How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

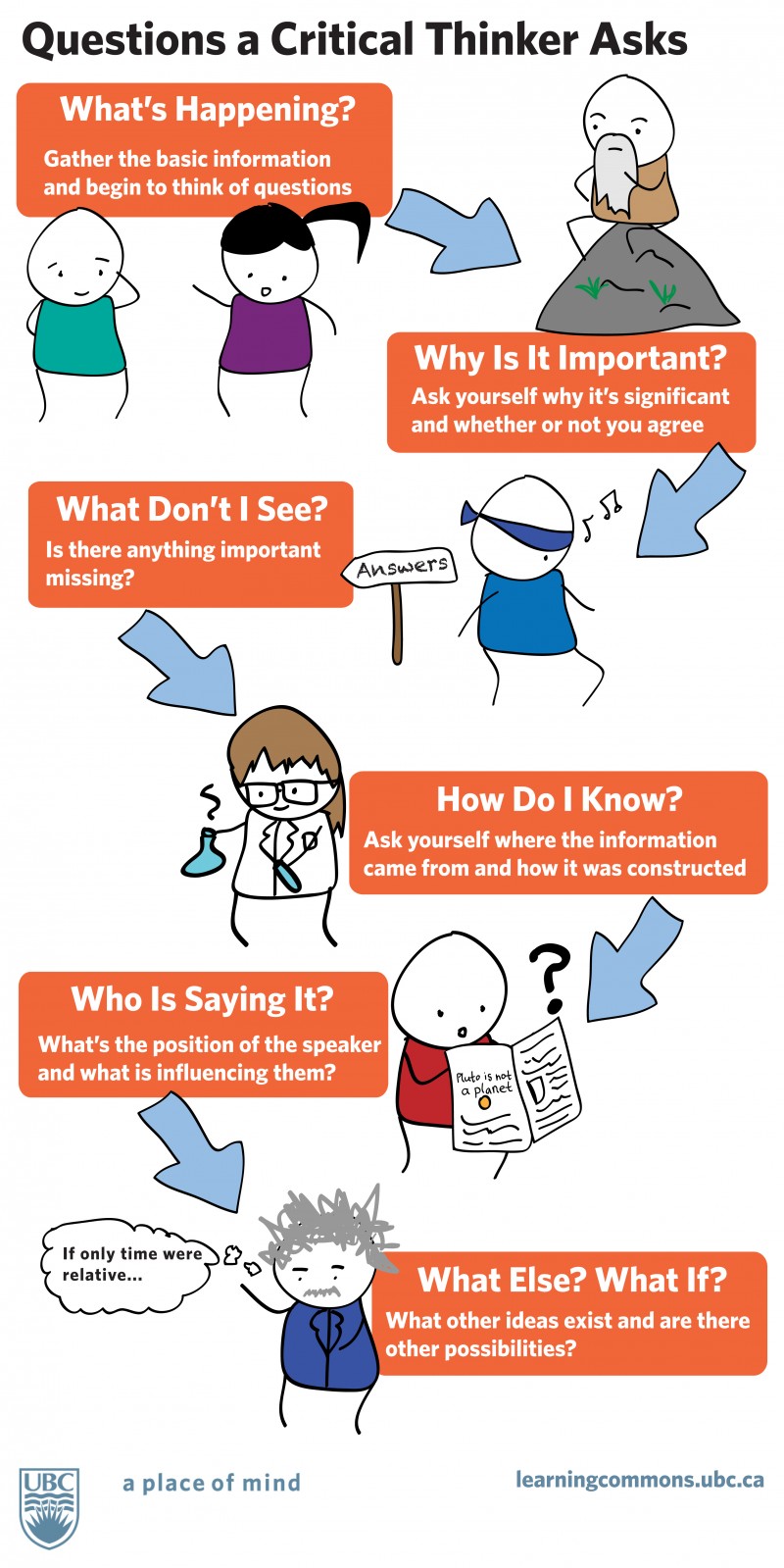

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

Snyder's hope theory.

Cultivating Aspiration in Your Life

Mindfulness in the Workplace

Focusing the Mind by Staying Present

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Gain essential management and leadership skills

Busy schedule? No problem. Learn anytime, anywhere.

Subscribe to unlimited access to meticulously researched, evidence-based resources.

Join today and save on an annual membership!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Latest Updates

Better Public Speaking

How to Build Confidence in Others

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

How to create psychological safety at work.

Speaking up without fear

How to Guides

Pain Points Podcast - Presentations Pt 1

How do you get better at presenting?

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

The science of a good night's sleep infographic.

Infographic Transcript

Infographic

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Work Life is Atlassian’s flagship publication dedicated to unleashing the potential of every team through real-life advice, inspiring stories, and thoughtful perspectives from leaders around the world.

Contributing Writer

Work Futurist

Senior Quantitative Researcher, People Insights

Principal Writer

How to build critical thinking skills for better decision-making

It’s simple in theory, but tougher in practice – here are five tips to get you started.

Get stories like this in your inbox

Have you heard the riddle about two coins that equal thirty cents, but one of them is not a nickel? What about the one where a surgeon says they can’t operate on their own son?

Those brain teasers tap into your critical thinking skills. But your ability to think critically isn’t just helpful for solving those random puzzles – it plays a big role in your career.

An impressive 81% of employers say critical thinking carries a lot of weight when they’re evaluating job candidates. It ranks as the top competency companies consider when hiring recent graduates (even ahead of communication ). Plus, once you’re hired, several studies show that critical thinking skills are highly correlated with better job performance.

So what exactly are critical thinking skills? And even more importantly, how do you build and improve them?

What is critical thinking?

Critical thinking is the ability to evaluate facts and information, remain objective, and make a sound decision about how to move forward.

Does that sound like how you approach every decision or problem? Not so fast. Critical thinking seems simple in theory but is much tougher in practice, which helps explain why 65% of employers say their organization has a need for more critical thinking.

In reality, critical thinking doesn’t come naturally to a lot of us. In order to do it well, you need to:

- Remain open-minded and inquisitive, rather than relying on assumptions or jumping to conclusions

- Ask questions and dig deep, rather than accepting information at face value

- Keep your own biases and perceptions in check to stay as objective as possible

- Rely on your emotional intelligence to fill in the blanks and gain a more well-rounded understanding of a situation

So, critical thinking isn’t just being intelligent or analytical. In many ways, it requires you to step outside of yourself, let go of your own preconceived notions, and approach a problem or situation with curiosity and fairness.

It’s a challenge, but it’s well worth it. Critical thinking skills will help you connect ideas, make reasonable decisions, and solve complex problems.

7 critical thinking skills to help you dig deeper

Critical thinking is often labeled as a skill itself (you’ll see it bulleted as a desired trait in a variety of job descriptions). But it’s better to think of critical thinking less as a distinct skill and more as a collection or category of skills.

To think critically, you’ll need to tap into a bunch of your other soft skills. Here are seven of the most important.

Open-mindedness

It’s important to kick off the critical thinking process with the idea that anything is possible. The more you’re able to set aside your own suspicions, beliefs, and agenda, the better prepared you are to approach the situation with the level of inquisitiveness you need.

That means not closing yourself off to any possibilities and allowing yourself the space to pull on every thread – yes, even the ones that seem totally implausible.

As Christopher Dwyer, Ph.D. writes in a piece for Psychology Today , “Even if an idea appears foolish, sometimes its consideration can lead to an intelligent, critically considered conclusion.” He goes on to compare the critical thinking process to brainstorming . Sometimes the “bad” ideas are what lay the foundation for the good ones.

Open-mindedness is challenging because it requires more effort and mental bandwidth than sticking with your own perceptions. Approaching problems or situations with true impartiality often means:

- Practicing self-regulation : Giving yourself a pause between when you feel something and when you actually react or take action.

- Challenging your own biases: Acknowledging your biases and seeking feedback are two powerful ways to get a broader understanding.

Critical thinking example

In a team meeting, your boss mentioned that your company newsletter signups have been decreasing and she wants to figure out why.

At first, you feel offended and defensive – it feels like she’s blaming you for the dip in subscribers. You recognize and rationalize that emotion before thinking about potential causes. You have a hunch about what’s happening, but you will explore all possibilities and contributions from your team members.

Observation

Observation is, of course, your ability to notice and process the details all around you (even the subtle or seemingly inconsequential ones). Critical thinking demands that you’re flexible and willing to go beyond surface-level information, and solid observation skills help you do that.

Your observations help you pick up on clues from a variety of sources and experiences, all of which help you draw a final conclusion. After all, sometimes it’s the most minuscule realization that leads you to the strongest conclusion.

Over the next week or so, you keep a close eye on your company’s website and newsletter analytics to see if numbers are in fact declining or if your boss’s concerns were just a fluke.

Critical thinking hinges on objectivity. And, to be objective, you need to base your judgments on the facts – which you collect through research. You’ll lean on your research skills to gather as much information as possible that’s relevant to your problem or situation.

Keep in mind that this isn’t just about the quantity of information – quality matters too. You want to find data and details from a variety of trusted sources to drill past the surface and build a deeper understanding of what’s happening.

You dig into your email and website analytics to identify trends in bounce rates, time on page, conversions, and more. You also review recent newsletters and email promotions to understand what customers have received, look through current customer feedback, and connect with your customer support team to learn what they’re hearing in their conversations with customers.

The critical thinking process is sort of like a treasure hunt – you’ll find some nuggets that are fundamental for your final conclusion and some that might be interesting but aren’t pertinent to the problem at hand.

That’s why you need analytical skills. They’re what help you separate the wheat from the chaff, prioritize information, identify trends or themes, and draw conclusions based on the most relevant and influential facts.

It’s easy to confuse analytical thinking with critical thinking itself, and it’s true there is a lot of overlap between the two. But analytical thinking is just a piece of critical thinking. It focuses strictly on the facts and data, while critical thinking incorporates other factors like emotions, opinions, and experiences.

As you analyze your research, you notice that one specific webpage has contributed to a significant decline in newsletter signups. While all of the other sources have stayed fairly steady with regard to conversions, that one has sharply decreased.

You decide to move on from your other hypotheses about newsletter quality and dig deeper into the analytics.

One of the traps of critical thinking is that it’s easy to feel like you’re never done. There’s always more information you could collect and more rabbit holes you could fall down.

But at some point, you need to accept that you’ve done your due diligence and make a decision about how to move forward. That’s where inference comes in. It’s your ability to look at the evidence and facts available to you and draw an informed conclusion based on those.

When you’re so focused on staying objective and pursuing all possibilities, inference can feel like the antithesis of critical thinking. But ultimately, it’s your inference skills that allow you to move out of the thinking process and onto the action steps.

You dig deeper into the analytics for the page that hasn’t been converting and notice that the sharp drop-off happened around the same time you switched email providers.

After looking more into the backend, you realize that the signup form on that page isn’t correctly connected to your newsletter platform. It seems like anybody who has signed up on that page hasn’t been fed to your email list.

Communication

3 ways to improve your communication skills at work

If and when you identify a solution or answer, you can’t keep it close to the vest. You’ll need to use your communication skills to share your findings with the relevant stakeholders – like your boss, team members, or anybody who needs to be involved in the next steps.

Your analysis skills will come in handy here too, as they’ll help you determine what information other people need to know so you can avoid bogging them down with unnecessary details.

In your next team meeting, you pull up the analytics and show your team the sharp drop-off as well as the missing connection between that page and your email platform. You ask the web team to reinstall and double-check that connection and you also ask a member of the marketing team to draft an apology email to the subscribers who were missed.

Problem-solving

Critical thinking and problem-solving are two more terms that are frequently confused. After all, when you think critically, you’re often doing so with the objective of solving a problem.

The best way to understand how problem-solving and critical thinking differ is to think of problem-solving as much more narrow. You’re focused on finding a solution.

In contrast, you can use critical thinking for a variety of use cases beyond solving a problem – like answering questions or identifying opportunities for improvement. Even so, within the critical thinking process, you’ll flex your problem-solving skills when it comes time to take action.

Once the fix is implemented, you monitor the analytics to see if subscribers continue to increase. If not (or if they increase at a slower rate than you anticipated), you’ll roll out some other tests like changing the CTA language or the placement of the subscribe form on the page.

5 ways to improve your critical thinking skills

Beyond the buzzwords: Why interpersonal skills matter at work

Think critically about critical thinking and you’ll quickly realize that it’s not as instinctive as you’d like it to be. Fortunately, your critical thinking skills are learned competencies and not inherent gifts – and that means you can improve them. Here’s how:

- Practice active listening: Active listening helps you process and understand what other people share. That’s crucial as you aim to be open-minded and inquisitive.

- Ask open-ended questions: If your critical thinking process involves collecting feedback and opinions from others, ask open-ended questions (meaning, questions that can’t be answered with “yes” or “no”). Doing so will give you more valuable information and also prevent your own biases from influencing people’s input.

- Scrutinize your sources: Figuring out what to trust and prioritize is crucial for critical thinking. Boosting your media literacy and asking more questions will help you be more discerning about what to factor in. It’s hard to strike a balance between skepticism and open-mindedness, but approaching information with questions (rather than unquestioning trust) will help you draw better conclusions.

- Play a game: Remember those riddles we mentioned at the beginning? As trivial as they might seem, games and exercises like those can help you boost your critical thinking skills. There are plenty of critical thinking exercises you can do individually or as a team .

- Give yourself time: Research shows that rushed decisions are often regrettable ones. That’s likely because critical thinking takes time – you can’t do it under the wire. So, for big decisions or hairy problems, give yourself enough time and breathing room to work through the process. It’s hard enough to think critically without a countdown ticking in your brain.

Critical thinking really is critical

The ability to think critically is important, but it doesn’t come naturally to most of us. It’s just easier to stick with biases, assumptions, and surface-level information.

But that route often leads you to rash judgments, shaky conclusions, and disappointing decisions. So here’s a conclusion we can draw without any more noodling: Even if it is more demanding on your mental resources, critical thinking is well worth the effort.

Advice, stories, and expertise about work life today.

Academic Skills Center: Critical Reading

- Academic Skills Center

- Accounting and Finance

- College Math

- Self-Paced Modules

- About Us Home

- Administrative Staff

- Social Change

- Peer Mentors Home

- Peer Live Events

- Meet the Peer Mentors

- Microsoft Office

- Microsoft Word

- Microsoft PowerPoint

- Statistics Skills in Microsoft Excel

- Capstone Formatting

- MS Peer Tutoring

- Course-Level Statistics

- Statistics Tutoring

- Strengthen Your Statistics Skills

- HUMN 8304 Resources

- Statistics Resources

- SPSS and NVivo

- Success Strategies Home

- Time Management

- School-Life Balance

- Learning Strategies

- Critical Reading

- Communication

- Doctoral Capstone and Residency

- Classroom Skills

- Beyond the Classroom

- Mindset and Wellness

- Self-Care and Wellness

- Grit and Resilience

- SMART Goals

- Diversity and Inclusion

- Savvy Student Blog

- Redirected_Residency

- Redirected_Undergraduate Peer Mentors

- Redirected_Doctoral Peer Mentors

- Redirected_Technology Skills

- Course Resources

- Reading Skills (old)

- Previous Page: Learning Strategies

- Next Page: Communication

Reading Self-Paced Modules

Reading Textbooks Reading Articles

Reading Skills Part 1: Set Yourself Up for Success

"While - like many of us - I enjoy reading what I want to read, I still struggle to get through a dense research article or textbook chapter. I have noticed, however, that if I take steps to prepare, I am much more likely to persist through a challenging reading. "

Reading Skills Part 2: Alternatives to Highlighting

"It starts with the best of intentions: trusty highlighter in hand or (for the tech-savvy crowd) highlighting tool hovering on-screen, you work your way through an assigned reading, marking only the most important information—or so you think."

Reading Skills Part 3: Read to Remember

"It’s happened to the best of us: on Monday evening, you congratulate yourself on making it though an especially challenging reading. What a productive start to the week!"

Reading a Research Article Assigned as Coursework

"Reading skills are vital to your success at Walden. The kind of reading you do during your degree program will vary, but most of it will involve reading journal articles based on primary research."

Critical Reading for Evaluation

"Whereas analysis involves noticing, evaluation requires the reader to make a judgment about the text’s strengths and weaknesses. Many students are not confident in their ability to assess what they are reading."

Critical Reading for Analysis and Comparison

"Critical reading generally refers to reading in a scholarly context, with an eye toward identifying a text or author’s viewpoints, arguments, evidence, potential biases, and conclusions."

Pre-Reading Strategies

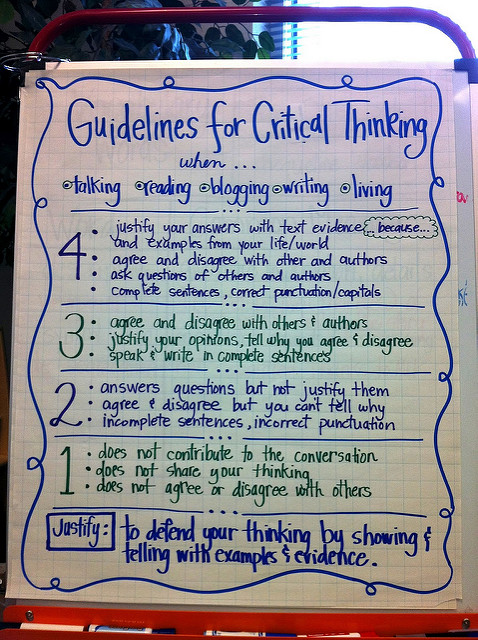

Triple entry notebook, critical thinking.

Use this checklist to practice critical thinking while reading an article, watching an advertisement, or making an important purchase or voting decision.

Critical Reading Checklist (Word) Critical Reading Checklist (PDF) Critical Thinking Bookmark (PDF)

Walden's Online Bookstore

Go to Walden's Online Bookstore

Hillary Wentworth on SKIL Grad Writing Courses, Critical Reading, & Online Etiquette

All the Skills You Need to Succeed.

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

Module 1: Success Skills

Critical thinking, introduction, learning objectives.

- define critical thinking

- identify the role that logic plays in critical thinking

- apply critical thinking skills to problem-solving scenarios

- apply critical thinking skills to evaluation of information

Consider these thoughts about the critical thinking process, and how it applies not just to our school lives but also our personal and professional lives.

“Thinking Critically and Creatively”

Critical thinking skills are perhaps the most fundamental skills involved in making judgments and solving problems. You use them every day, and you can continue improving them.

The ability to think critically about a matter—to analyze a question, situation, or problem down to its most basic parts—is what helps us evaluate the accuracy and truthfulness of statements, claims, and information we read and hear. It is the sharp knife that, when honed, separates fact from fiction, honesty from lies, and the accurate from the misleading. We all use this skill to one degree or another almost every day. For example, we use critical thinking every day as we consider the latest consumer products and why one particular product is the best among its peers. Is it a quality product because a celebrity endorses it? Because a lot of other people may have used it? Because it is made by one company versus another? Or perhaps because it is made in one country or another? These are questions representative of critical thinking.

The academic setting demands more of us in terms of critical thinking than everyday life. It demands that we evaluate information and analyze myriad issues. It is the environment where our critical thinking skills can be the difference between success and failure. In this environment we must consider information in an analytical, critical manner. We must ask questions—What is the source of this information? Is this source an expert one and what makes it so? Are there multiple perspectives to consider on an issue? Do multiple sources agree or disagree on an issue? Does quality research substantiate information or opinion? Do I have any personal biases that may affect my consideration of this information?

It is only through purposeful, frequent, intentional questioning such as this that we can sharpen our critical thinking skills and improve as students, learners and researchers.

—Dr. Andrew Robert Baker, Foundations of Academic Success: Words of Wisdom

Defining Critical Thinking

Thinking comes naturally. You don’t have to make it happen—it just does. But you can make it happen in different ways. For example, you can think positively or negatively. You can think with “heart” and you can think with rational judgment. You can also think strategically and analytically, and mathematically and scientifically. These are a few of multiple ways in which the mind can process thought.

What are some forms of thinking you use? When do you use them, and why?

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking. Critical thinking is important because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It’s not restricted to a particular subject area.

Critical thinking is clear, reasonable, reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do. It means asking probing questions like, “How do we know?” or “Is this true in every case or just in this instance?” It involves being skeptical and challenging assumptions, rather than simply memorizing facts or blindly accepting what you hear or read.

Imagine, for example, that you’re reading a history textbook. You wonder who wrote it and why, because you detect certain assumptions in the writing. You find that the author has a limited scope of research focused only on a particular group within a population. In this case, your critical thinking reveals that there are “other sides to the story.”

Who are critical thinkers, and what characteristics do they have in common? Critical thinkers are usually curious and reflective people. They like to explore and probe new areas and seek knowledge, clarification, and new solutions. They ask pertinent questions, evaluate statements and arguments, and they distinguish between facts and opinion. They are also willing to examine their own beliefs, possessing a manner of humility that allows them to admit lack of knowledge or understanding when needed. They are open to changing their mind. Perhaps most of all, they actively enjoy learning, and seeking new knowledge is a lifelong pursuit.

This may well be you!

No matter where you are on the road to being a critical thinker, you can always more fully develop your skills. Doing so will help you develop more balanced arguments, express yourself clearly, read critically, and absorb important information efficiently. Critical thinking skills will help you in any profession or any circumstance of life, from science to art to business to teaching.

Critical Thinking in Action

The following video, from Lawrence Bland, presents the major concepts and benefits of critical thinking.

Critical Thinking and Logic

Critical thinking is fundamentally a process of questioning information and data. You may question the information you read in a textbook, or you may question what a politician or a professor or a classmate says. You can also question a commonly-held belief or a new idea. With critical thinking, anything and everything is subject to question and examination.

Logic’s Relationship to Critical Thinking

The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike , referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate ideas or claims people make, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world. [1]

Questions of Logic in Critical Thinking

Let’s use a simple example of applying logic to a critical-thinking situation. In this hypothetical scenario, a man has a PhD in political science, and he works as a professor at a local college. His wife works at the college, too. They have three young children in the local school system, and their family is well known in the community.

The man is now running for political office. Are his credentials and experience sufficient for entering public office? Will he be effective in the political office? Some voters might believe that his personal life and current job, on the surface, suggest he will do well in the position, and they will vote for him.

In truth, the characteristics described don’t guarantee that the man will do a good job. The information is somewhat irrelevant. What else might you want to know? How about whether the man had already held a political office and done a good job? In this case, we want to ask, How much information is adequate in order to make a decision based on logic instead of assumptions?

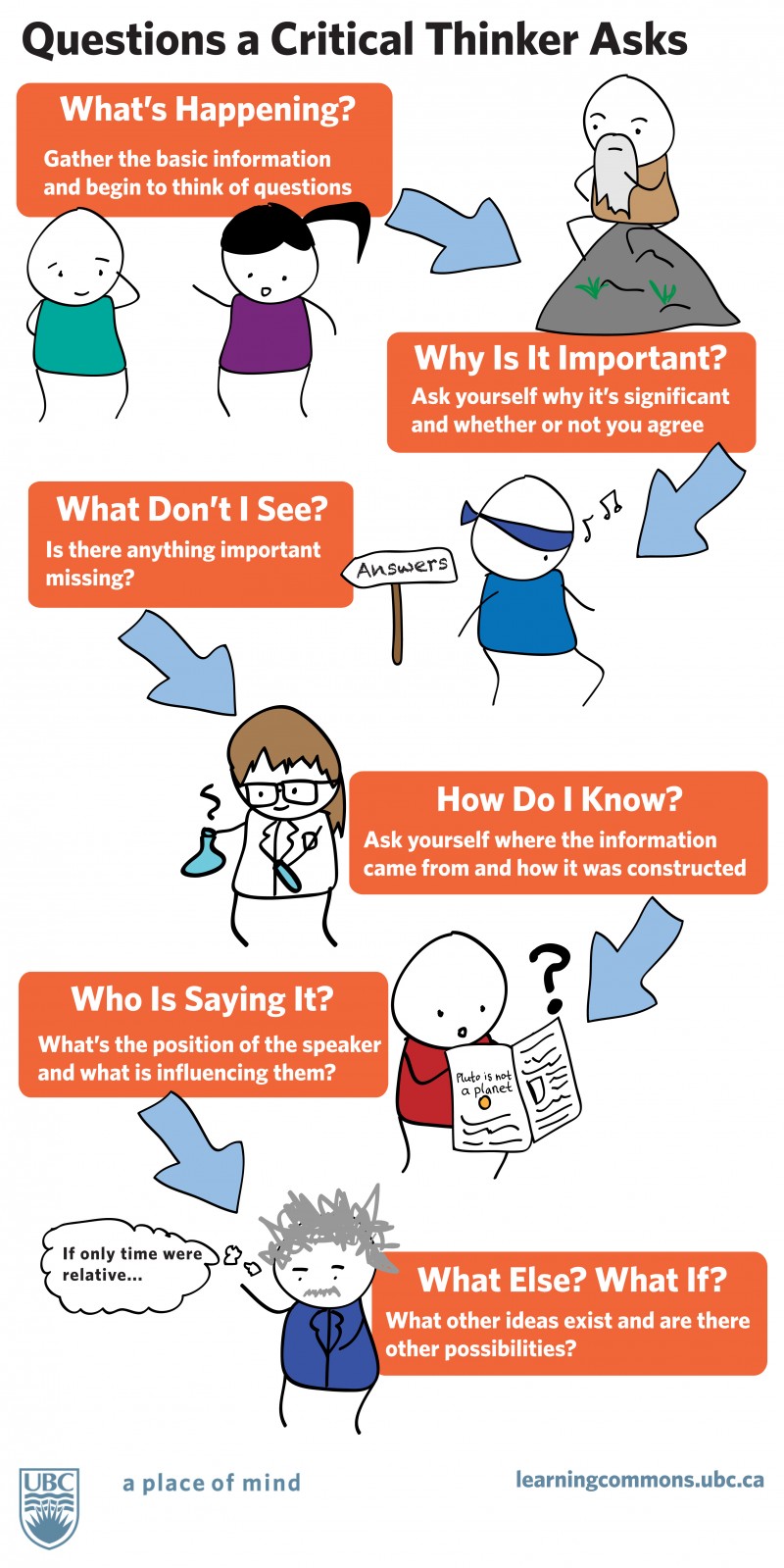

The following questions, presented in Figure 1, below, are ones you may apply to formulating a logical, reasoned perspective in the above scenario or any other situation:

- What’s happening? Gather the basic information and begin to think of questions.

- Why is it important? Ask yourself why it’s significant and whether or not you agree.

- What don’t I see? Is there anything important missing?

- How do I know? Ask yourself where the information came from and how it was constructed.

- Who is saying it? What’s the position of the speaker and what is influencing them?

- What else? What if? What other ideas exist and are there other possibilities?

Problem-Solving With Critical Thinking

For most people, a typical day is filled with critical thinking and problem-solving challenges. In fact, critical thinking and problem-solving go hand-in-hand. They both refer to using knowledge, facts, and data to solve problems effectively. But with problem-solving, you are specifically identifying, selecting, and defending your solution. Below are some examples of using critical thinking to problem-solve:

- Your roommate was upset and said some unkind words to you, which put a crimp in your relationship. You try to see through the angry behaviors to determine how you might best support your roommate and help bring your relationship back to a comfortable spot.

- Your final art class project challenges you to conceptualize form in new ways. On the last day of class when students present their projects, you describe the techniques you used to fulfill the assignment. You explain why and how you selected that approach.

- Your math teacher sees that the class is not quite grasping a concept. She uses clever questioning to dispel anxiety and guide you to new understanding of the concept.

- You have a job interview for a position that you feel you are only partially qualified for, although you really want the job and you are excited about the prospects. You analyze how you will explain your skills and experiences in a way to show that you are a good match for the prospective employer.

- You are doing well in college, and most of your college and living expenses are covered. But there are some gaps between what you want and what you feel you can afford. You analyze your income, savings, and budget to better calculate what you will need to stay in college and maintain your desired level of spending.

Problem-Solving Action Checklist

Problem-solving can be an efficient and rewarding process, especially if you are organized and mindful of critical steps and strategies. Remember, too, to assume the attributes of a good critical thinker. If you are curious, reflective, knowledge-seeking, open to change, probing, organized, and ethical, your challenge or problem will be less of a hurdle, and you’ll be in a good position to find intelligent solutions.

Evaluating Information With Critical Thinking

Evaluating information can be one of the most complex tasks you will be faced with in college. But if you utilize the following four strategies, you will be well on your way to success:

- Read for understanding by using text coding

- Examine arguments

- Clarify thinking

1. Read for Understanding Using Text Coding

When you read and take notes, use the text coding strategy . Text coding is a way of tracking your thinking while reading. It entails marking the text and recording what you are thinking either in the margins or perhaps on Post-it notes. As you make connections and ask questions in response to what you read, you monitor your comprehension and enhance your long-term understanding of the material.

With text coding, mark important arguments and key facts. Indicate where you agree and disagree or have further questions. You don’t necessarily need to read every word, but make sure you understand the concepts or the intentions behind what is written. Feel free to develop your own shorthand style when reading or taking notes. The following are a few options to consider using while coding text.

See more text coding from PBWorks and Collaborative for Teaching and Learning .

2. Examine Arguments

When you examine arguments or claims that an author, speaker, or other source is making, your goal is to identify and examine the hard facts. You can use the spectrum of authority strategy for this purpose. The spectrum of authority strategy assists you in identifying the “hot” end of an argument—feelings, beliefs, cultural influences, and societal influences—and the “cold” end of an argument—scientific influences. The following video explains this strategy.

3. Clarify Thinking

When you use critical thinking to evaluate information, you need to clarify your thinking to yourself and likely to others. Doing this well is mainly a process of asking and answering probing questions, such as the logic questions discussed earlier. Design your questions to fit your needs, but be sure to cover adequate ground. What is the purpose? What question are we trying to answer? What point of view is being expressed? What assumptions are we or others making? What are the facts and data we know, and how do we know them? What are the concepts we’re working with? What are the conclusions, and do they make sense? What are the implications?

4. Cultivate “Habits of Mind”

“Habits of mind” are the personal commitments, values, and standards you have about the principle of good thinking. Consider your intellectual commitments, values, and standards. Do you approach problems with an open mind, a respect for truth, and an inquiring attitude? Some good habits to have when thinking critically are being receptive to having your opinions changed, having respect for others, being independent and not accepting something is true until you’ve had the time to examine the available evidence, being fair-minded, having respect for a reason, having an inquiring mind, not making assumptions, and always, especially, questioning your own conclusions—in other words, developing an intellectual work ethic. Try to work these qualities into your daily life.

- "logic." Wordnik . n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016 . ↵

- "Student Success-Thinking Critically In Class and Online." Critical Thinking Gateway . St Petersburg College, n.d. Web. 16 Feb 2016. ↵

- Outcome: Critical Thinking. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Self Check: Critical Thinking. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Foundations of Academic Success. Authored by : Thomas C. Priester, editor. Provided by : Open SUNY Textbooks. Located at : http://textbooks.opensuny.org/foundations-of-academic-success/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- Image of woman thinking. Authored by : Moyan Brenn. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/8YV4K5 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking. Provided by : Critical and Creative Thinking Program. Located at : http://cct.wikispaces.umb.edu/Critical+Thinking . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking Skills. Authored by : Linda Bruce. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Project : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lumencollegesuccess/chapter/critical-thinking-skills/. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of critical thinking poster. Authored by : Melissa Robison. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/bwAzyD . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Thinking Critically. Authored by : UBC Learning Commons. Provided by : The University of British Columbia, Vancouver Campus. Located at : http://www.oercommons.org/courses/learning-toolkit-critical-thinking/view . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking 101: Spectrum of Authority. Authored by : UBC Leap. Located at : https://youtu.be/9G5xooMN2_c . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of students putting post-its on wall. Authored by : Hector Alejandro. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/7b2Ax2 . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Image of man thinking. Authored by : Chad Santos. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/phLKY . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Critical Thinking.wmv. Authored by : Lawrence Bland. Located at : https://youtu.be/WiSklIGUblo . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

University of Sussex

- Starting at Sussex

- Critical thinking

- Note-making

- Presentations, seminars and group work

- Reading and research

- Referencing and academic integrity

- Revision and exams

- Writing and assessments

- Time management

Adam introduces this section on critical thinking

Adam: Welcome to this section on critical thinking. Critical thinking is a key university skill, but many students find themselves confused about what it actually is. In these pages, you'll find out what critical thinking means. You'll see some examples, and you'll have a chance to practise the skill. Over the academic year we also hold workshops on critical thinking, so keep an eye out for these. Remember, we're here to help you.

Critical thinking is a key skill for university and students can find the concept hard to grasp. However, it is something that you do already; when you choose how to spend your time, which news sources to listen to, and which products to buy. At university, you need to apply this analytical thinking to what you read, hear and write. Additionally, you must make sure to demonstrate that you have done so in your assessments and there is more guidance on how to do this in the Writing and assessments section of Skills Hub.

What do you want to learn about?

It will be beneficial for you to work through this page in its entirety. However, if you only need to focus on aspects of critical thinking consider the questions below:

- Could you define critical thinking to other students? If not , go to the What is Critical Thinking section to find out exactly what it actually is!

- Have you looked at different documents and decided which ones are suitable to use as reliable sources of data in your work? If not , have a look at Critically Evaluating Sources section below to make sure that the materials you are using are good enough for academic writing.

- Are you able to pick out to the line of reasoning that is being made in a lecture or an academic text? If not , try reading through the section below on Identifying and Evaluating Arguments to practise finding a writer’s implicit and explicit arguments.

- Do you question what information you read and hear to understand how far you can trust it and when it may not be useful? If not , visit the Identifying and Evaluating Arguments section below for lots of useful questions to think about whenever you come across new academic information.

- Are you confident spotting mistakes in thinking that writers make, and understanding where they have gone wrong? If not , go to section on Logical and Faulty Thinking below for further details in this area.

- Do you feel comfortable questioning the work of an expert in your subject? If not , visit the section below on Criticising Experts to understand why this is not something to be scared of!

- Do you know how to write a critical essay for university? If not , go to our page on Critical essay writing for detailed information on writing academic essays

Carlee and Rodrigo talk about their understanding of critical thinking

Carlee: I think you hear critical thinking and it's a buzzword. It's something that everyone wants you to know how to do. And tells you it's so important to have to master that it can put a lot of pressure and you're like, what even is critical thinking? And I was exactly the same. I was like, 'Oh, well, you know, I'm being critical.' Like how I translated critical, I was just kind of being negative and like nit picking out like the flaws of things. And it wasn't until, you know, I got some marks back and some feedback and they're like that's not necessarily what critical thought is. It's kind of if you were to look at something and just say, 'How can I break this down into smaller pieces? What's helpful about this? What's not helpful about this? What's the advantages? What's the disadvantages?' And just kind of looking at something in both ways, not just your own perspective - that can kind of help you look at something and say, 'Oh, now I'm being critical about it.'

Rodrigo: Right now I'm writing my essays and when I receive some feedback, I can see completely the difference. It's interesting how at the beginning of my first year I got like two forties and a couple of fifties as well. And I was like, why? Why is this happening? And right now I'm getting like my sixties and my seventies, and I can see a difference. I can definitely see a difference. My essays are more structured. I have more critical thinking like it's supposed to, like my uni wants to and yes, definitely, I can look at something and I'm like, is this really like this, what's the other point? What are the other arguments? Is this person who's talking, is she or he or they biased? Are they biased? So yes, definitely 100%. It's helped me grow and think critically. Yeah, for sure.

For a free introductory critical thinking course, go to Future Learn .

What is critical thinking?

Imagine that someone tells you, “You’re going to need an umbrella.”

Umbrellas Colourful Clipart image under Public Domain license.

You have two options. You could take this information at face value and grab an umbrella. Alternatively, before deciding to do anything, you could think about the statement and ask yourself some questions.

Who said this? Was it a friend, a weather forecaster, a young child?

What are they basing their information on? Are they looking at the clouds, at scientific data, at cows lying in a field?

What are the implications of taking an umbrella? Will you need it straight away? Will you be able to carry it? Could you use something else instead?

What are the assumptions they are making? That dark clouds always produce rain? That people don’t like getting wet? That you are going outside?

With such a simple statement, it is likely that these questions are so automatic and take such little effort that you barely notice yourself asking them.

You need to use the same process in your academic studies. When you come across information, you can take it at face value and accept it as true, or you can step back and ask some questions. The difference is that the information you meet at university is new, more complex and less concrete. Therefore, the process of asking these questions takes more time and needs to be done consciously and deliberately, rather than automatically. This is critical thinking .

The word ‘critical’ often confuses students. Critical thinking does not mean that you need to always find fault with everything. It means that you analyse and evaluate arguments before deciding if you agree with them. Each argument may have some strong points and some weaker ones. Identifying both is important, as is understanding why you think they are strong or weak.

Critically evaluating sources

You are expected to do a lot of research while at university. The books, journal articles and websites recommended on your reading lists have already been evaluated for their quality by your lecturers. When you are asked to find your own information, it’s important to take a critical approach. This starts with looking at the source itself, even before you read the text.

There is a significant difference between an article on "diets which may prevent cancer" published in a popular culture magazine, and one that is published in the Nutrition Research journal. For your work to meet assessment criteria at university level, you need to be able to base it on with acceptable sources which you have evaluated for credibility, reliability and impartiality.

Evaluating academic texts

The journals available through Library Search and your Subject Guides have gone through a rigorous vetting process, known as peer review. Peer review is a process whereby an article submitted to an academic journal is vetted by several experts in that field. The reviewer decides if the article should be published and may make suggestions for changes before publishing. Peer review is a rigorous vetting process. Consequently, peer-reviewed articles are held in higher regard than those which aren't. You can usually rely on these sources.

Open access publishing

If you are searching on Google Scholar or similar search engines and find a scholarly article you can freely access, this article is probably an open access article. The rise of open access publishing has changed the ways scholars share and use journal articles. You need to be extra vigilant when evaluating what appear initially to be scholarly journals.

The growth of open access publishing has resulted in an increase of predatory or vanity publishing. Opportunistic publishing houses publish content in exchange for publication fees, paid for by the authors. These predatory publishers don’t provide any of the editorial and publishing services associated with legitimate academic journals, such as a peer-review process. As a result, unreliable, unvetted publications are published and circulated online. Because of this lack of transparency, you need to be careful with texts from such sources and evaluate them yourselves.

If you have found an open access journal article and want to verify the authenticity as a reputable journal, you can check the name on the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ) .

Evaluating web pages

Anyone can put anything on the internet. It contains a large number of resources that are inaccurate or incorrect. Although some sites do not intend to misinform their readers, others are designed to mislead and so it is important to critically evaluate what you are reading.

Use the CRAAP method, in the table below, to evaluate a web page:

You can download this Method as a Word document or PDF to print out or to save for future use. (Important: The PDF will open in this window so remember to click on the browsers back button to return to the Skills Hub).

Activity: Academic Reliability

Using the table above critically evaluate the following FOUR external sources below to determine whether they are academically reliable. Then select your appropriate response, Yes or No, for each source.

1) Is this source academically reliable?

Correct : The article has been peer reviewed and is written by a credible author who has written and contributed to other academic sources. The author works in a reputable college of medicine and is qualified to write on the topic. A range of views have been consulted and there is a reference list. The purpose of the article is to inform of recent changes in the classification of and criteria for primary psychotic disorders as well as evidence based methodologies.

Incorrect : The article has been peer reviewed and is written by a credible author who has written and contributed to other academic sources. The author works in a reputable college of medicine and is qualified to write on the topic. A range of views have been consulted and there is a reference list. The purpose of the article is to inform of recent changes in the classification of and criteria for primary psychotic disorders as well as evidence based methodologies.

2) Is this source academically reliable?

Incorrect : Although Wikipedia is a useful tool for getting an introduction to an unfamiliar topic, it is not recommended as a source to support academic essay writing. In academic writing you need to consult sources with authority, authors who are experts in their field, qualified to write about a topic. Anyone can edit and add to wikipedia content. A large part of the academic process is research and critical thinking, anyone can google wikipedia, you need to demonstrate your academic skills and critical thinking.

Correct : Although Wikipedia is a useful tool for getting an introduction to an unfamiliar topic, it is not recommended as a source to support academic essay writing. In academic writing you need to consult sources with authority, authors who are experts in their field, qualified to write about a topic. Anyone can edit and add to wikipedia content. A large part of the academic process is research and critical thinking, anyone can google wikipedia, you need to demonstrate your academic skills and critical thinking.

3) Is this source academically reliable?

Incorrect : This is not a peer reviewed article and it is not from a reliable url, it is best to use .org / .edu / .gov / .ac.uk websites. The article does not consult a variety of sources, it only reviews one source therefore, it cannot be relied upon for its accuracy, there could be an element of bias. You should also consider the purpose of this article. It has been written for mental health providers, for the purpose of identifying ways to differentiate between patients feigning mental illness and genuine mental illness. In terms of this article supporting an academic essay, it would not be suitable.

Correct : This is not a peer reviewed article and it is not from a reliable url, it is best to use .org / .edu / .gov / .ac.uk websites. The article does not consult a variety of sources, it only reviews one source therefore, it cannot be relied upon for its accuracy, there could be an element of bias. You should also consider the purpose of this article. It has been written for mental health providers, for the purpose of identifying ways to differentiate between patients feigning mental illness and genuine mental illness. In terms of this article supporting an academic essay, it would not be suitable.

4) Is this source academically reliable?

Correct : This article is relatively current and it has been published by an academically reliable source. The article is aimed at the right level and the author is qualified to write on the topic, their qualifications and profession reflect this. A range of sources have been consulted, data, tables and diagrams are used and verified. In terms of the CRAAP model this article is academically reliable.

Incorrect : This article is relatively current and it has been published by an academically reliable source. The article is aimed at the right level and the author is qualified to write on the topic, their qualifications and profession reflect this. A range of sources have been consulted, data, tables and diagrams are used and verified. In terms of the CRAAP model this article is academically reliable.

Evaluating news sources

If a news article seems too good to be true, or too sensationalist to be correct, it usually is. If you are unsure whether a news source is genuine, refer to the list below. Alternatively, see the International Federation of Library Association's How to Spot Fake News infographic.

Five factors to consider when evaluating a source:

- Fact check. Use fact-checking websites such as factcheck.org to check the credibility of citations and quotes, and tinyeye.com for images

- Verify the URL. Look carefully at the URL address. Fake sites often have urls that are extremely similar to well-known respected news outlets, but with a slight variation. For example, a fake news site modelled on abcnews.com was added to the internet with the URL abcnews.com.co

- Vet the source. Is the source who they say they are? Are they vetted and verified? For example, if the information is coming from Twitter, the account holder will be independently verified if their profile includes a blue checkmark

- Loaded language. Is the headline of the piece phrased in a way that is sensationalist or highly emotional? This is often a manipulative method referred to as loaded language and can be a form of clickbait, enticing the reader to click on the news story

- Adverts. A high proportion of adverts on an article platform or news site can often be a sign of a platform primarily driven by pay-per-clicks, and not by journalistic integrity.

Five tools to help detect misinformation:

- Wayback machine . Search for websites that have since been taken off the internet

- Snopes . Hoax checker

- Quote Investigator . Quote checker

- TinEye and Google Reverse Image Search. Verify images for authenticity; you can search by uploading image files

- Politifact . Political facts checker.

Identifying and evaluating arguments

' Good critical thinking includes recognising good arguments even when we disagree with them, and poor arguments even when these support our own point of view.' Cottrell, S. (2017) Critical Thinking Skills , Third Edition, London, Palgrave, p33

This section is the key to critical thinking. If you are able to follow the argument in a source, and determine its strengths and weaknesses, then you are thinking critically.

Amelia and Georgia talk about developing their critical thinking

Amelia: The critical part I brought to it is like, okay, so this is what I know and this is the knowledge I have. And to first understand before I read something or watch something or see something, it's like, this is what they're trying to teach me. And then having to like get from this point, okay, this is what I know and this is what I'm trying to gain and choosing a path to that is interesting. And it's interesting the whole way through. And when I meet something I don't quite easily understand, it's not like, okay, I'm done. It's like, okay, what are the questions I can ask myself in order to move past this, in order to continue in my understanding.

Georgia: When it came to writing essays, critical thinking is something that I'm assessed quite a bit on and is a very crucial aspect, especially if you want to reach kind of the higher levels, higher grades. And I think at first, it was something that was very unnatural to me and was quite clunky and was sort of just I knew I had to do it. So I had a very basic critical evaluation and then it developed through writing more essays and through just thinking critically in my studies, and it became a lot more natural in how I put it into my essays and how it flowed. So I think it has definitely developed through all those different things.

Identifying arguments and reasons

Before you can evaluate an argument, you must be able to find it. This can be tricky, since lines of reasoning are usually spread throughout a whole text, as the writer slowly builds up their position, layering point after point backed up with evidence, and builds to a final conclusion. Reading abstracts and introductions is very useful to get an overview of an article or book and a summary of the argument that a writer is going to make. Always read them so that you know the general direction of a writer’s argument.

The conclusion is often indicated by signposting phrases such as so, therefore, thus, then, as a result, as a consequence, and for this reason . Generally, writers make their conclusions clear because they want their audience to see and understand them.

- Sustainability is being embedded into the curriculum of several schools at the University of Sussex. As a consequence, more students are learning practical methods of living sustainably for the future.

In the above example, the section after as a consequence is the writer’s conclusion.

Once you have found the conclusion, you also need to find the reasons. Phrases that demonstrate these are more varied, but some common ones are because (of), since, as, the reason being, according to, and considering . Sometimes, such as in the above example, the reasons are not signposted, but simply put before the conclusion.

- Since British students learn to communicate in English classes, and considering that coding is a language which contains many elements of English, then the fundamentals of computational language should be taught to British students in their English classes.

In this example, there are two reasons given for the conclusion. One after since , and one after considering that . The conclusion is signposted with then .

Activity: Identifing the Conclusion

Read the following passage and identify the conclusion and the reasons that the writer makes. The video below the passage gives the solution to this activity.

Some areas of the curriculum are well suited to particular activities. In language-linked and social studies courses, group writing projects offer more benefits to the student than simple improvements in writing skills. The negotiation required by group work encourages semantic webbing, gives practice in the evaluation and organization of gathered information, and offers reflection on the development of knowledge (Andrews, 1992). The group can serve as a respectfully critical audience for individual writing as well, honing the novice writer's presentation style with an immediacy and absence of threat that is less available in traditional assignments. The feedback of peers in the negotiation of the final product helps students gain a sense of authority over their own writing, in turn leading to a greater motivation to write (Chan 1988).

S. Marie A. Cooper. (2002). Classroom Choices for Enabling Peer Learning. Theory Into Practice, 41(1), 53–57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1477538

Answer (video)

So in this passage it is the first sentence, which is the writer's conclusion or the writer's main position. They say that some areas of the curriculum are well suited to particular activities and the rest of the paragraph gives examples and information about the particular activities. In the second sentence, it focuses on language linked and social study courses and talks about group writing projects.

So this is a detail or an example of a particular activity. Then we have different reasons for this, here, all the way to the end of the sentence. There are different reasons for the particular well suitedness of the activities, and you can also see that no examples are given of poor suitedness to the particular activities. In the middle of the passage there is another sub conclusion, which is that the group can serve as respectively critical audience for individual writing as well. And the rest of this sentence explains this further and gives reason. The last sentence is quite interesting because there are two sub conclusions in it. The first sub conclusion is that students gain a sense of authority over their writing, and the beginning of the sentence gives a reason for this.

But then, students gaining a sense of authority over their writing becomes the reason for the final sub conclusion, which is a greater motivation to write. You can see the language here ‘in turn leading to’, highlighting that the previous language, the previous part of the sentence is now turning into a reason. So you have three sub conclusions here, but all of the sub conclusions serve the greater conclusion which is at the beginning of the paragraph, which is that some areas of the curriculum are well suited to particular activities.

Implicit assumptions

Writers may base their conclusions and reasons on assumptions. These can be basic, general, or cultural and they can be very hard to spot. Use your critical thinking to keep an eye out for these assumptions and decide if and how they affect the conclusion.

- Employers need to ensure that their employees are kept safe so that the costs of paying damages to injured workers do not become unfeasible.

An implicit assumption in this example is that the fundemental goal of businesses is to make as much money as possible. This might be a very pervasive mindset in capitalist society, but is it always true? It may be that the writer has designed an argument based on an assumption that you don’t agree with.

From the first assumption come others, such as:

- Employers always want to keep costs down

- Keeping employees safe is only important to employers because they can save money

- The costs of paying damages to injured workers can become unfeasible

- Injured workers demand to be paid damages

- It is the role of employers to keep their employees safe

Once you have identified the underlying assumptions made by a writer, you can then decide if you agree with them or not, and explore the evidence for them.

Sara and Reuben give advice on critical thinking

Sara: So I did A-levels and we didn't do a lot of critical thinking. It was mostly just rote learning and you would kind of read and paraphrase it and then write it back in the exams. So I think, my first few assignments, that's what I did. And the feedback that I got was, well, yes, you've said this, but you haven't evaluated it, you haven't applied any critical thinking. And then I reached out for more support because this was something that I knew was important, not only for that time, but then later on for my dissertation as well. And when I reached out, they directed me to Skills Hub. They gave me their own advice, and it really helped me to understand what critical thinking is so that I could implement it.

Reuben: I think it's a lot about critical thinking, and I feel like that's something that I'm really interested in, in developing, and I feel like I've got a really good strength in it on some level. But also I think I've learned a lot of how to really think about the other side. And within all your essays, you're going to have to include the other side and think critically about why this could, not just like your opinion is the only one. To make your opinions stronger, you really have to understand the whole picture. And that's something that really we had quite a few weeks on that with Sue. So yeah. And the Skill Hub does go through that. So just keep coming back to things because there's many angles to it and you just slowly build up more ways of doing it because it can be quite subtle. Yes, quite subtle ways to do it. And then quiet like obvious ways. But yeah, I think by the end of three years my critical thinking's just going to get better. Each time I realise a little bit more of how to like, approach something.

Evaluating arguments

The conclusions a writer has made, the reasons they have given for their conclusions and the assumptions that they have relied on all make up the writer’s argument , or line of reasoning . Once you can pinpoint this, it is time to start evaluating the argument’s effectiveness.

To do this, you need to reflect on the argument and ask questions of it. In the table below there are some examples of questions you could think about:

You can download this table as a Word document or PDF to print out or to save for future use. (Important: The PDF will open in this window so remember to click on the browsers back button to return to the Skills Hub).

Logical and faulty thinking

Thinking logically.

In logic, an argument can be valid or invalid. This is important for critical thinking because you can use it to determine whether an argument is one you should take seriously to or not.

A valid argument needs two conditions:

- All the premises upon which the argument is based are true.

- The conclusion can be shown to be the result of the premises.

For example:

- John is a human. (premise - true)

- All humans have brains. (premise - true)

- Therefore, John has a brain. (conclusion - valid)

An invalid argument is one in which one or both of the conditions are missing:

- The speed of sound is faster than the speed of light. (premise - not true)

- The speed of sound is 343m/second. (premise - true)

- Therefore, light travels slower than 343m/second. (conclusion - invalid because of a false premise)

- Courtney is a fast runner. (premise - true)

- Courtney is a University of Sussex student. (premise - true)

- Therefore, all University of Sussex students are fast runners. (conclusion – invalid as not the result of the premises)

Sometimes, the conclusion does not follow from the premises but in isolation is still true. In this case though, the argument is still invalid:

- All seagulls are birds. (premise - true)

- Some birds fly. (premise - true)

- Therefore, all seagulls fly. (conclusion – invalid as not the result of the premises)

Examples like the last one are much harder to spot! For practice with analysing logical reasoning, look at the LSAT and GMAT practice papers.

Faulty thinking

There are many ways that premises may not be true, or that conclusions may not follow logically from the premises given. Look out for these errors when analysing academic texts and try to avoid these faults in your own arguments. Below are fourteen explanations and examples (flip card activity) of the more common ones (there is a text only version below the activity):

Activity: Faulty Thinking

(Thanks to Nigel Warburton for many of these examples)

1. Correlation vs causation Just because two things occur at the same time, does not necessarily mean that one causes the other. They may just often correlate together. - Most people with left feet also have right feet. Therefore, having a left foot causes a person to also have a right foot.

2. Reverse causation When two events occur at the same time, make sure the writer is accurately assigning the cause and effect. - The more people using umbrellas outside, the heavier the rain. Therefore, people using umbrellas causes heavy rainfall.

3. Third factor Two events that occur together may actually both be the effect of a third, unmentioned factor. - There is a strong link between people's shoe size and the size of their vocabulary. Therefore. having a large vocabulary causes your feet to grow.

4. Bi-directional causation Two events that occur together may actually be both the effect and the cause of each other. - The most successful students visit the Skills Hub website frequently. This is a just coincidence.

5. Ignoring alternative explanations Make sure that you are watching out for other possible reasons that would also lead to a writer’s conclusions - I always get bad tempered when I have a hangover. I must have a hangover right now, because I am bad tempered.

6. Making implicit assumptions Implicit assumptions are not always wrong, but they are hard to spot. If they are wrong, you must work harder to realise that they are present! - The meal contains nuts, so the patients should not eat it.

7. Generalising from anecdotal evidence

- My friend tried acupuncture and it worked. Therefore, acupuncture can cure anything.

8. Thinking in black and white

- His theory is either completely correct, or 100% wrong.

9. Being inconsistent

- Some people prefer an early start, but everyone likes a lie in.

10. Including irrelevant information

- Let's consider whether music should be taught in schools. My great-grandmother used to send me to sleep by playing lullabies on the trombone.

11. Using emotive language

It is easy to become swept away by words that provoke emotions in the audience, but that cannot be backed up objectively.

- This kind of stupidity is the main threat to the health of our precious young people.

12. Using persuasive language

Words that try to persuade the reader of a particular viewpoint need to be analysed carefully! - Obviously we should follow every instruction issued by a doctor.

13. Over-generalising

- From the two case studies, it is clear that this outcome is inevitable for measles patients.

14. Wishful thinking

- Clearly, sending all patients home at this stage will reduce the cost of care without significantly impairing their recovery.

Criticising experts

A lot of students worry about whether they really can question an expert’s opinions and data. The academic may have been researching and studying the subject for many years whereas you might simply be writing a 1500-word essay on the topic. Is it really possible to critique someone who is so much further along in their knowledge? The answer is yes, for the following reasons:

- Critically analysing theories, pointing out issues with ideas, and suggesting methods of improvement are how scientific and cultural progress occurs. If people didn’t do this, people would still be using astrology to make medical decisions and travelling in bullock carts!

- The fact that there are competing ideas and theories surrounding so many concepts in the world proves that academics disagree with one another. You can disagree too.

- Other students, journalists, academics and thinkers question expert opinion all the time. They are not more intelligent than you.

- You are not looking for the ‘correct’ answer when you think critically. You are only looking at what another person has said and deciding if it is something you can trust or not.

- Academics can be wrong. There are countless examples of mainstream theories that have later been proven false. For instance: Dr Spock’s advice to parents in the 1950’s which caused thousands of cot deaths; Einstein’s stationary universe theory; or the centuries-long idea that Australia was the most southerly landmass on Earth.

- Evidence can be poor. An expert might have carried out a well-designed research project and written up a convincing argument. But perhaps the sample size was very small or the research goes against what 100 other experts are arguing. While they might have made a good start, is the evidence enough to convince you?

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

A Short Guide to Building Your Team’s Critical Thinking Skills

- Matt Plummer

Critical thinking isn’t an innate skill. It can be learned.

Most employers lack an effective way to objectively assess critical thinking skills and most managers don’t know how to provide specific instruction to team members in need of becoming better thinkers. Instead, most managers employ a sink-or-swim approach, ultimately creating work-arounds to keep those who can’t figure out how to “swim” from making important decisions. But it doesn’t have to be this way. To demystify what critical thinking is and how it is developed, the author’s team turned to three research-backed models: The Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment, Pearson’s RED Critical Thinking Model, and Bloom’s Taxonomy. Using these models, they developed the Critical Thinking Roadmap, a framework that breaks critical thinking down into four measurable phases: the ability to execute, synthesize, recommend, and generate.

With critical thinking ranking among the most in-demand skills for job candidates , you would think that educational institutions would prepare candidates well to be exceptional thinkers, and employers would be adept at developing such skills in existing employees. Unfortunately, both are largely untrue.

- Matt Plummer (@mtplummer) is the founder of Zarvana, which offers online programs and coaching services to help working professionals become more productive by developing time-saving habits. Before starting Zarvana, Matt spent six years at Bain & Company spin-out, The Bridgespan Group, a strategy and management consulting firm for nonprofits, foundations, and philanthropists.

Partner Center

- Product overview

- All features

- App integrations

CAPABILITIES

- project icon Project management

- Project views

- Custom fields