Life on Delay: Making Peace with a StutterAn intimate, candid memoir about a lifelong struggle to speak. • “Soulful...Hendrickson provides a raw, intimate look at his life with a stutter. It’s a profoundly moving book that will reshape the way you think about people living with this condition.”— Esquire “Brims with empathy and honesty. It moved me in ways that I haven’t experienced before. It’s fantastic.”—Clint Smith, #1 New York Times best-selling author of How the Word Is Passed “I can’t remember the last time I read a book that made me want to both cry and cheer so much, often at the same time.”—Robert Kolker, #1 New York Times best-selling author of Hidden Valley Road In the fall of 2019, John Hendrickson wrote a groundbreaking story for The Atlantic about Joe Biden’s decades-long journey with stuttering, as well as his own. The article went viral, reaching readers around the world and altering the course of Hendrickson’s life. Overnight, he was forced to publicly confront an element of himself that still caused him great pain. He soon learned he wasn’t alone with his feelings: strangers who stutter began sending him their own personal stories, something that continues to this day. Now, in this reported memoir, Hendrickson takes us deep inside the mind and heart of a stutterer as he sets out to answer lingering questions about himself and his condition that he was often too afraid to ask. In Life on Delay , Hendrickson writes candidly about bullying, substance abuse, depression, isolation, and other issues stutterers like him face daily. He explores the intricate family dynamics surrounding his own stutter and revisits key people from his past in unguarded interviews. Readers get an over-the-shoulder view of his childhood; his career as a journalist, which once seemed impossible; and his search for a romantic partner. Along the way, Hendrickson guides us through the evolution of speech therapy, the controversial quest for a “magic pill” to end stuttering, and the burgeoning self-help movement within the stuttering community. Beyond his own experiences, he shares portraits of fellow stutterers who have changed his life, and he writes about a pioneering doctor who is upending the field of speech therapy. Life on Delay is an indelible account of perseverance, a soulful narrative about not giving up, and a glimpse into the process of making peace with our past and present selves. There are no customer reviews for this item yet. Classic Totes Tote bags and pouches in a variety of styles, sizes, and designs , plus mugs, bookmarks, and more! Shipping & Pickup We ship anywhere in the U.S. and orders of $75+ ship free via media mail! Why I Dread Saying My Own NameNearly every decision in my life has been shaped by my stutter.  This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic , Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here. O kay, here comes our waiter. I stare at the silverware. He clicks his pen. I’m always the last to order. Sometimes my mom tries to help me by tossing out what she thinks I want. “Cheeseburger, John?” “... Yyyy-uhh ... yyyueaah,” I force out. If I’m lucky, there are no follow-up questions. I’m rarely lucky. “And how would you like that cooked?” the waiter asks. “... ... ... ... Mmm-muh ... mmm-edium.” His face changes. I want it medium rare, but R ’s are hard, so I cut myself off. “And what kind of cheese?” Vowels are supposed to be easier, but I can never get through that first sound. I skip it altogether and go right for the consonant. “... Mmmmmuh ... ... muhm-merican.” Now our waiter understands that something is wrong. He shoots a nervous glance at my mom, who fires back a strained smile: Everything is fine. My son is fine . “Okay, next question,” he says with stilted laughter. “Curly fries or regular?” I want regular, but remember, R ’s are hard. Unfortunately C ’s are hard too. I’m trapped. I try a last-second word switch. Bad idea. “... Eeeeeeee-uh ... eeee-uh ... ... eeee-uh, eei-ther.” I close my menu and push it forward. “And to drink?” N early every decision in my life has been shaped by my struggle to speak. I’ve slinked away to the men’s room rather than say my name during introductions. I’ve stayed home to eat silently in front of the TV rather than struggle for a brief moment at a restaurant. I’ve let the house phone, and my cellphone, and my work phone ring and ring and ring rather than pick up to say hello. “... Huh ... huh ... huh ...” I can never get through the H . I understand that my stutter may make you cringe, laugh, recoil. I know my stutter can feel like a waste of time—of yours, of mine—and that it has the power to embarrass both of us. And I’ve begun to realize that the only way to understand its power is to talk about it. When I was first diagnosed with a speech impediment, in the fall of 1992, stuttering was viewed as something to be fixed, solved, cured—and fast!—before it’s too late. You don’t want your kid to grow up to be a stutterer . Read: An ‘absolute explosion’ of stuttering breakthroughs Few experts can even agree on the core stuttering “problem” —or how to effectively treat it, or how much to emphasize self-acceptance. Only since the turn of the millennium have scientists understood stuttering as a neurological disorder. But the research is still a bit of a mess. Some people will tell you that stuttering has to do with the language element of speech (turning our thoughts into words), while others believe that it’s more of a motor-control issue (telling our muscles how to form the sounds that make up those words). Five to 10 percent of all kids exhibit some form of disfluency. Many, like me, start to stutter between the ages of 2 and 5. For at least 75 percent of these kids, the issue won’t follow them into adulthood. But if you still stutter at age 10, you’re likely to stutter to some extent for the rest of your life. Stuttering is really an umbrella term used to describe a variety of hindrances in the course of saying a sentence. You probably know the classic stutter, that rapid-fire repetition: I have a st-st-st-st-stutter . But a stutter can also manifest as an unintended prolongation in the middle of a word: Do you want to go to the moooooo-ooo-oovies? Blocks are harder to explain. Blocking on a word yields a heavy, all-encompassing silence. Dead air on the radio. You push at the first letter with everything you have, but seconds tick by and you can’t produce a sound. Some blocks can go on for a minute or more. A bad block can make you feel like you’re going to pass out. Blocking is like trying to push two positively charged magnets together: You get close, really close, and you think they’re about to finally touch, but they never do. An immense pressure builds inside your chest. You gasp for air and start again. Remember: This is just one word . You may block on the next word too. Stuttering is partly a hereditary phenomenon. A little over a decade ago, the geneticist Dennis Drayna identified three gene mutations related to stuttered speech . We now know there are at least four “stuttering genes,” and more are likely to emerge in the coming years. But even the genetic aspect is murky: Stuttering isn’t passed down from parent to offspring in a clear dominant or recessive pattern . Even when it comes to identical twins, only one of them might stutter. The average speech-language pathologist, or SLP, is taught to treat multiple disorders, including enunciation challenges (think of someone who has trouble articulating an R sound) and swallowing issues. Yet many therapists are ill-equipped to handle a multilayered problem like stuttering. Of the roughly 150,000 SLPs in the United States, fewer than 150 are board-certified stuttering specialists. Even today, the medical community is divided over how to effectively help a person with a stutter. Many teachers don’t know how to deal with it either. It’s lonely. We’re told that 3 million Americans talk this way , but it doesn’t feel that common. You may have a sister or dad or grandparent who stutters, but in most cases, there’s only one kid in class who stutters: you . My kindergarten teacher, Ms. Bickford, was the first person to notice an issue with my speech. One afternoon she brought it up with my mom, who called our pediatrician, who referred her to a speech pathologist, who determined that I indeed had a problem but couldn’t offer much in the way of help. We waited for a while, hoping it would get better on its own. It got worse. My next option was to see the multipurpose therapist in the little room at school. I attended a Catholic elementary school in Washington, D.C. My parents could afford it only because my mom cut a deal with the principal: She’d volunteer as the substitute nurse in exchange for discounted tuition. On the days she showed up at school for duty, I’d head to the nurse’s office in the basement and eat lunch with her on a laminated placemat. I loved those afternoons. But to get down there to see her, I had to walk past the little room. I hated that room. Every time I entered that room, I felt like a failure. T here’s the knock. Kids stare as I stand to leave class. I walk down two flights of slate steps, turn the corner, and enter the little room. Everything in the little room is little: little table, little chair, little bookshelf. The decor is infantilizing. I’ve always been tall and gangly. At 7, my knees barely fit under the table. Most little rooms are peppered with the same five or 10 motivational posters: neon block letters, emphatic italics, maybe an iceberg or some other visual metaphor to explain your complex existence. This little room has a strange brown carpet that I stare into when the school therapist brings up my problem. She’s careful never to use the word stutter . Okay, let’s start from the beginning . There’s a stack of books on the table that are meant for people younger than me. Most sentences in these books are composed of one-syllable words. The vowels on the page are emphasized—underlined or in bold—a visual cue for me to stretch out that sound. Today we’re going to practice reading “ car as “cuuuuhhhh-aaarrr.” This is embarrassing. I know what car sounds like. I know how other people say car . Doing this exercise makes me feel like an idiot; not only do I have trouble speaking, but now it seems like I can’t read. Every time I block on the C , I sense a pinch of frustration from across the table. But maybe I’m imagining it. After enough attempts, I can read one whole sentence in a breathy, robotic monotone. “Thuuuhhhh cuuuuhhhh-aaarrrr drooooove faaaaaaast dowwwwwn thuuuuhhhhh rrroooaaaad.” For some reason, this way of speaking is considered a monumental success. I think the way I just read that is more embarrassing than my stutter. But I have to keep doing it, because it’s the Big Rule: Take your time . Read: Doctors are failing patients with disabilities Have you ever told someone who stutters to take their time? Next time you see them, ask how take your time feels. Take your time is a polite and loaded alternative to what you really mean, which is Please stop stuttering . Yet a distressing amount of speech therapy boils down to those three words. I n his influential 1956 book, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life , the sociologist Erving Goffman argued that in every social interaction, we are playing a part on an invisible stage. We want people to like us, to believe in us—no one wants to be labeled a fraud. Each time we speak, we may earn someone’s respect or lose it. We go to great lengths to sound smart, because we know that strong communicators are deemed worthy of esteem. Alex Trebek’s peerless ability to enunciate phrases during his 37-year run on Jeopardy transformed him into an icon. You can probably hear Trebek’s voice in your head right now: the clarity, the dignity, the confidence, the poise. America loved Trebek because, among other things, he was very good at saying words. Stutterers, by contrast, are often portrayed in pop culture as idiots, or liars, or simply incompetent. In the 1992 comedy My Cousin Vinny , people wince as the stuttering public defender blocks horribly throughout his opening statement. One juror’s jaw drops in shock. (Austin Pendleton, a stuttering actor, played the part to an almost vaudevillian degree—something he later regretted; he’s said the performance “haunts” him .) In Michael Bay’s 2001 soapy blockbuster, Pearl Harbor , crucial seconds are wasted on the morning of December 7, 1941, because Red, a soldier who stutters, can’t speak under pressure. Red stumbles around the barracks gritting his teeth, trying to force out the news: “The JJJJ-JJJaps are here!” He eventually says it, but it’s too late: Enemy gunfire pierces the room where his friends are sleeping. Thanks to Red and his stupid stutter, more people than necessary have now died at Pearl Harbor. A person who stutters spends their life racing against an internal clock. How long have I been talking? How long do I have until this person walks away? When you’re a kid, there’s a quieter, slower, more insidious ticking: Am I going to beat this before it’s too late? A fter I wrote about Joe Biden’s stutter in 2019, I began digging deeper into my own personal history with the disorder. One day I tracked down my second-grade teacher, Ms. Samson, and asked if she remembered anything about the way I spoke. From the January/February 2020 issue: Joe Biden’s stutter, and mine “I love the fact that you’re writing about this and putting it out there, because, gosh, from a teacher’s point of view, there’s not a lot—I mean, I wasn’t trained …” She searched for the words. “I wasn’t told how to handle this.” Back then, we didn’t have a cafeteria—we’d eat lunch in our classroom. Ms. Samson kept a little radio on the corner of her desk. At lunchtime, she’d tune in to WBIG Oldies 100, and the space in front of the whiteboard would become the second-grade dance floor. Each afternoon was like a kids’ wedding reception, and I couldn’t wait for it to start. I’d wolf down my turkey on white then push back my chair and dart to the front of the class. I knew that the station’s midday DJ, Kathy Whiteside, had queued up a total hit parade: the Four Tops, the Supremes, the Temptations, Sam and Dave. This was an ideal time to work on my Running Man, or to whip out an invisible towel and do the Twist. When Ms. Samson cranked her radio, my shoulders dropped and my lungs felt full. We looked like doofuses up there in our khaki pants or plaid skirts, but we were a unit of doofuses. This has special meaning when you’re the class stutterer. An hour ago I was flustered and out of breath, pushing and pulling at a missing word, feeling that familiar sweat drip down the back of my neck. Now I’m just another kid doing the swim to “Under the Boardwalk.” One day I sashay over to Michelle B. We giggle at each other. A new song starts. Jackie Wilson’s voice lifts me higher and higher. Then the music stops and I crash back to Earth. “Your face would turn blotchy. Really, really red,” Ms. Samson told me. “You would cut your comments short because it was just too much work, or you figured, I lost the audience . But your impulse to participate—that’s how I knew: He’s thinking. He’s thinking and he wants to talk . That was the hardest part.” This is the tension that stutterers live with: Is it better for me to speak and potentially embarrass myself, or to shut down and say nothing at all? Neither approach yields happiness. As a young stutterer, you start to pick up little tricks to force out words. Specifically, you start moving other parts of your body when your speech breaks down. I still do this, and I hate it. I don’t know why it works, but it does: When I’m caught on a word, I can get through a jammed sound much faster if I wiggle my right foot. Blocked on that B ? Bounce your knee! Unfortunately these secondary behaviors quickly become muscle memory. Sometimes they morph into tics. They also have diminishing returns: A subtle rub of your hands in January won’t have the same conquering effect on a block in February. So that means you’re stuttering for seconds at a time and moving other parts of your body like a weirdo. It’s exhausting. The curse of these secondary behaviors is that they can be just as uncomfortable as your stutter. Eventually, I stopped going to the little room and began seeing a new speech therapist once a week at a clinic after school. Every Wednesday, Dr. Tom would bound into the waiting room and greet me with a high five. He grew up in a big Mississippi family and spoke with a warm country drawl. He oozed patience. This arrangement was immediately better: no more leaving class, no more kids’ books. Dr. Tom’s philosophy was to pair fluency-shaping strategies with things I’d encounter in my daily life, like board games. We tore through hours of Trouble, pressing down on the translucent dome to make the imprisoned die pop. As I moved my blue men around the board, I’d practice techniques to try to smooth out my speech. If we read passages out loud, we’d use my actual homework. Dr. Tom’s go-to technique was a popular strategy called “easy onset.” It’s a spiritual cousin to “cuuuuhhhh-aaarrr,” but with more emphasis on the first sound of a word. The objective is to ease into the opening letter with a light touch, stretch the vowel, then shorten your exaggeration over time. No two stutterers struggle with the same collection of sounds, but every stutterer is haunted by specific vowels and consonant clusters. Many who stutter come to dread the act of saying their own name. People say their names more frequently than any other proper noun, after all, and stutterers tend to be extra disfluent when we meet new people. My jaw locks when I go to form the J in John . I typically enter a long, painful block, then bark out the word at full volume: … … … … … … … … JOHN! Sometimes my J manifests as a rapid repetition, like a machine gun, or a Buick that won’t start: Jjjjjjjjjjjjjjohn . I’ve wasted whole afternoons fantasizing about what life might be like with another name. Why didn’t my parents choose Michael? All I’d have to do is thread that M to the I . The second syllable plops out, like a raindrop on a creek. Michael. I’ve said Michael so many times that it’s lost all meaning: Michael, Michael , Miiiichael. (Of course, if I were Michael, I’d probably block on the M .) Stuttering is an invisible disability until the moment it manifests. To stutter is to make hundreds of awful first impressions. And an awkward exchange between two people affects not just the person being awkward, but the person forced to deal with said awkwardness. A stutterer may enter a room full of “normal” people and temporarily pass as a fellow “normal,” but the moment they open their mouth—the second that jagged speech hits another set of eyes and ears—it’s over. As Erving Goffman notes: “At such moments the individual whose presentation has been discredited may feel ashamed while the others present may feel hostile, and all the participants may come to feel ill at ease, nonplussed, out of countenance, embarrassed, experiencing the kind of anomy that is generated when the minute social system of face-to-face interaction breaks down.” One phrase leaps out at me there: “may feel ashamed.” This assumes that the shame will pass. I wish I could pinpoint the moment when shame changed from something that periodically washed over me to something I began lugging around every day like a backpack. S ome days Dr. Tom and I would sit on the floor in front of a big mirror and study the movements of our mouths. This was harder than it sounds. The mirror ran the length of the wall, and there was nowhere else to look: I had to watch myself stutter. One day I sat close enough, with my eyes just a few inches away from the surface, that I could make out shadowy figures in a dark room on the other side of it. Discovering this was a little like learning the truth about Santa Claus: You mean everyone knows but me? There was a hidden microphone somewhere in our room. The space on the other side had little speakers to transmit our voices. (You’ve seen this on a million cop shows.) I asked Dr. Tom who was in there watching us, and he told me: Occasionally, graduate students observed our sessions, and that was a good thing, because we were teaching them how to be therapists themselves. Other days, the shadowy figure was my mom. I don’t blame her for watching. That’s what the doctors told her to do. I have sympathy for the parents of children who stutter. You want nothing more than for your kid to live a happy and successful life, and this new thing, this ugly problem, seems to threaten that. There’s also the aforementioned race against time: With each passing year, true fluency becomes harder to attain. Many health insurers don’t cover speech therapy, preventing people with limited funds from having the chance to work with experts. And yet, even many parents who have the means—those who dutifully shuttle their kids to appointments—leave with flawed advice: Remind them to use their techniques! Tell them to take their time! We stutterers anticipate our blocks well before they occur. We know how our brains and lungs and lips confront every letter of the alphabet. We know what we look like, what we sound like, what we make shared spaces feel like. We know that our stutter hasn’t gotten better, and that maybe it’s getting worse. We sense that most nights you, Mom and Dad, pray for it to go away. We know you believe you’re helping. We don’t know how else to tell you this: You’re not. When a person of authority tells a young stutterer to “use your techniques,” they are confirming the stutterer’s worst fear: No one is listening to what you say, only how you say it. Enough of this makes you not want to talk at all. Fluency techniques may work in a therapy room, but, in most cases, they’re extremely hard to deploy in the real world. Speaking like a robot is not natural. Read: Learning to love stuttering “I could see you using strategies—you were doing things with your breath,” Ms. Samson told me. “And probably you had practiced whatever it was so much, and just couldn’t live up to what you knew you could do. I could see the defeat. You would put your head down and sort of walk back to your desk.” What would it take for me to let go of that feeling? More than two decades later, I finally had a glimpse of an answer. If I was going to make peace with the shame of stuttering, I’d have to abandon the illusion that natural fluency might one day come, that my “two voices” would magically merge. I’ll always have a voice in my head that reads this sentence, and a much different voice that reads it out loud. I don’t like that fact about myself. But I don’t have to keep fighting it. This article has been adapted from John Hendrickson’s forthcoming book, Life on Delay: Making Peace With a Stutter.  When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic. Find anything you save across the site in your account Briefly Noted Palo Alto , by Malcolm Harris (Little, Brown) . A useful counter to Silicon Valley’s self-mythologizing, this history of Palo Alto begins in the late nineteenth century, with the state-funded genocide of Alta Indians by settlers and the coming of the railroad, which led, via the fortune of Leland Stanford, to the establishment of Stanford University (“the pseudostate governing Palo Alto”). Harris highlights the city’s connection to the horrors of napalm, Japanese internment, and eugenics, and notes that many of the early tech companies in the area began “in the space between the military and academia.” Their success, he writes, “represents the triumph of software over hardware, of advertising over production, of monopoly over competition, of capital over labor.”  Life on Delay , by John Hendrickson (Knopf) . “Nearly every decision in my life has been shaped by my struggle to speak,” Hendrickson writes in this moving exploration of stuttering. A stutterer since childhood, he spent years in therapy, waiting in vain “for this strange thing to exit my body.” Many stutterers do largely overcome their impediment (including the actress Emily Blunt, whom Hendrickson interviews), but others never do. Why this is so remains a neuroscientific mystery. Hendrickson presents a wealth of fascinating detail (virtually all stutterers, for instance, can sing and recite fluently), but the real draw lies in his account of his personal experiences, which convey something essential about the challenge of being human. The Best Books of 2023 Read our reviews of the year’s notable new fiction and nonfiction.  The Sun Walks Down , by Fiona McFarlane (Farrar, Straus & Giroux) . Set in rural Australia in the late nineteenth century, this ambitious novel assembles a band of characters—including a white farmer, an Aboriginal farmhand, and a Swedish painter—who are drawn together by the disappearance, in a dust storm, of a six-year-old boy. McFarlane’s figures emerge in intricate detail, defined by their petty desires, their moral imperfections, and their relationship both to the cataclysm of colonization and to the grandiosity of the landscape and the sun, which, for some, takes on near-divine significance. “There’s no way to describe these skies,” the painter writes to a colleague in Europe. “If I had to try, I would say that they are light shipwrecked by dark.”  Collected Works , by Lydia Sandgren, translated from the Swedish by Agnes Broomé (Astra) . Poised at the intersection of life and art, reality and imagination, this novel blends the thrill of mystery with the curiosity and depth of philosophical inquiry. Fifteen years after Cecilia Berg goes missing, her husband, Martin, is haunted by memories of their shared youthful intellectual ambitions, by the artistic struggles of their friend Gustav, and by professional and family worries. Narrated alternately by Martin and his daughter, Rakel, the novel refracts Cecilia’s absence through the literary and artistic concerns of those who remain. Rakel reflects that a picture “is always created at the expense of another picture.” She says, “The Cecilia of Gustav’s paintings pushed another Cecilia out of the frame. . . . And who was she?” Books & FictionBy signing up, you agree to our User Agreement and Privacy Policy & Cookie Statement . This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.  By Merve Emre  By Alex Ross More From ForbesBook review: sebastian junger’s ‘in my time of dying’. - Share to Facebook

- Share to Twitter

- Share to Linkedin

Book cover, In My Time of Dyiing Why would a war correspondent prove to be an excellent guide to quantum theory? Sebastian Junger’s success in In My Time of Dying: How I Came Face-to Face with the Idea of an Afterlife (Simon & Schuster, May 2024) may lie in his urgency. I’ve never found quantum theory easy to understand intuitively because the physics it describes are not those of the visible world. For example, in the visible world, I know that a tether ball circumventing a pole will follow either a circular or elliptical path. If given the right information (force applied, angle of application, weight of ball, length of rope, wind resistance, and maybe a few other factors), anyone with a reasonably-informed understanding of math can calculate the ball’s path and exactly where it will be along it at any given moment. Paths of momentum are less predictable inside atoms. As Werner Heisenberg made clear with his uncertainty principle, when circumventing the neutron of an atom, the position of an electron can only be expressed in terms of the probability of finding it at any given point. There is no certainty. And then there’s the matter of “spin.” Decades ago, my high school Chemistry teacher patiently explained to my class that, as electrons orbit nuclei, they “spin” positively or negatively. As it turns out, electrons don’t spin . Scientists use the terms “spinning” or “spin angular momentum” to refer to electrons’ magnetic pull. Even the use of the term “momentum” may be misleading, as “spin angular momentum” may have nothing to do with movement of any kind. (And, BTW, given how small electrons are, in order to gain their magnetic effects from spin, they would have to spin faster than the speed of light .)  In My Time of DyingAuthor Sebastian Junger is a well-published nonfiction author and a former war correspondent. In In My Time of Dying, he discusses quantum theory from a historical perspective rather than from a mechanical one. As he explains, Nobel Prize-winning theoretical physicist Richard Feynman is reputed to have once said, “If you think you understand quantum mechanics [quantum theory expressed mathematically], you don’t understand quantum mechanics.” Taking a historical rather a mathematical tack, Junger infuses the discoveries of Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Louis de Broglie, Ludwig Boltzmann, Werner Heisenberg, and Erwin Schrödinger with urgency. This is largely because his historical perspective is wrapped in the real reason for his book’s existence: against all odds, Junger survived an out-of-the-blue medical emergency that culminated in a near death experience (NDE). With all of the suspense of a war report, In My Time of Dying relates the emotion and details of the emergency. At the same time, it looks to quantum theory for clues about the NDE. Best High-Yield Savings Accounts Of 2024Best 5% interest savings accounts of 2024. Author Sebastian Junger. Granted, there are books aplenty about NDEs and “visits” from dead relatives and friends. Some lean into metaphysics. Some dabble in a cloud of ideas vaguely related to quantum theory. The derisive term often used for such books is “woo-woo.” Junger’s book doesn’t “woo.” It describes in nearly cinematic detail his aneurysm at the age of 56. He lost ten pints of blood. His wife, whom he outweighed by 50 pounds, had to get him out of the woods to their house and into an ambulance even though a storm had washed out both the land lines and cell service. It took an hour and a half from the time the emergency started to when Junger arrived at the hospsital. During four hours and twenty minutes of surgery he got no general anesthetic. Too fragile to withstand it, he floated in and out of consciousness, sometimes joking through the pain with the medical team. Yes, these passages of the book read like war reporting. Other passages — not so much, and that’s good, too According to Junger, his father showed up during his surgery and assured him that there was no need to be afraid of what would come next. That makes at least some sense, assuming that his father was scrubbed for the OR. But he’d been dead for 11 years. While Junger’s father talked soothingly to him, he stood at the rim of a yawning black emptiness that had formed on the left side of Junger’s field of vision. The void pulled unrelentingly at Junger while his father spoke gently and Junger urged the surgical team to please work faster. The next morning, according to Junger, a nurse told him, “No one can believe you’re alive.” Indeed, he is alive and well and living in New York City and Hyannis with his wife and two little girls. So what does a tough guy journalist — someone who is at least a little inured to death, having flirted with it as a thrill-seeking kid, having dodged it on the battlefield, and having seen friends blown apart in battle — do with a medical emergency and NDE experience like that? In general, journalists try to make sense of things. Junger’s attempts to make sense of his medical emergency are very nice lessons in physiology and human anatomy. When he delves into the development of quantum theory, the book really shines. Again, it’s good reporting; it’s detailed and fun, and it sometimes relieves intense emotion by employing a bit of ironic distance. People have personalities and motivations. The pre-World War II physicists, “a group of men not known for good looks or fashion sense,” are mostly Eastern European refugees who drink too much. Some behave appallingly. (Schrödinger, in his 40s, became sexually involved with Junger’s own aunt while she was a young teenager. His diary counted her among the great loves his life. I wrote about this for Forbes.com in “Schrödinger’s Pedophilia: The Cat Is Out of the Bag (Box).”) To his credit, Junger never blatantly uses quantum theory to speculate about how his dead father could have visited him during his surgery. He spreads no “good news, we’re all going to live forever!” gospels. Rather, his passages about his father and his brush with death read like the notes-to-self of a reporter who has been staring for a long time into a glorious sun. His eyes are burnt. Crisp. He is changed. “It’s an open question whether a full and unaverted look at death crushes the human psyche or liberates it. One could say that it’s the small ambitions of life that shred our souls, and that if we’re lucky enough to glimpse the gargoyles of our final descent and make it back alive, we are truly saved. Every object is a miracle compared to nothingness and every moment an infinity when correctly understood to be all we’ll ever get. Religion does its best to impart this through a lifetime of devotion, but one good look at death might be all you need.” Junger may not directly point out possible links between quantum theory and NDE, but he braids the fabrics of his story so tightly that it’s easy for readers to draw their own conclusions. In Junger’s march through the history of early 20th century physics, he explains that electrons are not necessarily in any one place at any one time. They may even occupy all places along their orbit simultaneously as a statistical probability. ( Schrödinger .) They can even exist in multiple states simultaneously. ( Schrödinger again, and too bad for his cat ). Any subatomic particles that have momentrum and energy can be entangled, meaning that what happens to one proton, neutron, photon, or electron happens to its entangled twin even when they are miles — or, theoretically, a universe — apart. (This idea originated with Albert Einstein and his two postdoctoral research associates, Bors Podolsky and Nathan Rosen , though they didn’t use the term “entanglement.”) In My Time of Dying is a short book. You can read about quantum entanglement almost in the same deep breath in which you read about Junger’s father’s visit to the OR. While Junger refuses to tie up loose ends about NDEs, he graciously provides some standard, no-nonsense ideas. For example, maybe they are temporal lobe seizures caused by the stress of impending death. Quantum physics has raised questions about the extent to which reality can ever be known. In his economically-written but utterly expansive book, Junger wonders whether, if infinitesimally small matter have confounding “talents,” maybe so do the bigger objects and beings that they comprise. Humans are entirely atoms, nothing more, nothing less. Which is to say that maybe humans are weird, too, dead or alive. Publisher: Simon & Schuster (May 21, 2024) Length: 176 pages ISBN 9781668050835 List price: $27.99  - Editorial Standards

- Reprints & Permissions

Join The ConversationOne Community. Many Voices. Create a free account to share your thoughts. Forbes Community GuidelinesOur community is about connecting people through open and thoughtful conversations. We want our readers to share their views and exchange ideas and facts in a safe space. In order to do so, please follow the posting rules in our site's Terms of Service. We've summarized some of those key rules below. Simply put, keep it civil. Your post will be rejected if we notice that it seems to contain: - False or intentionally out-of-context or misleading information

- Insults, profanity, incoherent, obscene or inflammatory language or threats of any kind

- Attacks on the identity of other commenters or the article's author

- Content that otherwise violates our site's terms.

User accounts will be blocked if we notice or believe that users are engaged in: - Continuous attempts to re-post comments that have been previously moderated/rejected

- Racist, sexist, homophobic or other discriminatory comments

- Attempts or tactics that put the site security at risk

- Actions that otherwise violate our site's terms.

So, how can you be a power user? - Stay on topic and share your insights

- Feel free to be clear and thoughtful to get your point across

- ‘Like’ or ‘Dislike’ to show your point of view.

- Protect your community.

- Use the report tool to alert us when someone breaks the rules.

Thanks for reading our community guidelines. Please read the full list of posting rules found in our site's Terms of Service.  Color Scheme - Use system setting

- Light theme

Library waives damaged-book fees in exchange for pet, baby photos We like to think our furry friends are always very good boys and girls, but sometimes they chew on things they shouldn’t: furniture, clothing, large sums of cash and books. Lots of books. Libraries across the country regularly receive returned books with a love bite or two. The Middleton Public Library in Middleton, Wisconsin, is no exception. “We totally get that accidents happen,” said Katharine Clark, the deputy director of the library. In the past, people who returned damaged books would be responsible for funding a replacement. “Sometimes they feel nervous about coming to tell us,” Clark said. “We don’t want a damaged thing to wreck their relationship with the library.” So, Middleton Public Library staff hatched a plan. They created a new policy. Damaged book charges are waived under one condition: the patron must submit a photo of the cat, dog (or sometimes child) behind the transgression. “We just thought it would be a fun little thing that we could do at our library,” said Clark, adding that they were inspired by the Worcester Public Library’s “March Meowness” initiative, which forgave fines for damaged or lost library books if patrons sent in a photo of a cat – theirs or someone else’s. “It’s really showing a fun side to the library,” said Clark, adding that when they began the policy, they decided to post the pet photos on social media, with the approval of the person who sent them. “We understand that library materials can look delicious to pets and young children, so the Middleton Public Library has unveiled a new policy for fatally chomped materials: in lieu of payment for the item, we would like to offer you the option of submitting a photo of the beloved culprit,” the library wrote in its first Facebook post about the policy, featuring a dog named Daisy who chewed on “The Guest” by B.A. Paris. Enthusiastic comments poured in. “resists temptation to feed library books to my cat just so I can share pics” someone wrote. Clark said she didn’t anticipate the library’s new policy would take off, but sure enough, by the second post – about an American water spaniel named Quik who devoured a novel – thousands of people started sharing it. The post was liked more than 18,000 times. “For context, we’re normally thrilled to see a few dozen likes. It’s been fascinating to watch how a post gains virality,” said Rebecca Light, a librarian who works on the library’s social media team. “We’ve seen comments, shares and follows from all over the world.” Since unveiling the policy at the end of April, four canine culprits have come forward – including Stephanie Thomsen’s 1-year-old Australian labradoodle, Sky. “He chews up shoes quite a bit. He has never gone after a book,” Thomsen said. That changed a few weeks ago, when Sky was sitting on her bed and Thomsen left the room for a few minutes. She came back, and he was gnawing at the edge of “Iron Flame” by Rebecca Yarros. When Thomsen went to return the damaged book, she expected to pay for it. But the library told her she could send a photo of her dog instead. “It’s showing grace and understanding,” she said. “Also, this is a way to promote libraries being fun and welcoming.” Library patron Jean Ligocki recently discovered her borrowed book “Lifelong Yoga” had been chomped. There were two suspects. “We didn’t know if it was Ward or Ned, but knowing their personalities, we think Ward is the culprit,” said Ligocki, noting that she has two goldendoodles at home – Ned, 8, and Ward, 7. “Ward has quite the appetite and likes to chew things.” Ligocki was happy to learn of the library’s new policy – which she said is both amusing and equitable. “Anything that keeps access open to people who might be disadvantaged and might not have the money to pay for a damaged book fee, I love that,” she said. The library plans to keep the policy going indefinitely. “People love their pets, and people love reading,” Clark said. “This marries two things that people love.” Hydropower is ready to step up to the plate against summer heatSummer is nearly here and the Northwest has sprung to life as the days have grown longer and warmer.  - Kindle Store

- Kindle eBooks

- Biographies & Memoirs

| Print List Price: | $17.00 | | Kindle Price: | $12.99 Save $4.01 (24%) | Random House LLC

Price set by seller. | Promotions apply when you purchase These promotions will be applied to this item: Some promotions may be combined; others are not eligible to be combined with other offers. For details, please see the Terms & Conditions associated with these promotions. Audiobook Price: $14.47 $14.47 Save: $1.48 $1.48 (10%) Buy for othersBuying and sending ebooks to others. - Select quantity

- Buy and send eBooks

- Recipients can read on any device

These ebooks can only be redeemed by recipients in the US. Redemption links and eBooks cannot be resold. Sorry, there was a problem. Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required . Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web. Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.  Image Unavailable - To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author Life on Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter Kindle Edition - Print length 260 pages

- Language English

- Sticky notes On Kindle Scribe

- Publisher Vintage

- Publication date January 17, 2023

- File size 945 KB

- Page Flip Enabled

- Word Wise Enabled

- Enhanced typesetting Enabled

- See all details

Customers who bought this item also bought Get to know this bookWhat's it about, amazon editors say....  Beautiful! You will shake your fist in anger at the establishment and get your pom-poms out to cheer on the stutterers.  From the PublisherEditorial ReviewsAbout the author, product details. - ASIN : B09X3TWND5

- Publisher : Vintage (January 17, 2023)

- Publication date : January 17, 2023

- Language : English

- File size : 945 KB

- Text-to-Speech : Enabled

- Screen Reader : Supported

- Enhanced typesetting : Enabled

- X-Ray : Enabled

- Word Wise : Enabled

- Sticky notes : On Kindle Scribe

- Print length : 260 pages

- #52 in Speech & Pronunciation

- #295 in Speech

- #424 in Biographies of Medical Professionals (Kindle Store)

About the authorJohn hendrickson. Discover more of the author’s books, see similar authors, read author blogs and more Products related to this item .sp_detail2_sponsored_label { color: #555555; font-size: 11px; } .sp_detail2_info_icon { width: 11px; vertical-align: text-bottom; fill: #969696; } .sp_info_link { text-decoration:none !important; } #sp_detail2_hide_feedback_string { display: none; } .sp_detail2_sponsored_label:hover { color: #111111; } .sp_detail2_sponsored_label:hover .sp_detail2_info_icon { fill: #555555; } Sponsored (function(f) {var _np=(window.P._namespace("FirebirdSpRendering"));if(_np.guardFatal){_np.guardFatal(f)(_np);}else{f(_np);}}(function(P) { P.when("A", "a-carousel-framework", "a-modal").execute(function(A, CF, AM) { var DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX = 'adFeedback:desktop:multiAsinAF:sp_detail2'; A.declarative('sp_detail2_feedback-action', 'click', function(event) { var MODAL_NAME_PREFIX = 'multi_af_modal_'; var MODAL_CLASS_PREFIX = 'multi-af-modal-'; var BASE_16 = 16; var UID_START_INDEX = 2; var uniqueIdentifier = Math.random().toString(BASE_16).substr(UID_START_INDEX); var modalName = MODAL_NAME_PREFIX + "sp_detail2" + uniqueIdentifier; var modalClass = MODAL_CLASS_PREFIX + "sp_detail2" + uniqueIdentifier; initModal(modalName, modalClass); removeModalOnClose(modalName); }); function initModal (modalName, modalClass) { var trigger = A.$(' '); var initialContent = ' ' + ' ' + ' '; var HEADER_STRING = "Leave feedback"; if (false) { HEADER_STRING = "Ad information and options"; } var modalInstance = AM.create(trigger, { 'content': initialContent, 'header': HEADER_STRING, 'name': modalName }); modalInstance.show(); var serializedPayload = generatePayload(modalName); A.$.ajax({ url: "/af/multi-creative/feedback-form", type: 'POST', data: serializedPayload, headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json', 'Accept': 'application/json'}, success: function(response) { if (!response) { return; } modalInstance.update(response); var successMetric = DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX + ":formDisplayed"; if (window.ue && window.ue.count) { window.ue.count(successMetric, (window.ue.count(successMetric) || 0) + 1); } }, error: function(err) { var errorText = 'Feedback Form get failed with error: ' + err; var errorMetric = DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX + ':error'; P.log(errorText, 'FATAL', DESKTOP_METRIC_PREFIX); if (window.ue && window.ue.count) { window.ue.count(errorMetric, (window.ue.count(errorMetric) || 0) + 1); } modalInstance.update(' ' + "Error loading ad feedback form." + ' '); } }); return modalInstance; } function removeModalOnClose (modalName) { A.on('a:popover:afterHide:' + modalName, function removeModal () { AM.remove(modalName); }); } function generatePayload(modalName) { var carousel = CF.getCarousel(document.getElementById("sp_detail2")); var EMPTY_CARD_CLASS = "a-carousel-card-empty"; if (!carousel) { return; } var adPlacementMetaData = carousel.dom.$carousel.context.getAttribute("data-ad-placement-metadata"); var adDetailsList = []; if (adPlacementMetaData == "") { return; } carousel.dom.$carousel.children("li").not("." + EMPTY_CARD_CLASS).each(function (idx, item) { var divs = item.getElementsByTagName("div"); var adFeedbackDetails; for (var i = 0; i Customer reviewsCustomer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them. To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness. - Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United StatesThere was a problem filtering reviews right now. please try again later..  Top reviews from other countries Report an issue- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Amazon Assistant

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Book Reviews'forgotten on sunday' evokes the heartwarming whimsy of the movie 'amélie'. Heller McAlpin  Europa Editions hide caption Valérie Perrin's novels have been enormously popular in her native France, and it's no wonder. Forgotten on Sunday, her third to be translated into English, evokes something of the heartwarming whimsy of the 2001 movie, Amélie, which gets a shout-out in the book. A recurrent theme in Perrin's novels is the life-changing magic of friendships across generations. Her latest is narrated by a charming misfit, a 21-year-old nurse's assistant at a retirement home in her tiny village. Justine Neige is so interested in her patients' lives that she often stays after her shift to hold their hands and talk to them. She announces on the second page: "I love two things in life: music and the elderly." Like Violette Toussaint, the caretaker of a cemetery in Perrin's Fresh Water for Flowers, Justine has an unusual gift for empathy that enables her to elicit confidences from the people she encounters in her work. Despite the sadness of some of the stories, including their own, both of Perrin's idiosyncratic heroines remain obstinate optimists and romantics. Justine has a favorite patient, 96-year-old Hélène Hel, a retired seamstress and bistro owner whose life story she records in a blue notebook. It's a love story disrupted by the German occupation of France, deportation to Buchenwald, and years lost to amnesia -- all frequent subjects in French literature. Unusually, dyslexia and Braille play into it. So do blue eyes. A seagull is asked to carry more symbolic weight than in Chekhov. (Don't ask.) As Justine pieces together Hélène's tragic history, relayed "in jigsaw-puzzle form," she also strives to locate the missing pieces regarding the tragedy that changed her life: the death of her parents in a car accident on the way to a baptism when she was four. Also killed in the 1996 crash were her uncle and aunt -- her father's identical twin brother and his beautiful Swedish wife -- who left behind 2-year-old Jules. The two orphaned cousins were raised by their grim grandparents, who refuse to discuss the crash. "It can't be said that they're nasty to us, merely absent," Justine comments. We eventually learn why. Justine, seemingly without ambition or wanderlust, went straight from high school to her ill-paid job at The Hydrangeas. Jules, on the other hand, plans to hightail it to Paris to study architecture the minute he finishes his baccalaureate. "For Jules, succeeding in life means leaving Milly," Justine observes. (It also meant cutting off his Swedish maternal grandparents when he was ten, after "they made insinuations" about his parentage.) He cannot understand Justine's devotion to her job or to their dying little village. "Jules tells me I'm too naively sentimental, that I think like a novel," she writes. Of course he's right, but of course that's Justine's charm. Forgotten on Sunday is comfortably translated by Hildegarde Serle, though I wish she had left some of the original French for color, such as crèpes instead of pancakes and toilette instead of the ungainly ablutions. The title refers to the nursing home inhabitants who are unvisited -- or forgotten -- even on Sundays. In French, it's Les Oubliés du Dimanche, with the definite article: the forgotten. Most of these neglected elders, Justine notes pointedly, "have only sons." (A better word order: "only have sons" -- meaning no daughters, who, she observes, are far more attentive to their parents.) This intricately plotted novel features more twisted strands than a French braid, with several flyaway mysteries that Perrin ultimately tames. Primary among them: Who has been calling the families of forgotten patients on Saturday nights and telling them their loved ones have died, forcing them to show up to a big surprise (and the delight of their elders) on Sunday morning? Despite being "like an Agatha Christie with no dead body," the case triggers a police investigation by the same lazy, unpleasant detective who, it turns out, investigated Justine's parents' accident. Another question that keeps readers turning pages: Who's the thoughtful, unbelievably forbearing guy Justine sometimes spends the night with after dancing at the Paradise Club -- a guy whose calls she never bothers to return and whose name she never bothers to learn? Forgotten on Sunday is a pain au chocolat of a book -- flaky but buttery, with a sweet center. This sentimental soul-soother is further sweetened by the knowledge that several of the characters are named, at least in part, after Perrin's grandparents, including Helene Hel's lost-and-found great love, Lucien Perrin. Advertisement Supported by A Tribal Eviction, a Blood Secret and the Knotty Questions of BelongingIn “Fire Exit,” a white man raised on a reservation wrestles with whether he should reveal to his daughter the complications of her heritage.  By Esi Edugyan Esi Edugyan is the author of “Half-Blood Blues” and “Washington Black.” - Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission. FIRE EXIT, by Morgan Talty There’s a lovely clarity to Morgan Talty’s debut novel, “Fire Exit.” He is especially bracing about the losses that can accrue with time. When we first meet Charles Lamosway, Talty’s middle-aged protagonist, he is at a crossroads: Mental illness and dementia threaten to engulf his mother; he has been evicted from the Native reservation where he has lived all his life; and, most painful of all, his daughter doesn’t know him. That last problem, at least, is within his power to change. He strongly feels “she needed to know that her blood was her blood,” to be aware of her “connection to a past time and people.” Like Talty’s 2022 story collection, “Night of the Living Rez,” this novel does not shy away from blistering questions of belonging and identity, but rather leans into them, in taut, often precise prose. What, exactly, does it mean to have ties to a community, but remain an outsider? What belonging can we claim for ourselves? Who gets to decide what we are? Such questions will become matters of life and death for Charles, when things eventually come to a head in the novel’s startling climax. Charles is white by blood, but Penobscot by culture, having been raised on the tribe’s reservation by a white mother and a Penobscot stepfather. After the passing of the Maine Indian Claims Settlement Act, in 1980, he — being white, and not having married into the tribe — is asked to leave. He finds himself living across the river, in full view of what he has lost. It’s a calculated choice. He has a grown daughter, Elizabeth, with a Penobscot woman named Mary. She’d left Charles after learning she was pregnant. In the hopes that the baby would grow up connected to her culture, and qualify for tribal enrollment, Mary had insisted that she and Charles lie, telling Elizabeth that her Penobscot stepfather is her biological father. And so, Elizabeth is raised on the reservation without any knowledge of Charles, believing herself to be fully Indigenous. Charles wants to give his daughter the gift of knowing her true heritage. But as he’s about to learn, forcing unwanted awareness on a vulnerable person can be a disastrous act. Though Talty’s subject matter is often dark — exploring alcoholism, abandonment, physical violence, emotional abuse — he has a light touch, and draws us in with a calm intimacy. There is much to admire. In one piercing scene, Charles visits a friend’s violent father in the hospital, observing: “I could see the veins lining his skin … and I could not — and I still cannot — help but feel sorry for him, even though I disliked him the most out of anybody I had met in my life.” We are having trouble retrieving the article content. Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings. Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times. Thank you for your patience while we verify access. Already a subscriber? Log in . Want all of The Times? Subscribe .  |

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

John Hendrickson's memoir "Life on Delay" recounts his experience with this poorly understood neurological disorder, tracing an arc from frustration and isolation to acceptance and community.

The dramatic tension in the book is mainly derived from Hendrickson's fraught relationship with his brother, who bullied the author as a child, mocking his stutter mercilessly. This appealing and perceptive memoir takes an unsentimental look at life with a speech disorder.

Read 207 reviews from the world's largest community for readers. An intimate, candid memoir about a lifelong struggle to speak. ... Life on Delay is an indelible account of perseverance, a soulful narrative about not giving up, ... The book is full of many such dichotomies; for example, Hendrickson describes how speech therapies meant to curb ...

His new memoir, "Life on Delay," details his struggle with stuttering. SCOTT SIMON, HOST: I'm going to interview a writer who begins his new book with these words. Nearly every decision in my life ...

A lifelong stutterer, Hendrickson uses "Life On Delay" to communicate the immense impact of spoken word. Hendrickson harnesses words every day as a staff writer at The Atlantic. After ...

John Hendrickson's Life on Delay: Making Peace With a Stutter is the kind of memoir that educates, endears, impacts and devastates, often simultaneously. A journalist and senior editor at The Atlantic, Hendrickson is best known for his 2019 interview with then-presidential candidate Joe Biden. The resulting piece had little to do with politics.

In 'Life on Delay,' John Hendrickson recalls how he overcame the resentment and fear that his disfluency caused. Review by Anna Leahy. January 20, 2023 at 7:00 a.m. EST. "I know my stutter ...

Life on Delay is an indelible account of perseverance, a soulful narrative about not giving up, and a glimpse into the process of making peace with our past and present selves. Report an issue with this product or seller. Print length. 272 pages. Language.

Indeed, his journalistic sensibilities shine in his writing of "Life on Delay" as he builds the story with fascinating, emotionally rich interviews, the sources ranging from experts on stuttering, to ex-girlfriends, to the sitting president of the United States, to the older brother that made his childhood an unrelenting hell.

In the fall of 2019, John Hendrickson wrote a groundbreaking story for The Atlantic about Joe Biden's decades-long journey with stuttering, as well as his own. The article went viral, reaching readers around the world and altering the course of Hendrickson's life. Overnight, he was forced to publicly confront an element of himself that still ...

About Life on Delay. A NEW YORKER BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR • USA TODAY BOOK CLUB PICK • ONE OF AUDIBLE'S BEST BIOS AND MEMOIRS OF 2023 • "A raw, intimate look at [Hendrickson's] life with a stutter.It's a profoundly moving book that will reshape the way you think about people living with this condition."—Esquire • A candid memoir about a lifelong struggle to speak.

The kind of memoir that educates, endears, impacts and devastates, often simultaneously ... Personal yet informative, Life on Delay delves into the internal poeticism of someone who feels perpetually on the fringe while offering tangible advice regarding what to say or not say to someone with a stutter. By combining his own personal narrative with others' life stories, Hendrickson provides a ...

January 18, 2023 Elaine Margolin. Senior Editor at The Atlantic John Hendrickson makes clear in his heartbreaking memoir, Life on Delay: Making Peace with a Stutter, how his life experiences have made him a much more introspective and empathic man. But it has also left him scarred from a lifetime of almost overwhelming challenges. Think about it.

In 'Life on Delay,' John Hendrickson examines what living with a stutter is like : NPR's Book of the Day In 2019, John Hendrickson wrote a piece for The Atlantic about then-presidential candidate ...

Format Hardcover. ISBN 9780593319130. An intimate, candid memoir about a lifelong struggle to speak. • "Soulful...Hendrickson provides a raw, intimate look at his life with a stutter. It's a profoundly moving book that will reshape the way you think about people living with this condition."—Esquire.

Life on Delay. : An intimate, candid memoir about learning to live with—rather than "overcome"—a stutter. In the fall of 2019, John Hendrickson wrote a groundbreaking story for The Atlantic about Joe Biden's decades-long journey with stuttering, as well as his own. The article went viral, reaching readers around the world and altering ...

Life on Delay recasts stuttering and, in doing so, challenges long-standing attitudes toward disability. By drawing deftly from personal experience, research, others' stories and his wellspring of empathy, Hendrickson transforms the disorder he avoided claiming for decades into an invitation to all of us to demonstrate genuine humanity. . . .

In Michael Bay's 2001 soapy blockbuster, Pearl Harbor, crucial seconds are wasted on the morning of December 7, 1941, because Red, a soldier who stutters, can't speak under pressure. Red ...

A NEW YORKER BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR USA TODAY BOOK CLUB PICK ONE OF AUDIBLE'S BEST BIOS AND MEMOIRS OF 2023 "A raw, intimate look at [Hendrickson's] life with a stutter. It's a profoundly moving book that will reshape the way you think about people living with this condition."— Esquire A candid memoir about a lifelong struggle to speak. " Life On Delay brims with empathy and honesty . . .

Poised at the intersection of life and art, reality and imagination, this novel blends the thrill of mystery with the curiosity and depth of philosophical inquiry. Fifteen years after Cecilia Berg ...

Jan 17, 2023. Life on Delay. USA Today Book Club. John Hendrickson. 978--593-62772-3. Audiobook Download. Jan 17, 2023. A NEW YORKER BEST BOOK OF THE YEAR • USA TODAY BOOK CLUB PICK • ONE OF AUDIBLE'S BEST MEMOIRS OF 2023 • A candid memoir about a lifelong struggle to speak. • "A raw, intimate look at [Hendrickson's] life with a stutter.

Life on Delay recasts stuttering and, in doing so, challenges long-standing attitudes toward disability. By drawing deftly from personal experience, research, others' stories and his wellspring of empathy, Hendrickson transforms the disorder he avoided claiming for decades into an invitation to all of us to demonstrate genuine humanity. . . .

In My Time of Dying is a short book. You can read about quantum entanglement almost in the same deep breath in which you read about Junger's father's visit to the OR. While Junger refuses to ...

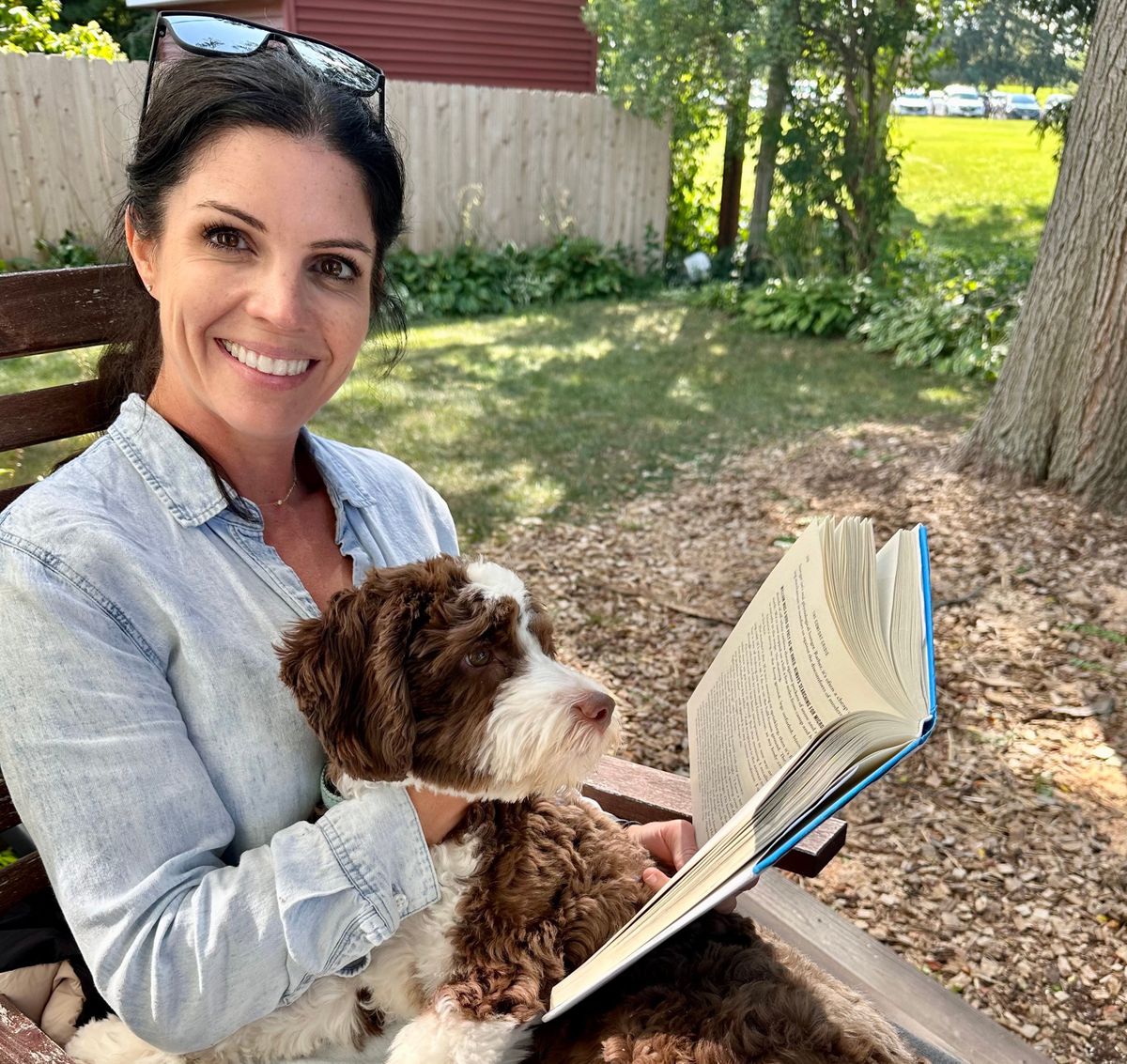

When Thomsen went to return the damaged book, she expected to pay for it. But the library told her she could send a photo of her dog instead. "It's showing grace and understanding," she said ...

By Margaret Renkl. Ms. Renkl is a contributing Opinion writer who covers flora, fauna, politics and culture in the American South. On the day of the eclipse back in April, walking through Boston ...

Life on Delay: USA Today Book Club - Kindle edition by Hendrickson, John. Download it once and read it on your Kindle device, PC, phones or tablets. Use features like bookmarks, note taking and highlighting while reading Life on Delay: USA Today Book Club. ... — The National Book Review "Hendrickson's writing style has a vibrant immediacy ...

Scholastic announced Thursday that "Sunrise on the Reaping," the fifth volume of Collins' blockbuster dystopian series, will be published March 18, 2025. The new book begins with the reaping of the Fiftieth Hunger Games, set 24 years before the original "Hunger Games" novel, which came out in 2008, and 40 years after Collins' most ...

June 8, 20247:00 AM ET. By. Heller McAlpin. Europa Editions. Valérie Perrin's novels have been enormously popular in her native France, and it's no wonder. Forgotten on Sunday, her third to be ...

FIRE EXIT, by Morgan Talty. There's a lovely clarity to Morgan Talty's debut novel, "Fire Exit.". He is especially bracing about the losses that can accrue with time. When we first meet ...