Reading & Writing Purposes

Introduction: critical thinking, reading, & writing, critical thinking.

The phrase “critical thinking” is often misunderstood. “Critical” in this case does not mean finding fault with an action or idea. Instead, it refers to the ability to understand an action or idea through reasoning. According to the website SkillsYouNeed [1]:

Critical thinking might be described as the ability to engage in reflective and independent thinking.

In essence, critical thinking requires you to use your ability to reason. It is about being an active learner rather than a passive recipient of information.

Critical thinkers rigorously question ideas and assumptions rather than accepting them at face value. They will always seek to determine whether the ideas, arguments, and findings represent the entire picture and are open to finding that they do not.

Critical thinkers will identify, analyze, and solve problems systematically rather than by intuition or instinct.

Someone with critical thinking skills can:

- Understand the links between ideas.

- Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas.

- Recognize, build, and appraise arguments.

- Identify inconsistencies and errors in reasoning.

- Approach problems in a consistent and systematic way.

- Reflect on the justification of their own assumptions, beliefs and values.

Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/learn/critical-thinking.html

Critical thinking—the ability to develop your own insights and meaning—is a basic college learning goal. Critical reading and writing strategies foster critical thinking, and critical thinking underlies critical reading and writing.

Critical Reading

Critical reading builds on the basic reading skills expected for college.

College Readers’ Characteristics

- College readers are willing to spend time reflecting on the ideas presented in their reading assignments. They know the time is well-spent to enhance their understanding.

- College readers are able to raise questions while reading. They evaluate and solve problems rather than merely compile a set of facts to be memorized.

- College readers can think logically. They are fact-oriented and can review the facts dispassionately. They base their judgments on ideas and evidence.

- College readers can recognize error in thought and persuasion as well as recognize good arguments.

- College readers are skeptical. They understand that not everything in print is correct. They are diligent in seeking out the truth.

Critical Readers’ Characteristics

- Critical readers are open-minded. They seek alternative views and are open to new ideas that may not necessarily agree with their previous thoughts on a topic. They are willing to reassess their views when new or discordant evidence is introduced and evaluated.

- Critical readers are in touch with their own personal thoughts and ideas about a topic. Excited about learning, they are eager to express their thoughts and opinions.

- Critical readers are able to identify arguments and issues. They are able to ask penetrating and thought-provoking questions to evaluate ideas.

- Critical readers are creative. They see connections between topics and use knowledge from other disciplines to enhance their reading and learning experiences.

- Critical readers develop their own ideas on issues, based on careful analysis and response to others’ ideas.

The video below, although geared toward students studying for the SAT exam (Scholastic Aptitude Test used for many colleges’ admissions), offers a good, quick overview of the concept and practice of critical reading.

Critical Reading & Writing

College reading and writing assignments often ask you to react to, apply, analyze, and synthesize information. In other words, your own informed and reasoned ideas about a subject take on more importance than someone else’s ideas, since the purpose of college reading and writing is to think critically about information.

Critical thinking involves questioning. You ask and answer questions to pursue the “careful and exact evaluation and judgment” that the word “critical” invokes (definition from The American Heritage Dictionary ). The questions simply change depending on your critical purpose. Different critical purposes are detailed in the next pages of this text.

However, here’s a brief preview of the different types of questions you’ll ask and answer in relation to different critical reading and writing purposes.

When you react to a text you ask:

- “What do I think?” and

- “Why do I think this way?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “reaction” questions about the topic assimilation of immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: I think that assimilation has both positive and negative effects because, while it makes life easier within the dominant culture, it also implies that the original culture is of lesser value.

When you apply text information you ask:

- “How does this information relate to the real world?”

e.g., If I asked and answered this “application” question about the topic assimilation , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: During the past ten years, a group of recent emigrants has assimilated into the local culture; the process of their assimilation followed certain specific stages.

When you analyze text information you ask:

- “What is the main idea?”

- “What do I want to ‘test’ in the text to see if the main idea is justified?” (supporting ideas, type of information, language), and

- “What pieces of the text relate to my ‘test?'”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “analysis” questions about the topic immigrants to the United States , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop in an essay: Although Lee (2009) states that “segmented assimilation theory asserts that immigrant groups may assimilate into one of many social sectors available in American society, instead of restricting all immigrant groups to adapting into one uniform host society,” other theorists have shown this not to be the case with recent immigrants in certain geographic areas.

When you synthesize information from many texts you ask:

- “What information is similar and different in these texts?,” and

- “What pieces of information fit together to create or support a main idea?”

e.g., If I asked and answered these “synthesis” questions about the topic immigrants to the U.S. , I might create the following main idea statement, which I could then develop by using examples and information from many text articles as evidence to support my idea: Immigrants who came to the United States during the immigration waves in the early to mid 20th century traditionally learned English as the first step toward assimilation, a process that was supported by educators. Now, both immigrant groups and educators are more focused on cultural pluralism than assimilation, as can be seen in educators’ support of bilingual education. However, although bilingual education heightens the child’s reasoning and ability to learn, it may ultimately hinder the child’s sense of security within the dominant culture if that culture does not value cultural pluralism as a whole.

Critical reading involves asking and answering these types of questions in order to find out how the information “works” as opposed to just accepting and presenting the information that you read in a text. Critical writing involves recording your insights into these questions and offering your own interpretation of a concept or issue, based on the meaning you create from those insights.

- Crtical Thinking, Reading, & Writing. Authored by : Susan Oaks, includes material adapted from TheSkillsYouNeed and Reading 100; attributions below. Project : Introduction to College Reading & Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : TheSkillsYouNeed. Located at : https://www.skillsyouneed.com/ . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright . License Terms : Quoted from website: The use of material found at skillsyouneed.com is free provided that copyright is acknowledged and a reference or link is included to the page/s where the information was found. Read more at: https://www.skillsyouneed.com/

- The Reading Process. Authored by : Scottsdale Community College Reading Faculty. Provided by : Maricopa Community College. Located at : https://learn.maricopa.edu/courses/904536/files/32966438?module_item_id=7198326 . Project : Reading 100. License : CC BY: Attribution

- image of person thinking with light bulbs saying -idea- around her head. Authored by : Gerd Altmann. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/light-bulb-idea-think-education-3704027/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video What is Critical Reading? SAT Critical Reading Bootcamp #4. Provided by : Reason Prep. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Hc3hmwnymw . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- image of man smiling and holding a lightbulb. Authored by : africaniscool. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/man-african-laughing-idea-319282/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy

Writing to Think: Critical Thinking and the Writing Process

“Writing is thinking on paper.” (Zinsser, 1976, p. vii)

Google the term “critical thinking.” How many hits are there? On the day this tutorial was completed, Google found about 65,100,000 results in 0.56 seconds. That’s an impressive number, and it grows more impressively large every day. That’s because the nation’s educators, business leaders, and political representatives worry about the level of critical thinking skills among today’s students and workers.

What is Critical Thinking?

Simply put, critical thinking is sound thinking. Critical thinkers work to delve beneath the surface of sweeping generalizations, biases, clichés, and other quick observations that characterize ineffective thinking. They are willing to consider points of view different from their own, seek and study evidence and examples, root out sloppy and illogical argument, discern fact from opinion, embrace reason over emotion or preference, and change their minds when confronted with compelling reasons to do so. In sum, critical thinkers are flexible thinkers equipped to become active and effective spouses, parents, friends, consumers, employees, citizens, and leaders. Every area of life, in other words, can be positively affected by strong critical thinking.

Released in January 2011, an important study of college students over four years concluded that by graduation “large numbers [of American undergraduates] didn’t learn the critical thinking, complex reasoning and written communication skills that are widely assumed to be at the core of a college education” (Rimer, 2011, para. 1). The University designs curriculum, creates support programs, and hires faculty to help ensure you won’t be one of the students “[showing]no significant gains in . . . ‘higher order’ thinking skills” (Rimer, 2011, para. 4). One way the University works to help you build those skills is through writing projects.

Writing and Critical Thinking

Say the word “writing” and most people think of a completed publication. But say the word “writing” to writers, and they will likely think of the process of composing. Most writers would agree with novelist E. M. Forster, who wrote, “How can I know what I think until I see what I say?” (Forster, 1927, p. 99). Experienced writers know that the act of writing stimulates thinking.

Inexperienced and experienced writers have very different understandings of composition. Novice writers often make the mistake of believing they have to know what they’re going to write before they can begin writing. They often compose a thesis statement before asking questions or conducting research. In the course of their reading, they might even disregard material that counters their pre-formed ideas. This is not writing; it is recording.

In contrast, experienced writers begin with questions and work to discover many different answers before settling on those that are most convincing. They know that the act of putting words on paper or a computer screen helps them invent thought and content. Rather than trying to express what they already think, they express what the act of writing leads them to think as they put down words. More often than not, in other words, experienced writers write their way into ideas, which they then develop, revise, and refine as they go.

What has this notion of writing to do with critical thinking? Everything.

Consider the steps of the writing process: prewriting, outlining, drafting, revising, editing, seeking feedback, and publishing. These steps are not followed in a determined or strict order; instead, the effective writer knows that as they write, it may be necessary to return to an earlier step. In other words, in the process of revision, a writer may realize that the order of ideas is unclear. A new outline may help that writer re-order details. As they write, the writer considers and reconsiders the effectiveness of the work.

The writing process, then, is not just a mirror image of the thinking process: it is the thinking process. Confronted with a topic, an effective critical thinker/writer

- asks questions

- seeks answers

- evaluates evidence

- questions assumptions

- tests hypotheses

- makes inferences

- employs logic

- draws conclusions

- predicts readers’ responses

- creates order

- drafts content

- seeks others’ responses

- weighs feedback

- criticizes their own work

- revises content and structure

- seeks clarity and coherence

Example of Composition as Critical Thinking

“Good writing is fueled by unanswerable questions” (Lane, 1993, p. 15).

Imagine that you have been asked to write about a hero or heroine from history. You must explain what challenges that individual faced and how they conquered them. Now imagine that you decide to write about Rosa Parks and her role in the modern Civil Rights movement. Take a moment and survey what you already know. She refused to get up out of her seat on a bus so a White man could sit in it. She was arrested. As a result, Blacks in Montgomery protested, influencing the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Martin Luther King, Jr. took up leadership of the cause, and ultimately a movement was born.

Is that really all there is to Rosa Parks’s story? What questions might a thoughtful writer ask? Here a few:

- Why did Rosa Parks refuse to get up on that particular day?

- Was hers a spontaneous or planned act of defiance?

- Did she work? Where? Doing what?

- Had any other Black person refused to get up for a White person?

- What happened to that individual or those individuals?

- Why hadn’t that person or those persons received the publicity Parks did?

- Was Parks active in Civil Rights before that day?

- How did she learn about civil disobedience?

Even just these few questions could lead to potentially rich information.

Factual information would not be enough, however, to satisfy an assignment that asks for an interpretation of that information. The writer’s job for the assignment is to convince the reader that Parks was a heroine; in this way the writer must make an argument and support it. The writer must establish standards of heroic behavior. More questions arise:

- What is heroic action?

- What are the characteristics of someone who is heroic?

- What do heroes value and believe?

- What are the consequences of a hero’s actions?

- Why do they matter?

Now the writer has even more research and more thinking to do.

By the time they have raised questions and answered them, raised more questions and answered them, and so on, they are ready to begin writing. But even then, new ideas will arise in the course of planning and drafting, inevitably leading the writer to more research and thought, to more composition and refinement.

Ultimately, every step of the way over the course of composing a project, the writer is engaged in critical thinking because the effective writer examines the work as they develop it.

Why Writing to Think Matters

Writing practice builds critical thinking, which empowers people to “take charge of [their] own minds” so they “can take charge of [their] own lives . . . and improve them, bringing them under [their] self command and direction” (Foundation for Critical Thinking, 2020, para. 12). Writing is a way of coming to know and understand the self and the changing world, enabling individuals to make decisions that benefit themselves, others, and society at large. Your knowledge alone – of law, medicine, business, or education, for example – will not be enough to meet future challenges. You will be tested by new unexpected circumstances, and when they arise, the open-mindedness, flexibility, reasoning, discipline, and discernment you have learned through writing practice will help you meet those challenges successfully.

Forster, E.M. (1927). Aspects of the novel . Harcourt, Brace & Company.

The Foundation for Critical Thinking. (2020, June 17). Our concept and definition of critical thinking . https://www.criticalthinking.org/pages/our-concept-of-critical-thinking/411

Lane, B. (1993). After the end: Teaching and learning creative revision . Heinemann.

Rimer, S. (2011, January 18). Study: Many college students not learning to think critically . The Hechinger Report. https://www.mcclatchydc.com/news/nation-world/national/article24608056.html

Zinsser, W. (1976). On writing well: The classic guide to writing nonfiction . HarperCollins.

Share this:

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to print (Opens in new window)

Follow Blog via Email

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive email notifications of new posts.

Email Address

- RSS - Posts

- RSS - Comments

- COLLEGE WRITING

- USING SOURCES & APA STYLE

- EFFECTIVE WRITING PODCASTS

- LEARNING FOR SUCCESS

- PLAGIARISM INFORMATION

- FACULTY RESOURCES

- Student Webinar Calendar

- Academic Success Center

- Writing Center

- About the ASC Tutors

- DIVERSITY TRAINING

- PG Peer Tutors

- PG Student Access

Subscribe to Blog via Email

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

- College Writing

- Using Sources & APA Style

- Learning for Success

- Effective Writing Podcasts

- Plagiarism Information

- Faculty Resources

- Tutor Training

Twitter feed

2. Critical Reading: Developing Critical Thinking Through Reading

When people think of high-level reasoning skills, they don’t often think if being a critical reading. Instead, they think of mathematicians and scientists, who are seen as drawing strict conclusions that follow logically from dry analysis of statistical evidence.

To be sure, mechanical, purely logical thought is a vital part of reasoning and critical thinking. But it is not everything. Critical thinking involves skills in interpretation in contexts that are multi-layered and ambiguous.

Close and critical reading is one of the best ways for students to develop skills in this kind of interpretation. As teachers think about developing critical thinking through literature they should focus on interpretive skills. Through their discussions, reflections, and reading and writing on fiction and literature, students ideally learn to develop critical thinking skills like the following:

- how to empathize with multiple perspectives;

- how to interrogate and interpret the author’s perspective;

- how to ask and engage with complex moral and philosophical questions;

- how to recognize and reckon with ambiguity.

This kind of reflection can start young — younger than we might ordinarily think. There’s a lot teachers can do to develop skills in critical thinking and reading.

Critical Reading Through Open-Ended Discussion

To facilitate growth in critical reading, teachers can build in time for open-ended discussion and resist the urge to steer students toward “correct” answers.

A good literary text is rarely able to be captured by a single interpretation. It is, of course, important to ensure students are progressing in basic comprehension skills and reading at grade level.

But when it comes to critical reading — delving into the meaning of a particular text — teachers should be open to students’ initial reflections and encourage them to express and develop their views no matter how rudimentary they might be at first.

Before engaging in more well-defined exercises and discussion, therefore, instructors can give students practice with more open-ended reflection. This will help them gain comfort and experience articulating their immediate reactions and beginning to question texts in a more structured way.

Many teachers will begin a discussion of a text with a set of questions like:

- What’s the author’s point of view or argument?

- What’s the intended audience?

- What’s the author’s purpose?

- How do they use rhetorical devices or figurative language?

This kind of questioning is, of course, important, but it can be more powerful and worthwhile to students if it comes organically out of their immediate reactions, rather than being experienced as something imposed from the outside. Otherwise, these can seem like simple questions with right or wrong answers that preclude deeper critical engagement, instead of starting points for that engagement.

For example, if a teacher wants to talk about rhetorical devices, they might begin by asking students more simply:

- What jumped out at them in the reading?

- What did it make them feel?

- What do you think produced that feeling?

A teacher can move from there to the devices that might be at work producing that effect.

Similarly, before initiating a conversation about point of view, teachers might ask:

- Did you feel able to identify with the author?

- What questions did the passage raise about the author’s identity and perspective?

Eventually, if this is well-modeled and scaffolded, the practice of interrogating point of view or rhetoric will become natural to students. They will practice critical reading organically, instead of a kind of algorithm that they are meant to apply to the text.

Critical Reading and Interpretation

Just because a text is open to interpretation doesn’t mean that there are not better and worse interpretations to offer or questions to raise. But a good interpretation cannot be measured by simply applying a preconceived standard. It shows its value in the manner in which it is backed up by evidence from the text and convincing argument.

A combination of written and spoken exercises can be useful here. Sometimes it can lead to improved contributions if students think over their views while writing before convening in small or large groups to discuss the issue. In particular, writing can help with what’s called metacognition, or thinking about thinking. Being forced to write down their views can help students step back and think about why they think what they think.

Engagement with the text should serve to broaden students’ horizons and get them to examine their own thinking and beliefs. Students have to, to a certain extent, drive this process. But teachers must facilitate discussion and exploration, and make sure it doesn’t go off the rails.

This takes skill and experience, of course, as well as confidence. Teachers must be willing to let the reins go a little bit and see where the conversation takes students. They must also be adept at facilitating: resisting the urge to intervene too forcefully or reinterpret students’ comments and, instead, encouraging other students to enter the conversation and begin responding to each other.

Finally, developing critical thinking through reading involves fostering an ability to draw connections between disparate fields. This means examining the significance of texts for one’s own experience and for broader issues in history and everyday life.

When students learn to do this, they extend some of the habits of thinking they learn through the study of literature into their daily lives. The goal is more reflective thoughtful people, who develop problem-solving skills, make better decisions and, ultimately, live more meaningful lives.

The goal is more reflective thoughtful people, who develop problem-solving skills, make better decisions and, ultimately, live more meaningful lives.

An Example of a Discussion Around Fantastic Mr. Fox

What follows is an example of a critical thinking oriented discussion and close reading exercise around Roald Dahl’s Fantastic Mr. Fox . It’s geared toward younger grades, but teachers of all levels may find ideas for how to build discussion around appropriate texts.

Toward the middle of Dahl’s story, Mr. Fox is hiding out in his foxhole with his family from three farmers (Boggis, Bunce, and Bean), who wait with guns outside the hole, attempting to starve the Foxes out.

Mr. Fox comes up with a plan to outlast them. Along with his children, he digs into the farmers’ storehouses from underneath and steals food so his family can survive. As he’s in the process of stealing he meets up with Badger, who has reservations about stealing.

Remember, again, that students shouldn’t be pushed toward any right answers, but instead prompted to dig deeper. As researcher Judith Langer puts it, when it comes to critical thinking and literature, “musing itself is the goal.”

As researcher Judith Langer puts it, when it comes to critical thinking and literature, “musing itself is the goal.”

Text from Fantastic Mr. Fox

Suddenly Badger said, “Doesn’t this worry you just a tiny bit, Foxy?”

“Worry me?” said Mr Fox. “What?”

“All this… this stealing .”

Mr. Fox stopped digging and stared at Badger as though he had gone completely dotty. “My dear old furry friend, he said, “Do you know anyone in the whole world who can refuse to steal a few chickens if his children are starving to death?”

There was a short silence while Badger thought deeply about this.

“You are far too respectable,” said Mr. Fox.

“There’s nothing wrong with being respectable,” Badger said.

“Look,” said Mr. Fox, “Boggis and Bunce and Ben are out to kill us. You realize that, I hope?”

“I do, Foxy, I do indeed,” said the gentle Badger.

“But we’re not going to be like them. We don’t want to kill them.”

“I hope not,” said Badger.

“We shall never do it,” said Mr. Fox. “We shall simply take a little food here and there to keep us and our families alive. Right?”

“I think we’ll have to,” said Badger.

Opening Discussion

After soliciting students immediate reactions, teachers might proceed by introducing more structured questions like:

- How does Mr. Fox justify stealing? Does his justification seem right to you? Why?

Many students will find Mr. Fox’s justification perfectly sound. Educators can push the conversation forward, though, by making sure that they’re giving reasons they believe his justification, however. The teacher can also complicate things by introducing new questions like the following:

- Was Mr. Fox’s stealing justified in the beginning of the book before Boggis, Bunce, and Bean attacked his foxhole? If not, what conditions would make the stealing unjustified?

Consider Perspectives

The next stage is to begin broadening perspective, and pushing students to consider more general and abstract questions:

- Why does Badger have reservations? What do you think “being respectable” means to Badger? What does it mean to Mr. Fox?

- What about the perspectives of the farmers? Should we have any sympathy for them in this situation?

Teachers can also ask students to consider their own experiences and perspectives, as well as those of their classmates.

- Have you ever been in a situation where you felt doing something that is ordinarily wrong was justified? What made it right or wrong?

Finally, teachers can use the discussion of texts like Fantastic Mr. Fox as a launch point for more abstract discussions:

- Is being “respectable” always right? When might it not be?

- What does it mean that a moral rule (like “you shouldn’t steal”) seems like it can be broken for special circumstances?

- Should we live according to principles or based on the particular context we face? Is there such a thing as being “too principled”?

Download our Teachers’ Guide

(please click here)

Sources and Resources

Beach, R., Appleman, D., Fecho, B., & Simon, R. (2016). Teaching literature to adolescents . Routledge. Focuses on inquiry-based approach to literature and uses authentic case studies. Also discusses Common Core Standards.

Gruber, S., & Boreen, J. (2003). Teaching critical thinking: Using experience to promote learning in middle school and college students . Teachers and teaching, 9(1), 5-19. Discussion of possibilities of using literature to reflection on students’ own experience, draws on philosopher John Dewey’s theory of experience.

Langer, J. A. (1992). Critical thinking and English language arts instruction . Albany: National Research Center on English Learning and Achievement. Discusses aspects of critical thinking unique to ELA (as opposed to a generic conception of critical thinking).

Martinez, M. G., Yokota, J., & Temple, C. (2017). Thinking and Learning Through Children’s Literature. Rowman & Littlefield. Overview of approaches to children’s learning with focus on making meaning; also includes research reviews and ideas for interdisciplinary instruction.

Privacy Overview

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

“Information is just bits of data. Knowledge is putting them together. Wisdom is transcending them.” —Ram Dass

“Most university students are intellectually timid … they are “good at absorbing information but slow to question the ideas they study.” — R.S . Hansen

A good place to begin to understand what is meant by critical thinking, reading, and writing is to consider how college work differs from other kinds of schoolwork you may have done.

First, think about the reading and writing you did in elementary and secondary school. Usually, elementary school children learn how to decode and write letters or characters; they might memorize grammar rules, learn basic history, and begin basic mathematics. In general, they develop a foundation for the higher order skills they will learn later. Does this sound familiar? You may have a non-traditional or different educational experience, but it is likely you went through similar stages.

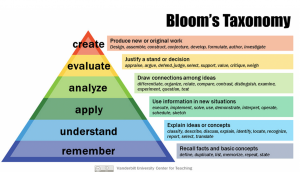

As children progress to middle school, high school, and college, their cognitive ability grows more complex, as you can see in the chart below:

(Source: Hansen, R.S. (n.d.). Ways in which college is different from high school. My CollegeSuccessStory.com .)

These cognitive phases were mapped out by American educational psychologist, Benjamin Bloom, who created a system of verbs for classifying and measuring observable actions and help us understand cognitive activity in the brain at various stages of schooling. In other words, these are the verbs that a student must do to demonstrate learning. Below is one graphic representation of Bloom’s taxonomy: The most sophisticated of these skills are the top three. They involve more critical thinking and a more advanced stage of learning than those below. While the top three skills are most associated with college-work, you will likely use all of these skills in your university assignments.

An analysis is not a summary. Summaries involve reporting concisely what an author has written. You do not include your own opinion or use judgmental vocabulary in a summary; you only include the opinions or judgments that come from the author or a source. When you analyze something, you do much more than summarize information or report an author’s opinions. Analysis means using your own views, perspectives, knowledge, or experiences.

Analysis can be a straightforward examination of each part, like an auto mechanic checking a car engine; however, in academic scholarship, it means bringing in your own perspective, opinions, observations, and evaluation .

We might analyze an author’s argument or data to see if it is strong; we might choose an element of a poem or literary work to study closely for significant elements like style, historical period, symbolism, rhyme and so forth. In the field of Engineering, one might analyze a design or code for ways to improve it.

Your purpose might be to make an argument, comparison, or connection, or offer an interpretation, reflection or evaluation. you might reach a different conclusion than the author of a study. you might report strengths or weaknesses, causes or effects, effectiveness, significance, or make an original connection. as you can see, analysis is a creative act..

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing ultimately help to structure your thinking. This means, you know how to read for different purposes, and articulate and defend your views using support or evidence. These skills will enable you to join the wider academic community of knowledge-building, expansion, and credibility.

Asking Questions

Academic analysis begins with asking good questions about what you have seen or read. Learning to question respectfully everything you encounter. This practice can strengthen your critical thinking ability and skill at examining complex issues because it involves reflecting on what you’ve seen or read and evaluating its usefulness or significance. Furthermore, it helps you question the reliability of the flow of information to which you are exposed in media.

This practice will then lead to the ability to “read between the lines” when you hear, see, or read information. This enables you to make connections or find faults in logic. Reading between the lines means making inferences, catching symbolism, or seeing an indication.

Learn more about critical thinking, critical reading, and critical writing in the chapters to come.

Critical Reading, Writing, and Thinking Copyright © 2022 by Zhenjie Weng, Josh Burlile, Karen Macbeth is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Critical Analysis: Thinking, Reading, and Writing

- What is critical thinking?

- Reading critically

Writing critically

Critical writing involves building a complex web of evidence from your sources building up to a claim of your own. It can be easy for your claims to get lost amidst those of other people. This video gives you some ideas of how to start developing an effective approach to writing critically.

If you are unable to view this video on YouTube it is also available on YuJa - view the Writing Critically video on YuJa (University username and password required)

Perfecting your paraphrasing

This video goes deeper into how to develop your paraphrasing skills, which are crucial for good critical writing. Writing evidence in your own words makes it clearer that you understand it, and it also makes your writing flow better and helps you make your voice heard.

If you are unable to view this video on YouTube it is also available on YuJa - view the Using paraphrases video on YuJa (University username and password required)

Structuring your essay

You can’t improve your critical writing without also improving your approach to essay structure. Watch this video for some helpful tips on how to get started.

If you are unable to view this video on YouTube it is also available on YuJa - view the Structuring your essay video on YuJa (University username and password required)

Find what you need to succeed.

- Our Mission

- Our Leadership

- Learning Science

- Macmillan Learning AI

- Sustainability

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Accessibility

- Astronomy Biochemistry Biology Chemistry College Success Communication Economics Electrical Engineering English Environmental Science Geography Geology History Mathematics Music & Theater Nutrition and Health Philosophy & Religion Physics Psychology Sociology Statistics Value

- Digital Offerings

- Inclusive Access

- Lab Solutions

- LMS Integration

- Curriculum Solutions

- Training and Demos

- First Day of Class

- Administrators

- Affordable Solutions

- Badging & Certification

- iClicker and Your Content

- Student Store

- News & Media

- Contact Us & FAQs

- Find Your Rep

- Booksellers

- Macmillan International Support

- International Translation Rights

- Request Permissions

- Report Piracy

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing

Related Titles

Psychology in Everyday Life

A brief guide to argument eleventh edition | ©2023 sylvan barnet; hugo bedau; john o'hara.

ISBN:9781319485566

Take notes, add highlights, and download our mobile-friendly e-books.

ISBN:9781319332051

Read and study old-school with our bound texts.

ISBN:9781319498832

This package includes Achieve and Paperback.

Affordable strategies for critical thinking and academic argument.

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing is a brief yet versatile resource for teaching argument, persuasive writing, and research. It makes argument concepts clear and gives students strategies to move from critical thinking and analysis to crafting effective arguments. Comprehensive coverage of classic and contemporary approaches to argument — Aristotelian, Toulmin, Rogerian, visual argument, and more — provides a foundation for readings on current issues that students will want to engage with. A new Consider This activity encourages students to think critically about their own decision-making and the ways argument concepts impact their experiences. This affordable guide can stand alone or supplement a larger anthology of readings.

New to This Edition

“ Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing is simple to navigate, and students enjoy the readings. Each of the chapters guides students through the different writers’ processes. There are chapters about different forms of arguments that instructors can pick-and-choose from. The textbook ultimately touches on all of our requirements.” - Max Hernandez, College of the Desert “Barnet, Bedau, and OHara offer terrific instruction in preparing the students to write arguments in the Critical Reading and Critical Thinking chapters. The chapter on analyzing argument and writing arguments of their own provides a clear understanding of the methods of supporting an argument and showing that argument is not only taking a position for or against an issue.” - Susie Crowson, Del Mar College

Eleventh Edition | ©2023

Sylvan Barnet; Hugo Bedau; John O'Hara

Digital Options

Achieve is a comprehensive set of interconnected teaching and assessment tools that incorporate the most effective elements from Macmillan Learning's market leading solutions in a single, easy-to-use platform.

Schedule Achieve Demo

Read online (or offline) with all the highlighting and notetaking tools you need to be successful in this course.

Learn About E-book

Eleventh Edition | 2023

Table of Contents

Sylvan Barnet

Sylvan Barnet was a professor of English and former director of writing at Tufts University. His several texts on writing and his numerous anthologies for introductory composition and literature courses have remained leaders in their field through many editions. His titles, with Hugo Bedau, include Current Issues and Enduring Questions; Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing ; and From Critical Thinking to Argument.

Hugo Bedau was a professor of philosophy at Tufts University and served as chair of the philosophy department and chair of the university’s committee on College Writing. An internationally respected expert on the death penalty, and on moral, legal, and political philosophy, he wrote or edited a number of books on these topics. He co-authored, with Sylvan Barnet, of Current Issues and Enduring Questions; Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing ; and From Critical Thinking to Argument.

John O'Hara

John Fitzgerald O’Hara is an associate professor of Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing at Stockton University, where he is the coordinator of the first-year critical thinking program, and former Director of the Master of Arts in American Studies Program. He regularly teaches writing, critical thinking, and courses in American literature and history and is a nationally-recognized expert on the 1960s. He is the co-author of Current Issues and Enduring Questions; Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing ; and From Critical Thinking to Argument.

Eleventh Edition | 2023

Instructor Resources

Need instructor resources for your course, download resources.

You need to sign in to unlock your resources.

Instuctor's Resource Manual for Teaching Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing

You've selected:

Click the E-mail Download Link button and we'll send you an e-mail at with links to download your instructor resources. Please note there may be a delay in delivering your e-mail depending on the size of the files.

Your download request has been received and your download link will be sent to .

Please note you could wait up to 30 to 60 minutes to receive your download e-mail depending on the number and size of the files. We appreciate your patience while we process your request.

Check your inbox, trash, and spam folders for an e-mail from [email protected] .

If you do not receive your e-mail, please visit macmillanlearning.com/support .

Current Issues and Enduring Questions

From Critical Thinking to Argument

Select a demo to view:

We are happy to offer free Achieve access in addition to the physical sample you have selected. Sample this version now as opposed to waiting for the physical edition.

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

Writing and Critical Thinking Through Literature (Ringo and Kashyap)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 40355

- Heather Ringo & Athena Kashyap

- City College of San Francisco via ASCCC Open Educational Resources Initiative

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

This text offers instruction in analytical, critical, and argumentative writing, critical thinking, research strategies, information literacy, and proper documentation through the study of literary works from major genres, while developing students’ close reading skills and promoting an appreciation of the aesthetic qualities of literature.

Thumbnail: Old book bindings at the Merton College library. (CC BY-SA 3.0; Tom Murphy VII via Wikipedia ).

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Thinking for yourself : developing critical thinking skills through reading and writing

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

111 Previews

Better World Books

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

No suitable files to display here.

PDF access not available for this item.

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by station40.cebu on November 7, 2022

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

- Writing, Research & Publishing Guides

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Follow the author

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Thinking for Yourself: Developing Critical Thinking Skills Through Reading and Writing 4th Edition

There is a newer edition of this item:.

- ISBN-10 0534518583

- ISBN-13 978-0534518585

- Edition 4th

- Publisher Wadsworth Publishing

- Publication date January 1, 1997

- Language English

- Dimensions 0.75 x 6.5 x 9.5 inches

- Print length 424 pages

- See all details

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Wadsworth Publishing; 4th edition (January 1, 1997)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 424 pages

- ISBN-10 : 0534518583

- ISBN-13 : 978-0534518585

- Item Weight : 1.25 pounds

- Dimensions : 0.75 x 6.5 x 9.5 inches

About the author

Marlys mayfield.

Marlys Mayfield has recently received the 2016 McGuffey Longevity Award in Humanities from the Textbook & Academic Authors Association for her textbook, Thinking for Yourself, now in its 9th edition. The award is named in honor of the McGuffey readers which, for over 100 years, were used in U.S. schools.

Marlys has published two books of poetry and was the author (with artist Dorr Bothwell) of a design textbook, (Notan The Dark-Light Principle of Design) first published (and still in print) since 1968.

She also began teaching English and humanities in Peralta Colleges at this time and by the 1980's her attention turned to the question as to whether thinking could be taught directly as a skill, and, moreover, improved through the mirror of writing. Thinking for Yourself was the product of that inquiry, first published by Wadsworth in 1987. For the last 29 years it has offered instructors and students a unique pedagogy based on a gradient of exercises designed to heighten awareness of the thinking/perceiving process together with a method for fully integrating critical thinking skills and standards with the skills of composition and reading.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

There was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

COMMENTS

Critical thinkers will identify, analyze, and solve problems systematically rather than by intuition or instinct. Someone with critical thinking skills can: Understand the links between ideas. Determine the importance and relevance of arguments and ideas. Recognize, build, and appraise arguments. Identify inconsistencies and errors in reasoning.

Definition of Critical Thinking. "Critical Thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.".

"Writing is thinking on paper." (Zinsser, 1976, p. vii) Google the term "critical thinking." How many hits are there? On the day this tutorial was completed, Google found about 65,100,000 results in 0.56 seconds. That's an impressive number, and it grows more impressively large every day. That's because the nation's educators, business leaders, and political…

Writers use critical writing and reading to develop and represent the processes and products of their critical thinking. For example, writers may be asked to write about familiar or unfamiliar . texts, examining assumptions about the texts held by different audiences. Through critical writing and reading, writers think through ideas, problems ...

Through their discussions, reflections, and reading and writing on fiction and literature, students ideally learn to develop critical thinking skills like the following: ... Finally, developing critical thinking through reading involves fostering an ability to draw connections between disparate fields. This means examining the significance of ...

Abstract. Critical thinking is the identification and evaluation of evidence to guide decision making. Critical reading refers to a careful, active, reflective, analytic reading. A critical thinker and a critical reader use broad, in-depth analysis of evidence to make decisions, form ideas, and communicate beliefs clearly and accurately.

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writing ultimately help to structure your thinking. This means, you know how to read for different purposes, and articulate and defend your views using support or evidence. These skills will enable you to join the wider academic community of knowledge-building, expansion, and credibility.

Critical writing involves building a complex web of evidence from your sources building up to a claim of your own. It can be easy for your claims to get lost amidst those of other people. This video gives you some ideas of how to start developing an effective approach to writing critically.

THINKING FOR YOURSELF: DEVELOPING CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS THROUGH READING AND WRITING offers a unique integration of composition, reading, and critical thinking. As you complete the book's writing assignments, you'll see how your writing reflects your thinking and how self-directed improvement in thinking also improves your writing. The book offers step-by-step instruction, humor, cartoons ...

Developing Critical Thinking t hrough Literature Reading 293. (1956) 20—knowledge and comprehension—as they fail to reflect and examine their. beliefs and actions. To initiate them into higher ...

Critical Thinking, Reading, and Writingis a brief yet versatile resource for teaching argument, persuasive writing, and research. It makes argument concepts clear and gives students strategies to move from critical thinking and analysis to crafting effective arguments. Comprehensive coverage of classic and contemporary approaches to argument ...

An explanation of critical thinking and methods for fostering critical thinking through reading are presented. Critical thinking is defined (1) as the habit of examining and weighing an idea or a thing before accepting or rejecting it and (2) as a three-factor ability consisting of attitudes, function, and knowledge. Reading is seen as an effective vehicle for influencing critical thinking ...

Another example is social emotions such as motivation, attitude, and self-efficacy toward reading and writing. These factors develop alongside reading and writing skills, creating a cycle, like the Matthew effect (Stanovich, 1980), where the gap between those who initially experience success and those who experience difficulties in reading and ...

Bought this for a critical thinking class for college a few years ago. There are probably newer versions out now. Critical thinking was the most useful class/subject studied throughout college. It should be required in high school, so teenagers and aspiring adults can think and argue more rationally.

Moreover, Reading and Writing as an integral part of Critical Thinking involves the use of partial search and research teaching methods in the introduction, development and consolidation of language. Consequently, students are encouraged to become independent and creative in the process of language acquisition, and their knowledge and skills ...

THINKING FOR YOURSELF: DEVELOPING CRITICAL THINKING SKILLS THROUGH READING AND WRITING offers a unique integration of composition, reading, and critical thinking. As you complete the book's writing assignments, you'll see how your writing reflects your thinking and how self-directed improvement in thinking also improves writing. The book offers ...

No headers. This text offers instruction in analytical, critical, and argumentative writing, critical thinking, research strategies, information literacy, and proper documentation through the study of literary works from major genres, while developing students' close reading skills and promoting an appreciation of the aesthetic qualities of literature.

Thinking for yourself : developing critical thinking skills through reading and writing ... Thinking for yourself : developing critical thinking skills through reading and writing by Mayfield, Marlys, 1931-Publication date 2007 Topics English language -- Rhetoric, Critical thinking, Academic writing

Marlys Mayfield was a pioneer in the teaching critical thinking together with writing; she began developing this book for her English composition students at the College of Alameda in 1983. At present she offers her services as a critical thinking teaching consultant.

Strategies for developing critical thinking through writing. Thesis and Argumentation: When writing, begin by clearly defining your thesis statement. Then develop a strong argument, supporting your claims with evidence and examples. Structuring and organization: A well-structured text helps readers better understand and evaluate your argument.

argumentative writing abilities employing integrative teaching of reading and writing method in conjunction with sociocultural principles and Paul and Elder's (2006, 2007) close reading strategies.

The objectives of the present study were to investigate whether students' creative thinking can be enhanced through a structured program of reading and writing activities in the context of a cooperative learning classroom, and to test for a possible correlation between improvements in creative thinking and improvements in academic performance. Sixty fifth-grade students from a primary school ...

1. Introduction. The study of creative thinking in school-age children sparks great interest for researchers and educators in the possibility that typical classroom learning activities like reading and writing, when implemented in a nurturing context, could promote cognitive and creative skills (Flower et al., 1990; Squire, 1983; Wang, 2012).This question is especially important as studies of ...

Apart from boosting literacy, reading literary works also functions to develop students' critical thinking. The Minister of Education, Culture, Research, and Technology, Nadiem Anwar Makarim, stated that the utilization of literary works in learning has been implemented in several classes. However, its usage is still limited to Indonesian ...