- Corpus ID: 28547839

Job Satisfaction in Public Sector and Private Sector: A Comparison

- G. Kumari , K. Pandey

- Published 2011

- Business, Economics, Political Science

70 Citations

Are public employees more satisfied than private ones the mediating role of job demands and job resources, turnover of public sector employees and the mediating role of job satisfaction: an empirical study in latvia, trust, job satisfaction, perceived organizational performance and turnover intention: a public-private sector comparison in the united arab emirates.

- Highly Influenced

Satisfaction with work-related achievements in Brunei public and private sector employees

International journal of science and business, to study the factors affecting the job satisfaction and level of job satisfaction at baswara garments ltd, comparing public and private employees' job satisfaction and turnover intention, the effect of telework on job satisfaction, professional satisfaction as a key factor in employee retention: a case of the service sector, the impact of job satisfaction on turnover intention: a comparative study between priva te and public banks and male and female bankers, 22 references, 'taking a sickie': job satisfaction and job involvement as interactive predictors of absenteeism in a public organization, the job satisfaction-job performance relationship: a qualitative and quantitative review., a meta-analytic review of attitudinal and dispositional predictors of organizational citizenship behavior, employee attitudes and job satisfaction, organizational behavior: affect in the workplace., motivation through the design of work: test of a theory., deconstructing job satisfaction: separating evaluations, beliefs and affective experiences, job attitude organization: an exploratory study1, the validity of the job characteristics model: a review and meta‐analysis, a current look at the job satisfaction/life satisfaction relationship: review and future considerations, related papers.

Showing 1 through 3 of 0 Related Papers

To read this content please select one of the options below:

Please note you do not have access to teaching notes, are public employees more satisfied than private ones the mediating role of job demands and job resources.

Management Research

ISSN : 1536-5433

Article publication date: 9 August 2021

Issue publication date: 20 October 2021

This paper aims to compare job satisfaction in public and private sectors and the mediating role of several job demands and resources on the relationship between the employment sector and job satisfaction.

Design/methodology/approach

Drawing on the job demands-resources model, this study argued that differences in job satisfaction were explained largely by the job characteristics provided in each sector. Data comes from the quality of working life survey, a representative sample of 6,024 Spanish public and private employees.

This study revealed that public employees were more satisfied than private ones. This relationship was partially mediated by job demands and job resources, meaning that the public and private employment sectors provided different working conditions. Public employees, in general, had fewer demands and more job resources than private ones, which resulted in different levels of job satisfaction. Additionally, partial mediation indicated that public employees are more satisfied than private ones, despite accounting for several job demands and job resources.

Research limitations/implications

While the findings of this study highlighted the relative importance of job demands and job resources in affecting job satisfaction of public and private employees, the generalizability of the results to other countries should be limited as the study only used data from a single country.

Practical implications

A significant portion of the positive effect on job satisfaction of public employees is channeled through the lower levels of routine work and lower number of required working hours and through better job resources such as higher salary, more telework, greater prospects at work and more training utility. To improve job satisfaction, it is apparent that managers should pay special attention to things such as routine work, working hours, training and telework.

Originality/value

This paper contributes to the comprehension of how several job demands and resources simultaneously play a mediating role in explaining the relationship between the employment sector and job satisfaction.

Este artículo compara la satisfacción laboral en los sectores público y privado y el papel mediador de varias demandas y recursos laborales en la relación entre el sector laboral y la satisfacción laboral.

Diseño/metodología/enfoque

Basándonos en el modelo Demandas del Trabajo-Recursos (JD-R), argumentamos que las diferencias en la satisfacción laboral se explican en gran medida por las características del trabajo que se ofrece en cada sector. Los datos proceden de la Encuesta de Calidad de Vida Laboral (ECVT), una muestra representativa de 6.024 empleados públicos y privados españoles.

Conclusiones

El estudio reveló que los empleados públicos estaban más satisfechos que los privados. Esta relación estaba parcialmente mediada por las exigencias del trabajo y los recursos laborales, lo que significa que los sectores de empleo público y privado ofrecían condiciones de trabajo diferentes. Los empleados públicos, en general, tenían menos exigencias y más recursos laborales que los privados, lo que dio lugar a diferentes niveles de satisfacción laboral. Además, la mediación parcial indicó que los empleados públicos están más satisfechos que los privados, a pesar de tener en cuenta varias demandas y recursos laborales.

Limitaciones e implicaciones de la investigación

Si bien los resultados de este estudio ponen de manifiesto la importancia relativa de las exigencias y los recursos del puesto de trabajo a la hora de afectar a la satisfacción laboral de los empleados públicos y privados, la generalización de los resultados a otros países debería ser limitada, ya que el estudio sólo utilizó datos de un único país.

Implicaciones prácticas

Una parte importante del efecto positivo sobre la satisfacción laboral de los empleados públicos se canaliza a través de los niveles más bajos de trabajo rutinario y el menor número de horas de trabajo exigidas y a través de mejores recursos laborales como un salario más alto, más teletrabajo, mayores perspectivas en el trabajo y más utilidad de la formación. Para mejorar la satisfacción laboral, es evidente que los directivos deben prestar especial atención a aspectos como el trabajo rutinario, el horario laboral, la formación y el teletrabajo.

Originalidad/valor

Este artículo contribuye a la comprensión de cómo varias exigencias y recursos del trabajo desempeñan simultáneamente un papel mediador en la explicación de la relación entre el sector del empleo y la satisfacción laboral.

Este artigo compara a satisfação profissional nos sectores público e privado e o papel mediador de várias exigências e recursos de emprego na relação entre o sector do emprego e a satisfação profissional.

Concepção/metodologia/abordagem

Com base no modelo Job Demands-Resources (JD-R), defendemos que as diferenças na satisfação no emprego eram em grande parte explicadas pelas características do emprego fornecidas em cada sector. Os dados provêm do Inquérito à Qualidade da Vida Profissional (QWLS), uma amostra representativa de 6.024 funcionários públicos e privados espanhóis.

O estudo revelou que os funcionários públicos estavam mais satisfeitos do que os privados. Esta relação foi parcialmente mediada por exigências e recursos de emprego, o que significa que os sectores público e privado de emprego proporcionavam condições de trabalho diferentes. Os funcionários públicos, em geral, tinham menos exigências e mais recursos de emprego do que os privados, o que resultou em diferentes níveis de satisfação no emprego. Além disso, a mediação parcial indicou que os funcionários públicos estão mais satisfeitos do que os privados, apesar de contabilizarem várias exigências de emprego e recursos laborais.

Limitações/implicações da investigação

Embora os resultados deste estudo tenham salientado a importância relativa das exigências e dos recursos do emprego para a satisfação dos trabalhadores públicos e privados, a generalização dos resultados para outros países deve ser limitada, uma vez que o estudo apenas utilizou dados de um único país.

Implicações práticas

Uma parte significativa do efeito positivo na satisfação profissional dos funcionários públicos é canalizada através dos níveis mais baixos de trabalho de rotina e do menor número de horas de trabalho necessárias e através de melhores recursos laborais, tais como salários mais elevados, mais teletrabalho, maiores perspectivas no trabalho, e mais utilidade na formação. Para melhorar a satisfação profissional, é evidente que os gestores devem prestar especial atenção a coisas como o trabalho de rotina, horas de trabalho, formação, e teletrabalho.

Originalidade/valor

Este artigo contribui para a compreensão de como várias exigências e recursos laborais desempenham simultaneamente um papel de mediação na explicação da relação entre o sector do emprego e a satisfação profissional.

- Job satisfaction

- Job demands

- Job resources

- Public employees

- Demandas laborales

- Recursos laborales

- Empleados públicos

- Satisfacción laboral

- Procura de emprego

- Recursos laborais

- Funcionários públicos

- Satisfação profissional

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge financial support by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness research project ECO2017-86305-C4-4-R (AEI/FEDER, UE). Lourdes Gastearena also appreciates the valuable comments from Professor Riccardo Peccei and other anonymous reviewers on an earlier version of this paper.

Gastearena-Balda, L. , Ollo-López, A. and Larraza-Kintana, M. (2021), "Are public employees more satisfied than private ones? The mediating role of job demands and job resources", Management Research , Vol. 19 No. 3/4, pp. 231-258. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRJIAM-09-2020-1094

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2021, Emerald Publishing Limited

Related articles

All feedback is valuable.

Please share your general feedback

Report an issue or find answers to frequently asked questions

Contact Customer Support

Advertisement

The Education-Job Satisfaction Paradox in the Public Sector

- Open access

- Published: 30 June 2023

- Volume 23 , pages 1717–1735, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Cristina Pita ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5977-3484 1 &

- Ramón J. Torregrosa ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8443-8330 2

1340 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

We compare the self-reported satisfaction of workers, employed in the private and the public sectors across European countries, with their working conditions and pay and have reached a controversial conclusion. Although we have found there are more educated workers in the public sector than in the private sector, higher-educated workers report lower levels of satisfaction with their working conditions and income when employed in the public sector, which was the opposite for less educated workers employed in this same sector. In contrast, we found a positive association between education and job satisfaction for workers employed in the private sector.

Similar content being viewed by others

Education-Job mismatch, earnings and worker’s satisfaction in African labor market: evidence from Cameroon

Job Satisfaction of Recent University Graduates in Economics Sciences: The Role of the Match Between Formal Education and Job Requirements

Over-qualification and the dimensions of job satisfaction.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Much has been written on employment in the public and private sectors and the relative attributes of each one. To begin with, there exists a vast array of literature on public–private sector wage differentials Footnote 1 (Bender, 1998 ; Mueller, 1998 ; Birch, 2006 ; Lucifora & Muers, 2006 ; Makridis, 2021 ; Sánchez-Sánchez & Fernández Puente, 2021 ), as well as job satisfaction (Ghinetti, 2007 ; Heywood et al., 2002 ). In addition, there is another area of research on employment in the public and private sectors that focuses on the returns to education that workers obtain when they are employed in both sectors. Most studies are empirical and have been done using surveys of mainly cross-sectional data for specific countries. However, within this line of research, there seems to exist a consensus that returns to education are higher in the private sector in most countries (Montenegro & Patrinos, 2022 ). That is to say, the return of workers in the private sector of the economy to further education is higher than for those working in the public sector (Psacharopoulos & Patrinos, 2018 ). According to Budria ( 2010 ), this is a worldwide phenomenon, although some authors have recently found exceptions to this stylized fact in a handful of countries such as India (Chen et al., 2022 ) and Turkey (Patrinos et al., 2019 ). Psacharopoulos ( 1979 ) explains that wages may exceed productivity in the public but not in the private sector. Furthermore, the overpayment of government workers with respect to their productivity can be mostly found at the lower end of the earnings distribution (Siminski, 2013 ). The public sector offers (relatively) high wages to unskilled workers and (relatively) low wages to the high-skilled (Budria, 2010 ). Psacharopoulos ( 1983 ) concludes that less qualified labor is better treated in the public than in the private sector.

Nonetheless, we could reasonably argue that it may not be the earnings that matter most to the workers, but the satisfaction they obtain from their working conditions and pay. Also, as far as we know, relatively less attention has been paid to returns to education in the public and the private sectors in terms of the workers’ well-being. Furthermore, there are several studies on job satisfaction in which both education and the sector (either public or private) are considered explanatory variables in job-satisfaction regressions, but the interaction between both variables and their effect on job satisfaction has not been analyzed yet.

In this paper, we analyze the self-reported levels of satisfaction with working conditions and pay of public and private sector workers who have attained different levels of education. In the context of Herzberg’s two-factor theory (Herzberg et al., 1959 ), our focus on satisfaction with working conditions and pay could be framed as an analysis of the hygiene or extrinsic factors of job satisfaction. In particular, we compare and rank the satisfaction with working conditions and pay of European workers who are employed in the private and public sectors. We intend to shed some new light on this topic by analyzing self-reported job satisfaction in a large sample of 43,850 workers from 35 countries, which is the last available wave of the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS).

Since data on job satisfaction provided by surveys is based on subjective replies to an interviewer’s questions in some sort of categorical fashion, in our analysis we use the Balanced Worth (BW) procedure. The BW was developed from the concept of Net Difference (Lieberson, 1976 ) and incorporates the economic concepts of value and equilibrium. This methodology has been specifically designed to compare distributions of categorical data (Herrero & Villar, 2013 , 2018 ) to analyze inequality among different population groups.

In recent years, the BW has been successfully used in different areas of the Social Sciences and has proven to be a suitable mechanism for researching happiness and well-being (Herrero & Villar, 2018 ). In particular, the BW procedure has been applied in studies on human capital and health (Herrero & Villar, 2013 ), education (Herrero et al., 2014 ), corporate responsibility (Gallén & Peraita, 2015 ), nationalist identity (Torregrosa, 2015 ), research (Albarrán et al., 2017 ), life satisfaction (Herrero & Villar, 2018 ), labor market (Herrero & Villar, 2019 ), happiness (Ravina-Ripoll et al., 2020 ), COVID-19 (Herrero & Villar, 2020 ), and income distributions (Herrero & Villar, 2021 ).

The paper proceeds as follows. We devote the next two sections to briefly summarizing the methodology and describing the data set. The following sections display our results regarding satisfaction with working conditions and payment in both sectors. The final section summarizes the conclusions of our empirical analysis.

The BW Procedure

Questions regarding job satisfaction are quite similar across surveys, as they ask workers to provide an overall assessment of their job satisfaction and working conditions, offering them several categorical responses. Score methods are commonly used when dealing with ordered categorical data, which consist of giving weights to each of the categories in an appropriate order and evaluating the groups according to their mean values. The problem with these methods is that the choice of weights introduces an exogenous cardinalization in the original information, leading to arbitrary results.

An alternative method is based on the concept of stochastic dominance. This procedure is robust, and only relies on categorical information, without using external weights. But this method provides neither a complete order nor cardinal information about the relative goodness of the distributions (Herrero & Villar, 2018 ). To amend these problems, Lieberson ( 1976 ) posed a procedure to compare any pair of distributions, based on the concept of probabilistic dominance. That is, how likely it is that an individual from one group chosen at random will belong to a higher category than an individual from any other group chosen at random.

Following Herrero and Villar ( 2013 , 2018 ), let us consider the problem of comparing the distributions of g different groups over a set of k categories. The following table shows the information that we can draw from our data set, where the first row represents different categories. These categories are ordered from best to worst and the first column corresponds to the different groups and \({x}_{ij}\) denotes the relative frequency in which category j appears in group i , where \({\sum }_{j=1}^{k}{x}_{ij}=1, \forall i=\mathrm{1,2},\dots ,g.\)

\({c}_{1}\) | \({c}_{2}\) | … | \({c}_{k}\) | |

\({f}_{1}\) | \({x}_{11}\) | \({x}_{12}\) | … | \({x}_{1k}\) |

\({f}_{2}\) | \({x}_{21}\) | \({x}_{22}\) | … | \({x}_{2k}\) |

\(\vdots\) | ||||

\({f}_{g}\) | \({x}_{g1}\) | \({x}_{g2}\) | … | \({x}_{gk}\) |

Our comparison problem consists of evaluating the relative dominance of these frequencies among them. This is an extension of the concept of Net Difference introduced by Lieberson ( 1976 ) for the case of two groups. Hence, let

be the probability that a randomly chosen individual from group i belongs to a better category than a randomly chosen individual from group j. On the other hand, the probability that the randomly chosen individuals from both groups belong to the same category is

where \({e}_{ij}={e}_{ji}\) and \({p}_{ij}+{p}_{ji}+{e}_{ij}=1\) . The procedure posed by Herrero and Villar ( 2018 ) consists of choosing one individual from each group at random and comparing its category with that of a randomly chosen individual from all the other groups. In the pairwise comparison, when a randomly chosen individual of group i belongs to a higher category than a randomly chosen individual of group j , we say that the distribution of group i dominates the distribution of group j . If both individuals belong to the same category (with probability \({e}_{ij}\) ), each group is declared dominant with a probability of 0.5. Hence, the probability of group i being declared not worse than group j is \({{q}_{ij}=p}_{ij}+\frac{1}{2}{e}_{ij}\) . At this point, Herrero and Villar ( 2013 , 2018 ) introduce the concept of the worth of group i , given by \({v}_{i}\) , which could be interpreted as the value of not-being dominated by any group. To avoid problems of cycles that may arise in the pairwise comparisons between groups, Herrero and Villar ( 2018 ) propose to determine the groups’ worth by equating the expected worth of group i not being dominated by the rest of the groups with the expected worth of the rest of the groups not being dominated by group i. That is,

Extending this criterion to all the groups, we can write the following homogeneous linear system \(Mv=0\) , where

and \({v}^{^{\prime}}=\left({v}_{1},{v}_{2},\dots ,{v}_{g}\right)\) . Since the sum of each column of M equals zero, the vectors that conform it are linearly dependent, thus M is singular, and the homogeneous system has one degree of freedom. To amend the indetermination of the solution, Herrero and Villar ( 2018 ) add an additional equation associated with the normalization of the worth vector, say \(\sum_{1}^{g}{v}_{i}=g.\) Footnote 2 Herrero and Villar ( 2018 ) prove that the solution to this system exists, is unique, and is given by \({v}^{*}=\left({v}_{1}^{*},{v}_{2}^{*},\dots ,{v}_{g}^{*}\right)\) such that \(\sum_{1}^{g}{v}_{h}^{*}=g\) , and

We call \({v}^{*}\) the BW vector. The main contribution of the BW is that, according to the probability of the domination criterion, it ranks the different groups using a cardinal measure. In contrast to the score methods previously used to compare categorical distributions, the BW procedure does not only rank the dominance of a group, but it also provides endogenous information about the intensity of such dominance using the cardinality of its components. The BW has other desirable properties, such as anonymity, symmetry, and monotonicity (see Herrero & Villar, 2013 , 2018 ).

The website of the Instituto Valenciano de Investigaciones Económicas (IVIE) provides the algorithm to calculate the BWV freely ( http://www.ivie.es/balanced-worth/ ).

The data set that we use is the sixth wave of the European Working Conditions Survey (EWCS), which was conducted in 2015 by the European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) and interviewed 43,850 workers whose answers provide an overview of working conditions in Europe. Using the cross-national weights given by the EWCS ensures that each country is represented in proportion to the size of its in-work population.

The EWCS is based on a questionnaire that was administered face-to-face to a random sample of 'persons in employment', both employees and self-employed, who work in the private sector, the public sector, or at other alternatives, such as joint private–public organizations or companies, the not-for-profit sector or non-governmental organizations. Among them, 68.47% of surveyed individuals declare to work in the private sector, while 23.06% declare to work in the public sector. For our purposes, we focus on the private and the public sectors, where 91.53% of workers are employed.

Regarding worker’s education, the EWCS classifies the attained educational levels of surveyed individuals according to the categories of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED). These categories and their percentages in the EWCS are the following: childhood education (0.58%), primary education (4.75%), lower secondary education (13.37%), upper secondary education (41.55%), post-secondary-non-tertiary education (7.02%), short-cycle tertiary education (9.42%), bachelor or equivalent (13.05%), master or equivalent (9.29%), and doctorate or equivalent (0.95%). For the sake of representativeness, we consider individuals that report levels of education from primary to master or equivalent. Footnote 3 Moreover, to keep a unimodal and symmetrical distribution, we gather the groups of post-secondary-non-tertiary education and short-cycle tertiary education in one group called post-secondary-tertiary education (16.43%).

Let us first consider the educational attainment of workers employed in the private and public sectors using the BW procedure. Table 1 shows the distributions of groups for the private and the public sector according to the level of education of their workers and their corresponding Balance Worth Value (BWV).

The BW components in Table 1 indicate that a randomly chosen individual from the public sector is more likely to have a higher education level than a randomly chosen individual from the private sector . In other words, the concentration of educated workers is considerably higher in the public than in the private sector across European countries, as the frequency distributions and the subsequent BW calculation show. Notice the difference between both components of the BW vector, which suggests a high level of inequality in terms of the educational attainment of workers in both sectors. This will be our first finding.

Moreover, we have analyzed whether this result holds in each of the 35 countries of the EWCS. We have also calculated the difference between the BW components and ordered countries according to that difference. These calculations are shown in the Appendix. Figure 1 illustrates the differences in the BW components for the public and the private sectors for each country. As we can observe, in all the countries workers’ educational attainment is higher in the public than in the private sector with no exception. Nonetheless, there are differences across countries. The country with greater inequality in both sectors regarding the educational attainment of its workers is Albania, followed by Turkey and Greece. At the other end of the spectrum, we find The Netherlands, where the educational achievement of workers in the public and the private sector is more similar, remaining higher in the public than in the private sector, as in any other country in this data set.

Difference between workers’ educational attainment in the public and private sector BWV components by countries ranked from the lowest to the highest

Working in the public sector has been related to higher levels of job satisfaction (Ghinetti, 2007 ; Heywood et al., 2002 ). Ghinetti ( 2007 ) indicates that public employees differ from private employees in the way they evaluate satisfaction with job security, consideration by colleagues, and safety and health job features. Sánchez-Sánchez and Fernández Puente ( 2021 ) conclude that public sector employees are more satisfied in terms of stability but not in terms of wages. According to Clark and Postel-Vinay ( 2009 ), permanent public jobs are perceived to be by and large insulated from labor market fluctuations and this may be the reason educated workers prefer to be employed in the public sector of the economy.

We now proceed to analyze and compare the levels of satisfaction with working conditions and payment reported by workers with different levels of educational attainment employed in both sectors.

Satisfaction with Working Conditions

Question Q88 of the EWCS enquires about the worker’s satisfaction with working conditions in the following terms: “On the whole, are you very satisfied, satisfied, not very satisfied, or not at all satisfied with working conditions in your main paid job?” Overall , 24.79% of workers report being very satisfied, 58.41% report being satisfied, 13.08% report being not very satisfied, 3.02% report being not at all satisfied, and 0.6% report no opinion or refuse to answer this question. Footnote 4

Tables 2 and 3 show the distributions and the satisfaction with working conditions for the different educational levels measured through the BW for the private and the public sectors, respectively.

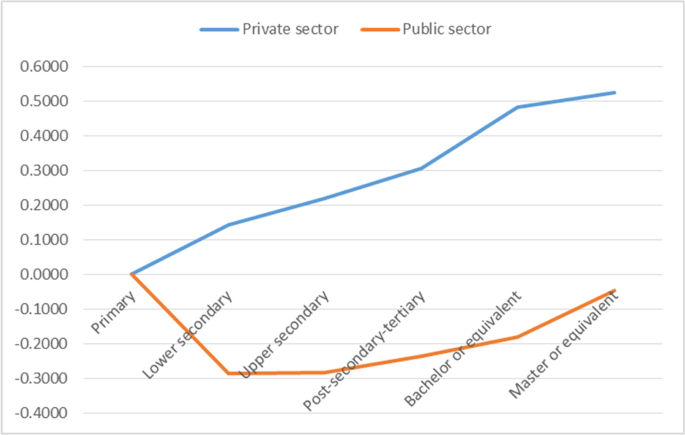

Results radically differ in both sectors. While in the private sector, we can observe a monotonically increasing relationship between workers’ educational attainment and job satisfaction, in the public sector this monotonicity is lost. We can also observe how the BW components in the public sector are much closer to their mean value, Footnote 5 which suggests that the different educational groups are more similar in terms of job satisfaction than within the private sector, where the range of the BW components is larger. Neither lower nor upper secondary education is associated with higher job satisfaction than primary education. In a similar line, having a bachelor’s degree does not improve job satisfaction in the public sector. In general, we can assert that there is little difference in terms of satisfaction with working conditions among workers belonging to alternative educational groups in the public sector whereas job satisfaction clearly increases with education in the private sector.

To visualize these results and compare them across sectors, we have calculated the differences between each component of the BW vector and the component of the group of workers with primary education, which we denote as the primary-education normalized BW (PENBW). We have done this for both sectors and our findings are illustrated in Fig. 2 . Clear differences can be observed between both sectors.

PENBW for satisfaction with working conditions by sectors

Adopting an alternative perspective in terms of BW calculations, we can compare workers’ job satisfaction in the private and public sectors within each educational group. Table 4 displays these results. As we can observe, workers who have attained the highest levels of education, i.e., bachelor’s and master’s degrees, report being more satisfied with their working conditions if they work in the private sector whereas workers with lower educational attainment report being happier at work when they are employed in the public sector. Notice the relatively larger difference in the BW components for workers with primary education, which suggests that workers with the lowest level of educational attainment report being much more satisfied with their working conditions if they are employed in the public than in the private sector.

Satisfaction with Pay

We proceed to analyze whether workers employed in the private and public sectors feel satisfied with the pay that they receive. The EWCS poses the following question Footnote 6 : Considering all my efforts and achievements in my job, I feel I get paid appropriately , for which it offers the following options: Strongly agree; Tend to agree; Neither agree nor disagree; Tend to disagree; Strongly disagree . Overall, 97.15% of workers answer this question, and the distributions of replies for each level of educational attainment are depicted in Table 5 along with the BW calculation.

The BW results indicate that the higher the level of education attained by workers, the higher the probability of them reporting they receive appropriate payment for their work. Indeed, there is a monotonic relationship between educational attainment and satisfaction with pay in the whole sample, but does this monotonicity hold in each sector?

To answer this question, in what follows, we undertake BW calculations segregating workers into two different subsamples, depending on whether they work for the private or the public sector. Results are shown in Tables 6 and 7 , respectively. Figure 2 illustrates the associated PENBW calculations (Fig. 3 ).

PENBW for satisfaction with payment by sectors for each level of education

Again, we find a completely different scenario in terms of the workers’ feelings toward their pay in the private and public sectors. Whereas workers in the private sector are more likely to report that the pay they receive is appropriate as their level of education increases, a nonmonotonic pattern can be observed for workers in the public sector. Moreover, in this sector, we find a paradoxical result, only the least educated (primary education) and the most educated (master or equivalent) are more likely to report being satisfied with the pay they receive. By contrast, workers with intermediate levels of educational attainment show lower degrees of satisfaction with their pay.

Finally, let us assess the BW calculation for workers' satisfaction with pay in the private and public sectors within each level of educational attainment. Table 8 depicts the results.

Only workers who have attained the lowest levels of education, i.e., primary or lower secondary, consider that they are more appropriately paid in the public sector than their private-sector counterparts. Workers with higher educational attainment feel more appropriately paid if they are employed in the private sector.

Although we are analyzing satisfaction with pay instead of monetary returns to education, we could say that our findings are in line with previous empirical evidence concerning the returns to education in terms of earnings in the public and private sectors. As we stated earlier, previous research has concluded that returns to education are higher for private-sector workers than for public-sector workers, at least in higher-income countries (Budria, 2010 ; Psacharopoulos, 1979 , 1983 ). In our large sample of mainly European workers, we find that workers with higher educational attainment report higher satisfaction with their pay when they are employed in the private sector and workers with lower educational levels report to be more satisfied with their earnings if they work in the public sector. In this sense, it is not surprising to find that the analysis of subjective measures of workers’ well-being with their pay is coherent with earlier empirical studies regarding the relative -and objectively measured- monetary returns to education in both sectors.

Concluding Remarks

Understanding how to assess returns to education in the public and the private sectors of the economy should be crucial to implement policy decisions in public sector administration. Just as policymakers can learn from estimates of the monetary benefits of education, we argue that workers’ perceptions of returns to education in both sectors should also be considered. However, while there is an established consensus that education is more profitable -in terms of earnings- in the private than in the public sector, relatively little is known about satisfaction with working conditions and pay in both sectors. In this paper, we have analyzed both issues for public and private sector employees with different educational attainment by applying the BW procedure to a large sample of European workers. We conclude that:

Educational attainment is higher among workers employed in the public sector in each one of the 35 countries of the EWCS data set.

Higher levels of satisfaction with working conditions and pay are related to higher levels of education in the private sector but not in the public sector.

Public-sector workers with lower education levels report higher levels of satisfaction with working conditions and pay compared with their private-sector counterparts.

Private-sector workers with higher levels of educational attainment declare higher levels of satisfaction with working conditions and pay than their public-sector counterparts.

Given the relatively higher levels of educational attainment of workers employed in the public sector, despite nonincreasing satisfaction with working conditions and pay, other underlying factors, which have not been considered in this paper, must determine the preference -and prevalence- of educated workers for the public sector. While this analysis falls beyond the scope of this paper and more research is needed to unravel this puzzle, one lesson to be learned is that despite the lower levels of satisfaction reported by highly educated people with working conditions and pay in the public sector, the likelihood of finding educated workers is still higher in this sector than in the private sector. Nevertheless, public administration managers should be, in our view, aware of this fact to implement policies that prevent highly educated workers employed in the public sector from quitting their jobs and searching for jobs in the apparently more rewarding private sector.

Data Availability

The data used in this paper was provided by Eurofound which has been cited in the references.

We only cite a few articles in each research area, as we do not intend to undertake an exhaustive literature review.

This constraint also allows us to equalize to one the average worth \(\left(\overline{v }\equiv \sum_{1}^{g}{v}_{i}/g=1\right)\) .

In our analysis, we have discarded the lowest and the highest educational levels because the number of workers that fall into those categories is relatively small.

In order to make these calculations, we have used the weights provided by the EWCS. Three types of weights needed to be applied to ensure that the results based on the data could be representative for workers in Europe.

The expected value of the BW components is 1 (Herrero & Villar, 2013 ).

This corresponds to Question 89A.

Albarrán, P., Herrero, C., Ruiz-Castillo, J., & Villar, A. (2017). The Herrero-Villar approach to citation impact. Journal of Infometrics, 11 (2), 625–640.

Article Google Scholar

Bender, K. A. (1998). The central government-private sector wage differential. Journal of Economic Surveys, 12 , 177–220.

Birch, E. (2006). The public-private sector earnings gap in Australia: A quantile regression approach. Australian Journal of Labour Economics, 9 , 99–123.

Google Scholar

Budria, S. (2010). Schooling and the distribution of wages in the European private and public sectors. Applied Economics, 42 (8), 1045–1054.

Chen, J., Kanjilal-Bhaduri, S., Pastore, F. (2022). Updates on Returns to Education in India: Analysis using PLFS 2018–19 Data. No. 1016. GLO Discussion Paper.

Clark, A., & Postel-Vinay, F. (2009). Job security and job protection. Oxford Economic Papers, 61 (2), 207–239.

European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. (2018). European Working Conditions Survey Integrated Data File, 1991-2015. [data collection]. 7th Edition. UK Data Service. SN: 7363, 10.5255/UKDA-SN-7363-7.

Gallén, M. L., & Peraita, C. (2015). A comparison of corporate social responsibility engagement in the OECD countries with categorical data. Applied Economics Letters, 22 (12), 1005–1009.

Ghinetti, P. (2007). The public-private job satisfaction differential in Italy. Labour, 21 (2), 361–388.

Herrero, C., & Villar, A. (2013). On the comparison of group performance with categorical data. PLoS ONE, 8 , e84784. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084784

Herrero, C., & Villar, A. (2018). The balanced worth: A procedure to evaluate performance in terms of ordered attributes. Social Indicators Research, 140 (3), 1279–1300.

Herrero, C., & Villar, A. (2020). A synthetic indicator on the impact of COVID-19 on the community’s health. PLoS One . https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238970

Herrero, C., & Villar, A. (2021). Opportunity advantage between income distributions. Journal of Economic Inequality, 19 , 785–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-021-09488-5

Herrero, C., Méndez, I., & Villar, A. (2014). Analysis of group performance with categorical data when agents are heterogeneous: The evaluation of scholastic performance in the OECD through PISA. Economics of Education Review, 40 , 140–151.

Herrero, C., Villar, A. (2019). The impact of the crisis on the labour market: A new appraisal. Universita’degli Studi di Firenze. Dipartamento di Science per l’Economia e l’Impresa, Working Paper 27/2019.

Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snydermann, B. (1959). The motivation to work . Wiley.

Heywood, J. S., Siebert, W. S., & Wei, X. (2002). Worker sorting and job satisfaction: The case of union and government jobs. ILR Review, 55 (4), 595–609.

Hospido, L., & Moral-Benito, E. (2016). The public sector wage premium in Spain: Evidence from longitudinal administrative data. Labour Economics, 42 , 101–122.

Lieberson, S. (1976). Rank-sum comparisons between groups. Sociological Methodology, 7 , 276–291.

Lucifora, C., & Muers, D. (2006). The public sector pay gap in France, Great Britain and Italy. Review of Income and Wealth, 52 , 43–59.

Makridis, C. A. (2021). (Why) Is there a public/private pay gap? Journal of Government and Economics, 1 , 100002. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jge.2021.100002

Montenegro, C. M., Patrinos, H. A. (2022). Returns to education in the public and private sectors: Europe and Central Asia. Discussion Paper Series. IZA DP No. 15516.

Mueller, R. E. (1998). Public-private sector wage differentials in Canada: Evidence from quantile regressions. Economics Letters, 60 , 229–235.

Patrinos, H. A., Psacharopoulos, G., Tansel, A. (2019). Returns to investment in education: The case of Turkey. Available at SSRN 3358397 (2019).

Psacharopoulos, G. (1979). On the weak versus the strong version of the screening hypothesis. Economics Letters, 4 , 181–185.

Psacharopoulos, G. (1983). Education and private versus public sector pay. Labour and Society, 8 (2), 123–134.

Psacharopoulos, G., Patrinos, H. A. (2018). Returns to investment in education: A decennial review of the global literature. Policy Research Working Paper 8402. World Bank Document.

Ravina-Ripoll, R., Almorza-Gomar, D., Tobar-Pesántez, L. (2020). Teaching and learning to be happy: econometric evidence in the entrepreneurs of Spain before COVID-19. Journal of Entrepreneurship Education 23 (5).

Sánchez-Sánchez, N., & Fernández Puente, A. C. (2021). Public versus private job satisfaction. Is there a trade-off between wages and stability? Public Organization Review, 21 , 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-020-00472-7

Siminski, P. (2013). Are low-skill public sector workers really overpaid? A quasi-differenced panel data analysis. Applied Economics, 45 (14), 1915–1929.

Torregrosa, R. J. (2015). Measurement and evolution of nationalist identity in Spain. Journal of Regional Research, 33 (1), 53–79.

Download references

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. The authors acknowledge the financial support provided by the Regional Government of Castile and Leon through grant SA049G19.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Economics and Economic History, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

Cristina Pita

Department of Economics and Economic History and IME, Universidad de Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain

Ramón J. Torregrosa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Cristina Pita .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest associated with this manuscript.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Netherlands | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1799 | 0.1725 | 0.0415 | 0.3373 | 0.2107 | 0.0581 | 0.9198 | |

Public sector | 0.2081 | 0.2258 | 0.0415 | 0.2808 | 0.2165 | 0.0273 | 1.0802 | 0.1605 |

Malta | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0407 | 0.1109 | 0.1439 | 0.2054 | 0.4552 | 0.0439 | 0.8710 | |

Public sector | 0.0761 | 0.1752 | 0.1551 | 0.1811 | 0.3732 | 0.0393 | 1.1290 | 0.2580 |

Luxembourg | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1994 | 0.0882 | 0.1013 | 0.3521 | 0.2008 | 0.0582 | 0.8656 | |

Public sector | 0.2621 | 0.0985 | 0.1234 | 0.3570 | 0.1167 | 0.0423 | 1.1344 | 0.2688 |

Belgium | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1153 | 0.0707 | 0.1964 | 0.4463 | 0.1428 | 0.0285 | 0.8336 | |

Public sector | 0.1588 | 0.0877 | 0.3205 | 0.2993 | 0.1130 | 0.0207 | 1.1664 | 0.3328 |

United Kingdom | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0897 | 0.1999 | 0.1176 | 0.2169 | 0.3711 | 0.0049 | 0.8207 | |

Public sector | 0.1568 | 0.2452 | 0.1616 | 0.1873 | 0.2369 | 0.0122 | 1.1793 | 0.3586 |

Switzerland | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0751 | 0.1419 | 0.0983 | 0.5646 | 0.1035 | 0.0165 | 0.7933 | |

Public sector | 0.2123 | 0.1987 | 0.0522 | 0.4633 | 0.0673 | 0.0062 | 1.2067 | 0.4134 |

Ireland | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1127 | 0.1911 | 0.3211 | 0.2565 | 0.0735 | 0.0452 | 0.7859 | |

Public sector | 0.2532 | 0.2505 | 0.2336 | 0.1508 | 0.0830 | 0.0290 | 1.2141 | 0.4283 |

France | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1487 | 0.0790 | 0.1666 | 0.5051 | 0.0771 | 0.0235 | 0.7694 | |

Public sector | 0.2748 | 0.1489 | 0.1507 | 0.3793 | 0.0321 | 0.0140 | 1.2306 | 0.4611 |

Estonia | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0843 | 0.0681 | 0.4200 | 0.2000 | 0.2253 | 0.0023 | 0.7680 | |

Public sector | 0.2341 | 0.0635 | 0.4312 | 0.1394 | 0.1317 | 0.0000 | 1.2320 | 0.4640 |

Latvia | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0885 | 0.1477 | 0.4297 | 0.2440 | 0.0830 | 0.0071 | 0.7613 | |

Public sector | 0.2489 | 0.2068 | 0.3164 | 0.1454 | 0.0773 | 0.0053 | 1.2387 | 0.4775 |

Czech Republic | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0757 | 0.0357 | 0.0902 | 0.7072 | 0.0896 | 0.0016 | 0.7596 | |

Public sector | 0.1951 | 0.0759 | 0.1776 | 0.4737 | 0.0683 | 0.0094 | 1.2404 | 0.4808 |

Slovenia | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0228 | 0.1816 | 0.0637 | 0.6504 | 0.0782 | 0.0033 | 0.7560 | |

Public sector | 0.0480 | 0.3710 | 0.0841 | 0.4406 | 0.0546 | 0.0018 | 1.2440 | 0.4880 |

Serbia | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0472 | 0.1086 | 0.1072 | 0.6534 | 0.0659 | 0.0177 | 0.7524 | |

Public sector | 0.1132 | 0.2110 | 0.1510 | 0.4949 | 0.0242 | 0.0057 | 1.2477 | 0.4953 |

Cyprus | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0956 | 0.1852 | 0.1997 | 0.4174 | 0.0777 | 0.0244 | 0.7486 | |

Public sector | 0.1540 | 0.3894 | 0.1193 | 0.2797 | 0.0274 | 0.0301 | 1.2515 | 0.5029 |

Sweden | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1205 | 0.1079 | 0.1024 | 0.5840 | 0.0832 | 0.0021 | 0.7357 | |

Public sector | 0.1947 | 0.1899 | 0.2094 | 0.3713 | 0.0348 | 0.0000 | 1.2643 | 0.5287 |

Montenegro | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0129 | 0.1590 | 0.0491 | 0.7071 | 0.0619 | 0.0100 | 0.7302 | |

Public sector | 0.0477 | 0.2941 | 0.1245 | 0.5168 | 0.0170 | 0.0000 | 1.2698 | 0.5395 |

Slovakia | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0792 | 0.0250 | 0.0561 | 0.8140 | 0.0247 | 0.0011 | 0.7302 | |

Public sector | 0.2942 | 0.0524 | 0.0952 | 0.5120 | 0.0405 | 0.0057 | 1.2698 | 0.5396 |

Finland | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1076 | 0.0488 | 0.4154 | 0.3233 | 0.0721 | 0.0328 | 0.7239 | |

Public sector | 0.2349 | 0.0777 | 0.4745 | 0.1633 | 0.0439 | 0.0058 | 1.2761 | 0.5521 |

Croatia | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0467 | 0.0974 | 0.0625 | 0.7204 | 0.0670 | 0.0060 | 0.7218 | |

Public sector | 0.1638 | 0.1712 | 0.1239 | 0.5098 | 0.0313 | 0.0000 | 1.2782 | 0.5564 |

Bulgaria | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.2003 | 0.0610 | 0.0193 | 0.5884 | 0.1236 | 0.0074 | 0.7208 | |

Public sector | 0.3552 | 0.1474 | 0.0760 | 0.3440 | 0.0714 | 0.0061 | 1.2792 | 0.5584 |

Germany | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0612 | 0.0624 | 0.1116 | 0.6875 | 0.0697 | 0.0077 | 0.7167 | |

Public sector | 0.1836 | 0.1514 | 0.1523 | 0.4742 | 0.0366 | 0.0019 | 1.2833 | 0.5666 |

Spain | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0370 | 0.1214 | 0.3626 | 0.1853 | 0.2074 | 0.0863 | 0.7093 | |

Public sector | 0.0352 | 0.2794 | 0.4563 | 0.0972 | 0.0969 | 0.0351 | 1.2908 | 0.5815 |

Hungary | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0580 | 0.0612 | 0.1857 | 0.5966 | 0.0975 | 0.0011 | 0.7082 | |

Public sector | 0.1275 | 0.2324 | 0.1820 | 0.4150 | 0.0431 | 0.0000 | 1.2918 | 0.5835 |

Italy | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0125 | 0.0901 | 0.0834 | 0.5168 | 0.2631 | 0.0342 | 0.7081 | |

Public sector | 0.0251 | 0.2436 | 0.1335 | 0.4600 | 0.1295 | 0.0084 | 1.2919 | 0.5837 |

Lithuania | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0780 | 0.1734 | 0.2464 | 0.4448 | 0.0575 | 0.0000 | 0.6719 | |

Public sector | 0.1550 | 0.3766 | 0.2180 | 0.2269 | 0.0235 | 0.0000 | 1.3282 | 0.6563 |

Poland | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1678 | 0.0583 | 0.0331 | 0.6711 | 0.0592 | 0.0104 | 0.6685 | |

Public sector | 0.4241 | 0.0771 | 0.0729 | 0.3918 | 0.0341 | 0.0000 | 1.3315 | 0.6630 |

Norway | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1197 | 0.1453 | 0.1854 | 0.4114 | 0.1207 | 0.0175 | 0.6526 | |

Public sector | 0.2671 | 0.2999 | 0.1549 | 0.2253 | 0.0415 | 0.0112 | 1.3474 | 0.6947 |

Denmark | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.1062 | 0.0724 | 0.2893 | 0.3391 | 0.1821 | 0.0109 | 0.6449 | |

Public sector | 0.2524 | 0.0949 | 0.4073 | 0.2168 | 0.0286 | 0.0000 | 1.3551 | 0.7102 |

Romania | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0265 | 0.1608 | 0.0581 | 0.6561 | 0.0810 | 0.0174 | 0.6387 | |

Public sector | 0.0882 | 0.3501 | 0.1509 | 0.3780 | 0.0259 | 0.0070 | 1.3613 | 0.7226 |

Portugal | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0321 | 0.1328 | 0.0184 | 0.2658 | 0.2353 | 0.3157 | 0.5878 | |

Public sector | 0.1108 | 0.3408 | 0.0117 | 0.3002 | 0.1361 | 0.1003 | 1.4122 | 0.8243 |

FYROM | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0238 | 0.1298 | 0.0511 | 0.4766 | 0.0856 | 0.2332 | 0.5852 | |

Public sector | 0.0922 | 0.3708 | 0.0928 | 0.3227 | 0.0516 | 0.0698 | 1.4148 | 0.8296 |

Austria | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0619 | 0.0144 | 0.1507 | 0.6854 | 0.0779 | 0.0097 | 0.5815 | |

Public sector | 0.1753 | 0.0737 | 0.3738 | 0.3545 | 0.0227 | 0.0000 | 1.4185 | 0.8370 |

Greece | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0338 | 0.1467 | 0.1881 | 0.4516 | 0.1188 | 0.0610 | 0.5059 | |

Public sector | 0.0424 | 0.5118 | 0.2484 | 0.1621 | 0.0150 | 0.0202 | 1.4941 | 0.9883 |

Turkey | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0086 | 0.1252 | 0.0652 | 0.2994 | 0.2169 | 0.2847 | 0.4368 | |

Public sector | 0.0645 | 0.5353 | 0.1027 | 0.1574 | 0.0484 | 0.0918 | 1.5632 | 1.1263 |

Albania | Master | Bachelor | Post-secondary-tertiary | Upper secondary | Lower secondary | Primary | BWV | Diff |

Private sector | 0.0333 | 0.2063 | 0.0850 | 0.3242 | 0.3427 | 0.0085 | 0.4350 | |

Public sector | 0.1944 | 0.5106 | 0.1104 | 0.1137 | 0.0708 | 0.0000 | 1.5650 | 1.1300 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Pita, C., Torregrosa, R.J. The Education-Job Satisfaction Paradox in the Public Sector. Public Organiz Rev 23 , 1717–1735 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-023-00726-0

Download citation

Accepted : 17 June 2023

Published : 30 June 2023

Issue Date : December 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-023-00726-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

JEL Classification

- Job satisfaction

- Public sector

- Private sector

- Balanced worth

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Job Satisfaction in Public Sector and Private Sector: A Comparison

Related Papers

Job may be defined as a specific task done as part of the routine of one's occupation or for an agreed price. Job is a social expectation and social reality to which people seem to confirm for maintaining their livelihood. It not only provides status and psychological satisfaction to the individuals but also binds them to the society. Job satisfaction is a person's attitude towards the job. Job satisfaction means measurement of excellence to which an employee feels contended and happy about his work and the conditions in which it has to be done. The main purpose of the study is to investigate the determinants like encouragement, management, working condition and training as the various facets of employee job satisfaction which plays a major role for employee performance. A quantitative approach is used in this study. A Pearson correlation research design and survey method is used to collect data. A research model and four hypotheses were developed. Regression analysis was us...

zekria Arif

Public Management Review

Meghna Sabharwal

ABSTRACT Job satisfaction has proven to be a resilient contributor to employee motivation, productivity, organizational commitment, absenteeism, and turnover. Utilizing cross-national data from five Asian countries/settings and the United States we examine the impact of organizational and psychological factors on job satisfaction. This study contributes to the literature by showing that while organizational factors, such as performance appraisals and leadership behaviours are important sources of job satisfaction, what matters most is whether individuals perceive themselves to be efficacious in their jobs. Self-efficacy was found to be the strongest determinant of job satisfaction in both, the U.S., and the Asian contexts. Based on cultural characteristics of power-distance and collectivism, this study also examines cross-national differences in the level of public employee job satisfaction.

Jeannette Taylor , Jonathan H Westover

What satisfies a public servant? Is it the money? Or is it something else, like an interesting and autonomous job, or serving the public interest? Utilizing non-panel longitudinal data from the International Social Survey Program on Work Orientations across different countries for 1997 and 2005, this article examines the effects of a selection of antecedents that are commonly related to job satisfaction. The respondents from different countries were found to share similarities in terms of what satisfies them in their jobs. The emphasis placed on these factors was however found to vary for some countries

International Journal of Managerial Studies and Research

fahad alrefaei

Journal ijmr.net.in(UGC Approved)

Job satisfaction is the level of contentment of a person feels regarding his or her job and this feeling is based on the level of satisfaction with their job. Today it is very Important to improve productivity of the organization for this it is require to improve the Performance of the employee by providing the maximum satisfaction at their work Place. There is difference in the work condition of public and private sector organization Therefore the level of employee job satisfaction is also differ from public sector organization to Private sector organization .From my study I found that people who working in public Sectors are more satisfied as compare to private sector.

International Journal of Indian Psychology

Pravin Solanki

The main objective of the present study is to examine the job satisfaction among government and private employees. A sample of 60 male and female employees was drawn randomly drawn from the population. The Generic Job Satisfaction Scale: Scale Development and Its Correlates, developed by Scott Macdonald and Peter Maclntyre (1997) was used for data collection. Data was collected by face to face interview method from the target population from different originations of Anand district. Mean, standard deviation and t-test were calculated for the analysis of data. Results indicate that there is no significant difference among government and private employees in job satisfaction.

Dr Nawaz Ahmad

Res Militaris

Saif Ahmed , Md. Ibrahim Khalil

Background: Satisfaction at work is especially vital in a developing nation like Bangladesh, where the Bangladesh Civil Service (BCS) officers are the country's most valuable and significant human resource. Despite obstacles, the government of Bangladesh has made significant efforts in recent years to encourage and influence public employees, notably BCS (administration) cadre officers, to increase their efficiency and activity in service delivery to the public. This research examines the relationship between Bangladesh Cadre Service officer job satisfaction and exogenous (such as working conditions) and endogenous (such as internal rewards and recognition for outstanding performance and creative problem solving) organizational factors. As an administrator in the Bangladesh Civil Service, this study is not only fascinating but also pertinent to my own. Not only did this study draw on my personal experiences and insights, but also a variety of current theoretical frameworks and models to give you the most in-depth look at the topic possible. Methods: Both quantitative and qualitative strategies were used in this study's investigation. From these areas, 106 Bangladesh Cadre Service officers have randomly been selected. We examined the survey responses using SPSS-25 and SmartPLS-4. Results: The result of this study indicates that the Bangladesh Cadre Service officer, who is now working at the field level, is moderately satisfied. Analysis indicates that transfer and posting, work and working environment and promotion and recognition are significant predictors of Job Satisfaction except for the other two variables-salary and training and career planning. This study also showed some other factors that have a strong significant relationship with the overall job satisfaction of Bangladeshi field-level civil servants. Conclusions: Policymakers may use this study's findings to enhance compensation strategies and strike a better balance between extrinsic and intrinsic incentives by better comprehending the effect of pay, promotion and recognition on work satisfaction.

RELATED PAPERS

Texas State PA Applied Research Projects

Shuaib Soomro

Jatin Yadav

Rashmi V Chordiya

melkamu fentahun

journal ijetrm

Ijetrm Journal

International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management

Anamarija Leben

Journal of Human Resource Management

Hakan Candan

Pattimura Proceeding: Conference of Science and Technology

mukhlis yunus

Boglarka Borbely

John Salvador

Editor IJTEMT

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health

Michele Sorrentino

New Challenges of Economic and Business Development 2018: Productivity and Economic Growth - University of Latvia

Kostas Karamanis , Arnis Nikolaos

Journal of Vocational Behavior

Barbara Gutek

Mariatul Shima

Journal of human resource management

Social and Management Research Journal

MUHAMMAD AMMAR HAIDAR ISHAK

Losanta Sidro-Sanico

Gerd Groezinger , Wenzel Matiaske

internationalconference.com.my

Sentosa Ilham , Shishi Piaralal

Florissa Brylle

Applied Economics

Aysit Tansel

Bassem Maamari

Ćatović Azra

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Public sector job satisfaction hits four-year high

CIPD/Halogen survey finds post-referendum optimism among UK employees, but more work needed on development and career progression

Job satisfaction in the public sector is at its highest level in four years and wider post-referendum optimism is evident among UK employees. However, there is still ample room for improvement in employee development and career progression, which employers must address quickly so as not to lose valuable talent.

This is according to the latest CIPD/Halogen Employee Outlook report. The survey of more than 2,000 employees found that 63% of employees are satisfied with their jobs, rising to two-thirds (66%) in the public sector, the highest level for that sector since autumn 2012.* However, public sector employees still report higher levels of pressure and exhaustion at work than any other sector. Two in five public sector workers (43%) say they are under excessive pressure at work at least once a week (all employees: 38%), and nearly half (46%) say they come home from work exhausted either always or often (all employees: 33%).

The report found evidence of post-referendum optimism among employees in all sectors:

- More than half of employees (57%) believe it is unlikely they will lose their current main job, with one in ten (12%) saying they think it is likely.

- Almost half (48%) feel there has been no change to their financial security since the start of 2016, and a similar number (47%) feel there will be no change in the next 12 months.

- Organisational costs (53%)

- Workforce training and skill development (60%)

- Investment in equipment and technology (61%)

Claire McCartney, Associate Research Adviser at the CIPD, the professional body for HR and people development, commented: “It’s fantastic to see such a leap in job satisfaction in the public sector since our last survey in the spring, especially in such uncertain times for the UK. There was a great deal of uncertainty before the referendum, so people might be feeling more settled, and many will be happy with the outcome based on their voting decision. Other reasons could include the optimism that usually comes with a new government, and it could be that some of the new messages we’re hearing on fairness and equality might be resonating with public sector workers.

“Despite this positive outlook from public sector employees, the fact remains that employees in this sector are most likely to suffer with excessive pressure at work and exhaustion. This shouldn’t be overlooked, as it can create real problems for employers and individuals. Previous research has shown that the public sector also has the highest levels of absence and number of employees coming into work ill by some margin, so it’s crucial that employers address these issues before workers burn out and satisfaction levels take a nose dive.”

The survey also found significant room for improvement in employee development and career progression across all sectors. A third of employees (33%) say they are unlikely to fulfil their career aspirations in their current organisation, over a quarter (27%) disagree that their organisation provides them with opportunities to learn and grow, and a similar number (24%) are dissatisfied with the opportunity to develop their skills in their job.

There is also a noticeable implementation gap between the training that employees find useful and the training they actually receive. For example, 92% of employees said they find job rotation, secondment and shadowing useful, but only 6% have received it in the last 12 months. Similarly, 81% said blended learning was beneficial, but just 4% have received it over the last year. On the other hand, only 59% of employees flagged online learning as useful for their development, but 25% have still received it, suggesting that learning and development investment may not be targeting the areas of most use to the workforce.

McCartney continues: “In today’s world of work, organisations are increasingly expected to think about the two-way employment contract, giving employees opportunity to develop transferable skills that will support them throughout their careers, not just in their current roles. This can be a mutually beneficial arrangement - employees can have more autonomy over their career paths, and employers can be more agile to shape their workforce to fit their business needs.

“But in order to hold up their end of the deal, employers need to position line managers to support employees’ career progression. This should include having regular development conversations with employees to help them take the steps needed to develop and fulfil their potential. They also need to choose training and development that is right for their staff, not just the most economical. To do this, they must ensure that they are listening to what their employees need in order to make sure training and development is relevant and effective enough to plug skills gaps, as well as improve employees’ ability to do their jobs well.”

Dominique Jones, Chief People Officer at Halogen Software, said: “ To compete against rapidly changing market forces, organisations need to hire smarter, develop faster, and build a compelling and meaningful work experience for employees. They must start with a talent strategy aligned to the needs of both the organisation and its people. The most effective way to support that strategy is to make performance management an essential part of the day-to-work experience, and direct managers have the largest role to play here. They need to be provided with the tools, training and support to become skilled coaches who encourage forward-focused growth and development. This approach will ensure that whatever context the labour market finds itself in, organisations are ready to attract, engage, and retain skilled people, motivated to deliver results.”

Further highlights from the survey include:

- Health and well-being: More than a third of employees (36%) believe their organisation supports employees with mental health problems either very or fairly well, and a quarter (25%) believe they do so either not very or not at all well. More employees were either not very or not at all confident (47%) rather than confident (43%) to disclose unmanageable stress or mental health problems to their employer or manager.

- Over-qualification: A third (33%) of employees believe they are overqualified for their current role. Just 26% of those that believe they are overqualified for their roles are satisfied with their jobs compared to 68% who believe they have the right level of qualification.

- Happiness at work: More employees say work makes them feel positive rather than negative. Employees are most likely to say that work makes them feel cheerful (29%) most or all of the time as opposed to any other feeling. This is followed by optimistic (20%), then stressed (17%) and relaxed (17%).

- Financial well-being: The aspects of financial well-being most important to employees are: Earning a sufficient wage to enjoy a reasonable lifestyle (75%), being able to save for the future (55%), and feeling that they are being rewarded for their efforts in a fair and consistent manner (54%).

* Net score = +45 compared to +32 in Spring 2016

Download the full report

If you wish to reproduce this press release in full on your website, please link back to the original source.

Media centre

Are you a journalist looking for expert commentary and insights on the world of work?

CIPD Media Centre

Request an interview

To get a fresh, evidence-based perspective from one of our expert commentators – on this or any other workplace issue – please contact our press team on +44(0)20 8612 6400 or [email protected]

Latest press releases

10 Sept, 2024

30 Aug, 2024

20 Aug, 2024

13 Aug, 2024

Get all our latest press releases direct to your inbox

Sign-up here to get all CIPD press releases.

You can unsubscribe or change your marketing preferences at any time by visiting our Marketing Preference Centre . By submitting this form you confirm that you have read our privacy policy and terms and conditions .

Championing better work and working lives

About the CIPD

At the CIPD, we champion better work and working lives. We help organisations to thrive by focusing on their people , supporting economies and society for the future . We lead debate as the voice for everyone wanting a better world of work.

- Public Economics

- Private Sector

An Analysis of Factors Affecting Job Satisfaction of the Employees in Public and Private Sector

- Lal Bahadur Shastri Institute of Management

Discover the world's research

- 25+ million members

- 160+ million publication pages

- 2.3+ billion citations

- Anees Ahmad

- Bassam Khalil Hamdan Tabash

- Layla Yousef

- Ajayi Olayemi

- Shameer Khokhar

- Manzoor Ahmed

- Dhara Singh

- Sanjeev Kumar

- Dr. Anishka Hettiarachchi

- P. Ganapathi

- D. Kanchana

- Gladness R. Msuya

- Hawa I. Munisi

- Emmanuel Nonso Api

- Francisca Nkiruka Ezeanokwasa

- Timothy A. Judge

- J OCCUP ORGAN PSYCH

- Jürgen Wegge

- Klaus-Helmut Schmidt

- Carl J. Thoresen

- Joyce E. Bono

- Gregory K. Patton

- Vittesh Bahuguna

- Frederick Herzberg

- Dora F. Capwell

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Job satisfaction has been defined as a pleasurable. emotional state resulting from the appraisal of one's job; an. affective reaction to one's job; and an attitude towards one's. job. We can ...

The current study examines a global sample from 37 countries to examine the effects of work-life balance, intrinsic and extrinsic rewards, and work relations on job satisfaction for public and private sector employees, using data from the International Social Survey Program.

ive beliefs and affective experiences are salient and predominate. In this respect, research could, fo instance, collect manager perceptions of performance consistency. Future research should aim to replicate the present findings with larger and more diverse samples as well as prof Index Terms—job satisfaction, public sector, private sector ...

Trust, job satisfaction, perceived organizational performance and turnover intention: A public-private sector comparison in the United Arab Emirates. Purpose The purpose of this paper is to examine and compare the differential impacts of job satisfaction (JS), trust (T), and perceived organizational performance (POP) on turnover intention….

Abstract and Figures This article aims to systematically review the empirical literature on the determinants of employees' job satisfaction in public sector organizations worldwide.

Renewed interest in increasing performance levels in government should interest public administrators in identifying factors that foster worker satisfaction. However little empirical attention has been given to evaluating job-satisfaction levels among public-sector employees. And given that the reward system in the public sector systematically differs from that of the private sector (in terms ...

Background: Organizational leaders in public sector organizations must pay serious attention to employee job satisfaction because they provide community services.

Design/methodology/approach Drawing on the job demands-resources model, this study argued that differences in job satisfaction were explained largely by the job characteristics provided in each sector. Data comes from the quality of working life survey, a representative sample of 6,024 Spanish public and private employees.

The comparative job satisfaction literature has found consistent though small differences in the work-related attitudes reported by employees of public and private organizations. Public employees have shown lower levels of work satisfaction, organizational commitment, and reward expectancies.

This research develops a model to study the effects of public service motivation on job satisfaction and further assesses the mediation effects of work engagement and organizational commitment. Five-hundred and fifty employees from Chinese public service sectors were engaged in the questionnaire-based study.

The intrinsic and extrinsic aspects of a person's job appear to moderate a worker's. satisfaction. That is, lower skilled, public sector employees are more satisfied with the environmental or intrinsic factors of their job while public sector professionals feel that maintenance or extrinsic factors. are more satisfying.

The existing literature has identified the relationship between organizational commitment and job satisfaction as interesting in this context. The present field study examines the satisfaction-commitment link with respect to differences between private and public sector employees.

This paper examines the differences in job satisfaction in the public and private sector using the Spanish Survey of Life Quality at Work throughout the period 2006-2010. We use several dimensions of job satisfaction perception (remuneration, promotion policy, time schedule, working hours, flexibility, breaks and holidays). Our results show that, at an aggregate level, public sector workers ...

Abstract This study examines the influence of the work environment on public employee feelings of job satisfaction, linking characteristics of the work context perceived to be more prevalent in public organizations with specific job characteristics that serve as important antecedents of job satisfaction. In particular, this study analyzes the effects of three components of the work context ...

Future research should examine more detailed country-specific variations and the corresponding causes and explore private/public sector determinants on a global basis.

This paper aims to identify the main factors that determine the level of job satisfaction of public sector employees in a developing country and to find out which factors should be addressed first in order to decrease employee turnover. The survey conducted in 2015 included 365 respondents.

We compare the self-reported satisfaction of workers, employed in the private and the public sectors across European countries, with their working conditions and pay and have reached a controversial conclusion. Although we have found there are more educated workers in the public sector than in the private sector, higher-educated workers report lower levels of satisfaction with their working ...