- Digital Marketing

- Facebook Marketing

- Instagram Marketing

- Ecommerce Marketing

- Content Marketing

- Data Science Certification

- Machine Learning

- Artificial Intelligence

- Data Analytics

- Graphic Design

- Adobe Illustrator

- Web Designing

- UX UI Design

- Interior Design

- Front End Development

- Back End Development Courses

- Business Analytics

- Entrepreneurship

- Supply Chain

- Financial Modeling

- Corporate Finance

- Project Finance

- Harvard University

- Stanford University

- Yale University

- Princeton University

- Duke University

- UC Berkeley

- Harvard University Executive Programs

- MIT Executive Programs

- Stanford University Executive Programs

- Oxford University Executive Programs

- Cambridge University Executive Programs

- Yale University Executive Programs

- Kellog Executive Programs

- CMU Executive Programs

- 45000+ Free Courses

- Free Certification Courses

- Free DigitalDefynd Certificate

- Free Harvard University Courses

- Free MIT Courses

- Free Excel Courses

- Free Google Courses

- Free Finance Courses

- Free Coding Courses

- Free Digital Marketing Courses

Top 15 FinTech Case Studies [A Detailed Exploration] [2024]

In the dynamic realm of financial technology—often abbreviated as FinTech—groundbreaking innovations have revolutionized how we interact with money, democratizing access to myriad financial services. No longer confined to traditional banking and financial institutions, today’s consumers can easily invest, transact, and manage their finances at their fingertips. Through a deep dive into the top five FinTech case studies, this article seeks to illuminate the transformative power of financial technology. From trailblazing start-ups to industry disruptors, we will unravel how these companies have reshaped the financial landscape, offering invaluable lessons for consumers and future FinTech leaders.

Top 15 FinTech case studies [A Detailed Exploration] [2024]

Case study 1: square – democratizing payment processing.

Launched in 2009 by Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey, Square sought to fill a gaping hole in the financial services market—accessible payment processing for small businesses. In an industry overshadowed by high costs and complexity, Square introduced a game-changing point-of-sale (POS) system, using a tiny card reader that could be plugged into a smartphone.

Key Challenges

1. High Costs: The financial burden of traditional payment systems made it difficult for small businesses to participate, affecting their growth and market reach.

2. Complexity: Legacy systems were cumbersome, requiring hefty upfront investments in specialized hardware and software, with a steep learning curve for users.

3. Limited Accessibility: Many small businesses had to resort to cash-only operations, losing potential customers who preferred card payments.

Related: Important FinTech KPIs Explained

Strategies Implemented

1. User-Friendly Hardware: Square’s portable card reader was revolutionary. Easy to use and set up, it integrated seamlessly with smartphones.

2. Transparent Pricing: A flat-rate fee structure eliminates hidden costs, making budgeting more predictable for businesses.

3. Integrated Business Solutions: Square went beyond payment processing to offer additional services such as inventory management, analytics, and loans.

Results Achieved

1. Market Penetration: As of 2023, Square boasted over 4 million sellers using its platform, solidifying its market position.

2. Revenue Growth: Square achieved significant financial gains, reporting $4.68 billion in revenue in Q2 2021—a 143% year-over-year increase.

3. Product Diversification: Expanding its ecosystem, Square now offers an array of services from payroll to cryptocurrency trading through its Cash App.

Key Learnings

1. Simplicity is Key: Square’s user-centric design proved that simplifying complex processes can open new markets and encourage adoption.

2. Holistic Ecosystems: Offering integrated services can foster customer loyalty and increase lifetime value.

3. Transparency Builds Trust: A clear, straightforward fee structure can differentiate a FinTech solution in a market known for its opaqueness.

4. Accessibility: Providing easy-to-use and affordable services can empower smaller businesses, contributing to broader economic inclusion.

Related: Benefits of Green FinTech for Businesses

Case Study 2: Robinhood – Democratizing Investment

Founded in 2013, Robinhood burst onto the financial scene with a disruptive promise—commission-free trading. Unlike traditional brokerage firms that charged a fee for every trade, Robinhood allowed users to buy and sell stocks at no direct cost. The platform’s user-friendly interface and sleek design made it particularly appealing to millennials and Gen Z, demographics often underrepresented in the investment world.

1. High Commissions: Traditional brokerages often had fee structures that discouraged individuals, especially younger investors, from participating in the stock market.

2. Complex User Interfaces: Many existing trading platforms featured clunky, complicated interfaces that were intimidating for novice investors.

3. Limited Access: Entry-level investors often felt the investment landscape was an exclusive club beyond their financial and technical reach.

1. Commission-Free Trading: Robinhood’s flagship offering eliminated the financial barriers that commissions presented, inviting a new cohort of individual investors into the market.

2. User-Friendly Design: A sleek, intuitive interface made stock trading less intimidating, broadening the platform’s appeal.

3. Educational Resources: Robinhood provides educational content to help novice investors understand market dynamics, equipping them for more informed trading.

1. Market Disruption: Robinhood’s model has pressured traditional brokerage firms to rethink their fee structures, with several following suit by offering commission-free trades.

2. User Growth: As of 2023, Robinhood has amassed over 23.2 million users, a testament to its market penetration.

3. Public Scrutiny: Despite its success, Robinhood has not been without controversy, especially regarding its revenue model and lack of transparency. These issues have sparked widespread debate about ethical practices in fintech.

1. User-Centricity Drives Adoption: Robinhood’s easy-to-use platform illustrates that reducing friction encourages higher user engagement and diversifies the investor base.

2. Transparency is Crucial: The controversies surrounding Robinhood serve as a cautionary tale about the importance of transparent business practices in building and maintaining consumer trust.

3. Disruption Spurs Industry Change: Robinhood’s entry forced a reevaluation of longstanding industry norms, underscoring the influence a disruptive FinTech company can wield.

Related: How to Get an Internship in the FinTech Sector?

Case Study 3: Stripe – Simplifying Online Payments

Founded in 2010 by Irish entrepreneurs Patrick and John Collison, Stripe set out to solve a significant problem—simplifying online payments. During that time, businesses looking to accept payments online had to navigate a complex labyrinth of banking relationships, security protocols, and regulatory compliance. Stripe introduced a straightforward solution—APIs that allow businesses to handle online payments, subscriptions, and various other financial transactions with ease.

1. Complex Setup: Traditional online payment methods often require cumbersome integration and extensive documentation.

2. Security Concerns: Handling financial transactions online raised issues about data safety and compliance with financial regulations.

3. Limited Flexibility: Most pre-existing payment solutions were not adaptable to specific business needs, particularly for start-ups and SMEs.

1. Simple APIs: Stripe’s suite of APIs allowed businesses to integrate payment gateways effortlessly, removing barriers to entry for online commerce.

2. Enhanced Security: Stripe implemented robust security measures, including tokenization and SSL encryption, to protect transaction data.

3. Customization: Stripe’s modular design gave businesses the freedom to tailor the payment experience according to their specific needs.

1. Broad Adoption: Stripe’s intuitive and secure payment solutions have attracted a diverse client base, from start-ups to Fortune 500 companies.

2. Global Reach: As of 2023, Stripe operates in over 46 countries, testifying its global appeal and functionality.

3. Financial Milestone: Stripe’s valuation skyrocketed to $50 billion in 2023, making it one of the most valuable FinTech companies globally.

1. Ease of Use: Stripe’s success proves that a user-friendly, straightforward approach can go a long way in attracting a wide range of customers.

2. Security is Paramount: Handling financial data requires stringent security measures, and Stripe’s focus on secure transactions sets an industry standard.

3. Scalability and Flexibility: Providing a modular, customizable solution allows businesses to scale and adapt, increasing customer satisfaction and retention.

Related: FinTech Skills to Add in Your Resume

Case Study 4: Coinbase – Mainstreaming Cryptocurrency

Founded in 2012, Coinbase set out to make cryptocurrency trading as simple and accessible as using an email account. At the time, the world of cryptocurrency was a wild west of complicated interfaces, murky regulations, and high-risk investments. Coinbase aimed to change this by offering a straightforward, user-friendly platform to buy, sell, and manage digital currencies like Bitcoin, Ethereum, and many others.

1. User Complexity: Before Coinbase, cryptocurrency trading required high technical know-how, making it inaccessible to the average person.

2. Security Risks: The lack of centralized governance in the crypto world led to various security concerns, including hacking and fraud.

3. Regulatory Uncertainty: The absence of clear regulations concerning cryptocurrency created a hesitant environment for both users and investors.

1. User-Friendly Interface: Coinbase developed a sleek, easy-to-use platform with a beginner-friendly approach, which allowed users to start trading with just a few clicks.

2. Enhanced Security: The platform incorporated advanced security features such as two-factor authentication (2FA) and cold storage for digital assets to mitigate risks.

3. Educational Content: Coinbase offers guides, tutorials, and other educational resources to help demystify the complex world of cryptocurrency.

1. Mass Adoption: As of 2023, Coinbase had over 150 million verified users, contributing significantly to mainstreaming cryptocurrencies.

2. Initial Public Offering (IPO): Coinbase went public in April 2021 with a valuation of around $86 billion, highlighting its commercial success.

3. Regulatory Challenges: While Coinbase has succeeded in democratizing crypto trading, it continues to face scrutiny and regulatory hurdles, emphasizing the sector’s evolving nature.

1. Accessibility Drives Adoption: Coinbase’s user-friendly design has played a pivotal role in driving mass adoption of cryptocurrencies, illustrating the importance of making complex technologies accessible to everyday users.

2. Security is a Selling Point: In an ecosystem rife with security concerns, robust safety measures can set a platform apart and attract a broader user base.

3. Regulatory Adaptability: The ongoing regulatory challenges highlight the need for adaptability and proactive governance in the fast-evolving cryptocurrency market.

Related: Top FinTech Interview Questions and Answers

Case Study 5: Revolut – All-In-One Financial Platform

Founded in 2015, Revolut started as a foreign currency exchange service, primarily focusing on eliminating outrageous foreign exchange fees. With the broader vision of becoming a financial super-app, Revolut swiftly expanded its services to include digital banking, stock trading, cryptocurrency exchange, and other financial services. This rapid evolution aimed to provide users with an all-encompassing financial solution on a single platform.

1. Fragmented Services: Before Revolut, consumers had to use multiple platforms for various financial needs, leading to a fragmented user experience.

2. High Costs: Traditional financial services, particularly foreign exchange and cross-border payments, often have hefty fees.

3. Slow Adaptation: Conventional banking systems were slow to integrate new financial technologies, leaving a gap in the market for more agile solutions.

1. Unified Platform: Revolut combined various financial services into a single app, offering users a seamless experience and a one-stop solution for their financial needs.

2. Competitive Pricing: By leveraging FinTech efficiencies, Revolut offered competitive rates for services like currency exchange and stock trading.

3. Rapid Innovation: The platform continually rolled out new features, staying ahead of consumer demand and forcing traditional institutions to catch up.

1. User Growth: As of 2023, Revolut has amassed over 30 million retail customers, solidifying its reputation as a financial super-app.

2. Revenue Increase: In 2021, Revolut’s revenues climbed to approximately $765 million, indicating its business model’s viability.

3. Industry Influence: Revolut’s multi-functional capabilities have forced traditional financial institutions to reconsider their offerings, pushing the industry toward integrated, user-friendly solutions.

1. User-Centric Design: Revolut’s success stems from its focus on solving real-world consumer problems with an easy-to-use, integrated platform.

2. Agility Wins: In the fast-paced world of fintech, the ability to innovate and adapt quickly to market needs can be a significant differentiator.

3. Competitive Pricing is Crucial: Financial services have always been a cost-sensitive sector. Offering competitive pricing can draw users away from traditional platforms.

Related: Surprising FinTech Facts and Statistics

Case Study 6 : Chime – Revolutionizing Personal Banking

Essential term: digital banking.

Digital banking represents the digitization of all traditional banking activities, where financial services are delivered predominantly through the internet. This innovation caters to a growing demographic of tech-savvy users seeking efficient and accessible banking solutions.

Founded in 2013, Chime entered the financial market with a bold mission: to redefine personal banking through simplicity, transparency, and customer-centricity. At a time when traditional banks were mired in fee-heavy structures and complex service models, Chime introduced a revolutionary no-fee model complemented by a streamlined digital experience, challenging the status quo of personal banking.

1. Fee-Heavy Structure: Traditional banks heavily relied on various fees, including overdraft and maintenance charges, alienating a significant portion of potential customers, particularly those seeking straightforward banking solutions.

2. Complexity and Inaccessibility: Conventional banking systems were often marred by cumbersome procedures and lacked user-friendly interfaces, making them less appealing, especially to younger, more tech-savvy generations.

3. Customer Service: The traditional banking sector frequently struggled with providing proactive and responsive customer service, creating a gap in customer satisfaction and engagement.

1. No-Fee Model: By eliminating common banking fees such as overdraft fees, Chime positioned itself as a customer-friendly alternative, significantly attracting customers frustrated with traditional banking penalties.

2. User-Friendly App: Chime’s app was designed with user experience at its core, offering an intuitive and accessible platform for everyday banking operations, thereby enhancing overall customer experience.

3. Automatic Savings Tools: Chime innovated with features like automatic savings round-up and early paycheck access, designed to empower customers in their financial management.

1. Expansive Customer Base: Chime successfully captured a broad market segment, particularly resonating with millennials and Gen Z, evidenced by its rapid accumulation of millions of users.

2. Catalyst for Innovation: The company’s growth trajectory and model pressured traditional banks to reassess and innovate their fee structures and service offerings.

3. Valuation Surge: Reflecting its market impact and success, Chime’s valuation experienced a substantial increase, marking its significance in the banking sector.

1. Customer-Centric Approach: Chime’s journey underscores the importance of addressing customer pain points, such as fee structures, and offering a seamless digital banking experience, which can be instrumental in rapid user base growth.

2. Innovation in Features: The introduction of genuinely helpful financial management tools can significantly differentiate a FinTech company in a competitive market.

3. Disruptive Influence: Chime’s success story illustrates how a digital-first approach can disrupt and challenge traditional banking models, paving the way for new, innovative banking experiences.

Related: Is FinTech Overhyped?

Case Study 7 : LendingClub – Pioneering Peer-to-Peer Lending

Essential term: peer-to-peer (p2p) lending.

Peer-to-Peer (P2P) lending is a method of debt financing that enables individuals to borrow and lend money without using an official financial institution as an intermediary. This model directly connects borrowers and lenders through online platforms.

LendingClub, founded in 2006, emerged as a trailblazer in the lending industry by introducing a novel P2P lending model. This innovative approach offered a substantial departure from the traditional credit system, typically dominated by banks and credit unions, aiming to democratize access to credit.

1. High-Interest Rates: Traditional loans were often synonymous with high-interest rates, rendering them inaccessible or financially burdensome for many borrowers.

2. Limited Access to Credit: Conventional lending mechanisms frequently sidelined individuals with lower credit scores, creating a significant barrier to credit access.

3. Intermediary Costs: The traditional lending process involves numerous intermediaries, leading to additional costs and inefficiencies for borrowers and lenders.

1. Direct Platform: LendingClub’s platform revolutionized lending by directly connecting borrowers with investors, reducing the overall cost of obtaining loans.

2. Risk Assessment Tools: The company employed advanced algorithms for assessing the risk profiles of borrowers, which broadened the spectrum of loan accessibility to include individuals with diverse credit histories.

3. Streamlined Process: LendingClub’s online platform streamlined the loan application and disbursement processes, enhancing transparency and efficiency.

1. Expanded Credit Access: LendingClub significantly widened the avenue for credit, particularly benefiting those with less-than-perfect credit scores.

2. Influencing the Market: The P2P lending model introduced by LendingClub prompted traditional lenders to reconsider their rates and processes in favor of more streamlined, borrower-friendly approaches.

3. Navigating Regulatory Hurdles: The journey of LendingClub highlighted the intricate regulatory challenges of financial innovation, underscoring the importance of adaptive compliance strategies.

1. Efficiency of Direct Connections: Eliminating intermediaries in the lending process can lead to substantial cost reductions and process efficiency improvements.

2. Broadening Credit Accessibility: FinTech can play a pivotal role in democratizing access to financial services by implementing innovative risk assessment methodologies.

3. Importance of Regulatory Compliance: Sustainable innovation in the FinTech sector necessitates a keen awareness and adaptability to the evolving regulatory landscape.

Related: Who is a FinTech CTO?

Case Study 8 : Brex – Reinventing Business Credit for Startups

Essential term: corporate credit cards.

Corporate credit cards are specialized financial tools designed for business use. They offer features like higher credit limits, rewards tailored to business spending, and, often, additional tools for expense management.

Launched in 2017, Brex emerged with a bold vision to transform how startups access and manage credit. In a financial landscape where traditional corporate credit cards posed steep requirements and were often misaligned with the unique needs of burgeoning startups, Brex introduced an innovative solution. Their model focused on the company’s cash balance and spending patterns rather than relying on personal credit histories.

1. Inaccessibility for Startups: Traditional credit systems, with their reliance on extensive credit history, were largely inaccessible to new startups, which typically lacked this background.

2. Rigid Structures: Conventional corporate credit cards were not designed to accommodate rapidly evolving startups’ fluid and dynamic financial needs.

3. Personal Guarantee Requirement: A common stipulation in business credit involves personal guarantees, posing a significant risk for startup founders.

1. No Personal Guarantee: Brex innovated by offering credit cards without needing a personal guarantee, basing creditworthiness on business metrics.

2. Tailored Financial Solutions: Understanding the unique ecosystem of startups, Brex designed its services to be flexible and in tune with their evolving needs.

3. Technology-Driven Approach: Utilizing advanced algorithms and data analytics, Brex could assess the creditworthiness of startups in a more nuanced and comprehensive manner.

1. Breaking Barriers: Brex made corporate credit more accessible to startups, removing traditional barriers.

2. Market Disruption: By tailoring its product, Brex pressures traditional financial institutions to innovate and rethink its credit card offerings.

3. Rapid Growth: Brex’s unique approach led to rapid adoption within the startup community, significantly growing its customer base and market presence.

1. Adapting to Market Needs: Brex’s success underscores the importance of understanding and adapting to the specific needs of your target market.

2. Innovative Credit Assessment: Leveraging technology for credit assessment can open new avenues and democratize access to financial products.

3 Risk and Reward: The move to eliminate personal guarantees, while riskier, positioned Brex as a game-changer, highlighting the balance between risk and innovation in FinTech.

Related: Is FinTech a Dying Career Industry?

Case Study 9 : SoFi – Transforming Personal Finance

Essential term: financial services platform.

A financial services platform offers a range of financial products and services, such as loans, investment options, and banking services, through a unified digital interface.

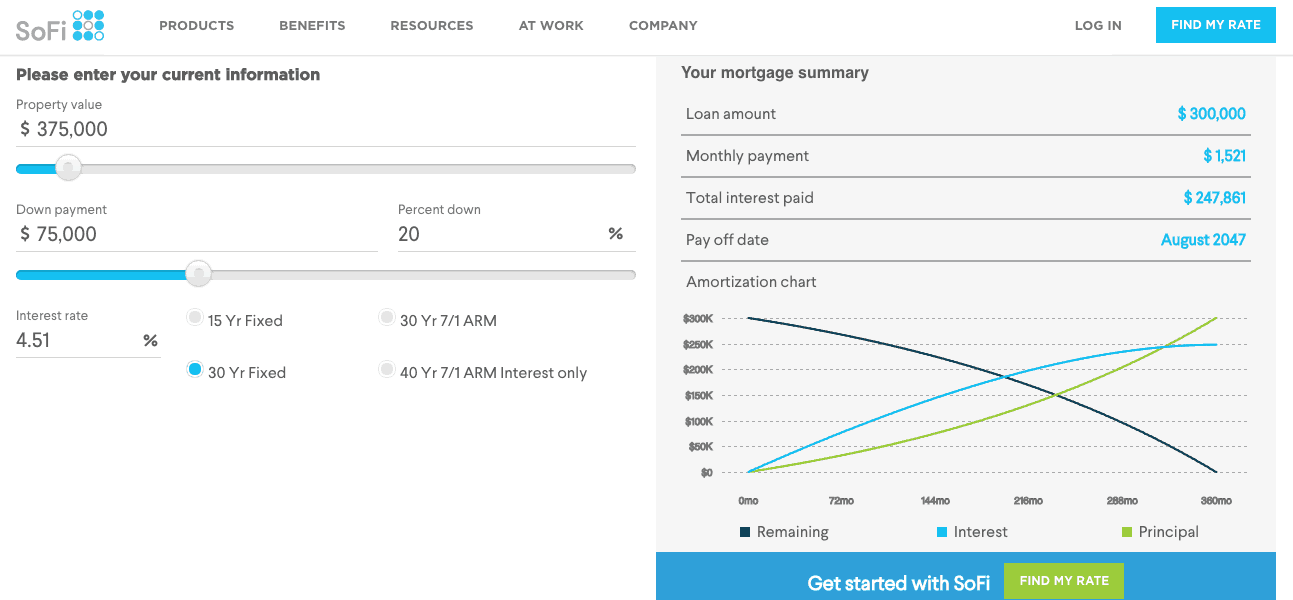

SoFi, short for Social Finance, Inc., was founded in 2011 to revolutionize personal finance. Initially focused on student loan refinancing, SoFi quickly expanded its offerings to include a broad spectrum of financial services, including personal loans, mortgages, insurance, investment products, and a cash management account. This expansion was driven by a vision to provide a one-stop financial solution for consumers, particularly catering to the needs of early-career professionals.

1. Fragmented Financial Services: Consumers often had to navigate multiple platforms and institutions to manage their various financial needs, leading to a disjointed financial experience.

2. Student Loan Debt: Many graduates needed more flexible and affordable refinancing options with student debt escalating.

3. Accessibility and Education: A significant segment of the population lacked access to comprehensive financial services and the knowledge to navigate them effectively.

1. Diverse Financial Products: SoFi expanded its product range beyond student loan refinancing to include a suite of financial services, offering more holistic financial solutions.

2. Tech-Driven Approach: Utilizing technology, SoFi provided streamlined, user-friendly experiences across its platform, simplifying the process of managing personal finances.

3. Financial Education and Advice: SoFi offered educational resources and personalized financial advice, positioning itself as a partner in its customers’ financial journey.

1. Expanding Consumer Base: SoFi succeeded in attracting a broad customer base, especially among young professionals looking for integrated financial services.

2. Innovation in Personal Finance: The company’s expansion into various financial services positioned it as a leader in innovative personal finance solutions.

3. Brand Recognition and Trust: With its comprehensive approach and focus on customer education, SoFi built a strong brand reputation and trust among its users.

1. Integrated Services Appeal: Offering a broad array of financial services through a single platform can attract customers seeking a unified financial management experience.

2. Leveraging Technology for Ease: Using technology to simplify and streamline financial services is key to enhancing customer experience and satisfaction.

3. Empowering Through Education: Providing users with financial education and advice can foster long-term customer relationships and trust.

Related: FinTech vs Investment Banking

Case Study 10 : Apple Pay – Redefining Digital Payments

Essential term: mobile payment system.

A mobile payment system allows consumers to make payments for goods and services using mobile devices, typically through apps or integrated digital wallets.

Launched in 2014, Apple Pay marked Apple Inc.’s foray into the digital payment landscape. It was introduced with the aim of transforming how consumers perform transactions, focusing on enhancing the convenience, security, and speed of payments. Apple Pay allows users to make payments using their Apple devices, employing Near Field Communication (NFC) technology. This move was a strategic step in leveraging the widespread use of smartphones for financial transactions.

1. Security Concerns: The rising incidences of data breaches and fraud in digital payments made consumers skeptical about the security of mobile payment systems.

2. User Adoption: Convincing consumers to shift from traditional payment methods like cash and cards to a digital platform requires overcoming ingrained habits and perceptions.

3. Merchant Acceptance: For widespread adoption, a large number of merchants needed to accept and support Apple Pay.

1. Enhanced Security Features: Apple Pay uses a combination of device-specific numbers and unique transaction codes, ensuring that card numbers are not stored on devices or servers, thereby enhancing transaction security.

2. Seamless Integration: Apple Pay was designed to work seamlessly with existing Apple devices, offering an intuitive and convenient user experience.

3. Extensive Partnership with Banks and Retailers: Apple forged partnerships with numerous banks, credit card companies, and retailers to ensure widespread acceptance of Apple Pay.

1. Widespread Adoption: Apple Pay quickly gained a significant user base, with millions of transactions processed shortly after its launch.

2. Market Leadership: Apple Pay became one of the leading mobile payment solutions globally, setting a standard in the digital payment industry.

3. Influence on Payment Behaviors: The introduction of Apple Pay substantially accelerated the shift towards contactless payments and mobile wallets.

1. Trust Through Security: The emphasis on security can be a major driving force in user adoption of new financial technologies.

2. Integration and Convenience: A system that integrates seamlessly with users’ daily lives and provides tangible convenience can successfully change long-standing consumer habits.

3. Strategic Partnerships: Building a network of partnerships is key to the widespread acceptance and success of a new payment system.

Related: FinTech Failure Examples

Case Study 11 : Ant Group (Formerly Ant Financial) – A Global Digital Payment and Lifestyle Platform

Ant Group, founded in 2014 as a subsidiary of Alibaba, created Alipay, a revolutionary digital payment platform. Alipay quickly became one of the largest digital wallets globally, offering services like fund transfers, bill payments, and lifestyle solutions.

1. Market Fragmentation: The digital payment market was crowded with various regional players competing for dominance.

2. Regulatory Scrutiny: Ant Group faced strict regulations around data security, anti-money laundering, and financial stability.

3. Trust Issues: Getting users to trust an entirely digital platform for handling their finances was challenging.

1. Diverse Service Ecosystem: Alipay expanded beyond payments to offer travel booking, wealth management, insurance, and more.

2. Partnerships: Collaborated with global financial institutions to widen its user base.

3. Data Security: Implemented advanced data security measures to ensure transactions were safe.

1. Global Reach: Alipay grew to over 1 billion users globally, with significant market penetration outside China.

2. Diversification: The platform diversified to include financial services, creating a comprehensive lifestyle app.

3. Valuation Growth: Ant Group achieved a multi-billion-dollar valuation, underscoring its industry influence.

1. Ecosystem Strategy: Providing a complete and integrated range of services can help to boost user engagement and foster loyalty.

2. Regulatory Agility: Navigating regulatory challenges requires proactive compliance and collaboration with authorities.

3. Global Partnerships: Strategic alliances can significantly enhance market reach.

Related: How to Value a FinTech Company?

Case Study 12 : Nubank – Revolutionizing Banking in Latin America

Nubank, established in 2013, is a prominent digital bank globally and a top FinTech in Latin America. It started with credit cards before expanding into other banking services, aiming to offer user-friendly and accessible banking to underbanked populations.

1. Financial Inclusion: A large portion of the population in Latin America was unbanked or underbanked.

2. Trust in Financial Systems: Many people lack trust in traditional financial institutions due to high fees and poor customer service.

3. Market Complexity: The regional market posed challenges due to regulatory differences across Latin American countries.

1. No-Fee Model: Offered a no-fee credit card that appealed to customers tired of hidden fees.

2. Customer-Centric Design: Developed an intuitive mobile app to simplify banking transactions.

3. Market Expansion: Adopted a localized approach for market expansion across multiple countries.

1. Rapid Growth: Nubank has garnered over 40 million customers, growing swiftly beyond Brazil.

2. Innovation Leader: Recognized as an industry innovator for driving digital banking adoption.

3. Investment Magnet: By drawing significant investments, Nubank has emerged as one of the most valuable FinTech companies worldwide.

1. Localized Strategy: Customizing services based on regional market needs is vital for rapid growth.

2. Customer Trust: Transparent, no-fee models can build customer trust and drive adoption.

3. Simplified UX: A user-friendly interface simplifies banking for previously underserved customers.

Related: FinTech vs Finance: Key Differences

Case Study 13 : Klarna – Transforming E-Commerce Payments

Founded in 2005, Klarna is a pioneer in BNPL, offering an alternative to credit cards. Its seamless integration with online merchants and easy-to-understand payment plans attracted millions of users.

1. Consumer Trust: Convincing consumers to trust a new payment method required overcoming skepticism.

2. Merchant Acceptance: Onboarding merchants and integrating the solution with existing payment systems was challenging.

3. Regulatory Concerns: BNPL faced scrutiny around potential overspending and consumer debt.

1. Simple User Experience: Developed a clear, intuitive checkout process, reducing payment friction.

2. Merchant Partnerships: Partnered with thousands of merchants, integrating seamlessly into e-commerce platforms.

3. Consumer Education: Educated consumers on responsible spending and minimizing debt risk.

1. Merchant Network: Klarna is now partnered with over 250,000 retailers worldwide.

2. Market Adoption: Millions of consumers use Klarna for seamless e-commerce transactions.

3. Industry Influence: Klarna’s BNPL model inspired similar solutions across the FinTech industry.

1. Simple Integration: Seamless merchant integration can accelerate solution adoption.

2. Consumer Responsibility: Educating consumers on spending habits minimizes debt risk.

3. New Payment Model: BNPL offers a viable alternative to traditional credit systems, transforming e-commerce payments.

Related: Top FinTech Terms Defined

Case Study 14 : Plaid – Connecting Financial Data Seamlessly

Founded in 2013, Plaid aimed to streamline how people connect their financial data to various apps. It bridges the gap between users’ bank accounts and financial apps like budgeting tools, payment platforms, and lending services.

1. Data Security: Accessing sensitive financial data requires robust security measures.

2. Standardization Issues: Banks had different protocols, making establishing a consistent connection difficult.

3. Regulatory Compliance: Navigating data protection laws across regions posed a significant challenge.

1. Secure APIs: Developed secure APIs to facilitate safe and standardized access to financial data.

2. Bank Partnerships: Collaborated with major financial institutions to ensure consistent data access.

3. Developer Focus: Provided developers with comprehensive tools and documentation for easy integration.

1. Developer Adoption: Plaid’s APIs became the backbone for thousands of financial apps.

2. Market Penetration: The platform now connects to thousands of financial institutions worldwide.

3. M&A Success: Plaid’s impact attracted significant acquisitions and partnerships within the FinTech ecosystem.

1. Data Security Focus: Prioritizing data security builds user trust and drives adoption.

2. Standardization: Developing standardized protocols for data access is crucial in fragmented markets.

3. Ecosystem Collaboration: Building partnerships with financial institutions is vital for seamless integration.

Related: Can FinTech Replace Banks?

Case Study 15 : Adyen – Unifying Global Payments

Established in 2006, Adyen is a global payment company offering merchants a single, unified platform for all their payment needs. It aimed to streamline payment acceptance by simplifying the process across various channels, payment methods, and regions.

1. Regional Fragmentation: Payment methods and regulations varied significantly by region.

2. Omnichannel Complexity: Offering consistent payment experiences across multiple channels was difficult.

3. Merchant Onboarding: Merchants struggled with complex onboarding processes and technical integrations.

1. Unified Platform: Created a single platform where merchants could accept payments across regions and channels.

2. Regional Compliance: Ensured the platform met regulatory requirements for each region.

3. Omnichannel Focus: Merchants can now offer uniform payment experiences across various channels including online, in-store, and mobile, thanks to the enabled technology.

1. Global Reach: Adyen became a preferred payment platform for merchants worldwide.

2. Unified Experience: Both merchants and consumers benefited from the platform’s unified approach as it simplified the payment process for both parties.

3. Merchant Growth: Adyen merchants have reported enhanced customer satisfaction and increased conversion rates.

1. Unified Approach: A unified approach simplifies payment acceptance across channels and regions.

2. Regulatory Compliance: Adapting to local regulatory requirements is essential to ensure smooth cross-border operations.

3. Omnichannel Presence: Maintaining consistency across all payment channels can improve the customer experience and drive business growth.

Related: Pros and Cons of FinTech Career

These stories of globally renowned FinTech trailblazers offer invaluable insights, providing a must-read blueprint for anyone looking to make their mark in this rapidly evolving industry.

1. Square shows that focusing on user needs, especially in underserved markets, can drive innovation and market share.

2. Robinhood serves as both an inspiration and a cautionary tale, advocating for democratization while emphasizing the importance of ethical practices.

3. Stripe proves that simplifying complex processes through customizable, user-friendly solutions can redefine industries.

4. Coinbase highlights the transformative potential of making new financial instruments like cryptocurrency accessible while reminding us of regulatory challenges.

5. Revolut sets the bar high with its user-centric, all-in-one platform, emphasizing the need for agility and competitive pricing in the sector.

The key to FinTech success lies in simplicity, agility, user focus, and ethical considerations. These case studies serve as guiding lights for future innovation, emphasizing that technological superiority must be balanced with customer needs and ethical responsibilities.

- 10 ways AI is being used in Cruises [2024]

- 50 Female Leadership Facts & Statistics [2024]

Team DigitalDefynd

We help you find the best courses, certifications, and tutorials online. Hundreds of experts come together to handpick these recommendations based on decades of collective experience. So far we have served 4 Million+ satisfied learners and counting.

Career in Finance vs. Technology [Deep Analysis][2024]

How to Become a Finance Director? Skills and Scope [2024]

Is Fintech Overhyped? [2024]

Top 50 Finance Administrator Interview Questions & Answers [2024]

How to Become a Retail Banker [2024]

Venture Capital Interview Questions & Answers [2024]

Please fill out the form below for business, media and press inquires. For HR inquires, visit the careers page

Thanks For Reaching Out!

We look forward to talking soon.

Case Study | Banking and Financial Services

- Resilient Operating Model for a Leading FinTech and Digital Bank

How we brought resiliency to our leading FinTech client’s operations, transforming their business processes and driving efficiencies to enhance the overall customer experience.

- Banking and Financial Services

Supporting Rapid Growth Without Additional Operating Cost

As a large financial services company and one of the first peer-to-peer lenders, our client’s business had seen significant growth - including the recent acquisition of another bank.

There was a pressing need to optimize and streamline systems to integrate the businesses, but the client’s systems and processes weren’t set up for the transition. They faced high operating costs and inefficiencies as a result, which were hurting the customer experience.

Our client needed to unify and harmonize their business processes while leveraging AI and automation to transform the customer experience.

Sutherland stood out as a partner that could handle everything under one roof, delivering true omni-channel support to enable a 360-degree customer view.

Delivering Agility and Efficiency to Core Operations

First, we focused on introducing agility and efficiency to the client’s operations. In less than 60 days, we rolled out a nimble global right-shoring model with a mix of onshore, nearshore and offshore resources.

Next, we introduced Centers of Excellence for key business areas to ensure quality and consistency. This was supported with gamified learning to enable teams across the business to quickly standardize processes.

True omni-channel support, enabling a 360-degree customer view, helped establish a strong customer experience amid rapid change.

Sutherland Robility and Sutherland Extract also helped join up their siloed systems, including borrower support, credit decisioning and more.

TCO reduction; optimized via a tailored operating model and intelligent automation

Increase in customer satisfaction, enhanced by streamlined optimization, better and faster collections, reducing timelines and minimizing delinquency, learn how we can support your fintech needs, related insights.

Whitepaper | Banking and Financial Services

Future-Proof Your Fintech: Strategies To Succeed in 2024 (And Beyond)

Learn how to overcome industry challenges with agility and innovation by investing in the right tools, technology, and talent.

Leading Financial Services Provider Accelerates Operational Efficiencies

How Sutherland platforms used the power of intelligent automation and meta-bots to optimize back-office processes and reinvent workflows for better business outcomes.

Leading Third-Party Loan Servicing Company Overcomes Macro-Economic Challenges To Reduce TCO by 40%

Discover how Sutherland’s digital advisory services and intelligent automation enabled one of the largest third-party auto loan services to improve efficiencies and cost savings.

Explore More Insights

- Business Process Services

- Business Process Transformation

- Consulting Services

- Content Services

- Customer Interaction Services

- Digital Engineering Services

- Digital Finance

- Insight & Design

- Products x Platforms

- Sutherland Labs

- Transformation Engineering

- Communications, Media & Entertainment

- Energy and Utilities

- Mortgage Services

- Oil and Gas

- Retail and Consumer Packaged Goods

- Travel, Transportation, Hospitality & Logistics

- Case Studies

- Infographic

- Solution Overview

Paytm Case Study: The Journey of India's Leading FinTech Company

Devashish Shrivastava

Paytm is India's one of the biggest fintech startups founded in August 2010 by Vijay Shekhar Sharma. The startup offers versatile instalments, e-wallet, and business stages. Even though it began as an energizing stage in 2010, Paytm has changed its plan of action to become a commercial centre and a virtual bank model. It is likewise one of the pioneers of the cashback plan of action.

Paytm has changed itself into an Indian mammoth managing versatile instalments, banking administrations, commercial centre, Paytm gold, energize and charge installments, Paytm wallet and many other provisions which serve around 100 million enlisted clients.

The areas served by Paytm are India, Canada, and Japan, it is also accessible in 11 Indian dialects . It offers online use-cases as versatile energizes, service charge installments, travel, motion pictures, and occasions appointments. In-store instalments at markets, leafy foods shops, cafés, stopping, tolls, drug stores and instructive establishments can be accessed through the Paytm QR code.

One 97 Communications, the parent company of Paytm, is all set to raise its capital target of over ₹16,600 crores ($2.2 billion) through an IPO that it had filed earlier in July 2021. Paytm is seeking to raise $25 billion to $30 billion valuation post this IPO.

According to the organization, more than 7 million traders crosswise over India utilize its QR code to acknowledge instalments straightforwardly into their bank account. The organization uses commercials and pays a special substance to produce income. Let's look at this detailed case study on Paytm to know more about its growth and future plans.

Paytm - Latest News Origin of Paytm Business Model of Paytm Business Growth of Paytm Expected Future Growth of Paytm Why was Paytm Removed from Google Play Store?

Paytm - Latest News

1st November 2021 - The much-awaited Paytm IPO was launched with a price band of ₹ ₹2,080-2,150 per share.

13th October 2021 - Paytm users can now store Aadhaar, driving license, vehicle RC, insurance via Digilocker. Digilocker Mini App on Paytm offers access to these documents to users even when they're offline or in a low connectivity zone.

8th October 2021 - Paytm is looking forward to bringing in sovereign wealth funds as anchor investors in the company's pre-IPO placement.

5th October 2021 - Switzerland-based insurance giant, Swiss RE might join Paytm's insurance business' board.

3rd October 2021 - Paytm has acquired 100% stakes in CreditMate, a Mumbai-based digital lending startup.

Origin of Paytm

The saga and the emergence of Paytm are discussed in this section of the case study of Paytm. It was established in August 2010 with underlying speculation of $2 million by its originator Vijay Shekhar Sharma in Noida, an area nearby India's capital New Delhi .

It began as a prepaid portable and DTH energize stage, and later included information card, postpaid versatile and landline charge installments in 2013. By January 2014, the organization propelled the Paytm pocketbook, and the Indian Railways and Uber included it as an installment option.

It propelled into web-based business with online arrangements and transport ticketing.

In 2015, it disclosed more use-cases like instruction expenses, metro energizes power, gas, and water charge installments. Paytm likewise began driving the installment passage for the Indian Railways.

In 2016, Paytm propelled motion pictures, occasions, and entertainment meccas ticketing just as flight ticket appointments and Paytm QR. Later that year, it propelled rail bookings and gift vouchers . Paytm's enrolled client base developed from 11.8 million in August 2014 to 104 million in August 2015. Its movement business crossed $500 million in annualized GMV run rate, booking two million tickets for each month.

In 2017, Paytm became India's first installment application to traverse 100 million application downloads. That year, it propelled Paytm Gold, an item that enables clients to purchase as meagre as ₹1 of unadulterated gold on the web . It additionally propelled the Paytm Payments Bank and 'Inbox', and informing stage with in-talk installments among other products.

By 2018, it began enabling dealers to acknowledge Paytm UPI and card installments straightforwardly into their financial balances at 0% charge. It likewise propelled the 'Paytm for Business' application, enabling traders to follow their installments and everyday settlements instantly. This drove Paytm's shopper base to more than 7 million by March 2018.

The organization propelled two new riches—Paytm Gold Savings Plan and Gold Gifting—to rearrange long haul savings. It propelled into diversion and speculations, and stripe alongside AGTech to dispatch the stage of a transportable game Gamepind, and putting in Paytm cash with a venture of ₹9 large integers to bring venture and riches as board items for Indians. In May 2019, Paytm joined forces with Citibank to dispatch credit cards .

Business Model of Paytm

Paytm or "Payment Through Mobile" is India's biggest installment, trade, and e-wallet undertaking. It began in 2010 and is a brand of the parent organization One97 Communications, established by Vijay Shekhar Sharma. It was propelled as an online portable energize site and proceeded to change its plan of action to a virtual and commercial centre bank model.

The organization stands today as one of India's biggest online portable administrations that incorporates banking administrations, commercial centres, versatile installments, charge installments, and energize. It has so far given administrations to more than 100 million clients.

Paytm's enhancement has built a solid reputation and has turned out to be praiseworthy for some in the online installment industry. One of its increasingly vital accomplishments is in its joint effort with the Chinese web-based business Goliath, Alibaba for immense measures of subsidizing.

Aside from being a pioneer of the cashback plan of action, the organization has been commended for its introduction as a new business able to build huge partnerships in a limited time period.

Clients of Paytm Business

Paytm's core focus is on serving its Indian client base, especially the cell phone clients. Numerous Indian clients saw the computerized world as an opportunity to open a financial balance. Accessing simple online installments missed the mark, and clients wound up with only poor experience. Paytm presented itself as a superior option to deal with such situations.

Paytm Offers

A portion of Paytm's increasingly conspicuous suggestions was reviving the business which was the organization's underlying administration recommendation.

At that point, it proceeded to differentiate and progressed to creating more current administrations from any semblance of Paytm Wallet, E-business vertical to Digital Gold.

These improvements were appreciated in the form of the Chinese mammoth Alibaba's favours. Immense totals of cash were pumped into Paytm by Alibaba, expanding Paytm's speculation potential. Paytm used cricket and TV promotion to capture more clients.

Relationship with Clients

Paytm has a 24*7 client care focus to interface with its clients. Simultaneously, the vast majority of Paytm administrations are self-served in nature and are open through their foundation straightforward.

Paytm's Channel for Business

Paytm utilizes numerous channels to draw in clients. Aside from its very own site which drives clicks, Paytm has shaped associations with numerous customers and seller destinations that support its endeavour. Demonetization in India enabled the organization to succeed altogether and arrive at new clients too. Disconnected advertising is likewise a piece of their client procurement process.

Distinct Advantages

The RBI (Reserve Bank of India) permit fills in as Paytm's fundamental asset. It should be explicit to Paytm. Different assets like the plan/programming society make it simpler for lower-pay Indians to use Paytm.

Paytm, being an innovation stage, dangers perils, for example, security and misrepresentation which is the reason it needs to take viable measures in ensuring its buyer's cash by improving its security. It is likewise rolling out new improvements inside its foundation to draw in new clients and access their computerized wallets.

Partners of Paytm

Paytm accomplices with the banks that give it installment excursions into the financial framework just as escrow administrations. It works together with a heap of associations that accumulate bills and installments from its customers for its administration.

Structure of Costing

Paytm serves numerous clients which is the motivation behind why it is so cost-driven. The vast majority of its costs are identified with its foundation and client obtaining. It's a typical cost-shared by numerous organizations over the reality where client securing cost is significant.

The cash utilized in this procedure is higher than the income it makes in its underlying buys. Most of its financial limit is to put resources into sloping up of its security and stay away from the danger of misrepresentation, particularly when it needs to deal with more than 65 million clients in its foundation. It incorporates a framework that empowers clients to avoid any tax evasion hazard .

Revenue Model of Paytm

The Paytm revenue models come in two structures. Paytm makes commissions from the client exchanges through their utilization of its foundation. Escrow Accounts are the accounts from where it creates their income. Inferable from the non-appearance of its hidden capital, it offers clients no intrigue. Starting in 2018 Paytm has aggregated 3314.8 crore INR in income.

Paytm Wallet

Paytm wallet is one of Paytm's best benefits that structures a connection between the bank and the retailers. This semi-shut wallet empowers you to take care of your tabs, pay for your tickets, or pay anyone concerned.

Paytm wallet separated from its profit, as approved by the RBI, has the advantage of accepting enthusiasm for a purchaser store, much the same as some other Payment Gateways .

When you store a specific measure of cash in your Paytm wallet, it will at that point set aside that cash in another bank from which it will win enthusiasm eventually.

It is the Paytm wallet's fundamental capacity. For instance, suppose you make an installment of Rs. 1000 to a merchant and the vendor makes 10 exchanges to increase Rs. 10,000. If the installment of that sum is made through the Paytm wallet, the Paytm wallet will take a portion of about 1% of the aggregate sum. So the merchant will get around Rs. 9715.

Mobile Recharge Business

Since its origin in 2010, Paytm's underlying intention was to give online portable energizing administrations. Its capacity to create income was constantly shortsighted. Paytm's administration guidelines are as praiseworthy and proficient as those of other telecom specialist co-ops running from Vodafone to Telecom.

The administrations are without shortcomings and give solace to their clients. As of now, Paytm increases a commission of 2-3% per energize. It is because Paytm, attributable to its support to its client to keep reviving through its foundation, has more grounded power in dealing than different merchants. That is the reason the commission it obtains is so high. This commission from its revive administration fills in as its income.

These administrations have supported the organization essentially in extending its base and thus, developing exponentially. When the client is fulfilled by the administration or item, he makes an arrival to a similar undertaking in this manner. This way Paytm does client maintenance and produces more traffic . Paytm has used this methodology to further its potential benefit and keeps on reaping positive results.

Paytm Digital Gold Paytm Digital Gold

Inferable from its organization with MMTC-PAMP, the outstanding gold purifier, Paytm has propelled "Computerized Gold". This model enables clients to sell, purchase, or store gold in an advanced stage. Presently, clients need to pay at a rate just to get their gold conveyed to their families.

Paytm is very much aware of how much gold is put as a resource in India and is completely arranged to develop from this chance. The organization has made eminent arrangements to urge its clients to get their own Gold Bank Accounts individually. This record separated from empowering clients to purchase their gold will likewise furnish clients with simple access to other Paytm administrations.

In February 2017, Paytm propelled its Paytm Mall application which enables purchasers to shop from 1.4 lakh enrolled sellers. Paytm Mall is a B2C model enlivened by the model of China's biggest B2C retail stage, TMall. For 1.4 lakh merchants enlisted, items need to go through Paytm-guaranteed stockrooms and channels to guarantee buyer trust.

Paytm Mall has set up 17 satisfaction focuses crosswise over India and joined forces with 40+ messengers. Paytm Mall raised $200 million from Alibaba Cluster and SAIF Partners in March 2018. In May 2018, it posted losses of roughly Rs 1,800 crore with an income of Rs 774 crore for money related to the year 2018. Moreover, the piece of the pie in Paytm Mall dropped to 3% in 2018 from 5.6% in 2017.

Business Growth of Paytm

Advanced installments organization Paytm has professed to arrive at gross exchange esteem (GTV) of over $50 billion, while checking 5.5 billion exchanges in FY19. The Delhi NCR-based organization credited this development to the rising appropriation of Paytm over numerous utilization cases, for example, retail installments, expenses, utility installments, travel booking , excitement, games among others. It has as of late propelled membership-based prizes program (Paytm First) to aid development alongside expanding the client maintenance.

Discussing the feasible arrangements, senior VP of Paytm, Deepak Abbot stated, "We are centred around creating tech-driven arrangements, incorporated client lifecycle the board, upgrading the client experience and growing to Tier 4-5 urban communities. We are certain to accomplish 12 Bn exchanges before the part of the bargain year." Before a month ago, the Ministry Of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) had solicited Paytm to help its objective of encouraging 40 Bn advanced exchanges in FY20.

The organization shared designs to incorporate man-made brainpower in its model and achieve 2x development this year. Paytm professed to possess half piece of the installment entryway industry in India, with 400 Mn month to month exchanges on the stage.

Established by Vijay Shekhar Sharma in 2010, Paytm furnishes various new companies and huge organizations with arrangements running from a shareable PaytmQR code to profound coordination.

It empowers clients to process computerized installments through any favoured installment mode including credit and check cards, net banking, Paytm wallet, and UPI (bound together installment interface). Paytm had likewise propelled its very own installments bank in 2017.

Paytm Payments Bank is versatile first keep money with zero charges on every online exchange, (for example, IMPS, NEFT, RTGS) and no base equalization prerequisite. For investment accounts, the bank right now offers a loan cost of 4% per annum.

Expected Future Growth of Paytm

Computerized installments organization Paytm said it is looking to dramatically increase its exchange volume to 12 billion by part of the arrangement, from 5.5 billion out of 2018-19.

Paytm checked 2.5 billion exchanges in 2017-18. Paytm said it accomplished gross exchange esteem (GTV) of $50 billion out of 2018-19, as contrasted and $25 billion every year prior. GTV is the estimation of all-out exchanges done on the stage.

"This expansion is a consequence of the fast development in the reception of Paytm's computerized installments arrangements crosswise over on the web and disconnected for different use cases including retail installments, charges, utility installments, travel booking, amusement, games and that's only the tip of the iceberg,"

The organization said in an announcement. Its membership-based program Paytm First was propelled in March has pulled into equal parts a million supporters, the organization added.

Paytm has 350 million enrolled clients starting on 5 June, an organization authority said. Paytm offers a variety of installment alternatives that incorporate installment through portable wallets, just like ongoing installment framework Unified Payments Interface (UPI) and web banking.

The organization has been centred around structure instruments for dealers to streamline their everyday business needs. This has brought about enormous dealers obtaining who are very much furnished with innovation to acknowledge all installment modes (cards, wallet, and UPI). Paytm now intends to concentrate on embracing computerized reasoning and improving the UI .

Why was Paytm Removed from Google Play Store?

Paytm India app was removed from Google Play Store because it violated Google guidelines. While other apps like Paytm for Business, Paytm mall , Paytm Money, and a few more were still available. But after a few hours of being taken down, the Paytm app was back on Google Play Store.

#Paytm out of Google Play Store. Google: We don’t allow online casinos/support any unregulated gambling apps that facilitate sports betting. It includes if app leads consumers to an external website that allows them to participate in paid tournaments to win real money/cash prizes pic.twitter.com/poeZzXw5nA — CNBC-TV18 (@CNBCTV18Live) September 18, 2020

“We have these policies to protect users from potential harm. When an app violates these policies, we notify the developer of the violation and remove the app from Google Play until the developer brings the app into compliance. And in the case where there are repeated policy violations, we may take more serious action which may include terminating Google Play Developer accounts. Our policies are applied and enforced on all developers consistently,” Google Added.

Is Paytm a fintech company?

Yes, Paytm is India's leading and one of the most valued fintech startups founded by Vijay Shekar Sharma in 2010.

What are the areas served by Paytm?

Paytm is a leading fintech startup that not only operates in India but it also serves Canada and Japan.

When was Paytm established?

Paytm was founded in 2010 by Vijay Shekar Sharma.

What is Paytm and how does it work?

Paytm is a leading financial service and bill payments app that offers financial solutions to its customers, offline merchants and online platforms. All you need to do is open the Paytm app on your phone, click on 'Pay', and select 'QR code'. Scan the QR code of the receiver and enter the amount to be paid. The money will be transferred in a few seconds.

How much does Vijay Shekhar Sharma own in Paytm?

Vijay Shekhar Sharma currently owns 14.61% of the company.

Must have tools for startups - Recommended by StartupTalky

- Manage your business smoothly- Google Workspace

Maximizing Efficiency: 8 Best Productivity Gadgets for Entrepreneurs

According to technology experts, productivity gadgets are devices or innovations that help individuals complete tasks more efficiently and effectively. These devices frequently use technology to automate operations, organize information, or simplify complex activities, eliminating distractions while increasing output. These devices come in various forms, from hardware to software programs, each

AI for Modern Tech Stack Solutions in Business Operations

This article has been contributed by Ms. Karunya Sampath, Co-founder & CEO of Payoda Technologies. When it comes to artificial intelligence, there is always a fear of missing out. However, AI is here to stay. The notion of AI has expanded so much over time that you may already be using

How to Generate Real Estate Leads Using AI

This article has been contributed by Satya S Mahapatra, Chief Brand Custodian and part of the Founder’s office at JUSTO Realfintech. India’s real estate sector is on a growth trajectory with nearly 4.11 lakh residential units sold in 2023, registering a growth of over 33% from 2022.

Magnum Ice Cream Marketing Strategy | Secrets Behind Magnum's Success

Brands like Magnum become instant favorites of people. The credit goes to the public relations team that works behind the scenes and creates mind-boggling marketing strategies and advertisements. These help the brand build its place in the market. And for Magnum, it's Unilever that is responsible for the media spend

FINTECH EXPLAINED

Links to Companies Analyzed in Fintech Explained

Adyen ’s market multiples of comparable companies

Innovations by Alipay in payments

Amazon’s path into financial services

Ant Group and Tencent’s multi-sided platforms

Apple’s partnering with incumbents

Bitcoin’s solution to the double-spend problem and price volatility

Credit Karma’s $7 billion multi-sided platform

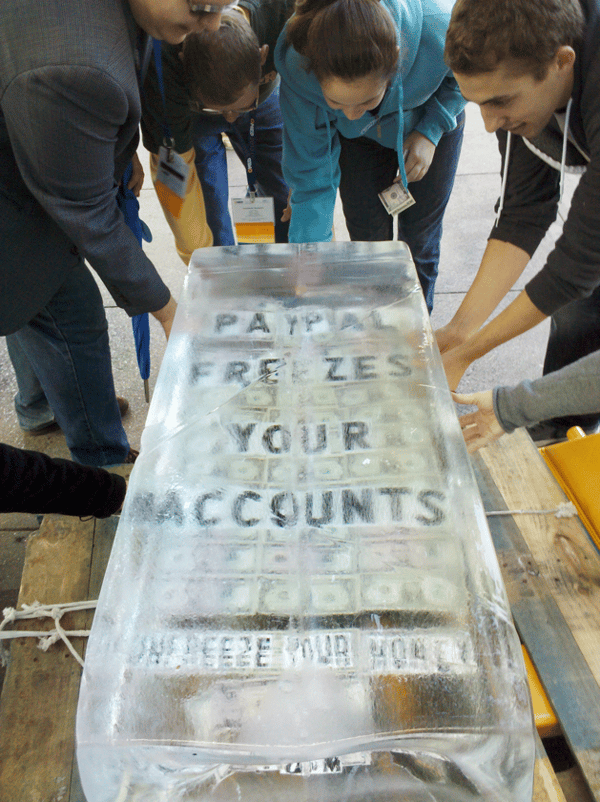

The DAO Hack questions the immutability of blockchains

.png)

Ethereum’s vision and dominance of DeFi

Facebook’s troubles with regulators

Rise and fall of the FTX cryptoexchange

Funding Circle’s financial ratios and performance in online lending

Goldman Sachs’ entry into consumer banking with Marcus

Google’s struggle to find product-market fit

JPMorgan’s value drivers and valuation in traditional banking

Kickstarter’s mission to bring creative projects to life

Lendified’s use of artificial intelligence (AI)

LendingClub’s marketplace lending platform

LUNA’s unstable stablecoin TerraUSD

MakerDAO and Curve Finance’s use-cases

Moven’s personal finance apps

Nubank building Latin America’s sixth largest bank

Innovations by Octopus in payments

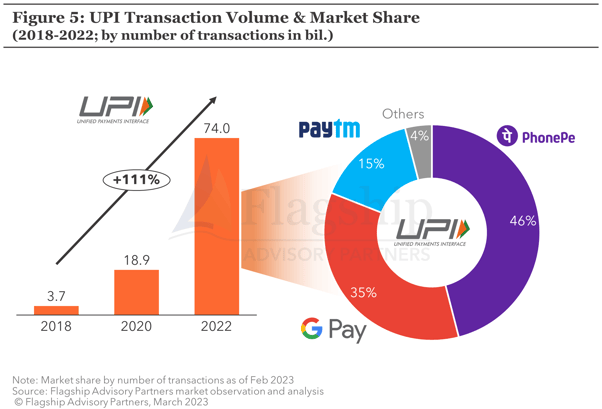

Paytm’s business model and monetization strategy

R3 Corda’s Permission DLT for regulated financial services

Ripple XRP’s search for a use-case

Robinhood’s commission-free trading for retail

Sensibill ’s personal finance apps

SoFi’s evolution from P2P lender to full-service bank

Tencent’s multi-sided platform

Vanguard’s move into robo-advice

Innovations by Vodafone's M-Pesa in payments

Wealthfront’s sophisticated, low-cost financial advice

.png)

Robo-advisor Wealthsimple’s seed-stage pitch to angel investors

.png)

Wise Financial’s pain point and market opportunity in payments

Innovations by WorldRemit in payments

Zhong An, China’s online-only insurance company

Voices Blog

International

FinTech Case Studies

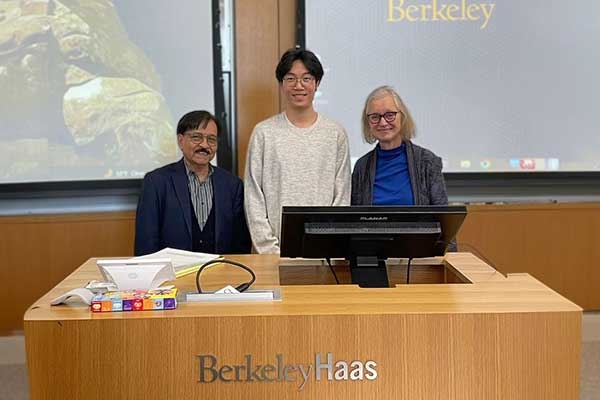

Uc berkeley faculty member gregory la blanc stresses that it’s all about the data.

UC Berkeley Haas Global Access Program (BHGAP) and BHGAP Innovation Program faculty member Gregory La Blanc recently hosted a Zoom meeting where he gave viewers a sneak peek into his FinTech class.

Check out the highlights from his talk below and watch the full video!

Citibank was the 300th largest bank in the United States. How do you go from the 300th largest bank in the United States to the largest credit card issuer in the entire world?

With machine learning, with data science, with analytics.

They saw that every single bank in the country is using the same scoring model: If your credit score is above this cutoff, you get a loan; if you're below this cutoff, you don't get a loan.

They said that there must be a more fine-grained model—to find the people who are rejected and see if a few of them might turn out to be good customers. They lent a whole bunch of money to people whom the other model said don't lend money to.

There were a lot of defaults. A lot of people didn't repay their loans. There was a reason why they were generally considered bad credits.

However, after seven or eight months, they were able to determine that a small percentage of them were good credits. So after seven or eight months, they ended the experiment. They cancelled the credit cards of most of the customers.

And what were they left with? A couple of good customers and an amazing proprietary database. They had some training data that they could then feed through an algorithm, and that algorithm would say, here is what makes these good customers similar to one another, and here is what makes bad customers similar to one other. So if you want to find good credit risks, go look for people who look like this.

That's how they were able to scale and grow and become the largest credit card issuer in the world.

This is what's given rise to lots of new startups in the borrowing and lending space. All of them are using different types of machine learning models to identify good credit risks.

In my class , we also hear from people who work at peer-to-peer lending companies. What they really should be called are algorithmic lenders. They use data that other banks don't use. They're going beyond the traditional data sets and finding signals of credit-worthiness that the traditional banks don't look at.

One thing they could look at is your location data.

If a bank is tracking my location, they know something about me. They know that I went to work. Then I spent a couple of hours at LinkedIn headquarters. Then I head over to Google headquarters and then I hit Facebook headquarters for a couple hours in the afternoon.

Banks can use this information to revise my credit score up or down.

If we drill down into location data, we can figure out whom this person is meeting with. What room are they in inside the Facebook headquarters? What building are they in? Who are they sitting next to at that meeting?

If you don't have a unique, proprietary data source, you don't have a sustainable competitive advantage and you'll ultimately be commodified.

There's a company called Tala , and it works in countries like Kenya where people have no documentation: no banking history, no income history, no employment history, no housing history. And yet they can still lend money to these people because they download the Tala app, and the app scours their phone for data.

Kai-Fu Lee , a famous Chinese venture capitalist, visited Haas about two years ago, and he talked about a FinTech startup that he'd invested in. This startup used alternative data to evaluate credit. And he said that one of the most important signals that they had discovered of credit-worthiness was how people managed their battery life. You can track this because you have access to their phone data. People who let their batteries go all the way down to zero are bad credit risks compared to those who are topping off their batteries at 20 or 30 percent.

Even though it's absolutely essential and critical that every company use analytics, machine learning and data science, that alone cannot provide you with a competitive advantage. At the end of the day, that is a commodity. Anybody can learn how to do this, and anybody can hire away anybody else who knows how to do this.

Your competitive advantage has to come from your data—not from what you do with the data or how you use the data. I would argue that if you don't have a unique, proprietary data source, you don't have a sustainable competitive advantage and you'll ultimately be commodified.

Watch the entire video:

Stay up to date with courses and trends in Berkeley Haas Entrepreneurship

Deepen your skills, berkeley haas entrepreneurship, related posts.

Unleashing the Potential of Silicon Valley’s Entrepreneurial Ecosystem

Global Odyssey Journey at Berkeley

Jumping at the Chance to Study at Berkeley

View the discussion thread.

Targeting an untapped fintech market worth trillions: A conversation with Arta Finance’s Caesar Sengupta

As the eight cofounders of US- and Singapore-based Arta Finance got to know one another during their years together at Google, they recognized a massive market gap for investment services aimed at people like themselves: successful professionals who were doing well, but not well enough to access top-tier financial services. With a total addressable market in the trillions, they decided to launch a fintech start-up offering these elite services at scale, using a digital platform powered by AI. The venture quickly attracted prominent investors and venture capital (VC) funding in excess of $92 million, is already doing business in the United States, and will begin operating in Singapore by early 2024. In this episode of The Venture , Caesar Sengupta, CEO of Arta Finance, sat down with McKinsey’s Tomas Laboutka to discuss Arta’s mission to automate public-market investing and provide access to alternative assets by offering clients the services of a digital private bank and family office.

An edited transcript of the podcast follows. For more conversations on venture building, subscribe to the series on Apple Podcasts or Spotify .

Podcast transcript

Tomas Laboutka: Hi, Caesar. Welcome to The Venture. Great to have you.

Caesar Sengupta: Thanks so much for having me on. It’s wonderful to talk to you.

Tomas Laboutka: Caesar, you’ve had a really successful career at Google. For 15 years, you led Google Pay in India, and you were at the helm for the development of the Chromebooks. You could have kept going, but you decided to jump ship and go build Arta Finance. What’s the story behind this?

Caesar Sengupta: Great question, and I like how you’ve put it. When you find an opportunity that’s even bigger than what you’re working on, I think all things lead toward going and doing it. Arta, in many ways, originated out of some of our team’s experiences at Google. I have eight cofounders; we’re a rather weird company. And among the eight cofounders, we spent eight to 15 years working together and became friends.

As friends talk about finances and money, we realized there was a massive market gap for serving professionals who are doing well and will eventually have a much greater net worth. They are not quite at the $20 million to $25 million level, where a private bank would offer them great service, or at an even higher level where they would have their own family office.

These people were not being served, and we felt that need ourselves. And as we spoke to others, we realized there’s a huge global opportunity. We estimate several hundred million people worth trillions in the total addressable market (TAM) in need of a service like this, where we offer private banking or digital family office services to them at scale, using technology and AI.

Once we saw this opportunity, we felt like the timing was right, given where we were with technology, AI, and our careers. It was not quite in line with what Google does—Google is not a wealth manager—so we decided the best way to do this would be to start something up on our own, with a lot of support from friends and others at Google and elsewhere.

Leap by McKinsey

Leap by McKinsey works with established organizations to imagine, build, and scale new businesses—and develop the capabilities needed to do it again and again. We bring together a global network of experts to build dynamic, innovative businesses that can reinvigorate entire organizations.

Learn more about Leap by McKinsey .

Tomas Laboutka: What does Arta actually do?

Caesar Sengupta: If you think about a private bank, or a wealth manager, it helps you grow and protect your money. What Arta does is help you grow your assets through investments in public markets. We’ve essentially automated all kinds of public-market investing, ranging from very simple robo-advisers all the way to very sophisticated quant strategies you can personalize by industry. But if all you want to do is invest in a direct index fund in the S&P 500 and use tax-loss harvesting, we’ll let you do that, too.

A lot of people are only invested in public markets. But we think many professionals—just like the ultrarich—should be invested in alternative assets, like private equity, private credit, and private real estate ventures. We give people access to these investments, but at much lower amounts. Instead of the millions you’d have to normally invest, you can start with $25,000, or $100,000 in some cases. It makes these investments much more approachable.

We also offer structured products that are timed investments, so you don’t have to understand the complexities of derivatives, calls, and puts. We also offer tax-advantaged investing, structured through permanent life insurance policies, and set up trusts and estates as well. Essentially, we offer a full value proposition you would expect from a family office or a private bank. We offer that to our members and users via a digital platform, with experts and others providing support wherever needed.

Tomas Laboutka: You’re talking digitally enabled wealth management. There have been robo-advisers and the like for ten to 15 years. What’s the unique value proposition you bring to the table? And what role does AI play?

Caesar Sengupta: As you mentioned, robo-advisers have been around for the last ten years or so. They took a very simple concept of taking balanced portfolios that were rebalanced on a regular basis, and used technology to scale it. What we’ve done is brought it a decade or two into the future. Essentially, we’ve automated all kinds of public-market investments, and also given people access to alternative assets, but at much lower ticket sizes.

In many ways, we are doing what a private bank does, but using technology to scale those services. The way we think about it is, for all those people who started using robo-advisers ten years back, Arta is where you graduate to. Robo-advisers served you well. But as you start thinking about your financial future, and start thinking about scaling up, Arta is where you would come for a full-fledged digital private bank or digital family office.

We use AI in a couple of different ways. We started two years ago, before generative AI came around, so it was mainly machine learning. If you think about a bunch of these very sophisticated quant investment funds, we apply machine learning to some of those technologies and techniques. We can now offer these at an individualized level starting at $25,000.

With generative AI, the potential is so exciting, and the world is just opening up. We’re doing a bunch of work using large language models to enable thematic investing. Today, for example, if you wanted to invest in a particular theme you were excited about, you’d need a fairly sophisticated investment manager to set it up for you, or find an appropriate hedge fund.

But what if you could just type a theme into a system, which then generated assets to fit that theme? You could invest your money, the system would keep an eye on it for you, and all of this would be done with AI. We’re just starting to scratch the surface of generative AI, and I’m super excited about what it can do in the future.

Want to subscribe to The Venture ?

Tomas Laboutka: That is really fascinating. What are the capabilities you looked for in your cofounders and early employees? What gives you the right to not just play here, but win against the incumbents, against the other start-ups, or a competitor that might be thinking of entering this market?