Brought to you by:

Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The Tubaίnas War

By: Dennis Guthery, David Gertner, Rosane Gertner

This case presents the challenges the Coca-Cola Company faced in Brazil. Not only was Coke up against its nemesis, Pepsi, it also had to compete with hundreds of local brands, many of which did not…

- Length: 18 page(s)

- Publication Date: Sep 27, 2004

- Discipline: Marketing

- Product #: TB0117-PDF-ENG

What's included:

- Teaching Note

- Educator Copy

$4.95 per student

degree granting course

$8.95 per student

non-degree granting course

Get access to this material, plus much more with a free Educator Account:

- Access to world-famous HBS cases

- Up to 60% off materials for your students

- Resources for teaching online

- Tips and reviews from other Educators

Already registered? Sign in

- Student Registration

- Non-Academic Registration

- Included Materials

This case presents the challenges the Coca-Cola Company faced in Brazil. Not only was Coke up against its nemesis, Pepsi, it also had to compete with hundreds of local brands, many of which did not pay taxes. These local brands were generically called tubaίnas. The case provides background information on the history of Cake in Brazil, trends in the Brazilian soft drink market, and on competition by Pepsi and the many local soft drink firms. In addition, Coke's strategies for competing are outlined. The student is asked to analyze the information presented in the case and to make recommendations to Coke on how to better compete in Brazil.

Learning Objectives

This case is appropriate for both undergrad and MBA international marketing classes. It is ideally suited for discussing international branding and strategies MNCs can use to compete with local brands. The teaching note includes the citation of three excellent articles focusing on global brands versus local brands. These three articles plus the case cover most issues relating to this topic and can be used in conjunction for a discussion covering at least two hours.

Sep 27, 2004

Discipline:

Geographies:

Industries:

Beverage industry

Thunderbird School of Global Management

TB0117-PDF-ENG

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

Coca-Cola Marketing Strategy: A 2024 Comprehensive Case Study

Introduced over a century ago, Coca-Cola remains the world’s most consumed soda, illustrating its unparalleled ability to engage and captivate consumers globally. This case study explores the marketing strategy of Coca-Cola that continues to make it the leading manufacturer and licensor of nonalcoholic beverages, offering a staggering 3,500 varieties across more than 200 countries.

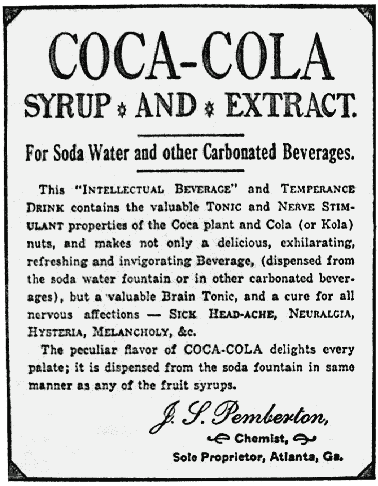

From Pharmacist's Elixir to Global Refreshment Drink

On May 8, 1886, Dr. John Pemberton created what is now known as Coca-Cola. Originally sold at a pharmacy in Atlanta as a medicinal elixir, Coca-Cola has transformed into a global refreshment enjoyed daily by millions.

What is Coca-Cola's Marketing Strategy?

The strategic marketing decisions made by Coca-Cola are largely responsible for its success. The company's approach includes comprehensive branding , widespread distribution, creative advertising, and innovative customer engagement tactics. Coca-Cola’s overarching vision continues to drive its global agenda, remaining focused on refreshing the world in mind, body, and spirit and making a difference to the people and communities it serves. This vision has enabled the company to maintain direction and momentum through periods of uncertainty.

Coca-Cola Target Audience

- Age : Targets youths (10–35 years) with celebrity endorsements and vibrant campaigns, while also catering to health-conscious older adults with products like Diet Coke and Coke Zero.

- Income and Family Size: Offers various packaging options across different price points to ensure affordability for students, middle-class families, and low-income groups.

- Geographical Segmentation: Tailors its formulas to suit regional tastes, such as sweeter versions in Asia, to resonate with local preferences.

- Gender: Differentiates offerings like Coca-Cola Light for women and Coke Zero for men, focusing on taste preferences linked to gender.

Advertising

From early advertisements in newspapers to groundbreaking campaigns like "I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke," Coca-Cola has always known the power of effective advertising. Each campaign not only promoted their product but also cemented Coca-Cola’s place in the cultural landscape. Coca-Cola’s advertising campaigns are designed to resonate on a global scale while maintaining local relevance. These strategies include:

- Creative Campaigns: Engaging and visually appealing ads that capture the essence of joy and refreshment.

- Emotional Branding : Utilizing regional languages and culturally relevant content to connect emotionally with consumers.

- Celebrity Partnerships: Collaborating with local and international celebrities to widen reach.

- Wide Coverage: Utilizing multiple channels, from traditional media to digital platforms.

- Engagement : Interactive campaigns and social media strategies to engage with a younger audience.

- Sponsorships : Long-standing partnerships with major events like the Olympics, FIFA World Cup, American Idol and popular TV shows enhancing brand visibility and consumer connection globally.

Coca-Cola has also embraced personalization in its past campaigns, from names on bottles to personalized marketing emails, enhancing consumer loyalty and personal connection with the brand.

1. "Share a Coke" Campaign

Launched initially in Australia in 2011, the "Share a Coke" campaign is one of the most celebrated and successful marketing strategies in Coca-Cola's history. The campaign was groundbreaking in its approach—replacing the iconic Coca-Cola logo on bottles with common first names. The idea was simple yet powerful: personalize the Coke experience to encourage sharing and create a personal connection with the product. Consumers could find bottles with their names or the names of friends and family, making it not just a purchase but a personalized social experience. The campaign heavily leveraged social media, encouraging people to share their Coca-Cola moments online with the hashtag #ShareaCoke, which amplified the campaign's reach exponentially. After its initial success in Australia, the campaign rolled out in over 80 countries with country-specific names and designs, each resonating with local audiences and cultural nuances.

2. "I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke" (Hilltop)

Originally aired in 1971, the "Hilltop" commercial for Coca-Cola, also known as "I'd Like to Buy the World a Coke," remains one of the most iconic advertisements in the history of television. Conceived by Bill Backer of McCann Erickson, the commercial featured a diverse group of young people from all over the world singing on a hilltop in Italy. The ad's simple yet profound message of hope and unity, expressed through the lyrics "I'd like to buy the world a home and furnish it with love," struck a chord during a time of political unrest and social change. The commercial became more than just an ad; it became a cultural icon, evoking feelings of peace and camaraderie at a global scale. The ad's popularity led to several remakes and re-releases over the decades, including a famous 1990 version featuring the original singers and their children, and a Super Bowl version in 2011.

3. "The Happiness Machine"

As part of its "Open Happiness" campaign, Coca-Cola launched "The Happiness Machine" video in 2010. The campaign featured a specially designed Coke vending machine placed in a college campus that dispensed not just bottles of Coke but surprising acts of "happiness" – from pizza and flowers to balloon animals. The video quickly went viral, thanks to its genuine, unscripted reactions and feel-good vibe. It amassed millions of views on YouTube, bringing widespread attention and goodwill toward the brand. This campaign emphasized Coca-Cola's focus on selling experiences and emotions associated with the brand, not just the product. It highlighted the brand’s commitment to spreading joy and happiness. The success of the "Happiness Machine" led to the creation of similar campaigns globally, harnessing the power of viral marketing and showing the brand's innovative approach to engaging with younger audiences.

Social Media and Digital Marketing

Coca-Cola has evolved its marketing strateg y from traditional mediums to a more integrated, multi-channel approach. The focus is now on building personal connections with consumers and leveraging digital platforms for targeted and engaging marketing campaigns. This shift has allowed Coca-Cola to maintain its relevance. Coca-Cola has embraced the digital age with robust online presence across platforms like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat. The brand leverages SEO , email marketing , content marketing , and video marketing to engage a broader audience effectively.

Coca-Cola Marketing Strategy

Coca-Cola employs a dual-channel marketing strategy :

- Personal Channels: Direct interaction with consumers to build personal connections.

- Non-Personal Channels: A mix of traditional and digital media, including newspapers, TV, social media, email, and outdoor advertising, to ensure widespread reach.

Coca-Cola’s Marketing Mix: The 4 Ps

- Product Strategy: Coca-Cola boasts an extensive portfolio of 500 products, positioned strategically within the market to maximize reach and profitability. Coca-Cola’s commitment to maintaining its original formula and ensuring product quality has fostered deep brand loyalty . Even when new recipes were introduced, such as New Coke, the public’s attachment to the original formula brought it swiftly back. To cater to diverse consumer tastes, Coca-Cola has expanded its product portfolio to include juices, teas, coffees, and other beverages. This diversification strategy helps the company penetrate different market segments.

- Pricing Strategy: Initially maintained a constant price for decades, it now employs a flexible pricing strategy to remain competitive without compromising perceived quality. Coca-Cola's pricing strategy is carefully crafted to remain competitive while ensuring profitability.

- Place Strategy: Operates a vast distribution network across six global regions, supported by an extensive supply chain involving bottling partners and distributors, ensuring global product availability.

- Promotion Strategy: Invests heavily in diverse advertising strategies to maintain brand visibility and consumer engagement across various platforms.

Coca-Cola's Growth Strategy

- Winning More Consumers : Expanding the consumer base through effective marketing and innovative product offerings.

- Gaining Market Share: Outperforming competitors by understanding consumer needs better and responding quickly.

- Maintaining Strong System Economics: Ensuring profitability and sustainability across the supply chain.

- Strengthening Impact Across Stakeholders: Building a positive influence on consumers, communities, and environments.

- Equipping for Future Success: Preparing the organization to meet future challenges through continuous learning and adaptation.

Additionally, sustainability is integral to Coca-Cola's growth strategy. The company has focused on reducing its environmental footprint, using resources more efficiently, and promoting recycling. These efforts are aligned with its mission to make a difference, ensuring that growth is sustainable over the long term.

These objectives serve as the north stars for Coca-Cola, guiding all strategic decisions and initiatives.

Brand Portfolio Optimization

The iconic Coca-Cola logo and the classic bottle design are instantly recognizable worldwide, making branding a cornerstone of their strategy. This section examines how consistent branding across various platforms plays a critical role in Coca-Cola's marketing . Keeping a uniform visual identity and engaging in significant sponsorships have allowed Coca-Cola to remain relevant and beloved by generations. In a significant move to optimize its brand portfolio , Coca-Cola reduced its brand count from 400 to 200 master brands. This strategic decision was aimed at focusing on those brands that align with and support the company's growth objectives. By doing so, Coca-Cola has ensured that it invests in brands with the highest potential for growth and profitability, balancing global, regional, and local brands to cover all drinking occasions.

Managing Missteps With Grace

Coca-Cola’s ability to handle marketing and business errors gracefully, such as the New Coke debacle, shows a brand well-versed in crisis management and responsive public relations.

Lessons for Marketers

- Brand Identity is Essential: A strong, consistent brand identity is vital for long-term success.

- Prioritize Product Quality : High product quality should always be a priority, supporting marketing efforts and building consumer trust.

- Strategic Pricing is Key: Effective pricing strategies can significantly impact brand perception and customer loyalty.

- Explore New Markets: Expanding into new markets can drive growth and help maintain relevance.

- Responsive PR Matters: Managing public relations actively and effectively can mitigate potential damages and boost brand image.

What Makes Coca-Cola’s Marketing Strategy So Successful?

Coca-Cola’s enduring success is attributed to its ability to adapt to consumer needs, maintain a strong emotional connection with customers, and continuously innovate its marketing strategies .

Coca-Cola's success story is a playbook for marketers aiming to build a lasting brand that not only survives but thrives through changing times. By understanding and implementing these strategies, other brands can aim to replicate Coca-Cola's enduring appeal.

Please fill out the form below if you have any advertising and partnership inquiries.

Consultation & Audit

Thirsty for More: Coca-Cola’s Shared Value Approach with Communities Across Brazil

The Coca-Cola Company is the world’s largest beverage company, with a portfolio of more than 500 sparkling and non-carbonated brands and an average of 1.9 billion servings a day. Sales of Coca-Cola products in Brazil currently represent seven percent of global volume, making Brazil the company’s fourth-largest market behind the U.S., Mexico, and China. Today, Coca-Cola Brazil has a leading presence in the Brazilian market. The company’s approach to engaging low-income markets contributes to its market position. In early 2009, the company sought to increase its presence and relevance in low-income areas. It became clear that “business as usual” approaches—expanding distribution channels or designing new marketing campaigns—were not enough. Coca-Cola needed to find a different way to deepen its relationship with consumers in these communities, recognizing the social and economic barriers to consumer access and retention. This realization helped jumpstart an innovative approach to business planning: Coca-Cola realized that it had to help solve a social problem to capture a significant business opportunity. From there, Coca-Cola designed and launched Coletivo Retail, an eight-week training program to empower unemployed youth living in low-income communities, such as favelas, and to help them find new economic opportunities.

Related Content

Creating Shared Value: Competitive Advantage through Social Impact

Centering Equity in Corporate Purpose – Webinar

Centering Equity in Corporate Purpose – Executive Summary

Privacy overview.

Fern Fort University

Coca-cola's marketing challenges in brazil: the tubai¯nas war change management analysis & solution, hbr change management solutions, global business case study | dennis guthery, david gertner, rosane gertner, case study description.

This is a Thunderbird Case Study.This case presents the challenges the Coca-Cola Company faced in Brazil. Not only was Coke up against its nemesis, Pepsi, it also had to compete with hundreds of local brands, many of which did not pay taxes. These local brands were generically called tubaI¯nas. The case provides background information on the history of Cake in Brazil, trends in the Brazilian soft drink market, and on competition by Pepsi and the many local soft drink firms. In addition, Coke's strategies for competing are outlined. The student is asked to analyze the information presented in the case and to make recommendations to Coke on how to better compete in Brazil.

Change Management, Global Business , Case Study Solution, Term Papers

Order a Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The TubaI¯nas War case study solution now

What is Change Management Definition & Process? Why transformation efforts fail? What are the Change Management Issues in Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The TubaI¯nas War case study?

According to John P. Kotter – Change Management efforts are the major initiatives an organization undertakes to either boost productivity, increase product quality, improve the organizational culture, or reverse the present downward spiral that the company is going through. Sooner or later every organization requires change management efforts because without reinventing itself organization tends to lose out in the competitive market environment. The competitors catch up with it in products and service delivery, disruptors take away the lucrative and niche market positioning, or management ends up sitting on its own laurels thus missing out on the new trends, opportunities and developments in the industry.

What are the John P. Kotter - 8 Steps of Change Management?

Eight Steps of Kotter's Change Management Execution are -

- 1. Establish a Sense of Urgency

- 2. Form a Powerful Guiding Coalition

- 3. Create a Vision

- 4. Communicate the Vision

- 5. Empower Others to Act on the Vision

- 6. Plan for and Create Short Term Wins

- 7. Consolidate Improvements and Produce More Change

- 8. Institutionalize New Approaches

Are Change Management efforts easy to implement? What are the challenges in implementing change management processes?

According to authorlist Change management efforts are absolutely essential for the surviving and thriving of the organization but they are also extremely difficult to implement. Some of the biggest obstacles in implementing change efforts are –

- Change efforts are often targeted at making fundamental aspects in the business – operations and culture. Change management disrupts are status quo thus face opposition from both within and outside the organization.

- Change efforts are often made by new leaders because they are chosen by board to do so. These leaders often have less trust among the workforce compare to the people with whom they were already working with over the years.

- Change management is often a lengthy, time consuming, and resource consuming process. Managements try to avoid them because they reflect negatively on the short term financial balance sheet of the organization.

- Change efforts create an environment of uncertainty in the organization that impacts not only the productivity in the organization but also the level of trust in the organization.

- Change management efforts are made when the organization is in dire need and have fewer resources. This creates silos protection mentality within the organization.

Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The TubaI¯nas War SWOT Analysis, SWOT Matrix, Weighted SWOT Case Study Solution & Analysis

How you can apply Change Management Principles to Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The TubaI¯nas War case study?

Leaders can implement Change Management efforts in the organization by following the “Eight Steps Method of Change Management” by John P. Kotter.

Step 1 - Establish a sense of urgency

What are areas that require urgent change management efforts in the “ Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The TubaI¯nas War “ case study. Some of the areas that require urgent changes are – organizing sales force to meet competitive realities, building new organizational structure to enter new markets or explore new opportunities. The leader needs to convince the managers that the status quo is far more dangerous than the change efforts.

Step 2 - Form a powerful guiding coalition

As mentioned earlier in the paper, most change efforts are undertaken by new management which has far less trust in the bank compare to the people with whom the organization staff has worked for long period of time. New leaders need to tap in the talent of the existing managers and integrate them in the change management efforts . This will for a powerful guiding coalition that not only understands the urgency of the situation but also has the trust of the employees in the organization. If the team able to explain at the grass roots level what went wrong, why organization need change, and what will be the outcomes of the change efforts then there will be a far more positive sentiment about change efforts among the rank and file.

Step 3 - Create a vision

The most critical role of the leader who is leading the change efforts is – creating and communicating a vision that can have a broader buy-in among employees throughout the organization. The vision should not only talk about broader objectives but also about how every little change can add up to the improvement in the overall organization.

Step 4 - Communicating the vision

Leaders need to use every vehicle to communicate the desired outcomes of the change efforts and how each employee impacted by it can contribute to achieve the desired change. Secondly the communication efforts need to answer a simple question for employees – “What it is in for the them”. If the vision doesn’t provide answer to this question then the change efforts are bound to fail because it won’t have buy-in from the required stakeholders of the organization.

Step 5 -Empower other to act on the vision

Once the vision is set and communicated, change management leadership should empower people at every level to take decisions regarding the change efforts. The empowerment should follow two key principles – it shouldn’t be too structured that it takes away improvisation capabilities of the managers who are working on the fronts. Secondly it shouldn’t be too loosely defined that people at the execution level can take it away from the desired vision and objectives.

Coca-Cola's Marketing Challenges in Brazil: The TubaI¯nas War PESTEL / PEST / STEP & Porter Five Forces Analysis

Step 6 - Plan for and create short term wins

Initially the change efforts will bring more disruption then positive change because it is transforming the status quo. For example new training to increase productivity initially will lead to decrease in level of current productivity because workers are learning new skills and way of doing things. It can demotivate the employees regarding change efforts. To overcome such scenarios the change management leadership should focus on short term wins within the long term transformation. They should carefully craft short term goals, reward employees for achieving short term wins, and provide a comprehensive understanding of how these short term wins fit into the overall vision and objectives of the change management efforts.

Step 7 - Consolidate improvements and produce more change

Short term wins lead to renewed enthusiasm among the employees to implement change efforts. Management should go ahead to put a framework where the improvements made so far are consolidated and more change efforts can be built on the top of the present change efforts.

Step 8 - Institutionalize new approaches

Once the improvements are consolidated, leadership needs to take steps to institutionalize the processes and changes that are made. It needs to stress how the change efforts have delivered success in the desired manner. It should highlight the connection between corporate success and new behaviour. Finally organization management needs to create organizational structure, leadership, and performance plans consistent with the new approach.

Is change management a process or event?

What many leaders and managers at the Nas Tubai fails to recognize is that – Change Management is a deliberate and detail oriented process rather than an event where the management declares that the changes it needs to make in the organization to thrive. Change management not only impact the operational processes of the organization but also the cultural and integral values of the organization.

MBA Admission help, MBA Assignment Help, MBA Case Study Help, Online Analytics Live Classes

Previous change management solution.

- Siam Canadian Foods Co. Ltd. Change Management Solution

- Crafting Winning Strategies in a Mature Market: The US Wine Industry in 2001 Change Management Solution

- Grupo Bimbo Change Management Solution

- United Cereal: Lora Brill's Eurobrand Challenge Change Management Solution

- Regarding NAFTA Change Management Solution

Next 5 Change Management Solution

- Perrier, Nestle, and the Agnellis Change Management Solution

- Rougemont Fruit Nectar: Distributing in China Change Management Solution

- The Octopus and the Generals: The United Fruit Company in Guatemala Change Management Solution

- Pepsi vs. Coke in Venezuela Change Management Solution

- Nestle's Globe Program (A): The Early Months Change Management Solution

Special Offers

Order custom Harvard Business Case Study Analysis & Solution. Starting just $19

Amazing Business Data Maps. Send your data or let us do the research. We make the greatest data maps.

We make beautiful, dynamic charts, heatmaps, co-relation plots, 3D plots & more.

Buy Professional PPT templates to impress your boss

Nobody get fired for buying our Business Reports Templates. They are just awesome.

- More Services

Feel free to drop us an email

- fernfortuniversity[@]gmail.com

- (000) 000-0000

Product details

In Brazil, Two Corporate Giants, a Drought and an Unexpected Partnership

Victor Moriyama/Getty

This article is adapted from AQ’s latest issue on the politics of water in Latin America | Leer en español

If there is a shorthand for fierce global corporate competition, Coke versus Pepsi would be it.

But then, there is water.

“In isolation, we wouldn’t reach results,” said Wanessa Scabora, a sustainability manager for Coca-Cola FEMSA in Brazil. “When it comes to water, we are partners.”

Their partnership came after São Paulo, Brazil’s megalopolis of 22 million people and the country’s industrial heart, hit a once-in-250-years drought in 2014 and 2015. Supplies in the city’s main reservoir, Cantareira, dwindled to just 3% of capacity. De facto emergency rationing left neighborhoods without water for days at a time. There was even talk among business leaders about long-term relocation of factories elsewhere — about 60,000 companies operating in the area were considered at risk.

The almost-too-late return of normal rainfall eventually ended the crisis. But in an era of extreme climate volatility, companies were unwilling to risk going through such a trauma again. Soon after, companies including Coca-Cola Femsa, Coca-Cola Brasil, PepsiCo and beer maker Ambev (AB InBev’s Brazilian arm) joined an initiative known as the Coalition of Cities for Water.

The Nature Conservancy (TNC) in Brazil launched the project in 2015 as part of the Latin American Water Funds Partnership, an initiative co-sponsored by the Inter-American Development Bank. It encompasses 24 water funds operating in Latin America, with resources invested in specific, localized projects that can either protect or restore local watersheds. The fund pays land owners and small farmers not to degrade areas surrounding water sources. It also works to reforest areas to increase water absorption, and restore riverbanks to reduce erosion and sediment going into rivers.

“We look for nature-based solutions,” said Samuel Barreto, head of water scarcity for TNC Brazil.

The alliance is supporting multiple initiatives in the PCJ basin (named for the three rivers that form it: Piracicaba, Capivari and Jundiaí) in São Paulo. The basin serves more than 5 million people, a large part of the state’s industrial park, and is an important component of the Cantareira reservoir system. The area grapples with multiple issues from riverbank erosion and sediment impacting the quality of the water and challenges to protecting springs inside private lands.

“What they are doing is very important,” said Pedro Roberto Jacobi, researcher and professor at the Institute of Energy and Environmental of the University of São Paulo. He said such programs are “a drop in the ocean,” however, and must be implemented at a much larger scale to have a major impact.

Indeed, the need is apparent — despite the fact both the city and the country get plentiful rainfall. “It seems crazy to talk about scarcity in Brazil,” said Richard Lee, head of sustainability for Ambev. Looking at a São Paulo city map, it does sound odd: two large dams, a major reservoir, three major rivers crossing the state capital — and another 200 streams running underground, hidden by the avenues and skyscrapers.

Except the region’s image of abundance doesn’t reflect reality, even in normal times. The city has seven times less water available per inhabitant than the annual minimum suggested by the UN — while housing 11% of Brazil’s GDP.

“We have the death penalty for rivers in Brazil,” said Barreto. During the 2014 crisis, São Paulo’s polluted rivers were useless to supply the resource, while the low levels of even dirty water in some stretches affected another business: grains and ethanol producers resorted to — much more expensive — trucks as the hydroway connecting farms to the Santos port was shut down for almost two years, because it was too low even for barges to navigate.

Water utility Sabesp, a publicly traded company (the state government owns 50.3% of the shares) has invested over $1 billion since 2015 in gray infrastructure to add new sources of water, install connections to create options when one system goes dry, and several other projects. But Jacobi said the problem in São Paulo is structural and not new. Besides “deforestation around reservoirs and occupation of watershed areas,” he said pollution is what significantly reduces the availability of usable water. Just one river in São Paulo, the Tietê, carries waste from 1,200 companies, according to the national water agency.

“It is frustrating that we can’t convince companies fast enough that business as usual is not possible anymore,” Jacobi told AQ .

Andrea Erickson-Quiroz, TNC’s global head of water security, has a suggestion for entrepreneurs. “You don’t need to listen to environmentalists,” she told AQ . “If you think water is something we can put off, listen to your peers in the food and beverage industry. They are moving.”

Many companies say they get it. PepsiCo Brazil said it has reduced the amount of water used in industrial processes by 25% since 2015, in what is becoming a trend in many sectors. As Andre Fourie, global director for water sustainability at AB InBev, put it: “Water is the only commodity that is cheap, scarce and wasted. Without it, we don’t have a business.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Related content.

Coca-Cola Marketing Case Study

From the star ‘Coca-Cola’ drink to Inca Kola in North and South America, Vita in Africa, and Thumbs up in India, The Coca-Cola Company owns a product portfolio of more than 3500 products . With the presence in more than 200 countries and the daily average servings to 1.9 billion people, Coca-Cola Company has been listed as the world’s most valuable brand with 94% of the world’s population recognizing the red and white Coca-Cola brand Logo . Moreover, 3.1% of all beverages consumed around the world are Coca-Cola products. All this because of its great marketing strategy which we’ll discuss in this article on Coca-Cola Marketing Strategy .

Coca-Cola –

- has a Market capitalization of $192.8 Billion (as of May 2016).

- had 53 years of consecutive annual dividend increases.

- with the revenue of over $44.29 billion, is not just a company but an ECONOMY.

The world knows and has tasted the coca cola products. In fact, out of the 55 billion servings of all kinds of beverages drunk each day (other than water), 1.7 billion are Coca-Cola trademarked/licensed drinks.

Marketing history

Market research in the beginning.

It all started 130 years ago, in 1886, when a Confederate colonel in the Civil War, John Pemberton, wanted to create his own version of coca wine (cola with alcohol and cocaine) and sent his nephew Lewis Newman to conduct a market research with the samples to a local pharmacy (Jacobs pharmacy). This wasn’t a new idea back then. The original idea of Coca wines was discovered by a Parisian chemist named Angelo Mariani.

Pemberton’s sample was sold for 5 cents a glass and the feedback of the customers was relayed to him by his nephew. Hence, by the end of the year, Pemberton was ready with a unique recipe that was tailored to the customers taste.

Marketing Strategy In The Beginning

Pemberton soon had to make it non-alcoholic because of the laws prevailing in Atlanta. Once the product was launched, it was marketed by Pemberton as a “Brain Tonic” and “temperance drink” (anti-alcohol), claiming that it cured headaches, anxiety, depression, indigestion, and addiction. Cocaine was removed from Coke in 1903.

The name and the original (current) Trademark logo was the idea of Pemberton’s accountant Frank Robinson, who designed the logo in his own writing. Not changing the logo till date is the best strategy adopted by Coca-cola.

Soon after the formula was sold to Asa G Candler (in 1889), who converted it into a soda drink, the real marketing began.

Candler was a marketer. He distributed thousands of complimentary coca-cola glass coupons, along with souvenir calendars, clocks, etc. all depicting the trademark and made sure that the coca cola trademark was visible everywhere .

He also painted the syrup barrels red to differentiate Coca-Cola from others.

Various syrup manufacturing plants outside Atlanta were opened and in 1895, Candler announced about Coca-Cola being drunk in every state & territory in the US.

The Idea Of The Bottle

During Candler’s era, Coca-Cola was sold only through soda fountains. But two innovative minds, Benjamin F. Thomas and Joseph B. Whitehead, secured from Candler exclusive rights (at just $1) for bottled coca cola sales.

But Coca-Cola was so famous in the US that it was subjected to imitations. Early advertising campaigns like “Demand the genuine” and “Accept no substitutes” helped the brand somewhat but there was a dire need to differentiate. Hence, in 1916, the unique bottle of Coca-Cola was designed by the Root Glass Company of Terre Haute, Indiana. The trademark bottle design hasn’t been changed until now.

Coca-Cola Worldwide

In 1919, Candler sold the company to Robert Woodruff whose aim was to make Coca-Cola available to anyone, anytime and anyplace. Bottling plants were set up all over the world & coca cola became first truly global brand.

Robert Woodruff had some other strategies too. He was focused on maintaining a standard of excellence as the company scaled. He wanted to position Coca-Cola as a premium product that was worthy of more attention than any of its competitors. And he succeeded in it. Coca-Cola grew rapidly throughout the world.

Coca-Cola Marketing Strategies

The worldwide popularity of Coca-Cola was a result of simple yet groundbreaking marketing strategies like –

Consistency

Consistency can be seen from the logo to the bottle design & the price of the drink (the price was 5 cents from 1886 to 1959). Coca-Cola has kept it simple with every slogan revolving around the two terms ‘Enjoy’ and ‘happiness’.

From the star bottle to the calendars, watches and other unrelated products, Candler started the trend to make Coca-Cola visible everywhere. The company has followed the same branding strategy till now. Coca-Cola is everywhere and hence has the world’s most renowned logo.

Positioning

Coca-Cola didn’t position itself as a product. It was and it is an ‘Experience’ of happiness and joy.

Franchise model

The bottling rights were sold to different local entrepreneurs , which is continued till now. Hence, Coca-cola isn’t one giant company, it’s a system of many small companies reporting to one giant company.

Personalization & Socialization

Unlike other big companies, Coca-Cola has maintained its positioning as a social brand. It talks to the users. Coca-Cola isn’t a company anymore. It’s a part of us now. With its iconic advertising ideas which include “I’d Like to Buy the World a Coke” & “Share a Coke”, it has maintained a special spot in the heart of its users.

Diversification

Coca-Cola, after marking its presence all over the world, took its first step towards diversifying its portfolio in 1960 by buying Minute Maid. It now operates in all but 2 countries worldwide with a portfolio of more than 3500 brands.

Coca-Cola Marketing Facts

- Logo & bottle design hasn’t changed since the start.

- During its first year, Coca-Cola sold an average of 9 drinks a day.

- Norman Rockwell created art for Coke ads.

- Coke has had a huge role in shaping our image of Santa Clause.

- In the 1980s, the company attempted a “Coke in the Morning” campaign to try to win over coffee drinkers.

- In 1923, the company began selling bottles in packages of six, which became common practice in the beverage industry.

- Recently, it was in the news that Verizon acquired Yahoo for around $5 billion which is more or less the same amount the Coca-Cola Company spends on its advertisements.

- The number of employees working with the Coca-Cola Company (123,200 to be exact) is more than the population of many countries.

Go On, Tell Us What You Think!

Did we miss something? Come on! Tell us what you think about Coca Cola Marketing Case Study in the comment section.

A startup consultant, digital marketer, traveller, and philomath. Aashish has worked with over 20 startups and successfully helped them ideate, raise money, and succeed. When not working, he can be found hiking, camping, and stargazing.

Related Posts:

Table of Contents

Coca-cola target audience , geographical segmentation , coca-cola marketing channels, coca-cola marketing strategy , coca-cola marketing strategy 2024: a case study.

Become an AI-powered Digital Marketing Expert

Coca-cola has colossal brand recognition as it targets every customer in the market. Its perfect marketing segmentation is a major reason behind its success.

- Firstly, the company targets young people between 10 and 35. They use celebrities in their advertisements to attract them and arrange campaigns in universities, schools, and colleges.

- They also target middle-aged and older adults who are diet conscious or diabetic by offering diet coke.

Income and Family Size

It introduces packaging and sizes priced at various levels to increase affordability and target students, middle class, and low-income families and individuals.

Coca-Cola sells its products globally and targets different cultures, customs, and climates. For instance, in America, it is liked by older people too. So, the company targets different segments. It also varies the change accordingly, like the Asian version is sweeter than other countries.

Coca-Cola targets individuals as per their gender. For example, Coca-Cola light is preferred by females, while coke zero and thumbs up are men's favorite due to their strong taste.

Become One of The Highest Paid Digital Marketer

Coca-Cola initially employed an undifferentiated targeting strategy. In recent times, it has started localizing its products for better acceptability. It incorporates two basic marketing channels : Personal and Non-personal.

Personal channels include direct communication with the audience. Non-personal marketing channels include both online and offline media, such as

- Promotion Campaigns

- PR activities

Social Media

Become an ai-powered business analyst.

A uniquely formulated Coca Cola marketing strategy is behind the company's international reach and widespread popularity. The strategy can be broken down into the following:

Product strategy

Coca-cola has approximately 500 products. Its soft drinks are offered globally, and its product strategy includes a marketing mix. Its beverages like Coca-Cola, Minute Maid, Diet Coke, Light, Coca-Cola Life, Coca-Cola Zero, Sprite Fanta, and more are sold in various sizes and packaging. They contribute a significant share and generate enormous profits.

Coca-Cola Products

Master SEO, SEM, Paid Social, Mobile Ads & More

Pricing Strategy

Coca-Cola's price remained fixed for approximately 73 years at five cents. The company had to make its pricing strategy flexible with the increased competition with competitors like Pepsi. It doesn't drop its price significantly, nor does it increase the price unreasonably, as this would lead to consumers doubting the product quality and switching to the alternative.

Place Strategy

Coca-cola has a vast distribution network. It has six operating regions: North America, Latin America, Africa, Europe, the Pacific, and Eurasia. The company's bottling partners manufacture, package, and ship to the agents. The agents then transport the products by road to the stockist, then to distributors, to retailers, and finally to the customer. Coca-Cola also has an extensive reverse supply chain network to collect leftover glass bottles for reuse. Thus, saving costs and resources.

Coca-Cola’s Global Marketing

Promotion Strategy

Coca-Cola employs different promotional and marketing strategies to survive the intense competition in the market. It spends up to $4 million annually to promote its brand , utilizing both traditional and international mediums for advertisements.

Classic Bottle, Font, and Logo

Coca-Cola organized a global contest to design the bottle. The contest winner used the cocoa pod's design, and the company used the same for promoting its shape and logo. Its logo, written in Spencerian script, differentiates it from its competitors. The way Coca-cola uses its logo in its marketing strategy ensures its imprint on consumers' minds.

Coca-Cola’s Gripping Advertisements

Localized Positioning

The recent 'Share a coke' campaign, launched in 2018 in almost fifty countries, has been quite a success. The images of celebrities of that region and messages according to the local language and culture of the area target the local market.

Coca-Cola Advertisement Featuring Celebrities

Sponsorships

The company is a well-recognized brand for its sponsorships, including American Idol, the NASCAR, Olympic Games, and many more. Since the 1928 Olympic Games, Coca-Cola has partnered on each event, helping athletes, officials and fans worldwide.

Coca-Cola as Official Olympics Partner

Learn About the Purdue Digital Marketing Bootcamp

With technological advancement, social media and online communication channels have become the most significant part of the Coca-Cola marketing strategy. It actively uses online digital marketing platforms like Facebook , Twitter, Instagram, YouTube, and Snapchat to post images, videos, and more. The Coca Cola marketing strategy primarily includes SEO , email marketing , content marketing , and video marketing .

Coca-Cola’s Instagram Posts

Become a millennial Digital Marketer in just 6 months. Enroll now for our IMT Ghaziabad Digital Marketing Program course in collaboration with Purdue University!

Become a Certified Marketing Expert in 8 Months

Good marketing strategies build customer loyalty and contribute to a huge market share. Learn how to boost your brand's market value with the Post Graduate Program in Digital Marketing . Upgrade your skill set and fast-track your career with insights from Purdue University experts.

Our Digital Marketing Courses Duration And Fees

Digital Marketing Courses typically range from a few weeks to several months, with fees varying based on program and institution.

Recommended Reads

Digital Marketing Career Guide: A Playbook to Becoming a Digital Marketing Specialist

A Case Study on Netflix Marketing Strategy

12 Powerful Instagram Marketing Strategies To Follow in 2021

Introductory Digital Marketing Guide

A Case Study on Apple Marketing Strategy

A Complete Guide on How to Do Social Media Marketing

Get Affiliated Certifications with Live Class programs

Post graduate program in digital marketing.

- Joint Purdue-Simplilearn Digital Marketer Certificate

- Become eligible to be part of the Purdue University Alumni Association

Post Graduate Program in Business Analysis

- Certificate from Simplilearn in collaboration with Purdue University

- PMP, PMI, PMBOK, CAPM, PgMP, PfMP, ACP, PBA, RMP, SP, and OPM3 are registered marks of the Project Management Institute, Inc.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Advance Articles

- Editor's Choice

- Supplements

- Open Access Articles

- Research Collections

- Review Collections

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- Self-Archiving Policy

- About Health Policy and Planning

- About the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine

- HPP at a glance

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

Introduction, soda industry development and political context, methodology, theoretical contribution, ethical approval, acknowledgements.

- < Previous

Coca-Cola’s political and policy influence in Mexico: understanding the role of institutions, interests and divided society

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Eduardo J Gómez, Coca-Cola’s political and policy influence in Mexico: understanding the role of institutions, interests and divided society, Health Policy and Planning , Volume 34, Issue 7, September 2019, Pages 520–528, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czz063

- Permissions Icon Permissions

In response to Mexico’s burgeoning industrial epidemics of obesity and type-2 diabetes, triggered in part by sugar-sweetened carbonated beverages’ ability to readily market their products and influence consumption, the government has responded through a variety of non-communicable disease (NCD) policies. Nevertheless, major industries, such as Coca-Cola, have been able to continuously obstruct the prioritization of those policies targeting the consumption, marketing and sale of their products. To better understand why this has occurred, this article introduces a political science agenda-setting framework and applies it to the case of Coca-Cola in Mexico. Devised from political science theory and subsequently applied to the case of Coca-Cola in Mexico, my framework, titled Institutions, Interests, and Industry Civic Influence (IPIC), emphasizes Coca-Cola’s access to institutions, supportive presidents and industry efforts to hamper civic mobilization and pressures for greater regulation of the soda industry. Methodologically, I employ qualitative single case study analysis, combining an analysis of 26 case study documents and seven in-depth stake-holder interviews. My proposed analytical framework helps to underscore the fact that Coca-Cola’s influence is not solely shaped by the corporation’s increased economic importance, but more importantly, its access to politicians, institutions and strategies to divide civil society. Additionally, my proposed framework provides several real-world policy recommendations for how governments and civil society can restructure their relationship with the soda industry, such as the government’s creation of laws prohibiting the industry’s ability to influence NCD policy and fund scientific research.

Political science theory can go far in helping to unravel and understand how major soda industries in Mexico, such as Coca-Cola, can continue to influence regulatory policy and scientific research.

In order to fully understand Coca-Cola’s policy and research influence in Mexico, we need to better understand the company’s historical institutional connections and capacity to divide civic mobilization.

The author’s proposed analytical political science framework can be applied to other emerging economies and help to explain why big soda industries continue to interfere in policy and research despite increased government support for obesity and type-2 diabetes prevention policies.

The product of global economic integration, foreign trade and economic growth, in recent years Mexico has seen one of the highest levels of per-capita consumption of sugary-beverage and fast foods in the Americas ( Luxton, 2015 ). While this situation has been underpinned by the emergence of a thriving middle-income class, it has also contributed to the growth of non-communicable diseases (NCDs). In Mexico, the top three NCD contributors to Disability-Adjusted Life Years are diabetes mellitus, ischaemic heart and chronic kidney disease ( Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, 2019 ). As Figure 1 illustrates, the number of deaths attributed to NCDs in Mexico increased between 2000 and 2010. Figure 2 shows that the population percentage of obese individuals has increased from 23.3% in 2005 to 28.3% in 2015, while the percentage of type-2 diabetes rose from 10.1% in 2005 to 11.2% in 2014.

Mexico: NCD Deaths (diabetes, cardiovascular, chronic obstructive pulmonary; reported deaths). Source : WHO and Global Health Observatory (2019) .

Mexico: Prevalence of Obesity, Diabetes, and Raised Blood Pressure (age standardized, percentage). Source : WHO and Global Health Observatory, 2019 .

This study is motivated by two primary research questions. First, since the beginning of the president Vincente Fox administration (2000–2006) to the present day, why has the government been repeatedly incapable of limiting the ability of Mexico’s largest soda industry, Coca-Cola, to obstruct government efforts to prioritize NCD prevention policies to discourage the consumption, marketing and sale of their products? This conundrum has contributed to the emergence of Mexico’s ‘industrial epidemics’ ( Hastings, 2012 ): e.g. obesity and type-2 diabetes, facilitated by Coca-Cola’s ability to easily market and sell its products. Second, to what extent can political science theory be used to develop an analytical framework addressing this first empirical question while providing a useful tool for policy-makers and civil society?

In answering these questions, this article submits an analytical framework titled Institutions, Political Interests, and Industry Civic Influence (IPIC). The IPIC framework was devised from several political science theories and subsequently applied and tested with the case of Coca-Cola in Mexico. IPIC provides an in-depth analysis of the actors and incentives shaping Mexico’s policy agenda-setting in the area of NCD prevention, such as policies seeking to reduce soda consumption (e.g. soda taxes), marketing and sales regulation. Through the application of this framework, it is argued that constraints in limiting Coca-Cola’s agenda-setting influence are attributed to three primary factors: first, the ability of industry lobbyists to meet with legislative members, taking advantage of pre-existing historic institutions and ties with policy-makers within government; second, the presidents’ pre-existing personal ties with Coca-Cola and interests in benefiting from this company’s ongoing success; and finally, the presence of what this article refers to as a ‘conflictual civil societal response,’ with Coca-Cola-supported researchers/activists vs public health advocates divided over the relationship between these products and NCDs and what prevention policies should look like, in turn hampering civil society’s ability to mobilize and limit Coca-Cola’s agenda-setting influence.

Mexico’s soda industry quickly emerged during the 1980s and 1990s, when the economy began to liberalize. The passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994 facilitated foreign direct investment from the USA and the expansion of Mexico’s soda industry ( Lopez and Jacobs, 2018 ). As Figures 3 and 4 illustrate, this industry continues to see an increase in sales and production. Today, the production and sales of soda are dominated by two companies that have approximately 85% of the market share: Coca-Cola (70%) and Pepsi-Co (15%) ( Lutzenkirchen, 2018 ), followed by Ajemex, Sociedad Cooperativa Trabajadores de Pascual, Jarocito and Mister Q ( Cortes, 2009 ). Coca-Cola FEMSA is the largest producer of sodas ( Lutzenkirchen, 2018 ). Sales continue to be dominated by Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Co, followed by Grupo Peñatfiel, Ajemex, and Sociedad Cooperativa Trabajadores de Pascual ( Cortes, 2009 ). Coca-Cola essentially dominates the market and presents a formidable political and economic force.

Mexico: Soft Drink Sales (US$ million). Source : Statista (2019) .

Mexico: Soft Drink Production (in millions of litres). Source : Statista (2019) .

Mexico’s political and policy-making context also facilitates Coca-Cola’s influence. Historically, the president wields considerable policy-making powers through legislative veto authority and informally as head of the governing political party (historically the PRI, Partido Revolucionaro Institutional), enjoying, until recently, majority representation in the congress, while leading the corporatist political agreement between the governing party, business and labour sectors ( Peschard and Rioff, 2005 ). The president’s ability to appoint and dismiss federal agency directors has also sustained the president’s influence over policy agenda-setting ( Edmonds-Poli and Shirk, 2016 ). In this context, Coca-Cola has had a considerable amount of policy influence when supported by the president and political parties.

This study commenced in June 2018 and concluded in April 2019. When conducting research, this study employed a qualitative case study methodological approach. This approach entails several benefits, ranging from hypothesis-building, establishing causal mechanisms, internal validation of theories and providing rich contextual analysis ( Gerring, 2011 ). Following Gerring’s (2011) discussion of the benefits that case studies provide in establishing causal insight, the case of Mexico was selected in order to illustrate the potential effectiveness of the IPIC framework by engaging in a form of ‘pattern matching’, i.e. illustrating the presence of IPIC’s causal mechanisms in Mexico. The unit of analysis was restricted to the national government level and those actors involved in agenda-setting processes. The case of Mexico was chosen because of the author's experience living and conducting research there, the vast amount of published literature on Coca-Cola’s policy influence in Mexico, and because within the Americas, Mexico has one of the highest prevalence rates of obesity and diabetes—see Figures 5 and 6 . Coca-Cola was also chosen because it is the most popular soda consumed in the country ( Tyler, 2018 ).

Obesity in the U.S., Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, and Brazil (BMI >30, age-standardized estimates, %). Source : WHO and Global Health Observatory (2019) .

Diabetes in the US, Mexico, Chile, Argentina, Colombia, Brazil (raised fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/L, age-standardized estimates, %). Source : WHO and Global Health Observatory (2019) .

With respect to data, this study used qualitative and quantitative sources. Qualitative documents, such as journal articles, books, policy reports and news articles were obtained via Google’s online search engine with keyword search terms. Online library search engines, such as ArticleFirst, Web of Science and PubMed (considered the most thorough databases for finding social science and medicine articles), were also used. Book chapters and policy reports were obtained from colleagues in Mexico. When reviewing documents, a narrative review process was used: selecting materials based on several key search terms, without a specific selection criteria, followed by a summary and analysis of the literature ( Ferrari, 2015 ). A summary and analysis of the theoretical literature discussing industry’s NCD policy influence was done in order to understand alternative theoretical approaches to this topic and assess limitations of the existing literature, providing information which was then used to explain the IPIC framework’s significance. With regards to documents discussing the Mexican case study, the author looked for and used relevant empirical analytical statements about the politics and policy process both to inform the article’s descriptive analysis and to provide evidence of IPIC’s effectiveness. In order to avoid selection bias, documents were randomly obtained from different academic and non-academic sources. Finally, quantitative statistical data of epidemiological NCD trends and quality of life were obtained from the World Health Organization (WHO) and used to provide a description of Mexico’s burden of disease.

Qualitative data were also obtained from stakeholder interviews in Mexico, with ethical review. Seven interviewees were selected due to their presence in Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), academia and government, chosen for their empirical knowledge and policy experience, not their personal views (see Table 1 ). Snow-balling procedures were used to find additional interviewees. Interviews were conducted for 30 min each, via Skype and WhatsApp communication, from mid- to late-April 2019. Formal verbal consent was obtained prior to the interviews. With the exception of two government officials, all gave consent to use their names, title and institutional affiliation. A total of eight interview questions were used, focusing on the president’s relationship with Coca-Cola, the latter’s partnership with government and civil society, and the importance of congressional/bureaucratic institutions for Coca-Cola’s lobbying activities. Interview data were analysed in a thematic fashion, without particular software usage, and referenced as supportive empirical evidence. Finally, these interview data were combined with the aforementioned qualitative documents in order to ‘triangulate’ the data, i.e. ensure that different types of data sources were in agreement over particular issues, thus avoiding selection bias in the usage of data.

This article introduces a political science analytical framework titled IPIC. Following an ‘analytical narratives’ ( Bates et al ., 1998 ) perspective, which applies political science theories to empirical case studies and uses the latter to reveal the effectiveness and limitations of theory, IPIC is an analytical framework that is used to better understand and explain the political and social factors shaping the policy agenda-setting process. This proposed framework is not intended to introduce a generalizable theory about the policy-making process, i.e. applicable to, and validated by, many case studies, but rather to use political science theories in order to better explain, not predict, agenda-setting processes.

The IPIC framework combines historical institutional (HI) theories emphasizing the importance of formal institutional design and historic interest group access to congressional and bureaucratic institutions (Institutions) ( Thelen, 1999 ), rational choice institutionalism in political elite decision-making (Political Interests) ( Ostrom, 2007 ), and industry’s effects on civic mobilization (Industry Civic Influence) ( Walker, 2009 ). As Figure 7 illustrates, these three pathways of the IPIC framework operate simultaneously, are isolated from each other, though eventually contributing to the same outcome—i.e. industry policy agenda-setting influence. Moreover, all three pathways are important and the presence of each is necessary to fully explain agenda-setting outcomes. Considering the political elite-driven agenda-setting process found in many developing nations, however, the Institutions and Political Interests pathways may be more causally significant than Industry Civic Influence—although the latter is needed to explain why agenda-setting continues to be elite-driven.

IPIC framework: institutions, political interests, and industry civic influence.

With respect to applying HI theories when addressing IPICs Institutions pathway, and building on the works of Immergut (1992) and Weir (1989 ), the application of the IPIC framework to Mexico reveals how Coca-Cola lobbyists’ historic access to legislators and policy-makers through congressional and bureaucratic institutions facilitated their subsequent ability to influence the NCD policy agenda. In Mexico, the congress periodically holds sub-committee meetings covering 52 policy issues, one of them being healthcare. When these sub-committee meetings on healthcare convene, soda and junk food industry representatives consistently go to these meetings and confront committee members prior to and after these meetings to discuss their company’s particular issues of concern. Moreover, these sub-committees routinely invite public testimony and are there to help oversee, conduct research and assist the congress in the fulfilment of its duties ( Mexican Congress, 1999 ).

Next, with respect to the IPIC’s Political Interests pathway, IPIC’s application to Mexico reveals how presidents with previous career histories in the soda industry and long-standing corporate allies facilitated the latter’s influence over NCD policy. Here, rational choice theory refers to politician’s strategies when maximizing their personal preferences in a context of institutional, organizational and social constraints ( Ostrom, 2007 ). In this article, this approach focuses on presidents and their effort to maximize their preferences in supporting the industry in exchange for their political support and assistance in achieving other policy objectives.

Finally, IPIC’s Industry Civic Influence pathway builds on the theoretical importance of industries’ impact on civic mobilization and pressures on the government for policy reform. Building on Walker (2009) , Lee and Romano (2013) and De Bakker et al . (2013) depiction of corporate efforts to mobilize citizens around causes that are aligned with the former’s interests, IPIC’s application to Mexico shows how industries can create a ‘conflictual civil society’ by supporting academic researchers and activists that could be working with other public health activists safeguarding the public’s health interests, in turn limiting the latter’s full potential to unify, mobilize and thwart industry’s ongoing agenda-setting influence.

Since the early-1990s, the sugary-beverage and fast food industries in Mexico exhibited a great deal of influence over NCD prevention policy. Despite civil societal actors working with the Secretariat of Health (SoH) to propose marketing regulations, a soda tax in 2008 and 2012, along with improved nutritional food diagrams ( Cecil, 2018 ), these policies were never adopted ( Rosenberg, 2015 ; Taylor and Jacobson, 2015 ; Processo , 2017 ). To help further reduce the consumption of sugary drinks, in 2008 the SoH introduced the Recomendaciones de Bebidas para una Vida Saludable (Recommendation of Drinks for a Healthy Life), which also failed to materialize ( Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria, 2013 ). Inter-ministerial efforts between the Secretariat of Education and Health in 2010 were also introduced in order to prevent the sale of soft drinks and other sweetened beverages in schools; and yet, after vehement opposition from the soda industry, mainly by vocalizing its opposition through votes in government-organized hearings, such as the Ministry of the Economy’s Federal Commission for Regulatory Improvement (COFEMER), this effort was eventually avoided ( Barquera et al ., 2013 ; Taylor and Jacobson, 2015 ).

Nevertheless, in 2013 the Enrique Peña Nieto (PRI, 2012–18) presidential administration succeeded in adopting a soda and beverage (SSB) tax, which entailed a tax of one peso per litre of soda. To facilitate its passage, this tax was introduced as part of a larger fiscal policy package focused on rejuvenating the economy, with proponents in civil society framing the endeavour on economic rather than healthcare grounds ( Bonilla-Chacín et al ., 2016 ; Baker et al ., 2017 ). This fiscal package was introduced to diversify government revenue (reducing its dependence on oil revenue) and entailed increasing taxes for high-income earners, limiting corporate deductions, creating a 10% tax on dividends, increasing taxes for the mining sector, and a soda and snack tax ( Valenzuela, 2016 ). In 2016, further efforts were made to increase the SSB tax; nevertheless, this proposal ultimately proved unsuccessful due to the Nieto administration’s decision not to modify government taxes for the remainder of his presidential term ( Bonilla-Chacín et al ., 2016 ).

Yet another successful soda industry strategy for undermining policy development has been its ongoing funding of supportive scientific research. For instance, Coca-Cola has worked with researchers, foundations, think-tanks and sponsored conferences to downplay the harm that increased sugar consumption has on health, questioning the scientific evidence behind these claims, and the effectiveness of prevention policies ( Taylor and Jacobson, 2015 ; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with Ana Larrañaga, April 15, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019; interview with Simon Barquera, April 16, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 29, 2019). A good example was a study by ITAM university economists, indirectly supported by Coca-Cola and other industries through the ConMéxico foundation, titled Taxing Calories in Mexico ( Aguilar et al ., 2015 ; Cecile, 2018). This study provided statistical evidence questioning the soda tax’s reduction in soda consumption. FunSalud (Mexican Health Foundation), arguably the most influential NGO when it comes to setting the SoH’s public health agenda, has for years also criticized efforts to limit the consumption of soda and processed foods. Funsalud has consistently taken this position because its directors and board have worked closely with Coca-Cola and other food industries, such as Nestlé ( Rosenberg, 2015 ); one excellent example was Dr Mercedes Juan López, who chaired Funsalud’s board prior to becoming Secretary of Health under President Peña Nieto ( Rosenberg, 2015 ). During her time at Funsalud, Dr López criticized the soda tax’s effectiveness, instead emphasizing the importance of exercise and moderation in soda consumption ( Rosenberg, 2015 ); this message comported with Coca-Cola’s position on the soda tax. FunSalud has also worked closely with Coca-Cola on childhood obesity projects ( Cecil, 2018 ). Finally, in 2006 Coca-Cola also partnered with the SoH to create the ‘Ponte 100’ programme, which promoted the habit of individual exercise rather than dietary changes ( Rosenberg, 2015 ; Ochoa, 2016 ; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 25 and 29, 2019).

Institutions

But what have been the institutional conditions facilitating Coca-Cola’s policy agenda-setting influence? Consistent with the IPIC framework, first, Institutions mattered: Mexico’s congressional committees, coupled with industries’ pre-existing ties with congressional legislators, facilitated Coca-Cola’s influence ( Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria , 2017 ; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019; interview with Ana Larrañaga, April 15, 2019; interview with Simon Barquera, April 16, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 25 and 29, 2019). Indeed, prior to the 2011 constitutional reforms regulating corporate access to congressional bodies, Coca-Cola lobbyists and supportive labour unions, such as the Cámara Nacional de la Industria de Azucar (CNIA), had repeated access to congressional members and committee meetings focused on NCD prevention policies. For instance, the CNIA initially lobbied against the soda tax because it would entail a substantial reduction in soda industry demand for sugar cane, with industries opting for the use of cheaper high-fructose corn syrup, potentially lowering sugar cane profits and employment ( Lutzenkirchen, 2018 ).

Within these congressional venues, lobbyists pressured legislative representatives into refraining from passing the aforementioned legislation on a sugar tax (in 2008, 2012), marketing and sales ( Calvillo and Peteranderl, 2018 ), made possible for several reasons. First was the provision of largesse and campaign contributions ( Rosenberg, 2015 ), with extensive private contributions deemed illegal according to the 2011 constitutional reforms ( O’Neil, 2013 ).

Coca-Cola representatives also had access to SoH committees focused on proposing NCD policies, such as the Observatorio Mexícano de Enfermedades No Transmisbles (OMENT, Mexican Observatory for NCDs). Since its inception through the 2013 National Strategy, OMENT has consistently ensured Coca-Cola’s (and other industry’s) representation, far exceeding civil society’s, and, in the process, heavily influenced policy proposals ( Lutzenkirchen, 2018 ; UK Health Forum, 2018 ; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with Ana Larrañaga, April 15, 2019). Coca-Cola corporate executives also had long-held personal ties and thus direct access to senior health officials, such as former SoH Secretary Mercedes Juan López, who often advocated on their behalf ( Cecil, 2018 ; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019). Other corporate strategies included using the media to question the relationship between the consumption of sodas and NCDs and opposing policies on the grounds of threats to individual liberty and happiness. One good example in Mexico has been the soda industry’s usage of large billboards promoting their message that exercise is joyful and that having a little sugar every day is natural and good for individuals ( Calvillo, 2017 ). Finally, some blamed the apathy and incompetence of congressional members for industries’ ability to repeatedly influence policy ( Lira, 2017 ).

Political interests

Following IPIC’s Political Interests pathway, which applies rational choice theories emphasizing the importance of presidents’ personal and political preferences in health policy-making, the Mexican presidency’s historic ties and vested interests in advancing Coca-Cola’s continued prosperity played an important role. For example, former President Vincente Fox had previously been a Coca-Cola executive and benefited from receiving campaign donations and advice from trusted corporate friends ( Cruz and Durán, 2017 ). In fact, before becoming president, as head of Coca-Cola’s Latin America operations, Fox was committed to expanding its sales and becoming a market leader ( Taylor, 2018 ). Consequently, Coca-Cola executives were highly influential throughout Fox’s administration ( Kilpatrick, 2015 ; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 25 and 29, 2019). Reporters and think tank experts claim that because of Fox’s pre-existing ties and reliance on Coca-Cola, this company had tremendous influence over health policy ( Rosenberg, 2015 ; interview with Yarishdy Mora, July 9, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019). In 2003, for example, under industry pressures, Fox ignored the idea of imposing a tax on sodas using sugar cane ingredients ( Juárez and Rio, 2017 ; interview with Luis Cruz, July 29, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019). Furthermore, the political connections that Fox created for Coca-Cola helped to deepen the company’s partnership with government officials after he left office (interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019; interview with Ana Larrañaga, April 15, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 25 and 29, 2019).

Subsequent presidents, such as Felip Calderón (PAN, 2006–2012), were also supportive of Coca-Cola’s activities, while Enrique Peña Nieto also supported Coca-Cola and Nestlé’s distribution of its products, mainly biscuits and fortified puddings, to support his anti-hunger programme ( Ochoa, 2014 ; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019). These industries have continued to have considerable influence within presidential administrations, while highlighting the fact that there is no sense of conflict of interest within government ( Rundall and Arana, 2013 ; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019).

Industry civic influence

Finally, IPIC’s Industry Civic Influence pathway, which applies theories underscoring industry’s manipulation of civic mobilization in the former’s favour ( Walker, 2009 ; Lee and Romano, 2013 ), also sheds light into the challenges of civic mobilization and resistance to Coca-Cola’s policy influence. Indeed, Mexico has exhibited what the author described as a ‘conflictual civil societal response,’ where influential segments of society, such as university academics and think-tanks, which have been approached by and work closely with Coca-Cola-funded foundations, such as ConMéxico, have repeatedly neglected to unify with NGOs, activists, and other academics representing the general public’s healthcare needs. Seeking funding, academics in the former camp, such as professors at the ITAM, El Colegio de México, and the Autonomous University of Nuevo Leon, have often supported Coca-Cola and other soda industries and the ConMéxico foundation, due to the latter’s willingness to finance research and facilitate publication ( Gertner and Rifkin, 2017 ; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019; interview with Ana Larrañaga, April 15, 2019; interview with Simon Barquera, April 16, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 25 and 29, 2019). Other NGOs, such as the Mexican Diabetes Federation, have also received funding from Coca-Cola and no longer engage in public advocacy campaigns, while often sponsoring conferences that emphasize scientific information supportive of Coca-Cola’s message emphasizing the importance of individual responsibility and exercise ( Asociación Mexicana de Diabetes , 2019 ; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019). Alternatively, NGOs, such as El Poder del Consumidor, and those advocating for the health and safety of Mexico’s citizens, such as Fundación Midete, ContraPESO, and researchers from the National Institute of Public Health, have created their own Alianza por la Salud Alimentaria . However, the Alianza has insufficient government and/or private sector support, with limited contributions from the Bloomberg Foundation ( Bonilla-Chacín et al ., 2016 ).

When compared with each other, however, academics and think-tanks working with food and beverage industries have had greater access to resources, funding for social media, and thus more political influence vs their rival public health proponents ( Barquera et al ., 2013 ). This has led to a lack of unity in civil society’s ability to exert ongoing pressure on the president and congress to limit Coca-Cola’s policy interference ( Bonilla-Chacín et al ., 2016 ; interview with Ana Larrañaga, April 15, 2019; interview with Sergio Juárez, April 12, 2019; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019; interview with anonymous health official, April 25 and 29, 2019). Furthermore, the SoH maintained its tradition of not proactively seeking the advice of advocates in favour of defending the public’s healthcare interests, reflecting a pre-existing tradition of policy elites viewing civil society as unworthy of participating in concrete policy discussions ( Rosenberg, 2015 ; interview with Luis Cruz, April 29, 2019; interview with Yarishdy Mora, April 9, 2019).

This article has shown that one of the reasons why the industrial epidemics of obesity and type-2 diabetes burgeoned in Mexico has to do with Coca-Cola’s ongoing ability to negatively influence politicians’ decisions not to prioritize NCD policies, taking on several political strategies to prohibit ‘policy windows’ ( Kingdon, 1984 ) from opening and leading to more aggressive NCD policies. With unfettered access to markets, facilitating the marketing, sale and consumption of Coca-Cola’s unhealthy products, this industry has behaved in what Moodie et al . (2013) refer to as a dangerous ‘disease vector’ ( Gilmore et al ., 2011 ).

In attempting to explain why this is the case, this article has introduced the IPIC framework. In light of the recent literature discussing the various political tactics that tobacco, alcohol and food industries use to manipulate NCD policies, why is another analytical framework needed? A brief review of the literature helps to address this question.