The Argument for Tuition-Free College

Soaring tuitions and student loan debt are placing higher education beyond the reach of many American students. It’s time to make college free and accessible to all.

by Keith Ellison

April 14, 2016

(Shutterstock)

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln signed the Land Grant College Act into law, laying the groundwork for the largest system of publicly funded universities in the world. Some of America's greatest colleges, including the University of Minnesota, were created by federal land grants, and were known as "democracy's colleges" or "people's colleges."

But that vision of a "people's college" seems awfully remote to a growing number of American students crushed under soaring tuitions and mounting debt. One hundred and fifty years after Lincoln made his pledge, it's time to make public colleges and universities free for every American.

This idea is easier than it looks. For most of our nation's history, public colleges and universities have been much more affordable than they are today, with lower tuition, and financial aid that covered a much larger portion of the costs . The first step in making college accessible again, and returning to an education system that serves every American, is addressing the student loan debt crisis.

The cost of attending a four-year college has increased by 1,122 percent since 1978 . Galloping tuition hikes have made attending college more expensive today than at any point in U.S. history. At the same time, debt from student loans has become the largest form of personal debt in America-bigger than credit card debt and auto loans. Last year, 38 million American students owed more than $1.3 trillion in student loans.

Once, a degree used to mean a brighter future for college graduates, access to the middle class, and economic stability.

Today, student loan debt increases inequality and makes it harder for low-income graduates, particularly those of color , to buy a house, open a business, and start a family.

The solution lies in federal investments to states to lower the overall cost of public colleges and universities. In exchange, states would commit to reinvesting state funds in higher education. Any public college or university that benefited from the reinvestment program would be required to limit tuition increases. This federal-state partnership would help lower tuition for all students. Schools that lowered tuition would receive additional federal grants based on the degree to which costs are lowered.

Reinvesting in higher education programs like Pell Grants and work-study would ensure that Pell and other forms of financial aid that students don't need to pay back would cover a greater portion of tuition costs for low-income students. In addition, states that participate in this partnership would ensure that low-income students who attend state colleges and universities could afford non-tuition expenses like textbooks and housing fees . This proposal is one way to ensure that no student graduates with loans to pay back.

If the nation can provide hundreds of billions of dollars in subsidies to the oil and gas industry and billions of dollars more to Wall Street , we can afford to pay for public higher education. A tax on financial transactions like derivatives and stock trades would cover the cost. Building a truly affordable higher education system is an investment that would pay off economically.

Eliminating student loan debt is the first step, but it's not the last. Once we ensure that student loan debt isn't a barrier to going to college, we should reframe how we think about higher education. College shouldn't just be debt free-it should be free. Period.

We all help pay for our local high schools and kindergartens, whether or not we send our kids to them. And all parents have the option of choosing public schools, even if they can afford private institutions. Free primary and secondary schooling is good for our economy, strengthens our democracy, and most importantly, is critical for our children's health and future. Educating our kids is one of our community's most important responsibilities, and it's a right that every one of us enjoys. So why not extend public schooling to higher education as well?

Some might object that average Americans should not have to pay for students from wealthy families to go to school. But certain things should be guaranteed to all Americans, poor or rich. It's not a coincidence that some of the most important social programs in our government's history have applied to all citizens, and not just to those struggling to make ends meet.

Universal programs are usually stronger and more stable over the long term, and they're less frequently targeted by budget cuts and partisan attacks. Public schools have stood the test of time-let's make sure public colleges and universities do, too.

The United States has long been committed to educating all its people, not only its elites.

This country is also the wealthiest in the history of the world. We can afford to make college an option for every American family.

You can count on the Prospect , can we count on you?

There's no paywall here. Your donations power our newsroom as we report on ideas, politics and power — and what’s really at stake as we navigate another presidential election year. Please, become a member , or make a one-time donation , today. Thank you!

About the Prospect / Contact Info

Browse Archive / Back Issues

Subscription Services

Privacy Policy

DONATE TO THE PROSPECT

Copyright 2023 | The American Prospect, Inc. | All Rights Reserved

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, how to write an a+ argumentative essay.

Miscellaneous

You'll no doubt have to write a number of argumentative essays in both high school and college, but what, exactly, is an argumentative essay and how do you write the best one possible? Let's take a look.

A great argumentative essay always combines the same basic elements: approaching an argument from a rational perspective, researching sources, supporting your claims using facts rather than opinion, and articulating your reasoning into the most cogent and reasoned points. Argumentative essays are great building blocks for all sorts of research and rhetoric, so your teachers will expect you to master the technique before long.

But if this sounds daunting, never fear! We'll show how an argumentative essay differs from other kinds of papers, how to research and write them, how to pick an argumentative essay topic, and where to find example essays. So let's get started.

What Is an Argumentative Essay? How Is it Different from Other Kinds of Essays?

There are two basic requirements for any and all essays: to state a claim (a thesis statement) and to support that claim with evidence.

Though every essay is founded on these two ideas, there are several different types of essays, differentiated by the style of the writing, how the writer presents the thesis, and the types of evidence used to support the thesis statement.

Essays can be roughly divided into four different types:

#1: Argumentative #2: Persuasive #3: Expository #4: Analytical

So let's look at each type and what the differences are between them before we focus the rest of our time to argumentative essays.

Argumentative Essay

Argumentative essays are what this article is all about, so let's talk about them first.

An argumentative essay attempts to convince a reader to agree with a particular argument (the writer's thesis statement). The writer takes a firm stand one way or another on a topic and then uses hard evidence to support that stance.

An argumentative essay seeks to prove to the reader that one argument —the writer's argument— is the factually and logically correct one. This means that an argumentative essay must use only evidence-based support to back up a claim , rather than emotional or philosophical reasoning (which is often allowed in other types of essays). Thus, an argumentative essay has a burden of substantiated proof and sources , whereas some other types of essays (namely persuasive essays) do not.

You can write an argumentative essay on any topic, so long as there's room for argument. Generally, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one, so long as you support the argumentative essay with hard evidence.

Example topics of an argumentative essay:

- "Should farmers be allowed to shoot wolves if those wolves injure or kill farm animals?"

- "Should the drinking age be lowered in the United States?"

- "Are alternatives to democracy effective and/or feasible to implement?"

The next three types of essays are not argumentative essays, but you may have written them in school. We're going to cover them so you know what not to do for your argumentative essay.

Persuasive Essay

Persuasive essays are similar to argumentative essays, so it can be easy to get them confused. But knowing what makes an argumentative essay different than a persuasive essay can often mean the difference between an excellent grade and an average one.

Persuasive essays seek to persuade a reader to agree with the point of view of the writer, whether that point of view is based on factual evidence or not. The writer has much more flexibility in the evidence they can use, with the ability to use moral, cultural, or opinion-based reasoning as well as factual reasoning to persuade the reader to agree the writer's side of a given issue.

Instead of being forced to use "pure" reason as one would in an argumentative essay, the writer of a persuasive essay can manipulate or appeal to the reader's emotions. So long as the writer attempts to steer the readers into agreeing with the thesis statement, the writer doesn't necessarily need hard evidence in favor of the argument.

Often, you can use the same topics for both a persuasive essay or an argumentative one—the difference is all in the approach and the evidence you present.

Example topics of a persuasive essay:

- "Should children be responsible for their parents' debts?"

- "Should cheating on a test be automatic grounds for expulsion?"

- "How much should sports leagues be held accountable for player injuries and the long-term consequences of those injuries?"

Expository Essay

An expository essay is typically a short essay in which the writer explains an idea, issue, or theme , or discusses the history of a person, place, or idea.

This is typically a fact-forward essay with little argument or opinion one way or the other.

Example topics of an expository essay:

- "The History of the Philadelphia Liberty Bell"

- "The Reasons I Always Wanted to be a Doctor"

- "The Meaning Behind the Colloquialism ‘People in Glass Houses Shouldn't Throw Stones'"

Analytical Essay

An analytical essay seeks to delve into the deeper meaning of a text or work of art, or unpack a complicated idea . These kinds of essays closely interpret a source and look into its meaning by analyzing it at both a macro and micro level.

This type of analysis can be augmented by historical context or other expert or widely-regarded opinions on the subject, but is mainly supported directly through the original source (the piece or art or text being analyzed) .

Example topics of an analytical essay:

- "Victory Gin in Place of Water: The Symbolism Behind Gin as the Only Potable Substance in George Orwell's 1984"

- "Amarna Period Art: The Meaning Behind the Shift from Rigid to Fluid Poses"

- "Adultery During WWII, as Told Through a Series of Letters to and from Soldiers"

There are many different types of essay and, over time, you'll be able to master them all.

A Typical Argumentative Essay Assignment

The average argumentative essay is between three to five pages, and will require at least three or four separate sources with which to back your claims . As for the essay topic , you'll most often be asked to write an argumentative essay in an English class on a "general" topic of your choice, ranging the gamut from science, to history, to literature.

But while the topics of an argumentative essay can span several different fields, the structure of an argumentative essay is always the same: you must support a claim—a claim that can reasonably have multiple sides—using multiple sources and using a standard essay format (which we'll talk about later on).

This is why many argumentative essay topics begin with the word "should," as in:

- "Should all students be required to learn chemistry in high school?"

- "Should children be required to learn a second language?"

- "Should schools or governments be allowed to ban books?"

These topics all have at least two sides of the argument: Yes or no. And you must support the side you choose with evidence as to why your side is the correct one.

But there are also plenty of other ways to frame an argumentative essay as well:

- "Does using social media do more to benefit or harm people?"

- "Does the legal status of artwork or its creators—graffiti and vandalism, pirated media, a creator who's in jail—have an impact on the art itself?"

- "Is or should anyone ever be ‘above the law?'"

Though these are worded differently than the first three, you're still essentially forced to pick between two sides of an issue: yes or no, for or against, benefit or detriment. Though your argument might not fall entirely into one side of the divide or another—for instance, you could claim that social media has positively impacted some aspects of modern life while being a detriment to others—your essay should still support one side of the argument above all. Your final stance would be that overall , social media is beneficial or overall , social media is harmful.

If your argument is one that is mostly text-based or backed by a single source (e.g., "How does Salinger show that Holden Caulfield is an unreliable narrator?" or "Does Gatsby personify the American Dream?"), then it's an analytical essay, rather than an argumentative essay. An argumentative essay will always be focused on more general topics so that you can use multiple sources to back up your claims.

Good Argumentative Essay Topics

So you know the basic idea behind an argumentative essay, but what topic should you write about?

Again, almost always, you'll be asked to write an argumentative essay on a free topic of your choice, or you'll be asked to select between a few given topics . If you're given complete free reign of topics, then it'll be up to you to find an essay topic that no only appeals to you, but that you can turn into an A+ argumentative essay.

What makes a "good" argumentative essay topic depends on both the subject matter and your personal interest —it can be hard to give your best effort on something that bores you to tears! But it can also be near impossible to write an argumentative essay on a topic that has no room for debate.

As we said earlier, a good argumentative essay topic will be one that has the potential to reasonably go in at least two directions—for or against, yes or no, and why . For example, it's pretty hard to write an argumentative essay on whether or not people should be allowed to murder one another—not a whole lot of debate there for most people!—but writing an essay for or against the death penalty has a lot more wiggle room for evidence and argument.

A good topic is also one that can be substantiated through hard evidence and relevant sources . So be sure to pick a topic that other people have studied (or at least studied elements of) so that you can use their data in your argument. For example, if you're arguing that it should be mandatory for all middle school children to play a sport, you might have to apply smaller scientific data points to the larger picture you're trying to justify. There are probably several studies you could cite on the benefits of physical activity and the positive effect structure and teamwork has on young minds, but there's probably no study you could use where a group of scientists put all middle-schoolers in one jurisdiction into a mandatory sports program (since that's probably never happened). So long as your evidence is relevant to your point and you can extrapolate from it to form a larger whole, you can use it as a part of your resource material.

And if you need ideas on where to get started, or just want to see sample argumentative essay topics, then check out these links for hundreds of potential argumentative essay topics.

101 Persuasive (or Argumentative) Essay and Speech Topics

301 Prompts for Argumentative Writing

Top 50 Ideas for Argumentative/Persuasive Essay Writing

[Note: some of these say "persuasive essay topics," but just remember that the same topic can often be used for both a persuasive essay and an argumentative essay; the difference is in your writing style and the evidence you use to support your claims.]

KO! Find that one argumentative essay topic you can absolutely conquer.

Argumentative Essay Format

Argumentative Essays are composed of four main elements:

- A position (your argument)

- Your reasons

- Supporting evidence for those reasons (from reliable sources)

- Counterargument(s) (possible opposing arguments and reasons why those arguments are incorrect)

If you're familiar with essay writing in general, then you're also probably familiar with the five paragraph essay structure . This structure is a simple tool to show how one outlines an essay and breaks it down into its component parts, although it can be expanded into as many paragraphs as you want beyond the core five.

The standard argumentative essay is often 3-5 pages, which will usually mean a lot more than five paragraphs, but your overall structure will look the same as a much shorter essay.

An argumentative essay at its simplest structure will look like:

Paragraph 1: Intro

- Set up the story/problem/issue

- Thesis/claim

Paragraph 2: Support

- Reason #1 claim is correct

- Supporting evidence with sources

Paragraph 3: Support

- Reason #2 claim is correct

Paragraph 4: Counterargument

- Explanation of argument for the other side

- Refutation of opposing argument with supporting evidence

Paragraph 5: Conclusion

- Re-state claim

- Sum up reasons and support of claim from the essay to prove claim is correct

Now let's unpack each of these paragraph types to see how they work (with examples!), what goes into them, and why.

Paragraph 1—Set Up and Claim

Your first task is to introduce the reader to the topic at hand so they'll be prepared for your claim. Give a little background information, set the scene, and give the reader some stakes so that they care about the issue you're going to discuss.

Next, you absolutely must have a position on an argument and make that position clear to the readers. It's not an argumentative essay unless you're arguing for a specific claim, and this claim will be your thesis statement.

Your thesis CANNOT be a mere statement of fact (e.g., "Washington DC is the capital of the United States"). Your thesis must instead be an opinion which can be backed up with evidence and has the potential to be argued against (e.g., "New York should be the capital of the United States").

Paragraphs 2 and 3—Your Evidence

These are your body paragraphs in which you give the reasons why your argument is the best one and back up this reasoning with concrete evidence .

The argument supporting the thesis of an argumentative essay should be one that can be supported by facts and evidence, rather than personal opinion or cultural or religious mores.

For example, if you're arguing that New York should be the new capital of the US, you would have to back up that fact by discussing the factual contrasts between New York and DC in terms of location, population, revenue, and laws. You would then have to talk about the precedents for what makes for a good capital city and why New York fits the bill more than DC does.

Your argument can't simply be that a lot of people think New York is the best city ever and that you agree.

In addition to using concrete evidence, you always want to keep the tone of your essay passionate, but impersonal . Even though you're writing your argument from a single opinion, don't use first person language—"I think," "I feel," "I believe,"—to present your claims. Doing so is repetitive, since by writing the essay you're already telling the audience what you feel, and using first person language weakens your writing voice.

For example,

"I think that Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

"Washington DC is no longer suited to be the capital city of the United States."

The second statement sounds far stronger and more analytical.

Paragraph 4—Argument for the Other Side and Refutation

Even without a counter argument, you can make a pretty persuasive claim, but a counterargument will round out your essay into one that is much more persuasive and substantial.

By anticipating an argument against your claim and taking the initiative to counter it, you're allowing yourself to get ahead of the game. This way, you show that you've given great thought to all sides of the issue before choosing your position, and you demonstrate in multiple ways how yours is the more reasoned and supported side.

Paragraph 5—Conclusion

This paragraph is where you re-state your argument and summarize why it's the best claim.

Briefly touch on your supporting evidence and voila! A finished argumentative essay.

Your essay should have just as awesome a skeleton as this plesiosaur does. (In other words: a ridiculously awesome skeleton)

Argumentative Essay Example: 5-Paragraph Style

It always helps to have an example to learn from. I've written a full 5-paragraph argumentative essay here. Look at how I state my thesis in paragraph 1, give supporting evidence in paragraphs 2 and 3, address a counterargument in paragraph 4, and conclude in paragraph 5.

Topic: Is it possible to maintain conflicting loyalties?

Paragraph 1

It is almost impossible to go through life without encountering a situation where your loyalties to different people or causes come into conflict with each other. Maybe you have a loving relationship with your sister, but she disagrees with your decision to join the army, or you find yourself torn between your cultural beliefs and your scientific ones. These conflicting loyalties can often be maintained for a time, but as examples from both history and psychological theory illustrate, sooner or later, people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever.

The first two sentences set the scene and give some hypothetical examples and stakes for the reader to care about.

The third sentence finishes off the intro with the thesis statement, making very clear how the author stands on the issue ("people have to make a choice between competing loyalties, as no one can maintain a conflicting loyalty or belief system forever." )

Paragraphs 2 and 3

Psychological theory states that human beings are not equipped to maintain conflicting loyalties indefinitely and that attempting to do so leads to a state called "cognitive dissonance." Cognitive dissonance theory is the psychological idea that people undergo tremendous mental stress or anxiety when holding contradictory beliefs, values, or loyalties (Festinger, 1957). Even if human beings initially hold a conflicting loyalty, they will do their best to find a mental equilibrium by making a choice between those loyalties—stay stalwart to a belief system or change their beliefs. One of the earliest formal examples of cognitive dissonance theory comes from Leon Festinger's When Prophesy Fails . Members of an apocalyptic cult are told that the end of the world will occur on a specific date and that they alone will be spared the Earth's destruction. When that day comes and goes with no apocalypse, the cult members face a cognitive dissonance between what they see and what they've been led to believe (Festinger, 1956). Some choose to believe that the cult's beliefs are still correct, but that the Earth was simply spared from destruction by mercy, while others choose to believe that they were lied to and that the cult was fraudulent all along. Both beliefs cannot be correct at the same time, and so the cult members are forced to make their choice.

But even when conflicting loyalties can lead to potentially physical, rather than just mental, consequences, people will always make a choice to fall on one side or other of a dividing line. Take, for instance, Nicolaus Copernicus, a man born and raised in Catholic Poland (and educated in Catholic Italy). Though the Catholic church dictated specific scientific teachings, Copernicus' loyalty to his own observations and scientific evidence won out over his loyalty to his country's government and belief system. When he published his heliocentric model of the solar system--in opposition to the geocentric model that had been widely accepted for hundreds of years (Hannam, 2011)-- Copernicus was making a choice between his loyalties. In an attempt t o maintain his fealty both to the established system and to what he believed, h e sat on his findings for a number of years (Fantoli, 1994). But, ultimately, Copernicus made the choice to side with his beliefs and observations above all and published his work for the world to see (even though, in doing so, he risked both his reputation and personal freedoms).

These two paragraphs provide the reasons why the author supports the main argument and uses substantiated sources to back those reasons.

The paragraph on cognitive dissonance theory gives both broad supporting evidence and more narrow, detailed supporting evidence to show why the thesis statement is correct not just anecdotally but also scientifically and psychologically. First, we see why people in general have a difficult time accepting conflicting loyalties and desires and then how this applies to individuals through the example of the cult members from the Dr. Festinger's research.

The next paragraph continues to use more detailed examples from history to provide further evidence of why the thesis that people cannot indefinitely maintain conflicting loyalties is true.

Paragraph 4

Some will claim that it is possible to maintain conflicting beliefs or loyalties permanently, but this is often more a matter of people deluding themselves and still making a choice for one side or the other, rather than truly maintaining loyalty to both sides equally. For example, Lancelot du Lac typifies a person who claims to maintain a balanced loyalty between to two parties, but his attempt to do so fails (as all attempts to permanently maintain conflicting loyalties must). Lancelot tells himself and others that he is equally devoted to both King Arthur and his court and to being Queen Guinevere's knight (Malory, 2008). But he can neither be in two places at once to protect both the king and queen, nor can he help but let his romantic feelings for the queen to interfere with his duties to the king and the kingdom. Ultimately, he and Queen Guinevere give into their feelings for one another and Lancelot—though he denies it—chooses his loyalty to her over his loyalty to Arthur. This decision plunges the kingdom into a civil war, ages Lancelot prematurely, and ultimately leads to Camelot's ruin (Raabe, 1987). Though Lancelot claimed to have been loyal to both the king and the queen, this loyalty was ultimately in conflict, and he could not maintain it.

Here we have the acknowledgement of a potential counter-argument and the evidence as to why it isn't true.

The argument is that some people (or literary characters) have asserted that they give equal weight to their conflicting loyalties. The refutation is that, though some may claim to be able to maintain conflicting loyalties, they're either lying to others or deceiving themselves. The paragraph shows why this is true by providing an example of this in action.

Paragraph 5

Whether it be through literature or history, time and time again, people demonstrate the challenges of trying to manage conflicting loyalties and the inevitable consequences of doing so. Though belief systems are malleable and will often change over time, it is not possible to maintain two mutually exclusive loyalties or beliefs at once. In the end, people always make a choice, and loyalty for one party or one side of an issue will always trump loyalty to the other.

The concluding paragraph summarizes the essay, touches on the evidence presented, and re-states the thesis statement.

How to Write an Argumentative Essay: 8 Steps

Writing the best argumentative essay is all about the preparation, so let's talk steps:

#1: Preliminary Research

If you have the option to pick your own argumentative essay topic (which you most likely will), then choose one or two topics you find the most intriguing or that you have a vested interest in and do some preliminary research on both sides of the debate.

Do an open internet search just to see what the general chatter is on the topic and what the research trends are.

Did your preliminary reading influence you to pick a side or change your side? Without diving into all the scholarly articles at length, do you believe there's enough evidence to support your claim? Have there been scientific studies? Experiments? Does a noted scholar in the field agree with you? If not, you may need to pick another topic or side of the argument to support.

#2: Pick Your Side and Form Your Thesis

Now's the time to pick the side of the argument you feel you can support the best and summarize your main point into your thesis statement.

Your thesis will be the basis of your entire essay, so make sure you know which side you're on, that you've stated it clearly, and that you stick by your argument throughout the entire essay .

#3: Heavy-Duty Research Time

You've taken a gander at what the internet at large has to say on your argument, but now's the time to actually read those sources and take notes.

Check scholarly journals online at Google Scholar , the Directory of Open Access Journals , or JStor . You can also search individual university or school libraries and websites to see what kinds of academic articles you can access for free. Keep track of your important quotes and page numbers and put them somewhere that's easy to find later.

And don't forget to check your school or local libraries as well!

#4: Outline

Follow the five-paragraph outline structure from the previous section.

Fill in your topic, your reasons, and your supporting evidence into each of the categories.

Before you begin to flesh out the essay, take a look at what you've got. Is your thesis statement in the first paragraph? Is it clear? Is your argument logical? Does your supporting evidence support your reasoning?

By outlining your essay, you streamline your process and take care of any logic gaps before you dive headfirst into the writing. This will save you a lot of grief later on if you need to change your sources or your structure, so don't get too trigger-happy and skip this step.

Now that you've laid out exactly what you'll need for your essay and where, it's time to fill in all the gaps by writing it out.

Take it one step at a time and expand your ideas into complete sentences and substantiated claims. It may feel daunting to turn an outline into a complete draft, but just remember that you've already laid out all the groundwork; now you're just filling in the gaps.

If you have the time before deadline, give yourself a day or two (or even just an hour!) away from your essay . Looking it over with fresh eyes will allow you to see errors, both minor and major, that you likely would have missed had you tried to edit when it was still raw.

Take a first pass over the entire essay and try your best to ignore any minor spelling or grammar mistakes—you're just looking at the big picture right now. Does it make sense as a whole? Did the essay succeed in making an argument and backing that argument up logically? (Do you feel persuaded?)

If not, go back and make notes so that you can fix it for your final draft.

Once you've made your revisions to the overall structure, mark all your small errors and grammar problems so you can fix them in the next draft.

#7: Final Draft

Use the notes you made on the rough draft and go in and hack and smooth away until you're satisfied with the final result.

A checklist for your final draft:

- Formatting is correct according to your teacher's standards

- No errors in spelling, grammar, and punctuation

- Essay is the right length and size for the assignment

- The argument is present, consistent, and concise

- Each reason is supported by relevant evidence

- The essay makes sense overall

#8: Celebrate!

Once you've brought that final draft to a perfect polish and turned in your assignment, you're done! Go you!

Be prepared and ♪ you'll never go hungry again ♪, *cough*, or struggle with your argumentative essay-writing again. (Walt Disney Studios)

Good Examples of Argumentative Essays Online

Theory is all well and good, but examples are key. Just to get you started on what a fully-fleshed out argumentative essay looks like, let's see some examples in action.

Check out these two argumentative essay examples on the use of landmines and freons (and note the excellent use of concrete sources to back up their arguments!).

The Use of Landmines

A Shattered Sky

The Take-Aways: Keys to Writing an Argumentative Essay

At first, writing an argumentative essay may seem like a monstrous hurdle to overcome, but with the proper preparation and understanding, you'll be able to knock yours out of the park.

Remember the differences between a persuasive essay and an argumentative one, make sure your thesis is clear, and double-check that your supporting evidence is both relevant to your point and well-sourced . Pick your topic, do your research, make your outline, and fill in the gaps. Before you know it, you'll have yourself an A+ argumentative essay there, my friend.

What's Next?

Now you know the ins and outs of an argumentative essay, but how comfortable are you writing in other styles? Learn more about the four writing styles and when it makes sense to use each .

Understand how to make an argument, but still having trouble organizing your thoughts? Check out our guide to three popular essay formats and choose which one is right for you.

Ready to make your case, but not sure what to write about? We've created a list of 50 potential argumentative essay topics to spark your imagination.

Courtney scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT in high school and went on to graduate from Stanford University with a degree in Cultural and Social Anthropology. She is passionate about bringing education and the tools to succeed to students from all backgrounds and walks of life, as she believes open education is one of the great societal equalizers. She has years of tutoring experience and writes creative works in her free time.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Are you seeking one-on-one college counseling and/or essay support? Limited spots are now available. Click here to learn more.

Argumentative Essay Examples & Analysis

July 20, 2023

Writing successful argumentative or persuasive essays is a sort of academic rite of passage: every student, at some point in their academic career, will have to do it. And not without reason—writing a good argumentative essay requires the ability to organize one’s thoughts, reason logically, and present evidence in support of claims. They even require empathy, as authors are forced to inhabit and then respond to viewpoints that run counter to their own. Here, we’ll look at some argumentative essay examples and analyze their strengths and weaknesses.

What is an argumentative essay?

Before we turn to those argumentative essay examples, let’s get precise about what an argumentative essay is. An argumentative essay is an essay that advances a central point, thesis, or claim using evidence and facts. In other words, argumentative essays are essays that argue on behalf of a particular viewpoint. The goal of an argumentative essay is to convince the reader that the essay’s core idea is correct.

Good argumentative essays rely on facts and evidence. Personal anecdotes, appeals to emotion , and opinions that aren’t grounded in evidence just won’t fly. Let’s say I wanted to write an essay arguing that cats are the best pets. It wouldn’t be enough to say that I love having a cat as a pet. That’s just my opinion. Nor would it be enough to cite my downstairs neighbor Claudia, who also has a cat and who also prefers cats to dogs. That’s just an anecdote.

For the essay to have a chance at succeeding, I’d have to use evidence to support my argument. Maybe there are studies that compare the cost of cat ownership to dog ownership and conclude that cat ownership is less expensive. Perhaps there’s medical data that shows that more people are allergic to dogs than they are to cats. And maybe there are surveys that show that cat owners are more satisfied with their pets than are dog owners. I have no idea if any of that is true. The point is that successful argumentative essays use evidence from credible sources to back up their points.

Argumentative essay structure

Important to note before we examine a few argumentative essay examples: most argumentative essays will follow a standard 5-paragraph format. This format entails an introductory paragraph that lays out the essay’s central claim. Next, there are three body paragraphs that each advance sub-claims and evidence to support the central claim. Lastly, there is a conclusion that summarizes the points made. That’s not to say that every good argumentative essay will adhere strictly to the 5-paragraph format. And there is plenty of room for flexibility and creativity within the 5-paragraph format. For example, a good argumentative essay that follows the 5-paragraph template will also generally include counterarguments and rebuttals.

Introduction Example

Now let’s move on to those argumentative essay examples, and examine in particular a couple of introductions. The first takes on a common argumentative essay topic —capital punishment.

The death penalty has long been a divisive issue in the United States. 24 states allow the death penalty, while the other 26 have either banned the death penalty outright or issued moratoriums halting the practice. Proponents of the death penalty argue that it’s an effective deterrent against crime. Time and time again, however, this argument has been shown to be false. Capital punishment does not deter crime. But not only that—the death penalty is irreversible, which allows our imperfect justice system no room for error. Finally, the application of the death penalty is racially biased—the population of death row is over 41% Black , despite Black Americans making up just 13% of the U.S. population. For all these reasons, the death penalty should be outlawed across the board in the United States.

Why this introduction works: First, it’s clear. It lays out the essay’s thesis: that the death penalty should be outlawed in the United States. It also names the sub-arguments the author is going to use to support the thesis: (1), capital punishment does not deter crime, (2), it’s irreversible, and (3), it’s a racially biased practice. In laying out these three points, the author is also laying out the structure of the essay to follow. Each of the body paragraphs will take on one of the three sub-arguments presented in the introduction.

Argumentative Essay Examples (Continued)

Something else I like about this introduction is that it acknowledges and then refutes a common counterargument—the idea that the death penalty is a crime deterrent. Notice also the flow of the first two sentences. The first flags the essay’s topic. But it also makes a claim—that the issue of capital punishment is politically divisive. The following sentence backs this claim up. Essentially half of the country allows the practice; the other half has banned it. This is a feature not just of solid introductions but of good argumentative essays in general—all the essay’s claims will be backed up with evidence.

How it could be improved: Okay, I know I just got through singing the praises of the first pair of sentences, but if I were really nitpicking, I might take issue with them. Why? The first sentence is a bit of a placeholder. It’s a platitude, a way for the author to get a foothold in the piece. The essay isn’t about how divisive the death penalty is; it’s about why it ought to be abolished. When it comes to writing an argumentative essay, I always like to err on the side of blunt. There’s nothing wrong with starting an argumentative essay with the main idea: Capital punishment is an immoral and ineffective form of punishment, and the practice should be abolished .

Let’s move on to another argumentative essay example. Here’s an introduction that deals with the effects of technology on the brain:

Much of the critical discussion around technology today revolves around social media. Critics argue that social media has cut us off from our fellow citizens, trapping us in “information silos” and contributing to political polarization. Social media also promotes unrealistic and unhealthy beauty standards, which can lead to anxiety and depression. What’s more, the social media apps themselves are designed to addict their users. These are all legitimate critiques of social media, and they ought to be taken seriously. But the problem of technology today goes deeper than social media. The internet itself is the problem. Whether it’s on our phones or our laptops, on a social media app, or doing a Google search, the internet promotes distracted thinking and superficial learning. The internet is, quite literally, rewiring our brains.

Why this introduction works: This introduction hooks the reader by tying a topical debate about social media to the essay’s main subject—the problem of the internet itself. The introduction makes it clear what the essay is going to be about; the sentence, “But the problem of technology…” signals to the reader that the main idea is coming. I like the clarity with which the main idea is stated, and, as in the previous introduction, the main idea sets up the essay to follow.

How it could be improved: I like how direct this introduction is, but it might be improved by being a little more specific. Without getting too technical, the introduction might tell the reader what it means to “promote distracted thinking and superficial learning.” It might also hint as to why these are good arguments. For example, are there neurological or psychological studies that back this claim up? A simple fix might be: Whether it’s on our phones or our laptops, on a social media app, or doing a Google search, countless studies have shown that the internet promotes distracted thinking and superficial learning . The body paragraphs would then elaborate on those points. And the last sentence, while catchy, is a bit vague.

Body Paragraph Example

Let’s stick with our essay on capital punishment and continue on to the first body paragraph.

Proponents of the death penalty have long claimed that the practice is an effective deterrent to crime. It might not be pretty, they say, but its deterrent effects prevent further crime. Therefore, its continued use is justified. The problem is that this is just not borne out in the data. There is simply no evidence that the death penalty deters crime more than other forms of punishment, like long prison sentences. States, where the death penalty is still carried out, do not have lower crime rates than states where the practice has been abolished. States that have abandoned the death penalty likewise show no increase in crime or murder rates.

Body Paragraph (Continued)

For example, the state of Louisiana, where the death penalty is legal, has a murder rate of 21.3 per 100,000 residents. In Iowa, where the death penalty was abolished in 1965, the murder rate is 3.2 per 100,000. In Kentucky the death penalty is legal and the murder rate is 9.6; in Michigan where it’s illegal, the murder rate is 8.7. The death penalty simply has no bearing on murder rates. If it did, we’d see markedly lower murder rates in states that maintain the practice. But that’s not the case. Capital punishment does not deter crime. Therefore, it should be abolished.

Why this paragraph works: This body paragraph is successful because it coheres with the main idea set out in the introduction. It supports the essay’s first sub-argument—that capital punishment does not deter crime—and in so doing, it supports the essay’s main idea—that capital punishment should be abolished. How does it do that? By appealing to the data. A nice feature of this paragraph is that it simultaneously debunks a common counterargument and advances the essay’s thesis. It also supplies a few direct examples (murder rates in states like Kentucky, Michigan, etc.) without getting too technical. Importantly, the last few sentences tie the data back to the main idea of the essay. It’s not enough to pepper your essay with statistics. A good argumentative essay will unpack the statistics, tell the reader why the statistics matter, and how they support or confirm the essay’s main idea.

How it could be improved: The author is missing one logical connection at the end of the paragraph. The author shows that capital punishment doesn’t deter crime, but then just jumps to their conclusion. They needed to establish a logical bridge to get from the sub-argument to the conclusion. That bridge might be: if the deterrent effect is being used as a justification to maintain the practice, but the deterrent effect doesn’t really exist, then , in the absence of some other justification, the death penalty should be abolished. The author almost got there, but just needed to make that one final logical connection.

Conclusion Example

Once we’ve supported each of our sub-arguments with a corresponding body paragraph, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

It might be nice to think that executing murderers prevents future murders from happening, that our justice system is infallible and no one is ever wrongly put to death, and that the application of the death penalty is free of bias. But as we have seen, each of those thoughts are just comforting fictions. The death penalty does not prevent future crime—if it did, we’d see higher crime rates in states that’ve done away with capital punishment. The death penalty is an irreversible punishment meted out by an imperfect justice system—as a result, wrongful executions are unavoidable. And the death penalty disproportionately affects people of color. The death penalty is an unjustifiable practice—both practically and morally. Therefore, the United States should do away with the practice and join the more than 85 world nations that have already done so.

Why this conclusion works: It concisely summarizes the points made throughout the essay. But notice that it’s not identical to the introduction. The conclusion makes it clear that our understanding of the issue has changed with the essay. It not only revisits the sub-arguments, it expounds upon them. And to put a bow on everything, it restates the thesis—this time, though, with a little more emotional oomph.

How it could be improved: I’d love to see a little more specificity with regard to the sub-arguments. Instead of just rehashing the second sub-argument—that wrongful executions are unavoidable—the author could’ve included a quick statistic to give the argument more weight. For example: The death penalty is an irreversible punishment meted out by an imperfect justice system—as a result, wrongful executions are unavoidable. Since 1973, at least 190 people have been put to death who were later found to be innocent.

An argumentative essay is a powerful way to convey one’s ideas. As an academic exercise, mastering the art of the argumentative essay requires students to hone their skills of critical thinking, rhetoric, and logical reasoning. The best argumentative essays communicate their ideas clearly and back up their claims with evidence.

- College Success

- High School Success

Dane Gebauer

Dane Gebauer is a writer and teacher living in Miami, FL. He received his MFA in fiction from Columbia University, and his writing has appeared in Complex Magazine and Sinking City Review .

- 2-Year Colleges

- Application Strategies

- Best Colleges by Major

- Best Colleges by State

- Big Picture

- Career & Personality Assessment

- College Essay

- College Search/Knowledge

- Costs & Financial Aid

- Data Visualizations

- Dental School Admissions

- Extracurricular Activities

- Graduate School Admissions

- High Schools

- Law School Admissions

- Medical School Admissions

- Navigating the Admissions Process

- Online Learning

- Private High School Spotlight

- Summer Program Spotlight

- Summer Programs

- Teacher Tools

- Test Prep Provider Spotlight

“Innovative and invaluable…use this book as your college lifeline.”

— Lynn O'Shaughnessy

Nationally Recognized College Expert

College Planning in Your Inbox

Join our information-packed monthly newsletter.

Sorry, we did not find any matching results.

We frequently add data and we're interested in what would be useful to people. If you have a specific recommendation, you can reach us at [email protected] .

We are in the process of adding data at the state and local level. Sign up on our mailing list here to be the first to know when it is available.

Search tips:

• Check your spelling

• Try other search terms

• Use fewer words

The price of college is rising faster than wages for people with degrees

Between 2000 and 2019, the price the average college student paid for tuition, fees, and room and board increased 59%.

Updated on Tue, May 18, 2021 by the USAFacts Team

How much does college cost?

The average college student paid $24,623 for tuition, fees, and room and board for a year of school in 2019, according to data from the National Center for Education Statistics . That is an increase of 59% compared to 2000, when the inflation-adjusted price was $15,485. Wages have not kept pace. Between 2000 and 2020, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports that inflation-adjusted median weekly earnings for people with a bachelor’s degree rose 5%.

Tuition for the average student across all types of institutions has risen faster than tuition for students at four-year or two-year colleges, where prices have increased 53% and 42%, respectively. Part of the rise in attendance cost is a shift towards four-year colleges.

The price the average college student pays for a year of school has risen 59% since 2000.

Four-year institutions are more expensive than two-year ones. The price of attending a year of courses at a two-year school was about 40% of attending a four-year one in 2019. More students attending four-year institutions rather than two-year schools would increase the price of college for the average person even if costs at both types of institutions remained stable.

The percentage of people with a college degree is growing across the board. But increases have been greatest for degrees that require four years or more of college, according to the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey (CPS) data on highest level of education earned. Between 2000 and 2020, the share of Americans with an associate degree increased by three percentage points, from 8% to 11%. The percentage of Americans with a bachelor’s degree rose twice as much, from 17% to 23%. The share of Americans with an advanced degree rose five percentage points, from 9% to 14%.

It is more common than ever for Americans to have a bachelor’s degree or higher.

Slow wage growth comes as bachelor’s degrees are becoming more common in non-professional occupations..

Professionals like scientists, engineers, and teachers continue to be the likeliest to have a bachelor’s degree or higher — at a rate of 80%, according to CPS data. That has changed little compared to 2000, when it was 79%.

Bachelor’s degrees are becoming more frequent in non-professional occupations.

The share of non-professional positions with a four-year degree or higher increased since 2000. The greatest percentage point increase in people with four-year degrees or more was for technicians, where the rate doubled from 18% to 36%. The rate for management-related positions like accountants, agents, and people working in personnel and HR rose over 17 percentage points, from about 54% to 71%. People working as police and firefighters, administrative support personnel, salespeople, and managers each became over 13 percentage points more likely to hold a four-year college degree. The likelihood of someone working in cleaning, food, childcare, or other services having a four-year degree or higher rose 10 percentage points to 17%.

People with at least a bachelor’s degree have the highest wages and more job security.

Wages have risen 5% for people with bachelor’s degrees and 5.5% for people with advanced degrees. While that lags behind the rise in tuition, it is higher than the 3% wage growth for people with a high school diploma or equivalent and the 0.1% growth for people with some college or an associate degree.

Wages for people with bachelor’s degrees have risen 5% since 2000, compared to 0.1% for people with some college or an associate degree.

Wage growth for people with bachelor’s degrees is less than the 14% increase in wages for people who never graduated high school. People with bachelor’s degrees still make double the median wages per week than those without a high school diploma.

People with bachelor’s degrees or higher also fared better at keeping jobs or getting new ones during the pandemic . The group’s total employment fell 6% in April 2020 and has almost returned to pre-pandemic job levels as of March. The number of people working remained down 7% for people with some college or an associate degree, 9% for high school graduates, and 10% for people without a high school diploma or equivalent.

People with bachelor’s degrees have almost recovered to pre-pandemic employment levels.

How cost-effective is a college degree.

Comparing tuition costs to wage earnings in 2019 dollars can give a sense of the financial benefits of a college degree. An employed person with a bachelor’s degree earned an average of $392 more a week compared to a person with some college or an associate degree in 2019. Those holding a bachelor’s degree earned $502 more per week than a person with a high school diploma.

A person who started school at a four-year institution in the fall of 2015 and graduated in the spring of 2019 would have spent on average about $111,547 on their education, adjusted for inflation. The average American with a bachelor’s degree would earn back the cost of their college education in additional earnings in about four and a quarter years of work with their starting wage compared to someone with a high school diploma. This does not include potential earnings lost by being a student rather than working for four years.

The cost of college for a 2000 graduate was $71,533 when inflation-adjusted to 2019 dollars. That person’s starting wage would average $690 more per week than a person with a high school diploma. Class of 2000 graduates’ starting wages would meet the cost of college in about two years, less than half the time of the class of 2019.

This analysis does not consider the impact of student loans on college students . For those holding student loans, the cost of monthly payments and the interest accrued is an additional financial impact of attending college. Student loan debt, both federal and otherwise, hits lower-income families the hardest. Among households with student loans in the bottom 20% of income earners in 2019, median debt was $15,000 — or 92% of their median income. The US reported $1.6 trillion in federal student loan debt in 2020, almost triple the amount of debt in 2007.

Read more about the state of education at The State of the Union in Numbers and get the data directly in your inbox by signing up for our newsletter.

Correction: A previous version of this piece mislabeled the year in the headline of the first chart as 2019 rather than 2000.

Data shown for rate of bachelor's degrees or higher among occupational groupings is based on the IPUMS-standardized variable OCC90LY. The professional specialty category includes engineers, math and computer scientists, natural scientists, health practitioners, therapists, teachers, librarians, social scientists, social, recreation, and religious workers, lawyers and judges, and writers, artists, entertainers, and athletes. For more information, see the link to the IPUMS CPS data.

Explore more of USAFacts

Related articles, which states have the highest and lowest adult literacy rates.

Virtual school, mask mandates and lost learning: COVID-19's impact on K-12 schools

How often do teacher strikes happen?

Who are the nation’s 4 million teachers?

Related Data

College enrollment

18.99 million

College enrollment rate

College graduation rate at two-year institutions, within three years of start

College graduation rate at four-year institutions, within six years of start

Data delivered to your inbox.

Keep up with the latest data and most popular content.

SIGN UP FOR THE NEWSLETTER

Lowering the cost of public college is essential and reasonable

February 9, 2022 Opinions Editor Opinion , Opinions , Opinions 1

Ethan Kuhstoss, Contributing Writer

That’s the average cost of public university tuition over a four year period. That number doesn’t account for housing, fees, student loan interest, textbooks and the many other expenses associated with attending college. When taking these costs into consideration, a bachelor’s degree can cost more than $400,000.

For the majority of students — primarily low-income students of color — salvaging these costs is simply not feasible, saddling young professionals with overwhelming debt.

To ensure that hard-working students can obtain higher education while affording basic needs, it is imperative to vastly reduce or eliminate the cost of public four-year universities before it is entirely unobtainable for lower-income Americans.

Over 60% of all college graduates receive their diplomas from public institutions according to the Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities. Despite the clear necessity of public colleges, a 2020 study from the College Board found that their exorbitant prices have caused the average graduate to saddle $27,000 in debt .

The National Center for Education Statistics revealed that, when adjusted for inflation, the annual cost to attend a public four-year institution has increased by over 148% since 1970 . However, the average household income has not kept pace; with an increase in income of only 48.6% , families today have a far more difficult time financing their childrens’ education than the previous generation.

Public colleges earn hundreds of millions of dollars every year from tuition and federal subsidies , yet fail to return their services in an affordable manner. In turn, the totality of student debt has passed $1.73 trillion .

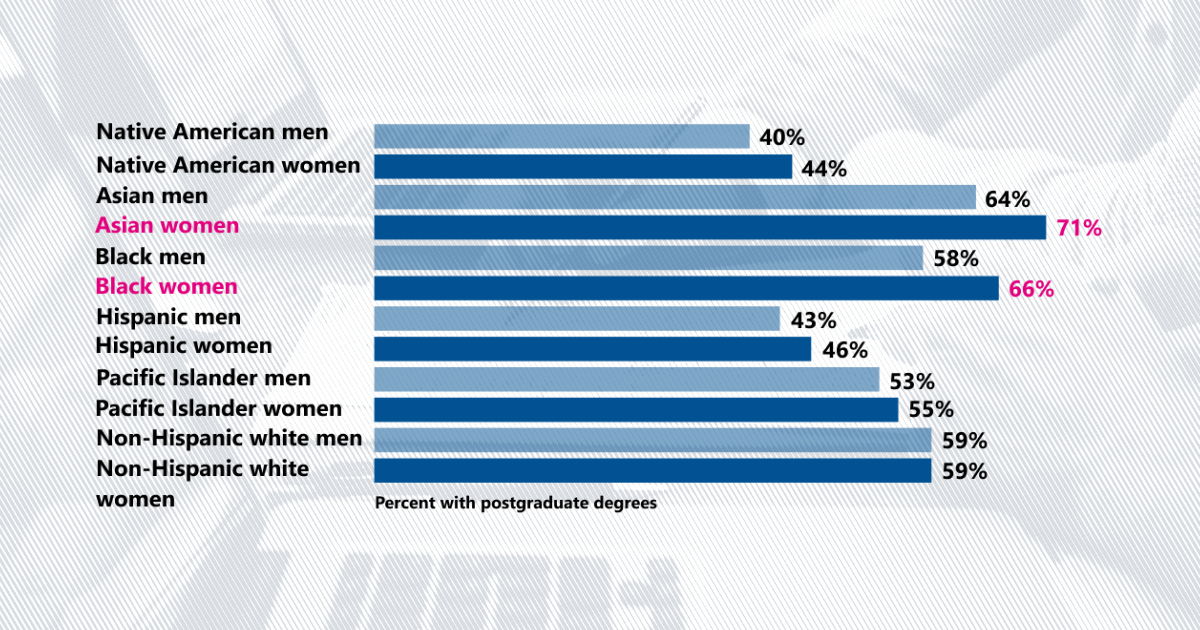

As American student loan debt totals surpass Canada’s GDP , the racial wealth gap also continues to widen. In 2020, Black Americans were the group most likely to be paying off student loan debt and to be behind on payments.

65% of Black students are financially independent and have the highest rate of full-time employment compared to other groups of students, according to a 2018 study from the United Negro College Fund. Moreover, this leaves them more vulnerable to the socio-economic effects of COVID-19, as job insecurity can make or break their ability to afford college.

It isn’t as simple as choosing a cheaper school, either. A study from the Institute for Higher Educational Policy revealed that lower-income students can only afford one to five percent of colleges; compounded with the fact that poor families have a shorter travel radius due to a lack of transportation, it’s clear why college is so unobtainable for so many.

With the infeasibility of higher education, it is no surprise that the United States’ college graduation rates are quickly falling behind other developed nations. In a 2012 OECD study , America scored 19th out of 28 countries.

One of the most common concerns about lowering the cost of public universities is that higher education would lose its value. Thus, American students display their willingness to “go the extra mile” by putting their financial security at risk, showing future employers that they are prepared to do whatever it takes to achieve their goals.

This is an inaccurate and biased system, however. Poorer students assume far more risk and stress by enrolling in college, yet the end result appears the same. Can we really call America a meritocracy if disadvantaged populations have to work harder to get to the same position as those born more privileged than them?

Higher education significantly improves personal income , leading to increased revenue for every level of government through taxation. Additional spending money also stimulates more economic activity. Throughout their lifetime, bachelor’s degree holders inject $278,000 more into local economies than those who only graduated high school.

There are a number of avenues the government can pursue to lower the cost of public higher education. In addition to improving economic activity, Sen. Bernie Sanders’, I-V.T., Tax on Wall Street Speculation Act illustrates how we can raise $2.4 trillion for educational funding in the next decade.

The act gains funding through the implementation of taxes under 1% on the trade of stocks, bonds and derivatives. Considering the price tag of public universities is $79 billion annually, Sanders’ plan would solely fund the price of tuition. This legislation is not unprecedented, either; financial transaction taxes (FTT) were imposed in America from 1914 to 1965 , demonstrating that such a plan is feasible.

The ethical, rational and feasible decision to lower the price of public universities has been delayed for far too long. The American government has a moral obligation to ensure equality for academic opportunities to disadvantaged populations.

Share this:

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- bernie sanders

- Ethan Kuhstoss

- higher education

- lower-income students

- National Center for Education Statistics

- public universities

- Student debt

- Tax on Wall Street Speculation Act

Affordable tuition fee gives you the opportunity to study what is really interesting to you. I chose nursing for myself and it’s really an amazing experience. This site https://tullisfarmschool.org/ made me understand a lot of important things about it

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copyright © 2024 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes

College prices aren’t skyrocketing—but they’re still too high for some

Subscribe to the center for economic security and opportunity newsletter, phillip levine phillip levine nonresident senior fellow - economic studies , center for economic security and opportunity @phil_wellesley.

April 24, 2023

- 21 min read

Discussions about the rising cost of college routinely miss the point . At four-year public and private institutions, the total cost of attendance almost tripled between 1979-80 and 2020-21, accounting for inflation. But only students from higher-income families pay that full cost, or “sticker price,” featured in headlines. Most students pay less because they receive financial aid in the form of grants (sometimes called scholarships). This means they pay a “net price” that is less —often much less—than the sticker price. Determining the net price for individual students is difficult, and tracking changes over time is even harder. But if we want to understand changes in college affordability, we need to track not only the highly visible sticker prices but also financial aid and net prices.

While the net price is what’s relevant for understanding college affordability, unfortunately it is not as easy as it should be to find reliable information on net prices and how they have changed over time. To help fill this void, I have been collecting better net price data for selected colleges.

These data confirm that lower- and middle-income students pay a net price that is typically much less than the sticker price. And net prices have actually been falling , on average, in recent years, not rising. But the data also show that the net price many lower-income students must pay is still too high at most institutions. This lack of college affordability for lower-income students, not the dramatic rise in sticker prices which only higher-income students pay, is what should capture our attention.

Net prices have actually been falling , on average, in recent years, not rising.

There are several steps that should be taken to address these problems. First, we need better information regarding college costs that are specific to individuals’ financial circumstances. The focus on sticker prices is perhaps understandable since institutions are required by law to report it annually. Net prices are specific to the individual, and generating that information is difficult. Finding better ways to report and track net price is sorely needed. Re-labelling the sticker price as the “maximum cost of attendance” is an easy first step to help clarify misperceptions regarding college pricing. To reduce the net price for lower-income students, increasing the maximum size of Pell Grants (the largest form of federal financial aid that does not need to be repaid) would go a long way towards fixing that problem.

Sticker prices are misleading and net prices are hard to find

A college education is one of the biggest expenses individuals face during their lives. College is not necessarily right for everyone, but the decision about whether and where to attend college should be based on accurate pricing information. What a student needs to know is not how much college costs in general but how much it will cost them. For most students the sticker price is misleading. Averages are not that informative either since the net price depends on individual circumstances.

Similarly, if policymakers, advocates, and commentators want to understand trends in college affordability over time for different types of students, they need to track net prices, not sticker prices. Almost a decade ago, I wrote about how difficult it is to determine how much colleges charge students with different financial circumstances. In terms of publicly available data, not much has changed since then. Figuring out how much a student can expect to pay to attend different colleges is still too difficult.

The federal government requires higher education institutions to post their “cost of attendance (COA),” an amount sometimes referred to as the “sticker price” that includes tuition, fees, room and board (soon to be relabeled as housing and food), travel, books, and other expenses. But most students pay less than that because they get financial aid. The “net price” is the sticker price minus the total grant aid a student receives (grant aid does not have to be paid back). Many students will qualify for federal student loans and the work-study program, which they can use to cover the net price they are expected to pay.

Any remaining amount not covered by grants, federal student loans, and work-study earnings must be paid for separately by students and their families. These remaining expenses are often referred to as “out-of-pocket” costs because they need to be paid by students and their families directly to the institution (i.e., by “writing a check,” back in the day before electronic payment systems). The funds to cover those payments could come from many sources, including savings or other sources of debt (including “Parent PLUS” loans), but out-of-pocket costs represent the additional burden on students and families that are not otherwise accounted for by the financial aid system.

Recognizing the need for more accurate information about how much students can expect to pay for college, the 2008 Higher Education Opportunity Act mandated that institutions provide a tool that students could use to estimate their net price based on their personal financial circumstances; these tools are known as “net price calculators.” The law also requires institutions to report statistics on the net price paid by their students, overall and separately for specific income ranges. 1 These data are reported on the College Scorecard .

Related Content

Phillip Levine, Jill Desjean

April 17, 2023

Sarah Turner

April 13, 2023

Adam Looney

September 26, 2022

Unfortunately, neither of these data sources has fully solved the problem. Net price calculators do not get the job done . They are often difficult to use and sometimes difficult even to find (which is consistent with my own experience using hundreds of net price calculators multiple times). Net price calculators are a well-intended step in the right direction, but they still have a long way to go. The net price data available at the College Scorecard also fall short. They can give a student some sense of what they might pay, but they do not fully incorporate individual circumstances and some of the data appear to be inaccurate or misleading. 2

Department of Education data show average net prices increase more slowly than sticker prices and have declined recently

Despite the limitations of the publicly available data, they do provide some useful information on trends in college pricing. For example, Figure 1 shows trends in the average COA and average net price (adjusted for inflation) since 2006-07, separately for public and non-profit private four-year institutions.

Between 2006-07 and 2019-20, COA increased by around 27% at both types of institutions, but declined by 7-8% in the few years after that. The recent decline occurred because colleges posted similar nominal COA increases as in the past, but inflation was higher. Overall, COA increased by almost 20% over those 16 years at both types of institutions.

But average net prices rose at a considerably more modest pace. Between 2006-07 and 2019-20, average net price increased by 13% and 7% at public and private four-year institutions, respectively. Those increases reversed in the post-COVID years. Overall, average net prices are largely unchanged, adjusted for inflation, compared to 2006-07.

But the average net price for all students reported here includes both those who receive financial aid and those who pay full price. Since those who pay full price faced higher prices over time, net prices among those who receive financial aid must have fallen. Without additional information, we cannot say more about how net price changed for different types of students, but the fact that net price is falling for students who receive financial aid is important and not consistent with public perception.

New data for tracking college pricing

Over the past decade, I have focused on finding ways to construct data that better communicate the level and trend in college costs for students with different financial circumstances. These data cover a more limited set of institutions and time periods than the Department of Education data described above, but they provide a more consistent and accurate picture of changes in net price over time.

I have taken two approaches. First, I draw on detailed data from institutions and the MyinTuition model I developed to track net prices for institutions who agree to participate. The second approach uses the net price calculators described above to track net prices at a random sample of institutions. In both cases, I track net prices for hypothetical dependent students with no siblings in college for three different family income levels (in 2022$): $40,000, $75,000, and $125,000. These incomes correspond roughly to the 25 th , 50 th , and 75 th percentile of the income distribution for families with college-aged children. 3 To estimate net prices, I also assume typical asset levels, adjusted for inflation, at each income level.

Consistent with the average net price data described above, these new data sources show declining net price for lower-income students in recent years. They also highlight ongoing problems with the levels of net prices for many students. Across the board, low- and moderate-income families pay net prices that are well below the posted sticker price; but in many cases, the net prices for these families are still too high. Notably, highly selective private colleges with large endowments have some of the highest sticker prices but the lowest net prices for low-income students.

Net prices at MyinTuition institutions have declined substantially

Almost a decade ago, I wrote about the work I did at Wellesley College to create a simplified tool to estimate college costs based on families’ basic financial characteristics. 4 That led to the creation of MyinTuition , which provides estimates of what a students’ financial aid award might look like based on data on current students whose families had similar financial characteristics. MyinTuition provides both a best estimate and a 90% confidence interval to convey the uncertainty about the estimate.

MyinTuition uses institution-specific data for each student receiving need-based financial aid to generate its predictions. These data are higher quality than that available from any public source, but they are only available for participating institutions. For this analysis, I focus on 14 of the 78 participating institutions for whom my data extends back to 2015-16. 5 They are all highly selective private non-profit colleges and universities that have large endowments (they would fall in the “private, non-profit, large endowment” category in the analysis described below).

Figure 2 shows trends in the net price for dependent students with no siblings in college at different levels of family income (assuming typical assets and adjusted for inflation). These data are based on MyinTuition’s best estimate of net price for these students in each year. Students from middle- and lower-income families now pay less to attend these institutions than they did seven years ago. The trend began before the COVID-19 pandemic and has accelerated since then. At the same time, sticker prices (i.e., COA) initially increased and then reversed, ending the period at roughly the same level as they started.

Figure 2 also demonstrates how the level of sticker price can skew perceptions of college costs. These institutions have among the highest sticker prices in the country—around $80,000 in 2022-2023. This amount is clearly unaffordable for all but high-income families. But those are the only students who are asked to pay that amount. Students with incomes around $40,000 (roughly the bottom quartile of the income distribution) pay a net price of $5,000 on average at these institutions. They could cover that amount through Federal student loans, work study wages, or perhaps a summer job, so families would have to pay little or nothing out-of-pocket in this situation (though the student would have to pay back any student loans with interest).