- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis

Preview this book.

- Description

- Aims and Scope

- Editorial Board

- Abstracting / Indexing

- Submission Guidelines

Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis ( EEPA ) is the premier journal for rigorous, policy-relevant research on issues central to education. The articles that appear inform a wide range of readers—from scholars and policy analysts to journalists and education associations—working at local, state, and national levels. EEPA is a multidisciplinary journal, and editors consider original research from multiple disciplines, orientations, and methodologies.

Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis (EEPA) publishes manuscripts of theoretical or practical interest to those engaged in educational evaluation or policy analysis, including economic, demographic, financial, and political analyses of education policies, and significant meta-analyses or syntheses that address issues of current concern. The journal seeks high-quality research on how reforms and interventions affect educational outcomes; research on how multiple educational policy and reform initiatives support or conflict with each other; and research that informs pending changes in educational policy at the federal, state, and local levels, demonstrating an effect on early childhood through early adulthood.

- Clarivate Analytics: Current Contents - Physical, Chemical & Earth Sciences

- Contents Pages in Education (T&F)

- EBSCO: Sales & Marketing Source

- EBSCOhost: Current Abstracts

- ERIC (Education Resources Information Center)

- Educational Research Abstracts Online (T&F)

- ProQuest Education Journals

- Social SciSearch

- Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science)

- Wilson Education Index/Abstracts

All manuscripts should be submitted electronically at http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/eepa . For questions or inquiries contact [email protected] .

Publication Standards

Researchers submitting manuscripts should consult the Standards for Reporting on Research in AERA Publications and the AERA Code of Ethics .

Manuscript Style, Length, and Format

The style guide for all AERA journals is the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7 th edition.

Please follow these guidelines:

- Keep manuscripts to a maximum of 45 pages, including all tables, figures and endnotes. References are not included in the page count.

- Number the pages consecutively, beginning with the page after the title page.

- Double space your manuscript, and use 1-inch margins on all sides.

- Use 12-point Times New Roman only.

- Do not use footnotes . If you find that explanatory or amplifying information must be included in note form, use endnotes typed as normal text after the conclusion of the manuscript text. Notes should be numbered consecutively throughout the paper. Please do not use the endnotes feature of software programs as this makes typesetting difficult. Endnotes are included in the manuscript word count.

- Present data in figures and tables to clarify information for readers. Refer in the text to any figure or table so readers can find the supporting documentation.

- Place all figures and tables at the end of the text, and type figure captions on a separate page rather than with the original figures. This page is not counted in the manuscript length limit.

- Insert subheads at reasonable intervals to break the monotony of lengthy text. Use APA format for headings.

Appendices can only appear in the copyedited and typeset PDF if, with their inclusion, the article is still within the maximum page limit of 45 pages. Appendices themselves should exceed three pages. If the inclusion of appendices would make the article longer than 45 pages or they are longer than 3 pages, they can appear instead as online supplementary files.

Brief Format

EEPA also publishes Briefs. The Brief format can cover the range of paper topics normally considered for EEPA . Briefs will typically have much shorter introductions, literature reviews, and theoretical frameworks, and will focus primarily on the empirics.

Briefs will be held to the same rigorous standards for publication as any other submission. The review process will be the same, except that authors will receive no more than one “revise and resubmit” decision before a “reject” or “conditional acceptance/acceptance” decision is made. Authors may choose to submit a Brief for various reasons. For example, a study is a replication in a previously-studied area, and a lengthy literature review section is not needed; the research design does not necessitate a long set of robustness checks; or the topic is of immediate policy relevance and a shorter format may be more accessible to policymakers without sacrificing rigor.

Briefs should follow the following guidelines:

- Manuscripts should contain no more than 2500 words, excluding references.

- No more than three total figures or tables should be included.

- Pages should be numbered consecutively, beginning with the page after the title page.

- The manuscript should be double-spaced, with 1-inch margins on all sides.

- Only 12-point Times New Roman should be used.

- Footnotes or endnotes should not be used.

- Data should be presented in figures and tables to clarify information for readers. References should be made within the text to any figures or tables so readers can find the supporting material.

- All figures and tables should be placed at the end of the text, and figure captions should appear on a separate page rather than with the original figures. This page is not counted in the manuscript length limit.

- Subheads should be inserted at reasonable intervals to break the monotony of lengthy text. Use APA format for headings.

- Appendices can only appear online. Appendices can be used to provide any additional methodological information needed.

Submission Preparation Checklist

As part of the submission process, please check off your submission’s compliance with the requirements below. If your submission does not meet these requirements, it may be returned to you and delay consideration of your work.

- The submission has not been previously published and is not under consideration for publication elsewhere, or an explanation has been provided in the Cover Letter.

- THE MANUSCRIPT CONTAINS NO IDENTIFYING INFORMATION, EVEN ON THE TITLE PAGE. “Author” and publication year are used in any mention of the author’s work and in the bibliography and notes instead of author names, titles of works, etc. The author’s name has been removed from the document’s Properties, which in Microsoft Word is found in the File menu (select “File,” “Properties,” “Summary,” and remove the author’s name; select “OK” to save).

- The text conforms to APA style and the requirements stated above under “Manuscript Style, Length, and Format.”

- The submission is in Microsoft Word. Any supplemental files are in Microsoft Word, RTF, Excel, or PDF.

- All URL addresses in the manuscript (e.g., http://www.aera.net ) are activated and ready to click.

- An abstract of up to 120 words is included. Please also include at least 3-5 keywords, the terms that researchers will use to find your article in indexes and databases. A term may contain more than one word.

Checklist Once Your Manuscript is Accepted

- Submit one high-quality electronic version of each figure that is to be typeset.

Upload figures as individual files in the original version from the application the figure was created in. Figures must not be embedded in a Word doc.

Include only references cited in the text in your reference list. The author is responsible for the accuracy and completeness of the reference list.

Do not use underlining. Use sentence structure, not italics, to create emphasis; words to be set in italics should be typed in italics.

Spell out abbreviations and acronyms at first mention unless they are found as entries in their abbreviated form in Merriam-Webster’s Collegiate Dictionary, 11th ed., 2003 (e.g., “IQ” needs no explanation).

Clearly mark mathematical symbols and Greek letters to indicate italics, boldface, superscript, and subscript. Place any formulas or equations in an editable form rather than as text objects or pictures. We advise submitting all equations in Mathtype to ensure they are correctly formatted during typesetting.

Ensure the text includes a reference to any figure or table so readers look for the supporting documentation. Any table, formula, or figure must be in an editable form and should be included at the end of the manuscript text.

How to Get Help With the Quality of English in Your Submission

Authors who would like to refine the use of English in their manuscripts might consider using the services of a professional English-language editing company. We highlight some of these companies at http://www.sagepub.com/journalgateway/engLang.htm .

Please be aware that Sage has no affiliation with these companies and makes no endorsement of them. An author's use of these services in no way guarantees that his or her submission will ultimately be accepted. Any arrangement an author enters into will be exclusively between the author and the particular company, and any costs incurred are the sole responsibility of the author.

Copyright Information

No written or oral permission is necessary to reproduce a table, a figure, or an excerpt of fewer than 500 words from this journal, or to make photocopies for classroom use. Authors are granted permission, without fee, to photocopy their own material or make printouts from the final pdf of their article. Copies must include a full and accurate bibliographic citation and the following credit line: “Copyright [year] by the American Educational Research Association; reproduced with permission from the publisher.” Written permission must be obtained to reproduce or reprint material in circumstances other than those just described. Please direct all requests for permission or for further information on policies and fees to the journal’s Website at http://eepa.aera.net/ .

For authors who use figures or other material for which they do not own copyright:

Authors who wish to use material, such as figures or tables, for which they do not own the copyright must obtain written permission from the copyright holder (usually the publisher) and submit it along with their manuscript. (However, no written or oral permission is necessary to reproduce a table, a figure, or an excerpt of fewer than 500 words from an AERA journal.)

For authors of joint works (articles with more than one author):

This journal uses a transfer of copyright agreement that requires just one author (the corresponding author) to sign on behalf of all authors. Please identify the corresponding author for your work when submitting your manuscript for review. The corresponding author will be responsible for the following:

- Ensuring that all authors are identified on the copyright agreement, and notifying the editorial office of any changes in the authorship.

- Securing written permission (by letter or e-mail) from each co-author to sign the copyright agreement on the co-author’s behalf.

- Warranting and indemnifying the journal owner and publisher on behalf of all co-authors. Although such instances are very rare, you should be aware that in the event that a co-author has included content in his or her portion of the article that infringes the copyright of another or is otherwise in violation of any other warranty listed in the agreement, you will be the sole author indemnifying the publisher and the editor of the journal against such violation.

Please contact AERA if you have questions or if you prefer to use a copyright agreement for all coauthors to sign.

Privacy Statement

The names and e-mail addresses entered in this journal site will be used exclusively for the stated purposes of this journal and will not be made available for any other purpose or to any other party.

The Publications Committee welcomes comments and suggestions from authors. Please send these to the Publications Committee in care of the AERA central office.

Right of Reply

The right of reply policy encourages comments on recently published articles in AERA publications. They are, of course, subject to the same editorial review and decision process as articles. If the comment is accepted for publication, the editor shall inform the author of the original article. If the author submits a reply to the comment, the reply is also subject to editorial review and decision. The editor may allot a specific amount of journal space for the comment (ordinarily about 1,500 words) and for the reply (ordinarily about 750 words). The reply may appear in the same issue as the comment or in a later issue (Council, June 1980).

If an article is accepted for publication in an AERA journal that, in the judgment of the editor, has as its main theme or thrust a critique of a specific piece of work or a specific line of work associated with an individual or program of research, then the individual or representative of the research program whose work is critiqued should be notified in advance about the upcoming publication and given the opportunity to reply, ideally in the same issue. The author of the original article should also be notified. Normal guidelines for length and review of the reply and publication of a rejoinder by the original article’s author(s) should be followed. Articles in the format “an open letter to …” may constitute prototypical exemplars of the category defined here, but other formats may well be used, and would be included under the qualifications for response prescribed here (Council, January 2002).

Authors who believe that their manuscripts were not reviewed in a careful or timely manner and in accordance with AERA procedures should call the matter to the attention of the Association’s executive officer or president.

Sage Choice and Open Access

If you or your funder wish your article to be freely available online to nonsubscribers immediately upon publication (gold open access), you can opt for it to be included in Sage Choice, subject to payment of a publication fee. The manuscript submission and peer review procedure is unchanged. On acceptance of your article, you will be asked to let Sage know directly if you are choosing Sage Choice. To check journal eligibility and the publication fee, please visit Sage Choice . For more information on open access options and compliance at Sage, including self author archiving deposits (green open access) visit Sage Publishing Policies on our Journal Author Gateway.

2016-2018 Coeditors - stop receiving new manuscripts June 30, 2018

2019-2021 Coeditors - begin receiving new manuscripts July 1, 2018

- Read Online

- Sample Issues

- Current Issue

- Email Alert

- Permissions

- Foreign rights

- Reprints and sponsorship

- Advertising

Individual Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription, E-access

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, E-access Plus Backfile (All Online Content)

Institutional Subscription, Print Only

Institutional Subscription, Combined (Print & E-access)

Institutional Subscription & Backfile Lease, Combined Plus Backfile (Current Volume Print & All Online Content)

Institutional Backfile Purchase, E-access (Content through 1998)

Individual, Single Print Issue

Institutional, Single Print Issue

To order single issues of this journal, please contact SAGE Customer Services at 1-800-818-7243 / 1-805-583-9774 with details of the volume and issue you would like to purchase.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 30 January 2023

A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- Bastian A. Betthäuser ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4544-4073 1 , 2 , 3 ,

- Anders M. Bach-Mortensen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7804-7958 2 &

- Per Engzell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2404-6308 3 , 4 , 5

Nature Human Behaviour volume 7 , pages 375–385 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

72k Accesses

119 Citations

1974 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social policy

To what extent has the learning progress of school-aged children slowed down during the COVID-19 pandemic? A growing number of studies address this question, but findings vary depending on context. Here we conduct a pre-registered systematic review, quality appraisal and meta-analysis of 42 studies across 15 countries to assess the magnitude of learning deficits during the pandemic. We find a substantial overall learning deficit (Cohen’s d = −0.14, 95% confidence interval −0.17 to −0.10), which arose early in the pandemic and persists over time. Learning deficits are particularly large among children from low socio-economic backgrounds. They are also larger in maths than in reading and in middle-income countries relative to high-income countries. There is a lack of evidence on learning progress during the pandemic in low-income countries. Future research should address this evidence gap and avoid the common risks of bias that we identify.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elementary school teachers’ perspectives about learning during the COVID-19 pandemic

A methodological perspective on learning in the developing brain

Measuring and forecasting progress in education: what about early childhood?

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to one of the largest disruptions to learning in history. To a large extent, this is due to school closures, which are estimated to have affected 95% of the world’s student population 1 . But even when face-to-face teaching resumed, instruction has often been compromised by hybrid teaching, and by children or teachers having to quarantine and miss classes. The effect of limited face-to-face instruction is compounded by the pandemic’s consequences for children’s out-of-school learning environment, as well as their mental and physical health. Lockdowns have restricted children’s movement and their ability to play, meet other children and engage in extra-curricular activities. Children’s wellbeing and family relationships have also suffered due to economic uncertainties and conflicting demands of work, care and learning. These negative consequences can be expected to be most pronounced for children from low socio-economic family backgrounds, exacerbating pre-existing educational inequalities.

It is critical to understand the extent to which learning progress has changed since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. We use the term ‘learning deficit’ to encompass both a delay in expected learning progress, as well as a loss of skills and knowledge already gained. The COVID-19 learning deficit is likely to affect children’s life chances through their education and labour market prospects. At the societal level, it can have important implications for growth, prosperity and social cohesion. As policy-makers across the world are seeking to limit further learning deficits and to devise policies to recover learning deficits that have already been incurred, assessing the current state of learning is crucial. A careful assessment of the COVID-19 learning deficit is also necessary to weigh the true costs and benefits of school closures.

A number of narrative reviews have sought to summarize the emerging research on COVID-19 and learning, mostly focusing on learning progress relatively early in the pandemic 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 . Moreover, two reviews harmonized and synthesized existing estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic 7 , 8 . In line with the narrative reviews, these two reviews find a substantial reduction in learning progress during the pandemic. However, this finding is based on a relatively small number of studies (18 and 10 studies, respectively). The limited evidence that was available at the time these reviews were conducted also precluded them from meta-analysing variation in the magnitude of learning deficits over time and across subjects, different groups of students or country contexts.

In this Article, we conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits 2.5 years into the pandemic. Our primary pre-registered research question was ‘What is the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning progress amongst school-age children?’, and we address this question using evidence from studies examining changes in learning outcomes during the pandemic. Our second pre-registered research aim was ‘To examine whether the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on learning differs across different social background groups, age groups, boys and girls, learning areas or subjects, national contexts’.

We contribute to the existing research in two ways. First, we describe and appraise the up-to-date body of evidence, including its geographic reach and quality. More specifically, we ask the following questions: (1) what is the state of the evidence, in terms of the available peer-reviewed research and grey literature, on learning progress of school-aged children during the COVID-19 pandemic?, (2) which countries are represented in the available evidence? and (3) what is the quality of the existing evidence?

Our second contribution is to harmonize, synthesize and meta-analyse the existing evidence, with special attention to variation across different subpopulations and country contexts. On the basis of the identified studies, we ask (4) to what extent has the learning progress of school-aged children changed since the onset of the pandemic?, (5) how has the magnitude of the learning deficit (if any) evolved since the beginning of the pandemic?, (6) to what extent has the pandemic reinforced inequalities between children from different socio-economic backgrounds?, (7) are there differences in the magnitude of learning deficits between subject domains (maths and reading) and between age groups (primary and secondary students)? and (8) to what extent does the magnitude of learning deficits vary across national contexts?

Below, we report our answers to each of these questions in turn. The questions correspond to the analysis plan set out in our pre-registered protocol ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021249944 ), but we have adjusted the order and wording to aid readability. We had planned to examine gender differences in learning progress during the pandemic, but found there to be insufficient evidence to conduct this subgroup analysis, as the large majority of the identified studies do not provide evidence on learning deficits separately by gender. We also planned to examine how the magnitude of learning deficits differs across groups of students with varying exposures to school closures. This was not possible as the available data on school closures lack sufficient depth with respect to variation of school closures within countries, across grade levels and with respect to different modes of instruction, to meaningfully examine this association.

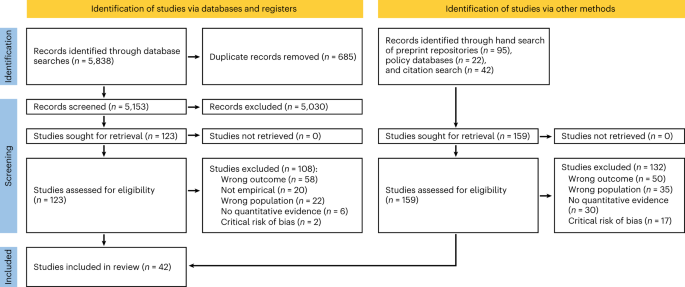

The state of the evidence

Our systematic review identified 42 studies on learning progress during the COVID-19 pandemic that met our inclusion criteria. To be included in our systematic review and meta-analysis, studies had to use a measure of learning that can be standardized (using Cohen’s d ) and base their estimates on empirical data collected since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic (rather than making projections based on pre-COVID-19 data). As shown in Fig. 1 , the initial literature search resulted in 5,153 hits after removal of duplicates. All studies were double screened by the first two authors. The formal database search process identified 15 eligible studies. We also hand searched relevant preprint repositories and policy databases. Further, to ensure that our study selection was as up to date as possible, we conducted two full forward and backward citation searches of all included studies on 15 February 2022, and on 8 August 2022. The citation and preprint hand searches allowed us to identify 27 additional eligible studies, resulting in a total of 42 studies. Most of these studies were published after the initial database search, which illustrates that the body of evidence continues to expand. Most studies provide multiple estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits, separately for maths and reading and for different school grades. The number of estimates ( n = 291) is therefore larger than the number of included studies ( n = 42).

Flow diagram of the study identification and selection process, following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

The geographic reach of evidence is limited

Table 1 presents all included studies and estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits (in brackets), grouped by the 15 countries represented: Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Colombia, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Mexico, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and the United States. About half of the estimates ( n = 149) are from the United States, 58 are from the UK, a further 70 are from other European countries and the remaining 14 estimates are from Australia, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. As this list shows, there is a strong over-representation of studies from high-income countries, a dearth of studies from middle-income countries and no studies from low-income countries. This skewed representation should be kept in mind when interpreting our synthesis of the existing evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits.

The quality of evidence is mixed

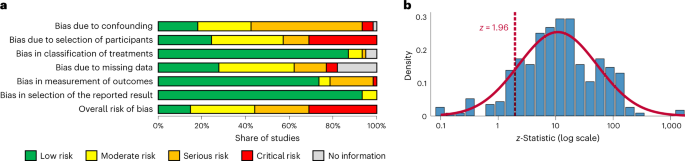

We assessed the quality of the evidence using an adapted version of the Risk Of Bias In Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I) tool 9 . More specifically, we analysed the risk of bias of each estimate from confounding, sample selection, classification of treatments, missing data, the measurement of outcomes and the selection of reported results. A.M.B.-M. and B.A.B. performed the risk-of-bias assessments, which were independently checked by the respective other author. We then assigned each study an overall risk-of-bias rating (low, moderate, serious or critical) based on the estimate and domain with the highest risk of bias.

Figure 2a shows the distribution of all studies of COVID-19 learning deficits according to their risk-of-bias rating separately for each domain (top six rows), as well as the distribution of studies according to their overall risk of bias rating (bottom row). The overall risk of bias was considered ‘low’ for 15% of studies, ‘moderate’ for 30% of studies, ‘serious’ for 25% of studies and ‘critical’ for 30% of studies.

a , Domain-specific and overall distribution of studies of COVID-19 learning deficits by risk of bias rating using ROBINS-I, including studies rated to be at critical risk of bias ( n = 19 out of a total of n = 61 studies shown in this figure). In line with ROBINS-I guidance, studies rated to be at critical risk of bias were excluded from all analyses and other figures in this article and in the Supplementary Information (including b ). b , z curve: distribution of the z scores of all estimates included in the meta-analysis ( n = 291) to test for publication bias. The dotted line indicates z = 1.96 ( P = 0.050), the conventional threshold for statistical significance. The overlaid curve shows a normal distribution. The absence of a spike in the distribution of the z scores just above the threshold for statistical significance and the absence of a slump just below it indicate the absence of evidence for publication bias.

In line with ROBINS-I guidance, we excluded studies rated to be at critical risk of bias ( n = 19) from all of our analyses and figures, except for Fig. 2a , which visualizes the distribution of studies according to their risk of bias 9 . These are thus not part of the 42 studies included in our meta-analysis. Supplementary Table 2 provides an overview of these studies as well as the main potential sources of risk of bias. Moreover, in Supplementary Figs. 3 – 6 , we replicate all our results excluding studies deemed to be at serious risk of bias.

As shown in Fig. 2a , common sources of potential bias were confounding, sample selection and missing data. Studies rated at risk of confounding typically compared only two timepoints, without accounting for longer time trends in learning progress. The main causes of selection bias were the use of convenience samples and insufficient consideration of self-selection by schools or students. Several studies found evidence of selection bias, often with students from a low socio-economic background or schools in deprived areas being under-represented after (as compared with before) the pandemic, but this was not always adjusted for. Some studies also reported a higher amount of missing data post-pandemic, again generally without adjustment, and several studies did not report any information on missing data. For an overview of the risk-of-bias ratings for each domain of each study, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Tables 1 and 2 .

No evidence of publication bias

Publication bias can occur if authors self-censor to conform to theoretical expectations, or if journals favour statistically significant results. To mitigate this concern, we include not only published papers, but also preprints, working papers and policy reports.

Moreover, Fig. 2b tests for publication bias by showing the distribution of z -statistics for the effect size estimates of all identified studies. The dotted line indicates z = 1.96 ( P = 0.050), the conventional threshold for statistical significance. The overlaid curve shows a normal distribution. If there was publication bias, we would expect a spike just above the threshold, and a slump just below it. There is no indication of this. Moreover, we do not find a left-skewed distribution of P values (see P curve in Supplementary Fig. 2a ), or an association between estimates of learning deficits and their standard errors (see funnel plot in Supplementary Fig. 2b ) that would suggest publication bias. Publication bias thus does not appear to be a major concern.

Having assessed the quality of the existing evidence, we now present the substantive results of our meta-analysis, focusing on the magnitude of COVID-19 learning deficits and on the variation in learning deficits over time, across different groups of students, and across country contexts.

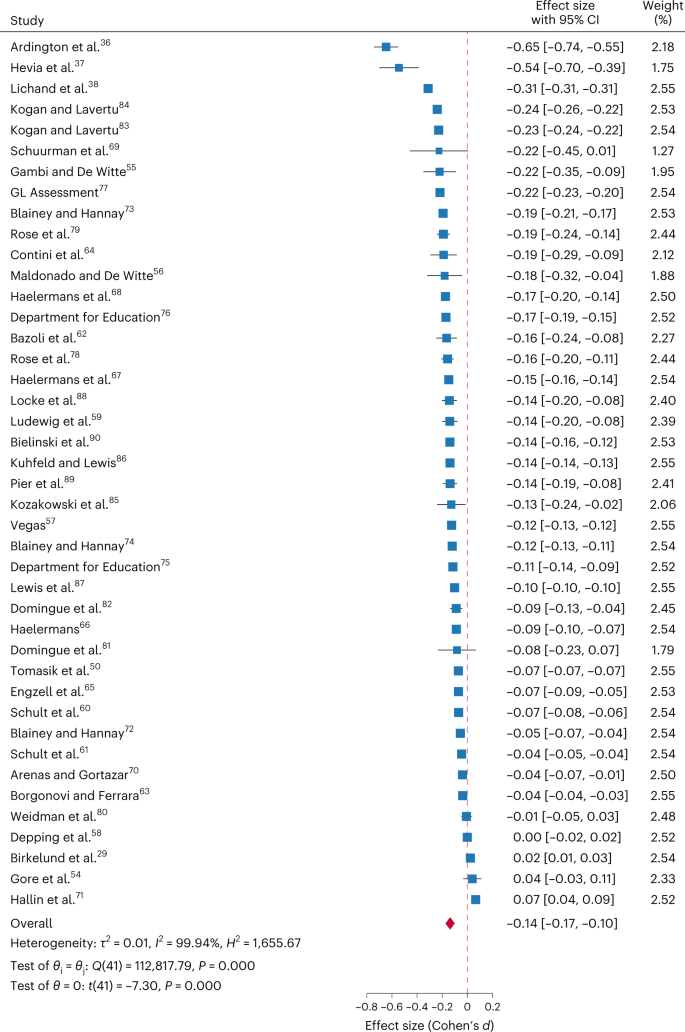

Learning progress slowed substantially during the pandemic

Figure 3 shows the effect sizes that we extracted from each study (averaged across grades and learning subject) as well as the pooled effect size (red diamond). Effects are expressed in standard deviations, using Cohen’s d . Estimates are pooled using inverse variance weights. The pooled effect size across all studies is d = −0.14, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.000, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.17 to −0.10. Under normal circumstances, students generally improve their performance by around 0.4 standard deviations per school year 10 , 11 , 12 . Thus, the overall effect of d = −0.14 suggests that students lost out on 0.14/0.4, or about 35%, of a school year’s worth of learning. On average, the learning progress of school-aged children has slowed substantially during the pandemic.

Effect sizes are expressed in standard deviations, using Cohen’s d , with 95% CI, and are sorted by magnitude.

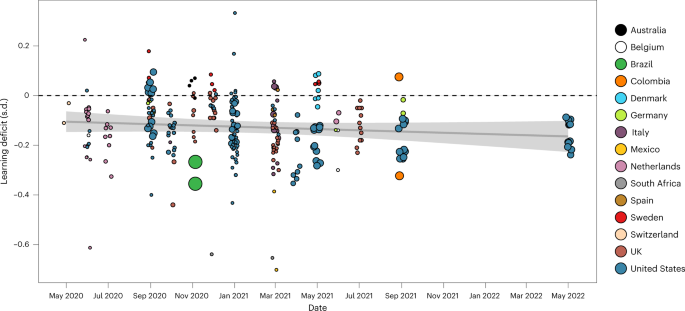

Learning deficits arose early in the pandemic and persist

One may expect that children were able to recover learning that was lost early in the pandemic, after teachers and families had time to adjust to the new learning conditions and after structures for online learning and for recovering early learning deficits were set up. However, existing research on teacher strikes in Belgium 13 and Argentina 14 , shortened school years in Germany 15 and disruptions to education during World War II 16 suggests that learning deficits are difficult to compensate and tend to persist in the long run.

Figure 4 plots the magnitude of estimated learning deficits (on the vertical axis) by the date of measurement (on the horizontal axis). The colour of the circles reflects the relevant country, the size of the circles indicates the sample size for a given estimate and the line displays a linear trend. The figure suggests that learning deficits opened up early in the pandemic and have neither closed nor substantially widened since then. We find no evidence that the slope coefficient is different from zero ( β months = −0.00, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.097, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.00). This implies that efforts by children, parents, teachers and policy-makers to adjust to the changed circumstance have been successful in preventing further learning deficits but so far have been unable to reverse them. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8 , the pattern of persistent learning deficits also emerges within each of the three countries for which we have a relatively large number of estimates at different timepoints: the United States, the UK and the Netherlands. However, it is important to note that estimates of learning deficits are based on distinct samples of students. Future research should continue to follow the learning progress of cohorts of students in different countries to reveal how learning deficits of these cohorts have developed and continue to develop since the onset of the pandemic.

The horizontal axis displays the date on which learning progress was measured. The vertical axis displays estimated learning deficits, expressed in standard deviation (s.d.) using Cohen’s d . The colour of the circles reflects the respective country, the size of the circles indicates the sample size for a given estimate and the line displays a linear trend with a 95% CI. The trend line is estimated as a linear regression using ordinary least squares, with standard errors clustered at the study level ( n = 42 clusters). β months = −0.00, t (41) = −7.30, two-tailed P = 0.097, 95% CI −0.01 to 0.00.

Socio-economic inequality in education increased

Existing research on the development of learning gaps during summer vacations 17 , 18 , disruptions to schooling during the Ebola outbreak in Sierra Leone and Guinea 19 , and the 2005 earthquake in Pakistan 20 shows that the suspension of face-to-face teaching can increase educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds. Learning deficits during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to have been particularly pronounced for children from low socio-economic backgrounds. These children have been more affected by school closures than children from more advantaged backgrounds 21 . Moreover, they are likely to be disadvantaged with respect to their access and ability to use digital learning technology, the quality of their home learning environment, the learning support they receive from teachers and parents, and their ability to study autonomously 22 , 23 , 24 .

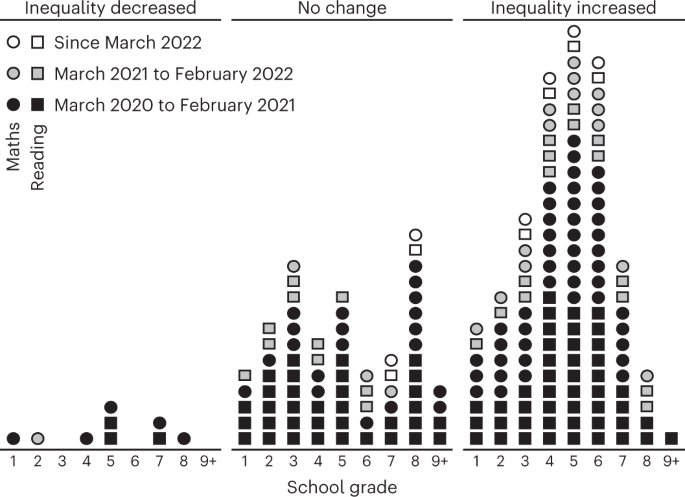

Most studies we identify examine changes in socio-economic inequality during the pandemic, attesting to the importance of the issue. As studies use different measures of socio-economic background (for example, parental income, parental education, free school meal eligibility or neighbourhood disadvantage), pooling the estimates is not possible. Instead, we code all estimates according to whether they indicate a reduction, no change or an increase in learning inequality during the pandemic. Figure 5 displays this information. Estimates that indicate an increase in inequality are shown on the right, those that indicate a decrease on the left and those that suggest no change in the middle. Squares represent estimates of changes in inequality during the pandemic in reading performance, and circles represent estimates of changes in inequality in maths performance. The shading represents when in the pandemic educational inequality was measured, differentiating between the first, second and third year of the pandemic. Estimates are also arranged horizontally by grade level. A large majority of estimates indicate an increase in educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds. This holds for both maths and reading, across primary and secondary education, at each stage of the pandemic, and independently of how socio-economic background is measured.

Each circle/square refers to one estimate of over-time change in inequality in maths/reading performance ( n = 211). Estimates that find a decrease/no change/increase in inequality are grouped on the left/middle/right. Within these categories, estimates are ordered horizontally by school grade. The shading indicates when in the pandemic a given measure was taken.

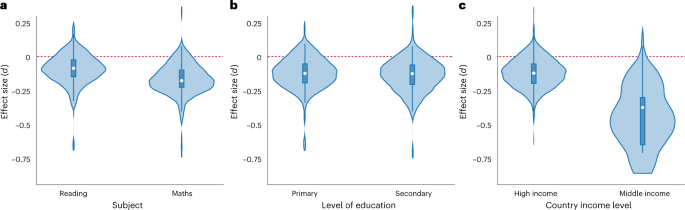

Learning deficits are larger in maths than in reading

Available research on summer learning deficits 17 , 25 , student absenteeism 26 , 27 and extreme weather events 28 suggests that learning progress in mathematics is more dependent on formal instruction than in reading. This might be due to parents being better equipped to help their children with reading, and children advancing their reading skills (but not their maths skills) when reading for enjoyment outside of school. Figure 6a shows that, similarly to earlier disruptions to learning, the estimated learning deficits during the COVID-19 pandemic are larger for maths than for reading (mean difference δ = −0.07, t (41) = −4.02, two-tailed P = 0.000, 95% CI −0.11 to −0.04). This difference is statistically significant and robust to dropping estimates from individual countries (Supplementary Fig. 9 ).

Each plot shows the distribution of COVID-19 learning deficit estimates for the respective subgroup, with the box marking the interquartile range and the white circle denoting the median. Whiskers mark upper and lower adjacent values: the furthest observation within 1.5 interquartile range of either side of the box. a , Learning subject (reading versus maths). Median: reading −0.09, maths −0.18. Interquartile range: reading −0.15 to −0.02, maths −0.23 to −0.09. b , Level of education (primary versus secondary). Median: primary −0.12, secondary −0.12. Interquartile range: primary −0.19 to −0.05, secondary −0.21 to −0.06. c , Country income level (high versus middle). Median: high −0.12, middle −0.37. Interquartile range: high −0.20 to −0.05, middle −0.65 to −0.30.

No evidence of variation across grade levels

One may expect learning deficits to be smaller for older than for younger children, as older children may be more autonomous in their learning and better able to cope with a sudden change in their learning environment. However, older students were subject to longer school closures in some countries, such as Denmark 29 , based partly on the assumption that they would be better able to learn from home. This may have offset any advantage that older children would otherwise have had in learning remotely.

Figure 6b shows the distribution of estimates of learning deficits for students at the primary and secondary level, respectively. Our analysis yields no evidence of variation in learning deficits across grade levels (mean difference δ = −0.01, t (41) = −0.59, two-tailed P = 0.556, 95% CI −0.06 to 0.03). Due to the limited number of available estimates of learning deficits, we cannot be certain about whether learning deficits differ between primary and secondary students or not.

Learning deficits are larger in poorer countries

Low- and middle-income countries were already struggling with a learning crisis before the pandemic. Despite large expansions of the proportion of children in school, children in low- and middle-income countries still perform poorly by international standards, and inequality in learning remains high 30 , 31 , 32 . The pandemic is likely to deepen this learning crisis and to undo past progress. Schools in low- and middle-income countries have not only been closed for longer, but have also had fewer resources to facilitate remote learning 33 , 34 . Moreover, the economic resources, availability of digital learning equipment and ability of children, parents, teachers and governments to support learning from home are likely to be lower in low- and middle-income countries 35 .

As discussed above, most evidence on COVID-19 learning deficits comes from high-income countries. We found no studies on low-income countries that met our inclusion criteria, and evidence from middle-income countries is limited to Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. Figure 6c groups the estimates of COVID-19 learning deficits in these four middle-income countries together (on the right) and compares them with estimates from high-income countries (on the left). The learning deficit is appreciably larger in middle-income countries than in high-income countries (mean difference δ = −0.29, t (41) = −2.78, two-tailed P = 0.008, 95% CI −0.50 to −0.08). In fact, the three largest estimates of learning deficits in our sample are from middle-income countries (Fig. 3 ) 36 , 37 , 38 .

Two years since the COVID-19 pandemic, there is a growing number of studies examining the learning progress of school-aged children during the pandemic. This paper first systematically reviews the existing literature on learning progress of school-aged children during the pandemic and appraises its geographic reach and quality. Second, it harmonizes, synthesizes and meta-analyses the existing evidence to examine the extent to which learning progress has changed since the onset of the pandemic, and how it varies across different groups of students and across country contexts.

Our meta-analysis suggests that learning progress has slowed substantially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The pooled effect size of d = −0.14, implies that students lost out on about 35% of a normal school year’s worth of learning. This confirms initial concerns that substantial learning deficits would arise during the pandemic 10 , 39 , 40 . But our results also suggest that fears of an accumulation of learning deficits as the pandemic continues have not materialized 41 , 42 . On average, learning deficits emerged early in the pandemic and have neither closed nor widened substantially. Future research should continue to follow the learning progress of cohorts of students in different countries to reveal how learning deficits of these cohorts have developed and continue to develop since the onset of the pandemic.

Most studies that we identify find that learning deficits have been largest for children from disadvantaged socio-economic backgrounds. This holds across different timepoints during the pandemic, countries, grade levels and learning subjects, and independently of how socio-economic background is measured. It suggests that the pandemic has exacerbated educational inequalities between children from different socio-economic backgrounds, which were already large before the pandemic 43 , 44 . Policy initiatives to compensate learning deficits need to prioritize support for children from low socio-economic backgrounds in order to allow them to recover the learning they lost during the pandemic.

There is a need for future research to assess how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected gender inequality in education. So far, there is very little evidence on this issue. The large majority of the studies that we identify do not examine learning deficits separately by gender.

Comparing estimates of learning deficits across subjects, we find that learning deficits tend to be larger in maths than in reading. As noted above, this may be due to the fact that parents and children have been in a better position to compensate school-based learning in reading by reading at home. Accordingly, there are grounds for policy initiatives to prioritize the compensation of learning deficits in maths and other science subjects.

A limitation of this study and the existing body of evidence on learning progress during the COVID-19 pandemic is that the existing studies primarily focus on high-income countries, while there is a dearth of evidence from low- and middle-income countries. This is particularly concerning because the small number of existing studies from middle-income countries suggest that learning deficits have been particularly severe in these countries. Learning deficits are likely to be even larger in low-income countries, considering that these countries already faced a learning crisis before the pandemic, generally implemented longer school closures, and were under-resourced and ill-equipped to facilitate remote learning 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 45 . It is critical that this evidence gap on low- and middle-income countries is addressed swiftly, and that the infrastructure to collect and share data on educational performance in middle- and low-income countries is strengthened. Collecting and making available these data is a key prerequisite for fully understanding how learning progress and related outcomes have changed since the onset of the pandemic 46 .

A further limitation is that about half of the studies that we identify are rated as having a serious or critical risk of bias. We seek to limit the risk of bias in our results by excluding all studies rated to be at critical risk of bias from all of our analyses. Moreover, in Supplementary Figs. 3 – 6 , we show that our results are robust to further excluding studies deemed to be at serious risk of bias. Future studies should minimize risk of bias in estimating learning deficits by employing research designs that appropriately account for common sources of bias. These include a lack of accounting for secular time trends, non-representative samples and imbalances between treatment and comparison groups.

The persistence of learning deficits two and a half years into the pandemic highlights the need for well-designed, well-resourced and decisive policy initiatives to recover learning deficits. Policy-makers, schools and families will need to identify and realize opportunities to complement and expand on regular school-based learning. Experimental evidence from low- and middle-income countries suggests that even relatively low-tech and low-cost learning interventions can have substantial, positive effects on students’ learning progress in the context of remote learning. For example, sending SMS messages with numeracy problems accompanied by short phone calls was found to lead to substantial learning gains in numeracy in Botswana 47 . Sending motivational text messages successfully limited learning losses in maths and Portuguese in Brazil 48 .

More evidence is needed to assess the effectiveness of other interventions for limiting or recovering learning deficits. Potential avenues include the use of the often extensive summer holidays to offer summer schools and learning camps, extending school days and school weeks, and organizing and scaling up tutoring programmes. Further potential lies in developing, advertising and providing access to learning apps, online learning platforms or educational TV programmes that are free at the point of use. Many countries have already begun investing substantial resources to capitalize on some of these opportunities. If these interventions prove effective, and if the momentum of existing policy efforts is maintained and expanded, the disruptions to learning during the pandemic may be a window of opportunity to improve the education afforded to children.

Eligibility criteria

We consider all types of primary research, including peer-reviewed publications, preprints, working papers and reports, for inclusion. To be eligible for inclusion, studies have to measure learning progress using test scores that can be standardized across studies using Cohen’s d . Moreover, studies have to be in English, Danish, Dutch, French, German, Norwegian, Spanish or Swedish.

Search strategy and study identification

We identified relevant studies using the following steps. First, we developed a Boolean search string defining the population (school-aged children), exposure (the COVID-19 pandemic) and outcomes of interest (learning progress). The full search string can be found in Section 1.1 of Supplementary Information . Second, we used this string to search the following academic databases: Coronavirus Research Database, the Education Resources Information Centre, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Politics Collection (PAIS index, policy file index, political science database and worldwide political science abstracts), Social Science Database, Sociology Collection (applied social science index and abstracts, sociological abstracts and sociology database), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Web of Science. Second, we hand-searched multiple preprint and working paper repositories (Social Science Research Network, Munich Personal RePEc Archive, IZA, National Bureau of Economic Research, OSF Preprints, PsyArXiv, SocArXiv and EdArXiv) and relevant policy websites, including the websites of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, the United Nations, the World Bank and the Education Endowment Foundation. Third, we periodically posted our protocol via Twitter in order to crowdsource additional relevant studies not identified through the search. All titles and abstracts identified in our search were double-screened using the Rayyan online application 49 . Our initial search was conducted on 27 April 2021, and we conducted two forward and backward citation searches of all eligible studies identified in the above steps, on 14 February 2022, and on 8 August 2022, to ensure that our analysis includes recent relevant research.

Data extraction

From the studies that meet our inclusion criteria we extracted all estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic, separately for maths and reading and for different school grades. We also extracted the corresponding sample size, standard error, date(s) of measurement, author name(s) and country. Last, we recorded whether studies differentiate between children’s socio-economic background, which measure is used to this end and whether studies find an increase, decrease or no change in learning inequality. We contacted study authors if any of the above information was missing in the study. Data extraction was performed by B.A.B. and validated independently by A.M.B.-M., with discrepancies resolved through discussion and by conferring with P.E.

Measurement and standardizationr

We standardize all estimates of learning deficits during the pandemic using Cohen’s d , which expresses effect sizes in terms of standard deviations. Cohen’s d is calculated as the difference in the mean learning gain in a given subject (maths or reading) over two comparable periods before and after the onset of the pandemic, divided by the pooled standard deviation of learning progress in this subject:

Effect sizes expressed as β coefficients are converted to Cohen’s d :

We use a binary indicator for whether the study outcome is maths or reading. One study does not differentiate the outcome but includes a composite of maths and reading scores 50 .

Level of education

We distinguish between primary and secondary education. We first consulted the original studies for this information. Where this was not stated in a given study, students’ age was used in conjunction with information about education systems from external sources to determine the level of education 51 .

Country income level

We follow the World Bank’s classification of countries into four income groups: low, lower-middle, upper-middle and high income. Four countries in our sample are in the upper-middle-income group: Brazil, Colombia, Mexico and South Africa. All other countries are in the high-income group.

Data synthesis

We synthesize our data using three synthesis techniques. First, we generate a forest plot, based on all available estimates of learning progress during the pandemic. We pool estimates using a random-effects restricted maximum likelihood model and inverse variance weights to calculate an overall effect size (Fig. 3 ) 52 . Second, we code all estimates of changes in educational inequality between children from different socio-economic backgrounds during the pandemic, according to whether they indicate an increase, a decrease or no change in educational inequality. We visualize the resulting distribution using a harvest plot (Fig. 5 ) 53 . Third, given that the limited amount of available evidence precludes multivariate or causal analyses, we examine the bivariate association between COVID-19 learning deficits and the months in which learning was measured using a scatter plot (Fig. 4 ), and the bivariate association between COVID-19 learning deficits and subject, grade level and countries’ income level, using a series of violin plots (Fig. 6 ). The reported estimates, CIs and statistical significance tests of these bivariate associations are based on common-effects models with standard errors clustered by study, and two-sided tests. With respect to statistical tests reported, the data distribution was assumed to be normal, but this was not formally tested. The distribution of estimates of learning deficits is shown separately for the different moderator categories in Fig. 6 .

Pre-registration

We prospectively registered a protocol of our systematic review and meta-analysis in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42021249944) on 19 April 2021 ( https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42021249944 ).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data used in the analyses for this manuscript were compiled by the authors based on the studies identified in the systematic review. The data are available on the Open Science Framework repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/u8gaz ). For our systematic review, we searched the following databases: Coronavirus Research Database ( https://proquest.libguides.com/covid19 ), Education Resources Information Centre database ( https://eric.ed.gov ), International Bibliography of the Social Sciences ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ibss-set-c/ ), Politics Collection ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ProQuest-Politics-Collection/ ), Social Science Database ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/pq_social_science/ ), Sociology Collection ( https://about.proquest.com/en/products-services/ProQuest-Sociology-Collection/ ), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature ( https://www.ebsco.com/products/research-databases/cinahl-database ) and Web of Science ( https://clarivate.com/webofsciencegroup/solutions/web-of-science/ ). We also searched the following preprint and working paper repositories: Social Science Research Network ( https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/DisplayJournalBrowse.cfm ), Munich Personal RePEc Archive ( https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de ), IZA ( https://www.iza.org/content/publications ), National Bureau of Economic Research ( https://www.nber.org/papers?page=1&perPage=50&sortBy=public_date ), OSF Preprints ( https://osf.io/preprints/ ), PsyArXiv ( https://psyarxiv.com ), SocArXiv ( https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv ) and EdArXiv ( https://edarxiv.org ).

Code availability

All code needed to replicate our findings is available on the Open Science Framework repository ( https://doi.org/10.17605/osf.io/u8gaz ).

The Impact of COVID-19 on Children. UN Policy Briefs (United Nations, 2020).

Donnelly, R. & Patrinos, H. A. Learning loss during Covid-19: An early systematic review. Prospects (Paris) 51 , 601–609 (2022).

Hammerstein, S., König, C., Dreisörner, T. & Frey, A. Effects of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a systematic review. Front. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.746289 (2021).

Panagouli, E. et al. School performance among children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Children 8 , 1134 (2021).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Patrinos, H. A., Vegas, E. & Carter-Rau, R. An Analysis of COVID-19 Student Learning Loss (World Bank, 2022).

Zierer, K. Effects of pandemic-related school closures on pupils’ performance and learning in selected countries: a rapid review. Educ. Sci. 11 , 252 (2021).

Article Google Scholar

König, C. & Frey, A. The impact of COVID-19-related school closures on student achievement: a meta-analysis. Educ. Meas. Issues Pract. 41 , 16–22 (2022).

Storey, N. & Zhang, Q. A meta-analysis of COVID learning loss. Preprint at EdArXiv (2021).

Sterne, J. A. et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4919 (2016).

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Iqbal, S. A. & Geven, K. Simulating the Potential Impacts of COVID-19 School Closures on Schooling and Learning Outcomes: A Set of Global Estimates (World Bank, 2020).

Bloom, H. S., Hill, C. J., Black, A. R. & Lipsey, M. W. Performance trajectories and performance gaps as achievement effect-size benchmarks for educational interventions. J. Res. Educ. Effectiveness 1 , 289–328 (2008).

Hill, C. J., Bloom, H. S., Black, A. R. & Lipsey, M. W. Empirical benchmarks for interpreting effect sizes in research. Child Dev. Perspect. 2 , 172–177 (2008).

Belot, M. & Webbink, D. Do teacher strikes harm educational attainment of students? Labour 24 , 391–406 (2010).

Jaume, D. & Willén, A. The long-run effects of teacher strikes: evidence from Argentina. J. Labor Econ. 37 , 1097–1139 (2019).

Cygan-Rehm, K. Are there no wage returns to compulsory schooling in Germany? A reassessment. J. Appl. Econ. 37 , 218–223 (2022).

Ichino, A. & Winter-Ebmer, R. The long-run educational cost of World War II. J. Labor Econ. 22 , 57–87 (2004).

Cooper, H., Nye, B., Charlton, K., Lindsay, J. & Greathouse, S. The effects of summer vacation on achievement test scores: a narrative and meta-analytic review. Rev. Educ. Res. 66 , 227–268 (1996).

Allington, R. L. et al. Addressing summer reading setback among economically disadvantaged elementary students. Read. Psychol. 31 , 411–427 (2010).

Smith, W. C. Consequences of school closure on access to education: lessons from the 2013–2016 Ebola pandemic. Int. Rev. Educ. 67 , 53–78 (2021).

Andrabi, T., Daniels, B. & Das, J. Human capital accumulation and disasters: evidence from the Pakistan earthquake of 2005. J. Hum. Resour . https://doi.org/10.35489/BSG-RISE-WP_2020/039 (2021).

Parolin, Z. & Lee, E. K. Large socio-economic, geographic and demographic disparities exist in exposure to school closures. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 522–528 (2021).

Goudeau, S., Sanrey, C., Stanczak, A., Manstead, A. & Darnon, C. Why lockdown and distance learning during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely to increase the social class achievement gap. Nat. Hum. Behav. 5 , 1273–1281 (2021).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bailey, D. H., Duncan, G. J., Murnane, R. J. & Au Yeung, N. Achievement gaps in the wake of COVID-19. Educ. Researcher 50 , 266–275 (2021).

van de Werfhorst, H. G. Inequality in learning is a major concern after school closures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2105243118 (2021).

Alexander, K. L., Entwisle, D. R. & Olson, L. S. Schools, achievement, and inequality: a seasonal perspective. Educ. Eval. Policy Anal. 23 , 171–191 (2001).

Aucejo, E. M. & Romano, T. F. Assessing the effect of school days and absences on test score performance. Econ. Educ. Rev. 55 , 70–87 (2016).

Gottfried, M. A. The detrimental effects of missing school: evidence from urban siblings. Am. J. Educ. 117 , 147–182 (2011).

Goodman, J. Flaking Out: Student Absences and Snow Days as Disruptions of Instructional Time (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2014).

Birkelund, J. F. & Karlson, K. B. No evidence of a major learning slide 14 months into the COVID-19 pandemic in Denmark. European Societies https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2022.2129085 (2022).

Angrist, N., Djankov, S., Goldberg, P. K. & Patrinos, H. A. Measuring human capital using global learning data. Nature 592 , 403–408 (2021).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Torche, F. in Social Mobility in Developing Countries: Concepts, Methods, and Determinants (eds Iversen, V., Krishna, A. & Sen, K.) 139–171 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2021).

World Development Report 2018: Learning to Realize Education’s Promise (World Bank, 2018).

Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and Beyond (United Nations, 2020).

One Year into COVID-19 Education Disruption: Where Do We Stand? (UNESCO, 2021).

Azevedo, J. P., Hasan, A., Goldemberg, D., Geven, K. & Iqbal, S. A. Simulating the potential impacts of COVID-19 school closures on schooling and learning outcomes: a set of global estimates. World Bank Res. Observer 36 , 1–40 (2021).

Google Scholar

Ardington, C., Wills, G. & Kotze, J. COVID-19 learning losses: early grade reading in South Africa. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 86 , 102480 (2021).

Hevia, F. J., Vergara-Lope, S., Velásquez-Durán, A. & Calderón, D. Estimation of the fundamental learning loss and learning poverty related to COVID-19 pandemic in Mexico. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 88 , 102515 (2022).

Lichand, G., Doria, C. A., Leal-Neto, O. & Fernandes, J. P. C. The impacts of remote learning in secondary education during the pandemic in Brazil. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6 , 1079–1086 (2022).

Major, L. E., Eyles, A., Machin, S. et al. Learning Loss since Lockdown: Variation across the Home Nations (Centre for Economic Performance, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2021).

Di Pietro, G., Biagi, F., Costa, P., Karpinski, Z. & Mazza, J. The Likely Impact of COVID-19 on Education: Reflections Based on the Existing Literature and Recent International Datasets (Publications Office of the European Union, 2020).

Fuchs-Schündeln, N., Krueger, D., Ludwig, A. & Popova, I. The Long-Term Distributional and Welfare Effects of COVID-19 School Closures (National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020).

Kaffenberger, M. Modelling the long-run learning impact of the COVID-19 learning shock: actions to (more than) mitigate loss. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 81 , 102326 (2021).

Attewell, P. & Newman, K. S. Growing Gaps: Educational Inequality around the World (Oxford Univ. Press, 2010).

Betthäuser, B. A., Kaiser, C. & Trinh, N. A. Regional variation in inequality of educational opportunity across europe. Socius https://doi.org/10.1177/23780231211019890 (2021).

Angrist, N. et al. Building back better to avert a learning catastrophe: estimating learning loss from covid-19 school shutdowns in africa and facilitating short-term and long-term learning recovery. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 84 , 102397 (2021).

Conley, D. & Johnson, T. Opinion: Past is future for the era of COVID-19 research in the social sciences. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2104155118 (2021).

Angrist, N., Bergman, P. & Matsheng, M. Experimental evidence on learning using low-tech when school is out. Nat. Hum. Behav. 6 , 941–950 (2022).

Lichand, G., Christen, J. & van Egeraat, E. Do Behavioral Nudges Work under Remote Learning? Evidence from Brazil during the Pandemic (Univ. Zurich, 2022).

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z. & Elmagarmid, A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst. Rev. 5 , 1–10 (2016).

Tomasik, M. J., Helbling, L. A. & Moser, U. Educational gains of in-person vs. distance learning in primary and secondary schools: a natural experiment during the COVID-19 pandemic school closures in Switzerland. Int. J. Psychol. 56 , 566–576 (2021).

Eurybase: The Information Database on Education Systems in Europe (Eurydice, 2021).

Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., Higgins, J. P. & Rothstein, H. R. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Res. Synth. Methods 1 , 97–111 (2010).

Ogilvie, D. et al. The harvest plot: a method for synthesising evidence about the differential effects of interventions. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 8 , 1–7 (2008).

Gore, J., Fray, L., Miller, A., Harris, J. & Taggart, W. The impact of COVID-19 on student learning in New South Wales primary schools: an empirical study. Aust. Educ. Res. 48 , 605–637 (2021).

Gambi, L. & De Witte, K. The Resiliency of School Outcomes after the COVID-19 Pandemic: Standardised Test Scores and Inequality One Year after Long Term School Closures (FEB Research Report Department of Economics, 2021).

Maldonado, J. E. & De Witte, K. The effect of school closures on standardised student test outcomes. Br. Educ. Res. J. 48 , 49–94 (2021).

Vegas, E. COVID-19’s Impact on Learning Losses and Learning Inequality in Colombia (Center for Universal Education at Brookings, 2022).

Depping, D., Lücken, M., Musekamp, F. & Thonke, F. in Schule während der Corona-Pandemie. Neue Ergebnisse und Überblick über ein dynamisches Forschungsfeld (eds Fickermann, D. & Edelstein, B.) 51–79 (Münster & New York: Waxmann, 2021).

Ludewig, U. et al. Die COVID-19 Pandemie und Lesekompetenz von Viertklässler*innen: Ergebnisse der IFS-Schulpanelstudie 2016–2021 (Institut für Schulentwicklungsforschung, Univ. Dortmund, 2022).

Schult, J., Mahler, N., Fauth, B. & Lindner, M. A. Did students learn less during the COVID-19 pandemic? Reading and mathematics competencies before and after the first pandemic wave. Sch. Eff. Sch. Improv. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2022.2061014 (2022).

Schult, J., Mahler, N., Fauth, B. & Lindner, M. A. Long-term consequences of repeated school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic for reading and mathematics competencies. Front. Educ. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.867316 (2022).

Bazoli, N., Marzadro, S., Schizzerotto, A. & Vergolini, L. Learning Loss and Students’ Social Origins during the COVID-19 Pandemic in Italy (FBK-IRVAPP Working Papers 3, 2022).

Borgonovi, F. & Ferrara, A. The effects of COVID-19 on inequalities in educational achievement in Italy. Preprint at SSRN https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4171968 (2022).

Contini, D., Di Tommaso, M. L., Muratori, C., Piazzalunga, D. & Schiavon, L. Who lost the most? Mathematics achievement during the COVID-19 pandemic. BE J. Econ. Anal. Policy 22 , 399–408 (2022).

Engzell, P., Frey, A. & Verhagen, M. D. Learning loss due to school closures during the COVID-19 pandemic. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2022376118 (2021).

Haelermans, C. Learning Growth and Inequality in Primary Education: Policy Lessons from the COVID-19 Crisis (The European Liberal Forum (ELF)-FORES, 2021).

Haelermans, C. et al. A Full Year COVID-19 Crisis with Interrupted Learning and Two School Closures: The Effects on Learning Growth and Inequality in Primary Education (Maastricht Univ., Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market (ROA), 2021).

Haelermans, C. et al. Sharp increase in inequality in education in times of the COVID-19-pandemic. PLoS ONE 17 , e0261114 (2022).

Schuurman, T. M., Henrichs, L. F., Schuurman, N. K., Polderdijk, S. & Hornstra, L. Learning loss in vulnerable student populations after the first COVID-19 school closure in the Netherlands. Scand. J. Educ. Res. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2021.2006307 (2021).

Arenas, A. & Gortazar, L. Learning Loss One Year after School Closures (Esade Working Paper, 2022).

Hallin, A. E., Danielsson, H., Nordström, T. & Fälth, L. No learning loss in Sweden during the pandemic evidence from primary school reading assessments. Int. J. Educ. Res. 114 , 102011 (2022).

Blainey, K. & Hannay, T. The Impact of School Closures on Autumn 2020 Attainment (RS Assessment from Hodder Education and SchoolDash, 2021).

Blainey, K. & Hannay, T. The Impact of School Closures on Spring 2021 Attainment (RS Assessment from Hodder Education and SchoolDash, 2021).

Blainey, K. & Hannay, T. The Effects of Educational Disruption on Primary School Attainment in Summer 2021 (RS Assessment from Hodder Education and SchoolDash, 2021).

Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 Academic Year: Complete Findings from the Autumn Term (London: Department for Education, 2021).

Understanding Progress in the 2020/21 Academic Year: Initial Findings from the Spring Term (London: Department for Education, 2021).

Impact of COVID-19 on Attainment: Initial Analysis (Brentford: GL Assessment, 2021).

Rose, S. et al. Impact of School Closures and Subsequent Support Strategies on Attainment and Socio-emotional Wellbeing in Key Stage 1: Interim Paper 1 (National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and Education Endowment Foundation (EEF) , 2021).

Rose, S. et al. Impact of School Closures and Subsequent Support Strategies on Attainment and Socio-emotional Wellbeing in Key Stage 1: Interim Paper 2 (National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and Education Endowment Foundation (EEF), 2021).

Weidmann, B. et al. COVID-19 Disruptions: Attainment Gaps and Primary School Responses (Education Endowment Foundation, 2021).

Bielinski, J., Brown, R. & Wagner, K. No Longer a Prediction: What New Data Tell Us About the Effects of 2020 Learning Disruptions (Illuminate Education, 2021).

Domingue, B. W., Hough, H. J., Lang, D. & Yeatman, J. Changing Patterns of Growth in Oral Reading Fluency During the COVID-19 Pandemic. PACE Working Paper (Policy Analysis for California Education, 2021).

Domingue, B. et al. The effect of COVID on oral reading fluency during the 2020–2021 academic year. AERA Open https://doi.org/10.1177/23328584221120254 (2022).

Kogan, V. & Lavertu, S. The COVID-19 Pandemic and Student Achievement on Ohio’s Third-Grade English Language Arts Assessment (Ohio State Univ., 2021).

Kogan, V. & Lavertu, S. How the COVID-19 Pandemic Affected Student Learning in Ohio: Analysis of Spring 2021 Ohio State Tests (Ohio State Univ., 2021).

Kozakowski, W., Gill, B., Lavallee, P., Burnett, A. & Ladinsky, J. Changes in Academic Achievement in Pittsburgh Public Schools during Remote Instruction in the COVID-19 Pandemic (Institute of Education Sciences (IES), US Department of Education, 2020).

Kuhfeld, M. & Lewis, K. Student Achievement in 2021–2022: Cause for Hope and Continued Urgency (NWEA, 2022).

Lewis, K., Kuhfeld, M., Ruzek, E. & McEachin, A. Learning during COVID-19: Reading and Math Achievement in the 2020–21 School Year (NWEA, 2021).

Locke, V. N., Patarapichayatham, C. & Lewis, S. Learning Loss in Reading and Math in US Schools Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic (Istation, 2021).

Pier, L., Christian, M., Tymeson, H. & Meyer, R. H. COVID-19 Impacts on Student Learning: Evidence from Interim Assessments in California. PACE Working Paper (Policy Analysis for California Education, 2021).

Download references

Acknowledgements

Carlsberg Foundation grant CF19-0102 (A.M.B.-M.); Leverhulme Trust Large Centre Grant (P.E.), the Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE) grant 2016-07099 (P.E.); the French National Research Agency (ANR) as part of the ‘Investissements d’Avenir’ programme LIEPP (ANR-11-LABX-0091 and ANR-11-IDEX-0005-02) and the Université Paris Cité IdEx (ANR-18-IDEX-0001) (P.E.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Centre for Research on Social Inequalities (CRIS), Sciences Po, Paris, France

Bastian A. Betthäuser

Department of Social Policy and Intervention, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Bastian A. Betthäuser & Anders M. Bach-Mortensen

Nuffield College, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK

Bastian A. Betthäuser & Per Engzell

Social Research Institute, University College London, London, UK

Per Engzell

Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

B.A.B., A.M.B.-M. and P.E. designed the study; B.A.B., A.M.B.-M. and P.E. planned and implemented the search and screened studies; B.A.B., A.M.B.-M. and P.E. extracted relevant data from studies; B.A.B., A.M.B.-M. and P.E. conducted the quality appraisal; B.A.B., A.M.B.-M. and P.E. conducted the data analysis and visualization; B.A.B., A.M.B.-M. and P.E. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Bastian A. Betthäuser .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Guilherme Lichand, Sébastien Goudeau and Christoph König for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary methods, results, figures, tables, PRISMA Checklist and references.

Reporting Summary

Peer review file, rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Betthäuser, B.A., Bach-Mortensen, A.M. & Engzell, P. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the evidence on learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nat Hum Behav 7 , 375–385 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4

Download citation

Received : 24 June 2022

Accepted : 30 November 2022

Published : 30 January 2023

Issue Date : March 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01506-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Investigating the effect of covid-19 disruption in education using reds data.

- Alice Bertoletti

- Zbigniew Karpiński

Large-scale Assessments in Education (2024)

School reopening concerns amid a pandemic among higher education students: a developing country perspective for policy development

- Manuel B. Garcia

Educational Research for Policy and Practice (2024)

A democratic curriculum for the challenges of post-truth

- David Nally

Curriculum Perspectives (2024)

Parents’ perceptions of their child’s school adjustment during the COVID-19 pandemic: a person-oriented approach

- Sanni Pöysä

- Noona Kiuru

- Eija Pakarinen

European Journal of Psychology of Education (2024)

SGS: SqueezeNet-guided Gaussian-kernel SVM for COVID-19 Diagnosis

- Fanfeng Shi

- Vishnuvarthanan Govindaraj

Mobile Networks and Applications (2024)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Physical Review Physics Education Research

- Collections

- Editorial Team

- Open Access

Utilizing network analysis to explore student qualitative inferential reasoning chains

J. caleb speirs, mackenzie r. stetzer, and beth a. lindsey, phys. rev. phys. educ. res. 20 , 010147 – published 29 may 2024.

- No Citing Articles

Over the course of the introductory calculus-based physics course, students are often expected to build conceptual understanding and develop and refine skills in problem solving and qualitative inferential reasoning. Many of the research-based materials developed over the past 30 years by the physics education research community use sequences of scaffolded questions to step students through a qualitative inferential reasoning chain. It is often tacitly assumed that, in addition to building conceptual understanding, such materials improve qualitative reasoning skills. However, clear documentation of the impact of such materials on qualitative reasoning skills is critical. New methodologies are needed to better study reasoning processes and to disentangle, to the extent possible, processes related to physics content from processes general to all human reasoning. As a result, we have employed network analysis methodologies to examine student responses to reasoning-related tasks in order to gain deeper insight into the nature of student reasoning in physics. In this paper, we show that network analysis metrics are both interpretable and valuable when applied to student reasoning data generated from reasoning chain construction tasks . We also demonstrate that documentation of improvements in the articulation of specific lines of reasoning can be obtained from a network analysis of responses to reasoning chain construction tasks.

- Received 1 February 2023

- Revised 7 November 2023

- Accepted 26 April 2024

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.20.010147

Published by the American Physical Society under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Further distribution of this work must maintain attribution to the author(s) and the published article’s title, journal citation, and DOI.

Published by the American Physical Society

Physics Subject Headings (PhySH)

- Research Areas

Authors & Affiliations

- Department of Physics, University of North Florida, Jacksonville, Florida 32224-7699, USA