public, service users, policy makers and practitioners in more equal relationships throughout a research project. The sharing of power is often highlighted as a key principle when co-producing research. However, health and social care research, as with many other academic disciplines, is carried out within embedded hierarchies and structural inequalities in universities, public service institutions, and research funding systems—as well as in society more broadly. This poses significant challenges to ambitions for co-production. This article explores the difficulties that are faced when trying to put ideal co-production principles into practice. A reflective account is provided of an interdisciplinary project that aimed to better understand how to reduce power differentials within co-produced research. The project facilitated five workshops, involving researchers from different disciplines, health, social care and community development staff and public contributors, who all had experience in co-production within research. In the workshops, people discussed how they had attempted to enable more equal relationships and shared ideas that supported more effective and equitable co-produced research. Shared interdisciplinary learning helped the project team to iteratively develop a training course, a map of resources and reflective questions to support co-produced research. The gap between co-production principles and practice is challenging. The article examines the constraints that exist when trying to share power, informed by multidisciplinary theories of power. To bring co-production principles into practice, changes are needed within research practices, cultures and structures; in understandings of what knowledge is and how different forms of knowledge are valued. The article outlines challenges and tensions when co-producing research and describes potential ideas and resources that may help to put co-production principles into practice. We highlight that trying to maintain all principles of co-production within the real-world of structural inequalities and uneven distribution of resources is a constant challenge, often remaining for now in the realm of aspiration.

Introduction

Co-production of research—where researchers, practitioners and members of the public collaborate to develop research together—is promoted as a way to strengthen public involvement, and create and implement more relevant and applicable knowledge, that is used in practice (Staniszewska et al., 2018 ; Hickey et al., 2018 ). Academic disciplines and funding bodies define the concept of co-production differently, using divergent methods and theories (Facer and Enright, 2016 ), with subsequent debate about what co-production is and who may be doing it ‘properly’. We use the INVOLVE definition and principles of co-producing research (Box 1 ) (Hickey et al., 2018 ), which includes the often-agreed principle to share power more equally between partners. However, the extent to which this is achievable within structural inequalities and institutional hierarchies is debatable (Flinders et al., 2016 ).

This commentary article reflects on a project that aimed to:

share interdisciplinary learning about co-produced research

understand how to enable more equal relationships with co-production partners, particularly public contributors—defined as members of the public including patients, potential patients, carers and people who use health and social care services (in contrast to people who have a professional role in health and social care services or research) (NIHR CED, 2020 ).

develop training and resources to support co-produced research.

The project was developed by a team of three applied health researchers, a public involvement lead and three public contributors (with in-depth experiences of co-produced research) undertaken within the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration (ARC) West, an organisation that develops applied health and social care research. Through facilitating five project workshops, we engaged with eleven researchers from five disciplines; six practitioners; and eleven public contributors with involvement and co-produced research experiences. We shared practical lessons across disciplinary boundaries about how to do co-produced research more equitably (Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ). These workshops helped the project team progressively and iteratively develop a training course, a map of resources (Farr et al., 2020 ) and reflective questions (Davies et al., 2020 ), freely available to support co-produced research.

This article explores the extent to which these multidisciplinary lessons can help us transform knowledge production in more equitable ways, outlining our learning from this project. First, we overview some conceptual issues with the use of the word ‘co-production’. We then discuss key matters raised in our interdisciplinary workshops: ‘Who is involved and when in co-produced research?’; ‘Power dynamics within health and social care research’; and ‘Communication and relationships’. We conclude by highlighting that bringing co-production principles into the real research world is fraught with difficult and messy compromises. Researchers (often lower in the academic hierarchy) may be caught up in battling systems and policies to enable co-production to happen, especially where they attempt to address issues of power and control within the research process.

Box 1: INVOLVE a Definitions and principles of co-produced research (Hickey et al., 2018 )

‘ Co-producing a research project is an approach in which researchers, practitioners and the public work together, sharing power and responsibility from the start to the end of the project, including the generation of knowledge ’ (p. 4).

Principles include:

Sharing power where research is owned by everyone and people are working together in more equal relationships

Including all perspectives and skills to ensure that everyone who wants to make a contribution can do so, with diversity, inclusiveness and accessibility being key

Respecting and valuing the knowledge of everyone , with everyone being of equal importance, and benefitting from the collaboration

Reciprocity and mutuality , building and maintaining relationships and sharing learning

Understanding each other with clarity over people’s roles and responsibilities.

a INVOLVE supported active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research, with a new NIHR Centre for Engagement and Dissemination (CED) launched in April 2020.

The concept of co-production

The NVOLVE co-production principles (Box 1 ) (Hickey et al., 2018 ) build on public policy co-production literature (Boyle and Harris, 2009 ; Staniszewska et al., 2018 ), which explores how service users can take an active role within the provision of public services (Brudney and England, 1983 ; Ostrom, 1996 ). A key premise is that service users have a fundamental role in producing services and outcomes that are important to them (Brandsen and Honingh, 2016 ). While in our project we particularly wanted to focus on ways of sharing power with service users and public contributors, defining who is involved in co-produced research varies across disciplines. The active involvement of service users/members of the public has sometimes been lost in research that is labelled as co-produced. UK funding councils such as the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) talk of co-produced research as developed between academic and non-academic organisations or communities (Campbell and Vanderhoven, 2016 ; ESRC, 2019 ). In health services research, authors have used the non-specific language of ‘stakeholders’ (Oliver et al., 2019 ). Sometimes the main research co-production partner has been practitioners (Heaton et al., 2016 ) and service users have been relegated to ‘context’ (Marshall et al., 2018 ), rather than being active agents and partners. This obfuscation of the role of service users/ members of the public in co-production is detrimental to the drive for inclusivity, democratisation and equity within co-produced research, which addresses the needs of service users/ marginalised citizens (Williams et al., 2020 ), overlooking the long political history of demands from service users to be more democratically involved in health and social care services and research (Beresford, 2019 ).

In our project, we particularly wanted to focus on how to equalise relationships with service users and public contributors (defined above) within co-produced research. The egalitarian and democratic principles of co-production means that service users, who may have been marginalised and are on the receiving end of professional ‘expertise’, now become equal partners in research (Williams et al., 2020 ). Best practice in co-produced research remains contested, with a significant theory-practice gap (Lambert and Carr, 2018 ). We wanted to understand what practices and resources could help bring principles into practice, when we are working within a context of structural inequalities.

Who is involved and when in co-produced research?

INVOLVE states that co-production should ‘occur from the start to the end of the project’ (Hickey et al., 2018 ) (p. 4). The principle to ‘include all perspectives and skills—make sure the research team includes all those who can make a contribution’ (Hickey et al., 2018 ) (p. 4) can be highly aspirational.

In our interdisciplinary workshops we discussed how there is often a lack of funding to pay public contributors to help develop a funding application. Formative ideas about research priorities and design can often be made by researchers before other people are involved. Our workshop discussions noted that involving all stakeholders who potentially have an interest in a project could be a very large and diverse group. It would be difficult to involve everyone, and this could be in tension with the idea that smaller groups can work better together. There are usually practical constraints on team numbers, budgets to pay for public contributors’ time and project scale and size. A tension can exist between the number of people you can viably include, and the diversity of the group you are working with. More generally, workshop participants highlighted problematic issues of claims to representation, where people within a co-production group need to be aware that they don’t speak for everyone—not even everyone in a group they are there to ‘represent’—and there was a need to look for opportunities to draw other perspectives in.

Workshop discussions included that when public contributors join a project there is a need to support people to take on different roles, and for people to also have choice and work from their strengths, rather than assuming that everyone has to do everything. Some group members may feel they lack skills or expertise in particular areas, and so may need training, support and mentoring. There may also be assumptions about who is going to do what work, which may need to be explicitly discussed and agreed. Ensuring proper payment of public contributors is an essential element of co-production. If public contributors are going to collect research data, they need appropriate payment, contracts and to follow all research governance processes. Within UK National Health Service (NHS) research that may mean having Research Passports, Good Clinical Practice training and Disclosure and Barring Service checks, if they are working with vulnerable people or children. Not all these processes are designed for public contributors, they can be potentially problematic to navigate, and researchers may need to support public contributors through this process. Table 1 summarises some of the challenges around who is involved, and when in co-produced research, and potential practices and resources that may help.

Power dynamics within health and social care research

Theoretical perspectives on power.

Critical and interdisciplinary perspectives on power can help us understand how to facilitate more equitable partnerships within research and co-produced work (Farr, 2018 ; Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ). The first principle of co-production is to share power through ‘an equal and reciprocal relationship’ between professionals and people using services (Boyle and Harris, 2009 ) (p. 11). However, several authors highlight how co-production can be a rhetorical device to hide power and social inequities (Flinders et al., 2016 ; Thomas-Hughes, 2018 ). Using Lukes ( 2005 ) dimensions of power, Gaventa ( 2007 ) conceives that power can be visible (institutions, structures, resources, rules), hidden (agenda-setting, some voices more dominant within decision-making), or invisible (embedded in beliefs and language).

Focussing first on visible aspects, structural and resource issues can impinge on people’s ability to co-produce, for example funders’ top-down control of research priorities and funding streams, alongside NHS and government political priorities. University research environments can be competitive, ‘unkind and aggressive’, which can crowd out ‘collegiality and collaboration’ (WellcomeTrust, 2020 ), exactly the kind of principles that academics are being encouraged to adopt through co-production. Traditional research frameworks are ill-fitted to the challenges of transforming power and control that are needed for co-productive practice (Lambert and Carr, 2018 ). Power hierarchies are intrinsic to research processes, with people experiencing competing expectations (from public contributors and communities, co-researchers, colleagues and institutions) when working in this way (Lenette et al., 2019 ). How do researchers create co-production circles of equality, reciprocity and share power with public contributors, when often researchers themselves are on temporary contracts and subject to the pressures of publishing, funding, impact and self-promotion within ‘toxic’ (Wellcome Trust, 2020 ) competitive structures? Understanding who is involved and how in decision-making processes (hidden aspects of power) is essential to understand how power is exercised. However, political scientists have long ago illustrated that ‘even the most internally democratic small collectives cannot in fact achieve equality of power in their decisions’ (Mansbridge, 1996 , p. 54).

Scrutinising invisible aspects of power, power can be seen to operate through knowledge, social relations and the language we use (Foucault, 1977 ). The principle of respecting and valuing the knowledge of all (Hickey et al., 2018 ) can be challenging in a healthcare context where a knowledge hierarchy with traditional positivist epistemological assumptions values an ‘unbiased, objective’ position. Co-productive approaches can be grounded in critical theory (Bell and Pahl, 2018 ; Facer and Enright, 2016 ), as opposed to traditional scientific paradigms. The experiential contextualised and tacit knowledge of people who use services, and related qualitative and participatory action methods, can be valued less than knowledge derived from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). This increases the challenge of co-production, as the values and methods of health and social care research may align less with co-production principles. Indeed the very idea that co-production and the sharing of power can actually happen within mainstream University spaces has been contested, with Rose and Kalathil ( 2019 ) arguing that Eurocentric hierarchical institutions that privilege rationality and reason will never be coming from a place where different knowledges are valued equally.

Understanding power in practice

In our project it was difficult to maintain a focus on power relations in the face of a strong tendency to emphasise practicalities, highlighting the difficulties of bringing these issues into clearer focus. An analysis of power dynamics may be an important aspect of a sociological study, but not one considered of such importance within health and social care research.

Focussing first on visible, structural aspects of power, workshop participants discussed their experience that within research that is formally ‘owned’ by a University (i.e., the Principal Investigator (PI) legally responsible for the project is situated within a University) there are associated issues of accountability and formal responsibility for delivering a funded research project. This creates constraints where projects have to deliver what is described rather than what emerges from the co-production process. How a PI works to develop a collaborative leadership style is an under-researched area. Within our own project we all held some unspoken assumptions about leadership and ensuring progress toward our project objectives. Workshop participants highlighted that organisational systems may not support co-production (e.g., finance, human resources and funding systems) so researchers may have to be tenacious to advocate for system changes in order to achieve things, which can be frustrating and time-consuming. For these myriad reasons, realistic resourcing of researcher time for co-production is needed, and many researchers may still end up putting discretionary time into projects to make co-production a success. There are few tools to help researchers avoid or alleviate risks to themselves and their stakeholders, such risks including practical costs, personal and professional costs to researchers, and costs to stakeholders (Oliver et al., 2019 ).

In relation to decision-making, workshop participants noted that in a pragmatic sense, doing everything by committee and consensus can impede project progress, as no decisions can be made until everyone is present at meetings. Even if decisions are made with everyone present, the power dynamics between people does not necessarily ensure that decisions are shared and agreed by everyone. Within our own project, where we were trying to stick to the principles of co-production, we found that we often had discussions between paid staff members outside of team meetings where thinking was developed and decisions taken. If public contributors are without employment contracts and are not working alongside other staff, there is potential for them to be excluded from informal discussions and decisions in day-to-day tasks. In our workshops there were discussions about whether researchers needed to ‘get out of the way’ and ‘sit on their hands’ in order to make space for others. We discussed how to practically create space for diverse knowledge and skills to be shared and considered whether it is possible to identify shared interests or if there is always a political struggle for power.

Through our project, we reflected as a team how assumptions and practices of how we do healthcare research may be deeply embedded within academic cultures. This links with Foucault’s perspectives on power dynamics (Foucault, 1977 ), every act and assumption we make is imbued with power, which makes power particularly hard to observe, grasp, critique, challenge and transform. We all have subconscious beliefs and work within cultural assumptions, thus continual critical reflective practice, and constant attention to fluctuating power relations is needed (Farr, 2018 ; Bell and Pahl, 2018 ). In workshops, suggested ways to address cultural issues included harnessing the current trends for co-production and using this to start challenging engrained cultures and accepted ways of doing things. Current funder prioritisation of co-production can enable senior researcher support for co-production, as organisational leaders recognise the cultural capital of the word and practices of ‘co-production’. Raising awareness of NIHR and other policy commitments to co-production may be a useful influencing strategy to engage more senior staff, as organisational support can be crucial to facilitate co-production. However, there is always the risk of tokenism and rhetoric (Flinders et al., 2016 ; Thomas-Hughes, 2018 ).

We considered within our project that the relationships between personal experiential knowledge, practice-based knowledge of healthcare staff, and dominant healthcare research need to be better understood if we are to co-produce knowledge together. We reflected on whether the aim of co-production projects is to modify the knowledge hierarchy completely, or to bring in experiential expertise/lived experience to influence the knowledge production process so the knowledge produced is more practical/effective/implementable. This second, more limited aim of making evidence more co-productively, so that it is more useful in practice may be more achievable, whereas modifying the dominant knowledge hierarchy was beyond our scope and influence.

Communication and relationships

The above dimensions of power (Lukes, 2005 ) have been augmented and brought together into a broader theoretical framework (Haugaard, 2012 ), which also incorporates ‘power with’ (Arendt, 1970 ), where emancipatory power can be harnessed through our ‘capacity to act in concert’. Arendt’s work highlights how we can collectively use our power together in more empowering ways. This links with a key principle of co-production, reciprocity, where everyone benefits from working together.

Consideration of what different team members want from working together, and therefore what reciprocity means within a project is needed. We discussed in the interdisciplinary workshops how the kind of benefits wanted by public contributors might include developing skills, confidence and work experience, and meeting such expectations may not usually be considered as research aims. Through our project we saw how co-production is strongly reliant on good communication and relationships. Strong facilitation and chairing skills are needed within meetings, to encourage everyone to contribute and challenge unhelpful behaviours, e.g., using jargon, or one person speaking a lot to the exclusion of others. People in our workshops discussed how some public contributors might need additional support to get more involved, e.g., having pre-meetings to help people get to grips with some information and/or issues, or the provision of materials in different accessible formats. If a co-production project includes people with specific communication needs, the group may need additional time and skills to be able to offer ways of working that are suitable for all. The NIHR is encouraging researchers to involve communities and groups that are often excluded. This means more outreach work to go out and meet with people in the places that they find accessible and comfortable, which can include project meetings in community locations, which may require additional resources.

Developing relationships and trust between team members may take time and requires emotional work. In our workshops we discussed how if the public contributor role includes sharing personal experiences for the benefit of the project, then researchers may also need to drop the ‘professional’ mask and share more personally and expose their own vulnerabilities (Batalden, 2018 ) to support more equal relationships. The challenges of university structural hierarchies were also discussed, including how it was often the responsibility of more ‘junior’ (i.e., lower in the hierarchy) researchers, and often women, to do the relational work (Lenette et al., 2019 ). Senior researchers do not necessarily understand the implications of co-production, for example one person shared how their Principal Investigator assumed that having a public contributor on the team would increase capacity and speed work up, unappreciative of the extra time needed for support, training and communication, including at the weekends, when public contributors could be carrying out work. Meeting the support and learning needs of team members can be challenging, both for researchers and public contributors, as co-produced research may take researchers outside the skills and knowledge usually expected in their professional environment. Even when these needs within a co-production project are recognised, research funders may not understand the resource and capacity implications.

A key element of running a co-production project identified within our work was the ongoing need for time to reflect on group processes to support and maintain different ways of working. Finding time for reflection can be challenging alongside creating an environment where everyone can honestly reflect on what it’s like to be in the group. This requires strong facilitation skills, particularly if there are tensions and conflicts. Addressing communication and relationship challenges are key to developing and sustaining a sense of shared ownership, and we outline some helpful practices in Table 2 .

Reflections on our own attempts at co-production

The conception of our project came initially from conversations between a researcher and public involvement specialist with previous experience as a service user and user-controlled research, wanting to create a space to share interdisciplinary learning between everyone about co-production. It could be argued that as the generation of the idea did not include public members in this first discussion it was not truly co-produced. We acknowledged that there were gaps between the lessons our project produced, and how the project itself had been carried out. It was very challenging to implement all INVOLVE principles (Hickey et al. 2018 ), and we question the extent to which they can ever be fully realised within our current contexts. Practically, we found that we should have allocated more resources to payment of our public contributors to take on additional roles. A focus on relationships and reflection was hard to maintain in the face of a small group trying to deliver an ambitious project to time, alongside other competing commitments. However, in our own reflective discussions we acknowledged that a sense of ongoing commitment to the project from everyone felt key to our group process and successfully getting the project done. In writing this article we met together several times to plan and develop sections, tables and points we wanted to get across. However, the actual writing tended to fall to the academics and public involvement specialist, who had more of the technical knowledge of what was expected. Demands of time, the juggling of commitments, and lack of resources meant that writing the article was not truly ‘co-produced’. Indeed, through the process, a public contributor co-author said they found the reviewers’ comments ‘a bit overwhelming’, with uncertainty of how to approach this. Another public contributor co-author expressed similar experiences with reviewers comments on another paper they had previously co-authored. The publication process can be a challenge to researchers as well, who are more familiar with these traditional academic practices.

Sharing power in the face of embedded hierarchies and inequalities is an obvious challenge for co-production. The gap between co-production principles and practice is a tricky territory. Working with everyone who is interested in an issue, having a focus on meeting the priorities of communities and people we work with, and co-producing all aspects of a project from beginning to end will be difficult to deliver in many projects in health and social care research. Working directly with members of the public is likely to require more adaptation of research project processes and to ‘usual ways of doing things’, alongside additional time and resources. People have different skills and uneven access to resources, and people may need considerable training and support to work together more equally. However, our experience is that funders do not necessarily understand this and doing co-production on a small budget can be particularly challenging. Time investment and the emotional work required to build relationships necessary for successful co-production is both under-appreciated and under-resourced. This reflects disparities in power between those who do this work and those who hold most power in universities. Recognising, recording, documenting and consistently budgeting for this work may help to make it more visible. Timing of funding is also crucial as many research teams do not have access to institutional ‘core’ funding, or seed funding grants, for public contributor involvement at the research development stage. As it is unlikely that most co-production projects will be able to include people with all the relevant perspectives and skills it is important to actively discuss and agree who can be involved and to be open about and discuss restrictions, which can be an act of power in itself.

Oliver and Boaz ( 2019 ) want to ‘open the door’ to more critical multidisciplinary accounts of evidence production and use, highlighting that some people want to direct energies to democratise knowledge for all. Interdisciplinary lessons from this project question the extent to which co-production processes can enable this, given the challenges we have highlighted. We consider that the jury is still out on the viability of co-production in the context of health and social care research. While some (Rose and Kalathil, 2019 ) find the promise of co-production untenable in mental health, we hope we can find a meaningful way forward. However, ‘putting what we already know [about co-production] into practice’ (Oliver and Boaz, 2019 ) can be very challenging. Our own experiences led us to reflect that to be working toward co-production principles means that you have to consistently be challenging ‘business as usual’—we consider a key point here is how to maintain sufficient self and team support to keep trying to do this in practice. Establishing reflective processes that encourage consideration of power issues are likely to be essential. Our approach to help ourselves and others navigate the challenges of co-production has been to identify ways in which groups can start to address power issues as highlighted in Tables 1 and 2 , and to develop practical freely available outputs including a map of resources and reflective questions (Farr et al., 2020 ; Davies et al., 2020 ). We need to understand more about how effective these strategies are, and whether co-production really does make a difference to the use of research. We need to encourage honest reporting of projects, their outcomes and the balance between the benefits and challenges of trying to implement the principles. However, power structures may mitigate against reporting of challenges and problems in research. Other research gaps include understanding what projects will benefit most from a co-production approach. Can co-production deliver more practical and implementable research findings, and if so how? How do we best challenge and change some of the structural inequalities within academia that impede co-production (Williams et al., 2020 )? How do we integrate experiential, practice and research-based knowledge to improve health and social care?

Our experiences on this project highlight the ongoing challenges to truly put the principles of co-production into practice. During this project we used the phrase ‘I am always doing what I can’t do yet in order to learn how to do it’ (van Gogh, 1885 ), to illustrate our limitations, yet continual striving toward an ideal. The quote continues ‘…I’ll end by saying that the work is difficult, and that, instead of quarrelling, the fellows who paint peasants and the common people would do wisely to join hands as much as possible. Union is strength…’ (van Gogh, 1885 ). Forgiving the dated language and connotations of this quote, the principles of joining hands and facilitating union are important co-production ideals that we continually need to remember, relearn and put our hearts into practising.

Arendt H (1970) On violence. Allen Lane, Penguin, London

Google Scholar

Batalden P (2018) Getting more health from healthcare: quality improvement must acknowledge patient coproduction—an essay by Paul Batalden. BMJ 362:k3617. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k3617

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bell DM, Pahl K (2018) Co-production: towards a utopian approach. Int J Soc Res Methodol 21(1):105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1348581

Article Google Scholar

Beresford P (2019) Public participation in health and social care: exploring the co-production of knowledge. Front Sociol 3(41). https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2018.00041

Boyle D, Harris M (2009) The challenge of co-production. New Economics Foundation, London

Brandsen T, Honingh M (2016) Distinguishing different types of coproduction: a conceptual analysis based on the classical definitions. Publ Admin Rev 76(3):427–435. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12465

Brudney JL, England RE (1983) Toward a definition of the coproduction concept. Publ Admin Rev 43(1):59–65. https://doi.org/10.2307/975300

Campbell HJ, Vanderhoven D (2016) N8/ESRC research programme. Knowledge that matters: realising the potential of co-production. N8 Research Partnership, Manchester, https://www.n8research.org.uk/media/Final-Report-Co-Production-2016-01-20.pdf . Accessed 23 Mar 2021

Davies R, Andrews H, Farr M, Davies P, Brangan E, Bagnall D (2020) Reflective questions to support co-produced research. National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ARC West and People in Health West of England, University of Bristol and University of West of England. http://bit.ly/CoProResources . Accessed 23 Mar 2021

ESRC (2019) Guidance for collaboration. Economic and Social Research Council. https://esrc.ukri.org/collaboration/guidance-for-collaboration/ . Accessed 29 Nov 2020

Facer K, Enright B (2016) Creating Living knowledge: the connected communities programme, community-university relationships and the participatory turn in the production of knowledge. University of Bristol/ AHRC Connected Communities, Bristol

Farr M (2018) ‘Power dynamics and collaborative mechanisms in co-production and co-design processes’. Crit Social Policy 38(4):623–644. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018317747444

Farr M, Davies R, Davies P, Bagnall D, Brangan E, Andrews H (2020) A map of resources for co-producing research in health and social care. University of Bristol and University of West of England, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) ARC West and People in Health West of England http://bit.ly/CoProResources . Accessed 23 Mar 2021

Flinders M, Wood M, Cunningham M (2016) The politics of co-production: risks, limits and pollution. Evid Policy 12(2):261–279. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426415X14412037949967

Foucault M (1977) Discipline and punish: the birth of the prison. Allen Lane, London

Gaventa J (2007) Levels, spaces and forms of power: analysing opportunities for change. In: Berenskoetter F, Williams MJ (eds) Power in world politics. Routledge, Abingdon, pp. 204–224

Haugaard M (2012) Rethinking the four dimensions of power: domination and empowerment. J Polit Power 5(1):33–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2012.660810

Heaton J, Day J, Britten N (2016) Collaborative research and the co-production of knowledge for practice: an illustrative case study. Implement Sci 11(1):20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0383-9

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hickey G, Brearley S, Coldham T, Denegri S, Green G, Staniszewska S, Tembo D, Torok K, Turner K (2018) Guidance on co-producing a research project. INVOLVE, Southampton

INVOLVE (2019) Co-production in action: number one. INVOLVE, Southampton

Lambert N, Carr S (2018) ‘Outside the Original Remit’: Co-production in UK mental health research, lessons from the field. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 27(4):1273–1281

Lenette C, Stavropoulou N, Nunn C, Kong ST, Cook T, Coddington K, Banks S (2019) Brushed under the carpet: examining the complexities of participatory research. Res All 3(2):161–179. https://doi.org/10.18546/RFA.03.2.04

Lukes S (2005) Power: a radical view. Macmillan, London

Book Google Scholar

Mansbridge J (1996) Using power/ fighting power: the polity. In: Benhabib S (ed.) Democracy and Difference. Princeton University Press, Princeton, pp. 46–66

Marshall M, Mear L, Ward V, O’Brien B, Davies H, Waring J, Fulop N (2018) Optimising the impact of health services research on the organisation and delivery of health services: a study of embedded models of knowledge co-production in the NHS (Embedded). NIHR. https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/165221/#/ . Accessed 23 Mar 2021

NIHR CED (2020) Centre for engagement and dissemination recognition payments for public contributors. https://www.nihr.ac.uk/documents/centre-for-engagement-and-dissemination-recognition-payments-for-public-contributors/24979#1 . Accessed 23 Mar 2021

Oliver K, Boaz A (2019) Transforming evidence for policy and practice: creating space for new conversations. Pal Commun 5(1):60. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-019-0266-1

Oliver K, Kothari A, Mays N (2019) The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? J Health Res Policy Syst 17(1):33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3

Ostrom E (1996) Crossing the great divide: coproduction, synergy, and development. World Dev 24(6):1073–1087. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(96)00023-X

Rose D, Kalathil J (2019) Power, privilege and knowledge: the untenable promise of co-production in mental “health”. Front Sociol 4:57. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00057

Staniszewska S, Denegri S, Matthews R, Minogue V (2018) Reviewing progress in public involvement in NIHR research: developing and implementing a new vision for the future. BMJ Open 8(7):e017124. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017124

Thomas-Hughes H (2018) Ethical ‘mess’ in co-produced research: reflections from a U.K.-based case study. Int J Soc Res Methodol 21(2):231–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2017.1364065

van Gogh V (1885) RE: Letter from Vincent van Gogh to Anthon Van Rappard

WellcomeTrust (2020) What researchers think about the culture they work in. Wellcome Trust, London, https://wellcome.org/sites/default/files/what-researchers-think-about-the-culture-they-work-in.pdf . Accessed 23 Mar 2021

Williams O, Sarre S, Papoulias SC, Knowles S, Robert G, Beresford P, Rose D, Carr S, Kaur M, Palmer VJ (2020) Lost in the shadows: reflections on the dark side of co-production. Health Research Policy and Systems 18 (1)

Download references

Acknowledgements

This project was funded by the University of Bristol Public Engagement Seed Funding and Research Staff Development fund. It was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Applied Research Collaboration West (NIHR ARC West). The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care. Many thanks to everyone who attended our workshops, got involved in and supported the project to help us develop our resources and training. We couldn’t have done this with you!

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

The National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration West (NIHR ARC West) at University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust, Bristol, UK

Michelle Farr, Philippa Davies, Heidi Andrews, Darren Bagnall, Emer Brangan & Rosemary Davies

Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

Michelle Farr, Philippa Davies, Heidi Andrews, Darren Bagnall & Emer Brangan

School of Health and Social Wellbeing, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK

Emer Brangan

Faculty of Health and Applied Sciences, University of the West of England, Bristol, UK

Rosemary Davies

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Michelle Farr .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Farr, M., Davies, P., Andrews, H. et al. Co-producing knowledge in health and social care research: reflections on the challenges and ways to enable more equal relationships. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 8 , 105 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00782-1

Download citation

Received : 28 February 2020

Accepted : 31 March 2021

Published : 06 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00782-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Ready, set, co(produce): a co-operative inquiry into co-producing research to explore adolescent health and wellbeing in the born in bradford age of wonder project.

- Hannah Nutting

- Rosemary R. C. McEachan

Research Involvement and Engagement (2024)

Create to Collaborate: using creative activity and participatory performance in online workshops to build collaborative research relationships

- Alice Malpass

- Astrid Breel

- Michelle Farr

Research Involvement and Engagement (2023)

Coproducing health research with Indigenous peoples

- Chris Cunningham

- Monica Mercury

Nature Medicine (2023)

Patient and public involvement in an international rheumatology translational research project: an evaluation

- Savia de Souza

- Eva C. Johansson

- Ruth Williams

BMC Rheumatology (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

An official website of the Department of Health & Human Services

- Search All AHRQ Sites

- Email Updates

Informing Improvement in Care Quality, Safety, and Efficiency

- Contact DHR

Funded Projects

Since 2004, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Digital Healthcare Research Program has funded projects to develop an evidence base for how technology improves healthcare decision making, supports patient-centered care, and improves the quality and safety of medication management.

- Search AHRQ-Funded Projects

Search the entire portfolio of AHRQ-funded digital healthcare research projects. Projects can be identified by technology studied, medical condition, population, status of the project, principal investigator, organization, funding mechanism and location.

- AHRQ-Funded Projects Map

Identify AHRQ-funded digital healthcare research projects by clicking on a state.

- Director's Corner

- Current Priorities

- Executive Summary

- Research Spotlight

- Research Themes and Findings

- Research Dissemination

- Research Overview

- 2020 Year in Review

- 2019 Year in Review

- Engaging and Empowering Patients

- Optimizing Care Delivery for Clinicians

- Supporting Health Systems in Advancing Care Delivery

- Our Experts

- AHRQ Digital Healthcare Research Publications Database

- A Practical Guide for Implementing the Digital Healthcare Equity Framework

- ePROs in Clinical Care

- Guide to Integrate Patient-Generated Digital Health Data into Electronic Health Records in Ambulatory Care Settings

- Health IT Survey Compendium

- Time and Motion Studies Database

- Health Information Security and Privacy Collaboration Toolkit

- Implementation in Independent Pharmacies

- Implementation in Physician Offices

- Children's Electronic Health Record (EHR) Format

- Project Resources Archives

- Archived Tools & Resources

- National Webinars

- Funding Opportunities

- Digital Healthcare Research Home

- 2018 Year in Review Home

- Research Summary

- Research Spotlights

- 2019 Year in Review Home

- Annual Report Home

- Open access

- Published: 30 May 2018

Collaborative and partnership research for improvement of health and social services: researcher’s experiences from 20 projects

- M. E. Nyström 1 , 2 ,

- J. Karltun 3 ,

- C. Keller 4 &

- B. Andersson Gäre 5 , 6

Health Research Policy and Systems volume 16 , Article number: 46 ( 2018 ) Cite this article

45k Accesses

104 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

Getting research into policy and practice in healthcare is a recognised, world-wide concern. As an attempt to bridge the gap between research and practice, research funders are requesting more interdisciplinary and collaborative research, while actual experiences of such processes have been less studied. Accordingly, the purpose of this study was to gain more knowledge on the interdisciplinary, collaborative and partnership research process by investigating researchers’ experiences of and approaches to the process, based on their participation in an inventive national research programme. The programme aimed to boost collaborative and partnership research and build learning structures, while improving ways to lead, manage and develop practices in Swedish health and social services.

Interviews conducted with project leaders and/or lead researchers and documentation from 20 projects were analysed using directed and conventional content analysis.

Collaborative approaches were achieved by design, e.g. action research, or by involving practitioners from several levels of the healthcare system in various parts of the research process. The use of dual roles as researcher/clinician or practitioner/PhD student or the use of education designed especially for practitioners or ‘student researchers’ were other approaches. The collaborative process constituted the area for the main lessons learned as well as the main problems. Difficulties concerned handling complexity and conflicts between different expectations and demands in the practitioner’s and researcher’s contexts, and dealing with human resource issues and group interactions when forming collaborative and interdisciplinary research teams. The handling of such challenges required time, resources, knowledge, interactive learning and skilled project management.

Conclusions

Collaborative approaches are important in the study of complex phenomena. Results from this study show that allocated time, arenas for interactions and skills in project management and communication are needed during research collaboration to ensure support and build trust and understanding with involved practitioners at several levels in the healthcare system. For researchers, dealing with this complexity takes time and energy from the scientific process. For practitioners, this puts demands on understanding a research process and how it fits with on-going organisational agendas and activities and allocating time. Some of the identified factors may be overlooked by funders and involved stakeholders when designing, performing and evaluating interdisciplinary, collaborative and partnership research.

Peer Review reports

Healthcare organisations are complex and knowledge intensive, with patients often taking for granted that care providers use the best available knowledge on diagnosis and treatment. Evidence-based medicine and practice ensure that the best available knowledge is used systematically in clinical care (e.g. [ 1 ]). Nevertheless, the gap between research and practice in healthcare is well-known and a recognised concern (e.g. [ 2 , 3 ]), where failures to translate research into practical actions contribute to health inequities [ 4 , 5 ]. The process from research-produced knowledge to its use in healthcare practices can take considerable time (e.g. [ 6 ]). The estimated lack of research use in the United States and the Netherlands has suggested that 30–40% of patients do not receive care complying with current research evidence [ 7 ]. The required increase in the speed of uptake of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines has been frequently discussed (e.g. [ 8 ]) and factors influencing their adoption have been extensively studied (e.g. [ 9 , 10 ]). Getting research into policy and practice in healthcare is a recognised, world-wide concern (e.g. [ 11 ]).

Several research areas deal with aspects related to the transfer of knowledge and use of research findings for improving healthcare. The view of research production as separate from the use of research findings initially inspired research on diffusion and implementation processes [ 12 , 13 ], mainly focusing on the later stages of the research process with variable emphasis on a division between knowledge production and its implementation.

The shortcomings of the traditional ‘linear’ model of research-into-practice have become more evident [ 14 ]. Van de Ven and Johnson [ 15 ] suggest that the problem may be one of methods for knowledge production rather than knowledge transfer or knowledge translation. To enhance a faster and more systematic use of knowledge, collaborative and interdisciplinary research approaches have been asked for as well as more useful research [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]. Research collaboration is assumed to enable and enhance both the use of research and increase the amount of research relevant to end users.

Research on knowledge transfer and exchange describes an interactive exchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers [ 18 , 19 ]. Knowledge transfer and exchange interaction between researchers and practitioners can take place from the on-set of the research process and involve more long-standing relationships. Several approaches to knowledge transfer have been described, focusing, for example, on systematic synthesis and guidelines, social interaction between researchers and decision-makers, contextual features and organisational readiness [ 20 ]. The Canadian Institute of Health Research uses the term ‘integrated knowledge translation’ to describe projects where the knowledge users are involved as equal partners during the entire research process [ 21 , 22 ].

Funding organisations have started to request research proposals to include researcher–decision-maker partnerships in collaborative research teams with representatives of industry, local communities and professional organisations (e.g. [ 23 , 24 ]). The increased focus on research-use is also mirrored in research funders’ strategies (e.g. [ 25 ]). Some examples of collaborative initiatives are the Partnership projects and Centres financed by the National Health and Medical Research Council in Australia, the Dutch Academic Collaborative Centres for Public Health in the Netherlands, and The Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care in the United Kingdom (e.g. [ 26 ]), as well as the practice-based research networks and structured use of practice facilitators [ 27 , 28 ] and the Integrated Delivery Systems Research Network programme to foster public–private collaboration between health service researchers and healthcare delivery systems in the United States [ 29 ]. There are three main strategies that research funding agencies might use to enhance knowledge translation – push, pull, or linkage and exchange. The push–pull strategies distinguish between mechanisms driven by science (push) and those driven by the demands of practitioners or policy-makers (pull) [ 30 ]. The linkage and exchange model is based on co-construction of applied knowledge and the relevance of applied research to both practitioners and researchers [ 31 ]. In a recent review of the ways research funding agencies support science integration into policy and practice in the field of health [ 30 ], most of the 13 agencies investigated used one or two of these strategies. The large heterogeneity of users and how this may affect the use of various mechanisms for research initiation, development and dissemination was highlighted in this review.

Collaboration has been addressed for some time in community-based participatory research regarding public health and social issues in society (e.g. [ 32 , 33 ]), for example, on how to achieve policy level collaboration (e.g. [ 24 , 34 ]) and evidence-informed policy-making (e.g. [ 35 ]). Nevertheless, there is a need for more empirical research on the actual processes, conditions and outcomes of the more recent collaborative and partnership research initiatives in healthcare [ 36 , 37 ] and, to date, there are few empirical studies on researchers’ approaches and experiences of the combination of interdisciplinary and collaborative and partnership research, including the actual effect of such programme or project calls. Less explored is also research partnership aiming to respond to the challenges and priorities of the health system and much research has been based on assumptions of researcher-driven initiatives with newly established collaborations [ 38 ].

Collaborative and partnership research

Approaches, strategies and roles.

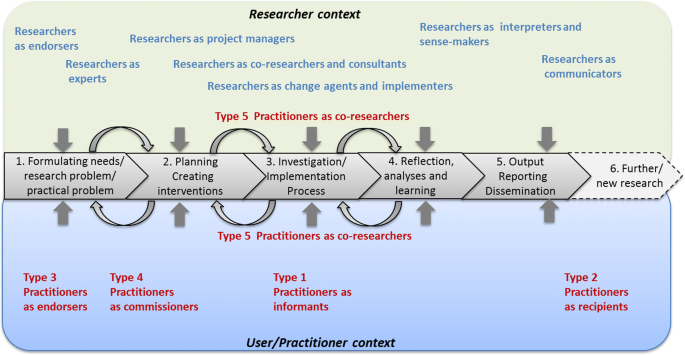

Collaboration and partnerships are two concepts used to describe the involvement of people and groups from different contexts and with different experiences, perspectives and agendas in research and development. Accordingly, collaborative research contains social relations and a variation of potential roles for those involved during the research process. In earlier research, means for collaboration were described in the form of ‘linkage mechanisms’ between researcher and user contexts, i.e. the presence of intermediaries (boundary spanners); formal and informal contacts with users during studies; involvement of users during data collection; and interim feedback [ 39 ]. The boundary-spanning role of knowledge brokers has been brought forward as a bridge between research and practice (e.g. [ 40 ]). Knowledge brokering has been defined as “ all the activity that links decision-makers with researchers, facilitating their interaction so that they are able to better understand each other’s goals and professional cultures, influence each other’s work, forge new partnerships, and promote the use of research-based evidence in decision-making ” ([ 40 ], p. 131). Individuals, teams or organisations can all play the role of knowledge brokers [ 41 , 42 ]. Michaels [ 43 ] describes six primary brokering strategies that span from more passive dissemination of information, interaction by seeking and using expert’s advice and linking different actors, to active engagements and close collaborative relations with healthcare actors, and which aim to inform, consult, match-make, engage, collaborate and build capacity. A recent study highlights the importance of effective ‘relationship brokering’ in researcher-health system partnership for establishing a meaningful collaboration [ 38 ].

A detailed road map on research collaboration is offered by Martin [ 44 ] in his description of five approaches to co-production of research. Depending on the chosen approach, stakeholders can be more or less involved in phases of the research process, from study design, data collection and analyses, to dissemination, while the degree of academic independence of the researcher/s and the utilisation of the research results may vary. Consequently, practitioners can play the role of informants, recipients, endorsers, commissioners or co-researchers.

On programme level, King et al. [ 45 ] describe four research programme operating models used in a collaborative approach to enhance research-informed practice in community-based clinical service organisations. The models describe the types of partnership involved such as the ‘clinician-researcher skills development model’, ‘clinician and researcher evaluation model’, ‘researcher-led evaluation model’, and the ‘knowledge-conduit model’. To differentiate research-practice partnerships from other ways of conducting research, Øvretveit et al. [ 46 ] suggest five criteria for partnership research, namely research that contributes to actions taken by actors within a health system; studies intended to produce quick and actionable findings as well as scientific publications; both researchers and practitioners take part in defining the research question and interpret findings; significant time and contributions from both researchers and practitioners; and an extensive formulated description of the partnership approach.

Challenges and enabling features

One challenge for collaborative and partnership research concerns the variation of views on the production and use of knowledge and on the relationship between researcher and practitioner, spanning from top-down to bottom-up or from linear to interactive and multidimensional (e.g. [ 39 , 47 ]). Depending on research tradition and/or experiences, basic assumptions regarding knowledge and learning can vary among researchers, but also among stakeholders (e.g. [ 48 ]). Sibbald et al. [ 49 ] identified challenges such as role clarity, organisational change and cultural differences regarding expectations on research output and (positive) effects on actual practice and found that role ambiguity, multiple roles and role conflicts could hamper social relationships. Factors facilitating collaboration were already established relationships, the alignments of goals/objectives, skilled and experienced researchers, and the use of regular, multi-modal communication.

Another influence on collaboration, mainly from the researcher context, is the variety of research paradigms and areas and related basic assumptions. One approach to be expected is action research, where knowledge creation is combined with practice development. There are a variety of action research approaches depending on, for example, how the collaborative element is organised [ 50 ]. The interactive research approach builds on action research and emphasises the common learning and knowledge creation for both practitioners and researchers during the complete process [ 51 ]. Both approaches involve a number of different roles for the researcher to enact [ 52 ].

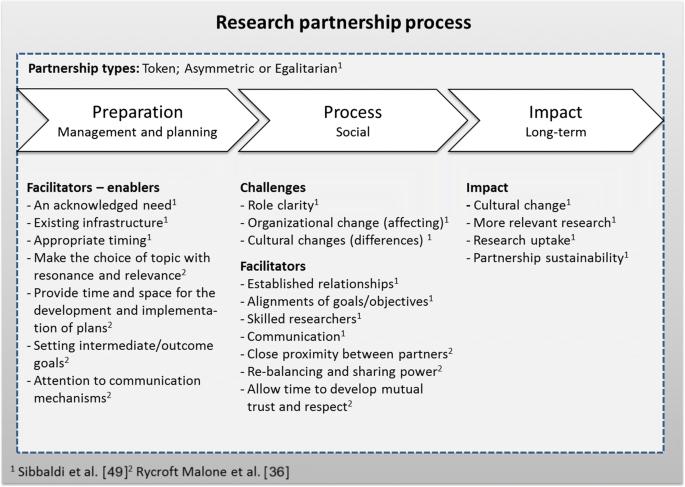

Based on a realist evaluation, Rycroft-Malone et al. [ 36 ] list features of research collaboration likely to enhance knowledge use, namely attention to communication mechanisms, setting intermediate/outcome goals, providing time and space for the development and implementation of plans, making the choice of topic with resonance and relevance, close proximity between partners, re-balancing and sharing power, and allowing time to develop mutual trust and respect. These features put other demands on the planning and execution of research than a traditional approach when research has precedence over practice.

Sibbald et al. [ 49 ] present a model describing the research partnership process, with enablers, facilitators, challenges and impact, and identify three partnership types based on an empirical study as token, asymmetric or egalitarian partnerships. In Fig. 1 , features of the research partnership process are presented, grounded on aspects highlighted by Sibbald et al. [ 49 ] and Rycroft Malone et al. [ 36 ].

Model over the research partnership process (adopted after Sibbald et al. [ 49 ] and Rycroft Malone et al. [ 36 ])

Collaborative and partnership research poses specific demands regarding project management. According to a review [ 53 ], collaborative research can be characterised by heterogeneity of actors, collective responsibilities, demands for applicability in addition to scientific requirements, and by being funded by public agencies with specific agendas. Project management in collaborative projects usually involves three paradoxes [ 53 ]: