REVIEW article

Combating the covid-19 pandemic: experiences of the first wave from nepal.

- 1 Faculty of Science, Nepal Academy of Science and Technology, Lalitpur, Nepal

- 2 Nepal Environment and Development Consultant Pvt. Ltd., Kathmandu, Nepal

- 3 Central Department of Environmental Science, Institute of Science and Technology, Tribhuvan University, Kathmandu, Nepal

- 4 Nepal Development Society, Bharatpur, Nepal

- 5 Kantipur Dental College Teaching Hospital and Research Center, Kathmandu University, Kathmandu, Nepal

- 6 National Disaster Risk Reduction Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal

- 7 Little Buddha College of Health Sciences, Kathmandu, Nepal

Unprecedented and unforeseen highly infectious Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a significant public health concern for most of the countries worldwide, including Nepal, and it is spreading rapidly. Undoubtedly, every nation has taken maximum initiative measures to break the transmission chain of the virus. This review presents a retrospective analysis of the COVID-19 pandemic in Nepal, analyzing the actions taken by the Government of Nepal (GoN) to inform future decisions. Data used in this article were extracted from relevant reports and websites of the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) of Nepal and the WHO. As of January 22, 2021, the highest numbers of cases were reported in the megacity of the hilly region, Kathmandu district (population = 1,744,240), and Bagmati province. The cured and death rates of the disease among the tested population are ~98.00 and ~0.74%, respectively. Higher numbers of infected cases were observed in the age group 21–30, with an overall male to female death ratio of 2.33. With suggestions and recommendations from high-level coordination committees and experts, GoN has enacted several measures: promoting universal personal protection, physical distancing, localized lockdowns, travel restrictions, isolation, and selective quarantine. In addition, GoN formulated and distributed several guidelines/protocols for managing COVID-19 patients and vaccination programs. Despite robust preventive efforts by GoN, pandemic scenario in Nepal is, yet, to be controlled completely. This review could be helpful for the current and future effective outbreak preparedness, responses, and management of the pandemic situations and prepare necessary strategies, especially in countries with similar socio-cultural and economic status.

Introduction

The unanticipated outbreak of the novel coronavirus was first reported in Wuhan, China, in December 2019; it transmits from human to human via droplets and aerosol ( 1 ). The WHO declared Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) on January 30, 2020, and a pandemic on March 11, 2020 ( 2 ). As a result, countries worldwide adopted various mitigative measures ( 3 , 4 ) and eradication strategies ( 5 ), aiming to reduce potentially enormous damage and reach zero cases, respectively. However, significant gaps in advance preparedness and the implementation of response plans resulted in the rapid spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) globally with 219 nations reporting it as of January 22, 2021 1 ( 6 ).

The Federal Democratic Republic of Nepal is a landlocked country in South Asia bordered by India in the south, east, and west, and China in the north. Its population, gross domestic product (GDP), and human development index (HDI) are 29.24 million 2 , 30.64 billion 3 , and 0.579 4 , respectively. The constitution of Nepal (2015) consists of a three-tier (federal, province, and local) governmental system. Each tier has the constitutional power to enact laws and mobilize its resources. In Nepal, the first case of COVID-19 was reported on January 23, 2020, in a 32-year-old Nepalese man who returned from Wuhan, China. Two months after the first case, the second case was diagnosed through domestic testing on March 23 in a returnee from France ( 7 ). Subsequently, the Government of Nepal (GoN) imposed early interventions approved by the WHO, including a travel ban and the Indo-Nepal and China-Nepal borders closure 5 . ( 8 ) to delay the possible onset of the detrimental effects of the outbreak across the country.

This review presents a 1-year (up to January 22, 2021) scenario of COVID-19 in Nepal, reviews the strategies employed by the GoN to control COVID-19, and provides suggestions for the prevention and control of current and future pandemics. Federal, provincial, and district-level daily cases of COVID-19 [confirmed by real-time PCR (qRT-PCR), cured, and death] in Nepal from January 23, 2020, to January 22, 2021, were obtained from the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), GoN 6 . Searches using the website of MoHP of Nepal, PubMed, the WHO, the worldometer official website, and Google were conducted to gather the information on the number of deaths, cured, and confirmed cases of COVID-19 and reports describing the approach taken by the government to contain COVID-19 in Nepal. The search terms included “COVID-19 in Nepal” and “Prevention and management of COVID-19 in Nepal.” Data used in this article were extracted from relevant documents and websites. The figures were constructed by using Origin 2016 and GIS 10.4.1. We did not consult any databases that are privately owned or inaccessible to the public.

Epidemic Status of COVID-19 in Nepal

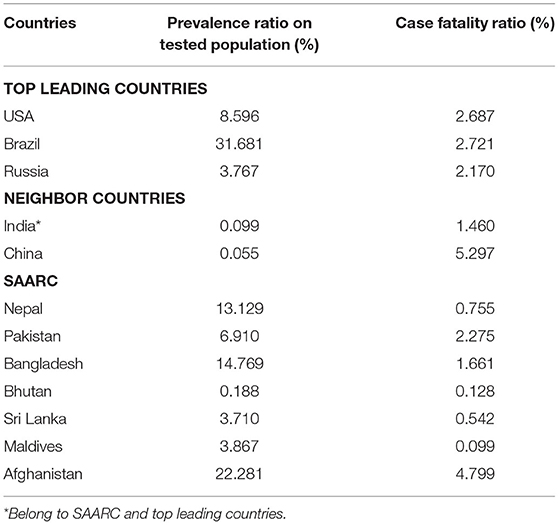

The MoHP of Nepal confirmed the first and second cases of COVID-19, respectively, in January and March, in an interval of 2 months 1 ( 9 ). As of January 22, 2021, 268,948 COVID-19 positive cases were reported, with 263,546 recovered, and 1,986 death cases 6 . This data showed nearly 0.74% death and about 98% recovery rate in Nepal. The case fatality rate (CFR) was 0.5% up to March 30 in Nepal ( 9 ). The CFR in the USA, Brazil, and Russia is similar (~2%), whereas in the South Asian Association of Regional Cooperation (SAARC) countries, the CFR varied from ~0.09 to ~4.7 % ( Table 1 ). In total, 2,035,301 qRT-PCR tests were performed in Nepal, indicating about 13.47% current prevalence of COVID-19 among the qRT-PCR tested population as compared with 2.5% as of March 31, 2020 2 . As of reviewing, the prevalence of COVID-19 among the qRT-PCR tested population is higher than the neighboring countries, China (~0.055%) and India (~0.099%) ( Table 1 ). In addition, up to the third quarter of 2020, <1% of the confirmed COVID-19 cases were symptomatic across all age groups, while the proportion of symptomatic cases progressively increased beyond 55 years of age from 1.3 to 9% 7 , 8 . Unlike Nepal, higher symptomatic cases were reported from other parts of the world during the same period ( 10 ). Understandably, the scenario of the proportion of symptomatic to asymptomatic cases remains to vary between countries and care facilities. Few possible reasons for low symptomatic cases reported in the Nepalese population may be poor health-seeking behavior and utilization of tertiary health care services ( 11 ) for mild symptomatic cases, home isolation without a diagnosis, and a high rate of self-medication practices ( 12 ).

Table 1 . Prevalence and case fatality ratio (CFR) of COVID-19 of top leading countries, neighbor countries of Nepal, and SAARC as of Jan 28, 2021.

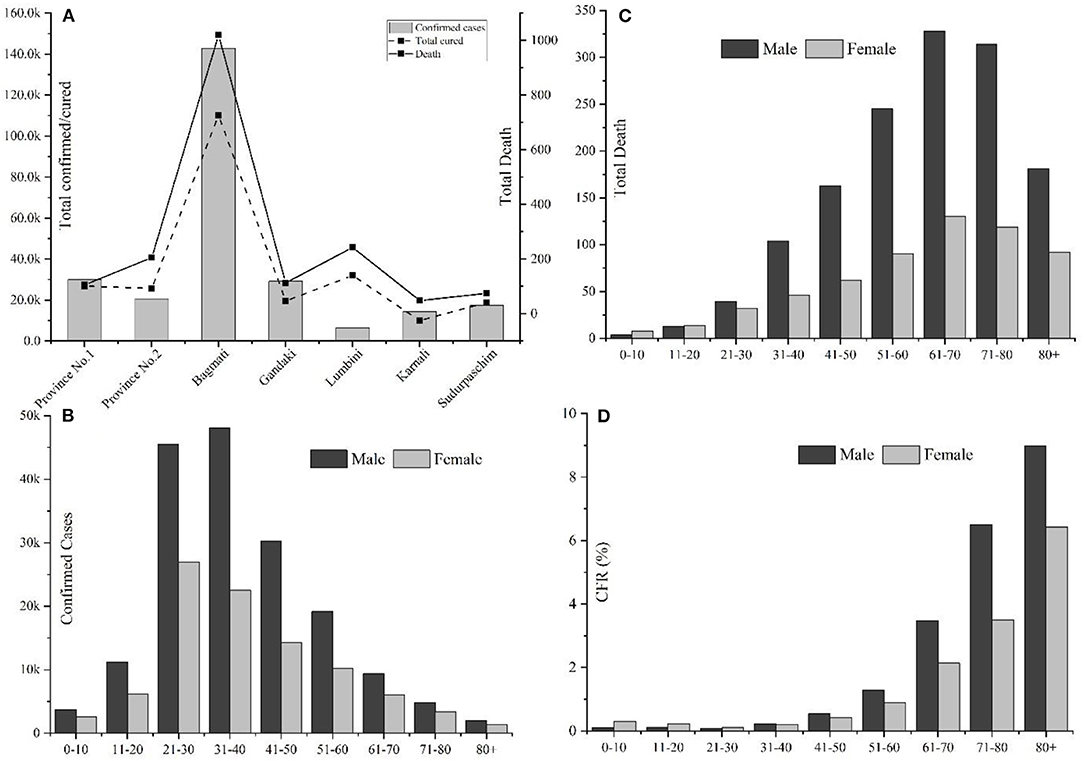

Among the provinces, Bagmati province ( n = 144,278) has the highest number of confirmed cases in Nepal, followed by province no. 1 ( n = 30,422) and Lumbini ( n = 30,308) ( Figure 1A ). As depicted in Table 2 , the confirmed cases of COVID-19 are distributed throughout the country in all the administrative districts. The total number of confirmed cases is highest in the Kathmandu district ( n = 103,523) followed by Lalitpur ( n = 16,106), Morang ( n = 13,236), and Rupandehi ( n = 9,708) districts and lowest in Manang ( n = 20), Mugu ( n = 37), Mustang ( n = 43), and Humla ( n = 44) districts ( Table 2 ).

Figure 1 . Overview of COVID-19 cases in Nepal up to January 22, 2021. (A) Province-wise distribution of total confirmed cases, recovery, and deaths; (B) Gender, age-wise distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases; (C) Gender-age wise distribution of COVID-19 death cases; and (D) Age and gender-wise case fatality rate (CFR) in Nepal.

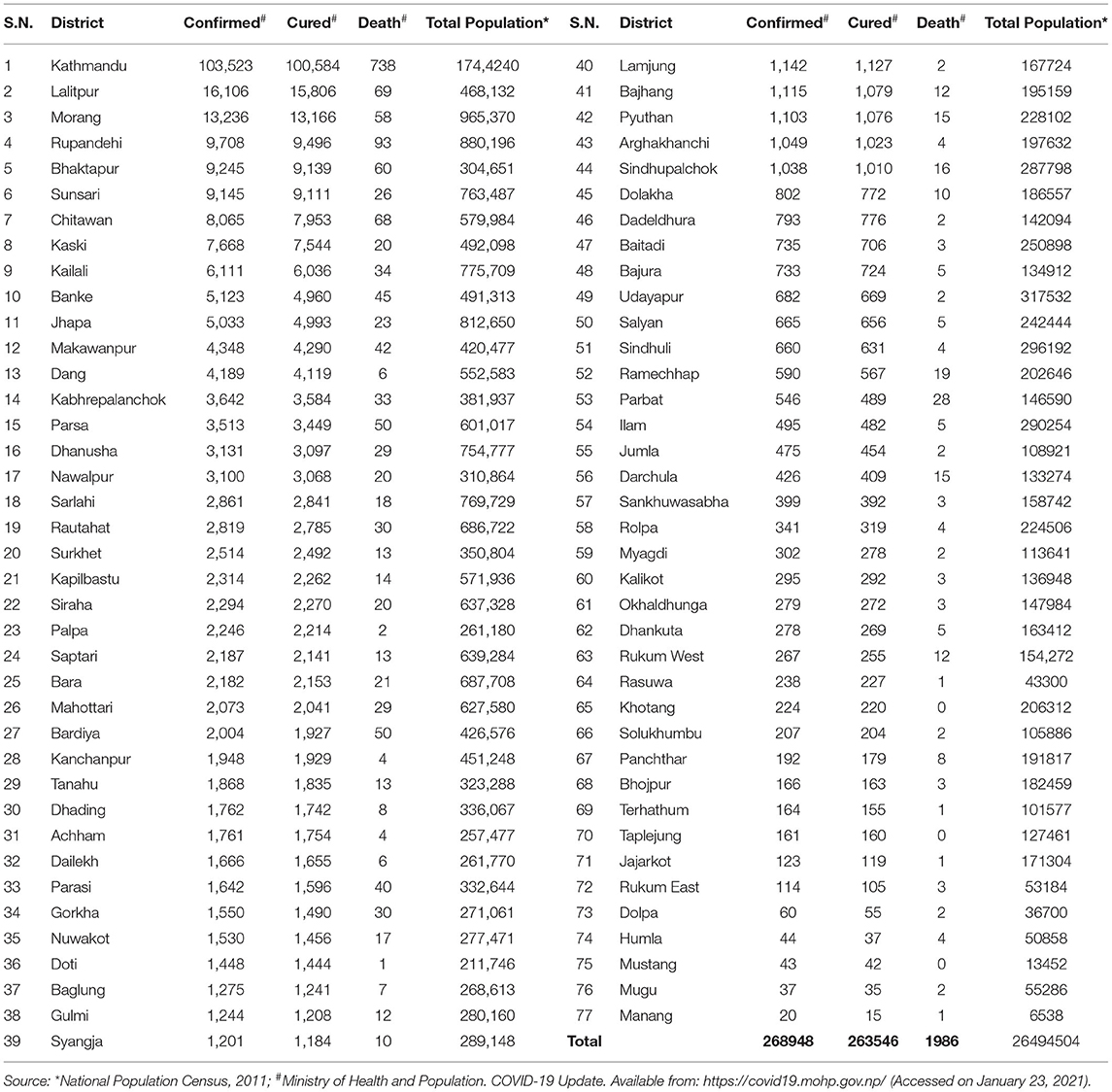

Table 2 . District wise distribution of confirmed cases, recoveries, and deaths due to COVID-19 and total population in Nepal.

Among 268,948 confirmed cases, 174,193 were males, and 94,755 were females, with a male-to-female sex ratio of 1.85. The largest number of infected cases was reported in the age group 21–30 years (26.92%, n = 72,396), followed by the age group of 31–40 years (26.26%, n = 70,648) ( Figure 1B ); however, the number of death cases was higher in the age group 61–70 (23%, n = 458) ( Figure 1C ). A higher death trend in old age is also observed in Europe, America, and Asian countries ( 13 , 14 ). Overall, male death was ~2.33 times the death rate of females. Reports have indicated that men are at greater risk of around two time of acquiring severe outcomes of COVID-19, including hospitalizations, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and deaths ( 15 ). The enhanced susceptibility of males for COVID-19 associated adverse events may be correlated with the hormonal and immunological differences between males and females ( 15 , 16 ). Among a total of 1,986 fatal cases (Male: n = 1,391; female: n = 595), over half ( n = 1,166) were observed in senior adults (≥60 years). One early study among the Nepalese children suggested that male children were more commonly infected than female children ( 17 ).

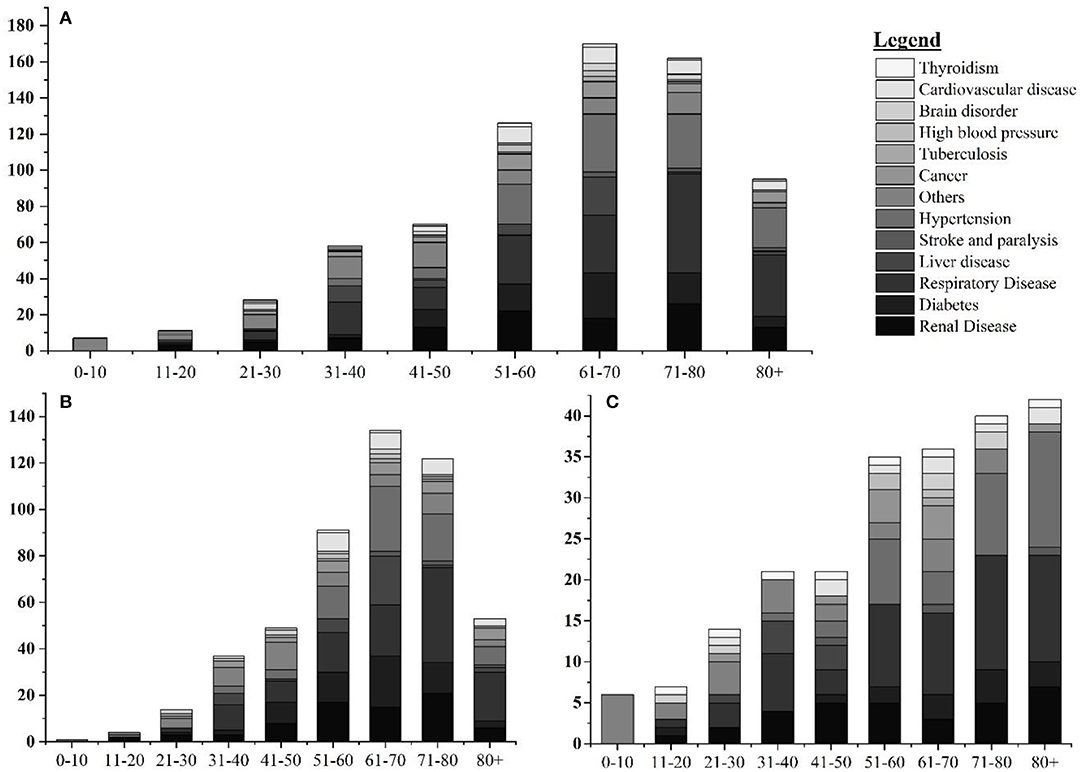

Among 1,986 fatal cases (mean age: 66.15 years), 623 (31.37%), 721 (36.30%), and 642 (32.32%) were with no report of comorbidities, with single comorbidities, and with multiple comorbidities, respectively. In cases with single comorbidities, the highest incidence was reported in respiratory disease ( n = 184) followed by hypertension ( n = 117), renal disease ( n = 107), diabetes ( n = 77), liver disease ( n = 44), and cardiovascular disease ( n = 36) ( Figure 2 ). Similar results are reported from other parts of the world ( 18 ). The detailed epidemiological trend analysis of COVID-19 in Nepal is shown in Figure 3 .

Figure 2 . Age and gender-wise distribution fatal cases with single comorbidities. (A) Age-wise distribution of leading single comorbidities among COVID-19 deaths; (B) age-wise distribution of leading single comorbidities among COVID-19 deaths in Nepal in male; and (C) age-wise distribution of leading single comorbidities among COVID-19 deaths in Nepal in female.

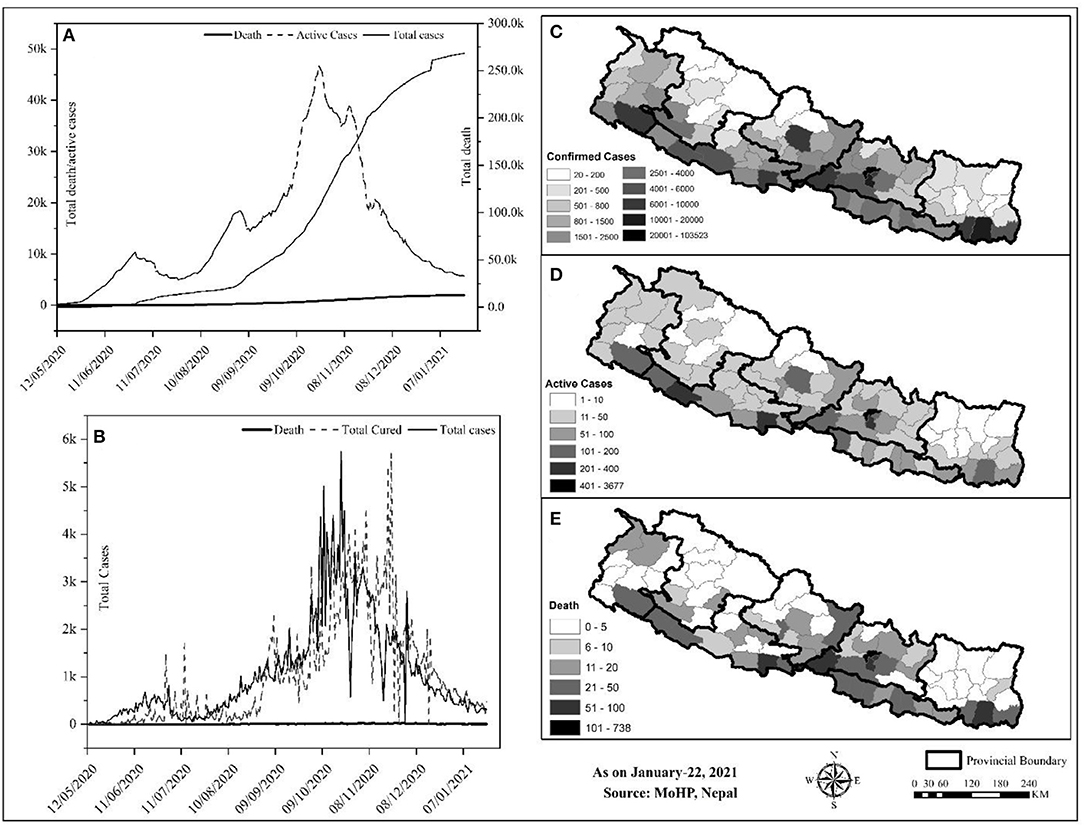

Figure 3 . Trend and spatial distribution of COVID-19 cases in Nepal. (A) Cumulative trend analysis of COVID-19 cases, (B) daily case wise trend analysis of COVID-19, (C–E) spatial distribution of infected, recovered, and death cases.

Geographically, Nepal is divided into three distinct ecological zones, mountain, hilly, and low-plain land from north to south. Politically, Nepal is divided into 7 provinces, 77 districts, and 753 local bodies. There were multiple peaks of active cases of COVID-19 in Nepal: active cases rapidly increased from early May to early July 2020, then increased slowly up to late July and increased at a higher rate again up to the end of December, and then decreased sharply ( Figure 3A ). The spatial distribution of COVID-19 confirmed cases, recovery, and deaths were compared ( Figures 3B–D ). Approximately, 64.84% of the total confirmed cases were reported from the hill regions, with single megacity Kathmandu contributing nearly half, 33.31% of lowland-plain areas, and 1.85% of Himalayan regions. The reported cases in the megacities are relatively higher than in the other regions. The higher number of cases in megacities may be correlated with dense populations in these areas ( 8 ). In the earlier months, the testing facilities and contact tracing were limited only to few districts, including the capital, Kathmandu, which gradually became available in other parts of the country. However, the testing frequency and testing facilities are still not homogeneous due to the lack of required technical resources and professional workforces ( 19 ) 9 .

The Response of Nepal Government to COVID-19

Nepal has adopted many readiness and response-related initiatives at the federal, provincial, and local government levels to fight against COVID-19. Initially, the government had set health desks and allocated spaces for quarantine purposes at the international airport and at the borders, crossing points of entry (PoE) with India and China 10 , to withstand the influx of many possible infected individuals from India and other countries. The open border and the politico-religious relationship with India and migrant workers returning from the Middle East, and other countries were a source of rapid transmission to Nepal 10 , 11 . The Nepal-China official border crossing points have remained closed since January 21, 2020. On March 24, 2020, the GoN imposed a complete “lockdown” of the country up to July 21, 2020. As part of the lockdown, businesses were closed, the restriction was imposed on movement within the country, workplaces were closed, travel was banned, and air transportation was halted 11 , 12 . In addition, for COVID-19 preparedness and response, the GoN developed a quarantine procedure and issued an international travel advisory notice. Closing the border was critical as Nepal and India share open borders across which citizens travel freely for business and work.

The GoN underestimated both the short and long-term impacts of border closure 11 . Around 2.8 million Nepali migrant workers work in India. Though the GoN discussed holding these workers in India with its Indian counterpart 13 , this plan did not materialize. Nepal has 1,690 km-long open borders with India, which could not keep migrant workers long despite the restrictions implemented by both governments 12 . As a consequence, the majority of COVID-19 cases were in the districts along the Indo-Nepal border. The decision of the government to lockdown the country from March 10, 2020, without sufficient preparation pushed daily wage laborers in urban areas to lose their jobs, and, hence, they were trapped without food or money. Ultimately, after a couple of days of lockdown, both migrant workers and daily wage laborers started walking the long way home due to the economic crisis.

As per the cabinet decision on March 25, 2020, Nepal established a COVID-19 response fund, developed a relief package 13 , and distributed relief to families in need through a “one door policy” 13 designed to reduce the COVID-19 impact; however, there were several gaps: the selection of families was unfair, GoN delayed the procurement of relief, relief packages did not include cash, and relief materials were inadequate and substandard 14 , 15 . The government has not adequately taken into account the impact of COVID-19 on the socio-economic sector. For instance, people participated in meetings, rallies, political demonstrations, and protests, where the virus could quickly spread among a large group of people. The government has, yet, to develop a stimulus package for social and economic recovery at the micro and macro levels. As the government has allocated $788 million for the health sector for the fiscal year (July–June 2020), a budget of 32% larger than the previous fiscal year, it should address the COVID-19 impact on the socio-economic front 16 . There is an opportunity to integrate all fragmented social protection schemes to strengthen socio-economic conditions and to emphasize more tremendous efforts, capacities, and resources to cope with the likely impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic 16 .

In addition, a minimal standard of quarantine as per the “Quarantine Operation and Management Protocol” (2076 B.S.) and “Standards for Home Quarantine” were imposed for all provinces 16 , 17 . The Sukraraj Infectious and Tropical Disease Hospital (SITDH) in Teku, Kathmandu, was designated by GoN as the primary hospital for COVID-19 cases along with Patan Hospital, the Armed Police Forces Hospital, in the Kathmandu Valley, followed by twenty-four hubs, and four satellite hospitals across the country 18 . Similarly, MoHP updated the National Public Health Laboratory (NPHL) capacity for confirmatory laboratory diagnosis of the COVID-19 from January 27, 2020, followed by the regional laboratory. The interim guideline for the establishing and operating of molecular laboratories for COVID-19 testing in Nepal was imposed to make uniformity in the test results 14 . Furthermore, the NPHL organized the training of trainers for laboratory staff in collaboration with the Medical Laboratory Association of Nepal 19 Ministry of Health and Population established two hotline numbers (1115 and 1133) to address public concerns, and prepared and disseminated regular press briefings, and improved its websites to channel appropriate information to the public. Besides, MoHP also conveyed decisions, notices, and situation updates periodically through its websites. Further, the Health Emergency Operation Centre (HEOC) of MoHP launched a “Viber communication group” to circulate updates on COVID-19 11, 13 . Early testing and timely contact tracing are crucial restrictive policies to control the spreading of the SARS-CoV-2 virus ( 20 , 21 ); however, in the earlier days of the pandemic, Nepal could not perform enough diagnostic tests and timely contact tracing; it resulted in a crucial time lag in identifying and isolating COVID-19 patients and caused delays in the ability of government to respond to the pandemic adequately. To alert and improve the testing and tracing response of the government, youth-led protests were carried out in different parts of the country 20 . Health Sector Emergency Response Plan was implemented in May 2020, focusing on the COVID-19 pandemic. This plan intends to prepare and strengthen the health system response capable of minimizing the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Government of Nepal devised a comprehensive plan on March 27, 2020, for quarantining people who arrived in Nepal from COVID-19 affected countries. The GoN had initially airlifted 175 Nepalese from six cities across Hubei Province of China on February 15, 2020, followed by Middle East countries, Australia, and so on 13 .

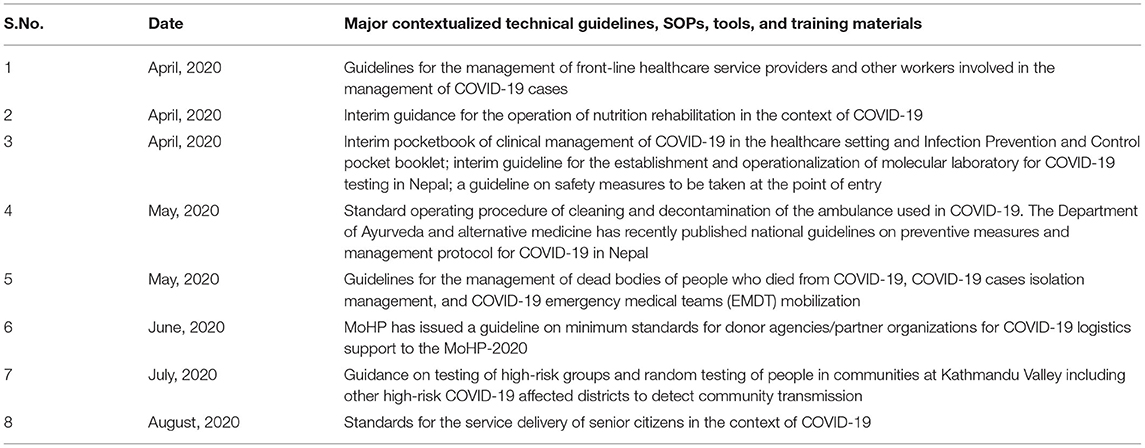

Ministry of Health and Population engaged in developing, endorsing, improving, and disseminating contextualized technical guidelines, standard operating procedures (SOPs), tools, and training in all other critical aspects of the response to COVID-19, for instance, surveillance, case investigation, laboratory testing, contact tracing, case detection, isolation and management, infection prevention and control, empowering health and community volunteers, media communication and community engagement, rational use of personal protective equipment (PPE), requirements of drugs and equipment for case management and public health interventions, and continuity of essentials services 13 ( 15 ). The major contextualized technical guidelines, SOPs, tools, and training materials developed by GoN to respond to COVID-19 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 were listed in Table 3 .

Table 3 . Major contextualized technical guidelines, standard operating protocols, tools, and training materials developed by the Government of Nepal (GoN) to respond to COVID-19.

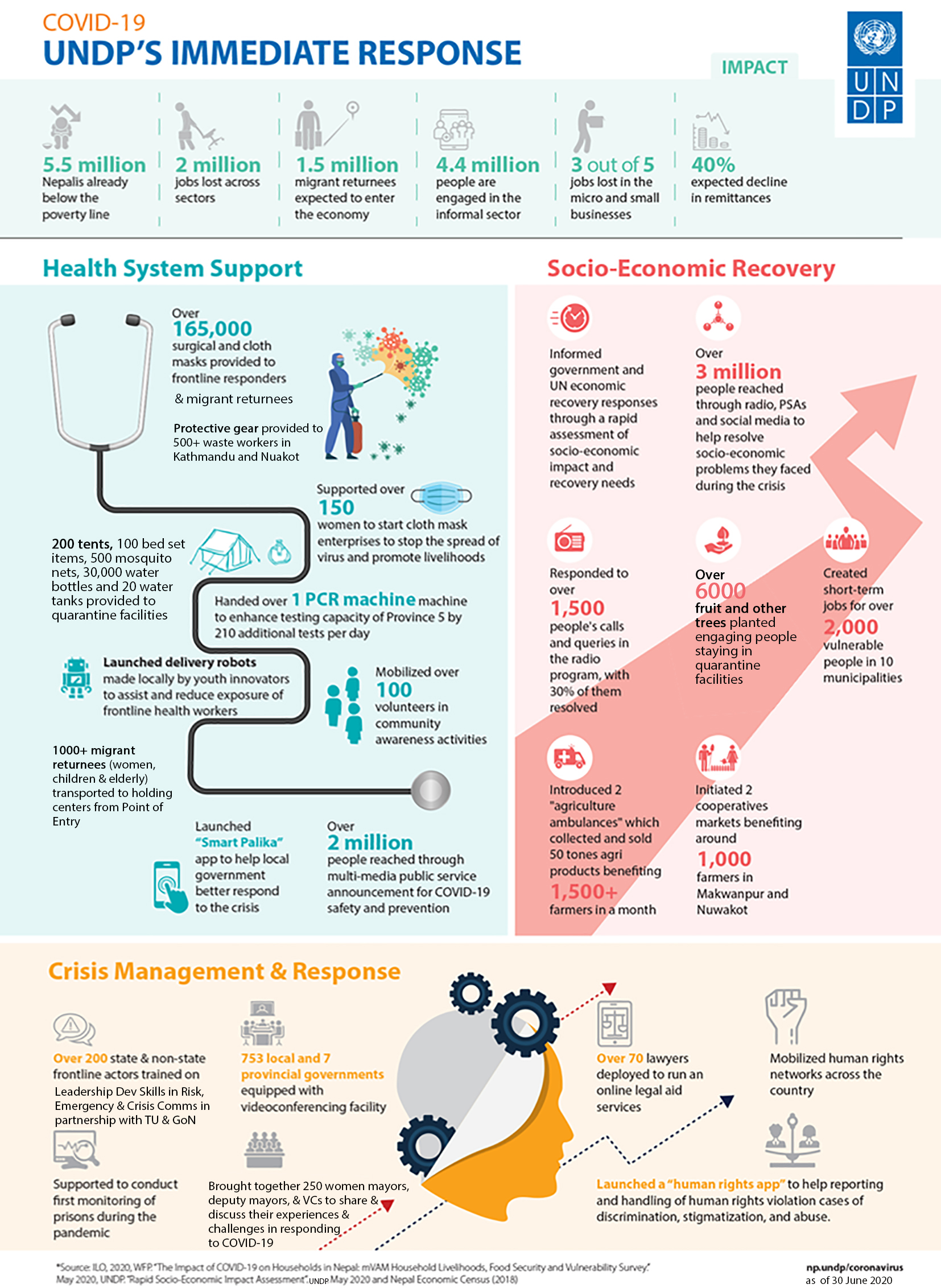

Ministry of Health and Population and supporting organizations, such as United Nations Development Program (UNDP), UNICEF, and World Vision managed crucial supplies of PPE, facemasks, gloves, and sanitizers to ensure the protection of frontline workers and supporting staffs 13 , 30 , 31 , 32 . The frontline media of the nation increased online awareness programs via the involvement of celebrities, doctors, and experts of microbiology and infectious diseases on physical distancing and the importance and use of masks and sanitizers to prevent the COVID-19 contagion. In addition, camping programs were launched by the involvement of youth volunteers of the community in central Nepal 33 .

Government of Nepal received funds from the World Bank ($29 million), the United States of America ($1.8 million), and Germany ($1.22 million) to keep people protected from COVID-19 through health systems preparedness, emergency response, and research. In addition, support from UNICEF and countries, including China, India, and the USA, in the form of emergency medical supplies and equipment were received within January 2020 to March 2020. Private companies, corporate houses, business organizations, and individuals have also contributed to the prevention, control, and treatment fund of coronavirus ($13.8 million), established by GoN to cope with COVID-19. The Prime Minister Relief Fund is also expected to be utilized. The GoN allowed international NGOs to divert 20% of their program budget to COVID-19 preparedness and response; for instance, the Social Welfare Council has allocated $226 million 31 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 .

The GoN has formed a committee to coordinate the preparedness and response efforts, including the MoHP, Ministry of Home Affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation, Ministry of Urban Development, Nepal Army, Nepal Police, and Armed Police Force. The Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) includes the Red Cross Movement and civil society organizations (national and international NGOs). Under the joint leadership of the office of Resident Coordinator and the WHO, the HCT has initiated contingency planning and preparedness interventions, including the dissemination of communications materials to raise community-level awareness across the country 21 . The clusters led by the GoN and co-led by the International Astronomical Search Collaboration (IASC) cluster leads and partners are working on finalizing contingency plans, which will be consolidated into an overall joint approach with the Government and its international partners. The UN activated the provincial focal point agency system to support coordination between the international community and the GoN at the provincial level 21 .

However, despite these robust efforts implemented by GoN, few lapses existed. Examples are the following: issues of inconsistent implementation of immigration policies usually at Indo-Nepal borders 38 , 39 , 40 , shortage and misuse of crucial protective suits and other supplies in hospitals, the ease and the end of lockdown, lack of poor infrastructure facilities, and continuous spread of COVID-19 across the country ( 19 ). The GoN decided to lift the lockdown effective from July 22, 2020, completely; however, the socio-administrative and health measures with the potential for high-intensity transmission (colleges, seminars, training, workshops, cinema halls, party palaces, dance bars, swimming pools, religious places, etc.) remained closed until the following directive as of September 1, 2020. Long route bus services and domestic and international passenger flights were halted until August 1, 2020 41 . A high-level committee at the MoHP has requested all satellite hospitals (public, private, and others) to allocate 20% of their beds for COVID-19 cases. The respective hub hospitals coordinate with the HEOC and satellite hospitals to manage COVID-19 cases 42 . After lifting lockdown for 3 weeks, the federal government has given authority to local administrations to decide on restrictions and lockdown measures as COVID-19 cases continue to rise. In addition, the authority to impose necessary restrictions if COVID-19 active cases surpass the threshold of 200 was given to the Chief District Officer (CDO) 43 . Since March 2020, all the central hospitals, provincial hospitals, medical colleges, academic institutions, and hub-hospitals were designated to provide treatment care for COVID-19 cases. At this stage of operation, the major challenges for the COVID-19 response were managing quarantine facilities, lack of enough human resources, having limited laboratories for testing, and availability of limited stock of medical supplies, including PPEs 14 . To the best of our knowledge, this pandemic is the most extensive public health emergency the GoN faced in its recent history.

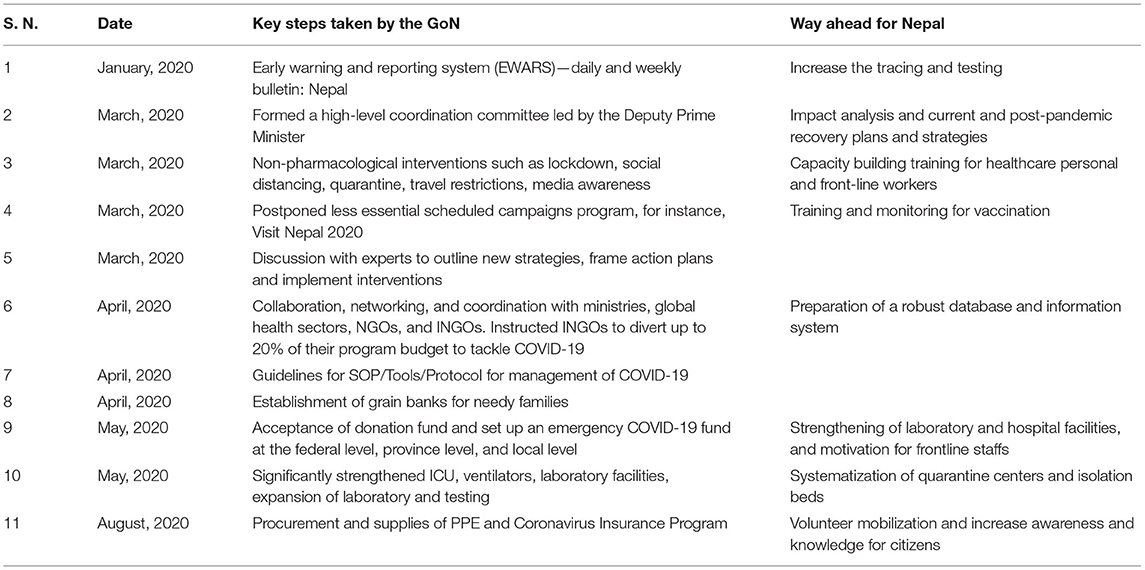

There is no doubt that GoN has taken major initiatives to fight the COVID-19 pandemic. The MoHP, together with associated national and international organizations are closely monitoring and evaluating the signs of outbreaks, challenges, and enforcing the plan and strategies to mitigate the possible impact; however, many challenges and difficulties, such as management of testing, hospital beds, and ventilators, quarantine centers, frontline staffs, movement of people during the lockdown, are yet to be solved 18 , 30 , 38 , 44 , 45 , 46 , 47 . Therefore, in the opinion of the authors, we recommend some steps to be implemented as soon as possible to mitigate and lessen the impacts of COVID-19 ( Table 4 ).

Table 4 . Major steps taken by GoN and way forward in the response to COVID-19 outbreak.

To strengthen its coordination mechanism, the government formed a team to monitor conditions and measures applied to control the outbreak; a COVID-19 coordination committee 11 to coordinate the overall response, and a COVID-19 crisis management center 14 to coordinate daily operations; however, these teams and committees did not function efficiently because roles and authorities were not delegated to ministries and government. A new institution was created, instead of using the National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority (NDRRMA) 48 , which enhanced additional confusion. The MoHP is responsible for overall policy formulation, planning, organization, and coordination of the health sector at federal, provincial, district, and community levels during the COVID-19 pandemic situation. Allegedly, there is an opportunity to strengthen coordination among the tiers of governments by following protocols and guidance for effective preparedness and response. For example, some quarantine centers were so poorly run that, in turn, could potentially develop into breeding grounds for the COVID-19 transmission 15 .

Finally, this study only focuses on analyzing COVID-19 data extracted from the MoHP database for 1 year. Furthermore, we did not quantify the effectiveness of the strategies of GoN and the role of non-governmental organizations and authorities to combat COVID-19 in Nepal.

This study provides an insight into the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic from the Nepalese context for the period of first-wave from January 2020 to January 2021. Despite the several initiatives taken by the GoN, the current scenario of COVID-19 in Nepal is yet to be controlled in terms of infections and mortality. A total of 268,948 confirmed cases and 1,986 deaths were reported in one year period. The maximum number of cases were reported from Bagmati province ( n = 144,278), all of the 77 districts were affected. The cases showing highly COVID-specific symptoms were low (<1%) in comparison with the reports across the globe ( 10 ), which may be because the average age of the Nepalese population is younger than many of the highly affected European countries. The other reasons may be differences in demographic characteristics, sampling bias, healthcare coverage, testing availability, and inconsistencies relating to the reporting of the data included in the current study. Both the number of infections and deaths are higher in males than in females. Despite the age, testing and positivity, hospital capacity and hospital admission criterion, demographics, and HDI index, the overall case fatality was reported to be less than in some other developed countries ( Table 1 ). Consistent with reports from other countries ( 22 , 23 ), the death rate is higher in the old age group ( Figure 1 ). Spatial distribution displayed the cases, which are majorly distributed in megacities compared with the other regions of the country.

Based on this assessment, in addition to the WHO COVID-19 infection prevention and control guidance 49 , some recommendations, such as massive contact tracing, improving bed capacity in health care settings and rapid test, proper management of isolation and quarantine facilities, and advocacy for vaccines, may be helpful for planning strategies and address the gaps to combat against the COVID-19. Notably, the recommendations provided could benefit the governmental bodies and concerned authorities to take the appropriate decisions and comprehensively assess the further spread of the virus and effective public health measures in the different provinces and districts in Nepal. In this review, we have summarized the ongoing experiences in reducing the spread of COVID-19 in Nepal. The Nepalese response is characterized by nationwide lockdown, social distancing, rapid response, a multi-sectoral approach in testing and tracing, and supported by a public health response. Overall, the broader applicability of these experiences is subject to combat the COVID-19 impacts in different socio-political environments within and across the country in the days to come.

Author Contributions

BB: Conceptualization, writing, and original draft preparation. KB, BB, and AG: data curation. BB, RP, TB, SD, NP, and DG: writing, review, and editing. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

KB and AG were employed by Nepal Environment and Development Consultant Pvt. Ltd., in Kathmandu, Nepal.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP), Government of Nepal, for supporting data in this research. We are thankful to the reviewers for their meticulous comments and suggestions, which helped to improve the manuscript.

1. ^ Worldometer. COVID-19 Coronavirus Pandemic . (2020). Available online at: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

2. ^ Worldometer. Nepal Population . (2020). Available online at: https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/nepal-population/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

3. ^ Trading Economics. Nepal GDP . (2020). Available online at: https://tradingeconomics.com/nepal/gdp (accessed January 15, 2021).

4. ^ UNDP. Human Development Reports . (2020). Available online at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/countries/profiles/NPL (accessed January 15, 2021).

5. ^ World Health Organization. COVID-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan (NPRP) . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/covid-19-nepal-preparedness-and-response-plan-(nprp)-draft-april-9.pdf?sfvrsn=808a970a_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

6. ^ Ministry of Health and Population. COVID-19 Update . (2020). Available online at: https://covid19.mohp.gov.np/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

7. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-19 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/19-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c9fe7309_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

8. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-22 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/22-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=df7c946a_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

9. ^ World Health Organization. (2020). WHO Nepal Situation Updates-16 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/16–who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-07082020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=53c5360f_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

10. ^ Bhattarai, KD. South Asian Voices: COVID-19 and Nepal's Migration Crisis . Available online at: https://southasianvoices.org/covid-19-and-nepals-migration-crisis/ (accessed January 15, 2021).

11. ^ GRADA WORLD Nepal: Government announces nationwide lockdown from March 24–31/update . Available online at: https://www.garda.com/crisis24/news-alerts/326601/nepal-government-announces-nationwide-lockdown-from-march-24-31-update-4 (accessed January 15, 2021).

12. ^ Gautam D. NDRC. Nepal's Readiness and Response to COVID-19 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.preventionweb.net/files/71274_71274nepalsreadinessandresponsetopa.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

13. ^ Building Back Better (BBB) from COVID-19: World Vision Policy Brief on Building Back Better from COVID-19 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.wvi.org/sites/default/files/202005/World%20Vision%20Policy%20Brief%20on%20Building%20Back%20Better_25%20May%202020.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

14. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-1 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-20apr2020.pdf?sfvrsn=c788bf96_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

15. ^ GoN MoHP. Health Sector Emergency Response Plan COVID-19 Pandemic 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/health-sector-emergency-response-plan-covid-19-endorsed-may-2020.pdf?sfvrsn=ef831f44_2 (accessed January 15, 2021).

16. ^ Gautam, D. The COVID-19 Crisis in Nepal: Coping Crackdown Challenges. National Disaster Risk Reduction Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal. Issue 3, 2020 . Available online at: https://www.alnap.org/help-library/the-covid-19-crisis-in-nepal-coping-crackdown-challenges (accessed January 30, 2021).

17. ^ Gautam, D. Fear of COVID-19 Overshadowing Climate-Induced Disaster Risk Management . Available online at: https://www.spotlightnepal.com/2020/05/08/fear-covid-19-overshadowing-climate-induced-disaster-risk-management/ (accessed January 30, 2021).

18. ^ Pradhan TR. The Kathmandu Post. Nepal Goes Under Lockdown for a Week Starting 6am Tuesday . Available online at: https://kathmandupost.com/national/2020/03/23/nepal-goes-under-lockdown-for-a-week-starting-6am-tuesday (accessed January 30, 2021).

19. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-3 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–situpdate-3-covid-19-06052020.pdf?sfvrsn=714d14c4_2 (accessed January 30, 2021).

20. ^ Jha IC. The Rising Nepal. MoHP Sets Forth Standards for Home Quarantine . Available online at: https://risingnepaldaily.com/featured/mohp-sets-forth-standards-for-home-quarantine (accessed January 30, 2021).

21. ^ The Kathmandu Post. Youth-Led Protests Against the Government's Handling of Covid-19 Spread to Major Cities . (2020). Available online at: https://kathmandupost.com/national/2020/06/12/youth-led-protests-against-the-government-s-handling-of-covid-19-spread-to-major-cities (accessed January 30, 2021).

22. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-2 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-29apr2020.pdf?sfvrsn=dac001bf_2 (accessed January 30, 2021).

23. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-4 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/who-nepal–situpdate-4-13052020.pdf?sfvrsn=630b68ea_6 (accessed January 30, 2021).

24. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-18 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/18-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19-23082020.pdf?sfvrsn=6fb20500_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

25. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-5 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/5-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-20052020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=7552c8ba_4 (accessed February 5, 2021).

26. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-7 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/7-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-03062020-final.pdf?sfvrsn=87f582d6_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

27. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-8 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/8-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=ce5ecb07_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

28. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-10 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/10-who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-24062020.pdf?sfvrsn=c7f99a61_8 (accessed February 5, 2021).

29. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-13 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/13–who-nepal–situpdate-covid-19-17072020-v4.pdf?sfvrsn=fc0f19cc_2 (accessed February 5, 2021).

30. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-17 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/17-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19-15082020.pdf?sfvrsn=68a53b32_2 (accessed February 10, 2021).

31. ^ UN. Nepal Information Platform, COVID-19 Nepal: Preparedness and Response Plan . Available online at: http://un.org.np/reports/covid-19-nepal-preparedness-and-response-plan (accessed February 10, 2021).

32. ^ UNICEF for Every Child, Supporting COVID-19 Readiness and Response in the West of Nepal . Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/nepal/stories/supporting-covid-19-readiness-and-response-west-nepal (accessed February 10, 2021).

33. ^ UNDP. Enhancing Public Awareness on COVID-19 Through Communications . Available online at: https://www.np.undp.org/content/nepal/en/home/presscenter/articles/2020/Enhancing-public-awareness-of-COVID-19-through-communications.html (accessed February 10, 2021).

34. ^ The World Bank. The Government of Nepal and the World Bank sign $29 Million Financing Agreement for Nepal's COVID-19 (Coronavirus) Response . Available online at: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2020/04/03/world-bank-fast-tracks-29-million-for-nepal-covid-19-coronavirus-response (accessed February 10, 2021).

35. ^ Khatri PP. The Rising Nepal. Govt Receives Over Rs 1.59 Bln In Anti-COVID-19 Fund . Available online at: https://risingnepaldaily.com/main-news/govt-receives-over-rs-159-bln-in-anti-covid-19-fund (accessed February 10, 2021).

36. ^ Dahal A. Govt Does U-Turn to Let NGOs Hand Out Medical Supplies, Food, Cash directly . Available online at: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/govt-does-u-turn-to-let-ingos-hand-out-medical-supplies-food-cash-directly/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

37. ^ Rijal A. The Rising Nepal. China Gives Anti-Corona Medical Aid . Available online at: https://risingnepaldaily.com/main-news/china-gives-anti-corona-medical-aid (accessed February 10, 2021).

38. ^ Nepali Sansar. Nepal Receives 23 Tons ‘COVID-19 Medical Equip' As Gifts from India . (2020). Available online at: https://www.nepalisansar.com/coronavirus/nepal-receives-23-tons-covid-19-medical-equip-as-gifts-from-india/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

39. ^ Koirala S, Bhattarai, S. My Republica. Protect Frontline Healthcare Workers . Available online at: https://myrepublica.nagariknetwork.com/news/protect-frontline-healthcare-workers/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

40. ^ Halder R. Lockdowns and national borders: How to manage the Nepal-India border crossing during COVID-19 . Available online at: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/southasia/2020/05/19/lockdowns-and-national-borders-how-to-manage-the-nepal-india-border-crossing-during-covid-19/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

41. ^ Raturi K. How Is Nepal Tackling COVID Crisis & Reverse Migration of Workers? Available online at: https://www.thequint.com/voices/opinion/india-nepal-border-coronavirus-pandemic-migrant-workers-exodus-reverse-migration-unemployment (accessed February 10, 2021).

42. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-14 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/14–who-nepal–sitrep-covid-19-26072020.pdf?sfvrsn=65868c9e_2 (accessed February 10, 2021).

43. ^ World Health Organization. WHO Nepal Situation Updates-19 on COVID-19, 2020 . (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/19-who-nepal-sitrep-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=c9fe7309_2 (accessed February 10, 2021).

44. ^ Prasain S, Pradhan TR. The Kathmandu Post . Available online at: https://kathmandupost.com/politics/2020/08/12/nepal-braces-for-a-return-to-locked-down-life-as-rise-in-covid-19-cases-rings-alarm-bells (accessed February 10, 2021).

45. ^ NHPL. Information regarding Novel Corona Virus . (2020). Available online at: https://www.nphl.gov.np/page/ncov-related-lab-information (accessed February 10, 2021).

46. ^ NHRC. Assessment of Health-related Country Preparedness and Readiness of Nepal for Responding to COVID-19 Pandemic Preparedness and Readiness of Government of Nepal Designated COVID Hospitals . (2020). Available online at: http://nhrc.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Fact-sheet-Preparedness-and-Readiness-of-Government-of-Nepal-Designated-COVID-Hospitals.pdf (accessed February 10, 2021).

47. ^ Koirala S. Comprehensive response to COVID 19 in Nepal . Available online at: https://en.setopati.com/blog/152612 (accessed February 10, 2021).

48. ^ National Disaster Risk Reduction and Management Authority, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of Nepal . Available online at: https://covid19.ndrrma.gov.np/ (accessed February 10, 2021).

49. ^ World Health Organization. Infection Prevention and Control Guidance - (COVID-19) . (2021). Available online at: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public (accessed February 10, 2021).

1. Jayaweera M, Perera H, Gunawardana B, Manatunge J. Transmission of COVID-19 virus by droplets and aerosols: a critical review on the unresolved dichotomy. Environ Res. (2020) 188:109819. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109819

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Zheng J. SARS-CoV-2: an emerging coronavirus that causes a global threat. Int J Biol Sci. (2020) 16:1678–85. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.45053

3. Islam N, Sharp SJ, Chowell G. Physical distancing interventions and incidence of coronavirus disease 2019: natural experiment in 149 countries. BMJ. (2020) 370:27–43. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2743

4. Gupta A, Singla M, Bhatia H, Sharma V. Lockdown-the only solution to defeat COVID-19. Int J Diabetes Dev Ctries. (2020) 6:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s13410-020-00826-3

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Lu G, Razum O, Jahn A, Zhang Y, Sutton B, Sridhar D, et al. COVID-19 in Germany and China: mitigation versus elimination strategy. Glob. Health Action . (2021). 14:1875601. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2021.1875601

6. The Lancet. COVID-19: too little, too late. Lancet . (2020) 395:P755. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30522-5

7. Bastola A, Sah R, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Lal BK, Jha R, Ojha HC, et al. The first 2019 novel coronavirus case in Nepal. Lancet Infect Dis. (2020) 20:279–80. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30067-0

8. Dhakal S, Karki S. Early epidemiological features of COVID-19 in Nepal and public health response. Front. Med. (2020) 7:524. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2020.00524

9. Panthee B, Dhungana S, Panthee N, Paudel A, Gyawali S, Panthee S. COVID-19: the current situation in Nepal. New Microbes New Infect. (2020) 37:100737. doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100737

10. Oran DP, Topol EJ. The proportion of SARS-CoV-2 infections that are asymptomatic: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. (2021) 174:655–62. doi: 10.7326/M20-6976

11. Bhattarai S, Parajuli SB, Rayamajhi RB, Paudel IS, Jha N. Clinical health seeking behavior and utilization of health care services in eastern hilly region of Nepal. J Coll Med. Sci Nepal . (2015). 11:8–16. doi: 10.3126/jcmsn.v11i2.13669

12. Paudel S, Aryal B. Exploration of self-medication practice in Pokhara valley of Nepal. BMC Public Health. (2020) 20:714. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-08860-w

13. Ioannidis JPA, Axfors C. Contopoulos-Ioannidis DG. Population-level COVID-19 mortality risk for non-elderly individuals overall and for non-elderly individuals without underlying diseases in pandemic epicenters. Environ Res . (2020) 188:109890. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109890

14. Cortis D. On determining the age distribution of COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Publ. Health. (2020) 8:202. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00202

15. Gebhard C, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Neuhauser HK, Morgan R, Klein SL. Impact of sex and gender on COVID-19 outcomes in Europe. Biol Sex Differ. (2020) 11:29. doi: 10.1186/s13293-020-00304-9

16. Sharma G, Volgman AS, Michos ED. Sex differences in mortality from COVID-19 pandemic: are men vulnerable and women protected? JACC Case Rep. (2020) 2:1407–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.027

17. Sharma AK, Chapagain RH, Bista KP, Bohara R, Chand B, Chaudhary NK, et al. Epidemiological and clinical profile of COVID-19 in Nepali children: an initial experience. J Nepal Paediatr Soc. (2020) 40:202–9. doi: 10.3126/jnps.v40i3.32438

18. Piryani RM, Piryani S, Shah JN. Nepal's response to contain COVID-19 infection. J Nepal Health Res Counc. (2020) 18:128–34. doi: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i1.2608

19. Rayamajhee B, Pokhrel A, Syangtan G. How well the government of nepal is responding to COVID-19? An experience from a resource-limited country to confront unprecedented pandemic. Front Public Health. (2021) 9:597808. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.597808

20. Kretzschmar ME, Rozhnova G, Bootsma MC, van Boven M, van de Wijgert JH, Bonten MJ. Impact of delays on effectiveness of contact tracing strategies for COVID-19: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. (2020) 5:e452–9. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30157-221

21. Contreras S, Biron-Lattes JP, Villavicencio HA, Medina-Ortiz D, Llanovarced-Kawles N, Olivera-Nappa Á. Statistically-based methodology for revealing real contagion trends and correcting delay-induced errors in the assessment of COVID-19 pandemic. Chaos Solit Fract . (2020). 139:110087. doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110087

22. Levin AT, Hanage WP, Owusu-Boaitey N, Cochran KB, Walsh SP, Meyerowitz-Katz G. Assessing the age specificity of infection fatality rates for COVID-19: systematic review, meta-analysis, and public policy implications. Eur J Epidemiol. (2020) 35:1123–38. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00698-1

23. O'Driscoll M, Dos Santos GR, Wang L, Cummings DA, Azman AS, Paireau J, et al. Age-specific mortality and immunity patterns of SARS-CoV-2. Nature . (2021). 590:140–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2918-0

Keywords: COVID-19, pandemic, preparedness, response, spatial distribution, public health, Nepal

Citation: Basnet BB, Bishwakarma K, Pant RR, Dhakal S, Pandey N, Gautam D, Ghimire A and Basnet TB (2021) Combating the COVID-19 Pandemic: Experiences of the First Wave From Nepal. Front. Public Health 9:613402. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.613402

Received: 05 October 2020; Accepted: 11 June 2021; Published: 12 July 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Basnet, Bishwakarma, Pant, Dhakal, Pandey, Gautam, Ghimire and Basnet. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Til Bahadur Basnet, ddst19basnet@hotmail.com

† These authors have contributed equally to this work

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- GET INVOLVED

COVID-19 pandemic

Covid-19 pandemic response.

Humanity needs leadership and solidarity to defeat the coronavirus

The coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic is the defining global health crisis of our time and the greatest challenge we have faced since World War Two. Since its emergence in Asia late last year, the virus has spread to most of the countries.

Nepal, a landlocked country aspiring to graduate from a Least Developed Country status, stands highly vulnerable to the unfolding COVID-19 pandemic. Heedful of its vulnerabilities, the Government of Nepal has enforced a nationwide lockdown and activated its federal, provincial and local level mechanisms to respond to the crisis. While there is an urgent need to strengthen the existing health system to handle the situation in case of any sudden surge of outbreak, standardize the quarantine facilities and provide immediate relief to the most-affected, equally important is to help the country mitigate the socio-economic impacts and prepare for a longer-term recovery.

The secondary impact of the global pandemic is huge and it is already taking a serious toll on an economy that relies heavily on remittances, imports fueled by remittances, informal labor, and tourism revenues.

UNDP is working with the Government of Nepal and the UN Country Team to support the country's preparedness to face the mounting public health emergency, respond to the socio-economic impact of the protracted lockdown on the most vulnerable, and support longer-term recovery measures.

The fact that Nepal’s economy is largely dependent on remittance (25% of GDP), tourism (8% of GDP), agriculture (26% of GDP) and imports of essential items and supplies from outside has made the poor households and the often unskilled workers, including returnee migrants, particularly vulnerable to income losses.

Given that most of these people are outside the official social safety net, they are likely to bear the brunt of the sudden halt or slowdown of economic activities in Nepal.

UNDP response

As part of the UN family and in close coordination with the World Health Organization (WHO), UNDP is responding to requests from national and sub-national governments to help them prepare for, respond to and recover from the COVID-19 pandemic, focusing particularly on the most vulnerable and where they are found. While needs assessments are being drawn, our short and medium-term response will mainly translate in activities that focus on the three major areas: Health System Suppor, Socio-economic Recovery and Crisis Management and Response .

“We are already hard at work, together with our UN family and other partners, on three immediate priorities : supporting the health response including the procurement and supply of essential health products, under WHO’s leadership, strengthening crisis management and response, and addressing critical social and economic impacts.” UNDP Administrator, Achim Steiner

Health system support

Complementing the work of the specialized agencies to bolster health systems management and capacity, UNDP is supporting the provincial and local governments to strengthen their health systems , including by providing much-needed medical supplies, assessment of quarantine facilities and public awareness on COVID-19. The major activites are as follows:

- Enhancing public awareness on COVID19 thorugh communications (PSAs , Community level activities)

- Management of quarantine facilities through monitoring and assessment and logistics support

- Strengthening health support system

- Launched delivery robots to help frontline healthworkers

UNDP provides 400 oxygen concentrators to Nepal on June 11 2021

Socio-Economic Recovery

UNDP is using its extensive experience of working on early recovery, livelihood support and job creation by mobilizing cooperatives, developing enterprises and community infrastructures. Some of the key activites are as follows:

- Rapid assessment of socio-economic impact and recovery needs

- Short-term employment programme and livelihood recovery for the most vulnerable

- Support to local farmers for supply and delivery of their produces

- Green initiatives supporting livelihood

- Promoting women entreprenuers in local mask making

Women in Pokhara are on the frontline of mask production during the COVID-19 pandemic. This has helped address the problems of shortage and possible black marketing of masks, while also giving them a decent living amidst the crisis.

Crisis management and response

UNDP will also focus on enhancing crisis response and management capacities at the sub-national level, which include communication support and skill transfer to provincial governments and municipalities. Here are some of the key activites:

- Support the overall UN wide Preparedness and Response Plan and co-lead the Socio-Economic Recovery Cluster

- Communications support to provincial and local governments

- Live phone-in radio program aimed at helping connect people with government authorities and inform policies

- Crisis Communications training to representatives of local governments and other actors

Radio journalists at work. The Association of Community Radio Broadcasters (ACORAB) in Nepal and Community Information Network (CIN), with the support of UNDP, have launched a live phone-in radio program, which aims to help local governments address socio-economic issues/problems faced by the vulnerable people during the COVID-19 lockdown. Photo: CIN

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- News & Views

- Twin crises in Nepal:...

Twin crises in Nepal: covid-19 and climate change

- Related content

- Peer review

- Basu Dev Pandey , doctor and professor 1 2 ,

- Kouichi Morita , professor 3 ,

- Anthony Costello , professor of global health and sustainable development 4

- 1 Everest International Clinic and Research Center, Kathmandu, Nepal,

- 2 Department of Molecular Epidemiology, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Japan

- 3 Department of Virology, Institute of Tropical Medicine, Nagasaki University, Japan

- 4 University College London, UK

Nepal has been on the frontline of both the covid-19 pandemic and climate change, and in both crises the response by the international community and Nepal’s government has been marked by a failure to prepare or to invest proactively in strong prevention measures.

The first case of covid-19 in Nepal was reported in January 2020 and the country’s modest first wave peaked in late October 2020 with a case fatality rate of less than 1%. 1 2 As cases fell steadily in January 2021, the government relaxed—a response that would turn out to be premature.

Throughout spring 2021, hundreds of thousands of people assembled on the streets in party political activities to prepare for the May election, adding to the number of people already joining gatherings for seasonal weddings and religious festivals. Meanwhile, in March 2021 the new delta variant, considered more infectious and virulent by the World Health Organization (WHO), was contributing to surging case numbers in India. 3 In April, at a time when cases in India were steadily rising, an estimated 50 000 Nepali pilgrims went to northern India for Kumbh Mela, a Hindu festival participated in by millions of people. 4 While there, many of the pilgrims caught covid-19.

Thousands of migrant workers also crossed over into Nepal from India, bringing the Delta strain with them, where it spread rapidly through the populous Kathmandu valley. 5 In Kathmandu, the hallways and courtyards of hospitals became crowded with patients competing to get a bed linked to an oxygen supply. Many patients were turned away due to lack of oxygen, ICU beds, and ventilators. Nepal’s president called a state of health emergency and 75 out of 77 districts had imposed a lockdown by 23 May. Nepal’s Ministry of Health and Population (MoHP) reported the country’s highest number of daily deaths (246) so far on 19 May 2021. 6

Restrictions were lifted as cases fell in July 2021 but the number of deaths surged again in August with a test positivity rate of 24% and more than 2500 cases recorded per day. 7 Many people in Nepal’s scattered rural population lack access to tests and deaths go unrecorded—a situation that is little different from India, where estimates suggest there were as many as 3.4-4.9 million excess deaths from the pandemic’s start to June 2021, numbers that are around 10-fold higher than official reports. 8 Hospitals and ICUs were full again during this period, including many severe cases in children. This wave hit the country so hard because communities were unprepared, the government had a false sense of security, residents relaxed social distancing, and authorities allowed religious festivals and political gatherings to go ahead as normal. The country still faces shortages of oxygen, ventilators, and other intensive care equipment.

Vaccines could have helped to relieve this pressure on Nepal’s hospitals, but the country has been beset by difficulties in obtaining them. At the end of March 2021, at a crucial point in the pandemic, India banned exports of AstraZeneca jabs until 2022. 9 This included one million doses already purchased by Nepal. By 11 December 2021, just 30% of the population had received two doses of the vaccine. 10 Nepal was not in a strong position then as the new omicron variant emerged and began to spread globally. First reported in Nepal by its MoHP in late December 2021, the omicron variant peaked with more than 10 000 daily cases on 18 January 2022. 11 12 More than 600 healthcare workers at the five biggest public hospitals in Kathmandu were infected and their absence added to the strain on the health system. 12 The number of daily deaths was much lower in the third wave (32 at its peak compared with 246 in the second wave) and cases dropped quickly to 2.9 per 100 000 population at the national level by the first week of March. 13 14 15 As before, the India-Nepal border was without strict screening, social distancing restrictions were relaxed, and compliance with public health protocols was often poor, all contributing to this third wave. But the introduction of covid-19 vaccination undoubtedly helped to reduce hospitalisations and mortality.

Against the backdrop of the covid-19 pandemic, another crisis unfolded. The annual monsoon season beginning in June 2021 brought flooding and landslides like never before across many of Nepal’s districts. Major rivers and streams swelled dangerously, and people lost their lives. After 200 mm of rain fell in six days up to 14 June, floods from the Melamchi river alone swept away 13 suspension bridges, seven motor bridges, and numerous stretches of road, destroying 337 houses, 259 enterprises, and thousands of acres of rice paddies. 16 The risk of flooding grows as glaciers in the Himalayas melt as a result of both rising temperatures and the proliferation of black carbon deposits from industry, vehicles, and cooking. 17

The government was overwhelmed, lacking as they do comprehensive plans for monsoon flooding. They mobilised the army and the Red Cross to assist communities, and arranged safe areas, drinking water, and food supplies. But they have no early warning systems, no anticipatory plans in place, and poor communication with many officials in local municipalities. A flood warning via Twitter was only sent out on 16 June—two days after dangerous flooding was first reported. 18 The country’s disaster budgets are tiny and procurement law does not allow relief materials and equipment to be bought in advance—only after disaster strikes subject to government approval. 19 Policies that build resilience against climate related disasters should be a top priority for the government because, while the pandemic may recede, the impacts of climate change will only worsen.

The latest reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have been red alerts for the world, describing climate change as widespread, rapid, and intensifying. 20 The mountain ranges of South Asia contain almost 55 000 glaciers that store more freshwater than anywhere but the North and South Poles. A World Bank report estimates that global black carbon emissions could be cut in half with policies that are currently economically and technically feasible, allied with the cuts in carbon emissions set out in the Paris Agreement. 21 Without urgent action, glacier melt will threaten hundreds of millions of people in Nepal, Afghanistan, India, Pakistan, China, and beyond.

As a low income country, Nepal deserves much greater international support through the Covax scheme to provide vaccines, diagnostics, and treatments, and for climate resilience through the “loss and damage” funds agreed at the COP26 summit in Glasgow. At the same time, Nepal’s government could have done far more to mobilise preventive and responsive measures for these twin crises; making sure the country is better prepared for the next one must be a priority.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; not peer reviewed.

- ↵ Bastola A, Sah R, Rodriguez-Morales A J, Kumar Lal B, et al. The first 2019 novel coronavirus case in Nepal. Lancet Infectious Diseases. 20:3:279 - 280. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30067-0 OpenUrl CrossRef PubMed

- ↵ Ministry of Health and Population, Government of Nepal. Nepal: Covid 19 Response Situation Report No.XXXVI. Dec 14 2020. https://reliefweb.int/report/nepal/nepal-covid-19-response-situation-report-noxxxvi-14-december-2020

- ↵ Sharma G. Covid infections surge in Nepal fuelled by mutant strains in India. Reuters. 26 Apr 2021. https://www.reuters.com/world/china/covid-19-infections-surge-nepal-fueled-by-mutant-strains-india-2021-04-26/

- ↵ Pandey g. India Covid: Kumbh Mela pilgrims turn into super-spreaders. BBC News. 10 May 2021. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-57005563

- Weissenbach B

- ↵ Nepal reports 242 new COVID cases, 1 death on Sunday. Nepal News Nationwide. 12 Dec 2021. https://www.nepalnews.com/s/nation/nepal-reports-242-new-covid-cases-1-death-on-sunday

- ↵ Update S. #68: Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). WHO Country Office for Nepal. Reporting Date: 27 July – 2 August 2021. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/nepal-documents/novel-coronavirus/who-nepal-sitrep/-68_weekly-who-nepal-situation-updates.pdf?sfvrsn=bb521cc0_5

- ↵ Anand A, Sandefur J, Subramanian A. Three New Estimates of India’s All-Cause Excess Mortality during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Centre for Global Development Working Paper. 20 Jul 2021. https://www.cgdev.org/publication/three-new-estimates-indias-all-cause-excess-mortality-during-covid-19-pandemic

- ↵ Gettleman J, Schmall E, Mashal M. India Cuts Back on Vaccine Exports as Infections Surge at Home. The New York Times. 25 Mar 2021. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/25/world/asia/india-covid-vaccine-astrazeneca.html

- ↵ Poudel A. Nepal receives 1 965 600 doses of Moderna vaccine from COVAX. The Kathmandu Post. 12 Dec 2021. https://kathmandupost.com/health/2021/12/12/nepal-receives-1-965-600-doses-of-moderna-vaccine-from-covax

- ↵ Poudel A. Nepal reports new Omicron case. The Kathmandu Post. 22 Dec 2021. https://kathmandupost.com/health/2021/12/22/nepal-reports-new-omicron-case-third-to-date

- ↵ Nepal faces new omicron-fueled coronavirus surge. Deutsche Welle. 19 Jan 2022. https://www.dw.com/en/nepal-faces-new-omicron-fueled-coronavirus-surge/a-60481393

- ↵ Omicron: Nepal makes quarantine mandatory for travellers arriving from 67 countries. The Times of India. 18 Dec 2021. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/articleshow/88352043.cms?utm_source=contentofinterest&utm_medium=text&utm_campaign=cppst

- ↵ Nepal Covid-19 tally: 3,540 new cases, 6,359 recoveries, 32 deaths in 24 hours. Onlinekhabar. 30 Jan 2022. https://english.onlinekhabar.com/nepal-covid-19-tally-3540-new-cases-6359-recoveries-32-deaths-in-24-hours.html

- ↵ World Health Organization Regional Office for South East Asia. COVID-19 Weekly Situation Report: Week #09 (03 March – 09 March 2022). 11 Mar 2022. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/searo/whe/coronavirus19/sear-weekly-reports/searo-weekly-situation-report-9-2022.pdf?sfvrsn=f712043a_7

- ↵ Maharjan SB, Steiner JF, Bhakta Shrestha A, et al. The Melamchi flood disaster: Cascading hazard and the need for multihazard risk management. Disaster Task Force, ICIMOD. 4 Aug 2021. https://www.icimod.org/article/the-melamchi-flood-disaster/

- ↵ Mandal CK. Black carbon speeding up melting of glaciers, posing water scarcity threat to millions, report finds. The Kathmandu Post. 5 Jun 2021. https://kathmandupost.com/climate-environment/2021/06/05/black-carbon-speeding-up-melting-of-glaciers-posing-water-scarcity-threat-to-millions-report-finds

- ↵ Nepal Flood Alert. Twitter. 16 Jun 2021. https://twitter.com/DHM_FloodEWS/status/1405005910997540864

- ↵ Public Procurement Monitoring Office, Government Of Nepal. The Public Procurement Act, 2063 (2007). para 66 https://ppmo.gov.np/image/data/files/acts_and_regulations/public_procurement_act_2063.pdf

- ↵ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate change widespread, rapid, and intensifying. IPCC Report. 9 Aug 2021 https://www.ipcc.ch/2021/08/09/ar6-wg1-20210809-pr/

An Overview of the Impact of COVID-19 on Nepal’s International Tourism Industry

- First Online: 01 November 2022

Cite this chapter

- Asmod Karki ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-2270-0545 5 ,

- Nama Raj Budhathoki ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2041-4986 6 , 7 &

- Deepak Raj Joshi ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5620-7025 8

Part of the book series: Global Perspectives on Health Geography ((GPHG))

378 Accesses

COVID-19 severely impacted Nepal’s economy. The tourism industry, a major contributor to Nepal’s gross domestic product (GDP), has been one of the major sectors to bear the secondary impact due to COVID-19. This chapter provides an overview of the economic and non-economic impact of COVID-19 on the tourism sector. The discussion centers around two major stakeholders: businesses and workers. It also elaborates on the major stakeholders’ expectations on the government to withstand and recover from the economic shock.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

The portal can be accessed here: http://tourismincovid.klldev.org/

The business and workforce survey questionnaires can be downloaded from the landing page of http://tourismincovid.klldev.org/

Based on conversations with labor union leaders on January 10, 2021.

A long list of major tourism projects could be found in the Investment Board Nepal’s site: https://ibn.gov.np/project-bank/

Business Standard India. (2021, August 3). Covid-19 lockdown extended in kathmandu valley . Retrieved from https://www.business-standard.com/article/international/nepal-covid-19-lockdown-extended-in-kathmandu-valley-till-aug-11-121080301817_1.html

C2M2 Kathmandu Portal. (2021). COVID-19 and its impacts on nepalese tourism . Retrieved from http://tourismincovid.klldev.org/

CCMC. (2020). CCMC’s 11th board meeting . Crisis Management Coordination Center. Retrieved from https://ccmc.gov.np/key_decisions/key%20decision%202077.05.29.pdf

Google Scholar

COVID19-Dashboard. (2021). Retrieved from https://covid19.mohp.gov.np/

Department of Immigration. (2021). Arrival departure data from January to December 2020 . Retrieved from https://www.immigration.gov.np/public/upload/e66443e81e8cc9c4fa5c099a1fb1bb87/files/Data_jan_Dec_2020(1).pdf

Department of Immigration. (2022). Arrival and departure record of 2021 . Retrieved from https://www.immigration.gov.np/page/arrival-departure-report?page=1

ILO. (2021). Informal economy in Nepal . Retrieved from https://www.ilo.org/kathmandu/areasofwork/informal-economy/lang%2D%2Den/index.htm

Lal, A. (2017, August 28). From the shangri-la to a hippie paradise. The Record . Retrieved from https://www.recordnepal.com/from-the-shangri-la-to-a-hippie-paradise

Mali, D. S. (2020, January 7). Making visit Nepal 2020 a success. The Himalayan Times . Retrieved from https://thehimalayantimes.com/opinion/making-visit-nepal-2020-a-success

Ministry of Culture, Tourism and Civil Aviation. (2020). Press Release . Retrieved from https://www.tourism.gov.np/files/Press%20RELEASE%20FILE%20PDF/Covid_19_WorkProgress_77_3_19.pdf

Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (2021, June 23). Guidelines to be followed by Nepali and foreign nationals travelling to Nepal . Retrieved from https://mofa.gov.np/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Guidelines-to-be-followed-by-Nepali-and-foreign-nationals-travelling-to-Nepal-2021.pdf

Nepali Sansar. (2020). COVID-19 threat: Nepal government cancels ‘visit Nepal 2020 . Retrieved from https://www.nepalisansar.com/tourism/covid-19-threat-nepal-cancels-visit-nepal-2020/

Nepali Times. (2020). Nepal ends COVID-19 lockdown . Retrieved from https://www.nepalitimes.com/latest/nepal-ends-covid-19-lockdown/

NRB News. (2021). A publication of central bank of Nepal. NRB Monetary Policy for 2020–21 . 41 (1).

Online Khabar. (2021, December 28). Government announcement to give staff 10-day travel leave yet to be implemented . Retrieved from https://english.onlinekhabar.com/travel-leave-not-yet.html

Prasain, S. (2021, June 17). Tourism is Nepal’s fourth largest industry by employment study. The Kathmandu Post . Retrieved from https://kathmandupost.com/money/2021/06/17/tourism-is-nepal-s-fourth-largest-industry-by-employment-study

RSS. (2021). Tourism entrepreneurs demand COVID vaccine within 30 days . Rastriya Samachar Samiti. Retrieved from https://thehimalayantimes.com/nepal/tourism-entrepreneurs-demand-covid-vaccine-within-30-days

Shakya, A. (2017, October 11). A vision for visit Nepal 2020. New Business Age . Retrieved from http://www.newbusinessage.com/MagazineArticles/view/1943

Shivakoti, A. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on tourism in Nepal. The Gaze: Journal of Tourism and Hospitality, 12 (1), 1–22.

Shrestha, P. M. (2020, December 20). Covid-19 affected businesses to protest demanding relief and rehabilitation package . Retrieved from https://kathmandupost.com/money/2020/12/20/covid-19-affected-businesses-to-protest-demanding-relief-and-rehabilitation-package

The World Bank. (2022). International tourism and number of arrivals . The World Bank Group. Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ST.INT.ARVL?locations=NP

Ulak, N. (2021). COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on tourism industry in Nepal. Journal of Tourism & Adventure, 3 (1), 50–75. https://doi.org/10.3126/jota.v3i1.31356

Article Google Scholar

UNDP. (2021). Nepal multidimensional poverty index 2021. UNDP in Nepal . Retrieved from https://www.np.undp.org/content/nepal/en/home/library/poverty/Nepal-MPI-2021.html

WTTC. (2020). Economic impact report . World Travel and Tourism Council. Retrieved from https://wttc.org/Research/Economic-Impact

Download references

Acknowledgements

This book chapter would not have been possible without the exceptional work by a number of people at Kathmandu Living Labs (KLL). We are grateful, in particular, to:

Sazal Sthapit

Arogya Koirala

Aishworya Shrestha

Roshan Poudel

Manoj Thapa

Our special thanks to Dr. Melinda Laituri for her constant encouragement to write this chapter as well as for her constructive feedback on our earlier draft. This research was possible thanks to the Cities’ COVID Mitigation Mapping (C2M2) Program, developed by the U.S. Department of State’s Humanitarian Information Unit and the American Association of Geographers (AAG).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Kathmandu Living Labs, Chundevi, Nepal

Asmod Karki

Nama Raj Budhathoki

Humanitarian OpenStreetMap Team (HOT), Washington DC, USA

World Tourism Network, Honolulu, HI, USA

Deepak Raj Joshi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nama Raj Budhathoki .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, USA

Melinda Laituri

Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI, USA

Robert B. Richardson

Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA, USA

Junghwan Kim

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2022 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Karki, A., Budhathoki, N.R., Joshi, D.R. (2022). An Overview of the Impact of COVID-19 on Nepal’s International Tourism Industry. In: Laituri, M., Richardson, R.B., Kim, J. (eds) The Geographies of COVID-19. Global Perspectives on Health Geography. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11775-6_10

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-11775-6_10

Published : 01 November 2022

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-11774-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-11775-6

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Earth and Environmental Science (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Understanding COVID-19 in Nepal

Affiliation.

- 1 Sukraraj Tropical and Infectious Disease Hospital, Teku, Kathmandu, Nepal.

- PMID: 32335607

- DOI: 10.33314/jnhrc.v18i1.2629

The novel coronavirus COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) was first reported in 31 December 2019 in Wuhan City, China. The first case of COVID-19 was officially announced on 24 January, 2020, in Nepal. Nine COVID-19 cases have been reported in Nepal. We aim to describe our experiences of COVID-19 patients in Nepal. Keywords: COVID-19; experience; Nepal.

- Asymptomatic Diseases

- Betacoronavirus

- Coronavirus Infections / epidemiology*

- Coronavirus Infections / transmission

- Coronavirus*

- Disease Outbreaks

- Health Knowledge, Attitudes, Practice

- Middle Aged

- Nepal / epidemiology

- Pneumonia, Viral / epidemiology*

- Pneumonia, Viral / transmission

- Young Adult

- High contrast

- Children in Nepal

- How and where we work

- Invest in every child

- Our Partners

- Press centre

Search UNICEF

Covid-19 in nepal: assessing impact and opportunities for a child and family-friendly response, a national e-conference on 10 december 2020.

About a year ago , at the International Social Protection Conference (18-19 th November 2019,) the government of Nepal and key members of civil society and development community came together to put together a vison for resilient social protection for all Underlying this vision was the commitment to protect the children, marginalized and the vulnerable from attenuating impacts of a disaster and enable them to access basic services to help then reach their potential. This was before COVID 19, a crisis inflicting hitherto unprecedented impact on lives, economy, jobs livelihoods and childhood. The lessons from this conference are ever more relevant today.

COVID is a crisis of child rights as much a crisis of health and economics. While for adults, the hardship lasting for months and possibly years will be over with slow though inevitable recovery of economies and regeneration of jobs and livelihoods, a large section of children particularly 0-6-year-old, face a future bleaker than before. According to UNICEF’s Child and Family Tracker (CFT), an estimated 6 million children are now in poverty, including multidimensional poverty- a fourfold increase over the pre-COVID stats. Though for many this will be a transitory experience, many more would suffer irreversible loss of their potential of cognitive and physical growth and development, decelerating Nepal’s accumulation of human capital, productivity of labour and the potential for economic growth.

In response to the threat of COVID, Nepal responded with alacrity, imposing a strict lockdown on 23 March which lasted well into July. As a result, economic activity and growth slowed down with millions losing jobs/ earnings. Families with children were especially hit. According to UNICEF’s CFT, about 61 per cent of the respondents of this national 7000 HHs monthly, longitudinal survey have had no earnings in the last three months.