- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case NPS+ Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Data Collection: What It Is, Methods & Tools + Examples

Let’s face it, no one wants to make decisions based on guesswork or gut feelings. The most important objective of data collection is to ensure that the data gathered is reliable and packed to the brim with juicy insights that can be analyzed and turned into data-driven decisions. There’s nothing better than good statistical analysis .

LEARN ABOUT: Level of Analysis

Collecting high-quality data is essential for conducting market research, analyzing user behavior, or just trying to get a handle on business operations. With the right approach and a few handy tools, gathering reliable and informative data.

So, let’s get ready to collect some data because when it comes to data collection, it’s all about the details.

Content Index

What is Data Collection?

Data collection methods, data collection examples, reasons to conduct online research and data collection, conducting customer surveys for data collection to multiply sales, steps to effectively conduct an online survey for data collection, survey design for data collection.

Data collection is the procedure of collecting, measuring, and analyzing accurate insights for research using standard validated techniques.

Put simply, data collection is the process of gathering information for a specific purpose. It can be used to answer research questions, make informed business decisions, or improve products and services.

To collect data, we must first identify what information we need and how we will collect it. We can also evaluate a hypothesis based on collected data. In most cases, data collection is the primary and most important step for research. The approach to data collection is different for different fields of study, depending on the required information.

LEARN ABOUT: Action Research

There are many ways to collect information when doing research. The data collection methods that the researcher chooses will depend on the research question posed. Some data collection methods include surveys, interviews, tests, physiological evaluations, observations, reviews of existing records, and biological samples. Let’s explore them.

LEARN ABOUT: Best Data Collection Tools

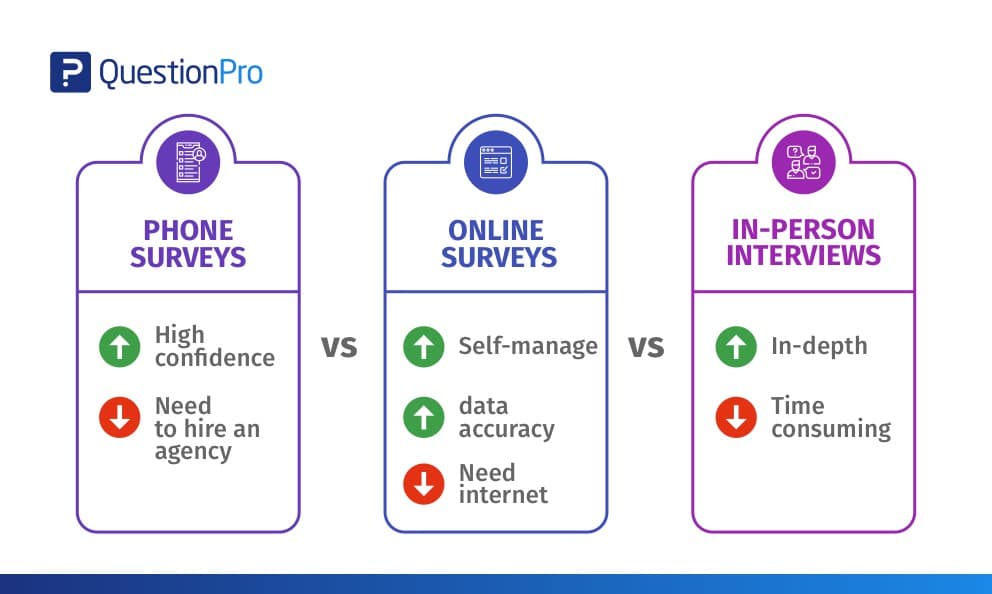

Phone vs. Online vs. In-Person Interviews

Essentially there are four choices for data collection – in-person interviews, mail, phone, and online. There are pros and cons to each of these modes.

- Pros: In-depth and a high degree of confidence in the data

- Cons: Time-consuming, expensive, and can be dismissed as anecdotal

- Pros: Can reach anyone and everyone – no barrier

- Cons: Expensive, data collection errors, lag time

- Pros: High degree of confidence in the data collected, reach almost anyone

- Cons: Expensive, cannot self-administer, need to hire an agency

- Pros: Cheap, can self-administer, very low probability of data errors

- Cons: Not all your customers might have an email address/be on the internet, customers may be wary of divulging information online.

In-person interviews always are better, but the big drawback is the trap you might fall into if you don’t do them regularly. It is expensive to regularly conduct interviews and not conducting enough interviews might give you false positives. Validating your research is almost as important as designing and conducting it.

We’ve seen many instances where after the research is conducted – if the results do not match up with the “gut-feel” of upper management, it has been dismissed off as anecdotal and a “one-time” phenomenon. To avoid such traps, we strongly recommend that data-collection be done on an “ongoing and regular” basis.

LEARN ABOUT: Research Process Steps

This will help you compare and analyze the change in perceptions according to marketing for your products/services. The other issue here is sample size. To be confident with your research, you must interview enough people to weed out the fringe elements.

A couple of years ago there was a lot of discussion about online surveys and their statistical analysis plan . The fact that not every customer had internet connectivity was one of the main concerns.

LEARN ABOUT: Statistical Analysis Methods

Although some of the discussions are still valid, the reach of the internet as a means of communication has become vital in the majority of customer interactions. According to the US Census Bureau, the number of households with computers has doubled between 1997 and 2001.

Learn more: Quantitative Market Research

In 2001 nearly 50% of households had a computer. Nearly 55% of all households with an income of more than 35,000 have internet access, which jumps to 70% for households with an annual income of 50,000. This data is from the US Census Bureau for 2001.

There are primarily three modes of data collection that can be employed to gather feedback – Mail, Phone, and Online. The method actually used for data collection is really a cost-benefit analysis. There is no slam-dunk solution but you can use the table below to understand the risks and advantages associated with each of the mediums:

Keep in mind, the reach here is defined as “All U.S. Households.” In most cases, you need to look at how many of your customers are online and determine. If all your customers have email addresses, you have a 100% reach of your customers.

Another important thing to keep in mind is the ever-increasing dominance of cellular phones over landline phones. United States FCC rules prevent automated dialing and calling cellular phone numbers and there is a noticeable trend towards people having cellular phones as the only voice communication device.

This introduces the inability to reach cellular phone customers who are dropping home phone lines in favor of going entirely wireless. Even if automated dialing is not used, another FCC rule prohibits from phoning anyone who would have to pay for the call.

Learn more: Qualitative Market Research

Multi-Mode Surveys

Surveys, where the data is collected via different modes (online, paper, phone etc.), is also another way of going. It is fairly straightforward and easy to have an online survey and have data-entry operators to enter in data (from the phone as well as paper surveys) into the system. The same system can also be used to collect data directly from the respondents.

Learn more: Survey Research

Data collection is an important aspect of research. Let’s consider an example of a mobile manufacturer, company X, which is launching a new product variant. To conduct research about features, price range, target market, competitor analysis, etc. data has to be collected from appropriate sources.

The marketing team can conduct various data collection activities such as online surveys or focus groups .

The survey should have all the right questions about features and pricing, such as “What are the top 3 features expected from an upcoming product?” or “How much are your likely to spend on this product?” or “Which competitors provide similar products?” etc.

For conducting a focus group, the marketing team should decide the participants and the mediator. The topic of discussion and objective behind conducting a focus group should be clarified beforehand to conduct a conclusive discussion.

Data collection methods are chosen depending on the available resources. For example, conducting questionnaires and surveys would require the least resources, while focus groups require moderately high resources.

Feedback is a vital part of any organization’s growth. Whether you conduct regular focus groups to elicit information from key players or, your account manager calls up all your marquee accounts to find out how things are going – essentially they are all processes to find out from your customers’ eyes – How are we doing? What can we do better?

Online surveys are just another medium to collect feedback from your customers , employees and anyone your business interacts with. With the advent of Do-It-Yourself tools for online surveys, data collection on the internet has become really easy, cheap and effective.

Learn more: Online Research

It is a well-established marketing fact that acquiring a new customer is 10 times more difficult and expensive than retaining an existing one. This is one of the fundamental driving forces behind the extensive adoption and interest in CRM and related customer retention tactics.

In a research study conducted by Rice University Professor Dr. Paul Dholakia and Dr. Vicki Morwitz, published in Harvard Business Review, the experiment inferred that the simple fact of asking customers how an organization was performing by itself to deliver results proved to be an effective customer retention strategy.

In the research study, conducted over the course of a year, one set of customers were sent out a satisfaction and opinion survey and the other set was not surveyed. In the next one year, the group that took the survey saw twice the number of people continuing and renewing their loyalty towards the organization data .

Learn more: Research Design

The research study provided a couple of interesting reasons on the basis of consumer psychology, behind this phenomenon:

- Satisfaction surveys boost the customers’ desire to be coddled and induce positive feelings. This crops from a section of the human psychology that intends to “appreciate” a product or service they already like or prefer. The survey feedback collection method is solely a medium to convey this. The survey is a vehicle to “interact” with the company and reinforces the customer’s commitment to the company.

- Surveys may increase awareness of auxiliary products and services. Surveys can be considered modes of both inbound as well as outbound communication. Surveys are generally considered to be a data collection and analysis source. Most people are unaware of the fact that consumer surveys can also serve as a medium for distributing data. It is important to note a few caveats here.

- In most countries, including the US, “selling under the guise of research” is illegal. b. However, we all know that information is distributed while collecting information. c. Other disclaimers may be included in the survey to ensure users are aware of this fact. For example: “We will collect your opinion and inform you about products and services that have come online in the last year…”

- Induced Judgments: The entire procedure of asking people for their feedback can prompt them to build an opinion on something they otherwise would not have thought about. This is a very underlying yet powerful argument that can be compared to the “Product Placement” strategy currently used for marketing products in mass media like movies and television shows. One example is the extensive and exclusive use of the “mini-Cooper” in the blockbuster movie “Italian Job.” This strategy is questionable and should be used with great caution.

Surveys should be considered as a critical tool in the customer journey dialog. The best thing about surveys is its ability to carry “bi-directional” information. The research conducted by Paul Dholakia and Vicki Morwitz shows that surveys not only get you the information that is critical for your business, but also enhances and builds upon the established relationship you have with your customers.

Recent technological advances have made it incredibly easy to conduct real-time surveys and opinion polls . Online tools make it easy to frame questions and answers and create surveys on the Web. Distributing surveys via email, website links or even integration with online CRM tools like Salesforce.com have made online surveying a quick-win solution.

So, you’ve decided to conduct an online survey. There are a few questions in your mind that you would like answered, and you are looking for a fast and inexpensive way to find out more about your customers, clients, etc.

First and foremost thing you need to decide what the smart objectives of the study are. Ensure that you can phrase these objectives as questions or measurements. If you can’t, you are better off looking at other data sources like focus groups and other qualitative methods . The data collected via online surveys is dominantly quantitative in nature.

Review the basic objectives of the study. What are you trying to discover? What actions do you want to take as a result of the survey? – Answers to these questions help in validating collected data. Online surveys are just one way of collecting and quantifying data .

Learn more: Qualitative Data & Qualitative Data Collection Methods

- Visualize all of the relevant information items you would like to have. What will the output survey research report look like? What charts and graphs will be prepared? What information do you need to be assured that action is warranted?

- Assign ranks to each topic (1 and 2) according to their priority, including the most important topics first. Revisit these items again to ensure that the objectives, topics, and information you need are appropriate. Remember, you can’t solve the research problem if you ask the wrong questions.

- How easy or difficult is it for the respondent to provide information on each topic? If it is difficult, is there an alternative medium to gain insights by asking a different question? This is probably the most important step. Online surveys have to be Precise, Clear and Concise. Due to the nature of the internet and the fluctuations involved, if your questions are too difficult to understand, the survey dropout rate will be high.

- Create a sequence for the topics that are unbiased. Make sure that the questions asked first do not bias the results of the next questions. Sometimes providing too much information, or disclosing purpose of the study can create bias. Once you have a series of decided topics, you can have a basic structure of a survey. It is always advisable to add an “Introductory” paragraph before the survey to explain the project objective and what is expected of the respondent. It is also sensible to have a “Thank You” text as well as information about where to find the results of the survey when they are published.

- Page Breaks – The attention span of respondents can be very low when it comes to a long scrolling survey. Add page breaks as wherever possible. Having said that, a single question per page can also hamper response rates as it increases the time to complete the survey as well as increases the chances for dropouts.

- Branching – Create smart and effective surveys with the implementation of branching wherever required. Eliminate the use of text such as, “If you answered No to Q1 then Answer Q4” – this leads to annoyance amongst respondents which result in increase survey dropout rates. Design online surveys using the branching logic so that appropriate questions are automatically routed based on previous responses.

- Write the questions . Initially, write a significant number of survey questions out of which you can use the one which is best suited for the survey. Divide the survey into sections so that respondents do not get confused seeing a long list of questions.

- Sequence the questions so that they are unbiased.

- Repeat all of the steps above to find any major holes. Are the questions really answered? Have someone review it for you.

- Time the length of the survey. A survey should take less than five minutes. At three to four research questions per minute, you are limited to about 15 questions. One open end text question counts for three multiple choice questions. Most online software tools will record the time taken for the respondents to answer questions.

- Include a few open-ended survey questions that support your survey object. This will be a type of feedback survey.

- Send an email to the project survey to your test group and then email the feedback survey afterward.

- This way, you can have your test group provide their opinion about the functionality as well as usability of your project survey by using the feedback survey.

- Make changes to your questionnaire based on the received feedback.

- Send the survey out to all your respondents!

Online surveys have, over the course of time, evolved into an effective alternative to expensive mail or telephone surveys. However, you must be aware of a few conditions that need to be met for online surveys. If you are trying to survey a sample representing the target population, please remember that not everyone is online.

Moreover, not everyone is receptive to an online survey also. Generally, the demographic segmentation of younger individuals is inclined toward responding to an online survey.

Learn More: Examples of Qualitarive Data in Education

Good survey design is crucial for accurate data collection. From question-wording to response options, let’s explore how to create effective surveys that yield valuable insights with our tips to survey design.

- Writing Great Questions for data collection

Writing great questions can be considered an art. Art always requires a significant amount of hard work, practice, and help from others.

The questions in a survey need to be clear, concise, and unbiased. A poorly worded question or a question with leading language can result in inaccurate or irrelevant responses, ultimately impacting the data’s validity.

Moreover, the questions should be relevant and specific to the research objectives. Questions that are irrelevant or do not capture the necessary information can lead to incomplete or inconsistent responses too.

- Avoid loaded or leading words or questions

A small change in content can produce effective results. Words such as could , should and might are all used for almost the same purpose, but may produce a 20% difference in agreement to a question. For example, “The management could.. should.. might.. have shut the factory”.

Intense words such as – prohibit or action, representing control or action, produce similar results. For example, “Do you believe Donald Trump should prohibit insurance companies from raising rates?”.

Sometimes the content is just biased. For instance, “You wouldn’t want to go to Rudolpho’s Restaurant for the organization’s annual party, would you?”

- Misplaced questions

Questions should always reference the intended context, and questions placed out of order or without its requirement should be avoided. Generally, a funnel approach should be implemented – generic questions should be included in the initial section of the questionnaire as a warm-up and specific ones should follow. Toward the end, demographic or geographic questions should be included.

- Mutually non-overlapping response categories

Multiple-choice answers should be mutually unique to provide distinct choices. Overlapping answer options frustrate the respondent and make interpretation difficult at best. Also, the questions should always be precise.

For example: “Do you like water juice?”

This question is vague. In which terms is the liking for orange juice is to be rated? – Sweetness, texture, price, nutrition etc.

- Avoid the use of confusing/unfamiliar words

Asking about industry-related terms such as caloric content, bits, bytes, MBS , as well as other terms and acronyms can confuse respondents . Ensure that the audience understands your language level, terminology, and, above all, the question you ask.

- Non-directed questions give respondents excessive leeway

In survey design for data collection, non-directed questions can give respondents excessive leeway, which can lead to vague and unreliable data. These types of questions are also known as open-ended questions, and they do not provide any structure for the respondent to follow.

For instance, a non-directed question like “ What suggestions do you have for improving our shoes?” can elicit a wide range of answers, some of which may not be relevant to the research objectives. Some respondents may give short answers, while others may provide lengthy and detailed responses, making comparing and analyzing the data challenging.

To avoid these issues, it’s essential to ask direct questions that are specific and have a clear structure. Closed-ended questions, for example, offer structured response options and can be easier to analyze as they provide a quantitative measure of respondents’ opinions.

- Never force questions

There will always be certain questions that cross certain privacy rules. Since privacy is an important issue for most people, these questions should either be eliminated from the survey or not be kept as mandatory. Survey questions about income, family income, status, religious and political beliefs, etc., should always be avoided as they are considered to be intruding, and respondents can choose not to answer them.

- Unbalanced answer options in scales

Unbalanced answer options in scales such as Likert Scale and Semantic Scale may be appropriate for some situations and biased in others. When analyzing a pattern in eating habits, a study used a quantity scale that made obese people appear in the middle of the scale with the polar ends reflecting a state where people starve and an irrational amount to consume. There are cases where we usually do not expect poor service, such as hospitals.

- Questions that cover two points

In survey design for data collection, questions that cover two points can be problematic for several reasons. These types of questions are often called “double-barreled” questions and can cause confusion for respondents, leading to inaccurate or irrelevant data.

For instance, a question like “Do you like the food and the service at the restaurant?” covers two points, the food and the service, and it assumes that the respondent has the same opinion about both. If the respondent only liked the food, their opinion of the service could affect their answer.

It’s important to ask one question at a time to avoid confusion and ensure that the respondent’s answer is focused and accurate. This also applies to questions with multiple concepts or ideas. In these cases, it’s best to break down the question into multiple questions that address each concept or idea separately.

- Dichotomous questions

Dichotomous questions are used in case you want a distinct answer, such as: Yes/No or Male/Female . For example, the question “Do you think this candidate will win the election?” can be Yes or No.

- Avoid the use of long questions

The use of long questions will definitely increase the time taken for completion, which will generally lead to an increase in the survey dropout rate. Multiple-choice questions are the longest and most complex, and open-ended questions are the shortest and easiest to answer.

Data collection is an essential part of the research process, whether you’re conducting scientific experiments, market research, or surveys. The methods and tools used for data collection will vary depending on the research type, the sample size required, and the resources available.

Several data collection methods include surveys, observations, interviews, and focus groups. We learn each method has advantages and disadvantages, and choosing the one that best suits the research goals is important.

With the rise of technology, many tools are now available to facilitate data collection, including online survey software and data visualization tools. These tools can help researchers collect, store, and analyze data more efficiently, providing greater results and accuracy.

By understanding the various methods and tools available for data collection, we can develop a solid foundation for conducting research. With these research skills , we can make informed decisions, solve problems, and contribute to advancing our understanding of the world around us.

Analyze your survey data to gauge in-depth market drivers, including competitive intelligence, purchasing behavior, and price sensitivity, with QuestionPro.

You will obtain accurate insights with various techniques, including conjoint analysis, MaxDiff analysis, sentiment analysis, TURF analysis, heatmap analysis, etc. Export quality data to external in-depth analysis tools such as SPSS and R Software, and integrate your research with external business applications. Everything you need for your data collection. Start today for free!

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Cannabis Industry Business Intelligence: Impact on Research

May 28, 2024

Top 10 Dynata Alternatives & Competitors

May 27, 2024

What Are My Employees Really Thinking? The Power of Open-ended Survey Analysis

May 24, 2024

I Am Disconnected – Tuesday CX Thoughts

May 21, 2024

Other categories

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Uncategorized

- Video Learning Series

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

- Data Science

Caltech Bootcamp / Blog / /

Data Collection Methods: A Comprehensive View

- Written by John Terra

- Updated on February 21, 2024

Companies that want to be competitive in today’s digital economy enjoy the benefit of countless reams of data available for market research. In fact, thanks to the advent of big data, there’s a veritable tidal wave of information ready to be put to good use, helping businesses make intelligent decisions and thrive.

But before that data can be used, it must be processed. But before it can be processed, it must be collected, and that’s what we’re here for. This article explores the subject of data collection. We will learn about the types of data collection methods and why they are essential.

We will detail primary and secondary data collection methods and discuss data collection procedures. We’ll also share how you can learn practical skills through online data science training.

But first, let’s get the definition out of the way. What is data collection?

What is Data Collection?

Data collection is the act of collecting, measuring and analyzing different kinds of information using a set of validated standard procedures and techniques. The primary objective of data collection procedures is to gather reliable, information-rich data and analyze it to make critical business decisions. Once the desired data is collected, it undergoes a process of data cleaning and processing to make the information actionable and valuable for businesses.

Your choice of data collection method (or alternately called a data gathering procedure) depends on the research questions you’re working on, the type of data required, and the available time and resources and time. You can categorize data-gathering procedures into two main methods:

- Primary data collection . Primary data is collected via first-hand experiences and does not reference or use the past. The data obtained by primary data collection methods is exceptionally accurate and geared to the research’s motive. They are divided into two categories: quantitative and qualitative. We’ll explore the specifics later.

- Secondary data collection. Secondary data is the information that’s been used in the past. The researcher can obtain data from internal and external sources, including organizational data.

Let’s take a closer look at specific examples of both data collection methods.

Also Read: Why Use Python for Data Science?

The Specific Types of Data Collection Methods

As mentioned, primary data collection methods are split into quantitative and qualitative. We will examine each method’s data collection tools separately. Then, we will discuss secondary data collection methods.

Quantitative Methods

Quantitative techniques for demand forecasting and market research typically use statistical tools. When using these techniques, historical data is used to forecast demand. These primary data-gathering procedures are most often used to make long-term forecasts. Statistical analysis methods are highly reliable because they carry minimal subjectivity.

- Barometric Method. Also called the leading indicators approach, data analysts and researchers employ this method to speculate on future trends based on current developments. When past events are used to predict future events, they are considered leading indicators.

- Smoothing Techniques. Smoothing techniques can be used in cases where the time series lacks significant trends. These techniques eliminate random variation from historical demand and help identify demand levels and patterns to estimate future demand. The most popular methods used in these techniques are the simple moving average and the weighted moving average methods.

- Time Series Analysis. The term “time series” refers to the sequential order of values in a variable, also known as a trend, at equal time intervals. Using patterns, organizations can predict customer demand for their products and services during the projected time.

Qualitative Methods

Qualitative data collection methods are instrumental when no historical information is available, or numbers and mathematical calculations aren’t required. Qualitative research is closely linked to words, emotions, sounds, feelings, colors, and other non-quantifiable elements. These techniques rely on experience, conjecture, intuition, judgment, emotion, etc. Quantitative methods do not provide motives behind the participants’ responses. Additionally, they often don’t reach underrepresented populations and usually involve long data collection periods. Therefore, you get the best results using quantitative and qualitative methods together.

- Questionnaires . Questionnaires are a printed set of either open-ended or closed-ended questions. Respondents must answer based on their experience and knowledge of the issue. A questionnaire is a part of a survey, while the questionnaire’s end goal doesn’t necessarily have to be a survey.

- Surveys. Surveys collect data from target audiences, gathering insights into their opinions, preferences, choices, and feedback on the organization’s goods and services. Most survey software has a wide range of question types, or you can also use a ready-made survey template that saves time and effort. Surveys can be distributed via different channels such as e-mail, offline apps, websites, social media, QR codes, etc.

Once researchers collect the data, survey software generates reports and runs analytics algorithms to uncover hidden insights. Survey dashboards give you statistics relating to completion rates, response rates, filters based on demographics, export and sharing options, etc. Practical business intelligence depends on the synergy between analytics and reporting. Analytics uncovers valuable insights while reporting communicates these findings to the stakeholders.

- Polls. Polls consist of one or more multiple-choice questions. Marketers can turn to polls when they want to take a quick snapshot of the audience’s sentiments. Since polls tend to be short, getting people to respond is more manageable. Like surveys, online polls can be embedded into various media and platforms. Once the respondents answer the question(s), they can be shown how they stand concerning other people’s responses.

- Delphi Technique. The name is a callback to the Oracle of Delphi, a priestess at Apollo’s temple in ancient Greece, renowned for her prophecies. In this method, marketing experts are given the forecast estimates and assumptions made by other industry experts. The first batch of experts may then use the information provided by the other experts to revise and reconsider their estimates and assumptions. The total expert consensus on the demand forecasts creates the final demand forecast.

- Interviews. In this method, interviewers talk to the respondents either face-to-face or by telephone. In the first case, the interviewer asks the interviewee a series of questions in person and notes the responses. The interviewer can opt for a telephone interview if the parties cannot meet in person. This data collection form is practical for use with only a few respondents; repeating the same process with a considerably larger group takes longer.

- Focus Groups. Focus groups are one of the primary examples of qualitative data in education. In focus groups, small groups of people, usually around 8-10 members, discuss the research problem’s common aspects. Each person provides their insights on the issue, and a moderator regulates the discussion. When the discussion ends, the group reaches a consensus.

Also Read: A Beginner’s Guide to the Data Science Process

Secondary Data Collection Methods

Secondary data is the information that’s been used in past situations. Secondary data collection methods can include quantitative and qualitative techniques. In addition, secondary data is easily available, so it’s less time-consuming and expensive than using primary data. However, the authenticity of data gathered with secondary data collection tools cannot be verified.

Internal secondary data sources:

- CRM Software

- Executive summaries

- Financial Statements

- Mission and vision statements

- Organization’s health and safety records

- Sales Reports

External secondary data sources:

- Business journals

- Government reports

- Press releases

The Importance of Data Collection Methods

Data collection methods play a critical part in the research process as they determine the accuracy and quality and accuracy of the collected data. Here’s a sample of some reasons why data collection procedures are so important:

- They determine the quality and accuracy of collected data

- They ensure the data and the research findings are valid, relevant and reliable

- They help reduce bias and increase the sample’s representation

- They are crucial for making informed decisions and arriving at accurate conclusions

- They provide accurate data, which facilitates the achievement of research objectives

Also Read: What Is Data Processing? Definition, Examples, Trends

So, What’s the Difference Between Data Collecting and Data Processing?

Data collection is the first step in the data processing process. Data collection involves gathering information (raw data) from various sources such as interviews, surveys, questionnaires, etc. Data processing describes the steps taken to organize, manipulate and transform the collected data into a useful and meaningful resource. This process may include tasks such as cleaning and validating data, analyzing and summarizing data, and creating visualizations or reports.

So, data collection is just one step in the overall data processing chain of events.

Do You Want to Become a Data Scientist?

If this discussion about data collection and the professionals who conduct it has sparked your enthusiasm for a new career, why not check out this online data science program ?

The Glassdoor.com jobs website shows that data scientists in the United States typically make an average yearly salary of $129,127 plus additional bonuses and cash incentives. So, if you’re interested in a new career or are already in the field but want to upskill or refresh your current skill set, sign up for this bootcamp and prepare to tackle the challenges of today’s big data.

You might also like to read:

Navigating Data Scientist Roles and Responsibilities in Today’s Market

Differences Between Data Scientist and Data Analyst: Complete Explanation

What Is Data Collection? A Guide for Aspiring Data Scientists

A Data Scientist Job Description: The Roles and Responsibilities in 2024

Top Data Science Projects With Source Code to Try

Data Science Bootcamp

- Learning Format:

Online Bootcamp

Leave a comment cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Recommended Articles

What is Exploratory Data Analysis? Types, Tools, Importance, etc.

This article highlights exploratory data analysis, including its definition, role in data science, types, and overall importance.

What is Data Wrangling? Importance, Tools, and More

This article explores data wrangling, including its definition, importance, steps, benefits, and tools.

What is Spatial Data Science? Definition, Applications, Careers & More

Do you want to know what spatial data science is? Read this guide to learn its basics, real-world applications, and the exciting career options in this field.

Data Science and Marketing: Transforming Strategies and Enhancing Engagement

Employing data science in marketing is critical for any organization today. This blog explores this intersection of the two disciplines and how professionals and businesses can ensure they have the skills to drive successful digital marketing strategies.

An Introduction to Natural Language Processing in Data Science

Natural language processing may seem straightforward, but there’s a lot going on behind the scenes. This blog explores NLP in data science.

Why Use Python for Data Science?

This article explains why you should use Python for data science tasks, including how it’s done and the benefits.

Learning Format

Program Benefits

- 12+ tools covered, 25+ hands-on projects

- Masterclasses by distinguished Caltech CTME instructors

- Caltech CTME Circle Membership

- Industry-specific training from global experts

- Call us on : 1800-212-7688

Qualitative Study Design and Data Collection

- First Online: 10 February 2022

Cite this chapter

- Charles P. Friedman 4 ,

- Jeremy C. Wyatt 5 &

- Joan S. Ash 6

Part of the book series: Health Informatics ((HI))

While the prior chapter set the stage for an understanding of the nature of qualitative evaluation, this chapter will offer strategies for planning a study and making decisions about how to gather data. The process is depicted as an iterative looping through steps beginning with idea generation to dissemination of results. It is critical that strategies for rigor be incorporated throughout the process. This chapter outlines methods for data collection utilizing interviews, focus groups, observation, and naturally occurring data, and then it also describes combinations often used together, which constitute toolkits of complementary techniques.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

This is of course a major point of departure between qualitative methods and their quantitative counterparts. In quantitative work, investigators rarely acknowledge bias, and if they do, they may be disqualified from participating in the study.

For the same reasons, the observers should not dress too formally. They should dress as comparably as possible to the workers being observed in the field. Always ask ahead of time about dress codes.

Ash JS, Chin HL, Sittig DF, Dykstra R. Ambulatory computerized physician order entry implementation. Proc Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;2005:11–5.

Google Scholar

Ash JS, Sittig DF, McMullen CK, Wright A, Bunce A, Mohan V, Cohen DJ, Middleton B. Multiple perspectives on clinical decision support: a qualitative study of fifteen clinical and vendor organizations. BMC Med Inform Decision Making. 2015 Apr 24;15:35.

Article Google Scholar

Beebe J. Rapid assessment process: an introduction. Lanham, PA: AltaMira Press; 2001.

Berg BL, Lune H. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. 8th ed. Boston: Pearson; 2012.

Brunet LW, Morrissey CY, Gorry GA. Oral history and information technology: human voices of assessment. J Org Comput. 1991;1:251–74.

Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999.

Davis FD, Bagozzi RP, Warshaw PR. User acceptance of computer technology: a comparison of two theoretical models. Manag Sci. 1989;35:982–1003.

Erickson K, Stull D. Doing team ethnography: warnings and advice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

Book Google Scholar

Gaglio B, Shoup JA, Glasgow RE. The RE-AIM framework: a systematic review of use over time. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e38–46.

Glaser BG, Strauss A. Discovery of grounded theory. Strategies for qualitative research. Mill Valley, CA: Sociology Press; 1967.

Goedhart NS, Zuiderent-Jerak T, Woudstra J, Broerse JEW, Betten AW, Dedding C. Persistent inequitable design and implementation of patient portals for users at the margins. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:276–83.

Hussain MI, Figuerredo MC, Tran BD, Su Z, Molldrem S, Eikey EV, Chen Y. A scoping review of qualitative research in JAMIA: past contributions and opportunities for future work. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2021;28:402–13.

Kiyimba N, Lester JN, O’Reilly M. Using naturally occurring data in qualitative Health Research: a practical guide. Amsterdam: Springer; 2019.

Leedy PD, Ormrod JE. Practical research: planning and design. 11th ed. Pearson: Boston, MA; 2016.

Linstone H. Multiple perspectives for decision making: bridging the gap between analysis and action. North-Holland Elsevier: Amsterdam, NE; 1984.

McMullen CK, Ash JS, Sittig DF, Bunce A, Guappone K, Dykstra R, et al. Rapid assessment of clinical information systems in the healthcare setting: an efficient method for time-pressed evaluation. Methods Inform Med. 2011;50:299–307.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Miles MB, Huberman AM. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994.

Mohan V, Woodcock D, McGrath K, Scholl G, Pransat R, Doberne JW, et al. Using simulations to improve electronic health record use, clinician training and patient safety: recommendations from a consensus conference. AMIA Ann Symp Proc. 2016;2016:904–13.

Morgan DL, Krueger RA. The focus group kit. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

NIH Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research. Qualitative methods in health research: opportunities and considerations in application and review. NIH Publication No. 02-!5046, December 2001.

Patton MQ. Qualitative evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1980.

Pope C, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2020.

Rubin HJ, Rubin IS. Qualitative interviewing: the art of hearing data. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1995.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of qualitative research: grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1990.

Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM. Qualitative methods in public health: a field guide for applied research. Hoboken NJ: Wiley; 2016.

University of Technology Sydney. Adapting research methods in the COVID-19 pandemic: resources for researchers, 2nd ed. UTS and University of Washington, December, 2020.

Weinstein JN, Caciu A, editors. Communities in action: pathways to health equity. New York: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, National Academies Press; 2017.

Yin RK. Case study research: design and methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Learning Health Sciences, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

Charles P. Friedman

Department of Primary Care, Population Sciences and Medical Education, School of Medicine, University of Southampton, Southampton, UK

Jeremy C. Wyatt

Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology, School of Medicine, Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, OR, USA

Joan S. Ash

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Charles P. Friedman .

Answers to Self-Tests

Self-test 15.1.

Which of the strategies to ensure study rigor is primarily employed in the qualitative study scenarios below:

Data from interviews about the usability of a resource are analyzed thematically. The evaluation study team looks to see if and how similar themes have arisen in earlier meetings of the team.

Audit trail

A member of the study team, who has recently participated in another study of a similar kind of resource, becomes concerned that that person’s views about the current study are being shaped by that previous experience. That person sits with another member of the study team to share that person’s concerns and put them in perspective.

Reflexivity

At a “town hall” meeting called to present the results of a qualitative study, the sponsor of the study raises deep and serious questions about the validity of the findings. The study team returns to notes from their team meetings to review how and based on what data they came to this conclusion.

Member checking

During an evaluation project team meeting, one of the study team members finds themselves deeply repelled by off-color comments made by one of the project staff. The team member makes a note of this personal response as part of field notes.

After interviewing 10 patients participating in a study, a study team member perceives that they are hearing the same points raised by all interviewees. The team member requests a study team meeting to consider reducing the total number of interviews from 20, as previously planned, to 12.

Data saturation

A study team member “corners” a participant in a system development effort following a meeting and asks for the participant’s impressions on what transpired in the meeting.

Self-Test 15.2

Label each of the following interview scenarios, conducted as part of a qualitative study, as representing the fully structured, semi-structured or unstructured approach.

A study team member “corners” a participant in a system development project following a meeting and asks for that person’s impressions on what transpired in the meeting.

A study team member schedules time with a patient who is using an information resource to acquire specific information about the patient’s medical history.

Likely fully structured, though it could generate discussion, in which case it could veer towards semi-structured.

A study team member works with partners on the study team to develop a set of questions to be asked to all interviewees. Each question is to be followed up with the question: “Why do you think this is the case?”. At the end of the interview, subjects will be asked: “What else would you like to tell us to shed light on these matters?”

Semi-structured

An interview begins with the statement: “In general, what has been your experience using this EHR?” The remaining questions depend on how the interviewee answers this opening question.

Unstructured

A set of specific questions are read verbatim from an interview guide. No other questions are asked. The interviewees’ responses are recorded.

Fully structured

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Friedman, C.P., Wyatt, J.C., Ash, J.S. (2022). Qualitative Study Design and Data Collection. In: Evaluation Methods in Biomedical and Health Informatics. Health Informatics. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86453-8_15

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-86453-8_15

Published : 10 February 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-86452-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-86453-8

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

- Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

Published on 4 May 2022 by Pritha Bhandari .

Data collection is a systematic process of gathering observations or measurements. Whether you are performing research for business, governmental, or academic purposes, data collection allows you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem .

While methods and aims may differ between fields, the overall process of data collection remains largely the same. Before you begin collecting data, you need to consider:

- The aim of the research

- The type of data that you will collect

- The methods and procedures you will use to collect, store, and process the data

To collect high-quality data that is relevant to your purposes, follow these four steps.

Table of contents

Step 1: define the aim of your research, step 2: choose your data collection method, step 3: plan your data collection procedures, step 4: collect the data, frequently asked questions about data collection.

Before you start the process of data collection, you need to identify exactly what you want to achieve. You can start by writing a problem statement : what is the practical or scientific issue that you want to address, and why does it matter?

Next, formulate one or more research questions that precisely define what you want to find out. Depending on your research questions, you might need to collect quantitative or qualitative data :

- Quantitative data is expressed in numbers and graphs and is analysed through statistical methods .

- Qualitative data is expressed in words and analysed through interpretations and categorisations.

If your aim is to test a hypothesis , measure something precisely, or gain large-scale statistical insights, collect quantitative data. If your aim is to explore ideas, understand experiences, or gain detailed insights into a specific context, collect qualitative data.

If you have several aims, you can use a mixed methods approach that collects both types of data.

- Your first aim is to assess whether there are significant differences in perceptions of managers across different departments and office locations.

- Your second aim is to gather meaningful feedback from employees to explore new ideas for how managers can improve.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Based on the data you want to collect, decide which method is best suited for your research.

- Experimental research is primarily a quantitative method.

- Interviews , focus groups , and ethnographies are qualitative methods.

- Surveys , observations, archival research, and secondary data collection can be quantitative or qualitative methods.

Carefully consider what method you will use to gather data that helps you directly answer your research questions.

When you know which method(s) you are using, you need to plan exactly how you will implement them. What procedures will you follow to make accurate observations or measurements of the variables you are interested in?

For instance, if you’re conducting surveys or interviews, decide what form the questions will take; if you’re conducting an experiment, make decisions about your experimental design .

Operationalisation

Sometimes your variables can be measured directly: for example, you can collect data on the average age of employees simply by asking for dates of birth. However, often you’ll be interested in collecting data on more abstract concepts or variables that can’t be directly observed.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations. When planning how you will collect data, you need to translate the conceptual definition of what you want to study into the operational definition of what you will actually measure.

- You ask managers to rate their own leadership skills on 5-point scales assessing the ability to delegate, decisiveness, and dependability.

- You ask their direct employees to provide anonymous feedback on the managers regarding the same topics.

You may need to develop a sampling plan to obtain data systematically. This involves defining a population , the group you want to draw conclusions about, and a sample, the group you will actually collect data from.

Your sampling method will determine how you recruit participants or obtain measurements for your study. To decide on a sampling method you will need to consider factors like the required sample size, accessibility of the sample, and time frame of the data collection.

Standardising procedures

If multiple researchers are involved, write a detailed manual to standardise data collection procedures in your study.

This means laying out specific step-by-step instructions so that everyone in your research team collects data in a consistent way – for example, by conducting experiments under the same conditions and using objective criteria to record and categorise observations.

This helps ensure the reliability of your data, and you can also use it to replicate the study in the future.

Creating a data management plan

Before beginning data collection, you should also decide how you will organise and store your data.

- If you are collecting data from people, you will likely need to anonymise and safeguard the data to prevent leaks of sensitive information (e.g. names or identity numbers).

- If you are collecting data via interviews or pencil-and-paper formats, you will need to perform transcriptions or data entry in systematic ways to minimise distortion.

- You can prevent loss of data by having an organisation system that is routinely backed up.

Finally, you can implement your chosen methods to measure or observe the variables you are interested in.

The closed-ended questions ask participants to rate their manager’s leadership skills on scales from 1 to 5. The data produced is numerical and can be statistically analysed for averages and patterns.

To ensure that high-quality data is recorded in a systematic way, here are some best practices:

- Record all relevant information as and when you obtain data. For example, note down whether or how lab equipment is recalibrated during an experimental study.

- Double-check manual data entry for errors.

- If you collect quantitative data, you can assess the reliability and validity to get an indication of your data quality.

Data collection is the systematic process by which observations or measurements are gathered in research. It is used in many different contexts by academics, governments, businesses, and other organisations.

When conducting research, collecting original data has significant advantages:

- You can tailor data collection to your specific research aims (e.g., understanding the needs of your consumers or user testing your website).

- You can control and standardise the process for high reliability and validity (e.g., choosing appropriate measurements and sampling methods ).

However, there are also some drawbacks: data collection can be time-consuming, labour-intensive, and expensive. In some cases, it’s more efficient to use secondary data that has already been collected by someone else, but the data might be less reliable.

Quantitative research deals with numbers and statistics, while qualitative research deals with words and meanings.

Quantitative methods allow you to test a hypothesis by systematically collecting and analysing data, while qualitative methods allow you to explore ideas and experiences in depth.

Reliability and validity are both about how well a method measures something:

- Reliability refers to the consistency of a measure (whether the results can be reproduced under the same conditions).

- Validity refers to the accuracy of a measure (whether the results really do represent what they are supposed to measure).

If you are doing experimental research , you also have to consider the internal and external validity of your experiment.

In mixed methods research , you use both qualitative and quantitative data collection and analysis methods to answer your research question .

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

Bhandari, P. (2022, May 04). Data Collection Methods | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 27 May 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/data-collection-guide/

Is this article helpful?

Pritha Bhandari

Other students also liked, qualitative vs quantitative research | examples & methods, triangulation in research | guide, types, examples, what is a conceptual framework | tips & examples.

- Privacy Policy

Home » Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Data Collection – Methods Types and Examples

Table of Contents

Data Collection

Definition:

Data collection is the process of gathering and collecting information from various sources to analyze and make informed decisions based on the data collected. This can involve various methods, such as surveys, interviews, experiments, and observation.

In order for data collection to be effective, it is important to have a clear understanding of what data is needed and what the purpose of the data collection is. This can involve identifying the population or sample being studied, determining the variables to be measured, and selecting appropriate methods for collecting and recording data.

Types of Data Collection

Types of Data Collection are as follows:

Primary Data Collection

Primary data collection is the process of gathering original and firsthand information directly from the source or target population. This type of data collection involves collecting data that has not been previously gathered, recorded, or published. Primary data can be collected through various methods such as surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, and focus groups. The data collected is usually specific to the research question or objective and can provide valuable insights that cannot be obtained from secondary data sources. Primary data collection is often used in market research, social research, and scientific research.

Secondary Data Collection

Secondary data collection is the process of gathering information from existing sources that have already been collected and analyzed by someone else, rather than conducting new research to collect primary data. Secondary data can be collected from various sources, such as published reports, books, journals, newspapers, websites, government publications, and other documents.

Qualitative Data Collection

Qualitative data collection is used to gather non-numerical data such as opinions, experiences, perceptions, and feelings, through techniques such as interviews, focus groups, observations, and document analysis. It seeks to understand the deeper meaning and context of a phenomenon or situation and is often used in social sciences, psychology, and humanities. Qualitative data collection methods allow for a more in-depth and holistic exploration of research questions and can provide rich and nuanced insights into human behavior and experiences.

Quantitative Data Collection

Quantitative data collection is a used to gather numerical data that can be analyzed using statistical methods. This data is typically collected through surveys, experiments, and other structured data collection methods. Quantitative data collection seeks to quantify and measure variables, such as behaviors, attitudes, and opinions, in a systematic and objective way. This data is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and establish correlations between variables. Quantitative data collection methods allow for precise measurement and generalization of findings to a larger population. It is commonly used in fields such as economics, psychology, and natural sciences.

Data Collection Methods

Data Collection Methods are as follows:

Surveys involve asking questions to a sample of individuals or organizations to collect data. Surveys can be conducted in person, over the phone, or online.

Interviews involve a one-on-one conversation between the interviewer and the respondent. Interviews can be structured or unstructured and can be conducted in person or over the phone.

Focus Groups

Focus groups are group discussions that are moderated by a facilitator. Focus groups are used to collect qualitative data on a specific topic.

Observation

Observation involves watching and recording the behavior of people, objects, or events in their natural setting. Observation can be done overtly or covertly, depending on the research question.

Experiments

Experiments involve manipulating one or more variables and observing the effect on another variable. Experiments are commonly used in scientific research.

Case Studies

Case studies involve in-depth analysis of a single individual, organization, or event. Case studies are used to gain detailed information about a specific phenomenon.

Secondary Data Analysis

Secondary data analysis involves using existing data that was collected for another purpose. Secondary data can come from various sources, such as government agencies, academic institutions, or private companies.

How to Collect Data

The following are some steps to consider when collecting data:

- Define the objective : Before you start collecting data, you need to define the objective of the study. This will help you determine what data you need to collect and how to collect it.

- Identify the data sources : Identify the sources of data that will help you achieve your objective. These sources can be primary sources, such as surveys, interviews, and observations, or secondary sources, such as books, articles, and databases.

- Determine the data collection method : Once you have identified the data sources, you need to determine the data collection method. This could be through online surveys, phone interviews, or face-to-face meetings.

- Develop a data collection plan : Develop a plan that outlines the steps you will take to collect the data. This plan should include the timeline, the tools and equipment needed, and the personnel involved.

- Test the data collection process: Before you start collecting data, test the data collection process to ensure that it is effective and efficient.

- Collect the data: Collect the data according to the plan you developed in step 4. Make sure you record the data accurately and consistently.

- Analyze the data: Once you have collected the data, analyze it to draw conclusions and make recommendations.

- Report the findings: Report the findings of your data analysis to the relevant stakeholders. This could be in the form of a report, a presentation, or a publication.

- Monitor and evaluate the data collection process: After the data collection process is complete, monitor and evaluate the process to identify areas for improvement in future data collection efforts.

- Ensure data quality: Ensure that the collected data is of high quality and free from errors. This can be achieved by validating the data for accuracy, completeness, and consistency.

- Maintain data security: Ensure that the collected data is secure and protected from unauthorized access or disclosure. This can be achieved by implementing data security protocols and using secure storage and transmission methods.

- Follow ethical considerations: Follow ethical considerations when collecting data, such as obtaining informed consent from participants, protecting their privacy and confidentiality, and ensuring that the research does not cause harm to participants.

- Use appropriate data analysis methods : Use appropriate data analysis methods based on the type of data collected and the research objectives. This could include statistical analysis, qualitative analysis, or a combination of both.

- Record and store data properly: Record and store the collected data properly, in a structured and organized format. This will make it easier to retrieve and use the data in future research or analysis.

- Collaborate with other stakeholders : Collaborate with other stakeholders, such as colleagues, experts, or community members, to ensure that the data collected is relevant and useful for the intended purpose.

Applications of Data Collection

Data collection methods are widely used in different fields, including social sciences, healthcare, business, education, and more. Here are some examples of how data collection methods are used in different fields:

- Social sciences : Social scientists often use surveys, questionnaires, and interviews to collect data from individuals or groups. They may also use observation to collect data on social behaviors and interactions. This data is often used to study topics such as human behavior, attitudes, and beliefs.

- Healthcare : Data collection methods are used in healthcare to monitor patient health and track treatment outcomes. Electronic health records and medical charts are commonly used to collect data on patients’ medical history, diagnoses, and treatments. Researchers may also use clinical trials and surveys to collect data on the effectiveness of different treatments.

- Business : Businesses use data collection methods to gather information on consumer behavior, market trends, and competitor activity. They may collect data through customer surveys, sales reports, and market research studies. This data is used to inform business decisions, develop marketing strategies, and improve products and services.

- Education : In education, data collection methods are used to assess student performance and measure the effectiveness of teaching methods. Standardized tests, quizzes, and exams are commonly used to collect data on student learning outcomes. Teachers may also use classroom observation and student feedback to gather data on teaching effectiveness.

- Agriculture : Farmers use data collection methods to monitor crop growth and health. Sensors and remote sensing technology can be used to collect data on soil moisture, temperature, and nutrient levels. This data is used to optimize crop yields and minimize waste.

- Environmental sciences : Environmental scientists use data collection methods to monitor air and water quality, track climate patterns, and measure the impact of human activity on the environment. They may use sensors, satellite imagery, and laboratory analysis to collect data on environmental factors.

- Transportation : Transportation companies use data collection methods to track vehicle performance, optimize routes, and improve safety. GPS systems, on-board sensors, and other tracking technologies are used to collect data on vehicle speed, fuel consumption, and driver behavior.

Examples of Data Collection

Examples of Data Collection are as follows:

- Traffic Monitoring: Cities collect real-time data on traffic patterns and congestion through sensors on roads and cameras at intersections. This information can be used to optimize traffic flow and improve safety.

- Social Media Monitoring : Companies can collect real-time data on social media platforms such as Twitter and Facebook to monitor their brand reputation, track customer sentiment, and respond to customer inquiries and complaints in real-time.

- Weather Monitoring: Weather agencies collect real-time data on temperature, humidity, air pressure, and precipitation through weather stations and satellites. This information is used to provide accurate weather forecasts and warnings.

- Stock Market Monitoring : Financial institutions collect real-time data on stock prices, trading volumes, and other market indicators to make informed investment decisions and respond to market fluctuations in real-time.

- Health Monitoring : Medical devices such as wearable fitness trackers and smartwatches can collect real-time data on a person’s heart rate, blood pressure, and other vital signs. This information can be used to monitor health conditions and detect early warning signs of health issues.

Purpose of Data Collection

The purpose of data collection can vary depending on the context and goals of the study, but generally, it serves to:

- Provide information: Data collection provides information about a particular phenomenon or behavior that can be used to better understand it.

- Measure progress : Data collection can be used to measure the effectiveness of interventions or programs designed to address a particular issue or problem.

- Support decision-making : Data collection provides decision-makers with evidence-based information that can be used to inform policies, strategies, and actions.

- Identify trends : Data collection can help identify trends and patterns over time that may indicate changes in behaviors or outcomes.

- Monitor and evaluate : Data collection can be used to monitor and evaluate the implementation and impact of policies, programs, and initiatives.

When to use Data Collection

Data collection is used when there is a need to gather information or data on a specific topic or phenomenon. It is typically used in research, evaluation, and monitoring and is important for making informed decisions and improving outcomes.

Data collection is particularly useful in the following scenarios:

- Research : When conducting research, data collection is used to gather information on variables of interest to answer research questions and test hypotheses.

- Evaluation : Data collection is used in program evaluation to assess the effectiveness of programs or interventions, and to identify areas for improvement.

- Monitoring : Data collection is used in monitoring to track progress towards achieving goals or targets, and to identify any areas that require attention.

- Decision-making: Data collection is used to provide decision-makers with information that can be used to inform policies, strategies, and actions.

- Quality improvement : Data collection is used in quality improvement efforts to identify areas where improvements can be made and to measure progress towards achieving goals.

Characteristics of Data Collection

Data collection can be characterized by several important characteristics that help to ensure the quality and accuracy of the data gathered. These characteristics include:

- Validity : Validity refers to the accuracy and relevance of the data collected in relation to the research question or objective.

- Reliability : Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of the data collection process, ensuring that the results obtained are consistent over time and across different contexts.

- Objectivity : Objectivity refers to the impartiality of the data collection process, ensuring that the data collected is not influenced by the biases or personal opinions of the data collector.

- Precision : Precision refers to the degree of accuracy and detail in the data collected, ensuring that the data is specific and accurate enough to answer the research question or objective.

- Timeliness : Timeliness refers to the efficiency and speed with which the data is collected, ensuring that the data is collected in a timely manner to meet the needs of the research or evaluation.

- Ethical considerations : Ethical considerations refer to the ethical principles that must be followed when collecting data, such as ensuring confidentiality and obtaining informed consent from participants.

Advantages of Data Collection

There are several advantages of data collection that make it an important process in research, evaluation, and monitoring. These advantages include:

- Better decision-making : Data collection provides decision-makers with evidence-based information that can be used to inform policies, strategies, and actions, leading to better decision-making.

- Improved understanding: Data collection helps to improve our understanding of a particular phenomenon or behavior by providing empirical evidence that can be analyzed and interpreted.

- Evaluation of interventions: Data collection is essential in evaluating the effectiveness of interventions or programs designed to address a particular issue or problem.

- Identifying trends and patterns: Data collection can help identify trends and patterns over time that may indicate changes in behaviors or outcomes.

- Increased accountability: Data collection increases accountability by providing evidence that can be used to monitor and evaluate the implementation and impact of policies, programs, and initiatives.

- Validation of theories: Data collection can be used to test hypotheses and validate theories, leading to a better understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

- Improved quality: Data collection is used in quality improvement efforts to identify areas where improvements can be made and to measure progress towards achieving goals.

Limitations of Data Collection

While data collection has several advantages, it also has some limitations that must be considered. These limitations include:

- Bias : Data collection can be influenced by the biases and personal opinions of the data collector, which can lead to inaccurate or misleading results.

- Sampling bias : Data collection may not be representative of the entire population, resulting in sampling bias and inaccurate results.

- Cost : Data collection can be expensive and time-consuming, particularly for large-scale studies.

- Limited scope: Data collection is limited to the variables being measured, which may not capture the entire picture or context of the phenomenon being studied.

- Ethical considerations : Data collection must follow ethical principles to protect the rights and confidentiality of the participants, which can limit the type of data that can be collected.

- Data quality issues: Data collection may result in data quality issues such as missing or incomplete data, measurement errors, and inconsistencies.

- Limited generalizability : Data collection may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations, limiting the generalizability of the findings.

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Delimitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Research Process – Steps, Examples and Tips

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Institutional Review Board – Application Sample...

Evaluating Research – Process, Examples and...

Research Questions – Types, Examples and Writing...

A Guide to Data Collection: Methods, Process, and Tools

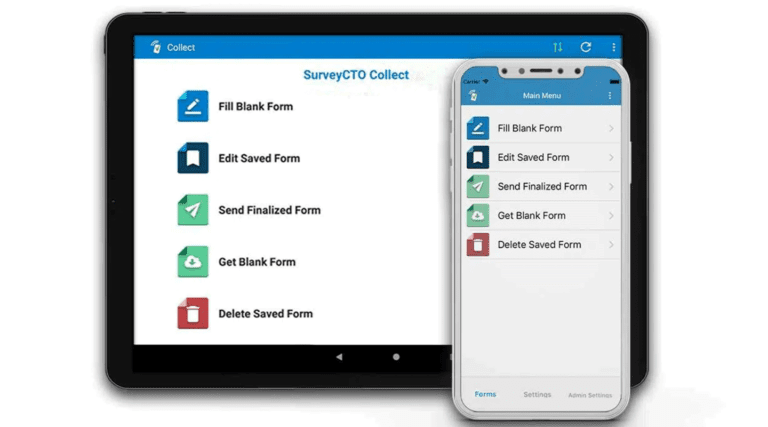

Whether your field is development economics, international development, the nonprofit sector, or myriad other industries, effective data collection is essential. It informs decision-making and increases your organization’s impact. However, the process of data collection can be complex and challenging. If you’re in the beginning stages of creating a data collection process, this guide is for you. It outlines tested methods, efficient procedures, and effective tools to help you improve your data collection activities and outcomes. At SurveyCTO, we’ve used our years of experience and expertise to build a robust, secure, and scalable mobile data collection platform. It’s trusted by respected institutions like The World Bank, J-PAL, Oxfam, and the Gates Foundation, and it’s changed the way many organizations collect and use data. With this guide, we want to share what we know and help you get ready to take the first step in your data collection journey.

Main takeaways from this guide